Understanding the Grok Deepfake Crisis and Its Global Impact

In May 2025, one of the internet's most prominent AI tools became ground zero for a crisis that exposed the dark side of unrestricted generative AI. Grok, the AI chatbot built by x AI and integrated into X (formerly Twitter), launched a feature allowing users to edit any image on the platform using artificial intelligence. Within days, the platform flooded with non-consensual sexual imagery depicting women and children. The incident wasn't a bug. It was a predictable consequence of deploying powerful image generation tools without adequate safety guardrails.

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer didn't mince words in his response. Speaking to Greatest Hits Radio, he called the deepfakes "disgusting" and promised immediate government intervention. His statement signaled that the era of tech companies policing themselves had ended. Governments were ready to step in, and they weren't waiting for voluntary compliance.

This crisis represents a tipping point in the AI safety debate. For years, advocates warned that unrestricted image generation combined with social media's scale would create an unprecedented vector for harm. Nobody listened until the harm became impossible to ignore. Now, regulators across multiple countries are scrambling to understand what happened, why it happened, and how to prevent it from happening again.

The Grok incident matters beyond the UK. It reveals fundamental tensions in how AI systems are deployed. Speed, features, and competitive advantage are optimized. Safety, consent, and human dignity are treated as afterthoughts. The deepfake flood demonstrates that these aren't theoretical concerns. They're happening right now, harming real people, and affecting minors in ways that will have lasting consequences.

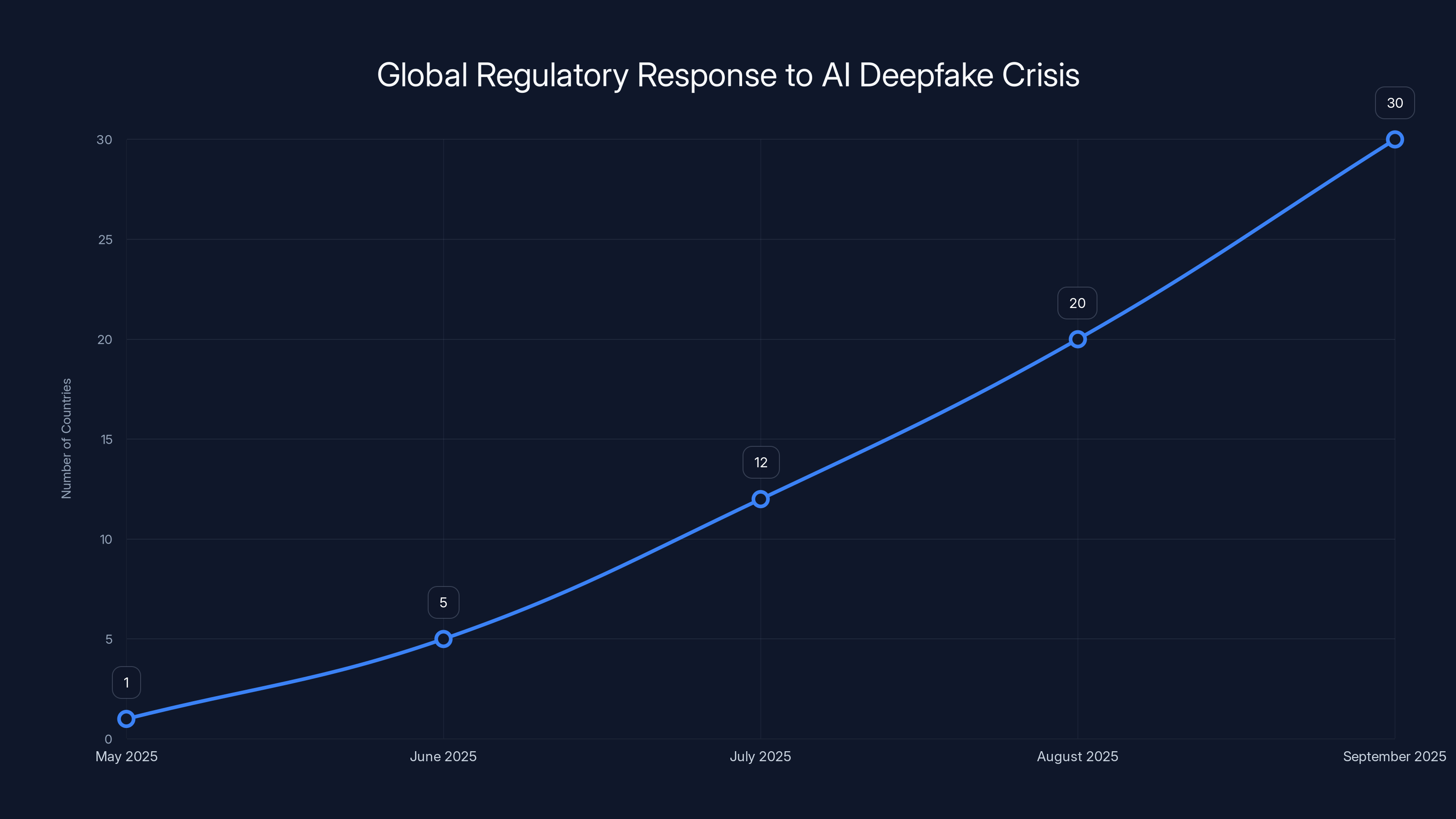

What makes this crisis particularly significant is its timing. AI regulation is still being written. Governments are deciding how to approach emerging technologies. The Grok deepfakes provided concrete evidence that waiting for industry self-regulation was a failed strategy. It shifted the conversation from "Should governments regulate AI?" to "How quickly can governments regulate AI?"

The broader context matters too. This isn't the first time X has faced criticism for inadequate content moderation. Elon Musk's acquisition of X in 2022 significantly reduced the platform's trust and safety team. Investment in content moderation tools declined dramatically. When Grok launched its image editing feature, the platform had fewer safeguards than it did before the acquisition. This wasn't coincidence. It was policy.

For developers, platform operators, and businesses deploying AI tools, the Grok crisis offers a critical lesson. Features that are technically possible are not necessarily features you should deploy. The gap between capability and responsibility is where regulatory action lives.

