The Harvard and UPenn Data Breaches: What You Need to Know Right Now

It's February 2026, and two of America's most prestigious universities just had their alumni databases dumped online. Shiny Hunters, a prolific cybercrime group, published over one million records stolen from both Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania on their extortion website. The universities had refused to pay the ransom demands, so the hackers followed through on their threat.

Here's what actually happened, why it matters, and what you should do if you're an alumnus.

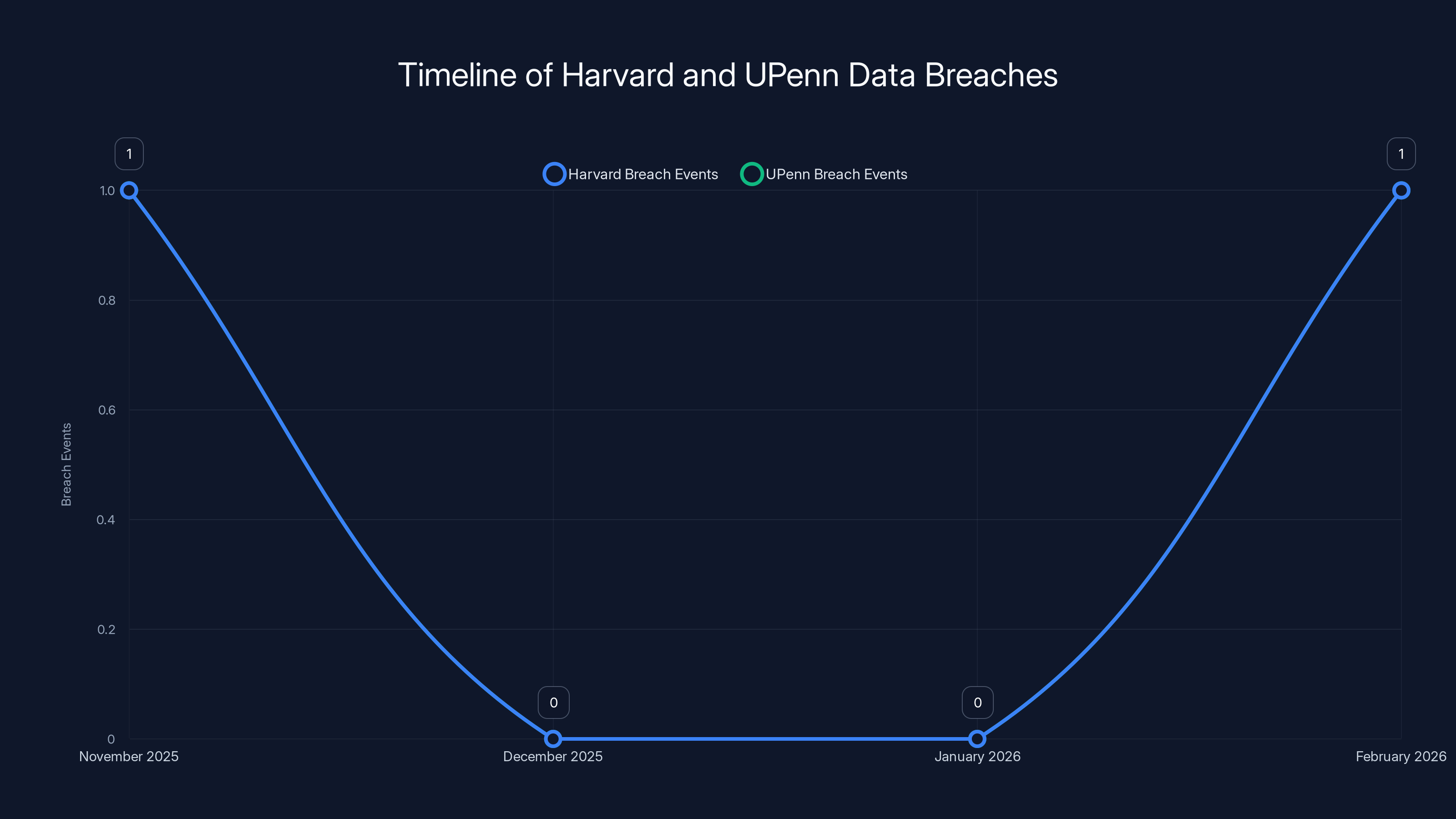

The Timeline: How This Unfolded

The breaches didn't happen overnight. UPenn confirmed a breach in November when hackers sent emails from official university addresses to alumni announcing the hack. Harvard followed with its own announcement in November as well. But the real story isn't just that they got hacked—it's what happened when they refused to pay.

Both universities disclosed the incidents publicly and worked on containment. They probably thought the worst had passed. Instead, the hackers simply waited a few months and then published everything. This is the new playbook for ransomware gangs: breach, demand payment, and if you refuse, weaponize the data as public humiliation.

