Linux Kernel Succession Plan After Linus Torvalds: What You Need to Know [2025]

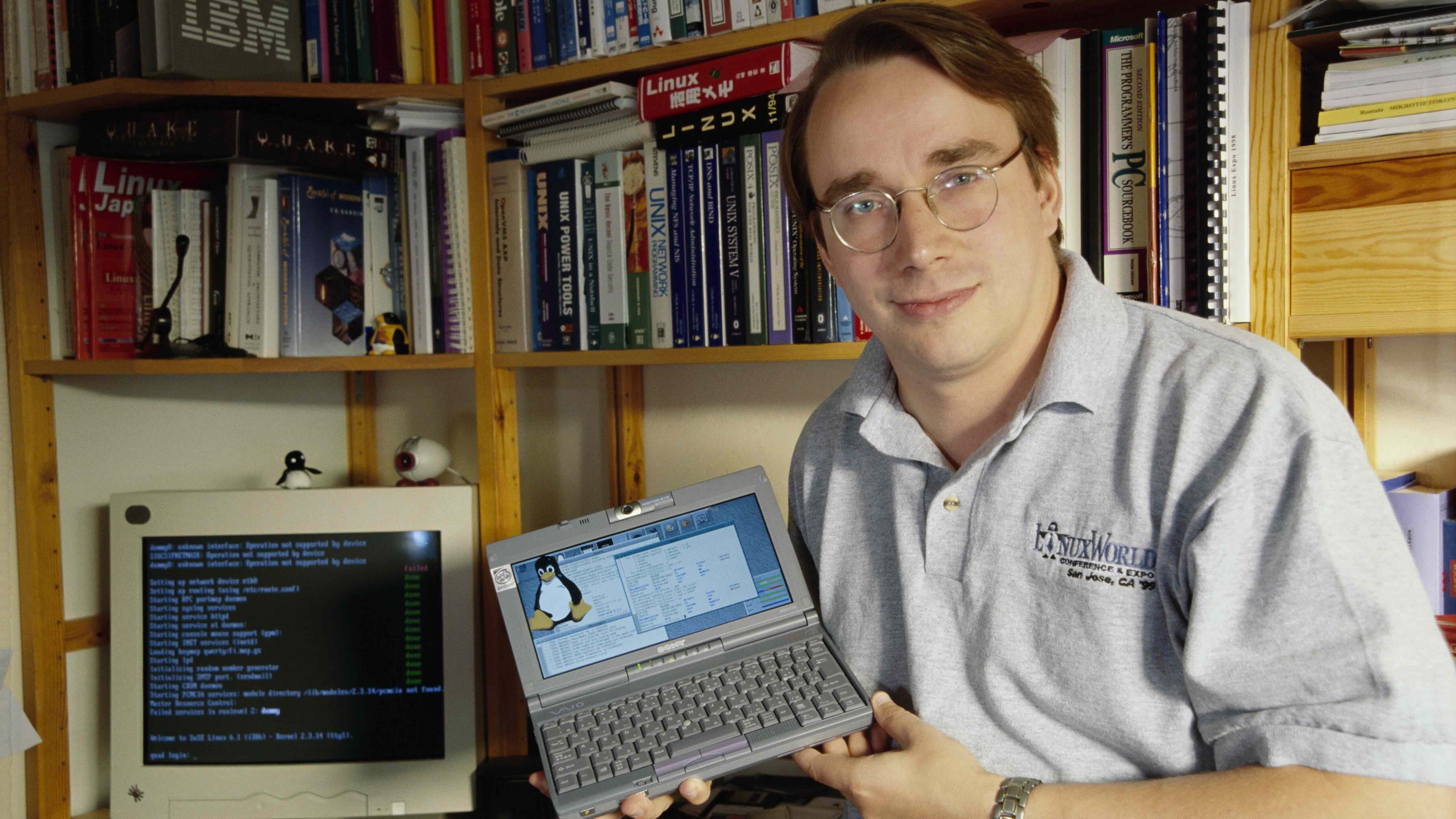

For more than three decades, one person has controlled the most critical piece of infrastructure powering everything from your smartphone to global data centers. That person is Linus Torvalds, creator and benevolent dictator of the Linux kernel.

But here's what kept senior kernel developers up at night: there was no formal plan for what happens when he's gone.

This wasn't paranoia. It was a real structural vulnerability in one of the world's most important open source projects. A single person holding absolute decision-making power with zero documented succession process isn't a strength. It's a weakness disguised as tradition.

