Facial Recognition and Government Surveillance: The Global Entry Revocation Story [2025]

It's 2026, and a 56-year-old Target Corporation director from Minnesota got pulled over while following a suspected federal enforcement vehicle. Three days later, her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check benefits vanished. The reason given? A vague violation of "customs, immigration, or agriculture regulations." The real story behind her revocation reveals something far more unsettling: federal agents are using facial recognition technology to identify and potentially retaliate against protesters, and they're doing it with minimal oversight, unclear guidelines, and no meaningful due process for those accused.

This isn't hypothetical anymore. This is happening right now.

What makes this case so significant isn't just the individual impact, though that matters. It's what it reveals about the intersection of surveillance technology, government power, and your rights at the border. If you've got Global Entry, TSA Pre Check, or you travel internationally, this story should concern you. Even if you don't, understanding how facial recognition is being deployed in law enforcement sets the stage for broader debates about privacy, civil liberties, and the government's ability to punish people for legally protected activities.

Let's dig into what happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about the future of border security technology.

TL; DR

- Nicole Cleland observed ICE agents and was confronted by a federal agent who told her they used facial recognition to identify her by name, as reported by Bloomberg.

- Her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check were revoked three days later with no clear explanation or appeal process, according to The Washington Post.

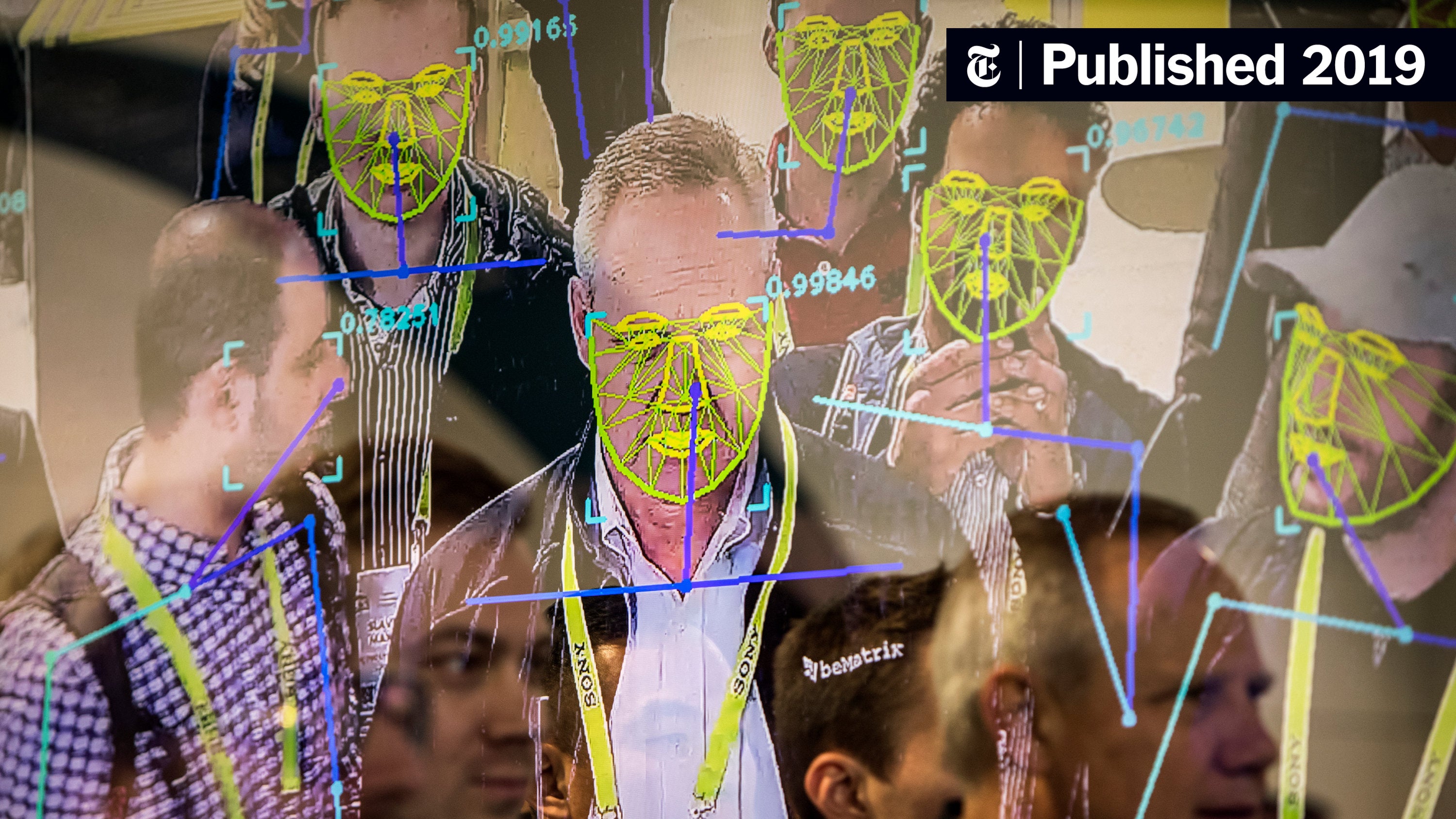

- Facial recognition is being used extensively by CBP and ICE, including during immigration enforcement and to identify protesters, as noted by The New York Times.

- There's no public transparency about how these technologies work, what data they retain, or how mistakes get corrected, as highlighted by the ACLU.

- Legal observers and peaceful protesters are reporting similar incidents, raising questions about retaliation and due process, as discussed by MinnPost.

- The broader implications extend far beyond one woman's revocation, affecting how government can use surveillance against lawful activities, as explored by 404 Media.

