India's Supreme Court Takes On WhatsApp: What You Need to Know About Privacy Rights and Data Exploitation

There's a moment in every regulatory showdown where someone finally says what everybody's been thinking. On a Tuesday in early February, that moment arrived in New Delhi.

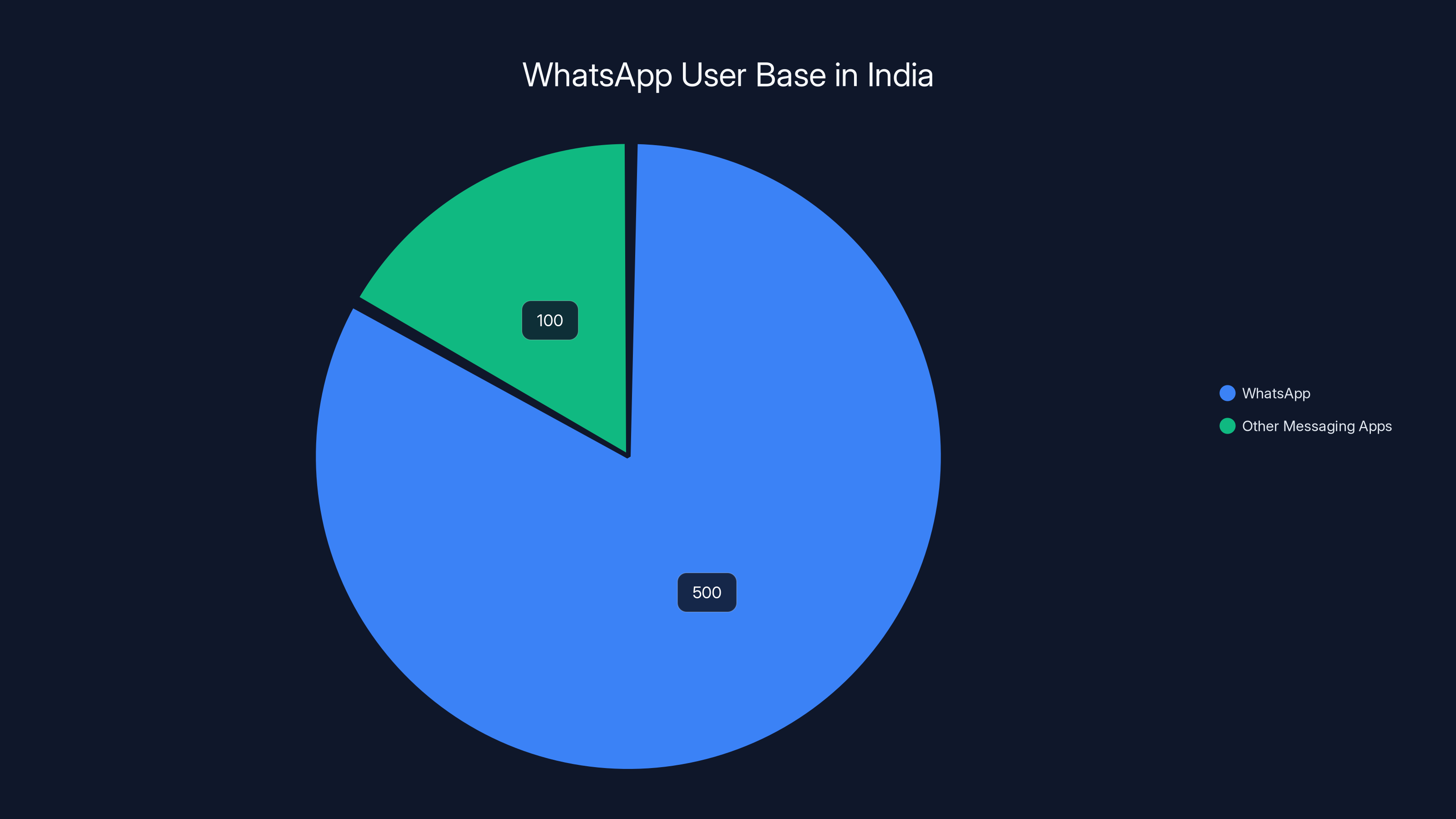

India's Supreme Court wasn't polite about it. Judges looked directly at Meta's legal team and essentially said: "You cannot play with the right to privacy." No hedging. No corporate diplomatic language. Just raw frustration that a platform serving over 500 million Indians was treating personal data like it belonged to no one.

This wasn't some lower court's symbolic gesture or a tech journalist's hot take. This was India's highest judicial authority, delivered in a courtroom where massive tech platforms suddenly realize they're not in Silicon Valley anymore. They're in a country where the Supreme Court has previously recognized privacy as a fundamental constitutional right. And that right isn't negotiable.