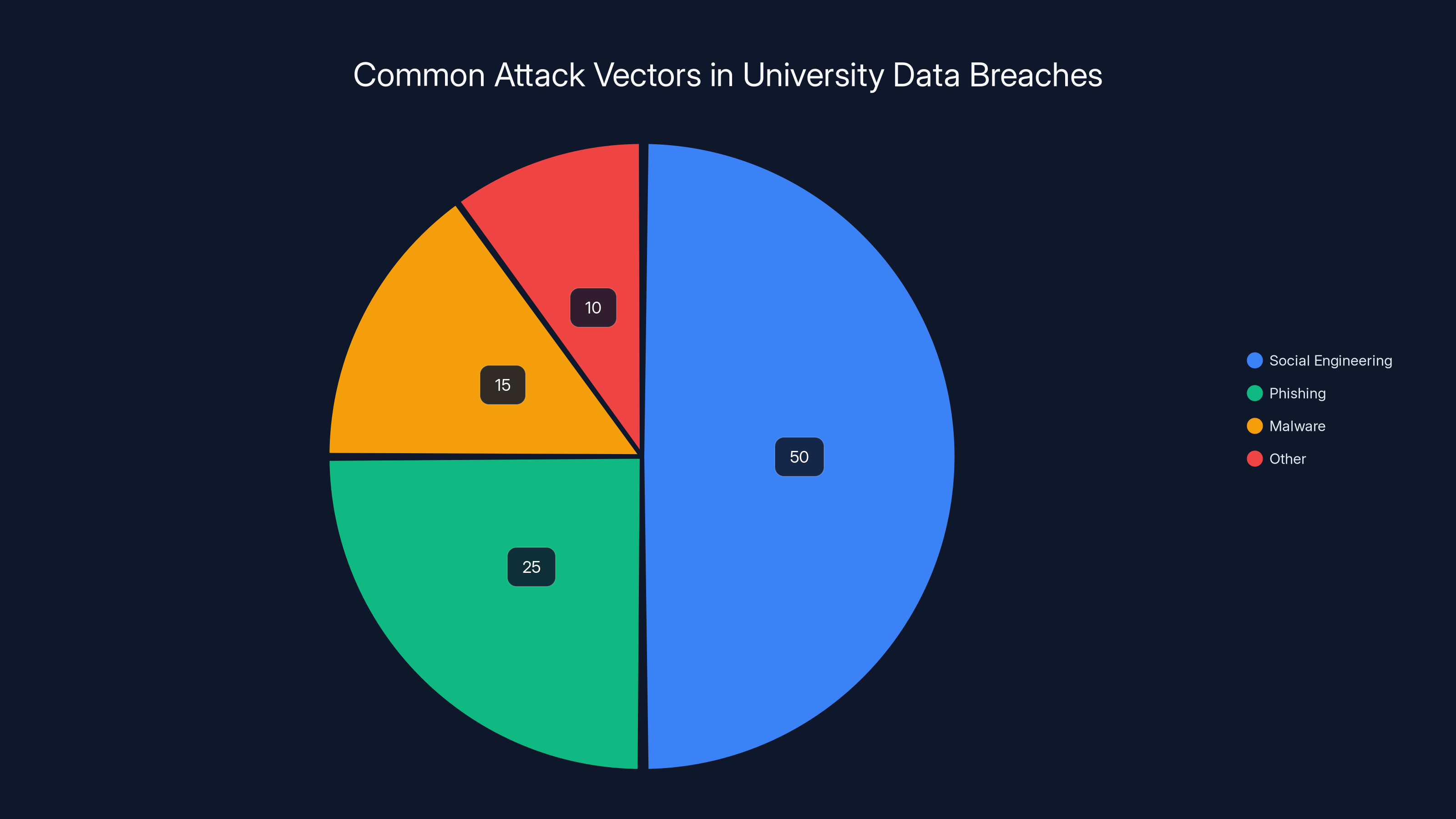

The timing matters. These weren't zero-day exploits or sophisticated nation-state attacks. These were social engineering attacks, which means someone at these universities clicked something they shouldn't have. The universities didn't keep the details quiet about how they got compromised—they actually told us. That transparency is both admirable and alarming.

