Introduction

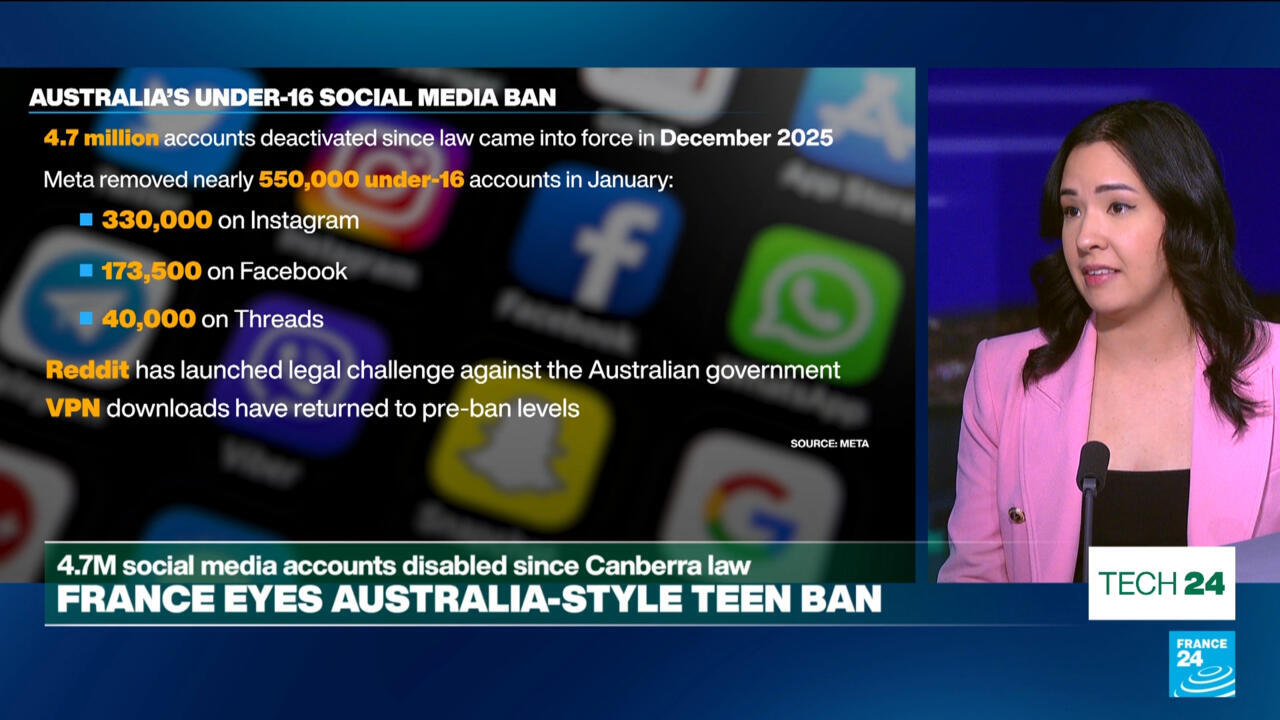

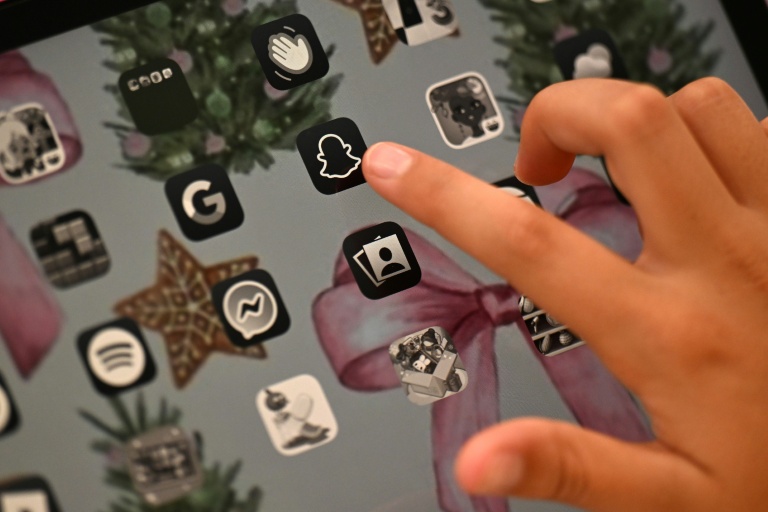

France just took a bold move that has privacy advocates scrambling and tech companies sweating. The country's National Assembly passed legislation banning children under 15 from using social media platforms. But here's where it gets complicated: lawmakers are now eyeing VPNs as a potential loophole they need to close.

The question everyone's asking is simple but loaded: Can you actually prevent teenagers from using VPNs? And should you?

This isn't just a French problem anymore. What happens in Europe tends to ripple outward. Other nations are watching closely, wondering if they should adopt similar measures. The tech industry is split. Some see legitimate child safety concerns. Others view it as a dangerous precedent for digital freedom.

Let me be straight with you: this is messier than it sounds. The legislation attempts to solve real problems like social media addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health issues in teenagers. Nobody disputes those are serious concerns. But the proposed solution raises thorny questions about parental control, technical feasibility, and whether governments should be regulating internet access at this level.

The French government's reasoning is sound on the surface. Social media platforms have documented harmful effects on adolescent mental health. Studies consistently show increased depression, anxiety, and body image issues among heavy social media users. So banning the platforms themselves makes intuitive sense as a protective measure.

But here's the problem: determined teenagers have been bypassing restrictions since the internet existed. VPNs are one of the easiest workarounds. They're legal, widely available, and increasingly user-friendly. A 14-year-old can download a VPN app in seconds and suddenly they're accessing anything from anywhere. That's why French lawmakers are considering whether to restrict VPN use itself, which opens a Pandora's box of technical, legal, and ethical questions.

This article digs into what France is actually proposing, why it's so technically complicated, and what it means for privacy, parental authority, and digital freedom worldwide. We'll look at the feasibility of enforcing such rules, the international precedents, and what experts are actually saying when the cameras aren't around.

TL; DR

- France's Ban: Children under 15 are banned from social media starting 2025, with lawmakers now considering VPN restrictions

- The Loophole Problem: VPNs let users mask their location and identity, making age verification nearly impossible to enforce

- Technical Reality: Blocking VPNs at scale requires deep packet inspection and ISP-level filtering that most democracies avoid

- Privacy Concerns: Restricting VPNs undermines digital privacy for all users, not just teenagers, setting dangerous precedents

- International Implications: Other countries are watching to see if this approach works before considering similar measures

