Introduction: The Privacy Paradox at the Heart of Immigration Enforcement

There's a strange tension playing out in the world of federal immigration enforcement, and it cuts right to the heart of how privacy actually works in the digital age. On one hand, the Department of Homeland Security is treating the public identification of its agents as a serious crime. They've branded it "doxing," threatened criminal prosecution, and argued that revealing officer identities puts lives at risk. DHS leadership has become increasingly aggressive about this issue, framing the protection of agent anonymity as a matter of national security and personal safety.

But here's where the story gets weird: thousands of DHS and ICE employees are themselves posting their jobs, locations, and career details on LinkedIn. They're sharing professional accomplishments, reacting to motivational posts about leadership, updating their employment status, and in some cases actively soliciting new job opportunities with the hashtag #opentowork. They're doing all this publicly, with their real names and government affiliations fully visible to anyone with an internet connection.

This creates a bizarre dynamic where federal agents are simultaneously claiming they need facial coverings and anonymity protections to stay safe, while voluntarily posting information that makes them easy to identify on one of the world's largest professional networks. It's not a question of hackers breaching secure databases or activists conducting sophisticated cyber operations. It's a question of basic digital literacy and institutional disconnect.

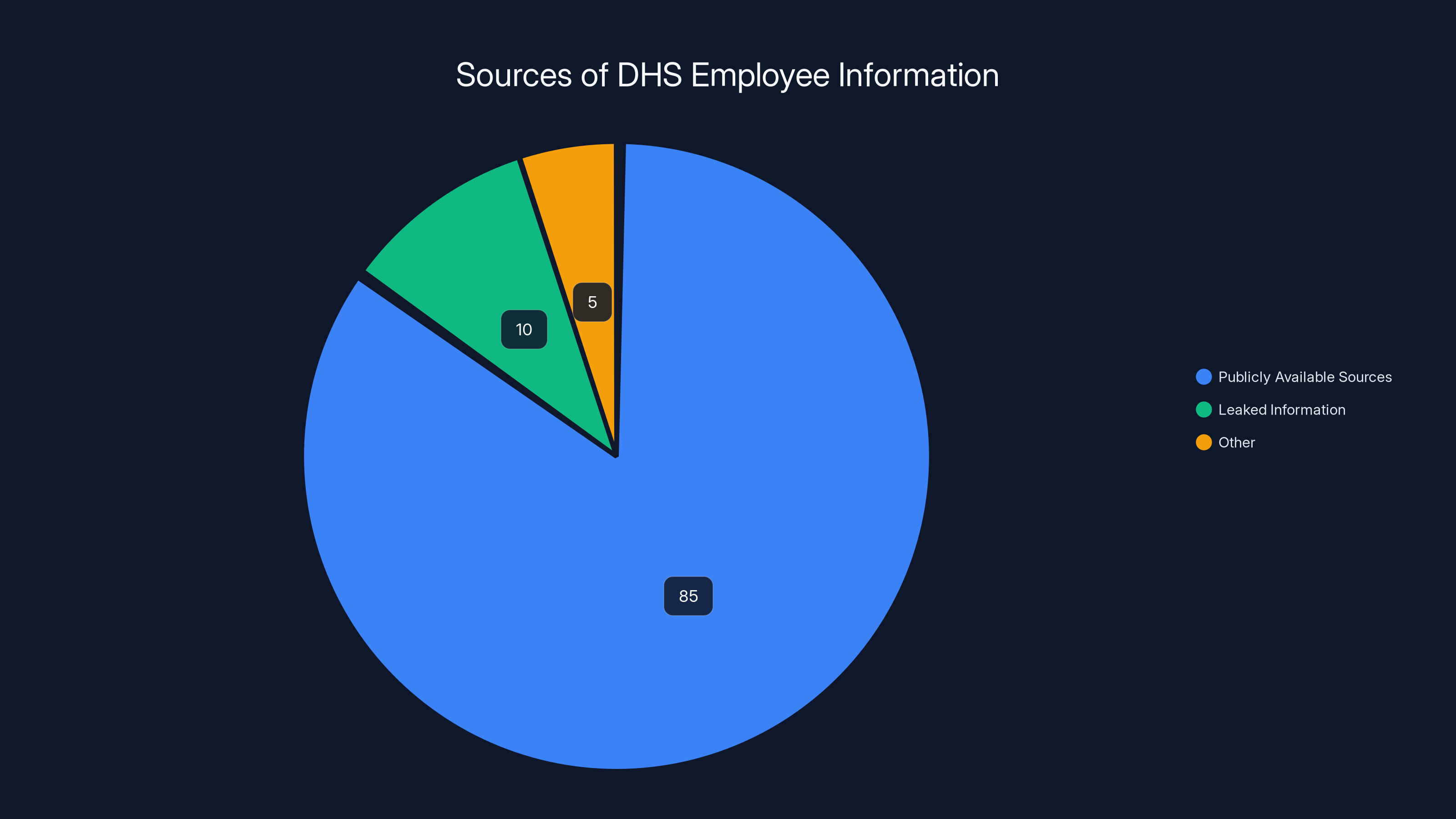

Recently, a website called ICE List went viral after claiming to have obtained a leak of personal information about nearly 4,500 DHS employees. But when researchers actually analyzed what the site contained, they found something unexpected: most of the information came from publicly available sources. The site's creators hadn't stolen anything. They'd simply aggregated data that these federal employees had already made public themselves through LinkedIn profiles, public payroll databases, and professional networking sites.

This situation raises fundamental questions about institutional policy, personal responsibility, and how federal agencies are grappling with the realities of digital life. It also exposes a significant gap between how DHS talks about protecting officer identities and the actual practices of its employees. The agencies claim agents need special protections from doxing, yet they haven't effectively communicated to their workforce why posting professional details on LinkedIn might undermine those protections.

The story isn't about bad actors conducting sophisticated cyber attacks. It's about the collision between outdated institutional security thinking and the everyday practices of people living in 2025.

TL; DR

- DHS threatens prosecution for "doxing" ICE agents while thousands of employees voluntarily post identifying information on LinkedIn

- ICE List aggregated mostly public information, not stolen data, from LinkedIn profiles and public payroll databases

- Federal agents post resumes, career updates, and location information on professional networks despite security concerns

- The gap between policy and practice reveals weak internal communication about digital privacy risks

- Public records like court testimony and payroll information are already available through FOIA and government transparency databases

