Introduction: The Next Frontier in Cancer Treatment

For decades, cancer treatment has followed a familiar playbook. Surgery removes the tumor. Chemotherapy or radiation kills stray cells. Immunotherapy unleashes the immune system. But what if we could do something radically different? What if we could teach your body to recognize cancer before it ever comes back?

That's the promise of personalized mRNA cancer vaccines, and the latest data suggests they're delivering on it.

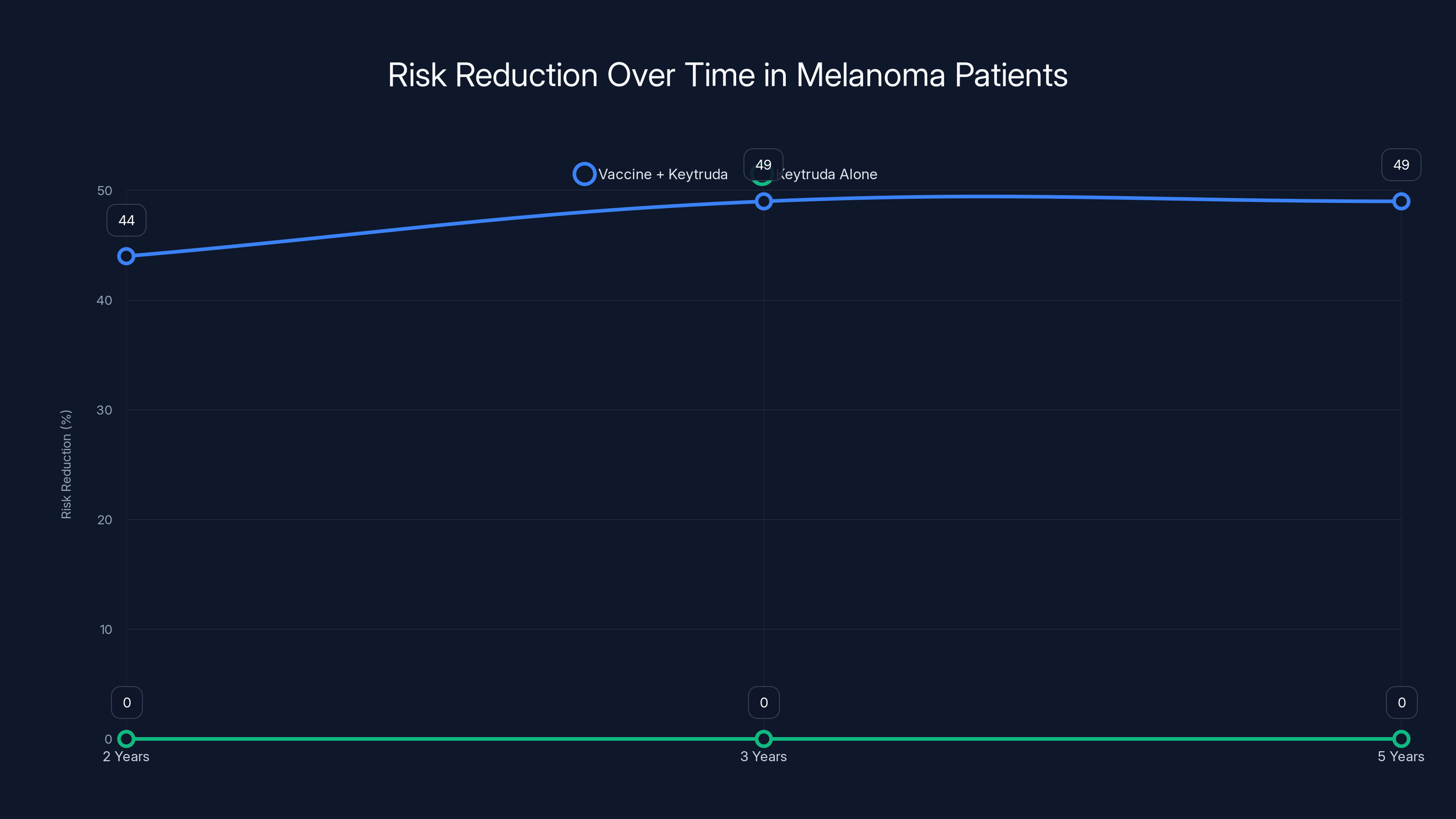

In January 2026, Moderna and Merck announced five-year follow-up results from a clinical trial of intismeran autogene, an experimental vaccine tailored to each patient's individual melanoma. The results were striking: patients who received the custom mRNA vaccine alongside standard immunotherapy experienced a 49% reduction in the risk of cancer recurrence or death compared to those who received immunotherapy alone.

