Introduction: Why Your Phone Battery Hasn't Gotten That Much Better

Here's something that'll frustrate you: your phone's battery capacity has barely budged in five years. The iPhone 15 Pro Max holds 4,685 mAh. The iPhone 11 Pro Max? 3,969 mAh. That's only an 18% improvement over a decade.

Meanwhile, processor speeds tripled. Cameras went from nice to genuinely mind-blowing. Screens became stunning. But battery? It's stuck in first gear.

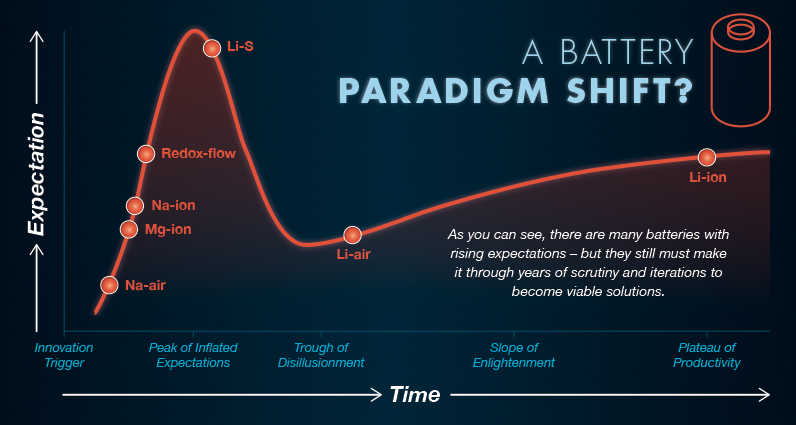

The problem isn't a lack of trying. It's physics. Lithium-ion batteries—the same tech powering your phone since the iPhone 6—have hit a wall. They can't hold much more charge without getting heavier, hotter, or exploding. We've squeezed every last drop of efficiency from them.

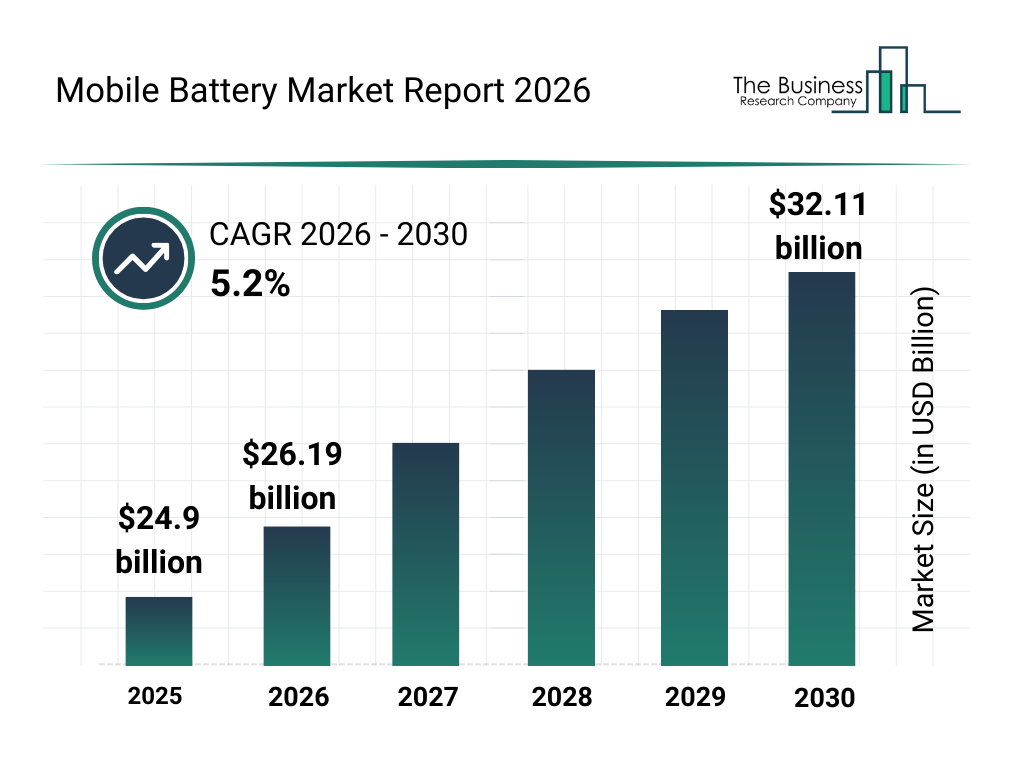

But something's shifting. Not in the next year, maybe not even the next three. But manufacturers aren't waiting around anymore. They're investing billions in technologies that could genuinely transform what "all-day battery" means. We're talking phones that last two, three, maybe even four days on a single charge.

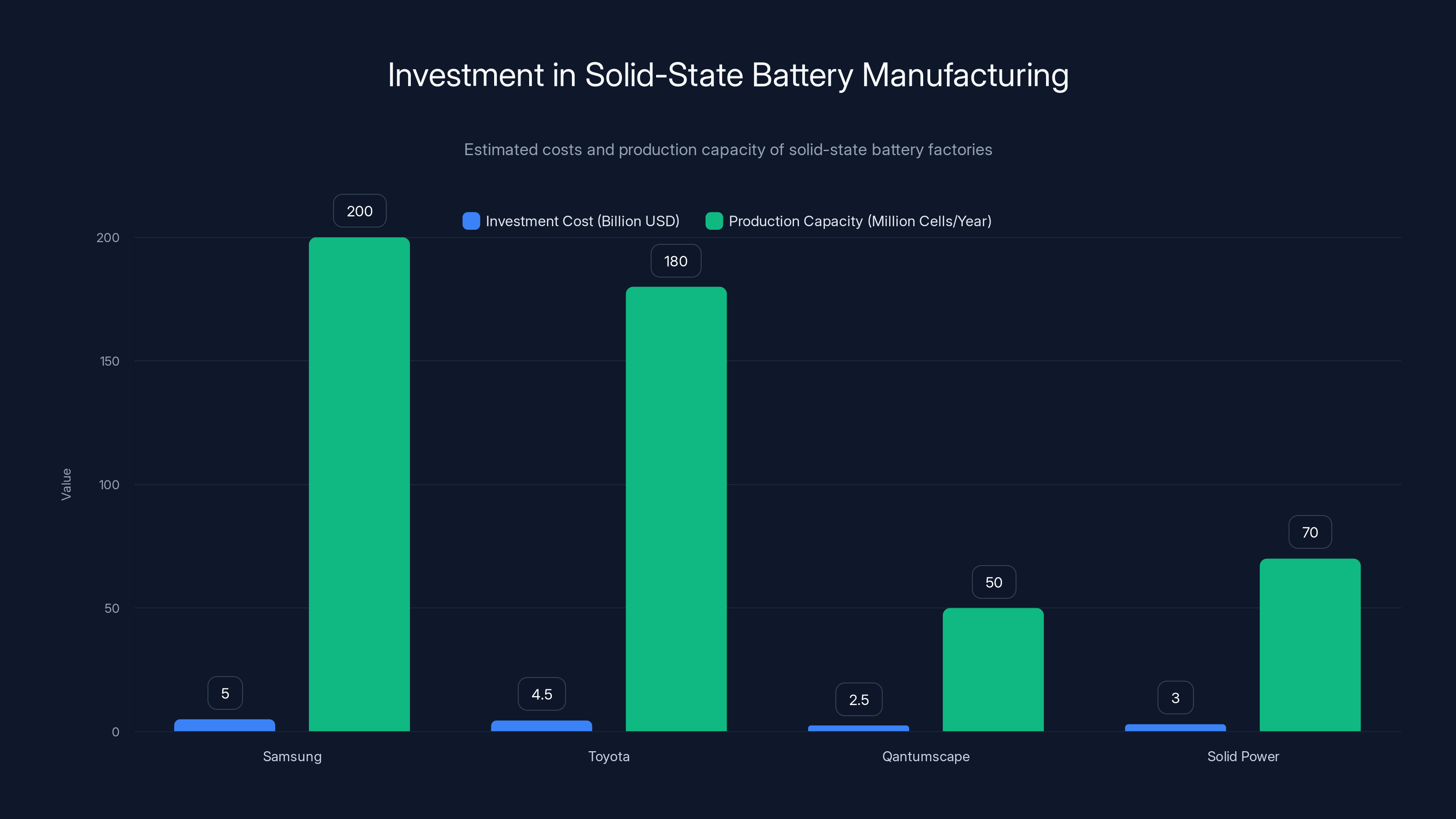

The technologies aren't fictional. They're not vaporware promises from startups. Major players like Tesla, Samsung, Toyota, and Apple are building them in labs right now. Some are already showing up in limited production runs.

