Laurie Spiegel on Algorithmic Music vs AI: The 40-Year Evolution [2025]

When most people hear "AI music," they picture neural networks trained on millions of songs, churning out endless variations. But that's not what Laurie Spiegel has been doing for nearly five decades.

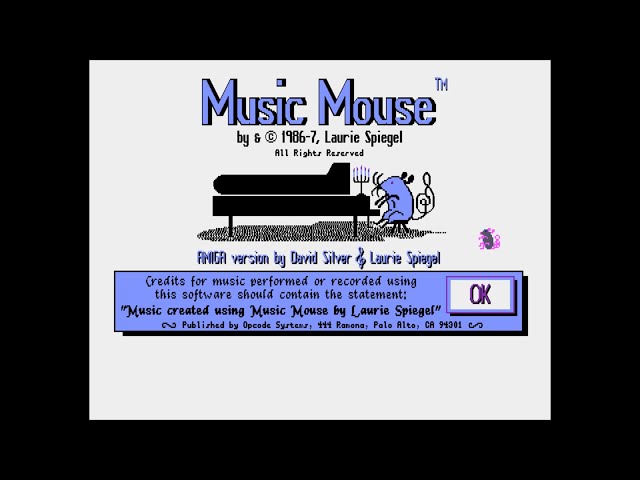

In 1986, she created Music Mouse—a deceptively simple tool that transformed how composers could work. You moved your mouse around on a grid. Notes played. That was it. No machine learning. No neural networks predicting what comes next. Just pure algorithmic composition.

Today, as Music Mouse celebrates its 40th anniversary with a modern revival, Spiegel is more vocal than ever about the distinction between algorithmic music and what people casually call "AI music." And she's right to push back. The difference isn't semantic. It's fundamental.

This article digs into that difference, traces the origins of algorithmic composition, and explains why this distinction matters as AI floods the music world. We'll explore what made Music Mouse revolutionary, why Spiegel's approach still resonates today, and what algorithmic composition can teach us about creativity, control, and the future of music.

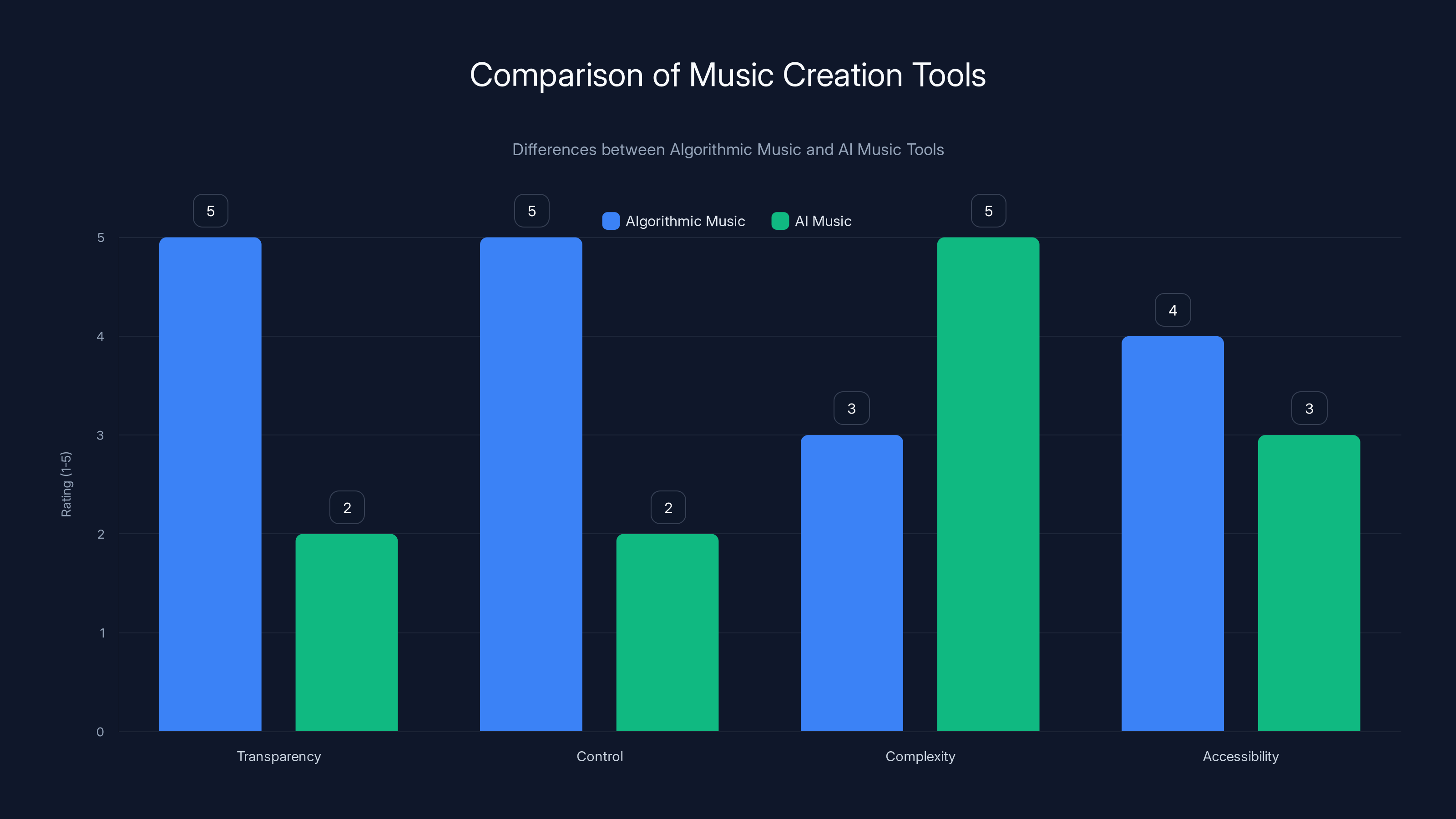

Before diving in, here's the core idea: algorithmic music uses predetermined rules and mathematical patterns that the artist understands and controls. AI music uses probabilistic models trained on data. The artist doesn't fully understand why the AI makes the choices it does. That gap between transparency and mystery—between intention and statistical inference—is where the entire conversation lives.

TL; DR

- Algorithmic music uses transparent, human-designed rules while AI music relies on learned patterns from training data that artists don't fully control or understand

- Laurie Spiegel's Music Mouse democratized algorithmic composition by making it accessible to anyone with a computer, no music theory required

- The distinction matters legally and artistically because algorithmic music preserves authorial intent while AI-generated music raises questions about copyright and creative ownership

- Modern algorithmic tools are experiencing a resurgence as artists tire of black-box AI solutions and seek transparent, controllable creative processes

- The future likely involves both approaches coexisting, with artists choosing tools based on whether they value predictability and control or generative exploration

