Understanding the Minnesota ICE Ruling That Changed Everything

Last January, something happened in a federal courtroom in Minnesota that rippled through immigration enforcement nationwide. A federal judge made a ruling that seemed obvious on its surface but contradicted what immigration agents had apparently been told internally. US District Court Judge Jeffrey Bryan decided that when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents want to enter someone's home without permission, they need an actual judicial warrant signed by an actual judge. Not an internal administrative document. Not a memo. A real warrant from the judiciary, as reported by AP News.

The case centered on Garrison Gibson, a Liberian national who'd been living in Minnesota under ICE supervision for years. On January 11, early in the morning while his family slept, ICE agents showed up at his door. Gibson refused to let them in. He asked to see a judicial warrant. The agents left, then came back with more people, pepper spray, and a battering ram. They smashed through his door without ever showing him the court-signed warrant he'd demanded. Only after they had him handcuffed did they produce what they called a warrant. It turned out to be an administrative document signed by an ICE supervisor, not a judge, as detailed by Fox 9.

What made this ruling significant wasn't just the outcome for Gibson, though his immediate release after the judge's order mattered. The real significance was that the court directly addressed a practice that had apparently been happening systematically. Internal ICE guidance—a memo that whistleblowers had exposed—supposedly told agents that administrative warrants were sufficient to enter homes without consent. Judge Bryan's decision said no. That's not how the Constitution works, as explained in Cleveland.com.

The Fourth Amendment and What It Actually Protects

Here's the thing about the Fourth Amendment: it's not really about whether the government can arrest you. It's about the process. It says the government can't just search your property or arrest you in your home without a warrant. But not just any piece of paper counts as a warrant. The amendment specifically requires that warrants be signed by a neutral judge who's reviewing the facts and deciding whether probable cause actually exists.

This distinction matters because it creates a check on executive power. If the government could issue its own warrants to itself, there'd be no meaningful judicial oversight. As constitutional scholars have noted, allowing the executive branch to decide whether it has the authority to search someone's home is exactly backwards from what the Constitution requires. The whole point of a warrant is that someone independent from law enforcement decides whether the government's request is reasonable, as discussed in Lawfare.

The Fourth Amendment says: "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

What that language means in practice: government officials need to convince a judge that probable cause exists before they can enter a home by force. They need to present facts. The judge needs to independently verify those facts are credible. Then the judge decides. This isn't a rubber stamp process. It's supposed to be an actual check.

ICE uses what's called an administrative warrant for immigration enforcement. These documents are signed by ICE supervisors, not judges. They authorize agents to arrest people for immigration violations and detain them. But here's the key distinction: administrative warrants were never intended to authorize forcible entry into homes. They're designed for arrests in public places or situations where someone's already consented to agents entering their property, as highlighted by Military.com.

The problem ICE apparently faced was operational. If agents had to get judicial warrants to enter homes, the process would take longer. They'd need to present evidence to judges. Judges might reject applications if the evidence wasn't strong enough. This slowed down enforcement operations. So someone in ICE leadership apparently decided to interpret the rules differently internally. The directive basically said: treat your administrative warrant as sufficient authority to enter homes without judicial oversight, as noted by WebProNews.

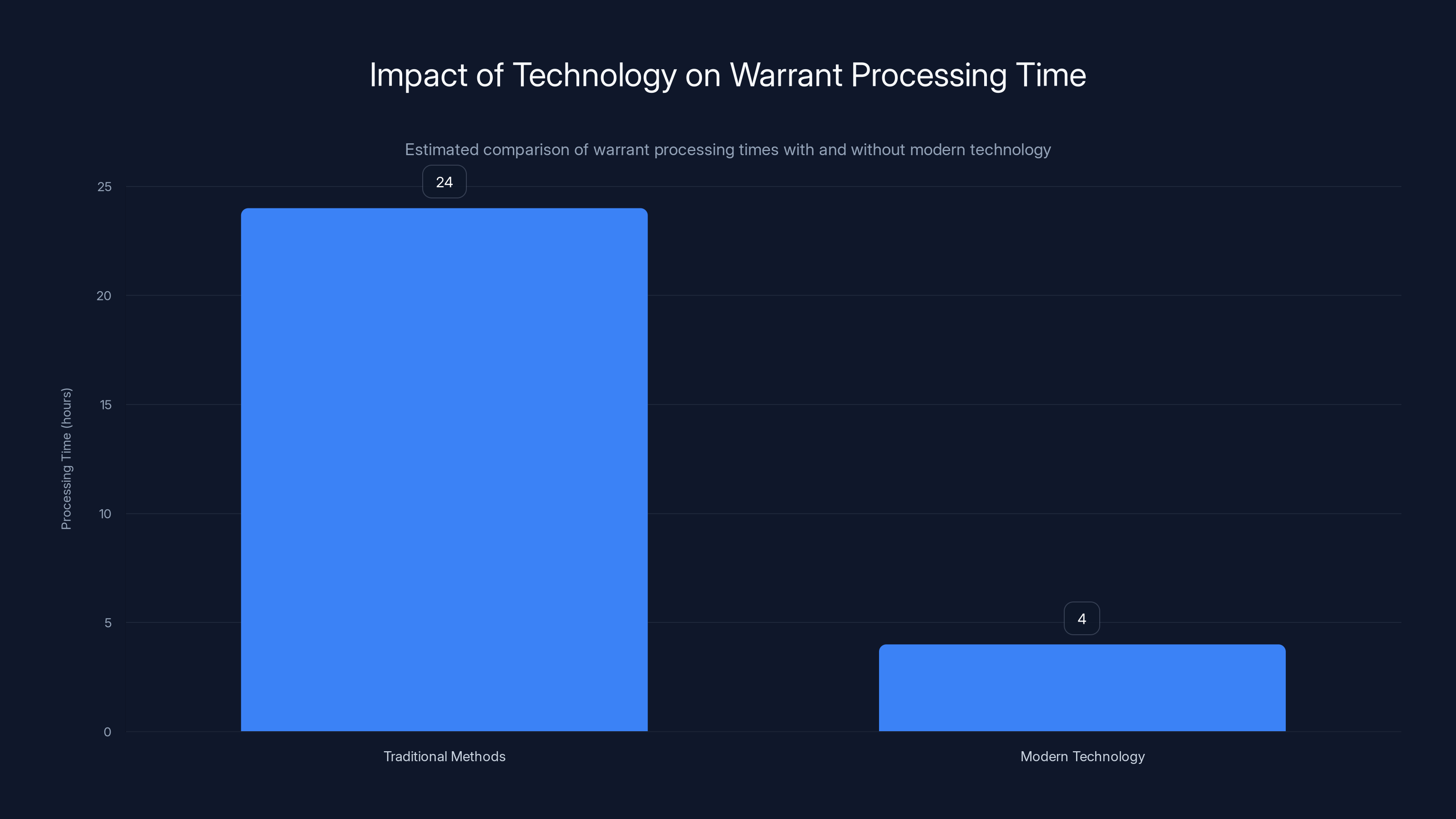

Estimated data shows that modern technology significantly reduces warrant processing time from 24 hours to 4 hours, highlighting its efficiency in judicial review processes.

Inside the Secret ICE Memo That Started Everything

Whistleblowers working with a nonprofit legal organization called Whistleblower Aid exposed the internal ICE guidance that made this whole case significant. The document centered on Form I-205, an internal administrative document known as a Warrant of Removal or Deportation. According to whistleblower complaints, the memo instructed ICE officers that an I-205 signed by ICE supervisors was sufficient authority to enter homes without consent, as revealed by The New York Times.

This wasn't a public policy. This was internal guidance that was circulated within the agency and briefed verbally to officers. Many agents probably never saw the formal written version. They just absorbed the instruction through training and conversation. That's how bureaucratic cultures work. Instructions get passed down, refined, interpreted, and eventually become standard practice even if they're never written down clearly.

The problem with this approach is that it skipped the judicial check entirely. Under the Fourth Amendment, that check is mandatory for home entries. You can't just eliminate it through an internal memo. But ICE apparently tried to do exactly that, as discussed in My North News.

