Macaque Facial Gestures Reveal Neural Codes Behind Nonverbal Communication

When you tell your kid "no" to ice cream before dinner, the actual message depends almost entirely on your face. A smirk says "maybe if you ask later." A stern frown says "absolutely not, and don't ask again." The words are the same. The context—encoded entirely in your facial expression—flips the meaning on its head.

For years, neuroscientists struggled to understand how this happens at the neural level. We've made incredible progress mapping how brains process speech, but facial expressions? That remained a puzzle. A recent study from the University of Pennsylvania finally cracked it open, and the findings are rewriting what we thought we knew about how brains generate the faces we make.

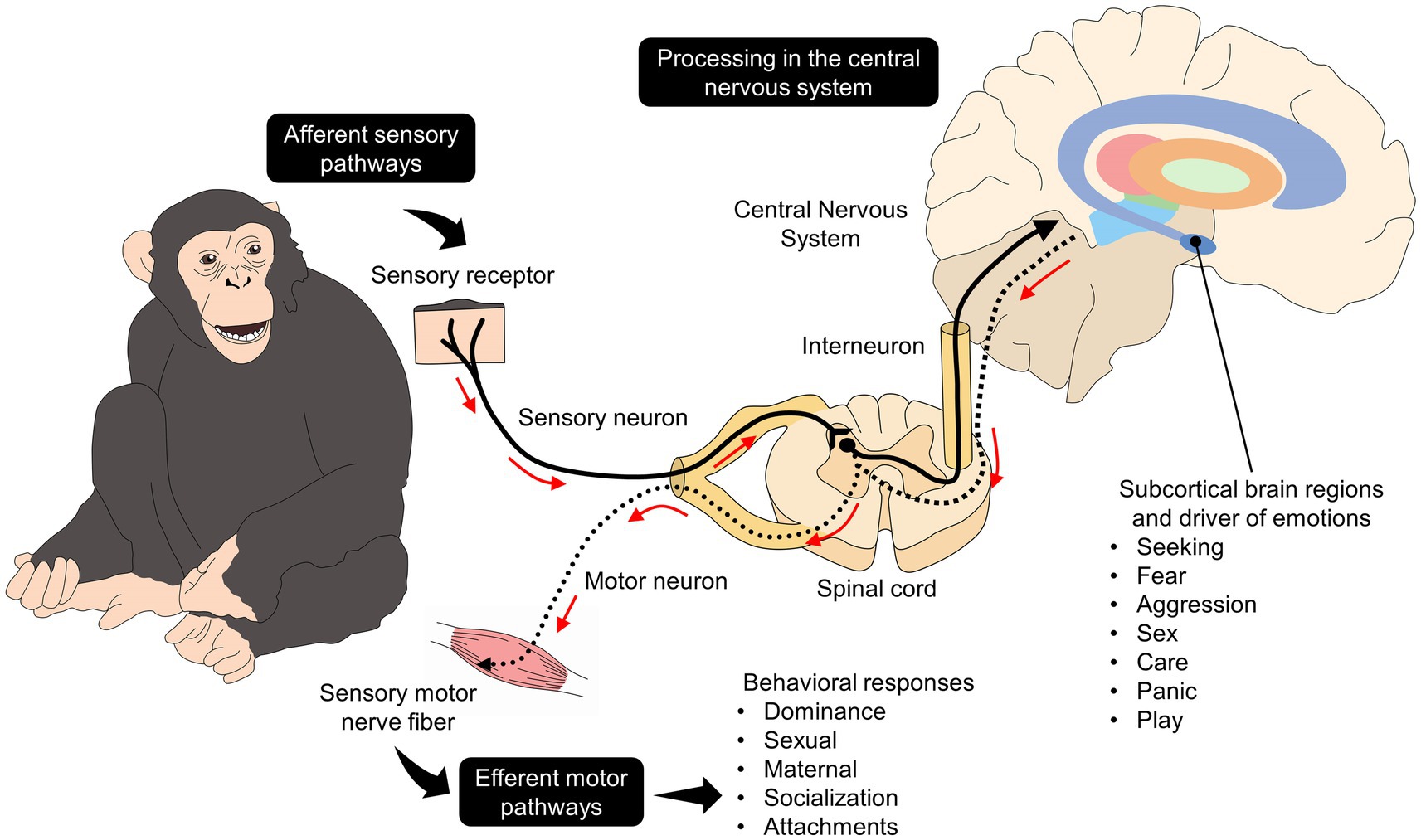

The research marks the first time scientists implanted micro-electrode arrays directly into primate brains to record from dozens of neurons simultaneously while they produced facial gestures. What they found challenges a fundamental assumption that neuroscientists have held for decades: that different brain regions specialize in different types of expressions. Instead, the brain uses something far more sophisticated. It layers information across multiple regions using different neural codes, creating a hierarchy of control that separates what you're expressing from how you express it.

This matters more than academic neuroscience. Scientists are already building neural prostheses to help stroke and paralysis patients communicate again. Understanding how brains generate facial expressions could eventually let these devices decode not just words, but the emotional nuance that makes communication human. It's the difference between a prosthetic that lets someone say "I'm happy" and one that lets them smile while saying it.

TL; DR

- The Study: Researchers implanted micro-electrode arrays in macaque brains for the first time, recording from dozens of neurons as they produced facial gestures

- The Surprise: All four key brain regions involved in facial expressions participated in every type of gesture, contradicting the long-held theory of regional specialization

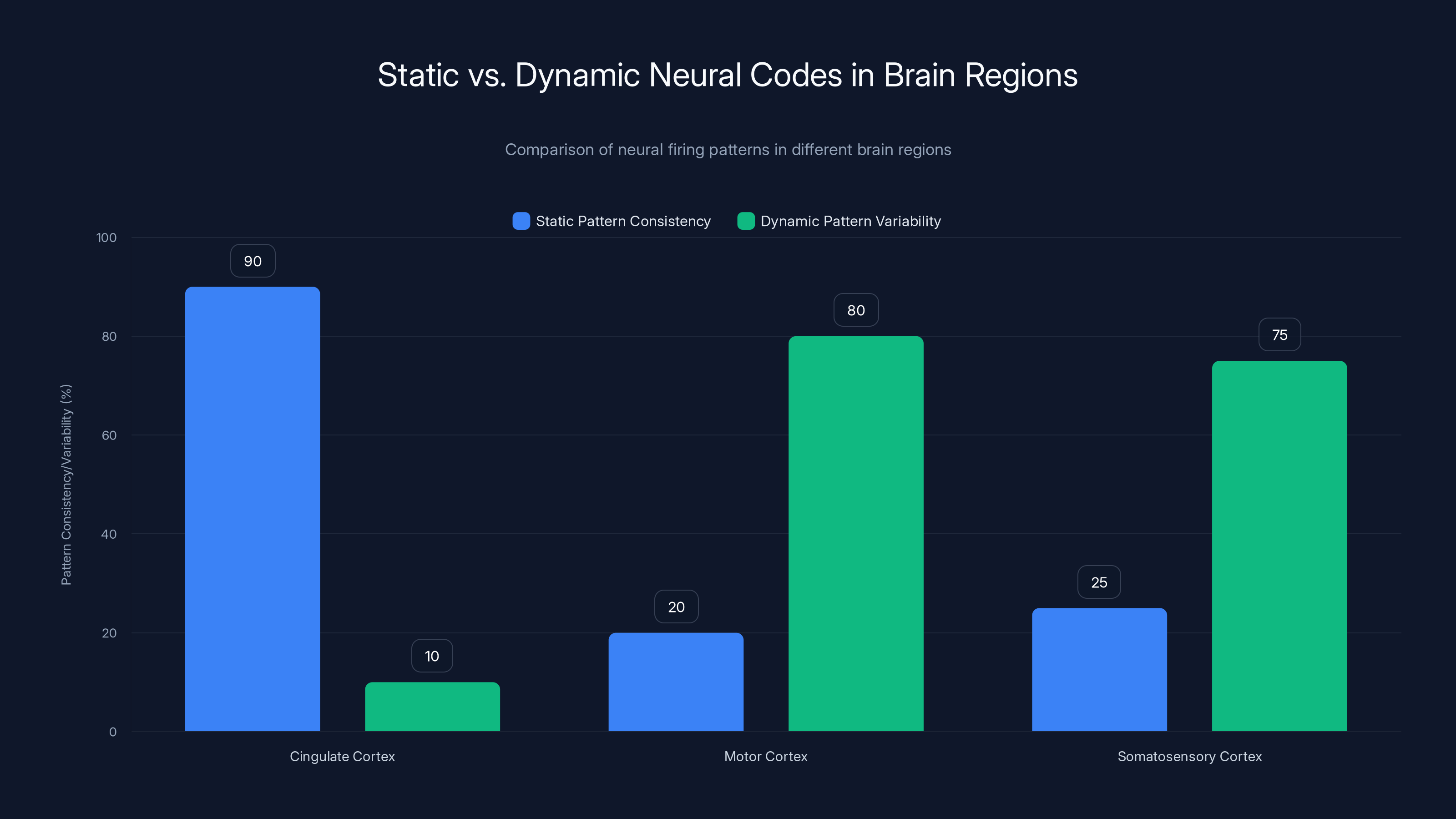

- The Code: Different brain areas use different neural codes—static patterns in the cingulate cortex for the social context, dynamic patterns in motor areas for the actual muscle movements

- The Implication: Future neural prostheses could decode not just speech from brain signals, but facial expressions and emotional intent as well

