Introduction: When Sports Leagues Go After VPNs

Last month, something quietly dramatic happened in Spanish courtrooms. La Liga, the professional association for Spain's top football league, won a court order forcing Nord VPN and Proton VPN to block access to illegal streaming sites within Spain's borders. Sounds straightforward, right? One of the world's biggest sports organizations cracking down on piracy. But here's where it gets complicated.

Neither company has actually been notified of the order yet. The court order exists. It's legally binding. But the VPN companies don't know the specific details of what they're supposed to block, how to block it, or even officially that it applies to them. This is the kind of legal tangle that reveals something fundamental about how the internet actually works versus how regulators think it does.

What started as a straightforward copyright enforcement issue has become a case study in the collision between traditional legal authority and the decentralized nature of digital infrastructure. For anyone using a VPN in Spain, considering buying one, or just curious about how technology intersects with law, this matters. A lot.

The implications ripple outward too. If this approach works in Spain, other countries will notice. The EU is already watching. Tech companies are already preparing. And everyday internet users are caught in the middle, wondering if their privacy tools are about to become less reliable.

Here's what you need to know about what's happening, why it matters, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- La Liga won a court order in Spain requiring Nord VPN and Proton VPN to block illegal streaming sites, but neither company has been formally notified

- Dynamic blocking technology could disconnect legitimate users during La Liga matches if implemented incorrectly

- VPN companies argue the order is technically impossible to comply with without compromising security and privacy protections

- Spain's courts are pushing ahead despite these objections, setting a precedent for other EU nations

- The real issue: Governments treating VPNs like ISPs, when they're fundamentally different technologies with different capabilities

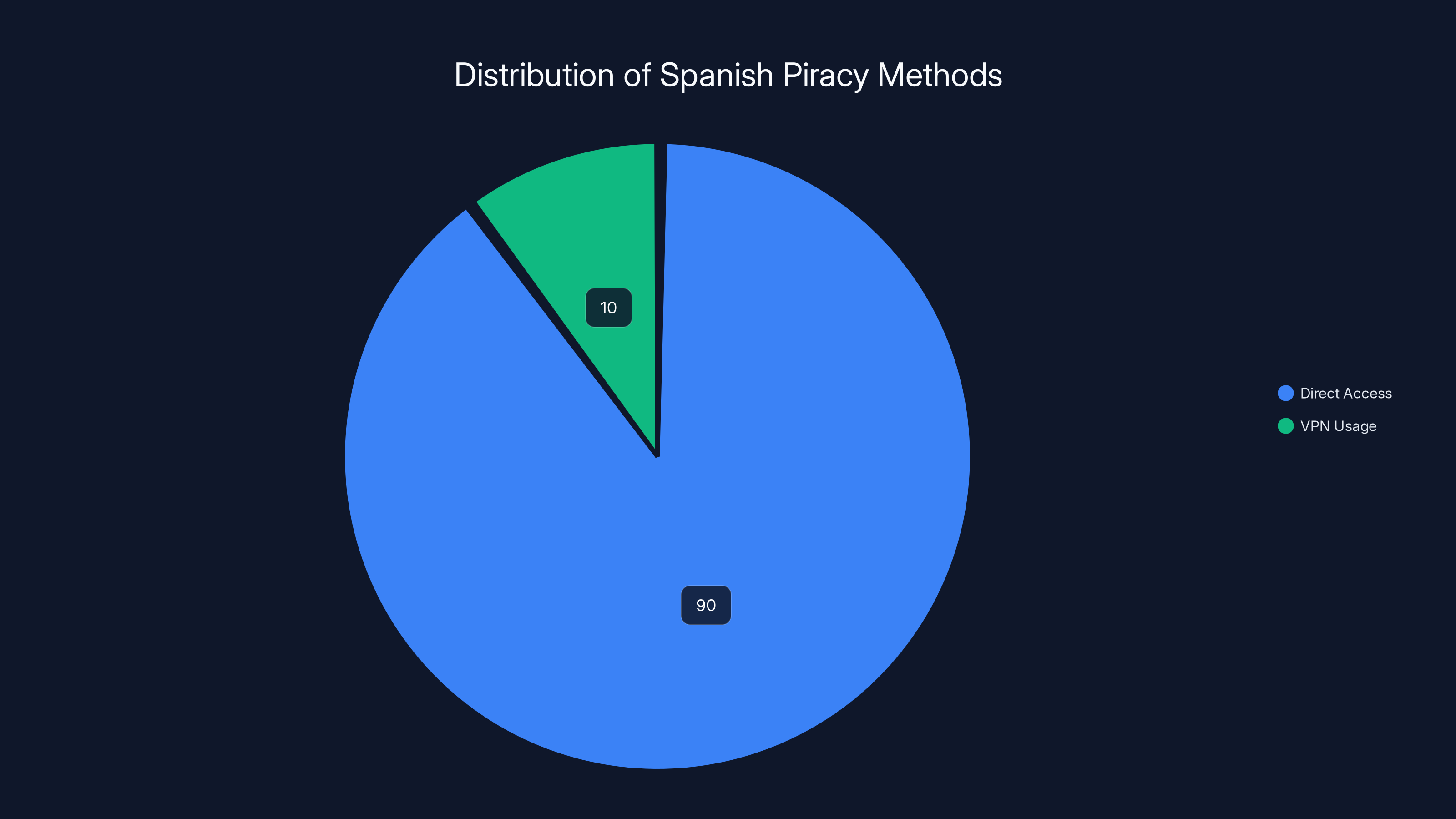

An estimated 90% of piracy in Spain occurs through direct access to piracy sites, with only 10% using VPNs. This highlights that VPN blocking may not significantly impact overall piracy rates.

The La Liga Court Order: What Actually Happened

In October 2024, Spanish courts issued what's being called a "dynamic" blocking order. The term itself is revealing. Traditional court orders are static: they name specific websites, specific dates, specific actions. This one is different. It requires blocking technology to adapt in real-time as illegal streams migrate to new domains, new IP addresses, and new hosting providers.

La Liga identified the problem clearly enough. Illegal streaming costs them millions in lost licensing revenue. Fans in Spain were accessing matches through VPN-enabled piracy sites rather than paying for legitimate subscriptions. From their perspective, the VPN services were enabling the theft of their content.

But here's what makes this different from your typical ISP blocking order (which Spain has done before): Nord VPN and Proton VPN don't operate like traditional internet service providers. They're not routing traffic through servers they control in Spain. They're encrypted tunnels that route traffic through servers in other countries. The architecture is fundamentally different.

The court order doesn't specify how the blocking should happen. That's intentional—and also problematic. Courts assume technology companies can figure out the implementation details. But VPN companies are saying: "We can't block specific content without breaking our entire security model."

This creates a fundamental contradiction. VPN services encrypt all traffic equally. If they start carving out exceptions for certain sites, they're no longer providing universal encryption. They're creating a backdoor. And once that backdoor exists, other governments, hackers, and bad actors will want to use it.

How VPN Technology Actually Works

Understanding why this court order is technically problematic requires understanding what VPNs actually do. Most people think of a VPN as a privacy tool. That's true, but it's incomplete.