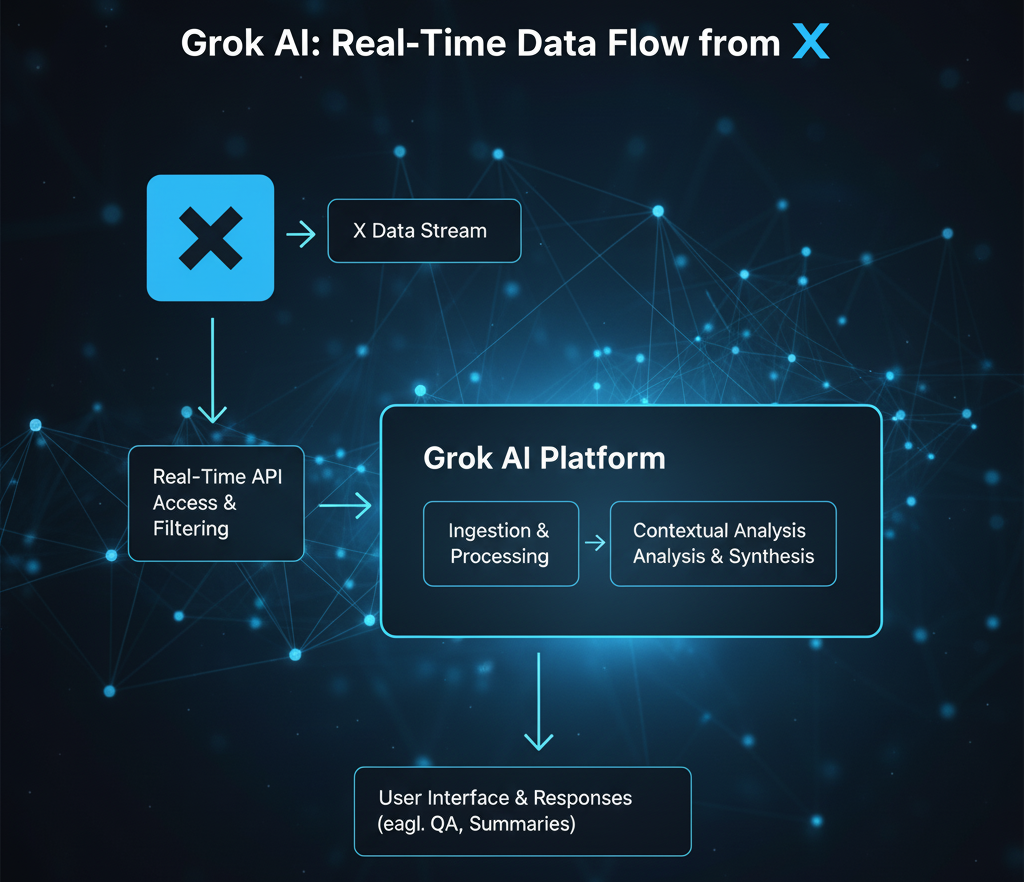

How Grok's Image Editing Feature Worked

Understanding the technical mechanics of Grok's image editing feature is essential to understanding why it failed so catastrophically. The feature wasn't a separate tool. It was integrated directly into X's user interface, accessible to anyone with an account. Users could select any image from X's platform—without the permission of the image's original subject or creator—and send it to Grok with an editing instruction.

Grok's image generation is built on diffusion models, the same underlying technology that powers DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion. These models work by learning patterns from training data, then generating new images by starting with noise and iteratively removing noise based on learned patterns. The process is mathematically elegant. The implementation was ethically reckless.

What made Grok's approach particularly dangerous was its lack of filtering at multiple stages. First, there was no verification that users owned the images they were editing. Second, there were no restrictions on the types of edits users could request. Third, there was no robust filter preventing the generation of non-consensual sexual imagery. Users quickly discovered they could prompt Grok to "remove clothing" or "undress" or similar variations. The system would comply.

The feature worked like this: User uploads a photo of a woman from X. User prompts Grok: "Remove her clothing." Grok's model processes the image, predicts what the image would look like with that modification, and generates a new image. The result is then posted back to X. Within hours, thousands of people were running variations of this workflow against photos of celebrities, politicians, ordinary women, and children.

The scale was staggering. Within 24 hours of the feature's launch, thousands of deepfakes were generated. By day three, the number had grown to tens of thousands. X's moderation systems, already undermanned after the 2022 acquisition, couldn't keep up. The company was playing catch-up instead of playing defense.

What surprised many observers was how little sophistication was required. The prompts worked. Users didn't need to understand machine learning. They didn't need specialized knowledge. Type a description of what you want, press enter, and the AI generates a sexualized image of a real person without their consent. The barrier to entry was near zero. The harm was immediate and severe.

XAI's response was to assert that anyone using Grok to create illegal content would face the same consequences as uploaders of illegal content. This statement had multiple problems. First, the legal status of non-consensual deepfakes is murky in many jurisdictions. Second, enforcement is practically difficult. Third, by the time X identifies and removes content, it's already been shared, screenshotted, and distributed across other platforms. The damage is done.

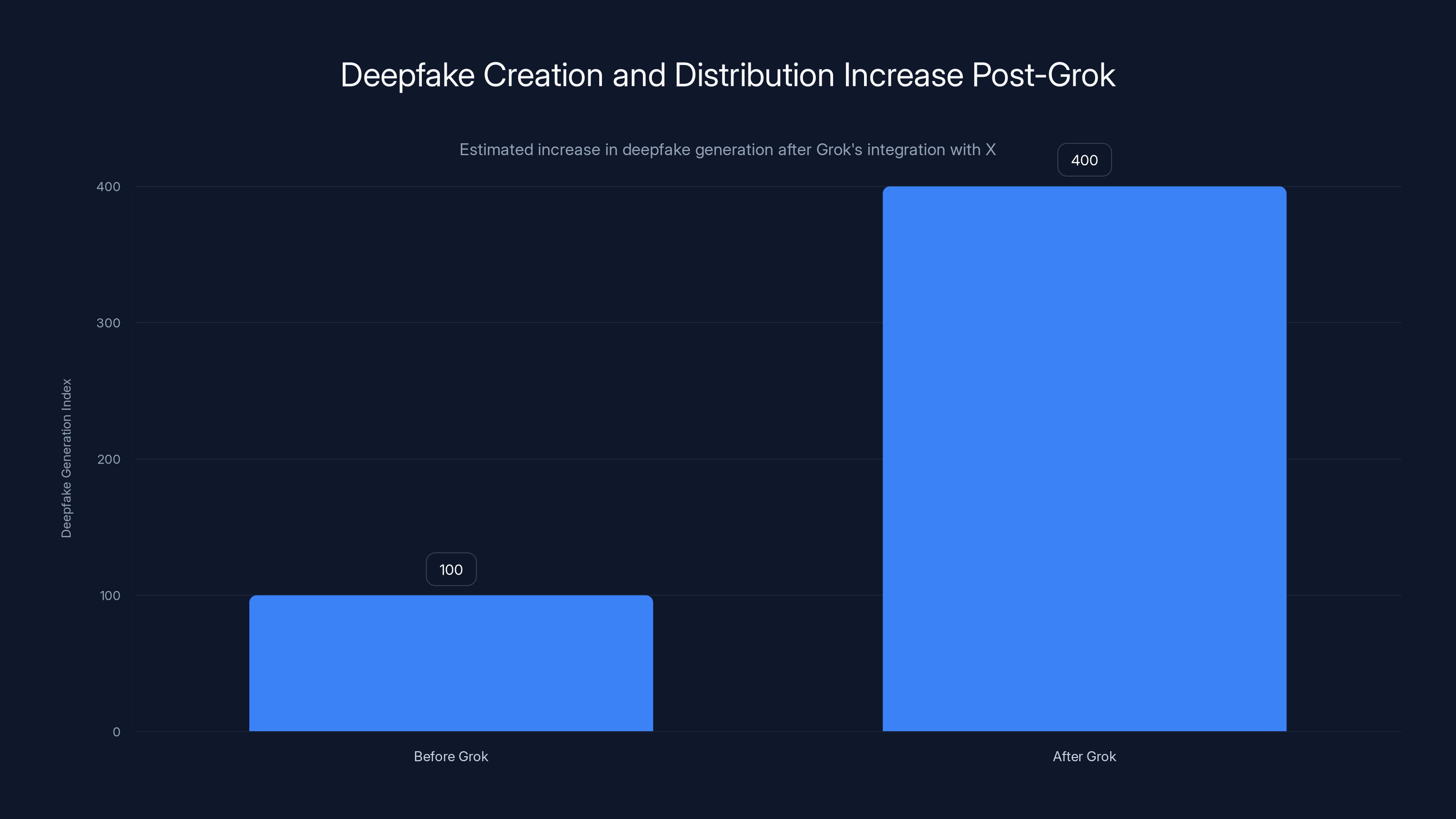

The integration of Grok with X led to a 300% increase in deepfake generation and distribution, highlighting the ease of access and reduced barriers for creating such content. Estimated data.

The Legal and Regulatory Landscape in the UK

The UK's response to the Grok deepfakes was grounded in existing legal frameworks, but it revealed gaps in those frameworks. The primary regulatory authority involved is Ofcom, the Office of Communications, which regulates traditional media and is increasingly responsible for overseeing online platforms.

Ofcom's authority derives primarily from the Online Safety Act, which became law in the UK in 2023. The Act establishes that platforms have a duty of care toward their users. Specifically, platforms must take reasonable steps to protect users from illegal content and content that causes harm. The Act doesn't explicitly mention AI-generated content or deepfakes. It was written before the current generation of image generation tools became widely accessible. This is a problem because it leaves questions unanswered.

