Introduction: When Technology Meets Tradition at the Winter Games

There's something uniquely captivating about watching a professional skier launch into a double backflip, with a camera capturing every millisecond from an angle that would've been impossible just five years ago. That's the magic of FPV drones at the Winter Olympics. But here's the thing: that same technology making viewers gasp also makes athletes wince.

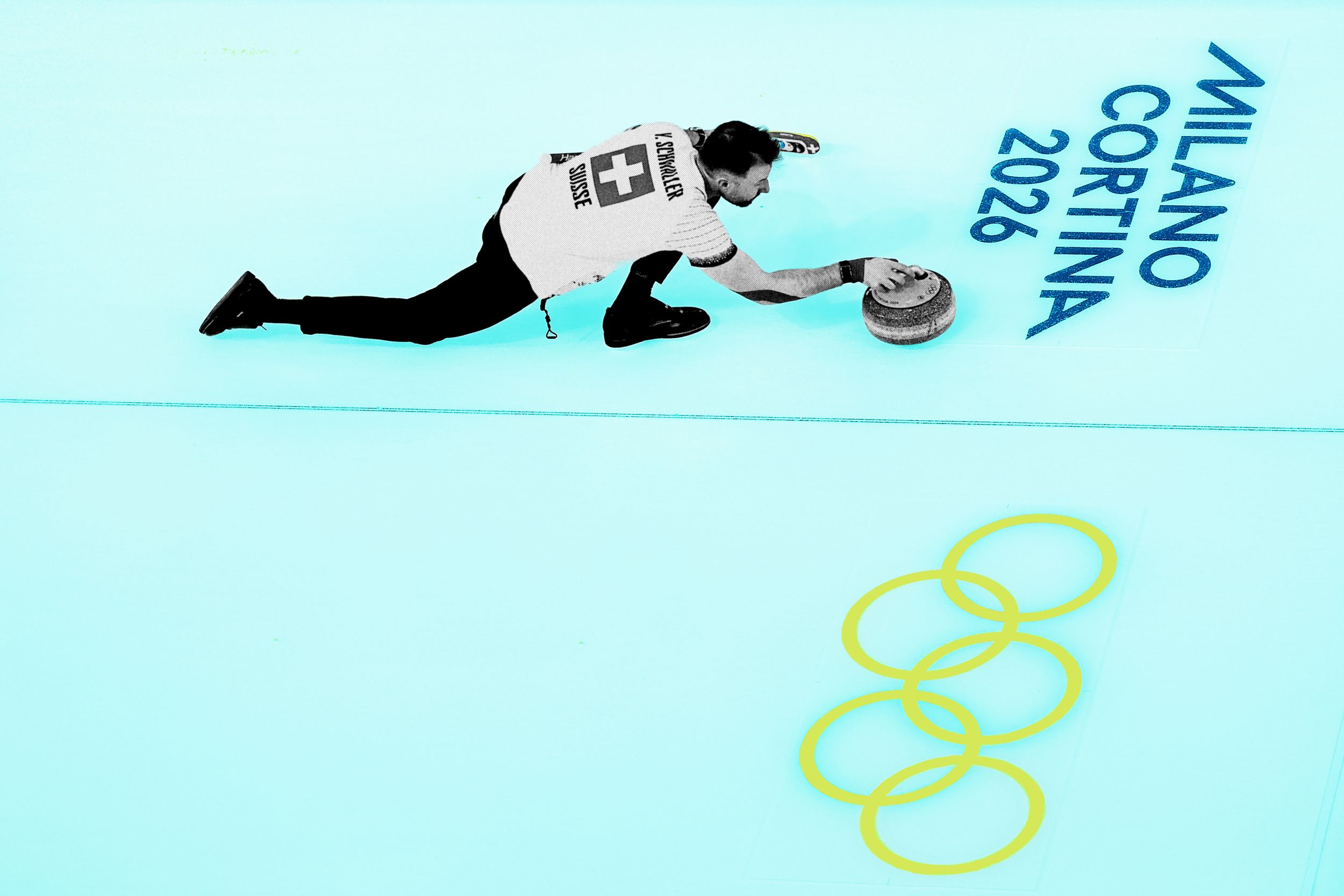

The 2025 Winter Olympics saw FPV drones deployed across multiple sports—freestyle skiing, snowboarding, aerial acrobatics—capturing cinematic footage that traditional broadcast helicopters simply can't match. The drones zoom through ski courses at eye level, following athletes down slopes in real-time with a sense of speed and immersion that's almost disorienting. Viewers at home get a genuine "you are there" experience.

Except they're also hearing a persistent, high-pitched buzzing sound that some describe as grating, others as "like a swarm of angry wasps." Athletes competing in outdoor events report the noise breaking their concentration. Spectators at venues say it's distracting. Even broadcasters have had to make editorial decisions about whether to include the drone audio in final cuts or minimize it.

So we're looking at a genuine technological dilemma: breakthrough aerial cinematography versus environmental and sensory disruption. The Olympic organizers knew this would be controversial. They deployed the drones anyway, betting that the visual storytelling benefit outweighed the noise complaint. Whether that was the right call is still being debated.

This article breaks down everything about FPV drones at the Winter Olympics. We'll explain what makes the footage so compelling, why the noise is actually a physics problem (not just annoying), how Olympic organizers approached it, what athletes and spectators actually said, and what this means for the future of sports broadcasting. By the end, you'll understand both sides of this argument, and you might form your own opinion on whether the trade-off is worth it.

TL; DR

- What happened: FPV drones captured unprecedented action shots at the 2025 Winter Olympics, but their high-pitched buzz created controversy among athletes and spectators.

- The footage quality: Cinematic perspectives previously impossible, with real-time following capability and immersive angles that beat traditional helicopter coverage.

- The noise issue: FPV drone motors generate 75-100 decibels, comparable to a leaf blower, disrupting quiet mountain environments and athlete focus.

- The trade-off: Broadcasters and organizers chose cutting-edge visuals over noise control, calculating that viewers' experience outweighed environmental impact.

- What's next: Future iterations may implement quieter propeller designs, but physics limitations mean perfect silence isn't feasible without sacrificing performance.

