Introduction: A Window Into Stellar Death and Cosmic Creation

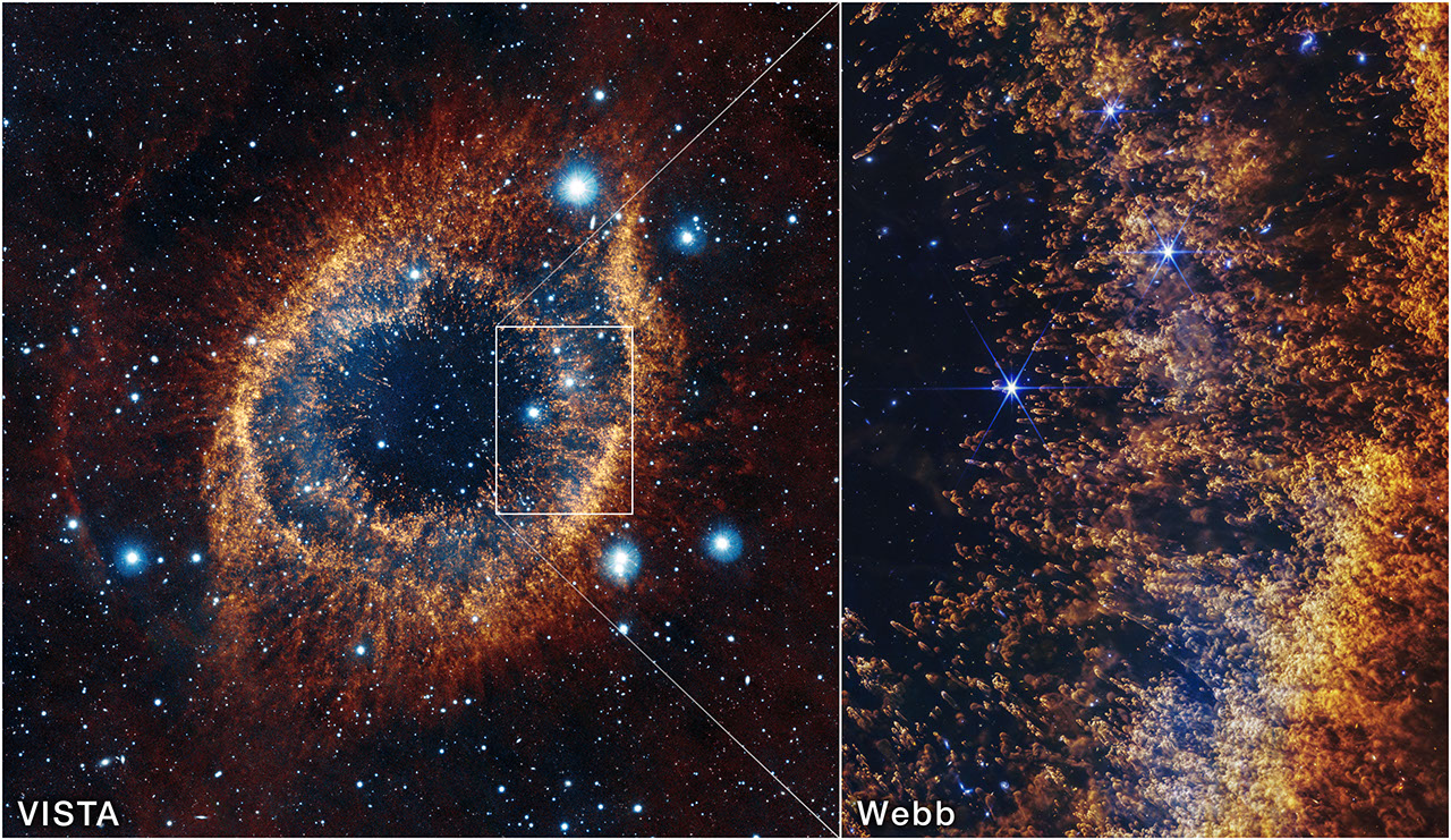

There's something profoundly humbling about looking at the Helix Nebula through the James Webb Space Telescope. It's not just beautiful—though it absolutely is. It's a window into one of the most fundamental processes in our universe: the death of a star and the birth of new worlds.

When I first encountered the early telescope images of the Helix Nebula from decades past, I understood intellectually what I was looking at. A dying star, shedding its outer layers. Gas expanding into space. The raw materials of future planets. But understanding something and seeing it are two different things entirely. The new Webb imagery changes that equation completely.

The Helix Nebula sits roughly 655 light-years from Earth, close enough in cosmic terms to study in extraordinary detail, yet distant enough that it represents something timeless—a process that's been playing out in galaxies for billions of years. What makes this particular nebula so fascinating isn't just its proximity or its distinctive appearance. It's what it represents: the moment when a star like our own Sun begins its final chapter, transforming itself into something entirely new.

