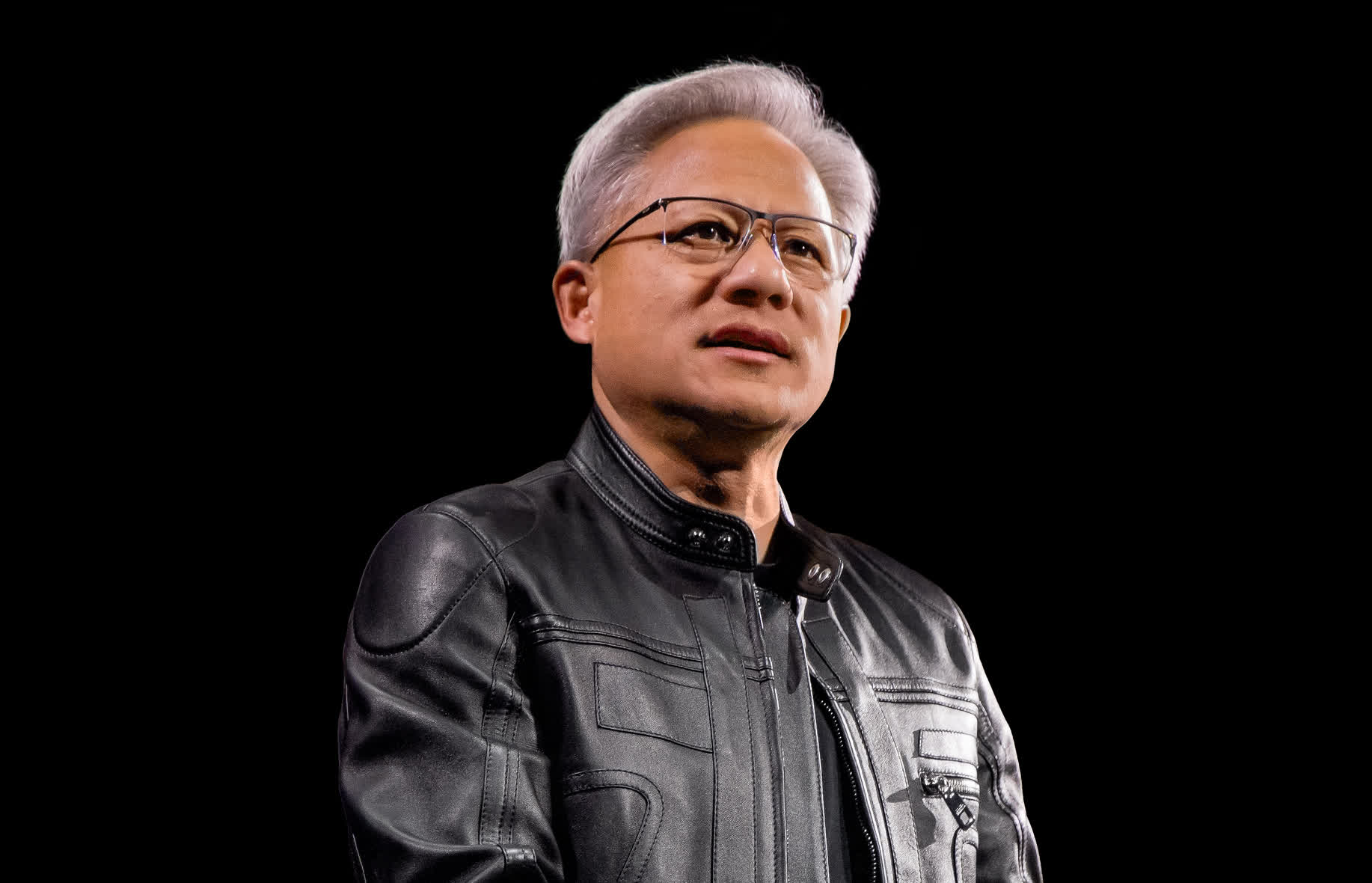

Jensen Huang's Reality Check on AI: Why Practical Progress Matters More Than God AI Fears

There's a lot of noise out there about artificial intelligence. Some of it sounds like apocalypse fiction. Some of it reads like venture capital pitch decks. And some of it comes from people who've clearly never actually used an AI tool in a real workflow.

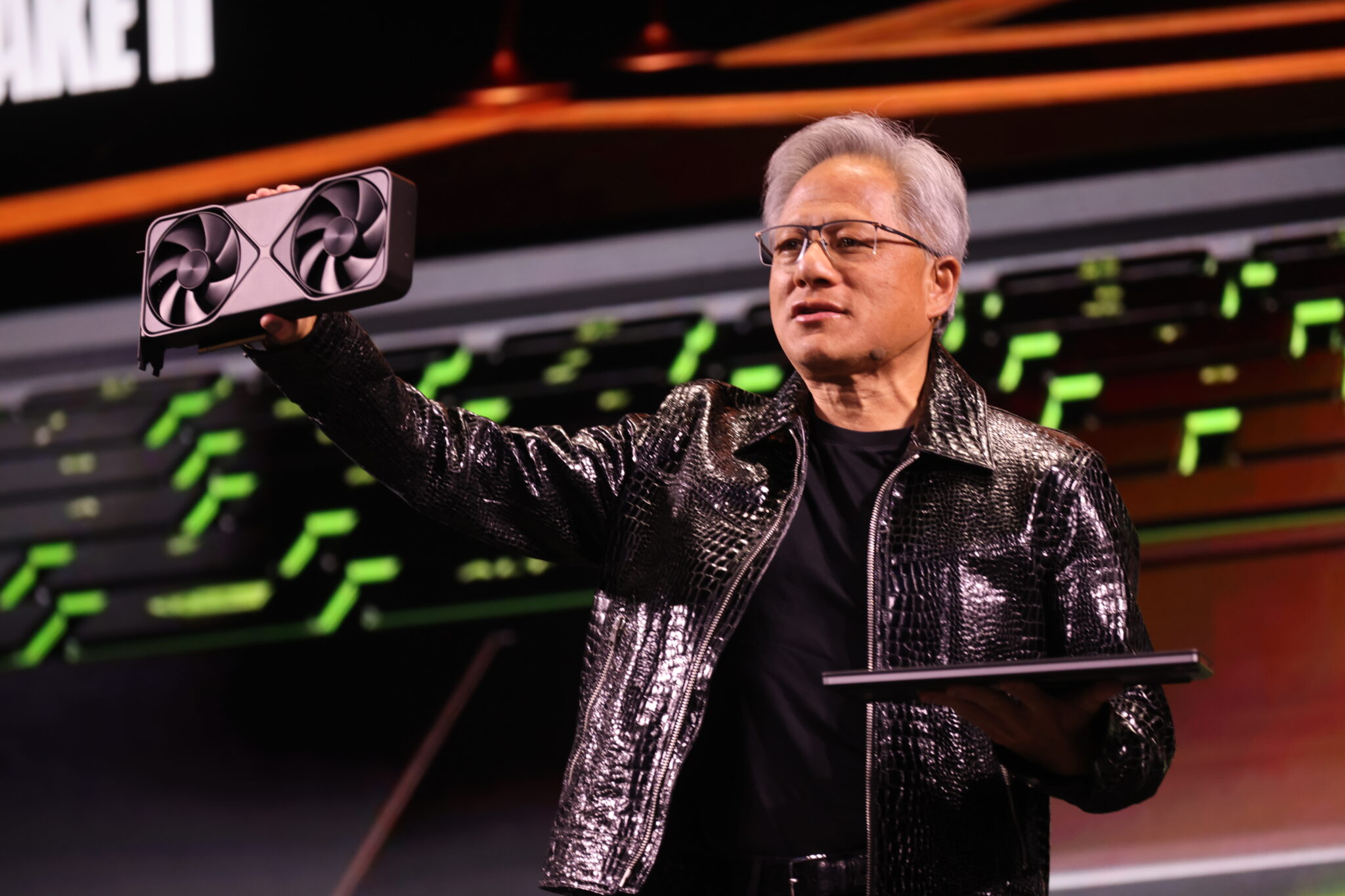

Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia and one of the most powerful voices in AI hardware, is tired of the doomsday talk. He's basically saying what a lot of technologists think but are afraid to say out loud: the obsession with "god AI" as an existential threat is not just wrong, it's actively harmful to progress.

