How Big Tech Treats Billion-Dollar Fines Like Pocket Change

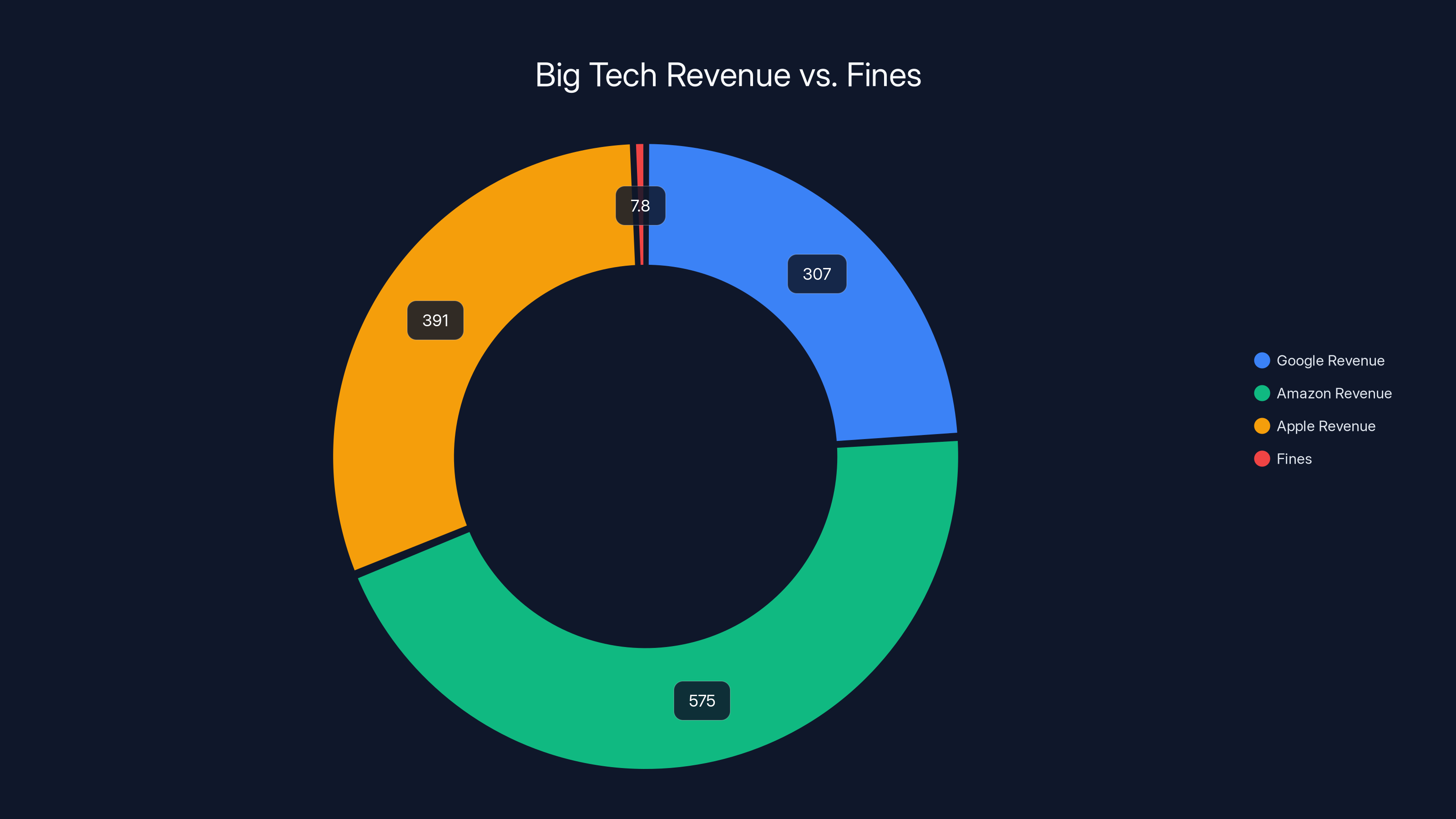

Something genuinely unsettling happened last year, and most people missed it entirely. The tech giants that run half the internet got hit with over $7.8 billion in fines across 2025. That's a staggering number. That's wealth that could fund education programs, infrastructure projects, or legitimate innovation.

But here's where it gets dark.

Proton, the privacy company that actually gives a damn about your data, ran the numbers. Their conclusion? The big three—Google, Amazon, and Apple—could pay off every single one of those fines in less than a month. For context, that's roughly how long it takes to get approval on a mortgage.

Not weeks of belt-tightening. Not quarterly earnings calls about "taking regulatory feedback seriously." One month. Less than 30 days of revenue.

This isn't a story about fines. It's a story about what fines really are: a cost of doing business, so trivial that corporations literally account for them the same way you'd budget for your annual car insurance. Annoying, sure. Consequential? Barely.

The uncomfortable truth is that regulatory fines have become a joke. Not because they're small in absolute terms, but because they're microscopic relative to the companies being fined. When a penalty is less than a rounding error on quarterly earnings, you've failed as a regulator. You've turned punishment into theater.

But the real story goes deeper. This isn't just about money. It's about what these fines represent: privacy violations, anti-competitive behavior, security failures, and systemic abuse of user data. And the system we've built lets companies solve these problems by writing a check.

Let's break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and what it means for everyone whose data these companies are harvesting, selling, and occasionally exposing to bad actors.

The $7.8 Billion Fine Landscape of 2025

When you see "$7.8 billion in fines," your brain tries to contextualize it. You think about what that means. Federal budgets? Government spending? Gross domestic product of smaller countries?

All accurate frameworks. But they're missing the point.

The fines levied against Big Tech in 2025 came from multiple sources. The European Union, famous for actually caring about privacy, issued roughly

The United States? They've been slower to act. The FTC has been investigating Google, Amazon, and Apple for years. Some penalties came through. Others are still grinding through bureaucratic machinery.

Other jurisdictions—UK, Canada, Australia, Singapore—piled on additional penalties for everything from data privacy violations to anti-competitive conduct to security failures.

The number is real. It's impressive. It's also completely meaningless.