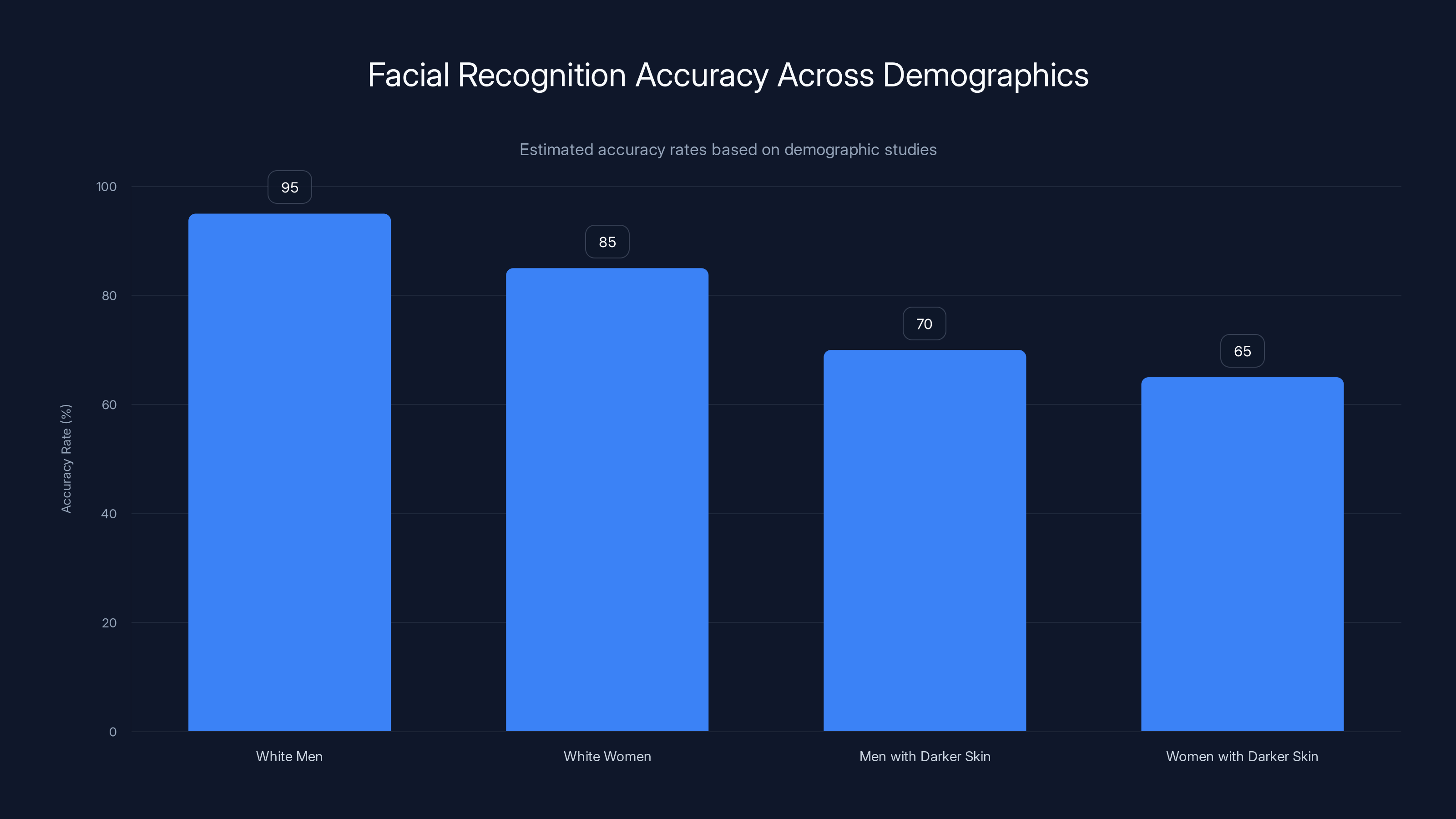

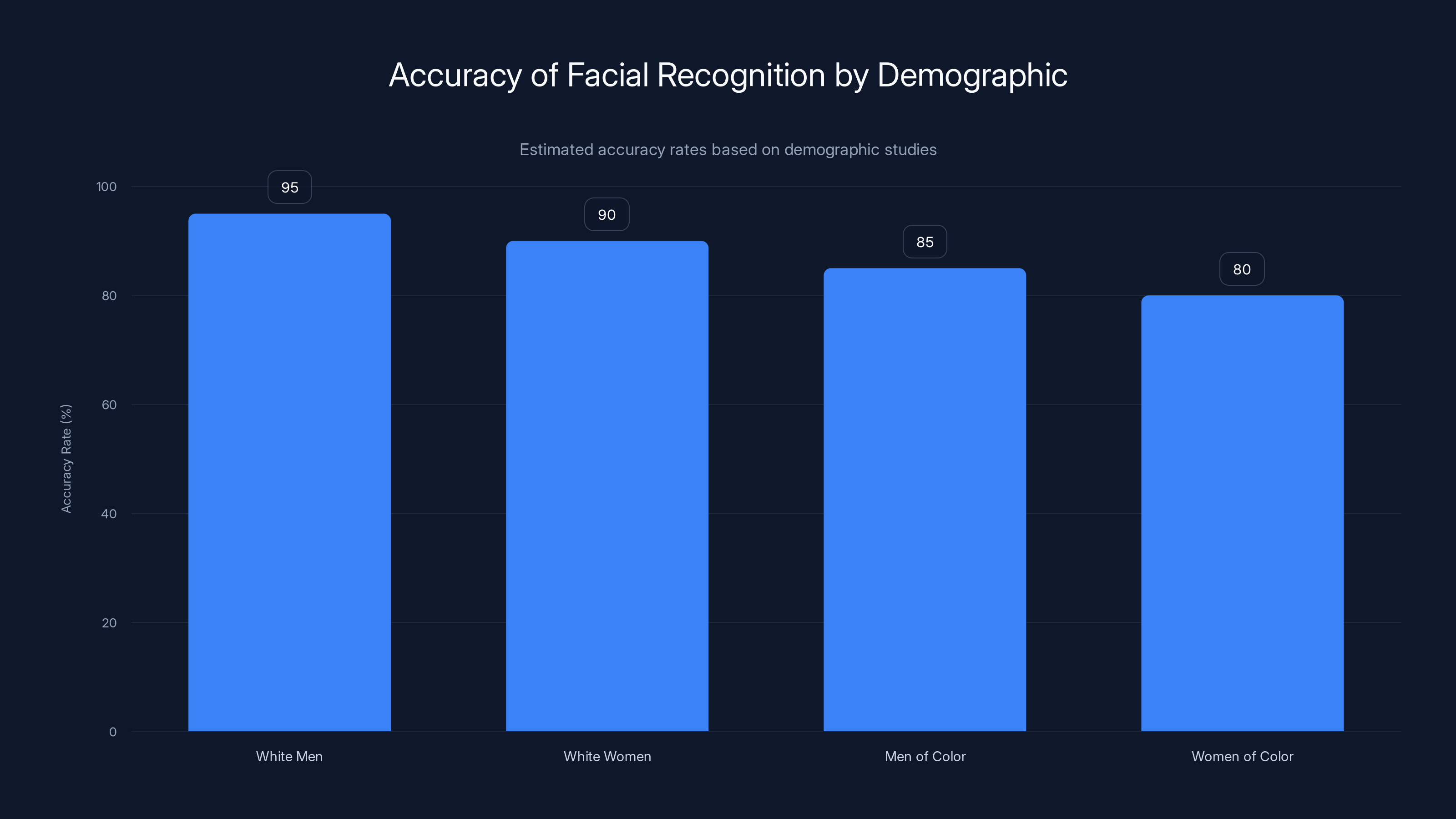

Facial recognition systems show higher accuracy for white men, with significantly lower accuracy for women and individuals with darker skin tones. (Estimated data)

What Actually Happened: The January 10 Incident

On the morning of January 10, Nicole Cleland was doing what she does regularly. She volunteers with a group that tracks potential Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) vehicles in her Richfield, Minnesota neighborhood. This isn't fringe activism. Legal observers have a long history in the United States, operating in a recognized (if sometimes contentious) capacity to document law enforcement actions.

Cleland observed what she believed was a federal enforcement vehicle, a white Dodge Ram, and followed it from a safe distance. Her intention was straightforward: gather information about enforcement activity in her community. She wasn't blocking traffic. She wasn't trespassing. She wasn't violating any laws that she can identify.

As she followed the vehicle, several things happened in quick succession. The Dodge Ram stopped. Additional federal vehicles appeared. Her path forward was blocked. An agent exited a vehicle and approached her car.