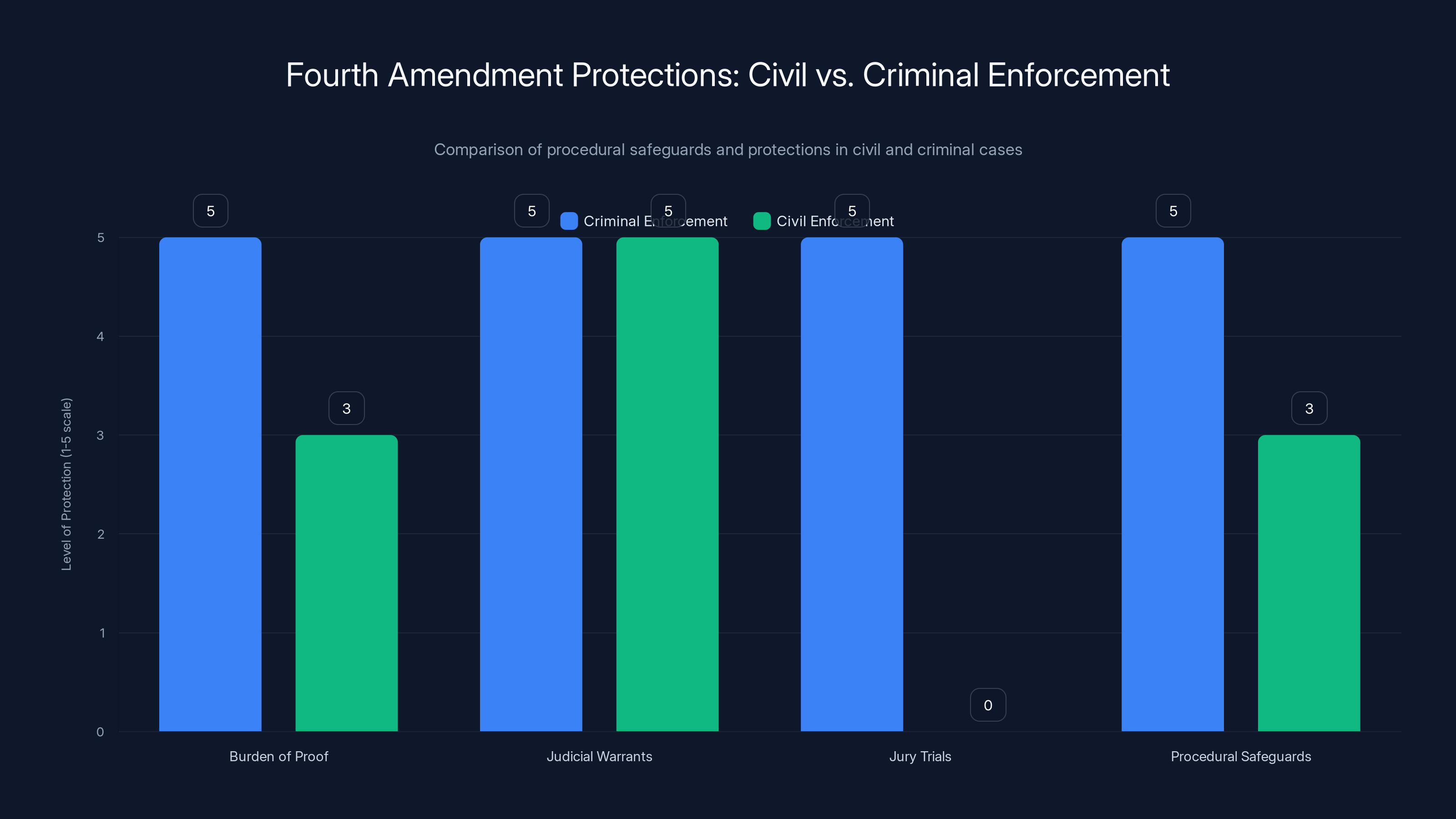

Why did ICE leadership think they could do this? Partly because immigration enforcement has historically operated with different rules than criminal law enforcement. Immigration violations are civil matters, not criminal ones. So some people in government argued that immigration enforcement shouldn't require the same level of judicial oversight as criminal investigations. That argument has some legal traction in certain contexts. But the Fourth Amendment doesn't distinguish between civil and criminal home entries. Your home gets the same protection either way.

Whistleblower Aid released materials showing how the guidance was supposedly implemented. Officers were told they could rely on the administrative warrant. Some versions of the instruction apparently included language suggesting that judges simply weren't necessary for these entries. The organization that represented whistleblowers called this out as a clear constitutional violation, as highlighted by MPR News.

Judge Bryan's decision explicitly referenced this guidance problem. Even though the ruling didn't assess the memo's legality directly (that would require a different type of case), the judge made clear that whatever the memo said, it contradicted the Constitution. Agents can't rely on administrative warrants to justify forcible home entry. Period.

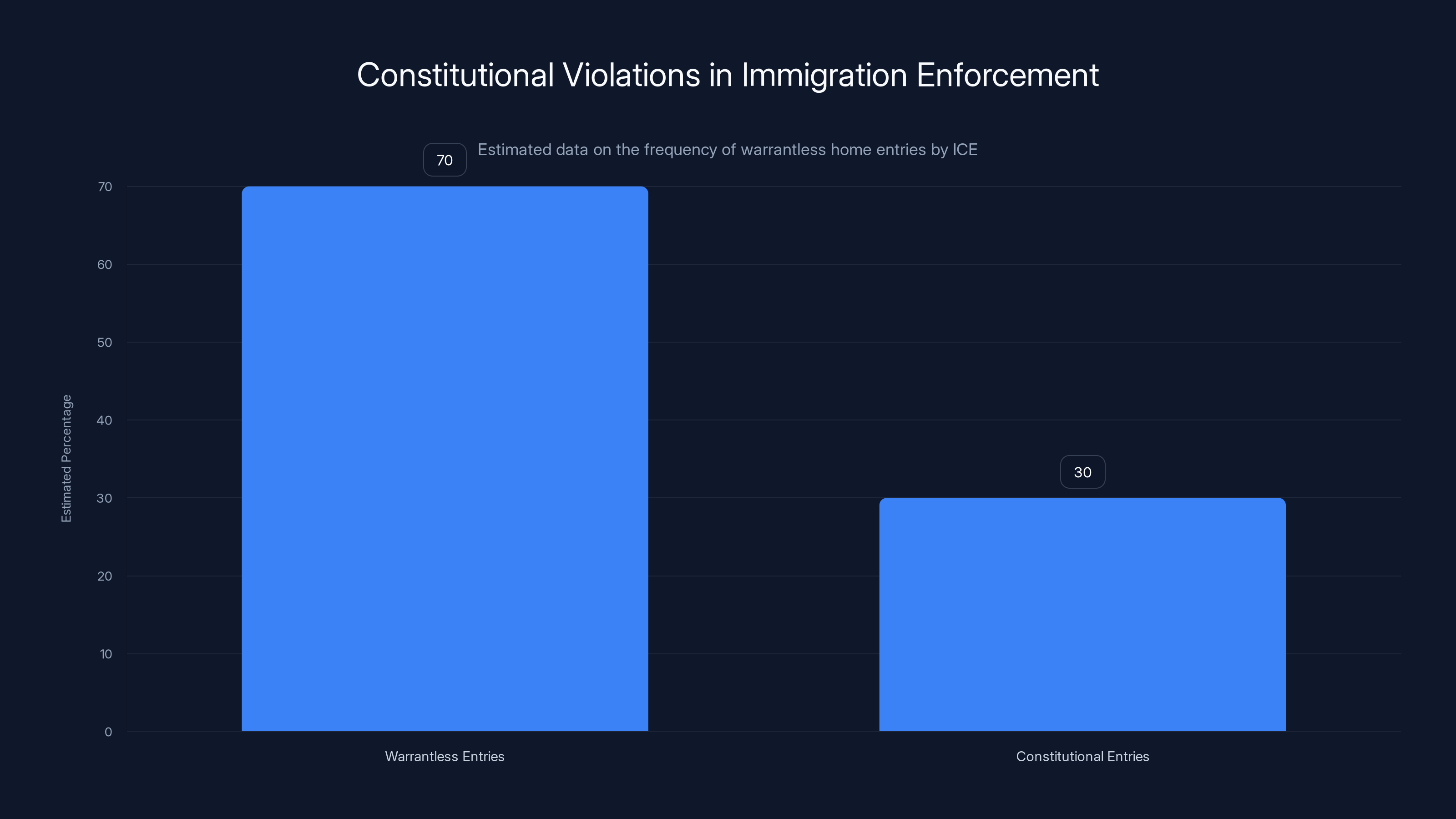

An estimated 70% of ICE home entries were conducted without judicial warrants, violating constitutional limits. Estimated data.