This article breaks down the real next-generation battery technologies that could finally free us from the daily charging ritual. Not the pie-in-the-sky stuff. The actual innovations that companies are betting their futures on, the timelines for when you might actually use them, and why each one matters.

Let's start with what's coming fastest.

TL; DR

- Silicon-Carbon is the immediate win: Companies like Samsung and Tesla are already using silicon-based anodes that improve capacity by 30-40% without major redesigns, arriving in phones by 2025-2026.

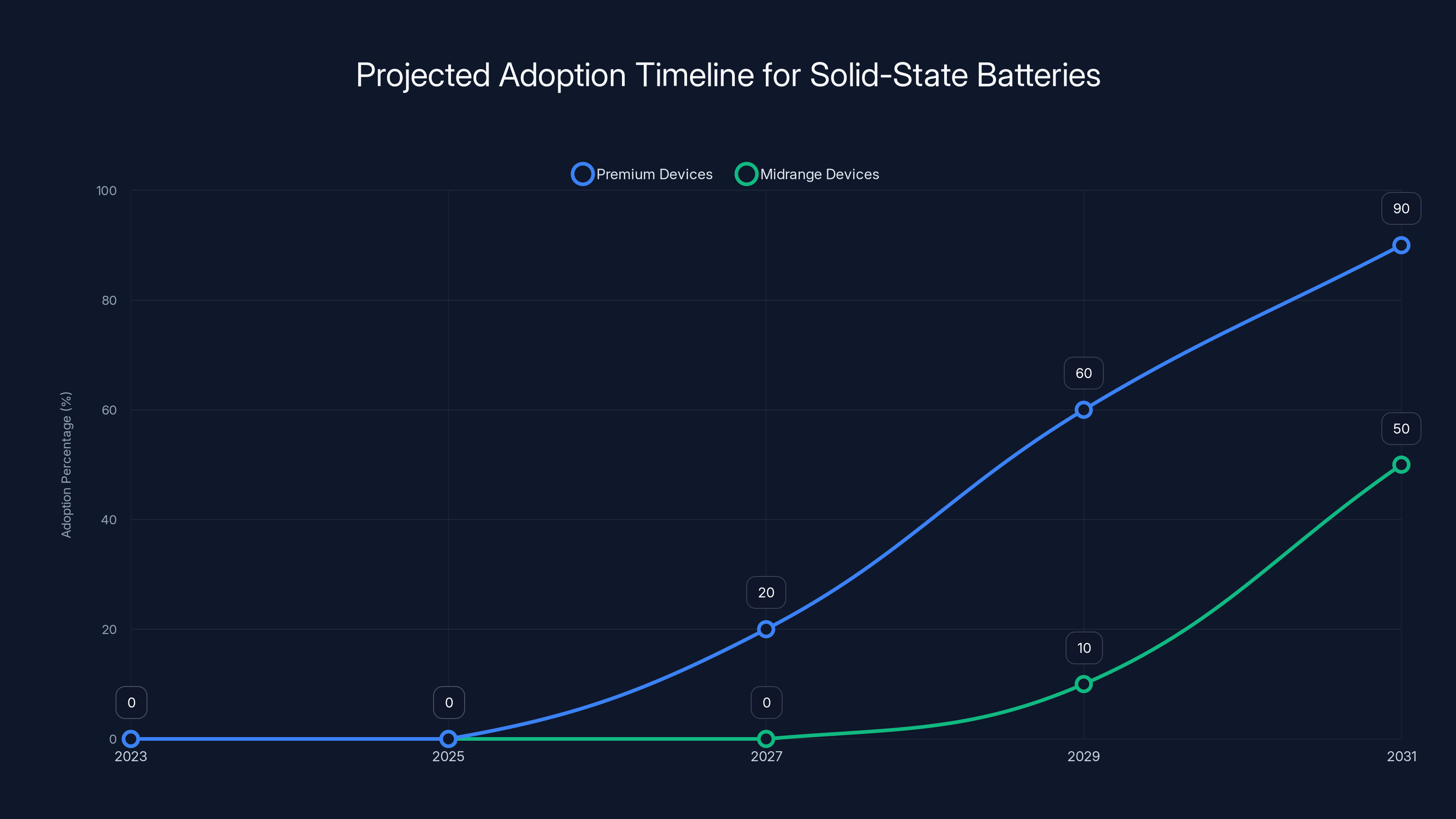

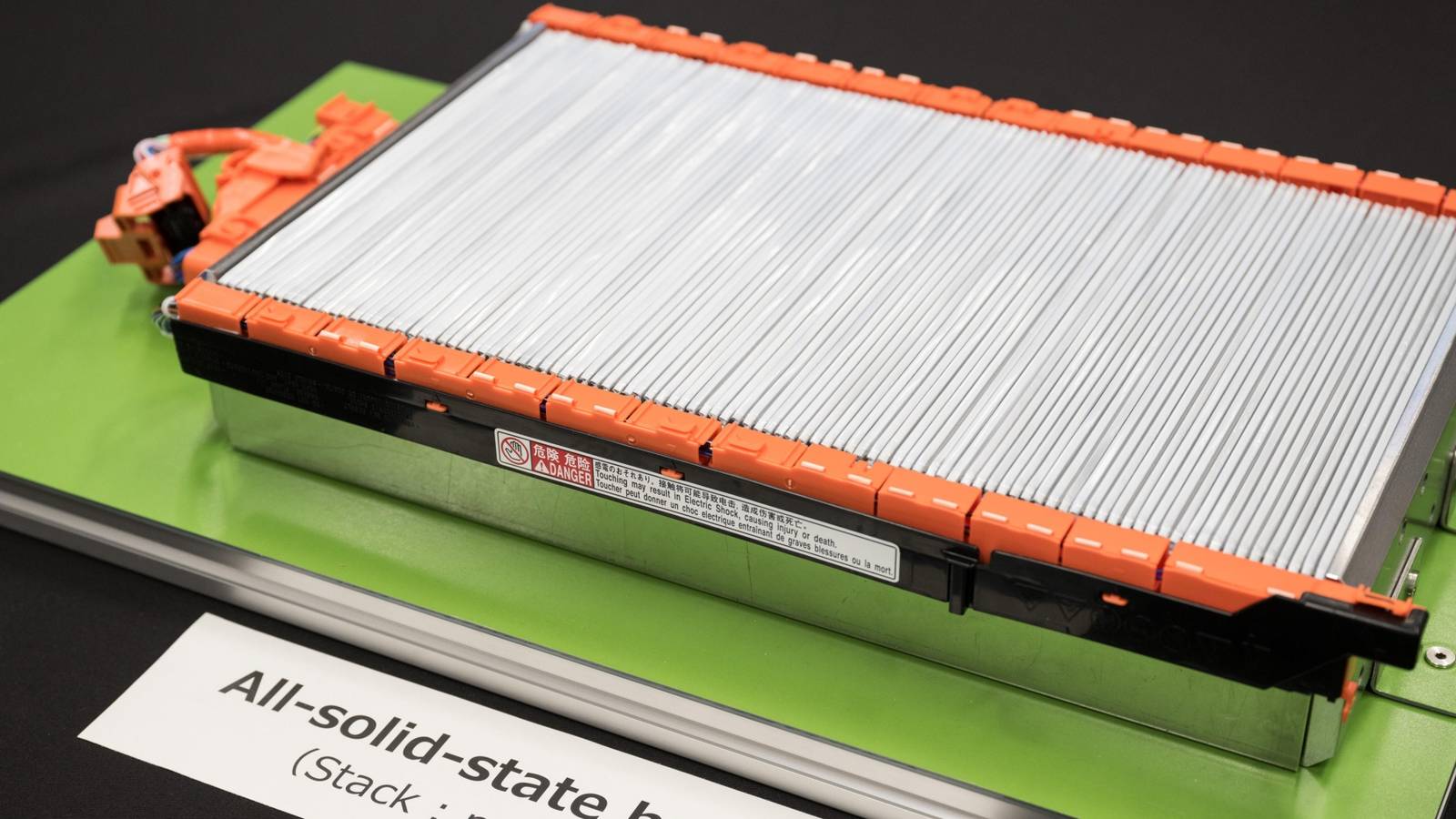

- Solid-state batteries are the game-changer: By replacing liquid electrolyte with solid material, energy density nearly doubles while reducing fires, with commercial rollout expected 2027-2030.

- Structural batteries integrate into device frames: Companies including Tesla and Apple are testing batteries that double as chassis, saving 30-40% weight, potentially launching in flagship phones by 2026-2028.

- Lithium-metal anodes offer extreme density: Trading cycle life for massive capacity gains, these suit premium devices and EVs better than daily phones, though production scaling remains challenging.

- The real barrier isn't technology—it's manufacturing: Every breakthrough must pass through the grinder of large-scale production, cost-per-kWh targets, and supply chain realities that slow deployment to 3-5 year timelines.