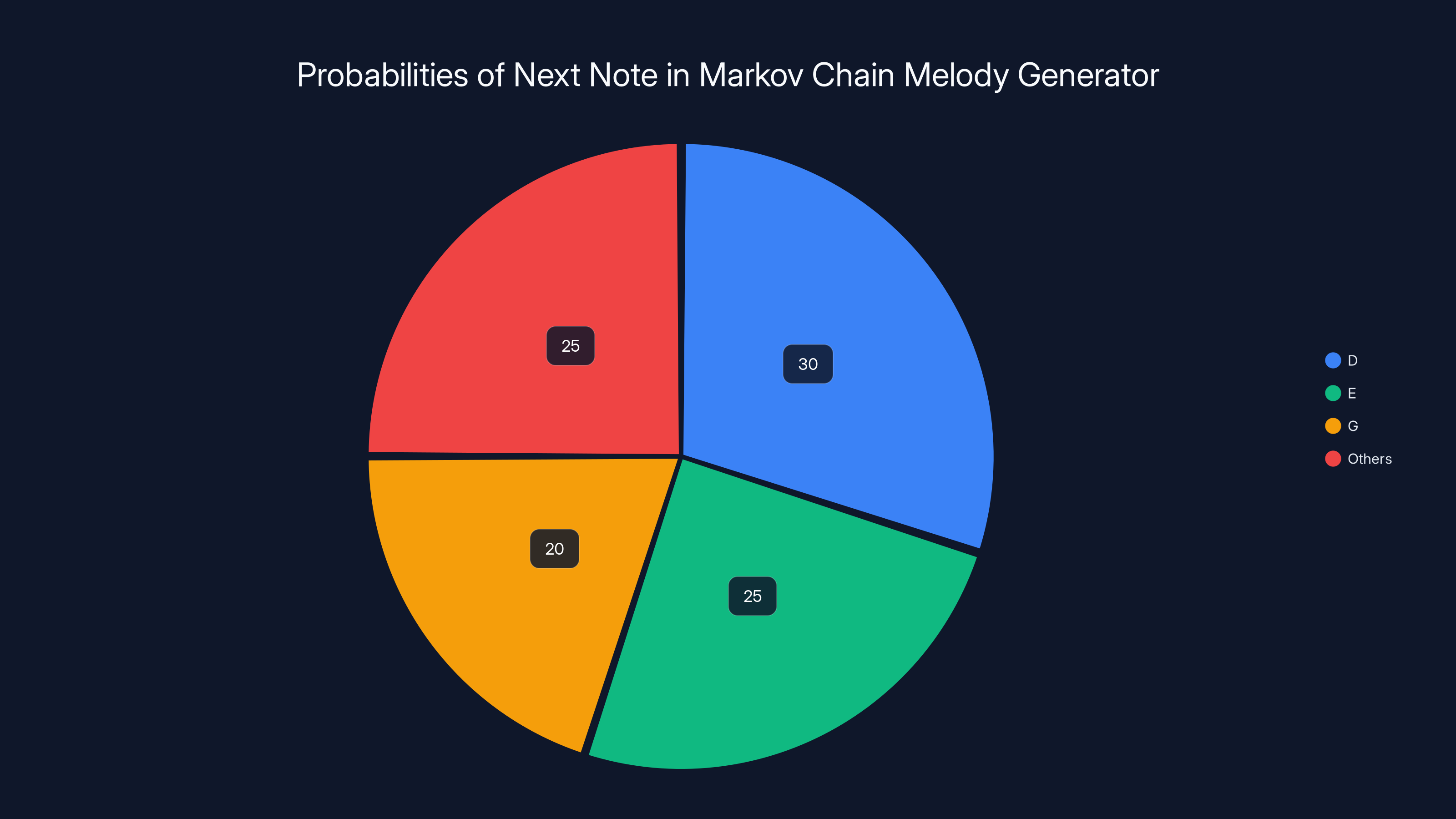

In a Markov chain melody generator, after note C, the next note is most likely D (30%), followed by E (25%) and G (20%). Estimated data based on typical patterns.

Who Is Laurie Spiegel and Why Does She Matter?

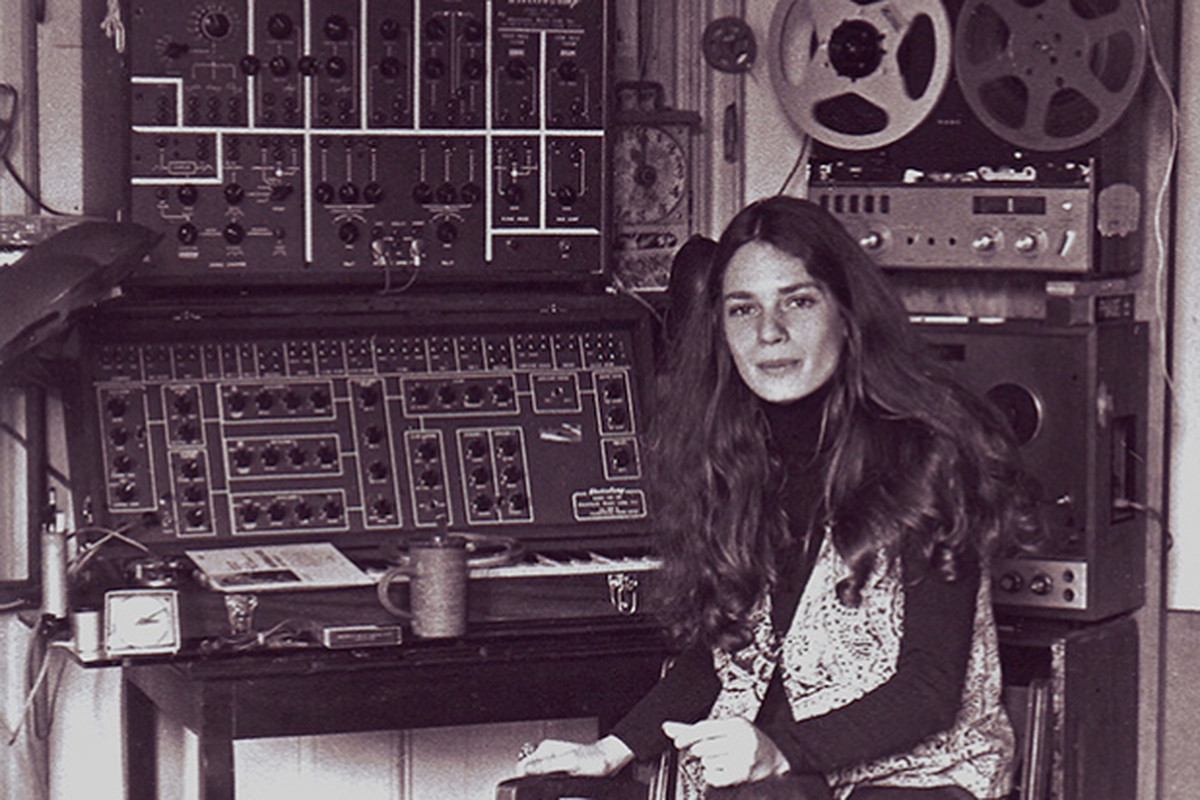

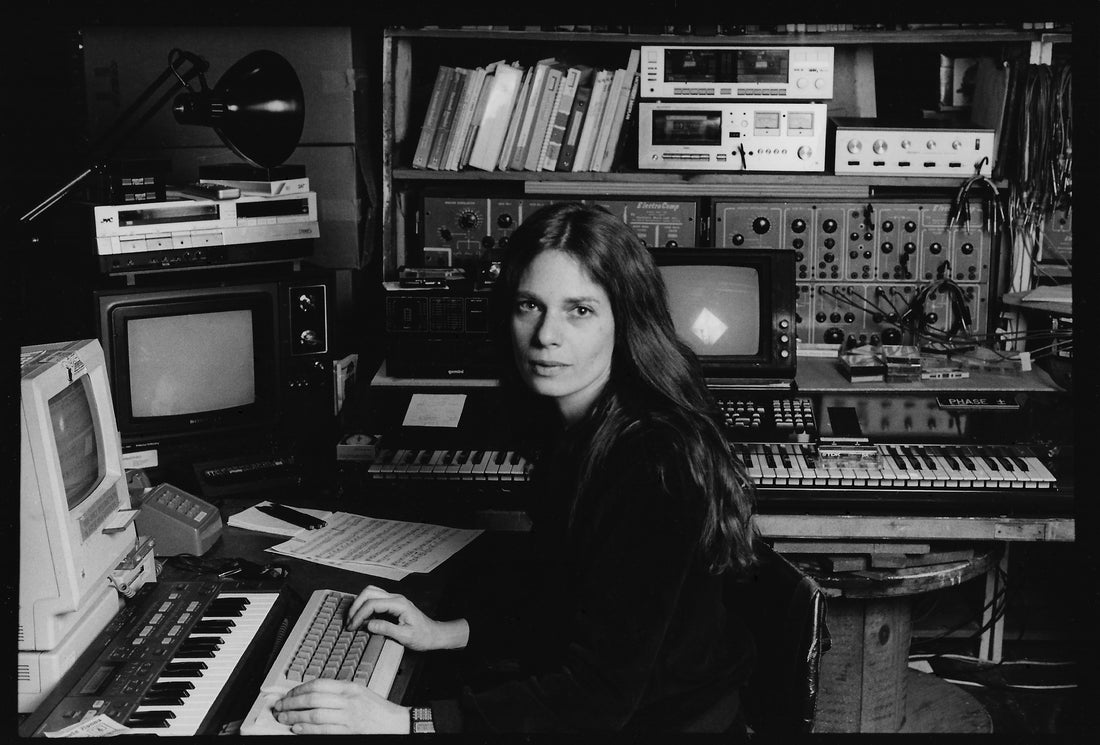

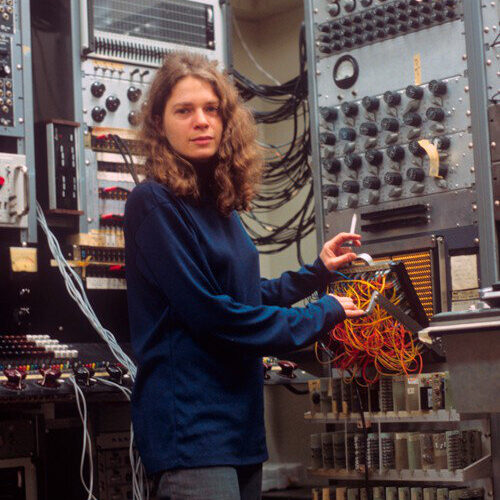

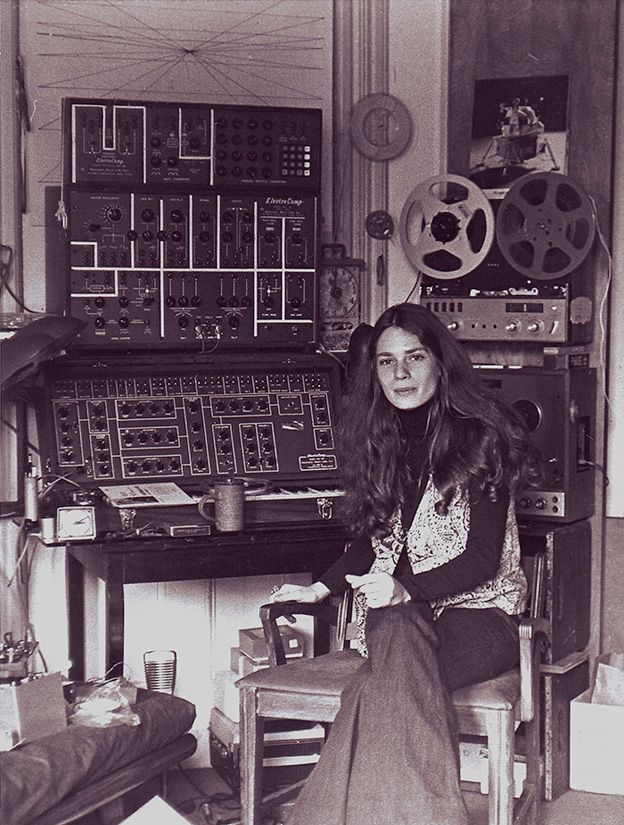

Laurie Spiegel isn't just a composer who dabbled in computers. She's been at the absolute forefront of computer music since the early 1970s, when most musicians still thought synthesizers were novelties.