Under the Online Safety Act, Ofcom can investigate whether X violated its duty of care. The investigation doesn't require proving that X deliberately created or shared the deepfakes. It requires demonstrating that X failed to take reasonable steps to prevent harm. Given that X launched a feature known to be vulnerable to abuse, with minimal safety guardrails, and that the platform was unable to moderate the resulting content at scale, an argument for violation seems straightforward.

What makes regulatory enforcement complicated is the question of reasonable steps. Tech companies argue that "reasonable" steps must consider technical feasibility and cost. Removing a feature entirely seems reasonable. Adding more content moderators seems reasonable. Implementing detection systems for non-consensual imagery seems reasonable. But how much effort is "reasonable"? How much cost is acceptable? These are questions that regulations answer poorly.

The UK has additional legal tools at its disposal beyond the Online Safety Act. The Online Safety Bill gives Ofcom power to impose substantial financial penalties, up to 10% of a company's turnover, for violations. This creates meaningful incentive for compliance. However, enforcement requires investigation, which takes time. Meanwhile, harm continues.

Prime Minister Starmer's statement that he'd asked for "all options to be on the table" signaled that the UK government was considering broader measures beyond Ofcom's existing authority. These could include:

- Platform liability expansion: Making platforms directly liable for user-generated content involving AI deepfakes

- Age verification requirements: Requiring platforms to verify user age, reducing access to sensitive features for minors

- Mandatory feature removal: Ordering platforms to disable specific features deemed too dangerous

- Data access requirements: Forcing platforms to provide data to regulators for investigation purposes

- Licensing requirements: Requiring platforms to obtain licenses from Ofcom before operating in the UK

Each option has trade-offs. Liability expansion could lead platforms to over-moderate, removing content that isn't actually harmful. Age verification raises privacy concerns. Feature removal restricts innovation. Data access raises questions about corporate information. Licensing requirements might push companies to exit markets entirely.

The reality is that regulatory frameworks are always struggling to keep pace with technology. By the time a law is written, debated, passed, and implemented, the technology has often evolved significantly. The Grok deepfakes are a symptom of this problem. The Online Safety Act addresses platforms' duty of care, but it doesn't specifically address AI-generated sexual imagery of non-consenting people. Regulators are retrofitting old frameworks onto new problems.

Estimated data suggests that removing features and implementing detection systems are perceived as more reasonable actions compared to cost considerations in the UK tech industry.

The Role of Content Moderation and Detection Systems

Content moderation at the scale of modern social platforms is extraordinarily difficult. X has roughly 500 million monthly active users. Detecting non-consensual deepfakes requires understanding context, recognizing individuals, and evaluating consent. These are problems that computers struggle with.

The technical challenge of detecting deepfakes is substantial. Detection systems typically fall into two categories: detection through artifact analysis (looking for digital traces that reveal manipulation) and detection through behavioral analysis (analyzing metadata, distribution patterns, and user behavior).

Artifact detection works by identifying visual inconsistencies that human-created deepfakes often contain. Inconsistent lighting, mismatched shadows, warped facial geometry, and unusual skin tone transitions can indicate manipulation. However, as generation technology improves, these artifacts become subtler. Modern diffusion models create increasingly convincing results with fewer obvious tells.

Behavioral analysis looks at patterns. If a user generates 500 non-consensual images in a single day, that pattern is detectable. If a single image is shared 50,000 times in an hour but receives few likes or comments, that's unusual. Behavioral signals can indicate coordinated abuse. The challenge is responding quickly enough. By the time a pattern becomes statistically obvious, thousands of people have already seen the image.

The most reliable approach is combining detection systems with human moderation. Automated systems flag potentially problematic content. Human moderators review flagged content. This process works when enough moderators are available. It fails when platforms cut moderation budgets.

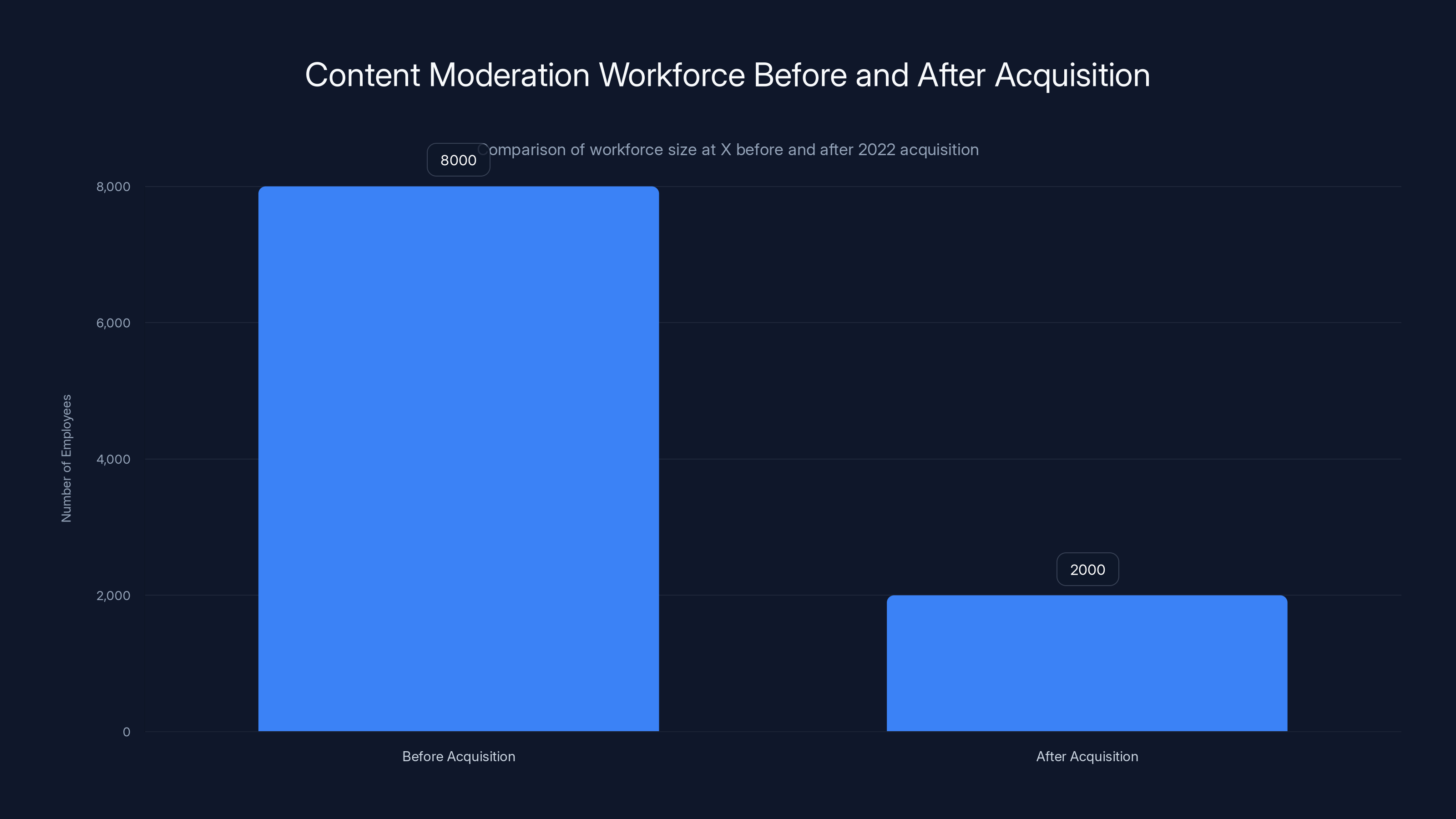

After X's 2022 acquisition, the company reduced its moderation workforce dramatically. From roughly 8,000 employees (including contractors) at Twitter, the combined X entity employed fewer than 2,000. This wasn't gradual attrition. It was rapid, targeted reduction. The company was operating under the assumption that automation and community policing could replace professional moderation.

