Golden Dome Missile Shield: How Trade Wars Block Allied Defense Plans

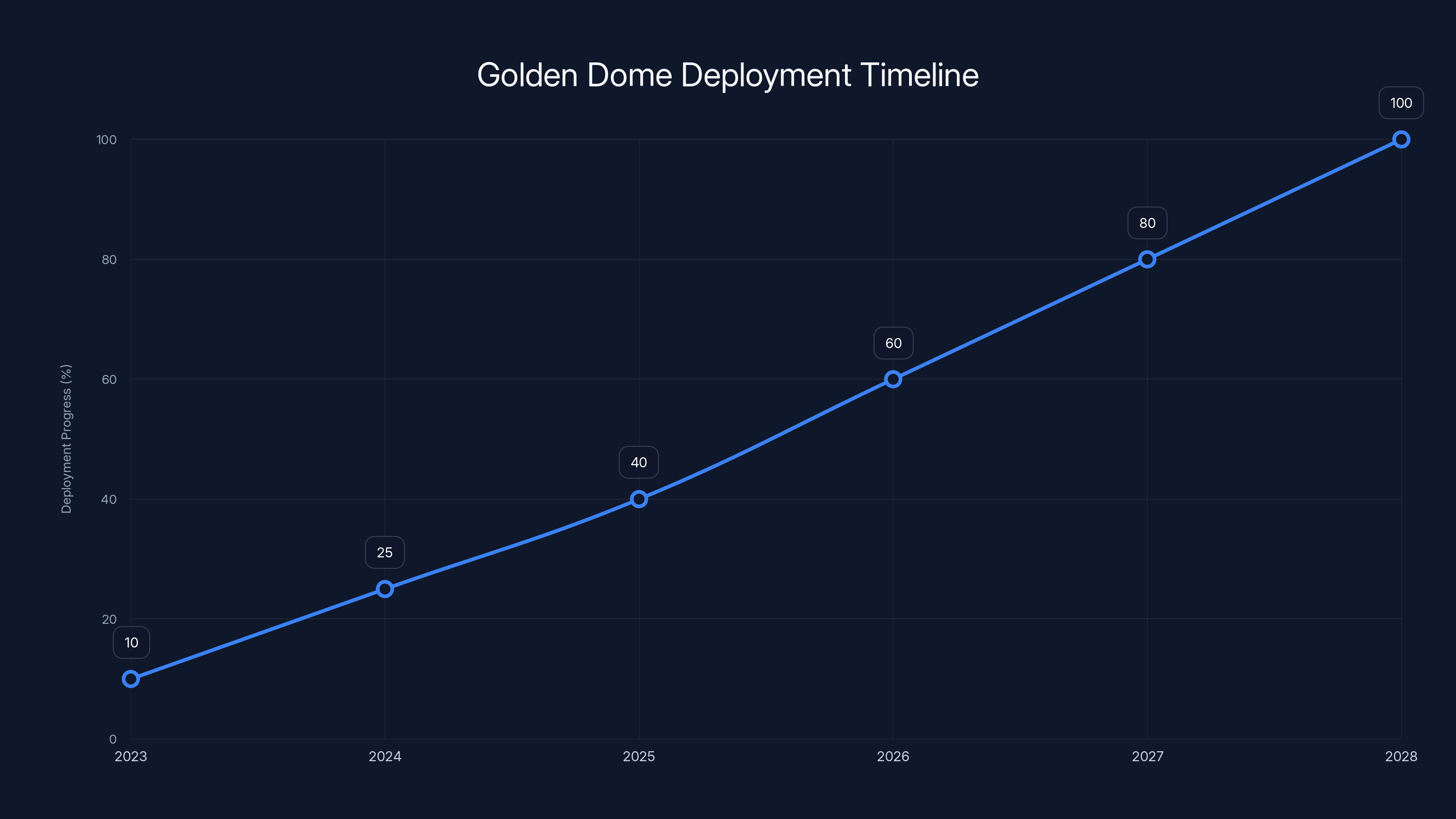

General Michael Guetlein stood before industry representatives with an ambitious vision. By summer 2028, he promised, the United States would deploy a revolutionary space-based missile defense system capable of protecting the entire nation against ballistic missiles, hypersonic weapons, and emerging aerial threats. The Golden Dome program represents perhaps the most aggressive military technology push in a generation, with a three-year timeline that leaves virtually no room for setbacks.

But there's a problem that has nothing to do with physics or engineering.

"International partners, I have not been allowed to talk to yet because of the trade wars," Guetlein acknowledged during a recent industry presentation. The comment captures something far larger than one military program: the collision between Trump administration policies that are pulling in opposite directions. On one hand, the White House is trying to build an advanced defensive shield. On the other, aggressive tariffs and trade threats are making it nearly impossible to coordinate with the very allies whose geography and capabilities are essential to the system's success.

This isn't a small coordination problem. It's a fundamental tension that could determine whether Golden Dome becomes a transformative defense capability or an expensive, partially functional system that leaves critical gaps in coverage.