In 1973, she joined Bell Labs—arguably the most important research institution of the 20th century. While most people associate Bell Labs with transistors and telecommunications, it was also a haven for experimental musicians and sound artists. This is where Spiegel dove deep into digital synthesis, worked on early computer graphics systems, and started thinking about how algorithms could generate music.

Her 1980 album "The Expanding Universe" cemented her reputation. Music critics consistently rank it among the greatest ambient records ever made. It wasn't lo-fi ambient like later artists would produce. It was mathematically sophisticated, emotionally resonant, and built on principles she'd developed through years of algorithmic exploration.

Then came something even bigger: her composition "Harmony of the Worlds" made it onto the Voyager Golden Record. Launched in 1977, the Golden Record is humanity's message to any extraterrestrial intelligence we might encounter. Out of billions of songs, Spiegel's work was selected to represent human musical achievement. That's not hyperbole—it's literally the most widely distributed piece of music in human history, currently traveling through interstellar space.

But here's what makes Spiegel different from other pioneering electronic musicians: she's never been content to just create music herself. She's been obsessed with building tools that let others create music. This philosophy drove everything from her Bell Labs work to Music Mouse to her thinking about AI today.

When she talks about the difference between algorithmic music and AI, she's speaking from lived experience with both approaches. She's not a theorist pontificating from the sidelines. She built systems that worked, understood their constraints, and spent decades thinking about what works and what doesn't.

The Birth of Music Mouse: 1984-1986

The Macintosh changed everything in 1984, but not because of raw processing power. The Mac was slow, limited, and underpowered. What mattered was the mouse.

Spiegel immediately grasped something most developers missed: the mouse wasn't just a pointing device. It was an XY controller—a way to input continuous, two-dimensional data. And that meant it could control sound.

When she started coding Music Mouse, computers weren't sophisticated enough to run the kind of synthesis engines we take for granted today. But they could handle something elegant: constraint-based note generation. You moved the mouse around. The software kept you within a scale. Harmonies emerged from simple mathematical relationships.

Music Mouse worked like this: notes were arranged on a two-dimensional grid based on the scale you chose. As you moved the mouse, you navigated this space. The software tracked your position and generated notes based on your trajectory. You could set how notes related to each other—parallel motion, contrary motion, broken arpeggios, chords. All of it was transparent. All of it was rule-based.

The genius was in the simplicity. You didn't need to know music theory. You didn't need to understand synthesis. You just needed to move a mouse around and listen. The structure was built in. The intelligence was embedded in the algorithm itself.

This was revolutionary because it democratized algorithmic composition. Before Music Mouse, if you wanted to make algorithmic music, you needed to be a programmer. You needed access to expensive equipment. You needed to understand both music theory and code.

Music Mouse made it available to anyone with a Mac or Amiga. And crucially, users understood how it worked. If a melody seemed off, you could figure out why. The relationship between your mouse position and the notes produced was traceable. Auditable. Comprehensible.

For the next 35 years, Spiegel barely updated Music Mouse. She kept it running on Mac OS 9, which meant it became increasingly obsolete. But that obsessive restraint was telling. She wasn't chasing features. She wasn't trying to make it compete with modern DAWs. She was preserving an idea.

In 2026, nearly 40 years after its debut, Music Mouse got reborn with help from Eventide, the legendary audio processing company. But they did something significant: they preserved the core algorithm while updating the technology underneath. The logic remained transparent. The interface remained simple. They added better sound engines based on Spiegel's own Yamaha DX7 presets and enhanced MIDI capabilities, but the fundamental concept stayed intact.

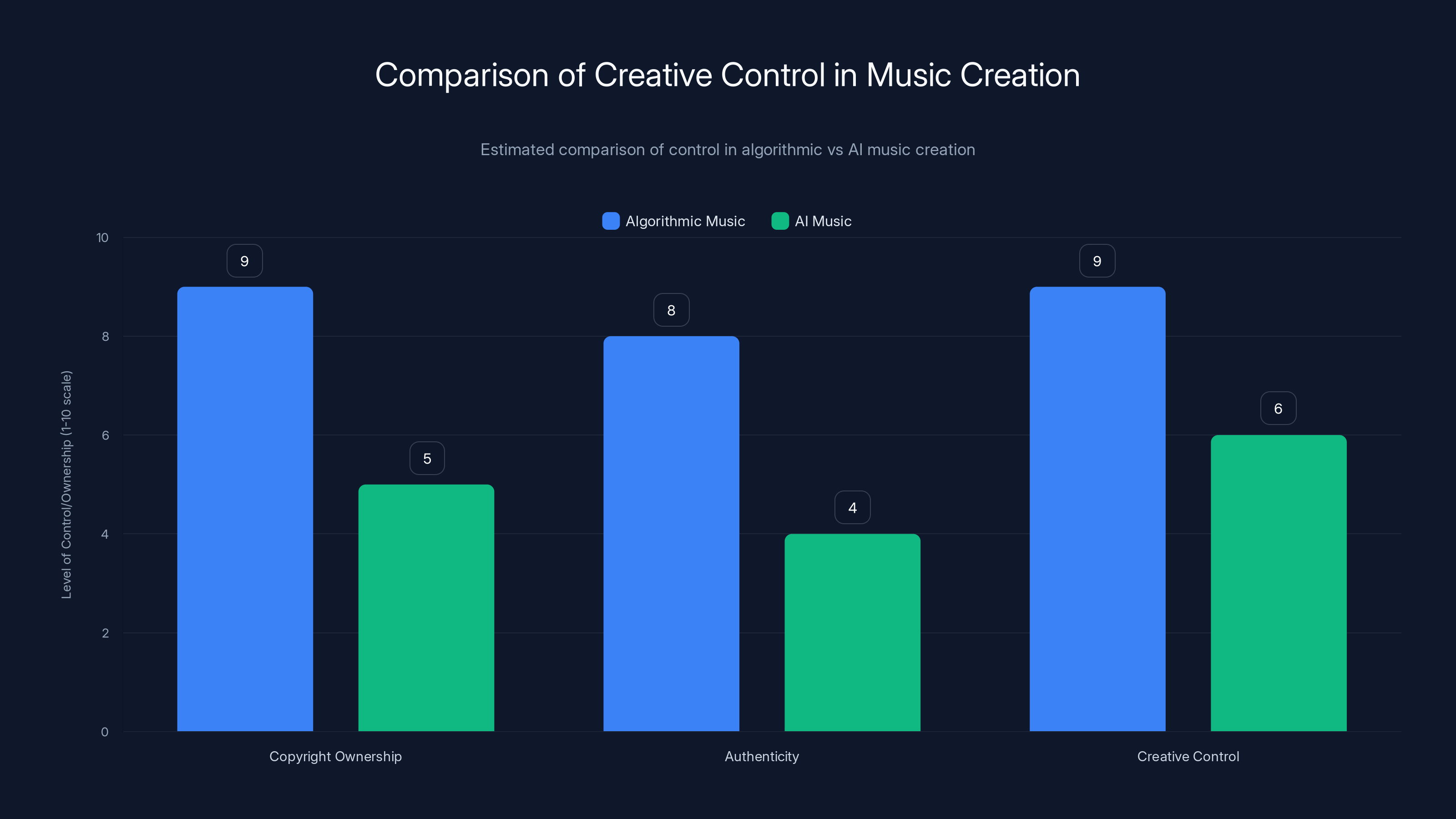

Algorithmic music tools offer more transparency and control to the user, while AI music tools provide higher complexity but less user control. Estimated data based on typical tool characteristics.

Algorithmic Music Defined: Rules Over Learning

Let's clarify what algorithmic music actually is, because the term gets thrown around loosely.

Algorithmic music is composition generated by predetermined rules, patterns, and mathematical relationships that the artist understands, designs, and can explain. The artist creates the algorithm. The algorithm generates variations. The artist remains in control throughout the process.

Examples include:

- Generative grammars: Rules like "if you hear note A, play note B next." Bach's compositions were analyzed in the 1950s as potential candidates for generative rule systems. His voice-leading patterns, harmonic progressions, and counterpoint techniques could theoretically be codified as algorithms.

- Fractal patterns: Using mathematical recursion to create self-similar structures at different scales. Some contemporary composers use fractal algorithms to generate melodies and harmonic progressions.

- L-systems: Originally developed to model plant growth, these rule-based systems can generate sequences of notes with organic branching patterns.

- Markov chains: First-order Markov chains look at what note comes after the current one, based on rules you define. No learning involved—just predetermined probabilities.

- Cellular automata: John Conway's Game of Life inspired musical systems where simple rules applied to a grid generate surprisingly complex patterns.