Garrison Gibson's Story: What Actually Happened That Morning

Garrison Gibson's experience is what makes this ruling real instead of abstract. He was living in Minnesota under what's called an ICE order of supervision. He'd been in the United States for years. He had a family. He had a life. He wasn't hiding. He was complying with the supervision order, checking in regularly with ICE.

On the morning of January 11, agents showed up at his home early, before most families are awake. Gibson was inside with his wife and children. He heard the knock and the announcement that it was ICE. He did what people are often told to do if law enforcement shows up: he didn't immediately open the door. He asked questions. Specifically, he asked to see a judicial warrant. That's a reasonable thing to ask. That's actually what the Constitution requires him to be shown, as reported by Sahan Journal.

The agents initially left. Gibson might have thought the situation was resolved. Maybe they'd realize they needed to get a proper warrant and come back with one. But they returned with more agents. And this time they didn't come to talk. According to Gibson's sworn declaration, they deployed pepper spray toward neighbors who had gathered outside. They brought a battering ram. They broke his door down.

During all of this, Gibson's wife was filming what was happening. She warned the agents that children were inside the home. Gibson says agents with rifles stood in their doorway after breaking through. When his wife demanded to see a warrant, agents kept saying "we're getting the papers." But they didn't show any judicial warrant. They just entered the home, moved through it "as if they were entering a war zone," according to Gibson's account, and arrested him.

Only after Gibson was handcuffed did the agents show his wife an administrative warrant. By that point, the forcible entry had already happened. The constitutional violation was already complete. No warrant shown during the entry process means the entry itself was unconstitutional, even if they had administrative authority to arrest him for immigration violations, as noted by SCOTUSblog.

This pattern matters because it suggests systematic practice rather than a one-off mistake. If this was just one agent acting outside policy, the violation might be anomalous. But the existence of the internal ICE memo suggesting this was authorized practice suggests Gibson's experience wasn't unusual.

How Judge Bryan's Ruling Applied Constitutional Law

Judge Bryan's decision relied on decades of Fourth Amendment case law. The ruling pointed out that the Supreme Court had established clear precedent about home entries. Law enforcement can't force their way into homes without a judicial warrant, even when executing civil (rather than criminal) detention authority. The distinction between civil and criminal doesn't change the constitutional protection that homes receive, as explained by Lawfare.

The judge wrote about what's called the "neutral and detached" requirement. Before agents can conduct a search or forcibly enter a home, a judicial officer needs to review the facts independently. That officer needs to be neutral, meaning they're not part of law enforcement and don't have a stake in the outcome. An ICE supervisor is not neutral. They work for ICE. They have an interest in supporting ICE operations. That's exactly why the Fourth Amendment requires an outside judge.

One prominent Fourth Amendment scholar, someone widely regarded as the nation's preeminent expert in this field, made the point directly: the executive branch can't be in charge of deciding whether to give itself a warrant. That's a logical absurdity that undermines the whole constitutional structure. If ICE supervisors can issue warrants to ICE agents, then there's no meaningful check on ICE power. The agency becomes judge of its own authority, as discussed in Lawfare.

The ruling also noted that the severity of the home entry—battering ram, pepper spray, multiple armed agents—made the constitutional violation more serious. Homes are supposed to be protected spaces. Forcibly breaking into someone's home is a serious intrusion on privacy and security. That intrusion can only happen if a judge has reviewed the facts and approved it. Anything less is unconstitutional.

Judge Bryan ordered Gibson's immediate release. That seemed like justice being served. But the story didn't end there.

While civil enforcement has a lighter burden of proof and lacks jury trials, it still requires judicial warrants and procedural safeguards similar to criminal enforcement. Estimated data.

The Twist: Gibson Gets Released, Then Re-arrested

One day after Judge Bryan ordered Gibson's release, something unexpected happened. Gibson showed up for a routine check-in at a Minnesota immigration office. He thought the court order had resolved his situation. That's reasonable. A federal judge had just ruled that ICE violated his constitutional rights and ordered his release. He was complying with his immigration supervision order by showing up for the check-in.

When he arrived, the officer handling his case looked at his file and apparently saw nothing problematic. "This looks good," the officer said. "I'll be right back." Gibson probably felt relieved. But then chaos erupted. Multiple officers came out. They announced they were taking him back into custody.

Gibson's attorney, who was present, was stunned. They'd just won a federal court ruling against ICE. The judge had ordered Gibson's release based on the Fourth Amendment violation. And now, twenty-four hours later, ICE was re-arresting him anyway, as reported by Sahan Journal.

What happened here is important for understanding how immigration enforcement actually works. Judge Bryan's ruling that ICE violated the Fourth Amendment during the home entry was a real ruling with real consequences for that specific event. It meant the home entry was unconstitutional. It meant that particular arrest violated the Constitution. And it meant Gibson had to be released.

But ICE's civil detention authority for immigration violations is separate from the question of whether a particular arrest violated the Fourth Amendment. Once someone's been arrested, even illegally, ICE can often continue holding them on immigration grounds. The fact that the arrest violated the Constitution doesn't automatically strip ICE of all detention authority. They're two different legal questions.

So ICE re-arrested Gibson on the same immigration violation they'd originally detained him for, but this time the arrest was processed differently. The constitutional violation didn't disappear—Judge Bryan's ruling still stands—but it didn't prevent ICE from continuing to detain Gibson. This highlights a real problem with immigration enforcement: constitutional violations don't necessarily result in release if the government can justify detention on other grounds.

Gibson's situation also included details worth noting. His criminal history, which ICE cited as a reason for removal, consisted of a single felony conviction from 2008. That conviction was later dismissed by courts. So the basis for the removal order was itself questionable. Yet ICE continued pursuing it anyway, even after a judge found they'd violated his constitutional rights in the process, as detailed by Cleveland.com.

The Broader Minnesota ICE Enforcement Surge

Gibson's case didn't happen in isolation. It was one incident in what Minnesota state officials were calling an "invasion" of federal immigration enforcement. ICE and other federal agents had apparently increased operations in Minneapolis and Saint Paul substantially. The intensity and scope of the enforcement surge drew attention from state officials and activists who characterized it as unconstitutional, as reported by AP News.

Minnesota's governor and other state leaders challenged the surge in federal court. They argued that ICE was conducting operations without proper legal authority and without proper coordination with state and local law enforcement. The state lawsuit, filed one day after Gibson's initial arrest, pointed to multiple incidents similar to Gibson's situation.

This context matters because it suggests Gibson's experience wasn't anomalous. If ICE was conducting numerous home entry operations using administrative warrants as justification, then Gibson's case was just one example of a systematic practice. Judge Bryan's ruling therefore had implications beyond one individual case. It addressed a pattern of conduct that apparently affected many people, as noted by Fox 9.

The increased enforcement activity also happened at a particular moment politically. Immigration enforcement priorities shift with changes in federal leadership. When administrations change, enforcement strategies change. Resources get reallocated. Agencies shift their focus toward different immigrant populations or different enforcement methods. Minnesota was experiencing what appeared to be a deliberate escalation of ICE operations.