The Scale of the Golden Dome Vision

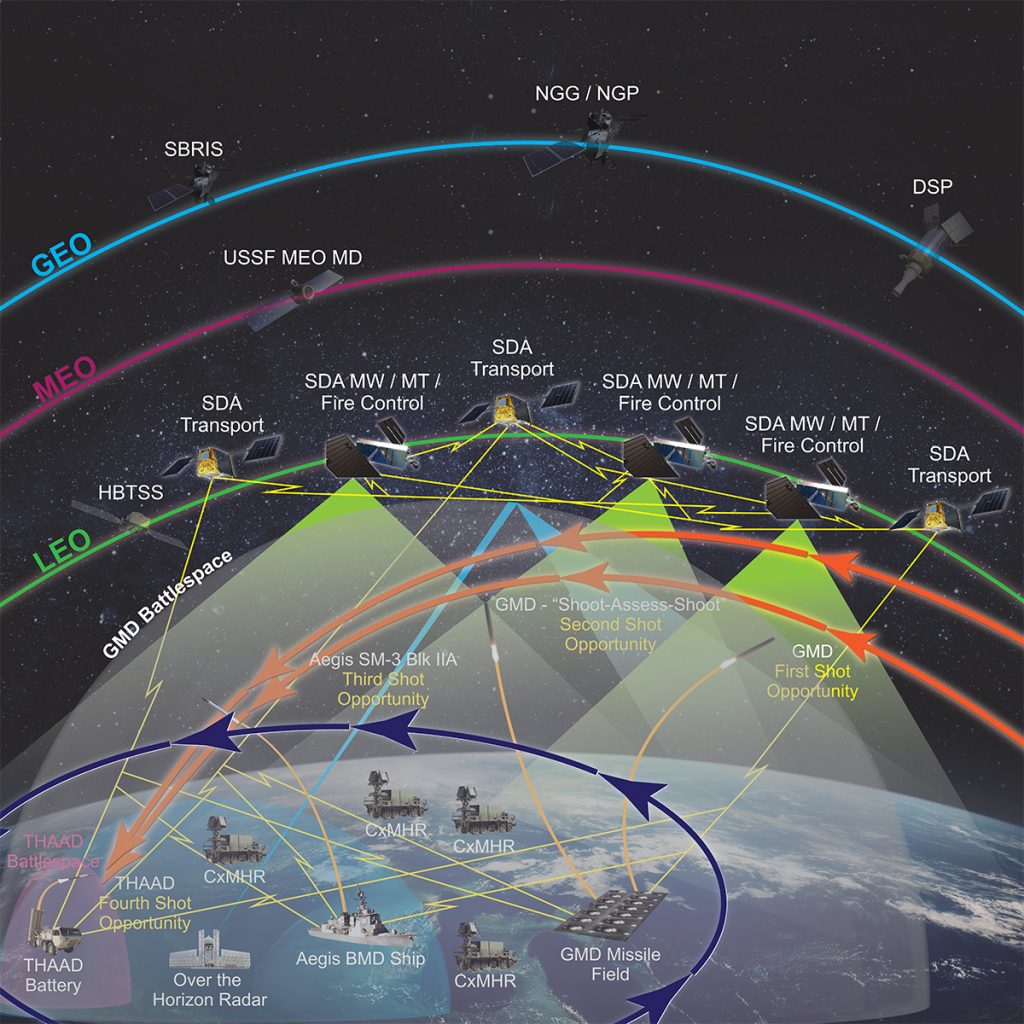

Golden Dome isn't a single weapon or technology. It's an integrated architecture combining space-based sensors, satellite-mounted interceptors, advanced tracking systems, and ground-based missile defense assets. The program pulls together decades of military research, billions in existing investments in reusable rockets and satellite manufacturing, and new prototype development contracts with major defense contractors.

The ambition is staggering in scope. Current U.S. missile defense relies heavily on ground-based interceptors positioned in Alaska and California. These systems can defend against ballistic missiles, but they have significant limitations. They require time to launch, can only cover certain geographic corridors, and struggle against newer threats like hypersonic weapons that maneuver unpredictably through the atmosphere.

Golden Dome would change this entirely. Space-based sensors could detect enemy missiles within seconds of launch. Orbiting interceptors could engage threats over enemy territory, eliminating the need for the enemy to get halfway across the Pacific. The system would provide layered defense, with multiple opportunities to knock down incoming weapons before they threaten American cities.

Guetlein has been characteristically blunt about the timeline. There's no contingency for budget cuts, no flexibility for technical delays, no margin for error. If something goes wrong in prototype development, if launch schedules slip, if Congress balks at the funding, the entire three-year schedule collapses. This isn't a program built for real-world complexity. It's built for perfection.

That's possible only with exceptional cooperation. And that cooperation is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain.

Projected deployment progress of the Golden Dome system from 2023 to 2028, aiming for full deployment by summer 2028. Estimated data based on typical defense project timelines.

Why Allies Matter: Geography as Strategic Asset

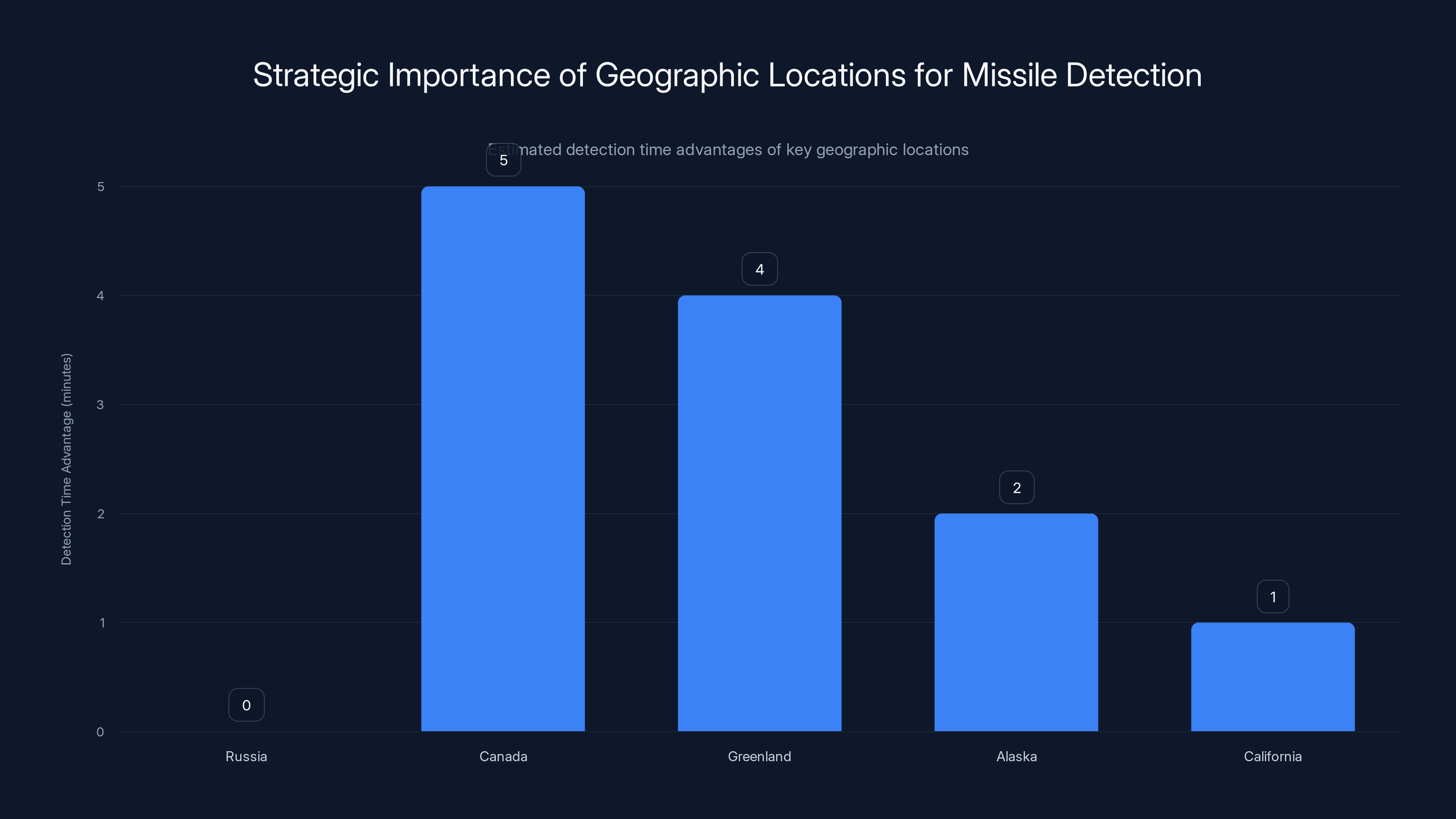

The physics of missile detection explain why allies matter so much. Intercontinental ballistic missiles follow predictable trajectories, but they fly fast. An ICBM launched from Russia travels at roughly 15,000 miles per hour. From launch to impact takes roughly 30 minutes. That sounds like a lot of time, but it vanishes quickly when you account for sensor processing, tracking confirmation, and engagement calculations.