Here's the thing. Huang isn't dismissing AI risks entirely. He's not saying we should throw caution to the wind. What he's doing is drawing a hard line between realistic threats and science fiction scenarios that probably won't happen in our lifetime. And frankly, he's right.

This distinction matters. It matters for how we regulate AI. It matters for how we think about job displacement. It matters for how we allocate resources in tech. And it matters for how workers should actually be thinking about their careers in an AI-augmented world.

Let's unpack what Huang's actually saying, why it matters, and what it means for the real world of business and work in 2025 and beyond.

TL; DR

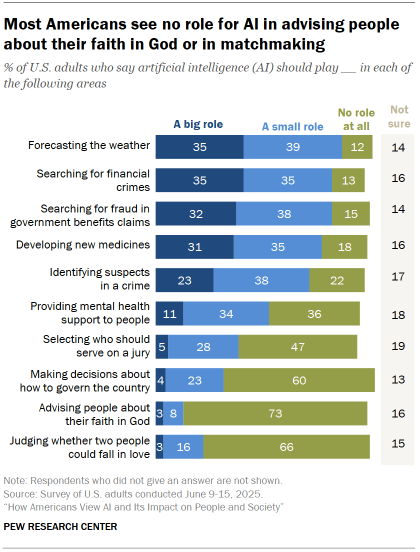

- God-level AI doesn't exist yet: Huang argues researchers currently lack any reasonable ability to create AI that fully understands language, molecular structures, proteins, or physics comprehensively. This system sits decades away, not around the corner, as noted in Windows Central.

- Fear narratives are actively harmful: The "doomer" narrative around AI has been "extremely hurtful" to the industry and society, preventing realistic conversations about actual benefits and challenges, as highlighted by Tom's Hardware.

- AI as productivity tool, not replacement: The focus should shift from existential fears to practical applications where AI enhances human capability. Huang frames AI as a complement that increases worker output, not a wholesale job eliminator.

- Real-world applications matter: AI and robots addressing labor shortages, automating repetitive tasks, and augmenting human decision-making are the actual near-term value drivers, not apocalyptic scenarios.

- The competitive advantage is real: Workers who use AI effectively will outperform those who don't. The job loss risk comes from human competition with AI users, not from AI itself becoming sentient or omniscient.

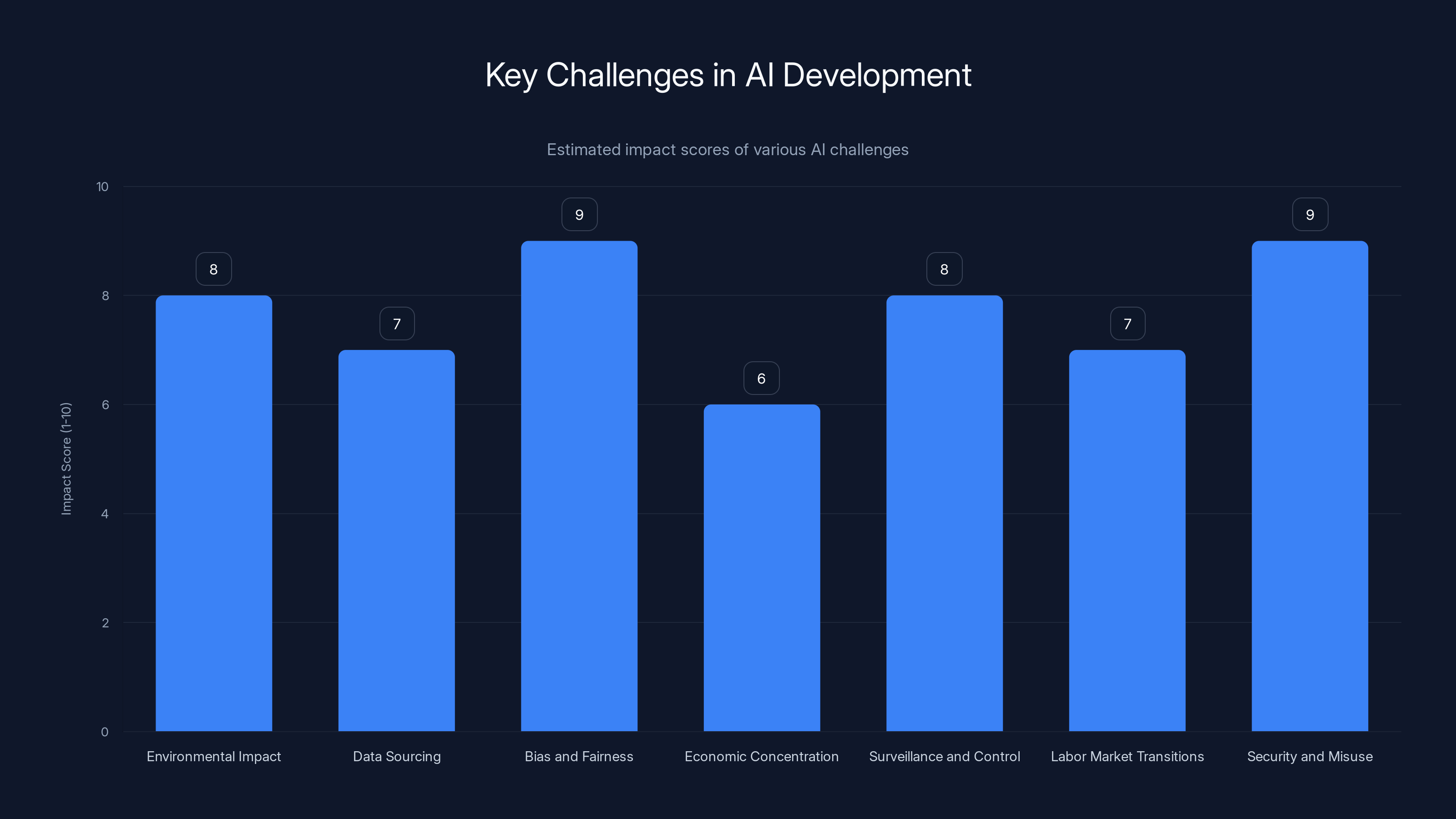

This chart estimates the impact of various AI challenges, highlighting bias and security as the most critical issues. Estimated data.

The God AI Fantasy: What Huang Actually Means

When Huang says researchers have no reasonable ability to create "god AI," he's being very specific. He's not talking about incremental improvements to language models. He's not talking about AI systems that get better at coding, writing, analysis, or creative work.

He's talking about an artificial general intelligence (AGI) system that would fully understand everything: human language at complete semantic depth, molecular structures and biological systems, protein folding and genetics, physics at every scale from quantum to cosmic. A system with genuine reasoning, not just pattern matching. A system that doesn't need retraining every time the world changes. A system that can solve problems no human has ever attempted before.

That system doesn't exist. And the consensus among actual researchers in the field is that we're still probably decades away from even getting close, as discussed in Axios.