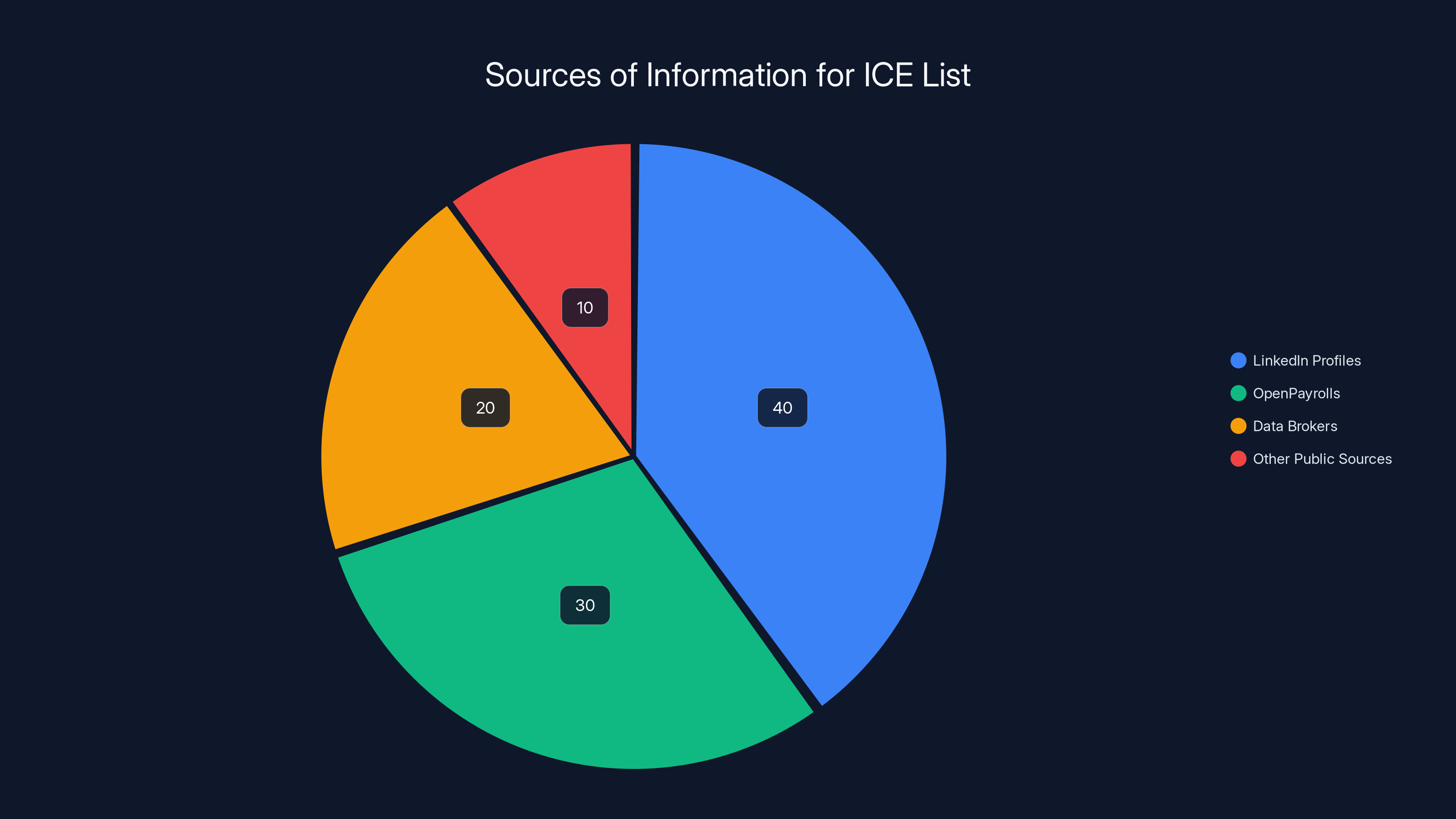

Estimated data shows LinkedIn profiles as the primary source of information for ICE List, highlighting the role of self-disclosed data.

What Exactly Is ICE List and How Did It Become Controversial?

ICE List presented itself as a crowdsourced wiki dedicated to documenting information about ICE officers and other DHS employees. Think of it as someone built a wiki in the style of Wikipedia, but focused entirely on cataloging federal immigration enforcement personnel. The site operates through volunteer contributions, with moderators deciding who gets added to the database and which information is marked as "verified."

The wiki includes category pages that feature links to every profile within that category, making it easy to browse through hundreds of profiles at once. This structure matters because it's not just a passive archive. It's an actively organized, indexed repository designed to make finding specific individuals or browsing through large groups of agents relatively straightforward.

When ICE List launched and subsequently went viral, the narrative that accompanied it emphasized the dramatic nature of the data. The site's creators claimed they'd obtained what amounted to a "leak" of sensitive information about federal employees. The framing suggested this was a security breach, unauthorized data acquisition, and a potential threat to officer safety. News coverage picked up the story with headlines emphasizing the leak aspect, and DHS responded with fury.

But here's what's important: when researchers actually looked at what information ICE List contained and how it was sourced, the story shifted significantly. The database wasn't built on stolen data from hacked government systems. Instead, it relied heavily on information that the DHS employees themselves had already posted publicly online. This distinction matters enormously because it changes the entire conversation about what "doxing" actually means and who bears responsibility for exposing these identities.

Dominic Skinner, who owns and operates ICE List, pushes back against the doxing characterization. He argues that aggregating publicly available information isn't doxing in any meaningful sense. In his view, if simply existing in online environments and posting your own information counts as doxing yourself, then the term loses all meaning. The site's own about page explicitly states it doesn't publish home addresses and has policies against harassment or misuse of the platform.

Several profiles on the ICE List wiki cite specific sources for their information. Open Payrolls, a searchable database of public employee salaries, is frequently referenced. The database includes some ICE employee payroll information that was released by the US Office of Personnel Management in response to Freedom of Information Act requests. Signal Hire, a data broker specializing in lead generation, is another cited source. Signal Hire itself maintains direct links to LinkedIn profiles of people representing themselves as ICE officers.

The methodological simplicity of building this database is almost mundane. A WIRED analysis found that you could surface hundreds of ICE officer profiles on LinkedIn by simply visiting ICE's official LinkedIn company page and clicking the "Show more results" button on the people tab. There's no sophisticated hacking involved. There's no social engineering or deceptive data collection. The information is sitting right there in plain sight on one of the world's most popular professional networks.

The Scale of the Problem: How Many Federal Agents Are Voluntarily Exposing Themselves?

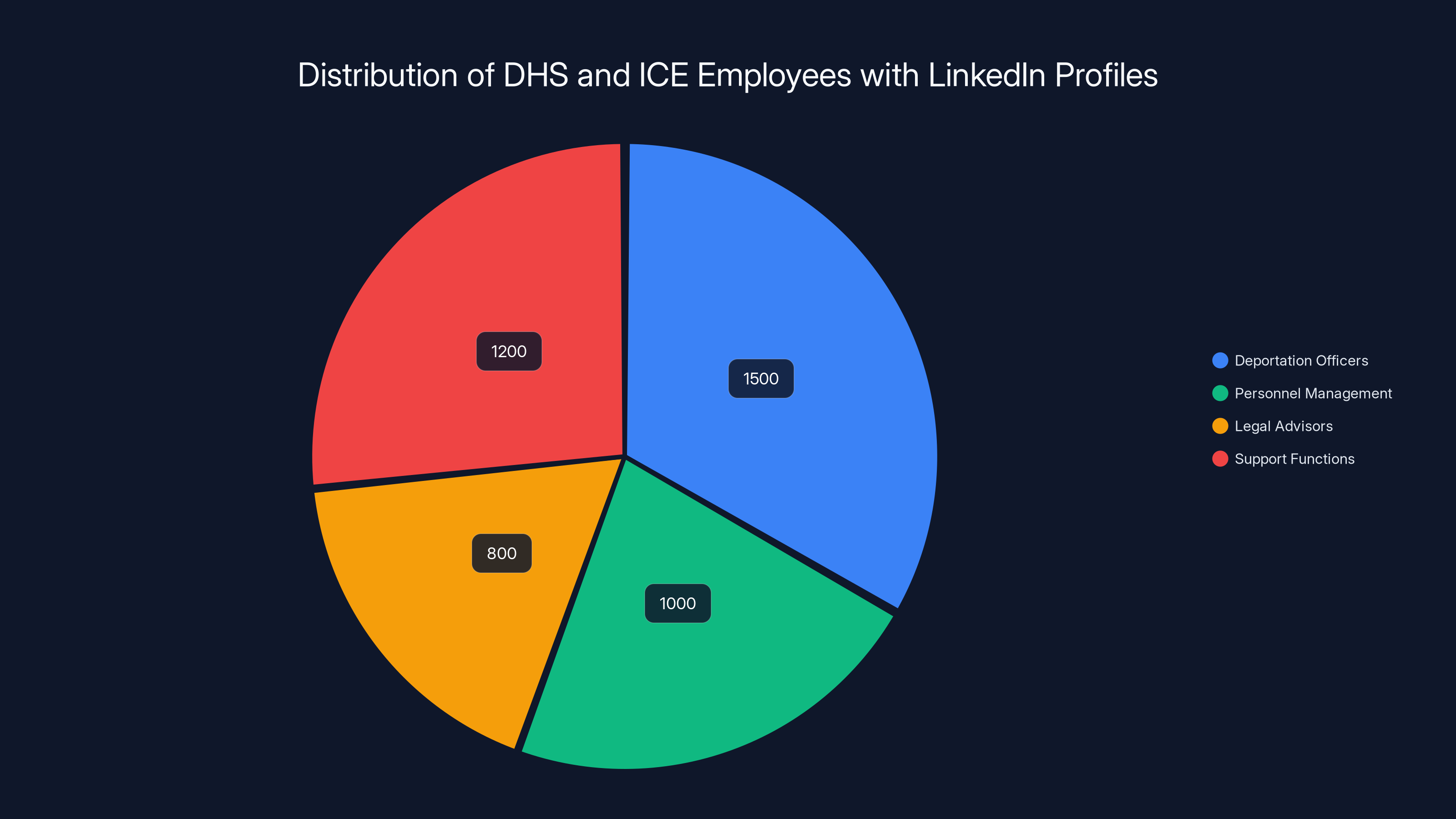

We don't have exact figures on how many DHS and ICE employees maintain active LinkedIn profiles, but the numbers are substantial enough to be alarming from a security perspective. ICE List claims to have documented information about nearly 4,500 DHS employees, though not all of these would necessarily be verified agents with operational roles.