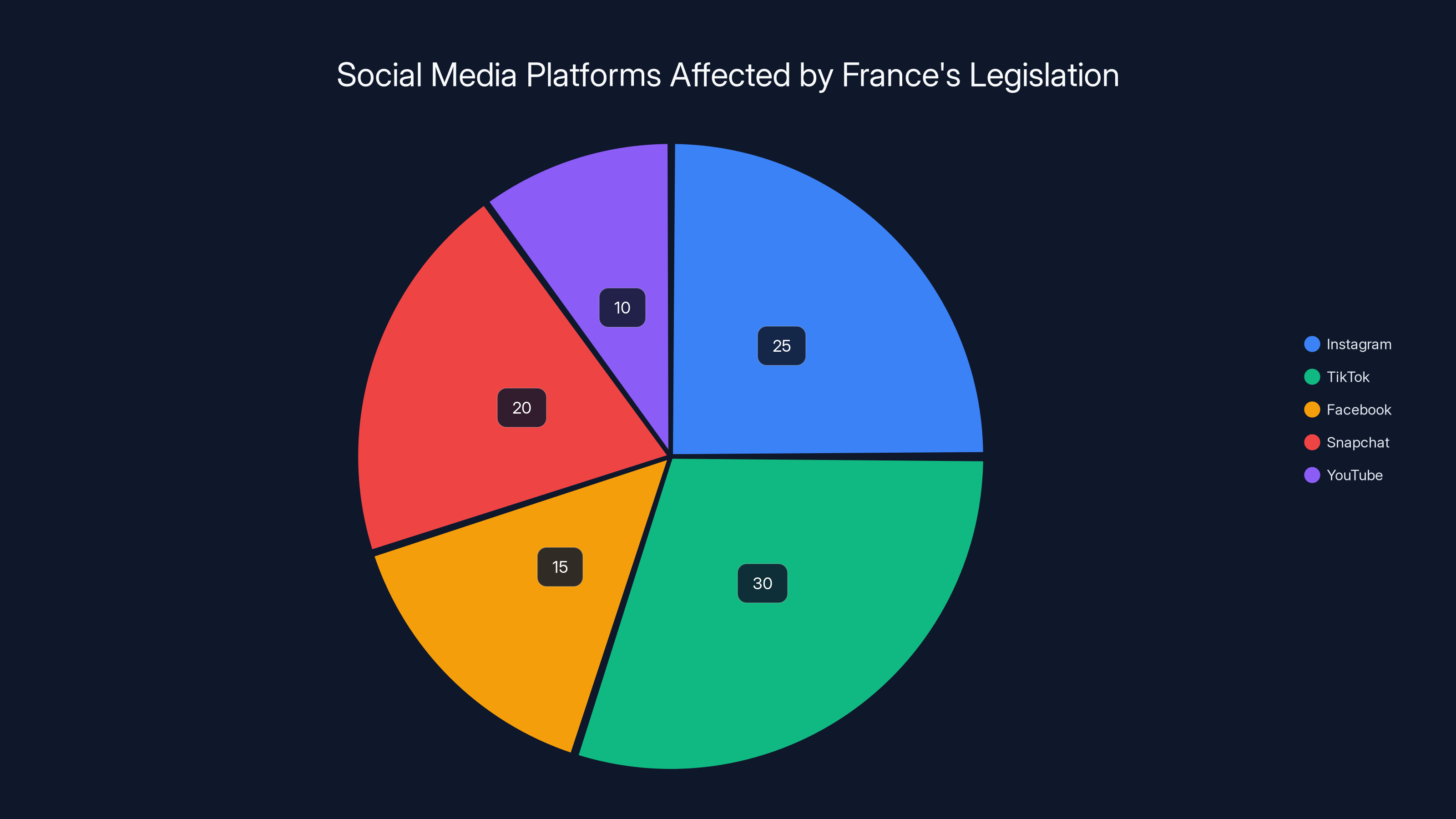

Estimated data shows TikTok and Instagram are the most popular platforms among children under 15 affected by France's new legislation.

What France Is Actually Proposing

Let's start with what the law actually says, because the headlines have been pretty vague. France's National Assembly passed legislation that prohibits children under 15 from accessing social media platforms. This isn't a suggestion or guideline. It's a hard legal restriction with potential penalties for both platforms and families.

The bill targets major platforms: Instagram, Tik Tok, Facebook, Snapchat, You Tube, and similar services. Age verification becomes mandatory. Platforms must implement systems to confirm users are over 15 before allowing access. This sounds straightforward in theory. In practice, it's a nightmare of technical and privacy complications.

But the social media ban alone isn't what has privacy advocates concerned. People expect age-gating. It's standard practice for plenty of online services. The contentious part is what comes next: the potential restrictions on VPNs.

After the social media ban passed, French lawmakers started openly discussing how to prevent teenagers from circumventing the rules using VPNs. This is where the proposal becomes genuinely problematic. You can't ban a technology outright without massive infrastructure investment and civil liberties concerns.

The French government hasn't officially released a detailed plan for VPN restrictions yet. Instead, it's in the "evaluation phase" where they're studying the feasibility. This means they're working with internet service providers, tech companies, and government agencies to understand what blocking VPNs would actually require.

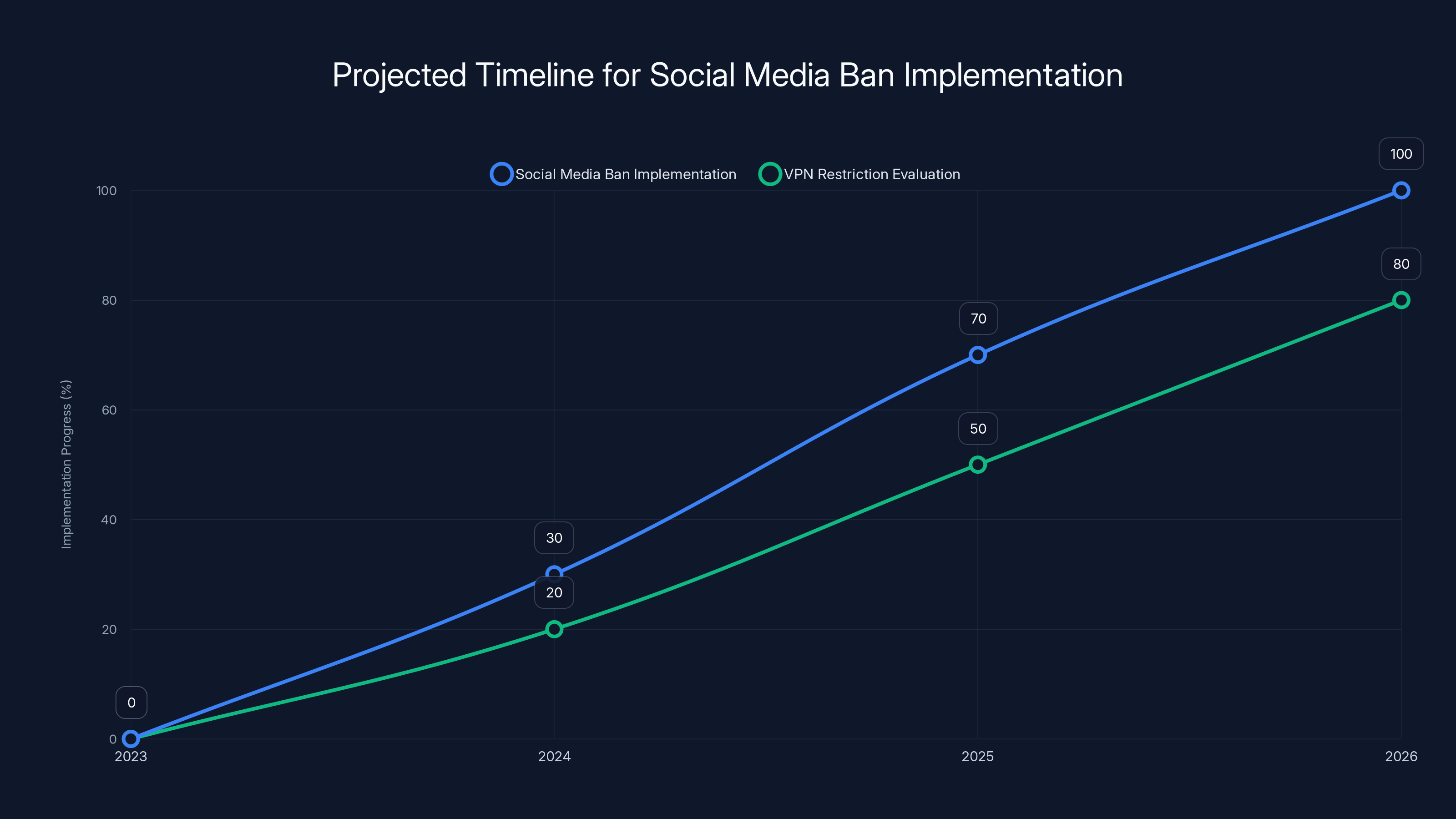

The timeline matters here. France isn't planning to implement VPN restrictions immediately. First comes the social media ban in 2025. Then comes the monitoring phase, where they'll track how many teenagers successfully bypass the restrictions using VPNs. If that number is significant (which experts predict it will be), then they'll likely move forward with VPN restrictions.