Here's the math that should horrify you: Google's annual revenue is approximately

Google's

For comparison, if you earn

But it's worse than that.

Monthly Revenue: The Embarrassing Comparison

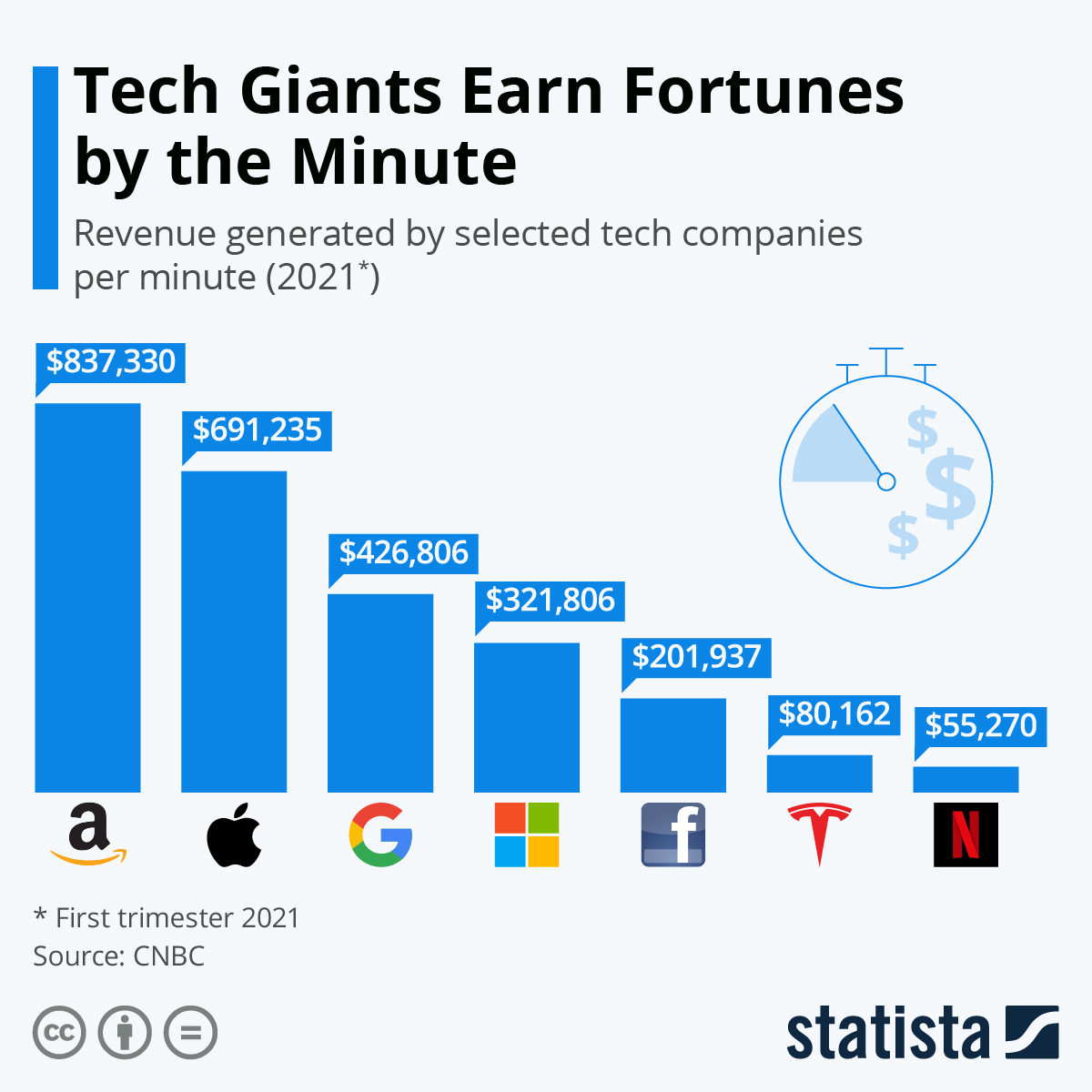

When Proton ran their analysis, they focused on a single metric: how long does it take these companies to earn enough money to pay the fine?

Let's work through this.