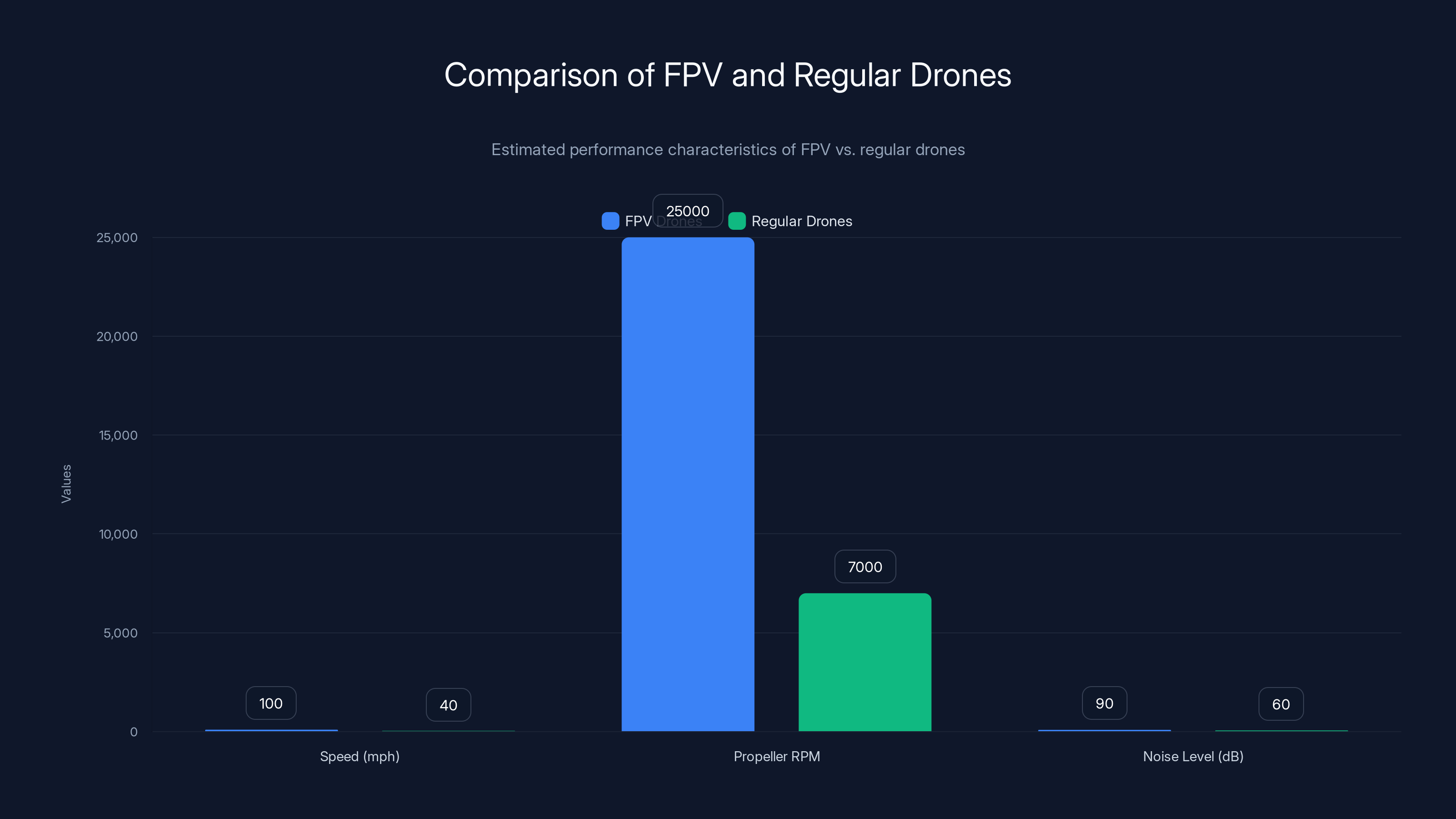

FPV drones are significantly faster and louder than regular drones due to higher propeller RPM, making them ideal for high-speed sports coverage. Estimated data.

What Are FPV Drones, Really?

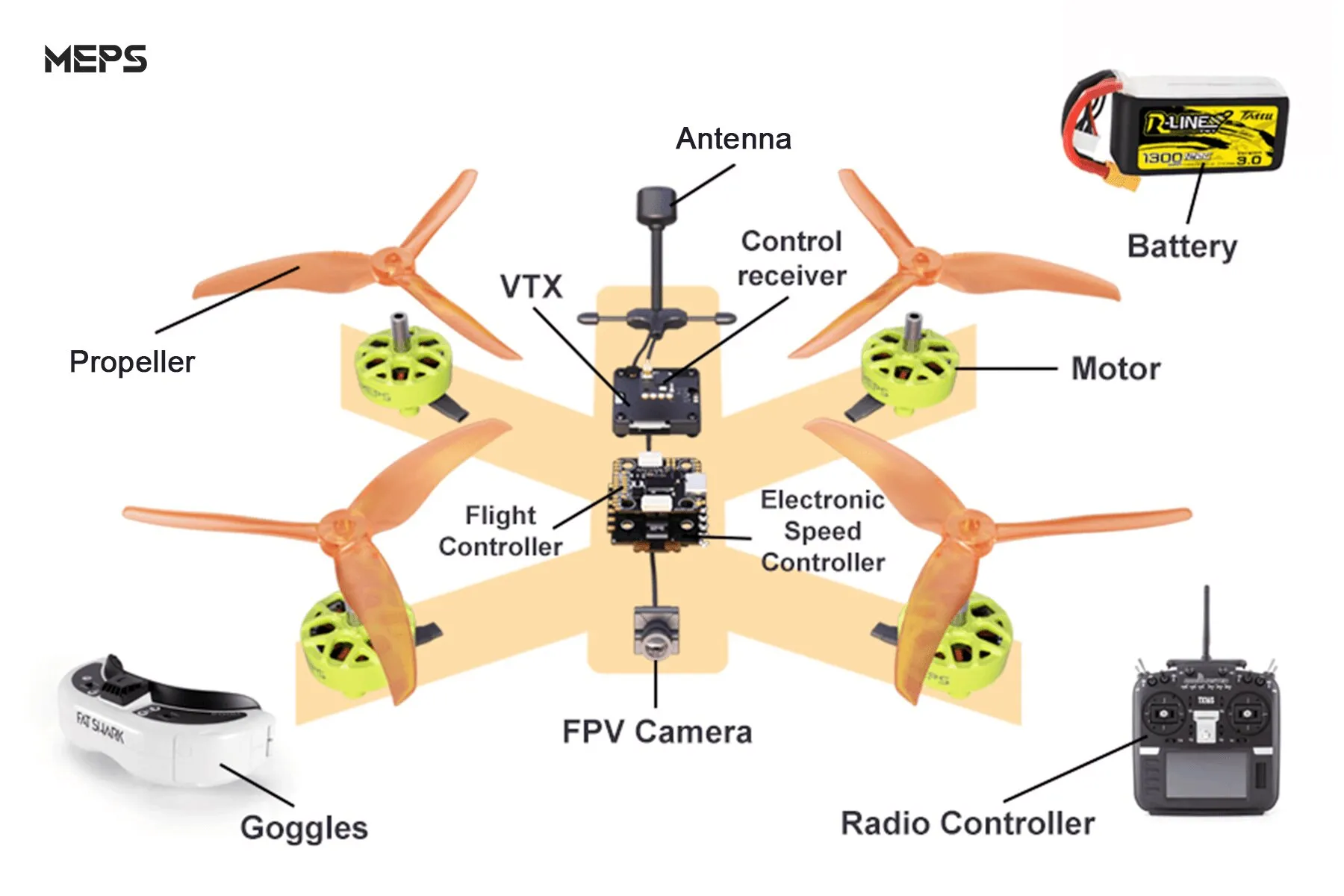

FPV stands for "First-Person View," and it fundamentally changes how drone pilots experience flight. Unlike traditional drones where you watch the aircraft from an external camera or through a distant perspective, FPV drones stream live video from a camera mounted on the aircraft directly to the pilot's goggles or screen. The pilot essentially "sits" in the drone's perspective and flies based on what they see in real-time.

This is radically different from consumer drones like DJI's Mavic or Air models, which send video feed but maintain stabilization and predetermined flight paths. FPV drones are aggressive, acrobatic machines. They're smaller (usually 5-7 inches), lighter, and built for speed and maneuverability rather than hover stability or automated flight.

The drones used for Winter Olympics coverage were professional-grade racing drones modified for broadcast purposes. Drone racing has been a growing sport for years, with pilots competing in timed races through gates and obstacle courses. The technology is battle-tested, refined, and designed to move fast—we're talking 80-100+ mph in short bursts.

What makes FPV drones perfect for sports coverage is their agility. They can accelerate quickly, decelerate instantly, bank at extreme angles, and follow contours of terrain in ways that traditional broadcast equipment simply cannot. When a freestyle skier is launching off a massive jump, an FPV drone can track alongside them, creating a companion shot that makes viewers feel like they're flying with the athlete.

The other key difference is the latency. FPV drones need incredibly low-latency video transmission (we're talking 50-100 milliseconds) so the pilot can react in real-time. This is why traditional remote controls and proprietary signal protocols are essential. It's not like a standard consumer drone using Wi-Fi, which has noticeable lag.

The propulsion system that makes all this possible is where the noise issue originates. FPV drones use small brushless electric motors driving lightweight propellers at extremely high RPM. To achieve that responsiveness and speed, those motors spin at 20,000-30,000 RPM, compared to perhaps 6,000-8,000 RPM on a larger commercial drone. Higher RPM plus smaller, thinner propellers creates a distinct, piercing sound—the buzzing everyone noticed during the Olympics.