When you connect to a VPN, your device encrypts all outgoing traffic and sends it through a VPN server. That server decrypts the traffic, makes the actual web request, and sends the response back through the encrypted tunnel. To the websites you visit, it looks like you're accessing them from the VPN server's location—not your actual location.

But here's the technical detail regulators miss: the VPN company never sees the unencrypted content of your traffic. They see encrypted packets. They can see that a packet went somewhere, and roughly how large it was. But they can't see what's inside it.

This is intentional. It's the entire point of VPN encryption. If the VPN company could see your traffic, they could monitor what websites you visit, what searches you do, what messages you send. The moment you enable that visibility, the VPN is compromised.

So when a court says "block access to these websites," it's asking for something that appears simple but is architecturally impossible without fundamentally changing how VPNs work.

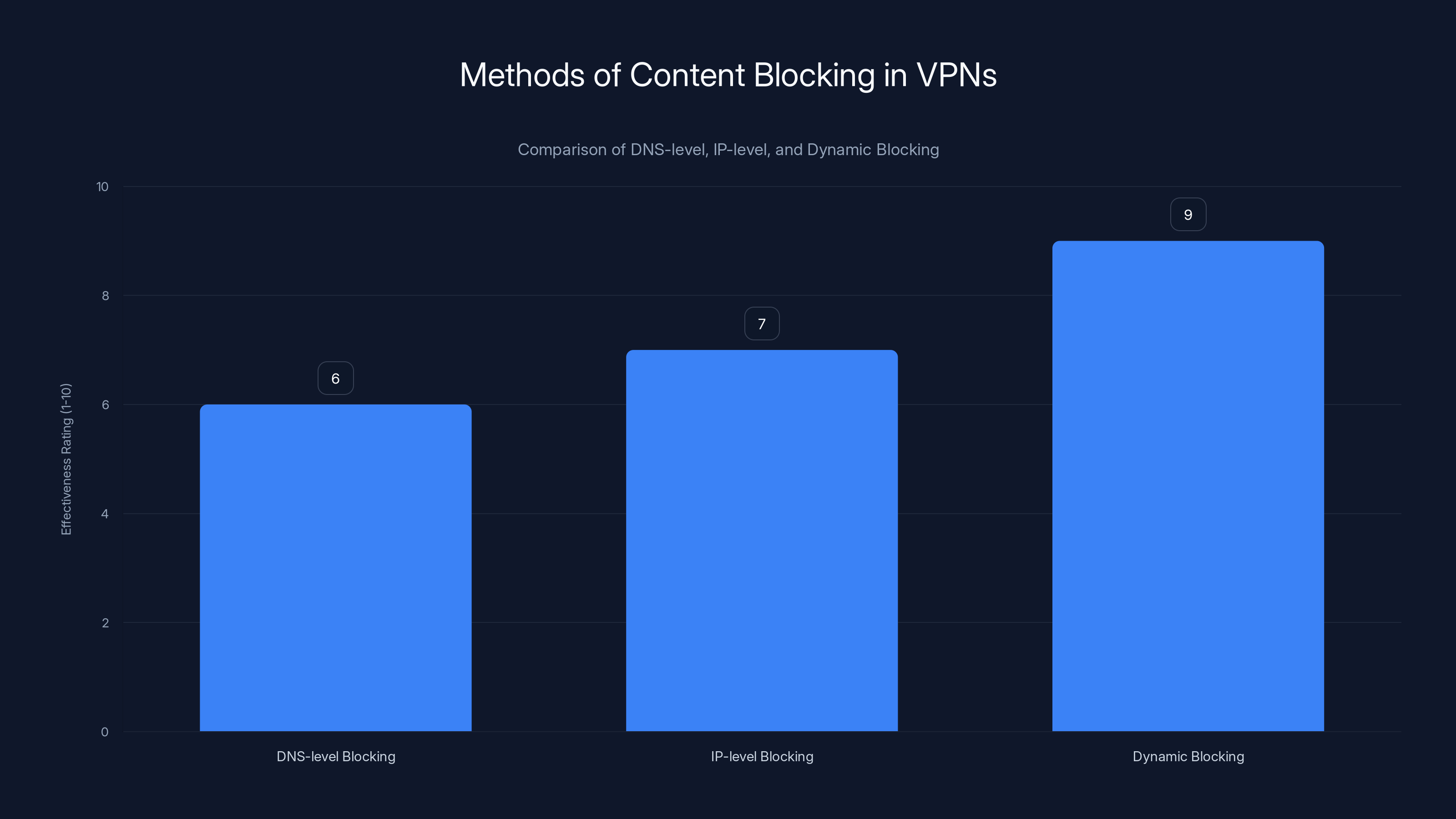

There are technically three ways to block content:

DNS-level blocking intercepts domain name requests and doesn't resolve them. You type in a domain, the VPN's DNS server doesn't translate it to an IP address, and the site doesn't load. This works without seeing traffic content.

IP-level blocking prevents connections to specific IP addresses. Again, no content inspection needed.

Deep packet inspection looks inside encrypted traffic. This would require decryption, which destroys the entire security model of a VPN.

La Liga is implicitly asking for something between the first two options. But there's a problem: illegal streaming sites are constantly changing domains and IP addresses. Every time law enforcement blocks one, the pirates set up another. Dynamic blocking would need to happen in near real-time.

