Intel's GPU Strategy: Can It Challenge Nvidia's Market Dominance?

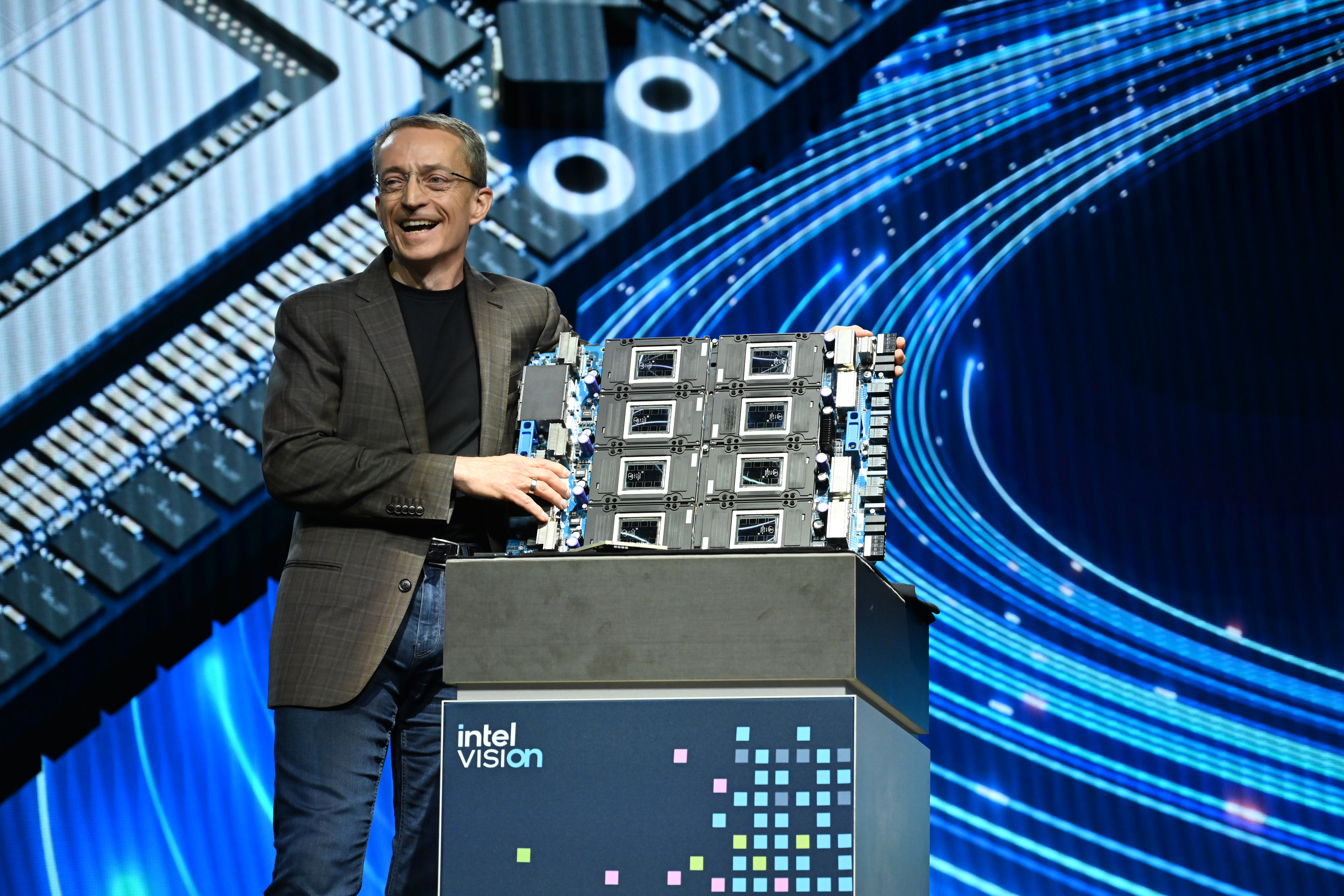

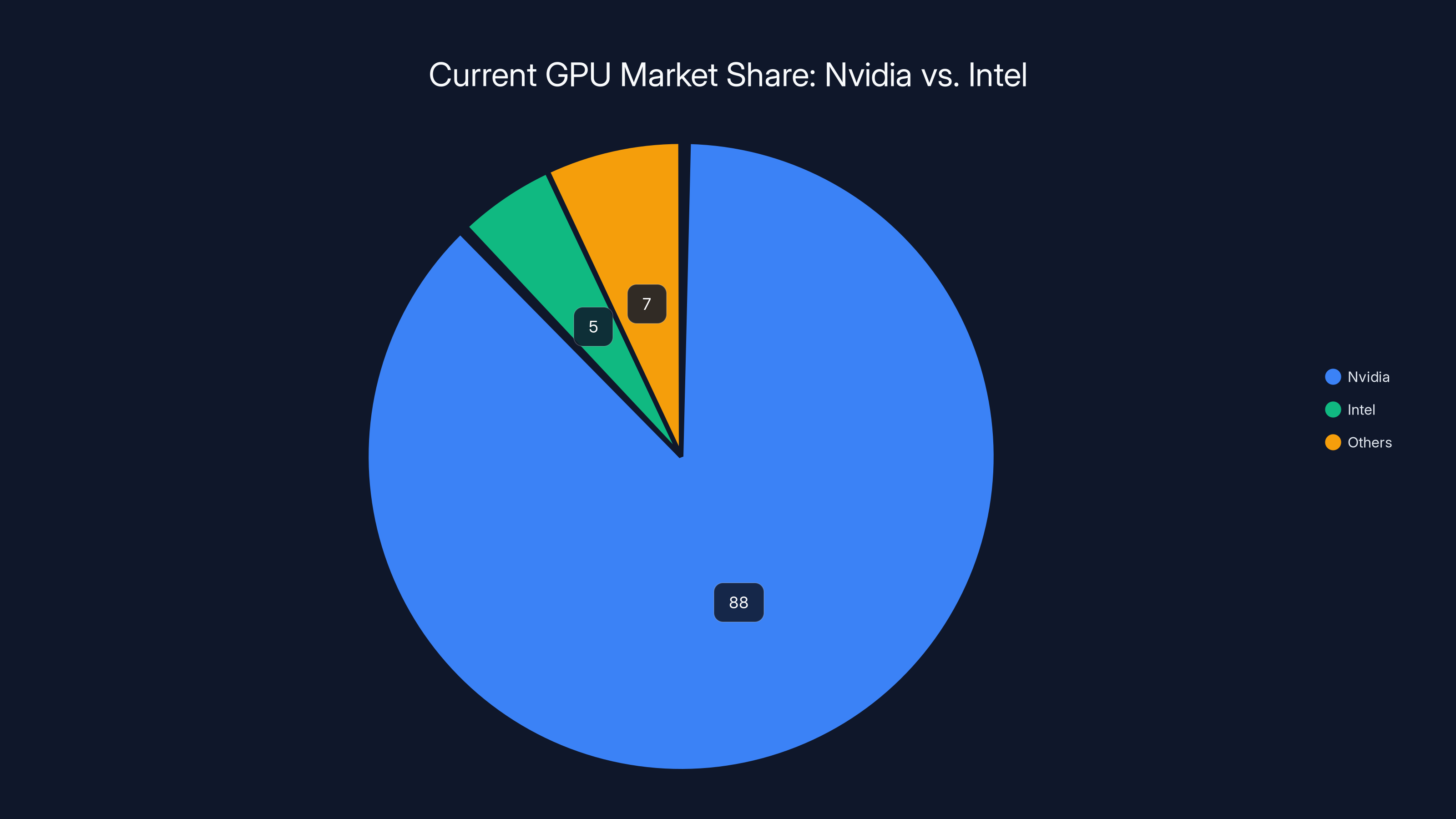

Intel just made a massive bet. In early 2026, CEO Lip-Bu Tan announced that the company will start producing graphics processing units, a move that signals a fundamental shift in Intel's competitive strategy. This isn't some minor hardware tweak. This is Intel saying it's no longer comfortable being the processor company that powers servers. It's jumping into a market where Nvidia owns roughly 88% share in AI accelerators and has completely reshaped the semiconductor landscape.

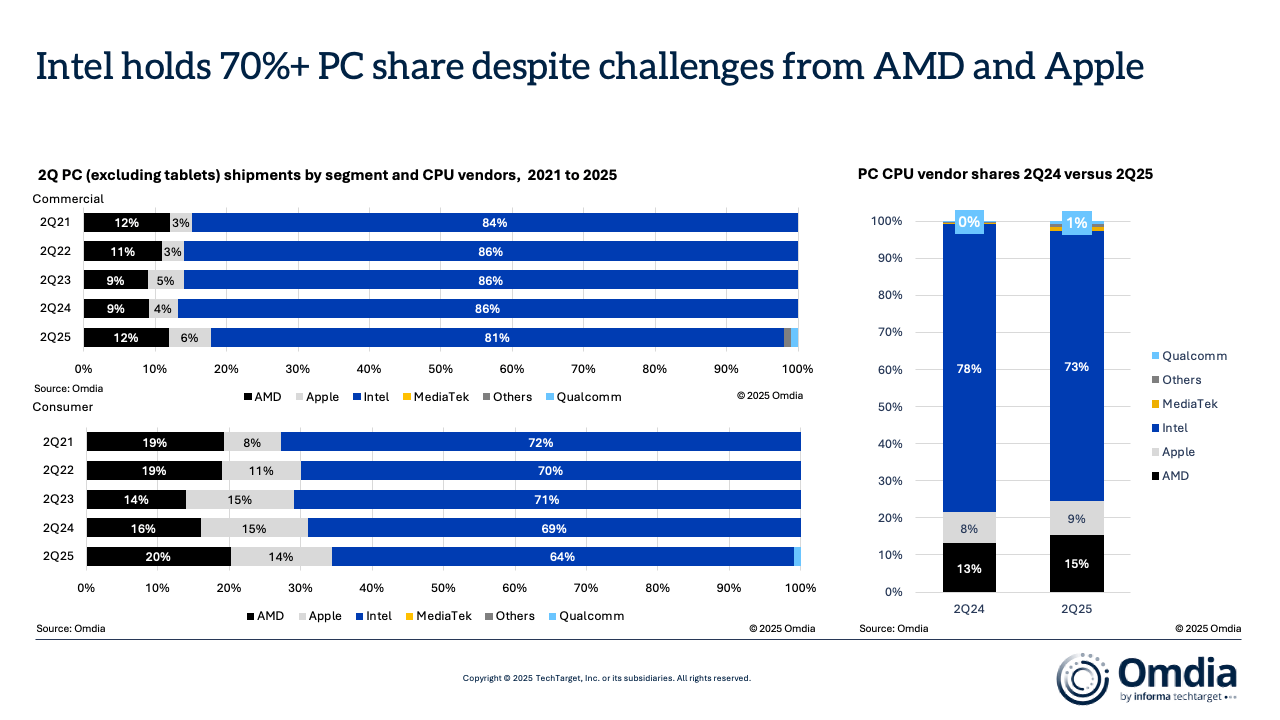

Here's what makes this announcement so interesting: Intel spent decades dominating CPUs. Xeon processors were the backbone of data centers worldwide. But somewhere along the way, the game changed. AI models demand parallel processing at scales that traditional CPU architectures can't deliver efficiently. Nvidia's GPUs weren't invented by Nvidia, but they perfected the market. They understood the inflection point before anyone else, built the software ecosystem around it, and now they're essentially printing money.