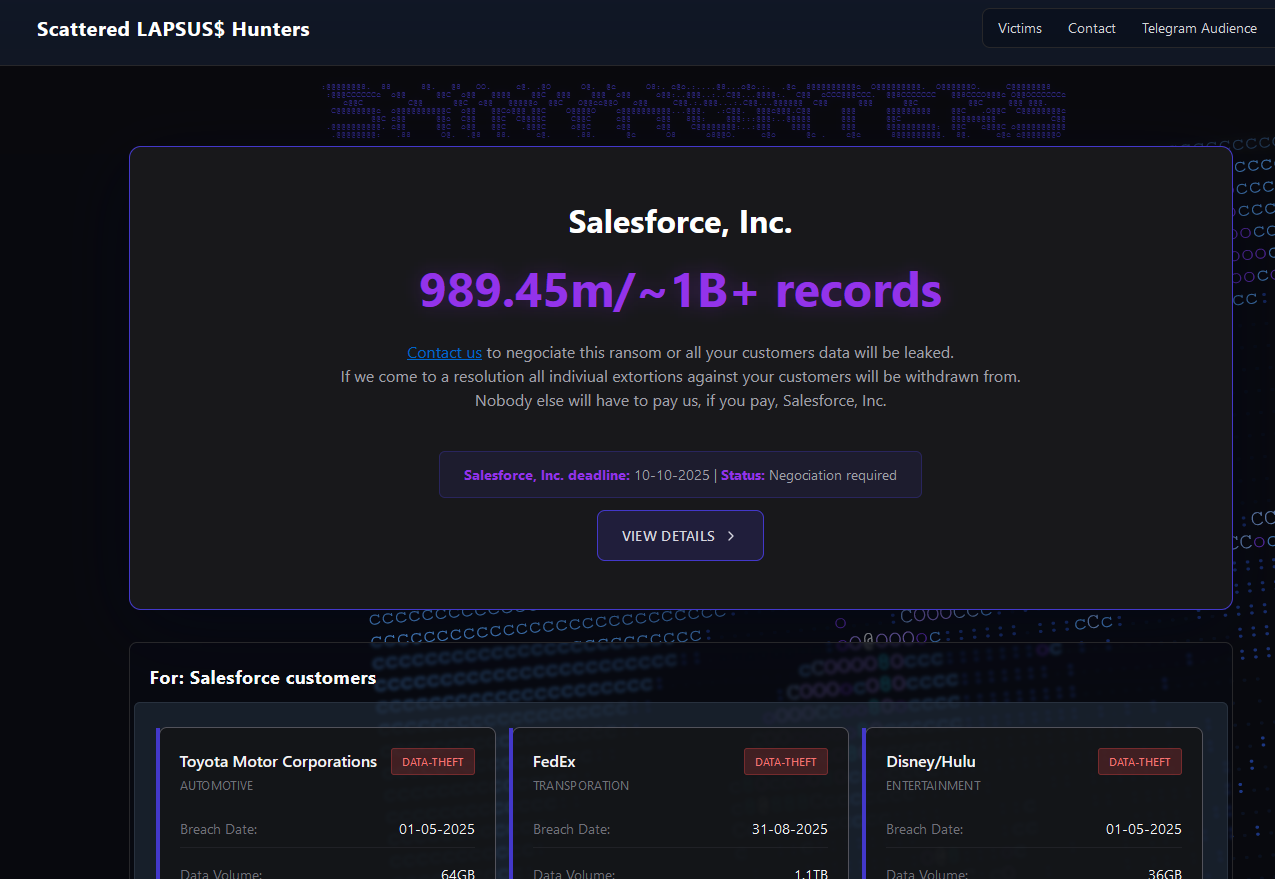

Understanding Shiny Hunters: Who They Are

Shiny Hunters isn't a fly-by-night operation. They've been active for years, hitting targets ranging from healthcare systems to gaming companies to government databases. What makes them distinctive is their willingness to stick around and exploit victims systematically.

The group operates on a straightforward business model: they hack, they demand ransom, they publish. They maintain a public leak site where they showcase their work and threaten organizations into paying. It's extortion weaponized through data exposure.

What's interesting about the Harvard and UPenn breaches is that Shiny Hunters made claims about political motivations during the UPenn hack—specifically mentioning affirmative action policies. But this group isn't known for having political causes. The rhetoric appears to have been part of the social engineering tactic, designed to make the hack feel more threatening or to exploit internal divisions. It's manipulation at scale.

The group has successfully compromised organizations far more sophisticated than most people realize. Healthcare systems with HIPAA compliance. Financial services with PCI-DSS requirements. Universities with security budgets. The fact that Shiny Hunters keeps operating suggests either they're very good at covering their tracks or law enforcement priorities are focused elsewhere.

Social Engineering: The Real Vulnerability

Here's where both universities made mistakes, and it's worth understanding because your organization probably has the same vulnerability.

UPenn's breach came through social engineering. That's a fancy way of saying hackers impersonated someone trustworthy and tricked employees into giving up access. Harvard's breach came through voice phishing, which is even more personal—someone called, claimed to be from IT, and convinced the target to click a malicious link or open an attachment.

Both attacks require no technical sophistication. No zero-day exploits. No sophisticated malware. Just good social manipulation. And here's the thing: social engineering works because it exploits the human brain's natural tendency to be helpful and trusting.