What makes this significant is that these aren't isolated cases of one careless employee forgetting to adjust privacy settings. This appears to be a widespread pattern affecting thousands of federal immigration enforcement officers across multiple agencies and operational divisions. The sheer volume suggests this isn't a training or policy failure limited to a few offices. It's systemic.

The breakdown includes ICE deportation officers (the agents directly involved in enforcement operations), personnel management staff, legal advisors, and other support functions within DHS. Some of these individuals are in highly visible roles conducting enforcement operations. Others work in administrative functions where their identities are theoretically less operationally sensitive. But all of them are posting identifying information on a platform where their employment status, location, and professional networks are visible to anyone.

LinkedIn's own search and discovery features make this even easier to access. The platform's algorithm is designed to surface professionals and make connections visible. If you search for "ICE Officer" or "Immigration and Customs Enforcement" on LinkedIn, you'll find hundreds of accounts. You can filter by location, employment duration, and connections. You can see who they're connected to, what companies they've worked for previously, and sometimes get a sense of their career trajectory.

What's particularly striking is that these aren't dummy profiles or accounts created under pseudonyms. These are real people using their actual names, posting regular updates about their professional lives. Some are sharing New Year's resolutions. Some are liking and commenting on motivational posts about leadership and innovation. Some are actively using the #opentowork hashtag to indicate they're interested in new opportunities.

The volume and visibility of this information creates a database that's far more detailed than anything you'd get from a simple name and agency affiliation. You get employment history, educational background, professional networks, and sometimes location information spanning multiple years. You get a sense of career progression and specialization. You get enough information to build a fairly comprehensive profile of someone's professional identity.

Estimated data shows a significant number of LinkedIn profiles from various roles, with deportation officers being the largest group. This highlights a systemic issue of exposure among federal agents.

Why Are Federal Agents Using LinkedIn in the First Place?

The presence of federal immigration enforcement agents on LinkedIn might seem surprising at first, but when you think about it, the reasons are pretty straightforward. LinkedIn has become the professional standard for almost every industry and occupation, including federal government work. It's where people network, where employers recruit, and where professionals maintain visibility in their field.

For DHS and ICE employees, LinkedIn serves several legitimate professional functions. It helps with career advancement within the agency. Federal employees can use their profiles to document qualifications and experience that matter for promotions and transfers. It helps with networking at professional conferences and industry events. Even immigration enforcement has professional conferences, training events, and industry organizations where networking matters.

LinkedIn also functions as a recruitment tool for federal agencies themselves. DHS and ICE organizations maintain official company pages and use LinkedIn to recruit new employees. They post job openings and use the platform as part of their hiring process. This creates an obvious institutional pressure for current employees to maintain profiles. If the organization is recruiting on the platform, it sends a signal that having a presence on LinkedIn is normal and acceptable.

There's also a generational element here. Younger federal employees who've grown up with social media and professional networking platforms likely view LinkedIn as a standard professional tool, not a security risk. They may not fully appreciate how the aggregation of seemingly innocent professional information can create a more complete picture than the individual details would suggest.

Additionally, federal employees don't receive comprehensive guidance from their agencies about the specific security implications of maintaining public professional profiles. Border Patrol has documents instructing employees to "be mindful of what you post on social media," but this is vague guidance that doesn't specifically address LinkedIn or explain exactly what information is considered sensitive. It doesn't tell agents not to list their employer or job title. It doesn't explain the risks of making location information public. It's general enough to be easy to ignore or interpret loosely.

There's also the issue of professional incentives overriding security concerns. A LinkedIn profile helps with career development. It can lead to better job opportunities within the federal government or in the private sector later on. It signals professional competence and ambition. For someone trying to advance their career, the benefits feel tangible and immediate, while the security risks feel abstract and distant.

The lack of specific, mandatory security protocols around LinkedIn usage creates a situation where individual employees are left to make their own risk assessments. Most people aren't great at assessing security risks because the threats aren't immediate or personal. A DHS employee maintaining a LinkedIn profile might never experience any negative consequences from it. The hypothetical risks feel theoretical compared to the concrete career benefits of having a visible professional presence.

The Public Records Problem: Court Documents and Testimony Already Expose Officer Identities

Here's something that complicates the entire narrative about protecting officer identities: much of the basic information about ICE officers is already public record because they testify in court. Immigration enforcement involves administrative hearings and court proceedings where officers must appear and provide testimony. Deportation officers like Jonathan Ross give testimony to support prosecutions or administrative removal actions. They submit written declarations and reports that become part of the court record.

This means that anyone interested in finding out who's conducting immigration enforcement operations in a particular jurisdiction can simply look at court filings. You can find officer names, sometimes locations where they work, descriptions of their involvement in specific operations, and details about their roles in enforcement activities. These aren't secret documents. They're publicly filed court records that anyone can access through PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) and state court systems.

The details in these court filings can be quite specific. An officer's written declaration might describe their involvement in a car chase, explain their operational methods, or provide details about their training and experience. These are all details that become public record the moment the declaration is filed in court.

Court testimony creates additional exposure. If an officer testifies in a case, the transcript becomes part of the public record. The transcript includes the officer's name, the nature of their testimony, and details about the operations they're discussing. News outlets covering immigration cases often report on this testimony, further amplifying the public nature of the information.

So when DHS argues that doxing endangers officer safety, there's already a baseline of exposure happening through normal legal proceedings. Officers can't exactly hide their identities if they're testifying in court. The legal system requires them to put their identities on record as part of the due process protections that defendants are entitled to.

This creates an interesting tension in the doxing debate. DHS argues that publicizing officer identities is dangerous and should be prosecutable, but the legal system already requires that identities be public as part of judicial proceedings. An officer who testifies in court is already doxed in the most literal sense. Their name and identifying information are now part of the official court record.

The Jonathan Ross case exemplifies this tension. Ross shot and killed Minneapolis resident Renee Nicole Good. The incident came to national attention, and journalists sought to identify the officer involved. Federal officials apparently inadvertently aided the identification by providing reporters with specific details about Ross's involvement in previous enforcement operations, including an incident where he was dragged by a car. These details, combined with his official role, made identification possible.

But here's the thing: Ross had given court testimony and submitted declarations in cases related to his enforcement operations. Those court records already contained his name and details about his involvement in specific incidents. The information wasn't secret. It was sitting in court files that any journalist could access.

DHS Leadership's Aggressive Stance on "Doxing" and Threats of Prosecution

The DHS response to the publication of agent identities has been remarkably forceful. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem has publicly admonished journalists for naming officers in reporting on enforcement actions. During a CBS News interview, Noem objected when the journalist mentioned Jonathan Ross by name, characterizing the act as doxing and treating it as an unacceptable breach of security protocol.

This represents a significant hardening of the agency's public stance. DHS isn't just asking for privacy. It's treating the publication of officer identities as something that could potentially be prosecuted as a crime. The agency's official communication emphasizes that doxing endangers officers and their families, creating an implicit threat framework where identifying agents is presented as inherently dangerous behavior.

DHS spokeswoman Tricia Mc Laughlin told WIRED in January that the agency will "never confirm or deny attempts to dox our law enforcement officers" and emphasized that "doxing our officers put their lives and their families in serious danger." This language is carefully calibrated to maximize the perceived threat while maintaining ambiguity about whether publication of identities is actually dangerous.