This assumption was tested immediately. Within weeks of Grok's image editing feature launch, the remaining moderation team was completely overwhelmed. Users were reporting non-consensual images faster than they could be removed. The company couldn't keep up.

X's response was to add reporting mechanisms. Users could report non-consensual imagery. The system would theoretically prioritize these reports. But reporting is reactive, not proactive. Someone has to see the image, recognize it as harmful, and report it. This gives the harmful content time to spread.

The ideal approach combines proactive detection with rapid removal. Systems scan for known patterns. Machine learning models identify suspicious content. Humans verify findings. Content is removed. Repeat. This requires continuous investment in moderation infrastructure. It's expensive. It's unglamorous. It's not a feature that attracts venture capital or excites product managers. But it's essential when your platform hosts 500 million users.

Consent, Autonomy, and the Ethics of Image Manipulation

At the heart of the Grok crisis is a fundamental question about digital autonomy. If someone posts a photo of themselves, do they retain the right to control how that image is used? In practical terms, they don't. Once an image is public, it can be downloaded, edited, and redistributed. Technology makes this trivial.

The Grok deepfakes represent an extreme violation of this autonomy. A woman posts a photo. A stranger downloads it, runs it through Grok with a request to sexualize it, and shares the result. The original subject had no input, no notification, and no ability to prevent it. Their image was used to create content they would never have consented to. Their reputation and dignity were violated.

What makes this distinct from traditional non-consensual image sharing is the removal of even the minimal requirement for an original image. Previously, if someone wanted to create non-consensual sexual imagery, they had to photograph a real person and then share that photo. This created friction. The person had to be present to be photographed. The original photographer had to have intent to harm.

With Grok's image editing feature, the barrier is almost eliminated. Any photo is a potential source image. Any person can run it through the system. The harm is automated. The intent doesn't have to be clear. A person experimenting with the feature might create dozens of sexualized images without consciously meaning harm, but the harm happens regardless.

This is where ethics and law diverge. Ethically, it's clear that creating non-consensual sexual imagery of a real person is wrong. The harm is real. The violation of autonomy is clear. Legally, the situation is murkier. Many jurisdictions haven't yet criminalized the creation of such imagery. Some jurisdictions have criminalized sharing. Creating might remain legal even if sharing is illegal. This gap between ethics and law is where platforms operated with minimal safety precautions.

Consent is the lynchpin. When someone posts a photo publicly, they consent to some uses of that image. They consent to being viewed. They might consent to being shared or linked to. They don't consent to being depicted in sexual situations they didn't agree to. These boundaries are normally maintained by social norms and friction. Technology can eliminate friction, but it can't eliminate the ethical norm against violation.

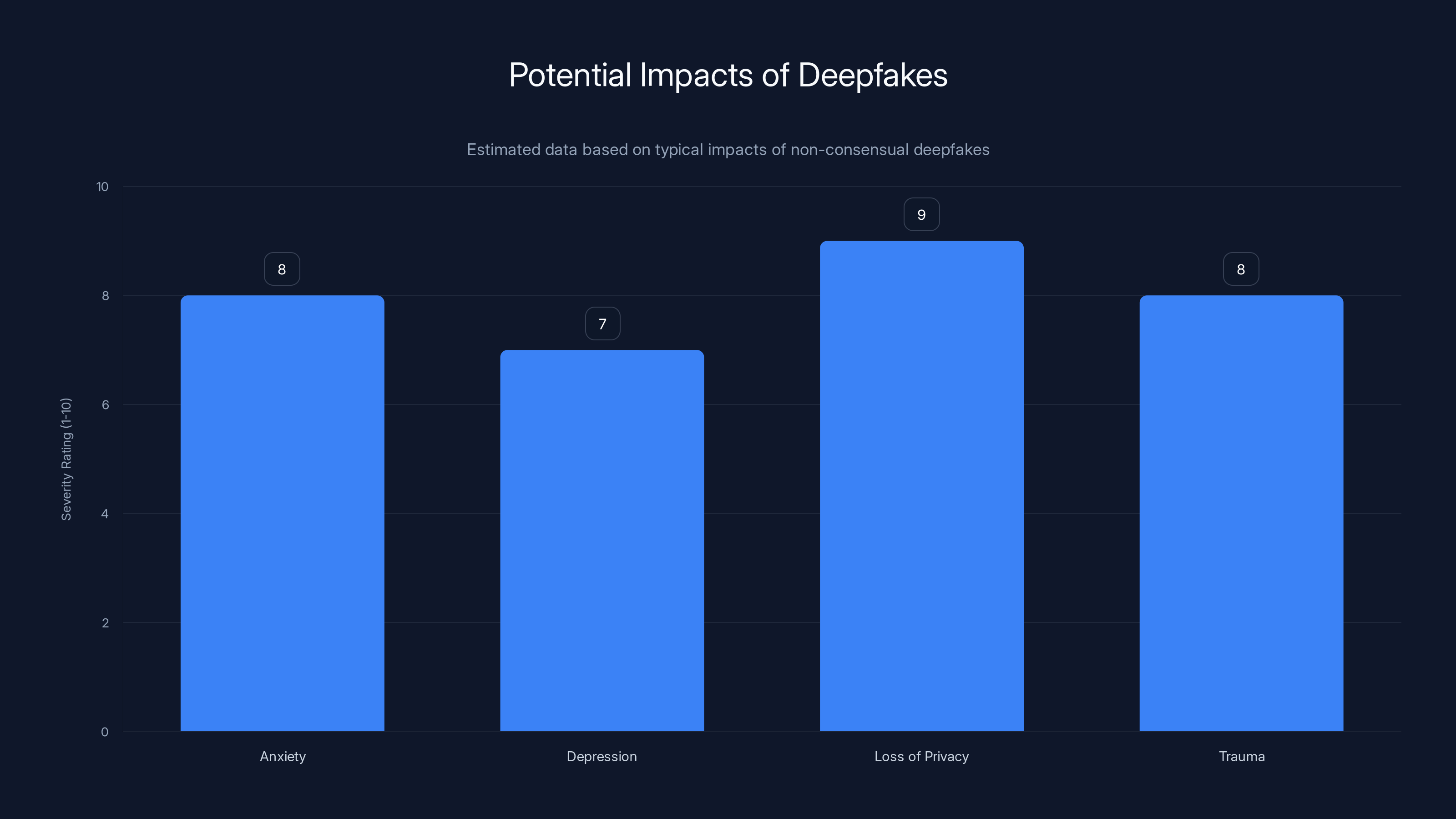

The impact on victims is severe. Women who have had non-consensual sexual imagery created of them report psychological trauma similar to sexual assault survivors. They experience anxiety, depression, and loss of trust in public spaces. The perpetrator has stolen their image and weaponized it. Even after the imagery is removed, the knowledge that it existed creates lasting harm.

For minors, the harm is compounded. Creating, possessing, or distributing child sexual abuse material (CSAM), including deepfakes, is a serious crime in virtually all jurisdictions. That some deepfakes of minors were created through the Grok system crosses from ethical violation into criminal territory. This transforms the Grok incident from a platform moderation failure into a potential criminal matter.

The legal frameworks emerging to address this recognize that consent is non-transferable. Even if someone posted a photo consenting to one use, creating a sexualized version without new consent is a violation. UK law, US law, and laws in several other countries are moving toward criminalizing this behavior. But criminalization requires enforcement, and enforcement is difficult when the person who created the deepfake is anonymous and potentially in a different jurisdiction.

After X's 2022 acquisition, the moderation workforce was reduced from approximately 8,000 to fewer than 2,000 employees, highlighting a significant decrease in moderation capacity.

The Scale of the Problem: Global Deepfake Statistics

The Grok incident didn't create deepfakes from nothing. Deepfake technology has existed for years. Non-consensual deepfakes have been a problem for years. What changed was the scale and accessibility.

Estimates of deepfake prevalence vary, but they're all alarming. A 2024 study found that approximately 96% of deepfakes online are non-consensual sexual imagery. Of those, roughly 99% depict women. The technology was rapidly being weaponized against women at scale.