When someone calls and says they're from IT and there's an urgent account security issue, most people want to help fix it. They don't want to be the person who brought down the email system. So they click. They open the attachment. They reveal the password. And suddenly, an attacker has legitimate access to university systems.

The universities presumably have security training. They probably have policies. They probably tell employees not to click suspicious links. But policies don't protect against a well-executed social engineering attack because the attack bypasses the technical layer entirely and goes straight to human psychology.

This is why breaches at universities are particularly common. Large institutions have expansive networks, thousands of employees with varying security awareness, and alumni databases full of personally identifiable information. The barrier to entry is lower than at Fortune 500 companies with dedicated security operations centers.

What Data Was Actually Stolen

The data dumps that Shiny Hunters published contain information that matches what both universities said was compromised. We're talking about alumni databases here, not student records or financial data (though the universities didn't explicitly rule out either).

From Harvard, the stolen data includes email addresses, phone numbers, home and business addresses, event attendance records, details of donations to the university, and biographical information tied to fundraising and alumni engagement activities. Basically, everything in a donor database.

From UPenn, the data comes from "systems related to Penn's development and alumni activities," which is the university's way of saying the alumni and donor database. The specific contents haven't been publicly detailed, but Tech Crunch verified portions of the dataset by matching data against known student ID numbers and public records.

Here's what matters: this isn't just embarrassing. This is actionable intelligence for criminals. If you're an alumnus of either school and you've donated, they now have your email, phone number, home address, and a record of how much you care about education. That makes you a target for:

- Spear-phishing attacks: Criminals can now craft highly personalized emails that reference your donation, your alma mater, even specific events you attended

- Phone-based social engineering: Calling and claiming to be from the university, referencing your specific donations

- Identity theft: With your address, email, phone, and potentially other biographical data, criminals can attempt account takeovers

- Targeted robbery: Knowing which alumni are wealthy enough to donate significant amounts

The duration and scope of the breach are also important. These weren't momentary accesses. These were sustained compromises where attackers had time to systematically extract data. That suggests the universities didn't detect the intrusions quickly, which is common and depressing.

The Ransom Demand and Extortion Playbook

Shiny Hunters didn't just hack for fun. They demanded payment. Both universities refused. So the hackers published everything online as punishment and as a threat to future victims.

This is the ransomware-as-extortion model that's dominated cybercrime for the last five years. The playbook looks like this:

- Breach the target

- Exfiltrate data

- Send ransom demand (often millions of dollars in cryptocurrency)

- Set a deadline

- Threaten to publish data if payment isn't made

- If payment isn't made, publish the data

- Use the published breach as proof of capability for future targets

Why does this work? Because organizations are often more worried about data exposure than they are about operational disruption. Ransomware that encrypts systems is one thing—at least you know the problem is contained to your network. But data that's out in the world can be bought, sold, used, and weaponized indefinitely. That's a different kind of risk.

The universities' decision not to pay is the right one from a policy perspective. Paying ransoms funds criminal operations, creates incentives for more attacks, and doesn't guarantee that the data won't be published anyway. Some organizations have paid and still had their data released. But that doesn't make the decision easier when you're the one responsible for protecting hundreds of thousands of people's personal information.

What's notable is that the universities apparently had incident response plans that didn't involve ransom payment. That suggests either they were confident in their ability to weather the reputational damage or they had insurance that covered the notification costs and other expenses. Universities often have cyber insurance, which changes the calculus significantly.

Why Universities Are Such Attractive Targets

Harvard and UPenn aren't anomalies. Universities have been dealing with data breaches for years. There are structural reasons why academic institutions are so vulnerable.

First, universities have open networks. They're designed to facilitate collaboration and student access. Security at a university isn't like security at a bank. A bank can say no to almost everything. A university has to say yes to enough things to keep research and learning moving. That creates gaps.

Second, universities employ thousands of people across dozens of schools and departments, many of whom aren't primarily focused on security. A graduate student in physics doesn't think of themselves as defending the perimeter. A development officer calling alumni doesn't think about phishing risks. The security culture is distributed and often weak in the places where it matters most.

Third, the reward for breaching a university is substantial. Alumni databases contain not just contact information but relationship history, donation amounts, and often educational background. That information is worth money on criminal marketplaces. A database of wealthy, educated individuals who are emotionally invested in their alma mater is particularly valuable for social engineering.

Fourth, universities are typically slower to patch and update than corporate environments. Budget constraints, legacy systems, and the complexity of shared infrastructure mean that security patches sometimes lag. The vulnerability that was patched six months ago might still be present in an obscure system nobody thought to update.

Fifth, universities often have research networks that connect to external systems and partner institutions. Those connections are vectors for attack. If a partner institution gets compromised, the university might be accessible through that connection.

The Notification Compliance Question

Both universities eventually notified affected individuals, but there was a gap between the breach occurring, the discovery, the notification, and the public data release. That timeline matters because it determines legal obligations.