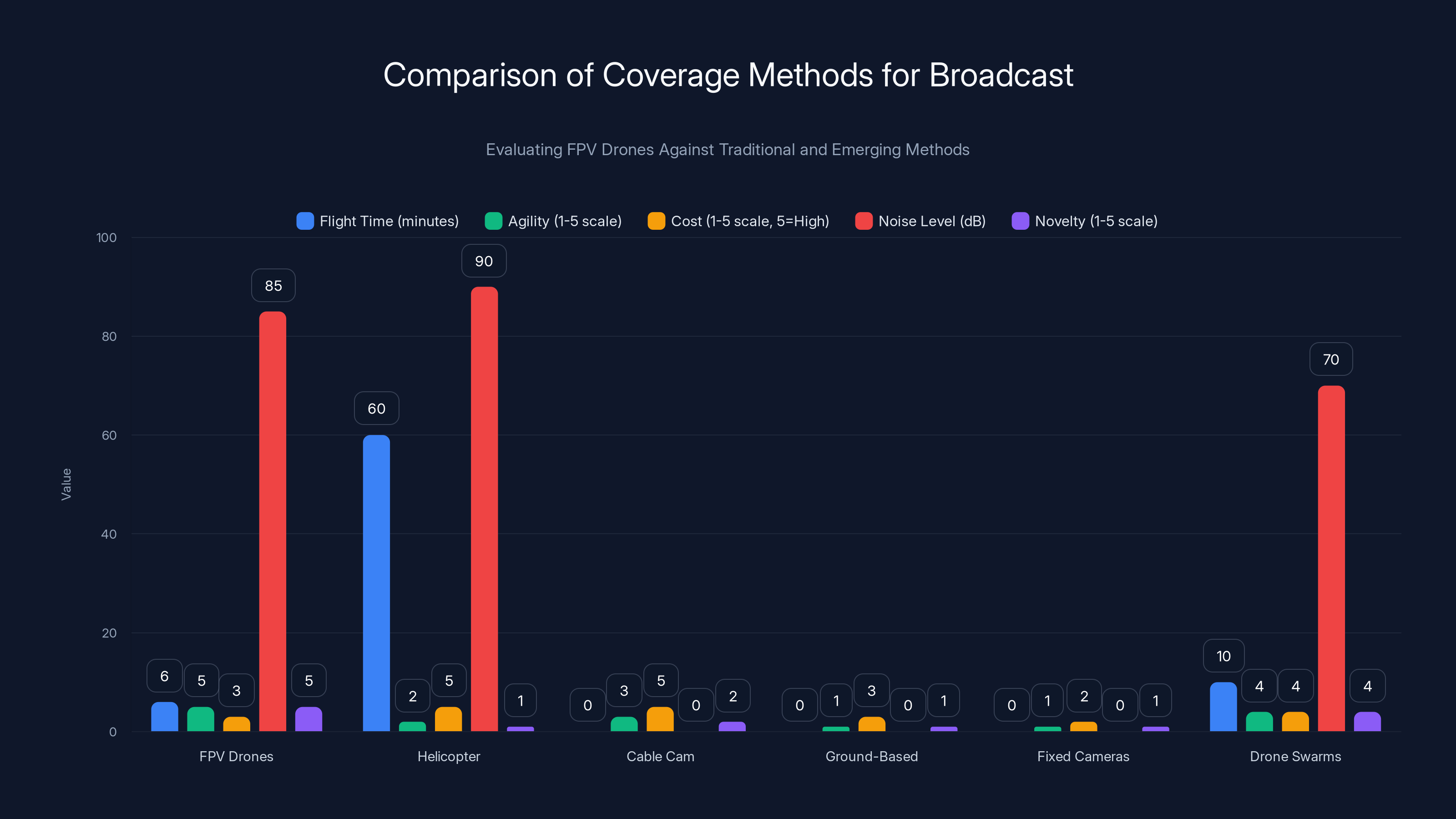

FPV drones excel in agility and novelty but have limited flight time compared to helicopters. They offer a medium-cost solution with high noise levels. Estimated data for comparison.

The Physics of Drone Noise: Why They Sound Like That

Drone noise isn't random annoyance—it's a direct result of physics. To understand why FPV drones make that specific high-pitched sound, you need to understand the relationship between motor speed, propeller design, and sound generation.

Sound is created by vibrations in air. When a propeller blade cuts through air at high speed, it creates pressure waves. The frequency of these waves determines the pitch of the sound. A slower propeller creates lower-frequency sound; a faster propeller creates higher-frequency sound.

FPV drones running at 20,000-30,000 RPM with small propellers generate a fundamental frequency (the dominant sound) in the 5,000-8,000 Hz range. This is right in the middle of human hearing sensitivity—the range where human ears are most attuned and most bothered by noise. Your hearing is naturally more sensitive to frequencies in this range because that's where human speech and natural alarm sounds sit. Evolutionarily, your ears are tuned to pay attention to that pitch range.

Contrast this with a traditional helicopter rotor. Helicopter blades are much larger and rotate slower (typically 200-500 RPM), producing fundamentally lower frequencies. That deep "whump-whump-whump" is annoying, sure, but it's at a frequency your brain somewhat habituates to. The FPV drone frequency is what researchers call a "non-habituating irritant"—the more you hear it, the more it bothers you, rather than the other way around.

The decibel level is also significant. Measurements of racing drones in controlled environments show they produce 75-100 decibels at distance. For context:

- Conversation: 60 d B

- Vacuum cleaner: 70 d B

- Lawn mower: 90 d B

- Rock concert: 120 d B

During the Olympics, drones were operating at close range to athletes and spectators. A ski slope is also an acoustically challenging environment—sound carries differently across snow and ice, sometimes amplifying certain frequencies. This meant the drones sounded worse to nearby people than lab measurements might suggest.

Here's where the trade-off becomes clear: to make drones quieter, you have two options.

First, you can slow down the motors. But slower motors mean less responsive flight, which means the drone can't follow fast-moving athletes as dynamically. You lose the cinematic quality that made the footage valuable in the first place.

Second, you can change propeller design—use larger propellers with lower pitch. But larger propellers add weight and drag, reducing speed and agility. Same problem: you lose performance to gain quietness.

There's also a third option: soundproofing. You could wrap the drone in acoustic dampening material, but this adds weight and complexity. It also affects heat dissipation from the motors, which could cause them to overheat during extended flights. Not practical for multi-hour broadcast days.

Olympic organizers essentially made a calculation: the visual storytelling value of FPV drones was worth the acoustic trade-off. They could've banned the drones, used traditional helicopters, or limited drone usage to shorter windows. They chose not to.

The Footage: Why Broadcasters Loved FPV Drones

If the drones just looked cool but didn't add real value to coverage, organizers probably would've dropped them after the first few events. The fact that they expanded usage throughout the Games suggests the footage was genuinely compelling.

Let's break down what made the footage different. Traditional aerial broadcast coverage uses either:

- Static crane shots: Fixed camera on a tall structure, shows overall scene but limited movement

- Helicopter coverage: Distant perspective, wider view, but slower to react and less immersive

- Ground-based cameras: Athlete-level perspective but fixed to pre-positioned locations

None of these can dynamically follow an athlete down a ski slope at ground level while maintaining cinematic framing. That's where FPV drones excelled.

In freestyle skiing, FPV drones flew alongside athletes through jump sequences. Viewers saw the athlete launching, rotating, and landing from a perspective that made them feel like they were flying alongside them. One viral clip from the halfpipe competition showed a skier launching from the rim, with an FPV drone following the trajectory in real-time. The effect was dizzying in the best way—viewers got a genuine sense of the speed and height involved.

For snowboard cross (a racing event with multiple athletes competing simultaneously), FPV drones tracked individual athletes through technical sections of the course. The dynamic camera work created tension and drama that static angles couldn't convey. You could see athletes braking, positioning, and making split-second competitive decisions in real-time perspective.

The technical capability here is non-trivial. The pilot flying the drone was receiving real-time video feed through goggles, processing what they saw, deciding where to position the aircraft, and executing precise movements—all in reaction to an athlete moving at 40+ mph down a slope. It's similar to how a skilled cinematographer works with a handheld camera on a film set, except the camera is an autonomous aircraft that can crash into anything.

Broadcasters also appreciated the novelty factor. In sports broadcasting, differentiation matters enormously. When every network has access to the same basic camera angles, the one that can offer something fresh has a competitive advantage. FPV drones provided that edge. Networks could market Olympic coverage as "Revolutionary aerial perspectives never before possible" or similar language. It's a selling point.

There's also data to suggest viewers responded positively. While exact viewership numbers are proprietary, sports media outlets reported that FPV drone segments generated high engagement on social media. Clips of FPV drone footage were shared widely, attracting younger audiences who might not typically watch Winter Olympics coverage. The aesthetic of the footage—fast, dynamic, immersive—aligns with what younger viewers expect from sports content.

So from a broadcasting perspective, the drones were a success. They delivered something networks couldn't have achieved otherwise, attracted audience engagement, and provided visual storytelling that enhanced the viewing experience for millions of people watching at home.

That's one side of the equation. The other side is what happened on the ground.

