Laser-Tuned Magnets at Room Temperature: The Future of Storage & Chips [2025]

Last year, researchers pulled off something that seemed stuck in the realm of theoretical physics. They tuned magnetic behavior in materials thinner than human hair using nothing but visible light and room temperature conditions. According to TechRadar, this breakthrough could revolutionize data storage and processing technologies.

No cryogenic chambers. No infrared lasers costing six figures. Just lasers and ordinary conditions.

The implications hit different depending on who you ask. Data center operators see cheaper power bills. Storage engineers see faster hard drives. Chip designers see a path around silicon's thermal wall. Everyone, it turns out, benefits when you can control magnetism with precision.

TL; DR

- Visible light lasers now tune magnetic frequencies at room temperature, shifting them by up to 40% without extreme conditions, as detailed in Nature Communications.

- Nanometer-scale magnets (20nm thickness) enable dense, practical integration into existing electronics and future systems.

- Applications span hard drives, cloud storage, spin-based computers, and reconfigurable hardware that switches behavior on the fly.

- Heat efficiency gains could reduce data center power consumption and extend battery life in portable devices by significant margins.

- Real-world deployment timeline estimates 3-5 years for initial commercial applications in storage systems, according to S&P Global.

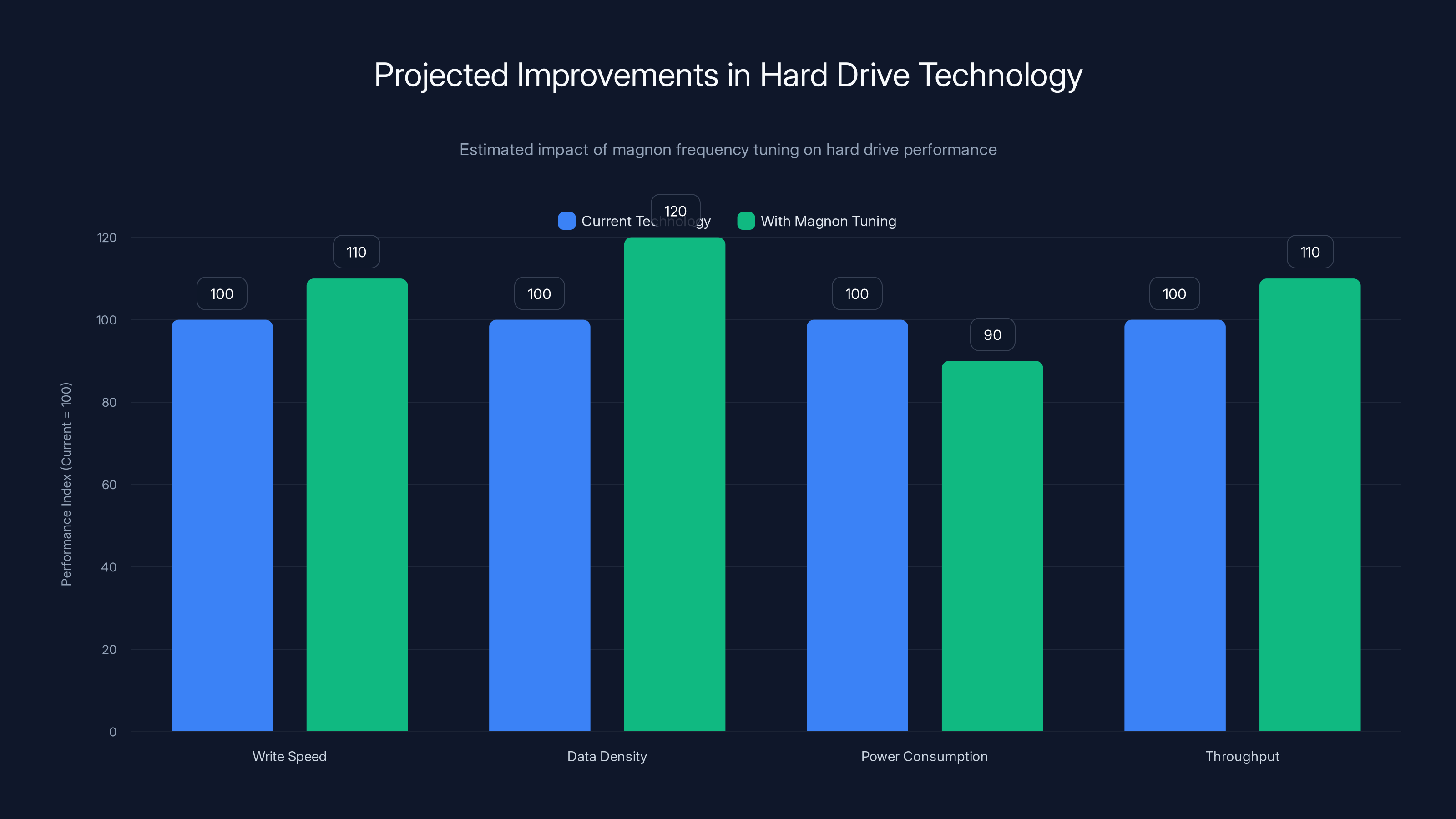

Magnon frequency tuning can potentially increase write speed by 10%, improve data density by 20%, reduce power consumption by 10%, and enhance throughput by 10%. Estimated data based on potential technological advancements.

What Are Magnons and Why Should You Care

Magnons sound like a fictional creature from a fantasy novel. In reality, they're something far more interesting and immediately practical.

A magnon is a collective spin excitation. Think of it as a wave of magnetism traveling through a material, where many electron spins act in concert rather than individually. If you've ever watched ripples on a pond, you have the mental picture. Instead of water moving up and down, electrons align and realign their magnetic moments in a coordinated pattern.

Why does this matter for your laptop or your cloud data? Because magnons are the actual mechanism that makes modern hard drives work.

When you write data to a hard drive platter, you're not directly manipulating individual electrons. You're creating magnetic fields that flip the alignment of domains on the disk surface. Those domains stay flipped until you change them again. That's how your files persist. Magnons are the carriers of that magnetic information, and their frequency determines how fast they can oscillate and respond to external influences.

The frequency of a magnon oscillation is crucial. Higher frequency means faster response. Faster response means you can store more information in the same space, read it quicker, and write it more reliably. For decades, controlling magnon frequency precisely has been the holy grail of magnetic device engineering.

The problem was always the same: the methods to control them were brutish and impractical.

Previous experiments required mid-infrared lasers that generated intense heat, forced researchers to cool materials to near absolute zero, or involved bulky materials incompatible with modern electronics. You can't exactly build a data center where every hard drive sits in a liquid nitrogen bath. The capital costs alone would be astronomical.