What came next is what matters most for this story. The agent addressed Cleland by her full name. Then he told her something that should alarm anyone who cares about privacy: they had used facial recognition technology to identify her. He told her his body camera was recording. He informed her he worked for border patrol and was wearing full camouflage fatigues. He said she was impeding their work, gave her a verbal warning, and told her if she impeded again, she would be arrested.

The exchange lasted only moments. Neither Cleland nor the agent escalated the situation further. They drove off in opposite directions. From a practical standpoint, it was a brief interaction that Cleland thought was over.

But it wasn't.

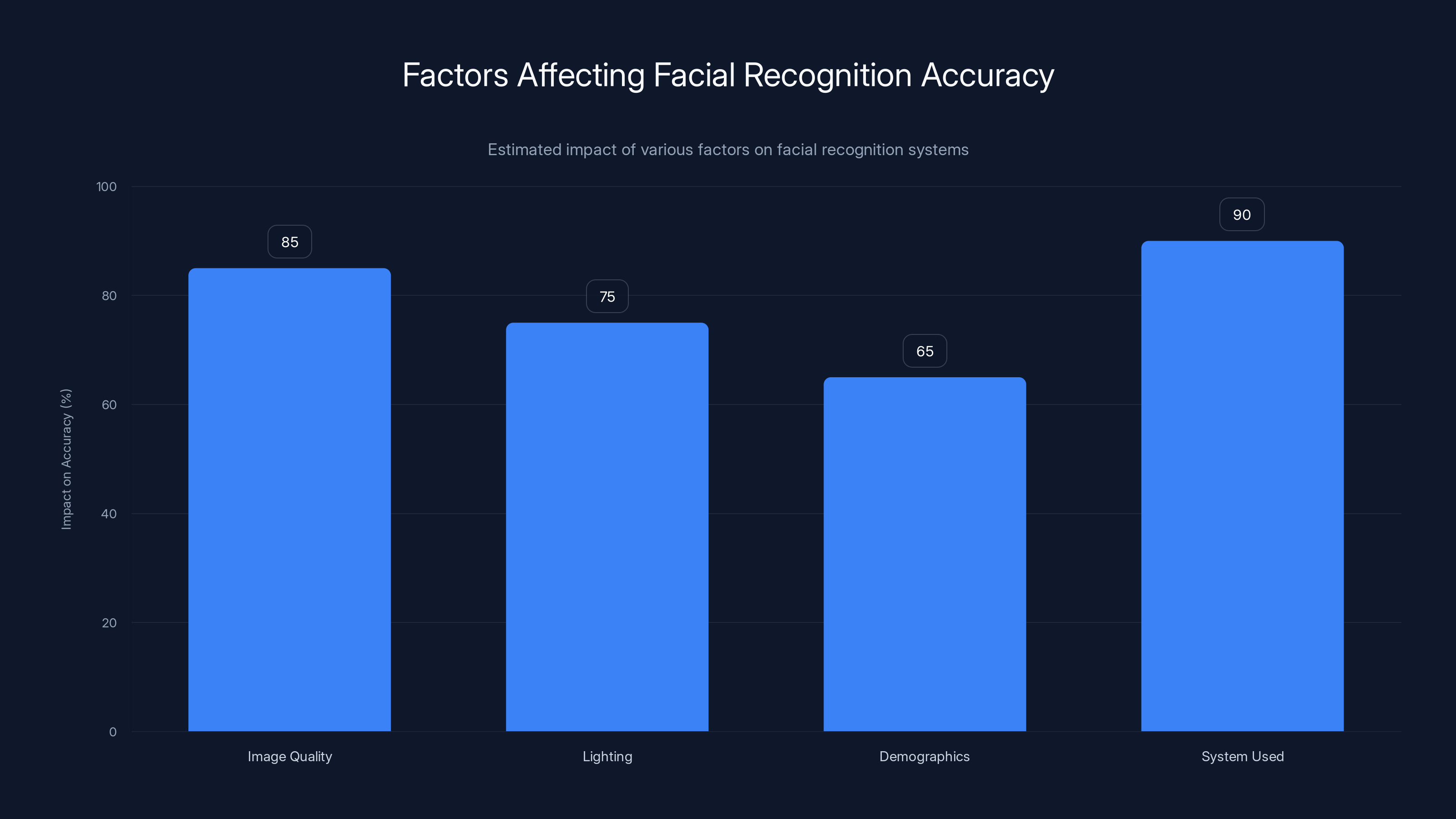

Facial recognition accuracy is significantly influenced by image quality, lighting conditions, demographics, and the specific system used. Estimated data.

The Revocation: Three Days Later

Three days after that encounter on January 10, Cleland received an email notification from the Global Entry program. Her status had been revoked. Both her Global Entry benefits and her TSA Pre Check privileges, which she'd held without incident since 2014, were suddenly gone.

When she logged into the Global Entry website, the notification letter offered vague reasoning. The only explanation that made sense to her was this phrase: "The applicant has been found in violation of any customs, immigration, or agriculture regulations, procedures, or laws in any country."

But here's the problem. Cleland was never detained. She was never arrested. She was never charged with anything. A verbal warning from a border patrol agent during a brief roadside encounter doesn't constitute being "found in violation" of customs or immigration law. Yet the government used this undefined violation as the basis for revoking her trusted traveler status.

The timing is crucial. Only three days had passed between her encounter with the agent and the revocation. That's not a coincidence. That's a pattern.

Cleland is one of at least seven American citizens told by ICE agents this month that they were being monitored with facial recognition technology. She's also far from the first person to report that her Global Entry status was revoked after being identified and confronted by federal agents during immigration enforcement activities or protests.

The Technology: How Facial Recognition Works at the Border

Facial recognition technology is becoming standard operating procedure for federal agencies. This isn't a fringe tool anymore. It's integrated into border security, passport control, and immigration enforcement across the United States.