Samsung and Toyota lead in investment and capacity for solid-state battery manufacturing, with higher production capabilities. Estimated data.

Understanding the Battery Crisis That Isn't Really a Crisis

Wait, let's be honest about something first. Your phone's battery isn't actually terrible. Modern lithium-ion cells hold a charge for over a thousand cycles before degrading. They're reliable, reasonably safe (for the most part), and cheap enough to mass-produce. The real problem? We've hit the physics ceiling.

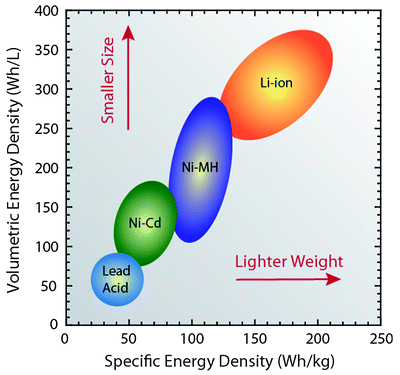

Energy density—the amount of energy stored per unit of weight or volume—is the metric that matters for phones. And lithium-ion has fundamentally limited energy density. The theoretical maximum is around 300-400 Wh/kg. Current commercial cells run at 200-250 Wh/kg. We're not far from the limit.

Here's the math: if you want a phone that lasts three days instead of one, you need roughly three times the energy. With current batteries, that means three times the weight. A 200-gram phone becomes 600 grams. That's not a phone, it's a brick.

So manufacturers face an impossible choice. Keep current battery tech and accept daily charging. Or find something fundamentally new.

That's why every major player is pivoting. And that's why the next five years matter.

Silicon-Carbon Anodes: The Bridge Technology

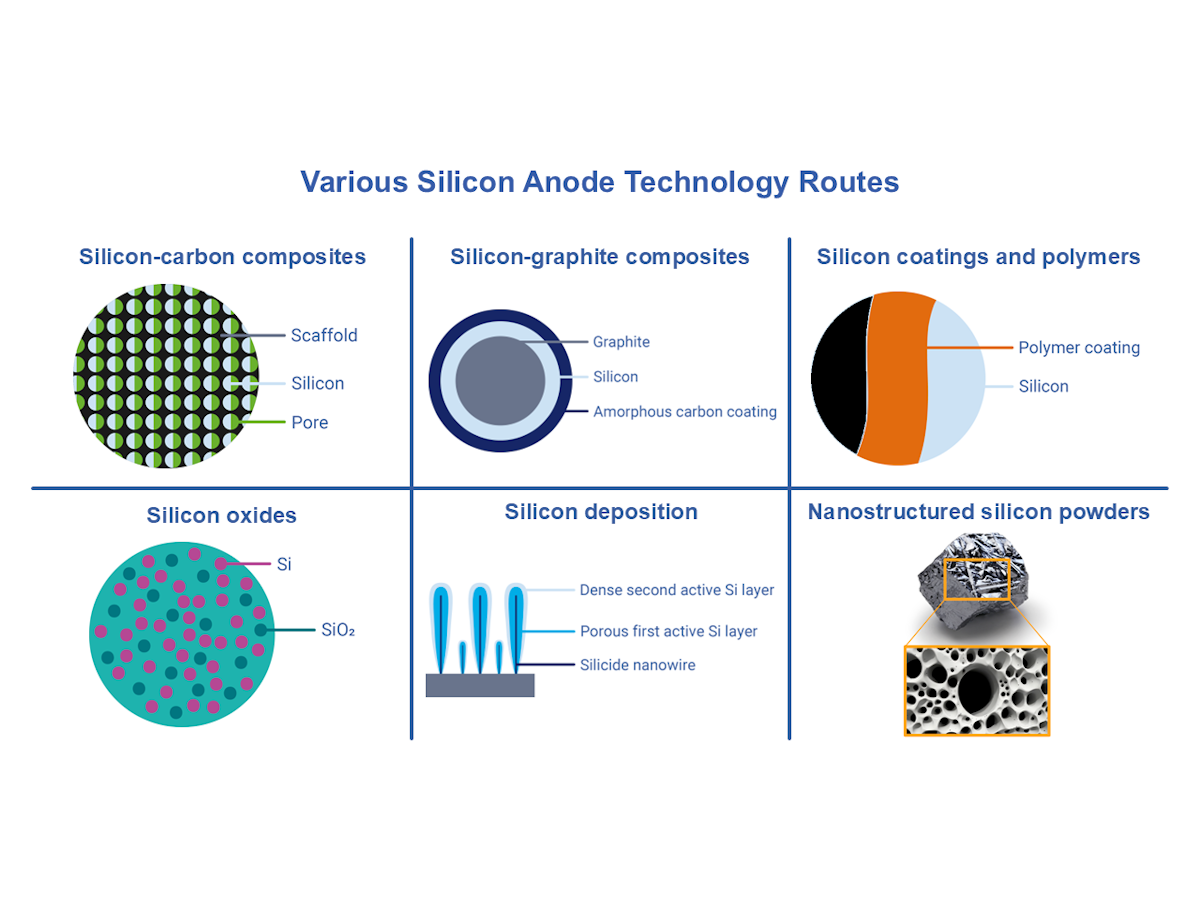

Let's start with what's already coming. Silicon-carbon hybrid anodes are the near-term fix, and they're way less exciting than everything else on this list. But that's actually why they matter.

Currently, phone batteries use graphite anodes. They work fine. They're proven. But graphite has a hard ceiling on how many lithium ions it can hold. Silicon can hold way more. Roughly ten times more by weight. The problem? Silicon expands and contracts dramatically during charging cycles, destroying the electrode structure. After a handful of charge cycles, the battery falls apart.

The solution: mix silicon with carbon. The carbon acts like a structural scaffold. It holds everything together while the silicon does the heavy lifting. The result? You get 30-40% more capacity in the same physical space, with roughly the same lifespan as current batteries.

This is already happening. Samsung announced silicon-carbon batteries for flagship phones starting in 2024-2025. Tesla's using similar tech in newer vehicles. The tech isn't revolutionary. It's just... better.

Why it matters for phones: You probably get a phone with 30-40% more battery capacity in 2025 or 2026 without manufacturers changing the phone's size. That's genuinely useful. It's not three days of battery. More like 1.5 days instead of one day. But that's real improvement.

The catch? It costs more to manufacture. Current production lines need some tweaking. And the improvements plateau after 40% because you can't push silicon much higher without the degradation problem getting worse. It's a bridge technology, not a destination.

