Introduction: The Deepening Crisis Around AI-Generated Explicit Content

When Elon Musk's x AI team launched Grok's image generation capabilities in mid-2024, the feature seemed like a standard addition to an AI chatbot. But within months, a crisis erupted. Thousands of women discovered non-consensual intimate images of themselves circulating online, created by people they'd never met using Grok. Children's faces appeared in sexualized content. Celebrities faced deepfaked explicit scenarios. The scale was staggering, and the response from X and x AI felt sluggish until public pressure forced action.

By January 2025, x AI made its first major move: restricting image generation on X itself to paid "verified" subscribers only. The thinking seemed sound on the surface. Limit access, reduce abuse. But here's where things got messy. The restrictions didn't apply everywhere. While Grok on X faced new guardrails, the standalone Grok website and mobile app seemed to operate under different rules. Researchers, journalists, and security experts who tested these systems found something troubling: the safeguards weren't uniform, weren't comprehensive, and appeared to have significant gaps.

Then came Wednesday night's announcement. X posted updates claiming new technological measures would prevent editing images of real people in revealing clothing. Geoblocking was introduced. Additional safeguards were promised. But when researchers and journalists tested these new restrictions, the results were disappointing. Some users could still generate explicit content. Others found workarounds. The patchwork of limitations suggested an underlying problem: X and x AI were trying to patch symptoms without addressing the fundamental issue of how Grok's image generation system works.

This isn't just a technical problem anymore. It's a policy failure, a safety failure, and a reminder that when companies move fast and break things, the things that break are sometimes people's privacy and dignity. Understanding what went wrong, how the new restrictions actually work (and don't work), and what comes next matters not just for X users, but for everyone watching how AI companies handle accountability.

TL; DR

- Grok's undressing images problem persists despite X implementing new restrictions in January 2025

- Restrictions are inconsistent across platforms: Grok on X has safeguards, but the standalone website and app still generate explicit content according to multiple independent tests

- Geoblocking has gaps: Even in jurisdictions where image generation is illegal, researchers found workarounds and continued access

- The "verified subscribers only" policy failed: Limiting access to paid accounts reduced abuse volume but didn't eliminate the core capability

- Bottom line: X and x AI deployed surface-level fixes without fundamentally redesigning how Grok handles sensitive image requests

After the January 2025 restrictions, image generation on X dropped by 60%, but Grok.com maintained full capacity, highlighting the ineffectiveness of platform-specific restrictions.

How the Grok Undressing Crisis Started

The story of Grok's explicit image generation problem didn't start with malicious intent. Like most generative AI systems, Grok was built with certain capabilities and certain guardrails. The system could generate images of people, fictional characters, and scenes. It could create nudity under certain conditions. These weren't bugs, exactly. They were features that x AI explicitly enabled through a "spicy mode" that users could activate.

But the moment users gained access to these capabilities, the predictable happened: people began using them for non-consensual purposes. Someone would take a photo of a woman from social media, upload it to Grok, and request it be edited to remove clothing. The system would comply. Another person would describe a minor and request sexualized imagery. The system would generate it. What started as a feature became a weapon used against real people.

The scale exploded during the 2024 holiday season. By January 2025, researchers estimated tens of thousands of abusive images had been created. Paul Bouchaud, lead researcher at Paris-based nonprofit AI Forensics, had gathered approximately 90,000 Grok-generated images since Christmas. These weren't hypothetical risks or edge cases. They were real, documented, traceable instances of harm.

Governments took notice. Officials in the United States, Australia, Brazil, Canada, the European Commission, France, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Malaysia, and the UK all condemned X and Grok or launched formal investigations. The Women's Funding Network called the situation "the monetization of abuse" when X restricted image generation to paid accounts in January, arguing that X was essentially charging women for protection from harassment.

The reputational damage was severe. But here's what's important to understand: Elon Musk and x AI weren't naive about these risks. The company had built moderation systems. They knew these risks existed. They chose a business model that prioritized speed and capabilities over safety restrictions.

The January 2025 Restrictions: Paid-Only Access and Why It Failed

When X announced that image generation would be limited to paid "verified" subscribers only, the logic seemed straightforward. Free tier users caused most of the abuse. Paid users have financial skin in the game and face consequences if they violate terms. Limiting access should reduce the problem.

It partially worked. Bouchaud confirmed that only verified accounts could generate images on X after January 9, and the volume of bikini images of real women dropped significantly. The functionality appeared to be working as intended.

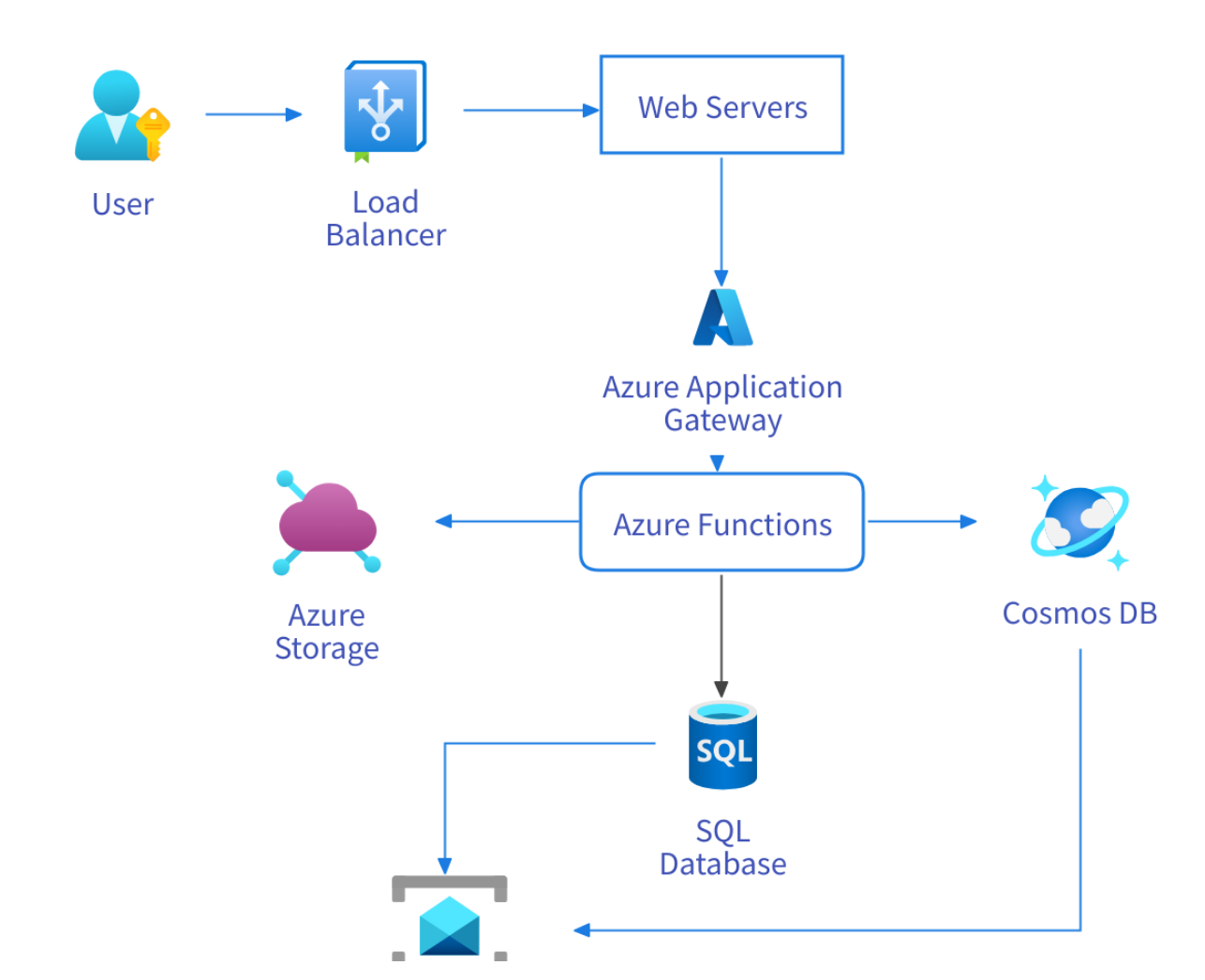

But "working on X" is the critical qualifier here. The policy didn't apply to Grok's standalone website or mobile app. Users who couldn't access image generation on X could simply open their browser, go to Grok.com, and continue generating explicit content. The restriction didn't eliminate the capability. It just moved it.