To put that in perspective, a 49% risk reduction is the kind of number that changes treatment guidelines. It's the kind of result that oncologists text their colleagues about. Yet this breakthrough hasn't received nearly the attention it deserves, partly because mRNA vaccines remain politically controversial despite their proven efficacy, and partly because the science itself is genuinely complex.

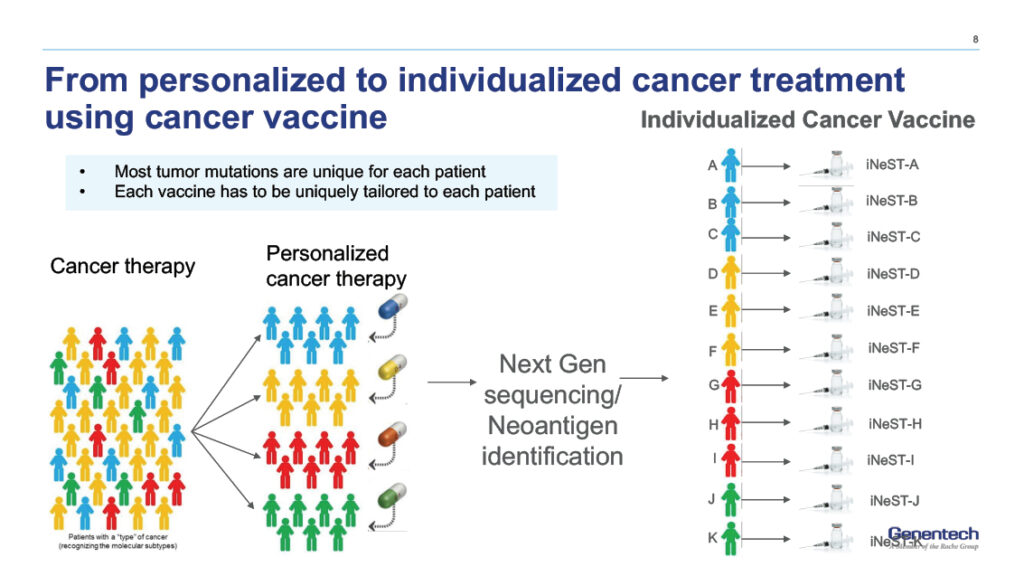

Here's what you need to know: these aren't vaccines like the COVID-19 shots that work for everyone. Each vaccine is custom-built from scratch, using genetic sequencing of your specific tumor. The process is expensive, time-consuming, and deeply personalized. But for patients with high-risk melanoma, the data suggests it could mean the difference between remission and recurrence.

This article breaks down how these vaccines work, what the five-year data actually shows, why they matter, and what comes next for cancer treatment. We'll explore the science, the clinical evidence, the manufacturing challenges, and the questions that still remain unanswered.

TL; DR

- 49% risk reduction: Personalized mRNA vaccines cut melanoma recurrence and death rates nearly in half when combined with immunotherapy

- Custom-built medicine: Each vaccine is tailored to a patient's unique tumor mutations, carrying genetic instructions for up to 34 distinct cancer markers

- Five-year durability: Protection persists for years, not months, suggesting durable immune memory against recurrence

- Mild side effects: Fatigue, injection site pain, and chills were the most common adverse events, with safety profiles matching standard immunotherapy