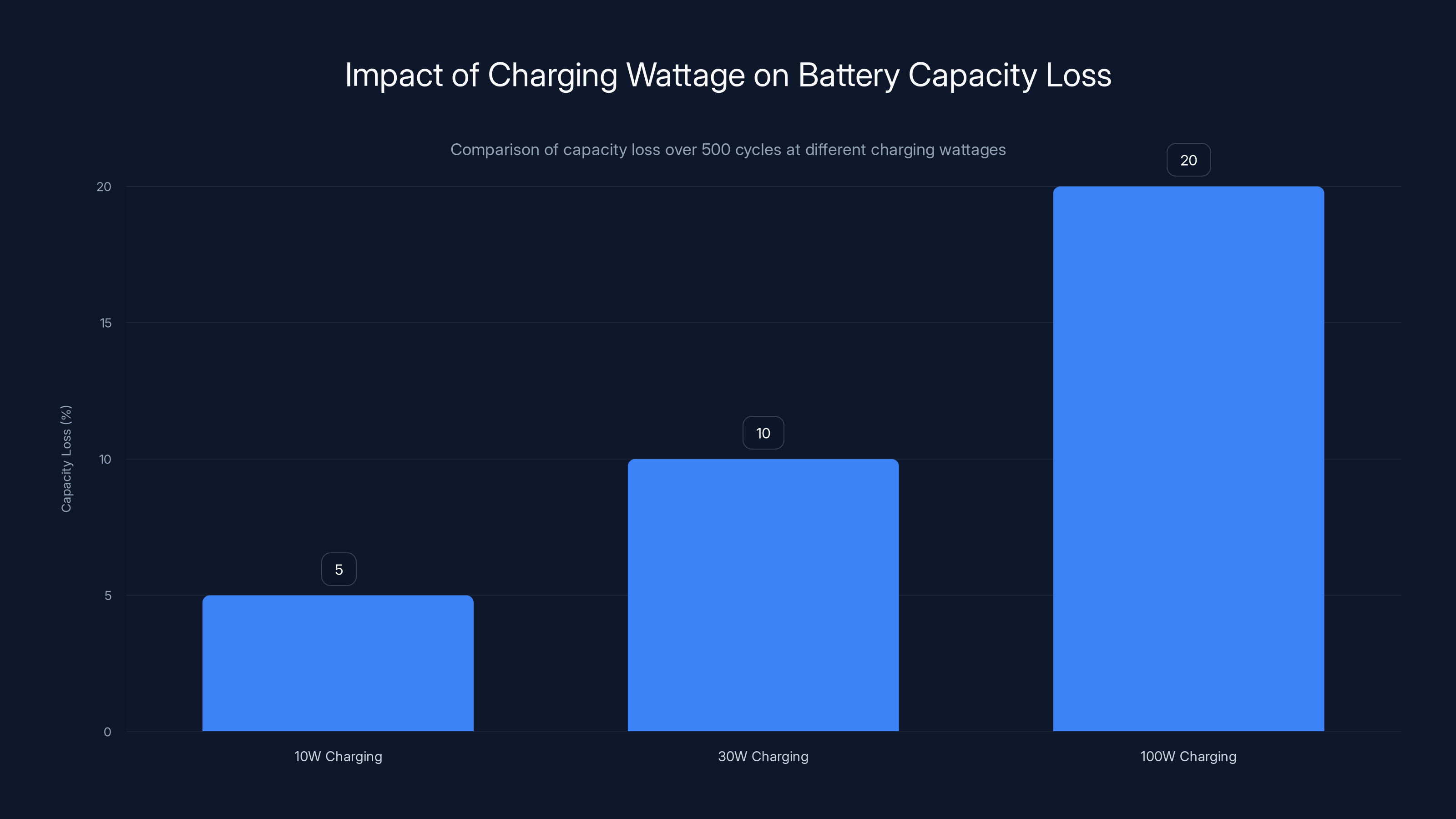

Higher charging wattages lead to significantly more battery capacity loss over 500 cycles. Estimated data based on typical usage.

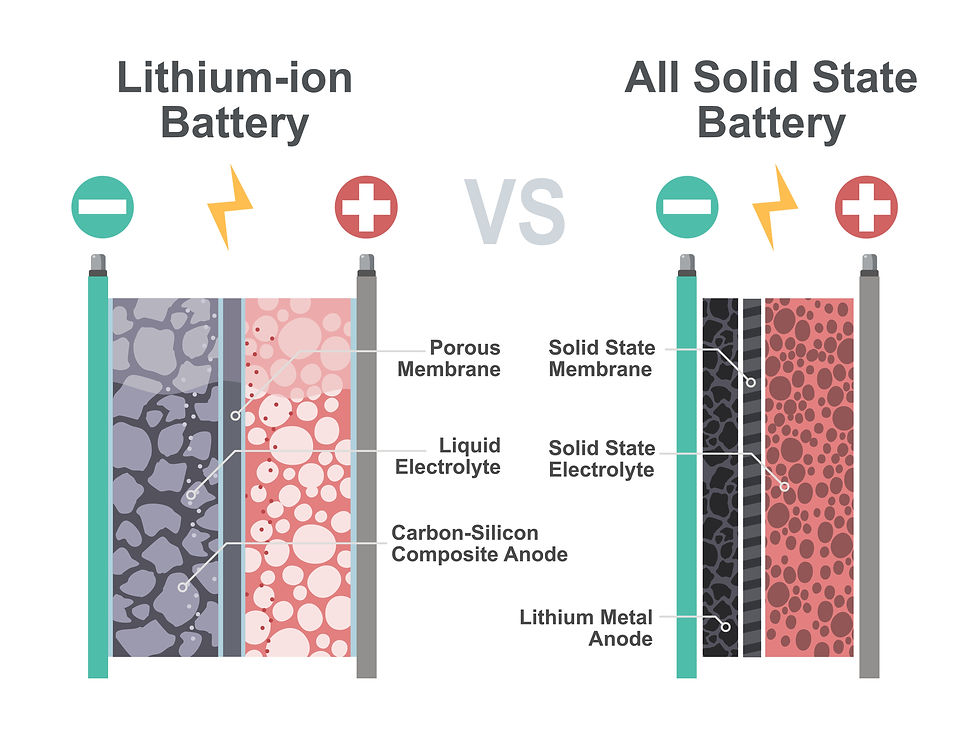

Solid-State Batteries: When the Electrolyte Becomes Solid

Now here's where things get weird. And promising.

Every lithium-ion battery has three parts: a positive electrode (cathode), a negative electrode (anode), and the stuff in between (electrolyte). In current batteries, the electrolyte is a liquid. It lets lithium ions move from one electrode to the other during charging and discharging.

That liquid is also flammable. That's why phone batteries catch fire occasionally. The liquid also limits voltage stability, which limits energy density. And it evaporates or degrades over time, which limits lifespan.

Solid-state batteries replace that liquid with a solid ceramic or polymer material. Lithium ions still move through it. But now you've got a material that doesn't burn, supports higher voltages, and lasts longer.

The benefits are genuinely massive. Energy density potentially doubles, hitting 400+ Wh/kg in production cells. That translates to phones lasting 2-3 days without proportional size increases. Fire risk drops dramatically. Battery lifespan extends to 1,000+ cycles without significant degradation.

Toyota, Samsung, Volkswagen, and others have working prototypes. Tesla has been talking about solid-state cells for years. Apple's rumored to be investing heavily.

When will you actually use them? Probably 2027-2029 in premium phones, maybe 2030-2032 as they scale to midrange devices. The manufacturing complexity is brutal. You can't just adapt existing production lines. Every stage—electrode coating, electrolyte deposition, cell assembly—needs reinvention.

The catch? Cost. Current solid-state prototype cells cost 3-5 times more than lithium-ion equivalents. Scaling production will drive costs down, but the first phones with solid-state batteries might cost $1,500+. They'll be premium flagship devices, not mass-market phones.

Structural Batteries: The Chassis That Stores Energy

This is the one that genuinely blows people's minds once they understand it.

Currently, batteries are separate components inside phones. They occupy space. They add weight. Tesla and others are working on something radically different: batteries that double as the structural frame of the device.

Imagine a phone where the battery isn't a separate module. It's the backbone. The battery's casing provides structural rigidity. The electrodes are integrated into materials that also support the display and circuits. You're not adding weight to hold the battery and the structure separately. The battery becomes the structure.

The benefits sound magical. Weight reduction of 30-40% in the battery system. Freed-up internal space for larger cells or other components. Potential cost savings through simplified assembly. And you still get the capacity increase from better electrode materials.

Tesla is already working on this. They've shown prototypes of structural battery packs that carry load while storing energy. Apple's rumored to be exploring similar approaches. Some evidence suggests the company's testing integrated battery-chassis designs in development labs.

For phones, this would be revolutionary. A 200-gram phone could become 140 grams while keeping the same battery capacity. Or maintain weight while doubling battery size. That's the kind of breakthrough that actually changes how devices feel and perform.

When's it arriving? 2026-2028 seems realistic for early adoption in flagship devices. The manufacturing challenges are real but solvable. The bigger challenge is thermal management and safety testing. You need to ensure the structural battery doesn't fail under impact or extreme temperatures.

The downside? Repairability becomes harder. If the battery fails, you're potentially replacing the entire chassis. Production costs might initially be higher despite the material savings, because the manufacturing tolerance requirements are extreme.

Lithium-Metal Anodes: Maximum Density, Maximum Complexity

Lithium-metal anodes represent the most radical departure from current technology. Instead of using graphite or silicon, you use pure lithium metal as the anode.

On paper, this is insane. Lithium metal can hold 10 times more charge than graphite, per unit weight. That means energy density could hit 500+ Wh/kg—essentially unlimited compared to current phones. Your phone could last a week on a charge. Theoretically.

Practically? It's a nightmare. Lithium metal is incredibly reactive. It corrodes instantly when exposed to air or moisture. During charging, lithium deposits unevenly on the anode, forming branch-like structures called dendrites that eventually pierce the separator and short the battery. The first lithium-metal batteries lasted maybe five charge cycles before failing.

But companies haven't given up. Samsung, Solid Power (now part of BMW), and others are developing solid-state lithium-metal cells that solve these problems through careful electrolyte design and protective coatings. The results are promising. Prototypes now last hundreds of cycles.

For phones? Probably never. Lithium-metal cells are better suited to applications where you need extreme energy density but don't care about cycle life, like aerospace or emergency backup power. For a phone you charge daily, you'd wear out the battery in six months to a year.

But they matter for electric vehicles, and battery tech often trickles down from EVs to phones. So paying attention to lithium-metal development tells you what's coming next.