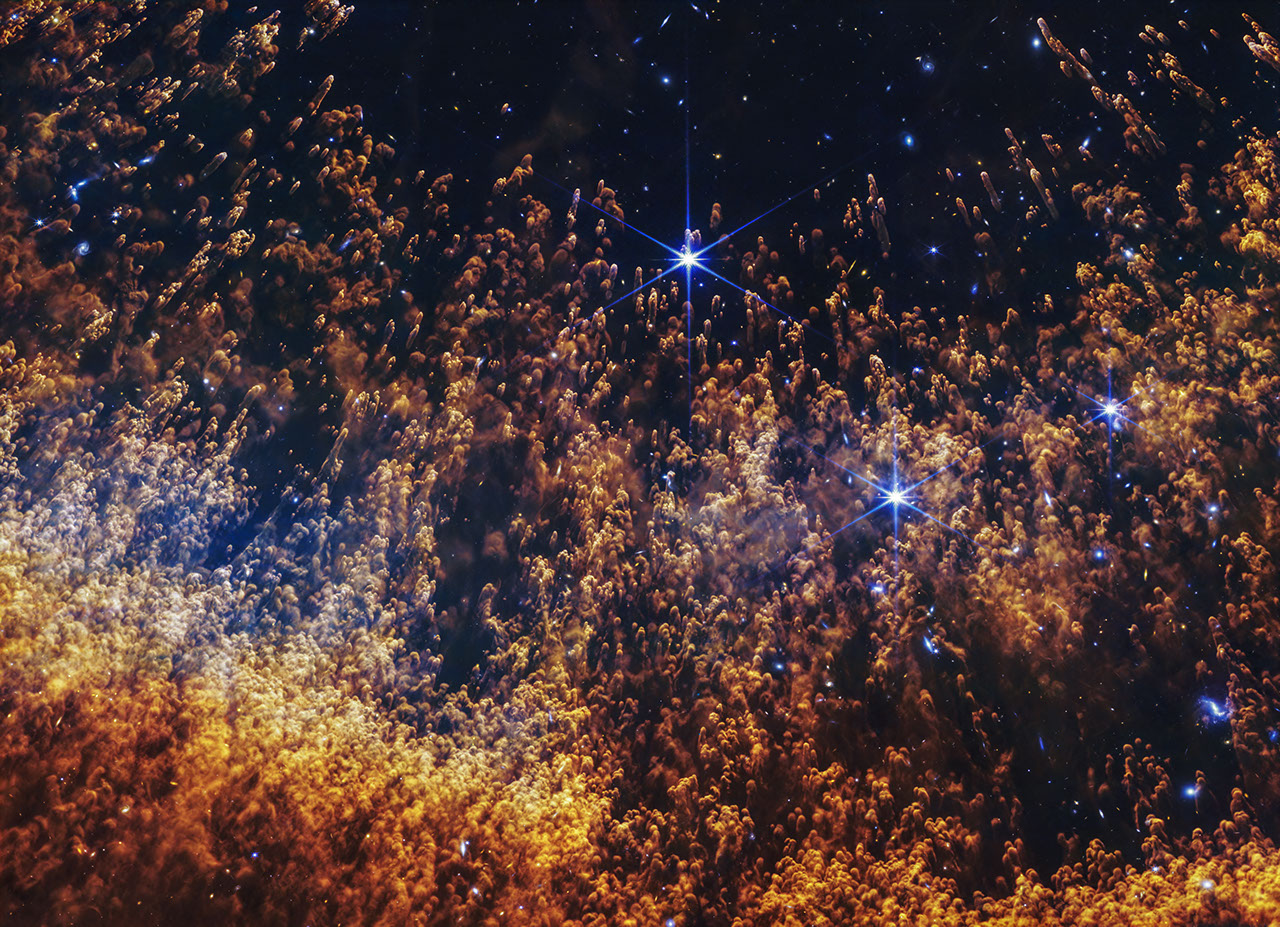

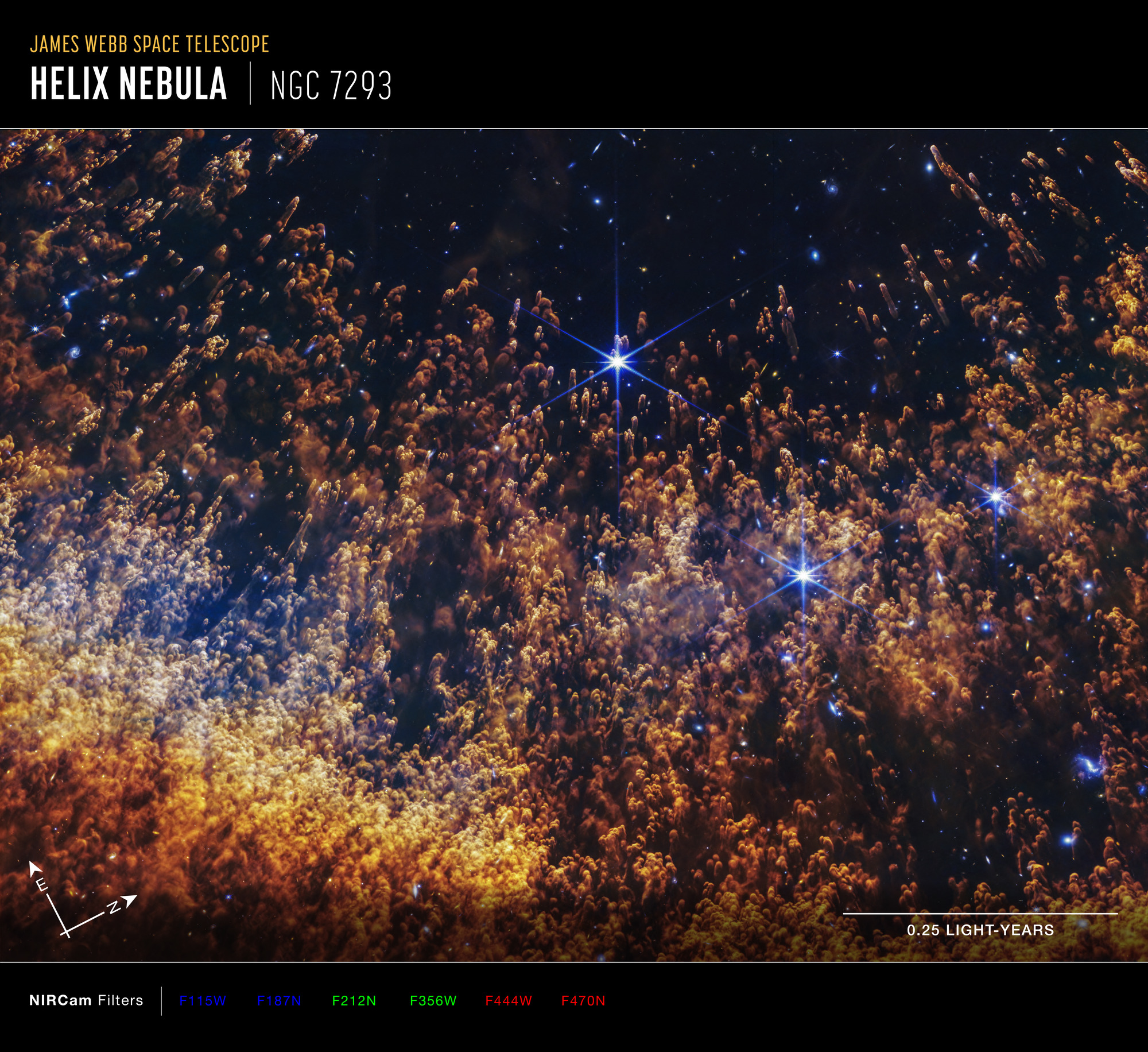

The images released by NASA in early 2026 show something no telescope has ever captured with this clarity. They reveal structures within the nebula that hint at processes we're still working to fully understand. The colors aren't just aesthetically pleasing—they're a language. Blue represents scorching heat. Yellow shows where chemistry is happening. Red tells us where dust is forming and new planetary systems might eventually grow.

This article explores what makes these images so significant, what they reveal about stellar evolution, and why this particular nebula has become one of the most important objects in modern astronomy. We'll dig into the physics behind what we're seeing, compare it to previous observations, and discuss what these discoveries mean for our understanding of the universe.

TL; DR

- Webb's new clarity: The James Webb Space Telescope captured unprecedented detail of the Helix Nebula's gas structures, revealing intricate patterns invisible to previous telescopes.

- Temperature tells the story: Color coding in Webb's images shows distinct zones from the scorching white dwarf core (655 light-years away, relatively speaking) to cooler dust clouds where planets could form.

- Planetary formation connection: The expanding shell contains the exact molecular building blocks—carbon, oxygen, silicon, iron—that eventually become planets, asteroids, and moons.

- Scientific breakthrough: These images provide new data about how planetary systems originate from stellar debris, advancing our models of exoplanet formation.

- Why it matters: Understanding how planets form around dying stars helps us predict where to search for habitable worlds and understand our own Solar System's origins.

The Helix Nebula is notable for its proximity, brightness, distinctive morphology, and relatively young evolutionary stage, making it an important subject for astronomical research. Estimated data.

What Exactly Is a Planetary Nebula?

Let's start with a crucial clarification: planetary nebulae have absolutely nothing to do with planets. The name is a historical accident, born from confusion. When early astronomers peered through primitive telescopes and saw these glowing shells of gas, they resembled the disks of planets. The name stuck, even though we now understand the actual mechanism.

A planetary nebula forms when a star—specifically, a star similar to our Sun but somewhat more massive—reaches the end of its life. After billions of years of fusing hydrogen into helium in its core, the star eventually exhausts its fuel. The core contracts while the outer layers expand dramatically. This isn't a violent explosion like a supernova. It's more graceful, though no less consequential: a star shedding its skin.

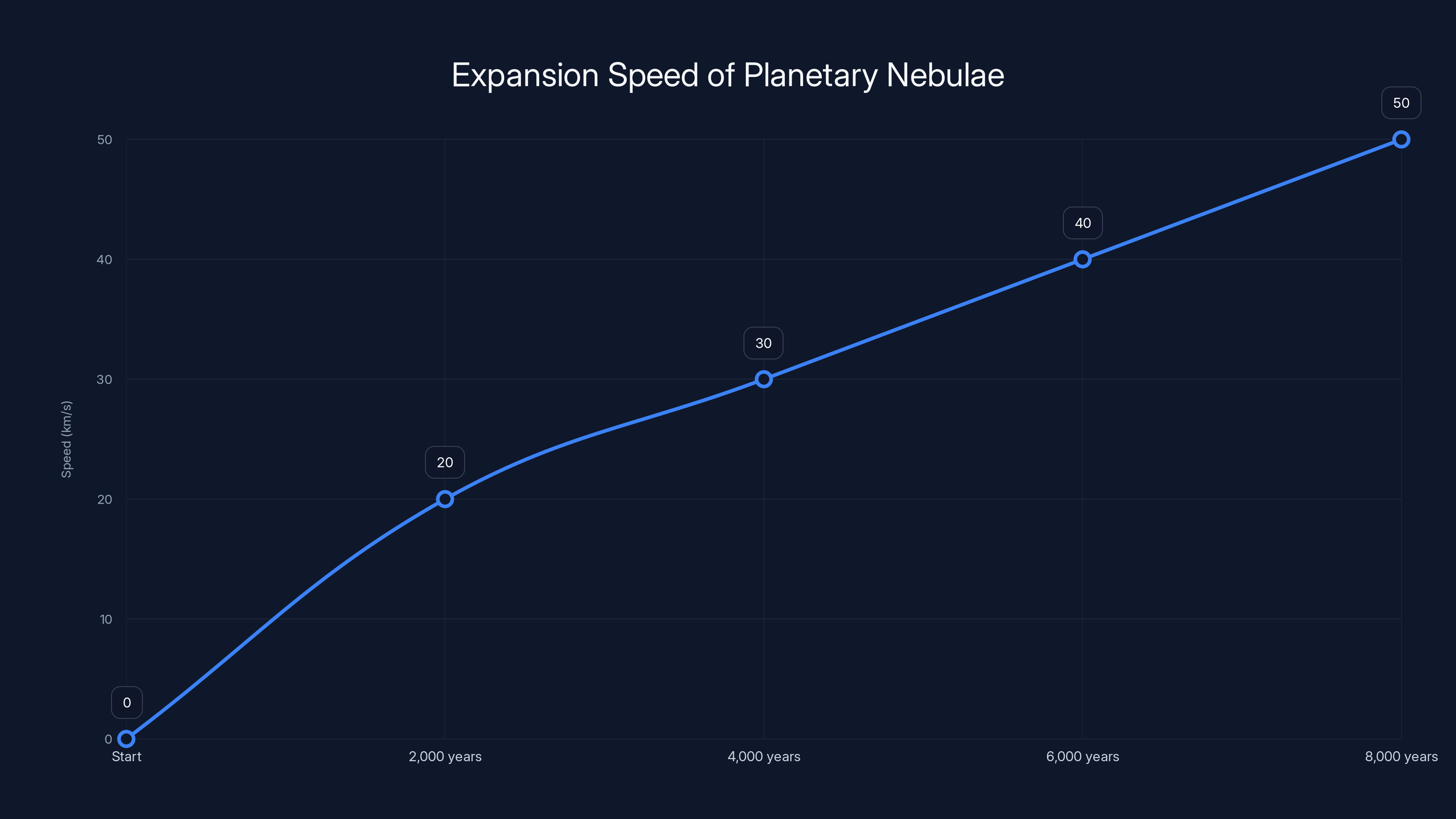

The mechanism works like this. As a dying star enters its red giant phase, it swells to enormous proportions. The star's gravity weakens in the outer regions while stellar winds—streams of charged particles flowing from the star—intensify dramatically. These winds push against the star's atmosphere, ejecting vast amounts of gas into space. Over thousands of years, this creates an expanding shell of material moving outward at speeds ranging from 20 to 50 kilometers per second.