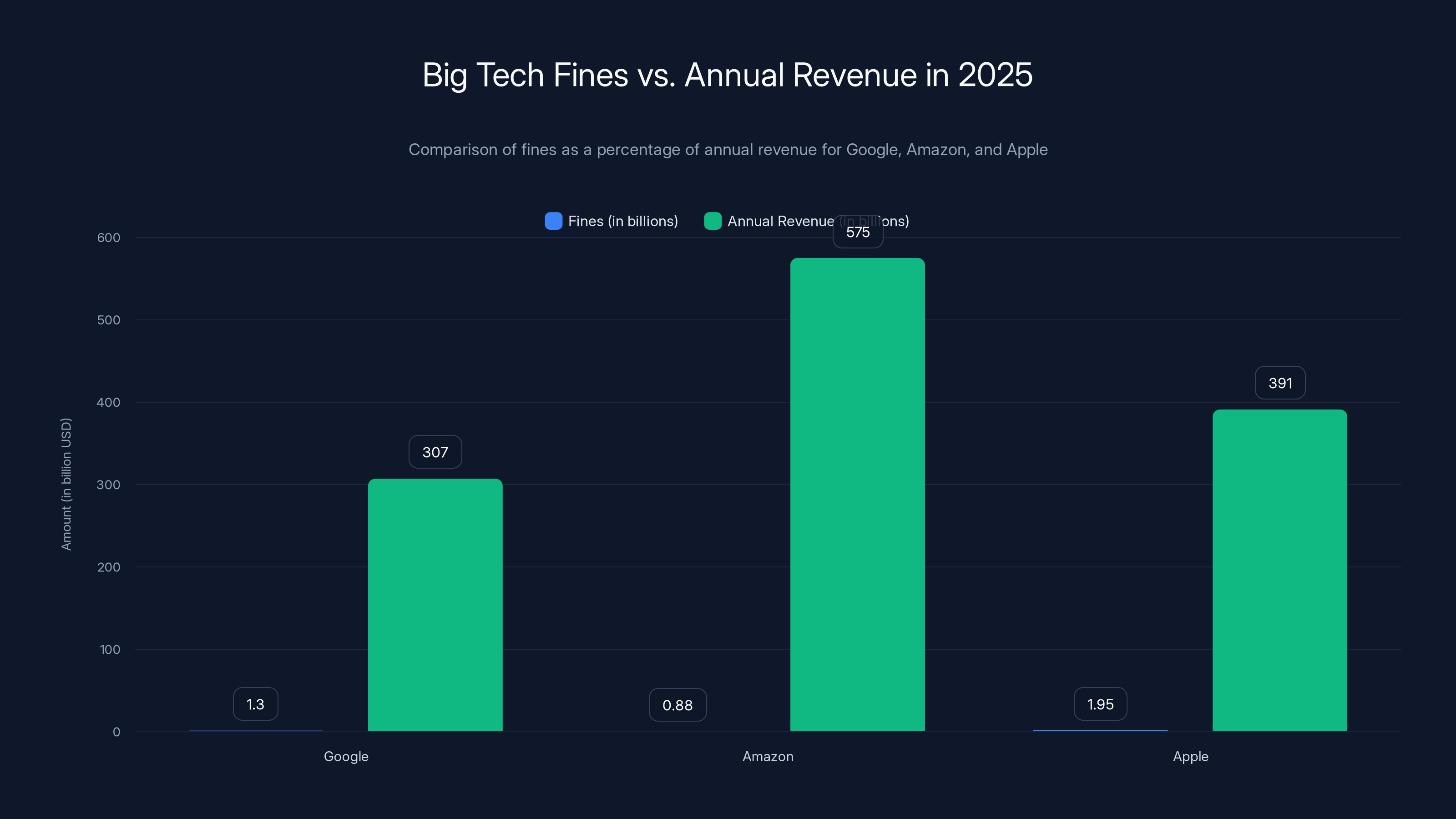

Google's case:

Amazon's case:

Apple's case:

When you add up all fines across all these companies, we're talking about less than one month of combined revenue for this trio. One calendar month. 30 days. The time it takes to watch a decent TV series.

This is the context that regulators don't want you to think about, and that tech companies are betting you won't calculate.

Big Tech's combined annual revenue of over

Why Fines Don't Work as Deterrents Anymore

Let's be honest about what a deterrent actually is.

A deterrent has to hurt. It has to matter. It has to change behavior because the cost of continuing a behavior exceeds the benefit of that behavior.

If I speed on the highway, I might get a ticket. The ticket costs

If a corporation speeds—metaphorically speaking—and the ticket is 0.4% of their monthly revenue, what's changed? The calculation is simple: "The probability of getting caught times the size of the fine is less than the profit we make from violating the rule." So they keep going.

Economists call this the "expected value problem." Corporations have entire departments that run these calculations. They literally get paid to figure out whether breaking regulations is profitable.

Let's look at a concrete example: Google's anti-competitive search practices. The EU fined them over a billion dollars for forcing their products into search results, making it harder for competitors to appear fairly. The question corporations ask is simple: "Did the extra revenue from this practice exceed the fine we might pay?"

The answer appears to be a resounding yes. Google continues similar practices. They've been fined multiple times for the same behavior. If the fines were actually working as deterrents, they'd have stopped already.

The Profit Margin Problem

Here's another angle: profit margins.