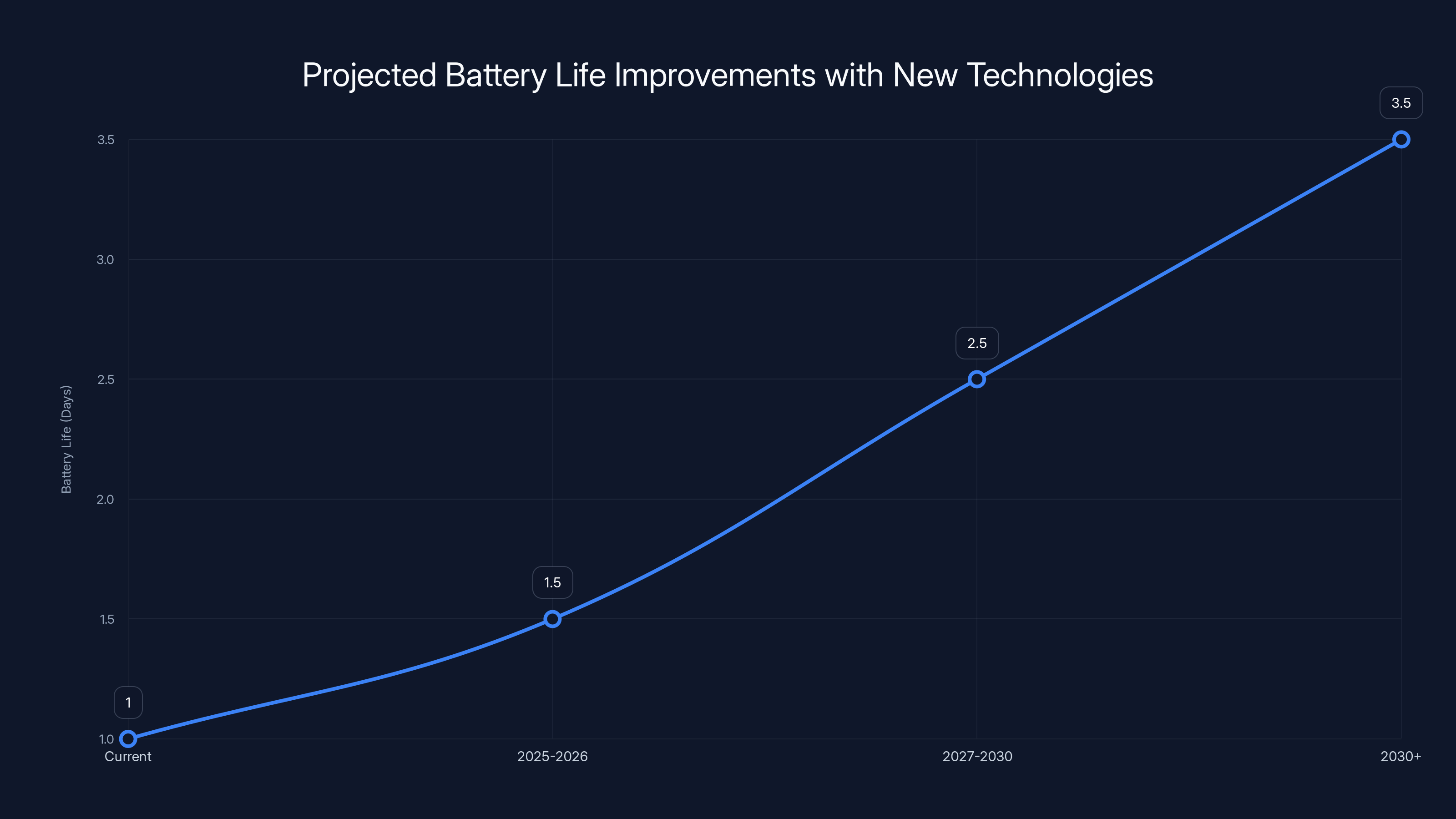

Estimated data shows that silicon-carbon and solid-state batteries will significantly extend phone battery life, reaching up to 3.5 days by 2030+.

Lithium-Polymer and Gel Electrolytes: The Quiet Alternative

Solid-state gets all the attention. But there's a quieter path happening in parallel: lithium-polymer (LiPo) and gel electrolyte batteries.

These use a semi-solid electrolyte—not quite liquid, not quite solid. Usually a polymer matrix containing liquid electrolyte, or a gel that behaves like both.

Why do they matter? Because they're genuinely halfway there. They're harder to manufacture than current lithium-ion, but not nearly as hard as true solid-state. Energy density improvements are more modest (maybe 15-25% rather than 50-100%), but they're real. Safety improves because the gel doesn't slosh around and ignite as easily.

More importantly, existing production lines can be retrofitted. You don't need an entirely new factory. You can integrate gel batteries into current manufacturing with modifications.

Companies like LG Chem, Panasonic, and others are quietly pushing this approach. It won't make headlines. You won't see press releases saying "revolutionary new battery." But sometime around 2025-2026, you'll notice your phone has 15-20% better battery life and the manufacturer will mention "advanced gel electrolyte" in tiny print on the spec sheet.

This is actually the tech that will probably reach your hands first, precisely because it doesn't require reinventing everything.

Cathode Materials: The Other Half of the Equation

All this discussion focuses on anodes. But cathodes matter equally.

Current phone batteries use lithium cobalt oxide cathodes or variants. They're stable and proven, but they have limits. The cobalt is also expensive and comes with serious ethical concerns around mining practices.

Companies are moving to nickel-rich cathodes, NCMA (nickel-cobalt-manganese-aluminum), and other chemistries. The benefits include higher energy density, reduced reliance on cobalt, and better cycle life.

But the real game-changer is lithium iron phosphate (LFP) cathodes. They're cheaper, safer, longer-lasting, and use iron instead of cobalt. The trade-off? They have lower energy density. So they're better for applications where weight doesn't matter—like stationary energy storage or vehicles where you can tolerate more weight.

For phones, you probably won't see LFP anytime soon. But watch the EV space. As LFP dominates vehicle batteries, the scale drives costs down. Then you'll see companies experimenting with LFP-based phone batteries as a premium option for people who prioritize durability over thinness.

Temperature Management: The Invisible Battle

Here's something nobody talks about: heat.

New battery technologies push higher energy densities and faster charging. Both generate heat. And heat kills batteries. It accelerates chemical degradation, reduces cycle life, and increases fire risk.

Every next-generation battery technology brings heat management challenges. Solid-state cells can support higher voltages but generate more heat at those voltages. Lithium-metal cells are more thermally unstable. Even silicon-carbon anodes produce more heat during rapid cycling.

Manufacturers are responding with better thermal management. Graphene layers to conduct heat away from cells. Thermally conductive adhesives between battery and chassis. Active cooling systems in premium devices that pump coolant directly against battery packs.

For users, this means the next generation of phones might be thicker, or more expensive, or both. The heat dissipation infrastructure takes up space and cost. It's the invisible tradeoff nobody mentions when companies announce battery breakthroughs.

This also affects charging speed. Faster charging generates more heat, which limits how aggressively you can charge without damaging the battery. So even when capacity improves, charging speeds might not increase proportionally.