WhatsApp faces unprecedented pressure on multiple fronts. The company claims its end-to-end encryption means messages are private. That's technically true. But the court's real concern? Metadata. The information about who you're talking to, when you're talking to them, how often you communicate, patterns in your behavior. That stuff isn't encrypted, and it's worth money.

Justice Ujjal Bhat articulated the elephant in every courtroom: "A poor woman selling fruits on the street or a domestic worker cannot be expected to understand how their data is being used." This gets to the heart of why consent in tech is broken. You agree to terms of service by tapping a button on your phone. You're not really consenting to anything. You're just trying to use the app.

The case represents something bigger than WhatsApp's problems in India. It's about whether tech platforms can continue operating in a world where data is treated as an infinite resource, free for exploitation. India's moving to answer that question with a resounding no.

The Size of the Problem: 500 Million Indians and Growing

Numbers alone don't capture why this matters, but let's start there. WhatsApp has over 500 million users in India. That's roughly one-third of India's entire population. For Meta, India isn't just a market—it's the market. The company can't afford to lose India. The growth trajectory has been consistently upward, and ad monetization remains one of Meta's core business goals across all platforms.

India isn't a small regulatory problem anymore. It's a systemic issue. When India's courts act, other countries watch. Brazil watched when India banned TikTok. Australia watched when India questioned YouTube's practices. Regulatory momentum builds.

The penetration of WhatsApp in India goes beyond social media metrics. Small business owners use it. Your taxi driver uses it. Grandmother groups coordinate family logistics through it. It's not a platform choice—it's become infrastructure. That's exactly why courts are stepping in. When something becomes infrastructure, it can't operate on normal platform rules.

Meta knew this. That's why the company spent years building WhatsApp's presence in India while simultaneously planning how to eventually monetize the massive user base. The company introduced WhatsApp Status. It tested WhatsApp Shop. It integrated WhatsApp with Instagram. Each addition was a stepping stone toward extracting value from a platform that users originally joined for private messaging.

The monetization strategy was always transparent if you paid attention. A platform that started as a paid service, became free, and then serves 500 million users in the world's largest emerging market? Somebody has to pay eventually. Meta decided that somebody would be the users themselves through their data.

What Is Metadata and Why Should You Care?

Here's where most explanations lose people. Metadata sounds technical and boring. So let's make it concrete.

When you send a WhatsApp message, the actual words are encrypted. Meta can't read them. That's legitimate privacy protection. But the metadata? That tells a different story entirely. Meta knows:

- Who you contacted and when

- How often you talk to specific people

- Time zone patterns that reveal your location

- Whether you're using WhatsApp at 3 AM (stress? insomnia? affair?)

- Group membership and your role in those groups

- Business connections vs personal ones

- Holiday patterns and work schedules

None of this requires reading your messages. It's all revealed by behavior. And behavior is incredibly valuable. Justice Joymalya Bagchi specifically raised this point in court: "The commercial value of behavioral data and how it was used for targeted advertising." Even anonymized or supposedly siloed information carries economic worth.

Consider a practical example. Meta knows you're in a WhatsApp group for coffee enthusiasts, you message at 8 AM on weekdays, and you rarely message on weekends. That's worth money to a coffee equipment company. Meta knows you're in a business WhatsApp group, the frequency of your messages, and when you're busiest. That's worth money to hiring platforms and office supply companies.

The real problem isn't that Meta collects this data. It's that users never really agreed to what happens with it, and the value extraction is completely invisible. You tap "I agree" to use WhatsApp. You're not agreeing to have your communication patterns sold to advertisers. But you are.

The Monopoly Problem That Nobody Elected

Justice Sanjay Kant made a striking observation in court: WhatsApp operates as a monopoly in practice. Not in the strict legal definition, but in practical reality. When everyone you know, every business you deal with, and every community organization in your area uses WhatsApp, you don't have meaningful alternatives.

Signal exists. Telegram exists. But they're not where your contacts are. Your mom isn't on Signal. Your doctor's office probably isn't on Signal. Your kids' school almost certainly isn't on Signal. They're all on WhatsApp because WhatsApp has 500 million users in India and Signal has... well, a fraction of that.

This is the network effect problem in its purest form. Once a platform reaches critical mass, competition becomes theoretical. Users switch to Signal for privacy reasons, but they quickly switch back because Signal doesn't have their network on it. WhatsApp becomes not just a choice but a requirement.

Meta exploits this relentlessly. The company knows that WhatsApp users are locked in by network effects. Where else can they go? So WhatsApp can gradually change what data it collects, how it shares data, and what it plans to do with that data. Users feel the change, they're unhappy about it, but they don't actually leave. Because leaving means abandoning their entire social and professional network.

The court is essentially saying: that's not acceptable. Monopoly power plus data exploitation plus unclear consent equals a violation of fundamental rights. Justice Bagchi pressed Meta on exactly this point: How can users consent to something when they have no real alternative?