Every mile of early warning matters. Every second counts.

Canada's geography positions it directly in the launch corridor from Russia. The Canadian Arctic can detect Russian missiles earlier than any ground-based U.S. system. Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, offers similar advantages. Both regions sit at high latitudes where ballistic missile trajectories are predictable and visible from space-based sensors.

Beyond detection, these allies offer something else valuable: territory. Golden Dome needs more than space-based sensors and interceptors. It needs ground stations to process data, relay information, and potentially host new ground-based interceptors. Alaska and California, the current homes of U.S. missile defenses, sit at the southern edge of the detection problem. Spreading the architecture northward into Canadian territory or Greenland would create a more robust, redundant system.

Canada is part of NORAD, the North American Aerospace Defense Command, which already coordinates continental air defense. The two nations have been sharing radar data and military intelligence for seventy years. The institutional relationships exist. The technical expertise exists. The only thing missing is the political will to make it work.

Denmark presents a similar picture. Though Denmark doesn't participate in NORAD, it has long-standing security partnerships with the United States. Greenland, despite its small population, hosts Pituffik Space Base, formerly known as Thule Air Base. The U.S. military has maintained a presence there since the Cold War. The infrastructure is in place. The relationships are established.

With both allies fully integrated into Golden Dome, the system would gain redundancy, coverage, and defensive depth. Without them, the program becomes a partial solution that leaves America's northern approaches vulnerable.

