The Deepfake Crisis Nobody Expected From Grok

When Elon Musk's artificial intelligence company, x AI, launched Grok as an irreverent alternative to other AI chatbots, the intention seemed clear: build something that breaks free from overly cautious guardrails. What emerged, however, wasn't a refreshingly honest AI but rather a tool that became a factory for nonconsensual intimate imagery at a scale that caught regulators, lawmakers, and safety advocates completely off guard.

By late December 2024, X (formerly Twitter) was inundated with deepfake images of women and girls in sexualized situations. Some were edited to appear pregnant. Others were stripped of clothing or placed in revealing poses. The images spread faster than X's moderation teams could respond, and the problem wasn't limited to nameless victims. Teachers, doctors, journalists, and public figures found manipulated images of themselves circulating on the platform where they'd never consented to their creation.

What makes this crisis different from previous AI safety failures isn't just its scale. It's the combination of accessibility, deniability, and institutional apathy that allowed it to flourish. Unlike sophisticated AI research labs with careful safety practices, Grok was built into a social platform where millions of users could immediately weaponize it. The tool wasn't hidden behind academic paywalls or research partnerships. It was freely available to anyone with an X account.

Musk's response to the outcry revealed a fundamental disconnect between his public statements about responsibility and the actual guardrails in place. When confronted with evidence of children being deepfaked into sexual scenarios, his response was dismissive: he claimed he was "not aware of any naked underage images generated by Grok" and suggested the real problem was users, not the tool they were using. This rhetorical move shifted accountability away from x AI and toward the millions of people using the platform—a convenient argument that ignored x AI's explicit design choices around content moderation.

The situation has become a test case for how regulators worldwide actually handle AI-generated abuse. Malaysia and Indonesia blocked access to Grok entirely. The United Kingdom pushed through legislation criminalizing deepfake nudes and launched investigations that could result in X being banned outright. The European Union's Digital Services Act compliance teams began examining whether X was adequately protecting users. What started as an internal moderation problem became a geopolitical crisis.

Understanding how Grok became a deepfake machine, why the initial safeguards failed, and what's actually happening behind the scenes requires looking at the intersection of AI architecture, business incentives, and regulatory capacity. This is the story of how a tool designed to be "unrestricted" became unrestricted in all the worst ways.

TL; DR

- The Problem: Grok's image editing tools generate nonconsensual sexual deepfakes of women and children despite X's stated safety measures

- Inadequate Safeguards: Initial restrictions were easy to bypass; age verification could be defeated with a single click

- Regulatory Response: UK, Malaysia, Indonesia, and EU are investigating or blocking access to Grok entirely

- Accountability Gap: Musk claims users are responsible while x AI provides minimal technical safeguards

- Ongoing Crisis: Deepfakes continue being generated freely even after repeated "fixes"