The Monetization Machine: How WhatsApp Plans to Make Money

Meta didn't acquire WhatsApp for $19 billion in 2014 because they wanted to provide a free messaging service indefinitely. That's not how tech companies work. The acquisition was always about data assets and monetization pathways.

For years, WhatsApp remained separate from Meta's advertising business. That was partly strategic—keeping users comfortable—and partly logistical. But the integration was always the plan. The company started slowly. WhatsApp Business emerged as a separate service for companies to message customers. Then came WhatsApp Pay, the payment platform. Then came Status, essentially WhatsApp's version of stories with advertising potential.

Each addition moved WhatsApp closer to becoming an advertising platform rather than a messaging platform. The court is concerned about this trajectory. Judges specifically questioned "the potential commercial value of metadata generated by the platform, and how such data could be monetized across Meta's wider advertising and AI functions."

Let's break down what this means. Meta already has advertising infrastructure. The company has massive AI systems trained on billions of data points. If Meta integrates WhatsApp metadata into these systems, suddenly Meta knows:

- What you're interested in based on WhatsApp group participation

- Your income level and spending patterns based on business messages

- Your daily schedule based on communication timing

- Your location patterns based on timezone and activity

- Your relationships and social connections based on group membership

- Your interests and behaviors based on when you use the app

Then Meta serves you ads on Instagram, Facebook, and other platforms with unprecedented precision. You never agreed to this. You agreed to send encrypted messages. The data harvesting is the hidden cost of free service.

Indian government lawyers made this explicit in court: "Personal data was not only collected but also commercially exploited." That's the accusation. Not just collection. Exploitation.

WhatsApp's End-to-End Encryption: Good Privacy Theater, Incomplete Story

WhatsApp's marketing heavily emphasizes end-to-end encryption. Every message you send is encrypted. Nobody at WhatsApp can read your messages. That's genuinely true and genuinely important.

But that's also not the whole story, and the Supreme Court judges clearly understand this. End-to-end encryption protects message content. It doesn't protect metadata. It doesn't protect behavior patterns. It doesn't protect information about who you're communicating with.

Think of it like this. Your house has a great lock on the front door (encryption). But the mailman can still see every letter you receive (metadata). The lock doesn't stop someone from knowing you're subscribing to medical journals, expensive wine clubs, or investment newsletters. The lock protects the content but not the pattern.

Meta has built an entire brand around encryption. It's prominent in marketing materials. It appears in every privacy policy. It makes users feel protected. And in a narrow sense, they are protected. But the broader privacy picture is far darker.

Authorities in multiple countries have examined this exactly. U.S. regulators reportedly investigated claims about WhatsApp privacy, questioning whether chats are truly as private as Meta claims. The investigation wasn't about message content—it was about metadata, data sharing with other Meta platforms, and what information is actually exposed.

India's Supreme Court appears to grasp this distinction clearly. Judges didn't argue against WhatsApp's encryption. They argued against the platform's data collection and monetization practices that exist completely separately from message content.

The Consent Problem: Terms of Service That Nobody Reads

Here's a fundamental problem with how tech regulation currently works: consent is broken.

When you download WhatsApp, you see a screen with a terms of service link. Most users tap "agree" without reading anything. They just want to use the app. This isn't a failure of individual users—it's a failure of corporate responsibility. Companies deliberately make terms of service long, dense, and legalistic specifically so most people won't read them.

Justice Ujjal Bhat made this observation explicit: "A poor woman selling fruits on the street or a domestic worker cannot be expected to grasp how their data was being used." This is a reality check on consent mythology. You can't consent to something you don't understand. If terms of service are deliberately incomprehensible, and if users are forced to accept them to use a platform they depend on, then consent isn't real.

Meta's argument is likely that users agreed to the terms of service. Users can read the privacy policy anytime. Users can change settings to limit data sharing. Technically true. Practically meaningless.

Consider the math. WhatsApp's privacy policy is approximately 8,000 words. The average person reads about 200 words per minute. That's 40 minutes to read the policy. Add another 20 minutes to actually understand it if you have a tech background. That's an hour for a service you're using because your dentist's office schedules appointments through WhatsApp.

Worse, the policy is written by lawyers specifically to be defensible in court, not to be understood by users. Phrases like "we may share information with service providers" is vague by design. It could mean anything from basic infrastructure partners to advertising networks to AI training datasets.

India's Supreme Court is essentially saying: this broken consent system doesn't satisfy constitutional requirements for protecting fundamental privacy rights. Even if users technically agreed to something, that agreement isn't informed if the terms are incomprehensible. And it's not voluntary if refusing means losing access to an essential service.

Regulatory Pressure: India, U.S., and Global Scrutiny

WhatsApp isn't just facing India's Supreme Court. The platform is under investigation in multiple countries simultaneously, and the regulatory environment is hardening everywhere.

