Introduction: When Official Narratives Collide with Evidence

On a Saturday afternoon in Minneapolis, a confrontation between federal immigration agents and a man ended in gunfire. Within minutes, not hours, the story had fractured into competing narratives. By the time the smoke cleared, the victim had been rebranded as a terrorist, an assassin, and a radical. The evidence, meanwhile, told a different story.

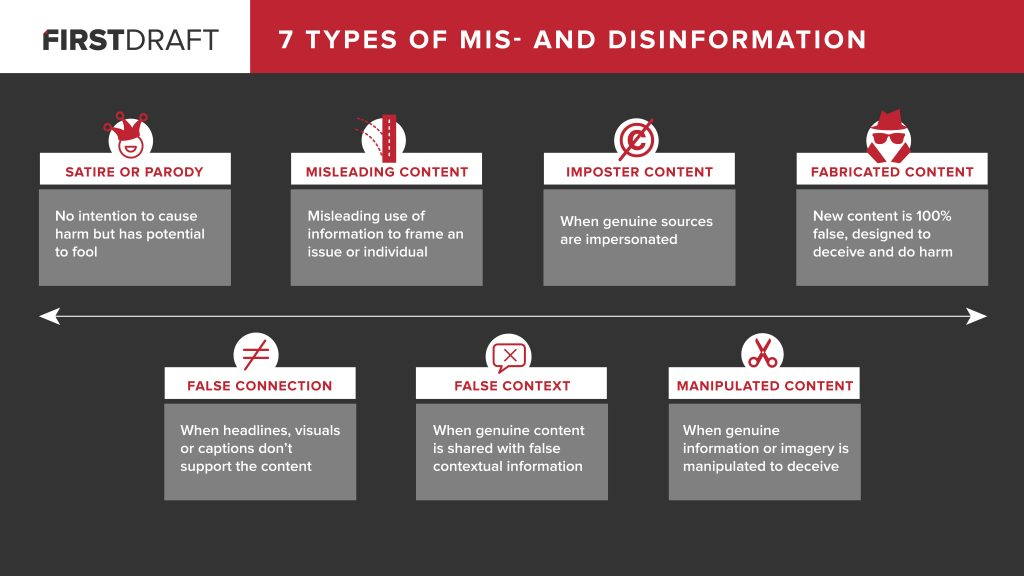

This isn't about taking political sides. This is about what happens when official institutions make rapid claims, when those claims spread through digital networks at scale, and when video evidence becomes another battleground in a larger information war. The shooting of Alex Pretti on a Saturday in Minneapolis became a case study in how modern disinformation operates, not as a conspiracy whispered in dark corners, but as a coordinated strategy amplified by the highest levels of government and weaponized by networks of influencers with millions of followers.

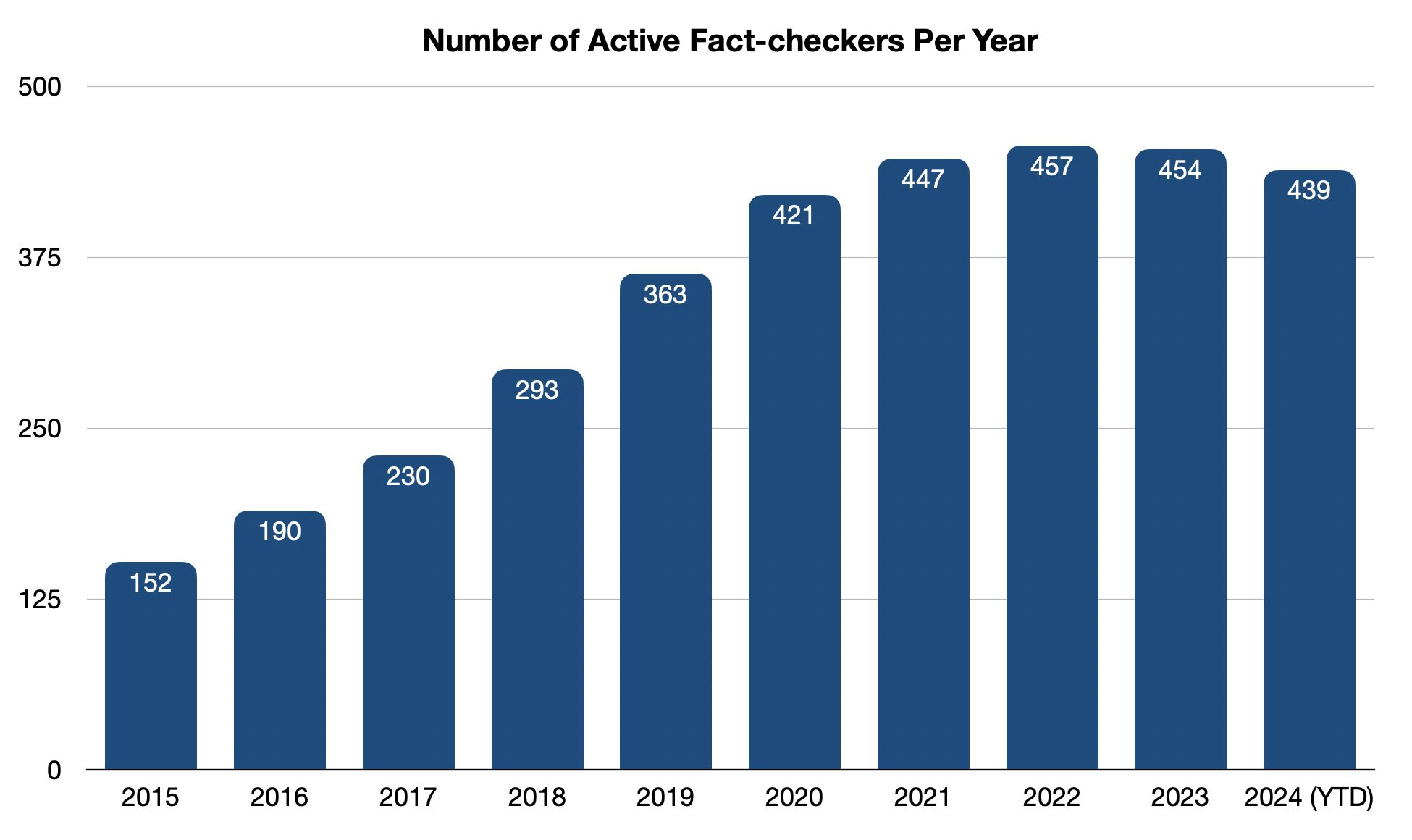

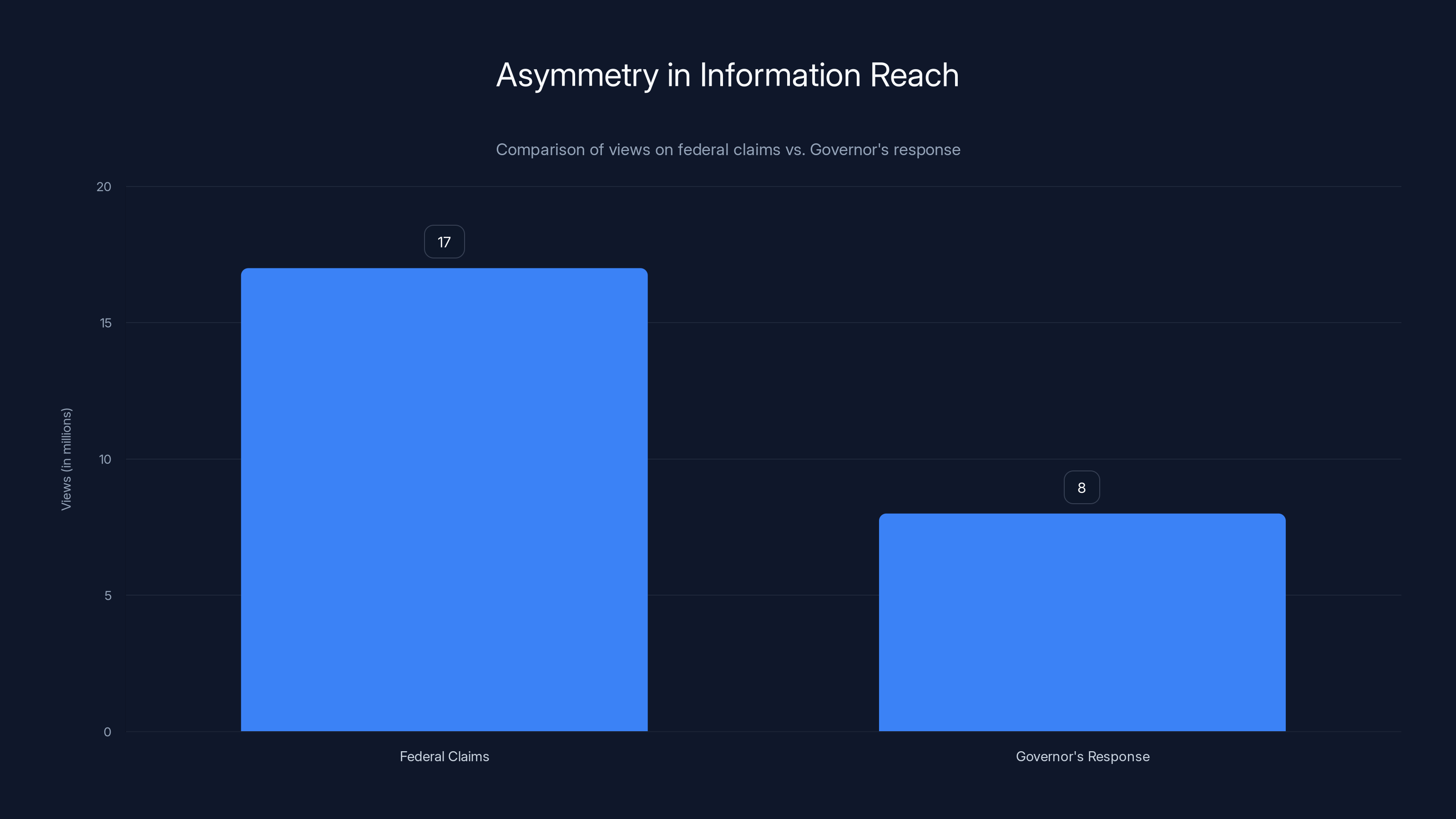

What makes this case particularly instructive is the speed. The initial claims from federal authorities were contradicted by publicly available video evidence within hours. Yet those claims reached 17 million people. The corrections, the clarifications, the actual video footage showing what happened, circulated through smaller channels to smaller audiences. This is the asymmetry of modern information warfare: false claims are jets, corrections are bicycles.