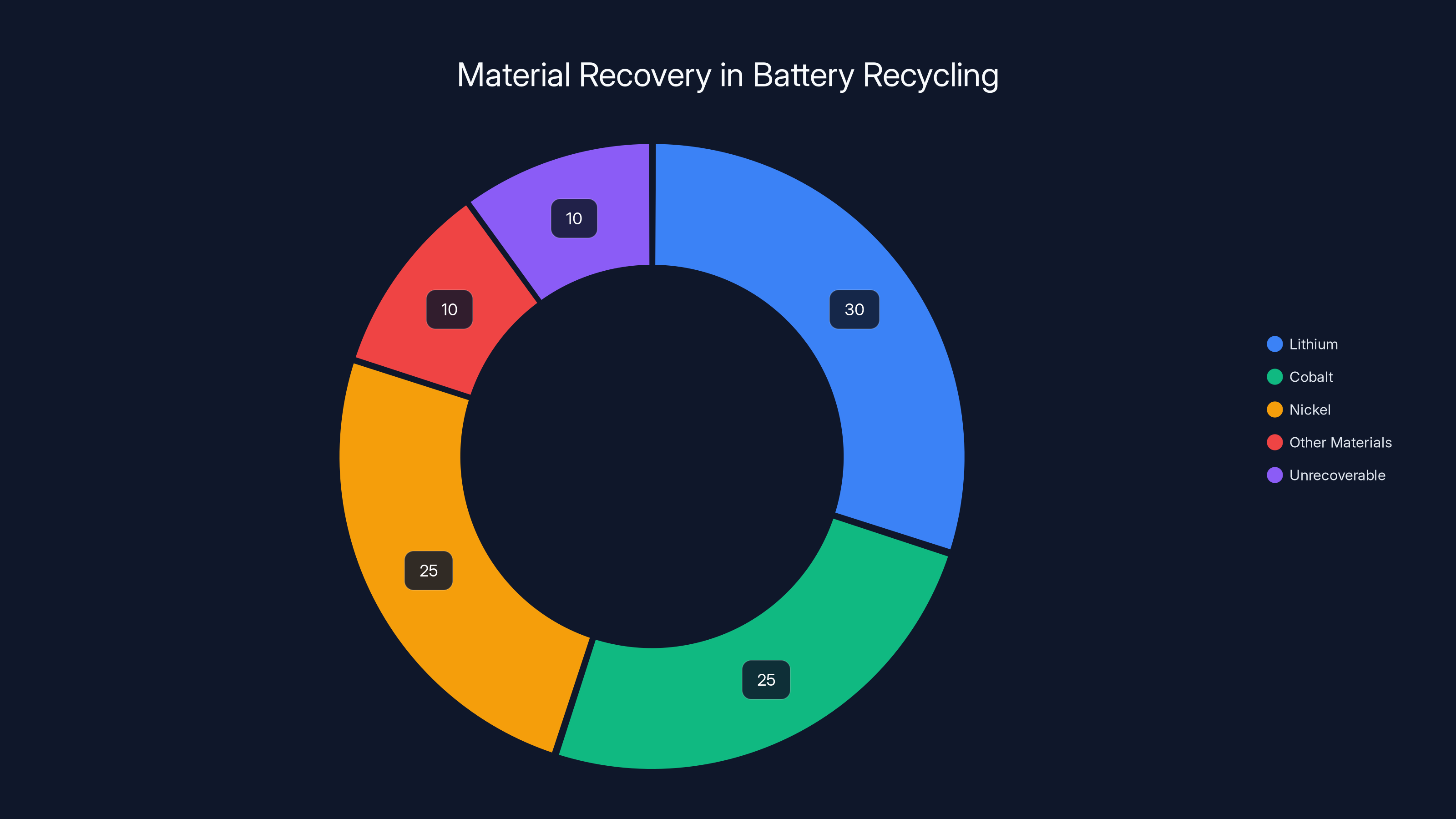

Recycling processes typically recover 80-90% of materials from batteries, with lithium, cobalt, and nickel being major components. Estimated data.

Fast Charging: The Speed Limit

While we're on the topic of charging, let's address the elephant in the room: fast charging isn't as fast as marketing suggests, and the tradeoffs are real.

Current flagship phones support 30-120W fast charging. A few claim higher. The benefits sound good until you realize what's actually happening. Charging a battery at higher power degrades it faster. Every time you fast-charge, you're trading long-term battery health for short-term convenience.

Data shows that phones charged with 10W charging lose less capacity over 500 cycles than phones charged with 100W. The difference is substantial—maybe 10-15% capacity loss difference.

So manufacturers face a choice: market fast charging and accept that consumers replace batteries more frequently, or limit charging speeds and lose the marketing advantage.

This changes with new battery technologies. Solid-state batteries can handle higher charge rates with less degradation. Structural batteries with better thermal management can dissipate heat from fast charging. So next-generation phones might actually offer genuinely fast charging without the heavy lifespan penalty.

But we're not there yet. If you want your current phone's battery to last, stick with 10-30W charging and avoid the rapid-charging hype.

Production Scaling: Where Good Labs Go to Die

Here's the uncomfortable truth nobody tells you about battery technology: the gap between "works in the lab" and "mass-produced" is enormous.

Take solid-state batteries. Researchers have made excellent prototypes. They work great for 1,000 cycles. Then you try to make 10,000 of them per day on an automated line, and suddenly every single one is slightly different. Thickness varies by 5%. Coating distribution isn't uniform. Temperatures during assembly fluctuate. And 99% of the batch works great while 1% fails catastrophically.

That 1% failure rate isn't acceptable in phones. Batteries catching fire is a nightmare. So you implement more quality controls, which slows production and raises costs. You simplify the design to reduce variables. You discover a new failure mode and go back to the drawing board.

This is why every manufacturer's "coming soon" battery announcement has a 3-5 year gap before it actually appears in products. It's not that they're lying. It's that manufacturing at scale is hideously difficult.

The companies being realistic about this timeline? Samsung, Toyota, and Tesla for solid-state. They're saying 2027-2030 for actual production. Smaller startups claiming 2025-2026? Probably selling hype.

This also explains why batteries are expensive. The capital investment in manufacturing facilities, tooling, and quality control is enormous. A solid-state battery factory costs billions to build. You need to produce at scale to amortize that cost. So the first solid-state phone batteries will be expensive. Decade-long or more supply constraints could maintain those high prices.

Cost Per kWh: The Real Metric That Matters

Industry folks obsess over one metric: dollars per kilowatt-hour ($/kWh). It's the economic efficiency of battery production.

Current lithium-ion batteries are around $100-130 per kWh in volume production. That's the floor. Companies have spent 20 years optimizing this figure. Further improvements are incremental.

Solid-state prototypes?

Why does this matter for phones? Because phones don't price batteries separately. The $999 flagship phone includes the battery in the overall cost. If solid-state batteries cost 3x more, that either comes out of your wallet or forces compromises in other components.

More realistically, solid-state phone batteries will represent a 15-25% price premium for flagships. A

Lithium-metal and other exotic technologies? Even more expensive. We're talking $500+ per kWh in the near term. These won't come to phones for years unless something radical happens to manufacturing costs.

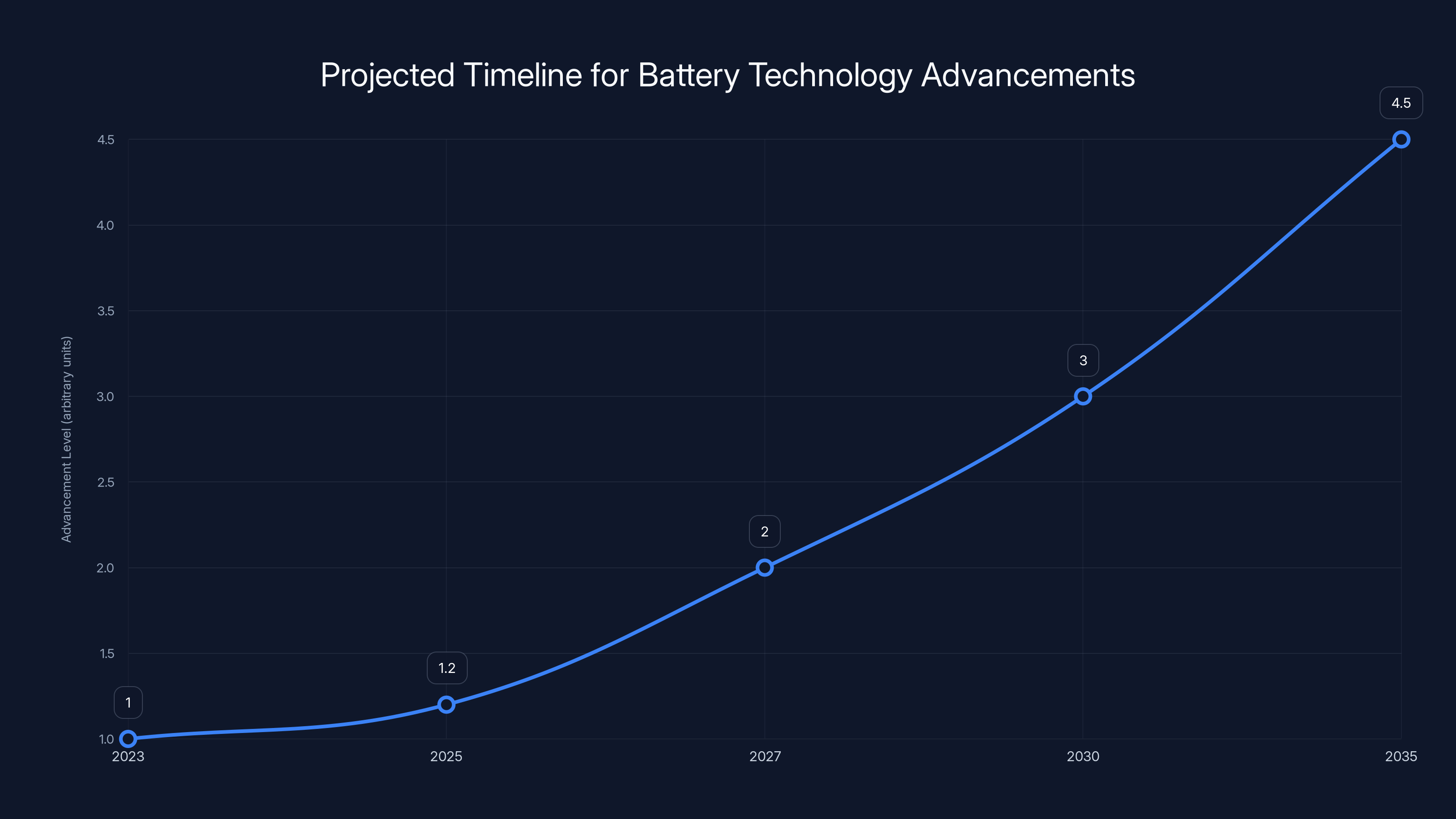

Estimated data shows incremental improvements in battery technology until 2027-2028, when a significant shift to multi-day batteries is expected. By 2035, solid-state batteries may become standard in midrange phones.