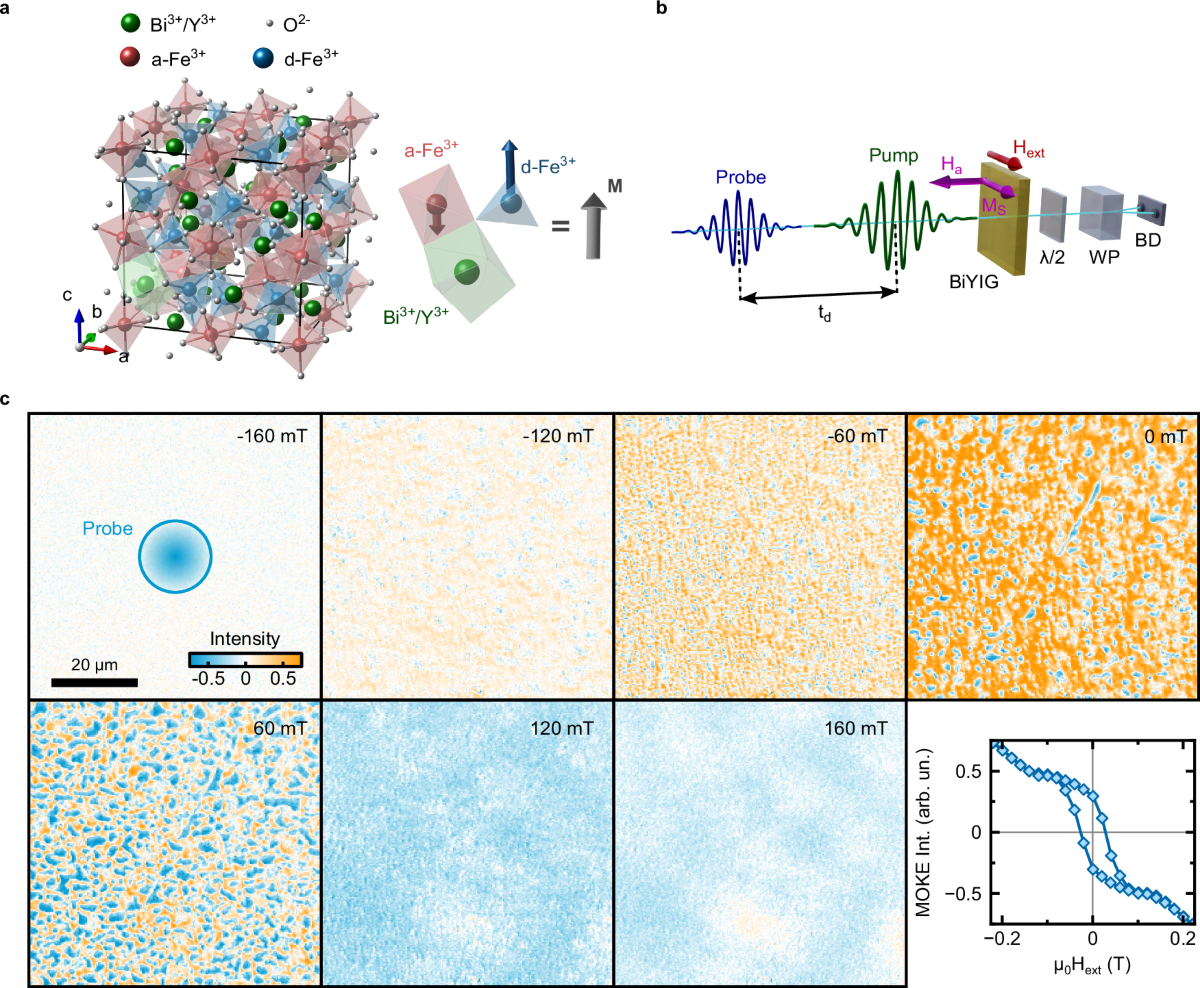

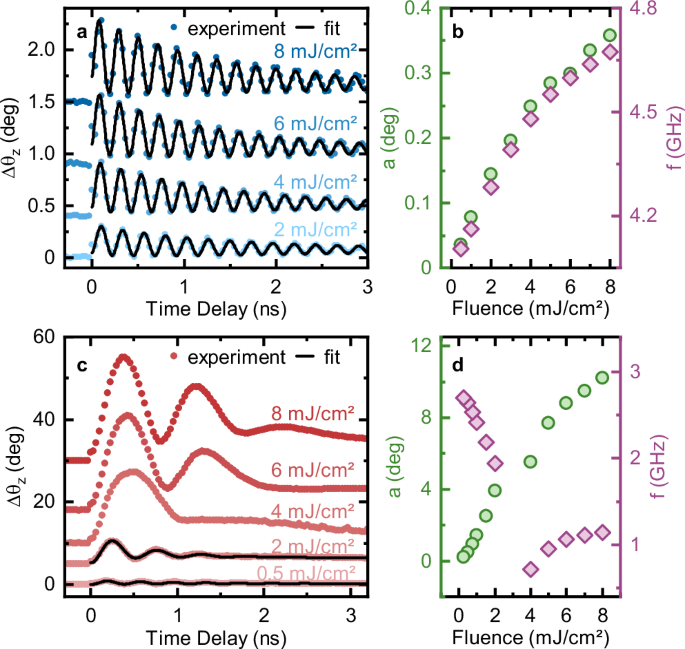

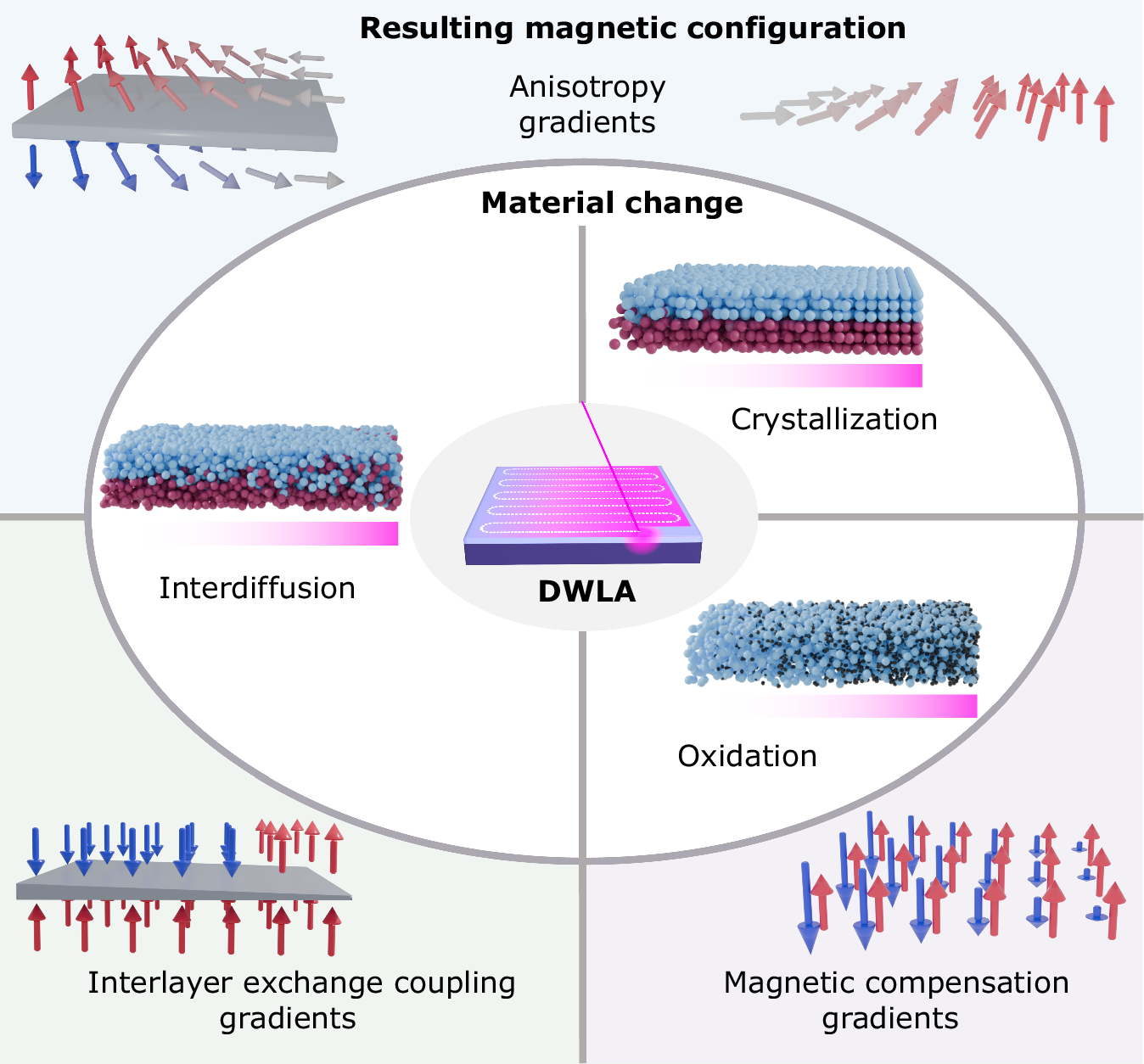

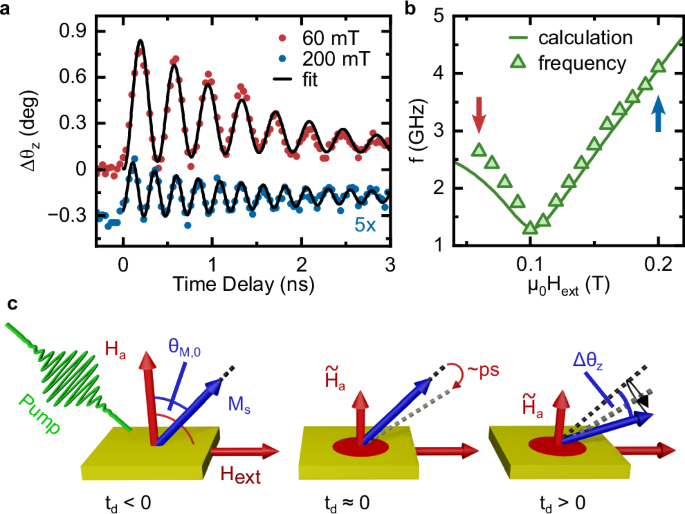

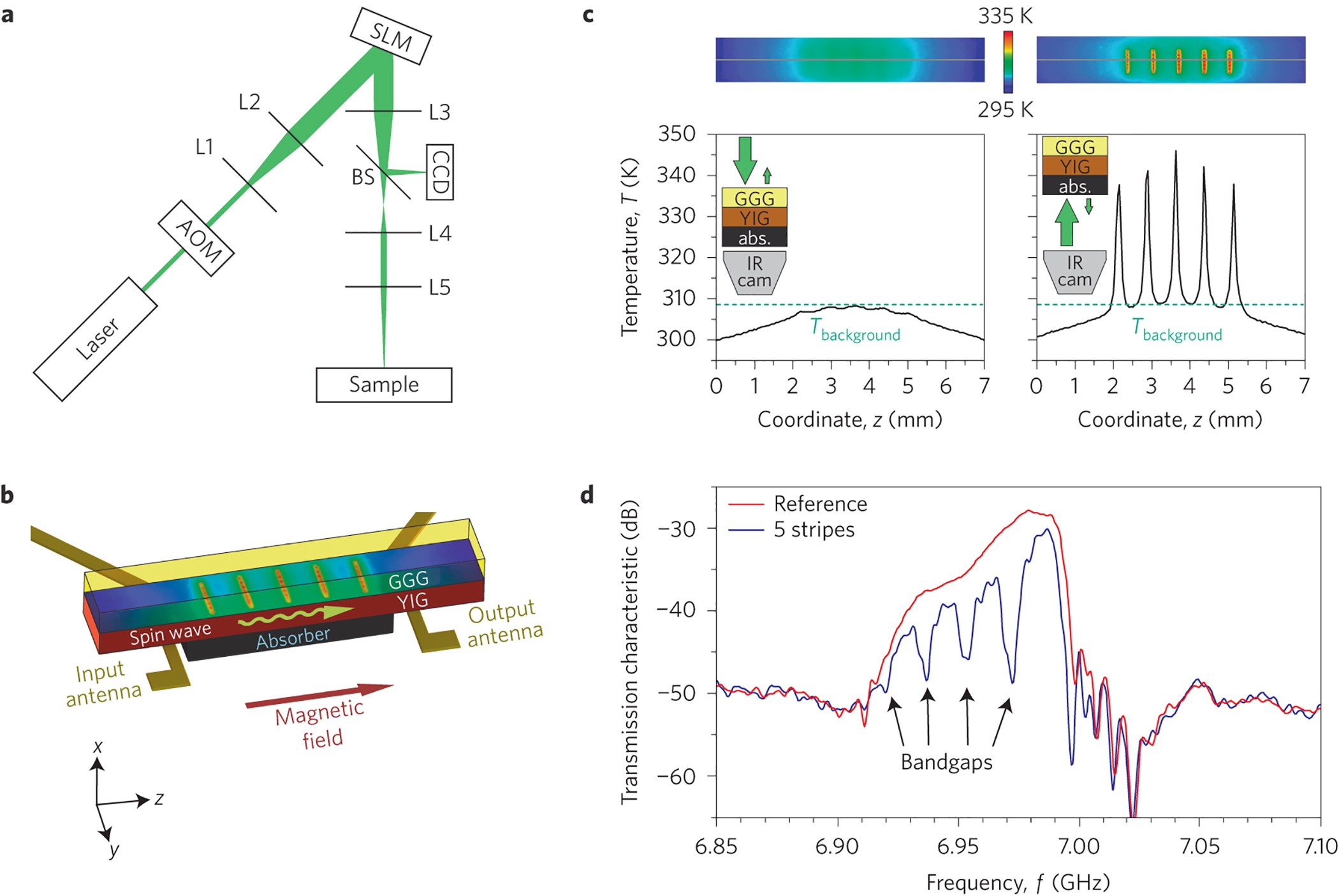

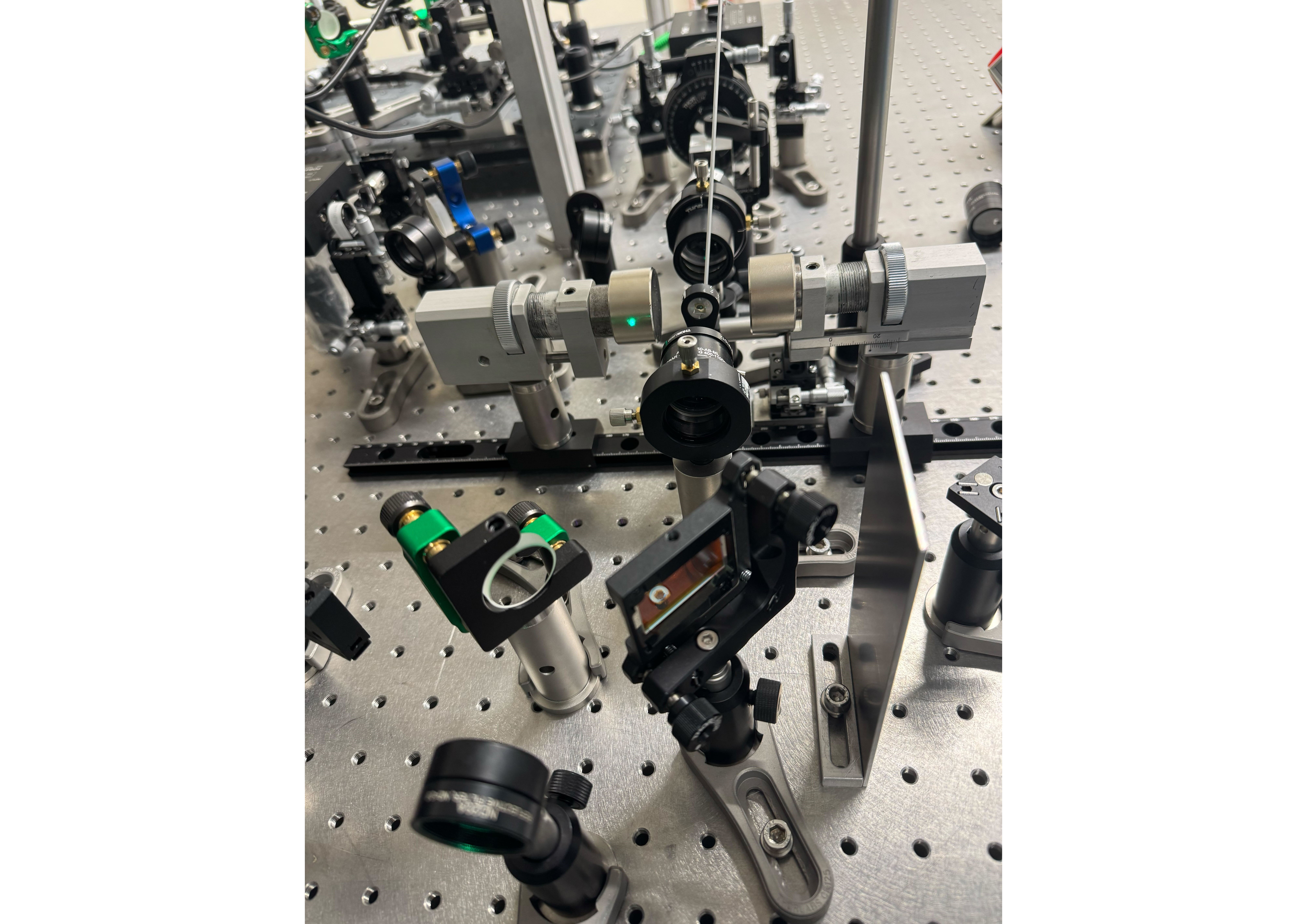

The breakthrough published in Nature Communications changes this entirely. The researchers demonstrated that visible light lasers at room temperature can do what previously required extreme conditions. The mechanism is elegant: short pulses of visible light temporarily alter the magnetic stiffness of the material, changing how fast the magnons can oscillate.

It's not a simple heating effect. The optical heating, magnetic anisotropy, and applied magnetic field interact in a precise way that allows researchers to tune frequency up or down by