- The Timeline: This foundational work may take 5-10 years to translate into clinical applications for patients with paralysis or stroke

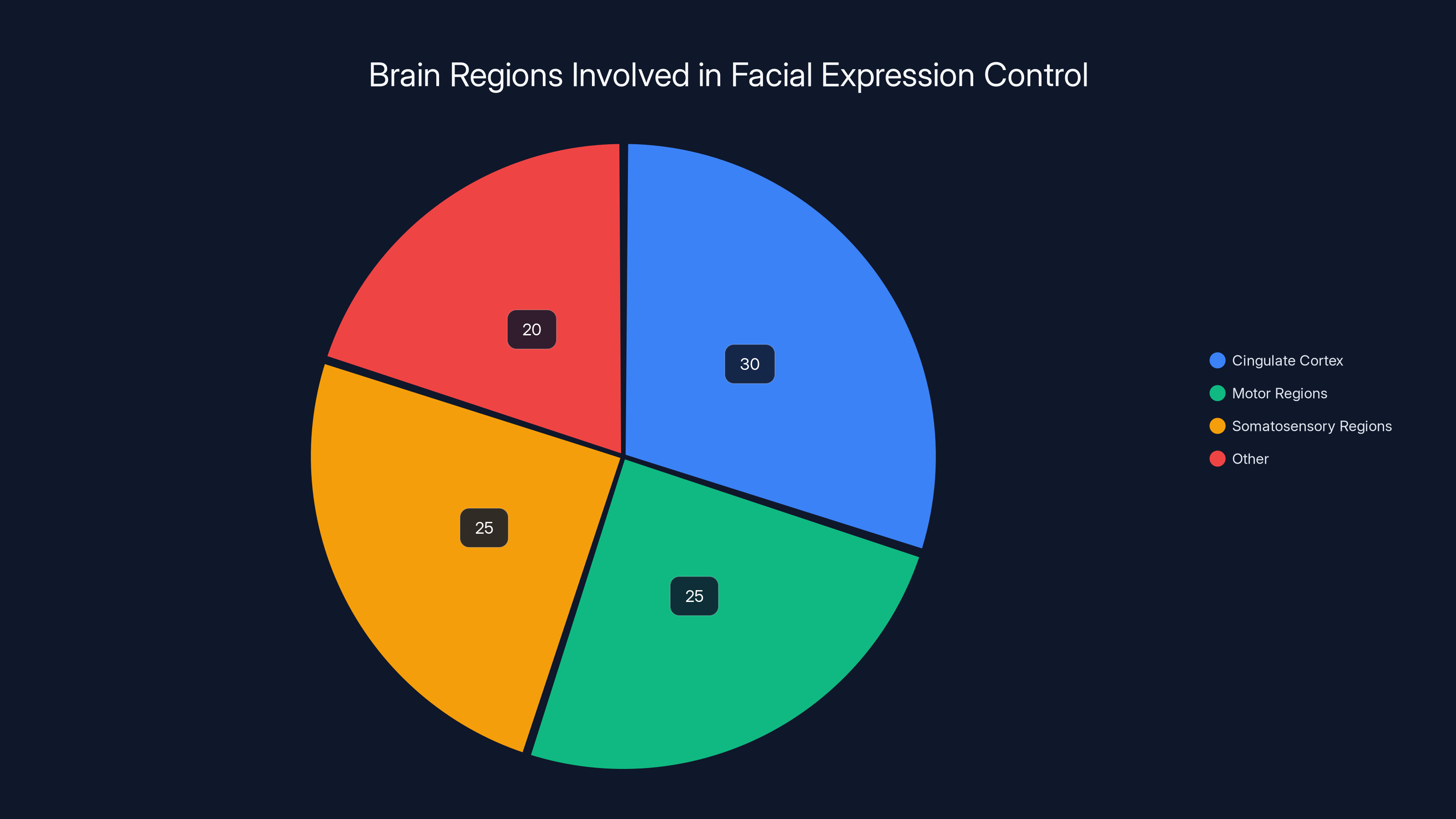

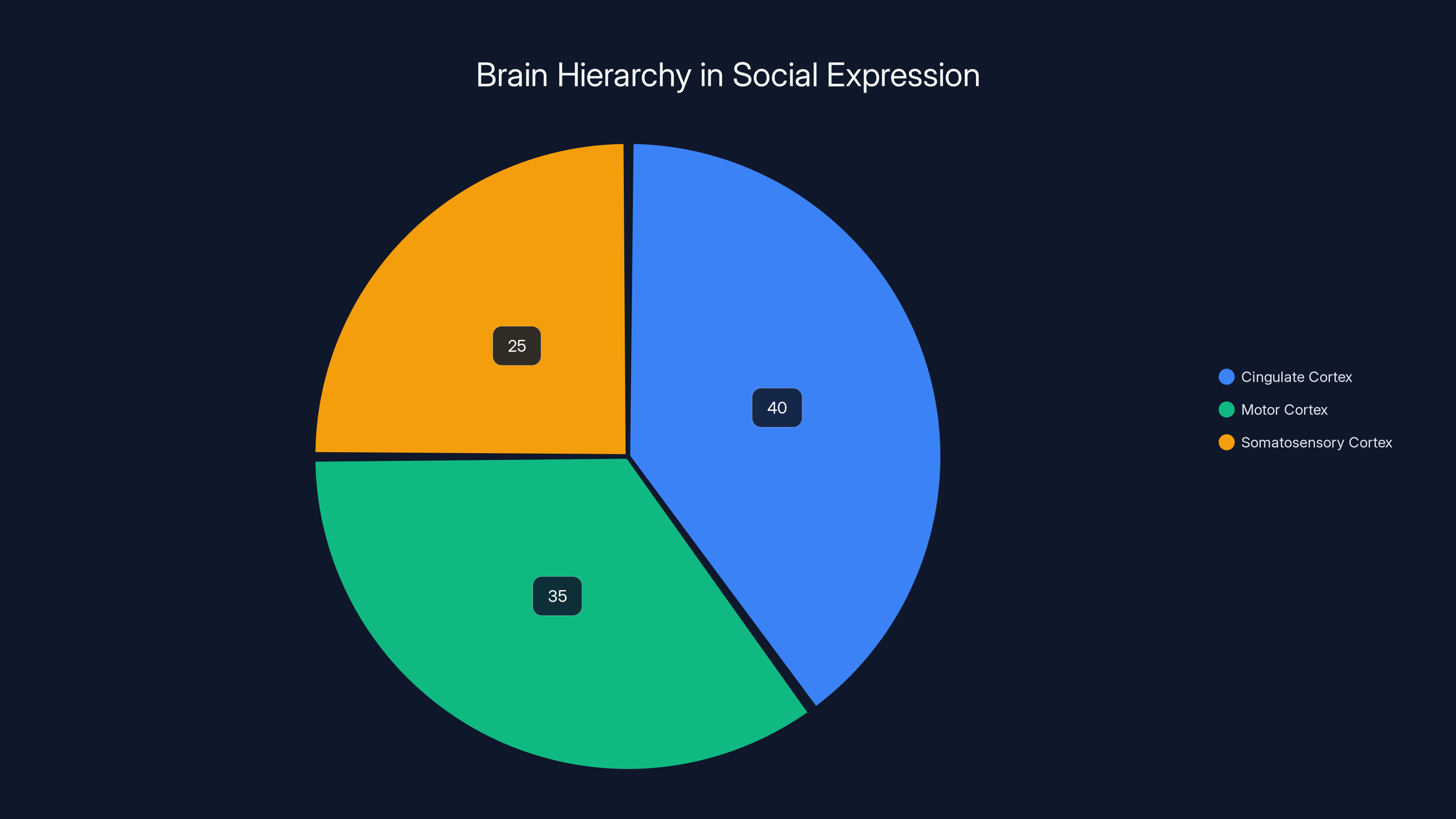

The cingulate cortex, motor, and somatosensory regions play significant roles in controlling facial expressions, with the cingulate cortex maintaining static codes and the others using dynamic codes. Estimated data.

Why Understanding Facial Expressions Matters More Than You Think

Facial expressions are weird. They're partially automatic, partially conscious. You make a smile when you're happy, but you can also fake one. You grimace when you're hurt, but you can suppress it if you're trying to look tough. Some expressions feel almost involuntary—the shock on your face when something surprises you happens before you even think about it.

Neuroscientists have known for decades that this complexity exists, but they couldn't explain why at the neural level. The dominant theory, built on case studies of stroke patients with specific brain lesions, suggested a clean division of labor. Emotional expressions—the ones you make involuntarily—came from one set of brain regions. Voluntary expressions, like the ones you control during speech, came from other regions.

This theory made intuitive sense. Emotions feel automatic. Controlled movements feel... controlled. So the brain must process them separately, right? Not quite. The problem was that case studies of brain lesions give you coarse information. If a stroke damages a region, and the patient loses the ability to make one type of expression, you can conclude that region is involved. But you can't conclude it's exclusively responsible, and you certainly can't understand how dozens of neurons coordinate across that region to create the expression.

That's where the new study breaks ground. By recording from individual neurons, Geena Ianni and her team could see exactly what's happening in real time, at the cellular level, as a macaque decides to smack its lips, threaten a rival, or just chew some food.