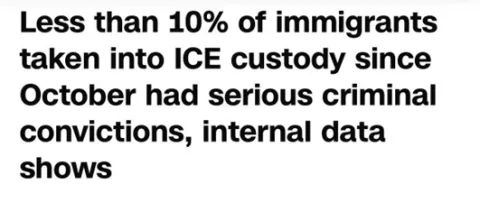

The killing of Pretti came just 17 days after another fatal shooting involving Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Renee Nicole Good, also 37 years old, had been killed two-and-a-half weeks earlier. Both incidents raised questions about federal immigration enforcement tactics. Both incidents also triggered immediate narrative wars. Understanding how these narratives form, who amplifies them, and why they spread tells us something fundamental about American politics in 2025.

This examination looks beyond the specific incident to understand the mechanics of modern disinformation: how institutions make claims, how networks amplify them, what breaks through, and what gets buried. The Minneapolis shooting is the case study. The process itself is the story.

TL; DR

- Federal authorities made unverified claims about a shooting victim within hours, labeling him a terrorist without supporting evidence

- Video evidence contradicted official narratives, showing the victim holding a phone, not a weapon, when approached by officers

- Disinformation spread to 17 million people through official DHS accounts and right-wing influencers before corrections were available

- Institutional actors amplified false claims from the highest levels of government, including the White House and Cabinet secretaries

- Asymmetric information flows mean corrections reach far fewer people than initial false claims