as much as 40 percent. That's a massive range of control. In practical terms, it means you can adjust the operating characteristics of a magnetic device almost instantly, on demand, using nothing more than adjusting laser intensity and field strength.

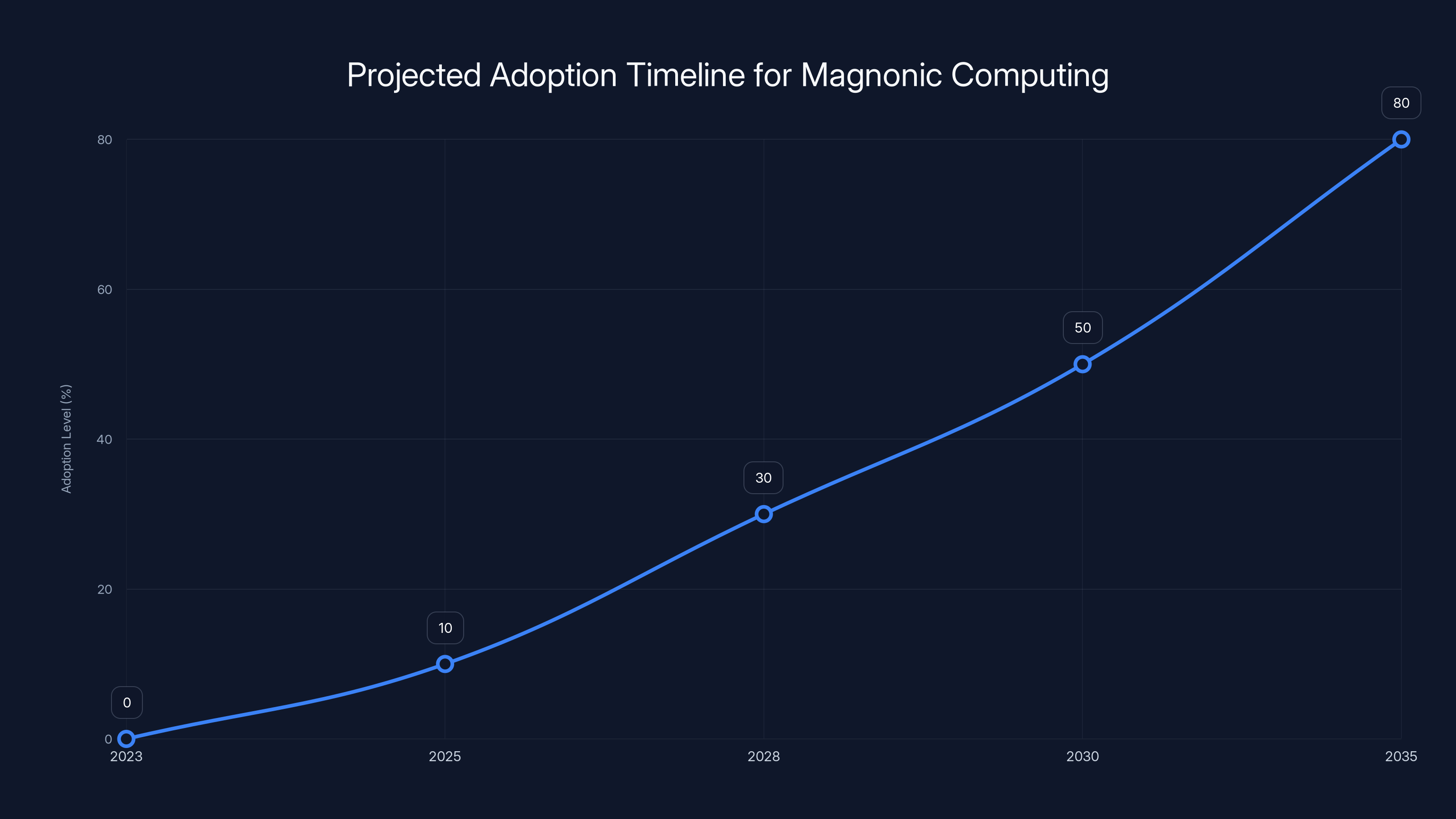

Magnonic computing is expected to gradually integrate into mainstream systems over the next 10-15 years, with significant adoption projected by 2035. Estimated data.

The Material Science Behind Room Temperature Control

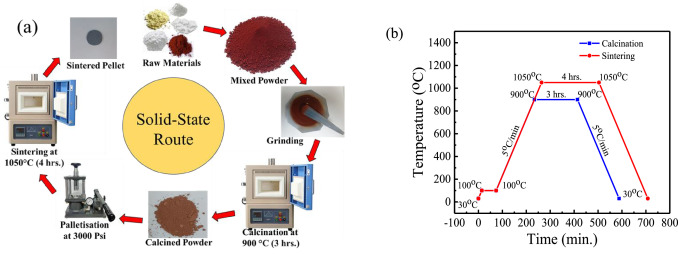

The specific material used in the experiments matters enormously. Researchers used a bismuth-substituted yttrium iron garnet film grown on a gadolinium scandium gallium garnet substrate. That's a mouthful, but each element serves a purpose.