State officials characterized this as problematic partly for legal reasons and partly for practical reasons. They argued it violated federal constitutional limits on search and seizure. But they also argued it strained relationships between local and federal law enforcement, created fear in immigrant communities, and diverted resources from state priorities. A federal surge in immigration enforcement isn't something state authorities can necessarily control or coordinate with, as highlighted by My North News.

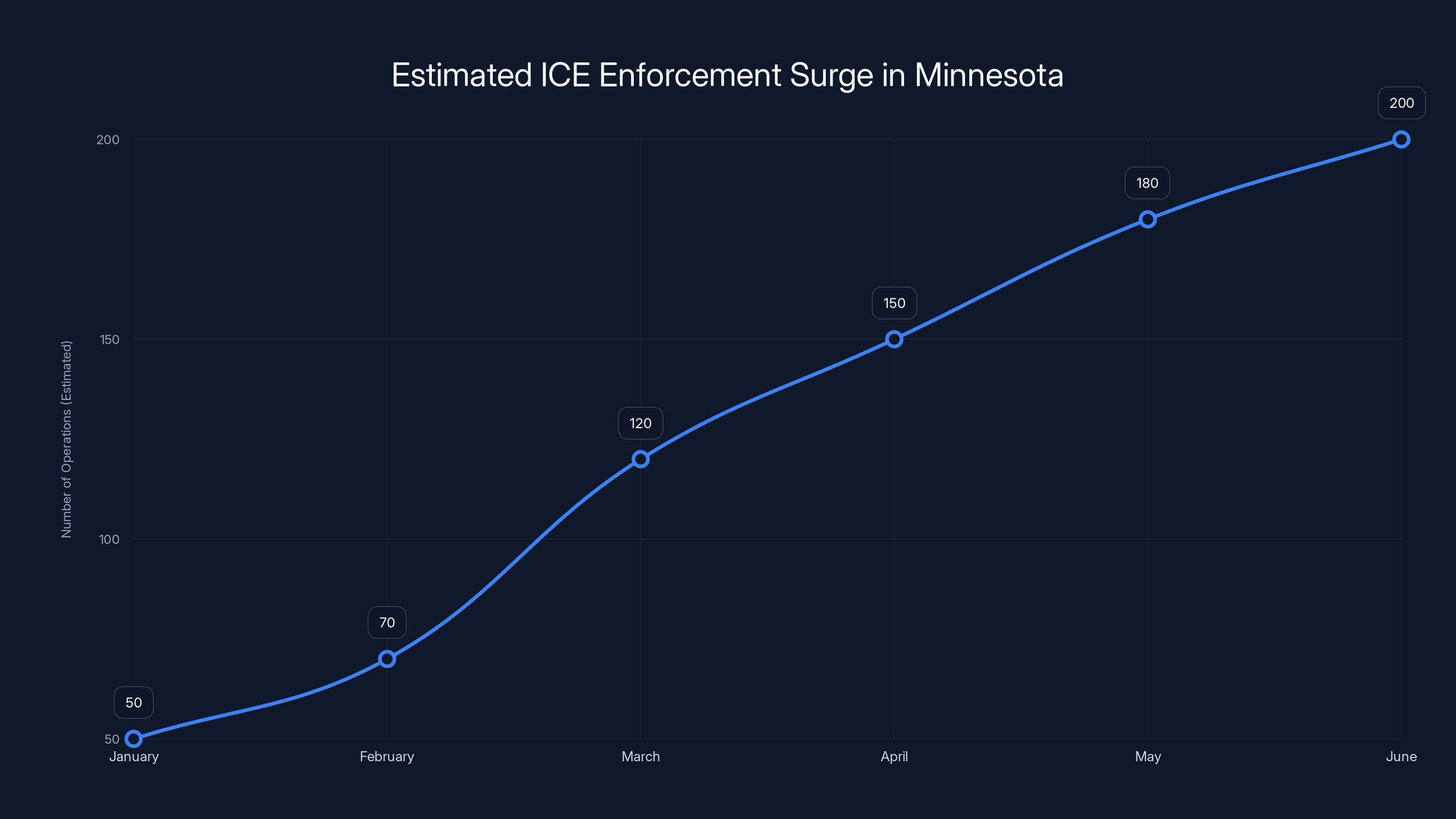

Estimated data suggests a significant increase in ICE operations in Minnesota from January to June, indicating a deliberate escalation in enforcement activities.

What Counts as a Valid Warrant Under Fourth Amendment Law

The distinction between administrative warrants and judicial warrants is central to understanding why Judge Bryan's ruling matters. Both types of documents can authorize arrests. But they have different scope, different requirements, and different constitutional implications.

Administrative warrants are civil documents. They're issued by an agency—in this case, ICE—and they authorize agents of that agency to arrest someone for violations of administrative law. In ICE's case, administrative warrants authorize arrests for immigration violations. These are violations of civil immigration law, not criminal law. Someone can be arrested on an immigration violation, detained, and eventually deported, even if they've committed no crime.

Administrative warrants don't require probable cause of criminal activity. They require administrative authority—basically, a determination that the person is deportable under immigration law. An immigration officer or supervisor can make that determination. That's why ICE supervisors can sign I-205 forms.

But administrative warrants have limits. They authorize arrests in public places. They authorize arrests in homes where someone has consented to agents being there. They do not authorize forcible entry into homes without consent. That limit exists specifically because the Fourth Amendment requires judicial authorization for forcible home entries, regardless of whether the entry is for criminal or civil purposes, as explained by Lawfare.

Judicial warrants are different. These are signed by judges—actual members of the judiciary, not agency officials. Judicial warrants require that an officer present facts to the judge, establish probable cause, and persuade the judge that the proposed search or seizure is reasonable. The judge reviews the facts independently. The judge can reject the application if the evidence is insufficient. This is supposed to be a meaningful check on law enforcement authority.

The Supreme Court has been clear that this distinction matters constitutionally. Civil enforcement doesn't get a free pass. The Fourth Amendment protects homes against civil searches and seizures just as much as criminal ones. If anything, the protection might be even stronger in civil cases because the government has different resources and fewer constraints when it's pursuing administrative violations rather than crimes, as discussed by WebProNews.

Judge Bryan's ruling essentially said: ICE agents can have administrative warrants all day long. Those warrants give them authority to arrest people for immigration violations. But they don't give them authority to break down doors and forcibly enter homes without consent. For that, they need judicial warrants signed by actual judges, as noted by SCOTUSblog.

This creates an operational problem for ICE. If agents want to arrest someone in their home without consent, they now need to go to court first. They need to present a judge with facts. The judge might decide the facts aren't sufficient. The process takes time. It slows down enforcement operations. But it's what the Constitution requires.

Constitutional Scholars and the "Neutral and Detached" Standard

Leading constitutional experts emphasized how Judge Bryan's ruling applied established doctrine. The requirement that judicial officers be "neutral and detached" comes directly from Supreme Court precedent. It means the judge reviewing the warrant application can't be biased toward the government or have an interest in the outcome.

This is why an ICE supervisor can't issue warrants for ICE operations. The supervisor works for ICE. They benefit when ICE operations succeed. They might face career consequences if they reject too many warrant applications. They're not neutral in any meaningful sense. An outside judge—someone appointed to the judiciary, operating under judicial ethics rules, with no connection to ICE—is neutral in the required way, as discussed by Lawfare.

The constitutional scholar analysis also emphasized something important about Fourth Amendment doctrine: you can't interpret your own authority. If you could, the Constitution would be meaningless. ICE can't just decide that it has the authority to enter homes and then rely on documents it issues to itself to justify the entries. That's not how legal authority works. Legal authority requires that someone outside the agency exercises judgment about whether the agency's proposed action is reasonable.

This principle extends beyond immigration enforcement. It applies whenever government agencies want to conduct searches or seizures. They might have administrative authority to take certain actions. But forcible home entry requires judicial approval. The court provides that approval by issuing a warrant based on probable cause.

What made ICE's internal memo so problematic was that it suggested agents could skip this step. It supposedly told them that administrative warrants were sufficient. But the Constitution doesn't care what internal memos say. The Constitution still applies. Agents can be trained incorrectly. They can receive bad guidance. But that doesn't change what the law requires, as highlighted by Military.com.