In the United States, authorities reportedly examined whether WhatsApp privacy claims are accurate. The focus wasn't on whether encryption works—it was on what data Meta collects beyond encrypted messages and what the company does with that data. U.S. regulators have shown increasing interest in metadata practices specifically.

Brazil has been aggressive with tech regulation. The country banned TikTok partially in response to data privacy concerns. When Brazil watches India take action against WhatsApp, it signals international coordination on data rights.

Europe implemented GDPR years ago. The regulatory framework is already strict. WhatsApp's practices in Europe are more constrained than in India simply because the legal framework is stronger. But India is moving to create similar constraints.

The pattern is clear. Country after country is determining that data practices Western tech companies consider normal are actually violations of fundamental rights. The Supreme Court in New Delhi is part of a larger global movement where privacy is being recognized as something that can't be sacrificed for convenience or corporate profit.

India's case is particularly significant because India represents the future of tech's user base. The country has 1.4 billion people, massive internet growth, and a judiciary willing to take aggressive action against corporate overreach. If Meta loses in India, the company loses access to a third of the world's potential users and faces a regulatory precedent that spreads globally.

The Government's Role: Adding Regulatory Firepower

The Supreme Court case became significantly more complex when India's IT ministry joined as a party to the proceedings. This wasn't just about judicial scrutiny anymore. It became about government policy and regulatory authority.

When a government ministry enters a case as a party, it fundamentally changes the dynamics. The court is no longer just deciding between a company and individuals. The court is now considering government interests in regulating technology in service of public welfare.

India's IT ministry brings enforcement capacity that courts alone can't provide. The ministry can propose regulations, set compliance requirements, and enforce penalties. The ministry can also coordinate with other government agencies. If the IT ministry wants WhatsApp to implement specific data protection measures, the company can't simply ignore the ruling.

This is why Meta was likely paying careful attention to the suggestion that the IT ministry should participate. The company understood that judicial criticism is one thing. Judicial criticism plus government regulatory authority is another entirely.

Government lawyers explicitly stated that "personal data was not only collected but also commercially exploited." This language matters. It's not saying Meta collects data improperly. It's saying that even if collection is legal, exploitation of that data violates users' rights. This distinction is important because it suggests a future regulatory framework where data collection might be allowed but data monetization could be restricted.

The Regulatory Constraints: SIM-Binding Rules and Business Messaging

WhatsApp is already navigating new regulatory constraints in India beyond the Supreme Court case. The government implemented SIM-binding rules aimed at curbing fraud and reducing misuse of the platform by bad actors.

These rules require small businesses and entities to verify their WhatsApp accounts with SIM information. The intent is good—prevent fraudulent impersonation and scamming. The impact is significant for WhatsApp's business model.

Small businesses in India depend heavily on WhatsApp for customer communication. When you add friction to the verification process, you reduce business participation. WhatsApp wants small businesses on the platform because it drives engagement, usage statistics, and eventually advertising revenue. Regulatory requirements that reduce business participation harm these goals.

The SIM-binding rules are relatively minor compared to potential outcomes from the Supreme Court case, but they signal the direction of regulation. India is willing to implement requirements that reduce platform convenience if those requirements serve public interests.

For WhatsApp, this creates a problem. The platform can't refuse to comply with Indian regulations—the government is too large a market. But compliance reduces business usage. Reduced business usage reduces monetization opportunities. Eventually, if enough regulations pile up, WhatsApp's business model in India becomes less profitable.

What's Actually at Stake: Fundamental Rights vs. Corporate Convenience

This case isn't really about WhatsApp specifically. It's about whether tech platforms can treat user data as a resource to exploit for corporate profit or whether data reflects fundamental rights that platforms must respect.

Meta's core argument is that users consented to data practices. Users agreed to terms of service. Users can change privacy settings. Users can delete the app. Therefore, the company hasn't violated rights—it's operating within a framework users accepted.

India's Supreme Court is effectively rejecting this entire framework. The court is saying: consent doesn't count when a platform is essential infrastructure and users have no real alternatives. Even if users technically agreed to something, that doesn't justify exploitation if the consent wasn't informed. And privacy rights exist regardless of consent—they're fundamental, not negotiable.

This is fundamentally different from how tech regulation usually works in Western democracies. In the United States, regulation tends to focus on narrow questions: Did the company follow its own stated policies? Did the company violate specific laws? Did the company collect more data than it claimed?

India's approach is broader: Does the company's behavior respect fundamental constitutional rights to privacy? The answer to that question goes beyond narrow policy violations or technical compliance. It asks whether entire business models are compatible with constitutional protections.

If India prevails in this logic, it sets a precedent that spreads. Other countries facing similar questions about tech platforms and data rights can point to India's reasoning. Over time, regulatory frameworks worldwide shift toward viewing privacy as fundamental rather than negotiable.

The Business Model Question: Can WhatsApp Monetize Without Violating Rights?