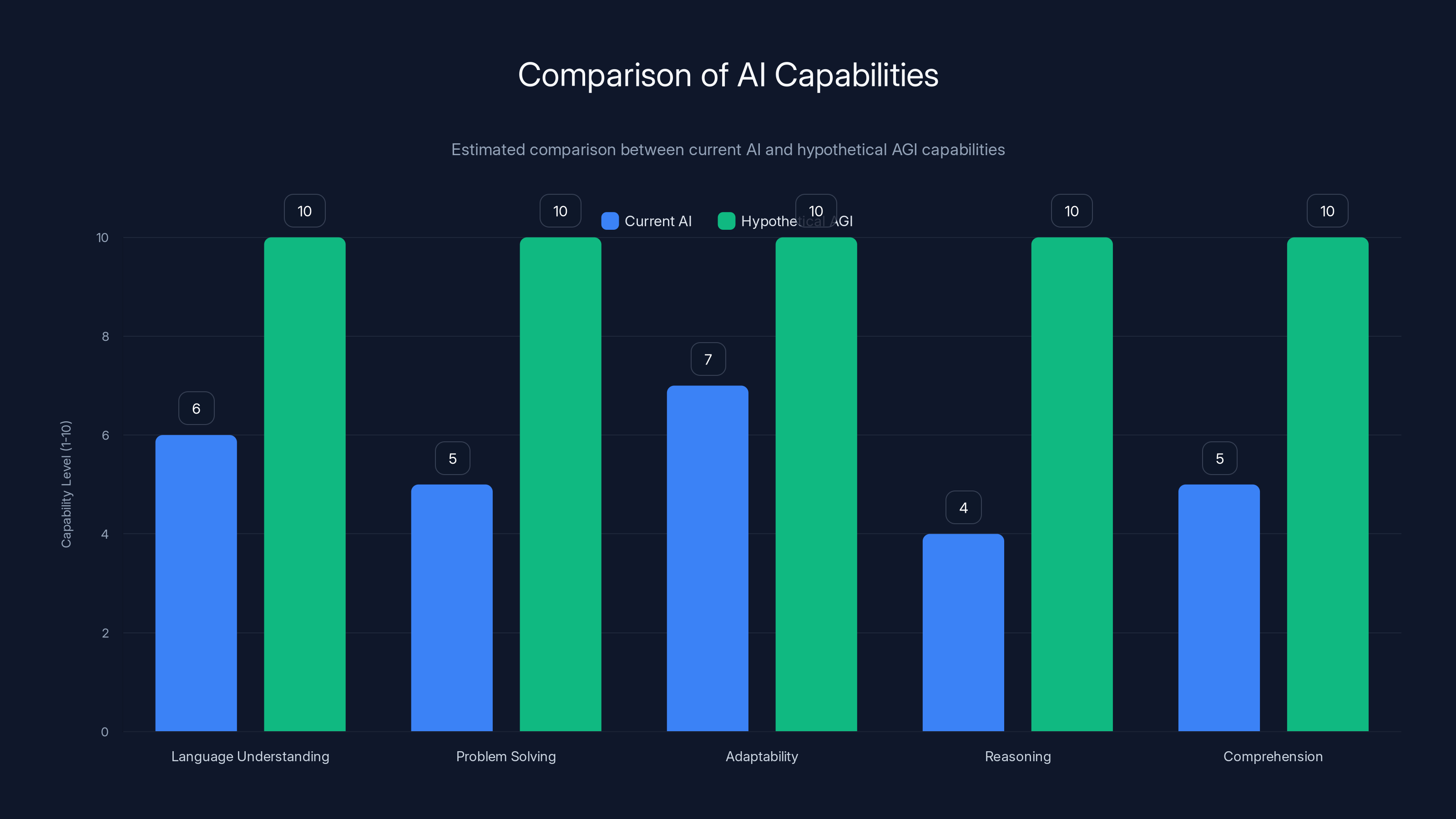

The Difference Between Current AI and True AGI

This is crucial because it's where a lot of mainstream anxiety starts. Current AI models are incredibly sophisticated pattern-matching systems. They're trained on massive amounts of text, code, and other data. They're great at predicting what comes next in a sequence. They're excellent at adapting to new contexts with a little guidance. But they're not reasoning about the world in the way humans do.

Take language understanding. Current large language models can process text at scale and generate coherent responses. But do they actually understand meaning? Probably not in the way philosophers mean. They're extrapolating patterns. They're remixing training data in clever ways. They're not comprehending language the way a human reader comprehends a novel.

Same with knowledge of physics. A current AI can be trained on physics papers and can sometimes generate insights that surprise researchers. But it doesn't have intuitive physical understanding. It doesn't have the embodied knowledge that comes from living in a physical world, from bumping into things, from gravity literally affecting every moment of your existence.

Why God AI Matters for This Conversation

The reason Huang keeps emphasizing the non-existence of god AI is simple: it's the premise behind most of the fear narratives. The stories people tell about AI destroying humanity all depend on a superintelligent system that either gains autonomy or is deliberately built to maximize some objective without ethical constraints.

But if that system is technically infeasible for decades, that changes the conversation entirely. It means we're not actually facing an existential crisis right now. We're facing a different set of challenges: job displacement, concentration of power, misuse of AI tools, bias in training data, environmental costs of training massive models.

These are serious problems worth thinking about. But they're not "AI becomes god and makes humanity extinct" problems.