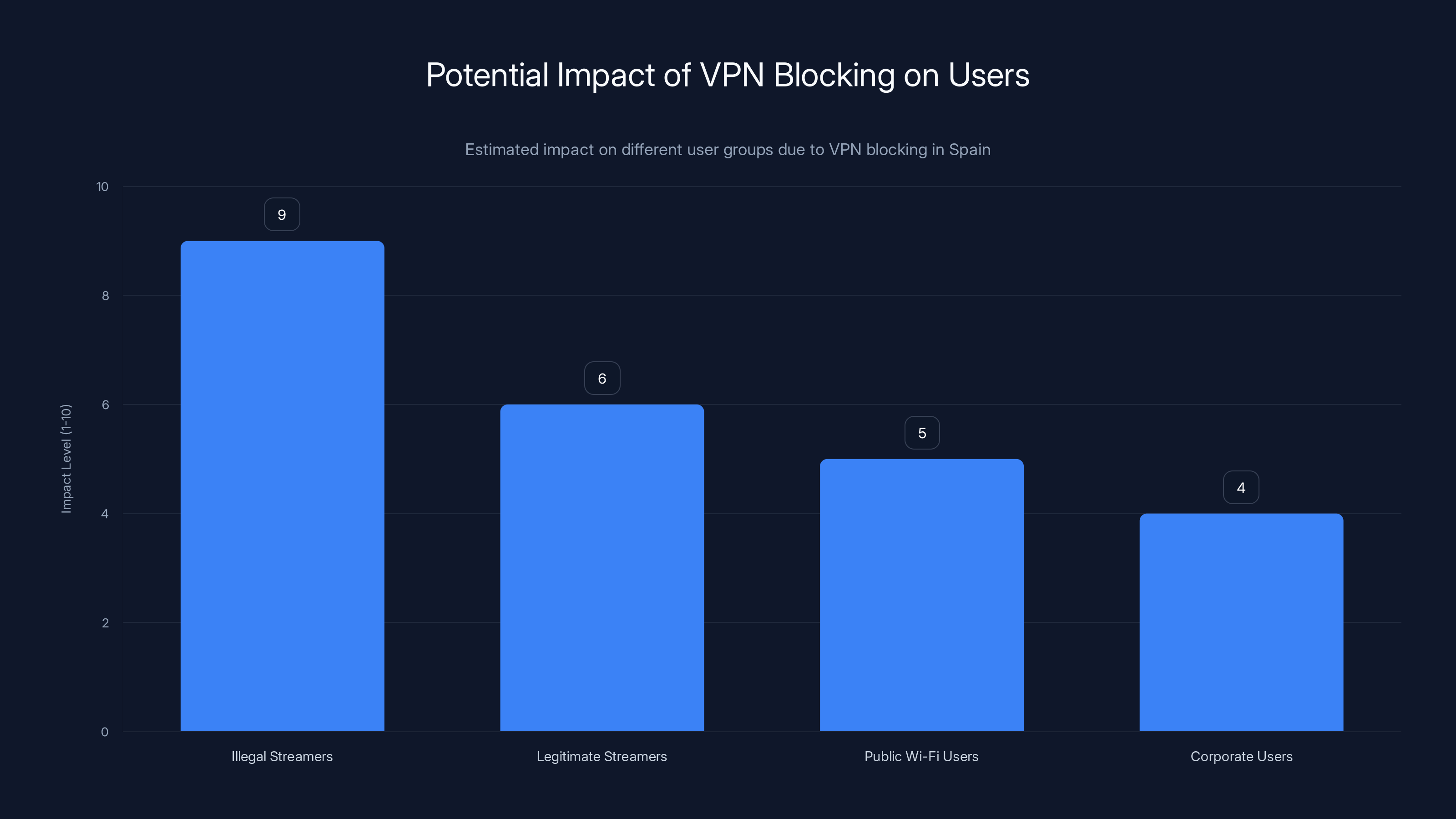

Estimated data suggests illegal streamers will be most affected by VPN blocking, while legitimate users may face moderate disruptions.

Why Nord VPN and Proton VPN Haven't Been Notified Yet

This is where the story becomes almost absurd. The court issued an order. A major sports organization won an enforcement victory. But the companies that are supposed to comply don't actually know about it.

Here's what happened: La Liga's lawyers filed the case, presented arguments, and won. The court issued its order. But there was no mechanism to formally notify the VPN companies. No official service of process. No direct communication from the court to the companies.

Some reports say La Liga was supposed to notify them. Other reports suggest the court was supposed to. The result is that both Nord VPN and Proton VPN learned about the order through the same channels as everyone else: news reports.

Both companies issued public statements saying they hadn't been formally notified and therefore couldn't comply—not because they're refusing, but because they don't have official details about what, specifically, they're supposed to block.

This lack of notification is actually revealing. It suggests that Spanish courts may not have a well-developed process for serving enforcement orders to international tech companies. They have procedures for notifying local businesses. They have procedures for notifying multinational corporations with Spanish subsidiaries. But serving an order to a VPN company based in Panama (Proton) or possibly other jurisdictions is outside their normal playbook.

The court essentially issued an order into the void, assuming the companies would somehow find out and comply. When they found out through news reports instead, the legitimacy question immediately surfaced: how can we be expected to comply with an order we haven't officially received?

The Technical Impossibility Problem

Let's get concrete about why this is technically difficult. Proton VPN's official response was careful but clear: they cannot comply without compromising their security architecture.

Here's a specific scenario. It's a Thursday evening in Madrid. Athletic Club is playing Real Madrid. The match is being illegally streamed on five different domains. La Liga wants those domains blocked through VPN services.

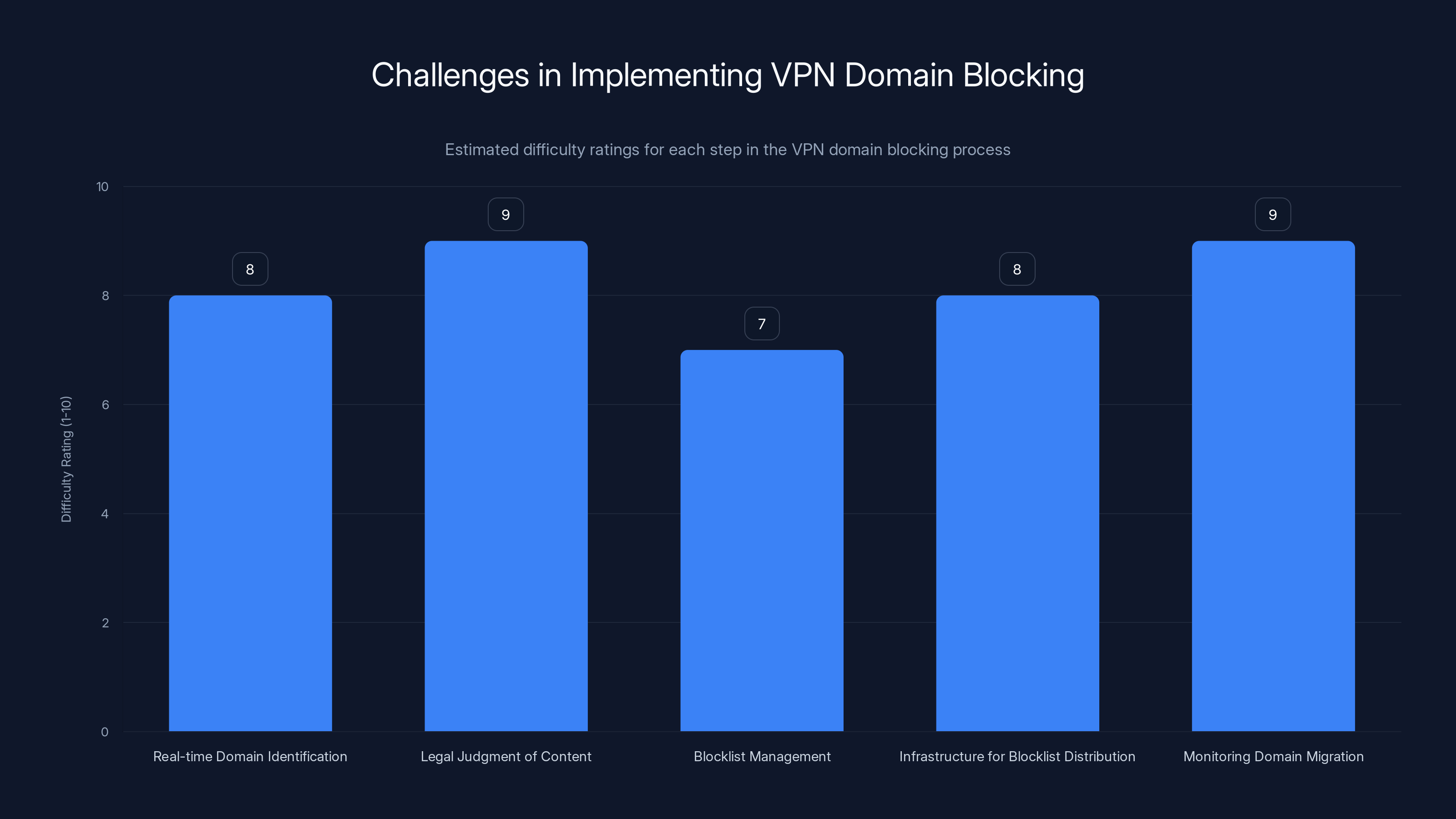

Proton VPN would need to:

- Identify the five domains in real-time

- Determine they're illegal streams of La Liga content

- Add them to a blocklist

- Push that blocklist to all VPN servers serving Spanish users

- Implement DNS or IP blocking across that infrastructure

- Monitor for when pirates migrate to new domains (which happens within hours)

- Repeat the entire process

Each of these steps has problems.