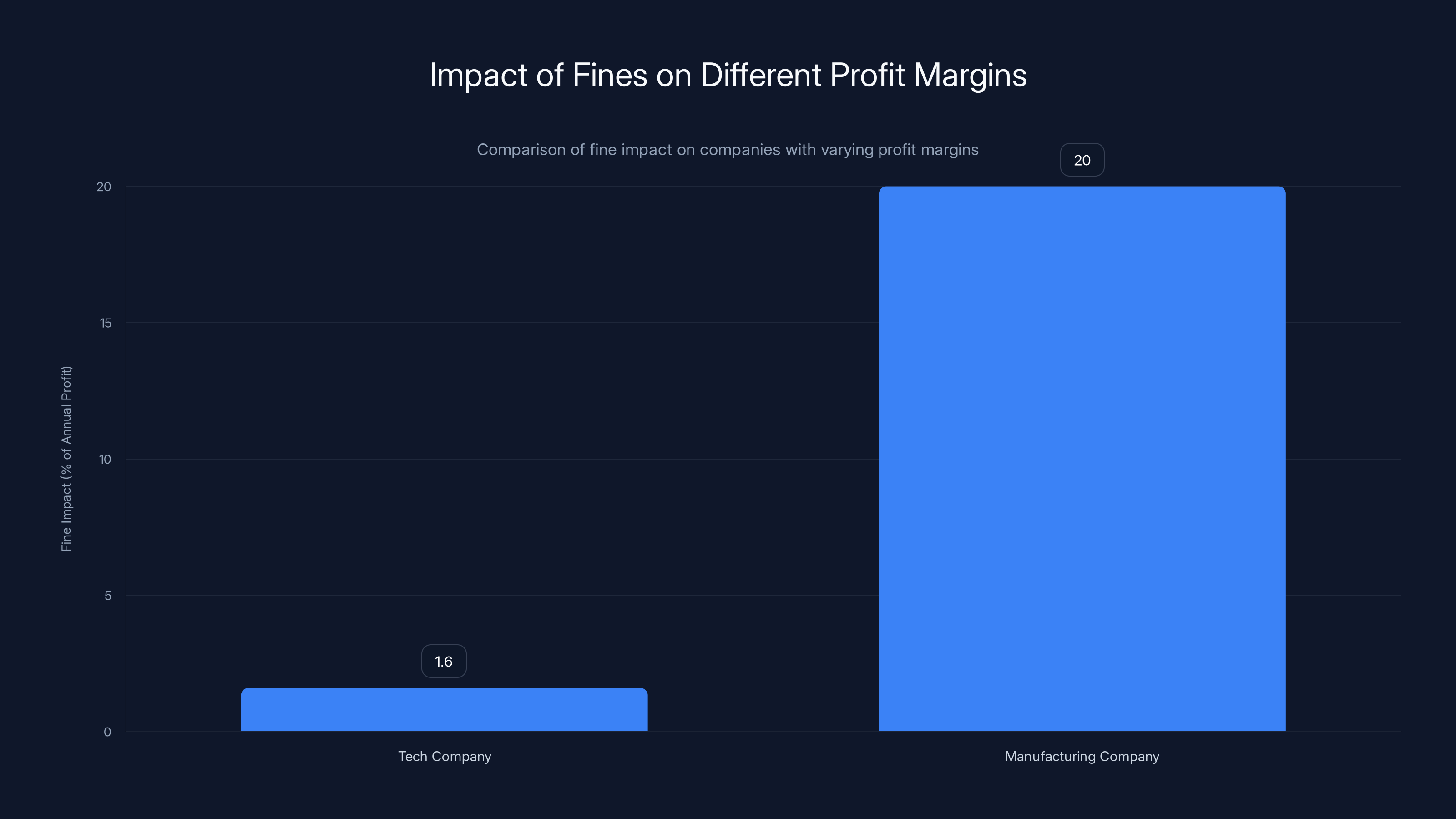

Big Tech companies operate at absolutely obscene profit margins. Google's operating margin is around 26-28% on that

When you have that kind of profit, a $1.3 billion fine is somewhere between a minor inconvenience and a rounding error on your balance sheet.

Compare this to, say, a manufacturing company with 5% profit margins. If they face a billion-dollar fine, it's devastating. It cuts through to real capital they could have reinvested, real employees who might get laid off, real R&D projects that get canceled.

Big Tech? They barely notice.

The fundamental issue is that we've built a regulatory system that assumes fines proportional to revenue will work as deterrents. But when profit margins are that high, you need fines proportional to profit, or even better, to the actual harm caused.

Otherwise, you're just charging a tax for bad behavior. And corporations will gladly pay taxes if the behavior is profitable enough.

In 2025, fines levied against Google, Amazon, and Apple were minor compared to their annual revenues, representing only 0.42%, 0.15%, and 0.5% respectively. Estimated data.

The Privacy Violations Behind the Fines

Let's get specific about what these fines were actually for, because the regulatory categories matter.

A significant portion of Big Tech's 2025 fines came from privacy violations. This is where it gets personal, not just corporate.

Google's privacy issues: The company faces ongoing scrutiny for location tracking. Even when users disable location services, Google continues collecting location data through alternate means. They've been caught tracking users through Google Analytics across websites they don't own. The company also faced criticism for how it handles data sharing with third parties, including political campaigns and law enforcement.

How much did Google profit from this tracking? Nobody knows the exact number. But consider that Google's entire advertising business—the engine that generates 80% of revenue—depends on tracking you. If you turned off tracking entirely, would their profit margins hold? Almost certainly not.

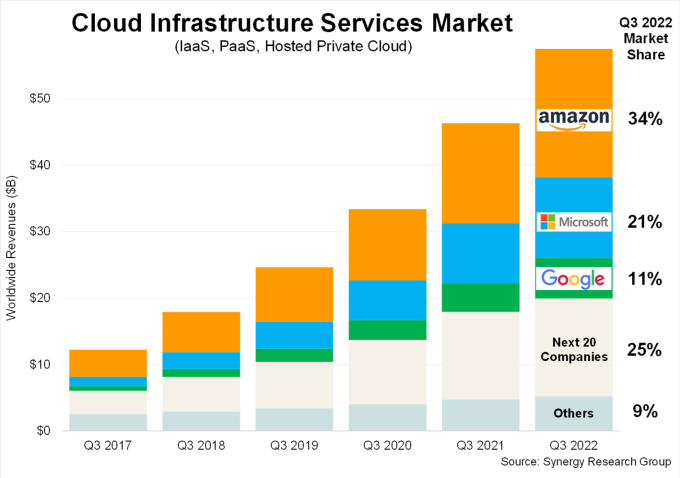

Amazon's privacy and anti-competitive conduct: The company faced fines for allegedly using seller data to compete against those sellers. A marketplace seller would see their product perform well, then Amazon would copy it with their own brand. That's not just anti-competitive, it's using privileged access to data for profit.

Amazon also faced criticism for facial recognition practices through their Rekognition tool, which some jurisdictions wanted to limit or ban.

Apple's anti-competitive behavior: The App Store fine was massive because Apple essentially holds a monopoly on iPhone distribution. They take 30% of every purchase made through their store, prevent developers from linking to cheaper options elsewhere, and use their platform control to promote their own services.

The kicker? This isn't a privacy issue. It's an open question whether users are actually worse off under this arrangement, or if they prefer the curated approach. The fine is more about market structure than user harm. Yet it's the largest one.

Why the EU Gets It (And the US Doesn't)

If you've noticed that most of these big fines are coming from Europe, you're not missing anything.