Intel sees this. They're not blind to the fact that their core CPU business is under pressure. They're also not ignorant of the revenue tsunami that GPU production generates. So they're doing what Intel does when threatened: they're building something new.

But here's the real question nobody's talking about enough: Can Intel actually pull this off? The GPU market isn't like the CPU market where Intel once ruled. It's dominated by a company that has an eight-year head start, an absolutely locked-in ecosystem, and customers who've baked Nvidia dependencies into every line of code. This is David versus Goliath, except David is Intel, a

Let's dig into what Intel's actually doing, why it matters, and whether they have any realistic shot at disrupting a market that's been locked down tighter than Fort Knox.

Understanding the GPU Market Shift That Changed Everything

GPUs weren't invented for AI. That's important context. Graphics processing units existed for decades before anyone realized they were perfect for training neural networks. Nvidia made their first GPU in 1999. For years, they were used exclusively for gaming and graphics rendering. Developers would write games, artists would render video, and gamers would buy Nvidia cards for their rigs.

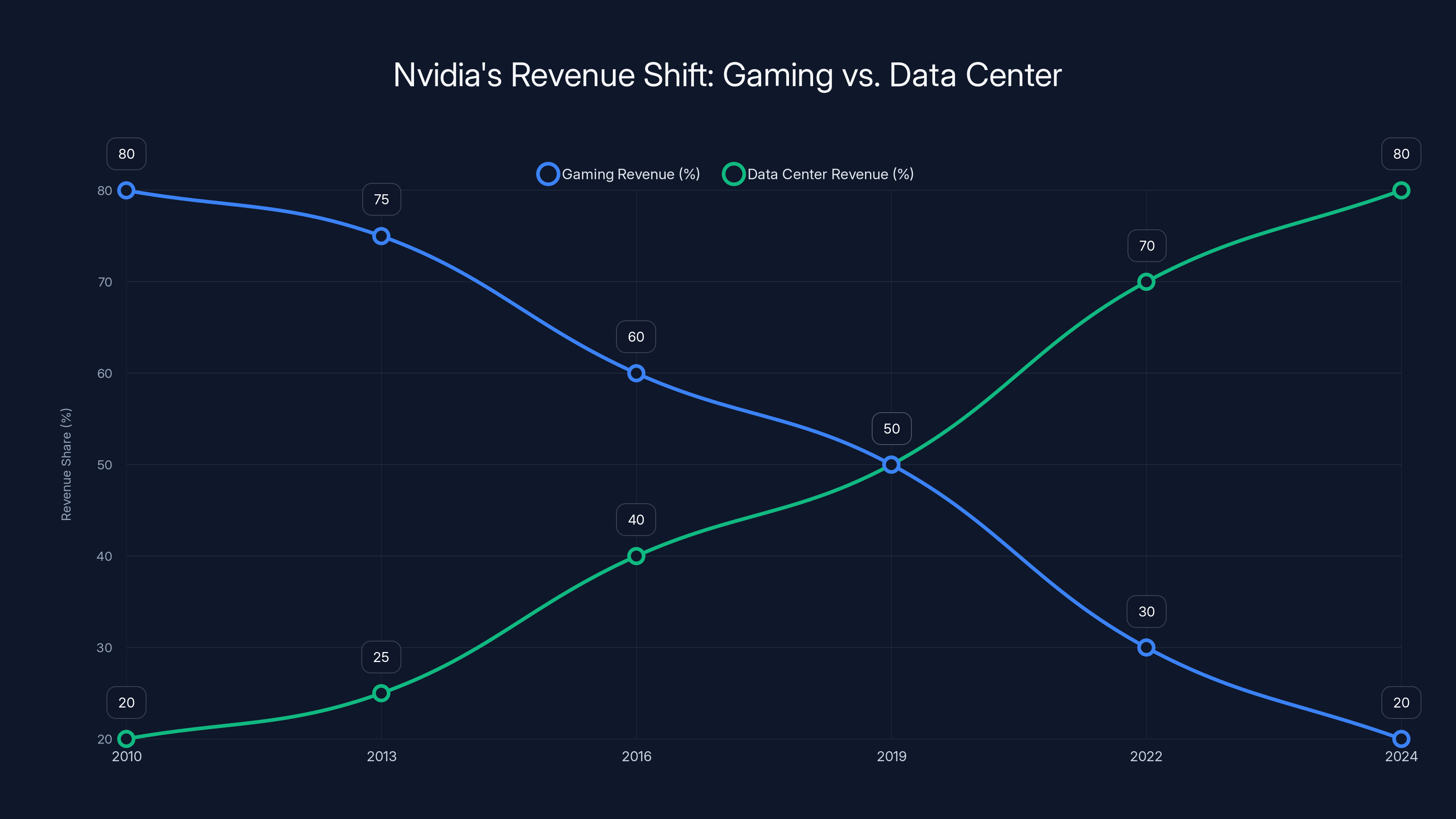

Then something shifted around 2011. Researchers at universities started realizing that the massive parallel processing capabilities of GPUs could dramatically accelerate neural network training. You could take a task that would take weeks on a CPU and compress it down to days on a GPU. The math worked out spectacularly.

By the time deep learning really exploded around 2016, Nvidia had already spent 15 years building CUDA, their software platform that lets developers write optimized code for their hardware. CUDA became the de facto standard. If you wanted to train a neural network fast, you learned CUDA. If you needed to run inference at scale, you bought Nvidia GPUs.

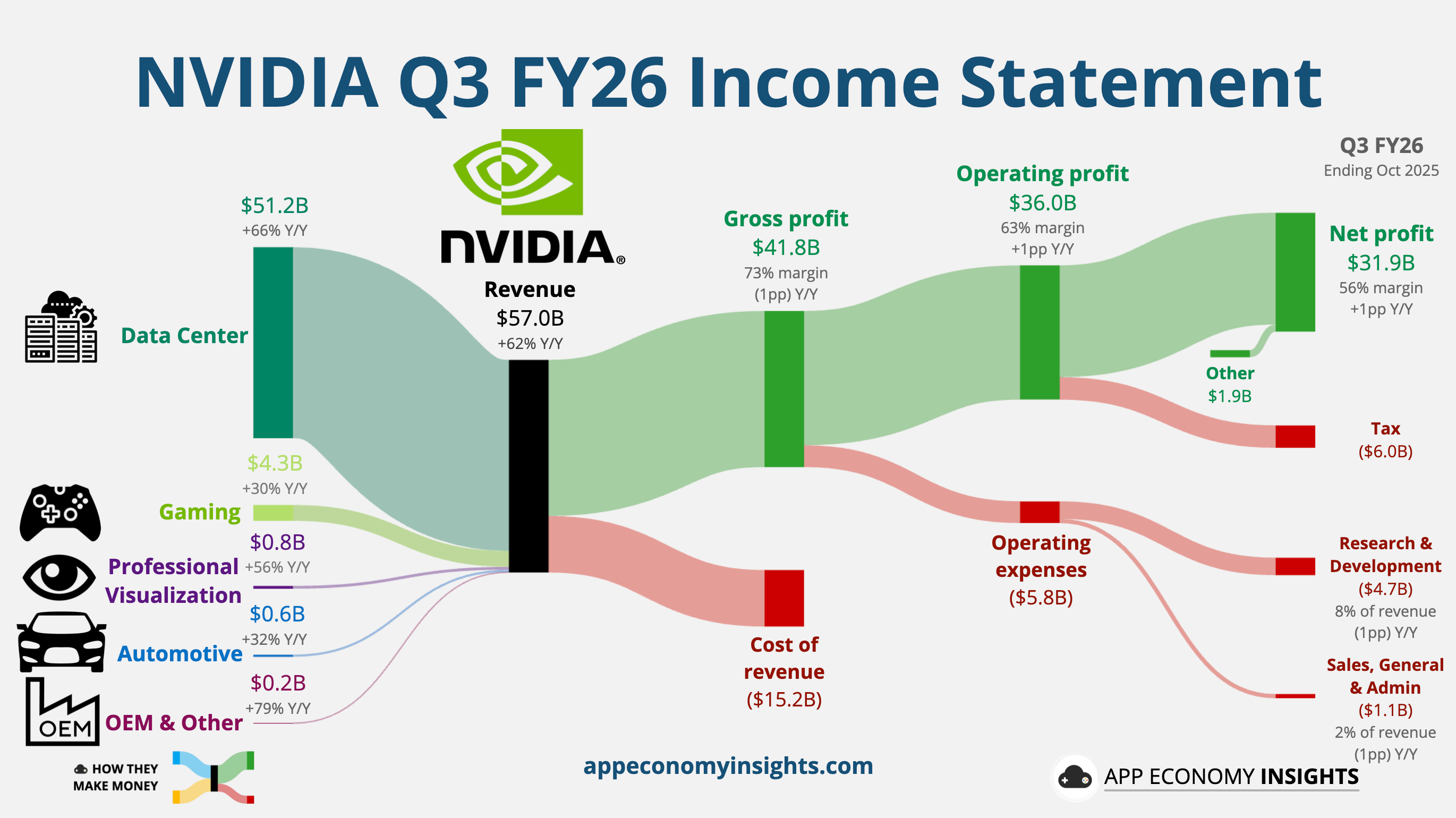

That's when the market actually flipped. Nvidia's data center revenue, which had been small relative to their gaming business, started growing exponentially. By 2023, data center revenue was roughly 80% of their total business. By 2024, it had climbed higher.