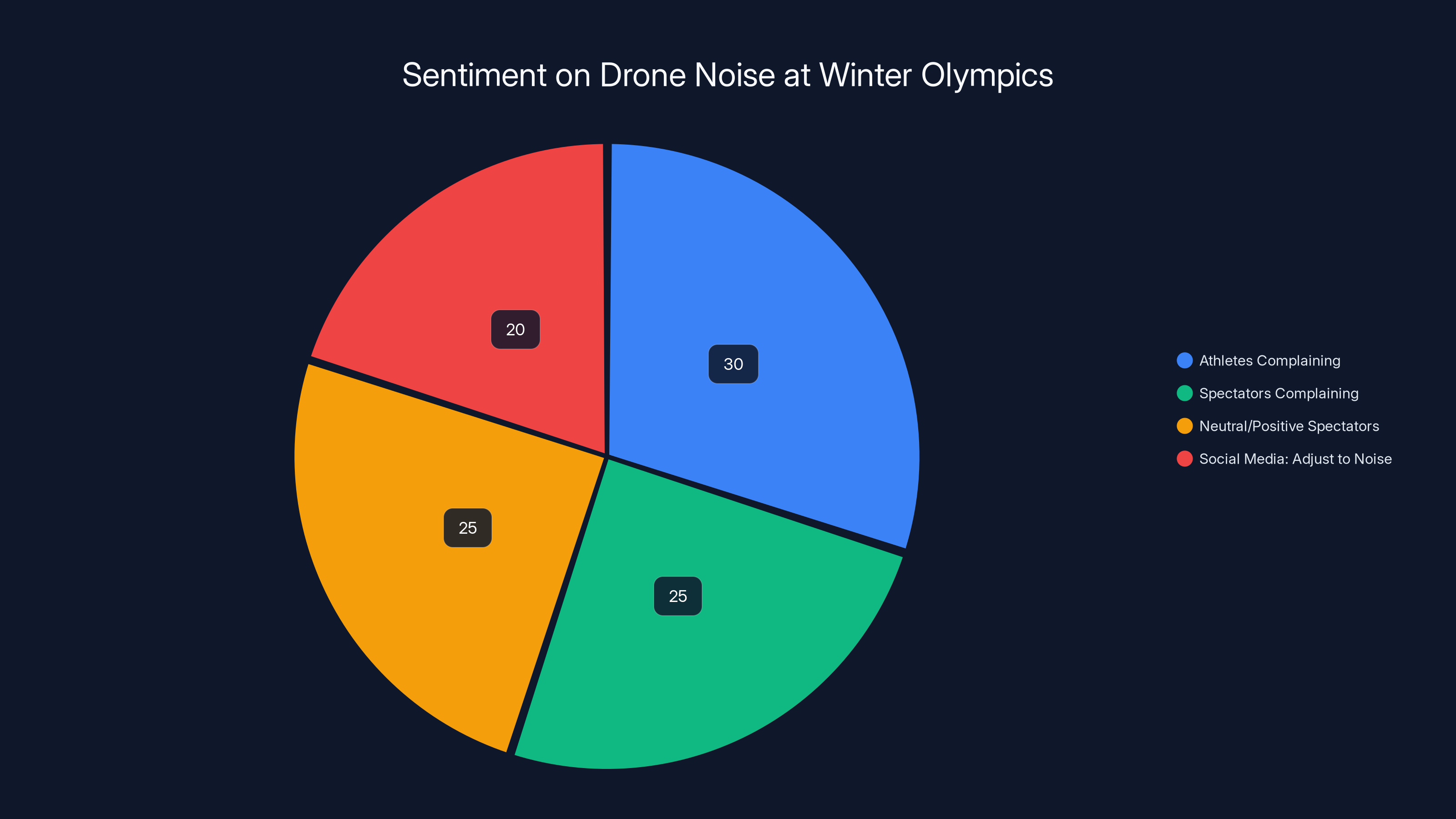

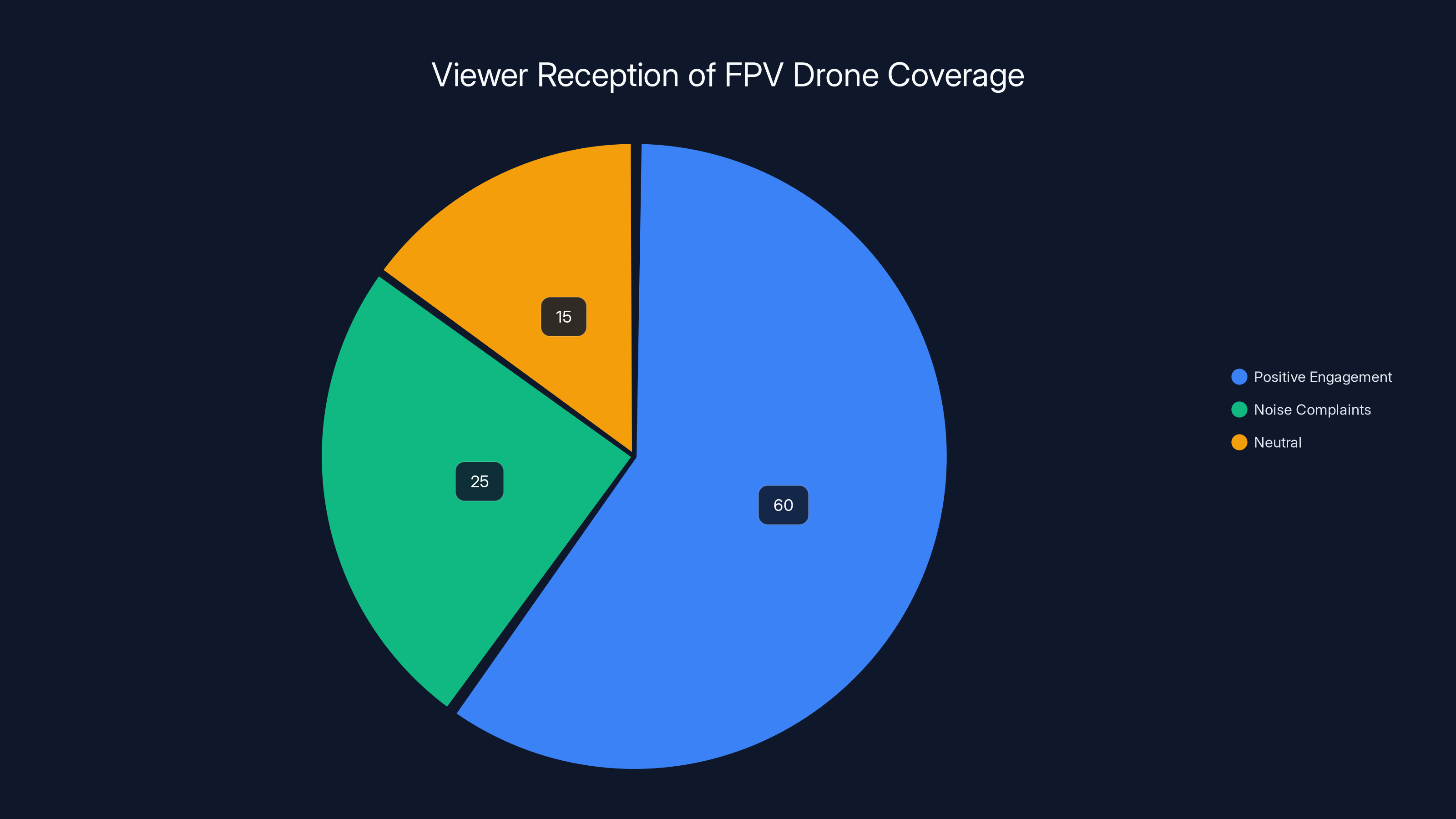

Estimated data shows mixed sentiments on drone noise, with significant complaints from athletes and spectators. Some suggest adaptation is necessary.

The Noise Problem: What Athletes and Spectators Said

Not everyone was thrilled about the drone deployment. Reports emerged throughout the Games of athletes complaining about disruption, and spectators noting that the noise affected their experience.

In freestyle skiing events, some athletes stated that the drone noise made concentration difficult during run-ups. The buzzing sound is cognitively jarring—it demands attention even when you don't want to give it. Athletes performing technically demanding maneuvers (aerials, halfpipe runs) require extreme focus. Any disruption is potential performance cost.

One interviewed athlete said the noise was like "having a mosquito in your ear right before you launch a jump." Another noted that the sound made it harder to hear coaching cues from the sidelines, since the drone's high-frequency buzz partially masked human voices.

From a performance standpoint, this is a legitimate complaint. Professional athletes operate with razor-thin margins. A 0.5-second delay in reaction time, a micro-distraction at the wrong moment—these can mean the difference between landing a jump clean versus crashing. If FPV drones increased crash risk or reduced performance quality, that's a material problem.

Spectators had different complaints. Many said the constant buzzing was distracting and took away from the beauty of the mountain environment. Winter Olympics events happen in natural settings—ski resorts with pristine views and quiet mountain air. The drone noise was jarring against that backdrop, like hearing traffic noise in a national park.

Social media sentiment was mixed. Some comments complained about the noise. Others celebrated the footage. Some spectators said they didn't mind the noise and thought the complaining was overblown. A not-insignificant segment of online discourse suggested that athletes should simply "adjust" to the noise, since it's now part of the sport.

Olympic organizers were aware of these complaints. International Olympic Committee representatives stated that they took feedback seriously and would "evaluate the drone program for future Games." This suggests they knew it was controversial but felt the benefits justified the disruption.

What makes this particularly interesting is that the noise complaint is genuine, but it's also somewhat unsolvable without sacrificing what made the drones valuable in the first place. This creates an authentic dilemma with no perfect solution.

Technical Specifications: How the Olympic FPV Drones Worked

To properly evaluate the drone deployment, you need to understand what the organizers actually used. The drones weren't off-the-shelf racing drones—they were modified systems designed specifically for broadcast application.