What unites all these approaches: the creator understands the system completely. If you ask the composer why a particular note was chosen, they can explain it by pointing to the algorithm. "This rule says that when we're at a 3rd, the next interval should be a 4th or a 2nd." There's no mystery.

Music Mouse fits squarely into this category. Spiegel understood every aspect of how notes were chosen. Users could understand it too. The algorithm was transparent.

Now contrast this with AI-generated music, which uses machine learning. These systems are trained on vast datasets of existing music. They learn statistical patterns about what notes typically follow other notes, what chord progressions sound "good," what melodic contours humans find appealing. Then they generate new music based on those learned patterns.

The crucial difference: the AI's creators don't fully understand why the model makes specific choices. When a neural network trained on millions of songs generates a particular melody, you can't point to a rule and explain it. You can't say "this note was chosen because of reason X." You can only see what the model outputs and reverse-engineer probability distributions that might explain it.

This isn't a limitation of current technology that will be solved eventually. It's fundamental to how machine learning works. Neural networks are statistical models. They encode learned patterns from data, not explicit rules. That's their strength—they can capture subtle patterns humans might miss. But it's also a fundamental difference from algorithmic composition.

The Philosophical Core: Intentionality vs. Emergence

Beyond the technical distinction lies something more fundamental: the philosophy of what music is and what composers do.

For Spiegel, composition has always been about intentionality. Even when using algorithmic systems, the composer is making deliberate choices about what rules to encode. You choose the scale. You choose whether notes move in parallel or contrary motion. You choose whether to use arpeggios or chords. These choices express your artistic vision.

The algorithm then explores the space of possibilities you've constrained. It's collaborative in a sense—you set the boundaries, and the system generates variations within those boundaries. But you remain in control of the fundamental character of the work.

AI-generated music flips this relationship. Instead of the composer setting constraints and the algorithm exploring them, the AI is trained on millions of examples and generates outputs based on learned statistical patterns. The composer becomes more like a curator than a creator. You can fine-tune parameters, reject outputs, ask the system to try again. But you're essentially asking a complex statistical model "what would music that sounds like your training data sound like?" rather than "what variations fit within my constraints?"

This distinction matters for artistic integrity. When you hear a piece made with Music Mouse, you're hearing the composer's vision expressed through an algorithmic system. The algorithm amplifies human intention. When you hear music generated by an AI trained on millions of songs, you're hearing a statistical inference about what music sounds like, guided by whatever parameters the user specified.

Spiegel's point—and she's increasingly vocal about this—is that these are fundamentally different creative acts. One preserves artistic authorship. The other distributes it across training data, the model, the user's prompts, and pure statistical luck.

This matters beyond just philosophy. It matters for copyright, authenticity, and the question of what it means to be a composer in the age of generative AI.

Music Mouse as a Smart Instrument: Not AI, but Intelligent

Spiegel called Music Mouse an "intelligent instrument," and that phrase deserves unpacking.

It's intelligent in the sense that it makes informed decisions on behalf of the user. If you're playing in the key of C major and you move your mouse to what would be a D-flat, the system doesn't play D-flat. It plays D-natural, the closest valid note in your chosen scale. The instrument corrects your input based on musical knowledge baked into the algorithm.

It's also intelligent in the sense that it generates harmonies and arpeggios automatically based on rules about voice-leading and chord construction. You don't have to think about parallel fifths or octave doubling. The algorithm handles it.

But this intelligence is fundamentally different from AI intelligence. It's not learning. It's not inferring patterns from data. It's enforcing rules that Spiegel designed based on music theory and her own aesthetic preferences.

This is crucial because it means the instrument doesn't surprise the user in fundamental ways. If you set Music Mouse to generate contrary motion chords, that's what you'll get. Predictably. Reliably. The intelligence serves the user's intention rather than operating independently.

Modern AI music tools are different. They can surprise you. They can generate outputs that don't match your initial prompt in interesting ways. Some artists love this—it feels generative, exploratory. Others find it frustrating because it's not responsive to artistic intent in the same way.

The intelligence in Music Mouse is instrumental intelligence. It's a tool that understands music theory and helps you navigate a constrained space. The intelligence in AI music generators is generative intelligence. It's a tool that produces variations based on learned patterns and statistical inference.

Both can be artistic. Both can produce interesting music. But they're not the same thing, and conflating them obscures what's actually happening when you use each tool.

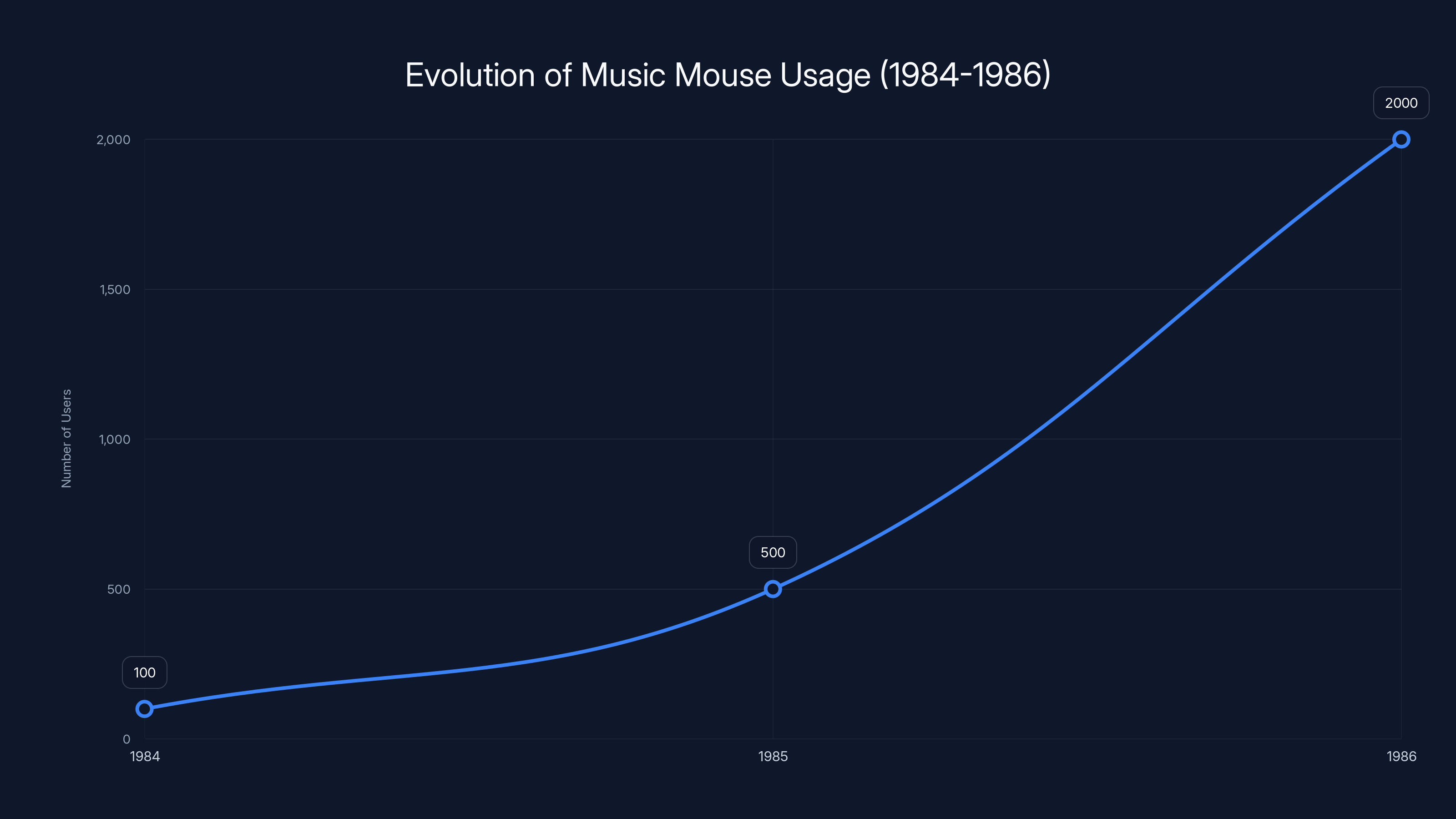

Estimated data shows a significant increase in Music Mouse users from 1984 to 1986, highlighting its growing popularity and accessibility.

The Computer as a Folk Instrument: Democratizing Creation

One of Spiegel's most interesting ideas is the computer as a folk instrument.

Folk instruments aren't necessarily simple—an accordion or sitar has mechanical complexity. But they're instruments that non-specialists can pick up and make music with. They're designed for accessibility. They're meant to be tools for musical expression, not expert-only devices.

When synthesizers first emerged, they were expert tools. You needed to understand voltage control, patch cables, envelope generators. They were monumental machines in recording studios, not something bedroom musicians could use.

The computer changed that. Not because computers are simple—they're not. But because with the right software, they could be. Music Mouse embodied this philosophy: a computer could be an accessible instrument if the software was designed with accessibility in mind.

This is why Spiegel's refusal to update Music Mouse is significant. She wasn't chasing technical sophistication. She was preserving a principle: that the computer could be a folk instrument—a tool for anyone to make music with, without extensive technical knowledge.

Modern AI music generators inherit this philosophy in some ways. They're designed to be extremely accessible. You don't need to understand music theory. You just type a prompt, and something emerges. But they're less transparent than Music Mouse. You don't understand why the AI made its choices. You can't easily predict what it will do.