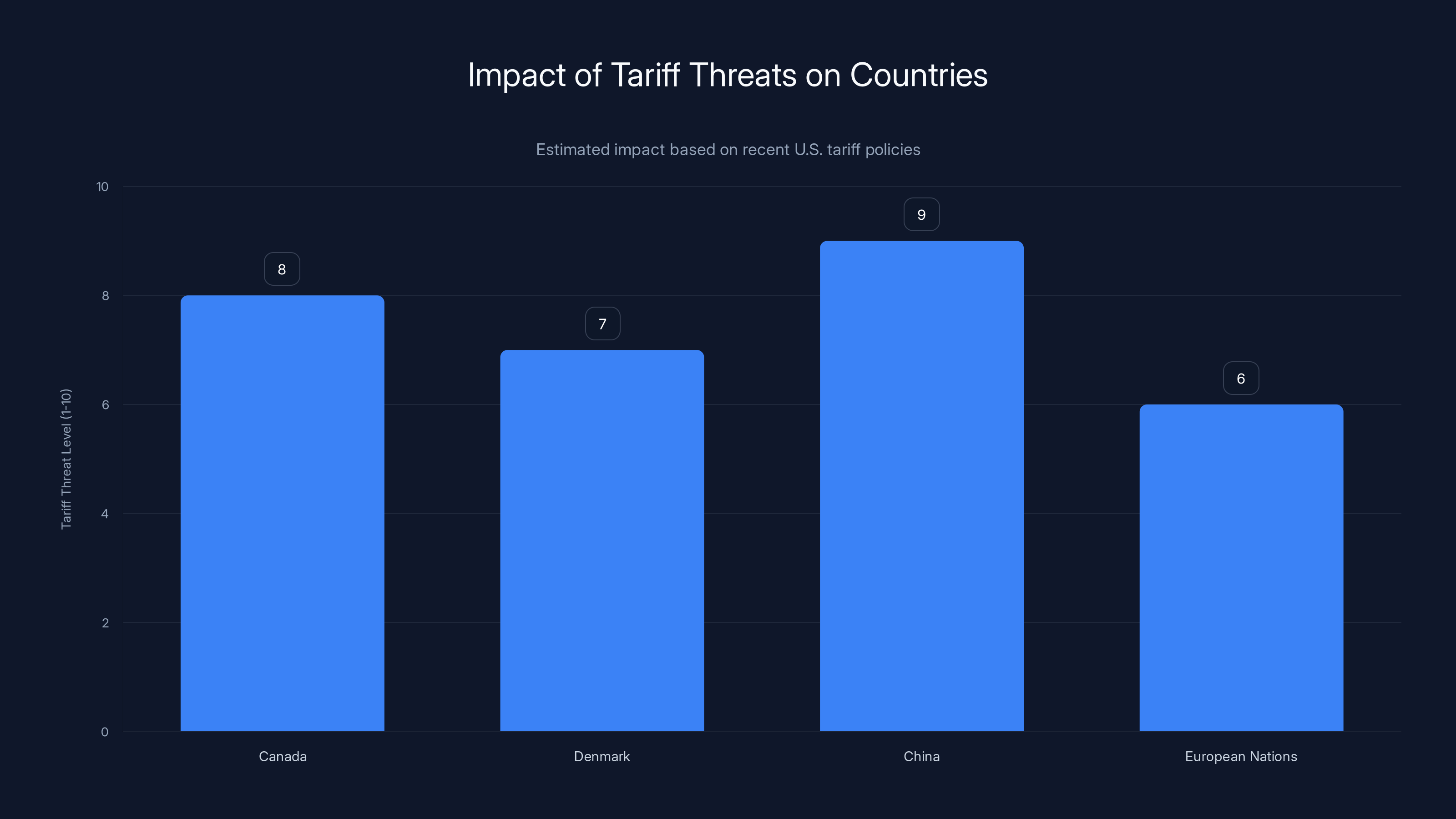

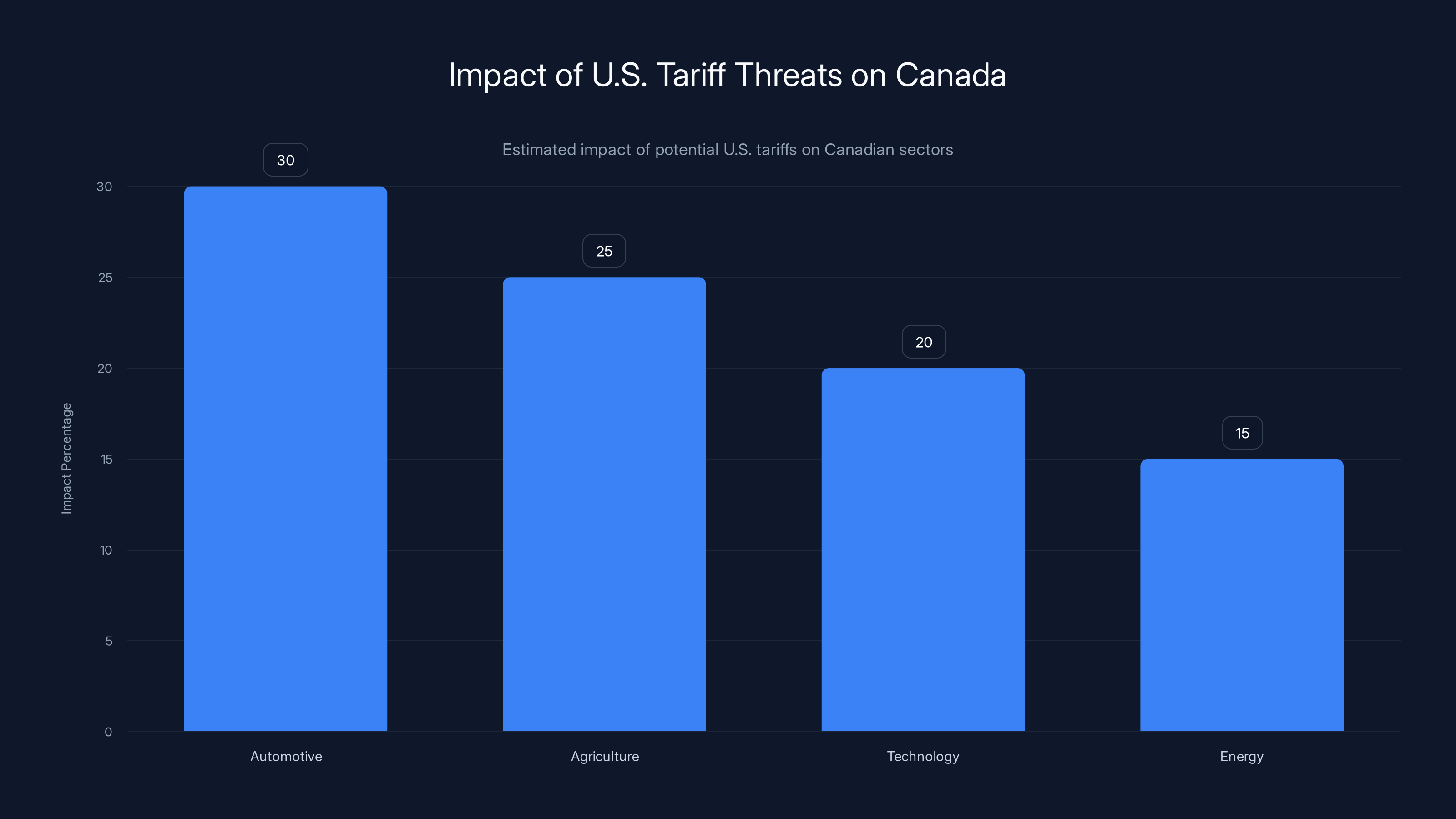

Estimated data suggests China faces the highest tariff threat level, followed by Canada and Denmark, due to U.S. aggressive tariff policies.

The Trade War Obstacle

This is where the Trump administration's other priorities create a direct conflict with Golden Dome's success.

Trump has made clear his commitment to aggressive tariff policy. Tariffs on Canadian goods, threats of tariffs on China, trade retaliation against European nations, and demands for specific geopolitical concessions wrapped in trade language. The White House views tariffs as leverage, a tool to force countries toward American objectives on everything from trade deficits to military spending to territorial disputes.

Canada and Denmark have both been targeted for increased tariffs. Canada faces tariff threats over trade disputes and Trump's insistence that the country should join the United States or accept tariff consequences. Denmark is in a more complex position because of Trump's recent obsession with acquiring Greenland.

Yes, acquiring. As in, purchasing it from Denmark.

This isn't subtle diplomatic maneuvering. Trump has repeatedly stated publicly that the United States should acquire Greenland. He's framed it as essential to Arctic security. The White House threatened significant tariffs on Denmark and other European nations unless Denmark would negotiate selling Greenland to the United States. The President even joked about not ruling out military force to acquire the territory.

Think about the optics from Denmark's perspective. Your major ally is threatening tariffs unless you sell a piece of your country. You have a military base on Greenland that the U.S. already uses for missile defense. The situation is almost comically contradictory. Denmark can't discuss serious defense integration with the United States while the same administration is threatening economic punishment.

Denmark's Complicated Position

Denmark has attempted to navigate these contradictions with diplomatic skill. After Trump's initial threats, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen signaled openness to discussing Arctic security and missile defense cooperation. But she also made clear that any discussions would need to happen with respect for Denmark's territorial integrity. Translation: No, we're not selling Greenland.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Trump appeared to back down from his most aggressive acquisition rhetoric. He announced an undefined "framework" for future NATO cooperation on Arctic security, including missile defense integration. He told media that Denmark would be involved in Golden Dome and that mineral rights in Greenland would be part of the arrangement.

This was progress. Sort of. But it was also vague enough to satisfy no one.

Denmark's position is genuinely difficult. The nation sits between legitimate security concerns about Russia, its own commitment to NATO, and an American ally behaving in ways that traditional allies don't typically behave. Trump's rhetoric about acquiring Greenland isn't standard diplomatic language. It's confrontational, making it politically difficult for Danish leaders to cooperate enthusiastically on defense matters.

Moreover, there's asymmetry in what each side needs. Denmark's primary interest is NATO security and Arctic stability. The United States desperately needs access to Greenland for missile defense. The tariff threats didn't create negotiating leverage. They created resentment and mistrust. You can't build a thirty-year defensive architecture on a foundation of coerced cooperation.

The Davos framework may have been a face-saving gesture, but it didn't actually resolve the underlying tension. Denmark still won't sell Greenland. The United States still wants forward bases there. And military cooperation happens in that shadow.

Canada and Greenland offer significant detection time advantages due to their geographic positions, enhancing missile detection capabilities. Estimated data.

Canada's Deteriorating Position

Canada faces even more direct hostility from the Trump administration. Unlike Denmark, Canada has no leverage, no territory Trump wants to purchase, and no ability to offer mineral rights or strategic trade-offs. Canada is simply in Trump's tariff crosshairs.

Trump has threatened a 100 percent tariff on Canadian goods. He's mocked Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney (or Justin Trudeau, depending on the timeline of events). He's suggested on social media that Canada should be a U.S. state. The tone is hostile in ways that go beyond typical trade disputes. This is personal.

When Carney criticized Trump's foreign policy during a speech at Davos, Trump responded with threats. When the possibility emerged that Canada might pursue trade deals with China, Trump threatened 100 percent tariffs again. Every Canadian diplomatic move seems to invite a tariff response.

In this environment, how does a Canadian military official sit down with General Guetlein and discuss Golden Dome integration? How does Canada commit resources to a U.S. military program when the same administration is threatening devastating economic punishment? How does a government explain to its citizens why they're helping the country that's trying to economically coerce them?

Guetlein noted on social media that Canada was somehow "against" Golden Dome plans. Canada's ambassador to the United States pushed back, saying she had no idea what he was talking about. This is what happens when communication channels are frozen by trade war dynamics. Misunderstandings compound. Suspicion grows. Allied cooperation becomes impossible.