This is the real strategic question Meta faces. The company needs to monetize WhatsApp. The company invested $19 billion to acquire the platform. The company wants data assets for AI training and advertising. But can the company achieve those goals while respecting the privacy rights India's Supreme Court is defending?

Potentially, yes. But it requires a fundamentally different business model than Meta currently operates.

Instead of exploiting metadata for targeted advertising without user awareness, Meta could:

- Implement truly transparent data sharing where users know exactly what data is collected and retained

- Provide genuine choice about data usage with meaningful consequences for opting out

- Monetize through subscription services rather than advertising targeted on personal data

- Separate WhatsApp's monetization from Meta's broader advertising network

- Implement data minimization where WhatsApp collects only information necessary for core messaging functionality

Each of these approaches is compatible with respecting privacy rights. None of them are compatible with Meta's current business model, which depends on extracting maximum data value from users.

Meta's reluctance to change its model is understandable. The company built its entire empire on understanding users deeply through data and using that understanding for advertising. Changing that model means changing the company's fundamental DNA.

But that's exactly what India's Supreme Court is pressuring. The court is saying: your current model isn't compatible with constitutional protections for privacy rights in India. Either change the model or face consequences.

What Happens Next: The February 9 Deadline and Beyond

When the Supreme Court adjourned until February 9, the justices essentially gave Meta homework. The company needs to explain its data practices in greater detail. The company needs to address concerns about metadata monetization. The company needs to justify how user consent is obtained and what users actually agree to.

Meta has a terrible track record of dealing with this kind of regulatory pressure. The company tends to minimize problems, provide legalistic non-answers, and hope regulators back down. This approach worked for years in the United States and Europe. It's not working in India.

Justice Kant's observation about monopoly power is particularly significant. If the court determines that WhatsApp operates as a monopoly, that opens entirely different regulatory pathways. Monopolies have different legal standards. They can't use their market position to impose unfavorable terms on users. They have higher obligations to users because users have no practical alternatives.

India's Competition Commission is already investigating WhatsApp on separate grounds. If the Supreme Court case concludes that WhatsApp exercises monopoly power, it strengthens the Competition Commission's case significantly.

The most likely short-term outcome is that Meta faces new compliance requirements. The company might need to:

- Implement better transparency about metadata collection

- Provide more meaningful user choice about data sharing

- Separate WhatsApp data from Meta's broader advertising networks

- Implement technical controls preventing unauthorized data sharing

- Face financial penalties for past violations

Longer term, if India's approach gains international traction, we could see global regulations forcing tech platforms to rethink data exploitation business models entirely.

The Precedent for Global Regulation

India's case matters beyond India because it demonstrates a regulatory model that other countries can adopt and adapt.

Brazil's government has shown willingness to take aggressive action against tech platforms. The country could apply similar logic to Facebook, Instagram, and other Meta properties operating in Brazil.

Europe's GDPR already provides strong protections, but European regulators could use India's reasoning to argue for even stronger constraints on metadata collection and exploitation.

Even in the United States, where tech companies have more regulatory latitude, the Supreme Court case signals to American regulators that major democracies are moving to constrain tech platform power. That creates political opportunity for regulation in the U.S.

The global tech industry is watching India carefully. If the country's Supreme Court and government can successfully impose constraints on Meta's data practices, other platforms face similar pressures. The regulatory landscape is shifting, and India is leading that shift.

What Users Should Do Now

For WhatsApp's 500 million Indian users, this court case represents the possibility of better privacy protections. But users shouldn't wait for legal victories before protecting themselves.

First, understand what you're agreeing to when you use any messaging platform. End-to-end encryption protects message content but not metadata. Even encrypted platforms collect information about your behavior.

Second, evaluate your alternatives. Signal offers stronger privacy protections and doesn't exploit metadata for advertising. Telegram emphasizes privacy and independence from ad networks. Neither service has 500 million users, but if privacy is your priority, that's a reasonable trade-off.

Third, minimize what you share. Use platforms for their essential purposes rather than as a primary communication channel. Don't overshare in group messages if you're concerned about metadata collection.

Fourth, support regulatory efforts to constrain data exploitation. When your government considers regulations on platform privacy practices, advocacy for strong protections is worthwhile.

The Broader Question: Privacy Rights as Fundamental vs. Negotiable

India's Supreme Court is essentially answering a foundational question: Is privacy a fundamental right that platforms must respect, or is it a negotiable commodity that users can trade for convenience?

Most of the world currently operates on the second assumption. Platforms collect what they want. Users can choose to use the platform or not. If users want the service, they accept the data trade-off.

India's court is moving toward the first assumption. Privacy is fundamental. Platforms can't negotiate away fundamental rights, even if users technically agree to that negotiation. The platform has obligations to users that go beyond respecting stated policies.