The framing of doxing as something that endangers officers and families serves multiple purposes. It creates a sympathetic narrative around officer protection. It justifies stronger security measures and secrecy. It allows the agency to push back against transparency and accountability efforts. And it potentially creates legal grounds for prosecuting people who publicize officer identities under theories of harassment or endangerment.

But the threat level and the actual evidence of danger don't always align clearly. The agency asserts danger without providing extensive documentation of incidents where publicly identified officers experienced actual harm as a result of that identification. This doesn't mean the danger is imaginary. It means the agency is making a claim about risk that deserves scrutiny.

The aggressive stance also creates pressure on news organizations and journalists. If DHS is suggesting that naming agents could be prosecuted or could endanger lives, journalists have to weigh the public interest in knowing who conducted particular enforcement actions against concerns about officer safety. This creates a form of soft censorship where the threat of legal action or agency criticism affects editorial decisions.

Moreover, the agency's position seems to ignore the fact that its own employees are the ones making their identities public on LinkedIn. If doxing is so dangerous, why hasn't DHS implemented mandatory protocols requiring employees to remove identifying information from public platforms? Why hasn't the agency issued clear guidance that agents shouldn't maintain public LinkedIn profiles? The gap between the agency's stated concerns about officer safety and its lack of internal enforcement of security practices is notable.

An estimated 85% of DHS employee information on the ICE List was sourced from publicly available data, highlighting a significant privacy paradox. Estimated data.

LinkedIn's Role: The Platform That Refuses to Get Involved

LinkedIn's position in this situation is almost one of studied indifference. The platform is, in many ways, facilitating the entire problem. It's providing the infrastructure that makes it so easy to find and catalog federal agents. It's the tool that DHS employees are using to voluntarily publish their identifying information. And it's fundamentally complicit in creating the problem that then gets described as doxing.

Yet LinkedIn has declined to engage meaningfully with the issue. The company didn't respond to requests for comment about the presence of federal agents on its platform, the implications for their security, or whether the company has any policies around government employee profiles. LinkedIn maintains a studied neutrality about what kind of professional information users choose to share.

From LinkedIn's perspective, this makes sense. The company's entire business model depends on people being willing to share their professional information publicly. If LinkedIn took a strong stance that government employees shouldn't list their employers or that certain types of professionals should hide their identities, it would undermine the core value proposition of the platform. The company depends on users believing that being open about their professional lives is safe and beneficial.

But this creates a misalignment where LinkedIn users (including DHS employees) make decisions about what information to share based on their own assessment of risk, often without full awareness of how that information can be aggregated and used. Users might think posting their job title and employer is harmless. And in isolation, it often is. But when hundreds or thousands of federal agents post that same information on the same platform, it creates a comprehensive directory of federal enforcement personnel.

LinkedIn also doesn't proactively alert users to the implications of publishing certain information. The platform doesn't warn government employees that publicly listing their role as an immigration enforcement officer makes them easily discoverable. It doesn't explain how the aggregation of LinkedIn profiles can create comprehensive databases. It doesn't provide clear tools for government workers to maintain professional presence while protecting operational security.

The company's silence on this issue is, in itself, a choice. LinkedIn could implement policies specific to government employees. It could provide guidance on what information government workers should consider hiding. It could implement technical measures to make it harder to discover and aggregate profiles of federal agents. Instead, it defaults to the position that users can post whatever they want and it's not the platform's responsibility to manage the security implications.

The Data Broker Ecosystem: Signal Hire and Open Payrolls

Beyond LinkedIn, there's an entire ecosystem of data brokers and transparency platforms that contribute to the problem of easily identifying federal agents. These companies operate in the gray space between public records and private data, often making information searchable and accessible in ways that the original public record systems don't facilitate.

Signal Hire is one such company. It describes itself as a data broker specializing in lead generation, meaning it helps sales teams and recruiters find contact information for professionals. Signal Hire builds profiles of professionals by aggregating publicly available information from social media, professional networks, company websites, and other public sources. It then makes this information searchable and links directly to the underlying profiles.

For ICE officers on LinkedIn, Signal Hire doesn't just list their names and job titles. It provides direct links to their LinkedIn profiles, making it trivially easy to access the full range of information they've chosen to share on that platform. A recruiter using Signal Hire to find leads might discover federal agents as a byproduct of searching for people with relevant skills or experience.

Open Payrolls operates on a different basis but creates similar exposure. The platform maintains a searchable database of public employee salaries, arguing that it serves a transparency function by making government payroll information accessible. The data in Open Payrolls comes from Freedom of Information Act requests filed with government agencies. When the US Office of Personnel Management releases salary information for federal employees, that information ends up in Open Payrolls and becomes searchable.

This creates a situation where government transparency tools (FOIA and public payroll databases) are being repackaged and made more accessible by third-party companies. The information isn't stolen or secret. But it's being organized in ways that make it significantly easier to use than the original government databases.

The data broker industry operates in a legal gray area. The information these companies collect and distribute is publicly available. They're not breaking laws by aggregating it and making it searchable. But they're also not subject to the same security protocols or restrictions that might apply if the government made this information directly searchable on its own platforms.

Open Payrolls has stated that it has no affiliation with ICE List and that it has not received any complaints from government agencies about displaying public records on its platform. The company frames its function as promoting transparency about government spending. By making payroll information searchable, the company argues it's supporting accountability and public oversight of government.

But from a security perspective, the effect is that a federal employee's name, job title, agency, office location, and salary are all searchable in a single database. An adversary (or a journalist, or an activist) can search for ICE officers in a particular city or region and find their names and compensation information almost immediately. The information wasn't secret before, but now it's dramatically more accessible.

The Facial Covering Controversy: How Officer Safety Claims Are Used to Justify Anonymity