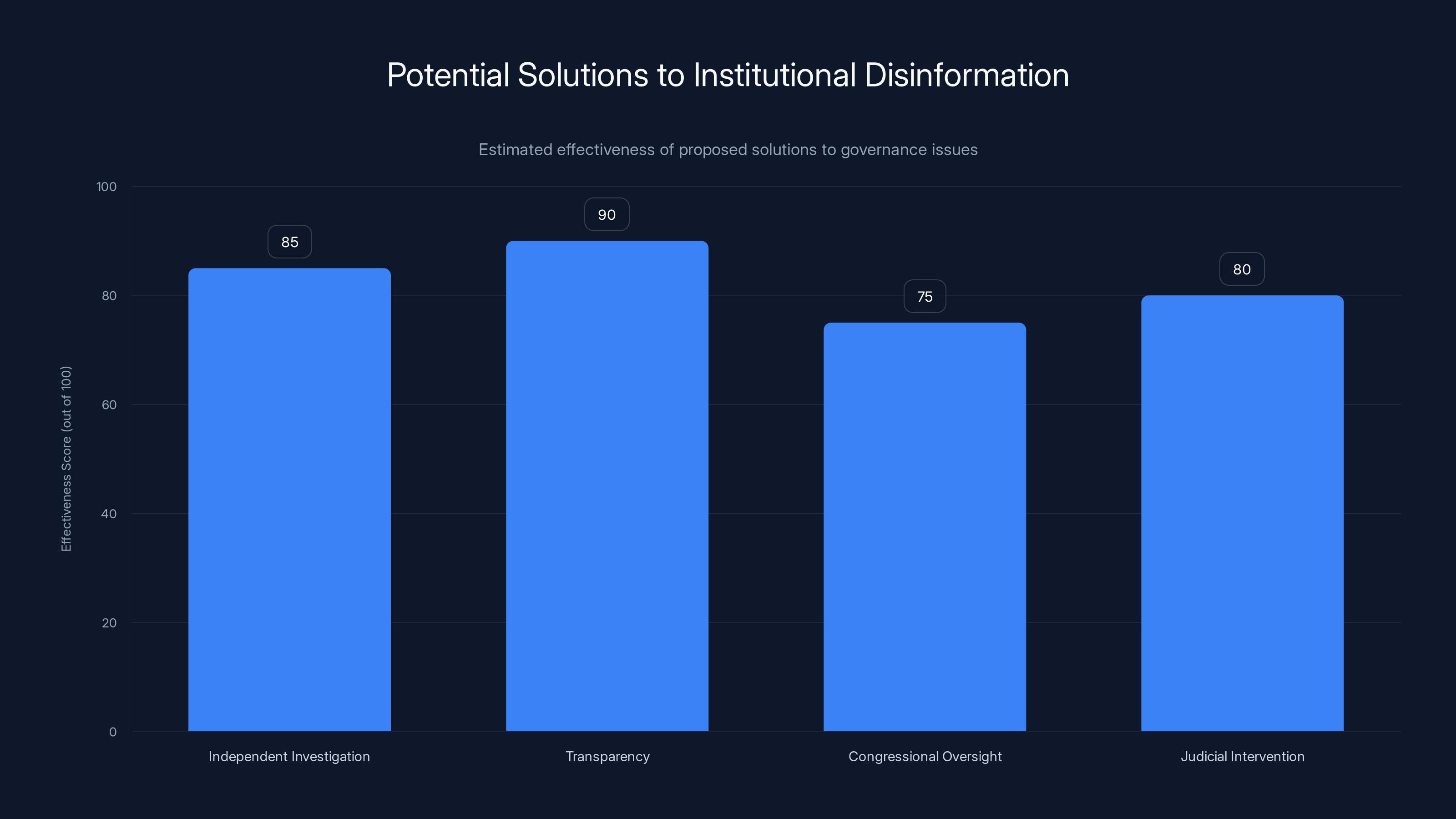

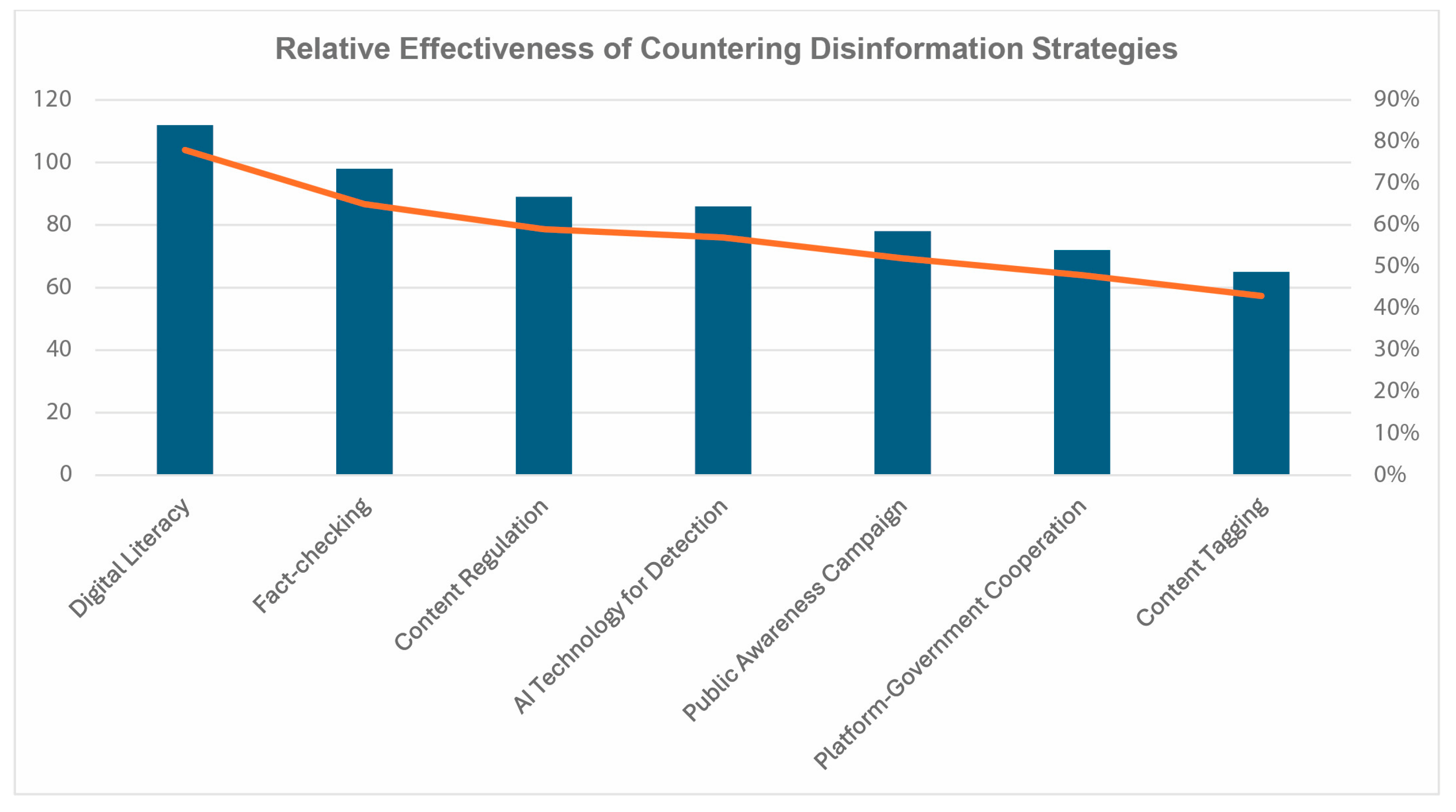

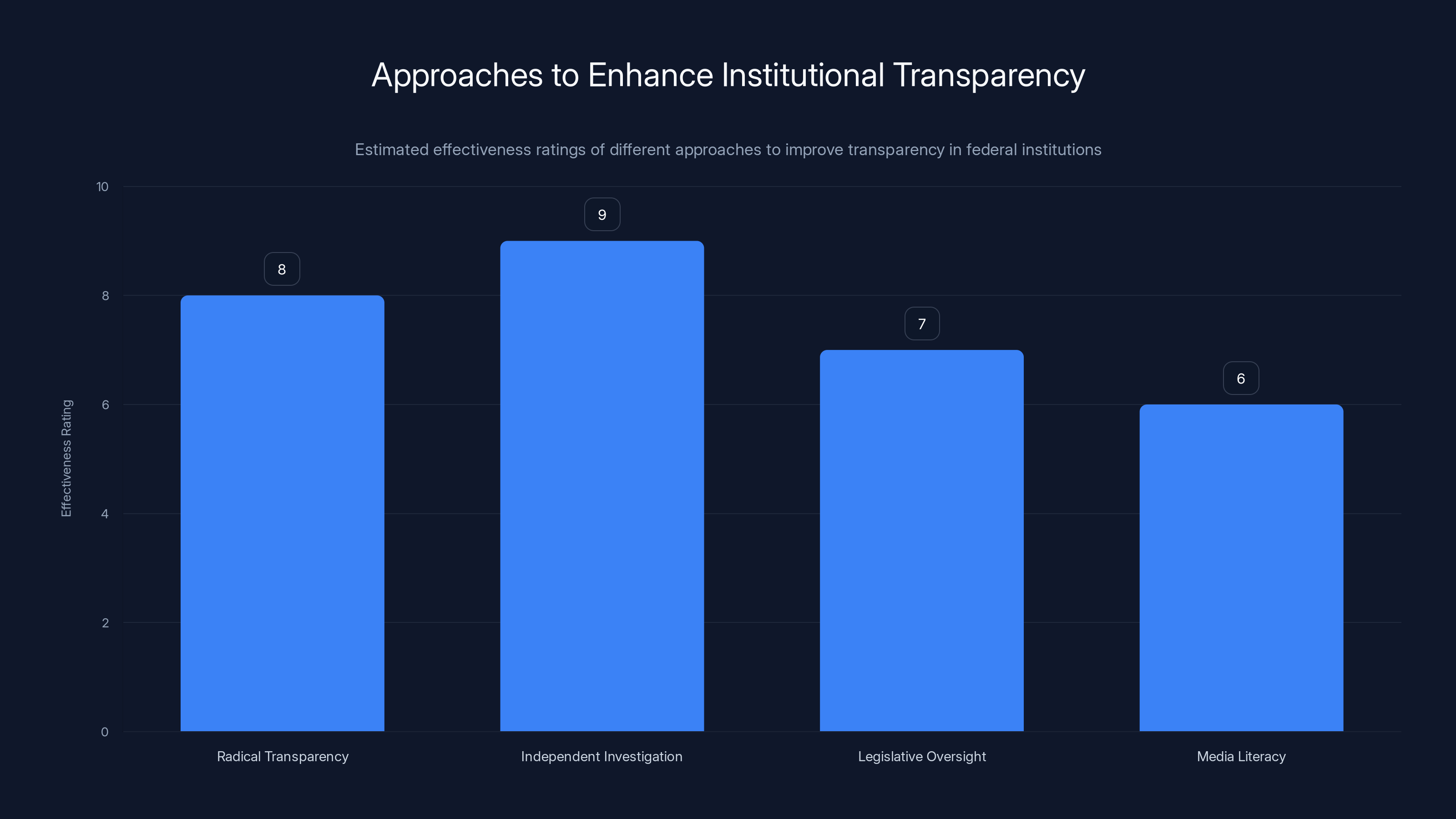

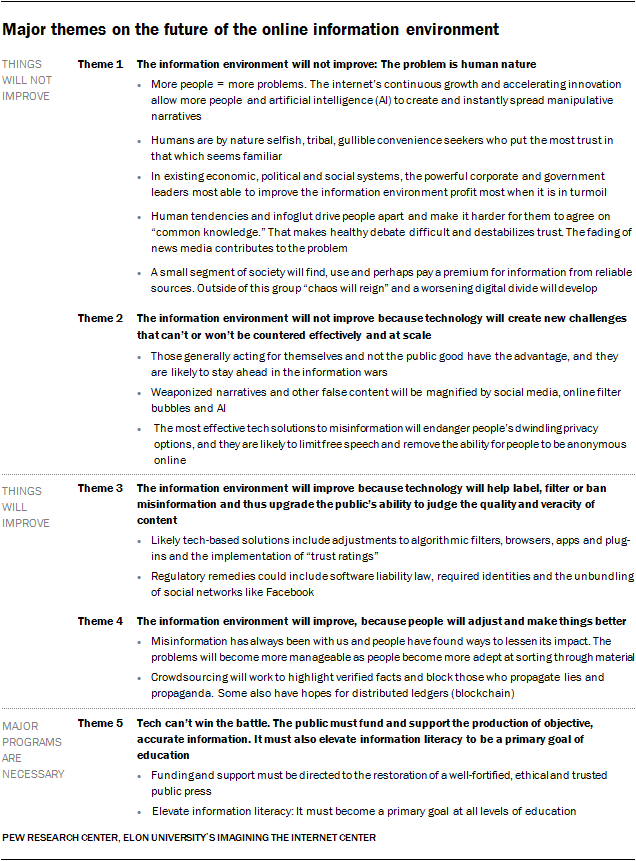

Transparency is estimated to be the most effective solution in addressing institutional disinformation, followed closely by independent investigations. Estimated data.

The Timeline: How Claims Become Orthodoxy in Minutes

Timelines matter. They show you where information originates, how it moves, and at what point it becomes "common knowledge" regardless of accuracy.

The shooting happened on Saturday. Within minutes, federal authorities were on the scene conducting what would become the official investigation. Within an hour, the narrative framework was set. Greg Bovino, the Border Patrol commander overseeing federal operations in Minneapolis, held a press conference.

At that press conference, Bovino made specific claims: Pretti had approached officers with a 9mm handgun. He had resisted disarmament. He was carrying two loaded magazines. He had no identification. Most critically, Bovino claimed that Pretti intended to "massacre law enforcement." The agent who shot him, Bovino suggested, had acted in clear self-defense, a trained professional responding to a legitimate threat.

These weren't vague assertions. They were granular details that sounded authoritative because they came from someone with official credentials. A person watching the press conference would hear specific numbers, specific claims, all delivered with the confidence of an official in command of the scene.

The Department of Homeland Security posted these claims to X (formerly Twitter) within hours. By the time most Americans woke up the next morning, this narrative had been amplified to 17 million people. The DHS post didn't include caveats. It didn't say "preliminary reports indicate" or "subject to investigation." It stated the claims as established fact.

Right-wing media outlets picked up the narrative immediately. The Post Millennial published a story with the headline: "Armed agitator Alex Pretti appeared to want 'maximum damage' and to 'massacre' law enforcement when shot by BP in Minnesota." Other outlets followed. The story metastasized across digital networks with remarkable speed.

Then came the political amplification. President Trump posted on Truth Social, blaming Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey and Minnesota Governor Tim Walz for "inciting insurrection" with their rhetoric. Vice President JD Vance backed up the criticism. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth added his voice, calling critics of the shooting "lunatics." Trump's homeland security adviser, Stephen Miller, went further still, using words like "assassin" and "terrorist" to describe the shooting victim.

At each level of amplification, the original claims became more embedded as established fact. What had started as assertions from a Border Patrol commander became government position. What had become government position became media orthodoxy. By Saturday evening, you would have needed to actively seek out contradictory evidence to know that the official narrative was disputed.

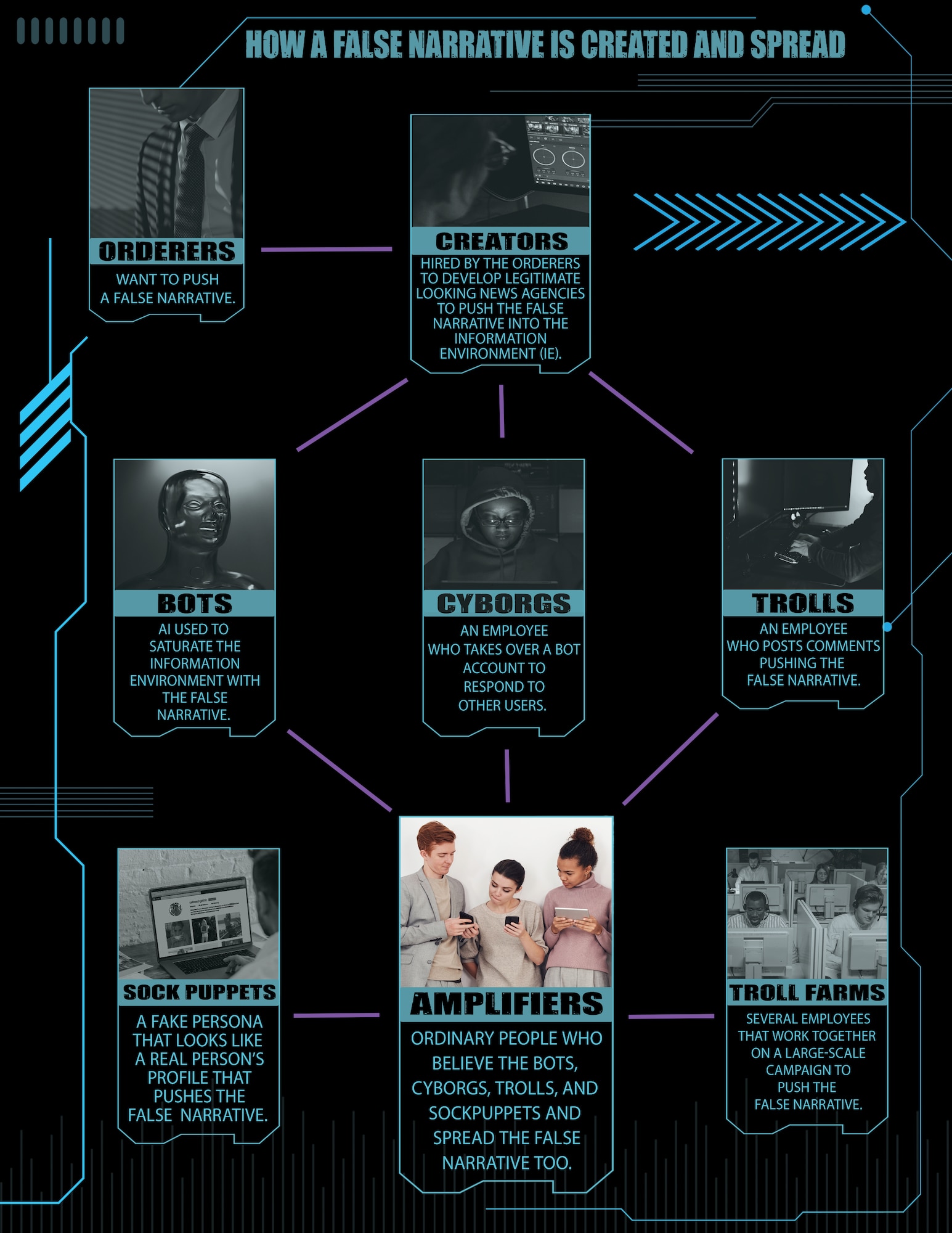

Let me be clear about something: this isn't a mistake. This is a process. Claims are made, amplified, and repeated until they achieve the status of common knowledge. Evidence that contradicts those claims circulates through smaller channels, reaches smaller audiences, and rarely breaks through the noise ceiling of the initial narrative.

The Federal Claims: Building Credibility Through Specificity

When officials make claims, they use specificity as a credibility marker. The more granular the details, the more authoritative the statement sounds. This is basic information architecture. Our brains interpret detail as evidence of knowledge.

Greg Bovino's press conference included exactly this kind of specificity: a 9mm handgun, two loaded magazines, no identification. These details were delivered in official language by someone with official authority. A person hearing these claims would reasonably assume they were based on investigation, evidence, and professional assessment.

Here's the problem: some of these claims were made before standard investigative procedures would have been completed. Determining whether someone had identification on them, whether they were carrying specific ammunition, whether they intended to "massacre law enforcement," these conclusions typically require investigation. Crime scenes are chaotic. Initial reports are almost always incomplete and frequently wrong.

But the speed required to respond in the modern media environment means that officials face pressure to make claims before investigation is complete. Say nothing, and you lose narrative control. Make claims early, and you risk making claims that are contradicted by evidence. In this case, federal authorities chose the second path.