Yttrium iron garnet, or YIG, is the industry standard for magnetic research. It's been used for decades because it has two critical properties: low damping and strong magneto-optical response. Low damping means the magnetic excitations persist longer without fading away. Strong magneto-optical response means the material interacts strongly with light, responding to optical pulses with measurable changes in magnetization.

The bismuth substitution is the clever bit. Adding bismuth modifies the material's magnetic properties in ways that enhance the magneto-optical effect. It's like tuning an engine by adjusting the fuel mixture. The substitution increases the magnetic anisotropy, which determines the energy landscape that magnons navigate.

The gadolinium scandium gallium garnet substrate provides a crystalline foundation compatible with the YIG film. Growth happens in layers measured in nanometers. The final film thickness of just 20 nanometers is critical. At that scale, the material is thin enough to integrate into nanoscale electronics, yet thick enough to maintain the magnetic properties that make the effect work.

Twenty nanometers is roughly 1/5000th the thickness of a human hair. It's invisible to the naked eye. Yet within those thin layers, complex magnetic phenomena can be precisely controlled.

The experiments used visible light lasers with short pulse durations, measured in femtoseconds. A femtosecond is a millionth of a billionth of a second. At these timescales, the laser pulse creates a sudden, localized temperature increase. This heating doesn't uniformly melt or damage the material. Instead, it modulates the magnetic anisotropy through the optical heating effect.

The external magnetic field applied during the experiment was modest, less than 200 millitesla. That's roughly the strength of a strong permanent magnet, not an electromagnet requiring significant power. The field provides a bias that determines which direction the magnon frequencies shift.

The combination of these elements creates a system where magnon frequency can be tuned reliably. The tuning is reversible. It happens on nanosecond timescales. And it requires no cryogenic equipment or exotic infrastructure.

From a materials science perspective, this is significant because it opens a new category of possibilities. Previous approaches relied on materials with specific fixed properties. If you wanted different magnon frequencies, you needed different materials. Now, with the same material, you can dynamically adjust the frequencies by changing laser intensity and field strength.

The damping characteristics of YIG are particularly important. High-damping materials absorb magnon energy quickly, causing the oscillations to fade. Low-damping materials let magnons persist longer, making them easier to manipulate and detect. YIG's low damping is legendary in the field, which is why it became the reference material for magnon research.

The magneto-optical response determines how strongly the material interacts with light. A strong response means even modest laser pulses can create measurable frequency shifts. A weak response requires intense lasers that might damage the material or require cooling to prevent damage.

How the Laser Tuning Process Actually Works

Understanding the mechanism takes us into the details of how light and magnetism interact. The process isn't mysterious once you understand the physics, but it's not intuitive either.

When the visible light laser pulse hits the material, it doesn't directly flip magnetic moments the way an applied magnetic field might. Instead, the light does something more subtle. It rapidly raises the local temperature in the illuminated region. This temperature change propagates through the material almost instantaneously compared to mechanical timescales.

Now here's where it gets interesting. The magnetic anisotropy of the material depends on temperature. As temperature increases, the anisotropy changes. This is a well-known effect in magnetism called thermal modulation of anisotropy. The laser exploits this effect by creating a controlled, temporary temperature pulse.

During the laser pulse duration, the magnetic stiffness of the material decreases. Magnetic stiffness directly determines magnon frequency. Stiffer materials have higher magnon frequencies, like a tighter guitar string producing higher notes. Reduce the stiffness temporarily, and the frequency drops. Remove the stiffness reduction, and the frequency returns to its original value.

The external magnetic field applied during the experiment serves as a bias. The field direction determines the magnetic state of the material. By orienting this field appropriately, researchers can ensure that the laser-induced frequency shift goes up or down as desired.

The mechanism operates on nanosecond timescales because that's how fast the laser-induced changes propagate through the thin material. In 20 nanometers of material, temperature equilibrates very quickly due to the small distances involved. The magnons respond to the changing stiffness landscape almost instantaneously.

What makes this approach fundamentally different from previous attempts is that it works without destroying the material or requiring extreme conditions. Mid-infrared lasers can generate enough heat to melt or damage sensitive materials. Cryogenic approaches require specialized equipment and continuous energy input. This method operates at room temperature in ordinary laboratory conditions.

The laser pulses are short enough that they don't cause cumulative damage. They don't generate runaway heating. They create a controlled perturbation that relaxes naturally within nanoseconds.

Reversibility is crucial for practical applications. The researchers demonstrated that magnon frequencies could be shifted up or down depending on parameters. Shift up, wait for the material to relax, shift down. The material shows no signs of fatigue or degradation even after thousands of cycles.

The interaction between optical heating, magnetic anisotropy, and the applied field creates a complex parameter space. The research team systematically explored this space, demonstrating that by varying laser intensity and field strength, they could reliably produce desired frequency shifts. This predictability is essential for moving from proof-of-concept to practical devices.

In essence, the visible light laser creates a temporary handle on the material's magnetic properties. Grab that handle, shift the frequency where you need it, release it, and the material returns to rest. All in nanoseconds. All without cryogenics or exotic infrastructure.

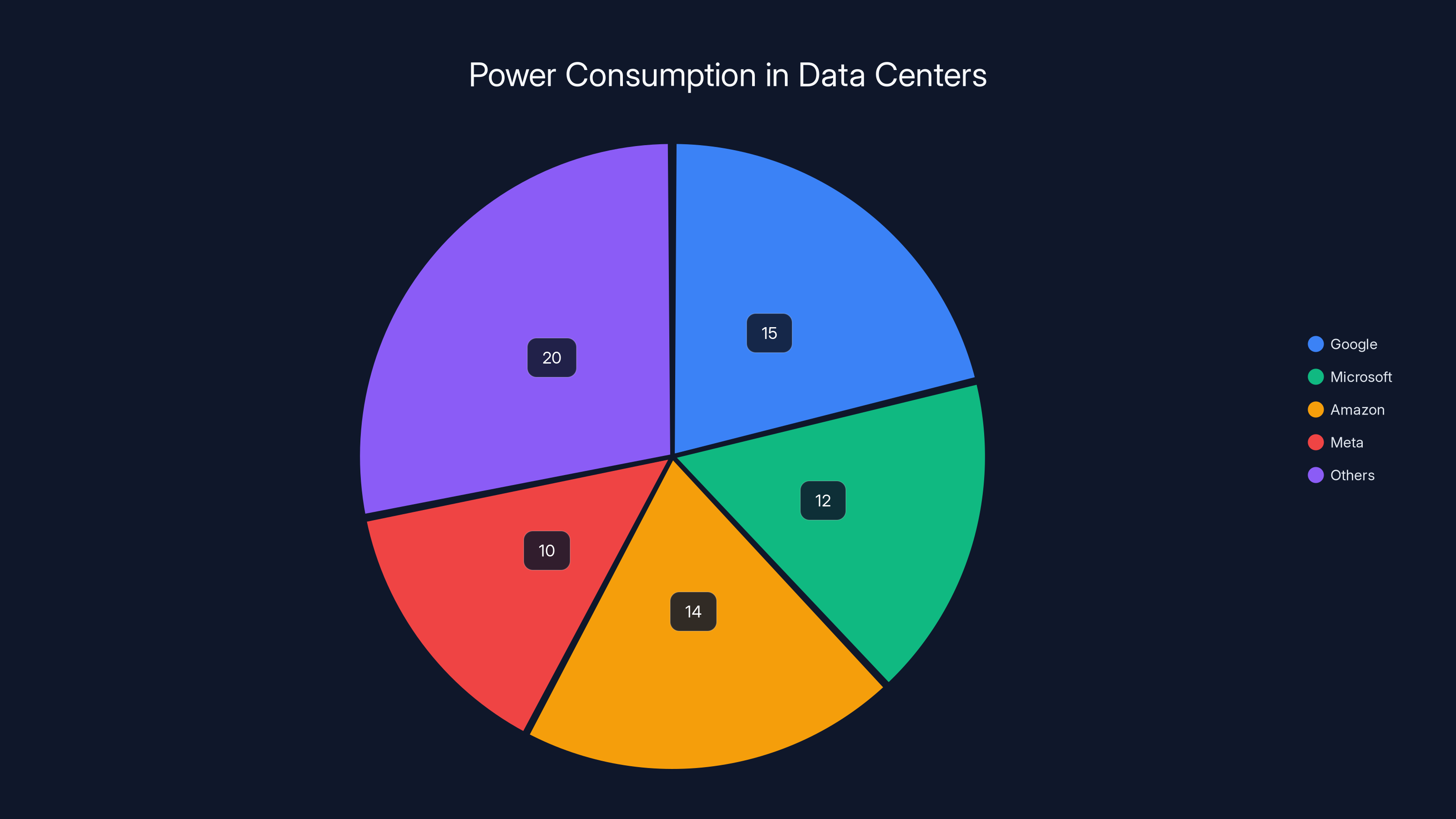

Estimated data shows Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Meta as major power consumers, collectively using over 50 terawatt-hours annually. 'Others' includes smaller hyperscalers and additional facilities.

Implications for Hard Drives and Data Storage

The most immediate application is hard drive technology. Current hard drives use magnetic recording on spinning platters. The magnetic domains on the platter surface encode bits of information. Reading and writing those bits requires magnetic fields generated by tiny electromagnets positioned above the platter surface.

Speed limitations exist at multiple levels. The actuator arm that positions the read/write head takes time to move. The spin-up time for the platter takes time. The time required to reliably write magnetic transitions takes time. The magnon frequency tuning breakthrough addresses that last factor.

When you write data to a hard drive, you apply a magnetic field to flip the alignment of domains. The time this takes depends on how fast the magnons can respond. If you can increase magnon frequency using light pulses, you can write data faster. If you can decrease magnon frequency, you can improve reliability in marginal conditions. Suddenly, a single drive design can operate in multiple modes by adjusting laser conditions.

