Jonathan Nolan on AI in Filmmaking: The Complete Industry Analysis

Jonathan Nolan didn't predict the AI revolution. He built a career imagining it.

Before Chat GPT became a household name, before Hollywood studios started panicking about what generative AI means for screenwriters and visual effects artists, Nolan was already exploring these questions through his work. Person of Interest, which ran for five seasons on CBS, centered on a reclusive tech billionaire who creates surveillance software designed to stop crimes before they happen. That was fiction written back in 2011, but it reads like documentary now.

Fast forward to 2024, and Nolan finds himself in a strange position. He's one of the most successful showrunners in television history. He created Westworld with his wife Lisa Joy, a sprawling exploration of artificial consciousness that earned 16 Emmy nominations. He's executive producing Amazon Prime's Fallout, based on the beloved video game series, bringing post-apocalyptic retrofuturism to life with the kind of detail that keeps fans arguing about lore on Reddit. He's collaborated with his brother Christopher Nolan on some of the biggest films in cinema, from Interstellar to The Dark Knight trilogy.

Yet despite all this success, or perhaps because of it, Nolan has become one of the few major voices in entertainment willing to talk about AI with nuance rather than panic or hype.

In a recent conversation, Nolan shared thoughts that challenge the dominant narrative in both directions. He doesn't think AI will replace human filmmakers, contrary to the doomsayers in the writers' room. But he also doesn't think it's some magic wand that will transform the industry overnight. Instead, he sees something more interesting: a democratization tool for people who currently can't afford to make films, paired with a potential threat to the traditional studio system that he's spent his career working within.

He's also clear about his own position. He will never use AI in his writing. Not because it's impossible, but because it would fundamentally change what he does.

This distinction matters. It separates the hype from the reality.

Let's unpack what Nolan actually said, what it means for the film and television industry, and why his perspective—informed by two decades of working at the highest levels of entertainment—offers a clearer view of where cinema is actually heading than most of the discourse currently happening.

The "Frothy Moment" We're In

Nolan's phrase was careful: "We're in such a frothy moment." Not revolutionary. Not transformative. Frothy.

Froth is unstable by definition. It looks impressive, full of air and potential, but it collapses quickly. The metaphor reveals something crucial about Nolan's thinking. He's skeptical of the idea that AI's current capabilities represent the future of filmmaking. Instead, he sees a period of wild experimentation, inflated expectations, and significant hype that will eventually settle into something more realistic.

This is important context because the discourse around AI in entertainment tends toward extremes. On one end, you have studio executives and tech entrepreneurs convinced that AI will reduce production budgets by 80% and replace entire departments. On the other end, you have writers and artists convinced that AI represents an existential threat to their livelihoods.

Nolan's "frothy moment" sits between these poles. It acknowledges the genuine technological capability—AI can now generate images, compose music, write dialogue, and create visual effects that are sometimes indistinguishable from human work. But it also suggests these capabilities don't necessarily map onto how filmmaking actually works.

Consider what goes into a Fallout episode. It's not just the script. It's casting decisions that involve understanding complex character dynamics. It's production design choices that reference decades of video game lore and 1950s Americana aesthetics. It's directing performances from actors in ways that convey emotional subtext. It's editing pacing across 50-minute episodes that need to hit specific emotional beats.

AI can assist with some of these tasks. It cannot currently execute all of them in concert while maintaining thematic coherence and emotional truth.

Yet Nolan isn't dismissing AI's potential in filmmaking. He's just honest about the current moment being something other than what the headlines suggest.

Why AI Could Actually Help New Filmmakers

Here's where Nolan's perspective becomes genuinely interesting, and somewhat counterintuitive.

Traditionally, becoming a filmmaker required resources most people didn't have. You needed expensive equipment. You needed to hire actors. You needed access to locations. You needed to manage post-production with costly software and professional editors. The barrier to entry was astronomical, which meant that filmmaking remained the province of people who either had inherited wealth or connections to the industry.

This created a self-perpetuating system. The people who could afford to make movies looked like the people who'd made movies before them. Certain stories got told. Other stories didn't. Certain perspectives dominated cinema. Others remained invisible.

AI doesn't solve this problem completely, but it significantly lowers barriers in specific ways.