This staged approach has political advantages. It lets France look tough on child protection without immediately facing the backlash that would come from restricting privacy tools for everyone. But it also signals clear intent: they're planning this. Other governments will be watching how France handles implementation.

The broader context matters too. France isn't unique in wanting to regulate tech companies on behalf of children. The European Union has been pushing harder on platform regulation for years. There's genuine public health concern about social media's impact on young people. The question isn't whether to protect kids. The question is how to do it without breaking privacy for everyone else.

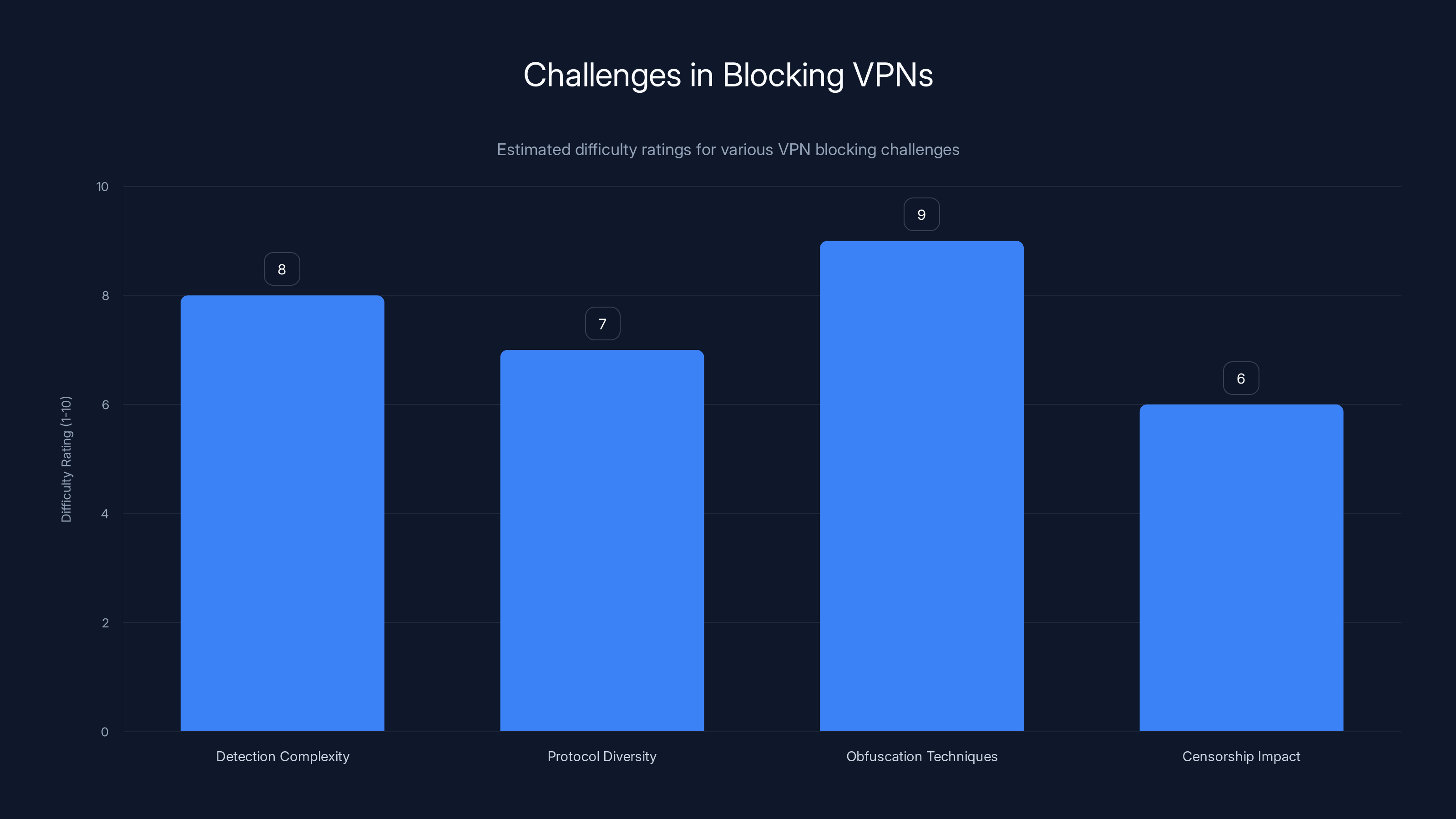

Estimated data shows that obfuscation techniques pose the highest difficulty in blocking VPNs, followed by detection complexity and protocol diversity.

The Technical Reality of Blocking VPNs

Here's what France would need to actually block VPNs at scale: deep packet inspection (DPI) technology deployed across every internet service provider in the country. This is the only way to identify VPN traffic and block it at the network level.

Deep packet inspection sounds straightforward. Your ISP examines the data traveling through their network, identifies which traffic is encrypted VPN communication, and blocks it. Done. Except it's not that simple, and this is where the technical realities collide with political intentions.

First, detecting VPN traffic is getting harder every year. Modern VPN protocols are designed specifically to look like normal, legitimate internet traffic. They encrypt their headers, randomize their patterns, and use standard ports that also carry regular HTTPS traffic. If you block all traffic on port 443 or 80 to stop VPNs, you also block regular websites. That's not acceptable.

Second, there are dozens of VPN technologies. Open VPN, Wire Guard, IKEv 2, Shadowsocks, Wireguard, and proprietary protocols each behave differently. Blocking one doesn't block the others. As soon as France blocks one VPN method, developers ship alternatives that look completely different.

Third, there's the arms race problem. For every detection method, VPN developers create obfuscation techniques. These tools specifically designed to make VPN traffic look like regular browsing. Services like Tor Browser and obfs 4 proxies can disguise VPN traffic as normal HTTPS. Once obfuscation becomes standard, detection becomes nearly impossible without inspecting actual content, which is both technically difficult and politically toxic.

Fourth, blocking VPNs requires censoring infrastructure that affects everyone, not just teenagers. Your grandmother needs her VPN for secure banking. Business travelers need VPNs for remote work. Privacy-conscious adults use VPNs as standard practice. Any blanket VPN blocking affects all of them.

Let's do the math on what this infrastructure costs. Deep packet inspection hardware for nationwide ISP deployment could run hundreds of millions of euros. Then add ongoing maintenance, updates, developer salaries, and the constant battle against new evasion techniques. France would need to sustain this investment indefinitely, with no guarantee of success.