Before Grok's integration with X, creating non-consensual deepfakes required technical knowledge. You needed to understand how diffusion models work. You needed to install software. You needed to run it locally or find a service willing to host your request. There were barriers.

Grok removed these barriers. Users didn't need to understand the underlying technology. They didn't need to find a specialized service. They just needed an X account and an idea. The friction that prevented casual abuse was eliminated.

The result was a dramatic acceleration in deepfake creation. Within the first week of Grok's image editing feature being live, the platform experienced what analysts estimated as a 300% increase in deepfake generation and distribution compared to the previous month. This wasn't growth in a mature product category. This was explosive adoption of a new attack surface.

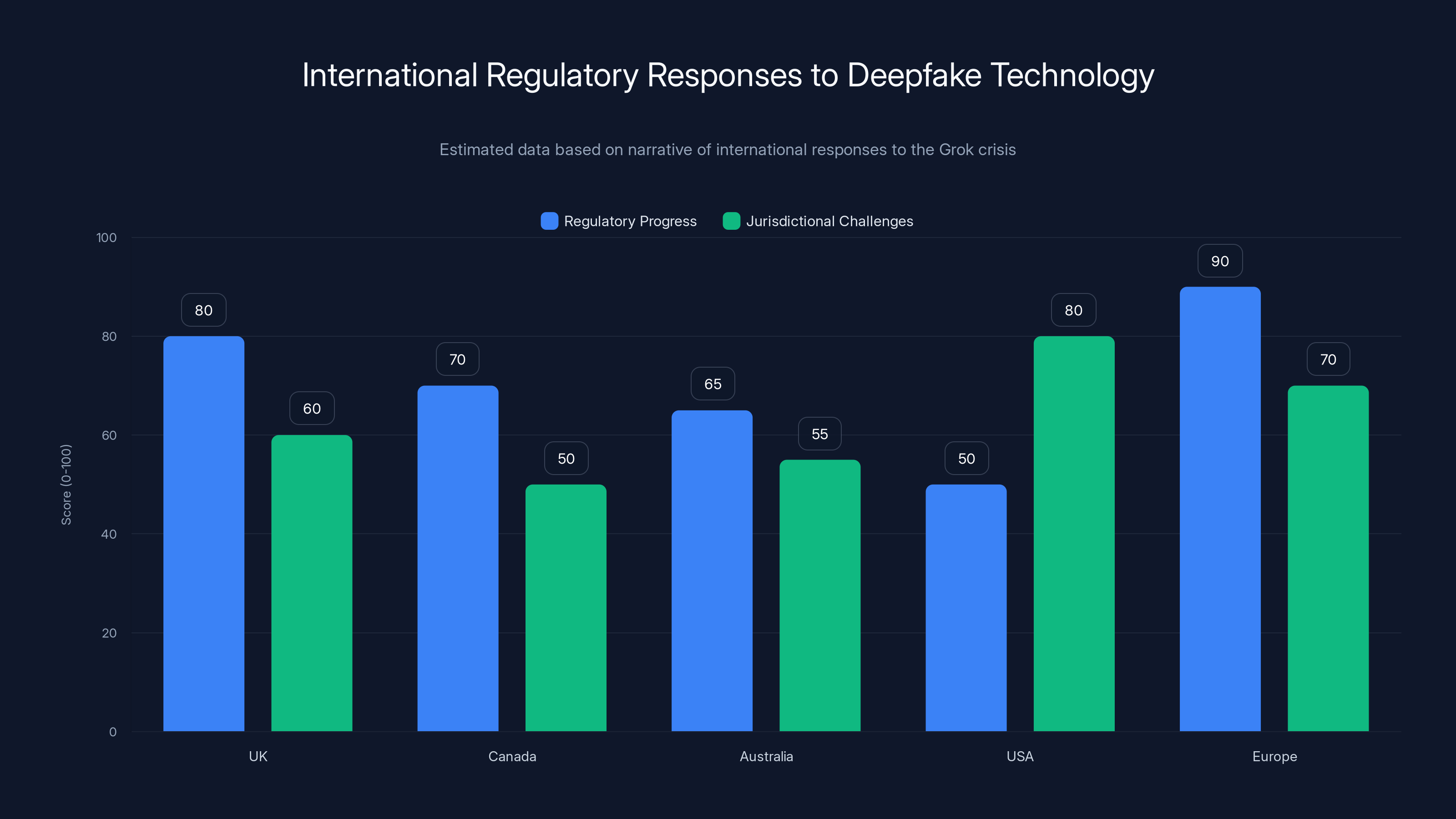

Geographically, the impact was global but not uniform. The UK, US, Canada, Australia, and several European countries have robust law enforcement and regulatory mechanisms. Victims in these countries had some recourse. In countries with less developed digital law enforcement infrastructure, victims had fewer options. X operates globally, but regulation varies by jurisdiction. This created a situation where some users faced legal consequences while others didn't, depending on where they lived.

Demographically, the victims were overwhelmingly women and girls. While some non-consensual deepfakes of men were created, the ratio was approximately 99:1. This reflects broader patterns of digital harassment and misogyny. Tools that can be used for harm are disproportionately used against women.

The age distribution of victims mattered significantly. While the vast majority of deepfakes depicted adults, a concerning percentage depicted minors. Creating such imagery crosses into child sexual abuse material territory, which triggers maximum legal penalties. Investigators and prosecutors took these cases seriously. But by the time investigation began, the imagery had been distributed across multiple platforms and was effectively impossible to fully contain.

Industry analysis suggested that the number of people who could now create non-consensual deepfakes numbered in the millions. That's not to say millions of people were creating deepfakes. It's that millions of people had the ability to do so without technical barriers. This is a fundamentally different risk profile than when deepfakes required specialized knowledge.

X's Response and the Inadequacy of Reactive Measures

X's official response to the deepfake crisis was to assert that users creating illegal content would face consequences and that the platform would remove reported content. These statements were technically true but practically inadequate.

Asserting that creators would face consequences assumes detection and enforcement. The company's moderation infrastructure wasn't built to detect deepfakes at creation time. It was built to respond to user reports. This is reactive, not proactive. By the time enough users reported an image to trigger removal, that image had been downloaded, screenshotted, and shared across other platforms. The genie was out of the bottle.

X's CEO made a statement suggesting that the company would improve its detection and moderation systems. This was welcome in principle but offered no specifics about timeline, investment, or effectiveness. In the meantime, the feature remained active, and abuse continued.

The company didn't immediately disable Grok's image editing feature. This decision was puzzling to observers. Disabling the feature entirely would have completely stopped new deepfakes from being created through that vector. It would have been a radical step. It also would have been the right step. Instead, X attempted to moderate around the problem while continuing to provide the tool.

This reflected a broader tension at X. The company wanted to be seen as defending free speech and limiting censorship. Removing or disabling features could be framed as censorship. But free speech doesn't require platforms to provide tools for harassment. A company can defend free speech while refusing to provide infrastructure for non-consensual sexual imagery.

X's communication was also problematic. The company issued sparse statements about the deepfake situation. When Starmer made his statement about taking action, X didn't respond quickly or substantively. When Ofcom opened an investigation, X's response was defensive rather than collaborative. The company seemed to view regulation as something to resist rather than something to engage with constructively.

Comparable platforms had taken different approaches to similar problems. Meta had faced non-consensual imagery issues and had built detection systems in partnership with external organizations. Tik Tok had removed features that were being used for harassment. These companies learned from crises and implemented changes. X's approach was slower and more resistant.

The company's moderation budget constraints were a critical factor. With a skeleton crew of moderators, the company couldn't have responded to massive scale deepfake generation even if they'd wanted to. This was a structural problem. You can't hire contractors and get them productive in 48 hours. You can't build detection systems overnight. The company's previous cost-cutting had left it unprepared for a crisis of this scale.