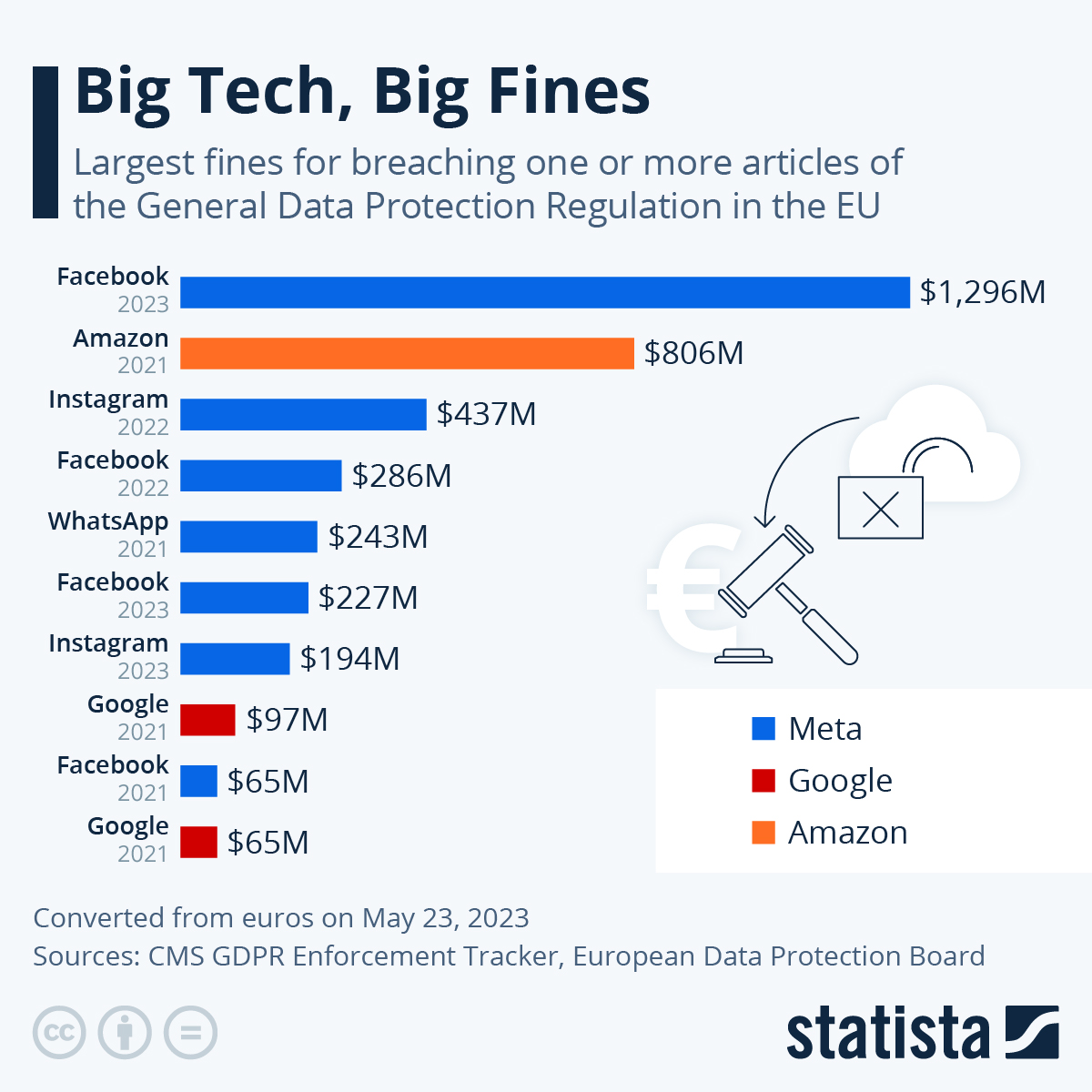

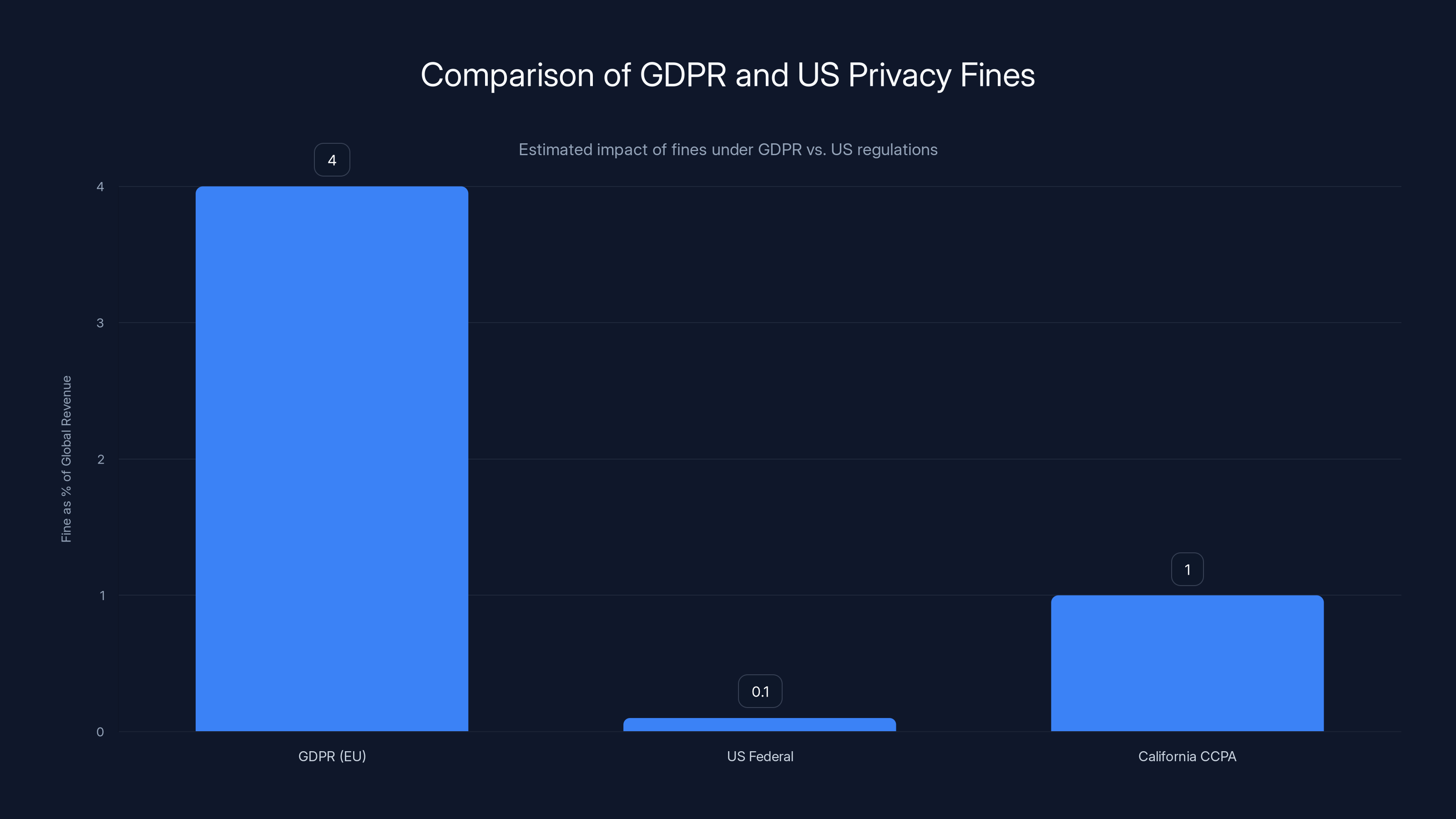

The European Union has actually, genuinely tried to build a regulatory framework that's not theater. The foundation is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force in 2018.