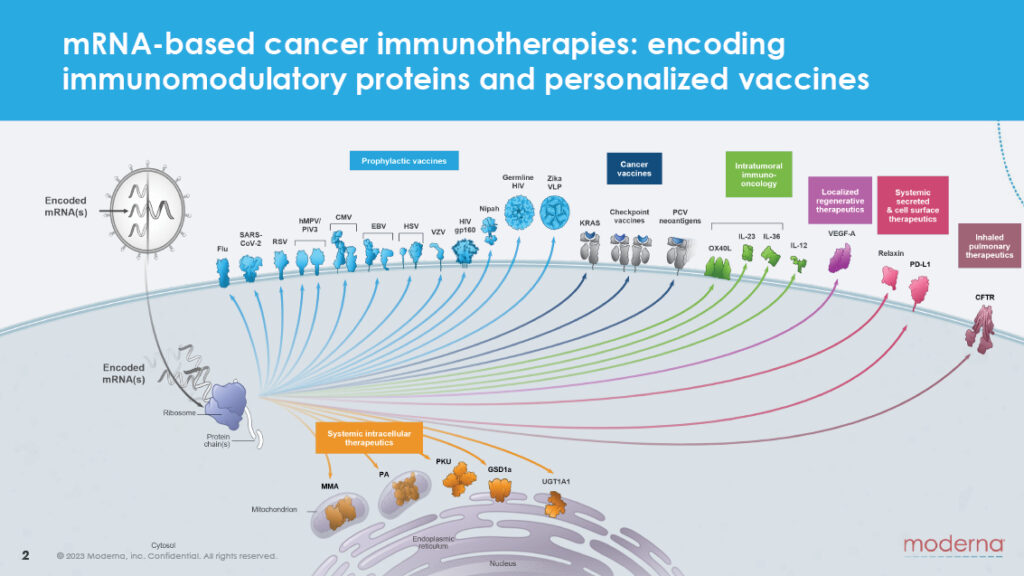

- Multiple cancer types in trials: Moderna has eight additional Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials underway for lung, bladder, kidney, and other cancers