This distinction is profound. It suggests a future where tech platforms operate under different rules. Instead of "collect as much as possible within stated policies," the rule becomes "collect only what's necessary and respect users' privacy rights regardless of terms of service."

Implementing this shift requires regulatory courage. It requires courts willing to overturn established corporate practices. It requires governments willing to enforce restrictions that reduce corporate profitability. India's Supreme Court is demonstrating that such courage exists.

The case also demonstrates something important about global power dynamics. The United States invented the internet and created most major tech platforms. But the United States doesn't have exclusive authority over how those platforms operate globally. India has 1.4 billion people. India's government has regulatory authority over how foreign companies operate in India. When India's Supreme Court takes a stand on platform privacy practices, that stand carries weight.

Meta can't simply ignore India. The company can't threaten to withdraw WhatsApp from the country—doing so would damage Meta's growth narrative and trigger intense regulatory backlash. The company has to comply with Indian court decisions and government regulations. And when the company complies in India, it often has to comply globally to avoid managing different systems.

This is the practical power of large democratic governments with large populations and strong regulatory authority. India is using that power to defend what the country views as fundamental privacy rights. Other countries are watching, learning, and considering similar approaches.

Looking Forward: What 2025 Means for Tech Platforms and User Privacy

The Supreme Court case against WhatsApp isn't an isolated incident. It's part of a global movement toward stricter tech regulation centered on user rights.

In 2024 and 2025, we're seeing:

- More countries implementing data protection laws similar to GDPR

- Increased regulatory scrutiny of metadata practices

- Growing recognition that network effects create monopoly power

- Courts in major democracies willing to challenge platform business models

- Users becoming more aware of privacy issues and demanding protection

For Meta specifically, the company faces a strategic choice. Continue current data exploitation practices and face increasing regulatory pressure globally, or pivot toward privacy-respecting business models and sacrifice some short-term profitability.

The company has shown reluctance to make that choice voluntarily. But regulatory pressure from India, Europe, and potentially other countries may force the issue.

For users, this moment represents genuine possibility. Regulatory action that constrains platform data exploitation is achievable if governments have the will to pursue it. India's Supreme Court is demonstrating that such will exists.

FAQ

What is metadata and how does it differ from message content?

Metadata is information about communication patterns rather than the communication content itself. For WhatsApp, metadata includes who you contact, when you contact them, how frequently you communicate, and group membership. While WhatsApp's end-to-end encryption protects message content, it doesn't protect metadata. Meta collects extensive metadata separately from encrypted messages and uses this behavioral data to target advertising and train AI systems. Understanding this distinction is crucial because encryption protects message privacy but not communication pattern privacy.

Why does India's Supreme Court consider WhatsApp a monopoly?

Justice Sanjay Kant observed that WhatsApp operates as a practical monopoly in India because over 500 million users depend on the platform. When a messaging service reaches critical mass, users can't realistically switch to alternatives because their contacts aren't on those alternatives. Even if competing services exist, they're irrelevant if your network is exclusively on WhatsApp. This creates genuine monopoly power where the platform can impose unfavorable terms and users have nowhere else to go. The court used this monopoly status to argue that WhatsApp can't claim users freely consented to data practices when users have no practical alternative.

How does WhatsApp plan to monetize user data?

Meta acquired WhatsApp for $19 billion with the intention of eventually monetizing the massive user base. The company plans to integrate WhatsApp metadata with its existing advertising platforms and AI systems. By combining knowledge of your WhatsApp communication patterns with Facebook and Instagram data, Meta can create unprecedented user profiles for targeted advertising. The company also introduced WhatsApp Business, WhatsApp Pay, and WhatsApp Status as steps toward building an advertising platform rather than just a messaging service. Government lawyers in the Supreme Court case argued that this represents "commercial exploitation" of personal data collected without informed consent.

What does it mean that the IT ministry joined the Supreme Court case?

When India's IT ministry joined as a party to the case, it transformed the proceedings from a court decision about WhatsApp's practices to a government regulatory action. The ministry brings enforcement capacity, regulatory authority, and the power to impose compliance requirements and penalties that courts alone cannot enforce. This significantly increases the stakes for Meta because the company now faces not just judicial criticism but potential government regulation and penalties. The IT ministry can propose specific data protection measures, work with other agencies, and implement enforcement mechanisms that make compliance mandatory rather than optional.

What happens if Meta refuses to comply with India's Supreme Court decisions?

Meta has limited options if it refuses to comply with India's Supreme Court. The government could ban WhatsApp entirely, which would destroy Meta's largest user market. The government could impose severe financial penalties. India could block Meta's other platforms like Facebook and Instagram. These consequences are severe enough that Meta effectively must comply with Indian court decisions and government regulations. The company's global business makes complete withdrawal from India impractical, which means compliance becomes the only realistic option.

How might India's case influence regulation in other countries?