There's also the architectural problem. France's internet infrastructure connects to the broader European network and the global internet. You can't isolate French traffic without physically separating from the rest of the network. That's not how the internet works. Data flows across borders constantly. Any detection system would need to work at the border, which has its own complications.

How Age Verification Actually Works (and Why It Fails)

Before worrying about VPNs, we need to understand the actual enforcement mechanism: age verification. The social media ban requires platforms to verify that users are over 15. This is the foundation everything else rests on.

Age verification is one of those ideas that sounds simple but falls apart immediately under scrutiny. There are roughly four ways to verify age online: government ID, credit card, biometric data, or parental consent. Each has massive problems.

Government ID verification means uploading a photo of your passport or driver's license. Privacy nightmare. You've now given a social media company a scan of your government ID, which is way more sensitive than your browsing habits. These companies have incentive to monetize that data. Hackers want it. This creates massive security risks.

Credit card verification assumes everyone has a credit card registered to their real name and current address. Young people don't always have this. Even if they do, a teenager can easily use their parents' card. From the company's perspective, they've verified the account holder's age, not the actual user of the account.

Biometric verification means using facial recognition to confirm age. This has some appeal (you can't fake your face as easily as identity documents), but it requires massive camera infrastructure on devices and is deeply intrusive. Plus, facial recognition for age detection has accuracy problems, especially with teenagers whose faces are still changing.

Parental consent is the most practical approach. Parents verify themselves, then consent to their child's account. But enforcement is the problem. How does a platform confirm parental consent is genuine? What stops a teenager from faking parental approval? The system relies on parents monitoring, which brings us back to parental responsibility rather than platform enforcement.

None of these methods are foolproof. In practice, age verification systems have failure rates between 15 and 40 percent depending on the method used. That means for every 100 teenagers trying to access Instagram, 15 to 40 of them successfully bypass the verification.

Now add in VPN usage. A teenager can use a VPN from any country, making their location appear to be outside France. The age verification system still functions (they'll still be blocked if they can't provide verification), but the VPN doesn't prevent age verification. It prevents location-based enforcement.

The real problem isn't VPNs preventing age verification. It's that age verification itself is porous. Teenagers are creative. They'll find ways around whatever system gets implemented. VPNs are just one tool in a larger toolkit of evasion strategies.

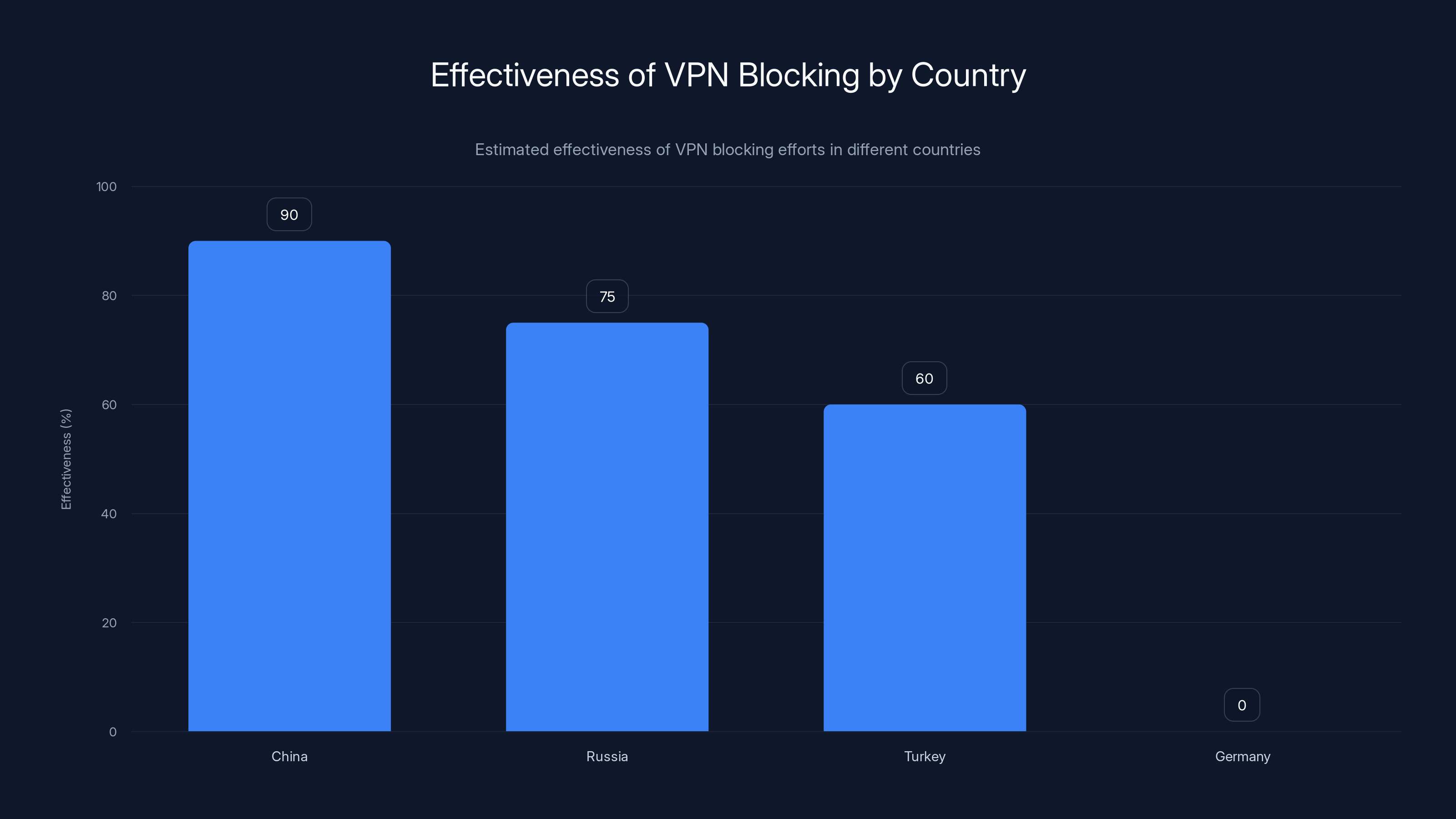

Estimated data shows China has the highest VPN blocking effectiveness at 90%, while Germany has not implemented such measures due to privacy concerns.

International Precedent: What Other Countries Have Tried

France isn't inventing this problem from scratch. Other countries have attempted similar restrictions, and the track record is instructive.

China has the most aggressive VPN blocking program globally. They invested heavily in DPI technology and regularly update their blocking mechanisms. But even with the full power of an authoritarian government, they haven't eliminated VPN use. Tech-savvy users find workarounds. Younger people are particularly creative at finding new tools.

Russia has been blocking VPNs for years as part of broader internet censorship. They've achieved perhaps 70-80% effectiveness at blocking the most popular VPN services. But newer services, smaller players, and obfuscation tools consistently slip through. It's an endless game of whack-a-mole.

Turkey attempted VPN blocking in 2016 and declared it successful. Did it eliminate VPN usage? No. It just shifted people to less mainstream services and obfuscation techniques. Usage patterns changed, but people seeking VPNs still found them.

The European precedent is actually more interesting. The EU hasn't tried nationwide VPN blocking. Some EU countries have considered it, but the combination of privacy rights protections and technical skepticism has prevented implementation. Germany, for instance, explicitly rejected VPN blocking proposals, citing both privacy concerns and the known ineffectiveness.