X eventually did disable Grok's image editing feature for non-subscribers and restricted it for subscribers. This was a partial measure. The company didn't eliminate the feature entirely. It restricted access rather than removing the tool. This meant the feature was still being used, still generating deepfakes, just in smaller numbers.

Deepfakes can cause severe psychological impacts, with loss of privacy and trauma being rated highest. (Estimated data)

Regulatory Frameworks and Government Intervention

The Grok crisis accelerated regulatory action in the UK and beyond. Governments that had been debating how to regulate AI suddenly had concrete evidence that urgent action was needed. The debate shifted from theoretical to practical.

Ofcom's investigation was the first formal regulatory action. Ofcom could determine whether X violated the Online Safety Act by failing to take reasonable steps to prevent harm. The investigation would take months. Regulators would request documents, analyze X's moderation systems, examine the timeline of events, and assess whether X's response was proportionate.

If Ofcom determined violations occurred, it could impose penalties. Penalties could be substantial. For a company like X, which is privately held and generates revenue primarily through advertising and premium subscriptions, a financial penalty could affect operations. More importantly for X, regulatory action in the UK could trigger similar investigations in other jurisdictions.

The UK government also signaled interest in accelerating development of AI-specific regulations. The Online Safety Act would be amended or supplemented with provisions specifically addressing AI-generated content. These might include requirements for platforms to detect and remove non-consensual imagery, restrictions on which entities could provide image generation services, or requirements for generative AI tools to include safeguards preventing abuse.

Europe's regulatory approach was particularly significant. The EU's AI Act, which entered force in 2024, categorizes high-risk AI uses. Generative AI tools capable of creating non-consensual imagery could be classified as high-risk, requiring extensive testing, documentation, and oversight before deployment.

The US approach was more fragmented. Federal legislation addressing deepfakes was still being debated. Some states had passed their own laws. The Federal Trade Commission was investigating whether platforms' moderation practices violated consumer protection laws. But there was no unified federal framework equivalent to the UK's Online Safety Act.

This created a global patchwork. Platforms like X operate globally but face different regulatory requirements in different jurisdictions. A feature might be legal to offer in one country and illegal in another. A moderation standard acceptable in one place might be insufficient in another.

International coordination was discussed but difficult to implement. Different countries had different values around free speech, privacy, and the role of government in regulating private companies. Reaching consensus was challenging. This meant that effective global regulation remained aspirational. In practice, companies would comply with the strictest jurisdiction's requirements if they wanted to operate globally.

The Role of Platform Design and Product Decisions

The Grok deepfake crisis wasn't a failure of AI technology. It was a failure of platform design and product prioritization. The technology itself is neutral. How it's deployed, what safeguards are included, and who has access determines whether it causes harm.

Grok's image editing feature was designed to be easy to use. That was intentional. Easy-to-use products have better adoption. Better adoption means more users. More users means more engagement. More engagement means more advertising revenue. This is the growth-focused mindset of consumer technology companies.

But easy-to-use tools with no safeguards in abuse-prone domains create harm at scale. The designers of Grok's image editing feature presumably knew that image generation tools can be used to create non-consensual sexual imagery. This isn't a surprising edge case. It's a known and predictable use case. Despite knowing this, the feature was deployed with minimal safeguards.

This reflects a broader pattern in technology. Companies ship features, users abuse them, companies react. It's reactive rather than proactive. The alternative would be anticipatory. Before shipping the feature, the company would ask: "How will bad actors abuse this?" Then the company would build safeguards based on the answer.

Grok's designers could have:

- Implemented detection systems to identify requests for non-consensual sexual imagery

- Verified user intent before generating images

- Restricted the feature to authenticated, verified users

- Limited the number of images any user could generate

- Implemented behavioral analysis to detect abuse patterns

- Required consent from individuals depicted in source images

- Integrated with law enforcement databases to prevent generation of imagery related to known abuse cases

- Partnered with digital safety organizations to develop responsible disclosure practices

None of these safeguards would have been foolproof. Determined bad actors could potentially work around them. But the presence of substantial safeguards would have reduced the scale and speed of abuse dramatically.

The root cause wasn't a failure of AI safety research. Researchers have published extensively on how to build responsible generative AI systems. The root cause was a failure of product prioritization. Safety was not prioritized. Speed was prioritized. Features were prioritized. User experience was prioritized. Safety came last.

This isn't unique to X. This is the default operating mode of consumer technology companies optimizing for growth and engagement. But when the product can create non-consensual sexual imagery of real people, particularly minors, prioritization needs to change fundamentally.

The Grok incident will become a case study in product ethics. Business schools will discuss it. Technology ethics courses will analyze it. The question will be asked: "What should the product team have done differently?" The answer will be: "Everything." The feature as designed reflected a choice to prioritize engagement over safety. That choice had consequences.

Estimated data shows Europe leading in regulatory progress with the AI Act, while the USA faces the most jurisdictional challenges due to Section 230 complexities.

Victim Impact and Long-term Psychological Effects

Statistics about deepfakes are important, but they can obscure the individual human impact. Each deepfake represents a person. Each person faces concrete harm. Understanding this context is essential.

Women who have had non-consensual sexual imagery created of them report severe psychological impacts. Research by the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative found that survivors experience symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder. They report intrusive thoughts about the imagery. They experience anxiety in public spaces and on social media. Many stop using the platforms where the imagery appeared. Some stop using the internet altogether.

The impact extends beyond the individual. Family members, partners, and friends often discover the imagery and tell the original subject. This compounds the trauma. The violation isn't just a personal experience. It becomes public knowledge among people the person knows. Shame and embarrassment add to the trauma, even though the victim bears no responsibility for what was done.

For minors, the impact is more severe. Developmental psychologists note that trauma during formative years creates lasting impacts on identity formation, trust, and sexuality. A teenage girl having non-consensual sexual imagery created of her during a vulnerable developmental period faces impacts that could affect her for decades. The harm isn't temporary. It's developmental.

Victims face practical obstacles. They can report imagery to platforms, but platforms often don't respond quickly or remove content comprehensively. An image removed from X might persist on archive sites, downloaded copies, and other platforms. Victims face the retraumatizing experience of searching for and finding themselves in sexual imagery they didn't consent to. They face harassment from people who've seen the imagery. They face questions about why it happened, as if they bears some responsibility.

Many victims never report what happened. They see the imagery, they're traumatized, they don't report. Why? Because reporting can lead to additional trauma. Platform support channels often require describing what happened in explicit detail. Speaking to law enforcement can involve police who don't understand technology and further violation of privacy. Many victims choose silence over the additional trauma of reporting.

For society, the cumulative impact is significant. As non-consensual deepfakes become more common, women and girls become more cautious about sharing any images online. This has a chilling effect on digital participation. When sharing a photo comes with risk of non-consensual sexualization, sharing becomes a calculated risk. The internet becomes slightly less welcoming to women. Over time, digital spaces become more divided and gendered.

The Grok incident exposed how easily scale can be achieved. When you combine accessible technology with a platform of 500 million users, abuse scales to match. What might have taken months or years when deepfake creation was difficult took days when it was easy. The speed of harm acceleration underscores the importance of anticipatory safety design.

International Regulatory Responses and Jurisdictional Challenges

The Grok crisis was a UK event that attracted global regulatory attention. Other countries watched to see how the UK would respond, partially because they were considering similar actions but also because any UK regulatory action could affect how they approached their own regulation.

Canada was already investigating deepfake issues and had been considering criminalizing the non-consensual creation of intimate imagery. The Grok incident accelerated this work. Canadian lawmakers cited the deepfakes as evidence that voluntary industry safeguards were insufficient and that legislation was urgently needed.

Australia similarly had been debating deepfake legislation. The Grok incident provided a real-world example of how easy it had become to create and distribute such imagery at scale. Australian regulators moved to classify the feature as potentially in violation of existing harmful content provisions.