Density improvements are significant. Current hard drives hit density limits partly because of how close together you can write magnetic transitions without interfering with each other. Magnons spreading out magnetic energy are one source of that interference. With better magnon control, you can pack transitions closer together while maintaining reliability.

Consider a practical scenario. A modern data center might have hundreds of thousands of hard drives. Even modest speed improvements translate to enormous throughput gains. A 10% speed increase across all drives means 10% more data moved in the same time. That compounds across a year into massive capacity gains without adding new drives.

Speed isn't the only benefit. Power consumption decreases when you require fewer electromagnetic pulses to write data, fewer head actuations to find data, and faster spinning to reduce latency. In a data center context, power consumption directly translates to operational costs. Reduction in power means reduction in cooling requirements, which further reduces power. The compound effect is substantial.

The nanometer-scale thickness of the magnetic material is actually advantageous for storage applications. It means the technology integrates well with existing semiconductor manufacturing processes. Hard drive heads are already manufactured at nanometer scales using similar lithography techniques. Adding a thin magnonic control layer to existing heads requires only incremental changes to manufacturing processes, not complete redesigns.

Reliability improvements emerge from better control. Current hard drives operate with fixed magnetic properties. They're designed to work reliably across a range of conditions, but there's no adaptation. With magnon frequency tuning, you can adjust operating characteristics based on real-time conditions. Detecting that a bit is marginal? Increase magnon frequency for better response. Detecting that thermal noise is high? Shift frequency to a safer operating point. This adaptive operation increases reliability and reduces errors.

The timeline for hard drive application is probably 2-4 years. The technology needs to transition from laboratory demonstrations to prototype read/write heads, then to small batch testing, then to manufacturing scale-up. Hard drive manufacturers will want to understand reliability over millions of cycles, performance across temperature ranges, and compatibility with existing drive designs.

The Spin-Based Computing Revolution

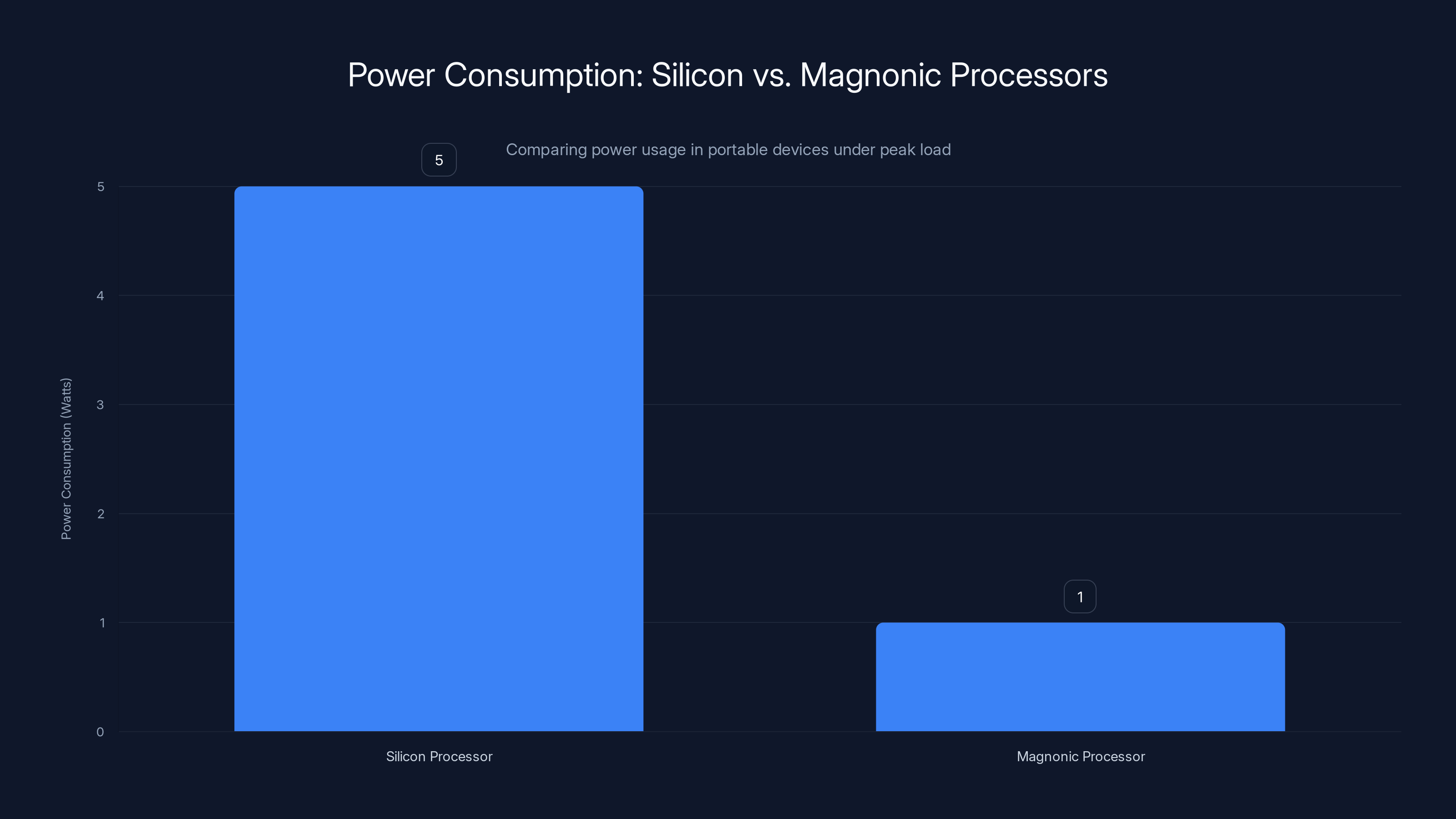

Beyond storage, the breakthrough opens possibilities for entirely new computing paradigms. Silicon-based processors face a fundamental physics problem: they generate heat. As you pack more transistors into smaller spaces, heat density increases. Extracting that heat requires increasingly sophisticated cooling. At some point, the cooling infrastructure costs as much as the computing hardware itself.

Magnetic computing offers a potential escape route. Instead of encoding information in electrical charges moving through transistors, you encode it in magnetic states. The beauty of magnetic computing is that magnetic states consume no power to maintain. A bit stored as magnetic orientation stays that way indefinitely without energy input.

Spin-based computing exploits this property. Information is encoded in the spin orientation of electrons. Manipulation happens through magnetic fields or spin currents. The power consumption is orders of magnitude lower than equivalent silicon circuits because you're not pushing electrical currents through resistances that generate heat.

The magnon tuning breakthrough enables new types of spin logic elements. Previously, spin devices had fixed operating characteristics. Now, using light pulses, you can dynamically reconfigure how they respond. A logic gate that performs operation A could be reconfigured to perform operation B by changing laser parameters.

This adaptability is revolutionary. Traditional chips have fixed logic. You design them, manufacture them, and they do what they do. You can't change their behavior. Magnonic chips could change behavior dynamically. The same hardware could run different algorithms by adjusting light intensity and frequency.

Consider a neural network accelerator. Different neural network architectures require different hardware optimizations. Traditionally, you design a chip for one architecture, manufacture millions, and hope it matches your needs. With magnonic reconfigurable logic, you manufacture a generic magnonic chip and adjust its behavior to match whatever neural network you're running. One chip, multiple use cases.

The power efficiency gains are massive. Silicon-based AI accelerators consume kilowatts of power. The cooling systems for data centers handling AI workloads consume almost as much power as the chips themselves. Magnonic systems could reduce that by orders of magnitude.

The thermal advantages extend to wearable devices and portable electronics. Your smartphone could have a vastly more powerful processor that generates barely any heat. Instead of your phone getting warm during intensive tasks, it stays cool even while running heavy computation. That means longer battery life, better performance, and fewer thermal throttling issues.

The timeline for practical magnonic processors is longer than storage applications, probably 5-10 years. The technology requires development of magnonic logic gates, demonstrations of reliable computing, error correction mechanisms, and manufacturability solutions. These are non-trivial challenges, but each is being actively researched.

One significant advantage is that magnonic circuits could interface with existing silicon. A hybrid approach where magnonic accelerators handle compute-intensive tasks while silicon handles control logic might emerge first. This hybrid approach requires less revolutionary change than replacing silicon entirely.

Magnonic processors consume significantly less power than silicon processors, allowing for extended battery life in portable devices. Estimated data based on typical usage scenarios.

Reconfigurable Hardware: The Same Chip, Different Behaviors

Hardware reconfigurability might be the most immediately disruptive application. Every piece of electronics contains chips designed for specific tasks. A USB controller does one thing. An audio codec does another. A video encoder does something else. Specialized chips require different silicon, different manufacturing, different inventory.

Imagine a single magnonic chip that could reconfigure itself to handle any of those tasks. You design it once, manufacture it once, and deploy it everywhere. When you need it to function as a USB controller, you adjust its light-based programming. When you need it as an audio codec, you adjust it again.

This isn't science fiction. The underlying principle works. The magnon frequency control demonstrated in the research is essentially a programmable parameter that affects how the device responds to inputs. Multiple such parameters, controlled by different light pulses at different wavelengths, could create a fully programmable magnetic logic device.

The advantages cascade through entire supply chains. Chip manufacturers focus on one platform. System designers have flexibility. Customers get more efficient inventory management. As product requirements change, you reprogram hardware instead of redesigning it.

The cost implications are staggering. Bringing a new chip design to market costs hundreds of millions of dollars. Reconfigurable chips amortize that cost across multiple applications. A chip that costs

There are challenges. Programming magnonic logic requires understanding how to encode algorithms in magnetic operations. You can't just translate silicon code directly. New programming paradigms, new compilers, new optimization techniques all need development.

Physical integration is another challenge. You need visible light sources integrated with the magnetic computing elements. That means miniaturized lasers or LED elements coupled with waveguides directing light to the right places. Current semiconductor manufacturing handles this in some contexts, but generalizing it across a full computing platform is non-trivial.