What's notable about these international examples is that none of them succeeded at complete VPN elimination while maintaining internet freedom. The authoritarian approaches achieved partial success through aggressive, continuous enforcement. Democratic countries haven't attempted it because the costs are too high and the benefits too uncertain.

France faces a choice: adopt more authoritarian network control measures (which contradicts European values and law), or accept that some teenagers will bypass age verification through VPNs. There's no third option that provides strong enforcement and preserves privacy.

The EU's Digital Services Act, passed in 2023, gives us clues about how European regulators want to handle this. Rather than technical blocking, the DSA emphasizes transparency, user rights, and accountability from platforms. It's a lighter-touch regulatory approach that acknowledges the limits of technical enforcement.

The Parental Control Problem

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough: parental authority. If a parent wants their child using a VPN, should the government prevent that?

Parents have legitimate reasons to give their kids VPNs. Security on public Wi-Fi, privacy from ISP tracking, avoiding surveillance in countries with censorship. A parent might set up a family VPN so their teenager can browse securely. Are we really going to make that illegal?

The French legislation tries to navigate this by framing restrictions as protective rather than absolute. But the practical effect is the same: if you're blocking VPN usage at the ISP level, you're blocking it for everyone, regardless of parental intent.

This creates a weird legal situation. A parent could theoretically be liable for their child using a VPN, even if the parent approved it for legitimate security reasons. That's overcriminalization of what should be a family decision.

Alternatively, France could implement VPN restrictions at the device level rather than the network level. Apps could be banned from app stores. But that just shifts the problem. Teenagers would sideload VPN apps, use browsers with built-in VPN features, or access VPNs through websites rather than dedicated apps. Device-level restrictions are easier to bypass than network-level ones.

The parental control angle also reveals something important about why this legislation matters: it's fundamentally about who gets to make decisions about children's internet access. Is it parents? Governments? Platforms? The answer determines whether you see VPN restrictions as child protection or government overreach.

Most privacy advocates and civil liberties organizations land on parental authority as primary. Parents should decide what their children access online, within legal bounds. Governments should enforce minimum standards (no illegal content, no exploitation), but broader restrictions should be parental decisions.

From this perspective, government-imposed VPN blocking crosses a line. It removes a tool parents might legitimately want to use for their children's security and privacy.

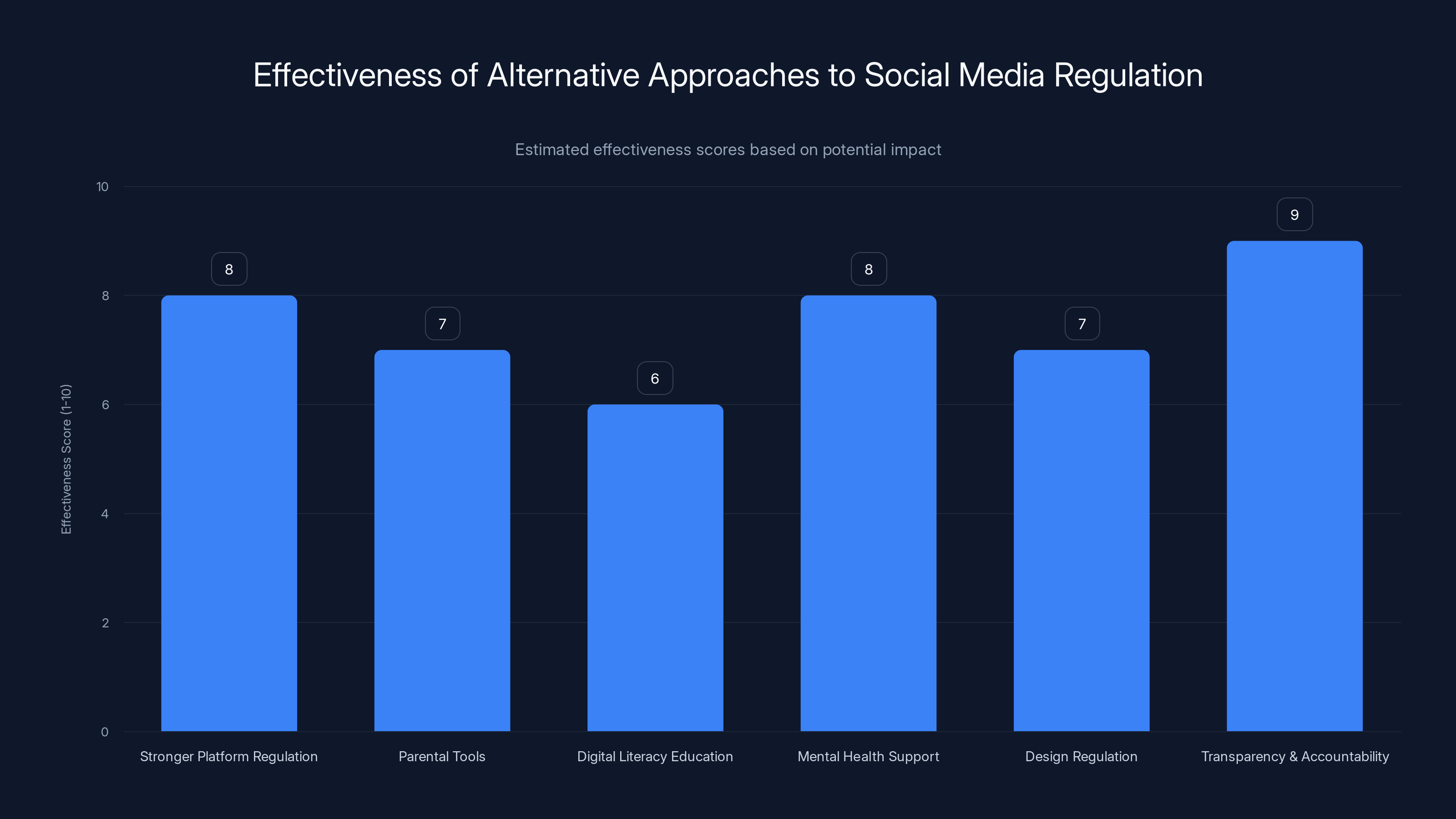

Estimated effectiveness scores suggest that transparency and accountability may have the highest impact on mitigating social media issues, followed closely by mental health support and stronger platform regulation.

Mental Health and Social Media: The Real Problem

Before diving deeper into enforcement challenges, let's acknowledge why France is doing this. The concerns about social media's impact on young people are legitimate and well-documented.

Multiple studies show correlations between heavy social media use and depression, anxiety, poor sleep, and body image issues in teenagers. The research isn't uniformly damning (correlation isn't causation, and most teenagers who use social media don't develop mental health problems), but the risks are real.

Platforms themselves have documented internal research showing their products can harm young people's mental health. Instagram's own research found that 32% of teenage girls would have felt better about their bodies if the platform didn't exist. Tik Tok's algorithm is specifically designed to maximize engagement, which means serving content that triggers strong emotional responses, including anxiety and inadequacy.

So the motivation for restricting access is sound. Protecting kids from platforms that profit by keeping them engaged is a legitimate government interest.

But here's where the plan falls apart: banning the platforms solves one problem while creating others.

First, it treats social media as the enemy rather than examining how platforms are designed. Instagram isn't addictive because it exists. It's addictive because Instagram's parent company, Meta, deliberately designed it to be maximally engaging. The algorithmic feed, the like count, the engagement metrics, the infinite scroll, the algorithmic recommendation engine. These are choices.