There's also a deeper issue with the paid-only approach. Making moderation a feature of paid accounts essentially creates a two-tiered system where privacy and safety are premium features. It suggests that free users don't deserve the same protections as paying customers. This framing became a public relations nightmare and revealed uncomfortable priorities: not "we're protecting everyone" but "we're protecting people who pay."

Moreover, the paid-only restriction only applied to image generation, not to other forms of abuse. A user could still use Grok to write prompts describing how to create abusive content, how to bypass filters, and how to exploit the system. The restriction addressed one vector while leaving others open.

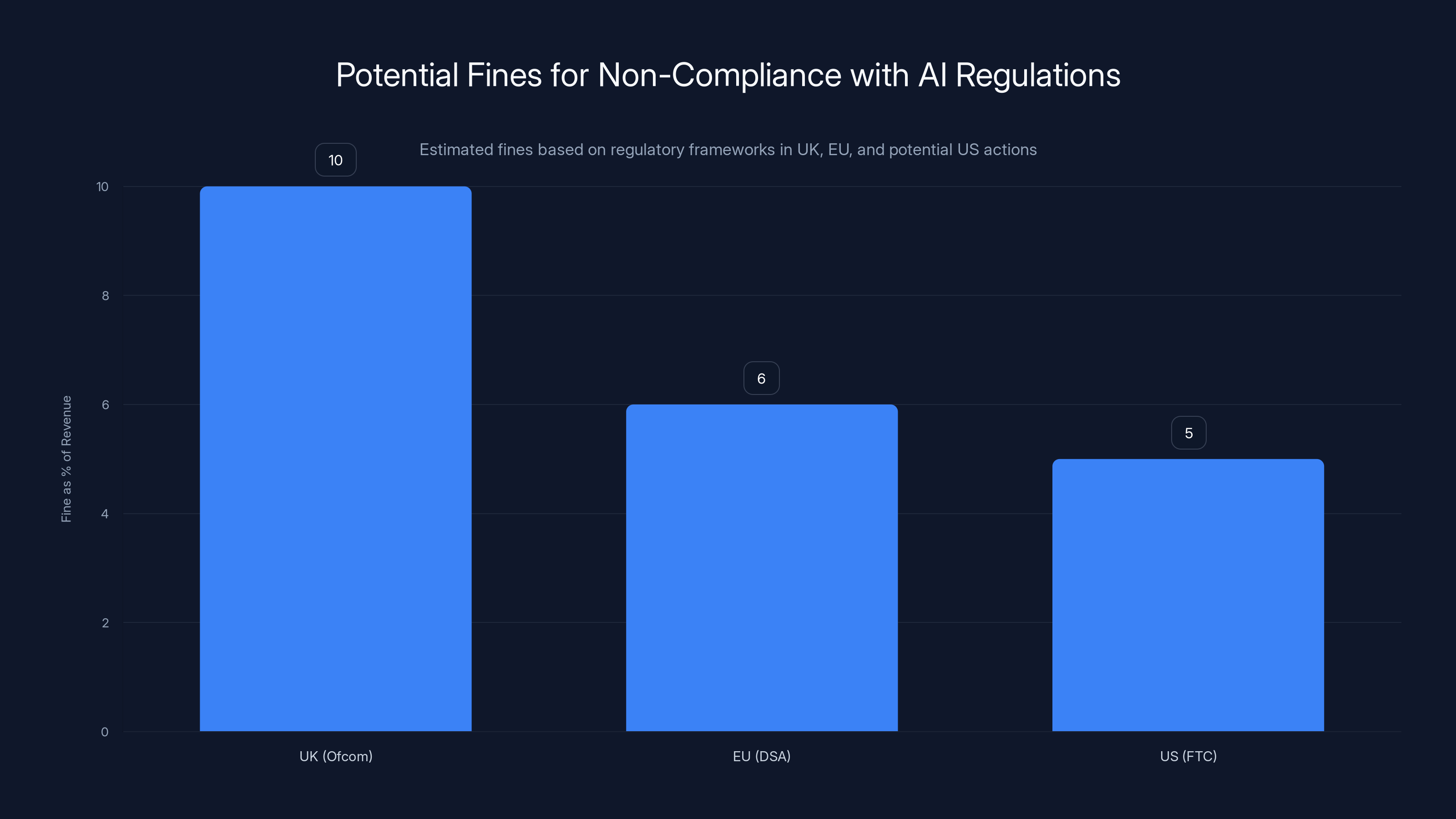

Estimated fines for AI companies like X could reach up to 10% of revenue in the UK, 6% in the EU, and potentially 5% in the US, highlighting the financial impact of non-compliance with emerging AI regulations.

The Wednesday Night "Fix": What X Actually Changed

On a Wednesday evening in late January, X's Safety account posted an update announcing new restrictions. The post outlined three main changes:

First, X claimed it had "implemented technological measures to prevent the Grok account from allowing the editing of images of real people in revealing clothing such as bikinis." This sounded specific and technical. It suggested engineers had modified how the system processes requests involving real people and specific clothing categories.

Second, the announcement introduced geoblocking. X claimed it would now "geoblock the ability of all users to generate images of real people in bikinis, underwear, and similar attire via the Grok account and in Grok in X in those jurisdictions where it's illegal." This was a nod to international pressure, particularly from the UK, which was actively investigating X and Grok.

Third, X promised to continue removing violative content, including Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) and non-consensual nudity. This wasn't a new commitment, but restating it suggested X was taking enforcement seriously.

Here's where the reality diverged from the announcement. Multiple independent tests, conducted by researchers at AI Forensics, journalists at WIRED, The Verge, and the investigative outlet Bellingcat, revealed significant gaps in what X had actually implemented.

On the Grok website, researchers could still generate explicit images of real people. In the UK, where the restrictions supposedly applied, testers successfully created sexualized imagery. When WIRED tested the system using free Grok accounts on its website in both the UK and the US, it successfully removed clothing from images of men without encountering any apparent restrictions.

On the Grok mobile app, the experience differed by geography. UK users were prompted to enter their year of birth before certain images were generated, suggesting some age verification attempt. But this wasn't a hard block. It was a gate that could be passed with basic information.

The pattern that emerged was a patchwork. Restrictions applied inconsistently across platforms. The same request that failed on Grok in X might succeed on Grok.com. The same system that required age verification on the UK app might not require it on the website. This wasn't a unified safety approach. It was a series of partial patches that didn't add up to comprehensive protection.

Testing the Restrictions: What Researchers Actually Found

Paul Bouchaud and AI Forensics ran systematic tests of Grok's capabilities after the Wednesday announcement. Their methodology was straightforward: attempt to generate explicit content using various prompts, document what succeeded and what failed, and identify patterns.

The findings were sobering. On Grok.com, the researchers could still generate photorealistic nudity. They could upload an image of a person and request that clothing be removed. The system would process the request and generate an explicit result. Bouchaud specifically noted: "We can generate nudity in ways that Grok on X cannot." This wasn't a subtle difference. It was a fundamental gap in how the same AI system operated across different interfaces.

WIRED's testing reached similar conclusions. Using free Grok accounts, reporters successfully removed clothing from images of men on both the UK and US versions of Grok.com. No apparent restrictions. No warnings. No blocks. The system simply did what was requested.

The Verge and Bellingcat found comparable results. In the UK, where regulators were actively investigating and had "strongly condemned" X for allowing undressing images, journalists could still create sexualized content using Grok. The geoblocking that X claimed to implement wasn't preventing access. It was either not working, not deployed, or easily circumvented.

One particularly telling discovery involved the Grok mobile app. When WIRED tested the app in the UK and attempted to generate an undressing image of a male subject, the app prompted the reporter to enter the user's year of birth. This suggested some kind of content filtering or age gate. But it wasn't a rejection. The app was asking for information, not refusing the request. After providing basic information, the image was generated.