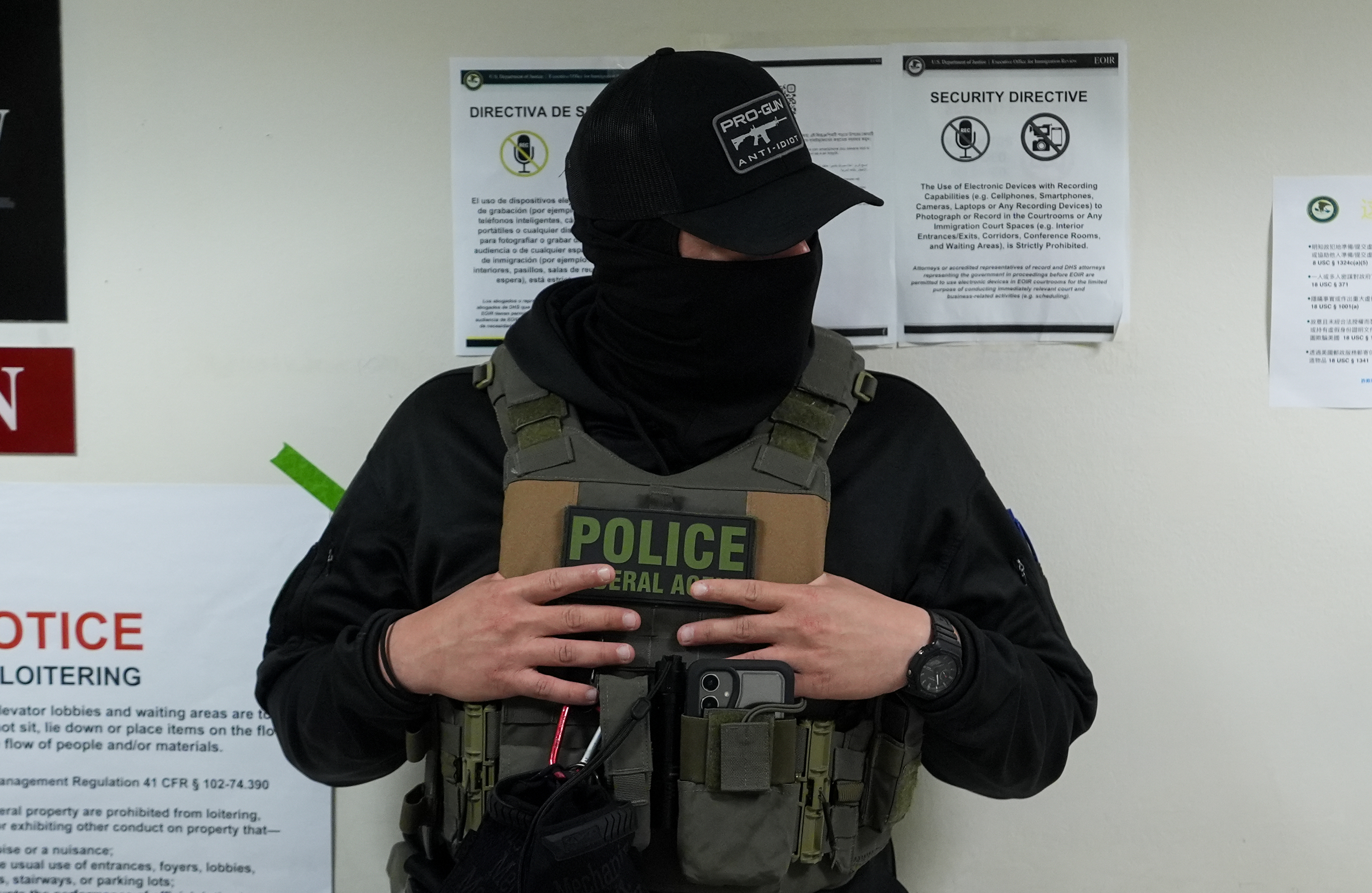

DHS has used the threat of doxing as an argument for why federal agents should be allowed to wear masks and facial coverings while conducting enforcement operations. This request has become part of legal disputes, particularly in Minnesota, where the state has been challenging DHS practices around anonymous enforcement operations.

In legal filings related to these cases, CBP officials have made explicit arguments that the rise of doxing, advanced facial recognition technology, and social media threats create operational risks that justify allowing officers to wear masks. A CBP official overseeing Border Patrol operations submitted a declaration arguing that protective facial coverings are necessary to protect officer identities in the modern threat environment.

This claim serves a particular function in these legal disputes. If the government can convince courts that officer safety requires protective measures, it can justify policies that limit public ability to identify officers conducting enforcement operations. The reasoning is that doxing is a real threat, anonymous officers are safer, and therefore agencies should be permitted to use facial coverings or other identity protection measures.

But here's the complication: if officers are voluntarily posting identifying information on LinkedIn, the threat level from doxing seems somewhat overstated. If someone can simply visit LinkedIn and find an officer's profile, does it matter whether they can see the officer's face during an enforcement operation? The anonymity from facial coverings appears to protect against a specific moment in time (the enforcement operation itself) but doesn't address the broader reality that the officers are identifiable through other means.

This creates a logical inconsistency in the government's position. The agency argues that officer safety requires protective measures like masks because doxing is too dangerous. But the agency simultaneously fails to implement policies that would address the root of the problem: agents voluntarily publishing identifying information on public platforms.

The facial covering issue also raises questions about whether officers deserve special anonymity protections that other law enforcement or public officials don't receive. Police officers, federal marshals, and FBI agents generally don't get to wear masks during enforcement operations. The public has a legitimate interest in knowing who is conducting law enforcement actions against them. Anonymous enforcement creates accountability problems.

Yet DHS wants to extend special anonymity protections specifically to immigration enforcement officers. The justification involves officer safety, but it also conveniently removes a mechanism for public accountability and transparency around immigration enforcement practices.

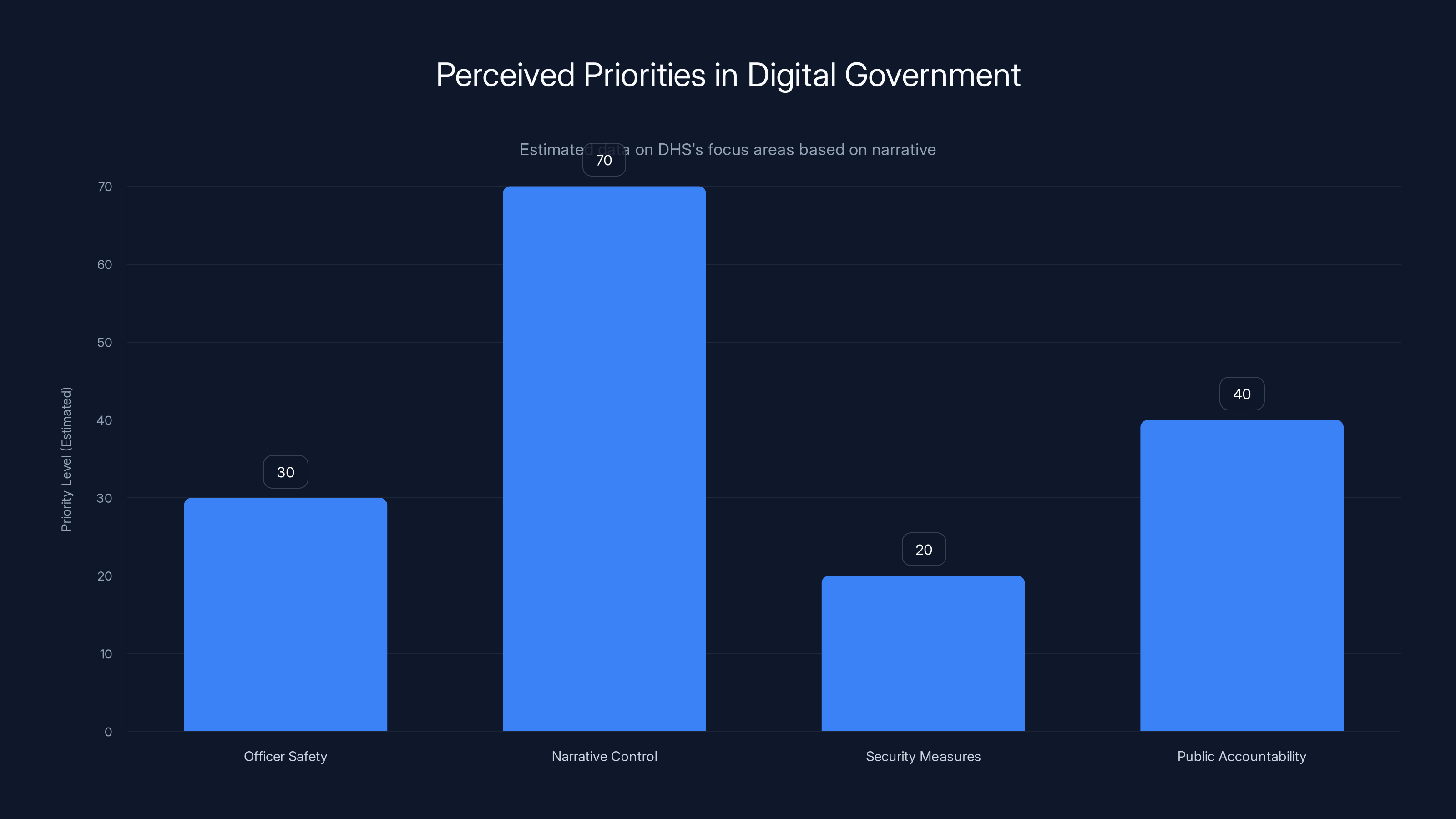

DHS perceives a high threat level from doxing (rated 8/10), but documented incidents of harm are significantly lower (rated 2/10). Estimated data based on narrative.

How Researchers and Activists Built ICE List: The Technical and Methodological Side

Understanding how ICE List was actually built is important because it reveals the relative simplicity of aggregating publicly available information about federal agents. The site isn't the product of sophisticated hacking or breach of secure systems. It's a straightforward data aggregation project using publicly accessible sources.

The site operates as a crowdsourced wiki in the Wikipedia model. Volunteers can submit information about agents they believe work for ICE or other DHS agencies. The site's moderators verify information and add verified tags when they have confidence in the accuracy. This crowdsourcing model means the project can scale to include thousands of profiles without requiring any single person to do all the work.