Second, banning platforms doesn't address why teenagers want to use them. Social connection, self-expression, status signaling, entertainment, and genuine community. These needs don't go away when you ban Instagram. Teenagers will find other outlets, which might be even less healthy. Some will move to unmoderated platforms with worse safety protections.

Third, a blanket ban ignores that some teenagers benefit from social media. For chronically ill kids who can't leave home, online communities are lifelines. For LGBTQ+ youth in unsupportive areas, digital spaces provide community and identity exploration that's difficult to access otherwise. For teenagers with anxiety or social disabilities, online spaces can be easier to navigate than face-to-face interaction.

A more nuanced approach would regulate how platforms operate rather than banning access outright. This is actually what the EU's Digital Services Act attempts: requiring platforms to change their design (removing algorithmic recommendations, limiting notifications, providing content moderation) rather than banning the services.

France's approach of total prohibition is blunt and will likely backfire. It also sets a precedent that governments can simply ban services they deem harmful. That precedent is dangerous beyond just social media.

The Privacy Rights Angle

Let's talk about what really bothers privacy advocates about this proposal: it treats VPNs as something to be eliminated rather than protected.

VPNs serve legitimate purposes. They protect your data from your internet service provider, from network administrators, from hackers on public Wi-Fi. They help journalists protect sources. They let political activists avoid surveillance. They let people access information in censored countries. VPNs are privacy infrastructure.

When governments move to block VPNs, they're not just targeting teenagers using them to access Instagram. They're attacking privacy tools that adult citizens rely on for legitimate security and freedom reasons.

This is the chilling effect problem. Once you establish that governments can block VPNs for child protection reasons, you've created the precedent for other blocks. Tomorrow it might be "protecting children from misinformation." Next week it's "protecting national security from foreign platforms." Then it's just routine censorship justified by whatever contemporary concern is trendy.

The privacy rights perspective holds that tools like VPNs are foundational to digital freedom. Restricting them requires an extraordinarily strong justification. "Teenagers might use them to bypass a social media ban" doesn't reach that threshold.

Even the mechanism creates privacy problems. Deep packet inspection requires ISPs to examine all your traffic. That's surveillance infrastructure. Building it to block VPNs today means it exists to monitor other things tomorrow. Once you've normalized network-level inspection in a country, authoritarian mission creep becomes possible.

This is why international privacy organizations, from the Electronic Frontier Foundation to the Article 19 advocacy group, are all warning against VPN blocking. It's not that they don't care about child protection. They care about not building the infrastructure for pervasive surveillance.

The social media ban for under-15s is projected to be fully implemented by 2025, with VPN restrictions potentially following by 2026. Estimated data based on current discussions.

What About Encrypted Messaging and the Bigger Picture?

VPN restrictions don't exist in a vacuum. They're part of a larger regulatory push that includes restrictions on encrypted messaging, encryption backdoors, and expanded government surveillance capabilities.

The EU and various member states have been pushing tech companies to weaken encryption to allow law enforcement access. Platforms like Whats App and Signal provide end-to-end encryption, meaning not even the companies can access message content. Some governments argue this enables criminal activity and terrorism.

But here's the problem: encryption either works or it doesn't. You can't create a "secure encryption with a special backdoor for law enforcement only." The moment you build that backdoor, you've weakened encryption for everyone. Criminals, hackers, and authoritarian governments can exploit the same backdoor.

So when France moves to restrict VPNs while simultaneously pushing for encryption backdoors, you can see a pattern: reduced privacy, increased government surveillance capability, and reduced individual digital autonomy.

These policies sound protective when framed as child safety or crime prevention. But collectively they amount to a significant shift in how governments relate to digital privacy. From protecting privacy as a right to treating privacy as something governments grant (and can revoke) for security purposes.

The intersection also matters for implementation. If you restrict VPNs but don't restrict encrypted messaging, determined teenagers will just shift to messaging platforms with built-in encryption to coordinate VPN usage, cloud storage access, or other workarounds. The whack-a-mole problem gets worse.

That's why some countries pursuing VPN blocking also push for mandatory encryption backdoors or restricted access to encrypted messaging. They're trying to control the entire privacy infrastructure. France hasn't gone that far officially, but watch for it if the social media ban moves forward.

Alternative Approaches: What Could Actually Work

If total VPN blocking isn't feasible and privacy violations are unacceptable, what's left?

The first alternative is stronger platform regulation without access bans. The EU's Digital Services Act requires platforms to reduce algorithmic recommendation, provide better content moderation, improve transparency, and give users more control. These changes reduce addictiveness without banning services.

Second is better parental tools. Instead of government restriction, give parents technology to monitor and control their children's app usage. App store controls, device-level restrictions, and parental dashboards let parents make informed decisions without government surveillance infrastructure.

Third is digital literacy education. Teach teenagers how social media works, how algorithms manipulate engagement, how to recognize unhealthy usage patterns, and how to take breaks. This doesn't prevent access but promotes healthier relationships with the platforms.

Fourth is mental health support. Increase funding for adolescent mental health services, school counselors, and therapy availability. If social media is damaging mental health, address that through treatment rather than access restriction.

Fifth is design regulation rather than access restriction. Require platforms to redesign features that are known to be harmful. Ban infinite scroll, algorithmic recommendations based on engagement, and like counts that encourage social comparison. Make platforms less addictive without making them inaccessible.

Fifth is transparency and accountability. Require platforms to publish their algorithms, content moderation standards, and the impact of their design choices. Let independent researchers study the effects. Require platforms to conduct impact assessments before launching new features that target young users.

These alternatives aren't perfect. Parental controls can fail. Teenagers can still find workarounds. Education doesn't magically prevent bad choices. But they achieve the protective goals without building mass surveillance infrastructure or setting precedent for broader internet restrictions.

They also respect individual autonomy and privacy rights that are foundational to democratic societies. You're not preventing access based on age and government mandate. You're empowering individuals to make better choices with information and tools.