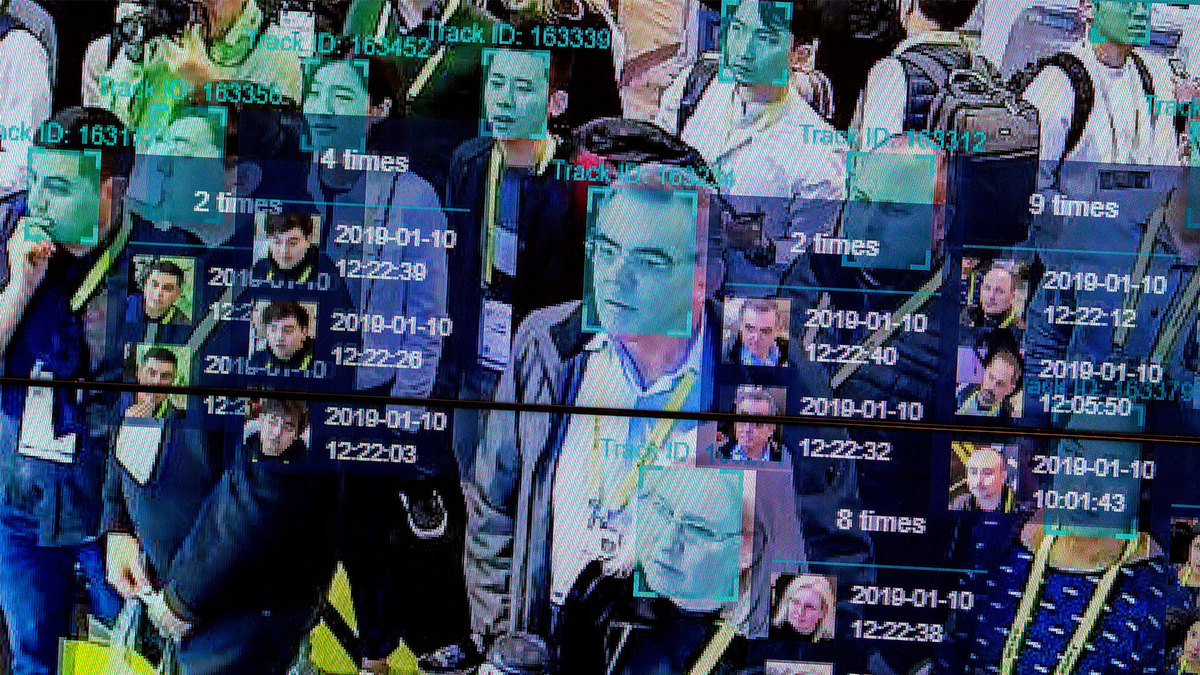

The technology works by comparing facial features captured in real-time against large databases of known faces. The government has access to multiple data sources: passport photos, driver's license images, mugshots from prior arrests, and photos from state DMV databases. When a law enforcement agent scans your face, they're running it against these massive databases, often without your knowledge or consent.

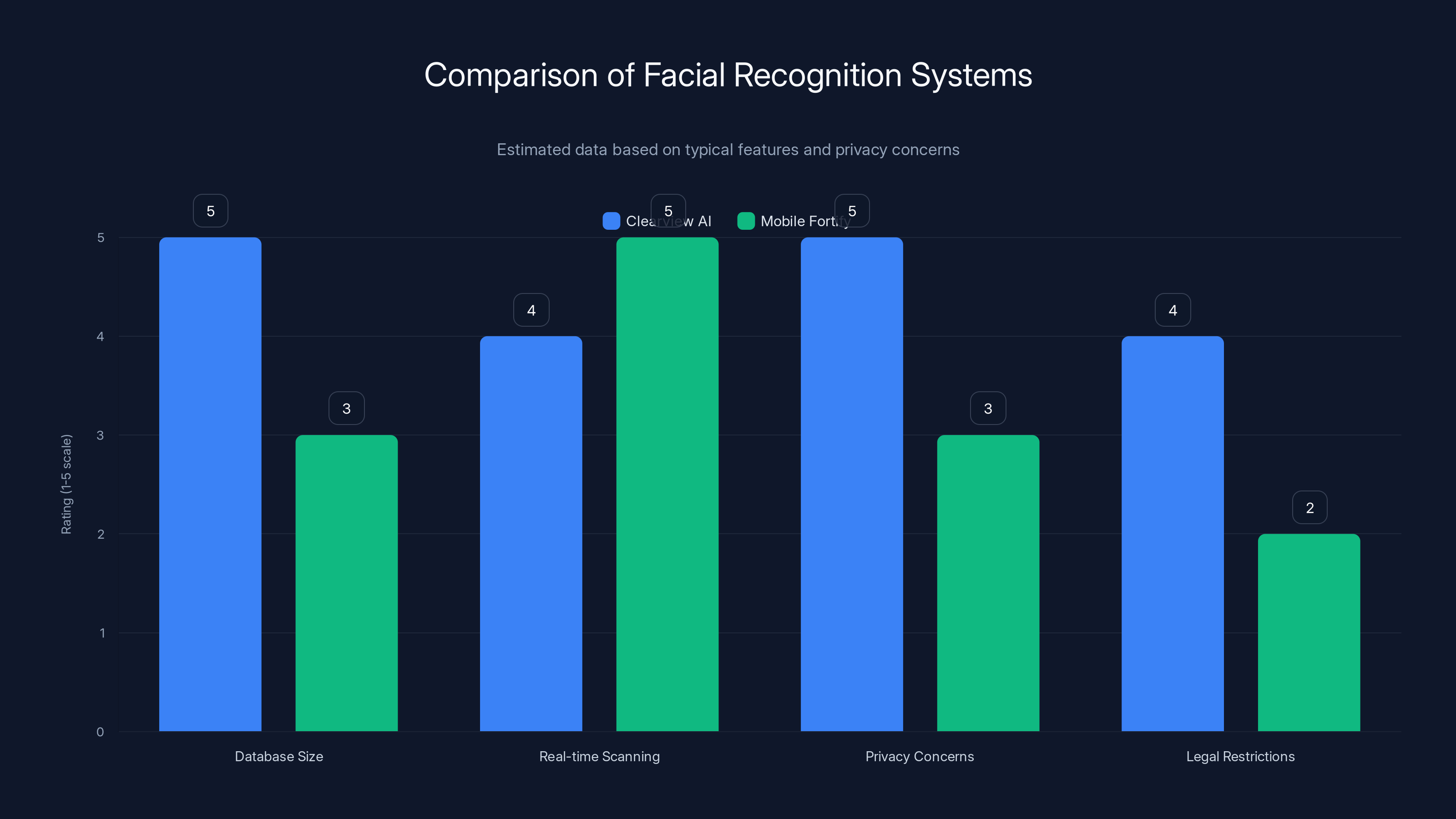

Federal agents are using facial recognition technology from companies like Clearview AI and applications like Mobile Fortify to identify both citizens and non-citizens. The stated purpose is to verify citizenship and identify individuals of interest. But the actual application extends far beyond simple identification.

What makes this technology particularly concerning is the absence of public transparency. How accurate are these systems? The answer depends on the demographic. Research shows that facial recognition systems are significantly more accurate for white men than for women and people of color. False positive rates vary wildly. Misidentifications happen. But there's no requirement for government agencies to disclose error rates, audit results, or appeals processes when they get it wrong.

When an agent tells you they've used facial recognition to identify you by name, they're demonstrating that your face has been captured, analyzed, and cross-referenced against a database. This happens without a warrant in many cases. It happens without your explicit consent. And if you want to know whether you're in one of these databases or challenge the accuracy of the identification, you have limited recourse.

The vast majority of Global Entry's 14 million members remain active, with only a small number experiencing revocation, as highlighted by Cleland's case. (Estimated data)

Global Entry and TSA Pre Check: How They're Used in Immigration Enforcement

Global Entry and TSA Pre Check aren't just convenience programs. They're tied to your trusted traveler status, which federal agencies can revoke at any time. But here's the thing most people don't understand: revocation of these programs is often used as a tool for immigration enforcement or, according to complaints in recent cases, as retaliation against people who engage in lawful protest or observation of federal agents.

Global Entry is administered by U. S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and allows expedited processing for international travelers. TSA Pre Check, administered by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), allows expedited airport security screening. Both programs require background checks and vetting. Both programs can be revoked if the government determines you're a security risk or have violated relevant laws.

The problem is the vagueness. The rules allow revocation if someone is "found in violation" of customs, immigration, or agriculture regulations. But what does that mean exactly? Does a verbal warning from an agent constitute being "found in violation"? Does observing federal agents and taking photographs? Does exercising your First Amendment rights to protest government policies?