Identifying domains in real-time requires monitoring. Who does the monitoring? Proton would need staff watching for new streams constantly. That's expensive. Nord VPN would face the same cost.

Determining they're illegal requires making a legal judgment. Is the content being streamed actually owned by La Liga? Is the stream licensed or not? VPN companies are not courts. They're not equipped to make these determinations. But if they block the wrong streams, they're liable for damages.

Adding to a blocklist sounds simple. But if the blocklist becomes very large, it slows down DNS resolution. Every VPN user connecting to a server has to query that blocklist. Performance degrades.

Pushing blocklists to all servers requires infrastructure. Nord VPN operates servers in 60+ countries. Proton VPN operates in 100+ countries. Updating all of them in real-time is complex.

Monitoring for migration is the hardest part. Pirates don't wait politely for blocking. They automate domain rotation. New domains come online before old ones are even blocked. The VPN companies would be in an endless, losing battle.

The court order doesn't address any of this. It assumes blocking "just works." But it doesn't. Not without compromising the fundamental security of the VPN service itself.

The Collateral Damage Problem: Legitimate Users Get Disconnected

Here's what keeps privacy advocates up at night about this case. If Nord VPN or Proton VPN implement overly aggressive blocking, legitimate users will get caught in the crossfire.

Imagine you're in Barcelona. You're a paying subscriber to DAZN, a legitimate sports streaming service. You use your VPN because you're on public Wi-Fi at a café and you want privacy. But the VPN's blocking system makes a mistake. It flags your DAZN connection as suspicious. Your entire VPN tunnel gets disconnected. Your session ends. You have to reconnect, losing your stream.

Or worse: imagine the VPN's blocklist is so aggressive that it prevents any connection to sports streaming sites, even legitimate ones. You lose access to services you actually paid for.

There's also the "database problem." If the VPN company maintains a database of blocked domains, that database becomes a target. Hackers want access to it. Governments want access to it. The moment that database is compromised, so is the entire blocking system. And more dangerously, any other lists that are stored alongside it—like user connection logs.

There's also the precedent issue. If Nord VPN implements blocking for La Liga, what's to stop the next Spanish court from ordering blocking for other content? Political content? Journalistic content? Religious content?

VPN companies argue—correctly—that once you start carving exceptions, you've opened the door to endless carving. The security model breaks. The privacy protection breaks. And legitimate users suffer.

The process of blocking illegal streams through VPNs involves multiple challenging steps, with legal judgment and monitoring domain migration being particularly difficult. (Estimated data)

Why Courts Think This Should Be Easy

Spanish courts aren't being unreasonable. They're following a logical progression. ISPs in Spain have been blocking illegal content for years. The courts issue orders. ISPs comply. Content gets blocked. This is the normal process.

But VPNs aren't ISPs. The court seems to be treating them as if they are. It's a category error, but an understandable one. From a judge's perspective, both VPNs and ISPs are network services. Both route traffic. Both can theoretically decide what traffic to route. So the legal framework for one should apply to the other.

Except it doesn't. ISPs maintain records of which customer requested which domain. They can match a domain request to a user account and then decide whether to block it. ISPs have transparency, even if users don't like that transparency.

VPNs are designed to prevent exactly that capability. The entire point is that even the VPN company doesn't know who is accessing what. If you could identify users and their traffic, you've destroyed the privacy model.

The court also might be thinking about technical capability in a way that doesn't match reality. Judges often assume that if technology X exists, it can be implemented anywhere. But context matters. A blocking system that works for an ISP with centralized infrastructure doesn't work for a VPN with distributed infrastructure.

How Other Countries Are Watching This

Spain didn't invent VPN blocking. But it's becoming one of the first European nations to attempt it at scale. Other countries are watching closely.

France has been aggressive on piracy enforcement. The UK has a sophisticated blocking regime through Ofcom. Germany has strong copyright protections. The EU is working on coordinated approaches through the Digital Services Act framework.

If Spain's blocking order holds up legally, if it gets implemented successfully, if it demonstrably reduces piracy without breaking VPNs, then you're going to see similar orders in every other major European market within two years.

But if it fails—if VPNs can't technically comply, if the courts have to back down, if the order becomes unenforceable—then it sets a different precedent. It shows that courts can't actually force VPN companies to change how they operate without either breaking the technology or having those companies establish Spanish subsidiaries with on-site infrastructure (which most VPN companies won't do).

The stakes are higher than just La Liga's revenue. This is about whether national courts can regulate technologies that are inherently international and decentralized. It's about whether VPN companies will be able to operate in Europe at all if they refuse to implement government-mandated blocking.

What The VPN Companies Are Actually Saying

Let's look at the official positions. Nord VPN issued a statement saying they take intellectual property seriously and comply with legitimate legal requests. But they also said they haven't received formal notification of the Spanish order and cannot comply with blocking requirements that would compromise user security.

Proton VPN was more explicit. They said that implementing the kind of dynamic blocking La Liga is requesting would require them to:

- Decrypt user traffic (which violates their core security model)

- Maintain user connection logs (which violates their privacy policy)

- Make real-time content determination judgments (which they're not equipped to do)

Proton also noted that they're based in Switzerland, which has different legal frameworks than Spain. A Spanish court order might not be enforceable against a Swiss company without going through international legal channels.

Neither company is saying "we refuse to comply." They're saying "we can't technically comply without destroying our service." There's a big difference. One is defiance. The other is honest about technical limitations.

But here's what's interesting: neither company is offering a clear path to resolution either. They're not saying "here's what we could do instead." They're basically saying "this is impossible, full stop." That puts the court in a corner. Do they accept that the companies are right? Do they order even more aggressive compliance? Do they fine the companies for non-compliance?