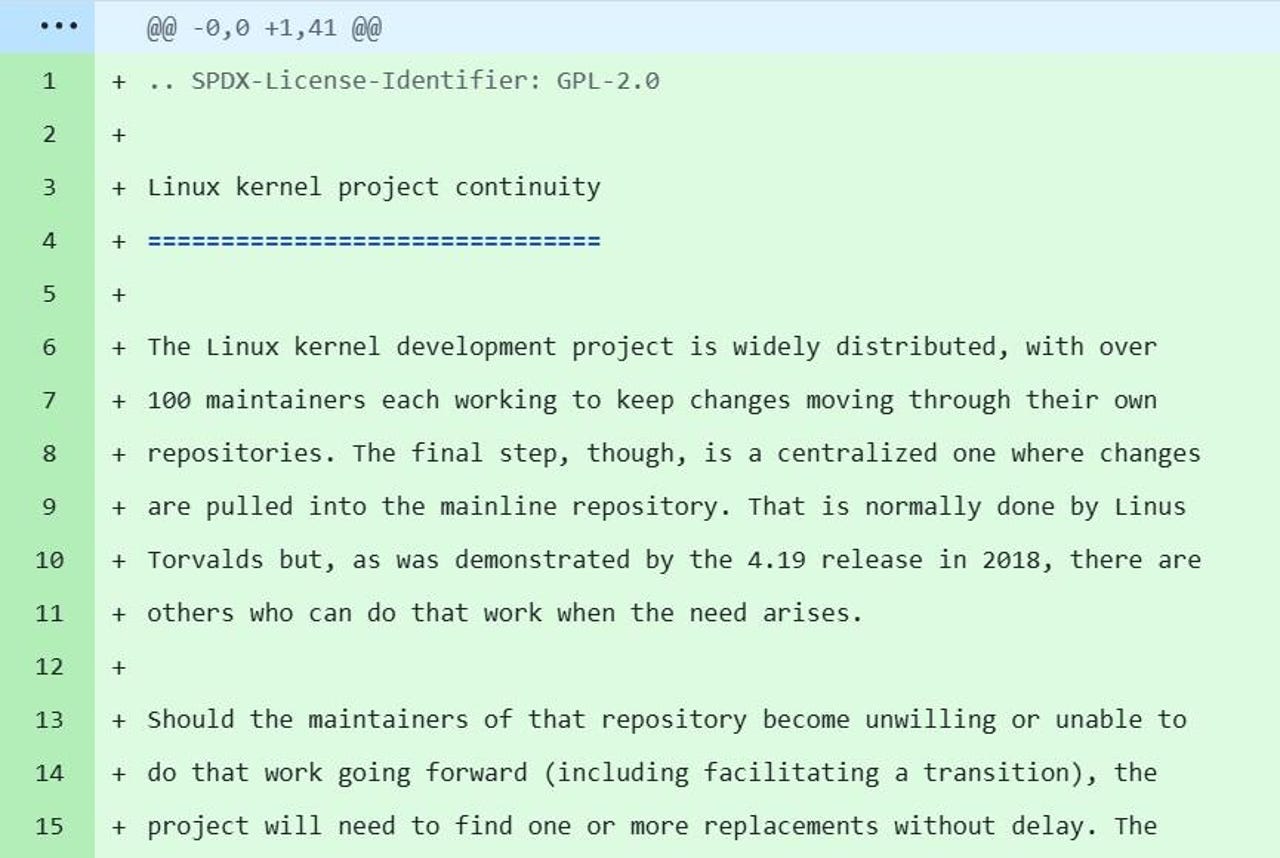

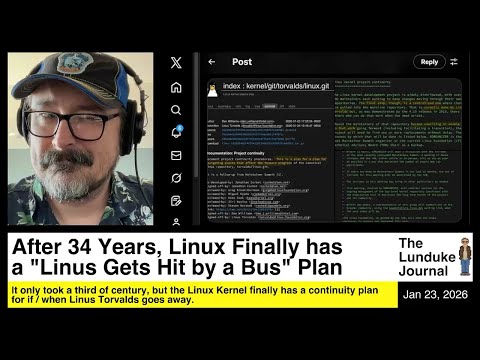

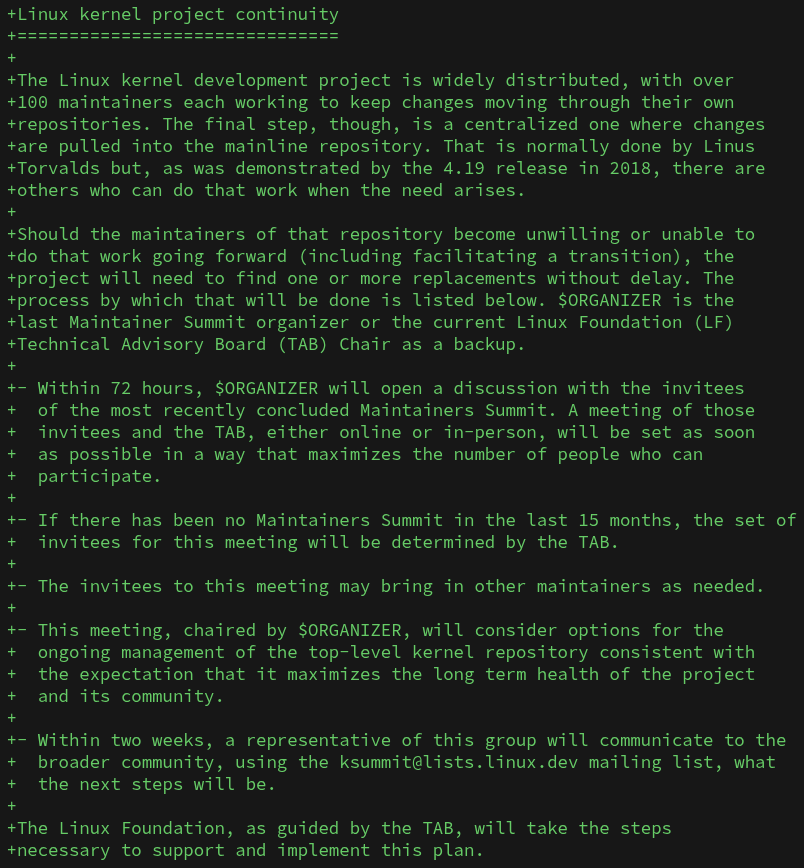

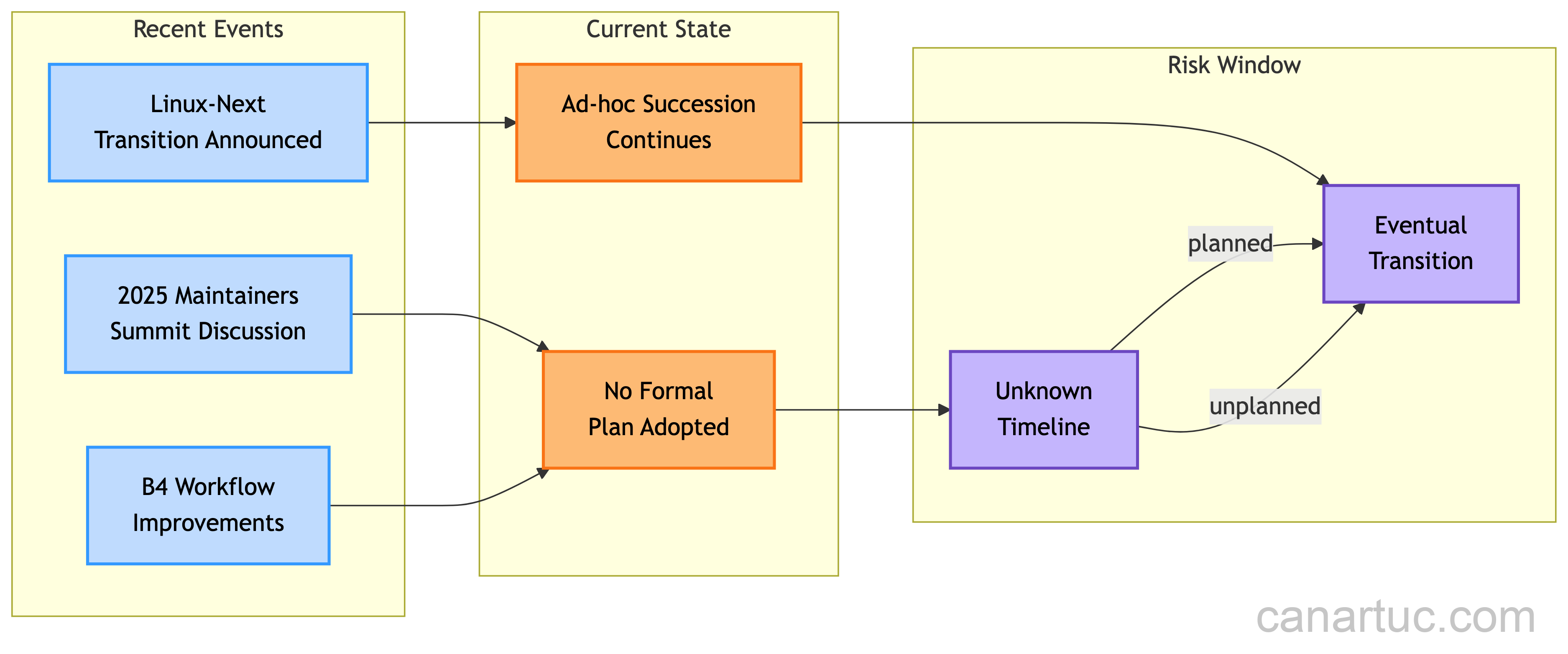

Last year, something shifted. The Linux kernel community quietly did something it had avoided for decades: they wrote down how to replace their leader. According to ZDNet, this plan was long overdue and essential for the project's sustainability.

The process isn't dramatic. There's no predetermined successor. No secret handshake. Just a formal, procedural framework that removes improvisation from the moment Torvalds steps aside. It's governance by document rather than by personality.