The sourcing methodology is transparent and includes citations. When profiles link information to Open Payrolls or Signal Hire, those citations are visible. When information comes from LinkedIn, that's often documented. This actually gives the project some credibility because you can trace where the information comes from. You're not dealing with mysterious claims about breached data. You're dealing with links to publicly available sources.

The categorization structure allows for easy browsing and discovery. You can view profiles by agency, by regional office, by role, or by verification status. This organization makes the database useful for different purposes. Someone interested in which agents work in a particular city can easily find that information. Someone interested in agents with particular specializations can search for that.

The site's explicit policies against harassment, home address publication, and misuse attempt to position it as a documentation project rather than a targeting database. The creators argue they're making information about public officials transparent, not facilitating harassment or violence. Whether you believe that distinction is meaningful depends partly on your views about transparency and accountability in government.

The simplicity of the underlying data collection is probably the most important point here. The creators didn't need sophisticated tools or special access. They needed time, organizational ability, and knowledge of where publicly available information lived. They could find LinkedIn profiles through LinkedIn's own search interface. They could access payroll information through Open Payrolls. They could get court records through PACER. None of these sources are restricted or secret. They're all available to anyone.

This is fundamentally different from traditional doxing, which typically involves obtaining private information that isn't already public. ICE List aggregates information that's already public and organizes it for easier discovery. That's a meaningful difference, even if the outcomes (making people easily identifiable) look similar.

The Jonathan Ross Case: When Operational Details Become Public

The shooting of Renee Nicole Good by ICE officer Jonathan Ross became a flashpoint in the broader conversation about officer identity and transparency. When Good was killed during an enforcement operation in Minneapolis, journalists sought to identify the officer involved. The identification process revealed how operational details and officer information can become publicly known through multiple channels.

Ross had been involved in a previous enforcement operation where he was dragged by a car. This incident itself became part of the public record because it was litigated in court. The details of what happened and Ross's involvement were part of court proceedings and potentially media coverage of that incident. When journalists later tried to identify the officer in the Good shooting, federal officials apparently provided details about the car-dragging incident that made identification possible.

The interesting part is that this information was already public or semi-public in multiple ways. Court records documented the incident. Ross had testified in proceedings related to it, putting his name on the record. The operational context was knowable if you had access to the right court files and public records.

The case illustrates how officer identities become public not through any single dramatic breach, but through the accumulation of operational details, court proceedings, and incremental public disclosures. An officer isn't necessarily anonymous just because their home address is secret. If their name is on court records, if their operational history is documented, if they're conducting visible enforcement operations, their identity can be reconstructed through multiple overlapping sources of public information.

When DHS objected to journalists naming Ross, they were treating his identification as improper. But the information that made identification possible was either already public (through court records) or was disclosed by federal officials themselves (the details about the car-dragging incident). In that sense, the officer's identity wasn't protected by anything other than the historical fact that journalists hadn't connected the publicly available dots.

This raises a hard question about what officer anonymity actually means in practice. If information is scattered across multiple public sources, is an officer's identity really "protected" just because journalists haven't written a story that aggregates those sources? Or is the protection more illusory, dependent on public ignorance rather than actual security measures?

The Gap Between Policy and Practice: Why DHS Isn't Enforcing Its Own Security Standards

Probably the most damning aspect of this situation is the gap between DHS rhetoric about officer safety and the agency's actual internal practices. If doxing is genuinely dangerous and if officer safety is the paramount concern, why hasn't DHS implemented mandatory policies requiring agents to remove or reduce identifying information from public professional networks?

The agency could issue a directive that DHS employees should not maintain public LinkedIn profiles listing their agency affiliation. It could require that profiles be set to private or that certain information be hidden. It could discipline employees who violate these policies. Large government agencies have the authority to issue security protocols around employee social media use.

Yet DHS doesn't appear to have done this. Instead, the agency relies on vague guidance to "be mindful of what you post on social media" without specifically addressing LinkedIn or professional networking platforms. The guidance is non-binding and doesn't explain specific risks or consequences.

This suggests that either the agency doesn't truly believe the doxing threat is as severe as its public rhetoric suggests, or the agency is content to let individual employees take risks because enforcing stricter policies would be politically costly or operationally inconvenient.

There's also the matter of institutional culture. If the organization doesn't enforce strong social media security policies internally, individual employees get the message that having a public professional presence is acceptable. Younger employees might see agency leadership maintaining their own public profiles and conclude that it must be safe to do the same. The organization's implicit practices undermine its explicit threats about doxing dangers.

The lack of internal enforcement also creates a situation where employees might face discipline for sharing information with journalists or protesters, but face no consequences for posting the same information on LinkedIn. This inconsistency reveals that the agency's real concern might be more about controlling the narrative and limiting public oversight than about actually protecting officer safety.

If DHS were serious about protecting officer identities, it would start with its own employees. It would require stricter social media protocols. It would provide training on security risks. It would discipline violations. The fact that this isn't happening suggests the agency is more focused on pushing back against external publication of information than on addressing the root problem of voluntary self-disclosure.

Estimated data suggests that while the US leans towards officer anonymity, other democracies like the UK and Australia prioritize public accountability more strongly.

What Employees Get Wrong About Professional Networks and Operational Security

Many federal employees probably don't understand the security implications of maintaining a public LinkedIn profile. They see the platform as a professional tool for networking and career advancement. They don't necessarily think about how seemingly innocent information can be aggregated and used.

When you list your employer as "Immigration and Customs Enforcement" and your job title as "Deportation Officer," that's information you're sharing openly. It doesn't feel dangerous. It's not a secret or embarrassing. It's just your job. But when thousands of people do this on the same platform, it creates a comprehensive directory of federal enforcement personnel.

Additionally, your LinkedIn profile connects you to a network of other people. Those connections might reveal patterns about where you work, what operations you're involved in, or who your professional contacts are. An adversary or researcher could potentially map out organizational structures and operational relationships by analyzing these connection networks.

Your employment history on LinkedIn might reveal details about previous assignments or postings. If you've worked in immigration enforcement in multiple cities, your LinkedIn profile documents that history. Combined with information about when you were in each location, it could reveal patterns about where enforcement operations were concentrated.

Your educational background and certifications might reveal details about your training and specialization. If your profile indicates you have specialized training in a particular type of enforcement operation, that itself could be operationally sensitive information.

Most federal employees probably aren't thinking about these second-order implications when they maintain their profiles. They're thinking about career advancement, networking, and maintaining a professional online presence that's increasingly expected in most fields. They're not conducting a security analysis of what their aggregate profile information reveals.

This isn't necessarily stupidity or carelessness on the part of employees. It's a rational response to institutional incentives and lack of clear guidance. If the organization uses LinkedIn for recruiting, if career advancement depends on having a visible professional presence, if there's no clear punishment for maintaining a public profile, then most people will maintain one. Individual security concerns feel abstract compared to concrete career benefits.

The Legal Questions: Can Identifying Federal Agents Actually Be Prosecuted?

DHS has suggested that publishing officer identities could be prosecuted, but it's unclear what specific criminal statute would apply or whether such prosecutions would succeed. This is an important legal question because DHS's threatened prosecutions might be legally dubious even if they succeed in intimidating people.

Traditional harassment or threatening statutes wouldn't necessarily apply just to identifying someone's name and job. You can publicly identify someone without harassing or threatening them. Distinguishing between protected speech (identifying a public official and their role) and unprotected speech (credible threats or harassment) requires careful legal analysis.

There are some theories under which identifying someone could potentially be prosecuted. Providing information that facilitates a crime could potentially be illegal in certain contexts. If someone identified an officer and that identification was followed by violence, prosecutors might try to construct a theory that the identification facilitated the violence. But proving that connection would be legally complex.

There's also the question of whether there's some federal statute specifically criminalizing doxing. No such statute exists at the federal level currently. States have various laws addressing doxing and privacy violations, but these laws are relatively new and their application to political speech remains contested.