The semiconductor industry watched this happen. AMD watched. Intel watched. Qualcomm watched. But Nvidia built such a commanding lead that catching up felt impossible. They didn't just have the best hardware. They had the best software, the best developer relations, the best ecosystem, and customers who couldn't afford to switch even if they wanted to.

This is what Intel is walking into. Not a market with room for competitors. A market with a fortress that's been reinforced for over a decade.

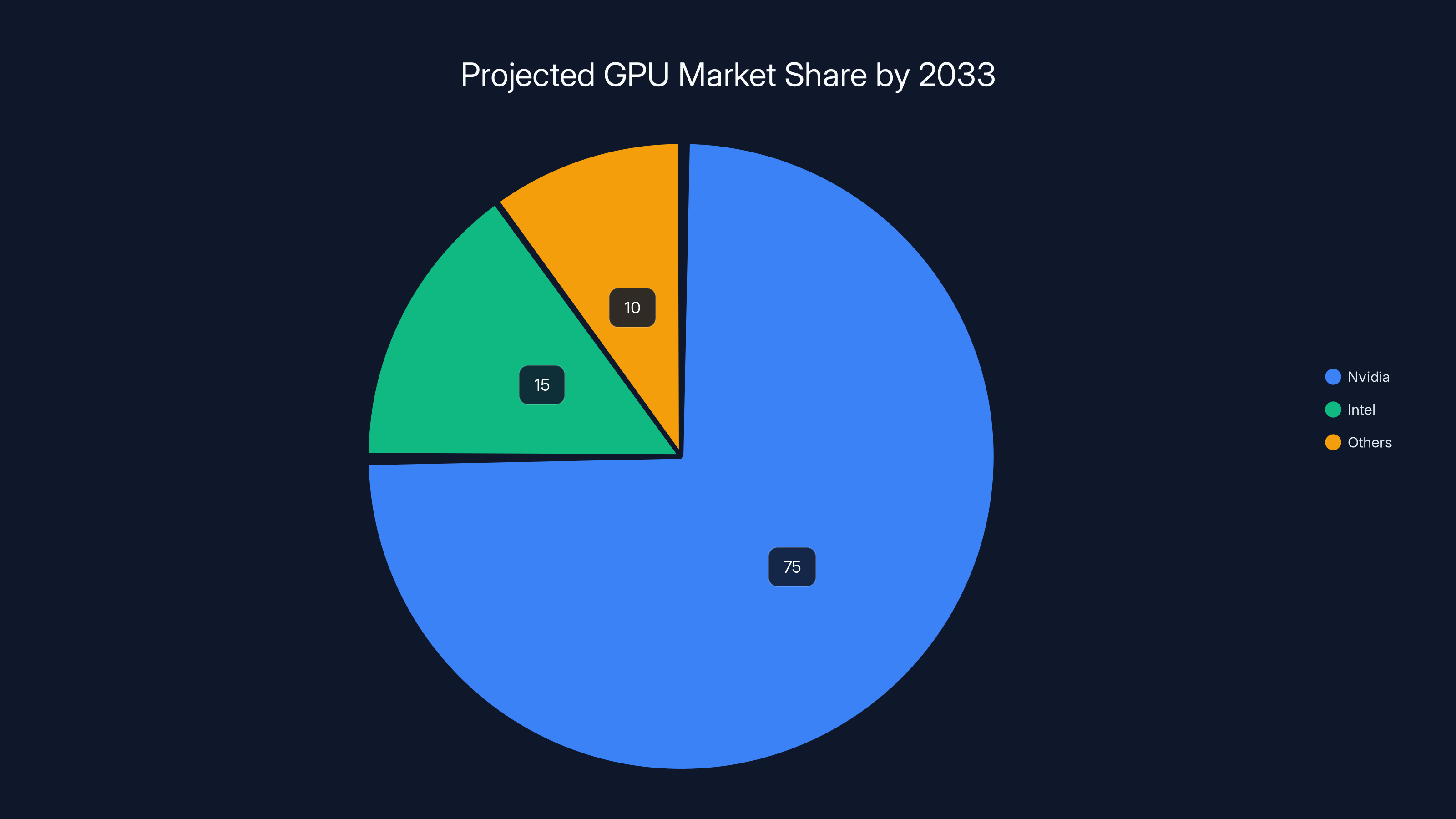

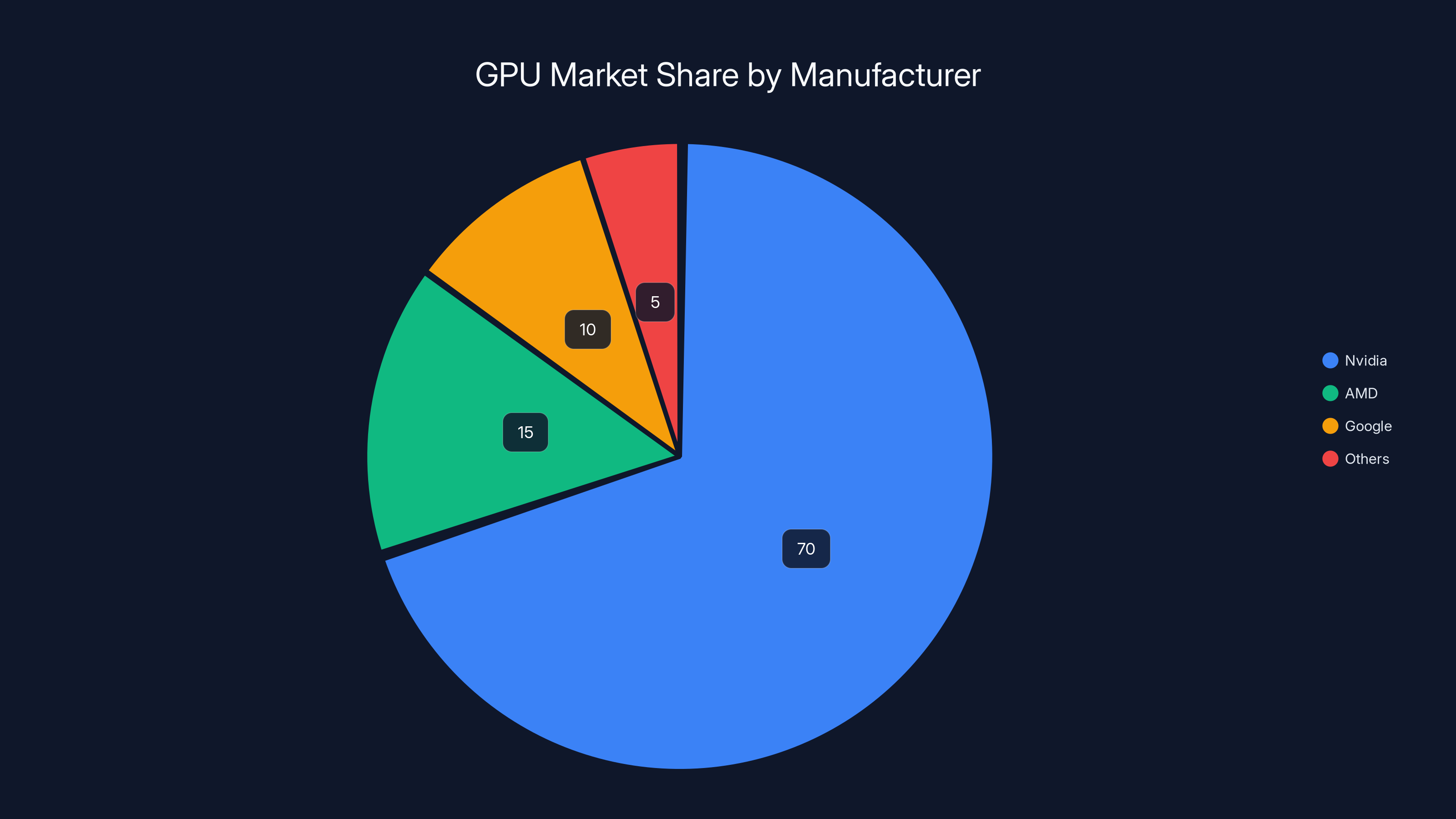

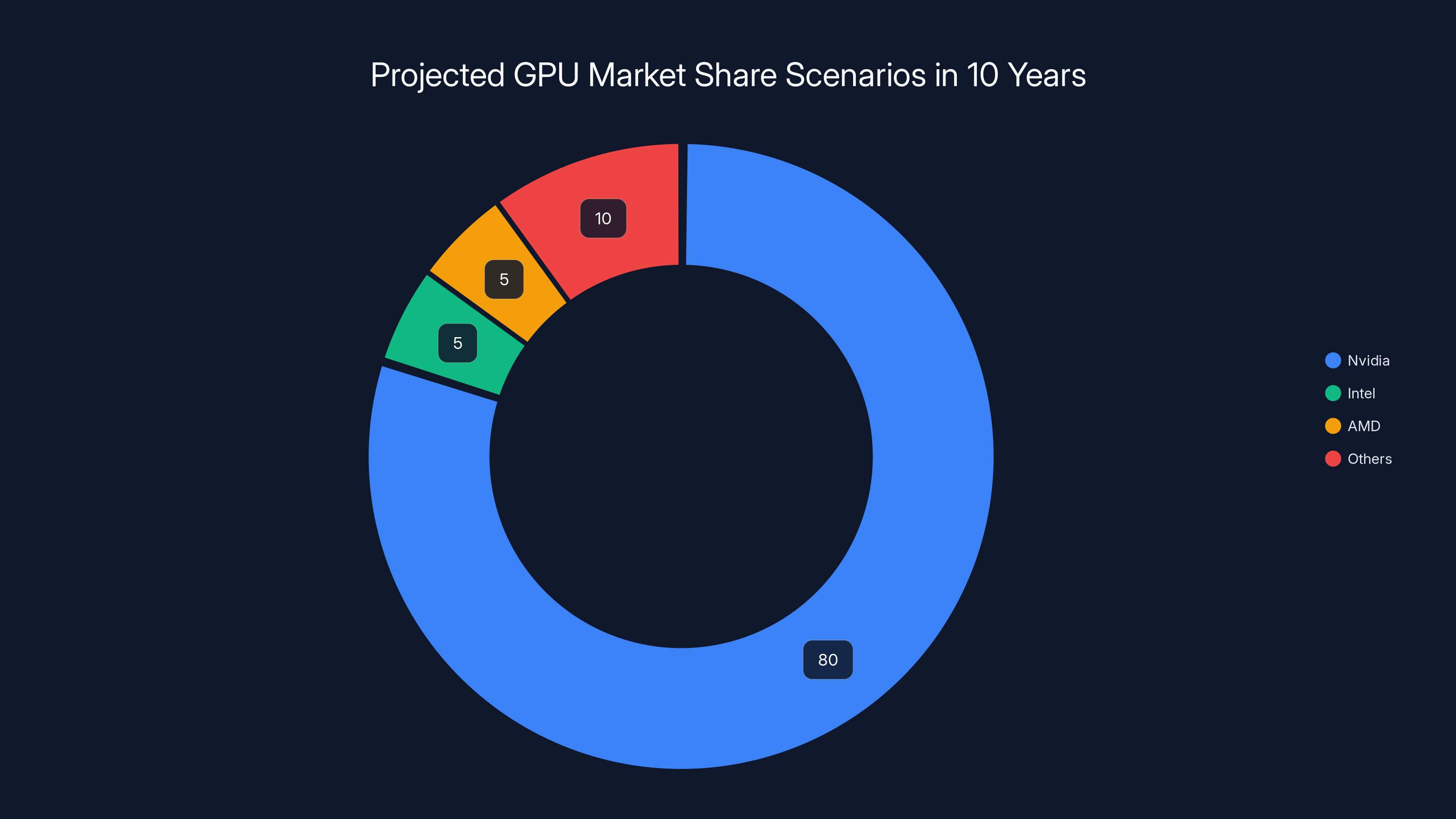

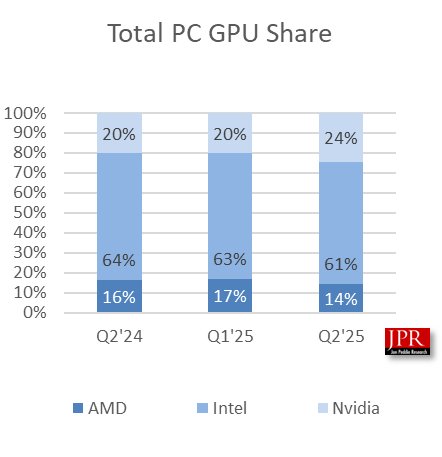

Nvidia is projected to maintain a dominant 75% market share by 2033, with Intel potentially capturing 15% if they execute well. Estimated data.

Intel's GPU Ambitions: What We Know So Far

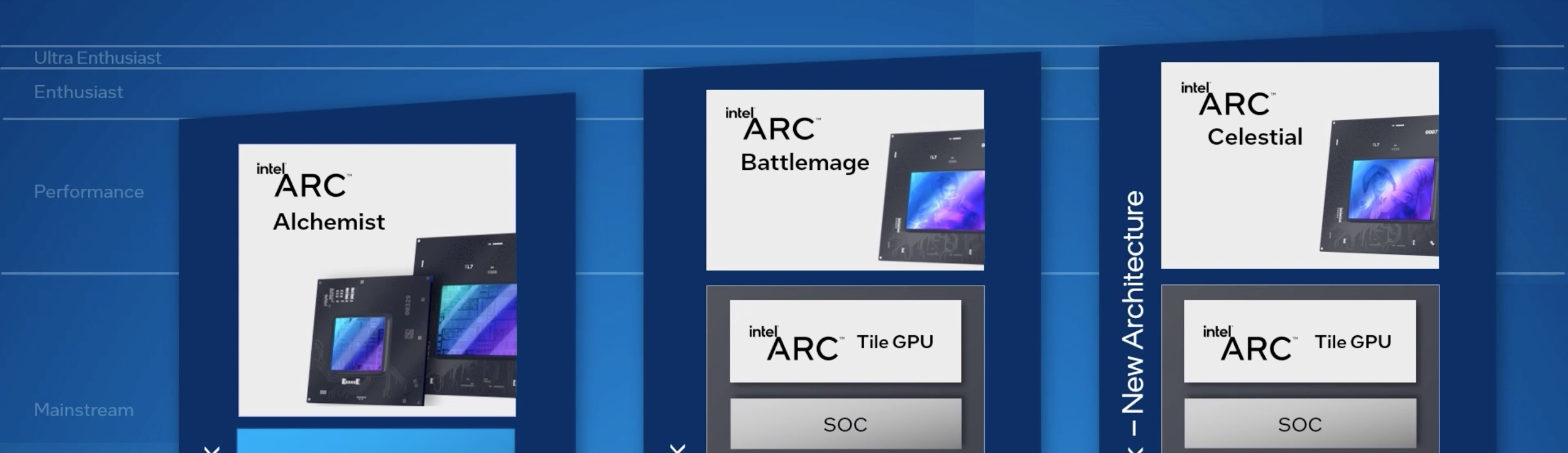

Let's talk specifics about what Intel's actually announced and what we can reasonably infer from their moves.