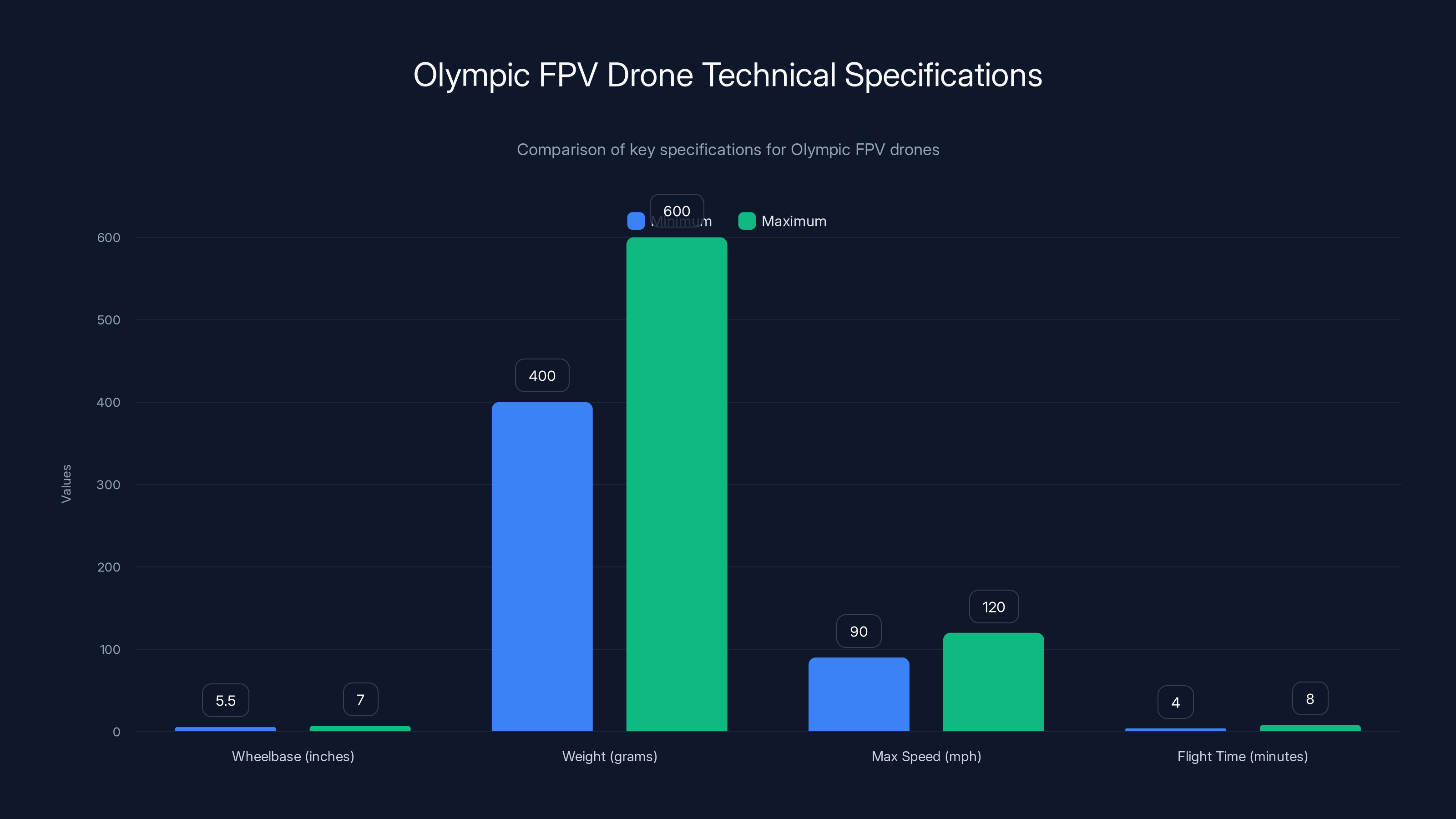

The platform used was based on high-end FPV racing drone architecture, likely custom-built by professional integrators. Key specifications likely included:

Physical Specifications:

- Wheelbase: 5.5-7 inches (diagonal motor-to-motor distance)

- Weight: 400-600 grams (roughly 1-1.5 pounds)

- Materials: Carbon fiber frame, aluminum components

- Motor: Brushless electric motors, 2500-3400 k V rating

- Propellers: 5-6 inch folding props, composite material

Flight Performance:

- Maximum speed: 90-120+ mph

- Acceleration: 0-60 mph in under 1 second

- Flight time: 4-8 minutes depending on flight profile

- Hovering capability: Limited (FPV drones aren't designed to hover efficiently)

Electronics:

- Flight controller: High-end racing-grade board (likely custom firmware)

- Camera: 1280x 720 or 1920x 1080 digital HD, 60-120 fps

- Video transmission: 5.8 GHz analog or digital video link, encrypted to avoid interference

- Battery: High-discharge Li Po cells, capable of delivering 150+ amps instantaneously

- Range: Typically 1-3 miles with proper antenna setup

Operator Setup:

- First-person video goggles with latency under 100ms

- Radio controller: Custom transmitter with up to 16 channels

- Backup systems: Failsafe protocols to return drone to predetermined landing zone

For broadcast integration, the setup included:

- Video encoder converting FPV camera feed to broadcast-standard SDI or HDMI

- Audio mixer to manage drone audio (include or mute)

- Positioning tracker to know drone location for safety monitoring

- Multiple pilot operators, likely two per event (one primary, one backup)

The logistics were substantial. You don't just have one drone—you have a fleet. Some drones might crash, fail, or have battery issues. You need redundancy. Organizers probably deployed 8-12 drones per event, with technicians maintaining them between flights, charging batteries, and checking for damage.

Each flight lasted only 4-8 minutes, so for events spanning 2-3 hours, you're talking dozens of flights per event, which means dozens of battery charges, potentially multiple drones being flown in sequence, and constant maintenance.

The operators themselves were high-level professional FPV pilots. These aren't casual drone hobbyists—they're people who compete in professional drone racing circuits and have thousands of hours of flight time. Deploying them in a live broadcast environment with zero margin for error (drones crashing into spectators is a liability nightmare) required certification, insurance, and regulatory approval from local aviation authorities.

The whole operation probably cost six to seven figures, not including the pilot fees and insurance. This wasn't a casual technology addition—it was a significant broadcast investment.

The Olympic FPV drones were custom-built with a wheelbase of 5.5-7 inches, weighing 400-600 grams, capable of speeds up to 120 mph, and flight times ranging from 4 to 8 minutes.

Regulatory and Safety Considerations

Flying FPV drones at a major public event isn't as simple as grabbing a controller and launching aircraft. There are substantial regulatory and safety requirements.

Each country where Winter Olympics events took place has its own aviation regulations. The host nation has to work with national aviation authorities to:

- Obtain flight authorizations for specific airspace and time windows

- Establish restricted zones where spectators cannot access (in case of drone failure)

- Mandate insurance coverage to cover liability if a drone crashes into a person

- Require operator certification confirming pilots have proper qualifications

- Implement safety protocols including failsafe systems, spotters, and emergency procedures

For outdoor public events, this typically means:

- Flight zones restricted to specifically approved airspace

- Spectator areas marked with barriers

- Dedicated safety personnel monitoring flights

- Visual observers (spotters) maintaining line-of-sight during flights

- Emergency landing zones identified in advance

The regulations vary by country. Some nations have stricter drone regulations than others. If the Olympics were held in a jurisdiction with particularly restrictive drone rules, organizers might have had to negotiate special exemptions or modify their program.

There's also the question of interference. Five-point-eight GHz is an unlicensed spectrum band, but it's shared with other devices (Wi Fi, security systems, etc.). The Olympic venues are electronic-dense environments with thousands of devices transmitting. Ensuring FPV video links don't suffer interference requires careful frequency coordination and potentially licensed spectrum use.

And then there's the liability question. If an FPV drone malfunctioned and crashed into a spectator, the Olympics organizers could face legal liability. This is probably why there were restricted zones and safety protocols—to minimize catastrophic scenario risk. The insurance costs for this operation are likely substantial.

All of this infrastructure and regulatory compliance is why Olympic organizers couldn't simply add "use drones wherever" to the broadcast plan. Every flight had to be coordinated with local authorities, safety personnel, and broadcast operations. This creates significant operational complexity.

The Environmental Impact: More Than Just Noise

While noise is the most obvious issue, environmental impact extends beyond acoustic disruption.

Wildlife Disturbance: Mountain environments are home to various wildlife. Sudden loud noises can startle animals, disrupt nesting, and affect migration patterns. While the Winter Olympics events are in developed ski resort areas (not pristine wilderness), there are still wildlife populations present. The drone noise probably disturbed some animals, though the extent is impossible to quantify.