GDPR is imperfect. It's not perfect. But it does something radical: it lets regulators actually fine companies in a way that hurts. Fines under GDPR can reach 4% of global annual revenue for serious violations. For Google, that would be roughly $12 billion.

Do you see the difference? Instead of a fine representing a tiny fraction of monthly revenue, suddenly you're talking about a fine that represents a real percentage of annual profit.

Has GDPR been perfect? No. Enforcement has been inconsistent. But the threat of meaningful financial consequences has at least changed corporate behavior in Europe. Companies investing in privacy infrastructure specifically to comply with GDPR actually built privacy teams. They actually reviewed data practices.

The United States, meanwhile, has no unified privacy regulation. Individual states have taken steps. California's CCPA and the newer CPRA added privacy protections. But there's no federal framework with real teeth.

So what happened? Tech companies headquartered in the US face meaningful fines in Europe, but can largely ignore similar practices in the US market. They've basically regionalized their behavior: privacy theater in Europe, broader data collection in America.

Meanwhile, the FTC has been hamstrung by years of corporate-friendly courts and administrations. The commission's budget is tiny relative to what tech companies spend on legal teams. The fines they do levy are small enough that companies can absorb them.

Fines have a minimal impact on tech companies with high profit margins (1.6% of profit) compared to manufacturing companies (20% of profit). Estimated data.

The Accountability Crisis

Let's zoom out and see this for what it really is: a failure of institutional accountability.

When corporations can commit violations worth billions in consumer harm, face a fine representing a fraction of monthly revenue, and continue the same practices because the math still works out, you don't have a regulatory system. You have a kabuki theater where everyone pretends to care.

Here's how the cycle actually works:

Stage 1: Violation. A company discovers that violating regulations generates profit. Maybe they're illegally tracking users. Maybe they're using anti-competitive practices. Maybe they're not securing user data properly. The profit motive is clear.

Stage 2: Regulatory Action (Slow). Regulators eventually notice. They open investigations. These take years. During this time, the company continues the profitable behavior. The regulatory process is intentionally slow because companies have armies of lawyers designed to delay.

Stage 3: Fine (Tiny). Regulators finally issue a penalty. It's inadequate. Everyone knows it's inadequate. The company pays it from cash reserves and moves on.

Stage 4: Repeat. Nothing changes because nothing had to change. The equation is still: "Benefit from violation > Fine." So companies keep violating.

This cycle has repeated itself dozens of times. Google has been fined for the same anti-competitive search practices multiple times. They haven't stopped. Why would they? They profit more from the violation than they lose in fines.

The only way this changes is if fines become large enough that the equation flips: "Benefit from violation < Fine + reputation damage + operational costs."

We're nowhere near that threshold.

The Real Cost of Privacy Violations

Here's something that never shows up in the regulatory fine calculations: the actual cost to real people.

When Google illegally tracks your location, what's the harm? It's not obvious to most people because harm to privacy is diffuse and delayed.

But the harms are real:

Political manipulation. If companies know your location, your browsing history, your search queries, they can build terrifyingly accurate political profiles. They know which neighborhood you live in. They know your income bracket (inferred from your shopping patterns). They know your medical interests, your sexual orientation, your political leanings. Political campaigns can then target you with information designed to manipulate your vote. This is happening right now.

Discrimination. Insurance companies, employers, and loan officers buy behavioral data. If they know your location patterns, your health interests, your financial struggles, they can discriminate against you at algorithmic scale. Reject your loan application because data shows people in your demographic tend to default. Deny you employment because your browsing history suggests you might be disabled. Charge you more insurance because you visited certain neighborhoods.

Stalking and physical harm. Location data combined with other information enables stalking at scale. Abusive partners track victims. Criminals identify targets. Law enforcement uses this data without warrants.

Psychological manipulation. Companies like Facebook and TikTok deliberately optimize for engagement over wellbeing. They use psychological techniques to make their platforms more addictive. They know this harms mental health, especially in younger users. They do it anyway because engagement drives ad revenue.

None of this gets priced into the fines. Regulators have no methodology for calculating the cost of these harms. So they sort of guess, and their guesses are tiny.

GDPR allows fines up to 4% of global revenue, significantly higher than US federal fines, which are often less than 0.1% of revenue. California's CCPA can impose fines up to 1%, showing regional variance in the US. (Estimated data)

When Will This Actually Change?

Let's talk about the harder question: what would it take to actually fix this?

Option 1: Massively Higher Fines. The EU could double or triple maximum penalties. GDPR already allows 4% of global revenue. The EU could increase it to 10%, 15%, 20%. At that level, fines would actually hurt. Companies would need to change behavior.

But here's the problem: regulators are often appointed by governments, and governments like the tax revenue and jobs that tech companies generate. They're reluctant to go full punitive.

Option 2: Structural Penalties. Instead of fines, regulators could force structural changes. Break up monopolies. Mandate interoperability. Require algorithm transparency. These would be far more consequential than money.

But they'd also face decades of litigation, appeals, and corporate lobbying.

Option 3: Personal Accountability. Fine the executives personally, not the corporation. Imprison them for violations. This would change behavior faster than any corporate fine ever could.

Why? Because executives care about their freedom and wealth in ways corporations don't. They can't absorb a personal fine the way the company absorbs it.

But this is political poison. Wealthy executives have powerful lawyers and political connections.

Option 4: Customer Power. Users could vote with their wallets. Stop using Google. Delete Facebook. Buy iPhones from vendors that respect privacy.

This is theoretically possible. Practically? It's nearly impossible because these services are so integrated into modern life that avoiding them requires significant sacrifices. Plus, the companies have network effects working for them.

So what's actually likely to change? Probably nothing immediate. The system will likely continue as it is until something breaks spectacularly. A massive data breach affecting millions. A corporation-enabled atrocity that forces regulatory action. A political moment where the regulatory environment shifts dramatically.