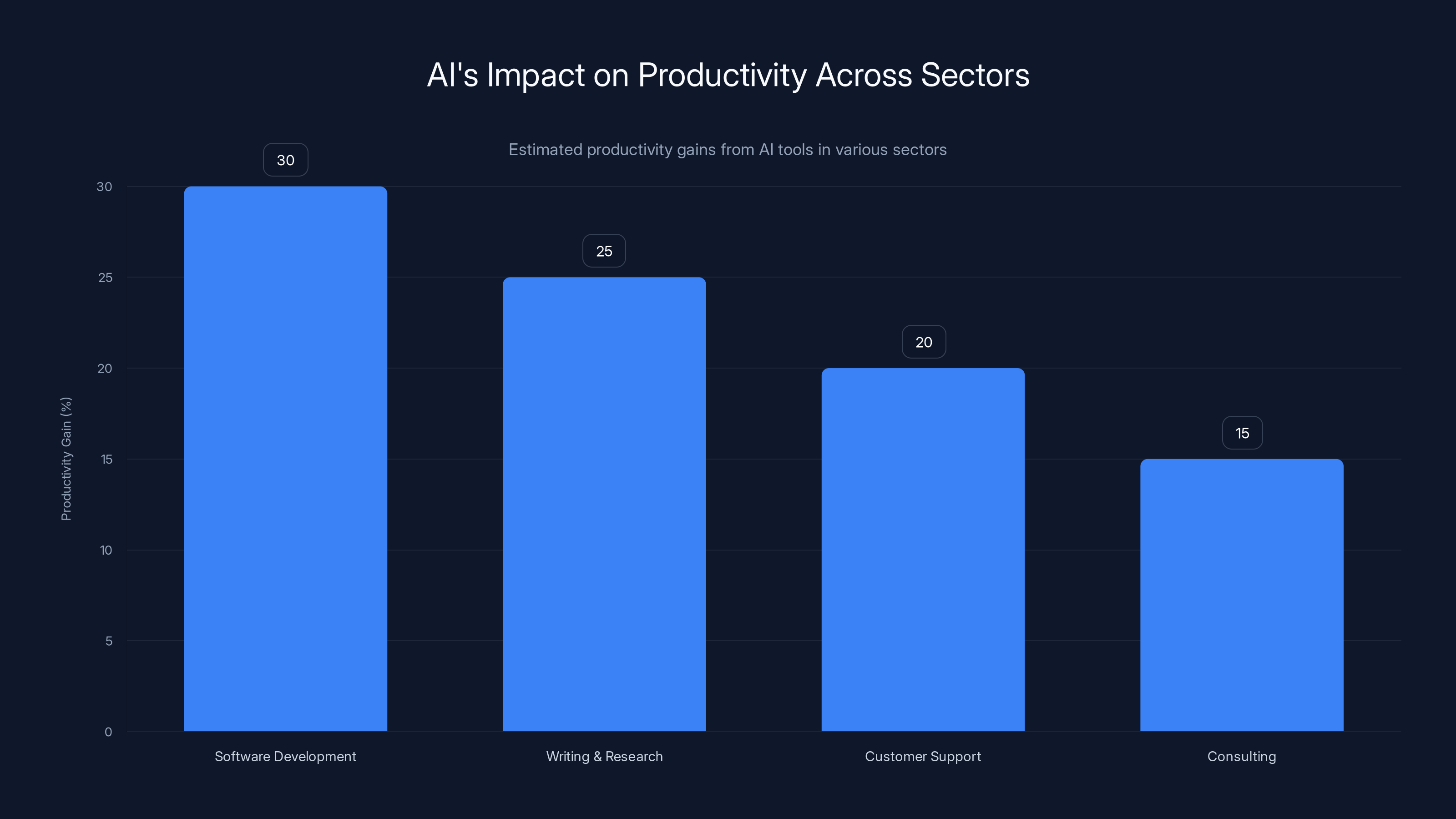

AI tools are estimated to boost productivity by 15-30% across key sectors, highlighting their role in enhancing human capability. Estimated data.

Why the "Doomer" Narrative Actually Hurts

Huang's frustration with doomsayers comes from a pragmatic place. When influential people on social media or in media consistently frame AI as an existential threat, it creates real consequences in the real world.

First, it distorts policy conversations. Governments and regulatory bodies start treating speculative risks as immediate threats. They allocate resources to prevent hypothetical problems while ignoring actual, measurable harms happening right now. This is like spending billions on asteroid defense while ignoring climate change.

Second, it creates a "cry wolf" effect. When people hear constantly about AI destroying humanity and nothing catastrophic happens, they eventually stop listening. The boy who cried wolf problem is real, and it means when you actually do face a legitimate AI-related crisis, fewer people take it seriously.

Third, it discourages talented people from working on AI safety and beneficial AI applications. If the prevailing narrative is that AI is inherently dangerous, why would a young researcher dedicate years to making AI better and safer? Some do anyway, of course. But the narrative matters for talent flows and where resources flow.

The Opportunity Cost of Fear

There's also an opportunity cost to the doomer narrative. While everyone's panicking about god AI, actual progress in practical AI applications gets less attention. The fact that AI can help radiologists interpret scans more accurately, or that it can help researchers find new drugs faster, or that it can help small businesses automate repetitive work, these stories get buried under apocalyptic hypotheticals.

This is especially harmful in developing countries. If you're running a healthcare system in a region with limited radiologists, an AI tool that makes the existing radiologists more effective could be transformative. But if the prevailing narrative is that AI is too dangerous to use, that opportunity gets delayed.

The Real Conversation: AI as Productivity Enhancement

Huang's actual point about AI is simpler and more grounded. AI should be evaluated primarily on its ability to enhance human productivity. Can it help people do their jobs better? Can it automate tedious work? Can it free humans up for more creative or strategic thinking?

On these measures, current AI tools are already making a measurable difference. Developers using AI assistants write code faster. Writers using AI for research and outlining save hours on routine work. Customer service teams using AI to triage tickets handle more inquiries with the same headcount.

Are these revolutionary changes? Not necessarily. Are they significant enough that a worker who ignores them is at a competitive disadvantage? Absolutely.

The "You'll Lose Your Job to Someone Who Uses AI" Problem

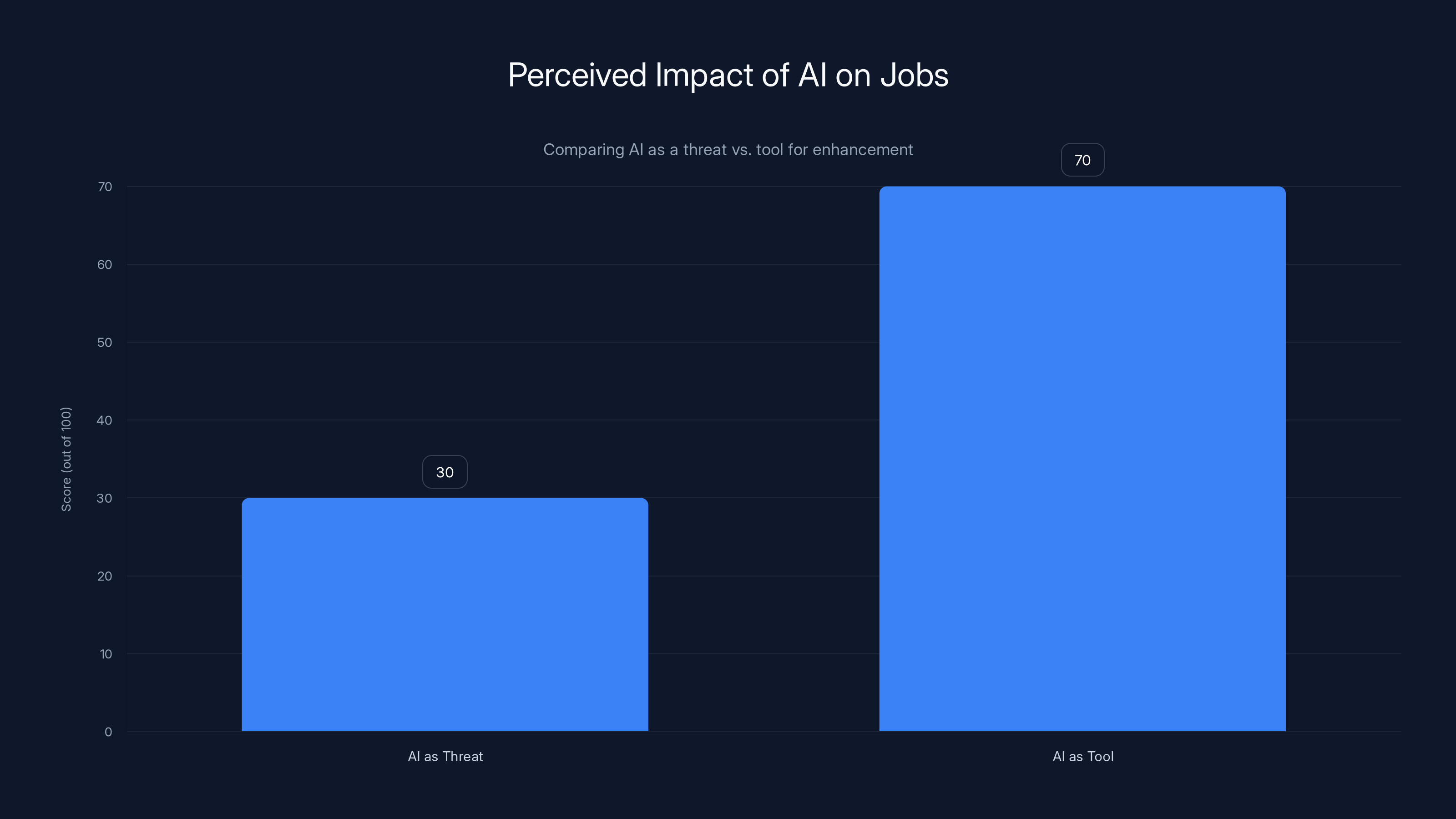

Huang made a statement that's worth sitting with: "You're not going to lose your job to AI. You're going to lose your job to someone who uses AI."