Privacy laws like GDPR in Europe require notification within 72 hours of discovering a breach. California's privacy law requires notification without unreasonable delay. New York's SHIELD Act requires notification "in the most expedient manner possible." Different states have different requirements.

The universities likely had to analyze what data was actually compromised, verify the breach, figure out which individuals were affected, and then send notifications. That process takes time. But hackers don't wait for legal compliance. They just publish data when they decide to.

UPenn's original breach disclosure page has since been taken offline, which is interesting. Universities sometimes remove pages as part of crisis management, but it also means there's less public documentation of what happened and how it was handled. That's actually problematic for the individuals affected, who lose access to information about what specifically was compromised.

Harvard's approach was to be transparent about the types of data stolen: email addresses, phone numbers, addresses, event attendance, donation details, and biographical information. That specificity is helpful for individuals trying to understand their risk level.

Verifying the Breach Data: How Tech Crunch Did It

Tech Crunch didn't just take Shiny Hunters' word that they had the data. They verified it. Here's how that process works, because it matters for understanding whether the published data is actually real or just claimed.

Verification typically involves:

- Cross-referencing with public records: Matching names, student ID numbers, and email addresses against publicly available information like university directories or LinkedIn profiles

- Alumni confirmation: Reaching out to known alumni and asking them to verify that their personal information in the leaked database matches what they believe is in the universities' systems

- Pattern analysis: Looking for indicators that the data structure matches what you'd expect from a university alumni database, like the presence of specific fields that wouldn't be in a fabricated dataset

- Source verification: Confirming that the data is coming from Shiny Hunters' legitimate leak site and not a copycat or fraud

The fact that Tech Crunch was able to verify the data with alumni and public records provides credibility. It means this isn't just Shiny Hunters claiming they have data. The data appears to be real.

What this verification process doesn't tell us is the complete scope of the breach. It's possible there's more data than what's been published. Some data might have been deleted before the full exfiltration. Some records might be corrupted or incomplete. The verification confirms that real data was stolen, but the full picture is probably known only to Shiny Hunters and the universities themselves.

The Response: What the Universities Did

UPenn's spokesperson, Ron Ozio, said the university is "analyzing the data and will notify any individuals if required by applicable privacy regulations." That's a measured response that essentially says they're determining scope and following legal requirements.

The key phrase is "if required by applicable privacy regulations." That suggests UPenn's legal team is evaluating which states' laws apply and what the notification obligations actually are. If the affected individuals are spread across multiple states, different rules apply. If they're primarily in Pennsylvania, that's a different legal landscape than if they're nationwide.

Harvard didn't respond to Tech Crunch's request for comment. That's actually not unusual for Harvard. Universities often have institutional policies about media engagement, and security breaches can involve sensitive legal matters that aren't immediately commentable.

What we don't know from public statements is whether either university is cooperating with law enforcement, working with FBI cyber divisions, or pursuing any legal action against Shiny Hunters. Those conversations probably happen behind closed doors.

We also don't know if the universities are implementing specific security improvements as a result of these breaches. Are they upgrading security training? Implementing multi-factor authentication more broadly? Segmenting networks? Changing who has access to the alumni database? Those operational changes usually aren't announced publicly, but they're what actually matter.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Beyond Harvard and UPenn

These breaches are significant not because Harvard and UPenn are special, but because they're examples of a widespread problem.

Higher education institutions have been increasingly targeted by ransomware and data theft operations. Universities like this have everything criminals want: contact information, financial information, donor details, and they're perceived as having limited technical sophistication compared to banks or major corporations.

The breach also demonstrates the limitations of notification-based security. Both universities notified people, but notification doesn't protect anyone. It informs them that their data has been compromised, which is useful for their own risk management. But it doesn't keep the data from being published. It doesn't prevent criminals from using it.

There's also a second-order effect: once this data is published online, it enters the public criminal infrastructure. Criminals can buy, trade, share, and use it for years. Someone five years from now might use information from these breaches to conduct a targeted phishing attack. The damage doesn't end when the data is published.

For organizations evaluating their own security posture, these breaches offer important lessons:

- Social engineering is the primary vector: Not sophisticated hacking. Regular people tricked into providing access.

- Detection and response matter less than prevention: If you can't prevent social engineering, you at least need to detect it fast. A three-month-long intrusion is worse than a three-week-long intrusion.

- Ransoms and extortion are different problems: Organizations need to plan for data theft separately from encryption-based ransomware. Some breaches are purely about stealing data.

- Database segmentation works: If the alumni database had been isolated from general network access, compromising general network systems wouldn't have immediately granted access to sensitive data.

Lessons for Individuals: What to Do If You're Affected

If you're an alumnus of Harvard or UPenn, here's what you should actually do beyond just being aware.