Reliability validation is crucial. Silicon chips have proven reliability over decades. Magnonic systems need similar confidence. That requires extensive testing, redundancy mechanisms, and error correction. The research is promising, but production-grade reliability requires more work.

The most likely near-term deployment path is in specialized domains where reconfigurability provides exceptional value. Scientific instruments, research equipment, specialized computing platforms, and military applications often need algorithmic flexibility. These markets tolerate higher costs and longer development timelines. Success in these niches creates knowledge, builds supply chains, and demonstrates feasibility to broader markets.

Data Center Economics and Power Consumption

Data centers are massive power consumers. A typical hyperscaler facility consumes enough electricity to power a small city. Google alone consumes over 15 terawatt-hours of electricity annually, mostly for data centers. Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and other hyperscalers have similarly enormous power footprints.

The economic incentive to reduce power consumption is almost incomprehensible in magnitude. A 1% reduction in power consumption across all data centers globally would save hundreds of millions of dollars annually. A 10% reduction would save billions.

Magnon frequency tuning contributes to this efficiency in multiple ways. Faster storage devices move data more efficiently, reducing the time processors spend waiting. Spin-based computing replaces silicon in compute-intensive workloads, eliminating heat generation entirely. Reconfigurable hardware reduces the number of different chip types required, improving manufacturing efficiency.

Consider the cumulative effect. A data center using magnon-tuned storage sees 5-10% speed improvements. The same data center using magnon-based AI accelerators instead of silicon sees 50%+ power reduction for compute workloads. Reconfigurable chips eliminate the need to manufacture 20 different special-purpose chips, each optimized for one task.

The compound effect is that next-generation data centers could consume half the power of current facilities while delivering twice the performance. The difference between "half the power" and "half the power consumption" is that the former describes a design goal; the latter describes an economic constraint.

Power costs represent 30-50% of data center operating expenses. Reducing power consumption directly impacts profitability. This creates intense competitive pressure to adopt new technologies that improve efficiency.

Cooling infrastructure represents another major cost component. Data centers require sophisticated climate control systems to remove the heat generated by computing equipment. Reducing heat generation has a double effect: lower cooling requirements and lower power for cooling. Some estimates suggest that for every watt of computing, cooling infrastructure consumes 0.5 to 1.5 additional watts depending on efficiency.

Magnetic computing reduces heat generation, which reduces cooling power, which reduces the power penalty for cooling. The compound savings exceed the direct power reduction from the computing elements themselves.

The timeline for significant data center impact is probably 5-7 years. Hyperscalers will pilot magnonic storage and computing elements starting in 2-3 years, validate reliability and performance, then begin broader deployment. Given the economics involved, once technology achieves production quality, adoption will be rapid.

Smaller data centers and enterprise facilities will follow, though the cost-benefit analysis differs. A small facility might not justify custom infrastructure investment. Standardized solutions emerging from hyperscaler pioneers will gradually trickle down.

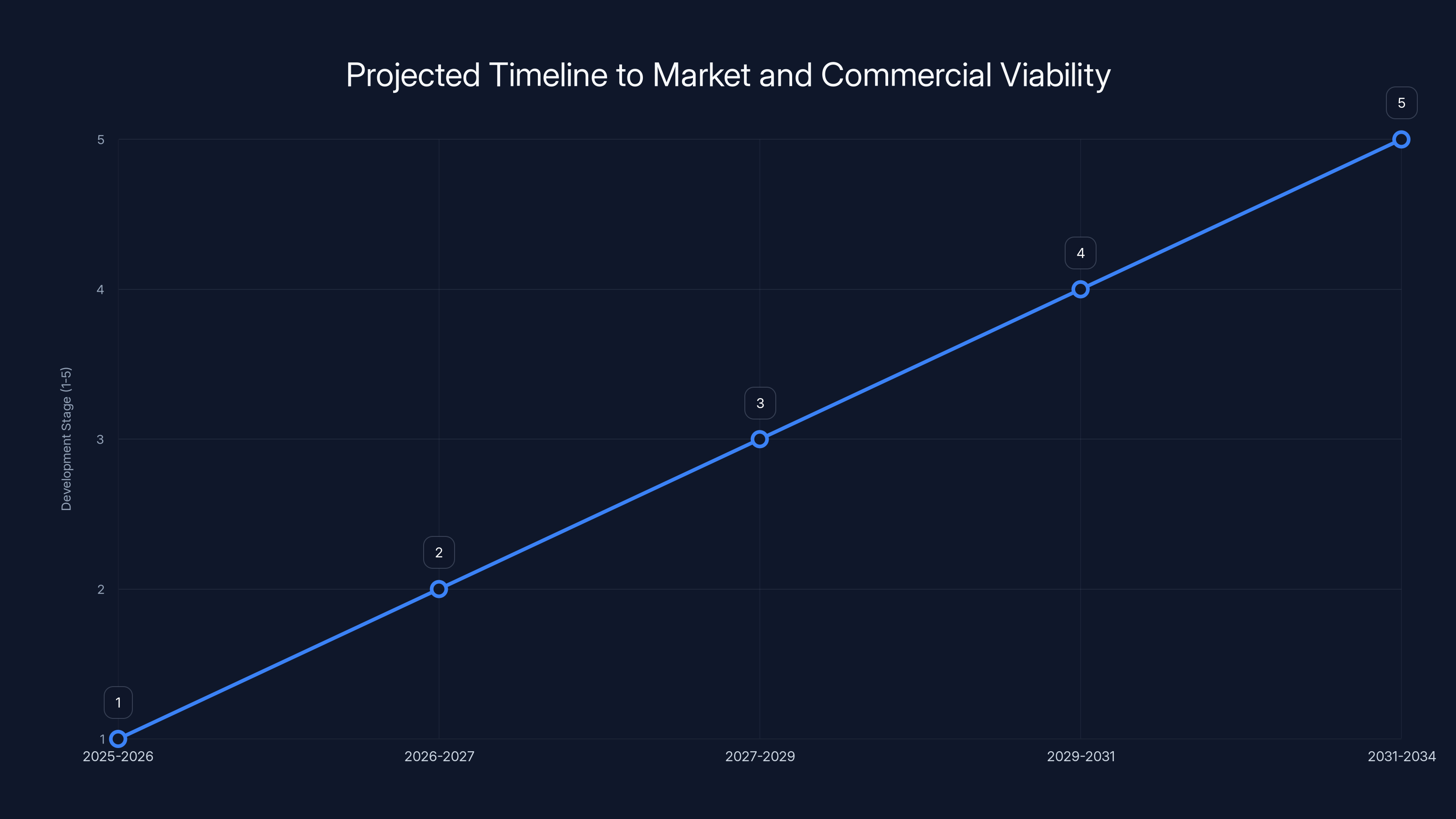

The timeline shows a gradual progression from research and prototyping (2025-2026) to mainstream adoption and cost competitiveness (2031-2034). Estimated data.

Integrating Magnonic Technology into Semiconductor Manufacturing

Moving magnonic technology from research labs to manufacturing lines requires solving problems that silicon solved decades ago. Manufacturing infrastructure, quality control, design tools, and supply chains all need development.

The good news is that magnonic materials integrate well with existing semiconductor manufacturing. Yttrium iron garnet films can be grown using techniques compatible with current fabrication facilities. The 20-nanometer scale thickness matches the precision of modern lithography tools.

What's new is the optical infrastructure. Current semiconductor fabs don't include networks of visible light lasers and waveguides distributed across chips. Adding this requires new equipment, new expertise, and new process steps.

Fortunately, optical integration is an active area of semiconductor development. Integrated photonics, the field that combines light generation, manipulation, and detection on chips, has been advancing rapidly. Technologies developed for optical communications can potentially be adapted for magnonic control.

The required laser wavelengths are in the visible to near-infrared range, probably 400-1000 nanometers. Semiconductor lasers and LEDs covering this range are manufactured at scale for consumer electronics. Integrating these into computing platforms isn't fundamentally new; it's more a matter of customization and optimization.

Heat management becomes critical when you're integrating lasers with computing elements. Lasers generate waste heat just like transistors. Integrating them requires careful thermal engineering to prevent the cooling advantage of magnetic computing from being negated by laser inefficiency.

Probably the efficiency gains require using femtosecond lasers with high repetition rates rather than continuous illumination. This allows precise control of magnon frequencies while minimizing average power consumption. Femtosecond laser technology has matured significantly and is commercially available.

Quality control and testing will require new metrology tools. Currently, chip testers measure electrical parameters. Magnonic devices require techniques to verify magnetic properties, magnon frequencies, and optical response. Developing standardized tests and tools is necessary before volume manufacturing.

The supply chain for YIG and other magnonic materials needs scaling. Research labs obtain these in small quantities. Manufacturing at scale requires different sourcing, quality control, and cost structures. This typically takes 2-3 years after technology decisions are made.

Once manufacturing infrastructure is established, costs will follow the usual semiconductor learning curves. Initial costs are high, but as volume increases and processes mature, costs decline exponentially. History suggests that magnonic materials could reach cost parity with silicon for equivalent functionality within 5-10 years of volume production start.

Wearable and Portable Device Applications

Beyond data centers and servers, magnonic technology impacts consumer devices. Your smartphone, smartwatch, wireless earbuds, and laptop all would benefit from improved storage and more efficient processors.

Battery life is the ultimate constraint for portable devices. Bigger batteries add weight and size. More efficient computing extends battery life without those drawbacks. Magnonic processors consuming a fraction of silicon's power would be transformative for portable electronics.

Consider a scenario. Your smartphone currently runs a silicon processor that consumes 5 watts during peak load. A magnonic equivalent might consume 1 watt. Your phone's battery has 15 watt-hours of capacity. The silicon processor can run at peak load for 3 hours before battery depletion. The magnonic processor runs for 15 hours.

That's not a hypothetical advantage. That's a real shift in what's possible with portable devices. You could have a phone that lasts days instead of hours, even with heavy usage.