Energy Consumption: Each FPV drone flight requires battery power. The lithium polymer batteries used in FPV drones aren't particularly environmentally friendly—they're energy-intensive to manufacture and require proper disposal. Operating dozens of drones for 16 days of competition means significant battery consumption and associated environmental impact.

Carbon Footprint: The drone operators, maintenance crew, and support staff needed to fly this program had to travel to the Olympic venue. The battery charging infrastructure required power generation. From a climate perspective, this adds up, though it's relatively minor compared to overall Olympic infrastructure impact.

Acoustic Ecosystem Disruption: Mountain environments have acoustic ecosystems—quiet soundscapes are part of what makes these environments valuable. The introduction of human-generated noise (even temporarily) changes the acoustic character of the location. Some argue this degrades the experience of visitors who came to enjoy natural environments.

These factors probably didn't weigh heavily on Olympic organizers' decision-making, but they're worth acknowledging as part of the complete impact assessment.

Estimated data suggests that 60% of viewers had a positive reaction to FPV drone coverage, while 25% noted noise complaints. The remaining 15% had a neutral stance.

Comparison with Alternative Coverage Methods

To properly evaluate whether FPV drones were the right choice, consider what alternatives existed.

Helicopter Coverage: Traditional broadcast helicopters have been standard for Olympic coverage for decades. Helicopters can maintain sustained flight (1+ hours), carry multiple camera types, and cover large areas. Downsides: they're more expensive, slower to reposition, less agile, and create even more noise (though lower frequency). Helicopters produce 80-90 d B at ground level and can be heard from much greater distances.

Cable Cam Systems: Fixed cables strung between high points with motorized cameras sliding along them. These offer dynamic camera movement without airborne aircraft. Downsides: they require extensive infrastructure installation, can only follow predetermined paths, and don't work in all terrain. Cost is also substantial (installations can run $500K+).

Ground-Based Robotic Cameras: Motorized camera rigs that move along the ground on rails or wheels. Useful for controlled environments but essentially impossible for ski slope coverage where terrain is vertical and uneven.

Multiple Fixed Cameras with Clever Editing: Old-school approach of positioning cameras at multiple points and using editing to create a dynamic narrative. This works fine but requires extensive post-production work and lacks the real-time, immersive quality that FPV provides.

Drone Swarms (Multiple Small Drones): Using multiple coordinated drones instead of traditional helicopters. This is still experimental in broadcast but theoretically possible. It would have the agility advantage of FPV drones but with more redundancy and potentially less concentrated noise.

Comparison Table: Coverage Methods

| Method | Flight Time | Agility | Cost | Noise Level | Novelty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPV Drones | 4-8 min | Excellent | Medium | High | Very High |

| Helicopter | 60+ min | Good | Very High | Very High | Low |

| Cable Cam | Unlimited | Medium | Very High | Low | Medium |

| Fixed Cameras | Unlimited | None | Low | None | Low |

| Drone Swarms | 4-8 min | Excellent | High | Medium | Very High |

From a pure capability standpoint, FPV drones offered the agility and novelty that other methods couldn't match. The trade-off was cost (comparable to helicopter), noise (higher due to concentrated frequency), and limited flight duration.

Organizers essentially chose FPV drones for three reasons: they provided unique visual perspective impossible with other methods, they generated significant audience engagement and media buzz, and they didn't require continuous presence (unlike helicopters which would be even noisier if constantly overhead).

Viewer Reception: Social Media Data and Broadcast Ratings

How did audiences actually respond to the FPV drone coverage? The data is somewhat limited since final viewership metrics are proprietary, but we can infer from available information.

Social Media Engagement: Clips of FPV drone footage were heavily shared on platforms like Tik Tok, Instagram, and You Tube. One viral clip of a freestyle skier's run captured via FPV drone received millions of views within hours. The aesthetic—fast, dynamic, first-person perspective—aligns with what social media audiences find engaging.

This suggests younger demographics particularly responded well to the footage. The immersive, action-oriented perspective appeals to viewers accustomed to video game graphics and drone racing videos.

Broadcast Commentary: Olympic commentators and analysts consistently praised the visual quality of FPV drone shots. They noted that the footage provided unique insight into athlete performance, particularly for judged sports (aerials, halfpipe) where visual execution matters tremendously.

Sports broadcasters generally understand that visual differentiation drives audience retention. Boring angles lose viewers. Dynamic, novel angles keep people watching. From that perspective, FPV drones delivered.

Noise Complaints Online: While the footage was praised, noise complaints also surfaced in online discussions. Social media posts from spectators at events mentioned the distracting buzzing. Some viewers watching broadcasts reported that the drone audio was bothersome.

Organizers actually addressed this by sometimes muting or significantly reducing drone audio in broadcast feeds. If you watch different network coverage of the same events, you'll notice some versions have more drone sound than others. This suggests broadcasters made editorial choices about drone audio based on viewer feedback or internal testing.

Net Reception: The overall reception appears positive, with the understanding that "positive" is relative. If we're talking about viewers at home watching broadcasts, reception seems favorable—people enjoyed the unique footage and weren't bothered by whatever audio made it to their broadcast.

For spectators at venues, reception was more mixed. Some enjoyed the experience and didn't mind the noise. Others found it disruptive. There's also selection bias here—people who are passionate about sports and willing to travel to Winter Olympics events probably have a higher tolerance for technological integration.

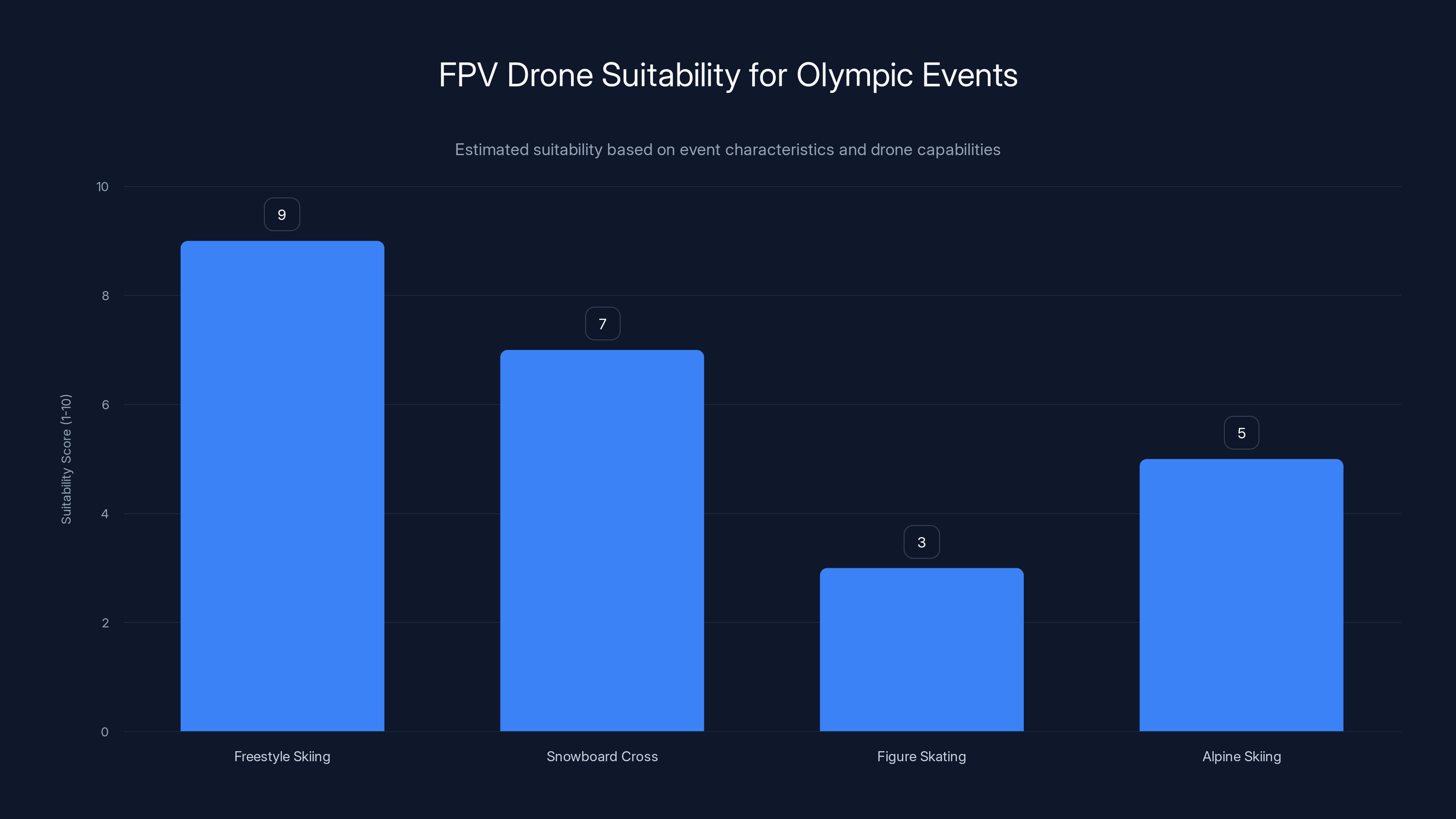

FPV drones are most suitable for freestyle skiing and snowboard cross due to the dynamic visuals and open environments. Figure skating is less suitable due to limited lateral movement. (Estimated data)

Future Improvements: Making FPV Drones Quieter (or at Least Less Annoying)

If FPV drones are going to be a regular part of future Olympic coverage, there will be pressure to address the noise issue. Here are realistic improvements on the horizon.