The government isn't required to provide detailed explanations for revocations. You don't get a hearing. You don't get to present evidence. You get an email notification. You lose access to benefits you paid for. You have limited appeals processes, and the appeals are often just as opaque as the original decision.

This is where the Cleland case becomes instructive. Her revocation came immediately after being identified and confronted by a border patrol agent. The timing and sequence suggest potential retaliation. But the government doesn't have to prove intent. The revocation stands.

Facial Recognition and Protest Activity: A Growing Pattern

Cleland's situation isn't isolated. Federal agents have increasingly used facial recognition to identify people engaged in lawful protest, observation, and documentation of government enforcement activities. This represents a significant escalation in surveillance capabilities applied to protected speech and assembly.

Legal observers operate in a gray space. They're not law enforcement. They're civilians who attend protests, ICE raids, and enforcement actions to document what happens. They write down what they see, take photographs, record videos, and submit reports to civil rights organizations. This is legally protected activity. Courts have repeatedly affirmed that people have the right to observe and document police and federal agent conduct in public spaces.

But what happens when the government can identify you by face before you even realize you're being recorded? What happens when they use that identification to revoke your travel benefits, flag your accounts, or subject you to additional scrutiny?

Federal agents have told multiple people that facial recognition was used to identify them. Some were legal observers. Some were peaceful protesters. Some were simply documenting enforcement activity in their neighborhoods. In each case, the identification happened quickly and without prior notice. In several cases, the identification was followed by revocation of travel benefits or escalated federal attention.

This creates a chilling effect. If people know they might be identified by facial recognition and potentially face consequences like loss of Global Entry or enhanced scrutiny at the border, they're less likely to exercise their rights to observe, document, and protest. That's the real danger here.

Facial recognition systems show higher accuracy for white men compared to women and people of color. Estimated data based on demographic studies.

Due Process and Appeals: The Missing Guardrails

One of the most troubling aspects of Cleland's situation is the complete absence of due process. She was never given advance notice that being identified by facial recognition and confronted by an agent might result in revocation of her travel benefits. She had no opportunity to respond before the revocation was implemented. When she received notification, she was given vague reasons with no opportunity for a meaningful hearing.

This violates basic principles of due process. Before the government deprives you of a benefit, there's supposed to be notice, an opportunity to be heard, and a fair decision maker. But with Global Entry and TSA Pre Check, none of that really exists in a meaningful way.

The appeals process for revoked Global Entry or TSA Pre Check status is limited. You can submit a request for reconsideration, but the government doesn't have to explain its decision in detail. You don't get to cross-examine agents. You don't get to challenge the accuracy of facial recognition identifications. You don't get to present evidence that the identification was wrong or that your conduct was lawful.

Cleland described her situation clearly in her court declaration: "I am concerned that the revocation was the result of me following and observing the agents. This is intimidation and retaliation. I was following Legal Observer laws. I was within my rights to be doing what I was doing."

Her concern is justified. The rapid revocation after a facial recognition identification, combined with the government's ability to revoke benefits with minimal explanation, creates a system where federal agents can effectively punish lawful conduct without meaningful oversight or appeal.

The legal challenge to this practice is ongoing. Multiple lawsuits have been filed by people claiming that Global Entry and TSA Pre Check revocations constitute retaliation for protected First Amendment activity. These cases are important because they're forcing courts to confront questions about whether the government can use administrative tools like trusted traveler programs as a mechanism for punishing or chilling protected speech.

The Broader Implications for Privacy and Government Power

What's happening at the border and in immigration enforcement doesn't stay contained to those specific areas. Surveillance technologies and practices adopted by one agency spread to others. Tools built for border security become tools for general law enforcement. Facial recognition systems built to identify immigrants become systems that identify protesters, activists, and ordinary citizens.

The precedent being set here matters enormously. If federal agents can use facial recognition to identify someone during a lawful activity and then revoke their travel benefits without meaningful due process, what's to stop them from using facial recognition to track people in other contexts? What's to stop them from using it at airports, train stations, or public spaces more broadly?

Facial recognition technology is becoming ubiquitous. Private companies are deploying it. Local police departments are using it. Federal agencies are expanding its application. But the legal framework governing its use is fragmented and inadequate. There's no comprehensive federal privacy law. There are no uniform standards for accuracy, data retention, or audit trails. There are no clear restrictions on how law enforcement can use the technology.

This creates a situation where government power is expanding without corresponding legal protections. Citizens can be identified without their knowledge. Data can be retained indefinitely. Mistakes can be made without meaningful recourse. And now we're seeing that identification can result in loss of benefits with minimal due process.

The implications extend to your everyday life. If you have a Global Entry or TSA Pre Check, you paid for a benefit that can now be revoked based on conduct that isn't clearly illegal and without a meaningful opportunity to defend yourself. If you plan to travel internationally, your ability to move across borders could be affected by government decisions made opaquely and with minimal transparency.