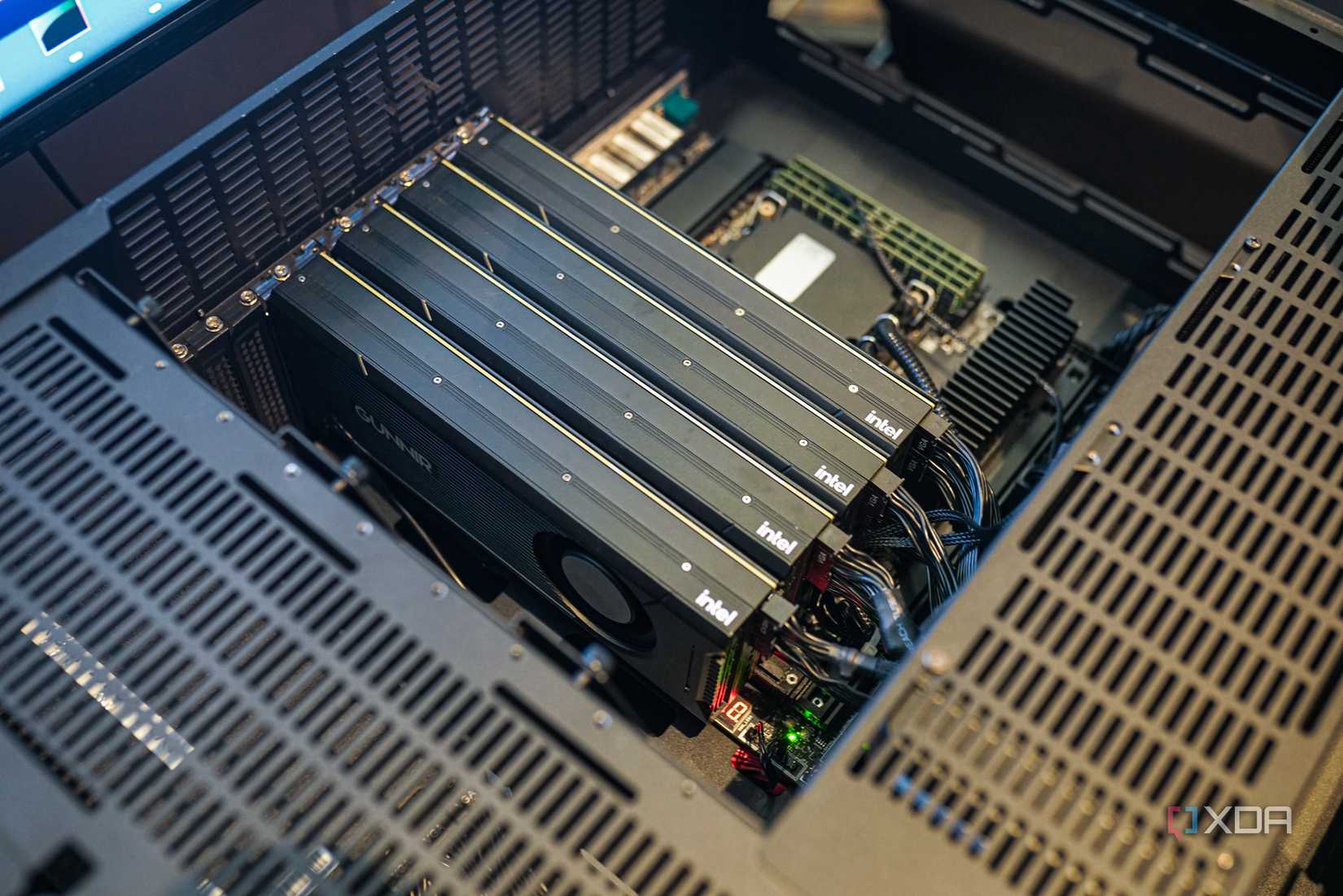

Intel has tapped Kevork Kechichian to oversee the GPU initiative. Kechichian was brought in as executive vice president and general manager of Intel's data center group back in September. He's an engineer-focused executive, which matters. You don't hire someone with that background if you're planning to do this casually.

They also hired Eric Demmers in January specifically for GPU development. Demmers spent more than 13 years at Qualcomm, most recently as a senior vice president of engineering. Again, this signals seriousness. You don't bring in VP-level talent from a competitor unless you're building something substantial.

But here's what's telling: Tan said Intel will develop its GPU strategy around customer demands and needs. Translation: they haven't fully figured out what they're building yet. The company is in discovery mode. They're talking to customers, understanding pain points, and planning to build something that addresses real problems in the market.