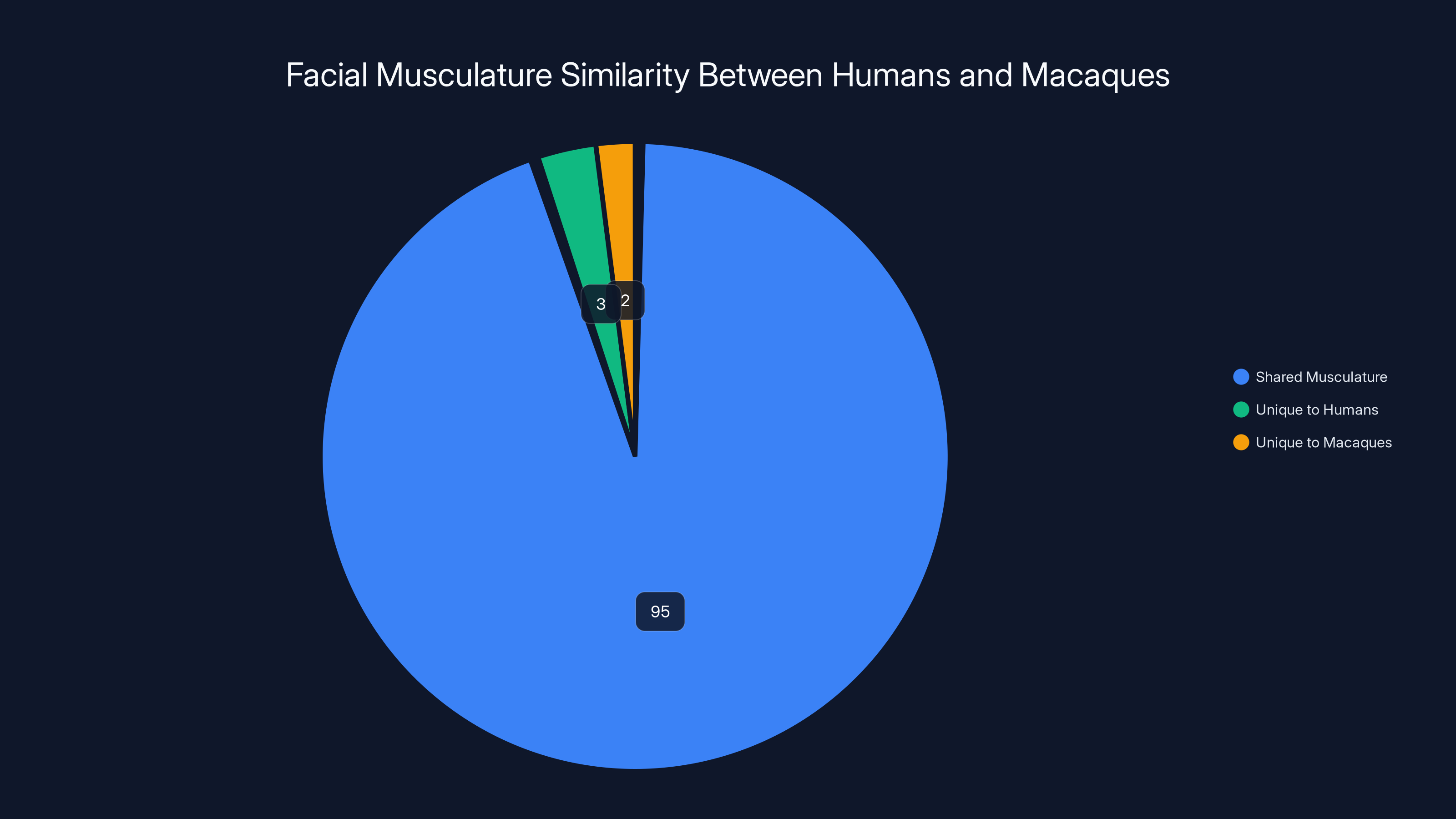

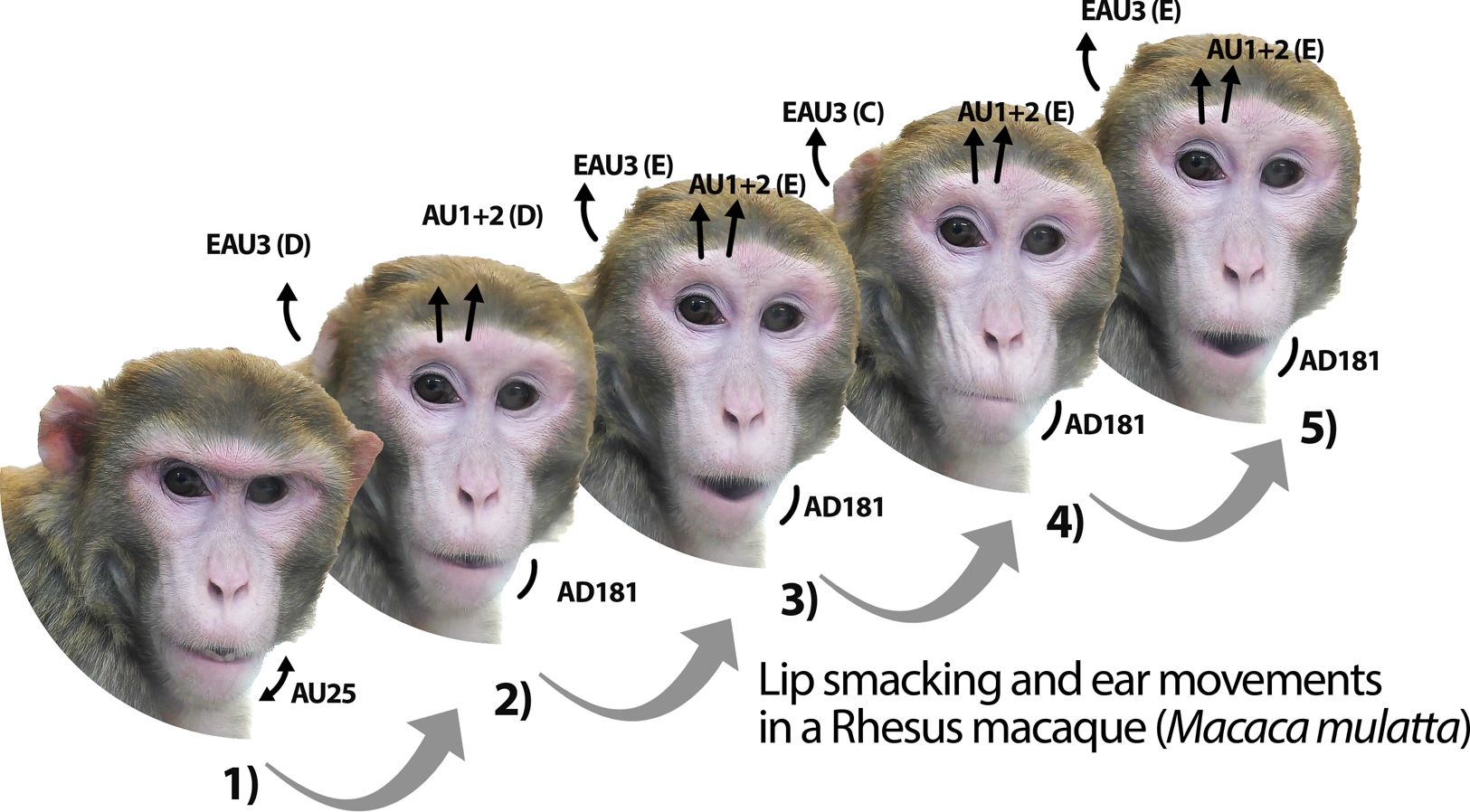

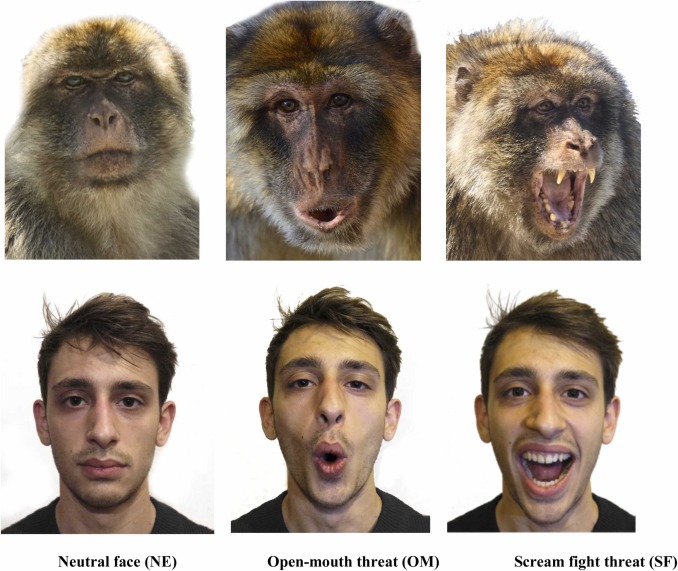

Macaques are perfect research subjects for this work. They're social primates with complex facial expressions that serve specific social purposes—just like humans. They have the same basic facial muscles, arranged in similar patterns. And critically, they'll voluntarily perform facial gestures in response to social stimuli, so researchers can watch the behavior and the brain activity at the same time.

Macaques share approximately 95% of their facial musculature with humans, making them ideal for expression studies. Estimated data.

The Experimental Design: How Researchers Watched Macaque Brains Make Faces

The study began with a seemingly straightforward question: What happens in the brain when a macaque makes a face?