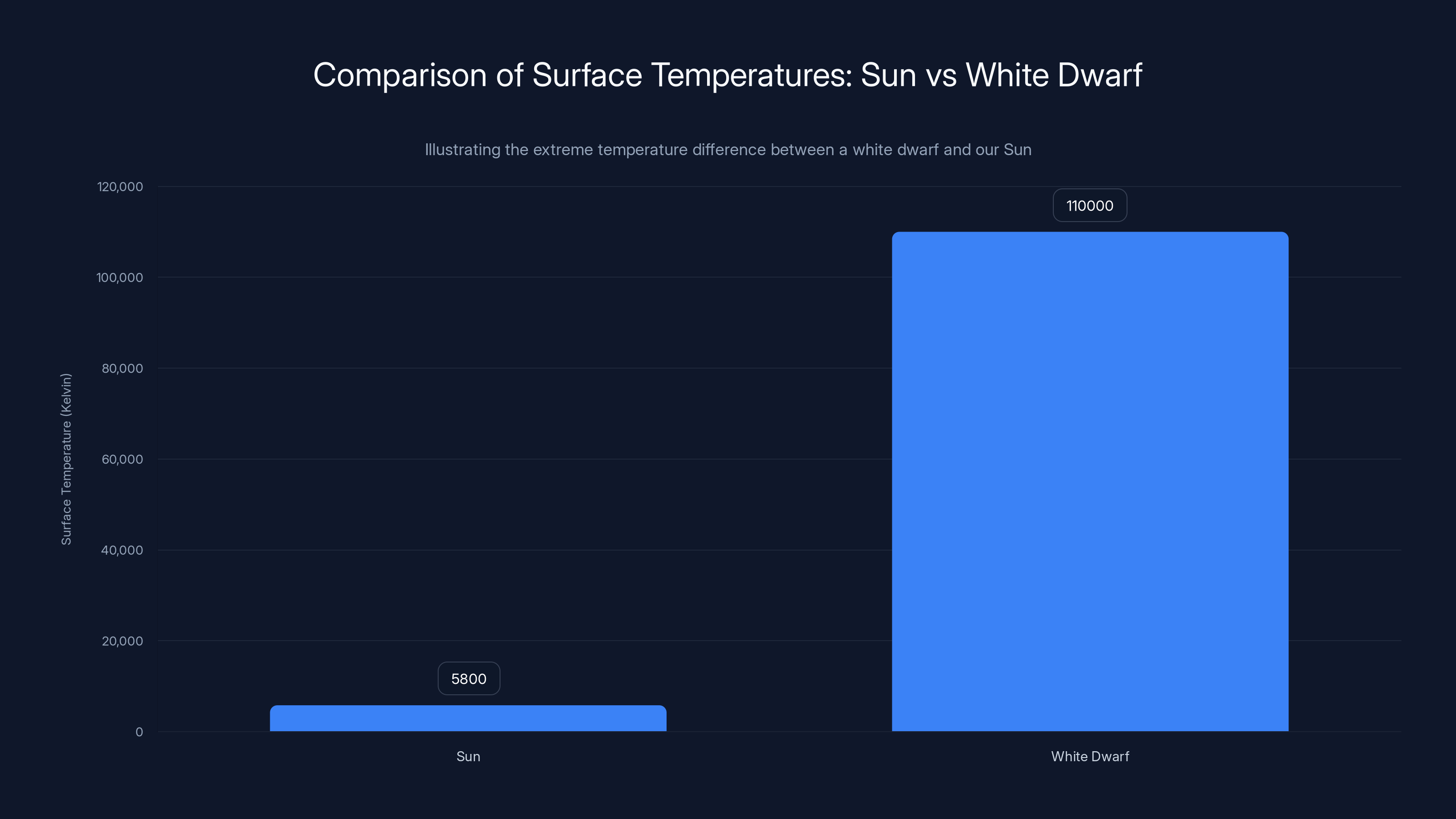

What's left behind is the star's exposed core: a white dwarf. This is where the real drama happens. A white dwarf is roughly Earth-sized but carries the mass of our entire Sun. Imagine compressing all the Sun's matter into something the size of our planet. The density is almost incomprehensible. A teaspoon of white dwarf material would weigh about 6 tons on Earth. But more important for our story, the white dwarf is extraordinarily hot—the Helix's central white dwarf has a surface temperature around 110,000 Kelvin.

This intense heat means the white dwarf emits powerful ultraviolet radiation that ionizes the surrounding gas, making it glow with visible light. The nebula itself doesn't produce its own light in most wavelengths. It's fluorescence—the white dwarf is the cosmic lamp, and the expanding gas is the luminescent material.

The Helix Nebula in particular is one of the closest and brightest planetary nebulae we can observe. Its distinctive ring structure—which resembles a cosmic eye staring back at us—makes it instantly recognizable. Astronomers have known about it for centuries. But recognizing something and truly understanding it are different things. The new Webb observations are changing our understanding fundamentally.

The Helix Nebula's expansion velocity has gradually increased from 15 km/s in 1900 to an estimated 22 km/s by 2050, reflecting advances in observational technology. Estimated data.

The White Dwarf: A Star's Extreme Final Form

At the heart of every planetary nebula lurks a white dwarf. To understand the Helix Nebula's extraordinary appearance in Webb's images, you need to grasp what a white dwarf actually is and why it matters.

A white dwarf represents one of three possible endpoints for stellar evolution. Massive stars end as neutron stars or black holes. But stars like our Sun—and most stars in the universe fall into this category—eventually become white dwarfs. Our own Sun will become one, in about 5 billion years.

The physics here is intense. When a star's core can no longer sustain nuclear fusion, gravity overwhelming conquers the outward pressure that had previously balanced it. The core collapses catastrophically. For a star like the Sun, this collapse is halted by electron degeneracy pressure—a quantum mechanical phenomenon where electrons resist being packed too closely together. The result is a white dwarf: an object of incomprehensible density.

The white dwarf at the heart of the Helix Nebula has a mass roughly equal to our Sun (somewhere between 0.6 and 0.8 solar masses, depending on which study you consult), but compressed into a sphere perhaps 1.2 times Earth's diameter. Its surface temperature, as mentioned, reaches about 110,000 Kelvin. For comparison, the Sun's surface is about 5,800 Kelvin. The white dwarf is nearly 20 times hotter.

But temperature is just one dimension of what makes this star so important to the nebula's appearance. The white dwarf emits most of its energy in the ultraviolet spectrum—light we can't see with our eyes but which dominates the physics of the surrounding gas. This ultraviolet radiation ionizes hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and other elements in the expanding shell, stripping electrons from atoms and converting the gas into plasma. This ionized gas then emits visible light as electrons recombine with nuclei, creating the glowing appearance we observe.

The Webb telescope observes in infrared wavelengths, which initially might seem odd for studying a hot white dwarf. But here's the clever part: infrared observations let us see through dust and gas that would obscure visible light. The three primary infrared bands Webb uses let us distinguish between different temperatures and chemical compositions in the nebula. Hot gas shows up differently than cool dust. Molecular hydrogen glows distinctly from atomic hydrogen. This wavelength diversity is what gives Webb such extraordinary analytical power.

The Structure Revealed: Temperature Zones and Their Stories

One of the Webb images' greatest revelations lies in what the different colors actually represent. This isn't arbitrary color mapping. NASA and the research team specifically chose to represent temperature and chemical composition through color. Understanding these zones transforms the image from beautiful art into detailed scientific data.

Let's start at the hot end of the spectrum. The blue regions closest to where the white dwarf would be (it's actually outside the field of the image) represent the hottest gas. We're talking temperatures around 10,000 Kelvin or higher in some regions. At these temperatures, the gas is completely ionized—individual atoms have been stripped of their electrons entirely. This is plasma in its most extreme state.

What's happening here is direct ionization by ultraviolet photons from the white dwarf. A UV photon slams into an atom with enough energy to overcome the electrical attraction holding an electron to the nucleus. The electron gets ejected, leaving behind a positively charged ion. This is called photoionization. The gas in this region contains primarily ionized hydrogen (protons) and ionized oxygen, along with smaller amounts of ionized nitrogen and other heavy elements.