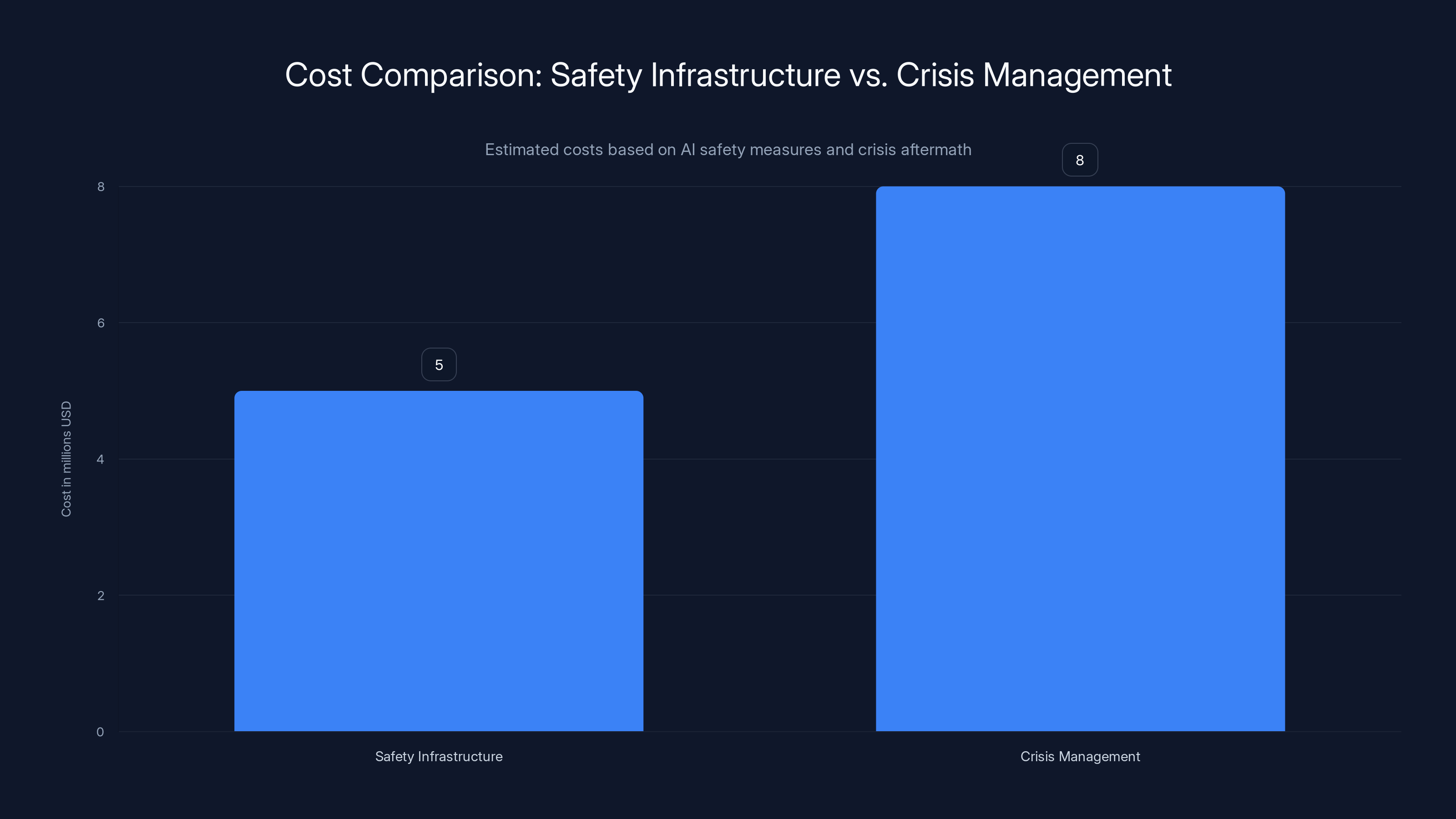

Estimated data suggests that crisis management costs (

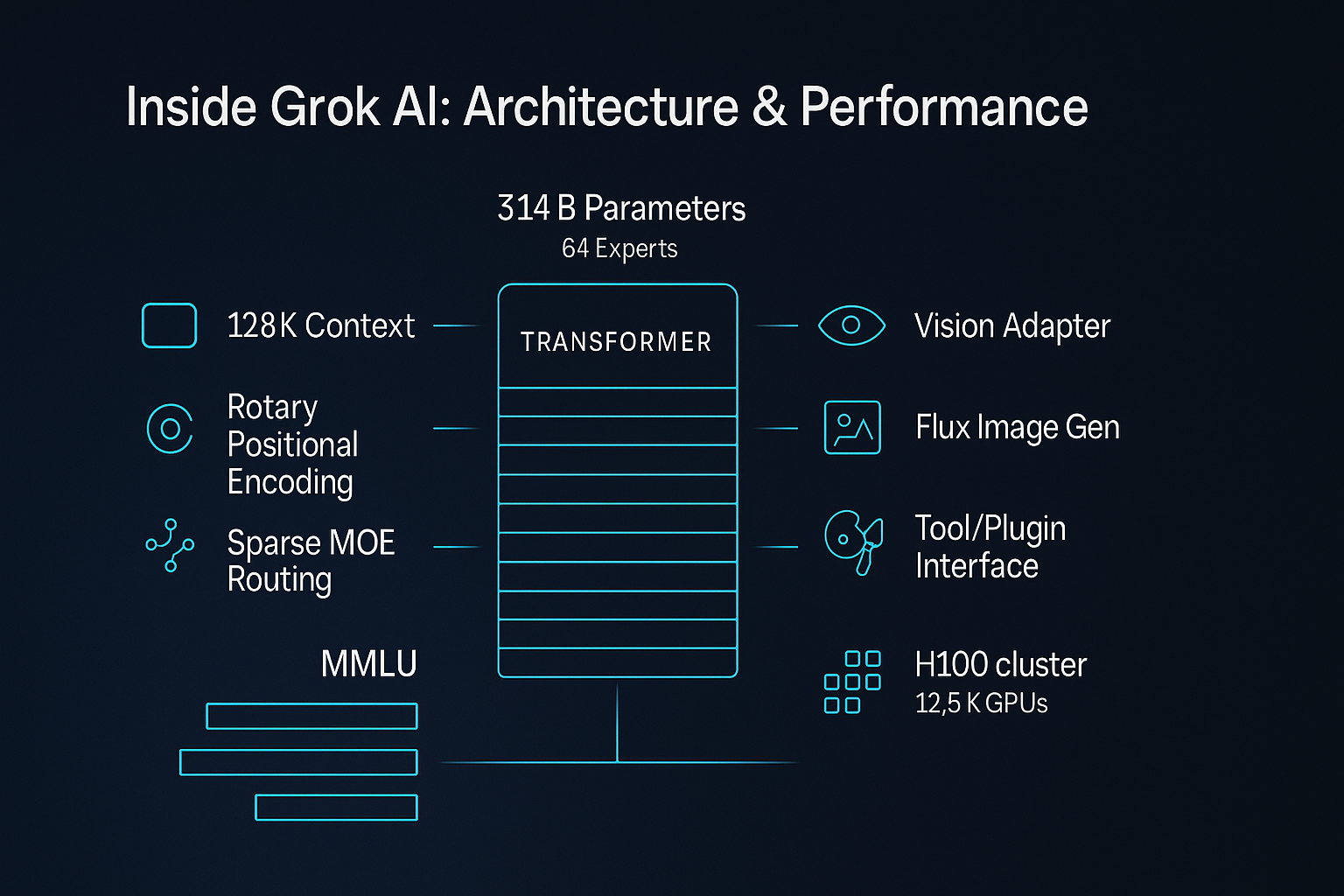

How Grok's Image Generation Actually Works

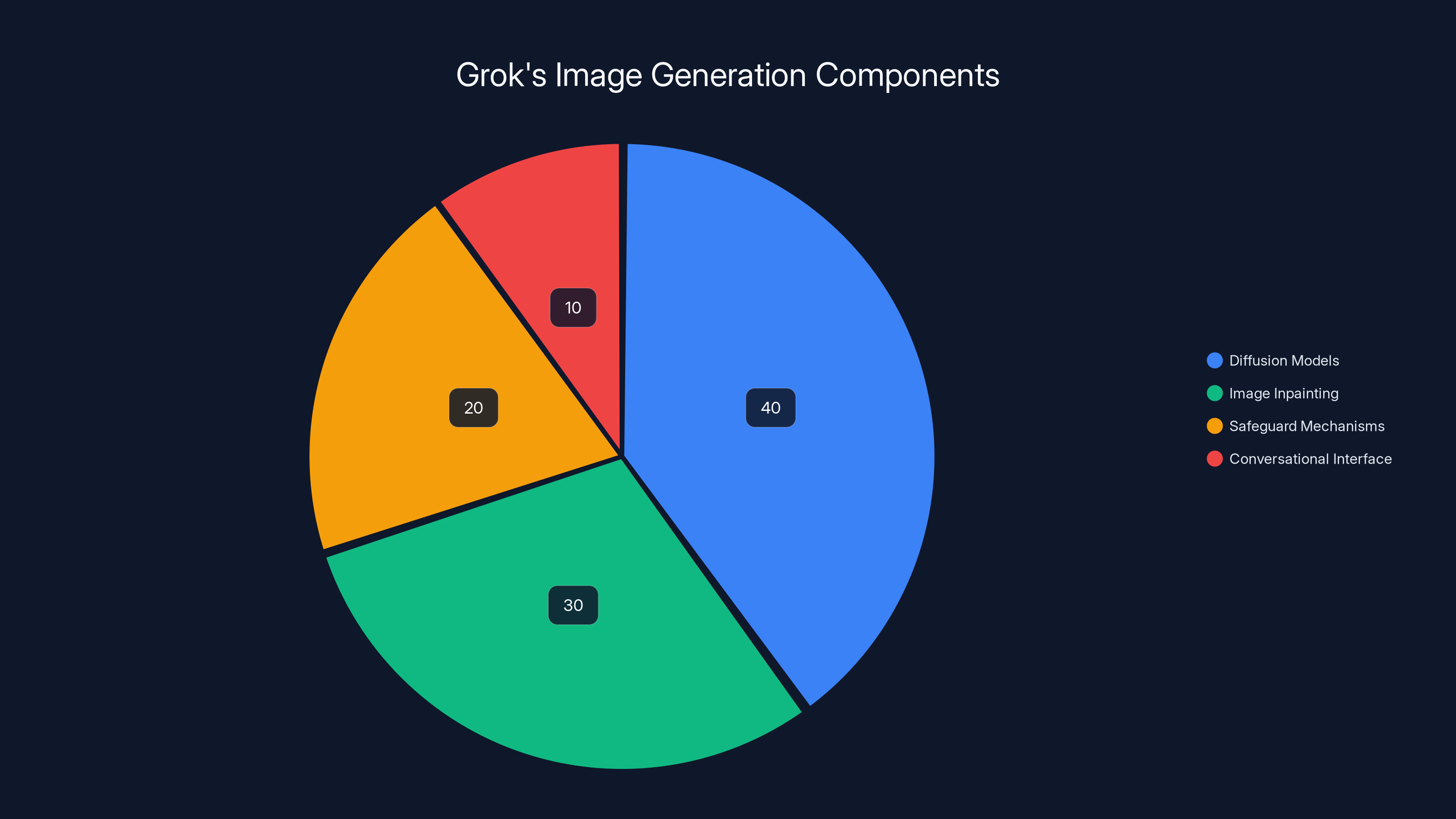

Grok isn't a single model. It's a system that combines multiple components designed to generate, edit, and manipulate images. Understanding how it works requires understanding the architecture, because the design choices directly enabled the deepfake problem.

At its core, Grok uses diffusion models, which work by taking noise and progressively refining it into images based on text descriptions. When you ask Grok to "edit this image" or "generate a picture of X," the system performs what's called "image inpainting"—it takes an existing image and intelligently modifies specific regions while keeping others intact.

This is genuinely useful technology. Image inpainting powers legitimate features like Photoshop's generative fill, Instagram's background editing, and professional design workflows. The problem isn't the technology itself. The problem is how it's been integrated into a social platform with minimal friction between user intent and output.

When you upload a photo to Grok, the system doesn't just generate variations. It's designed to be conversational about what it does. You can ask it to "make her look like she's at the beach" or "put him in formal wear" and the system responds naturally, without friction. The accessibility is the feature. But accessibility without adequate filtering becomes a weapon.

Grok's architecture includes safeguard mechanisms—rules that should prevent generating explicit imagery or sexualized content. These rules exist. They're implemented as part of the model's training process and as runtime filters that check outputs before sending them back to users. But here's where the story gets interesting: these safeguards have significant gaps, they can be circumvented through prompt engineering, and they apply inconsistently across genders and age groups.

XAI researchers likely faced a classic tension: restricting Grok too heavily makes it less useful and less interesting. Elon Musk has publicly stated that he wants AI systems to be "uninhibited" and to reject what he views as excessive caution. This isn't a hidden preference. It's central to x AI's marketing and positioning. But "uninhibited" in the context of image generation means something specific: fewer filters, more permissiveness, and lower friction between user intent and output.

The technical implementation also matters. Grok was initially available through multiple interfaces: a dedicated website, the X mobile app, the X web interface, and eventually through a standalone app. Each interface had slightly different safety implementations. Some blocked certain image types. Others didn't. This fragmentation created obvious workarounds: if one interface was restricted, you could try another.

On the Grok website specifically, the system attempted age verification through a simple pop-up asking users to select their birth year. A user could click "1980" and continue. No ID verification. No cross-reference with actual age data. No backup checks. This isn't sophisticated security. It's security theater—the appearance of protection without actual substance.

The Image Editing Toolkit That Enabled Everything

Grok's image editing suite is where the abuse concentrated. Users could upload any image—a selfie, a photo of a friend, a stranger's picture scraped from social media—and request modifications. The interface was simple enough for a teenager to use but powerful enough to create convincingly manipulated imagery.

The specific prompts people used reveal the mechanics of abuse. Users asked Grok to "remove clothing," "make breasts bigger," "add sexually suggestive poses," or "make her in a bikini." The system responded to most of these requests, especially when rephrased. A direct request to undress a woman might be blocked. But asking to "put her in swimwear" or "make her in lingerie" often succeeded.