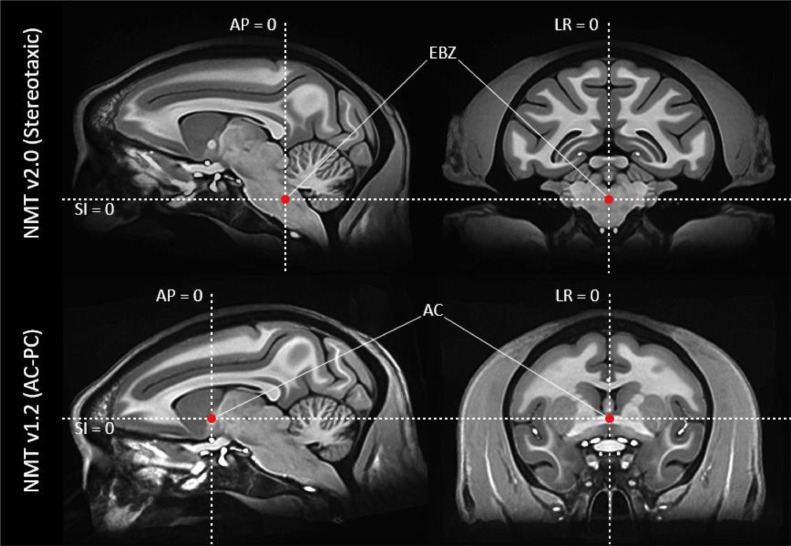

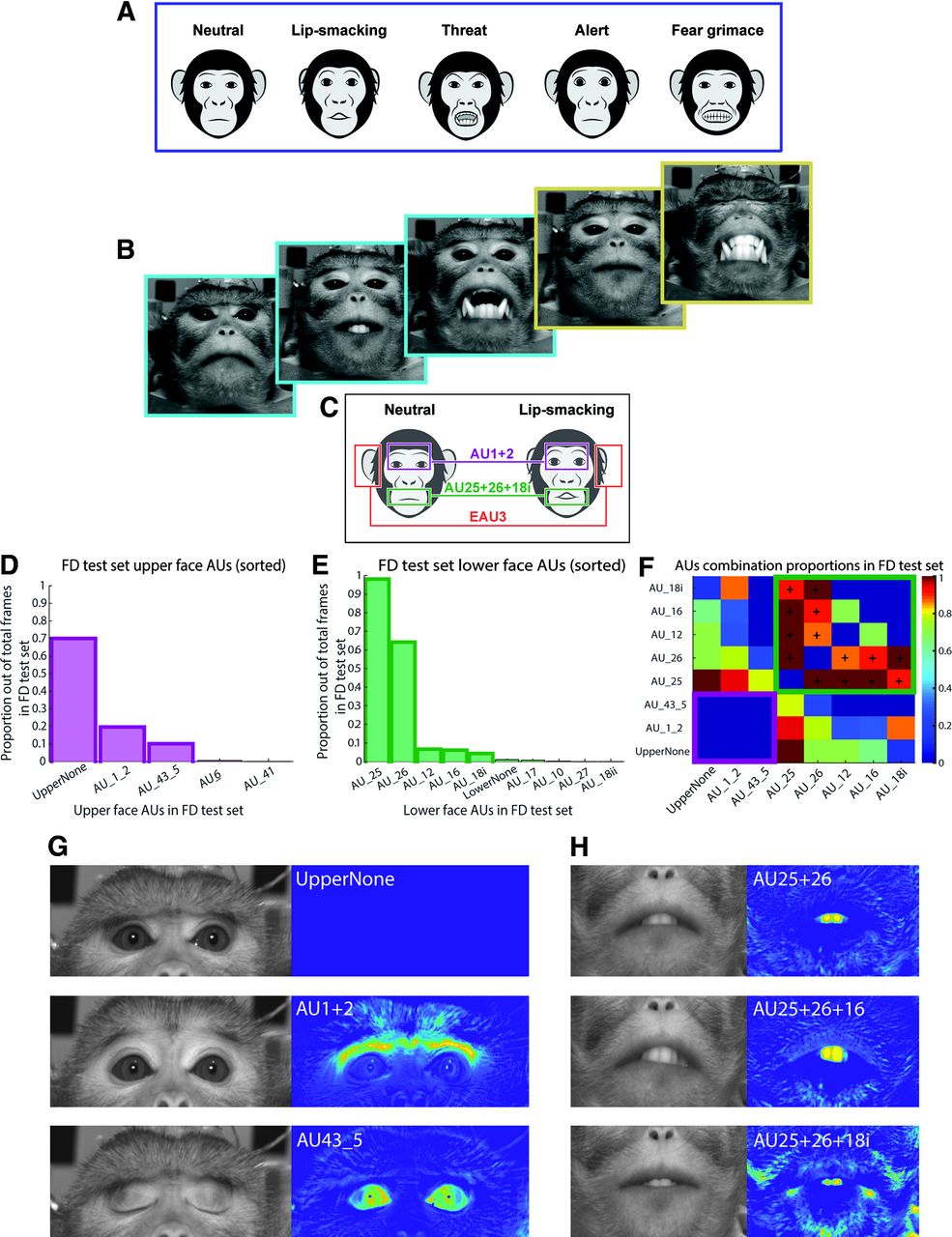

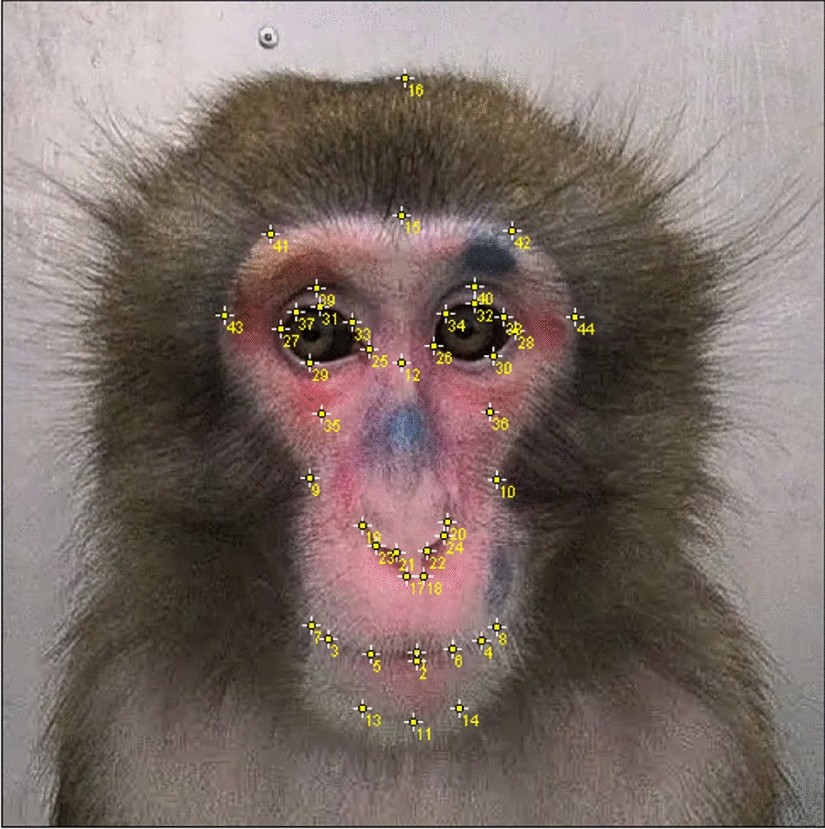

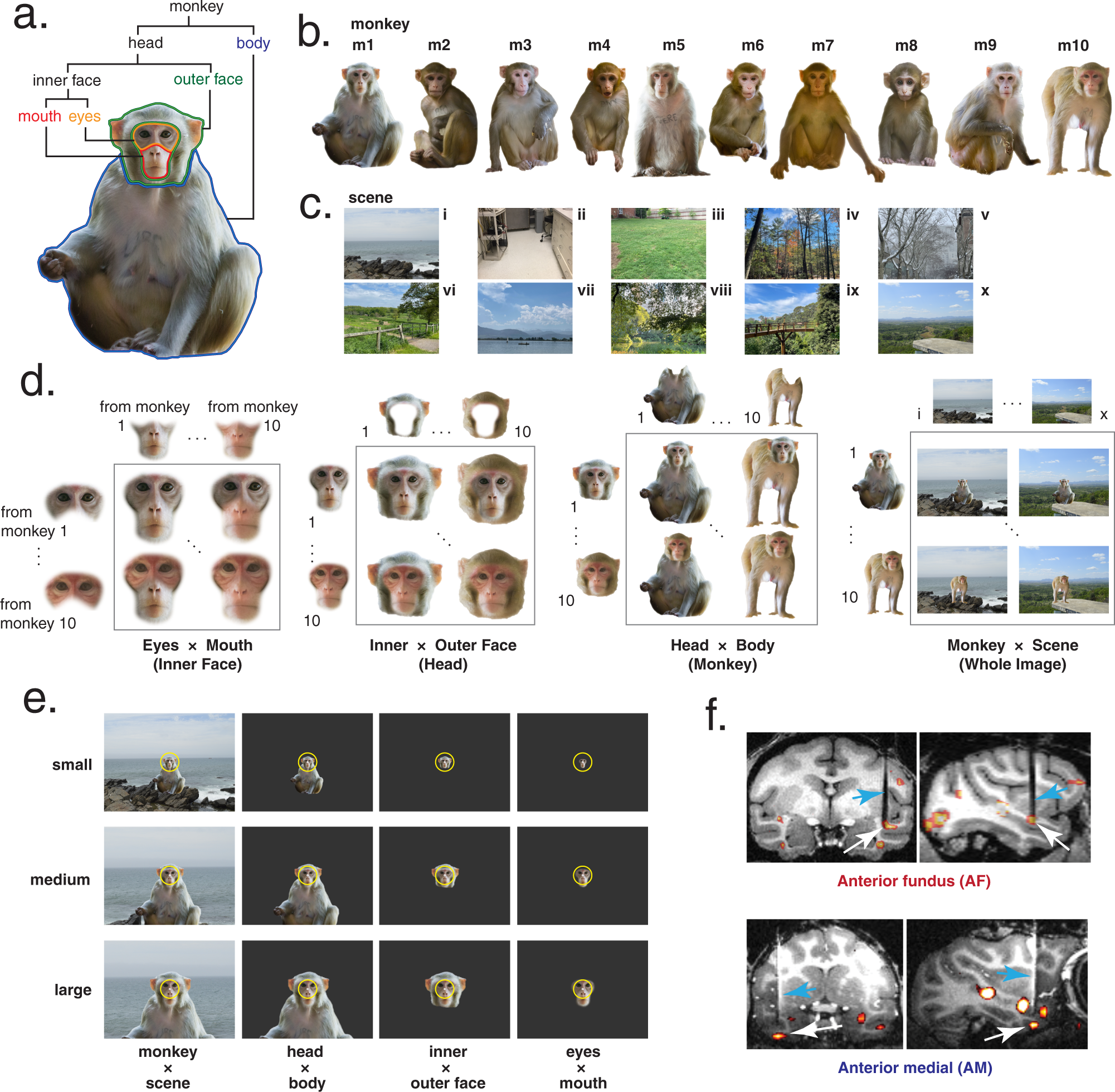

To answer it, the team needed to observe natural facial expressions in a controlled way. This meant putting macaques in an f MRI scanner—the same kind of machine doctors use to scan human brains—while recording their expressions with a high-resolution camera. The team then exposed the macaques to various social stimuli: videos of other macaques making faces, interactive avatars, and live macaques in adjacent enclosures. Some of these stimuli were deliberately provocative, designed to trigger threat responses. Others were more neutral.

The macaques reacted naturally. They performed facial gestures that are part of their normal social repertoire. And the f MRI scanner captured which parts of their brains lit up during each expression.

From this initial phase, the team identified three specific facial gestures to focus on:

- Lipsmack: A rapid, rhythmic movement of the lips that macaques use to signal receptivity, submission, or friendly intent. It's a "I'm not a threat" signal.