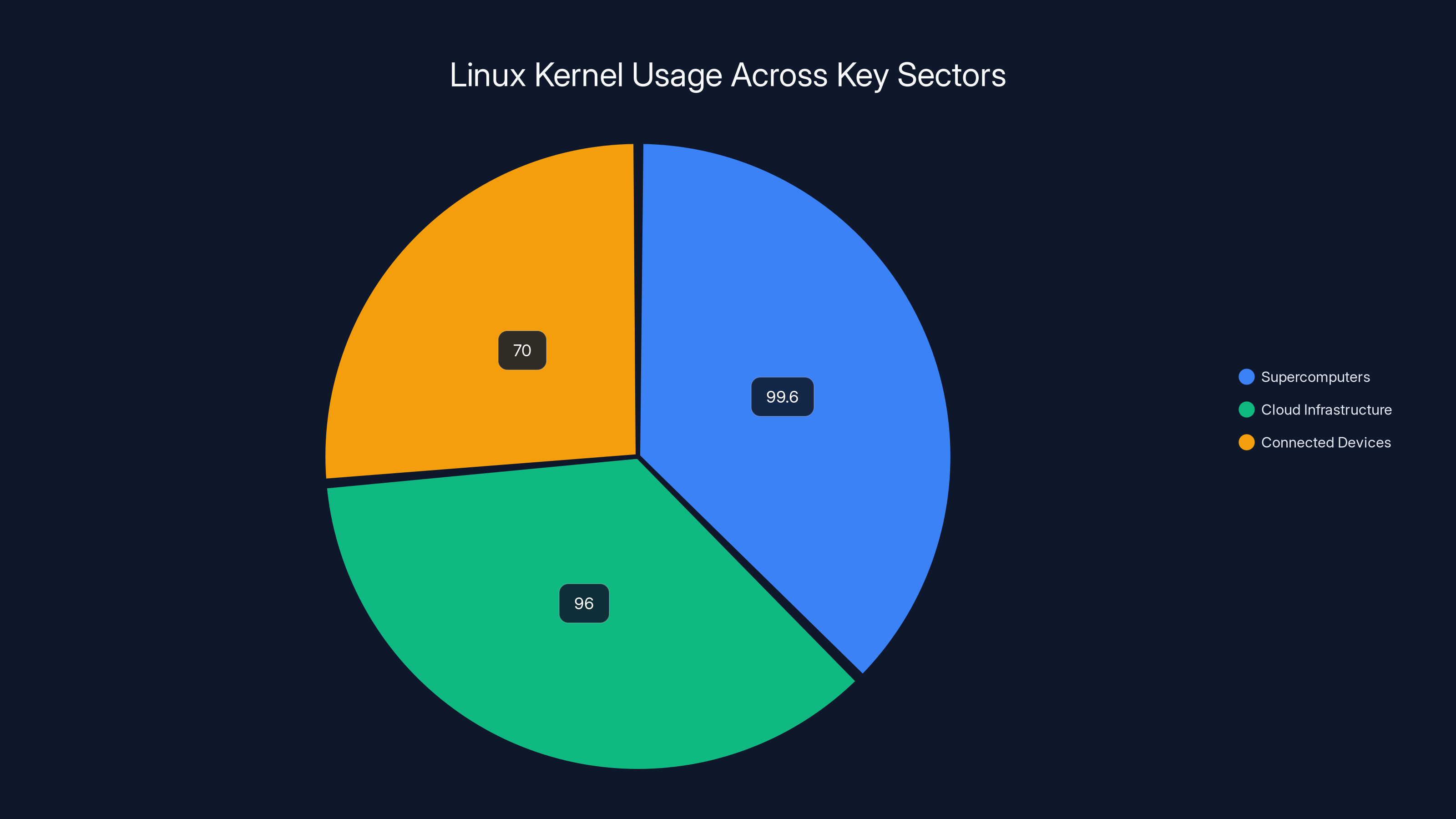

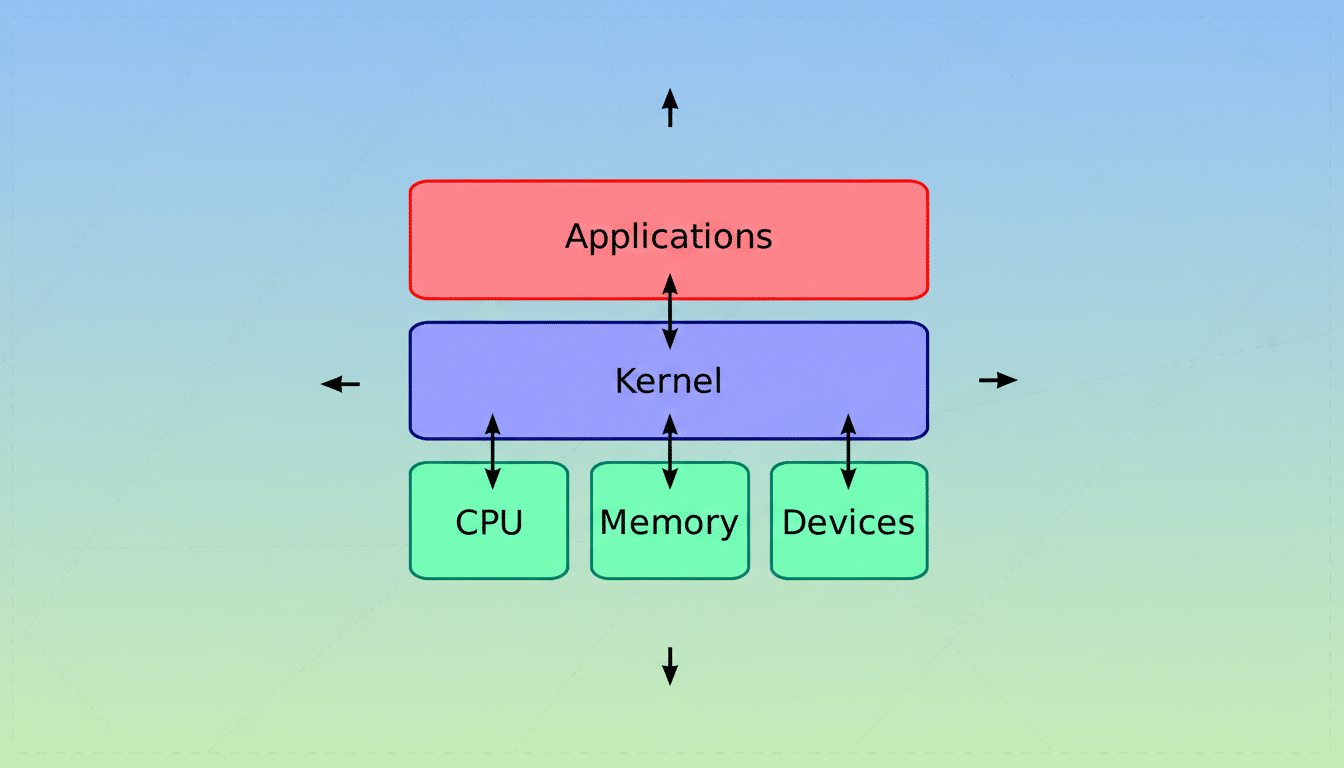

This matters more than you think. Linux runs on 99.6% of supercomputers, 96% of cloud infrastructure, and billions of connected devices globally. The kernel's stability directly impacts everything from banking systems to military networks. Formalizing its leadership succession isn't bureaucracy. It's risk management at scale.

Let's break down what changed, why it mattered so much, and what happens next.

TL; DR

- The Problem: Linux kernel had no formal succession plan after 30+ years under Linus Torvalds, creating a single point of failure

- The Solution: New governance framework establishes "Organizer" role and structured decision-making process for leadership transitions

- The Process: If Torvalds steps aside, an Organizer convenes kernel maintainers with 2-week decision window for selecting new leadership

- The Reality: Torvalds is 56 and likely not leaving soon, but this plan prepares the kernel for inevitable future transition

- The Impact: Protects world's most critical open source project from leadership vacuum that could destabilize cloud infrastructure, servers, and billions of devices