Imagine you're a 22-year-old filmmaker in Des Moines with a story you desperately want to tell. You can't afford a proper camera crew. You can't afford to hire professional actors. You can't afford the color grading software that costs thousands per month.

With current AI tools, you can generate backgrounds, create visual effects that would otherwise require teams of people, and even generate placeholder dialogue to experiment with pacing before recording live performances. You can't make a studio film this way, but you can make something that tells your story compellingly.

Nolan's point is that this might democratize access to filmmaking in ways that actually matter for artistic development and industry diversity.

The caveat—and it's crucial—is that this doesn't apply to the kinds of films Nolan makes. It doesn't apply to Fallout because that show requires union crews, expensive talent, professional equipment, and the kind of production infrastructure that only budgets in the tens of millions of dollars can support.

But for independent films, for student projects, for documentaries made by individuals rather than institutions? AI could be genuinely transformative.

Nolan seems to understand something that much of the entertainment industry doesn't: AI threatens the middle more than it threatens the extremes. The $300 million tentpole that requires armies of professionals will probably always require armies of professionals, because the expectations around quality and scope demand it. The solo filmmaker making art in their spare time was always impossible within the traditional studio system.

What AI threatens is the mid-budget film and television industry that currently exists between these extremes. That's where Nolan's concern lies, though he doesn't explicitly state it that way.

The Question of Writing and Creative Vision

When asked directly whether he uses AI in his own writing, Nolan's answer was unambiguous: no.

This requires unpacking because it's not reflexive Ludditism.

Nolan has spent decades understanding how writing shapes storytelling. When he came up as a screenwriter, he worked with his brother Christopher on everything from the script to the edit. When he transitioned to television with Person of Interest, he had to develop an entirely different skill set. Episodic writing requires thinking about narrative serialization, character arcs that span seasons, and how to sustain interest across 22 episodes per year.

Westworld demanded something else entirely. It required coordinating multiple timelines, managing philosophical debates about consciousness and agency, and developing dialogue that could handle both intimate character moments and large-scale conceptual discussions.

Each of these disciplines shaped how Nolan thinks about writing. The tool (in this case, the screenwriting or novel-writing process) directly influences the writer. Using different tools produces different results.

When Nolan says he won't use AI in his writing, he's not just being protective about artistic purity. He's being precise about creative methodology. AI-assisted writing produces a different kind of output than pure human writing. It's not necessarily worse, but it's different. The iterative process of struggling with language, discovering unexpected connections between ideas, and allowing the resistance of the medium to shape your thinking—all of this vanishes when you're working with AI suggestions.

This gets at something deeper about the creative process that rarely gets discussed in debates about AI and art. Creativity isn't just about the final output. It's about the thinking that happens during production. The constraints of language, the limitations of your own knowledge, the effort required to articulate something precisely—these constraints are what shape creative work.

AI removes some of these constraints. In some contexts, that's liberating. In others, it's neutering.

Nolan implicitly understands this distinction. He's willing to concede that AI could help other people make things they couldn't otherwise make. But for him, for the kind of work he does and the way he does it, AI assistance would be a step backward, not forward.

The Uncanny Valley Problem Nobody Talks About

One aspect of Nolan's perspective that deserves more attention is his implicit acknowledgment of what might be called the "creative uncanny valley."

In robotics and animation, the uncanny valley refers to the unsettling feeling you get when something looks almost human but not quite. It's too close to real to seem fully artificial, but not close enough to seem authentically human. This triggers discomfort.

Something similar happens with AI-generated content in entertainment.

When AI generates a completely artificial scene that everyone recognizes as AI-generated, there's no problem. When AI generates something indistinguishable from human work, there's technically no problem either. But there's a middle ground—content that feels slightly off, that seems like it's imitating human creativity without quite capturing it—where the uncanny valley becomes a real creative liability.

Much AI-generated writing falls into this category. It's grammatically correct. The structure makes sense. But there's something missing in terms of voice, unique perspective, or emotional authenticity. It reads like someone competent but generic is writing it.

Filmmakers know this instinctively. Audiences can feel it, even if they can't articulate why something feels off. This is part of why Nolan is probably right that AI won't replace human filmmakers for prestige television or major films. Not because it's impossible in some absolute sense, but because audiences increasingly care about authorial voice and unique perspective, and AI currently struggles to deliver those things in ways that feel authentic rather than imitative.