Graphene and Wonder Materials: Hype vs. Reality

You've probably read headlines about graphene batteries. Or carbon nanotube batteries. Or some other wonder material that'll revolutionize everything.

Most of it's hype.

Graphene is legitimately interesting. A single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb pattern with extraordinary conductivity and strength. In theory, it could revolutionize batteries. In practice? Adding graphene to batteries hasn't meaningfully improved real-world performance.

The reasons are frustrating. Graphene works great in small quantities. Adding lots of it to a battery changes other properties in bad ways. It increases density, raises cost, complicates manufacturing. The benefits don't outweigh the tradeoffs.

That doesn't mean graphene never helps. More likely, it becomes a minor component in composite materials that provide modest improvements. Not the revolutionary "graphene battery with 10x capacity" you've read about.

Other materials get similar treatment. Carbon nanotubes. Boron nitride. Sulfur cathodes. Each one shows promise in labs. Each one faces manufacturing or stability challenges that limit real-world impact.

When you see a headline about a startup claiming a revolutionary battery breakthrough, check: Do they have a factory yet? Have independent researchers verified the claims? Are major manufacturers licensing the technology? If the answer to most of these is "no," you're probably reading hype.

The boring truth is that incremental improvements to existing technologies deliver more value than occasional breakthroughs. Silicon-carbon anodes are less exciting than graphene. Solid-state electrolytes are less flashy than wonder materials. But they're what actually shows up in products.

When Will Your Phone Actually Get a Better Battery?

Let's cut through the noise and talk timeline.

2024-2025: Silicon-carbon anodes show up in some flagship phones. Expect 15-30% capacity improvements. A few manufacturers quietly debut gel electrolyte cells. You probably won't notice unless you specifically look at specs.

2025-2027: Silicon-carbon becomes common in flagships. Premium phones might reach 2+ days of battery. Some manufacturers begin small-scale solid-state production for testing and limited release. Structural batteries appear in concept devices and maybe one or two ultra-premium phones.

2027-2030: Solid-state phones launch widely. Energy density improvements allow true 2-3 day battery life in flagship devices. Prices drop as production scales. Structural batteries become standard in premium phones. Lithium-polymer gel cells dominate midrange devices.

2030+: Solid-state is mainstream in flagships. Midrange phones switch to solid-state or advanced gel electrolytes. Exotic technologies (lithium-metal, quantum dots) remain lab curiosities unless something radical changes. Daily charging becomes genuinely optional for most users.

This assumes no major breakthroughs. If someone figures out how to manufacture solid-state batteries at scale faster than expected, everything shifts earlier. If production keeps disappointing, everything shifts later.

Also note: manufacturers control the benefits. They could pack more capacity into existing form factors. Or maintain capacity while making phones thinner. Or split the difference. The next five years will likely see manufacturers prioritize thinness over endurance, so you might not actually feel the battery improvements even though they're substantial.

Environmental and Supply Chain Challenges

New battery technologies introduce new environmental and supply chain problems.

Solid-state batteries require rare materials for certain electrolytes. Lithium-metal cells need pure lithium, which is already becoming scarce. Even silicon-based anodes require processing that generates waste.

Lithium mining already creates environmental damage. Extracting lithium from salt flats in South America consumes massive amounts of fresh water in arid regions. As demand increases for new battery technologies, this pressure intensifies.

Manufacturers are aware of this. There's genuine investment in recycling technologies that extract lithium, cobalt, nickel, and other elements from spent batteries. This reduces mining pressure and creates secondary sources of critical materials.

But recycling is expensive and energy-intensive. It typically recovers 80-90% of materials. The remaining 10-20% represents losses that must be mined from fresh sources. So new batteries can't fully escape environmental costs.

The supply chain is also vulnerable. Cobalt is concentrated in specific regions. Nickel mining has geopolitical complications. Even the exotic materials in solid-state batteries (rare earths for certain ceramics) have concentration and sourcing issues.

This is actually pushing companies toward cobalt-free batteries like LFP, even though they're less energy-dense. The supply chain risk of cobalt-dependent technology is becoming unacceptable for major manufacturers.

Long-term, this means you might see phones shift toward more sustainable materials and chemistries, even if it means slightly worse battery performance. Environmental regulations are already moving in that direction in Europe, and other regions typically follow.

Solid-state batteries are expected to be adopted in premium devices by 2027-2029, with midrange devices following by 2030-2032. Estimated data based on industry trends.

The Role of AI and Machine Learning in Battery Development

One underappreciated force in battery development is machine learning.

Finding new battery materials means testing millions of combinations. Manually, that takes decades. With machine learning, you can predict how different chemistries will behave based on atomic structure, dramatically reducing the testing time.

Companies like Tesla, Samsung, and battery startups are using ML to accelerate materials discovery. Google's DeepMind has even applied AI to predicting battery chemistry stability, speeding up the process of finding formulations that don't degrade.

This doesn't mean AI discovers batteries from scratch. It means researchers can test ideas much faster, fail faster, and move on to better ideas. The timeline from "interesting idea" to "production-ready battery" is compressing.

This is why some near-term predictions about solid-state batteries hitting production in 2027-2028 are credible. The pace of materials research is genuinely accelerating due to computational advances.

The catch? AI can only accelerate research that's fundamentally solvable. If a battery chemistry has a hard physical limit, no amount of AI will overcome it. So don't expect AI to suddenly enable lithium-metal phones with 10-year battery life. But expect it to compress timelines and reduce dead ends.

What Happens to Old Battery Tech?

When new batteries arrive, what happens to current lithium-ion manufacturing?

It doesn't disappear. Lithium-ion is cheaper, proven, and reliable. It'll dominate midrange and budget phones for a decade or more. The factories producing lithium-ion will shift to supporting roles—powering IoT devices, backup power systems, and less demanding applications.

Some lithium-ion plants will retool to produce intermediate technologies like gel electrolytes or silicon-carbon cells. Some will close as production consolidates. Some will produce materials for recycling operations.

This transition period (2025-2035) will be messy. You'll see a fragmented market where different phone tiers use completely different battery technologies. Flagships use solid-state. Midrange uses gel electrolytes or advanced lithium-ion. Budget uses basic lithium-ion. Repair and supply chains become complicated.

Eventually, solid-state probably becomes the mainstream standard. But that's probably 2035 or later.

The Physics Frontier: Where Things Get Speculative

Beyond solid-state and lithium-metal, companies are exploring truly exotic approaches.

Lithium-sulfur batteries could theoretically offer 2-5 times the energy density of lithium-ion. The challenge? Sulfur dissolves in the electrolyte over time, gradually poisoning the battery. Researchers have made progress on this—it's not impossible, just hard.

Lithium-air batteries are even more speculative. They work with oxygen from the air as the cathode material. Theoretical energy density is absurd—10-15x lithium-ion. Real-world prototypes? Barely functional. They degrade rapidly, generate excessive heat, and the chemistry is unstable.

Sodium-ion batteries skip lithium entirely, using more abundant sodium. Energy density is lower, but sodium's cheap and the geopolitical supply risks are lower. You might see sodium-ion in midrange phones eventually, even though they're inferior to lithium-based tech.

Quantum-dot batteries are mostly vaporware at this point. The concept is fascinating—using quantum dots (nanoscale semiconductor crystals) to create batteries with properties we can tune at the atomic level. But the technology is decades away from practical application, if it ever arrives.

None of these are coming to phones in the next 5-7 years. But they're the reason battery research remains active. There's always the possibility someone figures out the trick that unlocks the next tier of performance.

How Phone Design Will Change With Better Batteries

When battery technology improves, phone design doesn't automatically improve. Manufacturers make choices.

Apple has historically chosen thinness. Even with better batteries, Apple could keep iPhone thickness the same and just extend battery life. Or keep battery life the same and thin it down. They'll probably do some of each.

Samsung tends to prioritize camera and display features. Better batteries might mean better cooling for cameras, or higher brightness displays without thermal problems.

Google tends to push computational features. Better batteries mean more power for always-on AI features.

What's unlikely: phone sizes staying constant while capacity becomes unlimited. More likely, the next three years see a gradual creep toward slightly larger phones with moderately better battery life, then around 2028 a sudden jump in battery life when solid-state arrives.