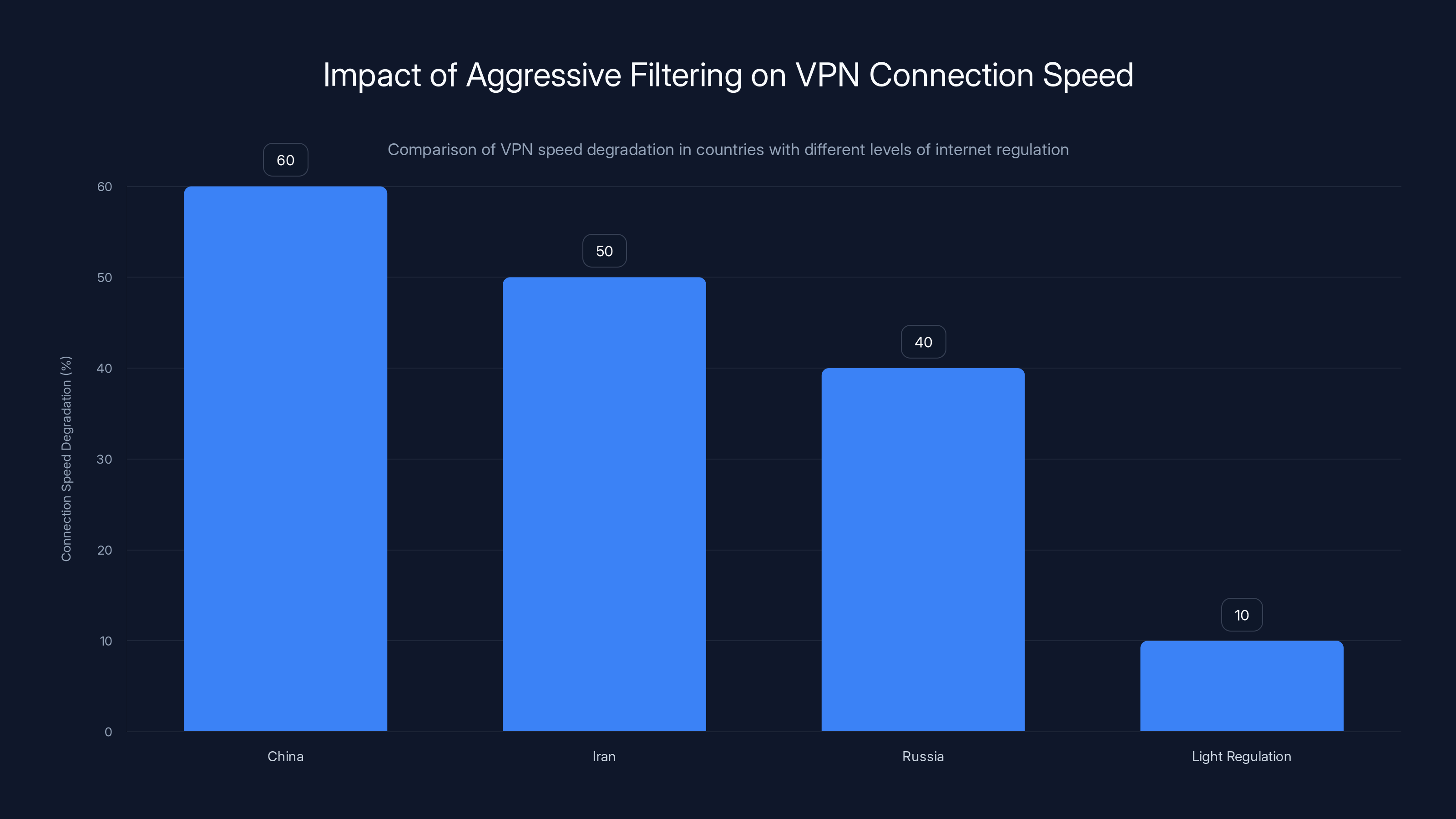

VPN users in countries with aggressive internet filtering experience 40-60% degradation in connection speed. Legal blocking orders in the EU could lead to similar effects. Estimated data based on typical scenarios.

The Precedent This Sets for Privacy and Regulation

If this order sticks—if courts in multiple EU countries start issuing dynamic blocking orders to VPN companies—the implications for privacy are serious. Not immediately, but downstream.

The first issue is normalization. Once governments see that courts can issue blocking orders to VPNs, they'll start issuing them for other things. Not just piracy. Maybe political dissent. Maybe religious content. Maybe LGBTQ+ content in countries where that's politically controversial. The Spanish court sets a precedent that can be copied and modified by courts with less noble intentions.

The second issue is arms race dynamics. VPN companies will respond by either refusing to operate in Spain (and eventually the EU), or by implementing workarounds. Some VPNs use obfuscation to hide the fact that they're VPNs. Others rotate IP addresses constantly. If blocking orders become common, VPNs will become more sophisticated at avoiding detection. The cat-and-mouse game escalates.

The third issue is user harm. Even legitimate users who have nothing to do with piracy will experience slower VPN service, more frequent disconnections, and less reliable privacy as VPN companies struggle to comply with conflicting court orders from different jurisdictions.

There's also the corporate response to consider. VPN companies might respond to aggressive Spanish regulation by pulling out of the Spanish market entirely. That would mean Spanish users who aren't doing anything illegal suddenly lose access to the privacy tool they were using.

Or they might compromise. Nord VPN and Proton VPN are both legitimate, privacy-conscious companies. They might decide that maintaining European presence is more important than maintaining perfect privacy. They might implement a European version of their service with selective blocking for piracy sites.

If that happens, users in other countries (US, Canada, etc.) would wonder: why don't we have that feature? Why is your service different in Europe? And suddenly the privacy expectations and actual privacy protections diverge across regions.

How This Connects to Broader Piracy Trends

Piracy hasn't gone away. It's just evolved. The era of Pirate Bay—a single site with millions of users—is over. That was easy to block. You block one site, millions of users have nowhere to go.

Today's piracy is fragmented. Thousands of small streaming sites. Telegram channels that share streams. Discord servers. Private forums. Automated bots that detect when a stream gets blocked and migrate to a new domain instantly.

This is why La Liga is frustrated. They can't kill piracy by killing one service. It's like trying to destroy a network by cutting random wires. The network just reroutes.

VPNs are actually a small part of the piracy problem. Most Spanish piracy users probably don't use VPNs. They're using streaming sites that are hosted on international infrastructure anyway—in Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and other regions where copyright enforcement is weak.

La Liga's real problem isn't VPN companies. It's that legitimate sports streaming in Spain is expensive. Fans want to watch matches. They're willing to pay. But if paying costs €50/month and piracy is free, some fans will choose piracy.

There are real solutions to this problem. Lower subscription costs. Offer individual match streaming without requiring season subscriptions. Stream matches on free platforms with advertising. The market-based approach actually works better than enforcement-based approaches.

But those solutions require La Liga to accept lower profit margins. Blocking orders don't require that. They just require going to court.

The Technical Reality Check

Let's be specific about what would actually need to happen if Nord VPN or Proton VPN tried to comply with dynamic blocking.

They would need to:

Set up monitoring infrastructure that constantly scans the internet for new illegal streaming domains. This would require automated detection systems, machine learning models, and significant compute resources. Cost: millions of dollars per year.

Maintain legal teams that verify whether each detected domain is actually illegal or just hosting legal content. Courts have struggled with this determination. It's not straightforward. Cost: hundreds of thousands per year.

Implement distributed blocklists that update across hundreds of servers in dozens of countries, all in real-time. This requires changes to core VPN infrastructure. Risk: if the blocklist becomes corrupted, it could block legitimate traffic globally.