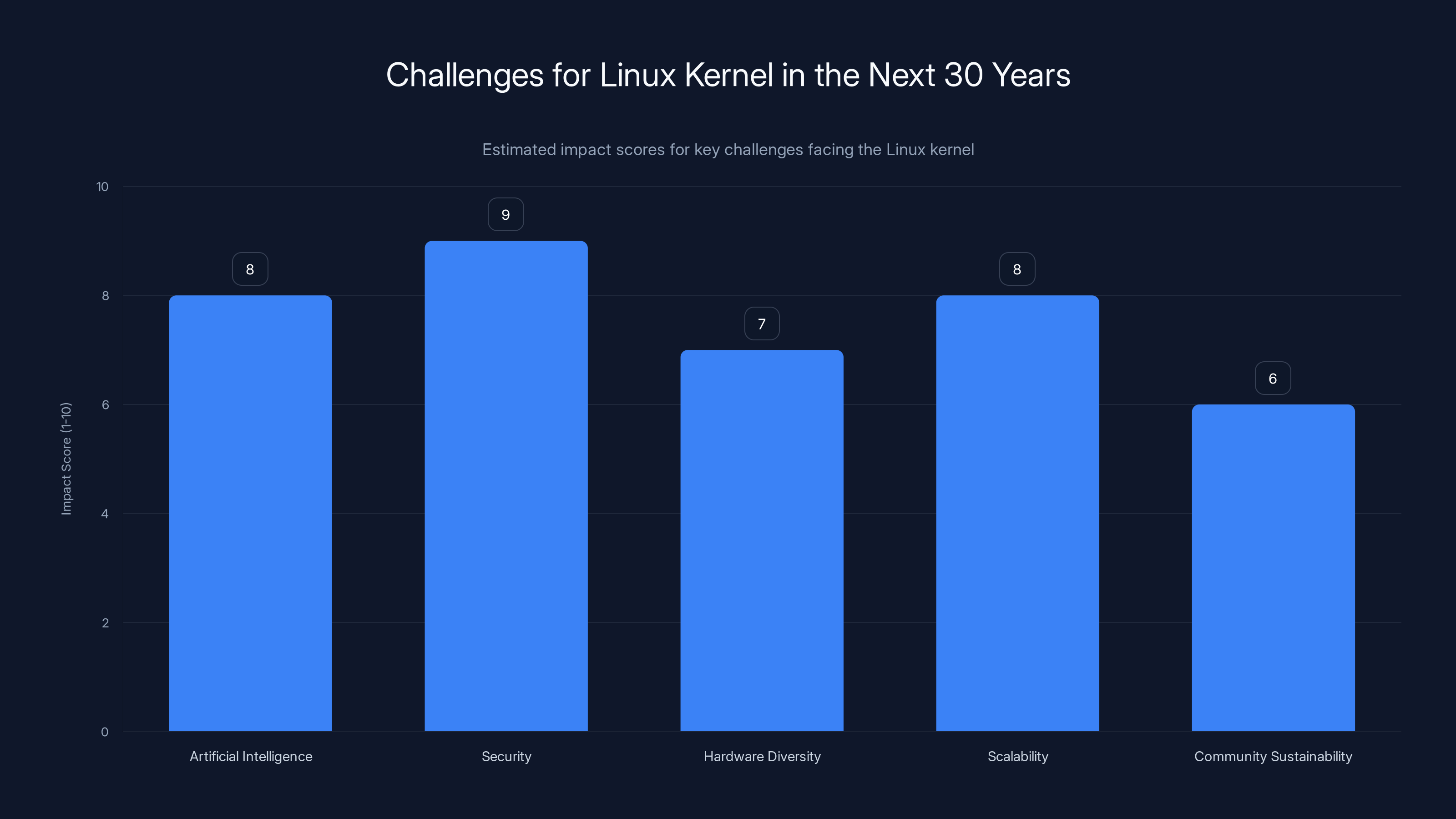

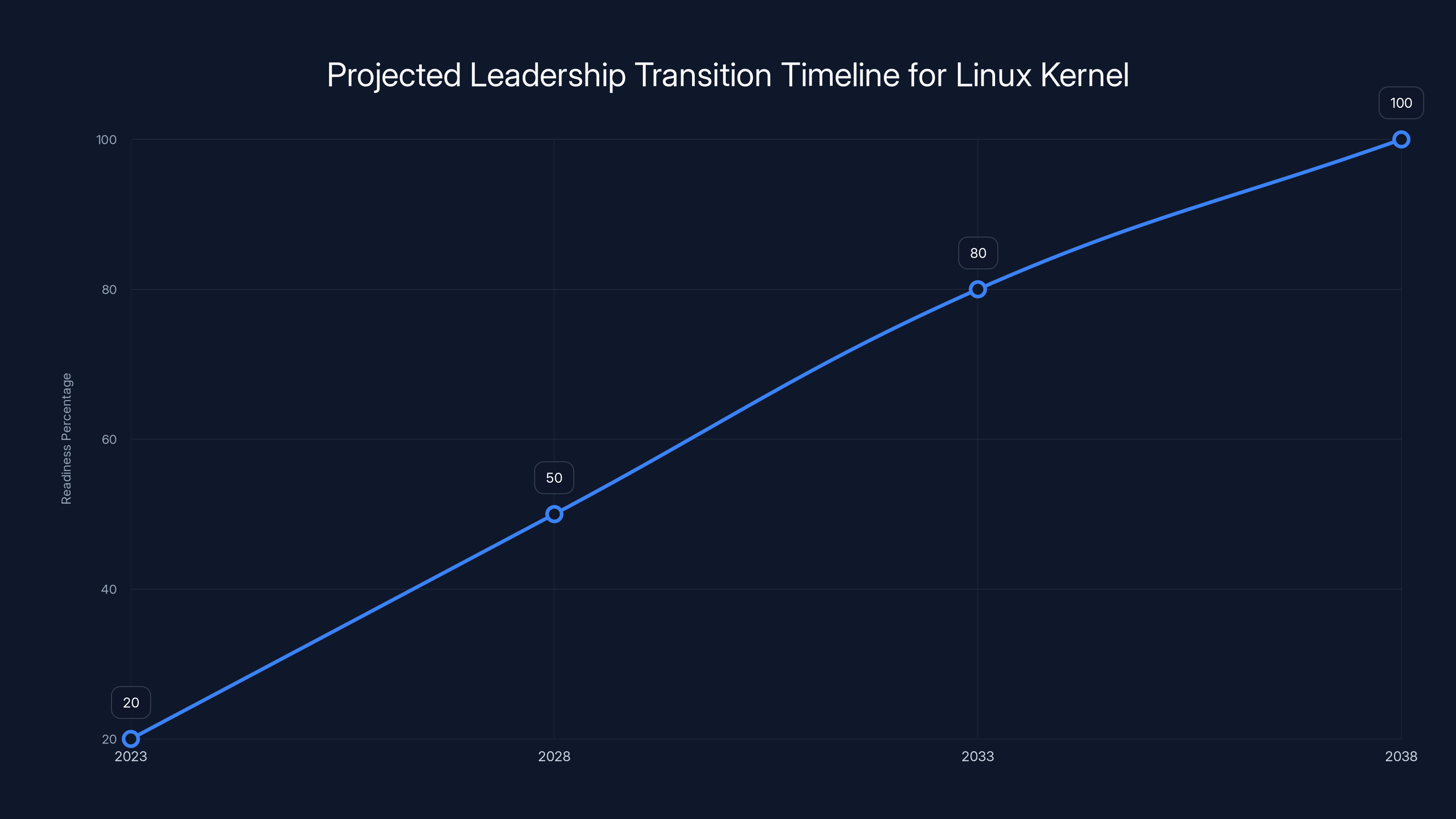

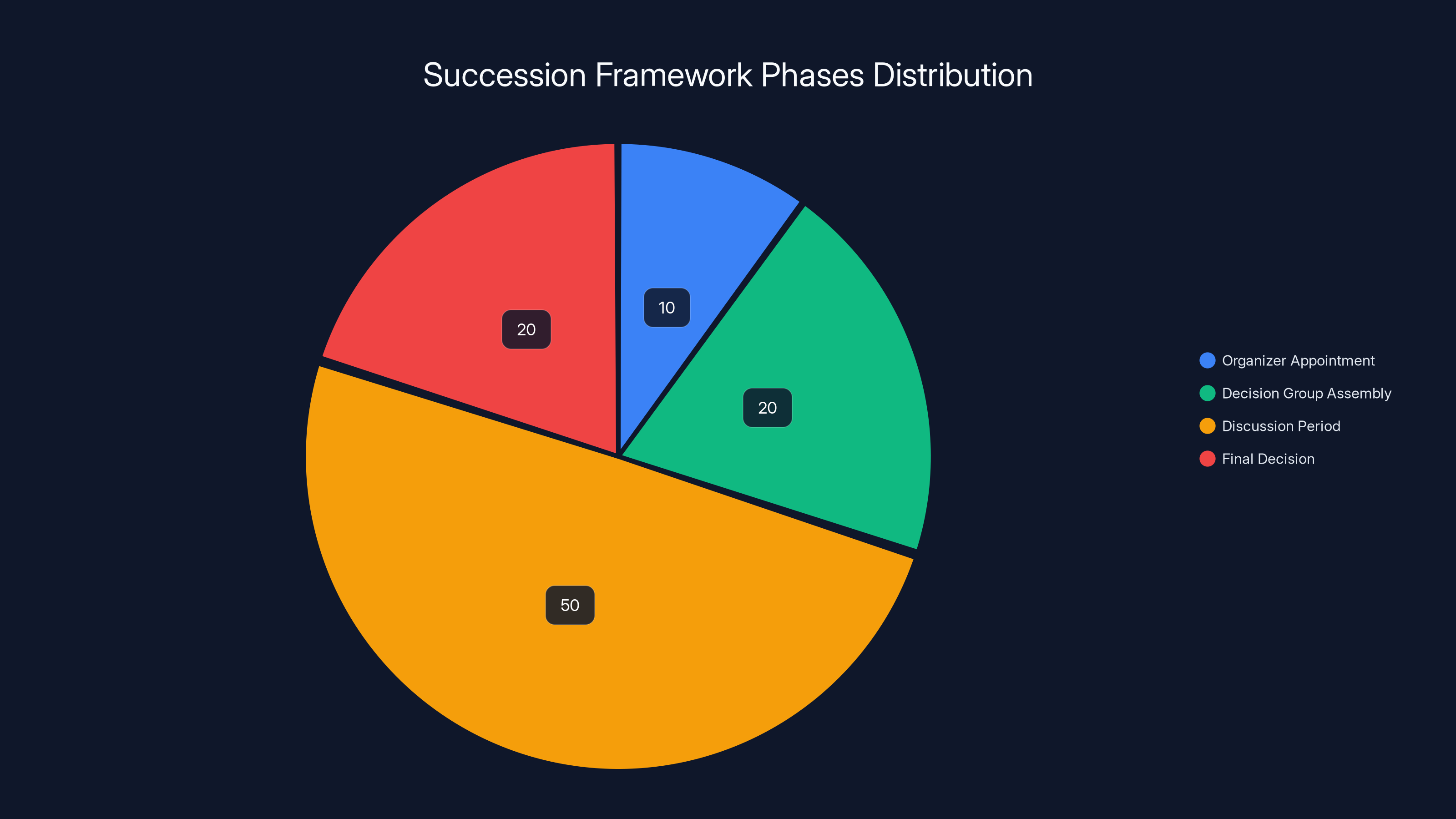

Security and AI adaptation are projected to have the highest impact on the Linux kernel's evolution over the next 30 years. (Estimated data)