- Threat face: The expression macaques make when they want to challenge or scare off an adversary. Teeth bared, direct stare, ears back.

- Chewing: Non-social, purely mechanical jaw movements. This served as a control—a movement that's volitional but not communicative.

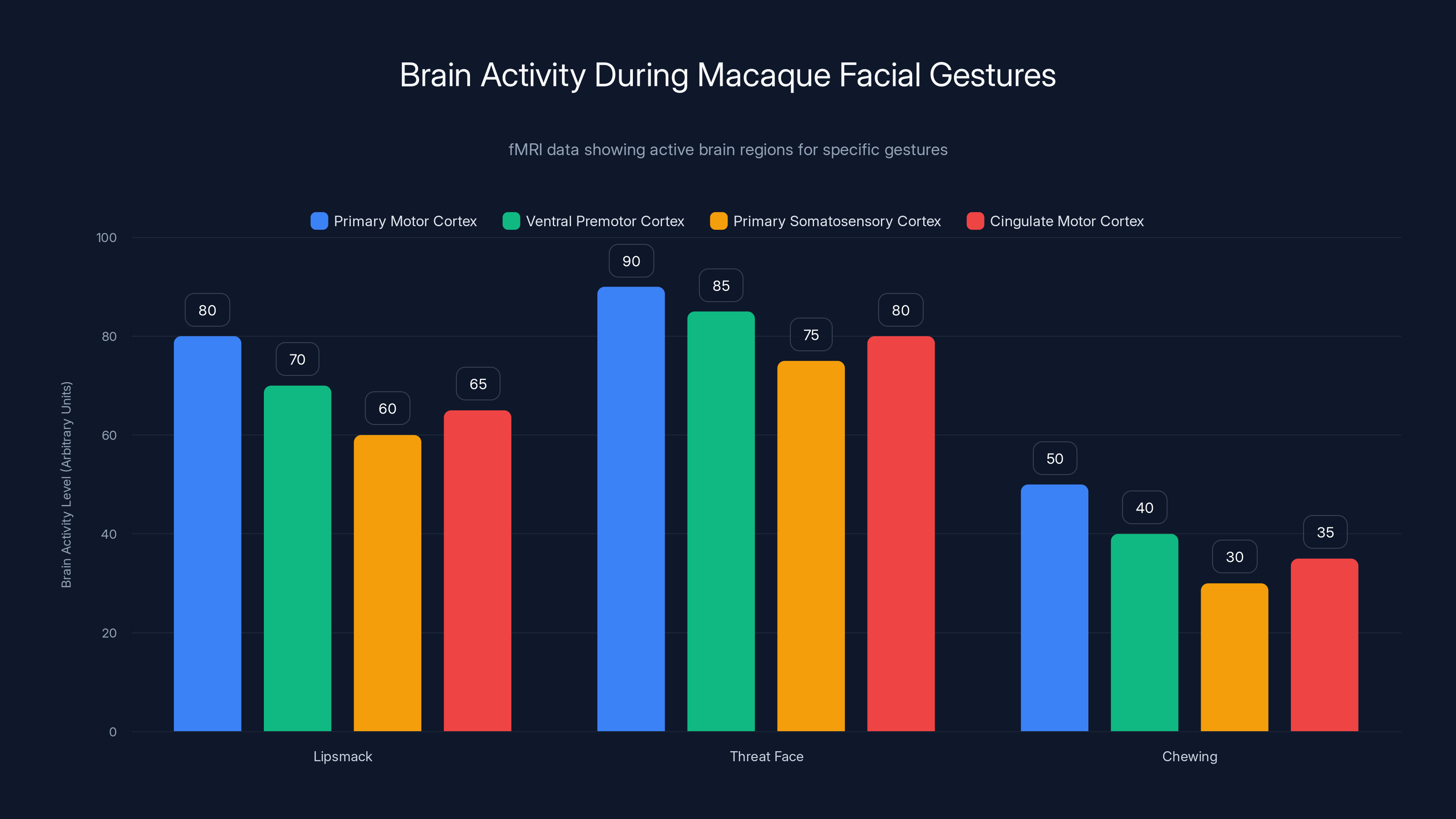

The f MRI data revealed which brain regions were active during each gesture. Four areas showed consistent activity:

- Primary motor cortex

- Ventral premotor cortex

- Primary somatosensory cortex

- Cingulate motor cortex

Here's where the study pivots. Standard f MRI shows which brain regions are involved, but with limited precision. The team knew roughly which areas were active, but they needed to know exactly what individual neurons were doing. So they took the next step: implanting micro-electrode arrays directly into these brain regions.

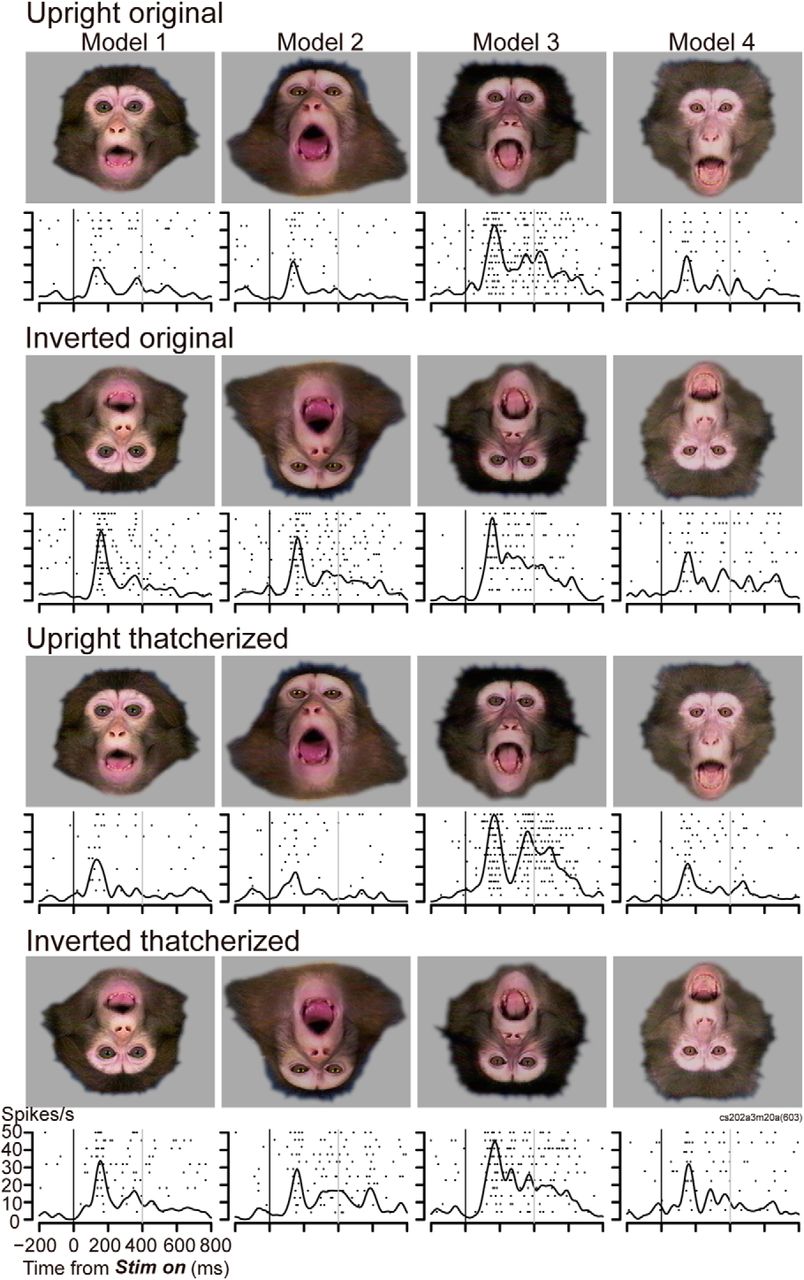

This was the experimental breakthrough. For the first time, researchers could watch dozens of neurons fire in real time as macaques produced facial expressions. The arrays went into the four identified brain areas, and the team repeated the same stimulus protocol. They exposed the macaques to videos, avatars, and live rivals, watching both their expressions and the neural activity.