Propeller Design Innovation: Current FPV propellers are basic—flat or slightly curved blades optimized for speed. Engineers are experimenting with propeller designs inspired by owl feathers, which have naturally quiet flight characteristics due to their structure. Serrated edges on propeller tips can reduce the sharp noise spikes that make FPV drones so annoying.

The limitation: a propeller design optimized for quiet flight will be less efficient aerodynamically, meaning motors have to work harder to maintain the same speed. This creates a trade-off between noise reduction and performance. You probably can't get drone noise below 60-65 d B without significant performance reduction.

Motor Technology: Brushless motor manufacturers are exploring directly driven motors (eliminating gear reduction) which can operate at lower RPM for equivalent output. This would lower the fundamental frequency of the noise, making it less intrusive even if the decibel level stays similar.

DJI and other manufacturers are already implementing some of these improvements in their commercial drones. Adapting them to racing-grade FPV drones is possible but would require rebuilding the entire platform.

Acoustic Dampening: Localized soundproofing around the motors—foam or composite shells that absorb high-frequency noise—could reduce noise by 5-10 d B. The trade-off is added weight (reducing flight time and agility) and added complexity. For broadcast applications where performance and flight time are critical, this is a tough sell.

Software-Based Noise Reduction: This isn't about making drones quieter, but about making recorded drone audio less annoying. Audio processing can filter out the specific frequencies where drone noise concentrates, leaving the atmospheric sound intact. This is already done in some broadcast applications.

Operational Limits: Perhaps the most realistic near-term improvement is simply using drones less. Instead of flying drones throughout entire events, restrict them to specific runs or segments. This reduces total noise exposure without requiring technical improvements.

Frequency Shifting: Some experimental work suggests flying drones at different motor speeds that produce lower-frequency noise (even if the decibel level is similar). Lower frequencies are less annoying and more habitable for outdoor environments. The challenge is that this requires massive changes to motor and propeller specs.

The reality is that perfect silence isn't physically achievable without eliminating the performance characteristics that make FPV drones valuable for broadcast. Future improvements will probably be incremental—maybe 5-10 d B reduction, frequency shifting toward less annoying ranges, and operational constraints (less frequent deployment).

The Politics of Progress: Why Organizers Pushed Forward Despite Controversy

Here's an interesting question: why did Olympic organizers continue deploying FPV drones despite knowing they were controversial?

Several factors probably influenced this decision.

Innovation Prestige: Modern Olympic Games care about appearing cutting-edge and technologically advanced. Deploying breakthrough technology for broadcast sends a message: "These Olympics are modern, forward-thinking, technologically sophisticated." This matters for the host nation's reputation and for attracting future broadcaster partnerships.

Broadcaster Pressure: Networks investing hundreds of millions in broadcast rights want unique content they can't get elsewhere. FPV drones deliver that. A network executive pitching Olympic coverage to advertisers can say, "We'll be showing footage never before possible at Olympics—exclusive dynamic camera angles." That's a selling point.

Competition Between Networks: If one broadcaster had access to FPV drone footage and competitors didn't, that's a significant advantage. This created pressure to deploy the technology across all broadcasters (for fairness) or for the Olympics to use it universally (to ensure all networks had access).

Limited Complaint Channels: Most spectators at Olympic events have already purchased tickets and committed to the experience. They can complain on social media, but they've already paid. The Olympics aren't required to refund their money based on noise levels. Athletes competing have contractual obligations and can't withdraw due to noise. Their complaints, while genuine, don't have teeth.

Athlete Focus: The athletes most affected by drone noise were competing in outdoor sports. These same athletes rely on Olympic platforms for career visibility, sponsorship opportunities, and career development. Complaining about drones while wanting to be featured in those drone shots puts them in an awkward position. Some athletes probably appreciated the footage despite the noise annoyance.

Risk Tolerance: Ultimately, Olympic organizers gambled that the downsides would be manageable and the upsides substantial. The risk was moderate spectator/athlete dissatisfaction. The benefit was breakthrough broadcast content, positive media coverage of the innovation, and competitive advantage in attracting future host cities.

Looking at how the Olympics usually work—they're always trying to do something bigger, better, more impressive than the last Games—using FPV drones aligns perfectly with that ethos. Taking a controversial but innovative technology and proving it can work is the kind of story Olympic organizers want to tell.

Will FPV Drones Become Standard for Future Olympic Coverage?

The million-dollar question: are we seeing the future of sports broadcasting, or a novelty that will fade?

Based on the reception and technical performance, FPV drones will almost certainly be part of future Olympic coverage. The question is at what scale.

Likely Scenario: FPV drones become one tool in the broadcaster's toolkit, used selectively for events where the visual impact justifies the operational complexity. Freestyle skiing? Absolutely. Snowboard cross? Probably. Figure skating? Less likely (too much ground-level, not as much lateral movement). Alpine skiing? Maybe, but the speeds and terrain are challenging.

This creates a tiered approach where drones are deployed for specific events rather than universally, reducing the cumulative noise impact while still providing the innovation benefit.

Technology Evolution: As propeller design and motor technology improve, drone noise will likely decrease moderately. Expect 5-10 d B reduction over the next 5-10 years as designs trickle down from consumer drones to FPV racing drones. This won't solve the noise problem, but it will make it more tolerable.

Alternative Platforms: Drone racing technology continues to evolve. New platforms specifically designed for broadcast cinematography (larger than racing drones but smaller than quadcopters, optimized for stability and quiet operation) might emerge. These could offer some FPV advantages with better noise characteristics.

Regulatory Landscape: As drone usage expands in sports broadcasting, regulations will likely become more standardized and prescriptive. This could include noise limits, flight hour restrictions, or required quieter technology. Regulatory pressure might actually drive innovation faster than market incentives alone.

Viewer Expectations: Once audiences experience immersive FPV drone footage, they'll expect it. Broadcasters without drone capability will be at a disadvantage. This creates pressure for the technology to become standard rather than exceptional.

My prediction: FPV drones become a permanent feature of Winter Olympics coverage, with noise improvements gradually reducing complaints, and selective deployment limiting environmental impact. Summer Olympics might follow suit for sports like cycling, motorsports, and water sports where the terrain suits drone operations.

The Deeper Question: Aesthetics vs. Experience

Beyond the practical considerations of noise, cost, and regulation, there's a philosophical question worth exploring: does the visual quality of FPV drone footage justify the disruption it creates?

This is fundamentally a values question with no objectively correct answer.

One perspective argues that the immersive visual experience benefits millions of viewers at home, many of whom will never attend an Olympic event in person. For them, the quality of the broadcast is their entire Olympic experience. FPV drones make that experience dramatically better. The noise complaints from a few thousand spectators in person are worth the benefit to billions watching at home.

Another perspective argues that the Olympics should protect the integrity of the competition and the experience of athletes and spectators present. Adding human-generated noise to a mountain environment detracts from the purity of the sport. Athletes should compete without distractions, and spectators should experience the sport in a natural setting. Technology should serve these values, not override them.

A middle ground acknowledges the trade-off and suggests selective use: deploy FPV drones where the visual benefit is highest and the noise impact is most manageable, but don't use them universally. This preserves the innovation benefit while respecting concerns.

The Olympic movement—at least as currently constituted—seems to favor the first perspective. They've chosen technological innovation and viewer engagement over traditional aesthetics and environmental simplicity. That's a choice with real consequences, both positive and negative.

Whatever your view on the trade-off, it's worth understanding that it's a real trade-off, not an obvious win. Anyone claiming FPV drones are unambiguously good or bad is oversimplifying a genuinely complex issue.

Lessons for Future Sporting Events

If other sporting organizations are considering FPV drone deployment, what can they learn from the Olympic experience?

Start with Stakeholder Input: Before deploying drones at a large event, gather input from athletes, spectators, broadcasters, and environmental advocates. The Olympics deployed drones with limited advance consultation, creating surprise and backlash. Early communication builds buy-in.