This creates a paradox. AI music tools are more accessible in terms of ease of use. But they're less accessible in terms of understanding. With Music Mouse, a user could learn the algorithmic logic and eventually predict and control the output precisely. With AI, even power users don't fully understand the model's decision-making.

Spiegel's vision of the computer as a folk instrument suggests that transparency matters. A folk instrument is one where the user can understand how it works and develop mastery. You can't develop mastery over a neural network. You can only learn its habits and quirks through experimentation.

This distinction becomes crucial as we think about the future of music-making. Do we want tools that democratize creation by removing barriers to entry (AI tools)? Or tools that democratize creation by making the underlying logic transparent and learnable (algorithmic tools like Music Mouse)?

The answer probably isn't either/or. But it's worth asking which qualities matter more for different creative contexts.

How Algorithmic Music Works in Practice

Let's get concrete about what algorithmic composition actually looks like when you implement it.

Take a simple example: a melody generator based on Markov chains. A first-order Markov chain looks at the previous note and predicts what comes next based on probabilities you define.

You start by analyzing existing music. You notice that after C, the next note is most often D (30% of the time), then E (25%), then G (20%), and so on. You codify these probabilities. Then, when generating new music, the system picks the next note by drawing from these probability distributions.

This is algorithmic—fully rule-based and transparent. You can see exactly why each note was chosen. You can adjust the probabilities to change the character of the output. And critically, you understand that you're not trying to capture the essence of music. You're implementing a specific pattern-following rule.

Now imagine a more sophisticated algorithmic system: one that uses voice-leading rules based on species counterpoint. Fifteenth-century composers developed rules about how voices should move relative to each other. Modern algorithmic systems can encode these rules: "avoid parallel fifths," "prefer stepwise motion," "resolve tendency tones." You can weight these rules differently to create different musical styles.

When such a system generates a melody, every note can be justified by reference to these rules. "This note was chosen because the previous note was a sixth above the bass, and the rule says sixths should resolve to unisons or octaves, so this note moves down." Complete transparency.

Music Mouse implements something similar but simpler. It doesn't use voice-leading rules as much as it uses basic harmonic principles: intervals, motion types, and harmonic function. But the principle is identical—everything the system does can be explained by the algorithm you've designed.

The key workflow looks like this:

- Define constraints: What scale? What harmonic rules? What rhythmic patterns?

- Implement the algorithm: Code up the rules that enforce these constraints

- Generate variations: Let the system explore the space you've defined

- Edit and refine: Manually adjust outputs, tweak rules, iterate

- Understand the results: You can always explain why the system made specific choices

Compare this to AI-based composition:

- Train the model: Feed millions of songs to a neural network

- Specify parameters: Give it a style, mood, or text prompt

- Generate outputs: The model produces variations based on learned patterns

- Evaluate and regenerate: You like some outputs, reject others, ask the model to try again

- Accept the mystery: You can't fully explain why the model made specific choices

Both workflows can produce music. Both can feel creative. But the second one delegates more authority to the model. The model isn't following rules you designed—it's following patterns it learned from data.

Why This Distinction Matters: Legal, Ethical, and Artistic Implications

The difference between algorithmic music and AI music isn't academic. It has real consequences.

Copyright and Authorship: If you compose something using Music Mouse, you clearly own it. You designed the algorithm (or chose to use Spiegel's). You made the creative choices that shaped the output. The music is unambiguously yours.

If you prompt an AI music generator, who owns the result? You typed the prompt, but the AI was trained on millions of songs. Those training songs contained copyrighted work. Did you plagiarize? Did you create a derivative work? The legal system is still figuring this out, but the ambiguity itself is troubling.

Authenticity and Disclosure: When you release a piece made with Music Mouse, you can honestly say "I composed this with algorithmic assistance, and here's exactly how the algorithm worked." Listeners understand that they're hearing your artistic vision expressed through mathematical rules.

When you release music generated by an AI, the disclosure is murkier. The AI was trained on millions of songs. Your output is a statistical inference about what music sounds like based on that training data. You curated and refined it, but large parts of it emerged from patterns the model learned that you don't fully understand.

This matters for artists building reputation and trust. If your artistic claim is that you're doing something novel, people want to know that you're not just regurgitating patterns from your training data.

Creative Control and Artistic Vision: With algorithmic systems, the artist remains in control throughout the process. You design the rules. You understand why the system makes choices. You can fine-tune to match your vision.

With AI systems, you have less control. You can't easily adjust the underlying model. You can regenerate and curate outputs, but you're working with a tool that doesn't fundamentally respect your artistic intentions in the same way.

For some artists, this is liberating—it feels generative, exploratory. For others, it feels frustrating—it feels like you're negotiating with a tool rather than commanding it.

Labor and Training Data: AI music models are trained on existing music. That training data represents the work of millions of musicians. When an AI generates output, it's drawing on patterns learned from those musicians' work. The musicians didn't consent. They didn't know their work would be used to train models that might eventually replace them.

Algorithmic systems don't depend on training data. They depend on rules you design. This sidesteps the ethical questions around using existing work without permission.

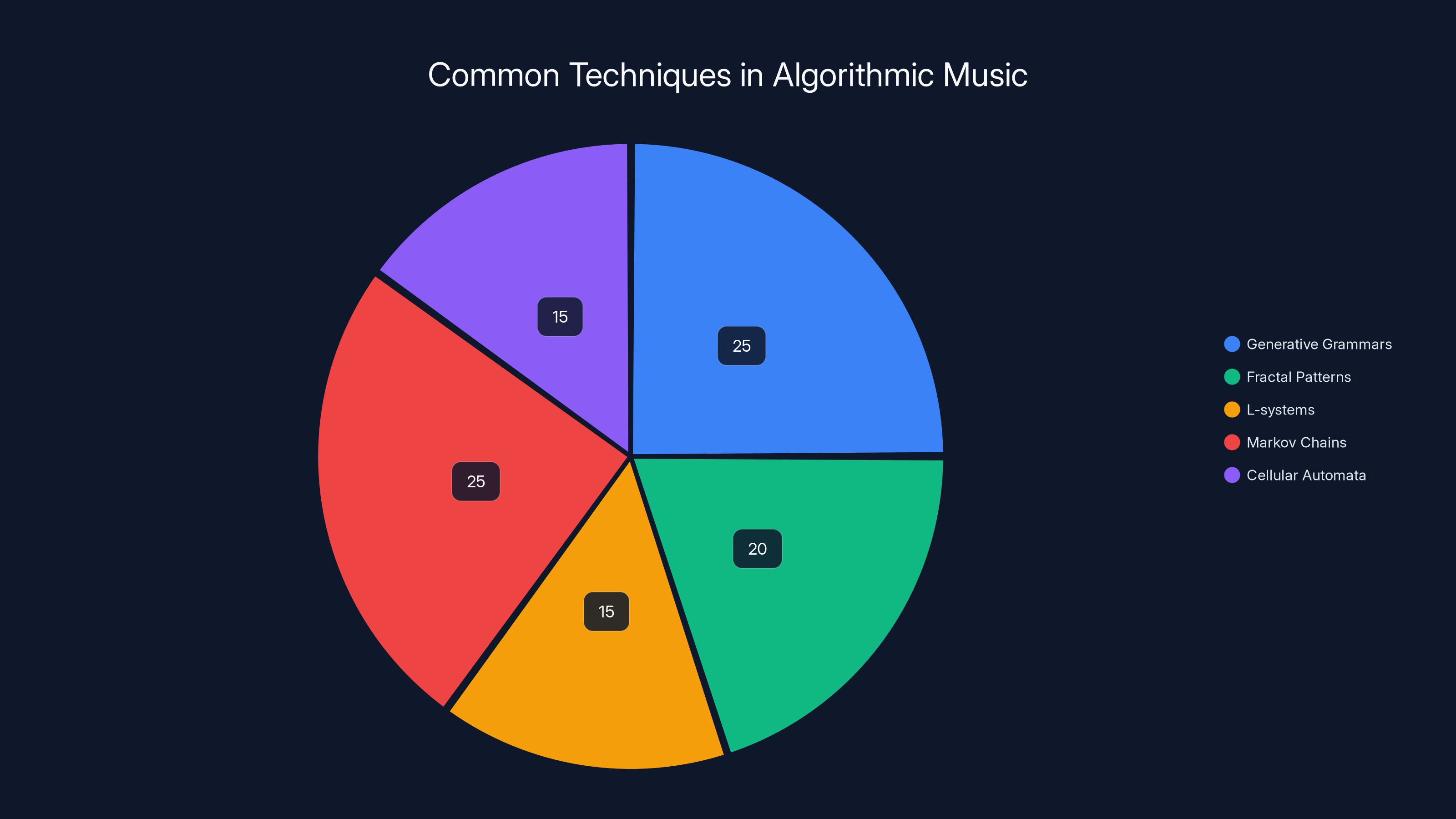

Estimated data showing the distribution of various algorithmic techniques used in music composition. Generative grammars and Markov chains are among the most commonly used methods.

The Modern Resurgence of Algorithmic Music

Interestingly, as AI has flooded the creative space, there's a growing resurgence of interest in algorithmic systems like Music Mouse.