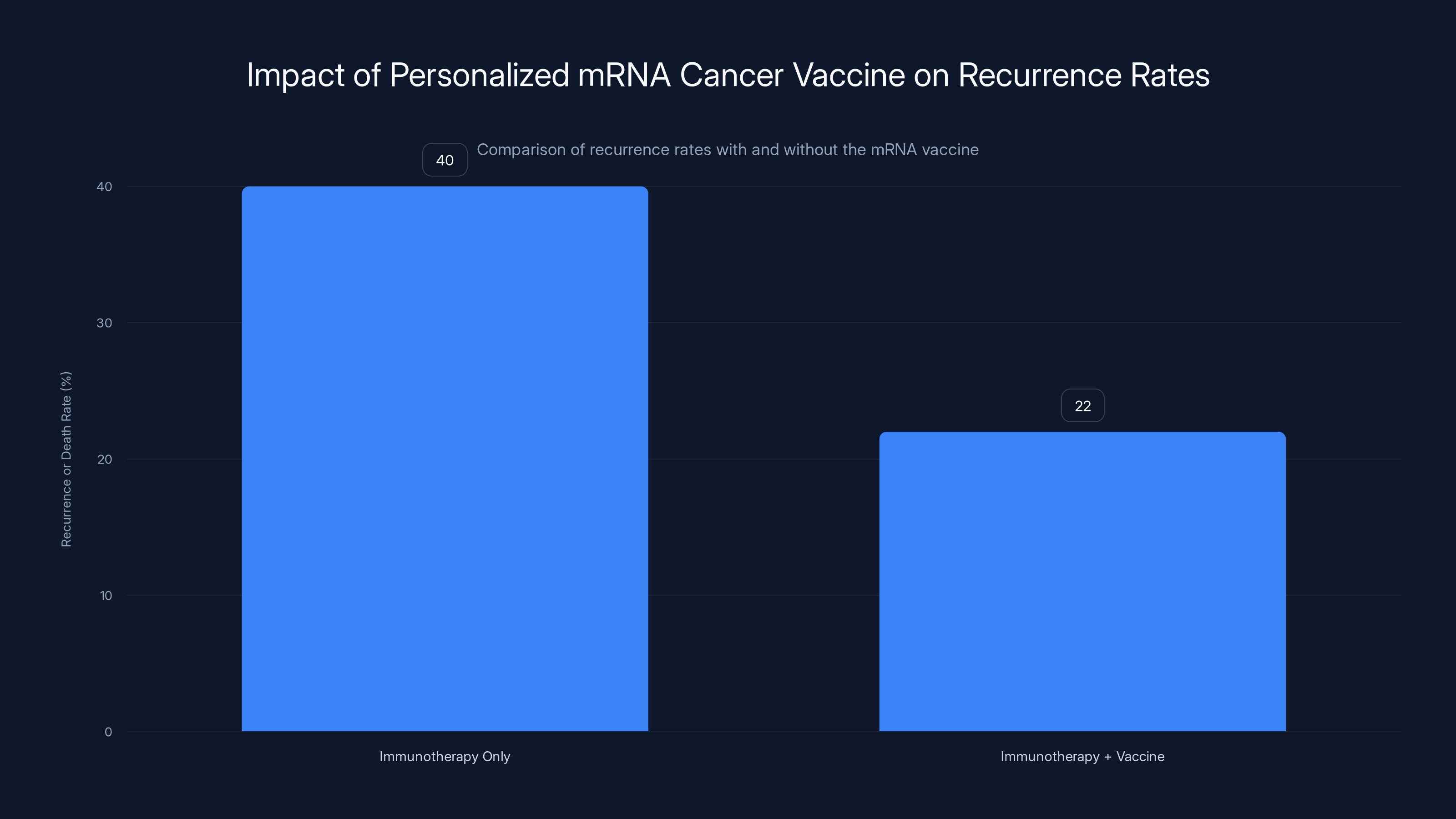

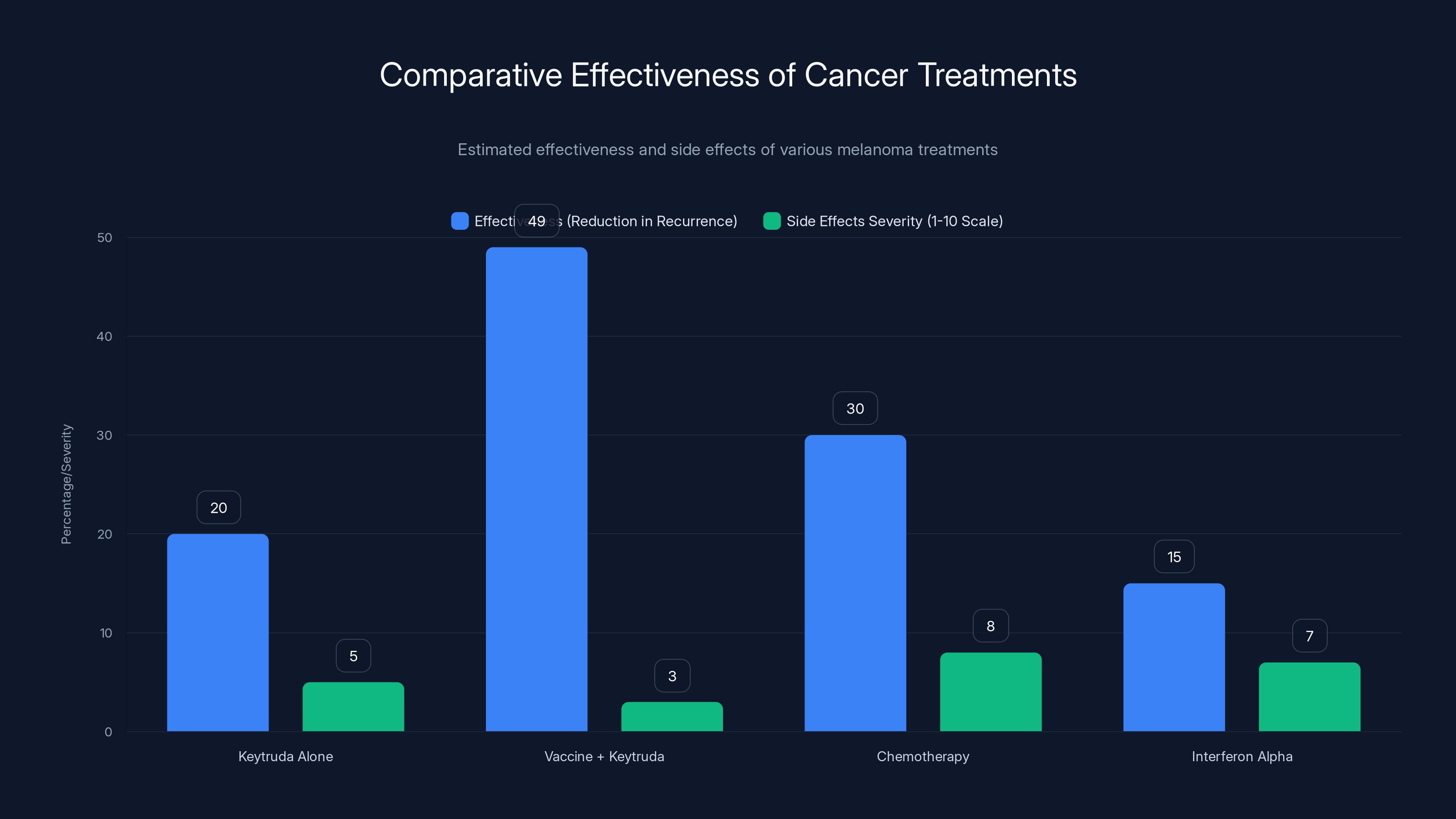

The addition of a personalized mRNA cancer vaccine to immunotherapy reduced the recurrence or death rate from 40% to 22%, showing a significant improvement in patient outcomes.