Also watch for form factor experiments. Rollable phones have failed so far partly because battery tech couldn't support their power demands. Better batteries might enable foldable designs that actually make sense. We might see phones that physically adapt their shape (partially rigid, partially flexible) to optimize for different use modes.

The boring take: phones will probably look nearly identical in 2030 to how they look today. Slightly thinner, slightly bigger screen-to-body ratio. The improvements happen in specifications you don't see. Battery life, charging speed, durability. That's less exciting than a revolution, but it's what's actually coming.

Comparing Next-Gen Battery Technologies at a Glance

| Technology | Energy Density | Timeline | Challenges | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon-Carbon | +30-40% | 2025-2026 | Cost, modest gains | Flagship phones now |

| Gel Electrolyte | +15-25% | 2025-2027 | Manufacturing scale | Midrange phones |

| Solid-State | +50-100% | 2027-2030 | Production complexity, cost | Premium flagships |

| Lithium-Metal | +200%+ | 2028-2032+ | Cycle life, stability | EVs, not phones |

| Lithium-Sulfur | +100-200% | 2030+ | Degradation, heat | Experimental |

| Sodium-Ion | -20% density | 2026+ | Lower performance | Budget devices |

| Structural | N/A | 2026-2028 | Repairability, safety | Lightweight premium phones |

The Real Constraint: Manufacturing Reality

Let's be brutally honest: the limiting factor isn't technology. It's manufacturing.

Every major battery advance requires entirely new production infrastructure. Building a solid-state battery factory costs $2-5 billion. You can't retrofit an existing lithium-ion line. The processes are fundamentally different.

So manufacturers face enormous capital decisions. Invest billions in new technology before you're sure it's worth it. Or stick with proven tech and accept market pressure.

This is why Samsung and Toyota are moving faster than some competitors. They have the capital to build solid-state factories speculatively. Smaller or more cautious manufacturers will wait for proven demand before investing.

This creates a vicious cycle. New batteries are expensive because they're low-volume. They stay low-volume because they're expensive. Only with time and scale do costs come down.

Breakthrough companies often promise to solve this with better manufacturing. They'll announce a factory that produces solid-state batteries at 30% cost compared to incumbents. Then the factory doesn't materialize, or it does but produces 1% of the claimed capacity, or it works fine but can't scale.

QuantumScape, Solid Power, and other solid-state startups have promised production timelines that keep slipping. Not because they're liars. Because manufacturing is harder than research.

Manufacturers who succeed at new battery technology won't be the ones with the best laboratory results. They'll be the ones who figure out how to make billions of cells per year consistently, cheaply, and safely. That's boring and unglamorous. But it's where the real work happens.

FAQ

What is silicon-carbon battery technology?

Silicon-carbon batteries replace the graphite anode in traditional lithium-ion cells with a mixture of silicon and carbon. Silicon can hold roughly ten times more lithium ions than graphite, while carbon provides structural stability to prevent degradation during charge cycles. The result is 30-40% higher capacity in the same physical space with similar durability to current batteries.

How much longer will next-generation batteries make phones last?

Silicon-carbon batteries arriving in 2025-2026 will extend battery life from roughly one day to about 1.5 days. Solid-state batteries (2027-2030 timeframe) could achieve 2-3 days of real-world usage on a single charge. Structural batteries might add another 30-40% improvement by reducing weight and enabling larger cells. The actual gains depend on how manufacturers choose to balance capacity improvements against design changes like thinness.

Are solid-state batteries safe?

Yes, more so than current lithium-ion cells. The solid electrolyte eliminates the flammable liquid found in traditional batteries, dramatically reducing fire risk. Solid-state cells also support higher voltage operation, which requires less cobalt and potentially uses safer cathode materials. The tradeoff is that manufacturing is more complex, so early solid-state batteries will be more expensive than proven lithium-ion technology.

When will solid-state batteries arrive in phones?

Production timelines suggest 2027-2030 for the first phones with solid-state batteries, probably limited to ultra-premium flagships from major manufacturers like Apple, Samsung, and others. Widespread adoption in midrange and budget phones likely occurs 2030-2035. Companies like Toyota and Volkswagen have stated solid-state production targets for 2027-2028 for vehicles, which may accelerate phone timelines slightly, but manufacturing scaling remains the primary constraint.

Why do new batteries cost so much more?

New battery technologies require entirely new manufacturing facilities, processes, and quality control systems. Building a solid-state battery factory costs $2-5 billion and takes years to construct. Initial production volumes are low because customers are cautious about unproven technology. High upfront capital costs divided by low production volume creates high per-unit costs. As production scales over decades, costs decline—but the first phones with new batteries will command significant premiums.

Is fast charging bad for batteries?

Fast charging (80W+) generates heat that accelerates chemical degradation, reducing battery lifespan by 15-25% compared to slower charging (10-30W). If you charge a phone with 100W charging, the battery might lose noticeable capacity after 18-24 months. With 10W charging, the same battery stays healthier for 2-3 years. New battery technologies like solid-state can handle fast charging with less degradation, but current lithium-ion batteries genuinely suffer from aggressive charging.

What about battery recycling and environmental impact?

Lithium mining creates real environmental damage, particularly water consumption in arid regions where lithium deposits are concentrated. Recycling programs can recover 80-90% of materials from spent batteries, reducing mining pressure, but the remaining losses require new extraction. New cobalt-free batteries like lithium iron phosphate and sodium-ion reduce reliance on problematic minerals, but introduce different tradeoffs. Long-term, environmental regulations will probably push phones toward less energy-dense but more sustainable battery technologies.

Will my next phone definitely have a better battery?

Probably, but not necessarily in the way you'd expect. Phones released in 2025-2026 with silicon-carbon anodes will have 15-30% higher capacity. But manufacturers might use this to make phones thinner instead of giving you longer battery life. The jump to genuinely longer battery life (2+ days) likely requires solid-state technology in 2027+, and those will be expensive premium devices. Midrange and budget phones might not see dramatic improvements until 2030 or later.

Conclusion: The Battery Revolution Is Coming, Just Not Quickly

Here's what we know. Silicon-carbon batteries are arriving now. Solid-state is genuinely coming in 2027-2030, not vaporware or marketing hype. Structural batteries and other innovations are following behind.

But the timeline is longer than you'd hope. Faster than a decade ago would've predicted, but still 3-5 years out before most people actually experience meaningfully better battery life.

The constraint isn't brilliant researchers. Samsung and Toyota have excellent battery labs. The constraint is manufacturing. Scaling from working prototypes to billions of units per year is genuinely, brutally hard.

When solid-state batteries do arrive, early phones will be expensive. We're talking $1,200-1,500 for the first devices. Prices will gradually decline over a decade as production scales. By 2035, the cutting edge will probably be something else entirely (lithium-metal? sodium-ion? something nobody's predicted?), and solid-state will be the standard in midrange phones.

For the next 2-3 years, expect incremental improvements. Silicon-carbon shows up in flagships. Battery life creeps up. Maybe from one day to 1.5 days if you're lucky and manufacturers don't use the extra capacity to thin the phone down.

Then in 2027-2028, if everything stays on schedule, the real shift happens. The first truly multi-day batteries. Phones that genuinely break free from daily charging cycles. That's when this technology story gets exciting.

Until then, if you want longer battery life, you have two options: turn off features, or buy a bigger phone and accept the weight. Neither is revolutionary. Both are better than hoping for a miraculous improvement that's still 3+ years away.

The good news? It's actually coming. The bad news? We're in the long waiting period where the technology works great in labs but barely exists in the real world. That gap closes every year. But patience is still required.

Key Takeaways

- Silicon-carbon batteries (30-40% capacity gain) arrive in flagships 2025-2026; they're incremental but real improvements using existing manufacturing.

- Solid-state batteries promise to double energy density but require entirely new $2-5B factories; expect 2027-2030 production, initially at premium prices.

- Structural batteries integrating into phone frames could reduce weight 30-40% while enabling larger capacity; realistic for ultra-premium devices 2026-2028.

- Manufacturing is the constraint, not materials science; every breakthrough requires solving production scaling, quality control, and cost reduction simultaneously.

- True multi-day smartphone battery life requires solid-state or comparable technology; your phone probably won't achieve that until 2028-2030 at earliest.

Related Articles

- Solid-State Batteries: The EV Revolution Finally Here [2025]

- Volvo EX60: 400-Mile Range and 10-Minute Fast Charging [2025]

- The 11 Biggest Tech Trends of 2026: What CES Revealed [2025]

- CES 2026 Tech Trends: Complete Analysis & Future Predictions

- Smart Chargers With Built-In Screens: The Anker Innovation [2025]

- Volvo EX60: 400-Mile Range and 400 kW Charging Explained [2025]