Part of this is backlash against black-box AI. Artists are tired of tools that don't respond predictably to their intentions. They want instruments they can understand and master. Algorithmic systems deliver that.

Part of it is the realization that algorithmic composition has creative possibilities AI doesn't easily access. If you want to generate music based on the Fibonacci sequence, or Kepler's celestial mechanics, or some other non-musical system, algorithmic approaches are cleaner. You're not trying to teach a neural network about mathematical relationships. You're just implementing the math directly.

Part of it is philosophical. There's a growing movement emphasizing intentionality, transparency, and human control in creative tools. Algorithmic systems align with these values.

And part of it is simply nostalgia and rediscovery. Music Mouse became obsolete because Spiegel never updated it. But the underlying ideas never stopped being interesting. Now with the 2026 revival, people are realizing what they missed.

The revival is significant because it's not retro-fetishism. Eventide and Spiegel didn't just emulate Music Mouse on modern hardware. They updated the sound engine to be more sophisticated while preserving the fundamental algorithmic approach. They added MIDI capabilities to integrate with modern production workflows. They updated the UI for contemporary sensibilities.

But the core idea—that a simple, transparent algorithm could be a powerful creative tool—remains unchanged. This suggests that algorithmic composition isn't a dead historical approach. It's a distinct and valid alternative to AI that's becoming more relevant as people react against AI's opacity.

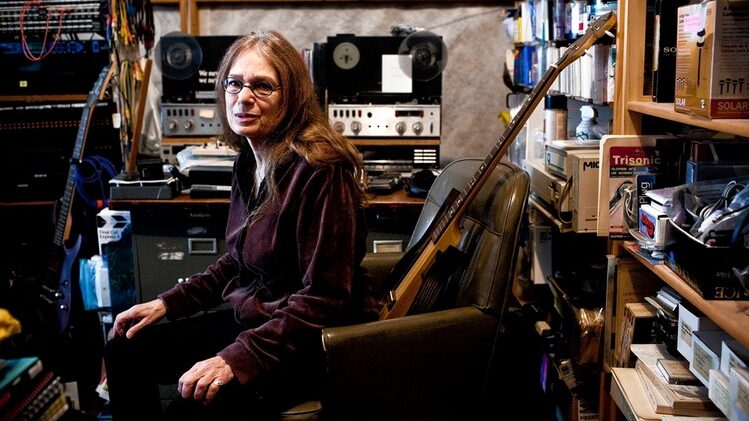

Spiegel's Critique of AI Music: What She's Actually Saying

When Spiegel talks about the difference between algorithmic music and AI, she's not saying AI is bad or that artists shouldn't use it. She's making a more nuanced point.

Spiegel's critique has several parts:

First, transparency matters: You should understand how your creative tools work. This isn't about being a Luddite. It's about artistic responsibility. If your tool is making decisions you don't understand, you're delegating your artistic authority to something you can't fully control.

Second, authorship claims need honesty: If you're claiming to be the composer of a piece, you should be able to explain how it was made. "I prompted an AI" is an honest statement. "I composed this piece" might be misleading if a neural network did much of the work based on learned patterns.

Third, algorithmic approaches preserve intentionality: When you design an algorithm and use it to generate music, you're expressing your artistic vision through mathematical rules. This is legitimate and interesting. But it's different from asking an AI what it thinks music sounds like.

Fourth, AI training data raises ethical issues: AI music models are trained on existing music, often without the consent or knowledge of the musicians whose work is being learned from. This is a serious problem that algorithmic systems sidestep entirely.

Fifth, accessibility matters differently: AI tools are extremely easy to use—just type a prompt. But they don't teach you anything about music. Algorithmic tools have a higher learning curve, but they teach you about music structure and composition principles. Different tools serve different purposes.

Spiegel isn't anti-technology. She's pro-understanding. She wants artists to think clearly about what tools do and how they work. She wants creative responsibility, not blind delegation to algorithms—whether those algorithms are traditional rule-based systems or neural networks.

This is a reasonable position. It's not reactionary. It's thoughtful. And it's increasingly relevant as AI tools proliferate and artists worry about losing agency and authorship.

Algorithmic Music in Production Workflows Today

How do contemporary musicians actually use algorithmic composition tools today?

Some use traditional tools like Max/MSP or Pure Data—environments where you can build custom algorithmic systems. These are powerful but require programming knowledge. They attract musicians who are also developers.

Others use pattern sequencers and Euclidean rhythm generators. These are algorithmic—they generate rhythmic patterns based on mathematical sequences. They're intuitive and accessible.

Some use generative tools based on music theory rules. Scaler and Hookpad are contemporary examples—they use music theory knowledge to suggest scales, chords, and progressions that fit together. They're algorithmic in the Spiegel sense: they implement music theory rules to constrain and suggest, rather than learning from data.

And some use hybrid approaches: they start with an algorithmic system to generate the basic structure, then manually refine, edit, and arrange the output. This combines the best of both worlds—algorithmic suggestion plus human curation.

The workflow typically looks like:

- Set parameters: Key, scale, style, length, etc.

- Generate algorithmic variations: Let the system explore possibilities

- Select and refine: Choose variations you like, edit details

- Orchestrate and arrange: Add instrumentation, dynamics, effects

- Mix and polish: Traditional audio engineering

This is different from AI workflows where you generate, regenerate, and hope for something good. Algorithmic workflows give you more predictable control over the generation process.

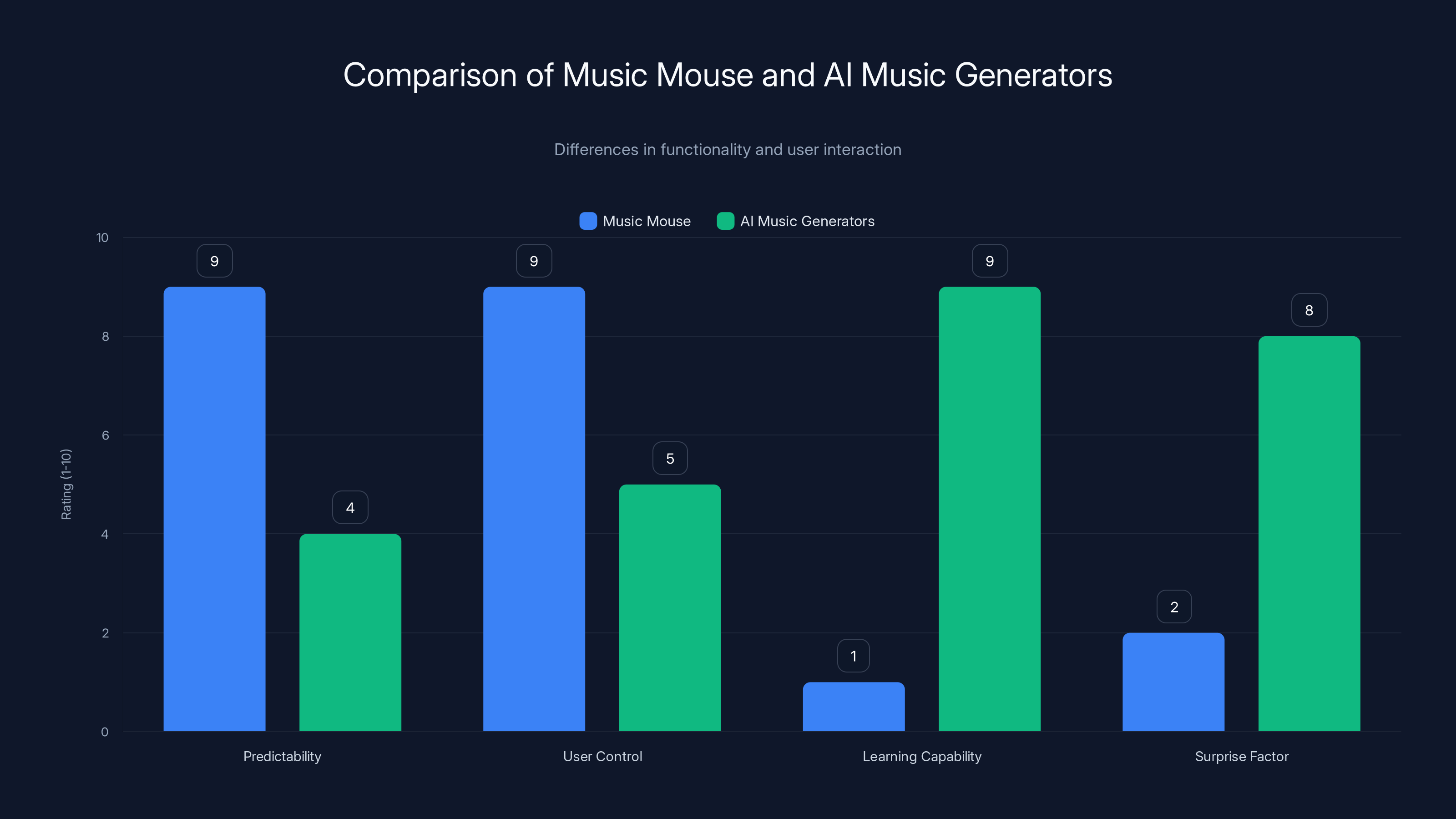

Music Mouse offers high predictability and user control but lacks learning capability, unlike AI music generators which excel in learning and surprise factor. Estimated data.