The Structural Problem Nobody's Solving

Nolan touches on something else that's worth emphasizing: the structural reality of how filmmaking works at scale.

A television show is not a script. A film is not a screenplay. These documents are the beginning of a process that involves hundreds of decisions made by dozens of people over months or years.

A cinematographer decides where the camera goes, what lens to use, how light behaves in a scene. A production designer decides what fills the frame. A costume designer decides what characters wear and what that communicates about their economic status and emotional state. A composer decides how music shapes emotional response. Actors decide how to interpret dialogue, what emotional notes to hit, and how to behave in ways the script never specifies.

Each of these decisions represents creative input that's essential to the final result.

AI can assist with some of these decisions. It can generate costume designs. It can suggest color grades. It can generate music. But it cannot currently coordinate across all of these disciplines in the way that a film or television production requires.

Moreover, there's no reason to believe it will be able to do so soon. The challenge isn't technical. It's conceptual. Film and television are fundamentally collaborative media that emerge from the intersection of hundreds of creative decisions made by people with deep expertise in their specific disciplines.

AI doesn't have that expertise yet. It has pattern-matching capabilities and the ability to generate statistically likely outputs. That's different.

Nolan seems to understand this deeply, which is why his concern about AI in filmmaking is so different from the reflexive panic. He's not worried AI can't work. He's concerned about what happens if it can work well enough to seem sufficient, even when it's actually diminishing creative quality.

The Business Model Question

While Nolan doesn't spend much time discussing the economics of AI in entertainment, his comments hint at real structural concerns.

The studio system has survived for nearly a century because it solved specific problems. It aggregated capital, managed risk, and created systems for coordinating complex creative production. For all its flaws, it worked.

AI potentially disrupts this model in ways that nobody's fully reckoned with.

If AI can reduce production costs by even 30%, that's meaningful. If it can do that while maintaining quality standards that audiences accept, then the entire economics of the film and television business change. Studios wouldn't need to spend

This is where Nolan's caution becomes important. He's not saying the economics will definitely change. He's saying we're in a "frothy moment" where people are experimenting with possibilities, many of which won't pan out. But some will.

For creators like Nolan who've built careers within the existing system, this is genuinely uncertain territory. The skills that made him successful—his ability to write complex screenplays, his understanding of episodic television production, his collaborative relationships with actors and directors—remain valuable. But the context in which those skills operate might change dramatically over the next five to ten years.

That's why his caution isn't pessimism. It's realism.

What Nolan Actually Thinks About the Future

Pulling back, Nolan's actual position on AI seems to be something like this:

AI is genuinely capable of assisting with certain creative tasks. It will probably help people who currently can't afford to make movies. It might shift economics in the industry in ways that benefit some people and disadvantage others. But it won't replace human creativity in the near term, and it shouldn't, because human creativity has value specifically because it's human.

This is a moderate position, which might explain why it sounds so reasonable compared to much of the discourse around AI in entertainment.

He's not a techno-optimist convinced AI will revolutionize cinema. He's not a technophobe convinced AI should be banned. He's someone who's spent twenty years working at the highest levels of entertainment, observing how the industry actually functions, and making educated guesses about what technology can and cannot do to that system.

When he says he won't use AI in his own writing, he's not making a universal claim about AI's value. He's making a specific claim about his own creative process. When he suggests AI could help new filmmakers, he's not claiming it will solve inequality in entertainment. He's acknowledging that it could reduce certain barriers.

This precision matters. It's the difference between hype and analysis.

The Surveillance Software Parallel

Person of Interest was ahead of its time because Nolan understood something about technology: the tools we create to solve problems inevitably solve other problems too, often unintended ones.

The surveillance software in Person of Interest was created to stop crimes before they happened. It did that. But it also created a massive database of information about millions of people. It solved the crime problem while creating a privacy problem.

AI in entertainment will probably follow a similar pattern. It will solve certain problems—cost reduction, faster iteration, accessibility for new creators—while simultaneously creating new problems we haven't fully anticipated yet.