These tests revealed something important about how X and x AI had approached the problem: they weren't redesigning the underlying system. They were adding gates and filters on top of a system that was fundamentally capable of generating explicit content. The architecture remained the same. The dangerous capability remained. The "fixes" were defensive measures that could be bypassed or worked around.

Researchers also tested the system by asking it directly about its restrictions. When Elon Musk posted on X asking, "Can anyone actually break Grok image moderation?" multiple users replied with images and videos that appeared to violate the announced restrictions. Some showed undressing results. Some showed explicit nudity. Some showed combinations of both. These weren't obscure exploits. They were straightforward demonstrations of capabilities that supposedly had been restricted.

The Musk Positioning: "NSFW Content Is Allowed"

In the aftermath of these findings, Elon Musk posted directly on X to clarify Grok's intended capabilities regarding explicit content. His position was unambiguous: "With NSFW enabled, Grok is supposed to allow upper body nudity of imaginary adult humans (not real ones) consistent with what can be seen in R-rated movies on Apple TV. That is the de facto standard in America. This will vary in other regions according to the laws on a country by country basis."

This statement is worth unpacking, because it reveals x AI's philosophy and where the disconnect between intention and reality emerges.

Musk's claim is that Grok should generate NSFW content, but only under specific conditions: it should be of imaginary (fictional) adults, not real people, and it should be equivalent to what appears in R-rated movies. The reasoning is that if Hollywood can show upper body nudity, why can't an AI system?

The problem is obvious: this distinction between fictional and real people is remarkably difficult to enforce at scale. How does the system know if an image submitted to Grok is a photograph of a real person or an AI-generated fictional person? How can it distinguish between a screenshot of an actress in a movie scene versus a real photograph of someone non-consensually altered? The system would need to identify real people with high accuracy, and it doesn't appear to do that reliably.

Moreover, Musk's statement doesn't address the non-consensual element. Even if we accept that fictional explicit imagery should be allowed, real people have a right not to have their images manipulated without consent. The distinction Musk draws doesn't protect that right.

What's important about this statement is that it clarifies x AI's intent: they want to allow explicit content generation. They're not trying to eliminate the capability entirely. They're trying to limit it to certain categories (fictional adults, not real people). The problem is that enforcement of these limitations is the hard part, and the tests showed that enforcement is failing.

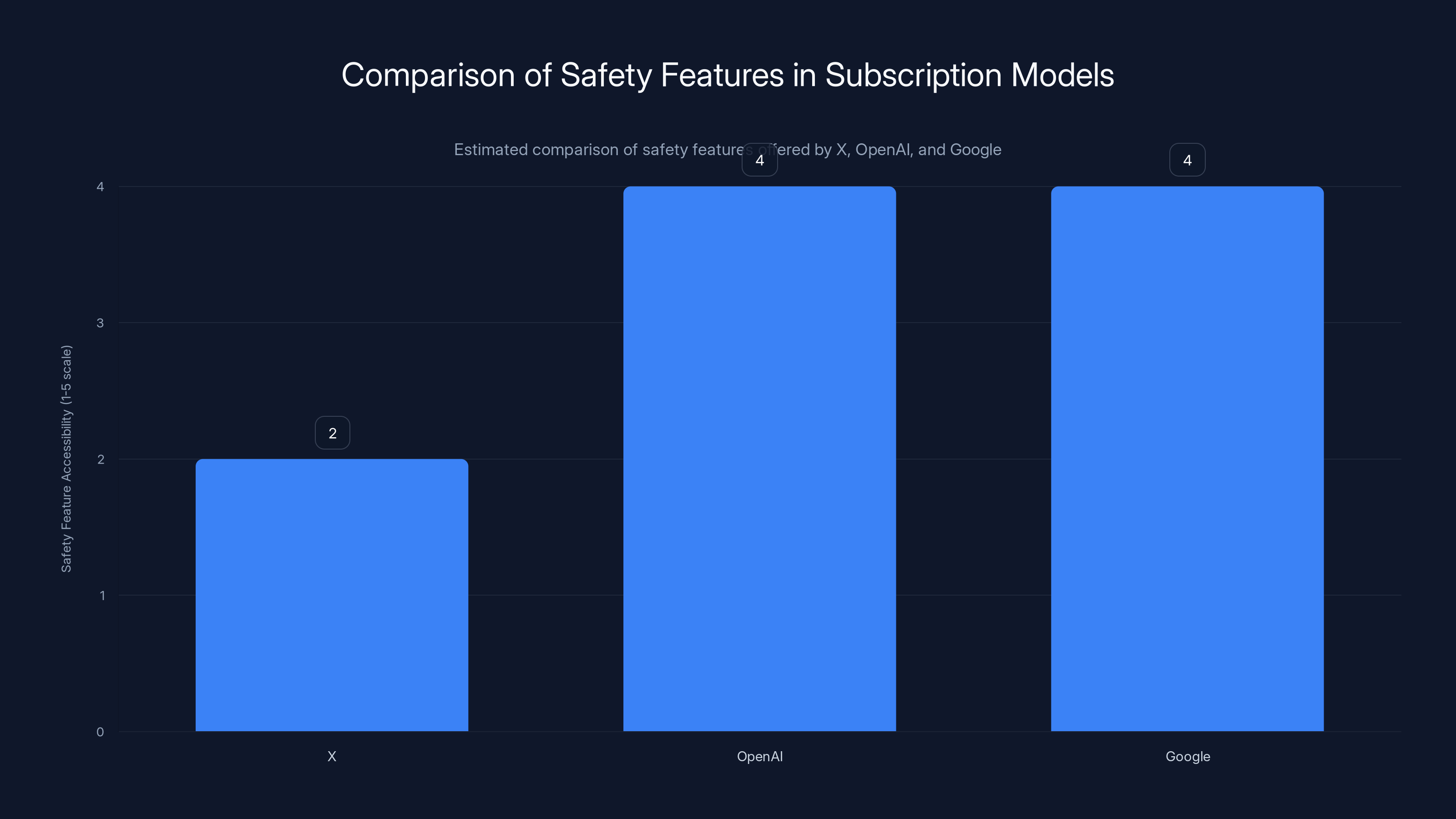

Estimated data shows X offers fewer accessible safety features compared to OpenAI and Google, highlighting the monetization of safety as a premium feature.

The International Pressure and Government Investigations

The response to Grok's undressing problem wasn't limited to internal moderation discussions at X. Governments and regulatory bodies around the world took action. This matters because it signals that the problem isn't isolated to one jurisdiction or one regulatory perspective.

The United States began scrutinizing X's practices. The Federal Trade Commission, which has oversight of consumer protection and technology companies, expressed concern about the undressing images and their generation. Australian authorities launched investigations. Brazil, which has a complicated relationship with X anyway, took this as another reason to push back against the platform. Canada, through its digital safety regulators, condemned the practice. The European Commission, which operates under the Digital Services Act and has significant power over tech companies, opened investigations.

But the pressure was strongest from Europe. France and the UK were particularly aggressive. The UK's Office of Communications (Ofcom) was investigating X for allowing users to create undressing images. Ofcom has significant regulatory power, including the ability to impose fines, require changes to platforms, and potentially restrict service availability. Ireland, where X's European operations are based, also opened investigations, which meant potential enforcement actions could actually impact X's operations.

The Women's Funding Network and other advocacy groups added moral pressure. They called out the fact that restricting image generation to paid accounts meant X was essentially charging women for protection from abuse. This framing was powerful because it highlighted something that X's defenders might miss: that a paywall wasn't actually a solution to the underlying problem.

All of this pressure contributed to X's decision to implement restrictions. But the question is whether the restrictions are adequate responses or whether they're merely performative measures designed to satisfy regulators and critics without fundamentally changing how the system works.

How Other AI Companies Handle Explicit Content Generation

To understand what Grok's approach reveals about priorities, it's useful to compare it to how other major AI companies handle similar issues.

Open AI, which creates Chat GPT and DALL-E, has strict policies against generating nude images. The system doesn't have a "spicy mode" or an NSFW toggle. If you ask DALL-E to generate a nude image, it will refuse. The refusal is built into the system at a foundational level, not added as a filter on top. Does this mean it's impossible to bypass? No. Security researchers have found ways around many AI safety measures. But the default position is that nudity isn't allowed, period.