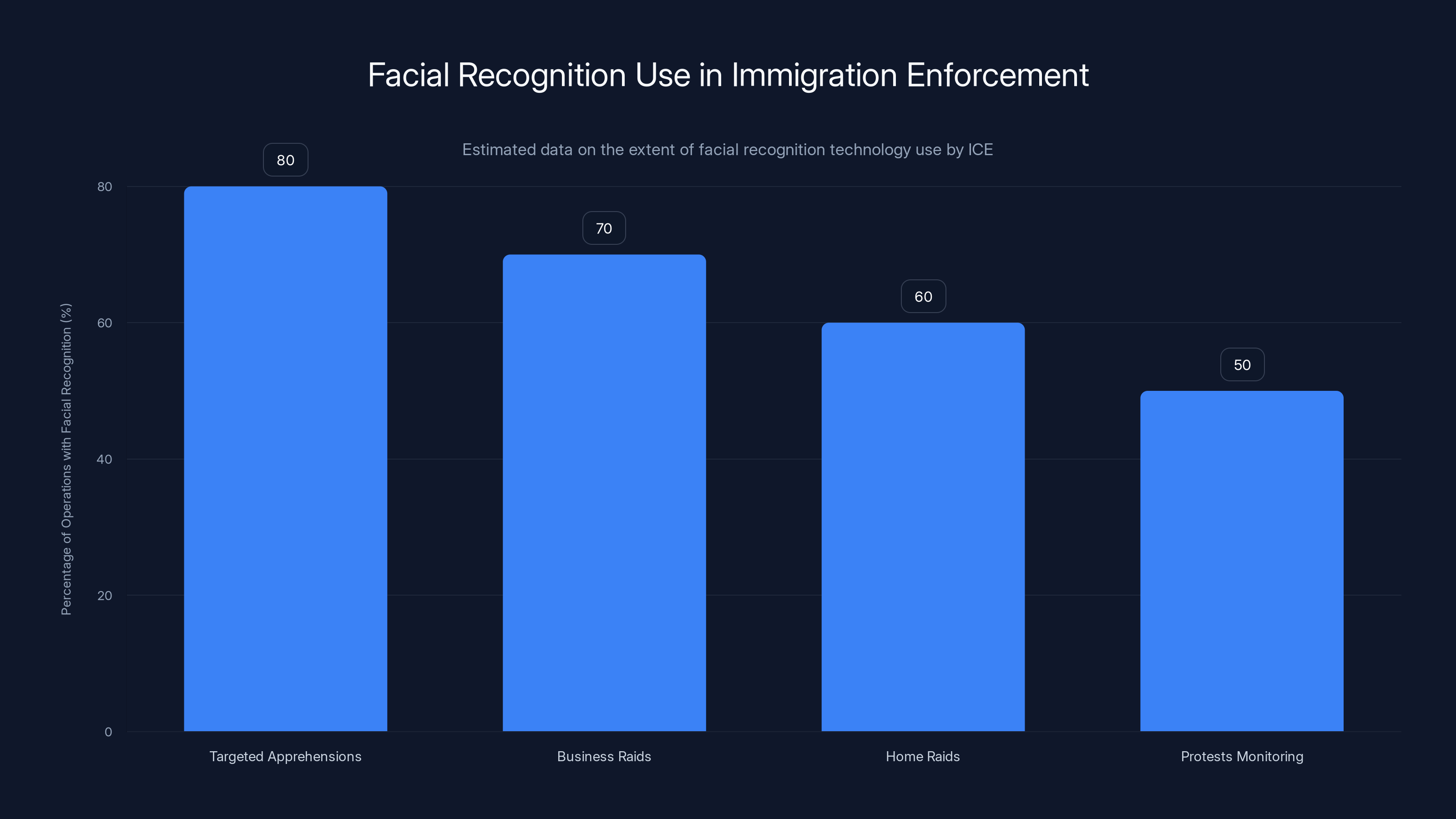

Facial recognition technology is estimated to be used in 50-80% of ICE operations, highlighting its extensive deployment in immigration enforcement. Estimated data.

The Technical Reality: Accuracy, Error Rates, and Demographic Bias

Facial recognition technology isn't perfect. Far from it. But the government often treats it as if it is, relying on it to make identifications without independently verifying the match or disclosing the confidence level of the identification.

Accuracy varies significantly based on multiple factors. The demographics of the person being identified matter. Studies have consistently shown that facial recognition systems are significantly more accurate when identifying white men, particularly with light skin. They're less accurate for women, people with darker skin tones, and people wearing glasses or masks. Some systems have false positive rates approaching 30% or higher for certain demographic groups.

Lighting conditions affect accuracy. Angle of the face matters. Whether someone is smiling or frowning changes the analysis. Age-related changes to facial features over time can affect matching. A system that was 95% accurate in laboratory conditions with controlled images might be 70% accurate with a blurry photo taken from a distance.

When federal agents tell you they've used facial recognition to identify you, they're not disclosing the confidence level of that identification. They're not telling you the error rate for your demographic. They're not explaining what database they searched or what the false positive rate is for that specific system. They're simply asserting that they know who you are based on a facial scan.

And if they've made a mistake? There's no automatic correction mechanism. You'd have to prove the error yourself. You'd have to go through appeals processes designed by the same agency that made the error. You'd have limited access to information about how the system works or what data it's using.

This is particularly problematic in Cleland's case. If the agent's identification of her was even slightly inaccurate, if there was any element of doubt or margin of error, she would have no way to know. The identification was asserted as fact. Her revocation followed immediately. The burden is on her to prove the identification was wrong, not on the government to prove it was right.

Government Surveillance and Immigration Enforcement: The Escalation

The Trump administration's immigration crackdown has driven significant expansion in surveillance capabilities and deployment. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has approximately 6,500 agents. In any given year, they conduct millions of enforcement operations ranging from targeted apprehensions to raids on businesses and homes.

Facial recognition technology is being used extensively in these operations. Agents use it to verify citizenship status, to identify people with outstanding warrants, and increasingly, to identify people engaged in activities the government views as problematic, including observing or protesting enforcement actions.

The integration of facial recognition into immigration enforcement has several concerning aspects. First, immigrants and non-citizens have even fewer privacy protections than citizens. The government can condition immigration benefits on consent to surveillance. Non-citizens can be subjected to facial recognition scans as a condition of entry or as part of arrest and detention processes.

Second, the combination of facial recognition with databases of immigration information creates a particularly powerful surveillance apparatus. When agents scan your face, they're not just identifying who you are. They're potentially accessing information about immigration status, prior enforcement interactions, addresses associated with you, and other sensitive data.

Third, the use of facial recognition in immigration enforcement affects vulnerable populations disproportionately. Immigrants living in the United States, regardless of legal status, are subject to facial recognition scanning when they interact with CBP, ICE, or when arrested by local law enforcement operating in cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

The combination of these factors has led to a significant expansion in government surveillance capabilities targeted at both immigrants and citizens engaged in observing or protesting immigration enforcement.

Clearview AI has a larger database and higher privacy concerns compared to Mobile Fortify, which excels in real-time scanning. Estimated data based on typical features.

Clearview AI and Mobile Fortify: The Companies Behind the Technology

Federal agents are using facial recognition systems from private companies. Clearview AI is one of the most prominent providers. Mobile Fortify is another system being deployed. Both companies provide technology that allows agents to scan faces and compare them against databases.

Clearview AI operates differently from traditional facial recognition systems. Rather than maintaining a controlled database that law enforcement feeds verified identifications into, Clearview AI has scraped billions of images from public websites, social media, and other online sources. The company then provides law enforcement with access to search this massive database without any verification that the people whose images are in the database consented to be included.

This raises significant privacy concerns. If your photo appears anywhere on the internet and was scraped by Clearview AI, you could be identified without your knowledge or consent. Clearview AI has been involved in lawsuits alleging privacy violations. Multiple states have restricted or banned its use. But federal immigration agencies continue to use the technology.

Mobile Fortify operates somewhat differently, but it also allows real-time facial scanning and identification. The system allows agents in the field to scan faces and get immediate results about whether a person is known to the system.

Neither company is required to disclose accuracy rates or error statistics. Neither company is required to explain how they handle false identifications or how long they retain data. The government agencies using these tools are not required to disclose they're using them or to obtain warrants before scanning your face.

This creates a situation where private companies are profiting from government surveillance, and the public has virtually no transparency into how these systems work or what happens to the data they generate.

The Legal Framework: What Actually Governs This?

Here's what's genuinely alarming: there isn't a comprehensive federal legal framework governing the use of facial recognition by government agencies. We have a patchwork of state laws, some agency guidelines, and scattered court decisions, but no overarching federal law that clearly establishes when facial recognition can be used, what accuracy standards must be met, or what due process must be provided to people identified by the technology.

The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, but courts have been inconsistent about whether facial recognition without a warrant constitutes a search that requires legal justification. Some courts have found it does. Others have found that because the scanning happens in public and doesn't involve physical contact, it's not a search at all.

The First Amendment protects freedom of speech and assembly, but it's not clear whether the government can use surveillance tools to identify people engaged in protected speech and then use that identification as the basis for punishing them. This is exactly what the Cleland case raises.

The Fifth Amendment due process clause requires that before the government deprives someone of a benefit or liberty interest, there must be notice and an opportunity to be heard. But the government argues that Global Entry is a privilege, not a right, so due process requirements might not apply in the same way.