The Shocking Result: Every Brain Region Does Everything

This is where the study upended conventional wisdom.

The team expected to see specialization. They expected the cingulate cortex—the region associated with emotion—to fire strongly during lipsmacks and threat faces, but not during chewing. They expected the motor cortex to show the opposite pattern: active during chewing but quieter during social gestures. Clean division of labor, just like the textbooks said.

Instead, they found something unexpected. All four brain regions showed strong activity during all three types of gestures. The motor cortex fired during social expressions. The cingulate cortex fired during chewing. There was no regional specialization.

This was the first major surprise, but not the biggest one.

If all regions are involved in all gestures, how does the brain distinguish between a social expression and a food-motivated movement? The answer wasn't in where the brain processes the information. It was in how the information is encoded.

The fMRI data shows that the 'Threat Face' gesture activates the most brain regions, particularly the primary motor cortex. 'Chewing' involves less activity across all areas. Estimated data based on typical fMRI findings.

The Neural Code: Static Patterns vs. Dynamic Patterns

Here's the key insight from the study: different brain regions use fundamentally different ways of representing information.

When the team analyzed the firing patterns of neurons in the cingulate cortex, they found something striking. The neurons maintained a consistent pattern of activity throughout the gesture. If neuron A fired every 50 milliseconds, neuron B fired every 80 milliseconds, and neuron C stayed relatively quiet, those patterns stayed stable. This held true across multiple repetitions of the same gesture and across time.

The researchers call this a static neural code. It's like a fingerprint. The pattern is stable enough that a simple computer algorithm could recognize it at any point during the gesture or during any trial.

The motor cortex and somatosensory cortex told a completely different story. In these regions, the firing patterns of neurons changed constantly. The relationships between neurons—which ones fired together, which ones fired in sequence—were constantly shifting. This rapid, dynamic change in firing relationships represents what the team calls a dynamic neural code.

Here's what this means functionally:

The static code in the cingulate cortex appears to encode the social context and purpose of the expression. It asks: "Should I make a submission signal or a threat? What social goal am I trying to achieve?" This information is relatively stable because the social context doesn't change rapidly. Once you decide you want to signal submission, that decision stays consistent for the duration of the gesture.

The dynamic codes in the motor and somatosensory cortex encode the specific motor commands. They ask: "How do I physically execute this expression? Move this muscle 2 millimeters left. Now move this one 1 millimeter up." These patterns change constantly because facial expressions are inherently dynamic. Even when a macaque's threat face looks static from a distance, muscles are constantly twitching, adjusting, fine-tuning the position of lips, ears, and eyelids.

The Hierarchy: How Context and Execution Are Separated

The distinction between static and dynamic codes points to a hierarchical organization in the brain.

At the top of the hierarchy sits the cingulate cortex, using static neural codes to represent the broad social intent. This region integrates multiple sources of information: what other macaques are doing, internal emotional states, recent social history. All of this gets condensed into a relatively stable neural pattern that represents the social decision.

Below this sits the motor and somatosensory cortex, using dynamic neural codes to execute that decision. These areas receive the stable signal from above—"make a threat face"—and translate it into the precise, constantly-shifting muscle commands needed to physically execute the threat.

This is a hierarchical division of labor, but not the one scientists expected. It's not divided by gesture type (social vs. non-social). It's divided by level of abstraction. High-level abstract goals (social intent) in one region. Low-level concrete commands (muscle movements) in other regions.

This architecture makes biological sense. It allows flexibility and reuse. The same motor commands could be used to create different social expressions depending on the abstract goal selected. A threat face and a submission face both involve moving muscles in the mouth and eyes, just in different combinations and sequences. By separating the decision (cingulate) from the execution (motor), the brain allows the same neural machinery to generate diverse expressions depending on context.

Estimated data shows the cingulate cortex plays a major role in processing social intent, while motor and somatosensory cortices handle execution. This separation allows for flexible expression generation.

The Temporal Hierarchy: Timing Encodes Meaning

Beyond the distinction between static and dynamic codes, the researchers discovered another organizational principle: timing.

In the cingulate cortex, the static firing patterns emerged early—as soon as the macaque started planning the gesture. The pattern was established and maintained throughout the movement. In technical terms, the neural code was persistent across time.

In the motor and somatosensory regions, the neural dynamics were constantly evolving. The researchers could identify different phases of the gesture based on which neurons were active at each moment. Early in the gesture, one set of firing relationships characterized the neural activity. Mid-way through, a different set. Late in the gesture, another pattern entirely.

This suggests a temporal hierarchy: the static code in the cingulate sets the goal, and the dynamic codes in the motor regions orchestrate a temporal sequence of muscle commands to achieve that goal. The timing of neural activity in the motor regions directly corresponds to the timing of muscle movements.

The team could verify this by looking at lag times. When they analyzed the delay between neural activity in the cingulate and neural activity in the motor regions, they found clear evidence of feed-forward control. The cingulate fires first, establishing the social goal. Fractions of a second later, the motor regions light up to execute it.

Decoding Facial Expressions: What This Means for Neural Prosthetics

Understanding how the brain generates facial expressions has immediate practical implications.

Neuroscientists are already building neural prosthetics that can decode intended speech from brain signals in paralyzed patients. The technology works by recording from motor cortex, identifying the patterns of neural activity that correspond to specific phonemes or words, and translating those patterns into text or synthesized speech.

Facial expressions could be decoded the same way. A paralyzed patient's cingulate cortex would still generate those stable neural codes representing their social intent. A neural prosthetic could record those codes and use them to control a robotic face, or to modulate the patient's synthesized speech with emotional content.

The benefit is profound. Speech conveys literal meaning. A sentence like "I'm happy" has clear semantic content. But the expression on your face while you say it conveys something equally important: whether you're genuinely happy, sarcastically happy, or forcing happiness to be polite. A neural prosthetic that decodes only speech loses this emotional dimension. One that decodes both speech and facial expressions can preserve the full richness of human communication.

The technology is still years away from clinical application. Implanting micro-electrode arrays in human brains is a major surgery with significant risks. Researchers need to identify which specific neurons to record from, how to keep the electrodes in place long-term, and how to build decoders that work reliably across months or years as the brain changes. But the foundational neuroscience is now in place.