This is either smart or concerning, depending on how you look at it. Smart because it means Intel won't build something nobody wants. Concerning because the longer you take in this market, the further behind you fall.

Intel's broader strategy under Tan involves focusing on core businesses. But GPU manufacturing isn't some wild departure. It's a logical extension of their semiconductor expertise. They already design and manufacture processors. GPUs are processors, just with different architectures. For Intel, this is actually a relatively natural move, even if it's a new product category.

The Current GPU Market Landscape: Why Dominance Matters

Understanding Nvidia's dominance requires understanding what they've actually built and why it's so hard to displace.

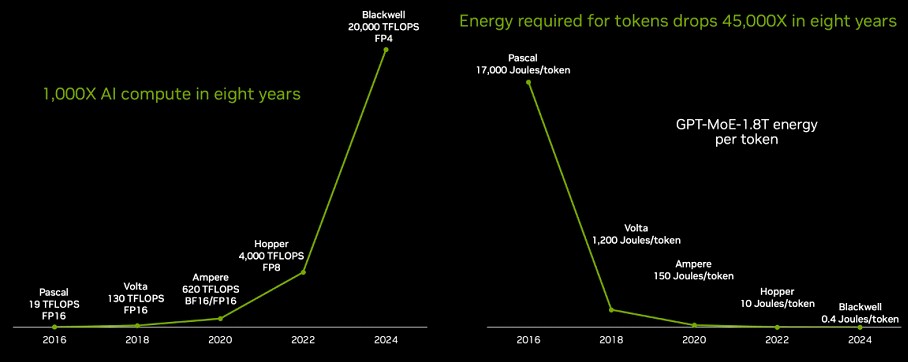

In AI accelerators, Nvidia's H100 and newer Blackwell chips are the gold standard. They're not just good because of raw performance specs. They're good because the entire AI development ecosystem is built on top of them. PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX, and every major machine learning framework has been optimized for Nvidia hardware over years of development.

When a researcher at OpenAI or Google trains a model, they're not thinking about the GPU. They're writing code that ultimately compiles down to CUDA, Nvidia's proprietary programming model. If you want to deploy that model somewhere else, you have to rewrite substantial portions of your code for different hardware.

This creates lock-in. Not through force, but through dependency. It's rational for customers to keep buying Nvidia because switching costs are enormous.

But market share alone doesn't capture the full picture. Let's look at the economics. Nvidia's gross margins on data center products are somewhere in the 70% range. Maybe higher. They're selling chips that cost a few thousand dollars to manufacture for

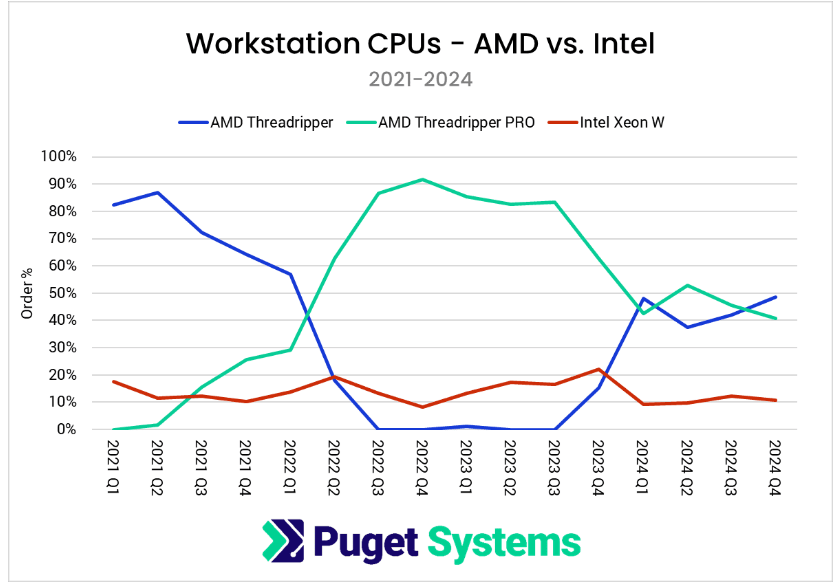

AMD has been trying for years. They've built EPYC processors that are genuinely competitive with Nvidia's CPUs. They've built MI300 accelerators that perform well on paper. But AMD has struggled to gain market share in accelerators because of the CUDA problem. Customers say they want competition. When the choice comes down to switching costs versus continuing with Nvidia, they choose Nvidia.

Google has built TPUs, their custom AI accelerators, because they're big enough to internalize development costs and they control their own workloads. But Google's TPUs never became a product for external customers in the way Nvidia's GPUs did.

This is the mountain Intel has to climb. Not just building competitive hardware, but building a software ecosystem that developers want to use and building up enough customer inertia to make switching worthwhile.

Nvidia dominates the AI accelerator market with an estimated 70% share, largely due to ecosystem lock-in and high switching costs. Estimated data.

The Strategic Challenge: Why Timing Might Matter More Than Technology

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough: timing in markets like this is everything.

When Nvidia started building CUDA in the mid-2000s, they were investing heavily in a market that didn't really exist yet. The risk was enormous. But they were patient. They spent years building relationships with researchers, providing tools, creating educational resources. By the time AI exploded, they had an installed base and ecosystem that made them the obvious choice.

Intel is entering this market after the explosion has already happened. Nvidia's fortress is fully built. They've got billions in annual revenue flowing in. They can invest in R&D faster than any competitor. They can lower prices if threatened. They can do aggressive bundle deals. They can acquire startups that threaten them.

The advantage Intel has is resources and manufacturing capability. Intel can actually build chips at scale. They've got fabs. They've got experience manufacturing complex semiconductors. This is not nothing.

But here's the timing problem: Intel also has to fix their core CPU business. They're losing server market share to AMD. Their client processor business is under pressure. Their 7nm process technology is behind TSMC's. While Intel invests in GPUs, they're dividing attention and resources across multiple struggling initiatives.

Nvidia, meanwhile, can focus entirely on GPUs. They have TSMC manufacturing their chips. They don't have legacy businesses to maintain. This focus advantage is significant.

The real question is whether Intel can sustain GPU development long enough to build a competitive product and ecosystem, or whether they'll get pulled back to fighting fires in their core business before they achieve meaningful traction.

Technical Architecture: Where Intel Might Actually Compete

Let's think about where Intel could theoretically build competitive advantages.

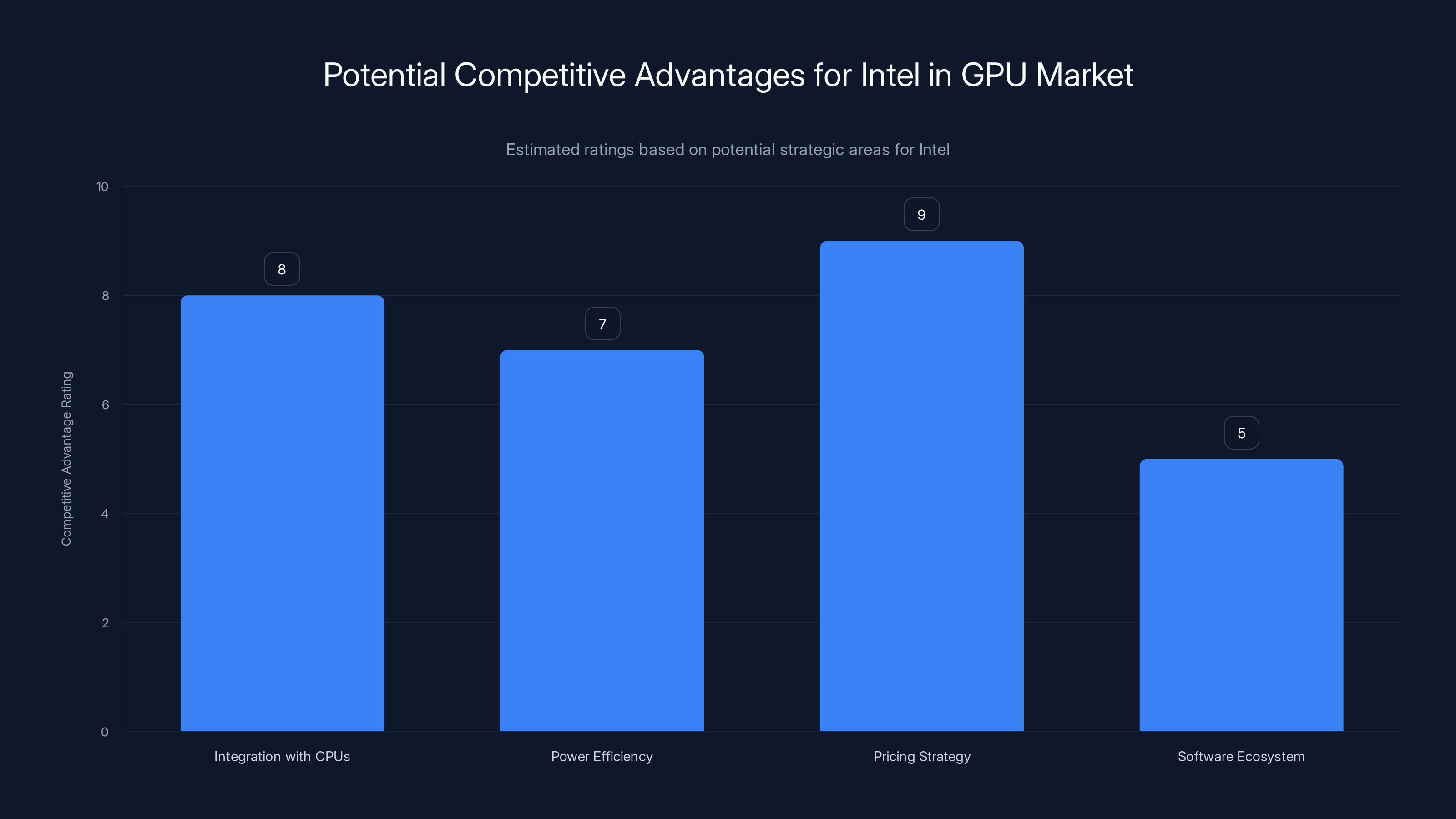

One interesting angle is integration. Intel manufactures CPUs. If they could build GPUs that integrate seamlessly with Intel CPUs, with optimized interconnect and memory coherency, they could potentially offer something Nvidia can't. Customers who are heavily invested in Intel infrastructure might prefer a unified solution.