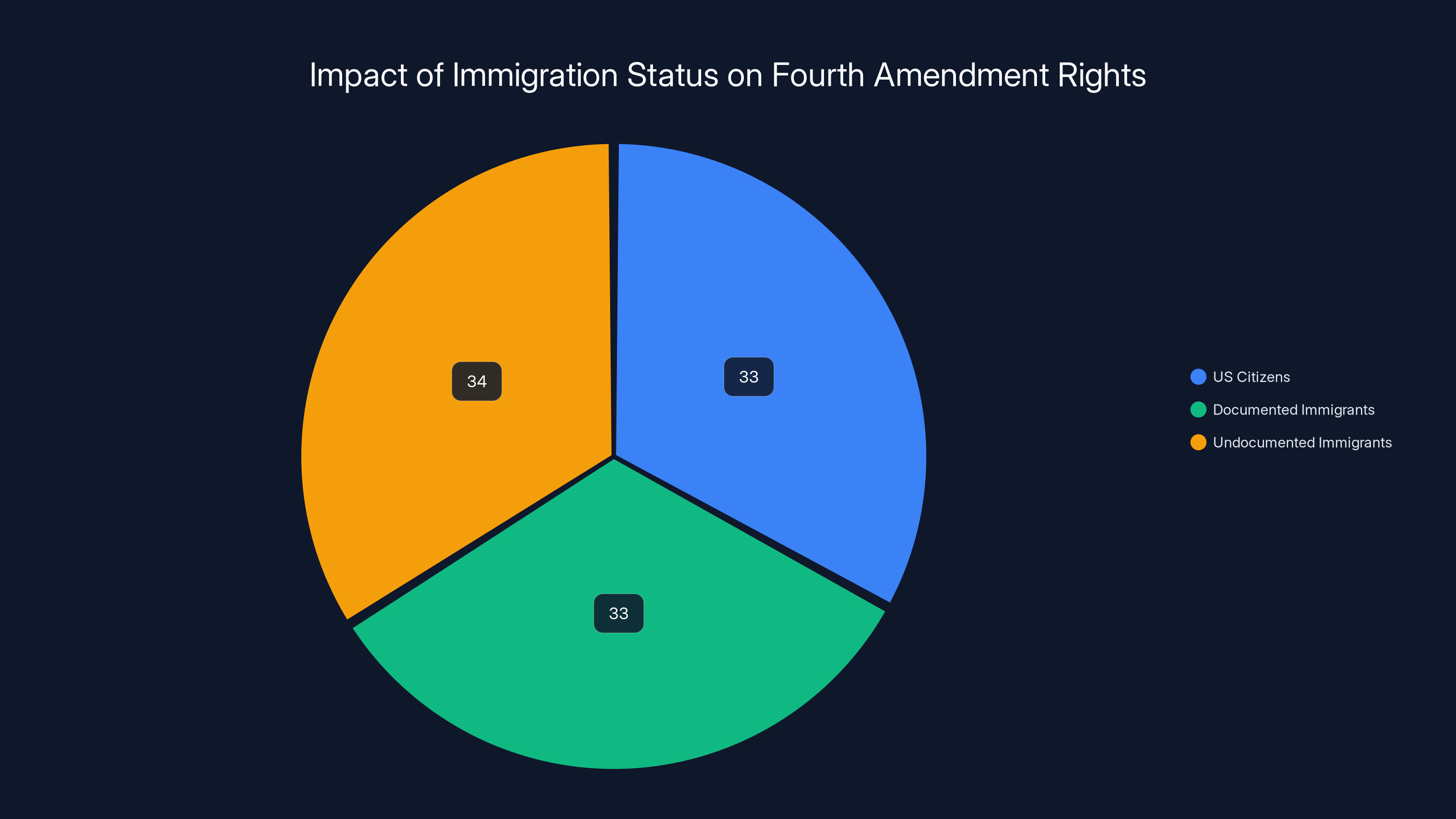

The Fourth Amendment protections apply equally to US citizens, documented immigrants, and undocumented immigrants, ensuring broad constitutional rights regardless of immigration status. (Estimated data)

Why This Ruling Matters Beyond One Case

Judge Bryan's decision has implications that extend well beyond Garrison Gibson's situation. It established binding precedent in the District of Minnesota and highly persuasive authority in other jurisdictions. When other judges in other cases confront questions about whether ICE can use administrative warrants to justify forcible home entry, they now have a federal court ruling saying the answer is no, as noted by The New York Times.

This matters for litigation strategy. Civil rights lawyers representing immigrants in other cases can cite Judge Bryan's decision. They can argue that their clients' cases are similar. They can demand that ICE produce judicial warrants, not administrative warrants, when challenging home entries. Immigration attorneys can advise clients about their rights more confidently.

It also matters for ICE's internal policies. The agency could ignore the ruling and continue the same practices. Agents could keep using administrative warrants to justify home entries. But doing so would violate established court precedent. Future lawsuits would cite Judge Bryan's decision. ICE would lose those cases. The agency would have to pay damages. At some point, ignoring a court ruling becomes expensive and counterproductive.

What will likely happen is some combination of response. ICE might revise its internal guidance to comply with the ruling. The agency might seek judicial warrants more consistently when agents plan to enter homes without consent. Or ICE might continue the practices and argue that the ruling was wrong, betting that appeals courts will reverse it. But the status quo—where ICE agents routinely enter homes based solely on administrative warrants—is now legally contestable, as discussed by WebProNews.

The ruling also raises questions about how many people have been arrested through home entries using administrative warrants. If the practice was systematic, then potentially dozens or hundreds of people were arrested through unconstitutional means. Some of those people might file their own lawsuits. Some might have claims against the government for damages under civil rights statutes. Some might challenge the legality of their deportations based on the unconstitutional arrests.

The Fourth Amendment and Civil Immigration Enforcement

One area where confusion sometimes exists is whether the Fourth Amendment applies as strongly to civil enforcement as it does to criminal enforcement. Immigration violations are civil matters. Someone can be deported even if they've committed no crime. This is technically a civil penalty, not a criminal one.

But the Supreme Court has been clear: civil doesn't mean less protection. If anything, civil enforcement deserves heightened protection because the government's police powers are less constrained. In criminal cases, the government needs to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Juries provide protection. There are extensive procedural safeguards. In civil cases, the government's burden is lighter. The government might face fewer constraints. That's why Fourth Amendment protection for searches and seizures doesn't distinguish between civil and criminal, as explained by SCOTUSblog.

Home entry by force is one of the most intrusive government actions possible. It happens in the place where people have the highest reasonable expectation of privacy. It happens when people are most vulnerable, often early in the morning while families are sleeping. The government's ability to conduct such intrusions is severely limited, regardless of whether the government is pursuing criminal charges or civil removal.

Judge Bryan's ruling applied this principle straightforwardly. The fact that ICE was pursuing civil immigration enforcement rather than criminal prosecution didn't change the Fourth Amendment analysis. Home entries still require judicial warrants. Administrative warrants still don't justify forcible entry. The constitutional limits still apply, as discussed by Lawfare.

This reasoning would likely extend to other civil law enforcement agencies as well. If the Department of Labor wanted to conduct home searches, they'd need judicial warrants. If the EPA wanted to inspect someone's home for environmental violations, they'd need judicial warrants. The Fourth Amendment protects homes against civil government intrusions just as much as criminal ones.