Thermal benefits matter for portable devices. Your phone doesn't have a fan or any active cooling. Heat generation is limited by passive dissipation. Modern flagship phones already throttle performance when they get too hot. Magnonic processors that barely generate heat would allow sustained peak performance indefinitely.

This opens possibilities for applications currently not feasible in portable form factors. Real-time video processing, advanced computational photography, local AI inference, scientific instrumentation, medical monitoring, all become feasible when power and thermal constraints relax.

The magnonic storage aspect matters for portable devices too. Faster storage in smaller form factors means more data in less space. Improved speed means quicker access, which translates to snappier applications. The user experience improvement from faster storage is significant, though less dramatic than processor improvements.

Wearable medical devices represent a particularly promising application. Current smartwatch health sensors are limited by power and thermal constraints. More sophisticated sensors and processing could be integrated if power consumption dropped significantly. Continuous, local processing of health data could detect anomalies and alert users or physicians in real-time.

Aircraft and aerospace applications could benefit significantly. Weight and power are critical constraints in aircraft design. Reducing processor power consumption reduces cooling requirements, which reduces weight, which reduces fuel consumption. For long-range aircraft, even 1% efficiency improvements cascade into significant fuel savings and operational cost reductions.

The timeline for consumer device adoption is probably 4-6 years after initial commercial availability. Device manufacturers will want proven technology, established supply chains, and demonstrated reliability before integrating magnonic components into consumer products. They also need to develop manufacturing processes and supply chain partnerships.

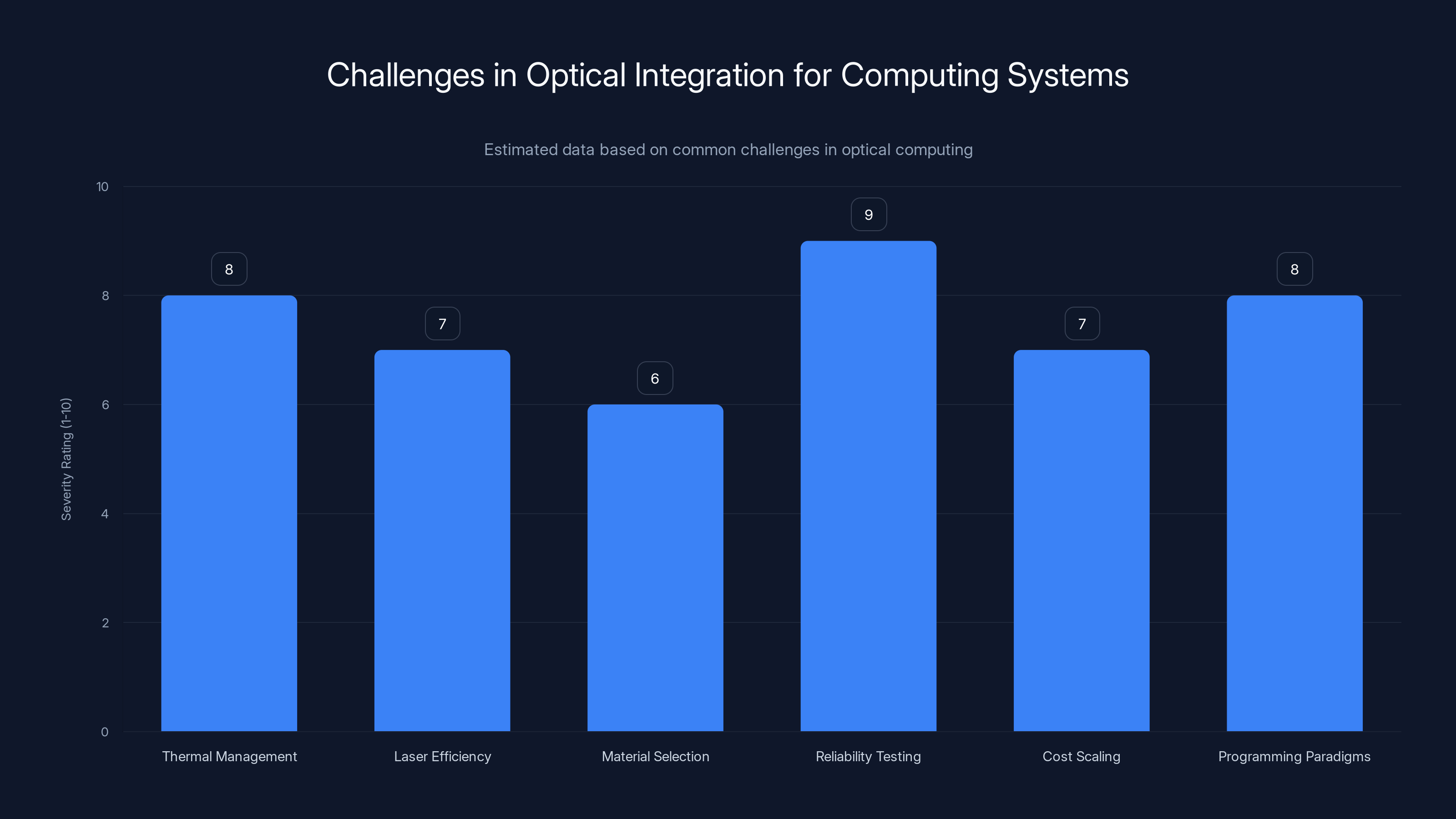

Thermal management and reliability testing are the most severe challenges in scaling optical integration to production systems. Estimated data based on typical industry challenges.

Biomedical and Healthcare Implications

The fact that magnonic materials work at nanometer scales at room temperature with visible light opens unexpected opportunities in biomedical applications. The original source mentions potential use even in the human body. That deserves serious consideration.

Current medical implants are limited by biocompatibility, power consumption, and heat generation. A pacemaker requires battery replacement surgeries every 5-10 years. Increasingly sophisticated implants could monitor more health parameters if power consumption wasn't a constraint.

Magnonic computing could enable implantable devices that operate without batteries through energy harvesting or wireless power transfer. The low heat generation means they won't cause tissue damage. The compatibility with existing biological environments, demonstrated by YIG's use in research with living systems, suggests safety is manageable.

Neural interfaces represent the frontier. Implantable electrodes that record from or stimulate neurons currently generate substantial heat. That heat damages neural tissue over time. Magnonic interfaces could perform equivalent signal processing with minimal heat.

Diagnostic applications are more immediate. Miniaturized sensors using magnonic principles could detect biomarkers, pathogens, or anomalies in blood or other body fluids. The sensitivity and specificity of magnonic detection methods show promise in laboratory research.

The regulatory pathway for biomedical applications is longer and more complex than for data centers or consumer electronics. Biocompatibility testing, long-term safety validation, and regulatory approval all take time. Probably biomedical applications emerge 7-10 years after the technology reaches production maturity in other domains.

Challenges and Practical Limitations

It's important to acknowledge that moving from laboratory demonstrations to production systems faces real obstacles. The research paper shows the principle works. Scaling to production is different.

Optical integration in computing systems is non-trivial. You need light sources, waveguides, optical modulators, and detectors all fabricated together at nanometer scales. Optical components have different thermal characteristics than electronic components. Integration requires careful engineering to prevent thermal issues that would negated the power efficiency gains.

Laser efficiency matters. If you need to generate optical pulses to control magnonic devices, the laser itself consumes power. You want lasers efficient enough that the power for optical generation is small compared to the power savings from magnonic computing. Current visible light lasers have room for efficiency improvement, but they're not free.

Material challenges exist. YIG is well-characterized and reliable, but it's not the only magnonic material being explored. Other options might offer better efficiency, easier integration, or lower cost. The field needs to settle on materials suitable for mass production.

Reliability validation requires extensive testing. Magnonic devices need to demonstrate comparable lifetimes to silicon devices—billions of transistors operating for years without failure. Early results are promising, but confidence only comes from extensive testing and deployment.

Cost scaling is uncertain. Magnonic devices require specialized materials and processing. Initial costs will be high. Whether manufacturing learning curves drive costs down to competitive levels with silicon is not yet certain. Confident cost projections require more production data.

Programming paradigms need development. Writing software for magnonic computers is different from conventional programming. You need new languages, compilers, and optimization tools. This is solvable but represents genuine development work.

Market inertia is real. Silicon has 70 years of development, standardization, and expertise behind it. Magnonic technology faces skepticism and resistance even when superior in principle. Overcoming that inertia requires multiple successful deployments demonstrating clear advantages.

Timeline to Market and Commercial Viability

Based on the maturity of the research and typical development timelines, here's a realistic projection:

Years 1-2 (2025-2026): Research groups expand the work, publishing results exploring different materials, parameter ranges, and applications. Prototype demonstrations at conferences and in specialized publications. Initial interest from companies in storage and computing industries.

Years 2-3 (2026-2027): First prototype devices incorporating magnonic frequency tuning in controlled environments. Small batch manufacturing trials. Reliability testing begins. Hyperscaler data centers run pilot projects. Early investment rounds in magnonic computing startups.

Years 3-5 (2027-2029): Production-ready devices for niche applications, probably first in data storage or specialized computing. Manufacturing scale-up begins. Design tools and programming frameworks mature. Second generation devices addressing initial limitations.

Years 5-7 (2029-2031): Broader adoption in data center and enterprise computing. Consumer device integration begins. Some success stories published showing power and performance benefits. Standardization bodies establish guidelines.

Years 7-10 (2031-2034): Mainstream adoption in new products. Legacy products gradually incorporate magnonic components. Biomedical applications emerge. Supply chains mature, costs decline toward competitive levels with silicon.

This timeline assumes no major technical breakthroughs or setbacks. Accelerating factors could compress the timeline: significant additional funding, successful pilot deployments demonstrating clear economic advantage, or technical innovations that simplify manufacturing.

Delaying factors could extend the timeline: manufacturing challenges not anticipated, reliability issues requiring deeper investigation, cost scaling not meeting projections, or competitive alternatives emerging that address the same problems.