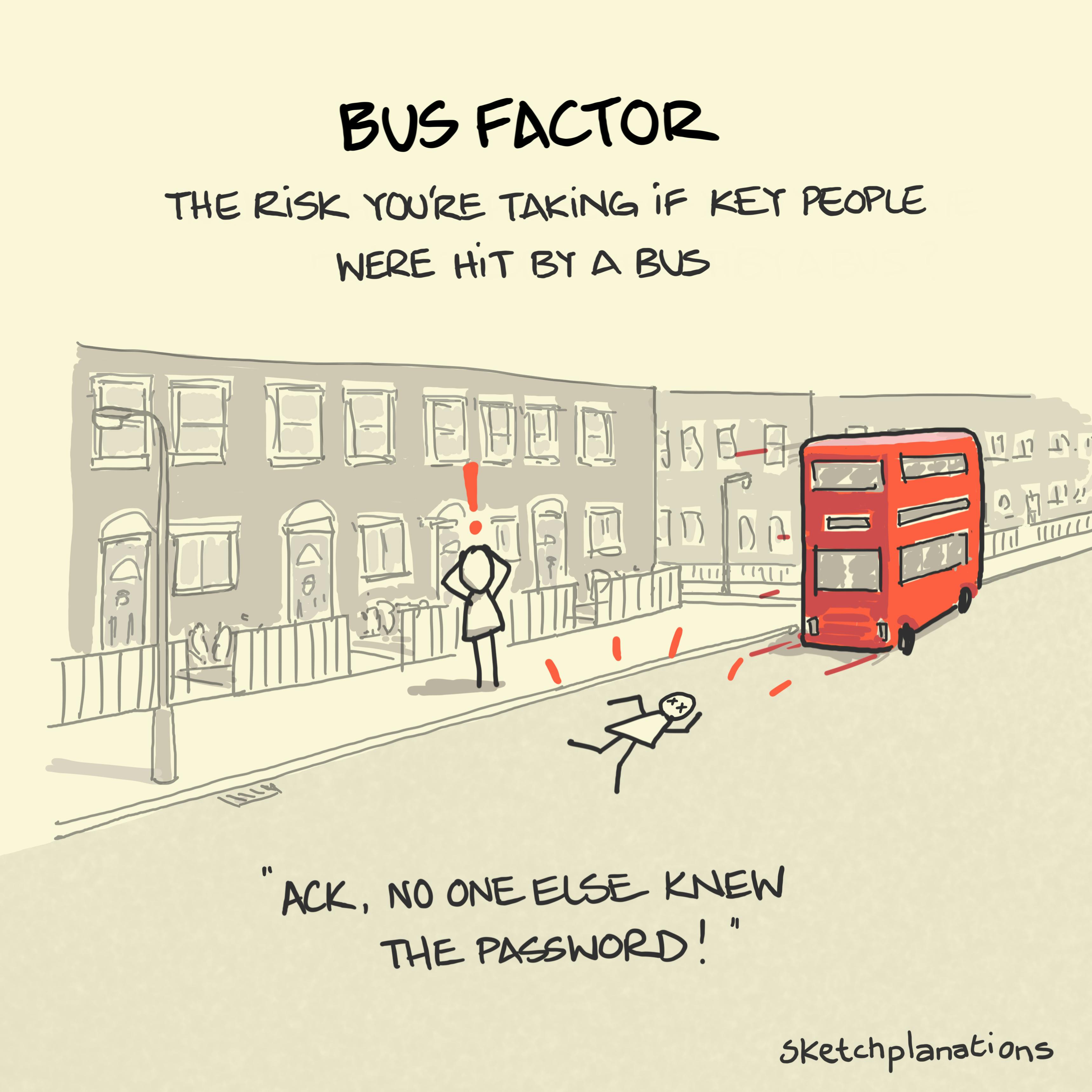

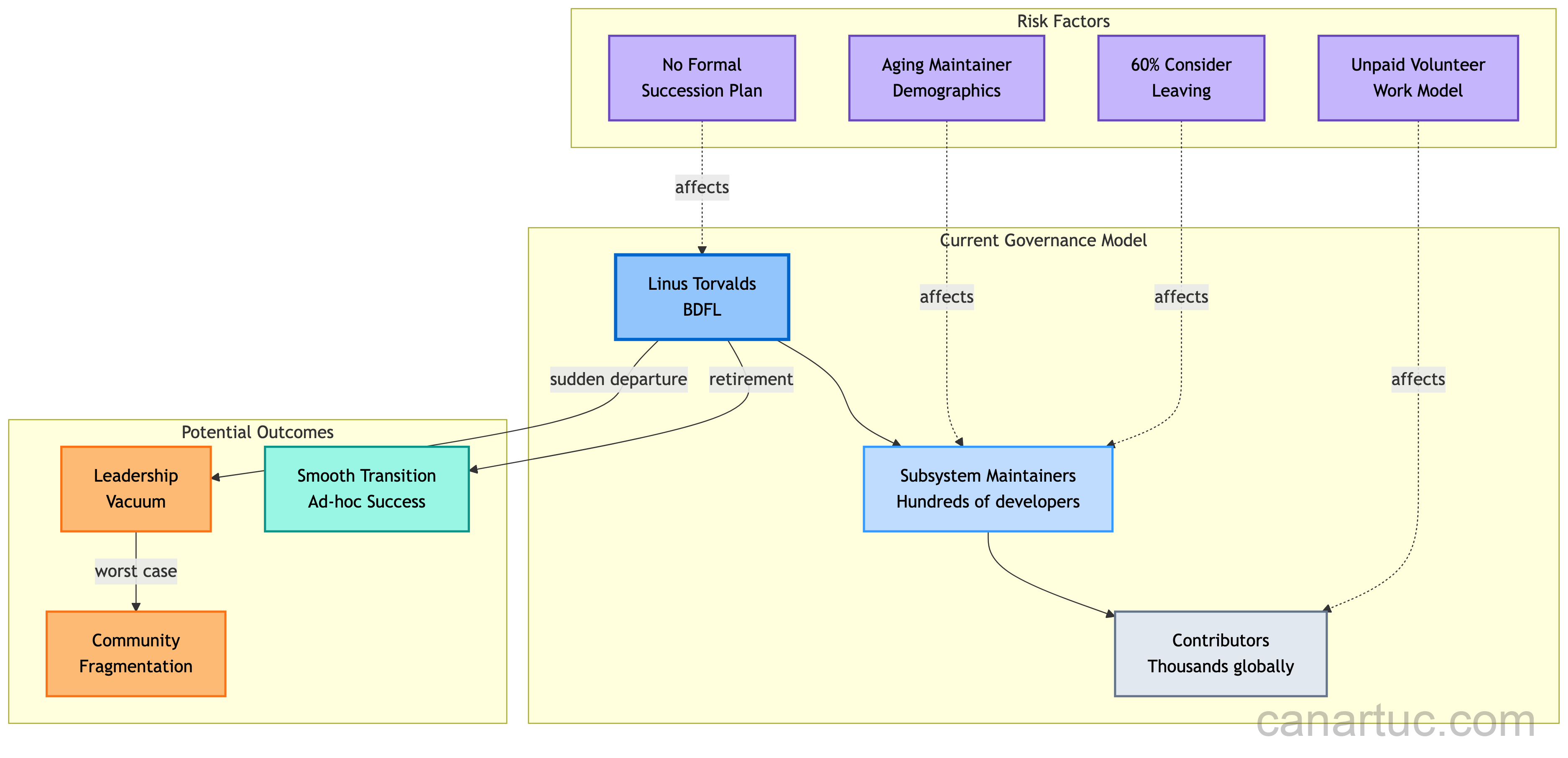

Why Linux Had a Bus Factor of Zero

In software engineering, there's a concept called the "bus factor." It's dark but practical: how many team members would need to be hit by a bus before the project collapses?

For Linux kernel, the number was one.

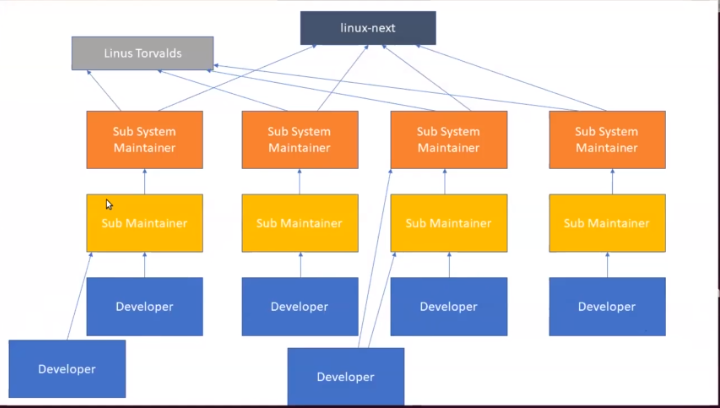

Linus Torvalds has been the sole decision-maker for every major kernel change since 1991. That's 33 years of centralized authority. While the kernel has thousands of contributors working on subsystems, device drivers, and architectural improvements, every final decision flows through one person.

This created a paradox. Linux thrived precisely because Torvalds made decisive calls that prevented the project from fragmenting into competing versions. He didn't allow feature bloat. He didn't tolerate technical debt masquerading as innovation. His authority kept the kernel lean and focused.

But that same authority created enormous risk.

What if Torvalds suffered a severe illness? What if he decided to step away tomorrow? What if he was incapacitated in an accident? The kernel wouldn't disappear, but leadership would vanish instantly. Thousands of pending decisions would stack up. Maintainers would argue about direction. The community would fragment.

Distributions like Ubuntu, Red Hat, and Debian had already solved this problem. They all maintain formal succession processes. Their maintainers didn't have to improvise when leadership changed. But the kernel itself—the foundation that every distribution depends on—had nothing.

This gap stayed unfilled for one simple reason: Linus wasn't going anywhere. At 56, he's healthy and active. He participates in kernel development regularly. He reviews patches. He makes decisions. The problem existed mostly in theory.

But theory matters in infrastructure. Cloud companies depend on kernel stability. Banks run on Linux. Governments use it. When something is that critical, "probably won't need it" isn't an acceptable succession plan.

The Growing Vulnerability: Aging Maintainers

Another reality the kernel community faced was demographic. Many of the most senior maintainers have been involved for 20+ years. They're aging. Some are approaching retirement.

These maintainers hold institutional knowledge that exists nowhere else. They remember early architectural decisions. They understand why certain trade-offs were made. They know which subsystems are fragile and which are rock-solid.

When these people eventually step back—whether gradually or suddenly—that knowledge doesn't transfer automatically. It gets lost.

Torvalds himself acknowledged this vulnerability in conversations with the maintainer community. He noted that while new capable developers emerge, the loss of experienced maintainers creates gaps in decision-making capacity. The community needed a way to preserve continuity.

The succession plan addresses this by creating a structured handoff process. Instead of relying on one person's judgment in a crisis, the framework distributes decision-making across experienced maintainers who've already proven themselves.

This is where the aging issue becomes clear. If Torvalds had stepped down tomorrow without a plan, the kernel community would have scrambled. There's no obvious successor. Leadership doesn't automatically transfer to the most senior maintainer or the newest innovator. It requires consensus among people who understand the kernel's philosophy and technical requirements.

The new process formalizes that consensus-building. It creates a structured framework instead of leaving it to chance.

Linux kernel powers 99.6% of supercomputers and 96% of cloud infrastructure, highlighting its critical role in global technology. Estimated data for connected devices.

How the New Succession Framework Works

Here's what happens if Linus Torvalds steps away. The process has several distinct phases.

Phase One: The Organizer Appointment

If Torvalds suddenly becomes unavailable—he retires, steps back for personal reasons, or becomes incapacitated—the first step is identifying an "Organizer." This isn't the new kernel leader. It's more like a facilitator.

The Organizer role goes to whoever organized the most recent Maintainers Summit. If that's not possible, the Linux Foundation Technical Advisory Board chair takes over.

This person's job is tactical, not strategic. They don't make the final decision. They structure the process so others can.

Phase Two: Assembling the Decision Group

The Organizer reaches out to kernel maintainers who attended the most recent Maintainers Summit. These are proven leaders. People who've demonstrated they understand kernel philosophy and can make sound technical decisions.

If too much time has passed since the last summit, the Linux Foundation advisory board helps identify which maintainers should participate. The framework allows flexibility here. It's not a fixed list. It's adaptive.

The key insight: the decision group is drawn from people the kernel community already trusts. No outsiders. No unknown variables. People with track records.

Phase Three: Structured Discussion Period

Once assembled, this group has two weeks to discuss the path forward. Two weeks might sound short, but it's not arbitrary. It's long enough to reach consensus through serious conversation. It's short enough to prevent drift and endless debate.

During this period, the group discusses what the kernel needs from its next leader. What qualities matter? What experience is essential? What vision should guide decisions?

They're not interviewing candidates. They're defining the role and figuring out who among them fits best.

Phase Four: Public Announcement

Once the group reaches agreement, they announce the decision publicly through established kernel mailing lists. The community learns the outcome. Discussion moves from behind-the-scenes to transparent.

This transparency matters. The kernel community is distributed globally. Developers across six continents contribute. They need to understand why a certain person is taking leadership. The public announcement ensures legitimacy.

Who Could Actually Become the Next Kernel Leader?

Here's the honest answer: nobody knows, because the plan doesn't pre-select a successor.

This might seem like a weakness. Shouldn't the kernel have a clear line of succession? In practice, no. Pre-selecting a successor creates dynamics that could fragment the community. People might choose sides. Factions could form. The predetermined successor might face resistance from people who wanted different leadership.

The open process avoids this. When the moment comes—potentially decades from now—the decision emerges from consensus among experienced maintainers. That consensus carries weight that any pre-selected person couldn't match.

But we can identify likely candidates by examining who currently holds influence.

Greg Kroah-Hartman is a clear candidate. He's been a kernel developer for 20+ years. He maintains several critical subsystems. He's deeply involved in kernel governance. He's respected across the community.

Darren Hart, another veteran developer, has significant influence in scheduling and power management. Thomas Gleixner, who oversees core kernel infrastructure, is another obvious possibility.

Shuah Khan leads kernel testing and quality assurance. That role makes her familiar with the kernel's health across platforms.

But here's the thing: none of these people are obviously "the one." That's intentional. The succession process will surface whoever is best suited at the moment a transition happens. Different times need different kinds of leadership.

Right now, the kernel needs someone who can maintain Torvalds' standard of quality while allowing more distributed decision-making. That's different from what the kernel might need in 10 years, when it could face entirely different technical challenges.