The 9mm handgun claim became central to the entire narrative. It was the linchpin that made self-defense a plausible story. Without it, the federal shooting of someone approaching officers becomes much harder to justify. With it, Bovino could frame the incident as a trained officer responding to an armed threat.

But here's what the videos showed: multiple angles of the confrontation, captured by bystanders. In these videos, Pretti is clearly holding a phone, not a gun, when federal officers approach him. The New York Times analyzed the video frame by frame. Bellingcat, an open-source investigation group, did the same. Both concluded that Pretti was holding a phone. That phone, when examined, was recovered as evidence from the scene.

This is the critical gap: federal authorities made specific claims about a 9mm handgun. Video evidence showed no gun being visible when officers approached. How do these two facts coexist? Either the gun appeared between the video timestamp and the shooting (hard to see in the footage), or the claim was made without being grounded in what actually happened at the moment officers engaged.

This matters because it undermines the self-defense narrative. If Pretti wasn't holding a visible weapon when officers approached and tackled him, then the shooting becomes something else entirely. Not self-defense against an armed threat, but a use of lethal force during an apprehension.

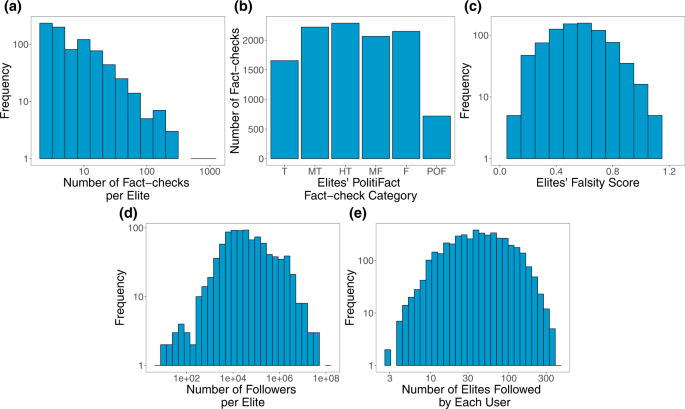

Estimated data shows how claims about an incident can reach millions within hours, becoming widely accepted as common knowledge.

What the Videos Actually Showed: Evidence Versus Narrative

Bystander video is the truth serum of modern incidents. It's unedited, real-time, and hard to rationalize away. Yet it's also subject to interpretation, framing, and the limits of any single camera angle.

In this case, multiple videos existed from different angles. They were posted on social media within hours of the incident. The videos showed a street confrontation, federal officers, and the moment of the shooting.

What they clearly showed was Pretti on the ground, being apprehended. What they showed with less clarity was what happened in the moments immediately before the shooting. This ambiguity is important. It's where narrative fills the gaps that video doesn't answer.

But the videos also showed something that contradicted the main federal claim: before officers tackled Pretti, he was holding a phone, not a gun. Multiple angles confirmed this. Analysis by investigative outlets confirmed this. This detail alone undermined the self-defense narrative.

One video showed Pretti approaching the federal officers. Another showed him on the ground. The sequence suggested that Pretti had approached officers, that officers had tackled him, and that during the apprehension, the shooting occurred.

Here's where context from bystanders becomes crucial. Those who filmed the incident also spoke about what happened immediately before. According to accounts, Pretti had approached officers because a woman nearby had been pepper sprayed by immigration agents. He was trying to help. This detail, reported by the BBC and verified through witnesses, changes the context entirely.

Pretti wasn't approaching officers as a threat. He was approaching them as someone trying to help someone else. This reframes the entire interaction. Not a man approaching armed federal agents with hostile intent, but a person trying to intervene on behalf of someone he perceived as being harmed.

The Minneapolis Police Chief, Brian O'Hara, made a crucial statement during a separate press conference: he believed Pretti was "a lawful gun owner with a permit to carry." This detail, buried in press coverage but confirmed by police investigation, matters because it undercuts the federal narrative about Pretti as a reckless actor. If he was a lawful gun owner with proper permits, the story of him as an anarchist or radical becomes harder to maintain.

So what we have is a collision of narratives: the federal narrative (armed man, immediate threat, self-defense) versus what video evidence and police investigation suggested (lawful gun owner, trying to help someone, apprehended by federal officers, shot during the apprehension). Both can be partially true. Both can be partially constructed. The question is which narrative gets amplified and which gets buried.

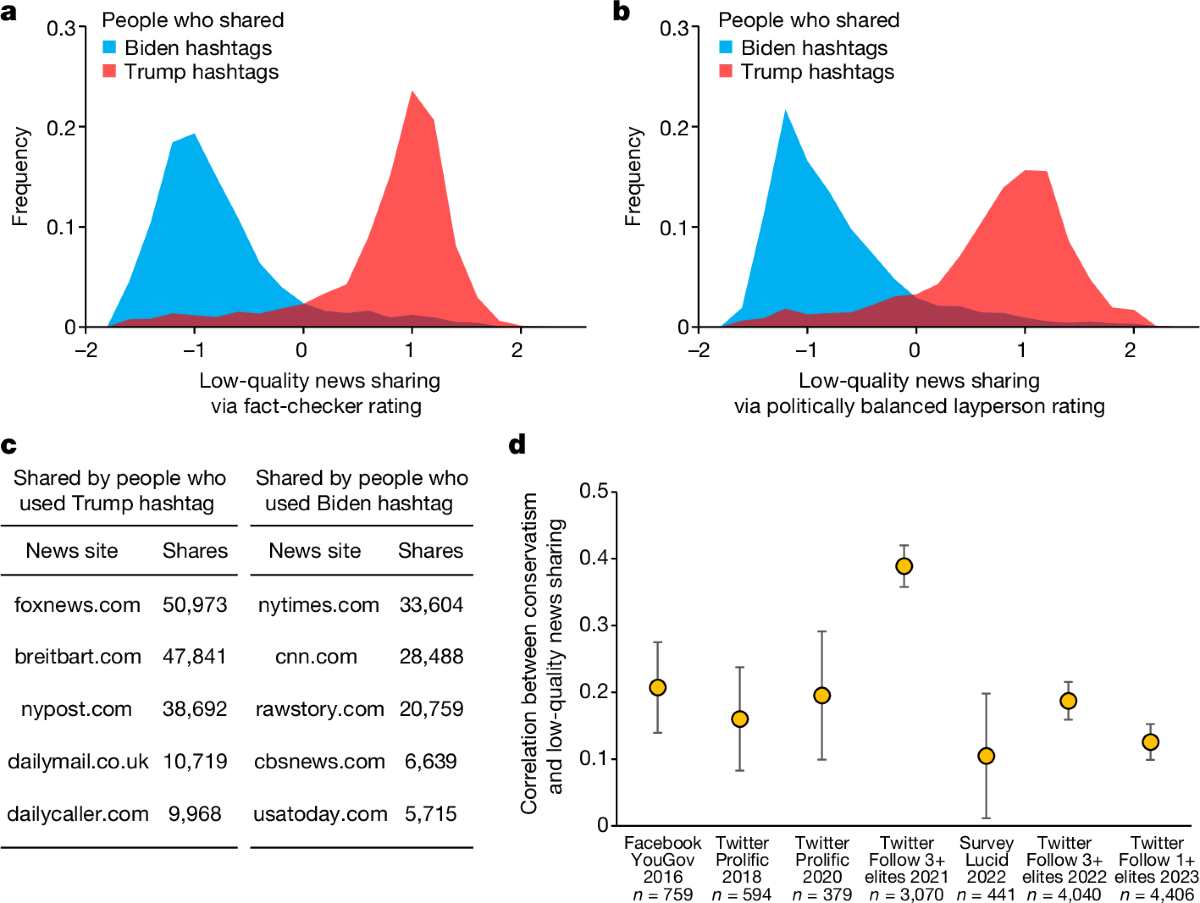

The Influencer Network: Amplifying Official Claims

Right-wing influencers weren't inventing claims in this case. They were amplifying official claims. But they were doing it with reach that dwarfed traditional media.

Nick Sortor, one of a group of influencers camped out in Minneapolis to cover Immigration and Customs Enforcement operations, made claims on X that were demonstrably false: he referred to Pretti as an "illegal alien" and claimed he "was armed with a gun and attempted to PULL IT on agents." Pretti was a U.S. citizen born in Illinois. Video evidence showed him holding a phone, not attempting to pull a gun.

Yet Sortor's posts reached hundreds of thousands of people. His account has millions of followers. The false claim was amplified at scale.

Jack Posobiec, another right-wing influencer with close ties to the White House, framed the incident as a matter of law: "It is most certainly illegal to disrupt federal law enforcement operations and doing so while armed is not only unlawful, it is a good way to get shot." The implication being that Pretti had disrupted federal operations while armed and therefore deserved the consequences.

But this framing accepted the federal narrative uncritically. It didn't engage with video evidence. It didn't acknowledge the account from witnesses about what Pretti was doing before he was apprehended. It simply accepted the frame as given and elaborated on it.

What's important about influencers is their structural position. They're not traditional journalists with editorial oversight or fact-checking processes. They're not bound by journalistic standards. They're entrepreneurs with audiences, financial incentives tied to engagement, and algorithmic distribution that rewards controversy. In this space, the truth is one product among many. It's the one that wins if it's more engaging than its competitors.

In this case, the federal narrative was engaging. It had drama: a potential threat to law enforcement. It had moral clarity: good guys (federal agents) versus bad guys (the man with the gun). It had political implications: local leadership failing to support federal law enforcement. All of these elements made it a more engaging story than the more ambiguous reality.

Influencers, by and large, went with the engaging story. Some, like Tim Pool, did acknowledge that the federal narrative might be exaggerated. But most amplified it. The result was a network effect: official claims were picked up by media outlets, amplified by influencers, spread through social networks, and achieved the status of common knowledge among their audience.

The people in that audience trusted these influencers because they perceived them as anti-establishment. They were rebels against mainstream media. When these rebels reported what federal authorities said, it carried the impression of validation. If even the anti-establishment people agree with the federal authorities, then it must be true.

This is a sophisticated information operation, but importantly, it doesn't require coordination. Influencers simply have financial and reputational incentives to amplify engaging content. Federal authorities have incentives to control narrative. When those incentives align, the result is asymmetric information warfare.

The White House Response: Institutionalizing the Narrative

What made this incident different from typical police shootings was the rapid response from the very highest levels of government. The President posted on Truth Social within hours. The Vice President and Cabinet secretaries added their voices. The homeland security adviser used words like "terrorist" and "assassin." This wasn't a typical incident where federal authorities made claims that were then picked up by political figures. This was political figures using their platforms to amplify federal authorities' claims.

Trump's post blamed Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey and Minnesota Governor Tim Walz for "inciting insurrection" with their rhetoric. This was a remarkable claim. What rhetoric had they engaged in that amounted to inciting insurrection? They had called for investigation. They had expressed concern about federal tactics. Neither of these positions constitutes incitement by any standard definition.