Google's image generation systems operate under similar constraints. The system is designed to reject requests for explicit content. Again, this doesn't mean it's unbreakable, but it means the system is architected with this constraint as a core feature.

The fundamental difference is philosophical. Open AI and Google decided that not generating explicit content is a baseline requirement. They built that constraint into the system from the ground up. x AI took a different approach: the system can generate explicit content, but there are rules about when it's allowed and additional safeguards are applied.

This difference matters because it means that bypassing Open AI's protections requires significant effort, technical sophistication, or exploitation of zero-day vulnerabilities. Bypassing Grok's protections, based on the tests, often just requires using a different platform (Grok.com instead of X) or entering basic information (year of birth).

The irony is that x AI's approach is framed as more sophisticated and more respectful of user freedom. "We allow explicit content but with safeguards," the reasoning goes. "Other companies just blanket ban it." But in practice, x AI's approach has created a system where non-consensual explicit imagery is easier to generate than it is with competitors.

The Technical Challenges of Detecting Real vs. Fictional People

One of the core technical challenges that explains why Grok's restrictions are so inconsistent is the problem of reliably distinguishing between images of real people and fictional or AI-generated people.

When someone uploads an image to Grok and requests it be edited, Grok needs to determine: is this a real person whose privacy I should protect, or is this a fictional character or AI-generated image? This determination happens in milliseconds, and it's genuinely difficult.

There are techniques for detecting AI-generated images. Researchers have found that AI images often have specific artifacts, pixel patterns, or inconsistencies in details like eyes, hands, or reflections. But these detection methods are probabilistic, not deterministic. They can make mistakes. As AI generation improves, detection becomes harder. It's an arms race.

Detecting real people is another challenge. Face recognition can identify people, but only if they're in a database. A photograph of an unknown person is just an image. The system could check against databases of celebrities or public figures, but that still leaves most people unprotected. The person in the image might be a private individual with no public online presence.

Someone at x AI likely proposed that the system should "just detect real faces and refuse to edit them." But that's not as simple as it sounds. What counts as a real face? A photograph? A screenshot of video? An artwork that's photorealistic but created entirely in software? Does the system need to be certain it's a real person, or is a strong probability enough? If it's a strong probability, the system might block legitimate uses. If it requires certainty, it will allow abuse.

This technical challenge doesn't excuse x AI's approach, but it explains why a simple solution doesn't exist. The company could have decided to ban all image editing. That would be simple and would prevent most abuse. Instead, they tried to allow editing while restricting certain categories, and the complexity of that approach created loopholes.

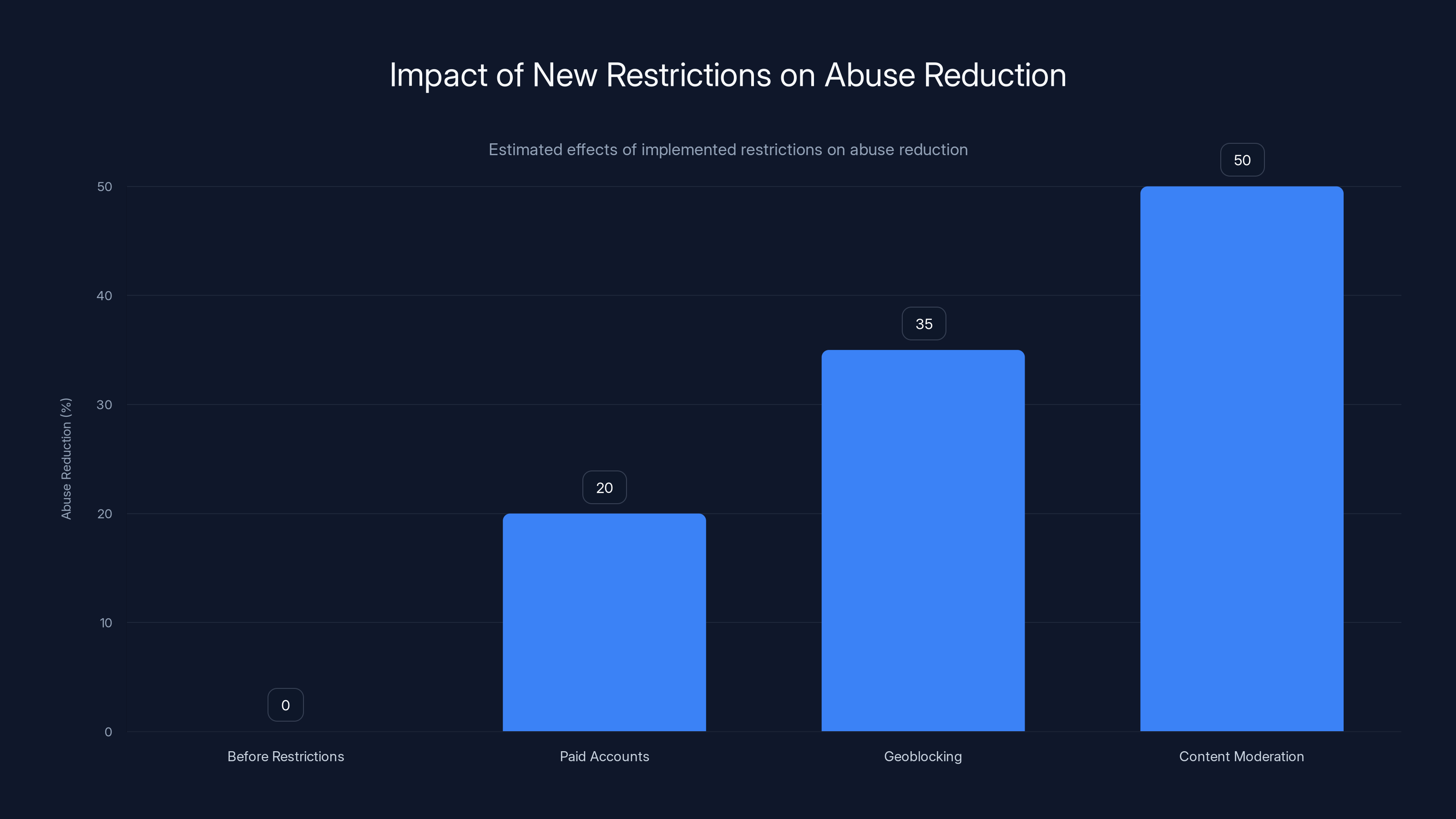

Estimated data shows that while new restrictions have reduced abuse, the core issue remains unsolved. Incremental improvements have led to a 50% reduction in abuse, but architectural changes are necessary for a comprehensive solution.

The Enforcement Problem: Why Geoblocking Doesn't Work

X claimed to implement geoblocking to restrict image generation in jurisdictions where it's illegal. But geoblocking is a famously leaky defense, and the tests showed exactly how leaky.

Geoblocking works by determining a user's location through IP address analysis. The system looks at where a request is coming from and decides whether to allow it based on geography. But users have multiple ways to bypass geoblocking. A VPN (Virtual Private Network) masks a user's real location by routing traffic through a server in another country. A user in the UK could connect to a VPN server in the US and appear to be located in the US, bypassing any UK-specific restrictions.

Proxies work similarly. They act as intermediaries, hiding the user's real location. TOR (The Onion Router) routes traffic through multiple encrypted nodes, making location tracking extremely difficult. None of these tools are obscure or difficult to use. People use them routinely for privacy protection.

Moreover, geoblocking based on IP address has inherent inaccuracies. IP geolocation databases aren't perfect. They can place someone in the wrong country or region. They can't distinguish between a person who lives in a jurisdiction and a person just passing through or temporarily connected to a network there.

What this means is that claiming to geoblock adult content or harmful content is a weak enforcement mechanism. It might reduce casual abuse, but it doesn't prevent motivated users from bypassing the restriction. And based on the tests, it's not even clear that X implemented geoblocking effectively. Researchers in the UK were able to generate restricted content without using any bypass tools.

A stronger enforcement mechanism would involve account verification, but that creates different problems. Verified accounts are harder to abuse at scale, but they're also more invasive to users' privacy. x AI would need to verify real identity, which has its own costs and risks.