First, assume your information is now public. Don't operate under the assumption that it's still protected or that authorities will contain it. It's on a criminal website. It will be archived. It will be used.

Second, monitor your financial accounts for unusual activity. Criminals who have your name, address, phone number, and email can attempt account takeovers using that information. They can call your bank's customer service line pretending to be you. They can attempt password resets on accounts they don't have access to yet.

Third, be suspicious of any unsolicited contact claiming to be from the university. If you get a call or email from someone claiming to be from Harvard's development office, from UPenn's IT department, or from any university organization, verify it independently. Don't use phone numbers or email addresses from the message. Look up the official contact information yourself and reach out through that channel.

Fourth, consider placing a security freeze on your credit with the three major credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union). A security freeze prevents new accounts from being opened in your name without your explicit permission. It's free to place and remove, and it's one of the most effective protections against identity theft.

Fifth, monitor your credit report. Use Annual Credit Report.com to get your free credit reports. Look for accounts you didn't open, inquiries from lenders you didn't contact, and other signs of fraud.

Sixth, be aware that this information might be used for targeted social engineering against you or your family members. Criminals might call claiming to be from the university with some urgent issue related to your account or your donation. They might use specific details from the breach to make themselves sound legitimate. Don't engage with unsolicited contact, no matter how legitimate it seems.

What Organizations Should Learn From This

If you're responsible for security at any organization similar to Harvard or UPenn, these breaches are instructional.

The fact that both breaches came through social engineering and voice phishing should not be surprising. That's where most breaches come from. But it should motivate action.

Start with security training that actually works. Most security awareness training is ineffective because it's generic, forgettable, and disconnected from real work. Better training is specific, repeated, and tied to actual job responsibilities. A development officer needs phishing training that uses university-specific scenarios. An IT staff member needs training that covers the specific social engineering tactics used in their industry.

Implement multi-factor authentication broadly, not just for IT staff. If your alumni database requires two factors to access, you significantly increase the barrier to entry for attackers. Yes, this is more friction. But the breach of two prestigious universities is also friction.

Segment your networks so that compromising one system doesn't give access to everything. If someone breaches the general network, they shouldn't immediately have access to the alumni database. Create network boundaries, implement least-privilege access, and assume that adversaries will eventually break into your network. The goal is limiting what they can do once they're in.

Implement detection mechanisms for unusual database access. If someone who works in IT is suddenly querying the entire alumni database at 3 AM, that should trigger an alert. Unusual access patterns can indicate a compromise, even if the attacker is using legitimate credentials.

Prepare an incident response plan before you need it. Knowing who makes decisions, what your legal obligations are, how you'll communicate with affected individuals, and how you'll manage the media response will make the actual response faster and more effective.

Don't assume that notification is sufficient response. Notify people who are affected, but also implement security improvements so that you don't have to notify people again. That's the thing that builds back trust.

The Law Enforcement Angle: What's Being Done

We don't have public statements about active law enforcement investigations into Shiny Hunters or these specific breaches. That's typical. Law enforcement agencies don't announce investigations while they're ongoing because it compromises the investigation.

However, Shiny Hunters has been operating for years, which suggests either they're extremely good at avoiding attribution or law enforcement hasn't prioritized them relative to other threats. International cybercriminal groups operating out of countries without extradition treaties are difficult to prosecute, even when identified.

The FBI does have cyber divisions and international partnerships, but bandwidth is limited. There are thousands of data breaches every year, and law enforcement can't investigate all of them. Prioritization typically goes to breaches affecting critical infrastructure, national security, or financial systems. A university alumni database, while significant, might not be top priority.

That doesn't mean nothing is happening. Shiny Hunters' leak site and operations are probably being monitored. If they make mistakes and leave forensic artifacts, that information is probably being collected. But active prosecution of international cybercriminal groups is a slow process.

What would help law enforcement is if the universities and their insurance companies share technical indicators of compromise, logs, and other forensic evidence with authorities. But those conversations happen behind closed doors.

The Insurance Question

Harvard and UPenn almost certainly have cyber insurance. Universities at that level have sophisticated risk management. Cyber insurance typically covers:

- Notification costs (sending letters to affected individuals)

- Credit monitoring services (sometimes offered to breach victims)

- Forensic investigation

- Legal fees

- Regulatory fines and penalties (in some policies)

- Business interruption losses

Cyber insurance doesn't prevent breaches, but it does provide financial relief when they happen. The cost of notifying potentially over two million individuals and providing credit monitoring is substantial. Insurance helps cover that.

What cyber insurance typically doesn't cover is the reputational damage or the loss of trust. That's incalculable and uninsurable.

Technical Prevention: What Could Have Worked

Looking backward is always easier than looking forward, but there are specific technical controls that could have reduced the impact of these breaches.