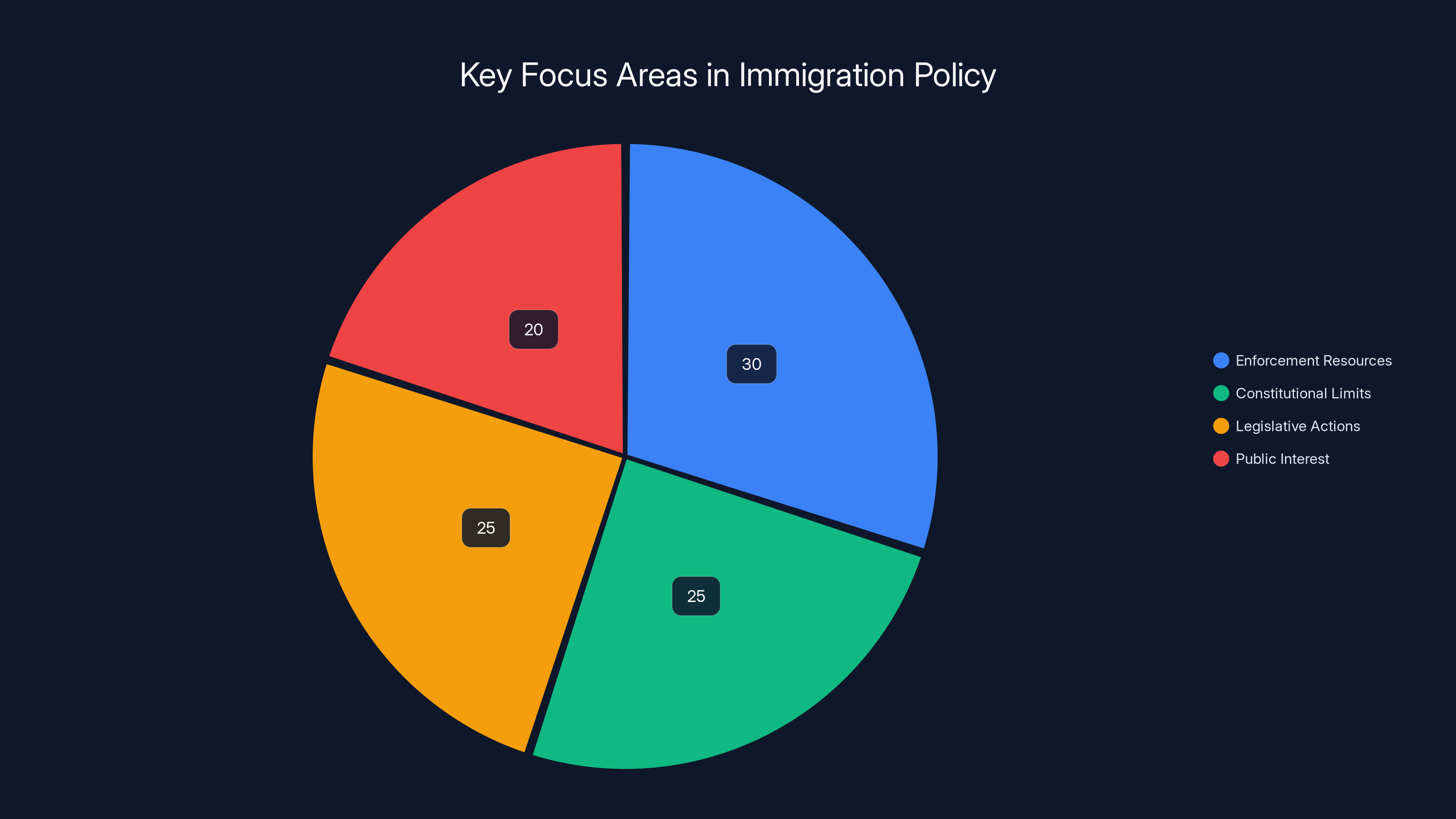

This chart estimates the distribution of key focus areas in U.S. immigration policy discussions, highlighting enforcement resources, constitutional limits, legislative actions, and public interest. Estimated data.

What Happens When Judicial Oversight Gets Skipped

When government agencies can conduct searches and seizures without judicial oversight, bad things tend to happen. History is full of examples. Agencies pursue enforcement actions based on incomplete information. They rely on tips that turn out to be false. They target the wrong people. They pursue cases that shouldn't be pursued. Without a judge reviewing the facts independently, mistakes compound, as noted by The New York Times.

In ICE's case, if agents can enter homes based solely on administrative warrants, then judges never get to review whether the facts actually support the case. A judge might look at the evidence and decide it's insufficient for probable cause. A judge might notice that the person identified in the warrant is actually someone else with the same name. A judge might see that the administrative violation cited doesn't actually apply. But without presenting the case to a judge, these errors never get caught.

The requirement for judicial approval isn't about being anti-law enforcement. It's about getting things right. Judges are trained in legal analysis. They hear from all sides. They apply legal standards consistently. They provide a check that improves the overall quality of law enforcement.

Gibson's case is illustrative. His criminal history cited by ICE as a reason for removal included a 2008 felony conviction that was later dismissed. A judge reviewing that case might have questioned the legal basis for removal immediately. But because judges weren't involved in the initial decisions to pursue the case, the dismissal apparently took years to process. Judicial review could have caught that problem earlier.

Forcing judges to review warrant applications doesn't prevent legitimate law enforcement. It just means that law enforcement has to present sufficient facts and meet constitutional standards. Agencies that have good facts and legitimate cases can still proceed. But agencies have to actually do the work of proving their cases rather than relying on administrative authority that they've issued to themselves, as discussed by WebProNews.

The Challenge of Remedying Constitutional Violations

One complexity with Judge Bryan's ruling is that remedying Fourth Amendment violations in immigration cases is difficult. In criminal cases, if police conduct an unconstitutional search, the evidence they find gets excluded from trial. The criminal case falls apart if the evidence is essential. This creates a powerful incentive for police to follow the rules.

But immigration cases work differently. There's no trial in the traditional sense. The government proves deportability in administrative proceedings. And even if a judge rules that an arrest was unconstitutional, immigration authorities retain detention authority on other grounds. They might not be able to use evidence from the unconstitutional search, but they can continue pursuing deportation based on administrative findings that don't depend on that evidence, as explained by SCOTUSblog.

This is what happened to Gibson. Judge Bryan ruled the home entry unconstitutional. But ICE re-arrested him anyway. The agency argued it had administrative authority to continue detaining him for immigration violations. Even though the arrest was unconstitutional, the detention continued.

This creates a situation where constitutional violations don't necessarily result in meaningful consequences. The person harmed by the violation might not gain much from the court's ruling. ICE might not face strong incentives to change practices if violations don't stop their enforcement operations.

One potential remedy would be damages lawsuits against the government under civil rights statutes. If Gibson sued ICE for violating his Fourth Amendment rights, he might recover damages. That would create a financial incentive for the agency to follow the rules. But such lawsuits require that someone file them, win them, and actually collect the damages. That's not easy.

Another potential remedy would be regulatory action. If the Department of Justice or the agency's inspector general determined that ICE was violating Fourth Amendment rights systematically, the agency could be forced to change policies. Funds could be withheld. Leaders could face consequences. But this requires political will and investigatory resources. It's not automatic, as discussed by WebProNews.

Judge Bryan's ruling provides a basis for future litigation. It establishes that the practice is unconstitutional. But actually changing ICE behavior requires more than one court ruling. It requires consistent judicial pressure, legislative attention, or executive initiative.

Warrants, Technology, and Modern Enforcement

One interesting aspect of the warrant question is how it applies to modern enforcement techniques. ICE has access to sophisticated surveillance technology. Agents can identify people's locations through cell phone tracking. They can conduct background checks instantly. They have facial recognition capabilities. They can access databases of immigration records.

With this technology, getting a judicial warrant before conducting a home entry should actually be easier than in the past. Agents can gather facts quickly. They can present a strong case to a judge. The process doesn't necessarily take long. A judge might be able to review a warrant application and approve it within hours, as noted by The New York Times.

So the argument that requiring judicial warrants would slow down enforcement operations might be overstated. Modern technology actually enables faster information gathering, which enables faster judicial review. If ICE wanted to pursue a case urgently, agents could present the facts to a judge immediately.

That said, there's probably something to the concern that judicial review takes more time than internal administrative authorization. If an agent wants to conduct a home entry, waiting for a judge to review the facts does add delay compared to just getting a supervisor's signature. From ICE's perspective, that delay is frustrating. From a constitutional perspective, that delay is exactly the point. The delay creates space for judicial review. It creates opportunity for mistakes to be caught. It ensures that authority is actually being exercised properly.