This is different from saying "AI will eliminate your job." It's saying the real competitive threat is other people who adopt AI tools effectively. If you're a consultant and your competitor is using AI to research faster and write proposals quicker, you're at a disadvantage. That's not because AI is sentient or omniscient. It's because AI tools amplify human capability, as highlighted by Benzinga.

This has happened before in technology. When spreadsheets arrived, accountants who learned Excel weren't replaced by spreadsheets. They became more productive. Accountants who refused to learn Excel became unemployable. It was the adoption gap that mattered, not the technology itself.

Where AI Actually Adds Value Today

Look at the sectors where AI is making real differences:

Software development: Code completion and generation tools mean experienced developers can write more code faster. Junior developers can learn faster by reading AI-generated examples. The productivity multiplier is real.

Customer support: AI-powered triage, template generation, and escalation rules mean support teams handle more tickets without becoming overwhelmed. The quality might even improve because humans focus on complex issues.

Research and analysis: Researchers using AI for literature reviews and data synthesis move faster. The AI isn't doing the research. It's handling the grunt work that precedes research.

Content and creative work: Marketers using AI for drafting, outlining, and iterations produce more content. Publishers using AI for summarization and metadata generation move faster. Writers who use AI to overcome block produce more finished work.

Legal and compliance: Lawyers using AI for document review handle larger datasets. Compliance teams using AI for pattern detection catch more issues. The human experts still make the judgment calls, but they have better information faster.

In none of these cases is AI replacing human judgment. It's amplifying it. It's handling the parts of the job that don't require expertise or creativity, freeing the human expert for the parts that do.

Estimated data shows current AI excels in pattern matching and adaptability but lacks true reasoning and comprehension compared to hypothetical AGI.

AI and the Labor Shortage: A Different Angle

One of Huang's points that doesn't get enough attention is how AI could address labor shortages. He frames AI (and robots) as "AI immigrants"—tools that supplement labor in sectors where workers are hard to find, as discussed in Gasgoo.

This is particularly relevant in developed economies facing demographic challenges. Japan has a shrinking working-age population. Europe faces similar pressures. The United States has specific sectors where labor shortages are persistent: agriculture, manufacturing, healthcare, childcare.

In these contexts, AI and automation aren't about replacing people. They're about increasing output with available workers. If you have 100 nurses and patient demand is high, AI tools that help nurses work more efficiently means more patient capacity without hiring 20 more nurses.

Why This Reframing Matters

The traditional "robots steal jobs" narrative assumes that labor is the constraint. But in an aging society with low birthrates, labor is actually the resource. You're not trying to reduce the number of workers. You're trying to make available workers more productive.

This is why Huang's framing is smarter than the usual tech industry narrative. He's not arguing AI is unambiguously good or that it doesn't displace anyone ever. He's saying that in the real economic context many developed nations face, AI is more likely to be a tool for dealing with labor shortage than a tool for mass unemployment.

That doesn't mean there's no displacement. It means the displacement is smaller than some fear scenarios suggest, and it happens in a context where labor is valuable.

The Question of Job Displacement: What Actually Happens

Now, let's be honest. Some jobs will change. Some roles will shrink. Technology always does this. The printing press didn't need as many scribes. Cars didn't need as many horse breeders. Spreadsheets didn't need as many clerical accountants.

But here's what happened in those cases: New jobs emerged in different sectors. People retrained. The economy adapted. Sometimes the adaptation was painful for individuals in the disrupted sectors. But the net result over decades was usually positive employment and higher living standards.

The question for AI is whether this pattern continues. Will new jobs emerge that use AI-augmented workers, that create entirely new roles, that leverage the productivity gains AI provides?

Historically, the answer has been yes. And there's no obvious reason why this would change. AI doesn't eliminate the need for human judgment, creativity, or problem-solving. It changes what problems humans need to focus on.

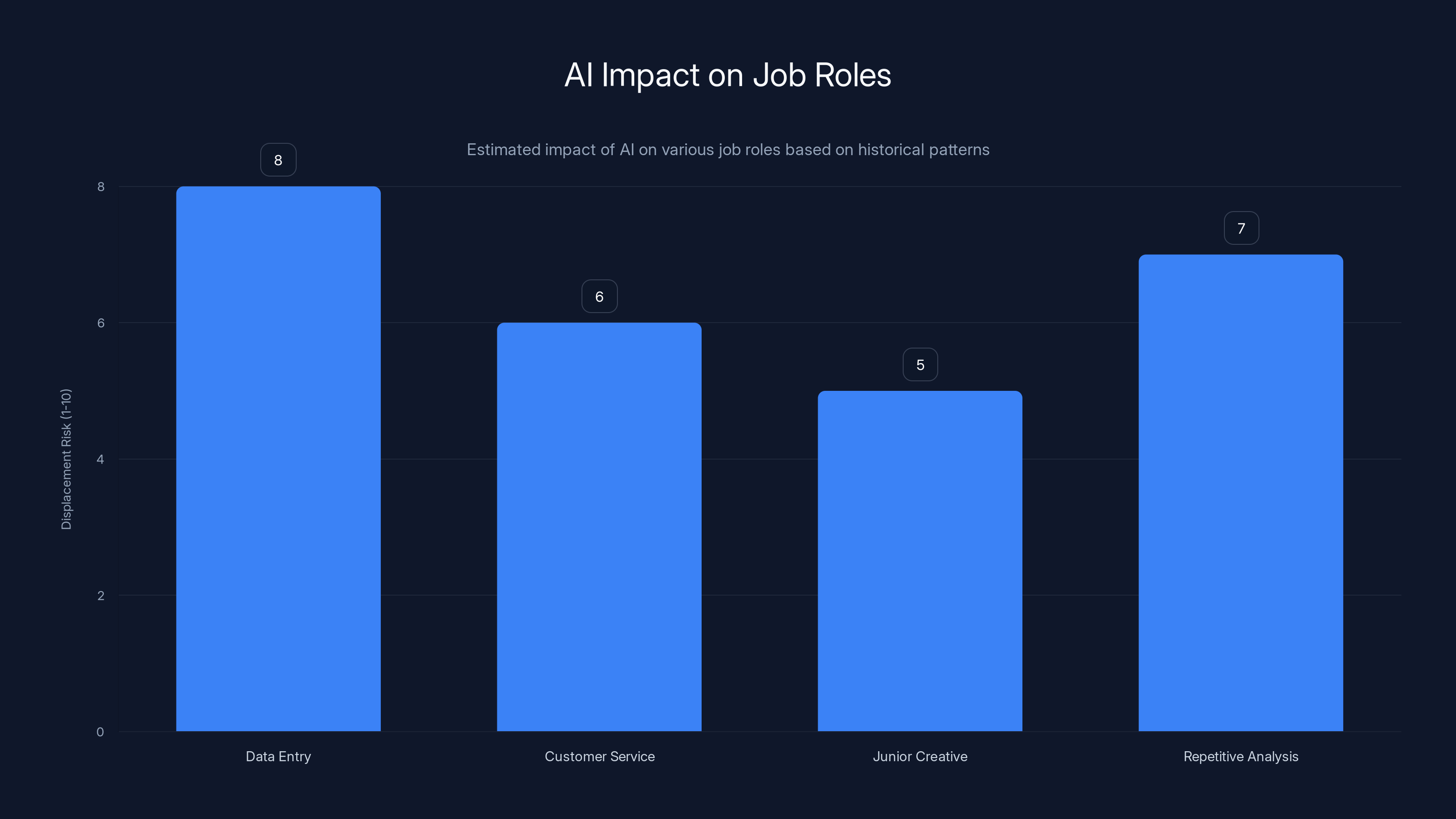

Where Displacement Might Be Real

There are some roles where AI might have a more direct substitution effect:

Routine data entry and processing: AI can already do much of this. This is a real displacement risk for people in data processing roles. The mitigation is retraining in higher-value work.