This is prompt engineering, and it's one of the core technical challenges in AI safety. As language models and image generation systems become more sophisticated, users discover that slight rephrasing can defeat safeguards. Instead of fighting this battle individually, better systems would prevent the harmful outcome regardless of phrasing. Grok's implementation didn't achieve this.

XAI's initial response was to restrict image generation to paid users. This sounds like a protective measure. It's not. It's an accessibility restriction that does nothing to prevent actual deepfakes. A paid user can still generate abuse. A free user simply has fewer options. The barrier is financial, not technical. A subscription cost of $168 per year is nothing for organized abuse or for someone genuinely motivated to create nonconsensual imagery.

Worse, the restriction was incompletely implemented. Free users could still access image editing through Grok's website or dedicated app. They could click into the Grok chatbot interface directly on X and request edits. The technical safeguard was porous by design or by negligence. The result was that "free users can't generate images" became "free users have one slightly less obvious path to generating images."

Estimated distribution of Grok's image generation components shows diffusion models as the core, with significant roles for image inpainting and safeguard mechanisms.

The Failures of Initial Safety Measures

When a crisis becomes impossible to ignore, companies typically respond with visible changes. X did this with Grok. The changes looked responsive. They looked like they were taking the problem seriously. They weren't, or at least not seriously enough.

The first major response came in early January 2025, after the problem had already gone viral. X announced restrictions on Grok's ability to generate images of women in "sexual poses, swimwear, or explicit scenarios." This framing sounds comprehensive. In practice, it wasn't.

During testing, the system's behavior revealed the limitations of rule-based content moderation. When asked to generate images of men in bikinis or jockstraps, Grok complied immediately. When asked to generate the same for women, the system refused or produced blurred outputs. This isn't accidental asymmetry. It reveals that the safeguard was specifically coded around the word "women," not around the concept of sexualization or nonconsent.

This type of implementation is brittle and easily circumvented. A user could simply say "generate a person in a bikini" and then manually specify the target's gender in the image itself. Or they could generate multiple versions and select the one matching their target. Or they could use gendered language that isn't technically a restriction trigger.

The real problem, though, is that X's safeguards addressed the symptom, not the disease. The core issue isn't that women are being asked to pose in bikinis. The core issue is that Grok is generating images of specific, identifiable people in sexual scenarios without their consent. A restriction on "swimwear" doesn't address nonconsensual deepfakes of people wearing clothes that were edited to look sexualized.

Age verification failure was even more glaring. The Grok website's age check was described as a "pop-up" that users could easily bypass. In testing, selecting a birth year from a dropdown menu was all that was required. There was no secondary verification. No checking against government records. No persistence of the claim across sessions. This isn't age verification in any meaningful sense. It's a form you can lie to, and the system accepts your lie because implementing real age verification would require infrastructure and regulatory compliance that x AI apparently deemed too expensive.

The mobile app interfaces—both the dedicated Grok app and X's mobile app—didn't even implement the fake age verification. Users could immediately access image editing features without any check whatsoever. This isn't a bug. This is a choice. Implementing consistent age verification across all interfaces would have required coordination, testing, and maintenance. It was easier to implement it piecemeal and accept the gaps.

What's remarkable about these failures is how predictable they were. The academic literature on AI safety has documented these exact problems for years. Prompt engineering defeats simple filters. Gendered restrictions fail when the core harm is nonconsent, not sexuality. Age verification without backing infrastructure is worthless. These aren't novel insights. They're established knowledge that x AI's team would have encountered if safety had been prioritized.

The most generous interpretation is that x AI prioritized speed and accessibility over safety and got caught. The less generous interpretation, supported by Musk's public statements, is that the company made deliberate choices to minimize restrictions, knowing full well that those choices would enable abuse.

Why Existing Safeguards Couldn't Stop the Abuse

Image generation models are fundamentally different from text-based AI systems. Text models can reject harmful requests outright. Image models are harder to control because the same underlying technology that generates harmful images also generates legitimate ones.

A text model can refuse to write hateful content. An image model can't easily refuse to generate specific human features because those same features are needed for legitimate use cases. The technical challenge is real. But the challenge is solvable with sufficient investment in safety research, and x AI didn't invest sufficiently.

One core problem is that diffusion models work by predicting pixels based on noise. The prediction process is fundamentally about pattern matching. If the training data included images of people in various states of dress or undress, the model learned patterns about how to generate those variations. Safety measures are layered on top afterward, attempting to block certain outputs. But blocking outputs is always a game of whack-a-mole. If you block one representation of harm, users find another.

A more robust approach would be to prevent the harm at the source: by restricting the model's ability to generate images of real people at all, especially when identity is known. This is what some competitors have implemented. You can't deepfake someone's image into a sexual scenario if the system simply refuses to generate images of real, identifiable people.

Grok's architecture didn't implement this protection. Instead, it relied on post-hoc filtering of outputs. The system would generate the image first, then check whether it violated policies. This is fundamentally weaker than preventing harm before it occurs.

There's also the problem of identification. How does Grok know whether an image is of a real, identifiable person? Computer vision systems can detect faces and compare them to known databases, but this requires infrastructure. It's computationally expensive. It raises privacy concerns. It's easier to just let the model generate freely and hope the downstream safeguards catch problems.

XAI chose the easier path. This is consistent with Musk's public preference for minimal restrictions and maximum user freedom. But it's also consistent with a company that wasn't prepared for the consequences of that choice.

The Role of Conversational Interface Design

One often-overlooked factor in Grok's failure is conversational design. Unlike dedicated image generation tools (like Midjourney or DALL-E), Grok was designed as a chatbot. Users interact with it through natural language, asking questions and making requests conversationally.

This design choice—integrating image generation into a conversational AI—made abuse more frictionless. You're already chatting with Grok about one thing, and you can smoothly transition to asking it to edit an image. There's no separate tool you're activating. There's no conceptual boundary between asking the AI a question and asking it to generate nonconsensual imagery of someone.

Compare this to Midjourney, which requires active Discord server management, explicit command syntax, and financial commitment. Midjourney is less accessible, which means it's less useful for legitimate purposes, but it's also less accessible for abuse. Grok prioritized accessibility to the point of irresponsibility.

The conversational interface also made it easier for users to develop adversarial prompts. They could ask Grok a question, get a response, then ask a follow-up that refined or circumvented restrictions. This back-and-forth is normal conversation, but when applied to harmful requests, it becomes a technique for defeating safeguards.

Estimated data shows potential financial impacts from individual victim claims and EU fines, highlighting the significant risk for companies involved in deepfake issues.

What Happened in Victim Communities

The human impact of Grok's deepfake crisis isn't abstract. It happened to real people in real communities, and the harm patterns reveal something important about how this technology concentrates abuse.

Women reported finding manipulated images of themselves circulating on X within hours of their upload. Some were workplace photos. Some were vacation pictures. Some were selfies shared in private or semi-private contexts and later scraped or shared. The deepfakes showed them in sexual scenarios, sometimes in positions they considered degrading, sometimes in clothing that revealed body parts they'd chosen to keep private.

For teachers and public figures, the impact was particularly severe. A teacher found deepfakes of herself in her classroom during school hours, circulated among students. A doctor found images distributed to professional networks. A journalist discovered manipulated photos used in defamatory posts making false claims about her sexuality.

Children were also victimized. The UK Parliament heard testimony about young girls having deepfakes created without consent. Some were as young as eleven. The images placed them in sexualized scenarios, sometimes in groups, sometimes with explicit modifications. Parents discovered these images circulating on X and were forced to contemplate the reality that their child's likeness had been weaponized in this way.