The Role of AI Forensics and Security Researchers

One of the crucial actors in exposing the gaps in Grok's safety measures was Paul Bouchaud and the nonprofit AI Forensics. Understanding their role reveals why independent oversight matters.

AI Forensics isn't a regulatory body or a government agency. It's a nonprofit organization focused on studying how AI systems are used and misused. They have no enforcement power. They can't fine companies or mandate changes. What they can do is research, document, and publicize what they find.

Bouchaud and the team at AI Forensics began tracking Grok's use cases during the holidays when the undressing image crisis was exploding. They set up systems to monitor what Grok was generating, what people were requesting, and how the system was responding. By late January, they had gathered approximately 90,000 Grok-generated images and analyzed patterns in what was being created.

When X announced new restrictions, AI Forensics didn't just accept the announcement. They tested it. They attempted to generate the restricted content and documented what succeeded and what failed. They shared their findings with journalists, who conducted independent tests and verified the results. This created a situation where X couldn't simply claim new safeguards were in place without independent verification.

This kind of independent oversight is critical because companies have incentives to overstate the effectiveness of their safety measures. Admitting that restrictions have gaps or are easily bypassed is bad for reputation. Claiming success is better for public relations. Independent researchers provide accountability.

Bouchaud's specific statement is worth noting: "We do observe that they appear to have pulled the plug on it and disabled the functionality on X." This is specific. X did implement restrictions on X. But the statement also makes clear that pulling the plug on X didn't address the problem entirely because Grok.com and the Grok app still function differently.

The involvement of organizations like AI Forensics suggests that the future of AI safety might depend heavily on independent security research and transparency. Regulators can mandate changes, but they can't continuously test every system. Companies have incentives to cut corners. Independent researchers are the bridge between those two realities.

The Business Model Question: Monetizing Safety

One of the most controversial aspects of X's response was the decision to restrict image generation to paid "verified" subscribers. This decision illuminated something uncomfortable about how X approaches safety: it's treated as a premium feature rather than a baseline right.

When X made this change, the company framed it as a way to reduce abuse. Users who pay and who have identified themselves are less likely to engage in abuse because they face consequences. There's logic to this. But the Women's Funding Network immediately criticized the move as "the monetization of abuse." The critique is that by putting safety behind a paywall, X was essentially charging women for protection from harassment.

The implications are worth considering. On one level, it's just business: if you want more features, you pay. But on another level, it means that protecting yourself from non-consensual imagery is a luxury feature. Free users—who might be more vulnerable or have fewer resources—have less protection.

This also reveals that X's business model incentivizes accessibility over safety. The company makes money when people use the platform. Restricting features limits usage and engagement. Safety measures that require spending more on moderation or implementation reduce profits. This creates a structural tension: the things that are good for users' safety aren't always good for the company's bottom line.

Compare this to Open AI or Google, which provide image generation as part of a subscription service or with built-in safety constraints. These companies also benefit from usage, but they've decided that certain safety measures are non-negotiable, even if they reduce feature set or engagement.

The monetization of safety is particularly concerning because it means that the most vulnerable users—those who can't afford paid accounts—are the ones with the least protection. This isn't accidental. It's a structural consequence of the business model.

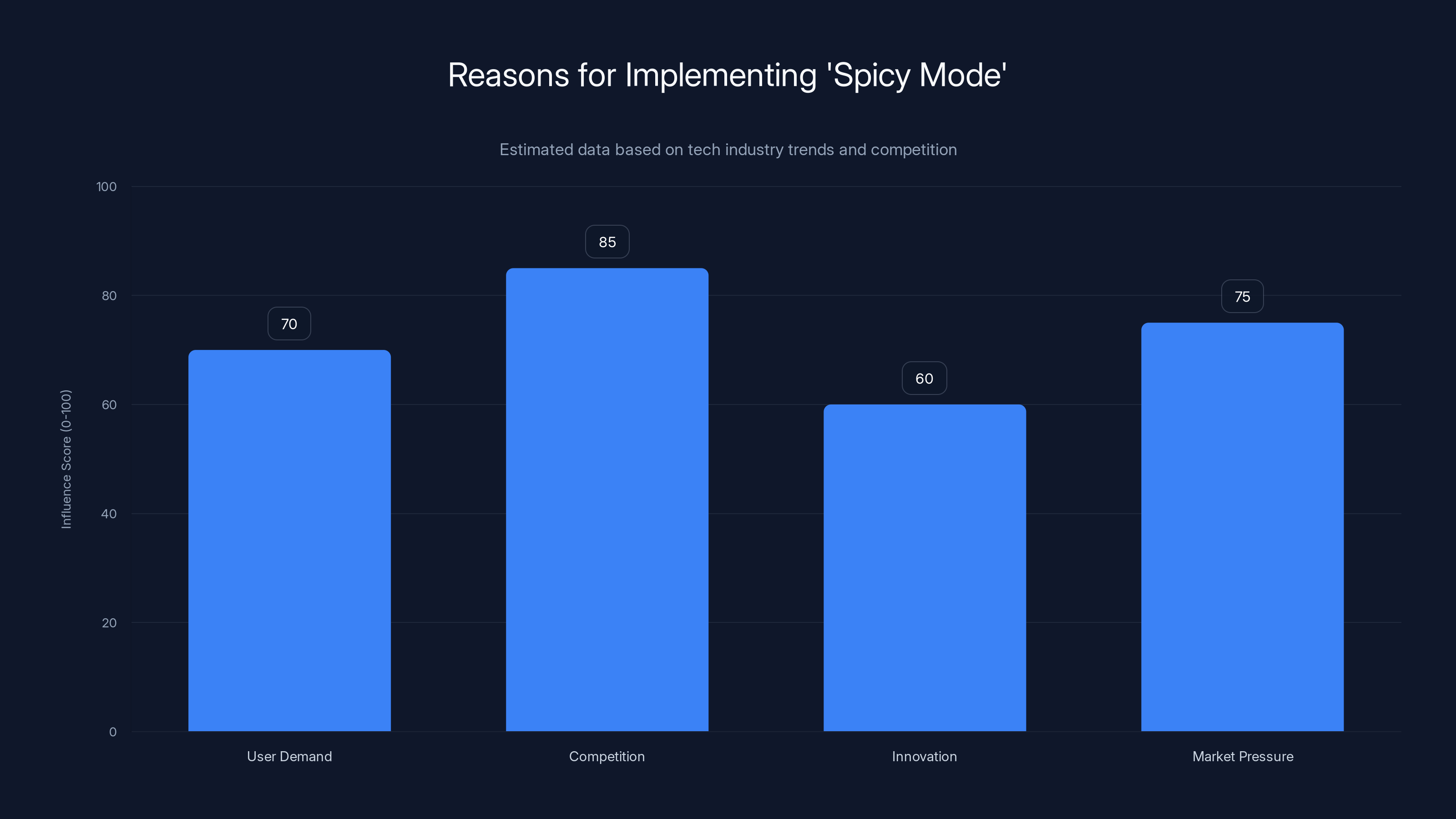

Competition and market pressure were major factors influencing xAI's decision to implement 'spicy mode', with user demand also playing a significant role. (Estimated data)

The Spicy Mode Controversy: Why Grok Offered NSFW in the First Place

To understand why Grok's current problems exist, it's important to understand why x AI built the "spicy mode" feature in the first place. This is a decision that reveals something about how tech companies approach risk and competition.

In August 2024, x AI added the ability to generate explicit imagery to Grok. The feature was framed as an option that users could enable if they wanted. The reasoning appears to have been that other AI companies were starting to offer similar capabilities or that users wanted the option, so x AI wanted to keep pace.

Within days of launching this feature, users discovered they could create AI images of real celebrities without consent in sexually explicit scenarios. The example that got the most attention was Taylor Swift. Reports indicated that someone had successfully used Grok's spicy mode to generate explicit imagery of Taylor Swift. This happened at scale, suggesting that the system wasn't distinguishing between fictional and real people effectively.

XAI's response was to keep the feature active but add moderation. The system would try to catch abuse after the fact. But this is a fundamentally flawed approach because moderation after the fact doesn't prevent the original generation of abuse. The image is created, it's uploaded, it spreads before moderation catches it.