Certain customer service interactions: Basic customer service queries (tracking, billing, FAQs) are increasingly handled by AI. More complex support remains human. But there's real change in the mix.

Junior-level creative work: Junior copywriters, junior designers, junior researchers doing routine literature reviews—AI can do parts of this. This could shrink junior roles or change their nature significantly.

Repetitive analysis: Analysts doing routine report generation, data visualization, basic pattern detection—this is vulnerable to AI automation.

But in all these cases, the displacement is partial, not total. And it's happening gradually, not overnight. This gives people and organizations time to adapt.

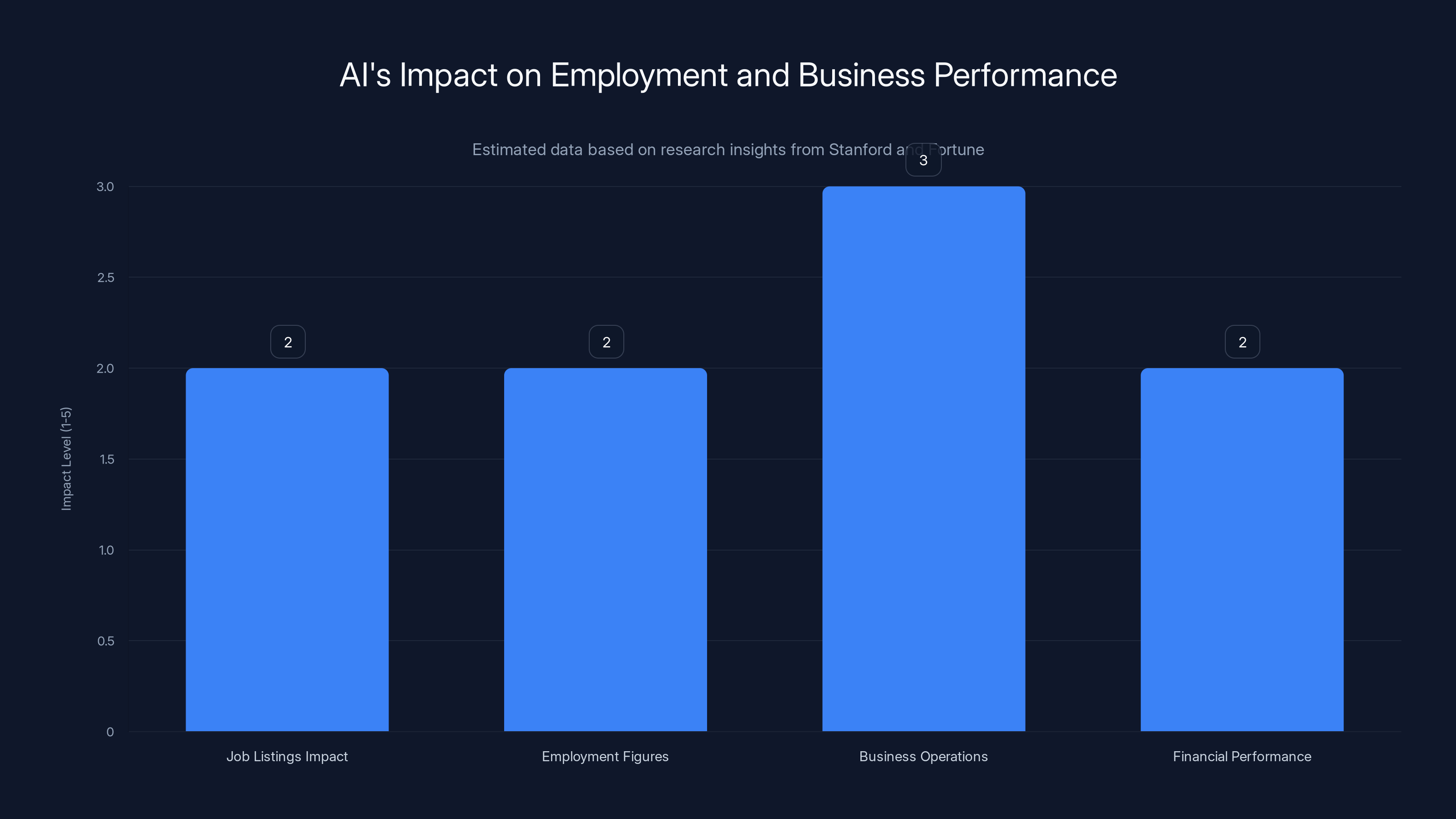

AI's impact on job listings, employment, business operations, and financial performance is modest, with incremental productivity gains rather than transformative changes. (Estimated data)

What Research Actually Shows About AI's Impact So Far

Here's something important that doesn't get emphasized enough: We have data on AI's impact to date, and it's modest.

Stanford University research has tracked job postings and employment trends through the AI boom. What they found: AI has had limited measurable impact on job listings and employment figures over the past few years. Some sectors show changes, but nothing like mass unemployment. Some sectors show hiring increases.

Similarly, Fortune's analysis of AI adoption and business performance has found that many AI tools have produced limited measurable effect on business operations or financial performance. Companies invest in AI, but often the ROI is hard to demonstrate. This suggests that either AI implementations are still figuring out best practices, or the productivity gains are real but incremental, not revolutionary.

This is actually the argument Huang is making indirectly. Real AI progress is incremental productivity gains, not transformative disruption. Which sounds less exciting than the sci-fi narratives, but is probably more accurate.

The Hype-Reality Gap

There's always a gap between the hype around a technology and its actual impact. The internet was supposed to revolutionize every human institution within a decade. It did eventually, but on a 20-30 year timeline, not overnight. Same with AI. The real impact will be substantial, but it'll be measured in productivity improvements, not job elimination events.

The Case Against Intentional Superintelligence

One of Huang's most interesting points is his explicit opposition to the idea of a single, powerful god AI existing at all. He's not just saying it won't happen. He's saying it shouldn't happen.

This is important because some of the AI narrative assumes that superintelligence is inevitable and the question is just how to control it. Huang's saying: maybe the goal shouldn't be superintelligence at all. Maybe distributed intelligence, systems with different capabilities, narrow AIs that are very good at specific things—maybe that's actually better than a single omniscient system.

Why Centralized AI Power Is Dangerous

Think about what a god AI controlled by one company, one nation, or even one international body would mean. Whoever controls that system controls enormous power. They control the basis for most important decisions. They have leverage over every other player in the world.

Historically, power concentration at that scale hasn't gone well. Huang's point—that a single superintelligent system controlled by a single entity would be "super unhelpful"—is putting it mildly. It would be dangerous.

But a world with many different AI systems, each good at specific domains, each with different values and priorities embedded in them—that's a very different power dynamic. It's more distributed. It's more resilient to a single point of failure. It's harder to weaponize.

So Huang's argument isn't just that god AI is technically infeasible. It's that we shouldn't want it to exist even if we could build it.

AI is estimated to have the highest displacement risk in data entry roles, followed by repetitive analysis. Customer service and junior creative roles face moderate risk. Estimated data.