India's Supreme Court case sets a precedent that other countries can reference and adapt. Brazil has shown willingness to take aggressive action against tech platforms. European regulators implementing GDPR can use India's reasoning to argue for stronger constraints on metadata collection. Even the United States, where tech companies have regulatory latitude, faces political opportunity to implement similar privacy protections if other democracies do so first. The case demonstrates that major democracies with large populations have regulatory authority and the willingness to use it against tech platforms, creating a global shift toward stricter privacy protections.

What should WhatsApp users do to protect their privacy?

WhatsApp users should recognize that end-to-end encryption protects message content but not metadata or behavioral patterns. Users concerned about privacy should minimize use of WhatsApp for sensitive communications, use alternative services like Signal that prioritize privacy over engagement metrics, and avoid oversharing in group messages if metadata collection concerns them. Users should read platform privacy policies specifically for metadata collection practices rather than assuming encryption means complete privacy. Supporting regulatory efforts that constrain data exploitation is also valuable, as individual user choices alone cannot override platform business models that extract data at scale.

Is WhatsApp's encryption claim misleading?

WhatsApp's encryption claim is technically accurate but contextually misleading. Messages are genuinely encrypted end-to-end, meaning Meta can't read message content. However, encryption doesn't prevent metadata collection or the behavioral data harvesting that happens separately from messages. WhatsApp's marketing emphasizes encryption to suggest complete privacy protection when in reality it only protects message content. This represents effective privacy theater where one legitimate protection (encryption) implies protections that don't exist (metadata protection). The Supreme Court's concern was partly about this gap between what users think they're getting (complete privacy) and what they actually get (only message encryption while metadata is harvested).

What regulatory options does India have beyond the Supreme Court case?

India has multiple regulatory tools available beyond the Supreme Court case. The IT ministry can implement data protection rules requiring WhatsApp to implement specific security measures and transparency requirements. The Competition Commission can pursue antitrust cases against WhatsApp based on monopoly status and anticompetitive practices. The government can impose data localization requirements requiring WhatsApp to store Indian user data within India. The government can implement licensing requirements that make WhatsApp subject to additional compliance obligations. The government can impose financial penalties for privacy violations. Any combination of these approaches could fundamentally change WhatsApp's operating environment in India.

Could this case force Meta to change its global business model?

India's case creates pressure for global model changes because Meta typically operates the same systems globally rather than building separate versions for different countries. If India requires WhatsApp to implement stronger data protections, separate metadata from advertising networks, or increase transparency, Meta often implements these changes globally rather than managing different systems. However, the company could theoretically implement Indian requirements only for Indian users. The practical pressure comes from replication risk. If India successfully constrains Meta's data practices, other countries follow, eventually forcing global business model changes regardless of the company's preference.