Another angle is power efficiency. Nvidia's latest chips are incredibly capable but also power-hungry. The H100 consumes around 700 watts. Newer Blackwell chips push power consumption even higher. This creates costs beyond the chip itself. You need power delivery, cooling, data center infrastructure designed for extreme power density. If Intel could build something 30-40% more efficient for certain workloads, that becomes economically meaningful.

There's also the price angle. Nvidia's chips command premium prices because of demand and limited supply. If Intel could undercut them on price while delivering 80-90% of the performance, they'd get traction in price-sensitive segments. Not every organization needs the absolute peak performance. Some would happily trade 10% performance for 30% cost savings.

Software is the wild card. Intel could theoretically build tools and frameworks that make programming their GPUs easier or more intuitive than CUDA. This is extraordinarily hard because CUDA has a 15-year head start. But it's not technically impossible.

The most realistic scenario is that Intel builds something competent but not revolutionary. They compete on price and integration with Intel CPUs. They build ecosystem support through open standards and partnerships. They don't displace Nvidia in the core market, but they carve out niches where their advantages matter.

Nvidia's Ecosystem Moat: The Real Barrier to Entry

When people talk about why Nvidia's dominance is so hard to break, they usually focus on performance. But the real moat is ecosystem.

CUDA is a programming model. It's an extension of C++ that lets developers write code optimized for Nvidia hardware. When you write CUDA code, you're essentially writing code that only runs efficiently on Nvidia GPUs. Developers can port it to other platforms, but they have to rewrite substantial portions.

Over the past 15 years, millions of lines of CUDA code have been written. Major open-source frameworks like TensorFlow have CUDA backends optimized specifically for Nvidia hardware. When someone builds a machine learning library, they usually optimize it for CUDA first, then port to other platforms as an afterthought.

This creates a network effect. The more code written for CUDA, the more valuable Nvidia hardware becomes. The more valuable Nvidia hardware becomes, the more developers choose to write CUDA code. The cycle reinforces itself.

Breaking this requires an alternative ecosystem that's genuinely better or at least good enough to offset the switching costs. AMD's ROCm framework is technically solid, but it's got fragmentation and adoption challenges. It's also built on top of HIP, a different abstraction layer, which means porting CUDA code requires real work.

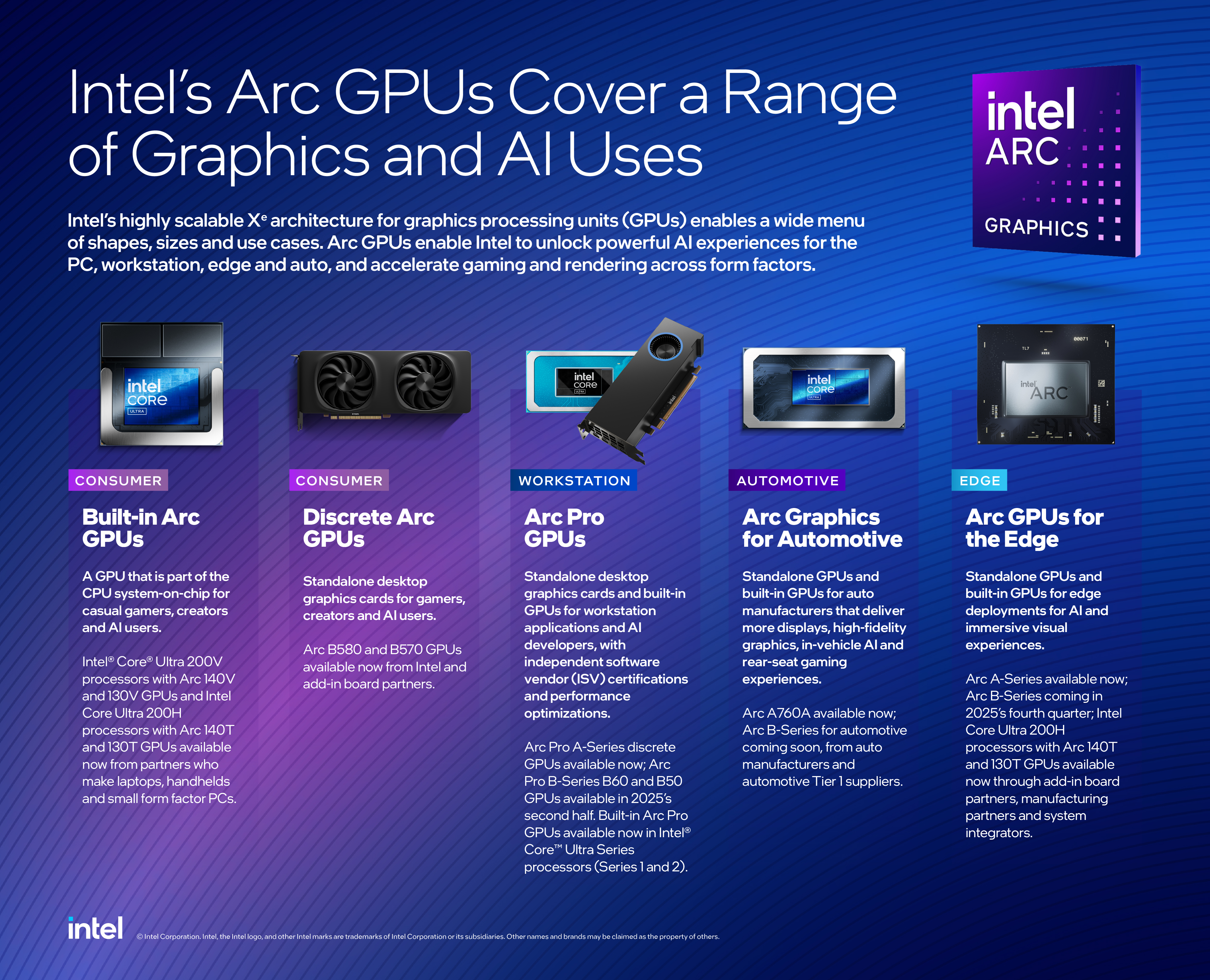

Intel would need to build something similar. Let's call it Arc or something catchier. They'd need it to be genuinely easier to work with than CUDA, or at least equivalent. They'd need to fund development of major frameworks to ensure Arc backends exist and are competitive. They'd need to subsidize early adopters to build the initial user base.

This is a 5-to-10-year commitment minimum, requiring billions in investment with uncertain returns.

Intel's potential to compete in the GPU market may hinge on integration with CPUs and pricing strategies, where they could offer significant advantages. Estimated data.

Market Segmentation: Where Intel Could Actually Gain Traction

If Intel is smart, they won't try to out-Nvidia Nvidia in the general market. They'll identify segments where they have advantages and focus there.

Integrated CPU-GPU systems: Customers who want unified compute with optimized memory hierarchies and minimal data movement between CPU and GPU cores could prefer integrated Intel solutions. This matters for certain workload types.

Power-constrained environments: If Intel could build GPUs that deliver 85% of Nvidia's performance at 60% of the power, they'd win in data centers where power and cooling are bottlenecks. Not everywhere, but in certain deployments this is real.

Enterprise integration: Companies heavily invested in Intel infrastructure might prefer solutions that integrate tightly with their existing systems. This isn't a universal advantage, but it matters for some enterprise customers.

Specialized workloads: There are workload types where GPU architecture matters a lot. If Intel built GPUs optimized for specific applications like recommendation systems, computer vision, or edge inference, they could win in those niches.

Open standards push: If Intel championed open standards and open-source frameworks instead of proprietary ecosystems, they could appeal to customers tired of Nvidia's closed approach. This is an undervalued angle.

The key insight is that Intel doesn't need to win the general market to be successful. They just need to establish meaningful presence in segments where their unique advantages matter.

The Manufacturing Advantage: Intel's Underrated Asset

People often overlook that Intel actually has significant manufacturing advantages compared to Nvidia.

Nvidia doesn't own any fabs. They design chips and contract with TSMC for manufacturing. TSMC is incredibly good, but they're also serving Samsung, Qualcomm, Apple, AMD, and hundreds of other companies. Your access to cutting-edge nodes depends on negotiating power, volume commitments, and pricing.

Intel owns fabs. They manufacture their own chips. This gives them control over their supply chain and access to their own manufacturing capacity. For a company trying to scale GPU production, this is genuinely valuable.

Now, Intel's recent fabs have had yield and performance issues. That's real. But they're investing billions in new manufacturing capacity and improving yields. If they get their manufacturing to world-class levels, they gain an advantage.

Manufacturing control also allows for customization. Intel could build variants of their GPUs optimized for specific applications. They could potentially offer better SLAs and reliability guarantees because they control the entire supply chain.

The constraint is capital intensity. Intel has to invest enormous sums in fab infrastructure. Nvidia can allocate profits directly to R&D without fab expenses. But if Intel treats manufacturing as a strategic asset rather than just a cost center, it becomes an advantage.

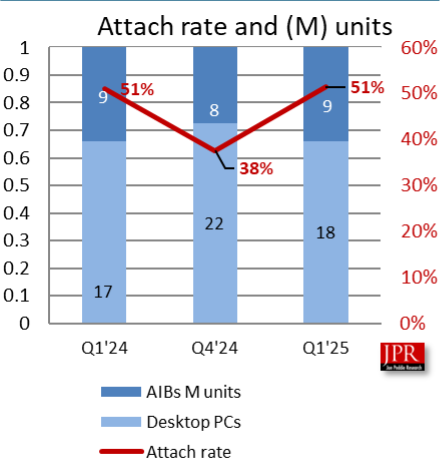

Customer Reaction: What AI Developers Actually Think

I've talked to folks working in AI infrastructure at various companies. The sentiment is surprisingly consistent: they want alternatives to Nvidia, but the switching costs are real.

Some companies are experimenting with AMD's MI300. Some are looking at Google's TPUs for specific workloads. Some are building custom silicon internally. But nobody's switching their entire infrastructure away from Nvidia anytime soon.