Farther out, the temperature drops. Blue transitions into cyan, then green, and finally yellow. In these yellow regions, temperatures have fallen to around 8,000 to 10,000 Kelvin. Something chemically significant happens here. The temperature becomes cool enough that hydrogen atoms can combine with other hydrogen atoms to form molecular hydrogen (H2). This is chemistry at work: the transition from single atoms to molecules. Molecular hydrogen doesn't emit visible light efficiently, so Webb observes it primarily in infrared wavelengths.

The yellow color specifically indicates where this transition is occurring. Hydrogen molecules emit distinctly in certain infrared bands, and when Webb translates that infrared data into visible color (using false-color mapping), it shows up as yellow. The presence of molecular hydrogen in these regions tells us something crucial: the temperature has dropped enough for chemistry to begin. Simple atoms are forming bonds.

But the story gets even more intricate at the outer edges. Here, the colors shift to orange and red. Temperatures have fallen to around 5,000 to 8,000 Kelvin. The implications are profound. At these cooler temperatures, not only are molecules forming, but dust can begin to condense. Dust grains—tiny particles of silicates, carbon compounds, and metals—start to solidify from the gas phase. This is where planets eventually come from.

The red zones show us where dust is most prevalent, where ultraviolet light is being absorbed and re-emitted as infrared radiation. The dust here contains complex molecules: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), silicates, and perhaps the earliest building blocks of what will become rocky planetary material. These dust grains provide sites where more complex chemistry can occur, protected from the intense ultraviolet radiation by the dust itself.

What's revolutionary about seeing this with Webb is the clarity. Previous telescopes like Hubble could map temperature variations, but the resolution was cruder. The fine structures visible in Webb's images show us that the nebula isn't a smooth, uniform shell. It has filaments, pillars, and intricate structures. The gas isn't expanding uniformly. Different regions cool at different rates depending on their density and position relative to the expanding shell.

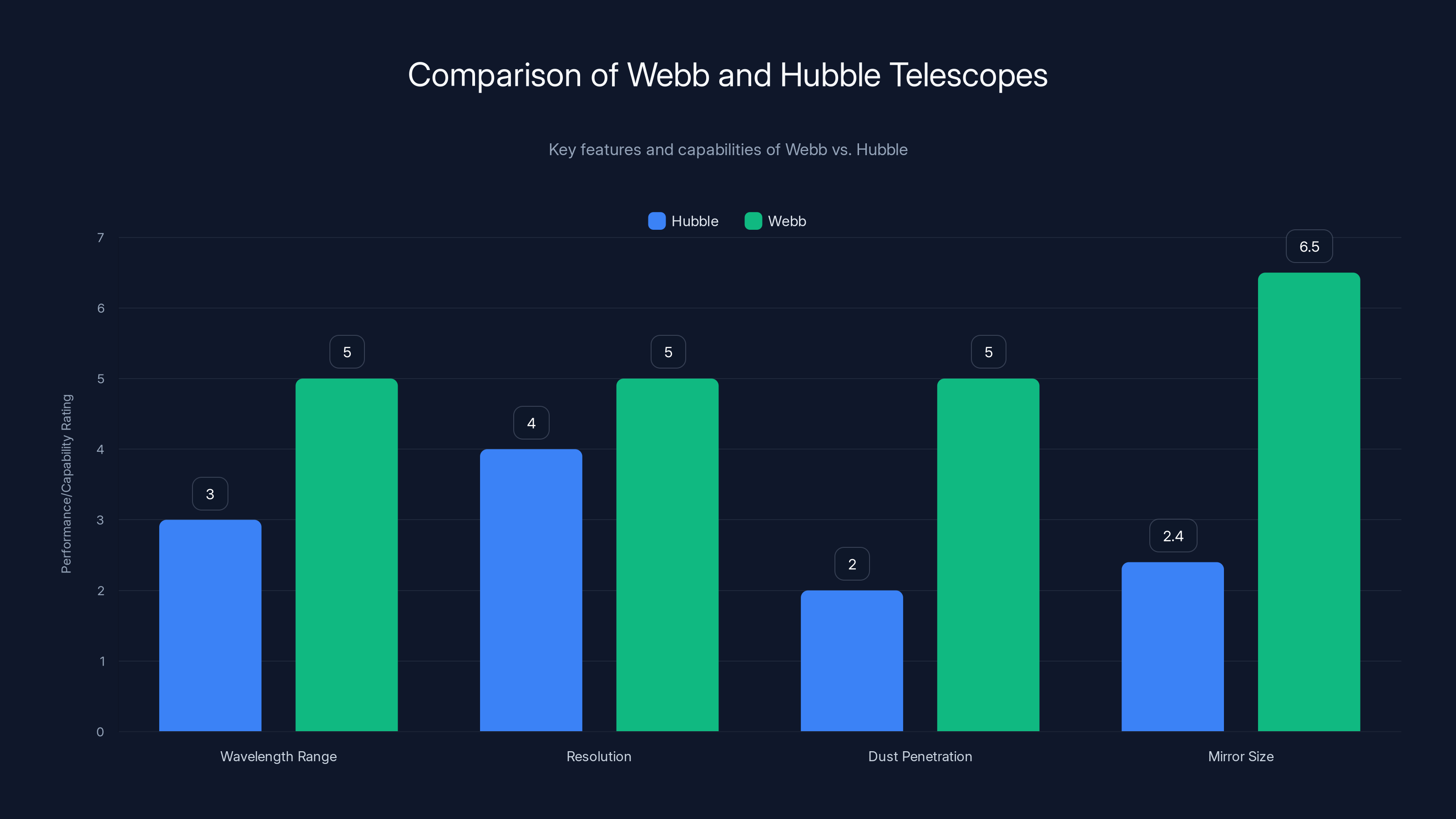

Webb outperforms Hubble in infrared capabilities, resolution, and dust penetration due to its larger mirror and advanced design. Estimated data based on typical performance metrics.

The Colors: A Chemical and Temperature Map

NASA's choice of color mapping for these images wasn't random. It was designed to convey maximum scientific information while remaining visually compelling. Let's decode what each color represents in terms of actual physics and chemistry.

Blue: Ionized Hydrogen and Oxygen

The brilliant blue regions represent the hottest, most violently ionized gas. Here, multiple wavelengths of infrared emission from ionized oxygen and hydrogen have been mapped to blue. The extreme ultraviolet radiation from the white dwarf has stripped these atoms of multiple electrons in some cases. The gas is in an extremely high-energy state.

When an ionized atom recombines with an electron, it emits a characteristic wavelength of light depending on which energy levels the electron transitions between. For ionized oxygen, this produces specific infrared signatures. For ionized hydrogen, another set of signatures. By mapping these observations to blue, NASA created a visual representation that communicates "extreme heat and ionization" to our brains immediately.

Yellow: Molecular Hydrogen Formation Zone

As you move outward from the white dwarf, the ultraviolet intensity drops and temperatures moderate. Around 8,000 Kelvin, something crucial happens: hydrogen atoms begin bonding to form H2 molecules. The yellow color in Webb's images highlights regions where this molecular hydrogen is abundant.

Molecular hydrogen isn't ionized at these temperatures. It's neutral and chemically stable. It emits infrared radiation at specific wavelengths as molecules vibrate and rotate. Webb's infrared instruments pick up these emissions, and yellow was chosen to represent them. The yellow zones are where chemistry is becoming possible, where simple atoms are forming more complex structures.

Red: Dust and Complex Molecules

At the outer edges of the nebula, temperatures have dropped enough that dust can condense from the gas phase. Red colors represent regions where dust is abundant and where infrared radiation is being absorbed and re-emitted by dust particles rather than by free gas.

Dust particles in these regions contain silicates (minerals like those found in rocky planets), carbon compounds, and metals. They're genuinely small—perhaps 0.1 to 10 micrometers across, individual grains far too small to see with optical telescopes. But Webb's infrared sensitivity lets it detect the aggregate effect of billions of such grains.

The red zones are scientifically the most important for future planetary formation. These are the regions where the raw materials of planets are condensing. The dust grains will eventually collide, stick together, and accumulate into planetesimals, then asteroids, then planets. We're watching, in essence, the earliest stages of a planetary system's formation.

Comparing Webb to Hubble: A Transformation in Clarity

The Helix Nebula has been observed countless times since its discovery. Hubble Space Telescope observations from the 1990s and 2000s became iconic—stunning images that adorned textbooks and planetariums. So how does Webb compare? And what does that comparison tell us about the progress in astronomical instrumentation?

Hubble observes primarily in visible and ultraviolet light. Its observations of the Helix showed the nebula's distinctive ring structure with extraordinary clarity for optical telescopes. The images revealed concentric rings, suggesting that the nebula wasn't expelled in a single event but in multiple episodes. Different shells might represent different outburst phases thousands of years apart.