The tension between efficient enforcement and constitutional protection is real. But the Constitution wins that tension. Efficient enforcement that violates the Fourth Amendment isn't acceptable, regardless of how much more efficient it is, as explained by Lawfare.

Immigration Status and Constitutional Rights

Another important aspect of Judge Bryan's ruling is that it applies to everyone, regardless of immigration status. The Fourth Amendment protects people in the United States, not just citizens. The Supreme Court has been clear about this. Non-citizens have Fourth Amendment rights. Undocumented immigrants have Fourth Amendment rights. This isn't a controversial proposition in law, though it sometimes becomes politically contentious, as discussed by SCOTUSblog.

Garrison Gibson is a Liberian national. He's not a US citizen. But that doesn't change his Fourth Amendment rights. The Constitution still protects his home from unreasonable searches and seizures. ICE still needed a judicial warrant to forcibly enter his home. The fact that he's not a citizen is irrelevant to the constitutional question.

This principle is important because immigration enforcement disproportionately affects non-citizens. If non-citizens had fewer Fourth Amendment protections, the Fourth Amendment would mean less to the people most likely to encounter law enforcement engaged in immigration work. The Constitution would effectively operate as a right available only to citizens. But that's not how the law works. Constitutional protections apply broadly.

That said, there is a separate question about what happens after someone is lawfully arrested. Once someone's in custody, ICE has different authority than domestic law enforcement has. ICE can potentially detain someone for removal purposes based on immigration status alone, without needing to justify the detention the same way local police would need to justify detaining a citizen. The constitutional question is about how the person gets into custody in the first place. The detention authority question is separate.

Judge Bryan's ruling focused on the entry into custody—the home entry and arrest. It required that ICE follow Fourth Amendment procedures for that stage. Once Gibson was in custody (if that custody had been based on a valid warrant), the subsequent detention questions might be governed by different rules. But the entry into custody has to be constitutional, as explained by WebProNews.

The Broader Implications for Immigration Policy

Beyond the specific legal questions, Judge Bryan's ruling touches on broader questions about how immigration enforcement operates in the United States. Immigration policy involves balancing competing values: the government's interest in enforcing immigration law, the public's interest in the rule of law and constitutional limits on government power, and the interests of people whose lives are affected by immigration enforcement.

ICE's approach of using administrative warrants to justify home entries was efficiency-focused. It allowed faster enforcement without the burden of seeking judicial approval. But it skipped the constitutional check that's meant to ensure the government is acting properly, as noted by The New York Times.

There's a legitimate debate about how much resources should go to immigration enforcement, who should be prioritized for enforcement, and what tactics should be permitted. But there shouldn't be a debate about whether constitutional limits apply. Judge Bryan's ruling is right that the Fourth Amendment applies to immigration enforcement the same way it applies to everything else.

Moving forward, ICE can adapt to this requirement. Agents can seek judicial warrants for home entries. The process will take more time and require more justification. But the enforcement operations can continue within constitutional limits. The requirement isn't that ICE can't enforce immigration law. The requirement is that ICE does so constitutionally.

There's also a question about whether Congress should address this legislatively. Congress could clarify that ICE needs judicial warrants for home entries. Congress could provide resources to help agents obtain warrants quickly. Congress could address other immigration enforcement issues that might raise constitutional questions. But absent such legislative action, the courts will apply the Constitution as written. Judge Bryan's decision reflects that, as discussed by WebProNews.

Whistleblowing and Exposing Government Practice

Garrison Gibson's case existed because whistleblowers exposed ICE's internal practices. Without Whistleblower Aid bringing the internal memo to light, the public and courts might not have known about the agency's position on administrative warrants. Whistleblowing is often the only way the public learns what government agencies are actually doing, as highlighted by The New York Times.

Federal whistleblower protections are supposed to protect people who expose illegal or unconstitutional government conduct. But protection mechanisms are sometimes inadequate. Whistleblowers face retaliation risks. They face career consequences. They might struggle to find employment afterward. Some whistleblowers have faced serious legal jeopardy themselves, even when they were exposing genuine misconduct.

In this case, Whistleblower Aid's work created the legal case that Judge Bryan decided. Without whistleblowers willing to document and expose the ICE memo, the constitutional issue might have gone unaddressed. The agency's practice might have continued without judicial review. Countless people might have faced warrantless home entries without constitutional remedy.

This highlights the importance of robust whistleblower protection. When government agencies can operate in secret, constitutional violations can continue indefinitely. Whistleblowers provide a check on that secrecy. They help ensure that government operates within constitutional and legal limits.

There's also a broader principle here about transparency and accountability. Government enforcement agencies shouldn't operate on the basis of secret memos that contradict constitutional law. Policies affecting thousands of people shouldn't be circulated internally without public scrutiny. Whistleblower protection makes such transparency possible. Judge Bryan's ruling depends on that whistleblowing, as discussed by WebProNews.

Future Litigation and Precedent

Judge Bryan's ruling is binding in the District of Minnesota and persuasive in other federal districts. That means other judges should follow the same reasoning. Other cases involving warrantless home entries by ICE will likely cite this decision. Civil rights attorneys will use it to argue that ICE violated their clients' Fourth Amendment rights, as noted by The New York Times.

The question is whether the ruling will survive appeal. ICE could challenge Judge Bryan's decision in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. The government might argue that administrative warrants are sufficient for immigration enforcement. The government might argue that the Fourth Amendment doesn't apply as strictly in immigration cases. The appeals court would review whether Judge Bryan's legal reasoning was correct.

If the appeals court upholds the ruling, it becomes binding precedent in a broader region covering multiple states. If the appeals court reverses, Judge Bryan's reasoning loses authority. If the case reaches the Supreme Court, the nation's highest court would decide the issue definitively.

Historically, the Supreme Court has protected Fourth Amendment rights fairly strongly. The court has been skeptical of government arguments that law enforcement efficiency justifies skipping constitutional procedures. But immigration cases sometimes get different treatment. Courts have sometimes been deferential to immigration enforcement choices that they might not accept in other contexts.

So the question of whether Judge Bryan's ruling will survive appeal and what its ultimate scope will be remains open. But the legal basis for the ruling is sound. The Fourth Amendment does apply. Judicial warrants are required for home entries. Administrative warrants don't provide sufficient justification. That reasoning is solid even if future courts might reach different conclusions about application or scope, as discussed by WebProNews.

International Perspectives on Warrant Requirements

Interestingly, other countries' approaches to warrant requirements provide context for thinking about the US legal framework. Most democracies worldwide require judicial approval before police can conduct searches or seizures in homes. This isn't uniquely American. It's a standard feature of rule of law in countries that take constitutional limits on government power seriously, as noted by Lawfare.

Canada requires judicial warrants for home entry. Britain requires them. Germany requires them. Australia requires them. The European Court of Human Rights has found violations when governments conducted home searches without proper judicial authorization. Warrant requirements are part of how democratic societies limit government power.

The US Fourth Amendment is older than most modern constitutions. But its basic principle—that government needs independent judicial approval before conducting home searches and seizures—reflects something broader about rule of law and limiting executive power.

From an international perspective, ICE's internal position that administrative warrants justified home entry would be surprising. It suggests the executive branch can authorize its own searches and seizures without judicial check. Most democracies wouldn't permit that.

This doesn't mean the US is uniquely bad at respecting Fourth Amendment rights. But it suggests that Judge Bryan's ruling isn't enforcing some idiosyncratic American requirement. It's enforcing a principle that democratic societies widely share. Executive branches shouldn't be able to authorize their own searches in people's homes. That's a basic principle of limited government, as discussed by WebProNews.

FAQ

What is a judicial warrant and why does it differ from an administrative warrant?

A judicial warrant is a document signed by a judge authorizing a specific search, seizure, or arrest based on probable cause that the judge has independently reviewed. An administrative warrant is a document signed by an agency official (in ICE's case, a supervisor) authorizing an arrest for administrative violations without requiring independent judicial review. Judicial warrants provide constitutional protection through independent review, while administrative warrants are internal agency documents that don't satisfy Fourth Amendment requirements for home entry, as explained by WebProNews.