Create audit trails that document what was blocked, why, and when. This creates liability—if the audit trail shows the wrong thing was blocked, the company is liable. Cost: engineering time and legal risk.

Establish appeals processes for when legitimate sites get blocked by mistake. Someone needs to review appeals, verify the facts, restore access. Cost: staff and operational overhead.

Adding all this up, implementing compliant blocking would cost a mid-sized VPN company millions of dollars per year and significant engineering effort. For one country. When the same demand will come from other countries with other sports leagues, other media companies, other content owners.

It's not impossible. It's just prohibitively expensive and creates massive liability exposure. So VPN companies are saying no.

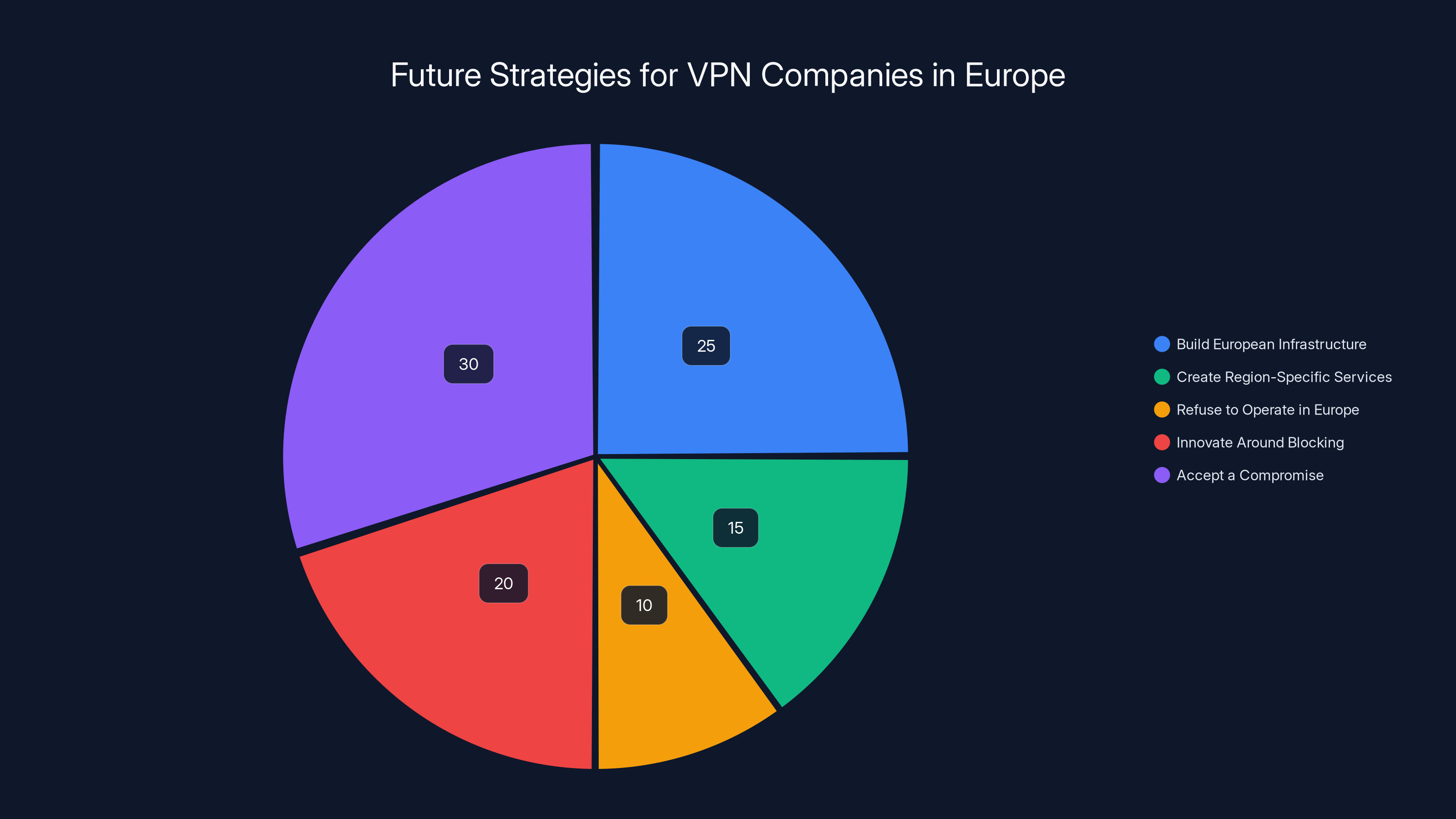

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of VPN companies might adopt a compromise strategy (30%) or build European infrastructure (25%) to comply with legal pressures.

What Happens Next: The Legal Options

Spain's court has several paths forward. They could:

Escalate the enforcement by fining Nord VPN and Proton VPN for non-compliance. But non-compliance with a technically impossible order is a weird thing to fine. It sets a precedent that courts can issue orders for impossible things and companies are liable if they can't perform magic.

Work with other EU countries to coordinate a unified blocking approach through EU regulation rather than individual court orders. This is more legitimate and might actually be enforceable, but it requires political will that might not exist.

Ban VPN services entirely in Spain if they refuse to comply with blocking orders. This is extreme and would be unpopular, but it's technically within Spain's power. However, it would likely trigger EU legal challenges and would harm legitimate VPN users.

Accept that VPN blocking isn't feasible and pursue other enforcement strategies—going after hosting providers, pursuing international legal action against piracy operators, or accepting that some level of piracy is a cost of doing business.

Compromise by creating a regulatory framework that's more realistic about what VPN companies can do. Not requiring dynamic blocking, but requiring static blocking of specifically identified sites, with clear legal procedures for notification and appeals.

My guess is that Spain will choose a combination of approaches. The court order will remain in effect, but the VPN companies will negotiate a compromise that's less aggressive than what the order technically asks for. Nord VPN and Proton VPN will implement some blocking—maybe of the worst, most obvious piracy sites—while refusing the full dynamic blocking approach.

Neither side will completely win. But both sides will declare victory.

The Broader Regulatory Context

This case doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a wave of European regulation trying to govern big tech. The Digital Services Act. Content moderation requirements. Copyright enforcement rules.

The EU is basically saying: "Tech companies, you operate in our territory, you need to follow our rules." That's a reasonable position. But the rules being demanded are often technologically naïve. Courts and legislators don't fully understand the systems they're trying to regulate.

VPN blocking is just one example. There are parallel battles over:

- Content moderation algorithms (which platforms should remove and how quickly)

- Algorithmic transparency (platforms should explain how their algorithms work)

- Data residency (data needs to stay in EU territory)

- AI regulation (AI systems need to be certified as safe)

All of these are attempts to regulate technology that's fundamentally global and decentralized. And all of them will face similar problems: the rules assume capabilities that don't technically exist, or they require choices that compromise core functionality.

VPN blocking is a testing ground. If Spain succeeds here, the EU will likely codify VPN blocking into broader regulation. If Spain fails, it signals to other countries that this approach doesn't work.