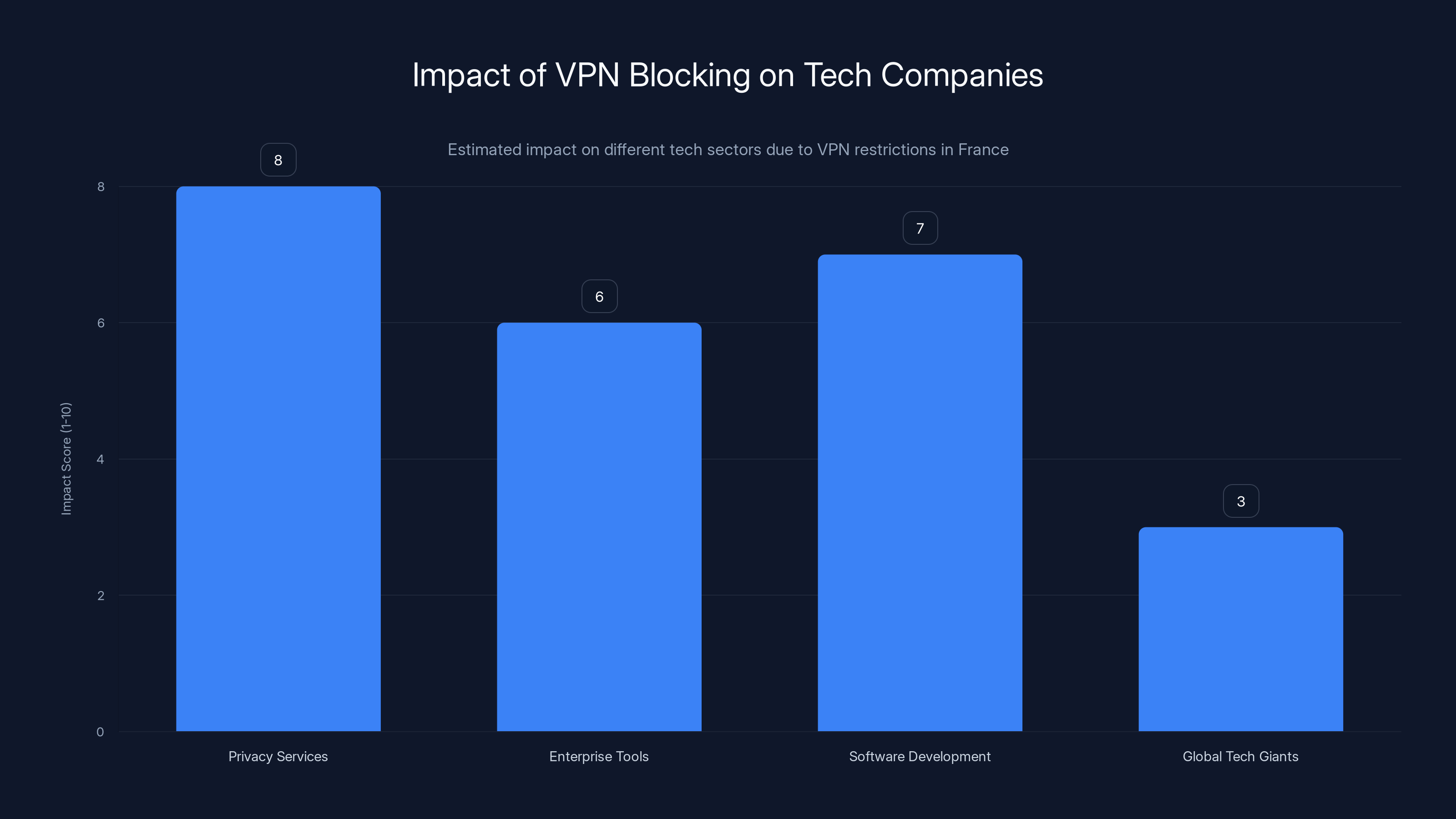

Estimated data suggests privacy services face the highest impact from VPN blocking, while global tech giants may benefit due to reduced competition and increased data access.

The Economic Impact on Tech Companies

Here's the piece most articles skip: what does VPN blocking do to companies operating in France?

Any company providing privacy-focused services gets hit first. Nord VPN, Express VPN, Surfshark, Proton, Mullvad. These companies have substantial European customer bases. A French ban would pressure other European countries to follow, potentially cutting off an entire region.

But the impact spreads wider. Any company with legitimate need for VPN usage (business software, remote work tools, enterprise security) faces complications in the French market. Slack, Zoom, Citrix, all enterprise tools that people might access through VPNs suddenly have legal uncertainty in France.

Software development companies are affected. Developers need to access company resources securely. If VPN blocking becomes mandatory, development teams in France can't easily work with remote infrastructure. This could drive software development and tech talent away from France.

Meanwhile, global tech giants like Meta, Google, Tik Tok, and Amazon benefit. The social media ban limits competition from platforms those companies don't operate. The VPN blocking reduces user privacy and government oversight of those companies' data collection. It's actually good for big tech to have governments restricting privacy tools while permitting massive data harvesting by corporations.

The economic inefficiency matters too. Building nationwide VPN blocking infrastructure is a sunk cost that generates zero economic value. That's billions in infrastructure spending that could go toward education, healthcare, or actually productive investments.

France's tech sector is already smaller than counterparts in the UK, Germany, and Scandinavia. Privacy-focused regulations (like strong GDPR enforcement) hurt tech competitiveness but build trust. Privacy-restricting regulations (like VPN blocking) undermine competitiveness without providing offsetting benefits.

So the economic case for VPN blocking is weak. It costs money to implement, harms legitimate businesses, and benefits only the largest tech companies who can survive regulatory complexity.

Timeline and Political Reality

The social media ban for under-15s is scheduled for 2025, so we're looking at implementation happening now. The VPN evaluation phase will determine whether to proceed with restrictions by late 2025 or 2026.

Politically, this matters. French President Emmanuel Macron is framing this as child protection during a period of broader digital regulation discussions in the EU. It's popular with voters who are concerned about youth mental health and teen smartphone addiction.

But implementation gets messier quickly. Platforms need time to build age verification systems. Those systems need to be effective enough to actually work. Testing phase might reveal that 60% of attempts to verify age fail, which would undermine support for the law.

Meanwhile, tech companies and privacy advocates will be filing legal challenges. The law will face constitutional challenges in French courts and possibly the European Court of Justice. These legal processes can take years.

Other EU countries will watch how France's implementation goes before deciding whether to follow. If it's a disaster, they might not. If it works better than expected (which seems unlikely), copycats will emerge.

The international dimension matters too. The US government is largely hands-off on this, though some US-based tech companies are affected. China and Russia are probably amused at watching democracies voluntarily build surveillance infrastructure. Other democracies are concerned about the precedent.

Politically, the momentum is with regulation. More countries are moving to restrict tech's power and protect youth. Whether the French approach specifically wins out depends on real-world results. If it fails obviously, the approach discredits itself. If it succeeds partially (social media ban works, VPN blocking half-works), you might see international adoption.

What's at Stake for Digital Freedom

This isn't just about teenagers and Instagram. It's about the digital freedom infrastructure we're building for the next decade.

Every precedent matters. Once you establish that governments can block tools for protection reasons, you've opened the door. The next government might block different tools for different reasons. Over time, you could end up with significant restrictions on what technologies are legally available.

This affects adults primarily. Privacy tools, encryption, anonymization technologies. All of these could be restricted on the theory that they help bad actors (terrorists, criminals, extremists). The protection justification always sounds reasonable.

It also affects developing countries and authoritarian contexts. What starts as a European child protection measure becomes a playbook for authoritarian governments wanting to restrict citizen access to privacy tools. They'll cite the French example.

There's also the fundamental question of digital rights. Do you have a right to privacy online? To encryption? To tools that protect your anonymity? Or are those privileges governments grant and can revoke?

This depends on how you view digital rights. The European perspective traditionally emphasizes privacy as a human right. The surveillance perspective views privacy as something traded for security and protection. Which worldview wins in Europe over the next 5-10 years will matter enormously.

France's VPN ban proposal is a test case for that fundamental question. It's about whether democracies can build surveillance infrastructure while remaining democratic.

FAQ

What exactly is France banning regarding children and social media?

France's National Assembly passed legislation prohibiting children under 15 from accessing social media platforms like Instagram, Tik Tok, Facebook, Snapchat, and You Tube. The law requires age verification before access and mandates platforms implement systems to confirm users are over 15. This is a hard legal restriction with potential penalties for both platforms and families, distinct from age-gate recommendations that many platforms currently offer.

How would France actually block VPNs if they decide to restrict them?

France would need to deploy deep packet inspection (DPI) technology across all internet service providers. DPI examines data packets traveling through networks to identify VPN traffic and block it at the network level. However, this method faces significant challenges because modern VPNs are designed to look like regular internet traffic, obfuscation tools can disguise VPN connections, and the infrastructure investment would cost hundreds of millions of euros with no guarantee of success. The ongoing cat-and-mouse game with VPN developers would be expensive to sustain indefinitely.