But Trump's post served another function: it provided political cover for the federal narrative. If the President of the United States is blaming local leadership for the incident, then the narrative is shifted away from federal conduct and onto local governance. It becomes a story about whether local leaders are supporting or obstructing federal law enforcement, rather than a story about whether federal law enforcement used appropriate force.

Vice President JD Vance reinforced this narrative, claiming that ICE agents wanted to "work with local law enforcement" and that local leadership had "refused" their requests. This claim was made without evidence. It reframed the incident as a matter of coordination failure rather than a question about whether the shooting was justified.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth went further, calling critics "lunatics" and dismissing local leadership. His statement, "ICE > MN," was a remarkable assertion: federal immigration enforcement is superior to state governance. This is a direct claim about the hierarchy of authority that's worth noting.

Stephen Miller, Trump's homeland security adviser, used even more inflammatory language. "Assassin," "terrorist." These are words designed to push the conversation beyond the facts of the incident into a realm of pure moral valuation. If Pretti was a terrorist, then any response to him was justified. If he was an assassin, then stopping him was self-preservation.

What's striking about these responses is their coordination without apparent coordination. Each statement reinforced the others. Each statement elevated the incident from a local police matter to a national political issue. Each statement shifted the conversation from questions about federal conduct to assertions about Pretti's character.

By Saturday evening, the narrative was consolidated at the highest levels of government. The President, Vice President, Cabinet secretaries, and White House advisers were all repeating the same core claims: Pretti was a threat, federal officers acted appropriately, local leadership was at fault. This is institutional amplification.

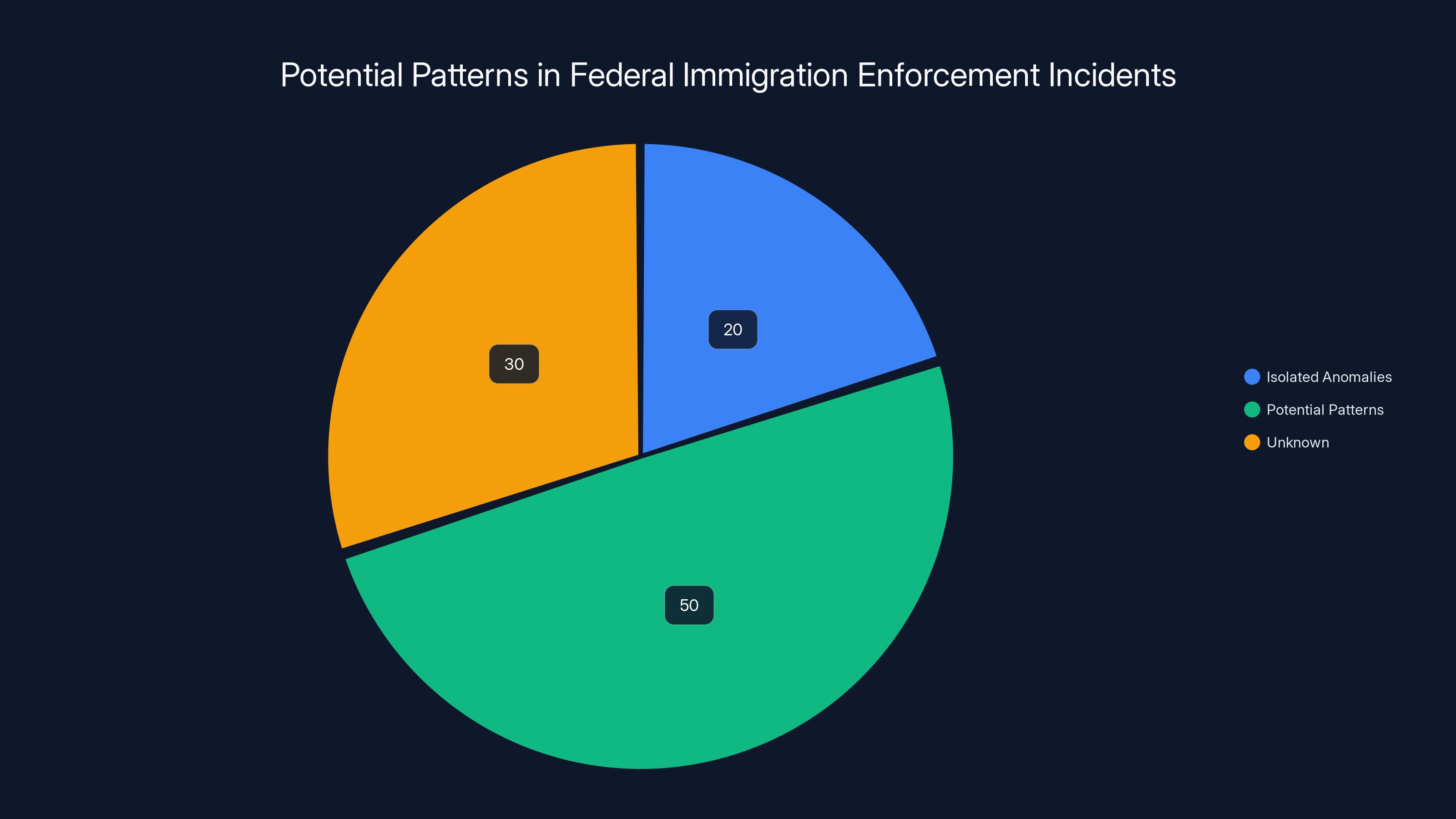

Estimated data suggests that half of the incidents might indicate potential patterns of systemic issues within federal immigration enforcement, highlighting the need for comprehensive data tracking.

The Victim's Background: Who Was Alex Pretti

The original narrative made Pretti into a symbol: a radical, an anarchist, a terrorist. The actual biography was different.

Pretti was 37 years old. He was an American citizen, born in Illinois. He worked as a registered nurse in the Department of Veterans Affairs, according to colleagues who spoke to journalists. He had no criminal record, according to family members. He was a lawful gun owner with a permit to carry, according to police investigation.

None of these facts made it into the federal narrative. Instead, the narrative focused on the moment of confrontation: the gun, the magazines, the supposed intention to harm law enforcement. The context of his life, his employment, his legal status, all of this was erased in favor of a narrative that made him a type rather than a person.

This matters because it shows how disinformation doesn't operate through outright falsehood alone. It operates through erasure. The federal narrative didn't claim Pretti had a criminal record (he didn't). It didn't claim he was an illegal immigrant (he was a citizen). It didn't claim he was a known extremist (there's no evidence he was). Instead, the narrative simply omitted the context that would make him legible as a regular person.

By omitting context, the federal narrative made him available for reinterpretation as whatever political opponents needed him to be. He became a symbol of the anarchist left, of antifa, of radicalism. Influencers could project onto him whatever meaning served their narrative.

This is a form of information violence. Not violence through false statements, but violence through selective truth. By choosing which true facts to emphasize and which to omit, the narrative becomes something that contradicts the facts without technically lying about them.

The comparison to Renee Nicole Good, the other shooting victim 17 days earlier, is instructive. Good was a mother of three, also 37 years old. Also killed by federal immigration enforcement. Also had questions about the circumstances raised almost immediately. Yet she received a fraction of the political attention that Pretti's case received, partly because the federal narrative in her case was less contested.

Two deaths, two families grieving, two shootings that raised questions about federal law enforcement tactics. But one became a national political issue while the other remained largely local. The difference wasn't the facts of the cases. It was the political significance assigned to them.

Institutional Responses: When Local and Federal Conflict

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz said something remarkable during a press conference. He called the federal narrative "nonsense." He stated directly that "Minnesota's justice system will have the last word" on the incident. He added a crucial statement: "the federal government cannot be trusted with this investigation."

This is the moment where the incident became a conflict between institutional authorities. This wasn't about local police versus federal law enforcement. It was about state government declaring that it didn't trust the federal government to investigate its own actions.

Walz's response was notable partly because it was the opposite of what the Trump administration expected. The Trump administration assumed that federal authority would be accepted as legitimate. Instead, the governor of the state where the incident occurred directly challenged the federal narrative.

Minneapolis Police Chief Brian O'Hara held his own press conference, providing information that contradicted or complicated the federal narrative. He stated that information about what led up to the confrontation was limited, a striking contrast to Greg Bovino's claims of having a "full assessment." O'Hara also confirmed that Pretti was a lawful gun owner with a permit to carry, a detail that undermined the narrative of him as a reckless actor.

What we see here is a failure of institutional coordination. In previous incidents, federal law enforcement claims have gone largely uncontested by state and local authorities. The local police chief would agree, or stay silent. The local governor would defer to federal expertise. In this case, both actively disputed the federal narrative.

Why? Several possibilities. First, the federal narrative was too obviously contradicted by video evidence and preliminary investigation. Second, the state had its own reputation at stake. If the federal narrative was false, then the state had been accused of not supporting law enforcement when in fact state and local law enforcement disagreed with the federal shooting. Third, the political calculation had changed. A Democratic governor could gain political capital by opposing federal immigration enforcement, something that's not available to local leaders in other regions.

The institutional conflict exposed something important: federal authority isn't automatically accepted, and federal claims aren't automatically true just because they come from federal actors. When those claims collide with evidence and with competing institutional actors, the narrative can fracture.

But this fracturing happens unevenly. By the time Governor Walz made his statement, the federal narrative had already reached 17 million people through DHS social media. His statement reached a fraction of that audience. The asymmetry means that even if the state wins the institutional conflict, the population at large may never know it.

The Mechanics of Narrative Control: Speed as a Weapon

Here's a key observation: the federal narrative didn't win because it was true. It won because it was fast. The Department of Homeland Security posted to X with authority and specificity before video evidence had been widely circulated, before investigation was complete, before local authorities had offered competing claims.

Speed is a weapon in information warfare. Not because speed guarantees accuracy, but because being first allows you to set the frame through which all subsequent information is interpreted. Once the public has a story, new information is filtered through that story. If the story says Pretti had a gun and intended to massacre law enforcement, then evidence of him holding a phone gets reinterpreted: maybe he had a gun elsewhere. Maybe the videos were edited. Maybe the people holding the phone and the person who had the gun are different people. The frame becomes sticky.

News organizations, meanwhile, face their own pressures. When federal authorities make official claims, there's institutional pressure to report those claims as news. "Federal authorities claim X" is a news story. "Federal authorities' claims are disputed" is also a news story, but it requires additional reporting. It requires reaching out to the state, to lawyers, to forensic experts. It requires time.

In the hours immediately after the incident, most news organizations simply reported what federal authorities said. It wasn't until investigation progressed and alternative sources became available that the competing narrative could be reported.

By that time, the first narrative was already embedded. Studies of social media show that corrections to false claims reach only a fraction of the audience that received the original false claim. Even people who see the correction often don't update their beliefs. They interpret the correction as an attack on the original source rather than as evidence that the original source was wrong.