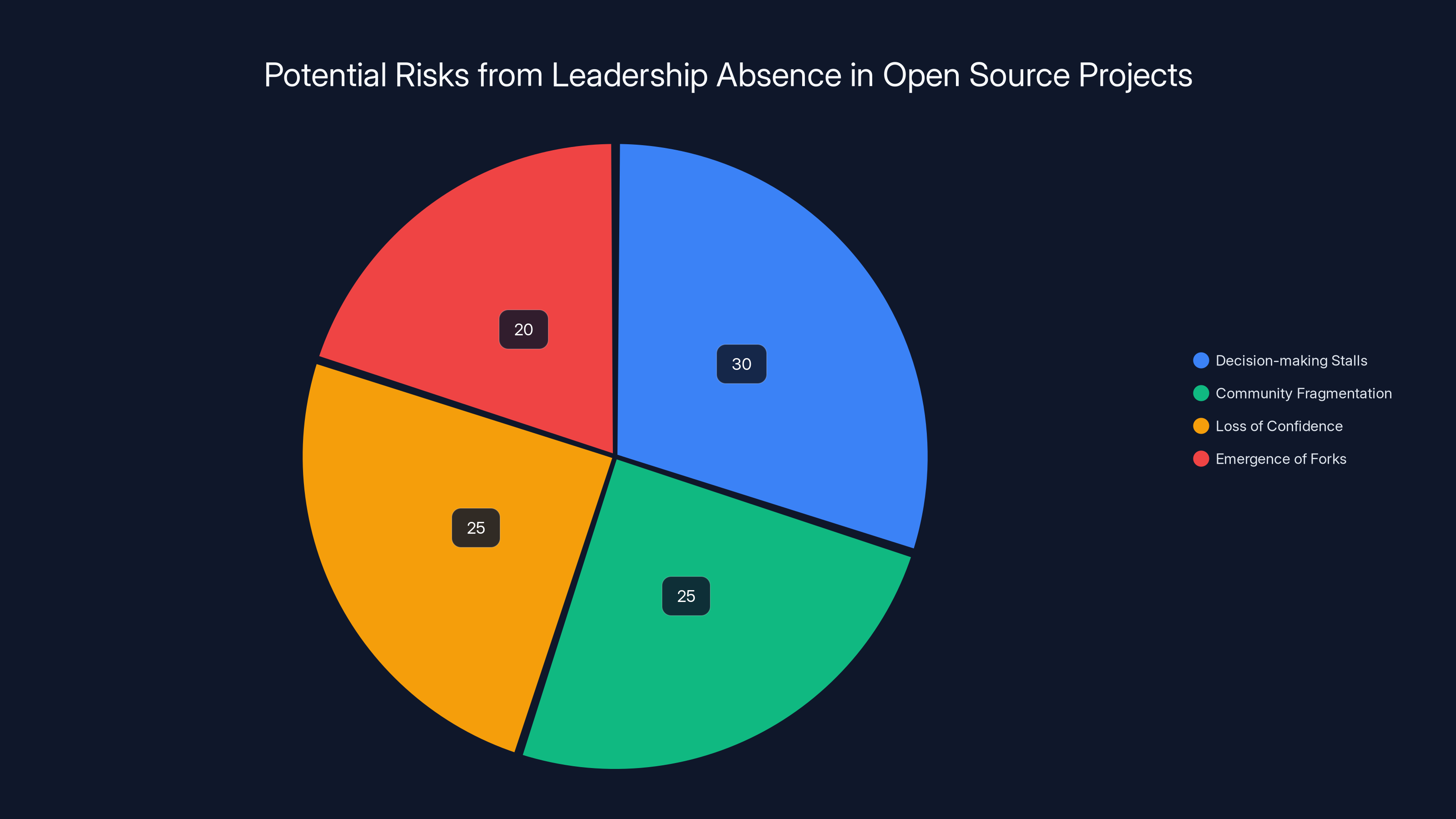

The Risk This Plan Actually Solves

Let's be specific about the danger. What actually happens if leadership suddenly vanishes?

First, decision-making stalls. Thousands of patches are submitted to the kernel every month. Major decisions require approval. If nobody has authority to approve changes, the queue backs up.

Second, the community fragments. Without clear leadership, different camps propose different directions. Some want to prioritize performance. Others want stability. Some push for new features. Others resist bloat. Without someone to make the final call, these discussions never resolve.

Third, people lose confidence. Companies that depend on kernel stability need assurance that the project is being managed responsibly. If leadership is ambiguous, enterprise adoption could suffer. Why commit resources to a platform where the future is uncertain?

Fourth, forks emerge. Some developers might decide the official kernel isn't going the direction they need. They split off, maintaining their own version. Now you have multiple kernels competing. The ecosystem fragments.

This happened before in open source projects. When My SQL was acquired by Sun Microsystems (which was later acquired by Oracle), some developers forked the project into Maria DB because they feared the corporate parent would prioritize profit over community. That fork succeeded because the open source community needed an alternative.

The Linux kernel doesn't need an alternative. It's too foundational. But the threat of fragmentation is real if leadership becomes unclear.

The succession plan doesn't eliminate these risks entirely. But it dramatically reduces them by creating clarity. Everyone knows the process. Everyone understands how the next leader will be chosen. That clarity prevents panic and improves confidence.

Estimated data shows the distribution of risks when leadership is absent in open source projects. Decision-making stalls and community fragmentation are the most significant risks.

Why This Plan Respects Linus's Legacy

Interestingly, the succession plan actually strengthens Torvalds' control, not weakens it. Here's why.

Right now, Torvalds' authority rests on personality and history. He can make decisions because people respect him personally. That's fragile. It depends on continued respect and participation.

With a formal succession plan, Torvalds' principles get institutionalized. The process the community will use to select his successor is based on values that Torvalds established. Quality matters. Technical merit matters. Patience matters. Humility matters.

When the next leader is chosen, they won't be chosen because they're the most charismatic or the best politician. They'll be chosen because they embody the technical and ethical standards that Torvalds established.

That's how legacy actually works. It's not about one person staying forever. It's about values outlasting the person.

The kernel community trusts Torvalds because he's made good decisions for 33 years. The community will trust his successor if that person continues making decisions by the same principles.

The succession plan ensures that happens by making the selection process transparent and values-driven.

How This Compares to Corporate Leadership Succession

For context, let's look at how traditional companies handle leadership transitions. They're messier than you'd think.

Apple's transition from Steve Jobs to Tim Cook was relatively smooth because Jobs prepared for it consciously. He trained Cook. He stepped back gradually. He established clear principles about decision-making. When Jobs died, Apple didn't panic because everyone understood the company's values.

But many corporate transitions are chaotic. HP has had multiple CEO changes with mixed results. Yahoo's leadership shifted repeatedly. Twitter's leadership changed when Elon Musk acquired it, creating massive internal upheaval.

The difference is planning. Companies that transition smoothly do so because they prepared deliberately. Companies that struggle usually didn't.

The Linux kernel's new succession plan puts the project in the prepared category.

What makes it interesting is that the kernel's approach is actually more democratic than most corporate succession planning. In corporations, the board chooses the new CEO largely in private. In the kernel, experienced maintainers discuss openly and reach consensus.

That's not inherently better. Consensus-driven decisions can be slower. But they carry more legitimacy in a volunteer-driven open source project.

The Technical Continuity Problem

Beyond leadership, there's a deeper continuity issue the kernel community has been grappling with: knowledge transfer.

Linus knows why certain architectural decisions were made. He remembers debates that happened 20 years ago. He understands the constraints that shaped the kernel's current structure. That knowledge is in his head.

If that knowledge disappears, future kernel developers might make decisions that contradict foundational principles. They might duplicate work that was already done and rejected for good reasons. They might introduce problems that could have been avoided.

Formalizing the succession process helps with this by requiring the decision group to meet and discuss. During those discussions, senior maintainers share context. Why does the kernel prioritize stability over innovation? Why do we reject certain features? What happened when we tried a different approach?

This institutional knowledge transfer happens naturally through conversation. The formal process creates the space for it.

It's not perfect. Some knowledge will still be lost. But it's better than the alternative, where leadership changes overnight with no knowledge-sharing opportunity.

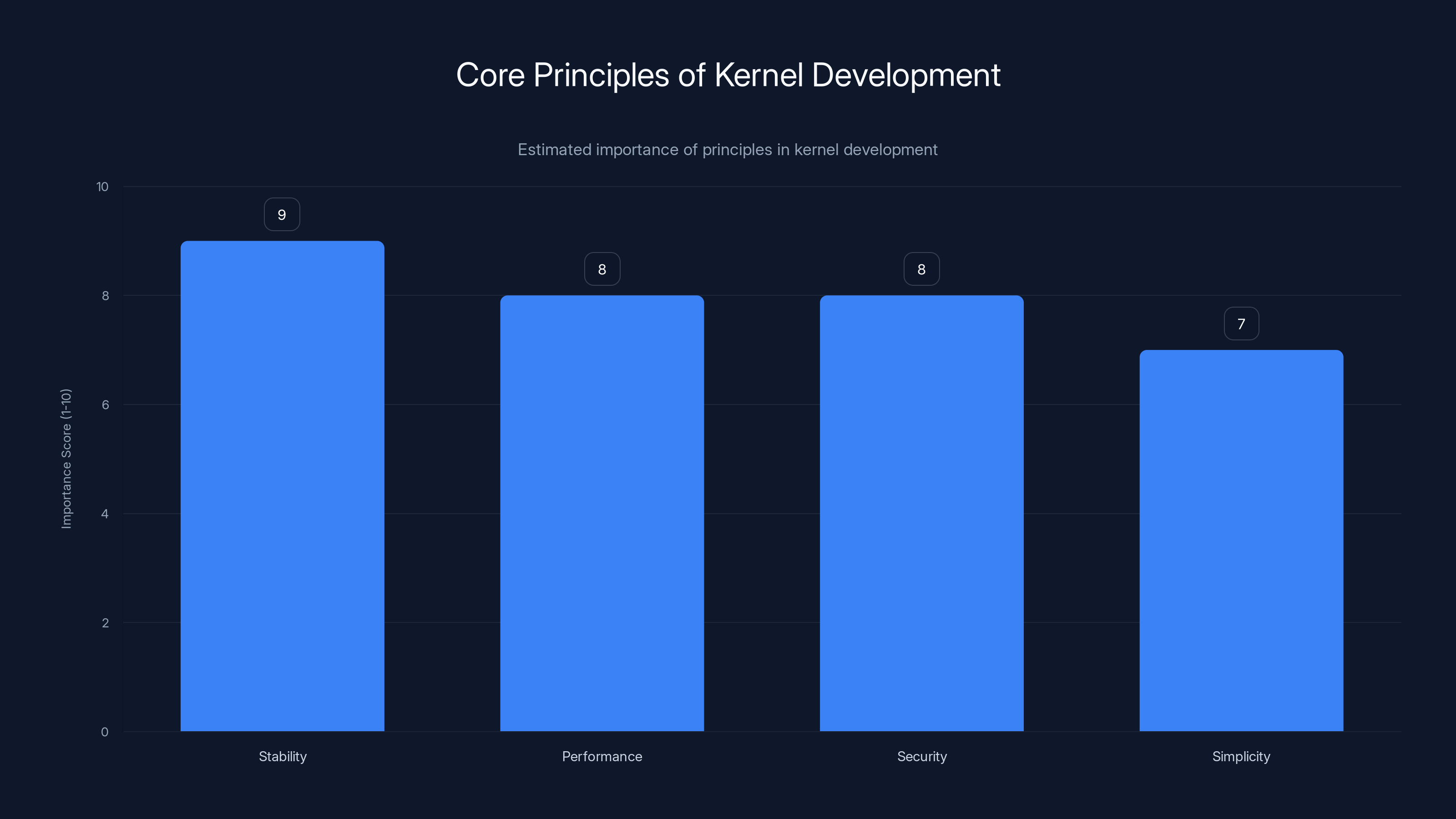

Stability is the most emphasized principle in kernel development, followed closely by performance and security. Estimated data based on typical kernel development priorities.