International Implications and Enforcement Challenges

Proton VPN is based in Switzerland. Nord VPN's corporate structure is more complex, but the company is international. Neither operates a Spanish subsidiary with Spanish-based servers.

This matters legally. A Spanish court order is only directly enforceable against entities operating in Spain. For international companies, enforcement becomes a matter of international legal cooperation.

So what happens if Proton VPN just... ignores the Spanish court order? The court can't arrest them (they're not in Spain). They can't seize assets (the assets are in Switzerland). They could fine the company, but how would they collect the fine?

The answer is that they would escalate to EU level, or they would threaten to block access to Spain's internet for companies that don't comply. Major tech companies can't afford to be blocked in major markets, so they usually comply with regional regulations. But if the regulation demands the technically impossible, what then?

This is where it gets interesting. Spain might be about to discover that you can't regulate technology that operates globally through national court orders. You need international agreement, or the regulations simply don't work.

Dynamic blocking is the most effective method due to its ability to adapt in real-time, while DNS and IP-level blocking are less effective as they rely on static lists. (Estimated data)

The Privacy Angle: Why This Matters Beyond Piracy

Here's what keeps privacy advocates genuinely concerned. Once you establish the principle that VPN companies must block content, the content can expand.

Today it's La Liga's illegal streams. Tomorrow it could be:

- Journalistic outlets that governments don't like

- Opposition political organizations

- LGBTQ+ resources in countries where that's illegal

- Religious content that's politically disfavored

- Whistleblowing platforms

Once the technical infrastructure for blocking exists, once courts have established they can order it, the scope of blocking will inevitably expand. It always does. Governments rarely voluntarily limit their own power.

The VPN companies know this. They're not just defending against La Liga. They're defending against the precedent that will be set if they comply.

And they're right to be worried. Countries with less respect for civil liberties are already watching. If Spain successfully forces VPN companies to implement blocking, those countries will demand the same capability for different purposes.

This is the fundamental issue. Individual court orders for individual pieces of content seem reasonable. But the system they create—where VPN companies maintain content blocklists, where courts can modify those lists, where governments have power over what VPNs block—that system is dangerous to privacy generally.

What Users Should Actually Do

If you're a VPN user in Spain, here's what you should actually do:

First, understand what you're using the VPN for. If it's privacy on public Wi-Fi, if it's accessing work resources securely, if it's avoiding ISP tracking, those are all legitimate uses. A blocking order targeting piracy shouldn't affect those.

Second, use a reputable VPN provider. Nord VPN and Proton VPN are both solid options. Fly-by-night VPN providers are more likely to comply with blocking orders without pushing back, because they don't have the resources to fight in court.

Third, document your usage. If a VPN blocking system interferes with legitimate access, you want to be able to prove it. Keep records of what you accessed, when, and why.

Fourth, stay informed. Follow news about VPN regulation in Spain and the EU. This situation will evolve, and you'll want to know what's changing.

Fifth, consider alternatives. Some people use Tor or other anonymity networks. Others use paid proxies. None of these are perfect, but they're options if VPN service degrades due to blocking requirements.

Finally, support privacy advocacy organizations. Groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and EU privacy advocates are fighting this battle. They need support to be effective.

The Piracy Problem Isn't Really About VPNs

Here's something worth stepping back to notice. VPN blocking isn't actually going to solve La Liga's piracy problem. It might reduce it slightly, but not significantly.

Most piracy happens through users accessing piracy sites directly, without VPNs. They're in countries where piracy is tolerated or difficult to prosecute. VPN blocking only affects users who are using VPNs specifically to hide their location.

That's a subset of a subset of the piracy problem. Sure, maybe 5-10% of Spanish piracy uses VPNs. But 90-95% happens without them.

So La Liga's real problem—lost revenue—won't actually be solved by this court order, even if it's successfully implemented.

The actual solution to piracy is, as always, a combination of factors:

Better pricing. Sports streaming in Spain is expensive. If matches were available for €5 per month or €2 per match, more people would pay.

Better access. If you could watch any match anytime without committing to a full season, adoption would increase.

Better convenience. The legal streaming service needs to be easier and more reliable than piracy. Often it isn't.

Enforcement. Some blocking and prosecution is still worthwhile, but it's not enough by itself.

Accepting loss. Some piracy will always exist. It's a cost of doing business in the digital world.

La Liga likely knows this. But court orders are visible and measurable. You can point to a court order and say "we're fighting piracy." You can't point to a pricing strategy and claim victory in the same way. So courts orders exist partly for optics.

The Future: What This Means for VPN Services

If VPN companies face increasing legal pressure in Europe, they have a few strategic options:

Option 1: Build European infrastructure. Some VPN companies might establish Spanish subsidiaries with Spanish-based servers. This would make them subject to Spanish court jurisdiction and able to comply with blocking orders. But it also means users lose some privacy benefits of international VPNs.

Option 2: Create region-specific services. VPN companies could offer a European version with blocking, and a global version without. Users would choose based on their priority. But this fragments the service and creates administration overhead.

Option 3: Refuse to operate in Europe. Some smaller VPN companies might just pull out of European markets. This reduces their user base but keeps their service model intact.

Option 4: Innovate around blocking. VPN companies could develop new technologies that make content blocking harder. Stealth VPN protocols, split tunneling, obfuscation. The cat-and-mouse game escalates.

Option 5: Accept a compromise. VPN companies could implement minimal blocking of obviously pirated content while refusing the full dynamic blocking approach. Courts would probably accept this as good-faith compliance.

My prediction is a combination of 1 and 5. Some VPN companies establish limited European operations to comply with blocking orders. Others implement basic blocking of clear-cut piracy sites while refusing more aggressive demands. Within five years, the European VPN market looks different than today, but VPNs still operate.

Lessons From Other Blocking Regimes

We can look at other countries to understand what happens when governments start blocking VPNs.

China effectively blocks all VPNs through the Great Firewall. But China has the technical infrastructure and legal authority to do this comprehensively. Spain doesn't.

Russia has been trying to block VPNs and Tor for years with mixed success. Users migrate to new VPN providers. The cat-and-mouse game continues indefinitely.

Iran similarly blocks VPNs, but Iranians have learned to use obfuscated proxies instead. They defeat the blocking.

Turkey has blocked specific VPN providers but not VPNs generally. The result is that new VPN providers constantly emerge.

The pattern is clear: you can block specific services, but you can't block VPNs entirely without blocking a huge amount of legitimate traffic. And blocking specific services triggers an arms race where users migrate to new providers.

Spain's approach is to block content accessed through VPNs, not VPNs themselves. That's subtly different. But it faces the same problem: you're trying to target a specific use (piracy access) while not blocking legitimate uses (privacy protection). That's technically hard.

The Argument For La Liga's Position

Here's fair points in La Liga's favor:

They're losing real money. Copyright infringement is actual theft of revenue. La Liga has legitimate interests in protecting their content.

They've exhausted other options. They've already pursued piracy sites, pursued hosting providers, and pursued ISPs. Seeking action against VPNs is logical escalation.

They're asking for reasonable compliance. From their perspective, they're just asking VPN companies to block piracy sites like ISPs do. It seems straightforward.