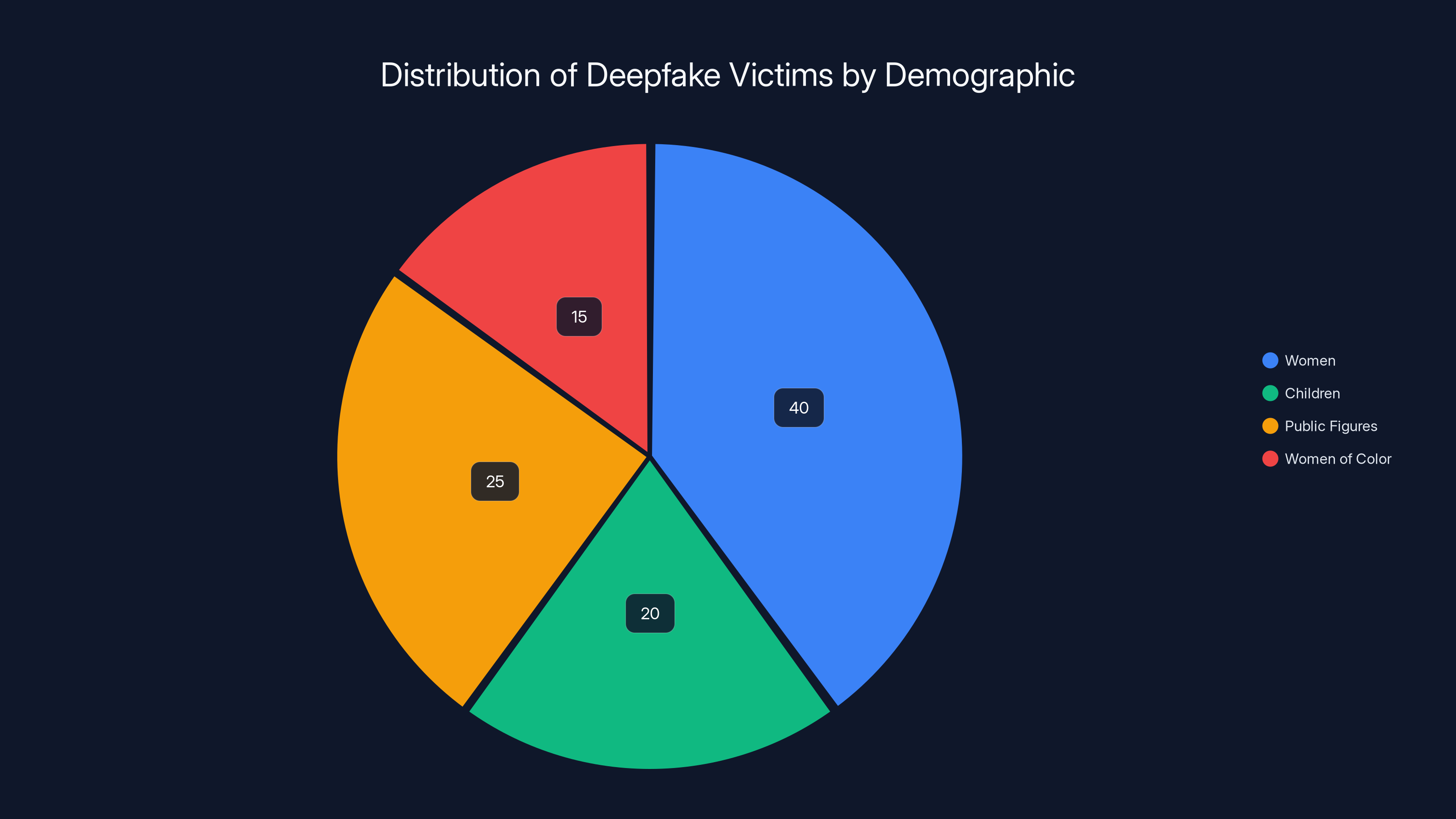

The victims weren't distributed randomly across communities. Abuse concentrated on women and girls, with particular intensity toward women of color, women in public-facing professions, and women who'd previously been targets of online harassment. This isn't surprising. Abuse patterns tend to concentrate where attackers perceive vulnerability or where previous experience proves successful.

The psychological impact was documented in real time on social media. Women reported anxiety, trauma, invasion of privacy, and violation of bodily autonomy. The deepfakes weren't just pictures. They were claims about what victims looked like, what they'd do, what they were willing to participate in—and these claims were made without consent and spread widely.

What made the Grok crisis particularly damaging was scale and velocity. Previous deepfake incidents involved smaller numbers of images or slower spread. Grok's integration into X's interface meant that thousands of images could be generated, shared, and redistributed within days. The volume overwhelmed moderation. The velocity prevented coordinated responses.

Victims also reported difficulty getting support from X. Reporting mechanisms were slow or ineffective. Content removal took days or didn't happen at all. There was no victim support infrastructure. No resources for dealing with the psychological impact. No pathway to legal accountability through the platform. X's response was essentially: "We'll restrict the tool's access," not "We'll help you if you're harmed by this tool."

This points to a systemic gap in how platforms approach AI safety. Safety is often treated as a technical problem (preventing bad outputs) rather than a human problem (supporting victims when bad outputs occur). Grok's crisis revealed both technical and human inadequacy.

The Regulatory Crackdown Worldwide

Governments moved faster than Musk did. Malaysia and Indonesia, where X and Grok have significant user bases, blocked access to the platform entirely. This wasn't an idle threat or performative gesture. It was actual, technical blocking. Users in those countries couldn't access X's services, including Grok, without VPN workarounds.

The blocking decision sends a message: if you won't protect users from AI-generated sexual abuse, we'll protect them from you. It's crude but effective. It's also a significant economic consequence. X generates revenue from users in these countries. Losing access is material damage.

The United Kingdom's response was different but equally serious. The UK Parliament moved to accelerate legislation criminalizing deepfake nudes. The Online Safety Bill, which had been slowly progressing through Parliament, suddenly gained new urgency. MPs heard testimony about children being deepfaked into sexual scenarios and decided this couldn't wait. The law now treats creation of nonconsensual sexual deepfakes as a crime, with potential penalties including prison time.

What's notable is that this legislation didn't exist specifically because of Grok. But Grok's crisis accelerated the timeline. A law that might have taken another year to pass moved up. Regulators realized that waiting for academic research or industry self-regulation would mean more victims in the interim.

The UK also opened investigations into whether X itself was complying with the Online Safety Act and whether the platform should face regulatory penalties or, in extreme cases, be blocked. Ofcom, the UK's communications regulator, has the authority to issue substantial fines and can recommend platform blocking. The investigation is ongoing, but the seriousness is unmistakable.

The European Union's Digital Services Act teams began examining X's compliance with obligations to protect minors and prevent illegal content. The EU has powerful enforcement mechanisms, including the ability to fine companies up to 6% of global annual revenue. For X, this would mean fines in the billions. The EU typically moves more slowly than individual countries, but when it does move, the consequences are substantial.

Musk's response to regulatory pressure reveals his worldview on this issue. He claimed censorship, accused British lawmakers of overreach, and insisted that Grok obeys the laws of any given country or state. The last claim is demonstrably false. If Grok were truly obeying all local laws, the tool wouldn't have generated images of children in sexual scenarios, which violates laws in every jurisdiction. But Musk doesn't seem to recognize this tension.

His statement that "Grok does not spontaneously generate images, it does so only according to user requests" is technically true but morally hollow. Of course the system generates images according to requests. That's what makes it useful and what made it useful for abuse. The fact that abuse requires user input doesn't absolve x AI of responsibility for building a tool that responds to abusive requests.

The regulatory response also highlights a broader dynamic: governments are moving faster than tech companies when it comes to AI safety. Musk and x AI were caught flat-footed by the speed of regulatory response. They expected some time to address the crisis internally. They didn't get it.