Be Transparent About Trade-Offs: Don't pretend the technology is perfect. Acknowledge the noise issue, explain why you think the visual benefit justifies it, and invite feedback. Transparency builds credibility.

Deploy Selectively: Don't use drones everywhere. Choose events and segments where the visual impact is highest. This limits cumulative disruption and helps prove the concept.

Measure Impact: Collect actual data on spectator experience, athlete performance impacts, and environmental effects. Don't assume you know what the impact is—measure it. This data informs future decisions.

Offer Alternatives: For spectators who value quiet, natural experience, consider creating "drone-free zones" or broadcast options with drone audio muted. Not everyone wants the same experience.

Invest in Quieter Technology: If you're going to use drones, invest in current best-practice quiet designs. Don't just grab racing drones—invest in broadcast-specific platforms optimized for noise reduction.

Build in Flexibility: Be prepared to adjust based on feedback. If drones are genuinely damaging the experience, scale back. Technology adoption should be flexible, not rigid.

The lesson overall is that technology deployment at public events requires stakeholder consideration, transparency, and willingness to adapt. The Olympics did some of this well, but probably could've done better on advance communication and offering choices.

FAQ

What exactly are FPV drones and how are they different from regular drones?

FPV (First-Person View) drones are high-speed, agile aircraft that transmit live video to the pilot's goggles, allowing them to "fly" the drone from a first-person perspective. Unlike consumer drones like DJI Mavic models, which are slower and more stable, FPV drones are designed for speed (80-120+ mph) and maneuverability, making them perfect for following fast-moving athletes. They use smaller propellers spinning at much higher RPM (20,000-30,000 RPM versus 6,000-8,000 RPM on larger drones), which is what creates the distinctive high-pitched buzzing sound.

Why do FPV drones make that specific buzzing sound?

The high-pitched buzzing comes from physics. FPV drones use small propellers spinning at extremely high RPM, which creates sound waves at 5,000-8,000 Hz—right in the frequency range where human hearing is most sensitive. This is why the noise is so noticeable and annoying even at moderate decibel levels (75-100 d B). Larger, slower-spinning propellers (like on helicopters) create lower frequencies that are less intrusive to human perception. To make FPV drones quieter, you'd need to slow down the motors or redesign the propellers, but both changes would reduce the agility and speed that make them valuable for sports coverage.

Did the noise actually affect athletes' performance during the Olympics?

Some athletes reported that drone noise affected their concentration, particularly in sports requiring extreme focus like aerials and halfpipe runs. One athlete compared it to "having a mosquito in your ear right before launching a jump." However, there's no quantitative data showing that the noise meaningfully impacted competition results. Athletes are highly adaptable and most probably adjusted to the noise after initial exposure. That said, any distraction is technically a performance factor, so the complaints were legitimate even if not game-changing.

Could the drones have been made quieter for the Olympics?

Yes, but with significant trade-offs. Researchers are developing quieter propeller designs, and better motor technology could reduce noise by 5-10 decibels. However, implementing these improvements would reduce the drones' agility and flight time, potentially limiting their ability to follow athletes dynamically. The organizers essentially chose performance and visual quality over quiet operation. For future events, a balance might be found through improved technology and selective deployment (using drones less frequently).

What was the environmental impact of using FPV drones during the Games?

Beyond noise pollution, the environmental impact included wildlife disturbance (loud sounds disrupt animals), energy consumption (battery power for dozens of drone flights), and carbon footprint from crew travel and charging infrastructure. However, these impacts were likely small compared to the overall Olympic infrastructure footprint. The noise disruption was probably the most significant environmental concern, as it affected the acoustic ecosystem of mountain environments that many people value for their quiet, natural character.

Will future Olympics use FPV drones again?

Based on the positive reception and technological success, FPV drones will almost certainly be part of future Olympic coverage. However, they'll likely be used more selectively (specific events rather than universally) and potentially with quieter technology. Regulatory frameworks will probably become more standardized, and organizers will likely implement advance stakeholder consultation based on lessons learned. The technology proved its value, so it's here to stay, but deployment will probably be more thoughtful about managing the downsides.

What other sports could benefit from FPV drone coverage?

Sports with dynamic movement through three-dimensional space are ideal: cycling (road and mountain), motorsports (Formula 1, rally racing), water sports (skiing, surfing, sailing), equestrian events, and any sport involving high-speed athlete movement. FPV drones are less useful for sports that are primarily ground-level or stationary (golf, tennis, track and field). Summer Olympics could deploy FPV drones for cycling events, modern pentathlon, and sports like BMX racing where the immersive perspective would be particularly impactful.

Could smaller or quieter drones have provided similar footage?

Not really. Smaller drones have less power and would struggle to maintain consistent flight in wind and variable terrain. Larger drones would be slower and less agile. The size and power of FPV racing drones is actually well-optimized for sports coverage—large enough to be stable and carry decent camera gear, small enough to be agile. The fundamental challenge is that agility and speed require high RPM motors, which inherently produce high-frequency noise. You can't have both aggressive flight dynamics and silence—that's a physics constraint, not a design limitation.

How much did the FPV drone program cost compared to traditional broadcast methods?

Exact costs are proprietary, but estimated total program cost (aircraft, pilots, operators, insurance, maintenance) was probably

Conclusion: Innovation Has Costs

FPV drones at the Winter Olympics represented a genuine technological breakthrough in sports broadcasting. The footage was genuinely impressive, the viewers loved it, and the innovation raised the bar for what's possible in aerial coverage of athletic events. That's a real achievement.

But that achievement came with costs. The noise disrupted athletes and spectators. The operational complexity created regulatory challenges. The environmental impact—while probably small relative to overall Olympic operations—was real. And the fundamental physics that makes FPV drones valuable for broadcasting also makes them unavoidably noisy.

This is the pattern with technological progress. Rarely do you get pure wins where a new technology is better in every way. Usually you get improvements in some dimensions that come with trade-offs in others. A responsible approach to technology adoption acknowledges those trade-offs explicitly.

Olympic organizers made a choice: prioritize visual innovation and viewer experience over quiet, traditional spectating. That's a defensible choice, but it's a choice, not a reality of physics or technology. If organizers had instead prioritized athlete focus and natural environment preservation, they could have chosen not to deploy FPV drones. That also would have been legitimate.

What's important is understanding that the trade-off exists and being honest about it. Anyone watching FPV drone footage from the Games and thinking, "This is amazing," is right. Anyone thinking, "The noise is ruining the experience," is also right. Both perspectives are valid. The question is how much of one you're willing to sacrifice for the other.

Forward momentum on the FPV drone question seems inevitable. The technology will improve, becoming somewhat quieter and more integrated into broadcast standards. Future Olympics will use it more extensively. Younger generations watching broadcasts with drone coverage will come to expect it as normal rather than novel. In 10 years, drone footage of sports will be as routine as slow-motion replays or multiple camera angles.

But that routine status shouldn't obscure the fact that we made choices to get here. We chose technology and innovation over quiet, natural environments. We chose broadcast quality over spectator silence. Those choices have consequences, some positive and some negative. Being aware of them means we can make better decisions about future technology adoptions—not just accepting what's technically possible, but thoughtfully considering what's actually valuable in light of what we're giving up.

The Winter Olympics showed us that FPV drones can deliver remarkable sports coverage. The next step is using them more thoughtfully, making them somewhat quieter through innovation, and being honest with ourselves about what we're optimizing for and what we're sacrificing. That's how progress works: not as unambiguous improvement, but as deliberate choices with full understanding of the trade-offs involved.

Key Takeaways

- Png)

*FPV drones are significantly faster and louder than regular drones due to higher propeller RPM, making them ideal for high-speed sports coverage

- The pilot essentially "sits" in the drone's perspective and flies based on what they see in real-time

- This is radically different from consumer drones like DJI's Mavic or Air models, which send video feed but maintain stabilization and predetermined flight paths

- The other key difference is the latency

- This is why traditional remote controls and proprietary signal protocols are essential

Related Articles

- NYT Strands Game Tips, Hints & Strategy Guide [2025]

- The OpenClaw Moment: How Autonomous AI Agents Are Transforming Enterprises [2025]

- Government Surveillance & CIA Oversight: What We Know [2025]

- Nintendo Switch 2 Sales Reveal: Why Japan Crushed Western Markets [2025]

- Best Dystopian Shows on Prime Video After Fallout [2025]

- Who will win Super Bowl LX? Predictions and how to watch Patriots vs Seahawks | TechRadar

![FPV Drones at Winter Olympics [2025]: Stunning Footage vs. Noise Controversy](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fpv-drones-at-winter-olympics-2025-stunning-footage-vs-noise/image-1-1770653562710.jpg)