The Technical Consequences

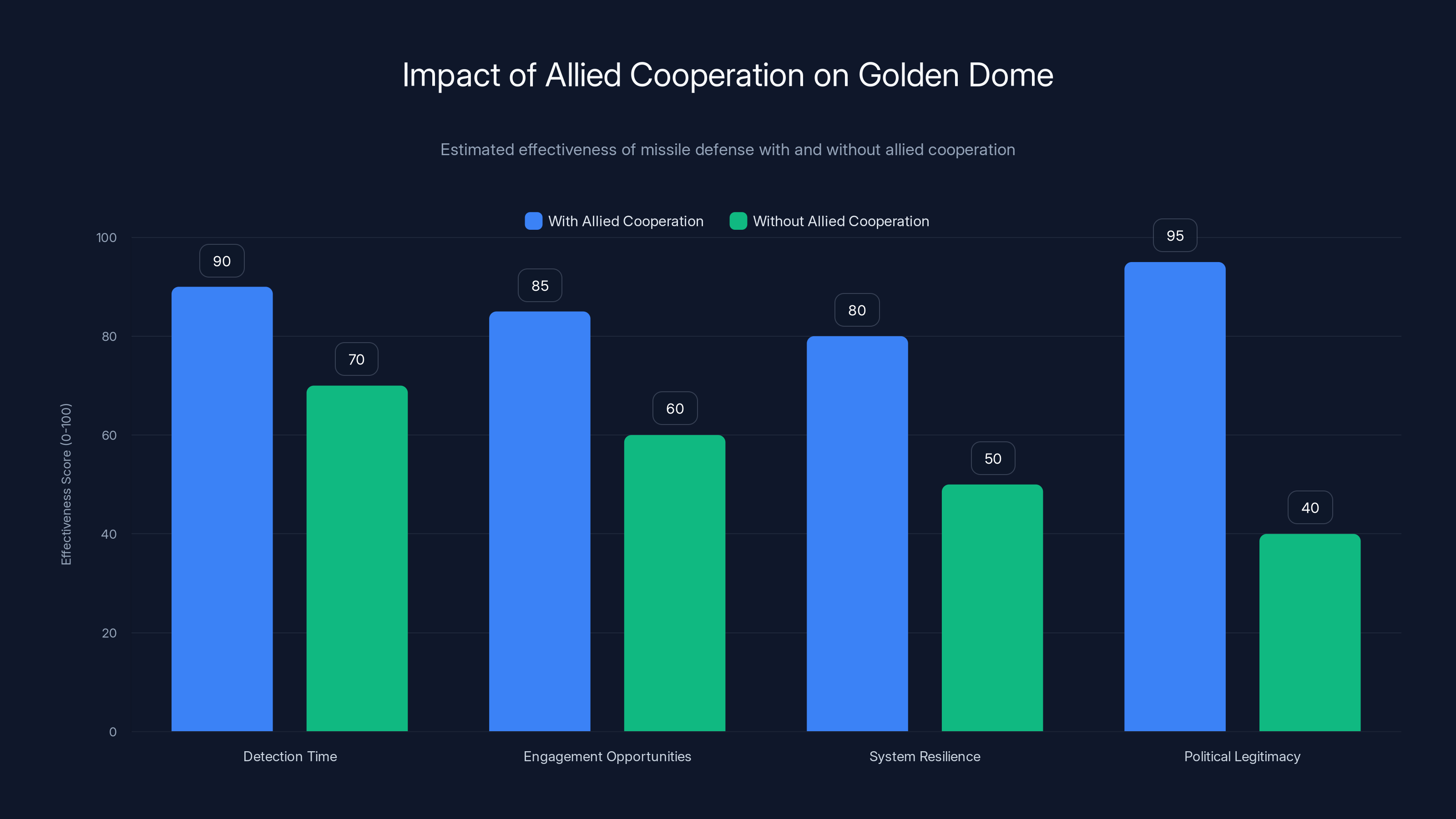

What does Golden Dome look like without allied cooperation? It looks incomplete.

The system would still function. Space-based sensors positioned over the Pacific could detect missiles launched from Russia toward Alaska. Ground-based interceptors in Alaska and California could engage some threats. The basic layered defense concept would still work for threats coming from the Pacific.

But the Arctic advantage vanishes. Sensors positioned over the Arctic could detect missiles traveling the North Pole corridor significantly earlier than Pacific-based sensors. That early warning time translates directly into more engagement opportunities. Without it, gaps open. Not complete coverage failures, but coverage degradation that matters in a real conflict.

Ground-based interceptors positioned in Canada would provide redundancy and geographic diversity. Without them, the system becomes more dependent on space-based assets. Space-based systems are inherently fragile in ways that distributed, ground-based systems are not. A single attack could degrade or destroy critical space-based infrastructure. Redundancy through allied territory provides resilience.

Moreover, the political reality of having foreign allies participate in Golden Dome would provide legitimacy. Other nations would be more willing to support the program if their strategic partners were involved. The system would look less like American unilateral action and more like collective defense. Without allied integration, Golden Dome appears to some observers as exactly what critics fear: an American attempt to impose a unilateral defensive system that alters strategic balances and encourages other powers to develop countermeasures.