Email authentication and verification: Both breaches involved compromised email access or email-based social engineering. Implementing DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance) and DKIM (Domain Keys Identified Mail) makes it harder for attackers to spoof university email addresses. During the UPenn breach, hackers sent emails from university addresses. Better email authentication would have made that more difficult.

Enhanced email security: Sandboxing suspicious emails, analyzing links in real-time, and flagging emails from external sources that claim to be from internal addresses can catch phishing attempts. Most sophisticated email security solutions would have caught the phishing emails used in these attacks.

Endpoint detection and response: If the compromised user's computer had EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) software, suspicious activity might have been detected faster. An EDR solution would have seen credential theft or unusual network access and alerted security teams.

Network segmentation: If the alumni database lived on a separate network with restricted access, the initial compromise wouldn't have granted immediate access to that data.

Behavioral analytics: If the system monitored access patterns to the alumni database and flagged unusual bulk exports or unusual access from unexpected locations, the breach might have been detected during the exfiltration phase rather than weeks later.

None of these are silver bullets. Determined attackers with legitimate credentials can still access databases. But these controls would have made the attack harder, longer, or more detectable.

The Attacker's Perspective: How They Likely Did It

While we don't have forensic details, the attack pattern is predictable based on what the universities disclosed.

Initial compromise: Shiny Hunters identified a target within the university (possibly through LinkedIn or other public sources) who had access to systems they wanted. They then conducted research on that person, finding publicly available information, social media accounts, maybe even email addresses from public documents.

Social engineering: They then contacted the target, either by phone (in the voice phishing scenario) or by email (in the social engineering scenario), pretending to be from a trusted source like IT or a partner organization. The message created a sense of urgency or authority that prompted the target to take action.

Credential theft: The target clicked a link that either:

- Took them to a fake login page that captured credentials

- Opened an attachment with malware that stole credentials

- Tricked them into revealing credentials through social engineering

Once the attackers had valid credentials, they had legitimate access. They could log in, navigate the network, and look for data. They likely escalated privileges (getting access beyond what the initially compromised account could access) and then located the alumni database.

Data exfiltration: They extracted the database, likely in chunks to avoid triggering alerts. This phase probably took days or weeks, which means the universities had the attacker on their network for an extended period without detection.

Publishing: Months later, they published the data on their leak site and demanded ransom. When the ransom wasn't paid, they kept the data published as a way to maintain pressure and build reputation.

This entire process is unfortunately common and difficult to defend against if your organization's security culture doesn't emphasize phishing vigilance.

Looking Forward: What Changes After These Breaches

These breaches will probably lead to internal changes at both universities, though those changes won't be announced. You'll see it play out indirectly through security requirements placed on employees and systems.

Both universities will probably increase investment in:

- Security awareness training

- Multi-factor authentication

- Email security

- Endpoint monitoring

- Incident response capabilities

They might also revise their ransom and negotiation policies, their notification procedures, and their incident communication strategies.

Beyond the universities themselves, the higher education sector will probably see increased focus on cybersecurity at conferences, in advisory committees, and in peer-sharing groups. Universities learn from each other's breaches.

The public sector might also see pressure to pass legislation requiring universities to meet certain security standards or to disclose breaches more quickly. These breaches becoming public information creates political pressure for regulation.

For the criminal ecosystem, the success of Shiny Hunters in exploiting these targets will make universities even more attractive. Other groups will attempt similar attacks. The extortion model will continue to work because it does work.

The Broader Cybersecurity Context

These breaches didn't happen in isolation. They're part of a broader trend of increasing data breaches in higher education.

In 2023, the FBI warned specifically about ransomware threats to universities. In 2024, breaches continued at similar rates. The problem is systemic, not episodic.

Part of the issue is that universities are resource-constrained. Harvard and UPenn are well-funded by university standards, but they're not tech companies. They don't have security budgets that compare to Google or Microsoft. They have to make trade-offs between investing in security and investing in research, facilities, and instruction.

Part of the issue is that universities don't generate revenue from security the way tech companies do. A tech company that gets breached loses customers. A university that gets breached might face reputational damage, but students still enroll and donors still give. The financial incentives to invest in security are weaker.

Part of the issue is that universities employ thousands of people with varying technical sophistication. Creating a security-first culture across that many people is difficult.

All of this is fixable, but it requires sustained commitment and investment from university leadership, which might not happen unless there's external pressure from donors, regulators, or insurers.

Real Talk: Is Your Data Safe Anywhere?

These breaches raise a bigger question: is anyone's data safe?

The short answer is that data breaches at major institutions are now common enough that you should assume your data is exposed somewhere. Even if you've never been to Harvard or UPenn, your information is probably in a database that's been breached. You've given it to a school, an employer, a bank, a retailer, a hospital, or some website that went out of business and sold its data.