The Cultural Moment: Why This Conversation Matters Now

Why is Spiegel's distinction between algorithmic music and AI suddenly so important in 2025-2026?

Because the music industry is having a collective panic attack about AI. Artists worry AI will replace them. Platforms struggle with copyright questions. The public is confused about what AI music is and whether it's legitimate.

In this moment, Spiegel's clarity is valuable. She's saying: "There are different approaches. They're not interchangeable. Some preserve artistic authorship and transparency. Others don't. Choose tools that match your values."

This is especially relevant for younger musicians who might not realize algorithmic approaches exist as an alternative to AI. They've grown up in the age of generative AI. They might assume that if you want computational assistance with composition, AI is your only option.

It's not. Algorithmic approaches are available, learnable, and increasingly relevant. Some of the most interesting contemporary music is being made with algorithmic tools that are more transparent and controllable than AI systems.

Spiegel's voice matters here because she has credibility across multiple domains: classical composition, electronic music, computer science, and philosophy of technology. When she distinguishes between algorithmic music and AI, people listen—not because she's anti-AI, but because she's deeply informed and intellectually honest.

The Future: Coexistence and Choice

Where does this go? Will algorithmic music and AI music coexist? Will one dominate?

My prediction is coexistence, with different tools serving different purposes.

AI music tools are excellent for rapid exploration, inspiration, and creation at scale. If you need a hundred variations on an idea quickly, AI can generate them. If you want to explore stylistic possibilities, AI can show you options you might not have considered.

Algorithmic tools are excellent for precise control, reproducibility, and deep understanding. If you want to build a system that generates music according to specific rules you designed, algorithmic tools are cleaner. If you want to teach yourself music theory through composition, algorithmic tools are more pedagogically valuable.

The sophisticated contemporary composer might use both. They might use algorithmic tools to generate base structures, then feed those into an AI to explore variations, then manually refine the results. Or they might use AI to generate ideas, then reverse-engineer them as algorithmic rules they can control.

What seems unlikely is that AI will completely replace algorithmic approaches. There's too much creative value in the transparency, control, and intentionality that algorithmic systems provide. And as people react against AI, they're rediscovering algorithmic methods.

For the music industry, this means several things:

- Platforms should support diverse tools: Don't assume AI is the only option. Support algorithmic composition systems, too.

- Disclosure should be clear: Musicians should be able to indicate whether they used algorithmic systems, AI, or human composition (or combinations).

- Education should expand: Music programs should teach both algorithmic composition and AI, helping students understand the differences and choose appropriate tools.

- The legal system needs clarity: As copyright questions emerge, lawmakers should distinguish between algorithmic systems (which raise fewer ownership questions) and AI systems (which raise many).

Spiegel's 40-year perspective is valuable here. She's seen hype cycles before. She's seen technologies emerge and mature. She knows that the tools that survive aren't always the most hyped. They're often the ones that solve real creative problems transparently and reliably.

Music Mouse did that. It still does. And as AI floods the market with quick-and-easy solutions, transparent, understandable, controllable algorithmic tools are becoming more valuable, not less.

How Music Mouse Works: A Technical Deep Dive

Let's get specific about the actual mechanics of Music Mouse, because understanding the algorithm illuminates why Spiegel emphasizes its difference from AI.

Music Mouse presents notes arranged on an XY grid. The grid structure depends on the scale you choose. In a major scale, notes are arranged so that moving in one direction gives you stepwise motion, while moving perpendicular gives you interval skips.

As you move the mouse, the software tracks your position and generates notes accordingly. But it's not one note per position. It can generate harmonies—multiple voices sounding together—based on rules you set.

Those rules include:

- Motion type: Parallel (all voices move the same interval), contrary (voices move in opposite directions), or oblique (some voices hold while others move)

- Chord type: Whether multiple simultaneous notes form a chord or an arpeggio

- Voice leading: How quickly voices can move, whether they can cross, etc.

All of these are musical concepts that predate computers. They come from classical music theory and counterpoint. Spiegel implemented them as explicit rules in code.

When you move the mouse, the algorithm:

- Tracks position: Where is the mouse right now?

- Maps to scale: Which note does this position correspond to?

- Applies voice-leading rules: If I play this note in voice one, what should happen in voice two based on my motion-type rules?

- Generates output: Play the notes through the synthesizer

- Repeats: As you continue moving, repeat the process

Every decision the algorithm makes can be traced back to a rule you set or a classical music theory principle. If you ask "why did it play that note?", the answer is always "because you set the motion type to parallel, so the upper voice moved up the same interval as the lower voice."

This is radically different from an AI model. With an AI, if you ask why it generated a particular sequence of notes, the answer is essentially "because that's what my learned probability distributions suggest." The training data influences the output, but the influence is implicit and hard to trace.

Algorithmic music offers higher control and clear ownership compared to AI music, which involves more ambiguity in authorship and creative control. Estimated data based on typical discussions in the field.

Real-World Applications: Where Algorithmic Composition Works Today

Who's actually using algorithmic composition in 2025?

Video game composers: Games need dynamic music that responds to gameplay. Algorithmic systems can generate variations in real-time based on game state. A composer might design an algorithm that adds complexity as tension rises, removes it as it falls. This gives games responsive music without needing thousands of prerecorded tracks.

Film and TV composers: Background scores need variations that stay consistent in style but vary in detail. Algorithmic systems let composers generate these variations maintaining authorial consistency.

Generative art projects: Artists working with visual and sonic components sometimes use algorithmic music. The artist understands the rules, can reproduce results, and uses the algorithm as an expressive medium.

Educational software: Music theory teachers use algorithmic systems to generate practice examples. Students see the algorithm, understand the rules, and learn composition principles.

Installation and ambient music: Artists creating long-form generative installations sometimes use algorithmic composition. The system generates variations endlessly, but all variations respect rules the artist designed.

Experimental composition: Contemporary classical composers use algorithmic systems to explore mathematical relationships in sound. This isn't popular in a mainstream sense, but it's artistically vital.

What's notably absent from this list: pop music, commercial music, and industry-standard production. For those domains, AI tools have largely won because they're easier to use and faster to produce results.

But that's changing. As artists tire of AI, as copyright questions become pressing, as people want to understand their tools better, algorithmic approaches are becoming more relevant again.

The Business Case: Why Companies Are Investing in Algorithmic Tools Again

When Eventide decided to revive Music Mouse, they were betting on something: that there's market demand for transparent, controllable algorithmic tools.

This is interesting because the easy move would have been to acquire AI music technology and rebrand it. That's what most companies are doing. But Eventide chose to partner with Spiegel and resurrect an old algorithmic tool.

Why? A few reasons:

Differentiation: If every company is offering AI music tools, you stand out by offering something different. Algorithmic tools are increasingly rare, which makes them valuable.

Professional appeal: Professional musicians and sound designers value control and transparency. They're willing to pay for tools that give them what they want and work the way they expect. AI tools are still seen as somewhat unpredictable.

Copyright clarity: Algorithmic tools don't raise the thorny copyright questions that AI tools do. From a business perspective, algorithmic tools are legally cleaner.

Nostalgia plus innovation: Music Mouse has 40 years of history and cultural significance. But the 2026 version isn't just retro—it's genuinely updated with modern synthesis and MIDI integration. This combines nostalgia with practical innovation.

Niche but passionate market: There's a dedicated community of musicians and sound designers who love algorithmic approaches. They're not a massive market, but they're highly engaged and willing to pay for quality tools.

This suggests a business opportunity: as the market saturates with AI tools, there's room for companies to offer transparent algorithmic alternatives. Not as replacements for AI, but as complements. Different tools for different purposes.

For startups thinking about music technology: the AI space is crowded. But the algorithmic composition space is mostly empty. That's either a huge opportunity or a warning sign that nobody wants this stuff. Based on the enthusiastic response to Music Mouse's revival, it seems more like an opportunity.

The Pedagogical Value: Teaching Through Algorithmic Tools

One major difference between algorithmic and AI tools: pedagogical value.

When you use Music Mouse, you learn something. You learn how scales constrain melodic motion. You learn how voice-leading rules work. You learn how mathematical relationships create harmony. These are deep lessons about music structure.

When you prompt an AI music generator, you're not learning much about music. You're learning how to write better prompts. You're learning aesthetic preferences of the training data. But you're not learning compositional principles.

This matters especially for students. A student using Music Mouse to compose will eventually understand why certain progressions sound good—because they follow voice-leading rules they can see and understand. A student using AI will eventually notice that certain prompts work better than others, but without understanding why.

For music education, algorithmic tools have real value. They teach by making rules explicit. They teach by requiring students to think about constraints and possibilities. They teach by being transparent enough to understand.

Spiegel herself has been an educator. She's taught at NYU and worked with students for decades. The pedagogical philosophy behind Music Mouse reflects her teaching experience: create tools that help people understand music through direct interaction.

This is especially relevant for non-musicians who want to learn composition. AI tools let you create without learning. Algorithmic tools let you create while learning. For education, that second option is often better.

The Philosophical Endpoint: What We Choose Reveals What We Value

At the deepest level, Spiegel's distinction between algorithmic music and AI is about what we value in creative tools.

If we value speed, ease, and rapid output, AI tools are superior. You can generate more music faster with less effort.

If we value understanding, control, and intentionality, algorithmic tools are superior. You understand exactly what's happening and can guide the process precisely.