But those shifts can happen. Public opinion can change. A new regulatory administration can take office with actual teeth. A major scandal can create political pressure.

The Privacy Paradox: Why Users Don't Care Until They Do

There's a weird dynamic at play here called the "privacy paradox."

Surveys consistently show that roughly 80% of people say they care deeply about privacy. They say they're concerned about companies tracking them. They say they value their data security.

But when given the choice between privacy and convenience, they choose convenience almost every time. They don't disable location tracking because Google Maps needs it to work well. They use Gmail because it's free and amazing. They use Facebook because their friends are there.

This creates a situation where users have enormous power but don't exercise it.

But the paradox has limits. Privacy concerns become urgent when they intersect with other values. When people realize companies are selling their data to political campaigns and using it to manipulate them, that hits different. When people realize their intimate health data is being sold to insurers, that hits different.

We might be approaching that moment. Trust in tech companies is declining. Privacy concerns are rising. There's slowly building pressure for regulatory change.

If that pressure builds enough, we might finally see fines that actually work as deterrents.

Liability reform is estimated to be the most effective approach with a rating of 9, as it directly impacts executive behavior. Mandatory audits also score high, promoting transparency.

Alternative Approaches to Corporate Accountability

Before we conclude, let's explore some less obvious approaches that might actually work.

Reputation Penalties. Regulators could require companies to publicly disclose violations and fines in prominent places. Every time you use Google, you see: "Google was fined

The embarrassment and reputational damage might matter more than the fine itself.

Mandatory Audits. Instead of or in addition to fines, require independent audits of corporate privacy and security practices. Make the results public. This creates transparency without needing to calculate complex penalty amounts.

Liability Reform. Make executives personally liable for violations. Not criminally necessarily, but civilly. If a privacy breach happens on your watch, you personally face lawsuits. This changes incentives at the top.

Customer Compensation. Instead of money going to governments, fine customers directly. Everyone whose data was misused gets a payment. This makes the cost obvious and might motivate action.

Interoperability Requirements. If companies were forced to let users port their data, switch platforms easily, and use competitors, market power would decrease automatically. No fine needed. The market would handle it.

Looking Forward: Will 2026 Be Different?

We're now into 2026, looking back at 2025's $7.8 billion in fines.

Has anything changed? The honest answer is: not really.

Google's advertising practices continue. Apple's App Store policies remain essentially unchanged. Amazon's marketplace practices persist.

There are some signs of movement, though:

- The EU is preparing more aggressive enforcement of its Digital Markets Act

- Some US states are finally considering privacy legislation

- Tech worker organizing is increasing pressure on companies from the inside

- Public opinion is slowly shifting against the tech giants

But these are tiny movements. They're not close to shifting the fundamental equation.

What would actually matter is a moment where the cost of violations genuinely exceeds the benefit. We're not there yet.

Until that happens, expect more fines. Expect more regulatory theater. Expect companies to calculate whether violations are profitable, conclude they are, and continue.

And expect those companies to pay off those fines in less than a month.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Corporate Power

There's a broader issue lurking underneath all of this.

Big Tech isn't just too rich to be deterred by current fines. It's also too powerful to be regulated effectively.

These companies employ millions. They generate billions in tax revenue. They're intricately woven into the global economy. They have political influence that rivals governments in some cases.

When you have that much power, regulatory capture happens almost naturally. Regulators become sympathetic to your problems. Governments become reluctant to punish you too hard. The system that's supposed to hold you accountable gets undermined from within.

This isn't a conspiracy. It's a consequence of size and power and integration into the political system.

The only real solution is to prevent companies from getting this powerful in the first place. That means antitrust enforcement. That means breaking up monopolies. That means seriously challenging mergers that consolidate power further.

But antitrust enforcement has been weak for decades. We allowed companies to grow enormous. Now we're stuck with enormous companies that are too powerful to regulate effectively.

What This Means for Everyday Users

Okay, so Big Tech can pay its fines in a month. Your data is being tracked, sold, and used in ways that harm you. Regulators are toothless. What does this actually mean for you?

First, the uncomfortable reality: you're a commodity. Your attention, your data, your behavioral patterns—they're products being sold to advertisers, political campaigns, and data brokers.

Second, this isn't going to fix itself immediately. Regulatory change moves slowly. Corporate behavior changes even more slowly.

Third, you're not completely powerless. You can:

- Use privacy-focused tools when they're practical. VPN services, encrypted messaging, privacy-focused search engines. They won't solve the problem, but they help.

- Support regulatory changes by voting and contacting representatives.

- Use services that have genuine privacy commitments. Some smaller companies actually care.

- Understand that convenience comes with costs. Free email, free social media—they're not free. You're paying with your data.

But be realistic about what this accomplishes. Individual action is valuable for reducing your personal exposure. It's not going to change Big Tech's behavior.

That requires systemic change. And systemic change requires political will that doesn't currently exist.

The Path Forward

If we actually wanted to fix this, here's what would need to happen:

Short term: Increase fines to meaningful levels. At minimum, 10% of global revenue for serious violations. That would make Big Tech actually calculate differently.

Medium term: Pass federal privacy legislation with teeth. The EU's GDPR proved it's possible. The US needs its own version, ideally even stronger.

Long term: Address market concentration through antitrust enforcement. Break up companies that are too powerful. Prevent mergers that consolidate power further.

None of this is happening right now. So expect more of the same: fines that don't sting, violations that continue, corporate profit that remains obscene.

But pressure can build. Public opinion can shift. A scandal can trigger action. These things have happened before.

Until they do, Big Tech will keep treating multi-billion-dollar fines like a rounding error. And we'll all keep paying the cost in ways we don't fully understand.

FAQ

How much money does Big Tech make relative to the $7.8 billion in fines?

Big Tech's annual revenue is staggering. Google makes roughly

Why can't regulators impose larger fines?

Regulators technically have authority to impose larger penalties. The European Union's GDPR allows fines up to 4% of global annual revenue, which for Google would mean penalties reaching $12 billion or more. However, there's political reluctance to go full punitive because tech companies generate significant tax revenue, employment, and economic value. Additionally, there's often a revolving door where regulators come from or go to the industry they regulate, creating sympathetic relationships. The US has no unified federal privacy law like GDPR, which means American regulators are even more constrained in what they can do.