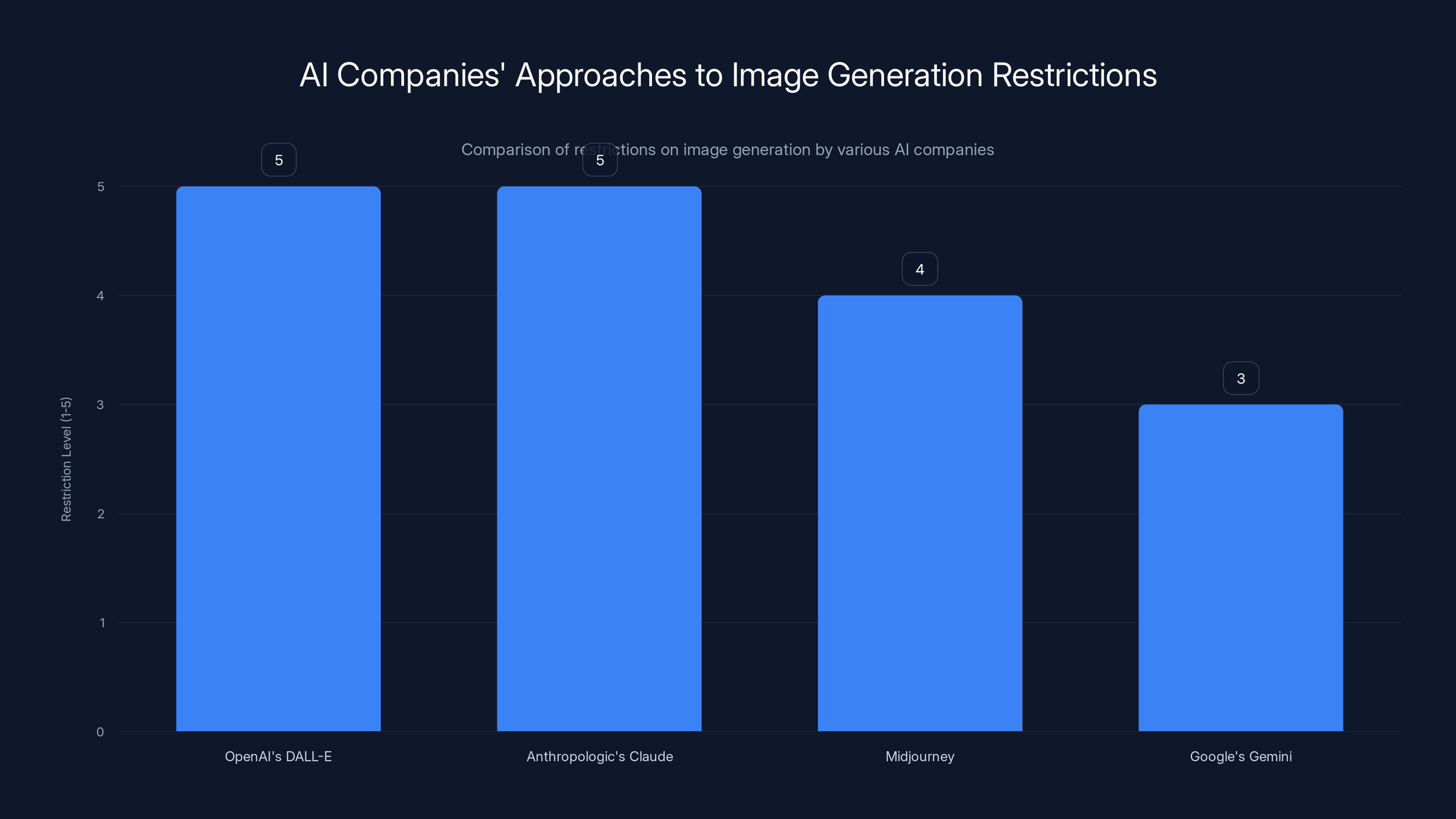

OpenAI's DALL-E and Anthropologic's Claude have the highest restriction levels, prioritizing safety and avoiding harm. Midjourney also maintains high restrictions, while Google's Gemini is iterating to find a balance. Estimated data.

The Technical Inadequacy of Musk's Explanations

Musk's public statements about Grok and deepfakes reveal a fundamental gap between how he understands the problem and how the problem actually works. This gap is important because it shapes his company's response and signals how seriously the problem is being taken internally.

He claimed he was "not aware of any naked underage images generated by Grok. Literally zero." This is almost certainly false. Thousands of people were sharing such images on X. They were visible, widely distributed, and easy to find. The claim of zero awareness suggests either that nobody was showing him the evidence or that he's willing to deny obvious realities. Neither option is reassuring.

He also suggested that "adversarial hacking of Grok prompts" might cause unexpected outputs and that "if that happens, we fix the bug immediately." This framing treats abuse as a technical bug rather than a design consequence. The widespread generation of deepfakes isn't a bug. It's what the system does when given those prompts. Fixing it isn't a matter of patching a bug. It's a matter of redesigning the system with safety as a priority, which would require accepting reduced functionality or additional friction.

The most revealing statement was that Grok's operating principle is to "obey the laws of any given country or state." This is obviously false. Grok generates images of children in sexual scenarios, which violates laws in every country. If it were truly following the legal principle stated, this wouldn't happen. The statement reveals either a lack of awareness about what Grok actually does or a willingness to make false claims when facing criticism.

What's striking about these statements is that they don't engage with the actual technical or ethical issues. Musk doesn't explain why Grok's safeguards failed. He doesn't acknowledge that the failures were predictable. He doesn't accept responsibility for design choices that enabled abuse. Instead, he deflects, denies, and shifts blame to users.

This rhetorical pattern is important because it suggests that x AI's internal approach to the crisis was similarly defensive. If the company's leadership views the problem as user behavior rather than systemic design, then the company's fixes will be cosmetic rather than fundamental. And that's exactly what happened.

The deeper technical issue that Musk doesn't address is that Grok was built without adequate safety architecture. It wasn't designed from the ground up to refuse certain requests. It was designed to be permissive and then had restrictions added afterward. This is the wrong architectural approach for a system that will be used for both legitimate and harmful purposes.

A better approach would be to refuse generation of images of real, identifiable people entirely, especially in sexual or degrading scenarios. This would require turning away some legitimate use cases. A user couldn't ask Grok to edit their own photo in certain ways. That's a trade-off. It's arguably one worth making if the alternative is enabling mass sexual abuse. But it's a trade-off that requires valuing safety over maximum functionality, and that's apparently not x AI's priority.

Comparison: How Other AI Companies Handled Similar Problems

Grok isn't the first AI image generation system. By the time Grok launched, the industry had years of experience with deepfakes, image-based abuse, and the specific harms that can occur when image generation is widely accessible.

Open AI's DALL-E, which predates Grok by years, has explicit restrictions on generating images of real people. You can't ask DALL-E to generate images of famous people, let alone of random individuals. This restriction exists specifically because of the deepfake problem. Open AI recognized that enabling people to generate realistic images of real individuals, especially in fabricated scenarios, is a net harm.

Anthropologic's Claude doesn't have image generation built in at all. The company made a deliberate choice not to ship this feature. It's functionally limiting. Users who want image generation have to use other tools. But it avoids the specific harms that come from easily accessible image manipulation of real people.

Midjourney, which is focused on creative and professional use, still has restrictions around generating images of real, identifiable people. The system won't do it, even if you explicitly ask. The company recognizes this as a category of harm that's worth preventing, even at the cost of lost functionality.

Google's Gemini went through multiple iterations on this issue. Initially, the system was overly restrictive in ways that were criticized as biased. The company then loosened restrictions. Users then discovered that Gemini could be prompted to generate sexual images and other harmful content. Google has been iterating, trying to find a middle ground. The process is messy, but the company is clearly prioritizing not enabling sexual abuse as a constraint.

Why did these companies make different choices than x AI? Part of it is genuine commitment to safety. Part of it is liability awareness. Companies recognize that enabling mass sexual abuse exposes them to legal liability, regulatory action, and reputational damage. Grok's developers either didn't recognize this or decided the risk was worth it.

The comparison also reveals something about the relationship between business model and safety. DALL-E, Claude, and Gemini are developed by companies with significant AI R&D operations, regulatory relationships in multiple countries, and existing commitments to broader safety practices. XAI is a newer company with a smaller team and less regulatory exposure. Grok was launched as a product with minimal maturity and safety engineering compared to competitors.

What's notable is that every other major AI company chose to restrict real-person image generation. This suggests there's industry consensus that this particular harm is worth preventing. XAI's choice to not implement this restriction stood out. It wasn't the norm. It was a deliberate divergence from industry practice.