But Hubble's visible-light observations have a limitation: dust obscures the view. Cosmic dust absorbs visible light and scatters it, creating what's called extinction. This means Hubble can't penetrate the densest regions of the nebula's outer shell as effectively. The cooler, dustier regions remain partially hidden.

Webb, observing in infrared, passes through this dust barrier. Infrared photons have longer wavelengths than visible light, so they're scattered less by dust grains. Webb can see into regions that would appear opaque to Hubble. Moreover, Webb's infrared sensitivity lets it detect the thermal radiation from cool dust itself—something Hubble can't do in most cases.

The resolution also matters. While Hubble's camera has excellent angular resolution for visible light, Webb's infrared instruments achieve comparable angular resolution despite operating at much longer wavelengths. This is partly due to Webb's larger mirror (6.5 meters versus Hubble's 2.4 meters) and partly due to clever optical design. The combination means Webb can reveal fine structure in the nebula that Hubble simply cannot resolve.

When you compare the images side by side, the difference is striking. Hubble's view shows the overall structure—rings and shells. Webb's view shows intricate pillars, filaments, and structures within those shells. It's the difference between seeing a city's skyline from an airplane versus walking down its streets. Both perspectives have value. Webb's is simply more detailed.

Spectrographically, Webb also outperforms Hubble. By breaking down the infrared light into component wavelengths, Webb can measure temperatures more precisely and identify specific molecular species more definitively. Where Hubble might say "there's hydrogen here," Webb can say "there's cool molecular hydrogen at 5,200 Kelvin with specific abundance ratios of isotopes." This level of detail is revolutionary for understanding the physical processes occurring.

The time investment also differs. Observing the Helix Nebula with Hubble typically required several hours of precious telescope time. Webb's efficiency is greater—it can gather more detailed information per unit observing time, partly because infrared instruments don't require as much exposure time to gather equivalent data from cool objects.

The white dwarf's surface temperature is nearly 20 times hotter than the Sun, highlighting its extreme nature.

The Physics of Gas Ionization and Recombination

Underlying everything visible in these images is fascinating physics. The process of ionization and recombination drives the nebula's glow and tells us about temperature and composition. Let's dive into the actual mechanisms.

When a photon from the white dwarf strikes a neutral hydrogen atom, energy gets transferred. If the photon carries enough energy (specifically, more than 13.6 electron volts), it can overcome the electron's binding energy to the nucleus. The electron gets knocked free, leaving behind an ionized hydrogen atom—just a proton. The free electron, meanwhile, wanders through the gas as a charged particle.

This process is called photoionization. The ultraviolet photons from the white dwarf are energetic enough to ionize essentially every hydrogen atom they hit in the inner regions of the nebula. This creates what's called an ionization front—a boundary between the ionized and neutral gas. Inside this front, all the hydrogen is ionized. Outside it, hydrogen remains neutral.

The physics doesn't stop there. Free electrons don't remain free forever. They eventually recombine with ions. When an electron recombines with a proton, it must fall into an energy level around the nucleus. If it falls from a high energy level to a lower one, it emits a photon. The wavelength of that photon depends on which energy levels are involved.

For hydrogen, specific transitions produce specific wavelengths. An electron falling from the n=3 energy level to n=2 produces the H-alpha line at 656 nanometers—a deep red visible to human eyes. This is the characteristic deep red glow of many emission nebulae. Electrons falling to the n=2 level from higher levels produce the Balmer series of lines, primarily visible light. Electrons falling to the n=1 level produce ultraviolet light (the Lyman series).

This recombination process continuously re-ionizes the gas—the newly released photons travel outward and ionize more atoms. In the inner regions, where the ultraviolet radiation is intense, the gas remains ionized. In outer regions where ultraviolet intensity is lower, atoms can remain neutral or form molecules before being re-ionized.

For heavier elements like oxygen and nitrogen, the physics becomes more complex. Oxygen can lose one, two, three, or even more electrons (though multiple ionization requires intense ultraviolet). Each ionization state has different emission line wavelengths. By measuring these various emission lines in infrared, Webb can determine not just temperature but also the relative abundance of elements.

The equilibrium state of ionization at any location in the nebula depends on several factors: the local ultraviolet intensity from the white dwarf, the local gas temperature (which determines recombination rates), the density of free electrons available for recombination, and the abundance of heavy elements. Understanding how all these factors balance gives us a physical model of what's happening throughout the nebula.

One crucial insight from these models is that the nebula's structure isn't random. Dense regions remain partially neutral or molecular even when exposed to ultraviolet radiation, because atoms can recombine faster in high-density gas. Rarified regions ionize completely. These density variations create the observed fine structure—the pillars and filaments visible in Webb's images represent density enhancements.

The Role of Dust in Planetary Formation

While the glowing gas captures our attention, the dust in planetary nebulae tells an equally important story. Dust is the substrate from which planets ultimately form, yet it's often overlooked in discussions of nebular physics. Webb's infrared capabilities let us study dust in unprecedented detail.

Dust particles in the Helix Nebula likely consist of silicates, carbonaceous compounds, and perhaps some metallic elements. The exact composition depends on the initial composition of the progenitor star. A star like our Sun with solar abundances would produce dust similar to what we find in meteorites in our own Solar System.

Dust forms through a process called nucleation and growth. Initially, individual atoms or small clusters of molecules form the "seeds" around which more material condenses. In the cool outer regions of the expanding nebula, where temperatures have dropped to a few thousand Kelvin, atoms can stick together. Silicate molecules form, then larger silicate clusters, then grains.

Once dust grains form, they can grow further through collisions and sticking. Small grains collide, merge, and form larger grains. This process, repeated billions of times across the nebula, eventually produces a distribution of grain sizes. The largest particles might reach millimeter sizes, though most remain micrometer-sized.

Dust plays a crucial role beyond just being a physical building block. Dust grains provide surfaces where molecules can form. In the gas phase, many reactions are slow or impossible—atoms and molecules pass through each other. But on a dust grain surface, atoms can stick, react, and form more complex molecules. This is how organic compounds might form in planetary nebulae, eventually becoming incorporated into comets and asteroids in forming planetary systems.

Dust also affects the nebula's dynamics through radiation pressure. Photons from the white dwarf carry momentum. When a photon is absorbed by a dust grain, it transfers momentum, exerting a tiny force on the grain. In the intense radiation field near the white dwarf, this radiation pressure can actually push dust grains outward, affecting the nebula's overall expansion.

Webb's infrared observations reveal the spatial distribution of dust within the nebula. The density of dust affects how strongly infrared light is absorbed and re-emitted. By mapping these infrared intensities, astronomers can create three-dimensional models of where dust is concentrated. These models show that dust isn't uniformly distributed but concentrated in filaments and clumps, much like the ionized gas.

The fascinating implication is that planetary systems forming from this material wouldn't be random either. The clumpy distribution of planetesimals and forming planets might bear the signature of the nebula's original structure. The architecture of planetary systems might, in some sense, be predetermined by how dust happens to be concentrated in the progenitor nebula.