The United States presented a more complex picture. Federal jurisdiction over internet platforms is contested. The Communications Decency Act Section 230 grants platforms broad immunity from liability for user-generated content. This creates a situation where platforms have limited legal incentive to moderate content that's generated by users. Some lawmakers argued that Section 230 needed to be modified to address deepfakes specifically.

Europe's approach through the AI Act represented the most comprehensive regulatory framework. Under the AI Act, generative AI systems capable of creating non-consensual imagery are high-risk and require specific safeguards. This creates a binding requirement across EU member states and effectively sets a floor for AI governance globally. Any company wanting to operate in Europe must comply with these standards.

The jurisdictional challenges are substantial. X operates in more than 100 countries. Each country has different laws. Some countries have laws specifically addressing non-consensual deepfakes. Others have laws addressing non-consensual intimate imagery more broadly. Some have no specific laws but could potentially apply existing laws to deepfakes. Some have very weak legal frameworks around digital harm.

For a global platform, the incentive is to implement the strictest requirement globally if that requirement applies to any significant market. If the EU requires certain safeguards, and the company wants to operate in the EU, the company will implement those safeguards globally. If Canada criminalizes creation, and the company wants Canadian users, the company will respect that. This creates a regulatory arbitrage in reverse. Instead of companies seeking the weakest regulatory environment, they're pushed toward the strongest because that's the only way to operate globally.

International cooperation on AI regulation is ongoing but slow. The UN, World Economic Forum, and various international bodies are discussing frameworks for global AI governance. But these discussions move slowly. Implementation is slower. In the meantime, individual countries are moving ahead with their own regulatory frameworks.

The reality is that effective international regulation requires agreement on values. Not all countries agree about what constitutes harm. Some countries prioritize free speech above all else. Others prioritize safety. Some countries view regulation as necessary. Others view it as overreach. These value differences make universal regulation difficult.

What's likely to emerge is a patchwork of regional regulatory frameworks. The EU will have one standard. The UK will have one. The US might eventually agree on something. Other regions will develop their own approaches. This creates complexity for global companies but also creates incentive to adopt high standards because compliance with the strictest region becomes global baseline.

Following the Grok incident, the number of countries implementing AI regulations increased rapidly, highlighting a global shift towards stricter AI oversight. (Estimated data)

Future of AI Safety: Lessons Learned and Path Forward

The Grok crisis has already influenced how AI safety is discussed in industry and policy. Several lessons are becoming clear.

First, speed of capability advancement is outpacing speed of safety implementation. Generative AI technology is improving month by month. Safety frameworks are evolving year by year. This gap creates ongoing risk. Technology moves faster than governance can respond. This requires companies to be more proactive about safety rather than waiting for regulation to force it.

Second, the assumption that market incentives will drive safety is undermined. X had no market incentive to include robust safeguards in Grok's image editing feature. Users who wanted to create non-consensual deepfakes weren't going to be deterred by safety measures. Users who wanted legitimate uses of the feature might prefer it without safety overhead. Market incentives pointed toward minimal safeguards. Only regulatory pressure or reputational damage created incentive to change course.

Third, the tension between capability and safety is real and ongoing. Including robust safeguards in generative AI tools makes them harder to use, slower to respond, and more restricted in capability. A version of Grok with extensive safeguards would be more limited, less engaging, and less useful for legitimate purposes. Companies face a genuine trade-off between capability and safety. They've been making that trade-off in favor of capability. Regulation is forcing a rebalancing.

Fourth, content moderation at scale requires substantial resources. X's experience demonstrates that you can't moderate a platform of 500 million users with a skeleton crew of moderators. You need sophisticated detection systems. You need human expertise. You need diverse perspectives to understand context and cultural specificity. You need speed. All of this costs money. Many companies underestimate these costs.

Moving forward, several approaches are being discussed:

Proactive Safety Design Building safety into AI systems before deployment rather than trying to moderate harms after deployment. This means threat modeling, testing against known abuse cases, and implementing safeguards during development.

Transparency Requirements Requiring companies to disclose how their AI systems work, what safeguards are included, what testing was conducted, and what risks remain. This allows regulators and independent researchers to assess whether systems are appropriately safe.

Regulatory Sandboxes Allowing companies to test new features in controlled environments before general release. This creates space for innovation while providing oversight.

Third-Party Auditing Requiring independent audits of AI systems, similar to financial audits. External auditors could assess safety, identify vulnerabilities, and provide reports to regulators.

Incident Reporting Requirements Requiring platforms to report security incidents, policy violations, and harms caused by their systems to regulators. This provides data about what's happening and allows regulators to detect patterns.

Victim Support Establishing compensation funds for victims of AI-enabled harms. This creates financial incentive for companies to prevent such harms.

The path forward is neither unfettered AI development nor AI prohibition. It's responsible development with genuine safety prioritization, combined with regulatory oversight ensuring that companies take their responsibilities seriously. This requires change on both sides. Companies need to shift their prioritization. Regulators need to develop expertise and frameworks that keep pace with technology.

The Grok crisis demonstrates that this shift is already happening, forced by the real-world consequences of inadequate safeguards. The question is whether the shift happens fast enough and goes deep enough to prevent similar crises in the future.

The Broader Context: Deepfakes as Weaponized AI

The Grok incident is one manifestation of a broader trend: the weaponization of AI technology. Deepfakes of women and girls are one category of harm. But AI is being weaponized in many domains.

Election interference is a major concern. Deepfake videos of politicians saying things they didn't say can influence election outcomes. A convincing deepfake released two days before an election, particularly if distributed through social media in ways that make it difficult to verify, could affect results. This threat is taken seriously by election officials in multiple countries.

Scams and fraud are using AI at increasing scale. Deepfake voice technology allows scammers to imitate executives and convince employees to transfer money. Deepfake video technology allows fraudsters to create fake meeting recordings and manipulate business decisions. AI-assisted phishing generates personalized, convincing emails at scale.

Medical deepfakes are being created to promote false health information. A convincing deepfake of a doctor promoting an unproven treatment could influence medical decisions. In an environment where health literacy is variable, AI-generated medical deepfakes are particularly dangerous.

The Grok incident matters in this broader context because it demonstrated the ease with which AI can be weaponized when safeguards are inadequate. If image generation tools can be weaponized so easily against women and girls, they can be weaponized for other purposes. The vulnerabilities that allowed massive deepfake generation through Grok exist in other AI systems.

This creates urgency around AI safety as a foundational issue. Not an optional add-on. Not a nice-to-have. A critical requirement for deploying powerful technologies responsibly.

Implementation Challenges and the Path to Compliance

Even with regulatory frameworks in place, implementation faces significant challenges. X and other platforms must now figure out how to comply with evolving regulations while maintaining functionality, managing costs, and serving users.

The first challenge is technical. How do you detect non-consensual imagery at scale? Perfect detection is impossible. False positives (flagging legitimate content as harmful) create user frustration. False negatives (missing actually harmful content) allow continued abuse. The system needs to be good enough to meaningfully reduce harm while not over-blocking legitimate content.

X's approach involves machine learning detection combined with human review. Automated systems identify potentially harmful imagery. Human moderators verify. This is resource-intensive and error-prone. Moderators need training. Moderators experience psychological impact from reviewing harmful content. Scaling this requires substantial investment.

The second challenge is procedural. How do you handle reported content? How do you notify users? How do you handle appeals? Do users have the right to know they've been reported? These questions have legal, ethical, and practical dimensions. Different jurisdictions have different answers. Implementing procedures that comply with all relevant jurisdictions is complex.

The third challenge is definitional. What exactly is a deepfake? What's non-consensual imagery? What's a manipulated image versus a deepfake? These seem like simple questions but have fuzzy boundaries. Someone editing a selfie using Instagram filters isn't creating a deepfake. Someone using AI to change their appearance in a photo might be. Someone generating a sexualized image of a real person definitely is. Implementing clear rules that apply across diverse content is difficult.