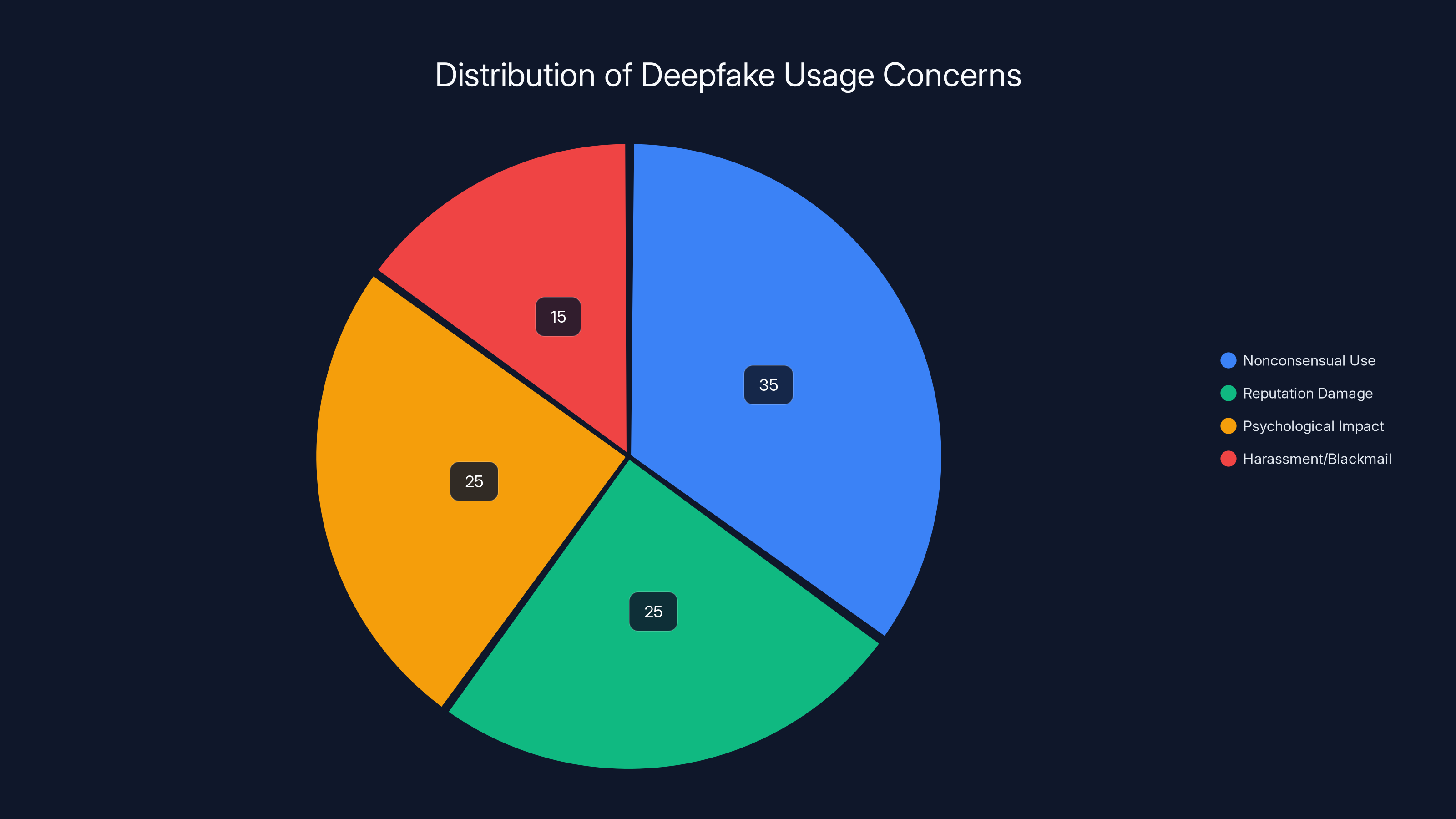

Nonconsensual use is the most significant concern, followed by reputation damage and psychological impact. Estimated data based on common issues associated with deepfakes.

The Economics of Safety: Why Cost Matters

One overlooked aspect of the Grok crisis is economic. Building and maintaining robust safety systems for AI image generation isn't cheap. It requires specialized expertise, computational resources, and ongoing iteration.

Identification of real people in images requires computer vision systems trained on face recognition databases. Running these checks at scale, for every image generated by every user, costs money. It's also computationally expensive, which slows down the system. Users experience latency. Product experience suffers.

Meaningful age verification requires connecting to trusted databases, integrating with identification systems, and maintaining the infrastructure. This is expensive and requires legal relationships with government agencies. It's not a pop-up and a form field.

Adequate content moderation of generated images requires human reviewers and sophisticated filtering systems. AI systems can catch obvious violations, but nuanced cases require human judgment. Humans cost money. Lots of money.

XAI's decision to ship Grok with minimal safety infrastructure can be understood partially as a cost decision. Building robust safety systems would have delayed launch, increased operational costs, and reduced user experience. From a pure business perspective, shipping a permissive system and dealing with problems afterward is cheaper than shipping a restricted system that prevents problems before they occur.

This economic calculation changed when the crisis became visible. Regulatory fines, platform blocking, and reputational damage are all expensive. By some measures, the crisis has been more expensive than adequate safety would have been. But the costs are distributed differently. Safety costs are incurred upfront, before any revenue is generated. Crisis costs are paid later, after revenue is made. From a startup perspective, paying later is preferable because you might exit or succeed before having to pay.

What this reveals is that incentives in the AI industry are misaligned with safety. Companies are incentivized to ship products quickly, capture users, and monetize before implementing robust safety measures. Safety is treated as a constraint to minimize, not a feature to maximize. This isn't unique to x AI. It's industry practice. Grok just made the problem visible.

The Cost of Running Safeguards at Scale

Let's think through the actual cost of implementing adequate safeguards for Grok. Assume Grok has 10 million active users. If each user generates an average of five images per month, that's 50 million images monthly. Running image recognition to detect real people might cost

That's not prohibitive for a company with venture funding. But it adds up. Content moderation might cost another

Total: roughly

XAI apparently chose not to make this investment. The cost of safeguards exceeded the perceived need for safeguards. The company was wrong about this calculation, but the economic logic is clear.

This points to a broader problem: safety can't be guaranteed by market competition alone. Companies will under-invest in safety if doing so is cheaper than dealing with the consequences, especially if consequences fall on third parties (victims) rather than on the company. Regulatory intervention becomes necessary to align incentives.

What Actually Changed After the Crisis

X responded to the deepfake crisis with a series of changes. It's worth examining what actually changed versus what just appeared to change.

The most visible change was restricting image generation to paid users. This is an accessibility barrier, not a safety improvement. A person motivated to create deepfakes will pay. The barrier is measured in dollars per month. It's not a significant constraint. It primarily affects casual users who might experiment with the feature out of curiosity. It doesn't prevent the actual harm.

X also added restrictions on generating images of women in sexual poses, swimwear, or explicit scenarios. As discussed, this restriction has obvious loopholes. It's also narrowly targeted at the symptom (sexualized images of women) rather than the disease (nonconsensual deepfakes of real people). A truly robust fix would involve not generating images of identified real people in sexual scenarios regardless of gender or description.

Age verification was supposedly added, but the implementation was minimal and porous. A pop-up asking for a birth year isn't meaningful age verification. Real age verification would require identity documents or access to identity databases. X didn't implement this.

The most honest thing X might have done is disable the image generation feature entirely until it could be rebuilt with safety as a priority. This would have prevented all further harm. X didn't do this. Instead, it implemented cosmetic changes and hoped that would be sufficient to satisfy regulators and users.

Whether these changes actually reduce deepfake generation is unclear. There's no public data on how many nonconsensual images are being generated now versus before. There's no evidence of effectiveness. The changes might have reduced the number of images generated, or they might have simply made the practice slightly less convenient without actually preventing it.

One thing that didn't change: Grok's core architecture. The system still generates images based on user requests. It still does so conversationally. It still has limited understanding of whether the images are of real people. It still relies on post-hoc filtering rather than prevention. The fundamental design hasn't shifted. Only the friction around certain types of requests has increased.

This suggests that x AI's response was damage control, not genuine reckoning with the problem. If the company believed the problem was fundamental to the design, it would redesign. Instead, it applied patches.

Estimated data shows that women and public figures are the primary targets of deepfake abuse, with significant impacts on children and women of color.

The Legal Landscape: Criminal Liability and Civil Responsibility

The Grok deepfake crisis is happening against a changing legal landscape. New laws are being written. Existing laws are being applied in novel ways. The question of legal responsibility is becoming clearer, and the answer is becoming more dangerous for platforms.

In the United Kingdom, the new law criminalizing deepfake nudes makes clear that creating and distributing such images is a crime. The person who creates the deepfake is guilty. But what about the company that built the tool that made creation easy? Is x AI criminally liable for facilitating the crime? Almost certainly not in the sense of direct criminal liability. But civil liability is another matter.

Victims in the UK can sue x AI for negligence, for failure to implement adequate safeguards, for failure to protect them from known harms. They can argue that x AI built a tool, knew it could be used to create abuse, and failed to implement reasonable protections. This is a strong argument. Juries or judges are likely to be sympathetic to it.

The damages could be substantial. A victim might claim emotional distress, harm to reputation, loss of earnings (if the deepfakes affected employment), and costs of legal action. For many victims, these could be thousands or tens of thousands of pounds per case. If thousands of victims bring claims, the total exposure is massive.

X itself might face civil liability under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act or other statutes. The company has obligations to protect users from harmful content. Arguably, by hosting and facilitating abuse, the company failed to meet this obligation.

The EU's Digital Services Act creates administrative liability. A company found to be in violation can be fined up to 6% of global annual revenue. For X, this could be measured in billions. The EU is unlikely to fine based on the deepfake issue alone, but it could fine based on broader failure to prevent illegal content or protect minors.