DHS's threats of prosecution might be more about intimidating people and controlling the narrative than about actually being able to prosecute based on clear legal grounds. The ambiguity serves a purpose. It creates fear and chilling effects on speech without requiring actual prosecutions that might fail on legal grounds.

This creates a troubling dynamic where an agency can effectively censor information by threatening prosecution for doxing without having clear legal authority to actually prosecute. Journalists and outlets might avoid reporting on officer identities not because there's a clear law against it, but because they're uncertain about the legal risks and DHS is aggressive about asserting those risks.

The Broader Context: How Transparency and Accountability Intersect With Officer Safety

The entire situation exists at the intersection of two legitimate concerns: the need to protect people's safety and the need for public transparency and accountability in government enforcement actions. Neither concern is imaginary or illegitimate. But they're in tension.

On one hand, federal agents do face genuine safety risks. People who are opposed to immigration enforcement have sometimes targeted agents with violence or threats. Officer safety is a legitimate concern that shouldn't be dismissed. Ensuring that agents can do their jobs without facing harassment or threats is reasonable.

On the other hand, the public has a legitimate interest in knowing who is conducting law enforcement against them. The identity of agents involved in enforcement operations is relevant information for people affected by those operations. It's relevant for journalists trying to hold the government accountable. It's relevant for people trying to understand patterns in enforcement. Complete anonymity for government agents makes accountability harder.

Most democratic legal systems have concluded that the public interest in knowing who is conducting law enforcement against them outweighs agent safety concerns. Police officers in most jurisdictions don't get to enforce laws while wearing masks and hiding their identities. Their names become public when they're involved in significant incidents. The public interest is generally considered to trump anonymity preferences.

Yet DHS wants to extend special anonymity protections specifically to immigration enforcement. Part of this might be justified by safety concerns. But it also conveniently removes a mechanism for accountability and makes it harder for the public to understand and scrutinize immigration enforcement practices.

The situation is complicated by the fact that DHS's supposed concern for officer safety hasn't led to actual security measures (like restricting social media use). Instead, it's led to aggressive pushback against journalists and transparency efforts. This suggests the concern might be more about controlling the narrative than about actual safety.

Estimated data suggests DHS prioritizes narrative control over officer safety and public accountability, as indicated by the lack of security measures.

Platform Responsibility and the Future of Employee Privacy

This situation raises questions about what responsibility platforms like LinkedIn have for the security implications of the information their users share. LinkedIn's current approach is that users are responsible for their own privacy settings and disclosure choices. The platform doesn't preemptively restrict what professionals can post about their employers or roles.

But as data aggregation and analysis tools become more sophisticated, the collective implications of individual disclosure decisions become more significant. When a thousand people individually decide to disclose their employer, the aggregate effect is to create a comprehensive directory. That's different from the implications of any single disclosure.

There are arguments for platforms having greater responsibility here. LinkedIn could implement special protections or guidance for government employees. It could make it harder to discover and aggregate profiles of federal agents. It could warn users when their information might be operationally sensitive.

But there are also arguments against. If LinkedIn implements special policies for government employees, it effectively privileges certain classes of users and restricts their ability to participate in the platform as fully as other users. It treats government employees as inherently deserving of special anonymity, which raises its own concerns about accountability.

The tension here is genuine. There's no perfect solution that fully protects both individual privacy and public transparency. Different democracies will probably come to different conclusions about where to draw the line.

What's clear is that the current situation, where federal agents post identifying information on LinkedIn while their agencies threaten prosecution for doxing, is incoherent. If DHS is serious about officer safety, it needs to address the root problem: its own employees voluntarily publishing information. That's a message that needs to come from inside the organization, not from aggressive external enforcement against journalists and activists.

The Role of Journalism in Balancing Accountability and Safety

Journalists covering immigration enforcement face difficult decisions about whether and how to identify officers involved in significant incidents. There's a legitimate public interest in knowing who conducted a particular enforcement operation. But there's also the question of what risks might flow from publication.

The case of Jonathan Ross illustrates this tension. Journalists had legitimate reasons for trying to identify the officer who shot Renee Nicole Good. The incident was significant and raised questions about enforcement practices. Identifying the officer helped the public understand what happened. But DHS objected to the identification on safety grounds.

How should journalists balance these concerns? One approach is to avoid publishing identities even when they're publicly available, out of an abundance of caution about officer safety. Another approach is to publish identities as part of normal accountability journalism, treating police and federal agents like any other public officials whose actions are subject to public scrutiny.

There's probably a middle ground where journalists use judgment about whether identification is necessary for the story and whether the public interest in knowing the officer's identity outweighs legitimate safety concerns. But the DHS approach of treating all identification as doxing deserves to be questioned rather than reflexively accommodated.

Journalists should also be critical of DHS's framing of the issue. The agency is blaming journalists for officer identification while failing to implement basic security measures within its own organization. That discrepancy is worth reporting and analyzing.

Comparing US Practice to Other Democracies: How Do Other Countries Handle This?

Other democracies have grappled with similar questions about officer anonymity and public accountability in law enforcement. The approaches vary based on different legal traditions and constitutional frameworks.

In many European countries, privacy protections are stronger than in the US, which might suggest more anonymity for officers. But these countries also generally require more extensive public accountability for police and law enforcement. The balance is different, but the tension remains.

Canada has debated this issue in the context of protest policing and enforcement operations. Canadian law enforcement has sought greater anonymity protections, but the country's privacy framework and courts have often limited those protections based on public interest in accountability.

Australia and the UK have faced similar questions about whether immigration enforcement officers deserve special anonymity protections. The general legal conclusion in these jurisdictions is that law enforcement accountability generally outweighs anonymity preferences, even when officer safety is a concern.

These comparisons suggest that the US position isn't standard among democracies. Most other democracies have concluded that public accountability for law enforcement is important enough to outweigh officer anonymity preferences. The fact that DHS is pushing for special anonymity protections for immigration enforcement is somewhat unusual.

What Needs to Change: Solutions and Recommendations

Addressing this situation requires changes at multiple levels: organizational policy within DHS, individual employee behavior, platform policies at LinkedIn, and journalistic standards.

First, DHS needs to implement clear, mandatory social media policies for employees. If officer safety is genuinely the concern, the agency should require employees to remove or hide identifying information from public professional networks. The guidance should be specific, binding, and enforced through disciplinary measures for violations.

Second, LinkedIn should consider implementing better tools and guidance for government employees. This could include warnings when employees list sensitive employers, privacy settings that are more restrictive by default for government employees, or clearer guidance about the risks of maintaining public profiles.

Third, journalists should develop clear standards for when to publish officer identities. These standards should balance public interest in accountability with legitimate safety concerns. But the standards shouldn't defer completely to DHS claims about safety without independent assessment.

Fourth, Congress should clarify what doxing actually is and what laws, if any, apply to publishing public information about federal employees. The current ambiguity serves DHS's intimidation purposes more than it serves justice or clarity. A clear legal standard would help journalists and media outlets understand their actual legal risks.

Fifth, civil rights organizations should continue to monitor and report on DHS's actual threats against officers and any patterns of violence that might justify special anonymity protections. The agency's claims about safety should be subjected to empirical scrutiny. If officers are actually facing significant violence related to identification, that's important information. If the threat is more theoretical, that's also important information.

The Broader Implications for Government Transparency and Data Privacy

This situation also raises broader questions about how government transparency and data privacy interact in the digital age. The traditional model involved government agencies controlling information about themselves, with transparency mechanisms like FOIA allowing people to request information. But now, much information about government employees is available through their own voluntary disclosures on public platforms.

This creates a new category of public information: information that's technically public but that the government didn't intend to be easily accessible. Your LinkedIn profile is public in the sense that you shared it publicly. But the government didn't organize or distribute it. The fact that ICE List could aggregate it was somewhat surprising to DHS, even though the information wasn't stolen or hacked.

As platforms become more comprehensive databases and data aggregation tools become more powerful, the distinction between information that's technically public and information that's practically searchable becomes increasingly important. Something can be technically public while being practically private if it's hard to find.