Those problems might include labor displacement, quality degradation that audiences eventually rebel against, or a homogenization of content because AI-generated work tends toward statistical averages rather than genuine originality.

Nolan doesn't dive deeply into these concerns in the interview, but they're implicit in his caution. He understands that technology doesn't just add capabilities. It changes systems.

The Generational Divide

There's something worth noting about who Nolan is in relation to AI discourse in entertainment.

He's not a young filmmaker discovering AI as a tool to achieve ambitious visions with limited resources. He's not a studio executive desperate to reduce costs and increase profit margins. He's someone who achieved success in a different technological context—one where those tools didn't exist—and is now observing new tools with informed skepticism.

This probably makes him more thoughtful than either of the other positions, simply because he doesn't have a financial stake in pretending AI is either universally good or universally bad.

Younger filmmakers might legitimately see AI as a pathway to creative expression they couldn't otherwise achieve. That's not nothing. But Nolan's skepticism about whether that creative expression will have the depth and authenticity that cinema currently values is worth taking seriously.

He's not wrong that we're in a frothy moment. Hype cycles in technology are real, and they usually involve massive overestimation of short-term capabilities and underestimation of long-term challenges. AI in entertainment is probably no exception.

What This Means for the Industry Going Forward

If we take Nolan's perspective seriously, several implications emerge.

First, the AI in entertainment story is more complicated than either the hype or the panic suggests. Neither universal optimism nor universal pessimism maps onto reality.

Second, the impact of AI will probably vary significantly by context. For independent filmmakers, it might be genuinely transformative. For studio films, it might be mostly marginal, useful for specific tasks rather than systemic transformation.

Third, the quality and authenticity of human-created content might become increasingly valued precisely because AI becomes ubiquitous. This could strengthen prestige television and films made by established auteurs while creating a wasteland of generic AI-assisted content.

Fourth, the structural economics of the industry could shift in ways that currently seem unimaginable. If costs drop dramatically, the entire system of how studios greenlight and produce content might fundamentally change.

None of this is certain. That's Nolan's point about the "frothy moment." We're in a period of experimentation and uncertainty. The outcome depends on how technology develops, how audiences respond, how creators adapt, and how the industry responds to all of those factors.

Nolan's contribution is to inject some clarity and nuance into what's often a murky debate. He doesn't claim to know the future. He's just been around this business long enough to know that the simple stories—"AI will save cinema" or "AI will destroy cinema"—rarely capture how technology actually transforms industries.

The Practical Reality for Creators Today

For creators working right now, Nolan's perspective suggests a few practical takeaways.

First, don't panic. AI is not currently at a capability level where it can replace the kind of work Nolan does. That doesn't mean it never will, but it means you have time to adapt and to make informed decisions about when and how to use these tools.

Second, don't assume AI is useless for your work. It might be valuable for specific tasks—research, brainstorming, generating preliminary dialogue that you then rewrite, creating visual mockups of concepts. The key is understanding where human judgment and creativity remain essential.

Third, protect your voice. This is Nolan's implicit point when he says he won't use AI in his writing. Your unique perspective and creative voice are assets. Tools that homogenize output or make you sound more like statistical averages of other writers are tools that diminish those assets.

Fourth, stay informed about how the industry is actually changing, not how hype suggests it might change. The frothy moment includes a lot of noise. The signal is harder to detect.

Fifth, understand that the impact of AI will vary by your context. If you're a solo filmmaker with limited resources, AI might unlock possibilities that were previously impossible. If you're already working at high levels within established systems, the calculus is different.

Why This Conversation Matters More Than You Think

Nolan's willingness to engage with AI as a serious topic without either panicking or overselling it is rare in entertainment discourse.

Most conversations about AI in film and television fall into two categories. Either people insist that AI will revolutionize everything and anyone worried about it is a Luddite, or people insist that AI is an existential threat and anyone willing to engage with it is a sellout.

Both positions miss something crucial: AI is a tool, and like all tools, its impact depends entirely on how it's used, what context it's used in, and what humans decide to do with it.

Nolan's perspective—careful, historically informed, skeptical of both hype and panic—offers a model for how to think about technology in creative fields. Not as inevitable fate, but as capability that humans will deploy in ways that serve various interests.