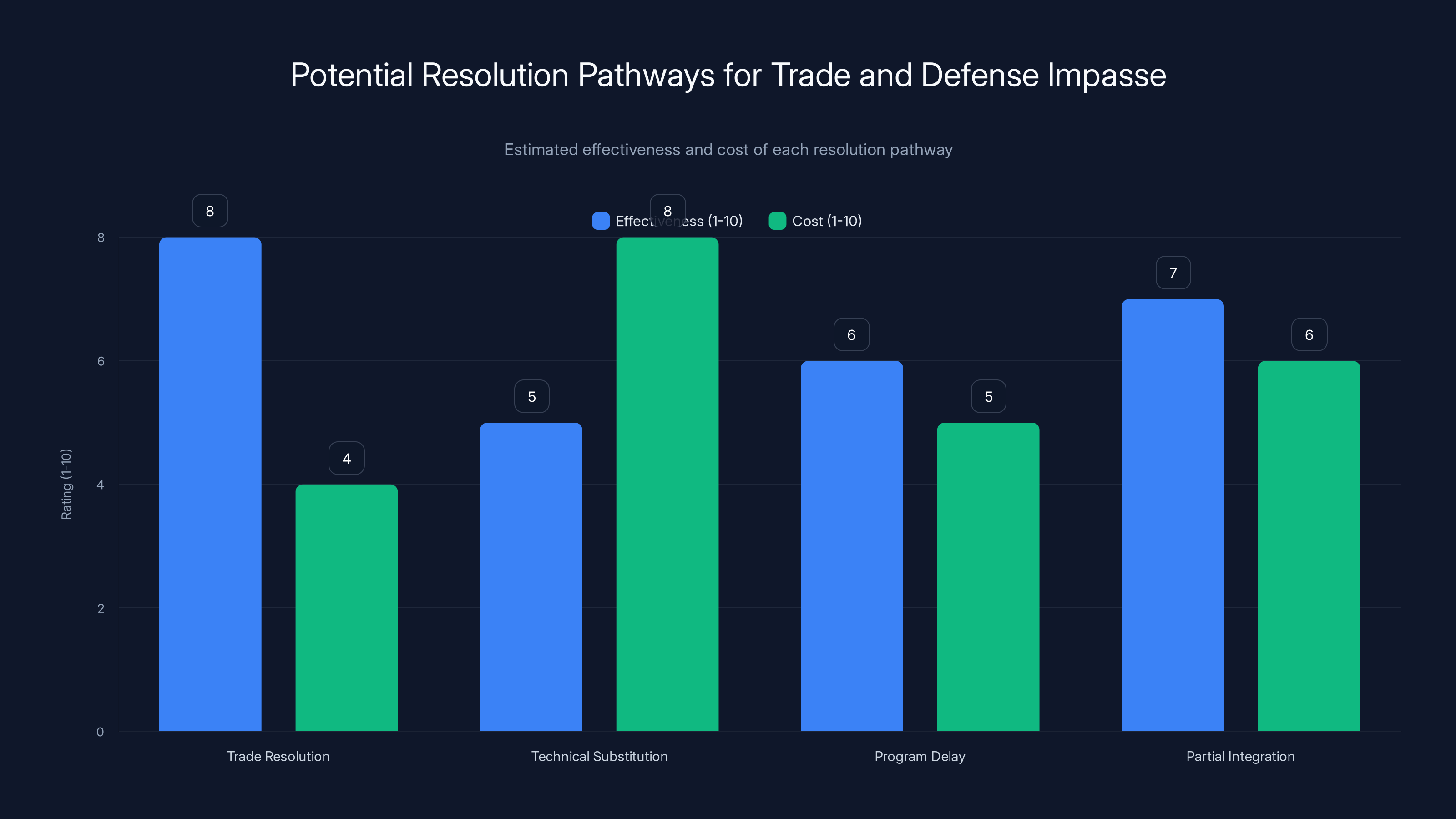

Trade resolution is estimated to be the most effective pathway, while technical substitution is the most costly. Estimated data.

Historical Precedent: Star Wars and Its Lessons

General Guetlein and his team are acutely aware of history. Ronald Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative, nicknamed "Star Wars," faced an entirely different set of obstacles but offers crucial lessons about ambitious missile defense programs.

START was conceived in the 1980s as a comprehensive defense against Soviet ICBMs. The vision was revolutionary. The reality was humbling. Technologies didn't work as expected. Costs ballooned. The Soviet Union collapsed before the program could be fully realized. What emerged after the Cold War was a drastically downsized system focused on limited threats rather than comprehensive defense.

The difference between Star Wars and Golden Dome is significant. Star Wars was largely theoretical. It relied on technologies that didn't yet exist at the required scale. Golden Dome, by contrast, builds on existing infrastructure. Reusable rockets like Space X's Falcon 9 have transformed launch costs. Satellite manufacturing has become industrialized. Tracking and sensor technology is proven. The foundational technologies are real.

But there's a lesson Star Wars teaches that applies today: political obstacles can be as fatal as technical ones. Star Wars lost momentum because political support shifted. If Golden Dome faces similar political erosion, the three-year timeline becomes impossible regardless of technical capability.

Trade wars with allies are precisely the kind of political obstacle that undermines support for ambitious defense programs. Allies become reluctant partners. Public support wavers when the same administration is engaged in hostile trade disputes with friendly nations. Media coverage becomes skeptical. Congressional support becomes conditional.

The Hypersonic Threat Context

One reason Golden Dome has gained support despite its costs is the genuine emergence of hypersonic threats. Russia and China have both developed and tested hypersonic weapons that travel at speeds exceeding five times the speed of sound. These weapons are far more difficult to detect and intercept than traditional ballistic missiles.

Hypersonic weapons follow unpredictable flight paths. They maneuver during their approach phase. Existing missile defenses struggle against them because intercept calculations must account for potential course changes. A system designed to hit an ICBM following a predictable ballistic arc isn't optimized for a weapon that can turn mid-flight.

Golden Dome's space-based architecture is specifically designed to address this threat. Early detection from space gives the system the sensor data needed to track hypersonic weapons throughout their flight. Multiple engagement opportunities from space-based interceptors mean that even if one attempt fails, others remain available.

This threat is real and serious enough that even skeptics of the program acknowledge the need for new defensive approaches. The question isn't whether American defenses need modernization. The question is whether Golden Dome's specific approach is viable given current political conditions.

The trade war obstacle makes an already ambitious timeline more precarious. Hypersonic threats aren't waiting for political compromise. They're advancing regardless of American bureaucratic challenges. This creates pressure on policymakers to find solutions to the allied cooperation problem, but trade war dynamics make solutions difficult.

Estimated data shows potential impact of U.S. tariffs on key Canadian sectors, with automotive and agriculture facing the highest risks.

NATO's Competing Concerns

NATO member nations, particularly Canada and Denmark, face their own strategic dilemma. They benefit from American commitment to continental defense. The security guarantee implicit in NATO membership depends on American willingness to project power and maintain military capabilities.

But NATO is also built on principles of collective decision-making and mutual respect among sovereign members. When one member, even if it's the most powerful one, threatens economic coercion against other members, NATO's institutional logic becomes strained.

Canada and Denmark have obligations to NATO. They have signed defense cooperation agreements. But they also have legitimate interests in maintaining economic relationships and avoiding punitive tariffs. These interests aren't secondary. They affect the wellbeing of their citizens.

The deeper issue is that Golden Dome requires the kind of deep integration that only happens when trust exists. You don't invite a country to host forward defense systems on your territory, allow them access to your airspace, and integrate your military command structures when that country is simultaneously imposing tariffs and making territorial demands. The political prerequisites for technical cooperation simply don't exist.

The Mineral Rights Angle

Trump's mention of mineral rights in connection with the Davos framework deserves examination. Greenland contains significant mineral resources, particularly rare earth elements essential for advanced electronics and military systems. China currently dominates global rare earth production. Diversifying supply chains is a legitimate strategic goal.

But using Arctic defense integration as leverage for mineral access creates its own problems. It converts a security arrangement into a resource extraction negotiation. Other nations see this and become more reluctant to participate in similar arrangements. It raises questions about whether military basing is truly about mutual defense or about securing resources.

Minerals are important for American strategic independence. But they're not more important than the functioning of allied relationships. By bundling mineral rights with defense integration, the administration creates the impression that military cooperation is transactional rather than principled.

Denmark's response at Davos, signaling openness while maintaining territorial integrity, was an attempt to separate these issues. Defense cooperation can happen without mineral concessions. But the Trump administration's framing makes such separation difficult.

Allied cooperation significantly enhances the Golden Dome system's detection time, engagement opportunities, resilience, and political legitimacy. Estimated data.

The Technical Workarounds

General Guetlein and his team aren't idle while trade disputes continue. They're developing technical alternatives to allied participation, but these alternatives are second-best solutions.

Space-based radar can be augmented to improve detection over Arctic regions without ground stations in Canada. Additional satellites can provide redundancy where Canada and Greenland couldn't. More frequent orbital coverage can compensate for reduced ground-based networking.

But these approaches cost more money and create additional complexity. The three-year timeline becomes more challenging. The technical margin for error shrinks further. What was already aggressive becomes nearly impossible.

Moreover, these technical workarounds don't address the political legitimacy problem. A Golden Dome system developed entirely without allied participation looks different to other nations than one developed with NATO integration. It appears more unilateral, more threatening, more likely to trigger countermeasures from other powers.

Russia and China are watching this situation carefully. They're noting that the United States is having difficulty coordinating with allies due to trade disputes. They're calculating whether Golden Dome will be a comprehensive system or a partial one. They're developing countermeasures regardless, but a partial system requires fewer countermeasures to overcome.