Federal courts in different jurisdictions have reached different conclusions about these issues. There's no Supreme Court decision clearly establishing constitutional limits on government use of facial recognition. This means the technology is being deployed in a legal gray zone where the government can argue there are few restrictions on its use.

Some states have passed facial recognition laws. California, Illinois, and a handful of others have implemented restrictions on how facial recognition can be used by law enforcement. But these state laws don't apply to federal immigration enforcement. The federal government operates largely outside state law restrictions.

This legal vacuum is the real problem. Facial recognition technology is advancing rapidly, but legal frameworks governing its use are falling far behind. By the time courts rule on cases like Cleland's, the technology will have become even more sophisticated and more widely deployed.

What Cleland's Case Tells Us About Retaliation and Chilling Effects

Cleland's situation is important because it illustrates a specific pattern. Federal agents confronted her about observing their activities. They explicitly told her they had identified her using facial recognition. A few days later, her travel benefits were revoked with no clear connection to any law she violated.

Was this retaliation? Cleland certainly believes it was. She was exercising a legally protected right to observe federal agents in public. In response, she was confronted and threatened with arrest if she continued. Then her government benefits were revoked.

The government might argue that the revocation was based on conduct that actually does violate immigration or customs law, and that the timing is coincidental. But there's no transparency into what that alleged violation actually is. Cleland was never told. The notification letter was vague. She was given no opportunity to respond before the revocation.

This is the chilling effect in action. Cleland has instructed her family to be cautious and return inside if they see unfamiliar vehicles. She's concerned about being detained or arrested in the future. She's aware that border patrol now has her license plate and personal information. She's stopped actively observing federal agents.

Why would she continue? She's seen what happens. She's experienced the consequences. She's facing potential retaliation. The reasonable response is to stop engaging in the lawful activity that prompted the government response.

Multiply this across thousands of people. If everyone who observes federal agents knows they could face loss of travel benefits, increased scrutiny, or other retaliation, fewer people will observe. Fewer people will document enforcement actions. Fewer people will hold federal agents accountable. And that's exactly what federal agencies want.

The Intersection of Technology and Government Power

Cleland's case is ultimately about the intersection of rapidly advancing technology and government power. Facial recognition makes it possible for federal agents to identify people instantly and remotely. Administrative tools like Global Entry revocation make it possible to punish people without meaningful due process.

When you combine surveillance technology with broad administrative power and minimal transparency or oversight, you create a system where government can effectively control behavior through surveillance and selective punishment. People learn that engaging in certain activities might result in identification and consequences. They avoid those activities. Their behavior changes. Government control expands.

This isn't conspiracy thinking. This is how institutions work. Federal agencies aren't necessarily planning this as some coordinated scheme. But they have incentives to expand control over immigration enforcement activities, which they view as a national security and public safety function. Facial recognition technology provides tools that make that expansion possible. Administrative tools like trusted traveler program revocation provide mechanisms for enforcement.

The question is whether we're okay with this. Are we comfortable with federal agents using facial recognition to identify people engaging in lawful activities? Are we comfortable with those identifications resulting in loss of government benefits without meaningful due process? Are we comfortable with immigration enforcement driving broader surveillance expansion that affects all travelers?

These questions don't have easy answers, but they're questions we need to be asking now, before facial recognition becomes even more embedded in government operations.

Moving Forward: What Needs to Change

Multiple reforms could address the problems illustrated by Cleland's case. These aren't fringe suggestions. Civil rights organizations across the political spectrum have proposed many of these reforms.

First, we need clear federal legislation governing facial recognition use by government agencies. This legislation should specify when facial recognition can be used, what accuracy standards must be met, and what transparency and oversight mechanisms are required. It should establish clear limitations on using facial recognition to identify people engaged in protected speech or assembly.

Second, we need due process protections for people identified by facial recognition. If an identification is going to result in loss of a benefit or liberty interest, there should be notice and a meaningful opportunity to challenge the identification. The government should have to prove the identification is accurate and that the conduct actually violates law.

Third, we need limitations on the use of facial recognition data. If data is collected, it shouldn't be retained indefinitely. It shouldn't be shared widely between agencies. It shouldn't be used for purposes beyond those that were clearly authorized.

Fourth, we need transparency about facial recognition systems used by government agencies. The public should know what systems are being used, who's using them, what accuracy rates they have, and how often they're used. Government agencies should publish regular reports on facial recognition deployment.

Fifth, we need clear rules about the consequences that can flow from facial recognition identification. Global Entry and TSA Pre Check revocation shouldn't be an available tool for punishing people for protected activity. If the government wants to prosecute someone, it should do so directly, not through administrative revocation of travel benefits.

Sixth, we need remedies for people wrongly identified by facial recognition or harmed by its use. If an incorrect identification leads to loss of benefits or other harms, people should be able to sue for damages. Agencies should be required to correct records when errors are found.

These reforms aren't radical. They're incremental steps toward bringing facial recognition governance in line with constitutional principles. But they require political will to implement.

The Bigger Picture: Facial Recognition in American Life

Cleland's case isn't just about immigration enforcement. It's about a broader question: what role should facial recognition play in American law enforcement and government surveillance?

Facial recognition is expanding beyond immigration enforcement. Local police departments are using it. Some states have integrated it into driver's license systems, creating massive facial recognition databases. Private companies are using it for commercial purposes. The technology is becoming woven into the fabric of American life.

Once a surveillance technology becomes normal, it becomes harder to restrict. Once people accept facial recognition at the border, it becomes easier to deploy it at the airport, then at the train station, then in public spaces. The gradual expansion of surveillance capability becomes normalized.

This is why Cleland's case matters even if you don't care about immigration enforcement. The surveillance infrastructure being built for immigration enforcement will be repurposed for other law enforcement functions. The lack of guardrails around facial recognition in one context creates a model for deployment in other contexts.

Countries like China have built comprehensive facial recognition surveillance networks. The United States isn't there yet, but the direction is clear. Without legal restrictions and meaningful oversight, the technology will continue to expand. The government's power to track, identify, and target individuals will grow. Privacy protections will erode.

Cleland's story is a warning. It's also a moment where change is still possible. Courts are grappling with these issues. Legislatures are beginning to consider restrictions. Public awareness is growing. But windows for action don't stay open forever. Once facial recognition surveillance is fully embedded in government operations, it becomes exponentially harder to restrict.

FAQ

What is facial recognition technology?

Facial recognition is a biometric system that analyzes unique characteristics of a person's face—such as distance between eyes, nose shape, jawline structure—and compares them against known databases of faces to identify individuals. Federal agencies use these systems to scan faces in real-time and match them against databases without requiring warrants in many cases. The technology varies significantly in accuracy depending on image quality, lighting, demographics, and the specific system being used.

How did federal agents use facial recognition to identify Nicole Cleland?

When Cleland was pulled over after following a suspected federal enforcement vehicle, an agent told her directly that they had used facial recognition technology to identify her by name. This means they scanned her face, ran it through a facial recognition database, and obtained her identity instantly. The agent used this identification to confirm her identity and warn her about her conduct, demonstrating how facial recognition enables instant identification in law enforcement encounters.

Why was Cleland's Global Entry revoked?