Why? Because the cost of rewriting code, retraining teams, rebuilding pipelines, and potentially accepting performance regressions is enormous. A CTO has to justify that cost to their board. Even if AMD or Intel chips are slightly cheaper, the total cost of ownership often favors staying with Nvidia.

But there's an opening for Intel. New teams starting greenfield infrastructure development might choose differently. Organizations building new product lines might be willing to experiment. Large enterprises might be willing to diversify GPU vendors as a hedge against supply chain risk.

Intel's real advantage is that they're Intel. They have relationships with major enterprises. They have brand credibility in data centers. When Intel says "we're building GPUs," enterprises take it seriously. They'll test the hardware, evaluate the software, and consider it seriously in their procurement decisions.

This is a massive advantage over AMD in terms of sales and distribution.

Nvidia currently dominates the GPU market with an 88% share. Intel's entry is projected to capture an estimated 5% initially, challenging Nvidia's dominance. (Estimated data)

The CUDA Problem: Intel's Biggest Obstacle

Let's be direct about this: software is Intel's biggest challenge.

They need to either build a CUDA killer or find a way to work with CUDA. Building a killer is nearly impossible because CUDA has been developed for 15 years. You can't catch up in software in 5 years. Open standards exist, but they're fragmented and adoption is slow.

Working with CUDA means supporting code written for Nvidia hardware on Intel hardware. This is technically possible. You can build compatibility layers. You can create tools that translate CUDA code. But translations are never perfect, and they often introduce performance regressions.

AMD has been trying to crack this with HIP and various translation tools. It works for some cases but not all. Performance is often inconsistent.

Intel could potentially take a different approach: build tools for more open frameworks. TensorFlow and PyTorch both support multiple backends. If Intel invests heavily in optimized PyTorch backends, they're getting code written in a platform-agnostic way that could run on Intel hardware.

This is less attractive than CUDA dominance, but it's more realistic.

Timeline and Realistic Expectations

Let's talk about when Intel might actually have competitive products available.

Tan said the company is developing strategy around customer needs. Translation: GPUs are probably 18-24 months away from tape-out. Another 6-12 months for early samples and validation. Maybe 24-36 months before volume production.

So we're probably talking 2028 at earliest for meaningful Intel GPU shipping in volume. That's two more years of Nvidia dominance, two more years of ecosystem development, two more years of customer entrenchment.

When Intel chips do arrive, they'll probably be competitive but not revolutionary. First-generation products are rarely revolutionary. They'll probably perform at 80-90% of equivalent Nvidia hardware. They'll probably be cheaper. They'll probably lack the mature ecosystem.

The real question is whether Intel's second and third-generation products can close the gap. If Intel commits to the business long-term, invests in software, supports developers, and iterates aggressively, they could eventually build a credible alternative.

But this requires patience. Intel's shareholders are used to faster returns. The question is whether the company can sustain investment in a market where returns are uncertain and timelines are long.

AMD's Shadow: What Intel Can Learn

AMD's experience with MI300 offers lessons for Intel.

AMD built genuinely competitive hardware. MI300 performs well. It's cheaper than equivalent Nvidia products. But adoption has been slower than expected. Why? Partly because of CUDA. Partly because customers are risk-averse and prefer proven technology. Partly because switching takes time and investment.

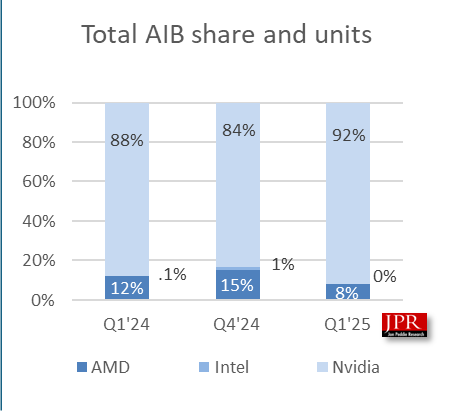

AMD has made progress, but they're still in single-digit market share for accelerators while Nvidia dominates.

The lesson for Intel is that hardware alone won't win this market. You need software, ecosystem, customer relationships, and patience. You need to accept that your first products won't immediately displace Nvidia.

But AMD also shows that it's possible to gain traction. AMD has won some customers who explicitly chose them over Nvidia. As time goes on, more will follow, particularly if AMD continues to improve hardware and software.

Intel probably has a higher ceiling than AMD because of relationships and manufacturing advantage. But they'll likely follow a similar trajectory.

Estimated data shows Nvidia likely maintaining dominance, but Intel and AMD could gain significant market share if they execute well. Scenario 1 and 2 are most probable.

Strategic Implications for the Broader Industry

Intel's GPU move has implications beyond Intel itself.

For Nvidia, it signals that their dominance might face sustained competitive pressure. One company challenging is manageable. Multiple companies challenging is a market dynamic Nvidia has to take seriously. This might drive Nvidia to accelerate innovation, lower prices, or expand ecosystem support to widen their moat.

For AMD, Intel's entry changes the competitive landscape. Previously, AMD was the main challenger. Now they'll compete against each other while both chase Nvidia. This could fragment the alternatives market or lead to consolidation.

For customers, more competition should be good. It means more innovation, better pricing, and more choices. But it also means more fragmentation and more difficult procurement decisions.

For the broader semiconductor industry, it suggests that major companies see GPU markets as strategically important enough to invest in, even with uncertain returns. We might see more entrants. Microsoft has been building custom AI accelerators. Apple has been building accelerators for on-device AI. Companies with sufficient capital and technical expertise are all looking at this space.

This could eventually create a more diverse ecosystem where no single company has 88% market share. That would be healthy for competition, even if it's less profitable for Nvidia.

What Intel Needs to Actually Win

Let's be concrete about what Intel needs to execute:

First, they need competitive hardware. This means performance, power efficiency, and reliability that approaches Nvidia's standards. Eighty percent of Nvidia's performance is a baseline. Ninety percent is better. Anything less and they won't get serious evaluation.

Second, they need software ecosystem. This means building frameworks, compilers, libraries, and tools that make programming Intel GPUs as easy as possible. This likely means supporting open standards like OpenCL or HIP, and building excellent backends for major frameworks like PyTorch.

Third, they need developer relations. Hire developer advocates, fund open-source projects, provide documentation, offer grants to researchers who use Intel hardware. Nvidia spent years building relationships. Intel can compress this timeline with resources, but they still need intentional effort.

Fourth, they need customer engagement. Work with enterprise customers early, understand their requirements, build solutions tailored to their needs. Don't just build generic chips and hope customers want them.

Fifth, they need realistic messaging. Intel needs to acknowledge that they're not the default choice right now. Position as an alternative, a hedge against supply chain risk, a solution for specific workloads. Don't claim superiority that isn't there yet.

Sixth, they need sustained investment. This isn't a 3-year project. This is a 10-year commitment minimum. Shareholders need to understand this, otherwise pressure for returns will force cancellation before success is possible.

The Competitive Dynamics: How Nvidia Might Respond

Nvidia won't sit passively while Intel enters the market. They'll take aggressive action to maintain dominance.

First, they'll likely lower prices on certain products, particularly in segments where Intel gains traction. Nvidia can afford to lower margins in specific areas while maintaining profitability on higher-end products.

Second, they'll accelerate innovation. Nvidia invests about 30% of revenue in R&D. They can push this higher if needed. More frequent product cycles mean Intel always feels behind.

Third, they'll expand software capabilities. CuDNN, TensorRT, and other Nvidia software become even more critical to their ecosystem. They'll enhance these aggressively.

Fourth, they'll pursue strategic acquisitions. If a software startup threatens to become a bottleneck for competitors, Nvidia might buy them.

Fifth, they'll invest in customer relationships. The sales and marketing push will intensify. Nvidia will do everything possible to make switching to competitors expensive and risky.

None of this is sinister. This is just normal competitive response. But it means Intel is walking into a fight where the incumbent has enormous resources and no intention of ceding market share.

Estimated data shows Nvidia's data center revenue overtaking gaming revenue around 2019, reaching 80% by 2024.

The Long-Term Vision: Where This Might Lead

If we zoom out and think about the next 10 years, several scenarios are plausible:

Scenario 1 (Nvidia continues dominance): Intel's GPU effort underperforms expectations. It takes longer than planned, products underdeliver on promises, and ecosystem adoption lags. Nvidia maintains 80%+ market share. AMD and Intel stay in single-digit market share. This is the most likely scenario based on historical patterns.

Scenario 2 (Modest consolidation): Intel's GPU effort is moderately successful. They gain 10-15% market share, mostly from customer diversification, enterprise hedging, and niche workloads. AMD also gains a few more points. Nvidia drops to maybe 70-75% but remains clearly dominant. This is realistically possible if Intel executes well.

Scenario 3 (Real competition): Intel's third or fourth generation GPUs become genuinely compelling. They approach Nvidia's performance, achieve 80%+ feature parity, and build a vibrant ecosystem. This catalyzes broader ecosystem development and open standards adoption. Market share becomes contested. This would take 8-12 years and requires Intel to execute at a high level consistently.

Scenario 4 (Market fractures): Open standards improve, software translation tools become sophisticated, and customers get comfortable using heterogeneous hardware. The market fragments across multiple players. Nvidia retains 40-50% but it's genuinely competitive. This seems less likely in the near term but possible long-term.

Most likely, we'll see Scenario 1 or Scenario 2. Intel will make genuine progress but won't threaten Nvidia's overall dominance within the next 5-7 years. Longer term, competition might become more real as alternative ecosystems mature.

The Human Factor: Leadership and Execution Risk

Tech industry outcomes aren't determined by strategy alone. They're determined by execution, which depends heavily on people and culture.

Lip-Bu Tan, Intel's new CEO, seems committed to this direction. He's brought in experienced engineers like Kevork Kechichian and Eric Demmers. That signals seriousness.

But Intel also has a history of pursuing technologies that didn't pan out. The company has tremendous engineering talent but sometimes struggles with execution speed and decisiveness. They've got organizational complexity that can slow decision-making.

Nvidia, by contrast, has relatively lean decision-making. They can move fast. They have a culture of aggressive innovation. This cultural advantage is real and hard to overcome.