The Bigger Picture: Computing's Next Paradigm

The magnon frequency tuning research represents more than an incremental improvement to existing technology. It's a signal of a deeper shift in how computing hardware will work in the future.

Silicon-based computing has fundamental physical limits. Heat generation, current leakage, and quantum effects at smaller scales all impose hard constraints. Moore's Law, the observation that transistor count doubles every two years, has been slowing for over a decade. The physics of making transistors smaller gets harder and more expensive each generation.

Magnonic computing sidesteps many of those constraints. Magnetic states don't leak or require power to maintain. Heat generation can be minimal if implemented carefully. The physics doesn't impose the same scaling penalties that silicon faces.

But magnonic computing isn't the only post-silicon approach being pursued. Quantum computers, optical computers, neuromorphic processors, DNA computing, and molecular computing all have research programs exploring their potential.

The magnon approach has advantages in the near and medium term. It's more compatible with existing semiconductor infrastructure than quantum computers. It's more power-efficient than optical approaches. It's more scalable than molecular approaches. That positioning makes it a likely candidate for near-term commercial viability even if other approaches eventually prove superior.

The research landscape is moving toward heterogeneous computing, where different processor types handle different workloads. Silicon for control logic, magnonic for compute-intensive tasks, specialized accelerators for specific operations. Future systems will be collections of optimized processing elements working together.

This shift opens opportunities for innovation and entrepreneurship. Companies starting now to develop magnonic technologies position themselves at the forefront of this transition. The winners will be those who solve manufacturing and cost challenges, establish ecosystem partnerships, and demonstrate clear advantages in real applications.

Preparing for Magnonic Computing's Arrival

Whether you're in hardware engineering, software development, systems design, or operations, understanding magnonic computing technology now is smart preparation for career longevity.

If you're in hardware engineering, learning about magnetic materials, magnon physics, and optical integration expands your skill set in directions that will be valuable. Many semiconductor companies are already exploring magnonic concepts.

If you're in software development, understanding how to program magnonic devices differs from conventional programming. Early learners will be in high demand as the field ramps up.

If you're in systems design or architecture, understanding the implications of computers with dramatically lower power consumption and different performance characteristics helps you design systems that exploit these advantages.

If you're in operations managing data centers, understanding emerging technologies like magnonic storage and computing helps you make long-term infrastructure planning decisions.

The knowledge investment required is modest right now. Read the research papers. Follow announcements from companies and research institutions working on magnonic technology. Understand the fundamentals of magnetism and optics. That foundation positions you well for the transition that's coming.

FAQ

What exactly is a magnon and how does it differ from a magnet?

A magnon is a collective spin excitation, essentially a wave of coordinated magnetic moments traveling through a material. It's different from a permanent magnet or magnetic field. While magnets are static magnetic properties, magnons are dynamic oscillations of those magnetic properties. Think of a magnon as a ripple on the surface of magnetism, whereas a magnet is the calm water itself. Magnons are the actual mechanism that enables fast magnetic switching in modern hard drives and other magnetic devices.

Why is room temperature operation so important for this technology?

Previous magnon manipulation techniques required either cryogenic cooling (near absolute zero temperatures) or powerful infrared lasers that generated intense heat and required special equipment. Room temperature operation means no specialized cooling infrastructure, no extreme environments, and compatibility with normal laboratory and commercial settings. This dramatically reduces the cost and complexity of systems using magnonic technology, making it feasible for practical applications in data centers, consumer devices, and portable equipment. The fact that it works at room temperature turns it from an interesting laboratory curiosity into a potentially transformative technology.

How close is magnonic computing to actually replacing silicon processors?

Magnonic computing won't completely replace silicon in the near term, perhaps ever. Instead, expect heterogeneous systems where different technologies handle different tasks. Silicon remains superior for control logic and low-power standby modes. Magnonic processors excel at compute-intensive workloads where they consume far less power. Hybrid systems combining both technologies are the most likely path forward. The transition timeline is probably 5-10 years before magnonic components appear in mainstream systems, and 10-15 years before they become a standard feature in most computing platforms. Replacement is more accurate as displacement in specific roles rather than complete substitution.

What materials besides YIG could be used for magnonic devices?

Yttrium iron garnet is the current standard because it has excellent properties for research and development, but it's not the only option. Researchers are exploring iron-based compounds, cobalt systems, and other magnetic materials. Some materials might offer better efficiency, easier integration, lower cost, or compatibility with different manufacturing processes. The field hasn't settled on a single optimal material. As technology matures, probably multiple material systems will coexist, each optimized for different applications. Early commercial products might use YIG or iron-based alternatives, with other materials emerging as technology develops.

Will magnonic devices work in portable electronics like phones and laptops?

Yes, the technology is particularly well-suited to portable electronics. Lower power consumption means longer battery life and reduced heat generation. Portable devices are severely constrained by battery capacity and thermal management. Magnonic processors could operate continuously without throttling due to overheating. The nanometer-scale thickness of magnonic materials allows integration into thin devices. However, widespread adoption in consumer electronics is probably 4-6 years away, requiring proven reliability, established supply chains, and integration into manufacturing processes. Early adopters will be enthusiasts and professionals willing to pay premium prices for extended battery life.

What's the cost difference between magnonic devices and current silicon chips?

Initial magnonic devices will be more expensive than mature silicon products because they require specialized materials and new manufacturing processes. Cost projections are uncertain because production costs depend on manufacturing scale and process maturity. History suggests that once volume reaches sufficient scale, costs decline following semiconductor learning curves, with roughly 20-30% cost reduction for each doubling of production volume. Magnonic devices might cost 2-5x more than equivalent silicon initially, declining toward price parity within 5-10 years of volume production. Exact costs depend on specific applications and comparison products, making precise predictions difficult until production data becomes available.

Can magnonic technology solve data center cooling challenges?

Partially, yes. Magnonic processors generate far less heat than silicon, reducing cooling infrastructure requirements. The Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) of data centers—the ratio of total power to computing power—could improve from current ~1.67 to potentially 1.3 or lower. This means more computing per watt of electrical draw and less cooling required. However, magnonic technology won't eliminate data center cooling needs. Heat-generating components will still exist (power supplies, networking equipment, storage infrastructure), and removing heat from facilities remains necessary. The benefit is substantial reduction rather than complete elimination of cooling infrastructure.

What about electromagnetic radiation or safety concerns with magnonic devices?

Magnonic devices themselves generate minimal electromagnetic radiation because they operate at different frequencies than conventional electromagnetic devices. The light sources (visible light lasers) used for control pose no unique radiation hazard beyond standard laser safety protocols. The magnetic fields involved are modest, typically less than 200 millitesla, comparable to MRI scanning equipment's magnetic fields. Safety standards and precautions appropriate for current magnetic devices and laser systems would apply to magnonic devices. No unique hazards have been identified, but thorough safety testing is necessary before biomedical applications become practical.

How does magnonic computing affect power consumption compared to quantum computing?

Quantum computers and magnonic computers operate on fundamentally different principles and target different problem types. Magnonic computers are general-purpose processors that could replace silicon for many applications, offering orders of magnitude power reduction through different physics. Quantum computers are specialized processors for specific problem classes (optimization, simulation, cryptography) that provide exponential speedups for those problems but aren't general-purpose. The power consumption comparison depends heavily on the specific application. For general computing, magnonic systems likely outperform quantum. For quantum-suitable problems, quantum computers provide unique advantages. Future systems will probably include both technologies, each optimized for its strengths.

The Future Is Magnetic, Optical, and Remarkably Efficient

The demonstration of room temperature laser control of magnons represents more than a technical achievement. It's evidence that computing's next chapter will be written with different physics and different paradigms.

We've built extraordinary computational capability by making silicon transistors smaller and smaller. That path has physical limits fast approaching. The next generation of computing performance and efficiency will come from new materials, new mechanisms, and new architectures.

Magnonic technology is one of the most promising paths forward. It combines fundamental physics advantages with compatibility with existing manufacturing infrastructure. It offers solutions to real problems that limit current technology: data center power consumption, portable device battery life, processing speed, and thermal management.

The journey from laboratory research to mainstream adoption typically spans 10-20 years. Magnonic computing is probably 5-7 years away from first commercial products, 10-15 years from mainstream adoption. That's not distant future. Engineers graduating from university today will work with magnonic systems in their careers.

The competitive advantage goes to early adopters: companies that integrate magnonic technology into products, startups that build specialized applications, regions that develop manufacturing expertise, and professionals who invest in understanding the technology now.

The research published in Nature Communications isn't just another technical paper. It's a signal that the post-silicon computing era is arriving, and the promise is remarkable.

Key Takeaways

- Visible light lasers now control magnon frequencies at room temperature, shifting them up to 40% without extreme cooling or equipment.

- Nanometer-scale magnetic materials integrate with existing semiconductor manufacturing, making commercial deployment feasible within 5-7 years.

- Applications span faster hard drives, spin-based computing replacing silicon, and reconfigurable hardware that changes behavior through light-based programming.

- Data centers could reduce power consumption by 20-50% using magnonic storage and computing, translating to billions in operational savings annually.

- Timeline from research breakthrough to mainstream adoption in consumer devices is probably 10-15 years, but early applications in data centers emerge first.

Related Articles

- Best Spotify Alternatives 2025: Complete Comparison Guide

- Next-Gen Battery Tech Beyond Silicon-Carbon [2025]

- LG C5 OLED 65-Inch TV Deal: Save $1,500 + Expert Buyer's Guide [2025]

- Jensen Huang's Reality Check on AI: Why Practical Progress Matters More Than God AI Fears [2025]

- The Nolah Evolution Hybrid Mattress: Complete Buyer's Guide [2025]

- Master Your Nespresso Machine: 5 Pro Tips for Better Coffee [2025]

![Laser-Tuned Magnets at Room Temperature: The Future of Storage & Chips [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/laser-tuned-magnets-at-room-temperature-the-future-of-storag/image-1-1768518545025.jpg)