This is how institutional disinformation works. It's not a conspiracy to deceive, though that can happen. It's a series of incentives that push toward speed over accuracy, toward institutional self-protection over transparency, toward narrative control over evidence-based reporting. The result is asymmetric information flows that privilege official claims and disadvantage corrections.

Independent investigation is estimated to be the most effective approach to enhance transparency, followed closely by radical transparency. Legislative oversight and media literacy also play significant roles. Estimated data.

Right-Wing Criticism: Heterodoxy Within the Coalition

Not everyone on the right accepted the federal narrative uncritically. This is worth noting because it shows that political tribalism isn't absolute, even when media narratives suggest it is.

Tim Pool, a right-wing podcaster, labeled Pretti "a radicalized leftist" without providing any evidence. But then Pool disagreed with the core federal claim about Pretti's intentions. "There's no reason to think he was trying to massacre LEOs," Pool wrote, using the abbreviation for law enforcement officers. In Pool's telling, Pretti might have been politically wrong, but he wasn't the existential threat that federal authorities claimed.

Dave Smith, a comedian who endorsed Trump in 2024, went further. Smith made a remarkable statement: "I'm an immigration restrictionist. I believe that we have the right to remove any and all people who entered our country illegally. Also, ICE is out of fucking control. A bunch of pussies, drunk on power going around intentionally escalating violent interactions and intimidating US citizens."

Smith's statement reveals something important: you can support restrictive immigration policies while also believing that federal enforcement is behaving badly. These positions don't have to be contradictory. Yet the broader political narrative tried to make them contradictory, as if criticism of federal tactics was inherently criticism of immigration enforcement.

Smith identified something crucial: the pattern of behavior. This wasn't the first time federal immigration agents had engaged in a shooting. It was the second time in 17 days. Both victims were citizens. Both incidents raised questions about whether federal agents were escalating situations unnecessarily.

For someone like Smith, who actually supports immigration enforcement, this pattern poses a problem. It suggests that the federal agency responsible for that enforcement is behaving in ways that undermine the broader political goals. If ICE shootings of citizens are common enough to happen twice in three weeks, then ICE is either poorly trained, poorly supervised, or poorly organized. All of these conclusions are bad for the political project of immigration enforcement.

This heterodoxy within the right-wing coalition is important because it shows that the federal narrative didn't achieve total consensus, even among the political allies of the Trump administration. There was space for criticism. That space was smaller than it would have been in a more ideologically open environment, but it existed.

Yet that criticism didn't change the broader narrative. By the time Pool and Smith offered their critiques, the federal narrative was already embedded in the broader information ecosystem. Their criticism circulated to their own audiences, but didn't break through to the larger public conversation.

The Digital Asymmetry: Why Corrections Fail

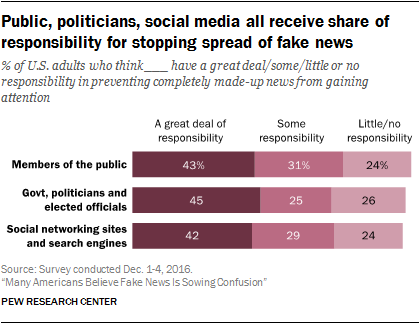

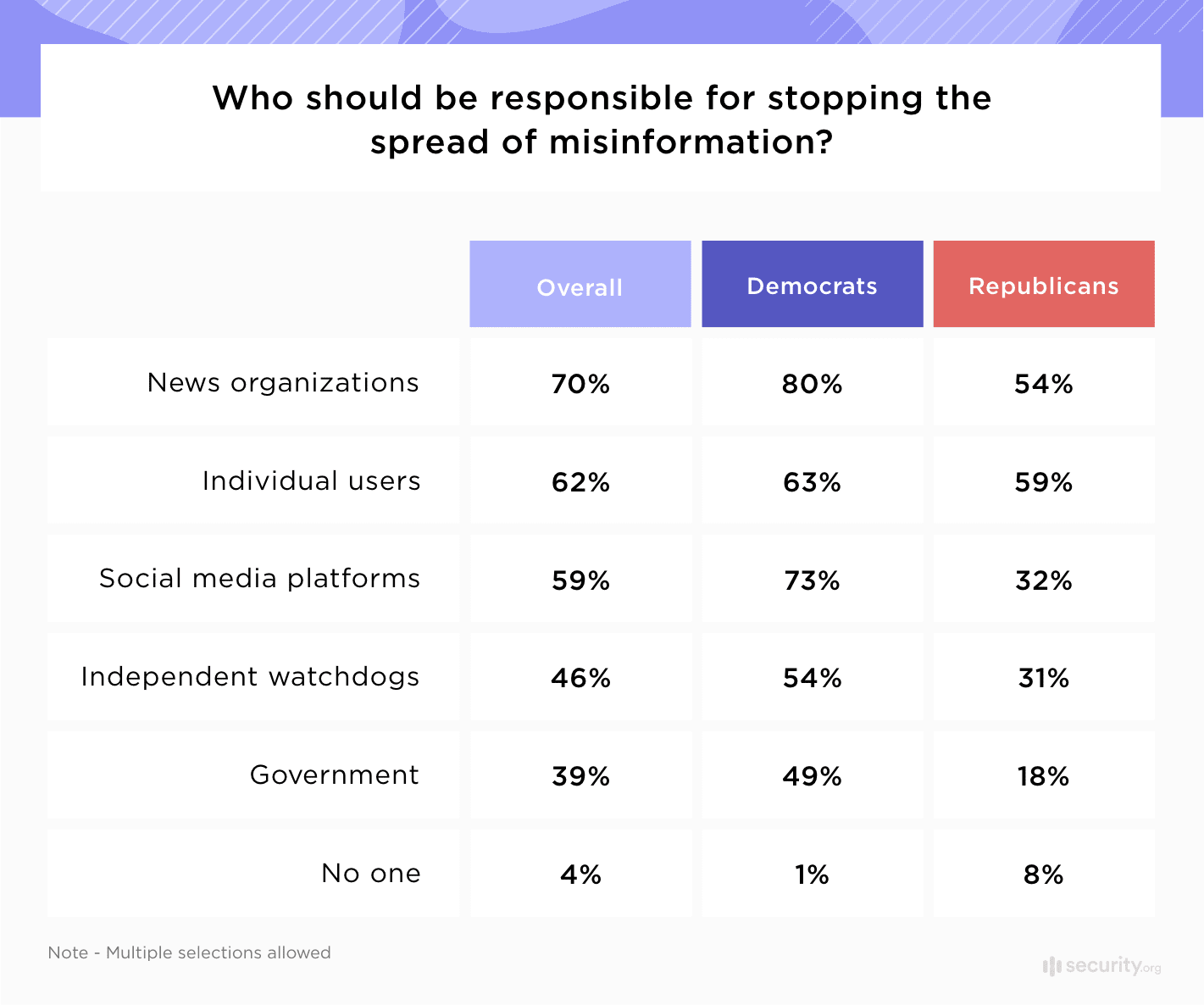

Let's talk about the hard numbers. The Department of Homeland Security post making the federal claims received more than 17 million views before this article was written. How many views did the corrections get? How many people saw video evidence that contradicted the claims? How many people encountered the Governor's statement that the federal narrative was "nonsense"?

There's no exact figure, but we can make educated guesses. The Governor's statements reached news outlets, which reported them, which were seen by their audiences. That's likely millions of people, but it's probably not 17 million. And crucially, it's not the same 17 million people.

If 17 million people saw the federal narrative and 8 million people saw the Governor's response, that's not a wash. It's not equal information. It's asymmetric. Seven million people were reached by the first narrative and not reached by the second. They may later encounter corrections, or they may not. They may weigh the corrections against the original narrative, or they may dismiss the corrections as politically motivated.

This asymmetry compounds over time. The initial narrative becomes the background assumption against which new information is interpreted. When new information comes in, it's filtered through that assumption. "Federal authorities claim X" becomes simply "X is true" in the popular consciousness. When you later hear "Actually, X might not be true," the human brain doesn't reset. It updates slightly, but remains anchored to the original claim.

Research in psychology and communication shows that this anchoring effect is powerful. People are very resistant to changing their initial beliefs, especially on political topics. The corrections would need to be as prominently featured as the original claims to significantly shift public opinion. And that almost never happens.

Moreover, corrections often backfire. When someone who believed the original narrative encounters a correction, they don't always accept it. Instead, they might become more entrenched in the original belief, seeing the correction as an attack or a lie. This is called the backfire effect, though it's somewhat contested in the literature. Regardless of the mechanism, corrections are not automatic belief-changers.

So we have a situation where 17 million people encountered claims about the shooting, and the vast majority of those people likely never encountered information that contradicted those claims in any meaningful way. For them, the federal narrative is simply what happened. The shooting was of a terrorist or an assassin trying to harm law enforcement. Case closed.

This is the mechanism through which disinformation becomes difficult to dislodge. It's not that people are stupid. It's that information flows are asymmetric. It's that corrections require additional cognitive effort. It's that political narratives become embedded in identity, and changing your belief about a narrative might feel like changing your identity.

The Broader Context: Pattern or Anomaly

Was the incident with Pretti an anomaly, or part of a pattern? This is the question that changes everything about how we interpret what happened.

If it was an anomaly, then it's an isolated tragedy. A tragic accident where a shooting that probably shouldn't have happened did happen. These things occur in law enforcement. They're investigated, and hopefully, we learn from them and prevent them in the future.

If it's part of a pattern, then it becomes something else. It becomes evidence of systemic issues with federal enforcement tactics. It becomes a sign that something needs to change, not just in this case, but in how federal immigration enforcement operates.

The fact that Renee Nicole Good was killed 17 days earlier is important here. Both victims were 37 years old. Both were killed by federal immigration agents. Both incidents raised questions about whether the officers involved had acted appropriately. Both incidents involved rapid federal narrative-making designed to justify the shootings.

Two incidents in 17 days is not a large statistical sample. We can't draw broad conclusions from two data points. But it's also not nothing. It's a pattern worth examining.

Data on federal immigration enforcement shootings is hard to come by. The federal government doesn't make comprehensive statistics on use of force incidents readily available. This is itself noteworthy. When agencies don't track their own use of force data, it becomes impossible to know whether patterns exist.

What we do know is that Immigration and Customs Enforcement has been subject to multiple investigations and reports documenting problematic conduct over the years. Allegations range from improper detention to racial profiling to excessive force. These allegations don't all result in shootings, but they suggest an agency with structural issues.

The question is whether the Pretti incident is evidence of those structural issues or an exception to otherwise proper conduct. The federal narrative tries to frame it as an exception: one agent acting appropriately in response to a specific threat. The pattern-based interpretation frames it as evidence of broader problems.