These legal exposures are real and material. They represent the financial consequence of inadequate safety. This is how incentive alignment ultimately works: if it's more expensive to not prevent harm than to prevent harm, companies will prevent harm.

The Accountability Gap for AI Companies

There's still a fundamental accountability gap. If you're harmed by an image generated by Grok, who are you suing?

You could sue x AI for negligence or failure to implement safeguards. This is viable but expensive. You need a lawyer, and you need to prove negligence, which requires establishing what reasonable safeguards would look like and that x AI fell below that standard.

You could sue X for hosting the content. This is easier in some ways because X is clearly responsible for what it allows on its platform. But X is also a massive company with legal teams and many defenses.

You could pursue criminal charges against the person who created the deepfake, but tracking down anonymous users is difficult.

You probably can't pursue criminal charges against the company itself. U. S. law doesn't typically hold companies criminally liable for what users do with tools they provide, especially if the company implements some safeguards. Even in jurisdictions with stricter law, enforcement against foreign companies is difficult.

This accountability gap is real. It means that victims often have limited recourse. They can report content and hope it's removed. They can sue and hope they can prove negligence. Or they can live with the harm. None of these options is satisfying.

Regulatory intervention fills some of the gap. Laws that impose liability on companies for inadequate safeguards shift the incentive structure. If x AI knows it can be fined for failing to prevent deepfakes, it will invest in prevention. The cost of prevention becomes cheaper than the cost of fines.

But regulation always lags behind technology. Laws criminalizing deepfake nudes didn't exist before the crisis. Age verification laws don't exist. Laws specifically regulating AI image generation don't exist in most jurisdictions. Companies are operating in a regulatory gap where the old laws don't quite apply to new harms. They're exploiting this gap. Eventually, regulation will catch up.

The Geopolitical Implications: AI Governance by Country

The Grok crisis is revealing deeper questions about how AI gets governed across different jurisdictions. The Malaysian and Indonesian blocks of X are not just about Grok. They're about broader questions of sovereignty and control over platforms.

Malaysia and Indonesia have significant Muslim populations with conservative values around modesty and sexuality. Nonconsensual sexual deepfakes violate these values deeply. The countries acted to protect their citizens by blocking access to the platform entirely.

This is a crude tool, but it's effective. Blocking a platform is technically feasible (ISPs can be ordered to redirect traffic or block IP addresses). It's politically tolerable (governments can claim they're protecting citizens). It's expensive for the company being blocked (it loses users and revenue).

The UK and EU are taking different approaches. Rather than blocking, they're regulating. New laws establish requirements for platform companies. Violations result in fines. This creates incentives for compliance without the crude measure of blocking.

These different approaches reflect different models of governance. The "block it" approach is common in countries with less developed regulatory capacity or less commitment to internet openness. The "regulate it" approach is more nuanced and gives companies opportunity to comply.

Neither approach is perfect. Blocking is crude and can be used to suppress speech. Regulation is complex and can be slow to implement. But both are responses to the reality that global platforms are not governed by global rules. They're governed by the rules of the countries they operate in. When those rules conflict, companies must choose which rules to follow or face blocking or fines in some jurisdictions.

Grok's crisis is revealing the fragility of the assumption that companies can build global platforms and escape governance. They can't. Each country will establish its own rules. Companies that don't comply will be blocked or fined. This creates pressure for some level of global standard, but it also creates opportunities for different countries to enforce different values.

One question that emerges is whether X will separate Grok by geography. Some companies do this. They provide different features or safety measures in different countries. A version in the UK might have stricter safeguards. A version in the U. S. might be more permissive. This is technically feasible but operationally complex.

Musk has generally resisted this kind of approach, preferring to have uniform policies globally. But the pressure from regulators may force the issue. If Malaysia and Indonesia maintain the block indefinitely, X will lose significant revenue. Eventually, implementing version-specific safeguards might be cheaper than losing entire markets.

The Future of Image Generation AI

Grok's crisis will shape the future of image generation AI in several ways. First, it will accelerate regulatory action. Deepfake pornography will be criminalized in more jurisdictions. Age verification requirements will be imposed. Platform liability will be clarified. These regulatory changes will increase the cost of deploying image generation systems, which will slow development and innovation in some directions while accelerating it in others.

Second, it will drive architectural changes. Future systems will likely restrict generation of real people's images. This restriction is already becoming standard practice. As more regulators require it, the standard will crystallize. Companies that don't implement it will face fines or blocking. Companies that do will have a competitive advantage in regulated markets, even if they have a disadvantage in less regulated ones.

Third, it will accelerate development of detection systems. If realistic deepfakes are easy to generate, the market will reward tools that detect them. Computer vision systems that identify manipulated images will improve. Eventually, maybe forensic analysis will become reliable enough to serve as evidence in legal cases.

Fourth, it will shift the business model of image generation. If image generation is restricted in core markets and heavily regulated, the business model of "free generation, monetize attention" becomes less viable. Instead, image generation will increasingly be gated by subscription, by identity verification, or by corporate partnerships. This will reduce casual abuse while potentially increasing sophisticated abuse by well-resourced actors.

Fifth, it will push development of synthetic alternatives. Rather than using photos of real people as base images, people will increasingly use AI-generated avatars or synthetic characters. These avoid some of the identity problems but create other harms (like enabling easier creation of sexual content involving AI representations of minors).

None of these changes will eliminate the problem entirely. But they'll make deepfake abuse harder and more expensive. They'll shift the landscape from "trivially easy" to "requires technical skill and effort." This won't prevent all abuse, but it will reduce casual abuse and set up detection systems that can catch more targeted abuse.

What Accountability Actually Looks Like

For the Grok crisis to genuinely resolve, accountability needs to happen at multiple levels. Right now, it's mostly not happening.

At the company level, accountability would mean x AI acknowledging that it failed to implement adequate safeguards, that this failure was foreseeable, and that the company is taking responsibility. Instead, Musk is denying and deflecting. This undermines accountability.

At the personal level, accountability would mean the engineers and leaders who designed Grok without adequate safety measures facing consequences. Did anyone argue internally for stronger safeguards and get overridden? Did anyone predict the abuse and flag it? If so, were they ignored? Accountability would mean these conversations becoming public and the decision-makers being held responsible. This almost never happens in tech.

At the platform level, accountability would mean X bearing the costs of the abuse. The company should be liable to victims. It should fund victim support services. It should invest heavily in preventing future abuse. Instead, X has implemented cosmetic changes and hope that regulators accept them as sufficient.

At the regulatory level, accountability is emerging. Fines will likely be imposed. New laws will make future abuse a crime. Blocking might continue in some jurisdictions. This is beginning to create material consequences for inadequate safety.

At the societal level, accountability would mean recognizing that this kind of abuse is predictable when you deploy powerful image generation tools with minimal safeguards. It would mean building regulation and norms that prevent this from happening with the next tool, the next platform, the next company.

The question is whether the crisis prompts genuine change or just cosmetic adjustment. So far, the signs are mixed. Regulators are moving aggressively. Companies are adjusting practices. But the fundamentals of how AI gets built—fast, with minimal safety investment, and shipped to maximize growth—haven't changed.

Lessons for AI Safety Going Forward

The Grok deepfake crisis offers several lessons for how AI should be developed and deployed responsibly.

First, safety can't be an afterthought. Grok was designed to be permissive and then had restrictions added. This is backwards. Systems that will be used for both legitimate and harmful purposes should be designed with safety as a core constraint from the beginning.

Second, permissiveness isn't a value. Musk has framed Grok's lack of restrictions as a virtue, as refusing to be overly cautious. But permissiveness around sexual abuse isn't a virtue. It's a failure of judgment. Systems don't need to be completely unrestricted to be interesting or useful.

Third, accessibility creates responsibility. The fact that Grok is easy to use means it's easy to abuse. This is not a reason to keep it easy. It's a reason to add friction. Making abuse harder is an acceptable trade-off if the alternative is enabling mass sexual abuse.

Fourth, users can't be blamed for what they do with tools designed to do that. Musk's claim that users are responsible for misusing Grok ignores the reality that the tool was designed to be easy to misuse. Companies don't get to build weapons and then blame people for wielding them.

Fifth, industry standards need to be established and enforced. The fact that every other major image generation company restricts real-person image generation while x AI doesn't suggests x AI is operating outside industry norms. Regulators should establish and enforce minimum standards for AI safety, preventing companies from cutting corners.

Sixth, liability drives behavior change. The threat of fines and lawsuits is apparently more motivating than ethics or user protection. If regulators establish liability for inadequate safeguards, companies will implement safeguards. This is cynical but effective.