Cleland received notification that her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check status had been revoked based on a determination that she had "been found in violation of any customs, immigration, or agriculture regulations, procedures, or laws in any country." However, she was never detained, arrested, or formally charged with violating any law. The rapid revocation after her facial recognition identification and confrontation by federal agents suggests potential retaliation, though the government has not disclosed the specific basis for the revocation.

What is Global Entry and TSA Pre Check?

Global Entry is a trusted traveler program administered by U. S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) that allows expedited processing for international travelers through dedicated kiosks. TSA Pre Check is a separate program administered by the Transportation Security Administration that allows expedited airport security screening. Both programs require background checks and vetting, and both can be revoked by the government, though the reasons for revocation are often kept confidential with minimal due process protections.

Is facial recognition legal in law enforcement?

Facial recognition use by law enforcement exists in a complex legal gray area. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches, but courts have disagreed about whether facial recognition without a warrant constitutes a search requiring legal justification. There is no comprehensive federal law governing facial recognition use by government agencies, though some states have implemented restrictions. The lack of clear legal framework means the government often operates without explicit authorization or restriction.

What are the accuracy concerns with facial recognition?

Facial recognition systems have significantly varying accuracy rates depending on image quality, lighting conditions, demographic characteristics, and the specific system being used. Studies consistently show that the technology is less accurate when identifying women and people with darker skin tones compared to white men. False positive rates can exceed 30% in some systems and demographic groups. When federal agents identify someone by facial recognition, they typically don't disclose the confidence level or error rate of the identification.

Can I challenge a Global Entry or TSA Pre Check revocation?

Yes, you can file an appeal, but the appeals process is limited in effectiveness. You can submit a request for reconsideration to CBP or TSA, but the government is not required to provide detailed explanations for its decisions, and you don't get a hearing or opportunity to present evidence in a meaningful way. The appeals process often involves resubmitting the same request to the agency that made the original decision, making it difficult to successfully challenge revocations.

Is using facial recognition to identify protesters legal?

Federal agents can legally use facial recognition to identify people in public, even those engaged in protesting or observing enforcement activities. However, the First Amendment protects freedom of speech and assembly, and some legal scholars argue that using facial recognition specifically to identify and retaliate against people engaged in protected speech violates the First Amendment. This is an emerging area of law, with lawsuits pending that challenge facial recognition use against protesters and legal observers.

What databases do facial recognition systems search?

Federal agencies have access to multiple facial recognition databases, including passport photos, driver's license images from state DMV systems, mugshots from arrest records, and in some cases, images scraped from the internet by companies like Clearview AI. When an agent scans your face, they're running it against these multiple databases. You don't control whether your image is in these databases, and you have limited ability to discover whether you've been identified.

What is the "chilling effect" in the context of civil rights?

A chilling effect occurs when threats of government punishment or retaliation cause people to refrain from exercising their constitutional rights, even when that exercise is legally protected. In Cleland's case, her experience of retaliation for observing federal agents might cause others to avoid similar conduct, even though observation is lawful. This creates an indirect government control over behavior through surveillance and selective punishment, which undermines First Amendment protections.

What reforms are being proposed for facial recognition governance?

Reforms being advocated by civil rights organizations include: comprehensive federal legislation governing facial recognition use, clear accuracy standards and transparency requirements, due process protections for people identified by facial recognition, limitations on data retention and inter-agency sharing, restrictions on using facial recognition to identify people engaged in protected activities, and remedies for people wrongly identified. Some states have already implemented restrictions, but federal-level coordination is lacking.

Conclusion: Privacy, Power, and the Future of Surveillance

Nicole Cleland's story is about more than one woman's revoked travel benefits. It's about the structure of power in American democracy and how rapidly advancing technology is reshaping the relationship between government and citizens.

Facial recognition technology is not inherently good or bad. Like any tool, its impact depends on how it's governed and what constraints are placed on its use. In the context of border security and immigration enforcement, facial recognition can serve legitimate purposes. It can help identify people wanted for crimes. It can help verify identities. It can make travel processing more efficient.

But without clear legal frameworks, meaningful oversight, and due process protections, facial recognition becomes a tool for government control. It enables surveillance without consent. It enables identification without transparency. It enables punishment without clear legal justification. And it creates incentives for people to avoid lawful conduct because they fear surveillance and retaliation.

We're at an inflection point. The technology is here, and it's expanding rapidly. We can still establish legal frameworks that govern its use appropriately. We can still require transparency and due process. We can still protect privacy and constitutional rights. But the window for action is closing. Once facial recognition becomes fully embedded in government operations, the opportunity to shape its governance will diminish significantly.

Cleland's case is being litigated in federal court. The outcome will help determine whether the government can use facial recognition to identify people engaged in lawful activities and then revoke their government benefits without meaningful due process. It will help establish precedent for whether First Amendment protections extend to activities conducted in the age of facial recognition surveillance.

But the larger question extends beyond her case. It's about what kind of society we want to be. Do we want a society where government can identify us instantly, track our movements, and punish us based on opaque administrative decisions made with minimal transparency or oversight? Or do we want a society where privacy is respected, where government power is constrained, and where people can exercise constitutional rights without fear of retaliation?

These aren't abstract questions. They're about the lived experience of people like Cleland who are trying to hold government accountable and exercise their rights while facing increasingly sophisticated surveillance tools and government power. Her experience suggests that surveillance is already affecting behavior and political participation. Without reform, that effect will only grow.

The technology isn't going away. But its governance can change. Laws can be passed. Regulations can be implemented. Court decisions can establish constitutional limits. Institutional accountability can be demanded. But all of this requires people to understand what's happening and demand better.

Cleland's story is a starting point for that conversation. It demonstrates the power of facial recognition surveillance. It shows how rapidly government can act to revoke benefits without meaningful due process. It illustrates the chilling effect of surveillance on lawful political activity. And it raises questions that every American should be asking about the future of privacy, rights, and government power in an age of advanced surveillance technology.

Key Takeaways

- Federal agents used facial recognition to identify Nicole Cleland during lawful observation of immigration enforcement, demonstrating instant identification capability without warrant requirements

- Her Global Entry and TSA PreCheck were revoked three days later with vague reasoning and no meaningful opportunity to appeal, illustrating absence of due process protections

- Facial recognition systems have demographic bias, accuracy limitations, and lack transparency, yet federal agencies use them to make identification determinations without disclosure of error rates

- The rapid revocation suggests potential retaliation for protected First Amendment activity, creating a chilling effect that discourages people from observing or protesting government enforcement

- No comprehensive federal legal framework governs facial recognition use by government agencies, leaving surveillance technology deployment largely unconstrained by constitutional protections

Related Articles

- Face Recognition Surveillance: How ICE Deploys Facial ID Technology [2025]

- Don Lemon and Georgia Fort Arrested for Covering Anti-ICE Protest [2025]

- ICE's Military Playbook: Why Paramilitary Tactics Fail in Law Enforcement [2025]

- License Plate Readers & Privacy: The Norfolk Flock Lawsuit Explained [2025]

- Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation, Privacy & Free Speech [2025]

- Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement [2025]

![Facial Recognition and Government Surveillance: The Global Entry Revocation Story [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/facial-recognition-and-government-surveillance-the-global-en/image-1-1769814462473.jpg)