Congressional Pressure Points

Congress holds the purse strings for Golden Dome, and members are watching both the program's technical progress and the allied cooperation challenge.

Defense hawks in Congress generally support Golden Dome as essential to American security. They're concerned about Russian and Chinese capabilities. They believe space-based defense is the future. But many of these same members also care about maintaining allied relationships. Trade disputes that strain NATO partnerships create cognitive dissonance.

Defense doves in Congress are skeptical of Golden Dome for different reasons. They worry about costs, about triggering arms races, about whether space-based weapons violate the spirit of arms control treaties. They see the allied cooperation problem as evidence that the program is overly ambitious.

Both groups will watch how the trade war situation develops. If tariffs with Canada are lifted and cooperation frameworks with Denmark are solidified, skeptics might be quieted. If trade tensions escalate and allied cooperation fails, support becomes harder to maintain.

This creates incentive for the Trump administration to resolve trade disputes with key allies. But the administration has shown limited interest in such resolution. Tariffs appear to be a fundamental policy priority, not a temporary negotiating tactic.

If that continues, Congress will eventually need to choose between funding a program that lacks allied participation or redirecting resources to other defense priorities. That choice hasn't arrived yet, but it will if Golden Dome's allied partnership prospects continue to deteriorate.

The Broader Strategic Picture

Golden Dome doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a broader American strategy to maintain military superiority in competition with Russia and China. That competition is multifaceted, involving space capabilities, hypersonic weapons, cyber warfare, and conventional forces.

America's advantage in this competition has always rested partly on superior technology and partly on superior alliances. The United States has been able to develop military capabilities that no peer competitor can match because it has access to allied territory, shared intelligence, cooperative development, and allied manufacturing.

If trade wars damage allied relationships, this fundamental advantage erodes. The United States can still develop advanced systems. But it develops them more slowly, with higher costs, without the redundancy and resilience that allied integration provides.

Golden Dome is a test case. If the program succeeds despite trade war pressures, it might signal that the United States can maintain military superiority without allied cooperation. If it fails, or if it emerges as a degraded version of its original conception, it signals that trade war costs extend beyond economics into military capability.

Adversaries are watching this calculation carefully. If they conclude that American trade wars are weakening allied relationships in ways that degrade American military capabilities, they might become more assertive. They might accelerate their own capability development, knowing that American defenses are less robust than they might otherwise be.

This is the strategic risk that Guetlein's comment about trade wars muzzling allied talks really highlights. It's not just about one program. It's about whether the United States can pursue multiple competing policies simultaneously without them undermining each other.

Timeline Pressures

The three-year deadline for Golden Dome's initial deployment creates constant pressure. Every month of delayed communication with allies is a month lost from planning and coordination. Every trade dispute that cools allied enthusiasm is momentum sacrificed.

The Pentagon has experience with ambitious timelines. When priorities are clear and resources are available, remarkable things can be accomplished. But timelines depend on perfect execution and absence of external obstacles.

Trade wars are external obstacles. They're not inevitable. They're policy choices. If the Trump administration decided to prioritize allied cooperation for defense purposes, tariff threats against Canada and Denmark could be suspended. Negotiations on trade disputes could be shelved temporarily while defense integration moved forward. The military priority could be isolated from trade disputes.

That hasn't happened. Instead, both priorities are being pursued simultaneously, with each one undermining the other. General Guetlein is trying to negotiate with allies while those same allies are absorbing tariff threats. It's not a recipe for success.

The question facing the administration is whether it wants Golden Dome to succeed more than it wants to use tariffs as leverage on Canada and Denmark. Right now, the actions suggest tariffs are the higher priority. If that changes, the situation could shift rapidly. But there's no indication of change forthcoming.

Potential Resolution Pathways

Several scenarios could resolve the impasse, though each involves trade-offs.

The first path is resolution of trade disputes. If the Trump administration reaches agreements with Canada on trade issues, or if it backs away from tariff threats in exchange for other concessions, allied cooperation could resume. This has already partially happened with Denmark through the Davos framework. A similar resolution with Canada could unblock military cooperation. This path requires the administration to view defense priorities as more important than trade leverage.

The second path is technical substitution. Golden Dome could proceed without allied participation, relying on additional satellites, enhanced ground-based systems in U.S. territory, and agreements that fall short of integrated defense architectures. This path is more expensive and less effective, but it's possible. It requires acknowledging that allied cooperation has been foreclosed and planning accordingly.

The third path is program delay. The three-year timeline could be extended, giving more time for diplomatic relationships to improve and for allied cooperation to resume. This path involves acknowledging that the original timeline was overly ambitious and adjusting expectations. It's politically difficult because it means delaying deployment of a capability that the administration has promised.

The fourth path is partial integration. Some allies might participate while others don't. Denmark might commit to hosting equipment in Greenland while Canada remains reluctant. This creates a fragmented system that's less effective than full integration but better than complete isolation. It requires separating integration agreements from broader trade disputes.

None of these paths is ideal. Each involves costs and compromises. But absent significant changes in how the Trump administration conducts trade policy, one of these outcomes is inevitable.

Lessons for Future Defense Programs

Golden Dome is teaching lessons that will apply to military technology programs for years to come. The fundamental lesson is that technical capability and political feasibility are distinct problems that can come into conflict.

A system can be technically achievable but politically unattainable if the political prerequisites for its development are undermined. In this case, the political prerequisite was allied cooperation. The political context undermining it was trade wars.

Future programs will need to either isolate themselves from broader policy disputes or ensure that competing policies don't undermine critical partnerships. This requires coordination at the highest levels of government, ensuring that trade policy, diplomatic policy, and defense policy are aligned rather than contradictory.

It also suggests that ambitious timelines should build in contingencies for political obstacles, not just technical ones. If a program assumes allied cooperation and that cooperation becomes unlikely, the timeline needs to adjust. Planning as if everything will go perfectly is planning for failure.

For other nations watching this unfold, the lesson is that alliance relationships with the United States depend not just on enduring security interests but on how the U.S. conducts its economic policies. If the U.S. weaponizes trade against allies while simultaneously requesting their cooperation on military matters, alliance relationships become more transactional and less trusted.

The Intersection of Economics and Security

The fundamental tension underlying the Golden Dome situation is that economics and security have become increasingly intertwined in modern policy.

Historically, trade and security were managed separately. Countries could compete economically while cooperating militarily. That separation has eroded. Technology supply chains are security issues. Rare earth minerals are security issues. Trade relationships affect military capability. When one administration prioritizes tariffs while another agency prioritizes defense cooperation with the same allies, something has to give.

The Trump administration appears to believe that tariff leverage can achieve security objectives that diplomacy alone cannot. Get Canada to accept U.S. terms on trade. Get Denmark to make Greenland available or accept U.S. mining rights. Use economic pressure to achieve strategic goals.

But this approach assumes that economic coercion and military cooperation can be compartmentalized. In reality, they can't. A country subjected to tariff threats becomes a reluctant ally. It provides cooperation because it must, not because it's genuinely committed. That's a weak foundation for the integrated defense architecture that Golden Dome requires.