If we value exploration and surprise, AI tools might be more interesting. They can suggest things you wouldn't have thought of. Algorithmic tools are more predictable.

If we value authorship, transparency, and honesty, algorithmic tools are cleaner. You can claim full authorship. You can explain exactly how the music was made.

The choice isn't between good and bad tools. It's between different good tools that serve different values.

Spiegel's point is that we should choose consciously. We should understand what each tool does and what it implies for our artistic practice. We shouldn't just adopt AI because it's trendy and hyped. We should also not dismiss it as trash. We should think about what we actually want.

For someone who values deep artistic control and transparent creative process, algorithmic tools will always have appeal. For someone who values rapid exploration and doesn't mind ceding some control, AI makes sense.

The future probably involves both coexisting. Different artists will choose different tools based on their values and workflow preferences. What matters is that we understand what we're choosing and why.

This is mature thinking about technology. Not "new is always better." Not "old is always better." Just "different tools serve different purposes, so choose based on your values."

FAQ

What is the difference between algorithmic music and AI music?

Algorithmic music uses predetermined mathematical rules designed by the composer or programmer to generate variations within a constrained space. The creator understands and can explain every decision the algorithm makes. AI music uses neural networks trained on existing music to generate new compositions based on learned statistical patterns. The creators don't fully understand why the AI makes specific choices—they only see what it outputs. One preserves artistic intention and transparency; the other distributes decision-making across training data, the model, and learned patterns.

Why did Laurie Spiegel create Music Mouse?

Spiegel created Music Mouse in 1986 specifically to use the computer mouse (then new to Macintosh computers) as a musical input device. She wanted to create an "intelligent instrument" that would let people make algorithmic music without needing to understand music theory or programming. By constraining input to a musical scale and implementing voice-leading rules, she made sophisticated algorithmic composition accessible to anyone with a Mac or Amiga computer. The tool embodied her philosophy of the computer as a folk instrument—an accessible creative tool for non-specialists.

What makes Music Mouse different from modern AI music tools?

Music Mouse uses transparent, human-designed algorithms that users can understand and control completely. When you use it, you know exactly why it generates each note based on the rules you've set. Modern AI music tools use neural networks trained on millions of songs, so the decision-making process is opaque and based on learned patterns rather than explicit rules. With Music Mouse, the artist remains fully in control. With AI, the artist cedes significant control to a statistical model. Both can produce interesting music, but they represent fundamentally different creative processes.

How does Music Mouse generate harmonies and melodies?

Music Mouse arranges notes on an XY grid based on the scale you choose. As you move the mouse, it maps your position to notes within that scale, ensuring you can't play wrong notes. Beyond single notes, it implements voice-leading rules from music theory. You choose whether voices move in parallel motion (same intervals), contrary motion (opposite directions), or other patterns. You can set whether it generates chords or arpeggios. All these rules are explicit, transparent, and based on classical music theory principles. Every note generated can be explained by these predetermined rules.

What are the advantages of algorithmic composition over AI?

Algorithmic composition offers several advantages: complete transparency (you understand every decision), full artistic control (you design the rules), reproducibility (you can create the same music again if needed), copyright clarity (you unambiguously own the work), and pedagogical value (you learn music structure through the process). Algorithmic tools don't depend on training data, so they avoid ethical questions about using existing musicians' work without permission. They're also more predictable—you know what variations you'll get, which appeals to artists who want precision over surprise.

Why is Music Mouse being revived in 2026?

Music Mouse is being revived because there's renewed interest in transparent, controllable creative tools as artists react against the opacity of AI systems. Eventide partnered with Spiegel to modernize the tool while preserving its core algorithmic approach. The new version updates the sound engine (with Spiegel's own Yamaha DX7 patches), adds MIDI integration for modern workflows, and brings the software to contemporary operating systems. After 35 years of running on Mac OS 9, modern musicians can finally use the tool again. The revival reflects both nostalgia and genuine recognition that algorithmic composition remains artistically valuable.

Can algorithmic tools and AI tools work together?

Yes, many contemporary composers use hybrid workflows. They might use algorithmic tools to generate a basic structure based on explicit rules, then feed that into an AI to explore variations, then manually refine the results. Or they might use AI to generate ideas, then reverse-engineer those ideas as algorithmic rules they can understand and control. Different tools serve different purposes—algorithmic tools provide precision and understanding, while AI tools provide rapid exploration and novel suggestions. Used strategically, both can enhance each other.

Is Spiegel saying AI music is bad?

No. Spiegel is making a more nuanced point: algorithmic music and AI music are fundamentally different approaches with different implications for authorship, transparency, and control. She's arguing that artists should understand these differences and choose tools consciously based on their values. AI isn't bad—it's just different. For some creative purposes, it's ideal. For others, algorithmic approaches better serve artistic intentions. Her critique is about honesty and understanding, not absolute condemnation of AI technology.

What does Spiegel mean by the computer as a folk instrument?

A folk instrument is one that non-specialists can pick up and make music with, and that allows users to develop practical mastery through understanding. Spiegel argues that computers, when designed appropriately, can function as folk instruments. Music Mouse exemplifies this—it doesn't require music theory knowledge or programming ability, but through use, you learn music principles and develop skill. Modern AI tools are accessible (just type a prompt), but they don't teach mastery the way algorithmic tools do. The concept emphasizes designing tools for understanding and learnable control, not just ease of use.

Are algorithmic tools still relevant in 2025?

Absolutely. While AI has captured most hype and market attention, algorithmic approaches remain relevant and artistically valuable. They offer transparency, control, and pedagogical benefit that AI can't provide. Video game composers, film composers, and experimental musicians use algorithmic systems successfully. As the market saturates with AI tools and artists discover limitations of black-box approaches, algorithmic tools are experiencing renewed interest. The Music Mouse revival is just one example. The combination of nostalgia, technical maturity, and philosophical preference for transparency suggests algorithmic tools will remain important parts of the compositional toolkit.

Conclusion: Understanding the Tools, Choosing Consciously

When Laurie Spiegel talks about the difference between algorithmic music and AI, she's not being nostalgic or reactionary. She's being precise.

After 50 years at the forefront of computer music—from Bell Labs to the Voyager Golden Record to Music Mouse to the present day—she understands these technologies deeply. She's not afraid of innovation. She's afraid of innovation that obscures understanding. She values tools that empower artists to make intentional, explicable creative choices.

The distinction matters now more than ever because AI is everywhere, and many people assume it's the only option for computational assistance with creation. It's not. Algorithmic approaches exist, and they're experiencing a genuine resurgence.

This isn't a battle between old and new. It's about recognizing that different tools serve different purposes, and the most sophisticated creative practice involves understanding those differences and choosing based on your actual needs.

Someone building a video game needs AI-like responsiveness and vast variation. Algorithmic approaches might be too constraining. Someone creating an installation piece wants music that can run infinitely while respecting specific constraints. Algorithmic approaches are perfect. Someone learning composition wants to understand music structure. Algorithmic tools are unbeatable. Someone exploring sound quickly and cheaply wants AI's ease of use and speed.

The mature approach isn't loyalty to one tool or approach. It's understanding what you're choosing and why.

Music Mouse's 40-year journey—from 1986 to 2026, from Mac OS 9 to modern systems, from obscurity to cultural significance—suggests that transparent, controllable, understandable tools have lasting value. Not because they're "old" or "authentic," but because they serve real creative needs.

As you think about your own creative practice, whether in music, visual art, writing, or any other domain, Spiegel's framework is useful: What control do I need? What transparency do I want? Do I need to understand the tool, or is the output what matters? What values do I want my creative process to embody?

Choose your tools based on those questions, not on hype or ease. That's the real lesson from someone who's been choosing creative tools wisely for half a century.

The future of music-making probably involves both algorithmic and AI approaches coexisting, each serving different purposes, each valuable to different creators. What matters is that we understand what we're choosing and that we choose consciously, with clear eyes about what each approach offers and what it costs.

That's the Spiegel difference. That's the clarity this moment needs.

Key Takeaways

- Algorithmic music uses transparent, human-designed rules the artist understands completely, while AI music relies on learned patterns from training data

- Laurie Spiegel pioneered algorithmic composition at Bell Labs and created Music Mouse to democratize it through an intuitive mouse-based interface

- The distinction between algorithmic and AI approaches matters for copyright, artistic control, authorship clarity, and ethical implications around training data

- Music Mouse's 40-year journey and 2026 revival reflect growing artist interest in transparent, controllable creative tools as alternatives to black-box AI

- Different creative tools serve different values—choose based on whether you prioritize control, transparency, speed, exploration, or learning outcomes

Related Articles

- Georgia Tech's Guthman Competition: The Future of Experimental Instruments [2026]

- Spotify's About the Song Feature: What You Need to Know [2025]

- M83's Dead Cities, Red Seas & Lost Ghosts: The Post-Rock Masterpiece You Need to Hear [2025]

- Google's Project Genie AI World Generator: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Deezer's AI Music Detection Tool Goes Commercial [2025]

- Roland TR-1000 Drum Machine: Ultimate Guide [2025]

![Laurie Spiegel on Algorithmic Music vs AI: The 40-Year Evolution [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/laurie-spiegel-on-algorithmic-music-vs-ai-the-40-year-evolut/image-1-1771333686307.jpg)