The frothy moment will eventually settle. When it does, filmmaking will probably look somewhat different than it looks now. But it probably won't look as different as either the boosters or the skeptics suggest.

Nolan gets this. He's betting his continued career on the idea that human-created content will continue to matter, that unique perspectives will continue to have value, and that the tools of filmmaking might evolve without fundamentally transforming what filmmaking is.

Time will tell if he's right. But he's definitely thinking about the problem with more nuance than most.

FAQ

What did Jonathan Nolan say about AI in filmmaking?

Nolan described the current moment as a "frothy" period of hype and experimentation around AI in entertainment. He acknowledged that AI could help aspiring filmmakers reduce barriers to entry while remaining skeptical that it will fundamentally transform professional filmmaking or replace human creativity in the near term. He was clear that he personally will never use AI in his own writing despite understanding its potential applications.

Will AI replace human screenwriters and filmmakers?

According to Nolan's perspective, AI is unlikely to completely replace human filmmakers in professional contexts, particularly for prestige television and major films where audiences expect unique creative vision and emotional authenticity. However, he concedes that AI could assist with specific tasks and might eventually shift the economics of film production in ways that affect how the industry functions.

How could AI help new and independent filmmakers?

Nolan suggests AI could democratize filmmaking by reducing barriers that currently require significant financial investment. New filmmakers could use AI tools to generate visual effects, create backgrounds, and develop preliminary versions of their work without the traditional costs associated with hiring crews, renting equipment, or purchasing expensive software licenses. This doesn't create professional-quality films equivalent to studio productions, but it could enable storytelling that was previously impossible without resources.

Why did Nolan say he won't use AI in his writing?

Nolan explained that using AI assistance would fundamentally change his creative process. His writing approach relies on the iterative struggle with language, the discovery of unexpected connections between ideas, and the resistance that comes from working within the constraints of his own knowledge. AI assistance would remove these constraints, which would change the type of output he produces rather than simply accelerating his existing process.

What is the "frothy moment" Nolan referenced?

The frothy moment refers to the current period of AI development in entertainment, characterized by significant hype, wild experimentation, and inflated expectations about what AI can accomplish. Nolan suggests that this unstable period will eventually settle into a more realistic understanding of AI's actual capabilities and limitations in filmmaking, similar to how other technology hype cycles have progressed historically.

What does this mean for the future of the film and television industry?

Based on Nolan's analysis, the impact of AI will vary significantly by context. Independent filmmakers might find AI genuinely transformative for accessing creative expression previously unavailable to them. Studio films might experience marginal improvements in specific tasks rather than systemic transformation. The industry could see shifts in economics and production models, but human creativity and unique creative vision may become increasingly valued as AI-generated content becomes more common.