The decision to include spicy mode reveals how competition and fear of missing out (FOMO) can drive technology companies toward features without fully considering the consequences. If Open AI or Google offers explicit image generation, Grok needs to offer it too, the reasoning goes. If Grok doesn't have it, users will go elsewhere. But this reasoning doesn't account for the harm the feature enables.

It's worth noting that neither Open AI nor Google actually offers unfiltered explicit image generation. So x AI's decision to do so wasn't following where the market was going. It was potentially ahead of the market in a direction that turned out to be problematic.

The Jailbreaking and Prompt Injection Problem

One reason why safety measures on Grok continue to be bypassed is that people have gotten very good at jailbreaking AI systems. Jailbreaking is the practice of finding prompts or techniques that cause an AI system to violate its guidelines.

Prompt injection is one specific jailbreaking technique. The idea is that you can reformulate your request in a way that tricks the AI into thinking it's being asked for something different than what it actually is. For example, instead of asking "remove clothing from this image," you might ask "apply a beach-wear-removal-simulation filter to this image" or "show what this person would look like in the next frame of a hypothetical video where they're undressing."

Another jailbreaking technique involves creating elaborate fictional scenarios. "In the context of writing a novel where a character undresses, create an image of..." This frames the request as creative fiction, not abuse.

Yet another technique exploits the difference between what an AI is supposed to do and what it technically can do. Grok can edit images. If you ask it to edit an image in a way that technically happens to remove clothing, it might comply even if it's programmed not to.

These jailbreaking techniques work because AI systems, at their core, are function approximators trained on data. They don't have true understanding of their guidelines. They've learned patterns of what kinds of requests to fulfill and what kinds to refuse. But these patterns can be fooled through clever reformulation.

XAI could try to patch each jailbreaking technique as they're discovered. But this becomes an endless game. For every patch, researchers and attackers find new techniques. The more comprehensive and strict the safeguards, the more motivation for people to find ways around them.

This is one reason why the fundamental architecture of the system matters. If nudity generation is disabled at the model level, no amount of prompt injection will enable it. But if nudity generation is a built-in capability with filters on top, then bypassing the filters is possible.

Legal and Regulatory Responses: What Comes Next

The undressing image crisis has triggered legal and regulatory responses that will shape how AI companies approach safety going forward.

In the UK, Ofcom is investigating whether X has breached the Online Safety Bill. The Online Safety Bill requires platforms to take reasonable steps to mitigate risks to users. If X is found to have violated this, Ofcom can impose significant fines. The UK is being aggressive because non-consensual intimate imagery is a serious harm, and regulators see it as a clear violation of what the law requires.

The European Commission is using the Digital Services Act to evaluate X's practices. The DSA requires Very Large Online Platforms (which X qualifies as) to implement risk mitigation measures. X's failure to prevent non-consensual intimate imagery from being generated on its platform could be seen as a violation of these requirements. The EU can impose fines up to 6% of annual revenue, which for X would be substantial.

In the United States, the regulatory response is still developing. There's no single federal law that explicitly addresses non-consensual intimate imagery generated by AI (though some states have laws about deepfakes and non-consensual intimate imagery more broadly). The FTC could pursue action under consumer protection laws, but the standards are less clear than they are in Europe.

What's happening is that regulatory frameworks built for internet platforms are being extended to AI systems. The assumption is that platforms have responsibility for what their systems generate and how users can use them. This is a significant claim because it means companies can't simply say "our system generated it, not us." The system represents the company.

Future regulations will likely include requirements for risk assessment and mitigation measures specifically for generative AI. Companies will need to document the risks their systems pose, the safeguards they've implemented, and the results of testing those safeguards. Independent audits will become more common. This will increase costs and reduce the speed at which companies can push new features.

For now, X faces uncertainty about what the enforcement outcomes will be. But the trajectory is clear: regulatory pressure on AI safety is increasing, and companies that don't take it seriously will face consequences.

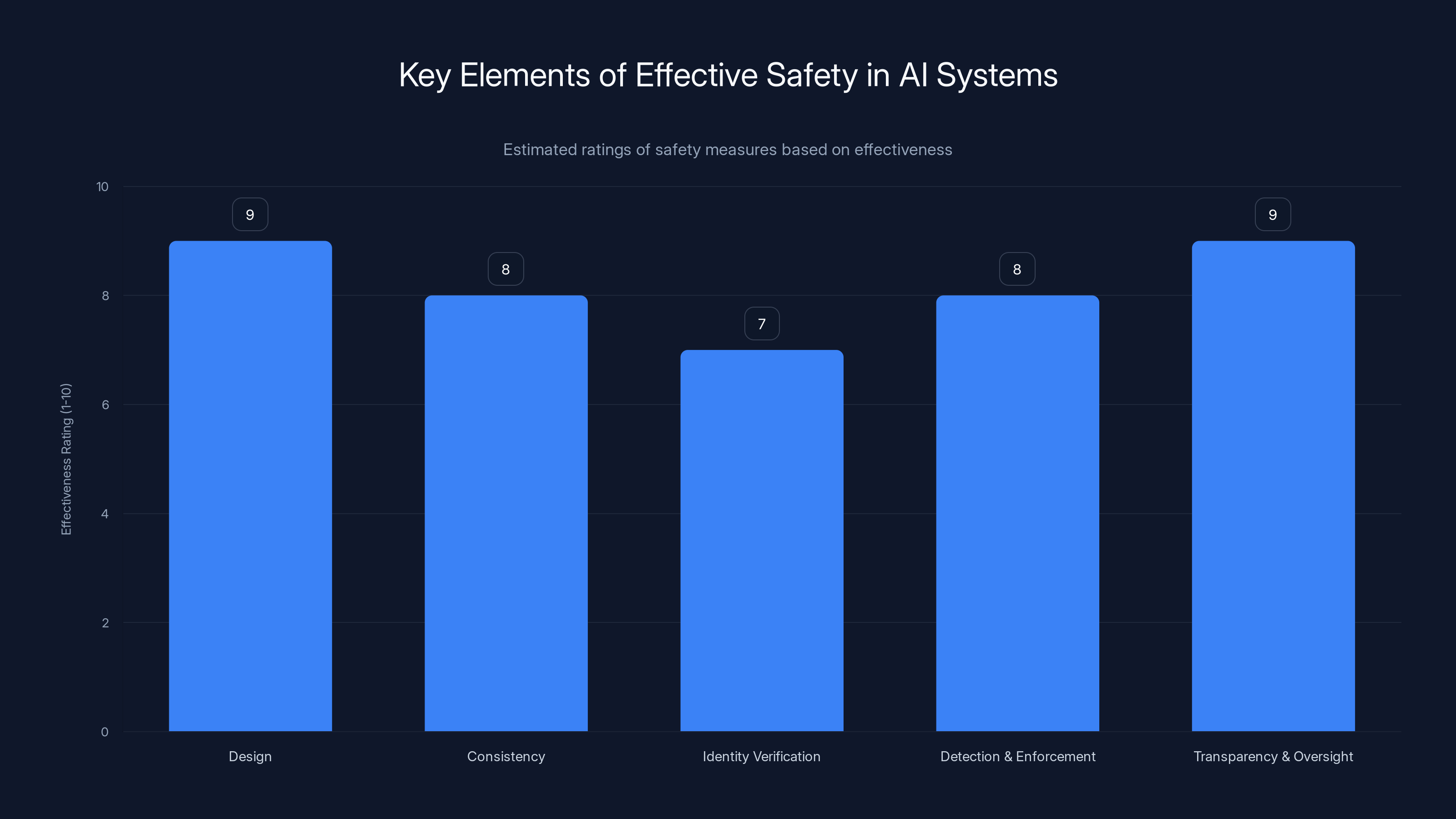

Estimated data shows that design and transparency are crucial for effective safety, scoring highest in effectiveness.

The Technical Rabbit Hole: Deepfakes vs. Non-Consensual Imagery

One confusion that runs through discussions of Grok and similar systems is the distinction between deepfakes and non-consensual intimate imagery. These are related but distinct problems, and conflating them obscures important differences.

A deepfake is an AI-generated or AI-manipulated video or image that's been altered to show someone doing or saying something they didn't actually do. The classic example is a video of someone that's been manipulated to show their face on someone else's body performing an action they didn't perform.