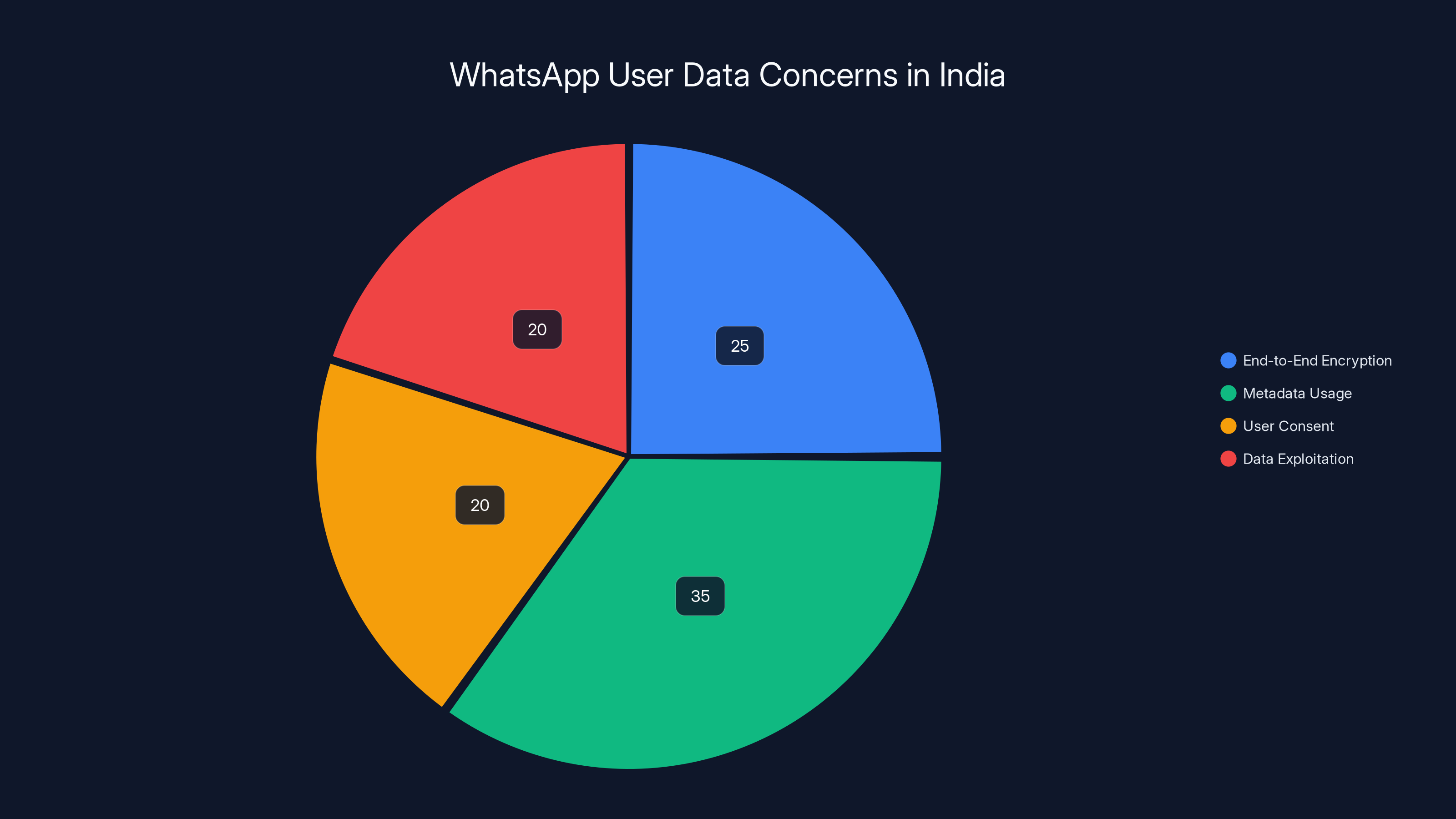

Estimated data shows that metadata usage (35%) is the top concern among WhatsApp users in India, followed by end-to-end encryption (25%) and issues of user consent and data exploitation (20% each).

Conclusion: When Privacy Rights Collide With Platform Profit

India's Supreme Court delivered a message that tech companies have been avoiding for years: you cannot treat privacy as a negotiable commodity. You cannot exploit user data simply because users technically agreed to terms of service. You cannot hide data practices behind encryption claims that only partially protect privacy. When platforms reach monopoly scale and become essential infrastructure, they carry obligations to respect fundamental rights regardless of profit implications.

For WhatsApp and Meta, this case represents an inflection point. The company can continue current practices and face escalating regulatory consequences globally, or the company can reimagine its business model around genuine privacy respect rather than privacy theater.

For users, this moment demonstrates that regulatory action is possible. Courts in major democracies can and will challenge tech platform power when democratic governments provide the political will. Privacy rights can be protected if countries have the courage to prioritize user welfare over corporate convenience.

For the global tech industry, India's case signals the direction of regulation. Other countries are watching how courts handle platform data exploitation. The regulatory precedent being set in New Delhi will influence policy decisions in São Paulo, Brussels, and eventually Washington. Tech platforms built on data exploitation face an uncertain future. Platforms built on genuine privacy protection and user respect have competitive advantage.

The February 9 deadline isn't just about WhatsApp's response to court questions. It's about whether tech platforms can adapt to a world where privacy is fundamental or whether they'll continue until forced to change by regulatory action. Based on Meta's history, the company will likely continue until forced. Which means regulation will become increasingly harsh, increasingly global, and increasingly effective at constraining platform power.

India's Supreme Court just fired the opening salvo in that larger battle.

WhatsApp holds a dominant position with an estimated 500 million users in India, highlighting its monopoly status. Estimated data.

Key Takeaways

- India's Supreme Court rejected Meta's monopoly exploitation of 500 million WhatsApp users, declaring privacy is fundamental and cannot be negotiated away

- Metadata harvesting—who you contact, when you contact them, patterns in behavior—remains completely separate from message encryption and represents the real privacy threat

- User consent to terms of service is broken when platforms have monopoly power and users have no practical alternatives, making consent theoretically invalid

- Meta plans to integrate WhatsApp metadata with Facebook and Instagram advertising networks, creating unprecedented user profiles for targeted ad targeting

- India's regulatory action sets global precedent that other democracies are watching and will replicate, shifting regulatory landscape toward privacy protection over platform profit

Related Articles

- Google's $135M Android Data Settlement: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Big Tech's $7.8B Fine Problem: How Much They Actually Care [2025]

- WhatsApp's Strict Account Settings: Ultimate Cyberattack Protection [2025]

- France's VPN Ban for Under-15s: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Image Generation Remains Uncontrolled [2025]

- Facial Recognition and Government Surveillance: The Global Entry Revocation Story [2025]

![India's Supreme Court vs WhatsApp: Privacy Rights Under Fire [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/india-s-supreme-court-vs-whatsapp-privacy-rights-under-fire-/image-1-1770124003130.jpg)