The alternative approach is to keep economics and security in separate negotiating lanes. Address trade disputes through trade channels. Address security needs through security partnerships. Avoid bundling them together. This approach requires discipline and separation of concerns, but it's more likely to produce stable cooperation.

Right now, the Trump administration is not pursuing this separation. Tariffs and defense cooperation are bundled together. That's the fundamental problem creating the allied participation crisis.

Looking Forward

Golden Dome will proceed in some form. The United States has too much invested in space-based missile defense capabilities, the threats are real enough, and the political commitment is strong enough that the program will continue.

But the form it takes will be shaped by how the trade war issue resolves. If allied cooperation is restored, the program becomes the comprehensive system its architects envision. If it remains blocked, the program becomes a partial, less effective system that costs more money and provides fewer benefits.

General Guetlein's comment about being muzzled by trade wars is likely to echo through discussions of this program for years. It's a stark acknowledgment that military capability doesn't exist in a vacuum. It depends on political relationships, economic cooperation, and the ability to work with allies.

The next twelve months will be crucial. Will the Trump administration resolve trade disputes with Canada? Will the Davos framework with Denmark translate into concrete military integration agreements? Or will trade tensions continue to rise, further damaging the allied cooperation that Golden Dome depends on?

Those questions will determine whether Golden Dome achieves its ambitious vision or emerges as an expensive, partial solution to the hypersonic and ballistic missile threat.

FAQ

What is Golden Dome?

Golden Dome is the Trump administration's space-based missile defense architecture designed to protect the entire United States against ballistic missiles, hypersonic weapons, and other aerial threats. The system combines space-based sensors, satellite-mounted interceptors, advanced tracking systems, and ground-based assets into an integrated defense network with a planned deployment by summer 2028.

Why is allied cooperation important for Golden Dome?

Canada and Greenland (through Denmark) occupy strategic geographic positions that enable early detection of missiles launched from Russia across the Arctic. These locations also could host ground stations and next-generation interceptors. Without allied participation, Golden Dome becomes a partial system with coverage gaps and reduced effectiveness against threats from the northern approach vectors.

How do trade wars affect Golden Dome development?

The Trump administration has threatened significant tariffs against both Canada and Denmark while simultaneously seeking their cooperation on Golden Dome. These conflicting signals make allies reluctant to commit resources and political capital to the program, effectively blocking the detailed communications and coordination necessary for integration. General Guetlein stated he hasn't been able to discuss the program with international partners because of ongoing trade disputes.

What are the technical consequences of losing allied cooperation?

Without Canadian and Danish participation, the Pentagon must develop technical workarounds including additional satellites for Arctic coverage, more redundant systems, and enhanced processing capability to compensate for lost ground-based infrastructure. These alternatives increase costs, reduce system effectiveness, and make the aggressive three-year deployment timeline more difficult to achieve.

What is the timeline for Golden Dome deployment?

General Guetlein has committed to initial defensive capability against ballistic missiles and hypersonic threats by summer 2028, with continued architecture expansion through 2035. This three-year timeline for initial deployment leaves virtually no margin for error from technical setbacks, budget constraints, or political obstacles like trade war-related delays in allied cooperation.

Could Golden Dome succeed without allied cooperation?

Yes, but with significant degradation. The system could function with only U.S.-based assets and satellites, providing coverage against threats from certain approach vectors. However, Arctic coverage would be weaker, redundancy would be reduced, and the system would be more vulnerable to attacks on critical space-based infrastructure. International legitimacy and NATO integration benefits would also be lost.

What lessons does Star Wars offer for Golden Dome?

Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative ultimately failed partly due to political obstacles and shifting support, despite technical progress. Golden Dome has advantage of building on proven technologies, but faces similar political risks. Trade wars that damage allied relationships are the modern equivalent of the political erosion that undermined Star Wars, suggesting that political obstacles can be as fatal as technical challenges.

Why does Greenland matter for missile defense?

Greenland sits at high latitudes where ballistic missile trajectories from Russia are predictable and visible to space-based sensors. Early detection from Greenland provides crucial warning time before missiles reach North American targets. The island also hosts Pituffik Space Base, which already supports U.S. military operations, providing existing infrastructure for defense integration.

Will trade disputes prevent Golden Dome integration with allies?

Currently yes, though this could change. General Guetlein stated he cannot discuss the program with allies because of trade wars. The situation remains fluid, as demonstrated by the Davos framework with Denmark. If the Trump administration resolves trade disputes with Canada and solidifies cooperation with Denmark, communication channels could reopen. However, prolonged trade tensions will likely result in Golden Dome proceeding without full allied integration.

TL; DR

- Golden Dome Challenge: The Pentagon's ambitious three-year space-based missile defense system faces allied cooperation obstacles due to concurrent Trump administration tariff policies against key defense partners Canada and Denmark

- Geographic Reality: Canadian Arctic and Greenland locations are strategically essential for early detection of Russian and Chinese missiles, but trade tensions are muzzling necessary discussions with these allies

- Timeline Pressure: The summer 2028 deployment deadline leaves virtually no room for political delays, making trade war-caused communication blackouts increasingly dangerous to program success

- Technical Workarounds: The Pentagon can develop substitute capabilities through additional satellites and enhanced ground-based systems, but these are more expensive, less effective, and undermine the three-year timeline

- Strategic Irony: The administration is simultaneously pursuing defense integration with allies while economically coercing those same allies, creating conflicting signals that undermine cooperation on both fronts

- Bottom Line: Golden Dome will likely succeed as a partial system rather than the comprehensive integrated architecture originally planned, with consequences for American security posture against emerging hypersonic and ballistic missile threats

Key Takeaways

- Golden Dome is a three-year aggressive timeline to deploy space-based missile defense by summer 2028, but allied cooperation is essential to its success

- Trade war tariffs against Canada and Denmark are directly blocking General Guetlein from discussing the program with strategic partners whose Arctic geography is critical

- Without allied participation in Greenland and Canada, Golden Dome becomes a partial system with coverage gaps, higher costs, and reduced effectiveness against hypersonic threats

- The Trump administration is pursuing conflicting policies: tariff leverage against allies while simultaneously requesting their defense cooperation, creating mutual distrust

- Technical workarounds through additional satellites and enhanced ground systems are possible but more expensive and undermine the aggressive three-year deployment timeline

Related Articles

- Why Minnesota Can't Stop ICE: The Federal Authority Problem [2025]

- TikTok's Trump Deal: What ByteDance Control Means for Users [2025]

- TikTok's US Entity Deal Explained: How ByteDance Avoided Ban [2025]

- DOGE Social Security Data Misuse: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]

- The Fake War on Protein: Politics, Masculinity & Nutrition [2025]

- Tech Workers Condemn ICE While CEOs Stay Silent [2025]

![Golden Dome Missile Shield: How Trade Wars Block Allied Defense Plans [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/golden-dome-missile-shield-how-trade-wars-block-allied-defen/image-1-1769530147473.jpg)