The Regulatory Implication: Realistic Thinking

Governments and regulators are trying to figure out how to govern AI. Some countries are proposing strict regulations. Some are taking a lighter touch. All of them are doing it somewhat in the dark because the technology is changing rapidly and nobody's entirely sure what risks are real versus theoretical.

Huang's argument suggests that regulatory focus should be on actual, measurable harms and realistic risks, not speculative extinction scenarios. This means:

Focus on near-term harms: Bias in AI systems, privacy violations from data scraping, misuse of AI for surveillance or manipulation. These are happening now.

Address labor transition issues: If AI is going to displace certain types of work (and it will, gradually), policy should focus on retraining and education so displaced workers can transition.

Encourage distributed development: Rather than trying to prevent superintelligence, encourage diversity in AI development so no single actor dominates.

Require transparency and auditing: As AI becomes more integrated into important decisions, require systems to be auditable, to explain their reasoning, to show their data sources.

Plan for infrastructure impacts: AI training is computationally expensive and energy-intensive. Policy should address electricity and environmental costs.

These are concrete, achievable regulatory goals based on realistic threats rather than speculative ones.

What Companies Are Actually Getting Wrong About AI Implementation

If you listen to enterprise software companies talk about AI, there's often a gap between the hype and what's actually valuable. Many organizations are adding "AI" to their products because investors expect it, not because it solves real problems.

The companies getting value from AI are typically the ones that:

Identified specific friction points first: Where do humans waste time? Where do decisions require information that's hard to get? Where does humans make mistakes? Start with the problem, then apply AI.

Focused on human-AI collaboration: Rather than trying to fully automate a process, focus on how AI can give humans better information or handle part of a workflow.

Invested in training and change management: An AI tool is only valuable if people actually use it. That requires training, expectation-setting, and often process redesign.

Measured ROI carefully: Not all productivity gains are financial gains. But if you implement AI, define what success looks like before you start.

Companies that treat AI as a magic solution to inefficiency without doing this work usually find that the AI doesn't deliver the expected value.

The Automation Paradox

There's a funny thing that happens when you automate part of a process: sometimes the process becomes more complicated. You have humans doing part of it, AI doing another part, and the handoff between them creates overhead.

The best AI implementations actually simplify overall processes, not just automate parts of them. They eliminate unnecessary steps, reduce the number of decision points, or consolidate what used to be multiple steps into one AI-assisted step.

Companies missing this end up with complicated workflows that are slightly more efficient but harder to understand and maintain.

Estimated data suggests that AI is more often perceived as a tool for enhancement (70%) rather than a threat (30%) to jobs. This aligns with Huang's perspective on AI amplifying human capabilities.

AI as a Tool for Competitive Advantage

Here's the pragmatic take-home for workers and organizations: AI adoption is becoming table stakes. Not implementing it is increasingly equivalent to operating with a handicap.

But the competitive advantage isn't in having the fanciest AI. It's in using AI effectively to solve real problems. Organizations that train their people to use AI, that integrate AI into actual workflows, that measure whether AI is delivering value—those organizations are going to outperform competitors.

Similarly, workers who learn to use AI tools effectively are going to be more productive and more valuable than workers who ignore the tools.

This is true regardless of whether god AI exists or whether AI is an existential threat. Those are interesting philosophical questions. But the practical competitive question is immediate and concrete: Are you using AI to work better?

The Infrastructure Buildout Is the Real Story

Way less attention is paid to this than to AI capabilities, but the actual story over the next decade is going to be infrastructure. Building the data centers, the electricity generation, the manufacturing capacity, the supply chains to support AI development and deployment.

Companies like Meta are building massive data centers powered by nuclear energy. Companies are investing in chip manufacturing. There's a race to control semiconductor supply. Electricity generation is becoming a strategic concern in tech.

This infrastructure buildout is where most of the capital is flowing, and it's a more reliable indicator of where the industry thinks value is than any AI safety debate.

The Geopolitical Dimension

AI and the infrastructure to support it is becoming a geopolitical issue. Countries that can't manufacture advanced semiconductors are at a disadvantage. Countries with reliable, cheap electricity have an advantage. Countries trying to control AI development for safety or strategic reasons are going to struggle if the technology is developed primarily elsewhere.

This is all happening in parallel with Huang's argument about god AI. Whether or not god AI is coming, the infrastructure investment is real, and it's reshaping global power dynamics.

What Gets Lost in the Doomer Narrative

One thing that doesn't get enough attention in AI discussions is all the ways AI is helping in less dramatic contexts.

AI is helping researchers understand protein folding, which could lead to better treatments for Alzheimer's and other degenerative diseases. AI is helping agricultural researchers breed crops that are more drought-resistant. AI is helping radiologists detect cancers earlier. AI is helping teachers personalize instruction for students with different learning styles.

These aren't headline-grabbing stories. Nobody's worried that an AI is going to become superintelligent through cancer detection. But these applications are already improving people's lives, and they'll continue to as the technology improves.

The doomer narrative focuses on what could go wrong so much that it misses what's actually going right. And that skews how people think about AI policy and adoption.

The Honest Assessment: Real Challenges, Not Existential Ones

Now, Huang's not saying there are no legitimate AI challenges. There are. Let's list them honestly:

Environmental impact: Training large models uses enormous amounts of electricity. This has a real carbon cost unless the electricity comes from renewables.

Data sourcing and copyright: AI models are trained on data scraped from the internet, including copyrighted work. The legal and ethical status of this is unresolved.

Bias and fairness: AI systems trained on biased data produce biased outputs. Detecting and correcting this bias is hard.

Economic concentration: The companies that can afford to build massive AI systems are becoming more powerful. This concentration of capability has both good and bad implications.

Surveillance and control: AI could make surveillance more effective and totalitarian control more feasible. This is a real risk that requires policy response.

Labor market transitions: Even if mass unemployment doesn't happen, sectors that depend on jobs that become partially automated will face real disruption. People in those sectors need support.

Security and misuse: AI could be used to create better malware, more effective social engineering attacks, more convincing disinformation. This is already happening.

These are serious challenges. But they're not "superintelligent AI becomes god and destroys humanity" challenges. They're "we need thoughtful policy and careful implementation" challenges.

What Huang Actually Represents

It's worth stepping back and thinking about what Huang actually is in this conversation. He's the CEO of Nvidia, the company that makes the chips that power AI. He's enormously invested in AI adoption. His company makes money when AI gets deployed widely. So when he says AI is good and god AI fears are overblown, you should consider his incentives.

But—and this is important—his track record suggests he's generally straight with people. He's made bold predictions about technology before, and he's been broadly right. He's not trying to hype a product that doesn't work. He's trying to clear out the noise so the actual value of AI can be understood.

His argument is also consistent with what developers and organizations who are actually using AI are discovering: the tools are useful but not magical. The productivity gains are real but incremental. The disruption is real but not catastrophic. The risks are real but not existential.

How to Think About AI in Your Career and Business

So here's the practical playbook based on Huang's arguments and what's actually happening in AI:

First, don't panic about existential risk. It's not useful for decision-making. Focus on what's happening in the next 3-5 years.

Second, figure out where AI can reduce friction in your work. What takes a lot of time but requires no special insight? Can AI handle it? Can AI augment someone's ability to do it?

Third, invest in learning how to use AI tools well. This is becoming a core skill. You don't need to understand the math. You need to understand what tasks AI is good at and how to get it to actually solve your problem.

Fourth, if you're hiring or managing, understand that your team's AI literacy is going to be a competitive advantage. Train people, give them time to explore tools, measure what works.

Fifth, stay skeptical. A lot of AI implementations are oversold. Measure whether tools actually improve performance or just feel impressive.