How did Judge Bryan's ruling affect Garrison Gibson's case?

Judge Bryan ruled that ICE violated Gibson's Fourth Amendment rights by forcibly entering his home without a judicial warrant, using only an administrative warrant. The judge ordered Gibson's immediate release. However, ICE re-arrested Gibson twenty-four hours later on immigration grounds, demonstrating that a finding of constitutional violation doesn't automatically prevent continued detention if the agency asserts other legal authority. Gibson's case established precedent but didn't result in his ultimate release from immigration custody, as reported by Sahan Journal.

Why did ICE apparently believe administrative warrants justified home entry?

ICE issued internal guidance (a memo) suggesting that administrative warrants for removal and deportation provided sufficient legal authority to enter homes without consent. The agency apparently interpreted civil immigration enforcement as not requiring the same Fourth Amendment protections as criminal enforcement. This position contradicted established constitutional law, which applies Fourth Amendment protections to civil government intrusions on homes, as revealed by The New York Times.

What is the Fourth Amendment and how does it protect homes?

The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures and requires that warrants be issued by judges based on probable cause. The Supreme Court has established that law enforcement cannot forcibly enter homes without judicial warrants, whether the government is pursuing criminal or civil enforcement. This protection applies to all people in the United States, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, as discussed by SCOTUSblog.

How does the warrant process work in practice for law enforcement?

When law enforcement agents want to conduct a search or seizure, they typically must present facts to a judge in writing, demonstrating probable cause that evidence of illegal activity will be found at a location or that a person should be arrested. The judge reviews the facts independently and decides whether to issue the warrant. The judge is supposed to be neutral and detached from the law enforcement agency making the request. This creates a constitutional check on law enforcement authority, as explained by Lawfare.

What happens if law enforcement conducts a search or seizure without a proper warrant?

If law enforcement conducts a home entry or search without proper judicial authorization, the entry is unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment. Evidence obtained from an unconstitutional search is typically excluded from criminal trials. In civil cases like immigration proceedings, the consequences are different—the violation is still real, but the remedy might be a damages lawsuit or exclusion of evidence rather than dismissal of the case, as noted by WebProNews.

Why was the secret ICE memo considered problematic by whistleblowers?

The memo apparently instructed ICE officers that administrative warrants issued by ICE supervisors were sufficient to justify forcible home entry without judicial approval. Whistleblowers considered this unconstitutional because it skipped the judicial check required by the Fourth Amendment. The memo suggested the executive branch could authorize its own searches without independent judicial review, which violates the constitutional principle of limited government, as revealed by The New York Times.

Can immigration cases be treated differently than criminal cases under the Fourth Amendment?

No. The Supreme Court has established that the Fourth Amendment applies equally to civil and criminal law enforcement. Immigration violations are civil matters, but that doesn't diminish Fourth Amendment protection. Homes receive the same constitutional protection whether law enforcement is pursuing criminal charges or civil immigration violations. Both require judicial warrants for forcible entry, as discussed by SCOTUSblog.

What role did whistleblowers play in exposing the ICE practice?

Whistleblower Aid, a nonprofit legal organization, worked with federal whistleblowers to expose ICE's internal guidance suggesting administrative warrants justified home entry. Without whistleblowers willing to document and disclose the memo, the public and courts would likely not have learned about the agency's position. Whistleblowing made judicial review of the practice possible, as highlighted by The New York Times.

What happens next in immigration enforcement after this ruling?

ICE can comply with the ruling by seeking judicial warrants for planned home entries, which would slow enforcement but ensure constitutional compliance. Alternatively, ICE could appeal Judge Bryan's decision to challenge the ruling's scope. Other cases involving similar issues will likely cite the decision. The ultimate precedent might depend on whether appeals courts and potentially the Supreme Court accept Judge Bryan's reasoning, as discussed by WebProNews.

Conclusion: Constitutional Limits on Immigration Enforcement

Judge Bryan's ruling in the Minnesota case represents something straightforward but important: the Fourth Amendment applies to immigration enforcement. When ICE agents want to enter someone's home by force, they need judicial approval based on probable cause, not just administrative authority, as noted by The New York Times.

This shouldn't be controversial. The Constitution is clear. Decades of case law support this principle. Other democracies operate this way. But the existence of ICE's internal memo suggested the agency had adopted a different view. Leadership apparently believed administrative warrants justified home entry. That position contradicted constitutional law.

The practical implications ripple outward. Agents across the country who received guidance that administrative warrants justified home entry were operating under instructions that violated the Constitution. People arrested during warrantless home entries have grounds to challenge those arrests. Future litigation will likely cite Judge Bryan's ruling. ICE's enforcement operations will face constitutional constraints they apparently weren't recognizing before.

What's remarkable is how close this came to never being addressed. Without whistleblowers exposing the memo, judges might not have reviewed the practice at all. Immigration enforcement might have continued with warrantless home entries indefinitely. Transparency and whistleblower protection made judicial review possible, as highlighted by WebProNews.

Garrison Gibson's case is real. His home was forcibly entered. His family experienced law enforcement agents breaking through their door. A judge found that unconstitutional. That finding matters, even if it didn't result in his ultimate release from immigration custody. It establishes that the practice violated the Constitution. It creates precedent for future cases. It provides legal ground for challenging similar conduct.

Moving forward, immigration enforcement can continue. But it has to do so within constitutional limits. Agents can seek judicial warrants. Judges can review whether agents have facts supporting probable cause. The process takes more time than internal administrative authorization. But that's exactly how the Constitution is supposed to work. Government power is limited by the requirement that judges independently review and approve it.

The broader principle Judge Bryan's ruling enforces is that constitutional limits apply equally to immigration enforcement and all other government action. There's no exception for civil enforcement. There's no exception for national security concerns. There's no exception for administrative matters. The Fourth Amendment protects homes against unreasonable government intrusions, period. Law enforcement gets to pursue legitimate enforcement objectives within constitutional boundaries. That's how limited government works.

Federal judges will continue applying this principle in other cases. Civil rights attorneys will use it to challenge warrantless home entries. Immigration authorities will face questions about their legal authority. Some of that will be frustrating for law enforcement agencies. But frustration with constitutional limits isn't grounds for ignoring them. The Constitution constrains government power intentionally. Those constraints are what prevent government from becoming too powerful. Judge Bryan's ruling simply enforces what the Constitution already requires, as discussed by WebProNews.

Key Takeaways

- Federal Judge Bryan ruled ICE violated the Fourth Amendment by using administrative warrants instead of judicial warrants to enter Garrison Gibson's home without consent, establishing binding precedent, as reported by AP News.

- ICE's internal memo incorrectly claimed administrative warrants (Form I-205) signed by supervisors were sufficient to justify forcible home entry, contradicting established constitutional law, as revealed by The New York Times.

- Whistleblower Aid exposed the secret ICE guidance, making judicial review possible and demonstrating how whistleblower protections enable government accountability, as highlighted by The New York Times.

- Administrative warrants authorize arrests in public but cannot justify nonconsensual home entry, which requires independent judicial approval based on probable cause, as discussed by Lawfare.

- Even though Judge Bryan found ICE violated Gibson's constitutional rights, ICE re-arrested him 24 hours later on immigration grounds, highlighting how constitutional violations don't automatically prevent continued detention, as reported by Sahan Journal.

Related Articles

- ICE Agents Doxing Themselves on LinkedIn: Privacy Crisis [2025]

- ICE Agents and Qualified Immunity: Why Accountability Remains Elusive [2025]

- ICE's $50M Minnesota Detention Network Expands Across 5 States [2025]

- How Communities Respond to Immigration Enforcement Crises [2025]

- Minneapolis ICE Shooting & Protests: Federal Response [2025]

- How DHS Keeps Failing to Unmask Anonymous ICE Critics Online [2025]

![ICE Judicial Warrants: Federal Judge Rules Home Raids Need Court Approval [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ice-judicial-warrants-federal-judge-rules-home-raids-need-co/image-1-1769208135026.jpg)