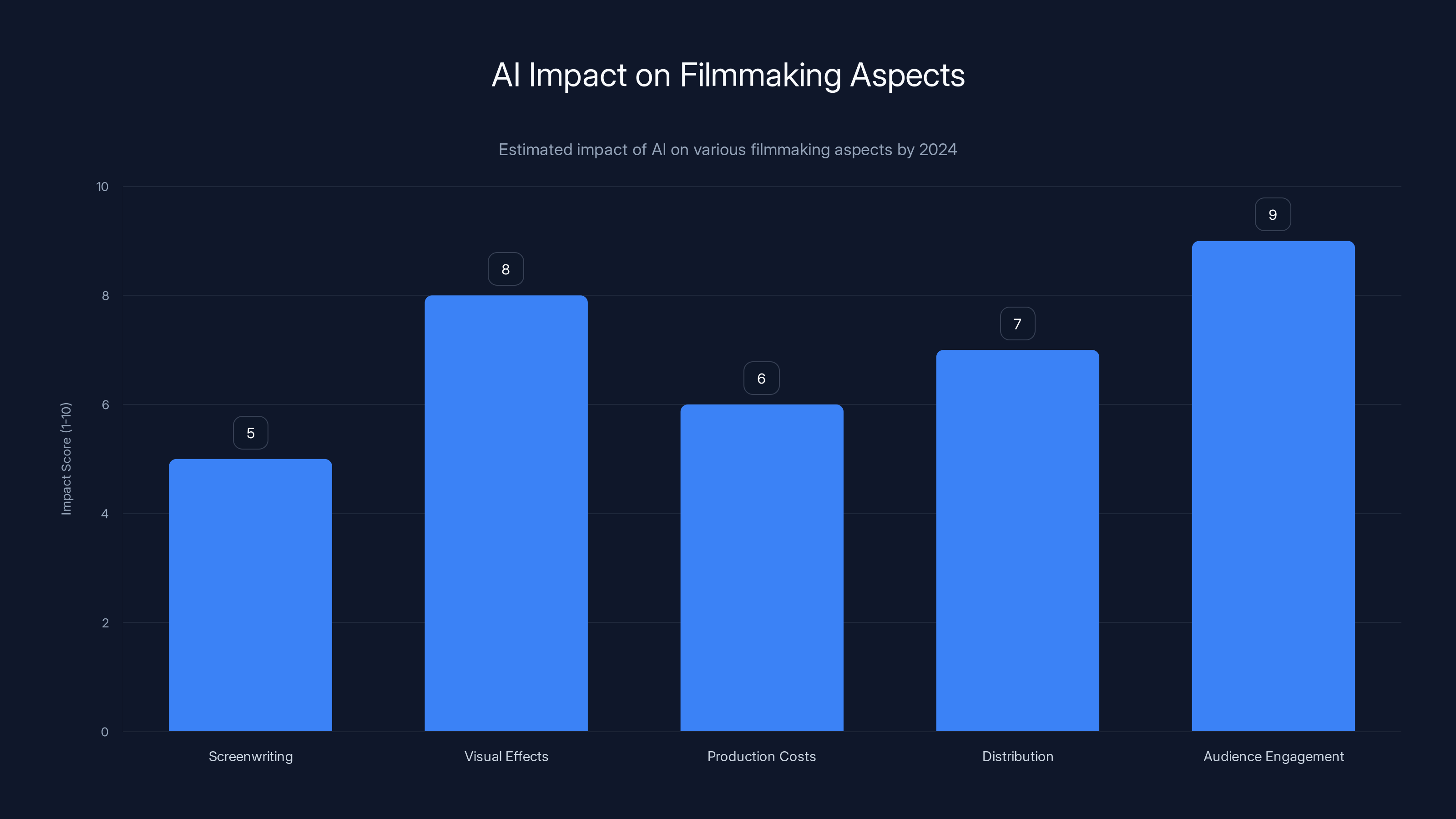

AI is expected to significantly enhance visual effects and audience engagement, while moderately impacting screenwriting and production costs. Estimated data.

TL; DR

-

Frothy, Not Revolutionary: Jonathan Nolan describes the current AI moment as inflated with hype and experimentation rather than representing genuine transformation of filmmaking as we know it.

-

Help for New Creators: AI could meaningfully lower barriers to entry for independent and aspiring filmmakers who currently lack resources for professional equipment and crews.

-

Not for Studio Films: AI is unlikely to fundamentally replace human creativity in prestige television or major films where audiences value unique perspectives and emotional authenticity.

-

Personal Refusal: Nolan explicitly stated he will never use AI in his own writing because it would fundamentally alter his creative process in ways that would diminish rather than enhance his work.

-

Structural Uncertainty: The long-term impact of AI on the entertainment industry remains genuinely uncertain and will depend on how technology develops, audience responses, and industry adaptation rather than predetermined outcomes.

-

Bottom Line: AI in filmmaking is neither a universal savior nor an existential threat, but rather a tool whose impact will vary significantly depending on context, creator intent, and how the industry chooses to deploy it over the next several years.