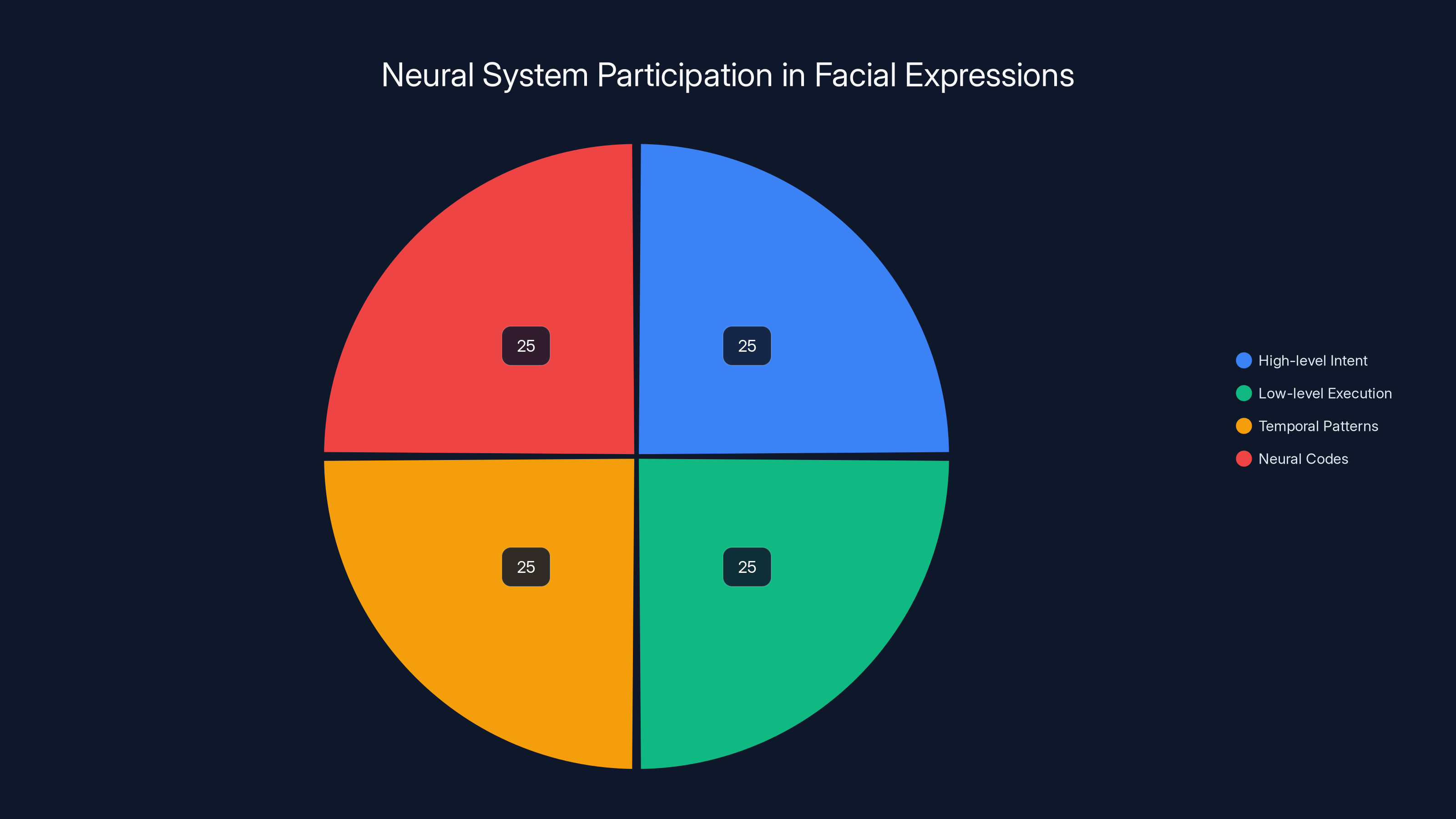

The study suggests that all neural regions participate equally in facial expressions, each with distinct roles. Estimated data.

Implications for Understanding Other Forms of Nonverbal Communication

The static-versus-dynamic code distinction has implications beyond facial expressions.

Hand gestures, body postures, and vocal prosody—the emotional tone of speech—might follow similar organizational principles. A high-level region could represent the abstract communicative intent ("I want to convey surprise"), while motor regions translate that into specific gestures or vocal patterns.

If this is true, neural prosthetics could eventually decode and reproduce multiple channels of communication simultaneously. A paralyzed patient's neural signals could drive not just synthesized speech, but animated facial expressions and gestures that match the emotional content of what they're trying to convey.

This would make the prosthetic feel more natural, both to the user and to people interacting with them. Currently, when people use text-to-speech synthesizers or typing-based communication methods, they lose the nonverbal dimension entirely. They become flat. Adding facial expressions and gestures back would restore much of what's lost.

The Evolution of Facial Communication in Primates

From an evolutionary perspective, this research raises interesting questions about how facial communication evolved.

Macaques, like humans, use facial expressions to regulate social relationships. The lipsmack signals "I'm not a threat." The threat face signals "back off." These expressions appear across multiple primate species, suggesting they evolved deep in our common ancestry.

The hierarchical organization the researchers discovered—with abstract social intent separated from specific motor execution—might represent an evolutionary adaptation. As primate groups grew larger and social hierarchies became more complex, the ability to flexibly produce different expressions in different contexts became more valuable. Separating the social decision from the motor execution allows for this flexibility.

Early in primate evolution, perhaps facial expressions were more stereotyped, more reflexive. The motor commands and the social intent were tightly coupled. Over time, natural selection favored individuals who could dissociate these two levels, allowing for more nuanced, context-dependent expressions. This added cognitive layer would have provided a significant social advantage.

The fact that humans can suppress or fake expressions, while macaques show more reflexive emotional expressions, might reflect continued evolution of these control mechanisms in the human lineage.

The cingulate cortex predominantly uses static patterns, maintaining consistent neural firing, while the motor and somatosensory cortices exhibit high variability, indicating dynamic patterns. Estimated data.

Methodological Significance: Why Micro-Electrode Arrays Matter

Beyond the scientific findings, this study is significant for the methods it employs.

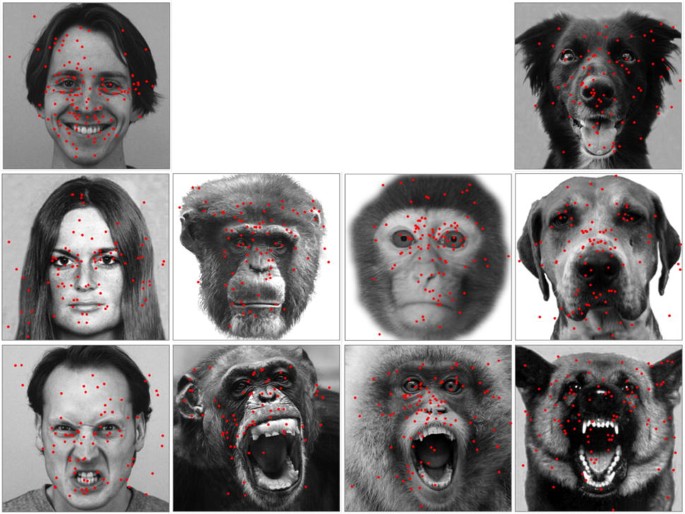

Micro-electrode arrays have been used in neuroscience research for decades, but mostly for studying single neurons or small neural ensembles. This is the first study to use them to record simultaneously from dozens of neurons across multiple brain regions while an animal produces natural, social behaviors.

Previous studies of facial expression involved either f MRI (good spatial resolution, poor temporal resolution) or single-neuron recording (excellent temporal resolution, poor spatial resolution). This study bridges both worlds, capturing what dozens of neurons are doing simultaneously with millisecond precision.

This methodological advance opens doors for future research. The same approach could be used to study other complex behaviors: decision-making, social interaction, learning. Any behavior that involves coordination across multiple brain regions could potentially benefit from this technique.

The downside is invasiveness. Micro-electrode implants require surgery and carry risks of infection or tissue damage. They also eventually degrade—the electrodes can shift, electrical impedance can change. For animals like macaques used in research, this is acceptable. For human patients, it's a significant hurdle that researchers are actively working to overcome.

Comparing to Human Neuroscience: What We Know from Brain Imaging Studies

How does this macaque research compare to what we already know about facial expressions in humans?

Human neuroimaging studies have long suggested that different brain regions are involved in emotional versus volitional facial expressions. Studies using PET scans and f MRI found that emotional expressions activate the amygdala and insula, while volitional expressions primarily activate motor cortex.

But here's the crucial point: neuroimaging studies can show which regions are active, but they can't show how individual neurons are coordinating. The macaque study, by recording from individual neurons, reveals the mechanism underlying these imaging findings. It shows that all regions participate in all expressions, but they participate using different codes.

This explains why neuroimaging studies were partially misleading. When you look at average activation across a region in an f MRI scan, you're seeing the cumulative effect of thousands of neurons firing. If some neurons use a static code and others use a dynamic code, the overall activation pattern might look different between regions even if they're all participating in all expressions.

The macaque work provides a proof-of-concept for something neuroscientists have long suspected: that the same neural tissue can be organized in different ways to perform different functions. Adding a layer of dynamic processing on top of a static code doesn't require different neurons. It just requires different temporal patterns of activity in the same neurons.

Limitations and Open Questions

The study is groundbreaking, but it's also the beginning of a much longer research process.

One significant limitation: the research was conducted in anesthetized or restrained animals. While the macaques were allowed to make facial expressions naturally, they weren't fully free to behave as they would in a natural social environment. This raises questions about whether the neural patterns observed in the lab exactly match those in the wild.

Another limitation: the sample size was small. Only a few macaques were studied, and only a handful of specific gestures were analyzed in detail. Whether the static-versus-dynamic code distinction applies to all facial expressions or just the three studied remains an open question.

Third, the study doesn't explain why the brain uses this hierarchical coding strategy. Is it more efficient? Does it allow for greater flexibility? Does it enable learning? These are biological and evolutionary questions that the current study can't answer.

Fourth, there's the translation question. Macaques and humans are related, but we're not identical. Human facial anatomy is somewhat different. Human social expressions have evolved over millions of years since we diverged from our common ancestors with macaques. The neural organization might differ in important ways. Clinical translation will require validation in human patients.

Future Directions: Where This Research Goes Next

The immediate next step is validation and extension.

Researchers will likely repeat this study with more macaques, more facial gestures, and more detailed analysis of the neural dynamics. They'll want to understand how the static codes evolve over learning—do young macaques have different cingulate patterns than experienced adults? Do macaques that are good at social manipulation show different neural codes than socially awkward individuals?

They'll also probably extend the work to other primates. Chimpanzees and bonobos have more complex social structures than macaques. Do they show more elaborate hierarchical organization in their neural codes? How far back in primate evolution does this system go?

On the applied side, neuroscientists will begin translating these findings into clinical applications. This means identifying whether humans show the same static-versus-dynamic code organization, developing safer recording methods, and building the machine learning systems needed to decode facial intent from neural signals.

There's also fundamental neurobiological work to be done. The macaque study identifies that neural codes are different in different regions, but it doesn't explain why. Is this because different regions have different types of neurons? Different connectivity patterns? Understanding the cellular and circuit mechanisms underlying these codes is the next frontier.

Broader Implications for Brain-Computer Interfaces

This research sits at the intersection of neuroscience, biomedical engineering, and computer science.

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have advanced rapidly in the past decade. They can now decode intended hand movements, allowing paralyzed patients to control robotic arms. They can decode intended speech, allowing locked-in patients to communicate using thought alone. But most BCIs focus on one channel of communication at a time.