What Happens If the Process Fails?

Here's where the plan acknowledges reality: formal processes don't guarantee good outcomes.

If the decision group can't reach consensus in two weeks, what happens? The plan doesn't say explicitly. Presumably, the process extends, or the Linux Foundation advisory board steps in to mediate.

But the document acknowledges that a formal process doesn't eliminate conflict. The kernel community has strong opinions. People disagree about technical direction. Those disagreements won't disappear just because there's a succession plan.

The plan also doesn't prevent forks. If kernel maintainers are unhappy with the chosen successor, they could split off. The process makes that less likely, but not impossible.

What the plan does is reduce the likelihood of crisis. It replaces improvisation with structure. It replaces ambiguity with clarity.

Is that enough? For most scenarios, yes. For unusual situations, maybe not. But that's the best any succession plan can do.

The Broader Implications for Open Source Governance

The Linux kernel's succession plan is significant beyond just the kernel itself. It's a statement about how large open source projects can govern themselves.

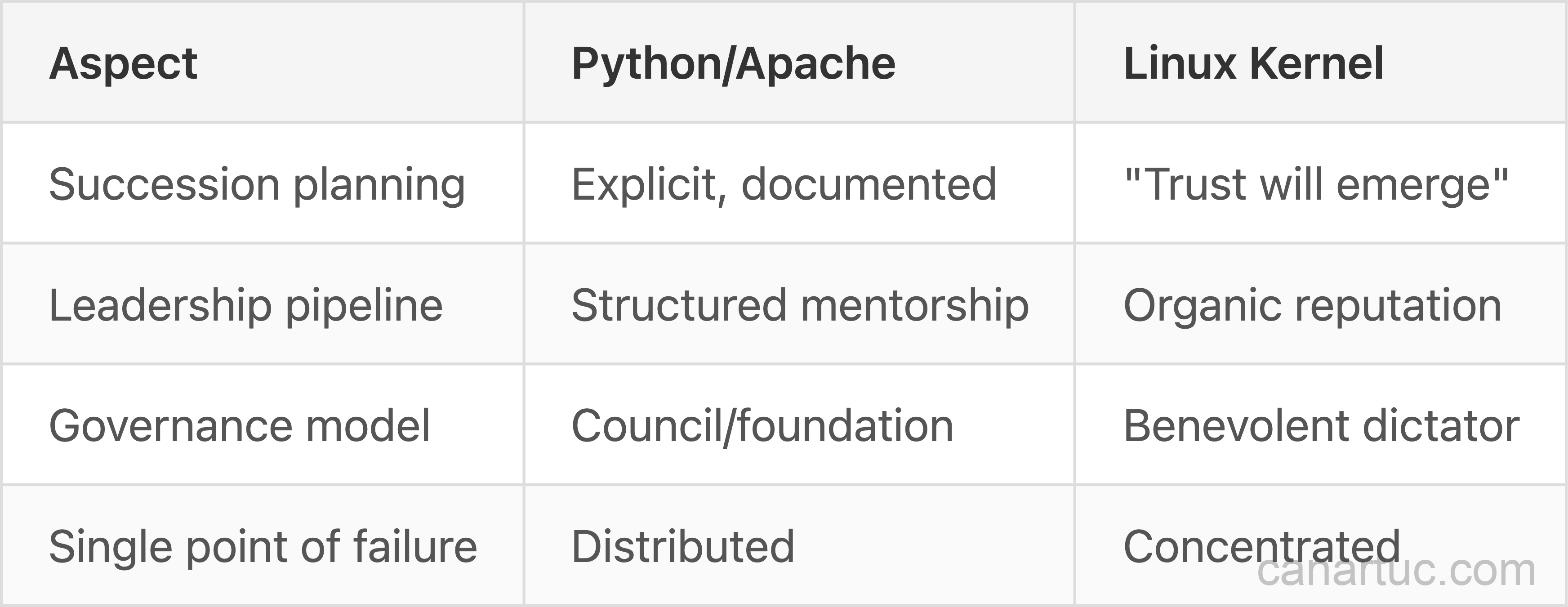

For decades, open source culture celebrated the "benevolent dictator" model. One person with vision, making decisive calls. It worked for Linux. It worked for Python under Guido van Rossum. It worked for other successful projects.

But sustainability requires transition planning. The kernel is finally acknowledging that explicitly.

Other major projects are watching. Python's governance has evolved significantly, with Python moving toward a steering council rather than a single benevolent dictator. Rust has always had distributed governance. Node.js operates through the Open JS Foundation with formal processes.

The kernel is following this trend, just more recently than others.

This shift reflects maturity. Early open source projects could afford informal governance. They had small communities. Now Linux affects billions of people. Formal governance isn't a restriction on freedom. It's a way to preserve the project's integrity while ensuring smooth transitions.

When Will This Plan Actually Be Used?

Honestly, probably not for a while.

Torvalds is 56. At that age, people often have 10-15 more years of active work ahead of them. He's healthy. He's engaged. He's not showing signs of stepping back.

When will he eventually step aside? That's unknowable. Maybe he'll work another 15 years. Maybe he'll retire next year to focus on other interests. Maybe he'll scale back gradually, working part-time before stopping entirely.

The beauty of having a plan is that it doesn't matter. Whenever it happens, the community is prepared.

In the meantime, the plan serves another purpose: it reassures stakeholders. Companies that bet billions on Linux infrastructure can point to formal governance as evidence that the project is sustainable. Universities that teach Linux can mention governance structures. Developers can feel confident that the project will outlast any individual.

That confidence matters. It affects adoption. It affects investment. It affects whether the best developers want to contribute.

So even if the succession plan isn't used for years, it's already serving its purpose.

Estimated data shows increasing readiness for leadership transition in the Linux kernel project, reflecting maturity and community-driven governance.

The Philosophical Shift in Open Source Leadership

When Linus Torvalds created Linux in 1991, the project was a hobby. He didn't expect billions of devices to run it. He didn't imagine entire economies depending on it.

Early leadership was personal. Decisions came from Linus's vision. The community trusted that vision.

Over three decades, Linux evolved from a hobby into infrastructure. The nature of leadership shifted.

Personal governance still matters. The next kernel leader will need to understand Linus's philosophy and respect the community's values. But that leader will also need to operate through more formal structures.

The succession plan reflects this evolution. It says: we trust individuals, but we also trust processes. Both matter.

This is a maturing of open source governance. The kernel isn't abandoning the principles that made it successful. It's building systems to preserve those principles when personnel changes.

What Developers Should Understand

If you're a kernel developer, or you depend on kernel stability, here's what this means.

First, the kernel's future is secure. There's a plan. It's transparent. It's been thought through by experienced people.

Second, leadership transitions will be more orderly. If something happens to Torvalds, the kernel won't experience a vacuum. There will be clear processes and clear leadership.

Third, the kernel's core values will be preserved. The next leader will be chosen because they understand and respect what makes the kernel work. That's not guaranteed to happen by default. The formal process helps ensure it.

Fourth, distributed decision-making might increase. One reason for formalizing succession is to recognize that the kernel has become too large and important for one person to handle alone. The next leadership might decentralize decisions more than Torvalds did.

Whether that's positive or negative depends on your perspective. Centralized decision-making prevented bloat. Distributed decision-making could accelerate innovation. The community will navigate that trade-off.

The Role of the Linux Foundation

The Linux Foundation didn't create this succession plan, but the organization facilitates it.

The foundation was created specifically to support Linux development. It funds infrastructure. It organizes the Maintainers Summit. It provides the Technical Advisory Board that helps oversee governance.

The foundation's role in succession planning is crucial. If the community can't reach agreement quickly, the advisory board helps mediate. That board includes representatives from major companies that depend on Linux, so they have skin in the game.

This isn't the foundation controlling the kernel. It's more like the foundation providing guardrails. The community makes decisions, but the foundation ensures those decisions happen within a reasonable process.

Companies like IBM, Intel, Google, and others fund the Linux Foundation because they recognize that Linux's success benefits them. They have a vested interest in kernel stability and governance.

So the succession plan isn't just a community document. It reflects the interests and commitments of organizations that depend on Linux at massive scale.

The structured discussion period takes up the largest portion of the succession process, highlighting its importance in reaching consensus. (Estimated data)

Lessons for Other Infrastructure Projects

The Linux kernel's succession plan offers a template for other critical infrastructure projects.

Consider databases. Postgre SQL has formal governance, but succession planning could be clearer. Mongo DB relies on corporate structure, which is different but also dependent on specific people.

Consider programming languages. Ruby has shifted toward more distributed governance as the creator stepped back. PHP has had complex governance transitions.

Consider cryptography libraries. Open SSL is so critical that succession planning is literally a matter of national security. The foundation that oversees it carefully plans for transitions.