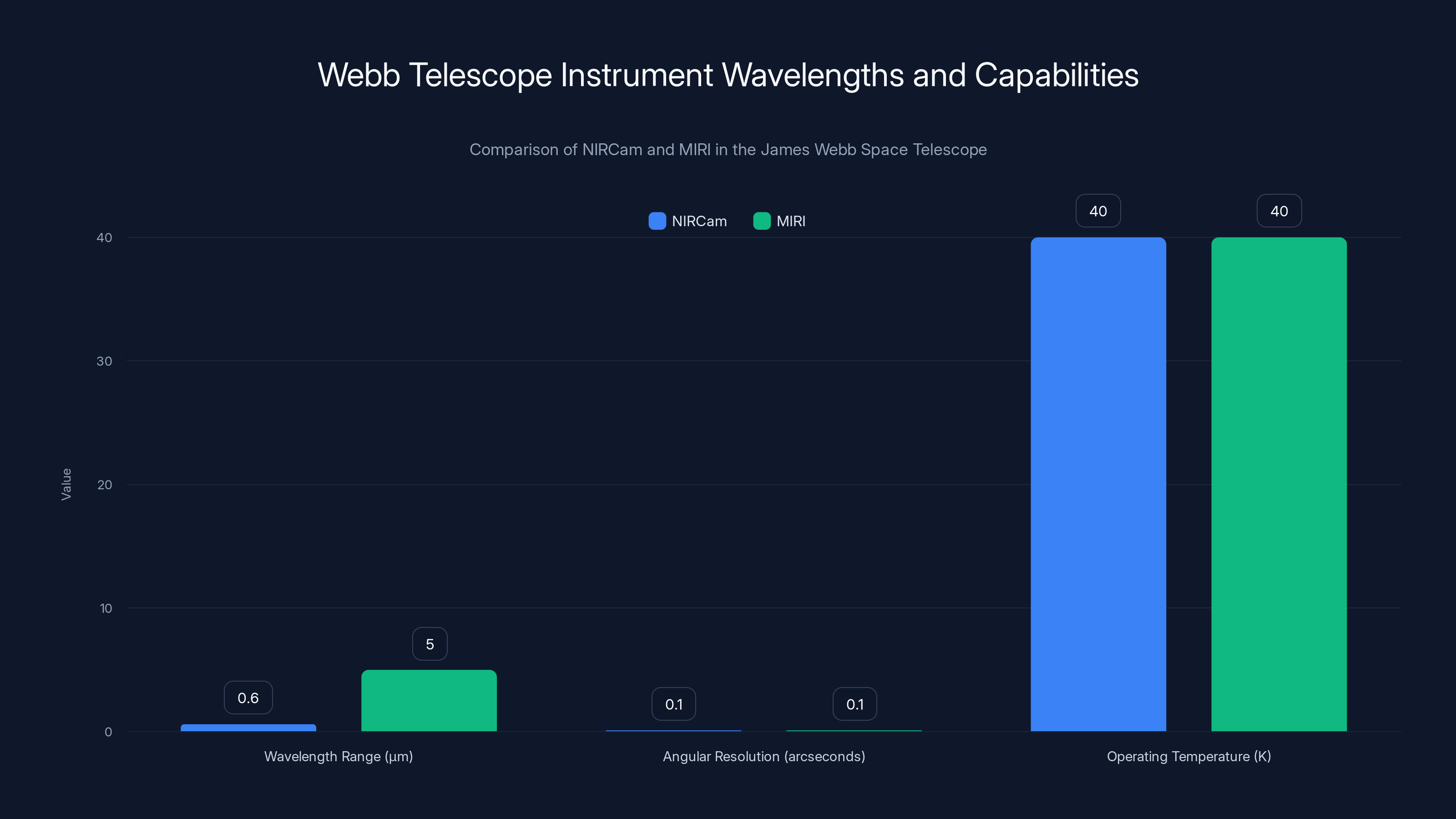

NIRCam and MIRI operate in different infrared ranges but share similar angular resolution and operating temperatures, crucial for capturing detailed images of cosmic structures.

Helix Nebula's Unique Characteristics and Why It Matters

The Helix Nebula holds several distinctions that make it particularly valuable for astronomical research. Understanding these characteristics helps explain why it's been observed repeatedly and why new observations like those from Webb are so significant.

First, proximity. At roughly 655 light-years distant, the Helix is one of the nearest bright planetary nebulae. For comparison, many other well-known planetary nebulae are several thousand light-years away. This proximity means the nebula subtends a relatively large angle in the sky (about 0.32 degrees across, roughly 64% the width of the full moon as seen from Earth). This large angular size means fine details that would be invisible in distant nebulae can be resolved.

Second, brightness. The Helix is quite luminous. Its total brightness in visible light makes it observable even from reasonably dark skies without optical aid (though you'd need binoculars or a telescope to see it well). This brightness made it an attractive target for the first telescopic observers centuries ago and continues to make it an attractive target today.

Third, morphology. The Helix's distinctive ring-like appearance, particularly the configuration that gave it its name (the helical structure isn't actually helical but represents concentric shells viewed at an angle), makes it instantly recognizable. This distinctive structure has sparked considerable scientific interest. Why does it have this particular shape? What does it tell us about the ejection process?

Fourth, evolutionary stage. The Helix appears to be a relatively young planetary nebula, perhaps only around 6,500 years old based on measurements of its expansion rate. This means the nebula hasn't yet fully dispersed, and the structures are still well-defined. Older planetary nebulae become increasingly diffuse and harder to observe.

Fifth, scientific productivity. The Helix has been instrumental in our understanding of planetary nebulae generally. Observations of the Helix have helped us understand how these objects form, evolve, and disperse. Each new generation of telescopes, from photographic plates to digital CCD cameras to infrared arrays, has revealed new details. The Helix serves as a kind of laboratory where fundamental processes can be studied in detail.

These characteristics combine to make the Helix a standard target for any new astronomical capability. When Hubble was launched, the Helix was observed. When infrared satellites like IRAS detected the nebula, it became a focus. Now with Webb operational, the Helix has naturally become one of the objects studied in detail. The resulting dataset provides a remarkable record of how observational techniques and instruments have advanced.

What These Images Reveal About Planetary Formation

Perhaps the most scientifically significant aspect of these new Webb observations concerns what they tell us about how planets form. The expanding shell of material—the ionized gas, the molecular hydrogen, the dust—represents the chemical inventory from which planets eventually form. Understanding this material's properties is crucial for understanding planetary formation.

In our own Solar System, planets formed from a disk of material surrounding our young Sun. This protoplanetary disk contained gas and dust, much like the material we see in the Helix Nebula today. The dust coagulated into planetesimals, then planetary embryos, then full-sized planets. By studying the Helix and similar objects, we can observe what this material is like before, during, and shortly after planetary assembly.

The temperature gradient visible in the Webb images directly mirrors what we believe occurred in the early Solar System. Hot, ionized inner regions where only very refractory materials could survive. Cooler outer regions where more complex, volatile-rich materials could accumulate. The specific location where dust could form and planets could begin to coalesce would depend on local temperature conditions, much as the Helix's current structure reflects its temperature profile.

The presence of molecular hydrogen in the intermediate temperature zones tells us about chemistry's role. The formation of molecular species enables more complex chemistry. Organic molecules (compounds containing carbon) form more readily in the presence of molecular hydrogen. These organics become incorporated into forming planets and might even be relevant to the emergence of life on suitable planets.

Dust composition matters enormously. Silicon and oxygen combine to form silicates, the primary mineral in rocky planets. Iron can form metallic cores. Carbon can form graphite or carbonate compounds. The elemental composition of dust ultimately determines the composition of forming planets. By studying dust in planetary nebulae, we learn about the raw material available for planet formation in different environments.

The density structure visible in the Helix's filaments and clumps hints at something else important: how planets might be distributed in forming systems. Denser regions might accumulate more material, forming more massive planets. The spatial clustering of dense regions might explain why planetary systems often show planets clustered at particular orbital distances (resonances in the protoplanetary disk).

One particularly exciting revelation involves complex organic molecules (COMs). These are molecules containing multiple carbon atoms bonded in specific configurations. They're not life, but they're the chemical precursors from which life-related molecules form. Webb can detect some COMs in extreme environments. Finding them in planetary nebulae would suggest that even stars undergoing death can synthesize complex organic material, enriching their expelled material with pre-biotic chemistry.

Planetary nebulae expand at speeds ranging from 20 to 50 km/s over thousands of years. Estimated data based on typical expansion rates.

White Dwarfs and Their Evolutionary Timeline

Understanding the white dwarf at the Helix's center requires understanding stellar evolution's broader context. Where does a white dwarf fit in a star's life story? How long does it persist? What eventually happens to it?

A star like our Sun spends most of its life—roughly 10 billion years in the Sun's case—fusing hydrogen into helium in its core. This phase, called the main sequence, represents the stable, quiet part of stellar evolution. The Sun is currently about halfway through its main sequence life. In another 5 billion years, it will begin to change.

When hydrogen fuel in the core becomes depleted, the core contracts and heats up. This increased heat ignites hydrogen fusion in a shell surrounding the inert helium core. The outer layers of the star expand dramatically, and the star becomes a red giant. At this phase, the Sun will swell to perhaps 250 times its current size, engulfing Mercury, Venus, and possibly Earth.

But this phase doesn't last long—cosmically speaking. After only a billion years or so as a red giant, the Sun will reach the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) phase. The core continues contracting and heating. Eventually, helium in the core fuses to form carbon and oxygen. But unlike the Sun, stars only slightly more massive will go through additional fusion stages.

For the Helix's progenitor star, which was somewhat more massive than our Sun (perhaps 1.2 to 1.5 solar masses based on the white dwarf's mass), the AGB phase might have included additional nuclear reactions. It matters because the white dwarf we observe today carries the chemical signature of all previous reactions. Its composition tells us about the star's evolutionary history.

Eventually, the aging star loses its outer envelope. This ejection isn't instantaneous but occurs over thousands of years as a stellar wind gradually removes the outer layers. The increasingly exposed hot core ionizes this ejected material, creating the luminous nebula we observe. Over perhaps 10,000-20,000 years, the nebula becomes transparent enough that it no longer glows—the material has expanded so much and become so rarified that ionization becomes inefficient.

What happens to the white dwarf itself? It simply cools. Without any fusion occurring, it radiates away its heat into space. A white dwarf cools very slowly—it's so small and dense that it has an enormous heat capacity. The white dwarf in the Helix currently has a surface temperature around 110,000 Kelvin. It's cooling at a rate of only about 1 Kelvin per million years. In 50 billion years, it might cool to 10,000 Kelvin.

Eventually, over trillions of years, white dwarfs cool to become black dwarfs—objects so cold they emit no observable radiation. The universe isn't old enough for any black dwarfs to exist yet. But theoretically, given enough time, the Helix's white dwarf and all other white dwarfs will eventually become black dwarfs, dark objects persisting in space long after their progenitor stars' dramatic deaths.