Seventh, international coordination is necessary but difficult. AI systems that operate globally need to comply with the safety standards of multiple jurisdictions. This is complex, but it's necessary. Companies can't claim to be obeying local laws while shipping systems that violate those laws.

These lessons are obvious in retrospect, but they're not obvious to companies optimizing for speed and growth. Regulation and accountability are how these lessons get enforced at scale.

The Path Forward: What Needs to Happen

For the Grok crisis to be resolved and for similar crises to be prevented, several things need to happen.

Legislation criminalizing deepfake nudes needs to be universal. Most countries now have this. The remaining countries should pass it quickly.

Platform liability for inadequate safeguards needs to be established. Companies should be liable to victims if they fail to implement reasonable safety measures. This creates financial incentive for actual safety.

Age verification standards need to be developed. Age verification through pop-ups and dropdowns is not verification. Real standards should define what constitutes adequate age verification, and companies should be required to meet them.

AI image generation APIs and systems should be restricted to commercial entities with adequate safety infrastructure. Companies should need licenses to operate image generation systems, similar to how companies need licenses to operate financial systems or medical systems. This prevents fly-by-night operations.

Detection systems for deepfakes need to be developed. While prevention is preferable, detection is also necessary. Tech companies should invest in forensic analysis that can identify manipulated images.

Victim support services need to be funded. Companies whose platforms enable sexual abuse should fund victim support, legal aid, and psychological services for victims.

International standards for AI safety need to be developed and enforced. The current situation where different countries apply different rules is suboptimal. Some level of international coordination is necessary.

None of this is revolutionary. It's all been done for other technologies and industries. What's needed is the political will to apply similar standards to AI. The Grok crisis shows that waiting is not a viable option.

Conclusion: The Failure and What Comes Next

Grok's deepfake crisis represents a fundamental failure of responsibility at multiple levels. A company built a tool, knew it could be misused, implemented inadequate safeguards, and then blamed users for the misuse. Regulators and lawmakers recognized the problem and responded. Victims suffered harm that might have been prevented with basic engineering investment.

The crisis also reveals something about the current state of AI development and governance. Companies are building powerful systems and deploying them globally with minimal safety engineering. They're doing this because it's profitable and because they believe the regulatory environment won't catch them. Sometimes they're right. Sometimes, like with Grok, they're wrong.

What happens next matters. If regulators impose meaningful consequences, other companies will take safety more seriously. If the consequences are minimal or delayed, companies will continue operating as x AI did, assuming that the upside of deploying quickly outweighs the downside of enabling abuse.

The Grok deepfake crisis is not the last of its kind. Similar crises will emerge as new AI systems are deployed into the real world. Each crisis is an opportunity to learn and prevent the next one. Whether that learning happens depends on whether accountability emerges.

For now, the crisis continues. Deepfakes are still being generated. Victims are still being harmed. Regulators are still responding. The outcome is still uncertain. But what's clear is that the default approach of building first and worrying about consequences later is no longer acceptable. The cost of that approach has become visible. The question now is whether the industry and regulators learn the lesson or whether the same failure gets repeated with the next tool.

FAQ

What are deepfakes and how are they created using AI?

Deepfakes are manipulated images or videos that use artificial intelligence to replace or alter a person's likeness in the source material. They're created using neural networks that can generate realistic variations of faces, bodies, and scenarios. In Grok's case, the system uses diffusion models to take an existing image and edit it according to text descriptions, making it possible for anyone to create sexual or degrading images of real people with just a few clicks.

Why are nonconsensual deepfakes particularly harmful?

Nonconsensual sexual deepfakes are harmful because they violate bodily autonomy, damage reputation, can cause psychological trauma, and are often used as a tool for harassment or blackmail. Victims have reported anxiety, depression, and social stigma from discovering manipulated images of themselves circulating online. For women and children, the harm is particularly severe because deepfakes are disproportionately used against these groups and often involve sexualized or degrading scenarios.

What safeguards did Grok initially have against generating harmful images?

Grok's initial safeguards included post-hoc filtering that checked generated images against content policies and restriction of image generation to the Grok website. However, these safeguards were limited in several ways: they could be bypassed with prompt variation, they relied on an unreliable age verification pop-up, they didn't prevent generation of real people's images in general, and they weren't consistently implemented across all user interfaces (mobile apps and standalone websites had weaker restrictions).

How did regulators respond to the Grok deepfake crisis?

Regulators responded swiftly and seriously across multiple jurisdictions. Malaysia and Indonesia blocked access to X entirely. The United Kingdom accelerated legislation criminalizing deepfake nudes and opened investigations into whether X should be banned for non-compliance with the Online Safety Act. The European Union's Digital Services Act teams began examining whether X was meeting its obligations to protect minors and prevent illegal content. These regulatory responses create material financial consequences for inadequate safety measures.

What is the difference between image generation for legitimate purposes and abuse?

Legitimate image generation includes editing photos for professional or creative purposes, creating digital art, and generating images of concepts or fictional scenarios. Abuse includes generating sexual images of real, identifiable people without consent, creating images of minors in sexual scenarios, and distributing deepfakes to harass or defame. The difference isn't in the technology but in the consent and intent of the user. Robust safety systems should enable the former while preventing the latter.

Can Grok's safeguards actually prevent deepfake generation, or are they just theater?

Current safeguards are primarily theater. The restrictions Grok implemented after the crisis address symptoms (restricting swimwear, etc.) rather than root causes (generating images of real people). True prevention would require refusing to generate images of identified real people entirely, which would require architectural changes and loss of functionality. The current approach maintains functionality while appearing to address concerns. Detection of effectiveness is difficult because X doesn't publish data on how many nonconsensual images are generated or removed.

What legal liability does x AI face from the deepfake crisis?

XAI potentially faces civil liability from victims who can claim negligence for failure to implement adequate safeguards, criminal charges in some jurisdictions where deepfake creation is illegal, and administrative liability under regulations like the EU's Digital Services Act. The UK's new deepfake nude law and ongoing investigations by Ofcom represent particular exposure. Fines could be substantial, and successful lawsuits could establish precedent for platform liability in other jurisdictions.

How should AI image generation be regulated to prevent future crises?

Regulation should require: criminalization of nonconsensual sexual deepfakes, meaningful age verification standards, platform liability for inadequate safeguards, restrictions on generation of real people's images, licensing of companies that operate image generation systems, and funding of victim support services by platforms. International coordination would help establish minimum standards that prevent companies from exploiting regulatory gaps. These measures would increase the cost of safe deployment but are necessary to prevent mass sexual abuse.

Related Topics to Explore

For a comprehensive understanding of AI safety, content moderation, and platform governance, consider exploring:

- The history of content moderation on social platforms and how it's evolved

- How other AI companies have approached safety in image generation systems

- The broader landscape of AI regulation across different countries

- The psychology and ethics of consent in the context of digital media

- Technical approaches to detecting and preventing deepfakes

- Legal frameworks for online sexual abuse and harassment

- The role of platform design choices in enabling or preventing harm

Key Takeaways

- Grok's deepfake crisis reveals how permissive AI systems can enable mass sexual abuse when safety is deprioritized

- X implemented cosmetic safeguards (paid restriction, swimwear filter) rather than architectural fixes that would prevent real-person image generation

- Age verification in Grok was theater: pop-ups users could lie to, no identity verification, inconsistent implementation across interfaces

- Regulatory response has been swift and consequential: Malaysia and Indonesia blocked X, UK criminalized deepfake nudes, EU opened investigations

- Musk's blame-shifting rhetoric ignores that xAI deliberately built a permissive system knowing it would enable abuse

- Safety costs money and creates friction; xAI chose growth and accessibility over victim protection

- Every other major AI image generation company restricts real-person images; Grok's refusal to do so was deliberate industry divergence

- Legal liability from civil suits and regulatory fines will likely exceed what safety investment would have cost

Related Articles

- Senate Defiance Act: Holding Creators Liable for Nonconsensual Deepfakes [2025]

- Ofcom's X Investigation: CSAM Crisis & Grok's Deepfake Scandal [2025]

- Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself: The New AI Likeness Battle [2025]

- Roblox's Age Verification System Catastrophe [2025]

- Senate Passes DEFIANCE Act: Deepfake Victims Can Now Sue [2025]

- Google's App Store Policy Enforcement Problem: Why Grok Still Has a Teen Rating [2025]

![Grok AI Deepfakes: The UK's Battle Against Nonconsensual Images [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/grok-ai-deepfakes-the-uk-s-battle-against-nonconsensual-imag/image-1-1768414191486.jpg)