Piracy is genuinely harmful. It's not victimless. Content creators, athletes, and production staff depend on licensing revenue.

International regulation is needed anyway. If VPN companies are going to operate globally, they need to comply with local regulations somewhere.

These are good points. The problem isn't La Liga's goals. The problem is that the technical approach they're requesting doesn't actually work without destroying VPN privacy protections.

The Argument For VPN Companies' Position

Here's where VPNs have a point:

The order is technically impossible. Implementing dynamic blocking would require breaking encryption and monitoring user activity. That destroys the service.

The precedent is dangerous. Once you accept that courts can order content blocking through VPNs, the scope will expand beyond piracy.

They weren't properly notified. A legitimate legal order should be properly served, with clear details about what's expected.

There's no appeals process. If they block a legitimate site by mistake, what recourse do they have?

The burden is unfair. VPN companies are being asked to solve Spain's piracy problem using tools that will harm their legitimate users.

International enforcement is murky. It's unclear whether Spanish courts can actually enforce an order against an international company.

These are also good points. The VPN companies are defending something important: the technical integrity of their service and the principle that courts can't issue impossible orders.

FAQ

What is the La Liga VPN blocking court order?

It's a Spanish court order requiring Nord VPN and Proton VPN to implement "dynamic blocking" of illegal streaming sites carrying La Liga football matches. The order is meant to prevent users from accessing pirated streams through VPN services, but the VPN companies have argued that implementing such blocking would compromise their encryption and privacy protections.

How does VPN blocking actually work technically?

VPN blocking typically happens at the DNS level (preventing domain resolution) or IP level (blocking specific addresses), without requiring the VPN provider to see the contents of encrypted traffic. However, implementing real-time, dynamic blocking of constantly-migrating piracy sites would be far more complex and potentially require compromising the security model that makes VPNs valuable in the first place.

Can Nord VPN and Proton VPN actually comply with this order?

According to both companies' statements, they could implement basic blocking of specifically-identified domains, but implementing true dynamic blocking—automatically identifying and blocking new domains as pirates move them—would require capabilities they're not equipped to provide, including real-time content identification and user activity monitoring, both of which would undermine privacy protections.

Will this affect legitimate VPN users in Spain?

Potentially, yes. If VPN companies implement overly aggressive blocking systems to comply with the order, legitimate users accessing legal sports streaming services or other protected sites might experience disconnections or blocked access. Users on public Wi-Fi trying to access their work resources through VPN could also be affected if the blocking system is too broad.

Why haven't Nord VPN and Proton VPN been formally notified of the order?

The exact reason isn't entirely clear, but it appears Spanish courts lack established procedures for formally serving court orders to international VPN companies. The VPN companies learned about the order through news reports rather than official legal channels, which they've argued is problematic for compliance purposes.

Could this approach work for other types of content?

Yes, and that's a primary concern for privacy advocates. Once the legal principle that courts can order VPN content blocking is established, the framework could potentially be extended to blocking political dissent, religious content, journalistic reporting, or other protected speech in countries with weaker civil liberties protections.

What other countries are likely to follow Spain's approach?

Other major European nations with aggressive copyright enforcement, including France, Germany, and the UK, are likely monitoring this situation closely. If Spain successfully implements VPN blocking, it would provide a legal template for similar orders in other EU countries, potentially leading to a coordinated European approach.

How is this different from ISP blocking of piracy sites?

ISPs maintain centralized records of which customer accessed which site, making blocking decisions straightforward from an administrative perspective. VPNs are designed to prevent exactly that capability—the entire point is that even the VPN provider doesn't know what users are accessing. Asking a VPN to block specific content is asking it to abandon its core privacy function.

Could VPN companies just move their infrastructure out of Europe?

Some might, which would mean European users lose access to those services. Others might establish limited European operations to comply with local orders while maintaining privacy-respecting services in other regions. Neither solution is ideal from either a user privacy or corporate efficiency perspective.

What would actually solve La Liga's piracy problem?

Market-based solutions are likely more effective than enforcement alone. Lower subscription costs, better legal streaming options, individual match purchasing rather than season subscriptions, and free streaming with advertising have all proven more effective at reducing piracy than blocking and litigation in other media sectors like music and film.

Conclusion: The Real Question Being Tested

On the surface, this is about La Liga protecting their intellectual property. And it is that. But underneath, it's testing something much bigger: can national legal systems regulate fundamentally global technologies?

VPNs are decentralized by design. They're meant to work internationally. They're meant to prevent single points of control. When a Spanish court tries to regulate them through a court order, it's running up against the architectural reality of how VPNs work.

Spain can win this individual case. They can fine the companies. They can escalate through EU channels. But they can't actually force VPN companies to build something they don't want to build, especially if building it would destroy the value of their product.

What Spain can do is create enough regulatory burden that some VPN companies leave the market or compromise their standards. But that hurts legitimate users more than it hurts pirates.

The lasting lesson from this case won't be about La Liga or football streaming. It will be about the limits of regulatory authority in a world where technology operates at a scale and complexity that national legal systems can barely comprehend.

La Liga wanted piracy stopped. What they've actually highlighted is that piracy is a market problem with market solutions, and court orders can't substitute for building a better, more attractive legal product.

The VPN companies, meanwhile, have drawn a line. They're saying: we'll comply with laws, but we won't break our security to do it. That's a defensible position. It's also one that regulators will be grappling with for the next decade.

Spain's court order was issued in October 2024. We're now in a waiting period. Will the companies be forced to comply? Will the order be enforced? Will there be a compromise? Will other countries follow suit?

The next chapter of this story will define how internet regulation works in Europe for years to come. And it all started with a question that sounds simple but is anything but: how do you block content accessed through a service specifically designed to prevent exactly that kind of blocking?

That question doesn't have a clean answer. And that's the real story here.

Key Takeaways

- Spain's court ordered NordVPN and Proton VPN to implement 'dynamic blocking' of illegal streaming sites, but neither company has been formally notified of the order

- VPN companies argue that dynamic blocking is technically impossible without compromising encryption and breaking their privacy model entirely

- Unlike ISPs that maintain user records, VPNs are designed specifically to prevent that capability, making traditional content blocking architecturally unfeasible

- The precedent could expand beyond piracy blocking if courts establish that they can order content blocking through VPN services in other EU countries

- La Liga's real piracy problem likely requires market-based solutions (lower costs, better streaming options) rather than technical blocking enforcement

Related Articles

- Grok's Deepfake Crisis: EU Data Privacy Probe Explained [2025]

- India's New Deepfake Rules: What Platforms Must Know [2026]

- EU Investigation into Shein's Addictive Design & Illegal Products [2025]

- Iran VPN Crisis: Millions Losing Access Due to Funding Collapse [2025]

- Seedance 2.0 and Hollywood's AI Reckoning [2025]

- India's Domain Registrar Takedowns: How Piracy Enforcement Changed [2025]

![La Liga VPN Block: What Spain's Court Order Means for Streaming [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/la-liga-vpn-block-what-spain-s-court-order-means-for-streami/image-1-1771351902350.jpg)