DHS's response to this situation seems to be to push for greater controls over what information is public and searchable, particularly about its own employees. But a better approach might be for government to come to terms with the fact that in a digital age, comprehensive personal information about employees will likely be discoverable one way or another. The solution is better internal security measures and clearer public accountability, not less transparency.

Conclusion: Coherence and Accountability in Digital Government

The situation with ICE agents doxing themselves on LinkedIn is fundamentally about incoherence. DHS claims officer safety is paramount. Yet the agency fails to implement basic security measures within its own organization. DHS threatens prosecution for publishing information while that information is readily available on public platforms maintained by its own employees.

This incoherence matters because it suggests the agency's real concern might not be officer safety but rather controlling the narrative around immigration enforcement. If the concern were genuine safety, DHS would start with mandatory security policies for employees. It would restrict LinkedIn use or require stricter privacy settings. It would work with platforms to protect officer identities. Instead, it's focused on threatening journalists and activists who publish information that's already public.

The people paying the price for this incoherence are journalists trying to cover immigration enforcement and activists trying to hold the government accountable. They're navigating threats of prosecution and accusations of doxing, even though the information they're reporting is public or semi-public and available through legitimate means.

DHS needs to make a choice: either officer safety is the priority, in which case implement real security measures, or accountability is the priority, in which case accept that officer identities will be publicly known. The current approach, which claims safety concerns while refusing to implement basic security measures, isn't coherent or credible.

The presence of thousands of federal immigration enforcement officers on LinkedIn is not a security failure caused by external actors. It's a policy failure caused by lack of internal security protocols and ambiguous guidance. DHS can address this whenever it's genuinely ready to prioritize officer safety over narrative control.

Until then, the spectacle of federal agents claiming to be victimized by doxing while voluntarily publishing their identities on professional networks will continue. It's incoherent policy colliding with the realities of digital life. And it's not a problem that can be solved by threatening journalists or activists. It can only be solved by DHS getting serious about the security of its own employee information.

The broader lesson here is about institutional accountability in a digital age. Governments can't credibly claim that transparency endangers safety while refusing to implement basic internal security measures. They can't threaten prosecution for doxing while their own employees post identifying information publicly. These contradictions don't just reveal hypocrisy. They suggest that the real priority isn't safety but control.

As digital tools make information increasingly accessible, institutions will have to come to terms with this reality. The solution isn't to suppress information or threaten people who publish facts. The solution is to operate with the assumption that significant information about your operations will eventually become public, and to build accountability and legitimacy on that basis rather than on secrecy or control.

FAQ

What exactly does it mean when DHS claims ICE agents are being "doxed"?

DHS uses "doxing" to describe the public identification of ICE officers, but the term is actually misleading in this context. True doxing typically involves publishing private information obtained without authorization (like home addresses from hacked databases). In this case, most of the identifying information comes from sources that agents themselves made public, particularly LinkedIn profiles where they voluntarily listed their employment with ICE. The rebranding of public identification as "doxing" appears designed to create a more sympathetic narrative around officer anonymity while obscuring the fact that much of the information was self-disclosed.

How did ICE List actually obtain the information about federal agents?

ICE List primarily aggregated information from publicly available sources rather than conducting any unauthorized data theft. Researchers used LinkedIn's own search interface to find profiles of people self-identifying as ICE employees, accessed publicly available payroll databases like Open Payrolls (which contains information released through Freedom of Information Act requests), and found information through data brokers like Signal Hire that compile lead generation databases. In essence, ICE List took information that was already scattered across multiple public platforms and organized it into a searchable database, making it easier to discover patterns that already existed.

Why don't DHS employees just remove their LinkedIn profiles or hide their information?

DHS hasn't mandated that employees restrict their LinkedIn presence, so individual employees are left to make their own risk assessments. Most federal workers see professional networking as beneficial for career advancement within government and potentially for future private sector employment. LinkedIn profiles help with promotions, transfers, and networking at professional conferences. Without clear organizational guidance explaining the security risks and without enforcement mechanisms for removing identifying information, employees rationally choose to maintain visible profiles. The problem is institutional failure rather than individual employee negligence.

Is there a legal basis for DHS to prosecute people for naming ICE agents?

DHS's threats of prosecution for "doxing" are legally ambiguous. No federal statute specifically criminalizes doxing, and traditional harassment or threatening statutes generally don't apply just to publishing someone's name and job title. While some state laws address doxing specifically, these are relatively new and their application to political speech about public officials remains contested. DHS's threats of prosecution may be more effective as intimidation than as actual legal authority, creating a chilling effect on journalism and activism by making people uncertain about their legal exposure.

How does this situation affect national security or officer safety in practice?

While officer safety is a legitimate concern, there's insufficient public evidence that identifying immigration enforcement officers in reporting has actually led to violence or threats against identified officers. DHS asserts danger without providing extensive documentation of incidents directly caused by public identification. Meanwhile, the agency simultaneously fails to implement basic internal security measures that would actually protect officer identities. This gap between stated concerns and actual practices suggests the priority might be more about narrative control than genuine safety considerations.

What can federal employees do to protect their identities while maintaining professional presence?

Federal employees concerned about operational security can restrict their LinkedIn profiles in several ways: set profiles to private or semi-private, remove or hide agency affiliation, use restricted titles that don't identify their specific role, limit who can see their employment history, disable the profile from appearing in search results, and avoid connecting with large numbers of people in similar roles. Many government employees maintain professional presence on LinkedIn while still limiting the amount of identifying information they share. The key is intentional configuration of privacy settings rather than assuming defaults are secure.

How do other democracies balance officer anonymity with public accountability?

Most other democracies have concluded that public accountability for law enforcement generally outweighs officer anonymity preferences, even in cases where officer safety is a concern. Police and enforcement agents in Canada, Australia, the UK, and most European countries don't get to enforce laws anonymously. While privacy protections exist in various forms, they generally don't extend to complete anonymity for officers involved in significant enforcement actions. The US position of seeking special anonymity protections for immigration enforcement is somewhat unusual among democracies.

Should journalists refrain from naming ICE agents to protect officer safety?

Journalists should balance the public interest in knowing who conducted specific enforcement operations against legitimate safety concerns, but they shouldn't defer completely to government claims about safety without independent assessment. The identity of law enforcement personnel conducting significant operations is generally relevant to public understanding and accountability. While individual judgment is appropriate about whether identification is necessary for a particular story, wholesale abstention from naming officers sets a problematic precedent where government agencies can effectively suppress information by threatening prosecution and invoking safety concerns without providing evidence.

What specific changes would actually improve the situation?

Meaningful improvements would require action at multiple levels: DHS implementing mandatory, specific social media policies for employees with enforcement mechanisms; LinkedIn providing better tools and guidance for government employees about security risks; Congress clarifying what legal protections actually exist around publishing public information about federal employees; and journalists developing clear standards that balance accountability with legitimate safety concerns. The first step, though, is internal DHS action to address why its own employees are voluntarily publishing identifying information despite the agency's public claims about safety concerns.

Key Takeaways

- DHS threatens prosecution for doxing while its own employees voluntarily publish identifying information on public professional networks like LinkedIn

- ICE List aggregated mostly publicly available data from LinkedIn, payroll databases, and data brokers rather than conducting unauthorized breaches

- The gap between DHS security claims and actual internal policies suggests the priority is narrative control rather than genuine officer safety

- Multiple overlapping data sources (court records, payroll databases, LinkedIn, data brokers) already make federal agents easily identifiable regardless of journalistic reporting

- Meaningful solutions require DHS to implement mandatory security policies for employee social media use rather than threatening journalists for publishing public information

Related Articles

- Under Armour Cyberattack 2025: What 7M Users Need to Know [Guide]

- Why We're Nostalgic for 2016: The Internet Before AI Slop [2025]

- When Federal Enforcement Changes Everything: How Communities Adapt [2025]

- DOGE Social Security Data Breach: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]

- ICE's $50M Minnesota Detention Network Expands Across 5 States [2025]

- How Communities Respond to Immigration Enforcement Crises [2025]

![ICE Agents Doxing Themselves on LinkedIn: Privacy Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ice-agents-doxing-themselves-on-linkedin-privacy-crisis-2025/image-1-1769105382415.jpg)