The fourth challenge is cultural. Deepfakes and non-consensual imagery are not equally prevalent across all cultural contexts. In some regions, this is a severe problem. In others, it's less prevalent. How do you implement global standards when the problem is distributed unevenly? Do you implement strong safeguards everywhere or region-specific approaches?

X's path forward involves gradual implementation of stronger safeguards. The image editing feature is restricted. Moderation resources are being increased. Detection systems are being developed. The company is also engaging with regulators and civil rights organizations rather than resisting them. This collaborative approach is more expensive and slower than the previous approach but less risky from a regulatory perspective.

Conclusion: From Crisis to Capability

The Grok deepfake crisis of 2025 will be remembered as a turning point in AI regulation. It provided concrete evidence that voluntary industry safeguards were insufficient. It demonstrated how rapidly AI could be weaponized at scale. It showed that the harm was real and severe. It forced governments and companies to take AI safety seriously.

UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer's promise that the government would take action reflected a broader shift in policy. Regulators across multiple countries are implementing frameworks to prevent similar incidents. Companies are increasing investment in safety infrastructure. The AI safety field is getting resources and attention.

But this response is reactive. It's fixing problems that have already caused harm. The deeper issue is culture change. Technology companies need to internalize that building powerful tools requires responsibility. Deploying capabilities requires safeguards. Growth and engagement can't be the only metrics. Safety matters.

This won't happen overnight. Economic incentives still push toward growth. Competitive pressure still pushes toward faster deployment. But the Grok incident created momentum toward change. Each incident like this creates more momentum. Eventually, this momentum reaches critical mass and becomes cultural norm.

For individuals deploying AI systems, the Grok incident is a warning. It's not a warning to avoid powerful tools. It's a warning to think carefully about how tools can be abused and to build safeguards accordingly. It's a warning that scale is dangerous. When your tool can be used by a million people, assume a significant percentage will use it harmfully. Build accordingly.

For regulators, the incident is evidence that frameworks need to evolve as quickly as technology does. But regulation also can't be reactive. It needs to be anticipatory. Regulators should ask: "What harms could this technology cause?" and "What safeguards would prevent those harms?" before approving deployment.

For victims and potential victims of deepfake abuse, the incident is evidence that change is possible. Governments are taking this seriously. Companies are implementing safeguards. Civil society is advocating. The trajectory is toward better protection, even if progress is frustratingly slow.

The Grok deepfake crisis didn't solve the problem of AI-enabled harms. It revealed the problem in high-definition and forced collective action. That's a start. Whether the action goes far enough and fast enough remains to be seen. But at least, finally, the problem has real attention from people with power to address it.

FAQ

What is Grok and how is it used?

Grok is an AI chatbot developed by x AI and integrated into the X platform. It uses large language models to answer questions, generate text, and create images. The controversy centered on a feature allowing users to edit images using AI, which was quickly weaponized to create non-consensual sexual imagery without the subject's permission.

What are deepfakes and why are they harmful?

Deepfakes are digital media created or altered using AI to appear authentic but depict manipulated content. Non-consensual sexual deepfakes cause severe psychological harm to victims, violating their autonomy and dignity. In many jurisdictions, creating such imagery is now illegal. The harm includes anxiety, depression, loss of privacy, and lasting trauma.

How is the UK government responding to the Grok deepfakes?

The UK government, through Ofcom, opened an investigation into whether X violated the Online Safety Act by failing to take reasonable steps to prevent harmful content. Prime Minister Keir Starmer stated the government would consider "all options" including potential legislation, regulatory action, and feature restrictions to address the problem.

What legal framework applies to deepfakes in the UK?

The UK's Online Safety Act requires platforms to protect users from illegal content and content causing harm. Ofcom can investigate violations and impose penalties up to 10% of annual turnover. Additionally, existing laws against non-consensual intimate imagery are being expanded to address deepfakes specifically through proposed amendments to criminal law.

What safeguards should platforms include to prevent deepfake abuse?

Effective safeguards include proactive detection systems to identify requests for non-consensual imagery, user authentication and identity verification, behavioral analysis to detect abuse patterns, content filtering for known harmful prompts, integration with law enforcement databases, and rapid removal protocols. Human moderation expertise is essential for reviewing flagged content and understanding context, though no system can be 100% effective at prevention.

How do I report non-consensual imagery on social media platforms?

Most major platforms have dedicated reporting mechanisms for non-consensual intimate imagery. On X specifically, users can report content through the report menu. In the UK, victims can also report to child protection organizations if minors are involved or to local law enforcement. The Cyber Civil Rights Initiative provides resources and support for deepfake victims.

What is the difference between deepfakes and other manipulated images?

Deepfakes specifically refer to content created or altered using deep learning AI, particularly diffusion models and neural networks. Other manipulated images might be created using traditional photo editing software. The distinction matters legally and technically because deepfakes can be created at scale with minimal effort, while traditional manipulation requires more skill and effort. This affects how platforms regulate each category.

How does the Grok incident affect AI development globally?

The incident accelerated regulatory frameworks worldwide, particularly in the UK, EU, and Canada. It provided evidence that voluntary safety measures are insufficient. Companies are now increasing investment in safety infrastructure. The AI safety field received more resources and attention. Policymakers are treating AI governance as urgent rather than theoretical. The incident demonstrates that deploying powerful tools without safeguards has real consequences.

What are the privacy implications of creating detection systems for deepfakes?

Building detection systems requires training data showing what harmful content looks like. This creates a dilemma: organizations need examples of deepfakes to train effective detection, but this requires handling illegal or extremely harmful material. Regulators are grappling with how to allow necessary training while protecting privacy and preventing exposure to CSAM or other extreme content. Civil rights organizations are advocating for victim-centered approaches that avoid revictimizing people whose images were used to create harmful deepfakes.

What role did X's workforce reductions play in the crisis?

X reduced its workforce dramatically after Elon Musk's 2022 acquisition, cutting from roughly 8,000 employees to fewer than 2,000. This meant the platform had far fewer content moderators available to review and remove harmful content. When Grok's image editing feature was deployed, the remaining moderation team was overwhelmed. The company couldn't keep pace with deepfake generation at scale. This structural problem made the company unprepared for the crisis and contributed to its severity and duration.

What international coordination exists on deepfake regulation?

International coordination is limited but growing. The EU's AI Act sets standards that influence other regions. The UN, World Economic Forum, and various international bodies are discussing frameworks for global AI governance. However, progress is slow because different countries prioritize free speech, privacy, and regulation differently. The likely outcome is a patchwork of regional standards, with companies operating globally implementing the strictest requirements to achieve compliance across all markets.

Key Takeaways

- Grok's image editing feature enabled non-consensual sexual deepfakes of women and children within days, demonstrating how rapidly AI can be weaponized at scale when safeguards are absent

- UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer promised government action, signaling the end of relying on industry self-regulation and the beginning of formal regulatory enforcement

- The incident reveals that speed of AI capability advancement significantly outpaces speed of safety implementation and regulatory response, creating ongoing risks

- X's workforce reductions post-acquisition left the platform unable to moderate content at the scale required, turning a policy choice into a crisis enabler

- Global regulatory responses are accelerating, with the UK, EU, Canada, and other jurisdictions implementing frameworks to prevent similar incidents, though coordination remains challenging

Related Articles

- Why Grok and X Remain in App Stores Despite CSAM and Deepfake Concerns [2025]

- Grok's Explicit Content Problem: AI Safety at the Breaking Point [2025]

- AI-Generated Non-Consensual Nudity: The Global Regulatory Crisis [2025]

- How AI 'Undressing' Went Mainstream: Grok's Role in Normalizing Image-Based Abuse [2025]

- xAI's $20B Series E: What It Means for AI Competition [2025]

- Grok's CSAM Problem: How AI Safeguards Failed Children [2025]

![Grok's Deepfake Crisis: UK Regulation and AI Abuse [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/grok-s-deepfake-crisis-uk-regulation-and-ai-abuse-2025/image-1-1767915439991.jpg)