Technical Aspects of Webb's Infrared Observations

Understanding how Webb captured these remarkable images requires delving into the technology. What instruments did Webb use? Why infrared? What wavelengths matter?

The James Webb Space Telescope operates primarily in infrared wavelengths, from about 0.6 micrometers (in the visible-infrared transition region) to 28.3 micrometers (in the mid-infrared). The Helix Nebula observations utilized several of Webb's instruments, each revealing different aspects of the nebula's structure and composition.

The Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) operates from about 0.6 to 5 micrometers. This wavelength range captures the transition between visible light and longer-wavelength infrared. Observations in this band are particularly good at imaging dust and seeing through dust that would block visible light. NIRCam's angular resolution is about 0.1 arcseconds at its shortest wavelengths—fine enough to see details in the nebula roughly 100 times smaller than the human eye could resolve, even with the best ground-based telescope.

The Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) operates from about 5 to 28 micrometers. This range is excellent for observing cool dust and gas emission lines from heavier elements like oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur. MIRI's resolution is comparable to NIRCam's because despite working at longer wavelengths, it compensates through optical design. The mid-infrared observations revealed crucial information about dust composition and temperature structure.

Webb's infrared cameras operate at phenomenally cold temperatures. To avoid swamping the faint infrared signals from distant objects with the telescope's own thermal infrared emission, the instruments must be cooled to extremely low temperatures. The detectors operate at about 40 Kelvin (minus 233 degrees Celsius). Webb's sunshield—a series of reflective layers—maintains this cold by blocking solar heating and Earth's radiated heat.

Why infrared for planetary nebulae? Several reasons combine to make infrared optimal. First, dust extinction is reduced at infrared wavelengths. Dust grains that block visible light pass longer-wavelength infrared relatively unimpeded. Second, cool dust and cool gas emit primarily in infrared. The coldest regions of the Helix, which are most interesting for planetary formation, emit most of their energy as infrared radiation. Third, infrared wavelengths allow detection of molecular emission lines from species like molecular hydrogen that might not be easily observable in visible light.

The specific choice of wavelengths matters. Different molecules and different ionization states emit characteristically at different infrared wavelengths. Ionized oxygen (O III) emits strongly at 88 micrometers. Molecular hydrogen emits at 2.12 micrometers. Different dust compositions absorb and emit at different wavelengths. By observing in multiple wavelength bands and comparing the results, astronomers can map composition and temperature structure with precision.

Webb's angular resolution, while incredible for space-based infrared astronomy, doesn't capture every detail on impossibly small scales. Some structures in the Helix remain unresolved—they appear as blurs rather than distinct features. But compared to earlier infrared observations, the improvement is transformational. Infrared missions like the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center's archival data on the Helix are now augmented by Webb's far superior resolution and sensitivity.

Data processing is another crucial aspect. Raw data from Webb goes through sophisticated calibration. Instrumental effects must be removed. Different wavelength bands must be registered—precisely aligned so features in one band match features in another. False-color mapping must be applied to translate infrared data into visible colors. Only after this processing do the stunning images we see emerge from raw detector readings.

The Chemical Composition Decoded

Planetary nebulae tell us about stellar nucleosynthesis—the processes by which stars create elements. The Helix's composition reflects what happened inside its progenitor star during billions of years of evolution.

Primary elements observed in the Helix include hydrogen, helium, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and small amounts of heavier elements like neon, magnesium, silicon, sulfur, and iron. Each element has a characteristic emission signature in infrared wavelengths, allowing Webb to measure abundances.

Hydrogen and helium are primordial—they existed since the Big Bang and comprise the vast majority of matter. Most stars are primarily hydrogen and helium. But the Helix's progenitor star was enriched in heavy elements (astronomers call anything heavier than helium a "metal," a technical term that includes carbon and oxygen despite their being non-metals in common usage). This enrichment probably came from interstellar material the star incorporated when it formed, material that itself had been enriched by previous stellar generations.

Carbon and oxygen are particularly interesting. These were created inside the star through nuclear fusion. Carbon formed through the triple-alpha process—helium nuclei fusing to form beryllium-12, which is usually unstable, but occasionally captures another helium nucleus before decaying, forming carbon-12. Oxygen formed through similar processes.

The carbon-to-oxygen ratio tells us about the star's internal nucleosynthesis history. Different amounts of internal mixing and different nuclear reaction rates produce different ratios. By measuring the ratio in the nebula, we gain insight into the star's internal structure when it was actively fusing.

Nitrogen is particularly revealing. It forms primarily through the CNO cycle—a chain of nuclear reactions that converts hydrogen into helium using carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen as catalysts. Because this cycle is extremely temperature-sensitive, the amount of nitrogen produced depends strongly on how hot the star's core got during its hydrogen-fusing phase. The abundance of nitrogen in the Helix tells us something about its progenitor star's core temperature billions of years ago.

Sulfur, neon, magnesium, and silicon primarily formed in more massive stars. Finding them in the Helix suggests that the progenitor star either underwent additional nuclear reactions (implying it was somewhat more massive than the Sun) or that the material was enriched by interactions with nearby massive stars that exploded as supernovae before the Helix's progenitor was ejected.

This elemental detective work helps astronomers construct models of the galaxy's chemical evolution. By observing the composition of planetary nebulae throughout the galaxy and noting how composition varies with location and age, we can trace how elements have been created and distributed over galactic history. Every heavy atom in our bodies was created either in stars or during supernovae. Studying planetary nebulae literally helps us understand our own cosmic origins.

Comparing Past and Future Observations

The Helix Nebula has been observed for centuries, but quantitative observations go back only about a century to the dawn of spectroscopy and astrophotography. This long observational history provides a remarkable dataset for studying how the nebula changes over time.

Early spectroscopic observations from the early 1900s established the nebula's basic composition and that it was expanding. In the decades that followed, astronomers refined measurements of expansion velocities. Typically, nebula expands at speeds of 10-50 kilometers per second. For the Helix, expansion rates around 20 km/s are typical. Over decades of observation, the nebula's angular size should measurably increase. Indeed, careful measurements show the nebula expanding at rates consistent with these velocities extrapolated backward to estimate the nebula's age.

The Hubble Space Telescope, from the 1990s onward, revolutionized planetary nebula observations by providing unprecedented optical clarity. Hubble images revealed intricate structure invisible to ground-based telescopes. The Helix's complex ring structure became clearly apparent. Subtle color variations emerged. Hubble observations also made possible precise measurements of gas velocities using the Doppler shift—how motion affects wavelength. Different parts of the nebula move at slightly different velocities, revealing that the ejection occurred in pulses rather than smoothly.

Webb's observations now add the infrared dimension. Where Hubble revealed the structure of the ionized gas, Webb penetrates to cooler gas and dust. The two telescopes observe complementary aspects of the same object.

Looking forward, future observations will undoubtedly occur with new telescopes and instruments. The Extremely Large Telescope, currently under construction in Chile, will offer ground-based infrared and optical observations with resolution rivaling or exceeding Webb's in some bands. Space missions planned for the coming decades will have specialized capabilities. Each observation adds to our understanding.

One exciting prospect involves spectroscopy at extremely high resolution. Current observations provide information about average conditions in different regions. High-resolution spectroscopy would reveal velocity structure—how gas moves within each region. This would clarify whether the complex structures visible in images represent distinct expanding shells, turbulence, or interactions between different ejection events.

Another prospect involves long-term monitoring. The Helix has been measured for over a century. Comparing observations separated by decades allows measurement of actual motion. As the nebula expands and evolves, its appearance changes. With enough long-term data, a complete history of the ejection can be reconstructed. This history would illuminate the physical processes involved in stellar death and atmospheric ejection.

Implications for Understanding Exoplanet Formation

These Webb observations aren't merely beautiful; they're scientifically important for exoplanet research. Understanding how planets form in different environments, including around dying stars, helps us construct more complete models of planetary system origins.

The past three decades have revealed that planets form almost everywhere. Around young stars in protoplanetary disks (the traditional formation scenario). Around evolved stars on the asymptotic giant branch. Around white dwarfs in some surprising cases. Around neutron stars (pulsars). The Helix Nebula material, once dispersed, might form a new planetary system around the white dwarf itself or might escape into interstellar space, eventually contributing to future star and planet formation elsewhere.

The planetary systems we've discovered around main-sequence stars often surprise us. Planets orbit at unexpected distances. Planetary masses don't match predictions. Orbital eccentricities are higher than expected. Understanding how planets form might explain these observations—perhaps the initial configurations predicted by theory get scrambled through planetary interactions before settling into final orbital configurations.

Planetary nebula material provides a natural laboratory for understanding this process. The material isn't collapsing into a new planetary system immediately. It's gradually dispersing. But the structures observable in the Helix hint at how density variations in the initial material affect final planetary arrangements. Dense clumps in the material might produce planets spaced more regularly. Smooth, uniform material might produce irregularly spaced planets.