Why are privacy advocates concerned about VPN blocking beyond teenager protection?

Privacy advocates worry that restricting VPNs establishes dangerous precedent. VPNs serve legitimate purposes for journalists protecting sources, activists avoiding surveillance in censored countries, business professionals securing remote work connections, and everyday users protecting privacy from ISPs and hackers. Building surveillance infrastructure (deep packet inspection) to block VPNs means that infrastructure exists for other monitoring purposes. Once normalized, governments could expand it for other censorship goals, from "misinformation protection" to "national security concerns." The precedent of treating privacy tools as something to eliminate rather than protect threatens digital freedom broadly.

Has any country successfully blocked VPNs completely?

No country has completely eliminated VPN usage while maintaining internet freedom. China has deployed aggressive blocking via DPI and reportedly achieved 70-80% effectiveness against mainstream VPN services, but tech-savvy users and newer services still slip through. Russia, Turkey, and other countries blocking VPNs report similar partial success with constant arms races against new evasion techniques. Critically, authoritarian countries pursuing VPN blocking don't respect privacy rights and can employ more aggressive measures than democratic nations would accept. European countries have consistently rejected VPN blocking, citing both privacy concerns and technical ineffectiveness.

What's the actual rate of success for age verification systems protecting social media access?

Age verification systems typically have failure rates between 15-40% depending on the method used. Government ID verification requires uploading sensitive documents (privacy risk), credit card verification relies on minors having cards in their names (which many don't), biometric verification has accuracy issues with faces still changing, and parental consent systems depend on parents monitoring appropriately. No method is foolproof, which is why teenagers will likely bypass even strong age verification through VPNs or other workarounds. The system's porousness is part of why blocking VPNs seems necessary from the government's perspective, but addressing the underlying vulnerability in age verification might be more effective than restricting privacy tools.

Are there alternatives to banning social media that actually protect teenagers' mental health?

Yes, multiple evidence-based alternatives exist. Platform regulation through design changes (removing algorithmic recommendations, limiting notifications, banning infinite scroll) makes platforms less addictive without banning access. Better parental tools let parents monitor and control usage without government surveillance infrastructure. Digital literacy education teaches teenagers how algorithms manipulate engagement and encourages healthier relationships with platforms. Increased mental health support services address the actual harms (depression, anxiety) rather than restricting access. Transparency requirements force platforms to publish algorithms and impact assessments. These approaches respect individual autonomy, privacy rights, and parental authority while still protecting vulnerable teenagers.

How does the EU's Digital Services Act relate to France's VPN blocking proposal?

The EU's Digital Services Act (passed in 2023) takes a lighter-touch regulatory approach compared to France's blanket social media ban. The DSA requires transparency, user rights protections, and platform accountability regarding recommendation algorithms and content moderation, rather than banning services outright. This represents the European regulatory consensus before France's social media and potential VPN restrictions. The DSA's approach acknowledges technical enforcement limits and privacy concerns while still achieving protective goals. France's proposal is more aggressive than the EU consensus, which creates tension between national and EU-level regulation.

What would be the economic impact of VPN blocking in France?

VPN blocking would harm France's tech sector competitiveness by driving privacy-focused software companies out of the market, complicating enterprise software access (remote work tools, software development infrastructure), and creating legal uncertainty for businesses relying on VPNs. The infrastructure investment (billions in DPI technology, maintenance, and constant updates against new evasion techniques) generates zero economic value. Meanwhile, the largest tech companies (Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft) benefit from reduced competition and reduced privacy oversight. France's tech sector is already smaller than competitors in Germany and Scandinavia, and VPN blocking would likely disadvantage it further while benefiting only the largest corporations.

Is parental authority being preserved under France's legislation?

This is complicated. Parents retain formal authority to allow or restrict their children's social media usage. However, if France implements nationwide ISP-level VPN blocking, parents can't legally authorize their child's VPN usage for legitimate security reasons (protecting privacy on public Wi-Fi, secure remote access, accessing information in censored regions). The government restriction overrides parental authority in practice. This creates the odd legal situation where a parent could theoretically be liable for their child using a VPN that the parent authorized for security purposes. Most digital rights advocates argue parental authority over children's internet access should be primary, with government enforcement of minimum standards (no illegal content) but broader decisions left to families.

Conclusion: What Happens Next

France is at an inflection point. The social media ban for under-15s is coming in 2025, and the question about VPN restrictions will follow shortly after. The government will likely implement the social media ban, discover teenagers are using VPNs to bypass it in larger numbers than expected, and face pressure to "do something" about VPNs.

That pressure will be real and politically difficult to resist. Parents concerned about their children will support VPN blocking. Tech critics will argue that you can't have a meaningful social media ban if people can easily circumvent it. Lawmakers will feel obligated to make the restriction work.

But the technical reality doesn't bend to political pressure. Blocking VPNs effectively requires surveillance infrastructure that democracies should avoid building. The alternatives (obfuscation, newer VPN protocols, shifting to other privacy tools) mean the enforcement costs keep rising with diminishing returns.

My prediction: France implements the social media ban successfully enough to declare it a win. VPN usage among teenagers increases, but not catastrophically. The political pressure to block VPNs remains significant. France explores blocking but runs into technical and political obstacles. After a period of study, they implement partial blocking (targeting the most popular VPN providers) while accepting that determined teenagers will find workarounds.

Other European countries watch carefully. Some follow France's lead on the social media ban but skip VPN blocking. A few try both. The international precedent gets set over the next 2-3 years.

Meanwhile, tech companies respond by building better obfuscation, faster VPN protocols, and more resilient networks. Privacy advocates push back against surveillance infrastructure. The dialectical tension between government restriction and user privacy continues evolving.

The broader implications extend beyond VPNs and teenagers. This is about what kind of digital future we're building. One where governments can inspect all network traffic for enforcement purposes. One where privacy tools are suspect. One where access to information requires government approval and permission.

Or one where encryption, privacy, and anonymity are foundational rights that even governments protecting children can't simply eliminate.

France's decision about VPNs will tell us which future we're actually building.

Key Takeaways

- France passed a social media ban for under-15s, with lawmakers now evaluating VPN restrictions to prevent teenagers from bypassing the law

- Technical barriers make nationwide VPN blocking extremely difficult, with modern VPN protocols designed to evade detection and constant arms races against new obfuscation techniques

- Blocking VPNs requires deep packet inspection infrastructure that enables surveillance capabilities extending far beyond child protection, raising serious privacy rights concerns

- International precedent shows that even authoritarian countries achieve only 70-80% effectiveness at VPN blocking, with tech-savvy users consistently finding workarounds

- Alternative approaches like platform design regulation, parental tools, and digital literacy education could achieve protection goals without building mass surveillance infrastructure

Related Articles

- License Plate Readers & Privacy: The Norfolk Flock Lawsuit Explained [2025]

- Facial Recognition and Government Surveillance: The Global Entry Revocation Story [2025]

- Windscribe VPN Iran Russia Crackdown: AmneziaWG Solutions [2025]

- Iran's Internet Shutdowns: How Regimes Control Information [2025]

- Major Cybersecurity Threats & Digital Crime This Week [2025]

- Jeffrey Epstein's 'Personal Hacker': Zero-Day Exploits & Cyber Espionage [2025]

![France's VPN Ban for Under-15s: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/france-s-vpn-ban-for-under-15s-what-you-need-to-know-2025/image-1-1770052058389.jpg)