That doesn't mean you should panic or give up on security. It means you should shift your mindset from "keep my data private" to "assume my data is compromised and protect myself accordingly."

That mindset shift looks like:

- Using unique passwords for important accounts (so if one breach compromises one password, the damage is contained)

- Using a password manager to make unique passwords manageable

- Enabling multi-factor authentication on important accounts

- Monitoring your credit and financial accounts regularly

- Being suspicious of unsolicited contact

- Freezing your credit proactively

These are defensive measures, not preventive measures. They assume the worst and work backward from there.

FAQ

What information was stolen in the Harvard and UPenn breaches?

The stolen data includes alumni information such as email addresses, phone numbers, home and business addresses, event attendance records, donation details, and biographical information related to fundraising and alumni engagement. The data does not appear to include student records or financial information, though the universities didn't explicitly rule out other sensitive data.

How did Shiny Hunters carry out these breaches?

Both breaches used social engineering tactics rather than sophisticated technical exploits. UPenn's breach came through social engineering where attackers impersonated trusted sources to trick employees into granting access. Harvard's breach involved voice phishing, where hackers called targets and convinced them to click malicious links or open attachments that captured credentials. Once attackers had legitimate credentials, they accessed the universities' systems and extracted the data.

What should I do if I'm an alumnus of Harvard or UPenn?

Monitor your financial accounts for unusual activity, place a security freeze on your credit with all three major credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union), check your credit reports regularly at Annual Credit Report.com, and be suspicious of unsolicited contact from anyone claiming to be from the university. Save copies of any breach notification emails you receive in case questions arise later.

Why didn't the universities pay the ransom?

Both universities likely followed established security policies recommending against ransom payment, even though paying might have prevented data publication. Paying ransom funds criminal operations, creates incentives for future attacks, and doesn't guarantee that data won't be published anyway. The universities probably had cyber insurance to cover notification costs and other expenses related to the breach response.

Is Shiny Hunters still active?

Yes, Shiny Hunters continues to operate their extortion website and claim responsibility for new breaches. The group has been active for years and operates out of a jurisdiction without extradition treaties, making prosecution difficult. Law enforcement agencies monitor the group's activities, but international cybercriminal groups are challenging to prosecute.

What can other organizations learn from these breaches?

Organizations should prioritize security awareness training that uses realistic, role-specific scenarios rather than generic training. Implement multi-factor authentication broadly across systems, segment networks so that compromising one system doesn't grant access to everything, and establish detection mechanisms for unusual database access patterns. Most importantly, assume that attackers will eventually breach your network and focus on limiting what they can do once inside.

How does cyber insurance factor into these breaches?

Universities like Harvard and UPenn almost certainly have cyber insurance that covers notification costs, credit monitoring services, forensic investigation, and legal fees. Cyber insurance provides financial relief for the operational costs of a breach but doesn't prevent breaches from occurring or cover reputational damage, which is incalculable and uninsurable.

Will there be legal consequences for Shiny Hunters?

Law enforcement agencies including the FBI are likely monitoring Shiny Hunters' activities, but prosecution of international cybercriminal groups is slow and difficult. These groups often operate from countries without extradition treaties, and investigations require gathering evidence, attribution, and coordination with international partners. Active prosecutions typically focus on the most significant threats to national security or critical infrastructure.

The timeline shows that both Harvard and UPenn experienced breach events in November 2025 and February 2026, highlighting the delay between breach notification and data publication. Estimated data.

Key Takeaways

These breaches matter because they're emblematic of a broader trend. Universities are increasingly targeted by sophisticated criminal groups. Social engineering remains the most effective attack vector. Data theft for extortion is becoming the dominant criminal business model. And once data is published, it's in the wild forever.

The universities did what they were supposed to do: they disclosed the breaches, notified affected individuals, and refused to pay ransom. But notification isn't protection. Being affected by these breaches means being vigilant about financial and identity security for years to come.

For everyone else watching this unfold, the lesson is clear: your data is probably compromised somewhere. You just don't know where yet. Plan accordingly.

Social engineering is the most common attack vector, accounting for 50% of breaches, followed by phishing and malware. Estimated data based on recent trends.

Related Articles

- OpenClaw AI Assistant Security Threats: How Hackers Exploit Skills to Steal Data [2025]

- ShinyHunters SSO Scams: How Vishing & Phishing Attacks Work [2025]

- Infostealer Malware Now Targets Mac as Threats Expand [2025]

- Apple Pay Unusual Activity Scam: How to Spot Fake Messages [2025]

- ExpressVPN Valentine's Day Deal Guide: Save Up to 81% [2025]

- Minecraft Server Security Guide: Keep Your Server Safe [2025]

![Harvard & UPenn Data Breaches: Inside ShinyHunters' Attack [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/harvard-upenn-data-breaches-inside-shinyhunters-attack-2025/image-1-1770228452581.jpg)