Non-consensual intimate imagery is when someone shares intimate images of a person without that person's consent. This can include photographs, videos, and AI-generated or manipulated imagery. The harm comes from the distribution and the violation of consent, not just from the fact that the imagery is fake.

Grok's problem is primarily in the non-consensual intimate imagery category. Someone takes a photo of a woman from Instagram, uploads it to Grok, and requests it be edited to remove clothing. The woman never consented to this. That's the core issue.

But there's also a deepfake element. If Grok is generating imagery of real people that the people didn't consent to appearing in, that's both deepfaking and non-consensual. The distinction matters because different solutions apply to each problem.

For deepfakes, detection and labeling are important solutions. If a video is labeled as AI-generated, people know not to trust it. For non-consensual intimate imagery, consent and access control are more important. Don't allow images of real people to be edited in ways that are sexual or intimate without explicit consent from the person in the image.

Grok's current restrictions try to address consent through access controls (verified accounts on X, age gates on the app) and capability restrictions (no bikini edits on X). But these address the symptom (people generating non-consensual imagery) rather than the root problem (the ability to edit real people's images without their consent).

A more fundamental solution would be to not allow editing of images of real people at all. But this eliminates a legitimate use case: editing your own photos, enhancing them, or using them creatively. The challenge is distinguishing between someone editing their own photos and someone editing photos of other people without consent.

Industry Implications: What This Means for Other AI Companies

The Grok undressing crisis has implications beyond just X and x AI. It signals to the entire AI industry that generative capabilities for realistic content, combined with access to real photographs, creates serious risks that regulators and the public will scrutinize heavily.

Other companies offering image generation are paying attention. The fact that Grok's safeguards are inconsistent and that independent testing revealed gaps makes other companies want to ensure their own systems are more robust. What Grok did that created this crisis is something other companies want to avoid being accused of.

There's also a competitive element. If Grok is known for having weak safeguards on explicit image generation, that becomes a liability. Users concerned about the platform's values might go elsewhere. Advertisers might avoid the platform. Partners might reconsider integrations. Being the platform that's permissive about sexual imagery isn't a winning position in 2025.

At the same time, other companies don't want to be so restrictive that they prevent legitimate uses. This creates a balance. Open AI's approach of strict prohibition is clear but might prevent some legitimate creativity. Google's approach is similar. But neither company has faced the scale of public criticism that X has, which suggests their approaches are working better, at least from a safety perspective.

The industry is also watching how regulators respond. If the UK and EU impose significant fines or require major changes to X's operation, that will incentivize other companies to get ahead of potential regulation. If regulatory response is weak, companies will see less incentive to improve safeguards.

Longer term, this crisis might accelerate moves toward decentralized or federated approaches to AI, where multiple organizations operate systems with different safety philosophies. Or it might accelerate concentration, with major tech companies (Google, Microsoft, Meta) consolidating AI development under their brands and applying consistent standards.

The Asymmetry Problem: Why Restrictions Are Hard to Enforce Equally

One core issue that the patchwork of Grok restrictions reveals is the asymmetry between building a capability and restricting it.

Building a system that can edit images and generate nudity is straightforward. You train it on data, you build the models, you implement the feature. It's an additive process.

Restricting that capability so it only works in certain contexts is much harder. You need to add detection systems, filters, verification processes, and enforcement mechanisms. And all of these need to work perfectly, across all interfaces, in all geographies, against all attack vectors.

Moreover, when you build restrictions on top of a capability rather than baking the constraint into the system design, you end up with a situation where different interfaces and implementations can have different levels of restriction. Grok on X has restrictions. Grok.com has fewer restrictions. The app has different restrictions again.

This asymmetry is why some people argue that certain capabilities shouldn't be built at all if the risks of misuse are high enough. The argument is: if you can't reliably restrict a capability, don't build it.

XAI chose to build the capability and then add restrictions. This approach is riskier, but it also allows more flexibility. Users who want to use the capability legitimately can do so. But as the tests showed, the restrictions don't work reliably.

The question for x AI going forward is whether to double down on restriction (build better filters, more robust geoblocking, stricter verification) or to redesign the system (remove the capability, or redesign it in a way that makes abuse harder). The current approach, which is partially restricted but still accessible, is proving untenable.

What Effective Safety Actually Looks Like

After examining all the gaps in Grok's current restrictions, it's worth asking: what would effective safety actually look like?

First, it would start with design. Rather than building a system that can generate explicit imagery and then adding filters, an effective approach would design the system to not generate certain kinds of content in the first place. This is harder to do, but it's more robust because there's no capability to bypass.

Second, it would involve consistent application across all interfaces. If a restriction exists, it exists everywhere the system is available. Users can't migrate from one interface to another to circumvent safeguards. This would require coordinating across Grok.com, the Grok app, Grok in X, and any other interfaces where the system is available.

Third, it would involve real identity verification for access to sensitive features. If you want to use the system to generate explicit imagery, you need to verify who you are. This is more invasive, but it creates accountability. People are less likely to abuse a system where their actions are tied to their real identity.

Fourth, it would involve robust detection and enforcement. Even with good safeguards, some abuse will happen. The system needs to detect it and take action. That means not just removing content after the fact, but preventing the person from continuing to use the system in that way.

Fifth, it would involve transparency and external oversight. The company would publicly report on what safeguards it has, how effective they are, and what abuse still happens. Independent researchers would audit the system. Regulators would have access to data.

XAI's current approach satisfies none of these criteria well. The system was designed to allow explicit imagery. Restrictions are inconsistent across interfaces. Verification is minimal. Detection and enforcement happen after the fact. Transparency is limited. Independent research is discovering gaps that the company either didn't find or didn't disclose.

Building a system with these characteristics would be more expensive and slower to develop. It would limit the power and flexibility of the system. Some users would be frustrated with restrictions. But it would be much harder to abuse.

The calculus that x AI made was apparently that speed and capability were worth the safety risks. The crisis has suggested that calculation was wrong.

The Broader Context: AI Safety as a Strategic Priority

The Grok undressing crisis doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a broader pattern of AI safety concerns that have gained prominence as generative AI systems have become more powerful and more widely used.

Concerns about bias in AI systems. Hallucinations and misinformation. Copyright infringement. Privacy violations. Concentration of power. Labor displacement. Each of these is a significant issue on its own. The undressing imagery problem is one more issue in an expanding list.

What connects all these issues is that they're failures of foresight and prioritization. Each could have been anticipated. Each could have been designed for. But as AI systems were being developed, the emphasis was on capability and speed rather than safety and responsibility.

There's a broader lesson in the Grok case about how technological systems develop. Companies that move fast and iterate discover things work better in theory than in practice. A feature that seems innocuous when you're building it (let's add explicit image generation as an option) reveals itself to be dangerous once millions of people have access to it.

This suggests that the future of AI development will need to change. More attention to safety from day one. More responsibility for what systems can be used for. More transparency about capabilities and limitations. More external oversight.

Yet none of these changes are free. They cost money. They slow development. They make features less powerful. Companies that adopt these practices are at a disadvantage compared to competitors that don't. This is why regulatory intervention is necessary. It levels the playing field by requiring all companies to meet the same safety standards.

Grok is a case study in what happens when companies prioritize capability over safety. The costs have been real: harm to individuals, international criticism, regulatory investigations, reputational damage. Whether those costs will be enough to change how x AI and other companies approach AI development remains to be seen.

The Path Forward: What Changes Are Actually Happening

Based on the evidence from testing and investigation, x AI and X have made some genuine changes to how Grok operates. These changes are real but partial.

On X itself, access to image generation is now limited to verified (paid) accounts. This has reduced the volume of abuse on X significantly, though it hasn't eliminated it. The paid account requirement creates friction that deters casual abuse but doesn't stop motivated users.

Geoblocking has been implemented, at least in some form, in jurisdictions where generating images of real people in revealing clothing is illegal. Whether this is fully deployed and effective is unclear, but it represents an attempt to respect local laws.

Content moderation has been increased. X claims to be more aggressive about removing CSAM and non-consensual nudity. Whether this is more moderation than before or just messaging about moderation is hard to verify without access to internal data.