The presence of complex organic molecules in planetary nebula material also matters for astrobiology. If life-related molecules form around dying stars, and if those molecules become incorporated into forming planets, then life's chemical building blocks might be even more common than previously thought. This would suggest that life might arise on planetary systems in diverse contexts, not just around young, stable main-sequence stars.

The Helix observations also illuminate how planetary systems change over time. Our Solar System formed in a solar nebula similar in basic character to what we see in the Helix, though the initial conditions were somewhat different. But billions of years later, our system has evolved significantly. Planets have migrated. The asteroid belt has been depleted by collisions and scattering. Understanding how planetary systems evolve from their formation in nebular material to their current state, over billions of years, remains an active research frontier. Observations of planetary nebulae at various ages provide crucial snapshots along this evolutionary timeline.

The Future: What Comes Next for the Helix Nebula

As the Helix Nebula continues to expand and cool over millennia, its appearance will continue to change. In thousands of years, it will become increasingly diffuse and faint. The bright structures visible today will gradually fade as the gas becomes too rarified to glow efficiently. The white dwarf at its heart will continue cooling, its surface temperature dropping slowly over billions of years.

Future astronomers thousands of years from now—if civilization persists that long—will see a different Helix Nebula. The nebula visible to them will be much dimmer, more extended, and less structured than what we observe today. But its fundamental nature will remain unchanged: evidence of a star's final breath, the chemical building blocks for future worlds.

Scientifically, the Helix will continue to be valuable for understanding planetary nebulae as a class of objects. Each new observation technology—every improvement in telescope power or sensitivity—will reveal new details. The Helix will likely remain on the target lists of major telescopes far into the future.

The specific question of whether a planetary system will actually form from the Helix's material remains open. The material is gradually dispersing into interstellar space. It's not concentrated enough to gravitationally collapse into a new planetary system. But that material might eventually mix with other interstellar gas, become part of a new interstellar cloud, eventually collapse to form new stars and planets. The atoms in the Helix might be recycled repeatedly through stellar and planetary systems over cosmic time.

From our perspective today, looking at the Helix through Webb's extraordinary vision, we're witnessing a moment in a cosmic process that spans billions of years. We're seeing the instant—a mere 6,500 years in a stellar evolution spanning billions of years—when a star has just shed its outer layers. The nebula is bright, structured, and scientifically rich with information. In a few tens of thousands of years, it will fade. But the process it represents—stellar death and cosmic recycling—will continue indefinitely throughout the universe.

FAQ

What is a planetary nebula, and why isn't it actually related to planets?

A planetary nebula is a glowing shell of gas ejected by a dying star, specifically a star similar to our Sun at the end of its life. Early astronomers named them "planetary" nebulae because through crude telescopes, they resembled the disks of planets. The name stuck despite being misleading—they have nothing to do with planets themselves. Instead, planetary nebulae are stellar remnants: the outer atmosphere of an aging star, ejected over thousands of years, being illuminated by the hot white dwarf core left behind.

How does the James Webb Space Telescope observe infrared light, and why is this better than visible-light telescopes for studying nebulae?

Webb observes infrared light—electromagnetic radiation with longer wavelengths than visible light. It does this using specialized detectors cooled to extremely cold temperatures (about 40 Kelvin) and protected from thermal emissions by an innovative sunshield. Infrared observation is superior for studying planetary nebulae because dust blocks visible light but allows infrared to pass through, revealing cool gas and dust invisible to optical telescopes. Additionally, cool material in nebulae emits most of its energy as infrared radiation, making infrared observations more sensitive to the full range of conditions within the nebula.

What do the different colors in the Webb image represent, and how does that information help scientists?

The colors are a false-color representation created by mapping different infrared wavelengths observed by Webb to visible colors. Blue represents the hottest, most ionized gas (around 10,000 Kelvin or hotter) close to the white dwarf. Yellow represents intermediate temperatures where molecular hydrogen forms (around 8,000 Kelvin). Red represents the coolest regions where dust condenses (around 5,000 Kelvin). This color mapping translates infrared data into a visual format that simultaneously shows temperature structure, chemical composition, and density variations throughout the nebula, enabling scientists to understand the physical processes occurring.

Why is the Helix Nebula considered especially important for astronomical research?

The Helix Nebula is important for several reasons. It's one of the nearest and brightest planetary nebulae, making fine details observable that would be invisible in more distant objects. Its distinctive ring-like structure makes it instantly recognizable and provides clues about the ejection process. Its relatively young age (about 6,500 years) means structures are still well-defined. Its long observational history—centuries of observations including decades of precise measurements—provides unique data about how planetary nebulae evolve. For all these reasons, every new astronomical capability, from Hubble to Webb, has studied the Helix, making it a standard reference object.

How do planetary nebulae relate to planetary formation?

Planetary nebulae material contains the exact elements and compounds that form planets: silicon for silicate minerals, iron for planetary cores, carbon and oxygen for organic compounds, and dust grains that can coalesce into planetesimals. While the Helix's material is currently dispersing and won't form a planetary system immediately, similar material in protoplanetary disks around young stars becomes planets through collisions and gravitational accretion. Studying planetary nebulae helps us understand the raw materials and conditions in planetary formation environments. Additionally, understanding how long-lived planetary systems can form around white dwarfs in some cases reveals the diversity of planetary formation pathways.

What will eventually happen to the Helix Nebula, and is it still changing?

The Helix Nebula continues to expand at a rate of approximately 20 kilometers per second. Over thousands of years, it will become increasingly diffuse and faint as the material spreads into a larger volume. Eventually, in perhaps 50,000 years or so, it will become too rarified to glow efficiently and will essentially fade from visibility. The white dwarf at its center will continue cooling over billions of years—an extraordinarily slow process that won't significantly change its appearance for millions of years. The material itself won't form a planetary system but will gradually mix into the interstellar medium, potentially becoming part of future star and planet formation elsewhere in the galaxy.

Conclusion: Witnessing Cosmic Transformation

The James Webb Space Telescope's images of the Helix Nebula represent more than just beautiful astronomical photography. They're a window into fundamental processes that have shaped our universe and continue to shape it. When we look at the Helix, we're witnessing stellar death—but not the violent, catastrophic kind. This is death transformed into rebirth, stellar material being recycled for use in new worlds.

The specific revelation that Webb brings is resolution and depth. Previous telescopes could see that the nebula was complex, with multiple shells and structures. Webb shows us the intricate details: the filaments, the density variations, the temperature gradients. It reveals not just that there's structure but precisely what that structure is and what physical processes created it.

The colors in these images are particularly powerful. They're not arbitrary choices but deliberate mappings of scientific data into a visual format our brains can readily comprehend. Blue hot, red cool—the familiar associations translate into understanding. But beneath the aesthetic is genuine physics: ionization and recombination, molecular formation, dust condensation, the transformation of stellar material from extreme temperatures to conditions suitable for planetary formation.

What strikes me most profoundly about these images is their reminder of how much we still don't know. We understand planetary nebulae better than we did a decade ago, but questions remain. How exactly does the ejection process work? Why do different planetary nebulae have different structures? Do planetary systems actually form from planetary nebula material, and if so, how successfully? What's the full range of organic chemistry occurring in these environments?

Future observations will address these questions. Webb will continue observing the Helix and other planetary nebulae. New telescopes will come online. But the fundamental value of the Helix lies in what it represents: a cosmic message from a dying star about the continuity of matter through stellar lifetimes.

Our own Solar System formed from similar material billions of years ago—material expelled by earlier stellar generations, enriched with heavy elements created in those stars' cores. The atoms in your body were forged in stellar furnaces and distributed through space by events like the Helix Nebula. Looking at the Helix isn't just looking at a nebula. It's looking at our own origins, written in glowing gas and dust across light-years of space.

The Webb images remind us why astronomy matters. In an age of immediate concerns and short-term thinking, astronomy offers perspective. It connects us to processes spanning billions of years, scales spanning thousands of light-years, and fundamental physics spanning from subatomic particles to galactic structures. The Helix Nebula, through Webb's unprecedented vision, tells that larger story with spectacular clarity.

Key Takeaways

- Webb's infrared observations reveal unprecedented detail in the Helix Nebula's structure, showing distinct temperature zones from 10,000+ Kelvin ionized gas to 4,500 Kelvin dust formation regions.

- The colors in Webb's images represent actual temperature and chemical composition, with blue indicating extreme ionization near the white dwarf and red showing dust where future planets might form.

- Planetary nebulae represent stellar death transformed into cosmic recycling—the material and chemical elements will eventually contribute to new stars and planetary systems.

- The Helix Nebula's white dwarf core will take trillions of years to cool, and the expanding nebula will remain bright enough to observe for another 50,000 years before dispersing completely.

- Understanding planetary nebulae like the Helix directly informs exoplanet formation models and reveals how the universe continuously creates and distributes the building blocks of worlds.

![James Webb's Helix Nebula: The Universe's Most Spectacular Cosmic Transformation [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/james-webb-s-helix-nebula-the-universe-s-most-spectacular-co/image-1-1768954177547.png)