For Intel to win in GPUs, they need to not just hire great engineers but build a GPU business unit with autonomy, aggressive targets, and freedom to move fast. They need to hire engineering leaders from outside who bring GPU expertise and culture. They need to shield this unit from some of Intel's slower organizational pressures.

This is organizationally difficult for a large company. But it's not impossible if leadership commits to it.

Investment Implications and Market Impact

Intel's GPU move has implications for investors and industry observers.

For Intel stock, this is a mixed signal. On one hand, it shows the company is thinking strategically about future markets. On the other hand, it's a huge investment in an uncertain market. Investors had to weigh growth ambitions against near-term profitability.

For Nvidia, Intel's entry is theoretically concerning but probably won't materially impact stock in the near term. Nvidia's dominance is durable. Even with competitors, they're generating enormous cash flows. But long-term, new competition could eventually moderate growth rates.

For AMD, Intel's entry is actually competitive risk. AMD has been building its position in accelerators. Now they compete against Intel as well as Nvidia. This could pressure AMD's roadmap and force faster innovation.

For the broader semiconductor market, Intel's move suggests consolidation around specialized products. Companies need deep expertise and resources to compete. This might eventually lead to fewer major players, not more.

Final Assessment: The Realistic Outlook

Let's be honest about what Intel's GPU effort means.

It's not going to displace Nvidia in the next 5 years. That's just not realistic given Nvidia's lead, ecosystem dominance, and financial resources.

But it could be meaningful and valuable even without displacing Nvidia. Intel could build a credible alternative that serves 10-15% of the market. They could become the choice for customers who want geographic diversity of suppliers, who want integration with Intel CPUs, or who are building new infrastructure where switching costs are minimal.

This wouldn't be revolutionary. But it would be significant for customers who want choices and good for the industry that benefits from competition.

The real question is whether Intel can stick with this long enough. If they commit genuinely for 10 years, they can build something substantial. If they get impatient and pivot in 3-4 years when returns aren't immediate, they'll fail.

Given Intel's history, I'd estimate 50-60% probability they execute well enough to achieve modest success. 30-40% probability they struggle with execution and underperform. 10-15% probability they become a genuine competitive threat to Nvidia.

But even modest success would be meaningful for the industry and for customers seeking alternatives. That's worth the investment, assuming Intel stays committed.

FAQ

What exactly is a GPU and why does it matter for AI?

A GPU (graphics processing unit) is a specialized processor designed to perform many calculations simultaneously in parallel. Unlike CPUs which excel at sequential, complex tasks, GPUs excel at handling thousands of simple calculations at the same time. This parallel architecture is perfect for AI and machine learning because neural networks essentially involve multiplying enormous matrices together. A GPU can perform these operations orders of magnitude faster than a traditional CPU, which is why AI training and inference has become GPU-centric.

Why has Nvidia dominated the GPU market so thoroughly?

Nvidia's dominance stems from multiple reinforcing advantages. First, they developed CUDA, a programming framework that made writing GPU-optimized code accessible to developers. Second, they invested years in developer relations and educational programs before the AI boom. Third, they built a massive ecosystem of libraries, frameworks, and tools optimized specifically for Nvidia hardware. Fourth, they understood early that deep learning was the future and invested accordingly. By the time AI exploded as a market, Nvidia had an eight-year head start that competitors still haven't overcome.

Can Intel actually compete with Nvidia in GPUs?

Intel can compete and build meaningful market share, but displacing Nvidia entirely in the near term is unrealistic. Intel has advantages like manufacturing control and customer relationships, but disadvantages in software ecosystem and ecosystem lock-in. Realistically, Intel could capture 10-15% market share over the next decade if they execute well, particularly in enterprise and specialized workload segments. This would be meaningful but wouldn't threaten Nvidia's overall dominance.

What's the timeline for Intel's competitive GPUs?

Based on Intel's announcements, competitive products are probably 2-3 years away from tape-out, with volume production arriving around 2028 at earliest. First-generation products will likely perform at 80-90% of equivalent Nvidia products and lack mature ecosystem support. Subsequent generations could close gaps further, but this is a multi-year journey, not something that happens overnight.

Why does software matter more than hardware in this competition?

Because developers care more about what they can do with the hardware than the hardware specifications. Nvidia's CUDA ecosystem means developers can write code once and it runs efficiently on Nvidia GPUs. Code written for Nvidia hardware doesn't automatically work on AMD or Intel hardware without substantial rewriting. This creates stickiness that makes switching costs enormous. If Intel can address software through excellent PyTorch support or other frameworks, they improve their competitive position significantly.

What would need to happen for Intel to actually threaten Nvidia's dominance?

Several things would need to align: Intel's third or fourth-generation GPUs would need to achieve 95%+ performance parity with Nvidia equivalents. Open standards would need to mature enough that developers aren't locked into proprietary ecosystems. The software tools and frameworks for Intel GPUs would need to be genuinely good, not just acceptable. Enterprise customers would need to accept heterogeneous GPU deployments rather than standardizing on single vendors. All of this is possible but requires consistent execution over 8-12 years.

How does this affect GPU prices and availability?

More competition theoretically benefits customers through lower prices and more supply options. In practice, Nvidia has managed to maintain or increase prices even as competitors gained presence, because demand remains so strong. Intel's entry could eventually moderate price increases or create specific segments with more competitive pricing. It's unlikely to dramatically crash GPU prices because demand for AI accelerators far exceeds supply regardless.

Should enterprises prefer Intel GPUs over Nvidia?

Not yet, and probably not for several years. Nvidia products are proven, mature, and have comprehensive ecosystem support. Intel's products will be newer with less mature software and less proven reliability. However, some enterprises might choose to experiment with Intel hardware in non-critical applications, or deliberately diversify suppliers as a hedge against concentration risk. Both are reasonable strategies that don't require Intel to be superior, just acceptable.

What about AMD's role in this competition?

AMD has been building MI-series accelerators for years with moderate success. Intel's entry creates three-way competition rather than two-way. This is good for customers but could fragment the alternatives market. AMD and Intel might actually compete more intensely against each other than against Nvidia in certain segments. Ultimately, AMD probably benefits from having another company investing billions to break into the market, even if it's a competitor.

How does Intel's CPU business factor into their GPU strategy?

Intel's most realistic advantage is building integrated CPU-GPU systems where they control both components and can optimize the interface between them. This could appeal to customers who want unified computing solutions. However, this advantage only matters for workloads where CPU and GPU work closely together. For pure GPU-accelerated work, this integration doesn't provide much advantage.

Conclusion: The Long Game Begins

Intel's entry into GPU manufacturing is significant, but not revolutionary. The company isn't claiming they'll dethrone Nvidia next year. They're saying they're committing to competing in a market they recognize as strategically important.

This matters for several reasons. First, it validates that GPU accelerators are the future of computing, not just an AI fad. If Intel sees enough long-term potential to invest billions, that's a signal to the broader industry.

Second, it suggests that Nvidia's dominance, while durable, isn't permanent. Markets always eventually see competitors emerge. The question is whether Intel can execute well enough to become a meaningful competitor or whether they'll be a minor player in Nvidia's shadow.

Third, it opens possibilities for customers who've been frustrated with Nvidia's market position. More options mean more negotiating leverage, more innovation incentives, and more opportunity to find solutions tailored to specific needs.

The most likely outcome is that Intel builds something moderately successful over the next decade. They capture meaningful market share in enterprise and specialized workloads. Nvidia remains dominant but with more competitive pressure. AMD gains some additional market share. The AI accelerator market becomes less of a monopoly and more of an oligopoly.

This isn't the dramatic disruption people often expect. It's the normal competitive dynamic that eventually materializes in every large market. Monopolies attract competitors. Competitors eventually gain traction. Markets mature into competitive landscapes where multiple players coexist.

Intel understands this better than most. They've dominated markets before and seen competitors emerge. They know the game. The question is whether they'll stay committed long enough to play it successfully.

Based on their leadership moves and the seriousness of their executive appointments, I'd say they probably will. But in tech, probably is never good enough. We'll know in 5-7 years whether Intel's GPU bet becomes a significant success, a moderate success, or an expensive failure.

Until then, Nvidia sleeps well knowing they've got a substantial head start and a fortress of ecosystem dominance that won't fall in any timeframe that matters to today's shareholders. But they're probably paying attention to Intel's moves more carefully than they admit.

That shift in attention, that forced vigilance against a new competitor, might be the most significant outcome of Intel's announcement. Markets evolve when leaders have to work to maintain their position rather than simply reaping the benefits of their dominance.

Intel is betting that working will be worth the investment. Time will tell if they're right.

Key Takeaways

- Intel is committing billions to GPU manufacturing with new VP-level hires, signaling serious intent to compete in a market where Nvidia owns 88% share

- Nvidia's dominance isn't just about hardware—it's about CUDA ecosystem lock-in that took 15 years to build, creating switching costs that are extraordinarily difficult to overcome

- Intel's realistic advantage lies in specific segments: integrated CPU-GPU systems, power-constrained deployments, and enterprise customers seeking supply chain diversification—not general market displacement

- Timeline is critical: Intel's competitive GPUs probably won't arrive in volume before 2028, giving Nvidia 2+ more years to fortify dominance and extend their technological lead

- Even modest success (10-15% market share) would be meaningful for customers and healthy for competition, though displacing Nvidia's overall dominance within 10 years remains unlikely

Related Articles

- Microsoft's Maia 200 AI Chip Strategy: Why Nvidia Isn't Going Away [2025]

- NVIDIA's $100B OpenAI Investment: What the Deal Really Means [2025]

- MSI Prestige 14 Flip AI+ Review: Intel Panther Lake's Game-Changing Ultraportable [2025]

- AI Safety by Design: What Experts Predict for 2026 [2025]

- Enterprise AI Race: Multi-Model Strategy Reshapes Competition [2025]

- Shared Memory: The Missing Layer in AI Orchestration [2025]

![Intel's GPU Strategy: Can It Challenge Nvidia's Market Dominance? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/intel-s-gpu-strategy-can-it-challenge-nvidia-s-market-domina/image-1-1770154704736.jpg)