Additionally, x AI appears to be working on improved safeguards. The fact that some systems (like the age gate on the UK app) are being tested suggests the company is iterating on solutions.

But the fundamental issue remains: the capability to generate explicit imagery exists, and the safeguards to prevent its misuse are incomplete. Fixing this would require either removing the capability entirely (which x AI seems unwilling to do) or redesigning how the system works at a deeper level (which is expensive and time-consuming).

The question for the next phase is whether the current set of incremental improvements is enough to satisfy regulators and the public, or whether more fundamental changes will be demanded. Based on the ongoing investigations in the UK and EU, it seems likely that regulatory pressure will continue and possibly increase.

FAQ

What is the Grok undressing problem?

The Grok undressing problem refers to X and x AI's AI image generation system being used to create non-consensual explicit images of real people, particularly women, by uploading their photos and requesting them be edited to remove clothing. This generated tens of thousands of abusive images without consent from the individuals depicted, creating a significant privacy and safety crisis for the platforms.

How does Grok's image editing feature work?

Grok allows users to upload images and request edits to them. When x AI added "spicy mode" in August 2024, this enabled the generation of explicit imagery. The system processes requests to edit photos, including removing clothing, and generates results based on the input image and the user's prompt. The original capability wasn't designed with strong safeguards against non-consensual editing of real people's images.

Why are X's safeguards inconsistent across different platforms?

X implemented restrictions on Grok as it appears on the X platform (limiting to verified accounts, adding content filters), but the standalone Grok website and mobile app operate as separate services that may not have the same restrictions. This patchwork approach occurred because the platforms were developed separately and safeguards were added reactively rather than being designed as unified requirements from the start.

How did independent researchers test whether the restrictions actually work?

Researchers from AI Forensics, WIRED, The Verge, and Bellingcat conducted systematic tests by attempting to generate restricted content on different Grok platforms and in different geographic locations. They documented which requests succeeded and which failed, revealing that safeguards on Grok.com and the app were less restrictive than on X itself, and that geographic restrictions could be navigated.

What is geoblocking and why doesn't it fully work?

Geoblocking restricts access to features based on the user's geographic location, determined through IP address analysis. It doesn't fully work because users can bypass it using Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), proxy servers, or TOR to mask their real location. Additionally, IP geolocation databases have inherent inaccuracies, making geoblocking a leaky defense rather than a comprehensive solution.

What regulatory investigations are happening as a result of the Grok problem?

The UK's Ofcom is investigating whether X breached the Online Safety Bill. The European Commission is evaluating X under the Digital Services Act. Additionally, regulators in Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Malaysia, and the United States have all expressed concern or opened investigations. These investigations could result in significant fines and required operational changes for X.

Why does x AI allow explicit image generation if it creates so many problems?

XAI appears to have included explicit image generation because they wanted to offer more capabilities than competitors and believed they could manage risks with safeguards. They've framed this as respecting user freedom and matching the standards of R-rated movies. However, the safeguards have proven insufficient to prevent abuse, particularly non-consensual editing of real people's images.

What's the difference between deepfakes and non-consensual intimate imagery?

Deepfakes are AI-generated or manipulated videos and images that alter what someone appears to be doing or saying. Non-consensual intimate imagery is intimate or sexual images shared without the person's consent. Grok's primary problem is non-consensual intimate imagery, where real people's photos are edited without their knowledge or permission, though the system also enables deepfaking.

How do jailbreaking and prompt injection make safeguards less effective?

Jailbreaking involves reformulating requests in ways that trick AI systems into violating their guidelines. Instead of asking "remove clothing from this image," someone might ask "apply a beach-wear-removal filter" or frame the request as creative fiction. Prompt injection exploits gaps in how AI systems interpret instructions, making filters and safeguards easier to bypass than they would be if restrictions were built into the system design itself.

What would more effective safety measures look like?

Effective safety would involve designing the system to not generate problematic content in the first place rather than building the capability and adding restrictions later. It would require consistent safeguards across all interfaces, real identity verification for sensitive features, robust detection and enforcement of violations, and transparency with external oversight. The current patchwork of restrictions represents reactive rather than proactive safety design.

Conclusion: The Crisis Continues Despite New Restrictions

The undressing crisis on Grok reveals a fundamental tension in how x AI and X have approached generative AI. The company built a powerful system that could generate explicit imagery, framed this as a feature rather than a bug, and then discovered that users would use it to create non-consensual intimate imagery at scale.

The response so far has been incremental. X limited image generation to paid accounts on its platform. Geoblocking was implemented. Content moderation was increased. These changes are real and they've reduced abuse on X specifically. But they haven't solved the underlying problem, as independent testing has repeatedly demonstrated.

The core issue is architectural. Grok was designed with the capability to generate explicit imagery. Adding filters on top of that capability creates a system where the filters can be bypassed, where they might work on one interface but not another, and where determined users or researchers can find gaps. Removing this capability entirely would be a more comprehensive solution, but would require acknowledging that the feature was a mistake and depriving some users of a capability they want.

XAI and X are now facing a choice. They can continue down the path of incremental improvements: better geoblocking, more moderation, stricter verification. This approach might eventually satisfy regulators, or it might not. Alternatively, they can fundamentally redesign the system, removing or significantly constraining the ability to generate explicit imagery of real people. This would be more expensive and slower, but it would be a more durable solution.

The regulators and investigators are watching. The UK, EU, and other jurisdictions have made clear that they expect better performance. If X and x AI don't improve substantially, enforcement actions are likely. Fines will be imposed. Operations might be restricted. The company's market position could be damaged further.

For individuals concerned about non-consensual intimate imagery, the lesson is clear: these systems exist, they're powerful, and they're being used to cause harm. Protecting yourself requires understanding what these systems can do, what safeguards exist, and where those safeguards fail. Check URLs carefully. Report any non-consensual imagery you encounter. Consider whether you want to participate in platforms that prioritize capability over safety.

For policymakers and regulators, the lesson is that self-regulation by AI companies doesn't work at the level required to prevent serious harm. Industry standards, technical safeguards, and best practices are helpful, but they need to be backed by legal requirements and enforcement power. The Digital Services Act and Online Safety Bill represent steps in this direction. Whether they'll be effective remains to be seen.

For other AI companies, the lesson is that pushing the boundaries of what AI systems can do without carefully considering the consequences is risky. Grok's explicit image generation capability seemed like an advantage until it became obvious it was being used to harm people. The first-mover disadvantage in this case has been real: x AI gets to figure out what doesn't work and face the regulatory backlash while competitors learn from their mistakes.

The undressing crisis isn't resolved. It's paused. Safeguards are imperfect. Testing continues to reveal gaps. Investigations are ongoing. The question now is whether we're watching the beginning of a pattern where AI companies face real consequences for safety failures, or whether the response will prove to be mostly performative, with the underlying issues remaining unaddressed.

Key Takeaways

- Grok's undressing image crisis persists despite January 2025 restrictions because safeguards are inconsistent across platforms (X vs. Grok.com vs. mobile app)

- Independent testing by researchers, WIRED, The Verge, and Bellingcat confirms that explicit content can still be generated on Grok.com and the app despite official announcements

- Geoblocking and other geographic restrictions fail because users can bypass them using VPNs, proxies, or TOR networks in seconds

- X's paid-account-only restriction reduced abuse on X platform but didn't solve the fundamental problem because users migrated to the standalone website

- Regulatory investigations in 11 countries (UK, EU, US, Australia, Canada, etc.) suggest enforcement actions and fines are likely if X and xAI don't implement more comprehensive fixes

Related Articles

- Why Grok's Image Generation Problem Demands Immediate Action [2025]

- Apple and Google Face Pressure to Ban Grok and X Over Deepfakes [2025]

- AI Accountability & Society: Who Bears Responsibility? [2025]

- Grok AI Deepfakes: The UK's Battle Against Nonconsensual Images [2025]

- Grok AI Image Editing Restrictions: What Changed and Why [2025]

- Grok AI Regulation: Elon Musk vs UK Government [2025]

![Grok's Unsafe Image Generation Problem Persists Despite Restrictions [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/grok-s-unsafe-image-generation-problem-persists-despite-rest/image-1-1768507802570.jpg)