Both interpretations can't be simultaneously true, but we can't determine which is correct from a single incident. We would need more data, more transparency, and more independent investigation.

Initial claims reached 17 million people, while corrections only reached an estimated 5 million, highlighting the asymmetry in information dissemination. Estimated data.

How Disinformation Calcifies: The Role of Institutional Power

Here's something crucial that doesn't get enough attention: disinformation spread by institutions is different from disinformation spread by random people on the internet. When a random person posts false claims on Twitter, those claims might go viral, but they lack institutional backing. When the Department of Homeland Security posts false claims, those claims have institutional power behind them.

Institutional power means several things. First, it means access to large platforms and distribution networks. The DHS post reached 17 million people because DHS has a large following and X's algorithm privileges government accounts. A random person posting the same claims wouldn't reach 17 million people.

Second, institutional power means perceived credibility. When DHS makes a claim, people assume it's based on evidence and investigation. When a random person makes the same claim, people assume it might be a guess or a rumor. Even if the claim is identical, the source matters.

Third, institutional power means the ability to shape subsequent reporting. When DHS makes claims, news organizations feel obligated to report those claims. When a random person makes claims, news organizations can ignore them. The DHS's framing becomes the baseline against which news is reported.

Fourth, institutional power means the ability to reinforce narratives through multiple channels. When DHS makes claims, those claims can be reinforced by the White House, by Cabinet secretaries, by political allies. The narrative becomes overdetermined: it's repeated from multiple sources of institutional authority.

This is why disinformation spread by institutions is so much more difficult to correct than disinformation spread by random people. Random disinformation can be debunked through fact-checking and alternative reporting. Institutional disinformation can't be debunked because the institutions that could debunk it are either complicit in the disinformation or reluctant to directly contradict federal authorities.

When the Governor says the federal narrative is "nonsense," he's using his own institutional power to contradict the federal narrative. But he's still operating from a position of weakness relative to federal authority, and he's speaking to a different audience. The asymmetry remains.

This is the most concerning aspect of what happened with the Pretti incident. It's not that disinformation circulated on social media. That happens constantly. It's that the disinformation came from federal institutions and was amplified by those institutions and their political allies. It means the normal correction mechanisms don't work, because those mechanisms assume that institutions can be relied upon to provide accurate information and that corrections will come from rival institutions. When multiple institutions are aligned in spreading disinformation, corrections become nearly impossible.

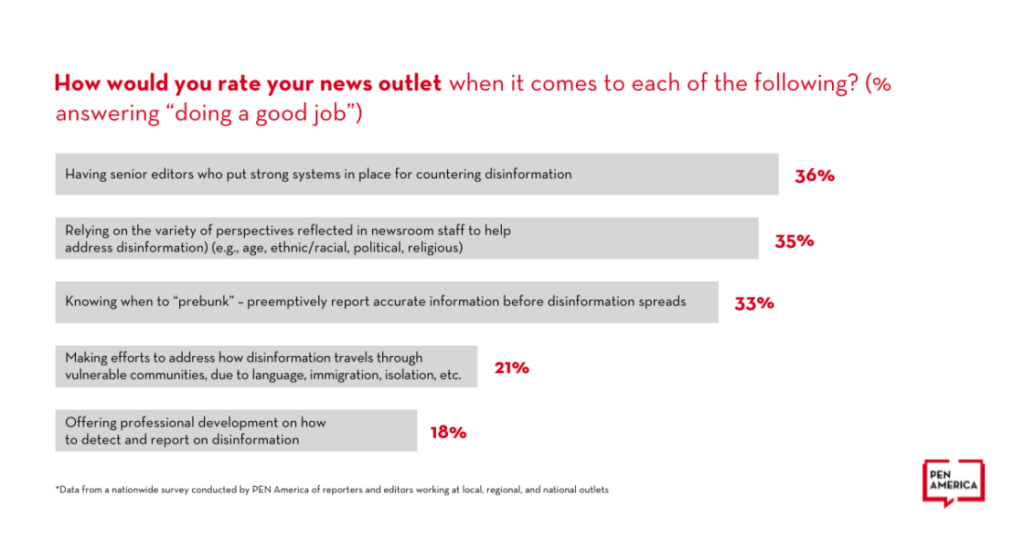

The Role of Media: Complicity and Resistance

News organizations faced a genuine dilemma. Report what federal authorities claimed, and you're reporting the official narrative without critical examination. Don't report what federal authorities claimed, and you're accused of suppressing news or ignoring official statements.

Most news organizations split the difference. They reported the federal claims prominently, then reported the alternative information less prominently. Headlines announced what federal authorities claimed. Later paragraphs mentioned that there was video evidence that seemed to contradict some claims. This structure meant that someone skimming headlines would get the federal narrative, while someone reading the full article would get a more complete picture.

But here's the problem: most people don't read past the headline. A study by Pew Research found that most social media users who encounter news articles don't click through to read the full article. They read the headline and maybe the first sentence, then move on. For those people, the federal narrative is what they learn.

Some news organizations did push back more directly. The New York Times and Bellingcat conducted frame-by-frame analysis of videos and published findings that directly contradicted federal claims. The BBC reported on the context of the incident: Pretti's attempt to help the woman who had been pepper sprayed. These reports provided alternatives to the federal narrative, but they required readers to seek them out. They didn't break through as leading narratives.

This is partly because of institutional lag. Traditional news organizations move slowly. They require multiple sources, legal review, and editorial process. By the time a story is thoroughly reported and verified, the initial narrative has already solidified. Digital-first outlets and social media move much faster, which means whoever controls the narrative in the first few hours has a significant advantage.

Some news organizations were more complicit than others. Right-wing outlets like the Post Millennial reported the federal narrative largely uncritically, not bothering to mention video evidence or alternative interpretations. This wasn't necessarily dishonest; it was selective. They chose to emphasize some facts and omit others, which created a narrative that served their political interests.

This points to a fundamental problem with media ecosystems fractured along political lines. When different audiences consume different news sources, they end up with radically different understandings of events. The federal narrative dominates in some outlets. The alternative narrative dominates in others. The person consuming mainstream conservative media knows a very different story than the person consuming mainstream liberal media. They're not wrong in their different understandings; they're just working from different information.

This fragmentation is partly a technological problem. Algorithms push people toward content they agree with, creating filter bubbles. But it's also a political problem. When political identities and media consumption patterns align, narratives can diverge radically, and there's no common ground to bridge them.

What Happened to Justice? The Investigation Afterwards

A shooting of a civilian by federal agents triggers an investigation. The question is who investigates. The federal government? State authorities? Some hybrid?

In this case, Governor Walz insisted that Minnesota's justice system would have the last word. This is a claim to jurisdiction. The state is saying, essentially, that this incident occurred in Minnesota, and Minnesota law applies.

But the person shot wasn't just anyone. They were shot by federal agents in the course of federal operations. This creates jurisdictional complexity. Federal courts might argue they have jurisdiction because federal agents were involved. State courts might argue they have jurisdiction because the shooting occurred in the state.

This jurisdictional conflict is important because it's where questions of accountability get sorted. Different courts, different precedents, different standards of justice. The choice of which jurisdiction handles the case can determine whether the officers are prosecuted, civilly sued, or cleared.

For the purposes of this examination, what matters is that the investigation process itself becomes contested. The federal narrative isn't just a claim about what happened. It's also a narrative designed to frame the incident as something that doesn't require investigation, because the facts are already clear.

When Bovino claimed to have a "full assessment" of what happened, he was essentially claiming that the matter was resolved, that there was nothing more to investigate. This is a pre-emptive strike against investigation. If the facts are already determined, then an investigation is just going through motions.

But if the facts are disputed, as the evidence suggests they are, then investigation becomes crucial. We need to determine what actually happened, why it happened, whether the officers involved acted appropriately, and whether changes are needed.

The disinformation narrative short-circuits this investigation. If the public believes the federal narrative, then there's no pressure for investigation. If the public demands investigation, then the federal narrative is undermined. This is why narratives and investigation are inextricably linked. The narrative determines whether investigation is demanded. The investigation determines what actually happened.

The federal claims reached 17 million views, while the Governor's response reached only 8 million, highlighting a significant asymmetry in information dissemination. Estimated data.

The Broader Implications: Institutional Disinformation as a Governance Problem

What we've examined here is a specific incident, but the implications extend far beyond this case. The question is whether federal institutions can be relied upon to provide accurate information when that information reflects on their own conduct.

The answer, based on this case, is that they cannot. Federal institutions have incentives to protect themselves, to minimize criticism, and to frame events in ways that justify their own actions. When those incentives conflict with truth-seeking, institutions generally choose self-preservation.

This isn't a moral failing of individuals within institutions, though individual moral failures certainly occur. It's a structural problem. An agency that's responsible for a shooting is also responsible for explaining that shooting to the public. The agency that needs to justify its actions is the same agency providing information about those actions. This is a conflict of interest built into the structure.

How do we resolve this? Several possibilities. First, independent investigation. When federal agents use lethal force, the investigation should be conducted by independent authorities, not by the federal agency involved. This is already the standard for police shootings in many jurisdictions, though it's not consistently applied.

Second, transparency. Federal agencies should be required to release all video evidence, all 911 calls, and all documentation within hours of a shooting. No selective release. No framing. Just the raw evidence, available to the public and to journalists.

Third, oversight. Congress should conduct hearings on federal use of force. Agencies should be required to report use of force statistics and to justify any increase in such incidents. This creates accountability to elected representatives.

Fourth, courts. When disinformation affects investigations or undermines justice, courts should have the ability to address it. If federal institutions are making false claims to obstruct justice, that should be prosecutable.

None of these solutions are perfect. All of them involve tradeoffs. But the alternative is to accept that federal institutions will control the narrative around their own conduct, and that corrections will be inadequate and delayed.

For the broader governance system, this is a crisis. If institutions can be trusted to control narratives about their own actions, then accountability becomes impossible. Power without accountability is the definition of tyranny. The specific incident with Pretti becomes important not because of the details of the case, but because it exemplifies a structural problem that extends throughout government.

Information Warfare in the Modern Context: Lessons from Minneapolis

The Pretti incident illustrates how information warfare operates in practice. It's not about classified documents or foreign interference, though both can happen. It's about controlling narratives through institutional authority and digital amplification.

The winning strategy in this case had several components. First, early claims made with confidence and specificity. Details like "9mm handgun" and "two loaded magazines" sound authoritative even if they're unverified. Second, institutional amplification through official accounts and government officials. When the White House, Cabinet secretaries, and federal agencies all repeat the same narrative, it gains authority through repetition. Third, influencer networks that amplify to audiences that might not trust mainstream institutions. If you distrust the mainstream media, you're more likely to trust a right-wing influencer who repeats what federal authorities claimed. Fourth, media channels that report the narrative uncritically. Right-wing outlets that report federal claims without serious critical examination amplify the narrative further.