Finally, remember that the real competition isn't between you and AI. It's between you and the person across the industry who's using AI effectively. That person is your real threat or your opportunity.

The Future: Boring Progress, Not Explosive Change

If Huang's right—and most people actually working in AI seem to think he is—then the future of AI is less sci-fi and more mundane. It's incremental improvements in capabilities. It's better integration into existing workflows. It's tools that make expert humans more productive. It's applications that are valuable but not revolutionary.

It's not god AI arriving and making all human effort irrelevant. It's not superintelligence emerging from training a bigger model on more data.

It's like how the internet didn't arrive and instantly change everything overnight. It changed things gradually. It created new opportunities and disrupted old ones. It made some jobs obsolete and created new jobs. Gradually, then all at once, the world was different.

AI will probably follow a similar arc. In 2035, we'll look back and be amazed at how different work and productivity are. Not because god AI arrived, but because countless AI tools became integrated into how we work, and it all added up to a fundamental shift.

That shift is real. The threat from doomsaying about it is also real. Huang's pushing back against the latter so people can focus on the former.

FAQ

What does Jensen Huang mean by "god AI"?

Huang uses "god AI" to describe a hypothetical artificial general intelligence (AGI) that would fully understand human language, molecular structures, protein sequences, physics, and essentially everything. This system would have genuine reasoning capabilities and could solve any problem presented to it. Huang's core point is that this level of AI doesn't exist today and researchers have no reasonable ability to create it in the foreseeable future, making it a poor focus for policy and public concern.

Why does Jensen Huang say doomsday narratives are harmful?

Huang argues that exaggerated fear narratives about AI have been "extremely hurtful" to both the industry and society because they distort policy conversations, create a "cry wolf" effect that eventually dulls people's response to real risks, and discourage talented researchers from working on beneficial AI applications. When people are panicked about extinction-level scenarios that won't happen, they ignore real, measurable harms happening today like bias in algorithms, privacy violations, and labor displacement in specific sectors. This misallocation of attention and resources prevents productive discussion about actual AI governance needs.

How does Huang suggest we should think about AI and job loss?

Huang reframes the job loss concern by saying: "You're not going to lose your job to AI. You're going to lose your job to someone who uses AI." This shifts the focus from AI as an autonomous threat to human capability amplification. He suggests that the real competitive pressure comes from people who adopt AI tools effectively, not from AI itself. This is similar to how spreadsheet adoption changed accounting work—accountants who learned Excel became more productive, while those who didn't became obsolete. The risk isn't replacement but competitive disadvantage among workers.

What are some real-world applications where AI is currently adding value?

According to the broader context of Huang's arguments, AI is proving valuable in sectors like software development (code generation and completion), customer support (triage and template generation), research and analysis (literature review and data synthesis), legal work (document review and pattern detection), and healthcare (radiologist augmentation and research acceleration). In each case, AI handles routine, data-intensive, or pattern-matching tasks while humans focus on judgment, creativity, and complex problem-solving. The value is in productivity amplification, not autonomous action.

How should organizations approach AI implementation to actually get value?

Based on Huang's practical emphasis, organizations should start by identifying specific friction points where humans waste time or where decisions need better information. Rather than trying to fully automate processes, focus on human-AI collaboration. Invest in training and change management because AI tools are only valuable if people use them. Measure ROI carefully before and after implementation, and be willing to walk away from AI solutions that don't deliver concrete benefits. Many organizations add AI features because investors expect it, not because they solve real problems—this approach usually fails to deliver actual value.

What does Huang think about the concentration of AI power?

Huang explicitly opposes the idea of a single, centralized god AI controlled by one company, nation, or entity. He argues this would be "super unhelpful" because it would concentrate enormous power in a single actor. Instead, he seems to favor a future with distributed AI capabilities—multiple systems, each good at specific domains, with different values and priorities. This decentralized approach is more resilient to single points of failure and less vulnerable to weaponization or authoritarian control than a world with one omniscient AI system.

What should policymakers focus on regarding AI, according to Huang's perspective?

Instead of focusing on speculative superintelligence scenarios, Huang's arguments suggest policymakers should address concrete, measurable harms: bias and fairness in algorithms, privacy violations from data scraping, labor transition support, environmental impact of training large models, surveillance risks, security vulnerabilities, and encouraging distributed AI development rather than concentration of capability. These are near-term challenges that require thoughtful regulation today, unlike god AI which is probably decades away and may never be feasible at all.

Conclusion: Practical Progress Over Apocalyptic Speculation

Jensen Huang's push back against doomer narratives is fundamentally grounded in pragmatism. It's not that he thinks AI is insignificant or that there are no legitimate challenges. It's that he thinks we're having the wrong conversation.

We're focused on whether superintelligent AI will emerge and destroy humanity. Meanwhile, actual AI tools are in production systems right now, making radiologists more accurate, helping developers ship code faster, augmenting researchers, automating tedious work. The real story is happening in the present, not in speculative futures.

The doomer focus also prevents productive policy discussion. If you're worried about superintelligence arriving in 2027, you won't focus on how to retrain workers in sectors where AI is automating specific job types. If you're terrified of god AI, you won't invest in making sure AI systems are fair and unbiased. If you're panicking about extinction, you won't build reasonable, practical safeguards against misuse.

What Huang is essentially saying is: Let's deal with the real challenges in front of us, implement AI thoughtfully, measure whether it's actually improving things, train people to use it effectively, and address the concrete harms we're already seeing. And let's stop freaking out about scenarios that are probably technically infeasible anyway.

That's not downplaying AI's impact. It's actually the opposite—it's taking AI seriously as a technology that will reshape work and society, while being realistic about the timeline and nature of that reshaping.

The next five years are going to be interesting. Organizations that implement AI thoughtfully, workers who learn to use AI tools, and policymakers who focus on real problems rather than hypothetical ones will be in much better positions than those waiting for god AI or catastrophic job loss. Neither probably arrive the way people expect. But the incremental, unglamorous progress of practical AI adoption almost certainly will.

That's the real story. That's what deserves attention. And that's what Huang's really trying to say underneath the "don't be a doomer" messaging.

The AI transition is coming. It's not apocalyptic. It's not magical. It's just... practical. And that's actually more important to understand than any science fiction scenario, however much more dramatic that fiction might be.

Key Takeaways

- God-level AI that fully understands everything doesn't exist and researchers lack any reasonable ability to create it in the foreseeable future

- The real competitive threat isn't AI replacing humans—it's other workers using AI effectively to outperform non-users

- Current AI adds value through productivity amplification in specific domains like software development, customer support, and research—not through autonomous action

- Doomsday narratives about AI are actively harmful because they distort policy focus away from real, measurable challenges happening today

- Labor shortages in developed nations mean AI is more likely to supplement workers than replace them, contrary to mass unemployment fears

- Infrastructure investment in data centers and semiconductors is a more reliable indicator of actual AI impact than safety debates about superintelligence

Related Articles

- AI-Powered Go-To-Market Strategy: 5 Lessons From Enterprise Transformation [2025]

- Parloa's $3B Valuation: AI Customer Service Revolution 2025

- Google Gemini vs OpenAI: Who's Winning the AI Race in 2025?

- AI Companies & US Military: How Corporate Values Shifted [2025]

- Shadow AI in 2025: Enterprise Control Crisis & Solutions

- Apple & Google AI Partnership: Why This Changes Everything [2025]

![Jensen Huang's Reality Check on AI: Why Practical Progress Matters More Than God AI Fears [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/jensen-huang-s-reality-check-on-ai-why-practical-progress-ma/image-1-1768514815974.jpg)