The macaque study suggests a path toward multi-channel BCIs. If we understand the neural codes for facial expressions, we could potentially decode them alongside speech. A paralyzed patient using a BCI could not just speak words, but simultaneously convey emotional intent through a synthetic face.

This requires understanding not just facial expressions, but how they're coordinated with other motor outputs. When you speak while smiling, your facial expression is coordinated with your vocal output. The static code in the cingulate would presumably represent this higher-level intent ("convey friendly confidence"), while dynamic codes in different motor regions execute the specific commands for speech and facial movement simultaneously.

Building BCIs that can handle this complexity is non-trivial, but the macaque study provides the foundational neuroscience.

The Ethics of Neuroscience Research Using Animals

Before closing, it's worth acknowledging the ethical dimensions of this research.

The study involved implanting electrodes in macaque brains. This is invasive and carries risks. It raises legitimate questions about whether the knowledge gained justifies the procedures performed.

Researchers take this seriously. Institutional animal care committees review and approve every proposed study. Pain management is provided. Living conditions are as enriched as possible. And the research is chosen specifically for its potential human benefit.

In this case, the potential benefit is significant: helping paralyzed patients communicate more naturally and expressively. The knowledge gained about how brains generate expressions could improve the lives of thousands of people. From an ethical perspective, this potential benefit is weighed against the costs to the animals involved.

Reasonable people can disagree about where the ethical line should be drawn. But it's important to acknowledge that neuroscientists are grappling with these questions seriously and implementing safeguards.

The Arc of Neural Communication Research

Zoom out and this macaque study fits into a broader scientific narrative.

For the past 50 years, neuroscience has progressively mapped how brains control behavior at finer and finer levels of detail. We started with brain regions. Then neurons. Then synapses. Then molecular mechanisms. At each step, we've discovered that behavior emerges from hierarchical organization, where high-level goals are gradually broken down into specific, low-level commands.

The macaque facial expression study continues this arc. It shows that something as apparently unified as a facial expression is actually the product of multiple brain regions using different codes, organized hierarchically. The social intent lives in one representation. The motor execution lives in another. Understanding this distinction opens new doors for translating neuroscience into medicine.

It's a reminder that the brain is both unified and modular. A single behavior emerges from coordinated activity across multiple regions, each operating according to different principles. The challenge for future neuroscience is understanding how these principles are implemented at the cellular level and how they can be leveraged to restore function when things go wrong.

FAQ

What does the macaque facial expression study reveal about how brains control communication?

The study shows that facial expressions are controlled through a hierarchical system where the cingulate cortex maintains a stable, static neural code representing the social intent or purpose of the expression. Meanwhile, motor and somatosensory regions use rapidly changing dynamic neural codes to execute the specific muscle movements needed to physically produce the expression. This separation allows the brain to flexibly generate diverse expressions depending on social context.

How did researchers record neural activity from macaque brains while they made facial expressions?

Researchers first used f MRI scanning to identify which brain regions were active during facial expressions. They then implanted micro-electrode arrays—tiny clusters of electrodes about the thickness of a human hair—directly into four key brain regions. These arrays allowed them to record electrical signals from dozens of individual neurons simultaneously while the macaques produced facial gestures in response to social stimuli like videos, avatars, or other macaques.

Why is understanding facial expression control important for medicine and neural prosthetics?

Currently, neural prosthetics for paralyzed patients can decode intended speech from brain signals, but they cannot capture the emotional and nonverbal dimension of communication. Understanding how the brain generates facial expressions could allow future prosthetics to simultaneously decode both speech and facial intent from neural signals. This would allow paralyzed patients to communicate not just words, but the emotions and social nuance that make human communication rich and natural.

What is the difference between static and dynamic neural codes discovered in the study?

Static neural codes, found in the cingulate cortex, maintain consistent firing patterns across time and multiple repetitions of the same gesture. They represent stable information about social intent. Dynamic neural codes, found in motor and somatosensory regions, show constantly changing patterns of neural firing that correspond to the moment-to-moment muscle commands needed to execute the expression. This difference reflects a division of labor: abstract decision-making versus concrete execution.

How do these findings challenge the previous understanding of facial expression control?

For decades, neuroscientists believed that facial expressions were controlled by a clean regional specialization: emotional expressions came from one set of brain regions while volitional expressions came from others. This study showed that all four recorded brain regions participated in all types of expressions. Instead of regional specialization, the brain uses different neural coding strategies in different regions, creating a hierarchical organization that wasn't previously recognized.

Could this research eventually allow paralyzed patients to smile through neural prosthetics?

Yes, that's a potential long-term application. If researchers can identify the neural codes in a patient's brain that represent the intention to smile, and build a decoder that translates those codes into commands for a robotic face or animated avatar, a paralyzed patient could theoretically control facial expressions through thought alone. However, this would require translating the findings from macaques to humans and solving significant technical challenges around electrode implantation and long-term biocompatibility.

What makes macaques ideal subjects for studying facial expression control?

Macaques are social primates that share approximately 95% of their facial musculature with humans. They naturally produce complex, socially meaningful facial expressions in response to social stimuli. Their facial expressions serve similar communicative functions to human expressions—signaling submission, threat, affiliation—making findings directly translatable to human neuroscience. They're also large enough to accommodate surgical implantation of recording electrodes.

Are there limitations to applying these macaque findings to human neural control of facial expressions?

Yes, several limitations exist. First, the macaque study analyzed only a few specific facial gestures, not the full repertoire of expressions. Second, human and macaque facial anatomy differ somewhat, as do human and macaque social structures. Third, humans have greater control over facial expressions than macaques, suggesting human neural organization might be more elaborate. Clinical translation will require validation of these findings in human subjects before they can be reliably applied to medical treatments.

How might understanding facial expression control improve brain-computer interfaces beyond communication?

Multi-channel brain-computer interfaces could decode facial expressions simultaneously with speech, allowing better coordination of nonverbal and verbal communication. Understanding the hierarchical organization of facial control could inform how to design BCIs for other complex behaviors involving coordination across multiple motor systems. The insights about static versus dynamic codes might apply to other motor behaviors beyond facial expressions.

What is the next step in translating this macaque research toward clinical applications?

Researchers will likely conduct validation studies in more macaques with more detailed analysis, extend findings to other primate species, and begin investigating whether humans show the same neural organization. In parallel, biomedical engineers are developing safer recording methods, like wireless fully-implantable electrode arrays. Machine learning researchers are building more sophisticated decoders that can translate neural codes into control signals for robotic faces or text-to-speech systems with emotional prosody. Clinical trials in human patients are probably 5-10 years away.

Conclusion

When Geena Ianni and her colleagues published the results of their macaque facial expression study, they didn't just add another paper to the neuroscience literature. They fundamentally reframed how we think about facial communication at the neural level.

For years, neuroscientists operated under a flawed assumption: that brains control expressions through regional specialization. Different regions for different purposes. Clean divisions of labor. But the macaque data showed something far more sophisticated. All regions participate. What differs is how they participate—the neural codes they use, the temporal patterns they employ, the level of abstraction they represent.

This distinction between high-level intent and low-level execution, between static codes that represent decisions and dynamic codes that execute them, maps onto something deeper about how brains work. Every complex behavior we perform—reaching for an object, speaking a sentence, playing an instrument—probably emerges from similar hierarchical organization. We're just beginning to understand the principles governing this organization.

The clinical implications are significant. Paralyzed patients don't just want to communicate words. They want to convey emotion, intention, relationship. A neural prosthetic that could decode facial intent alongside speech would be transformative. It would restore not just communication, but the emotional richness that makes communication human.

But there's a deeper significance here. This research reminds us that behavior is never simple. What looks like a unified action—a smile, a threat—is actually the product of coordinated activity across multiple neural systems, each operating according to different principles, all orchestrated together in a symphony of neural activity.

Understanding this complexity is the frontier of neuroscience. It's how we'll eventually bridge the gap between brain and mind, between neural signals and experienced reality. The macaque study is one step on that journey, but it's a crucial one. It shows us that with the right methods and the right questions, we can begin to decode the neural basis of something as fundamentally human as the ability to express ourselves.

The next chapter in this story will be written in human patients. It will involve implanting electrodes, building machine learning models, testing whether monkeys and humans share enough neural organization that what works in one species works in the other. It will involve ethical questions about invasive procedures and the value of restored communication. It will involve engineering challenges that haven't been solved yet.

But the foundation is now in place. We know what to look for. We know that facial expressions aren't reflexive outputs—they're products of hierarchical neural control. And we know that with the right tools and approaches, we can decode them. For people living with paralysis, for people locked inside their own bodies with no way to express themselves, that foundation might someday give them back their voice—and their smile.

Key Takeaways

- Macaque brains control facial expressions using a hierarchical system where social intent and motor execution are processed by different regions using different neural codes

- All four brain regions (primary motor, ventral premotor, somatosensory, cingulate motor cortex) participate in all facial gesture types—contradicting decades of assumptions about regional specialization

- The cingulate cortex uses static neural codes representing stable social decisions, while motor regions use dynamic codes implementing constant, fine-tuned muscle adjustments

- These findings could enable future neural prosthetics to decode both speech and facial expression intent from paralyzed patients' brains, restoring emotional communication

- Micro-electrode array technology allowed unprecedented simultaneous recording from dozens of individual neurons, revealing neural coordination principles that may apply to all complex behaviors

![Macaque Facial Gestures Reveal Neural Codes Behind Nonverbal Communication [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/macaque-facial-gestures-reveal-neural-codes-behind-nonverbal/image-1-1768944969576.jpg)