The counter-narrative had fewer of these components. Video evidence contradicting the claims, but video evidence is ambiguous and requires interpretation. State government contradicting the federal narrative, but state government lacks the authority of federal institutions. Independent journalists doing analysis, but reaching smaller audiences than the initial claims. None of these elements, individually or together, had the amplification power of the federal narrative.

This is the nature of information warfare in the modern context. It's not necessarily about deception. It's about asymmetric control of information flows. The side that can make claims first, amplify them through multiple channels, and defend them through institutional authority has a massive advantage.

Future incidents will likely follow similar patterns. The question is whether we're learning the lessons or just repeating them. Are we building better mechanisms for independent investigation? Are we requiring transparency? Are we holding institutions accountable for false claims? Or are we just accepting that this is how information flows now?

The answer matters because information warfare is asymmetric. It's much easier to spread a false narrative than to correct it. Once a narrative is embedded, people interpret new information through the lens of that narrative. Corrections require overcoming powerful cognitive biases and social pressures. This asymmetry means that the side making claims first has a structural advantage.

If we're going to address this, we need to change the structure. We need independent investigation, transparency, and accountability. We need to make it harder for institutions to control narratives about their own conduct. And we need to recognize that information warfare isn't foreign interference or conspiracy theories. It's a structural feature of modern governance that we can address through institutional reform.

The Human Cost: What Gets Lost in Narrative Wars

In all of this discussion about narratives and disinformation, it's easy to lose sight of something crucial: a person is dead. Pretti's family is grieving. His colleagues at the VA knew him as a coworker, probably a person they interacted with regularly. His death is not a narrative. It's a loss.

When we engage in debates about what the federal narrative was and what the video evidence shows, we're engaging in what feels like an abstract intellectual exercise. But the abstraction has consequences. The narrative we settle on becomes the official story. It becomes what his family has to live with. It becomes what the culture remembers.

If the official narrative is that Pretti was a terrorist trying to massacre law enforcement, then his family has to live in a world where their grief is dismissed as the grief of a terrorist's family. They have to live with their loved one's name being associated with mass murder, regardless of whether that characterization is accurate.

If the official narrative becomes, through investigation and evidence, that Pretti was a person trying to help someone and was shot by federal agents during an apprehension, then his family has to live with the knowledge that their loved one was killed, but they're at least not living with the characterization of him as a terrorist.

This matters. The narrative affects not just how the public understands the incident, but how the victims and their families are treated, how they're remembered, what the official record says about them.

There's also the question of justice. If the narrative is accepted without investigation, then there's no accountability. The officer who shot Pretti is commended for acting in self-defense. There's no investigation into whether the shooting was necessary, whether less lethal alternatives were available, whether the escalation was appropriate. The officer continues in their job, continuing to operate under the same behavioral patterns that led to the shooting.

But if investigation determines that the officer acted inappropriately, then there's potential for accountability, for disciplinary action, for policy changes that might prevent future incidents.

This is why narratives matter beyond their value as information. They determine whether people are held accountable. They determine whether reforms happen. They determine whether the person who is killed is remembered as a victim or as a threat.

In the Pretti case, the federal narrative worked toward no accountability and no reform. The alternative narrative worked toward accountability and potential reform. The struggle between these narratives isn't abstract. It determines the real-world consequences for the people involved.

Moving Forward: Questions Without Easy Answers

What we've examined here raises questions that don't have easy answers. How do we ensure that federal institutions provide accurate information when they're investigating their own conduct? How do we prevent institutional disinformation while respecting the legitimate confidentiality needs of ongoing investigations? How do we break through asymmetric information flows that privilege official narratives over corrections?

These aren't rhetorical questions. They're practical problems that democratic governance needs to solve. The current system isn't working. Institutions are making false claims. Those claims are spread widely. Corrections are delayed and reach smaller audiences. The result is that the public doesn't have accurate information about what their government is doing.

One approach is radical transparency. Release all video evidence immediately. Release all communications between officers and supervisors. Release all investigative findings as they're made, not waiting for final conclusions. This maximizes the information available to the public and to journalists, making it harder for institutions to control narratives.

Another approach is independent investigation. When federal agents use lethal force, the investigation should be conducted by state authorities or by an independent federal agency, not by the agency involved. This removes the conflict of interest and creates accountability.

A third approach is legislative oversight. Congress should conduct hearings on federal use of force. Agencies should be required to report statistics, to justify patterns, and to explain increases in incidents. This creates accountability to elected representatives and to the public.

A fourth approach is media literacy. As a society, we need to get better at understanding how information flows, how institutional power shapes narratives, and how to evaluate claims critically. This isn't about distrust of institutions, though some skepticism is healthy. It's about understanding the structural incentives that shape information flows.

A fifth approach is institutional reform within agencies. Training on de-escalation. Clearer rules of engagement. Better supervision. Consequences for officers who engage in unnecessary force. These reforms change the incentives within institutions to move toward accuracy and restraint rather than self-protection and escalation.

None of these approaches is a silver bullet. All of them involve tradeoffs. Radical transparency might compromise ongoing investigations. Independent investigation might slow the process. Legislative oversight might be ineffective if Congress isn't willing to push. Media literacy doesn't help if people aren't willing to engage. Institutional reform depends on institutions willing to reform.

But the current system is clearly broken. Institutions are making false or misleading claims about their own conduct. Those claims are spread widely through multiple channels. Corrections are inadequate. The public doesn't have accurate information. If we're going to fix this, we need to address the structural problems, not just the specific incidents.

Conclusion: The Stakes of Narrative Control

The shooting of Alex Pretti in Minneapolis on a Saturday afternoon became a case study in how modern disinformation operates. It wasn't a conspiracy in the traditional sense. It was a series of incentives leading to rapid claims, institutional amplification, and asymmetric information flows that privileged those claims over corrections.

Federal authorities made specific claims about what happened. Those claims were contradicted by video evidence within hours. Yet those claims reached 17 million people. The corrections reached a smaller audience. The asymmetry is the story.

What we've examined is not a unique incident. It's a pattern that repeats throughout American governance. Institutions make claims. Those claims are amplified through multiple channels. Corrections are delayed and inadequate. The public ends up with a distorted understanding of what actually happened.

This matters because it affects accountability, it affects reform, it affects our understanding of our own government. If we can't trust institutions to provide accurate information about their own conduct, then accountability becomes impossible. If we don't have accurate information, we can't demand reforms. If we accept institutional narratives uncritically, we lose the ability to hold power accountable.

The specific facts of the Pretti incident are important. It matters whether he had a gun or was holding a phone. It matters whether he intended to harm law enforcement or was trying to help someone. It matters whether the shooting was justified or was a use of excessive force. These facts determine whether the officer involved should face investigation, discipline, or prosecution.

But beyond the specific facts, there's a larger question: how do we ensure that the public has accurate information about what their government does? How do we create institutions and systems that prioritize truth-seeking over narrative control? How do we break through asymmetric information flows that privilege official claims over corrections?

These are the questions that the Pretti incident raises. The answers will determine not just what happens in this case, but how future incidents are handled, how accountability functions, and how democracy operates when institutions can control narratives about their own conduct.

The case of Alex Pretti is ultimately about something larger than one shooting. It's about information, power, accountability, and how democracies function when institutions shape the narratives that the public uses to understand reality. Getting that right isn't just an academic exercise. It's the foundation of democratic governance itself.

FAQ

What is institutional disinformation?

Institutional disinformation is false or misleading information spread by government agencies, law enforcement, or other official bodies. It differs from individual misinformation because it has institutional credibility and amplification behind it. When a federal agency makes claims about its own conduct, the public typically assumes those claims are based on investigation and evidence, even if they're made before investigation is complete. This creates asymmetric power dynamics where institutions can shape narratives about themselves.

How does narrative control affect investigations?

When institutions control the narrative about an incident, investigation becomes less likely because the public perceives the facts as already established. If federal authorities claim something happened clearly, why would investigation be necessary? This creates a feedback loop where the narrative prevents the investigation that might contradict it. Independent investigation becomes difficult because it appears to contradict official authority rather than seeking truth.

Why do corrections to false claims fail to change minds?

Research in psychology shows that people are resistant to changing their initial beliefs, especially on political topics. The first narrative a person encounters becomes an anchor that subsequent information is filtered through. Corrections are often interpreted as attacks on the original source rather than as evidence of error. Additionally, corrections rarely reach as many people as the original false claim, creating an asymmetry where false claims reach wider audiences than corrections.

What role does social media play in spreading institutional claims?

Social media amplifies institutional claims because algorithms privilege content from official accounts and content that generates engagement. When a federal agency posts claims on X, those claims reach millions of people because the account has large followings and X's algorithm boosts government content. This gives institutions massive amplification advantages compared to individuals or organizations posting corrections. The result is that false claims from institutions can reach 10-17 million people before corrections are published.

How can we prevent institutional disinformation?

Several approaches can help: requiring immediate release of video evidence, conducting investigations by independent agencies rather than by agencies investigating themselves, creating legislative oversight of federal use of force, improving media literacy so the public understands how institutions shape narratives, and implementing institutional reforms that align incentives toward accuracy rather than self-protection. None of these approaches is sufficient alone, but together they could address the structural problems that enable institutional disinformation.

What makes video evidence controversial even when it seems clear?

Video evidence is always subject to interpretation. Multiple angles show different perspectives. The timing of when evidence was recorded affects what it shows. Context matters: what happened before and after the moment recorded. Additionally, people interpret visual evidence through the lens of the narratives they've already accepted. If you believe the federal narrative, you might interpret a phone as a gun or see actions as threatening even if others see them as innocent. Video evidence isn't automatically resolving because it can be interpreted in multiple ways.

Key Takeaways

- Federal institutions made specific claims about a shooting that were contradicted by video evidence within hours, yet those claims reached 17 million people

- Institutional disinformation spreads asymmetrically: initial false claims reach vastly larger audiences than corrections

- The federal narrative was amplified through coordinated messaging from the White House, Cabinet secretaries, and right-wing influencers

- Video evidence and independent analysis contradicted federal claims, but those corrections circulated to smaller audiences

- Structural conflicts of interest occur when institutions investigate their own conduct, creating incentives for self-protective narratives

Related Articles

- How Political Media Targets Marginalized Communities [2025]

- ICE Agents and Qualified Immunity: Why Accountability Remains Elusive [2025]

- Minneapolis ICE Shooting & Protests: Federal Response [2025]

- ICE Judicial Warrants: Federal Judge Rules Home Raids Need Court Approval [2025]

- ICE Agents Doxing Themselves on LinkedIn: Privacy Crisis [2025]

- When Federal Enforcement Changes Everything: How Communities Adapt [2025]

![How Disinformation Spreads: The Border Patrol Shooting and Political Narratives [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-disinformation-spreads-the-border-patrol-shooting-and-po/image-1-1769303271313.jpg)