What does Big Tech actually do with user data?

Companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple collect enormous amounts of data about users: location history, browsing behavior, search queries, purchase patterns, health interests, and demographic information. This data is used to build detailed behavioral profiles and sold to advertisers who use it to target marketing. Political campaigns also buy access to this data to target voters with specific messaging. Employers and financial institutions sometimes purchase behavioral data to make hiring and lending decisions. In some cases, this data enables discrimination, as algorithms trained on biased historical data can deny opportunities to certain groups.

Are there any tech companies that actually care about privacy?

Yes, but they're smaller and less dominant than Big Tech. Companies like Proton explicitly build privacy into their core business model and generate revenue from subscription fees rather than ad targeting. Signal offers encrypted messaging and funding through donations. DuckDuckGo is a search engine that doesn't track users. These companies typically have fewer resources, smaller user bases, and less convenient features than Big Tech alternatives. But they demonstrate that privacy-respecting business models are possible, even if they haven't achieved mainstream adoption.

What would actually change corporate behavior?

The core issue is profit incentives. Companies will violate regulations if the profit from violation exceeds the fine they might pay. To change this, you need fines large enough that violating becomes unprofitable. This likely requires fines representing 10-20% of annual profit for serious violations, not 0.4%. Alternatively, structural penalties like forced interoperability, mandatory algorithm audits, or executive personal liability could work. Antitrust enforcement that breaks up monopolies would reduce corporate power at the source. But all these approaches face political opposition from companies with vast lobbying resources.

Is my data actually harming me right now?

Yes, in most cases. Data collection enables targeted advertising that manipulates your behavior and preferences. Location tracking can enable stalking or discrimination. Health data can be used against you in insurance or employment decisions. Political targeting using your data can manipulate your voting behavior. Financial data can be used to deny you credit or charge you higher rates. Most harms are invisible because they happen at algorithmic scale and affect you through small changes in prices, loan approvals, job opportunities, and information you see online. You don't notice them individually, but collectively they affect your opportunities and freedom.

What can I do to protect my privacy?

Individual actions help reduce your exposure but won't solve the systemic problem. You can use VPN services, encrypted messaging apps, and privacy-focused search engines. You can disable location tracking where possible, though this limits functionality. You can use browsers with better privacy protections. You can limit social media usage. You can support political candidates and policies that prioritize privacy. You can vote with your wallet by preferring privacy-respecting services even if they're less convenient. But be realistic: the system is designed to collect data, and avoiding that entirely in modern life is nearly impossible. Real change requires regulatory and structural solutions at the political level.

When will Big Tech face real consequences for privacy violations?

This is likely to be a slow process. Change happens when political will shifts, usually triggered by public opinion shifting or a major scandal. We're seeing slow movement: increased regulatory activity in the EU, some US states passing privacy laws, growing public skepticism of tech companies, and increasing unionization efforts by tech workers. But we're nowhere near a critical moment where consequences would be severe. Unless there's a massive data breach affecting hundreds of millions, a corporation-enabled atrocity, or a significant political shift in government, expect the current pattern of insufficient fines and minimal behavior change to continue for several more years.

How does this compare to other industries?

The difference is striking. In finance, major violations can result in individual executives facing criminal charges. In pharmaceuticals, fines must be carefully calibrated because the industry's profit margins are lower. In environmental protection, fines sometimes do force behavior change because the damage is measurable and visible. Tech companies are unique in their profit margins, their political power, and the invisibility of harm they cause. Their scale and profitability means conventional fines simply don't work. Most other industries have learned through decades of regulation what Big Tech has barely begun to experience: meaningful enforcement.

The Bottom Line

Big Tech's $7.8 billion in 2025 fines were meaningful as a political statement. They demonstrated that even the most powerful companies aren't completely above the law.

But they were meaningless as deterrents. Companies that can pay off their annual fines in a few weeks of revenue have no reason to change behavior. The calculation remains profitable. The violations continue.

This isn't a secret. Regulators know it. Companies know it. The public is slowly figuring it out.

Change will come when one of three things happens: fines become large enough that they actually hurt, structural reforms break up monopolies, or political will finally shifts toward real enforcement.

None of those things are happening yet. So expect more fines. Expect more regulatory theater. Expect more corporate behavior that violates the spirit of privacy regulations while technically complying with letter-of-law requirements.

But also expect growing pressure for change. The paradox is that Big Tech's arrogance is creating the conditions for its own backlash. When people realize how much they're being tracked, manipulated, and harmed, attitudes shift.

That shift hasn't reached critical mass yet. But it's building. And when it does, Big Tech's comfortable relationship with regulatory fines will end.

Until then, they'll keep paying bills that feel like pocket change and continuing exactly what they were doing before.

Key Takeaways

- Big Tech paid off over 1.2+ trillion annually

- Current regulatory fines represent 0.15-0.5% of annual revenue, making them too small to function as deterrents against profitable violations

- EU's GDPR allows fines up to 4% of global revenue but remains inconsistently enforced; US lacks unified privacy regulation entirely

- Corporate profit margins (25-28% for Big Tech vs 5% for traditional industries) mean fines that devastate normal companies barely register in tech balance sheets

- The regulatory system fails because it prices violations in money but profits come from specific user harms—political manipulation, data discrimination, and behavioral tracking—that never get calculated into fines

Related Articles

- Google's $68M Voice Assistant Privacy Settlement [2025]

- Pornhub's UK Shutdown: Age Verification Laws, Tech Giants, and Digital Censorship [2025]

- Iran's Digital Isolation: Why VPNs May Not Survive This Crackdown [2025]

- Valve's $900M Steam Monopoly Lawsuit Explained [2025]

- Samsung's New Privacy Screen Feature: Blocking Shoulder Surfers [2025]

- Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation, Privacy & Free Speech [2025]

![Big Tech's $7.8B Fine Problem: How Much They Actually Care [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/big-tech-s-7-8b-fine-problem-how-much-they-actually-care-202/image-1-1769622402972.jpg)