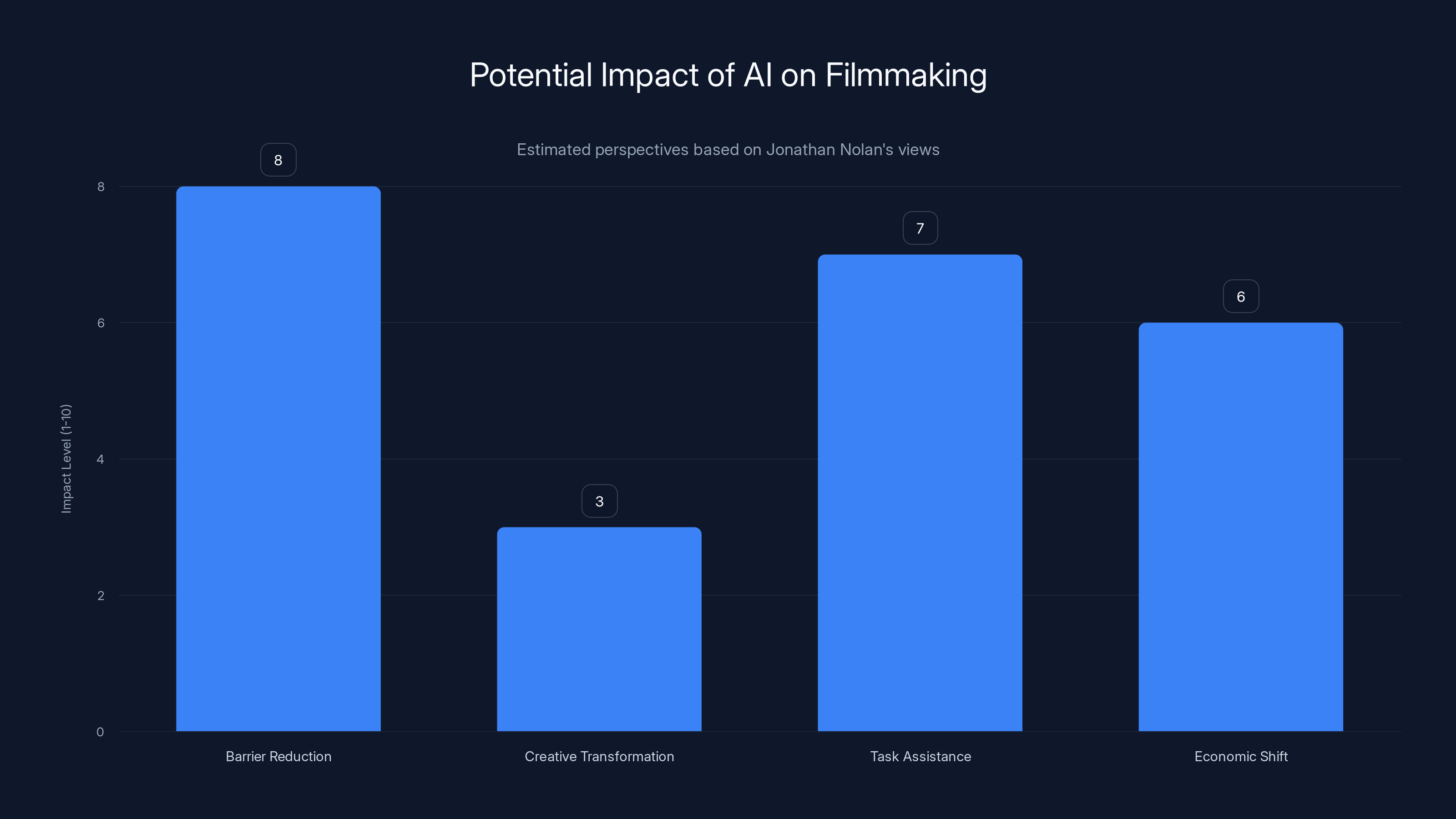

AI is seen as a tool to reduce barriers for new filmmakers and assist with tasks, but it's unlikely to transform creativity or replace human filmmakers in professional contexts. (Estimated data)

Key Takeaways

- Jonathan Nolan describes the current AI moment as 'frothy'—full of hype and experimentation rather than representing genuine transformation of filmmaking

- AI could meaningfully lower barriers for independent filmmakers while having minimal impact on professional studio productions requiring teams of specialized professionals

- Nolan personally refuses to use AI in writing because it would fundamentally alter his creative process in ways that diminish rather than enhance his work

- The uncanny valley applies to AI-generated creative content, where audiences instinctively detect something off about work that's almost but not quite authentic

- Film and television are fundamentally collaborative media requiring hundreds of coordinated creative decisions that AI cannot yet execute in concert

![Jonathan Nolan on AI in Filmmaking: The Complete Analysis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/jonathan-nolan-on-ai-in-filmmaking-the-complete-analysis-202/image-1-1770122343702.jpg)