The kernel shows that transparent, formal succession planning doesn't weaken projects. It strengthens them. It builds confidence. It ensures continuity.

Other critical projects should follow the same path.

The Unexpected Benefit: Clarifying Kernel Philosophy

One interesting side effect of formalizing the succession process is that it forced the community to articulate what the kernel is actually about.

What are the core principles that guide kernel development? Why do we reject certain features? What standards do we use to evaluate decisions?

These questions became explicit when the community was defining the succession process. They're not new questions. Kernel developers have always implicitly understood these principles. But making them explicit is valuable.

When the next leader is chosen, they'll be evaluated against these principles. That evaluation is more rigorous because the principles are now documented.

Over time, that documentation becomes the kernel's constitution. Future developers reference it. New maintainers learn it. The kernel's values transcend any individual.

That's how you preserve a project's soul through transitions.

Looking Forward: The Next 30 Years

The Linux kernel was created 33 years ago in Torvalds' college dorm. It's evolved into the most widely deployed operating system software in the world.

What challenges will it face in the next 30 years?

Artificial Intelligence: How does the kernel adapt as AI systems become more sophisticated? Do we need new abstractions for AI workloads? How does the kernel manage the power and memory demands of large models?

Security: As adversaries become more sophisticated, the kernel needs increasingly robust security. How do we balance security with performance? How do we verify that the kernel is actually secure?

Hardware Diversity: The kernel now runs on everything from tiny embedded systems to massive supercomputers. How do we maintain consistency across that range? How do we prevent fragmentation?

Scalability: As systems grow larger, kernel scalability becomes harder. How do we handle millions of threads? How do we optimize for systems with terabytes of memory?

Community Sustainability: Keeping the volunteer-driven community engaged and growing is crucial. How do we make kernel development accessible to new people?

The succession plan doesn't solve these problems directly. But it ensures that whoever is leading the kernel can focus on solving them rather than worrying about governance uncertainty.

The Human Element: Why This Matters Emotionally

There's something both sad and beautiful about formalizing a succession plan for a project that's been so tied to one person's vision.

Linux became what it is because Linus Torvalds cared deeply about doing things right. He was willing to make decisions that unpopular if they were correct. He refused to compromise on quality. He treated the kernel as something sacred.

That vision created an operating system that works. Not perfectly, but remarkably well for something so complex.

Now the community is acknowledging that someday, Linus will step back. When that happens, they want someone with similar values. Someone who cares about doing things right. Someone willing to say no to bad ideas.

The succession plan is a way of saying: we want to preserve what made this project great. We're going to do that explicitly. We're not going to leave it to chance.

That's not morbid. It's hopeful. It's a statement that the community believes in the kernel's future even after Torvalds is gone.

FAQ

What is the Linux kernel succession plan?

The Linux kernel succession plan is a formal governance document that outlines how leadership will be selected if Linus Torvalds steps down or becomes unavailable. Rather than relying on informal processes or personality-driven decisions, the plan establishes a structured procedure where an "Organizer" convenes experienced kernel maintainers who then have two weeks to reach consensus on a path forward. This process ensures that leadership transitions happen through consensus among proven technical leaders rather than through improvisation during a crisis.

Why did the Linux kernel community create a succession plan?

The Linux kernel operated for 33 years with zero formal succession plan despite being the most critical piece of software infrastructure globally. This created a significant risk: if Linus Torvalds became unavailable, the kernel would lack clear leadership and decision-making authority. Additionally, many experienced kernel maintainers are aging, and the community recognized that without formal transition processes, institutional knowledge could be lost. The plan was created to mitigate these risks and ensure the kernel's stability regardless of what happens to any individual leader.

How does the succession process actually work step by step?

The process begins when the "Organizer" is appointed, typically whoever organized the most recent Maintainers Summit or the Linux Foundation Technical Advisory Board chair. The Organizer then identifies and convenes kernel maintainers who attended recent summits. This group has two weeks to discuss and reach consensus on a path forward for kernel leadership. Once agreement is reached, the decision is announced publicly through established kernel mailing lists, ensuring transparency and legitimacy across the global developer community. The entire process prioritizes consensus and documented discussion over individual decision-making authority.

Who would likely become the next Linux kernel leader?

The succession plan doesn't pre-select a successor, which is intentional to avoid factionalism. However, likely candidates include developers like Greg Kroah-Hartman (20+ year veteran maintaining critical subsystems), Darren Hart (key contributor to scheduling and power management), Thomas Gleixner (core infrastructure maintainer), and Shuah Khan (testing and quality assurance lead). The actual successor will emerge from consensus among experienced maintainers at the time of transition, ensuring that whoever is chosen has broad community support and respect.

What happens if the decision group can't reach consensus?

The formal plan doesn't explicitly define what happens if consensus can't be reached within two weeks, though presumably the discussion period could extend or the Linux Foundation Technical Advisory Board could intervene. This represents a potential weakness in the plan: formal processes don't guarantee consensus. However, the existence of a structured process is still superior to having no process at all, as it reduces the likelihood of leadership vacuum and provides a framework for resolving disagreements rather than allowing them to spiral into fragmentation.

When will this succession plan actually be used?

Linux Torvalds is currently 56 years old and actively engaged in kernel development, so the succession plan likely won't be needed for many years. However, having the plan in place now serves important purposes: it reassures companies and organizations that depend on Linux that the project has formal governance ensuring continuity, it provides psychological confidence to the developer community that the kernel will outlast any individual, and it gives the community time to prepare for eventual transitions. The plan's existence matters even if it's not activated for a decade or more.

How does this succession plan compare to how other projects handle leadership transitions?

The Linux kernel's approach is relatively democratic compared to corporate succession planning, where boards choose new CEOs largely in private. It's also more formalized than many open source projects that rely on personality-driven leadership. The plan mirrors governance structures already proven by distributions like Ubuntu, Debian, and Red Hat. It represents a maturation of open source governance, balancing the benefits of individual vision with the stability of formal processes—acknowledging that while talented individuals drive innovation, institutions ensure sustainability.

What does this plan mean for people who depend on Linux?

For users, developers, and organizations that depend on Linux, the succession plan provides assurance that the kernel will continue operating effectively even after Torvalds steps aside. It reduces the risk of leadership vacuum that could fragment the project or slow decision-making. It also signals that the kernel community takes sustainability seriously, which increases confidence in Linux as a long-term platform for critical infrastructure. For enterprise customers especially, knowing that governance is formalized rather than dependent on one person's continued participation is significant.

Does this succession plan change how the kernel operates today?

Not immediately. Torvalds remains the benevolent dictator, and decision-making processes haven't fundamentally changed. The plan is preparatory rather than immediately operational. However, by documenting the kernel's core values and decision-making principles, it may influence how future decisions are made and how new maintainers are recruited and trained. The explicit articulation of what makes kernel leadership work—technical excellence, commitment to quality, willingness to make unpopular decisions—could subtly shift the culture toward these values.

Why doesn't the plan pre-select a successor?

Pre-selecting a successor would create dynamics that could fragment the community. Different factions might support different candidates. The predetermined successor might face resistance from people who wanted different leadership. Choosing someone after a transition happens—through consensus among experienced maintainers—ensures broader acceptance. The plan ensures that whoever is chosen has community support, which is more important than having a predetermined name. This approach also allows the community to choose the type of leadership that's needed at the moment of transition, which might differ from what was needed decades earlier.

What role does the Linux Foundation play in kernel succession?

The Linux Foundation provides infrastructure, funding, and organizational support for the kernel project through the Maintainers Summit and the Technical Advisory Board. In succession planning, the foundation's TAB (which includes representatives from major companies that depend on Linux) helps mediate if the community can't reach quick consensus. The foundation doesn't control kernel decisions, but it provides guardrails and ensures processes happen within reasonable timeframes. This arrangement balances community autonomy with the practical need for some institutional structure in a project of this scale and importance.

Conclusion: How One Document Changes Everything

The Linux kernel's succession plan isn't dramatic. It's not a technological breakthrough. It's just words on a document describing a process.

But those words represent something significant: the recognition that even the most successful open source projects are mortal. That even visionary leaders eventually step aside. That institutions outlast individuals.

For 33 years, Linux thrived because one person made good decisions consistently. That was strength and weakness simultaneously. Strength because Linus prevented fragmentation and maintained standards. Weakness because it created a single point of failure.

The succession plan addresses that weakness without abandoning the strengths. It says: we're going to preserve the values and decision-making principles that made this project great, and we're going to do that through a transparent, community-driven process.

That's how institutions persist. Not through one great person staying forever, but through values surviving transitions.

Linux now has those values documented. The community has a process. The next leader will be chosen based on criteria that the current community understands and respects.

When Torvalds eventually steps aside—whether in five years or fifteen—the kernel will have leadership. It will have direction. It will have continuity.

For a project that billions of people depend on, that's not just governance. It's insurance. And it was definitely worth the time to document.

The Linux kernel has spent 33 years building something that works. Now it's spending time ensuring that something works for another 33 years. That's maturity. That's wisdom. That's how you make something that outlasts everyone involved in creating it.

And maybe that's the most fitting legacy Linus Torvalds could leave: a project robust enough that it doesn't depend on any one person, yet true enough to its founding principles that it will feel the same for the next generation of developers.

Key Takeaways

- Linux kernel finally formalized leadership succession process after 33 years of operating under Linus Torvalds with no written plan for transitions

- The new process establishes an 'Organizer' role to convene experienced maintainers who have two weeks to reach consensus on leadership direction

- Linux had a bus factor of zero—if Torvalds suddenly became unavailable, the entire project lacked clear decision-making authority

- The succession plan preserves kernel values and decision-making principles by requiring future leaders to be chosen based on community consensus among proven technical leaders

- This governance shift reflects maturation of open source projects—balancing individual vision with institutional sustainability for critical infrastructure that billions depend on

![Linux Kernel Succession Plan After Linus Torvalds: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/linux-kernel-succession-plan-after-linus-torvalds-what-you-n/image-1-1769967351942.jpg)