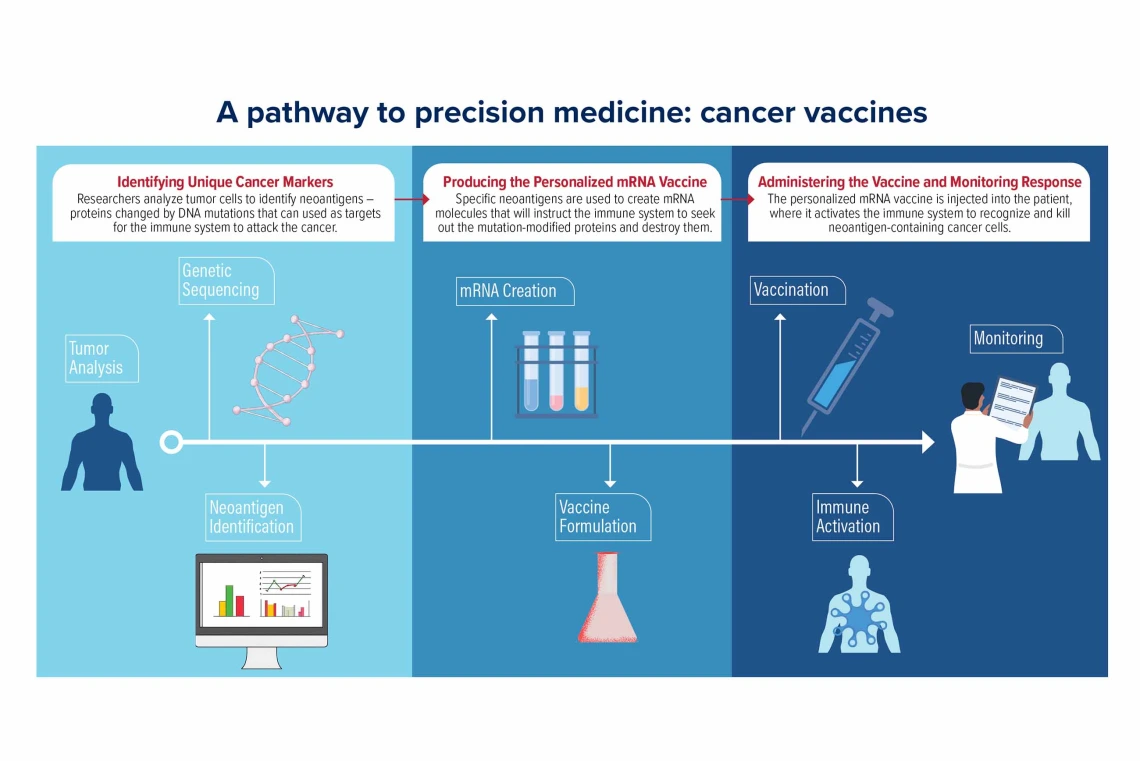

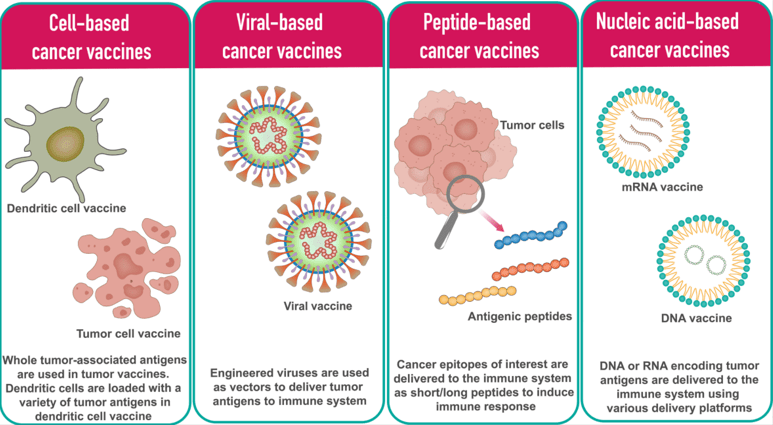

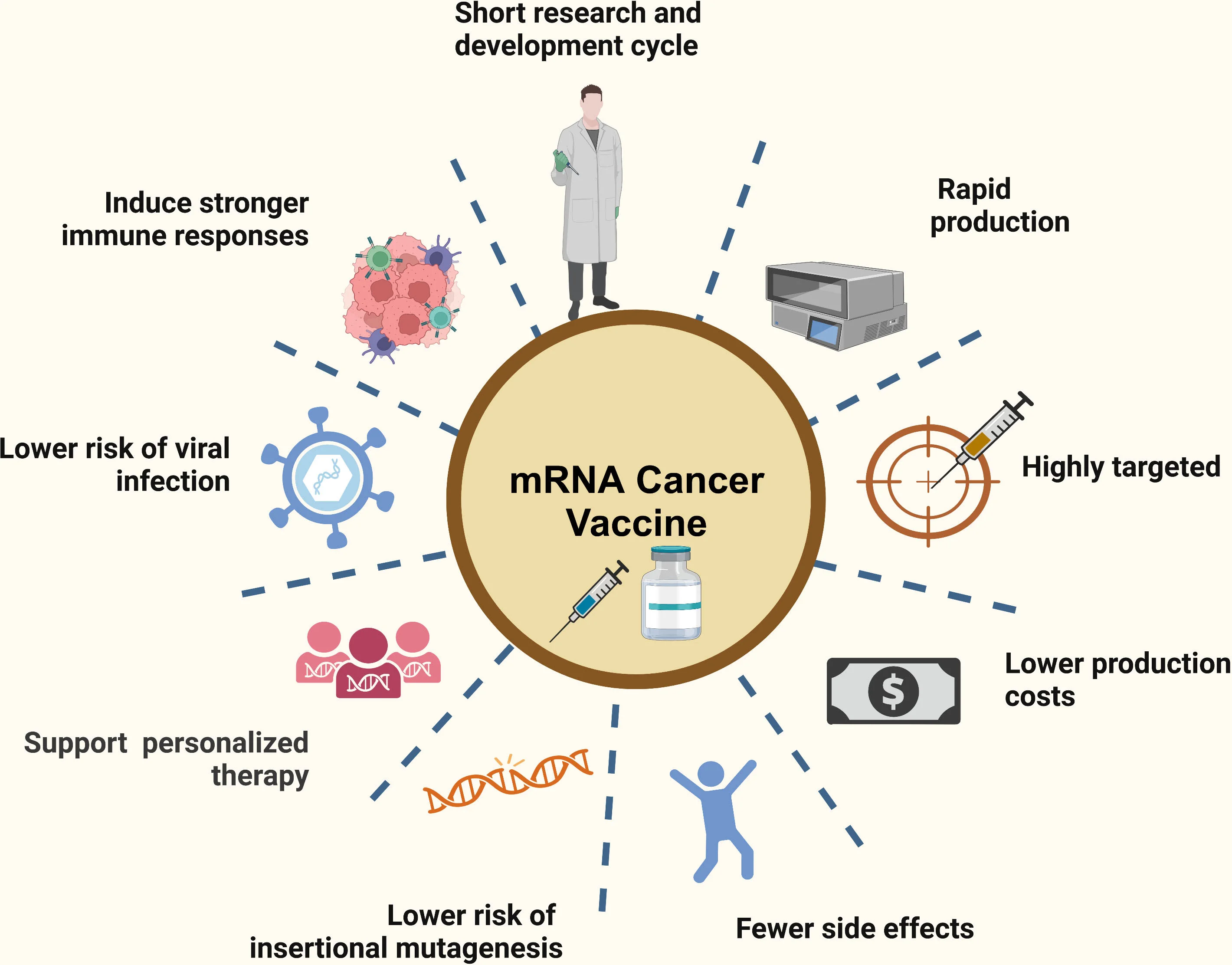

How Personalized mRNA Cancer Vaccines Actually Work

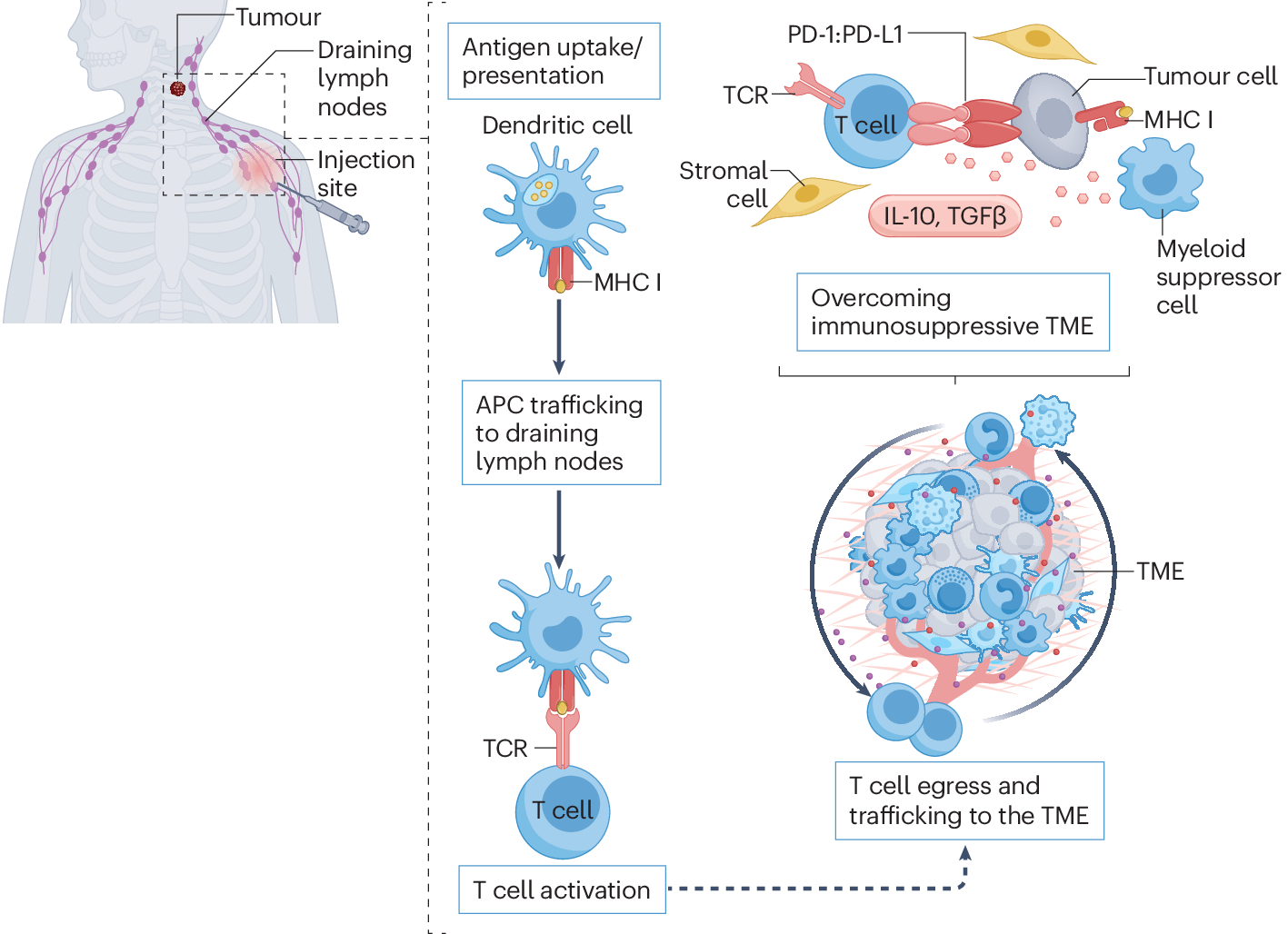

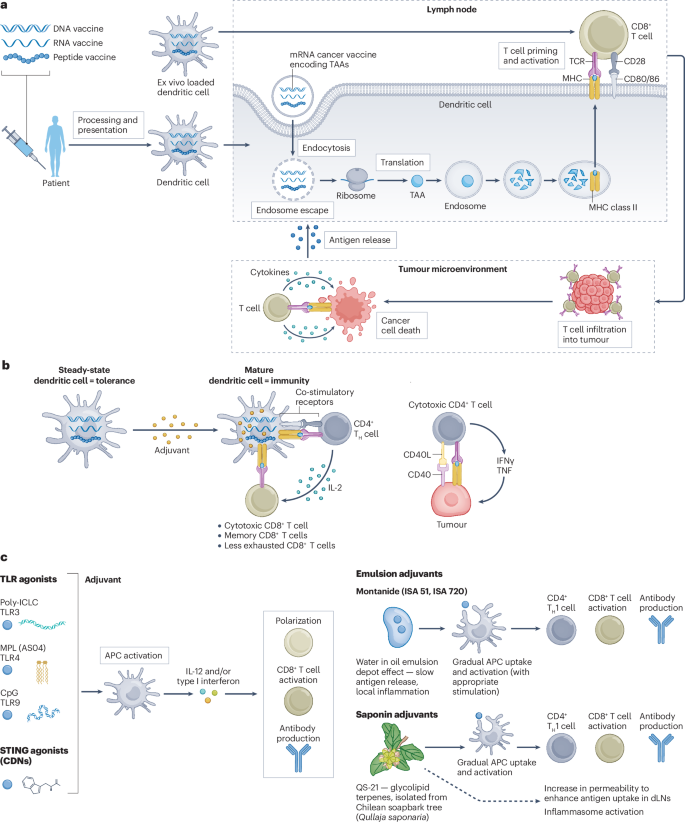

Before you can understand how these vaccines prevent cancer recurrence, you need to grasp a fundamental truth about how your immune system works: it's designed to recognize and destroy things that don't belong. The problem is that cancer cells are your own cells, just mutated. Your immune system often can't distinguish them from healthy tissue.

This is where immunotherapy typically steps in. Drugs like Keytruda (pembrolizumab), the immunotherapy used in the trial, work by removing the "off switch" that cancer cells place on immune cells. Cancer cells express a protein that binds to PD-1 receptors on T cells—essentially telling them to stand down. Keytruda blocks that interaction, keeping T cells active and ready to fight.

But here's the limitation: Keytruda doesn't teach your immune system what to look for. It just gives it permission to attack. If your immune cells don't already recognize cancer cells as enemies, Keytruda alone might not be enough.

Personalized mRNA vaccines solve this problem by teaching your immune system what to hunt.

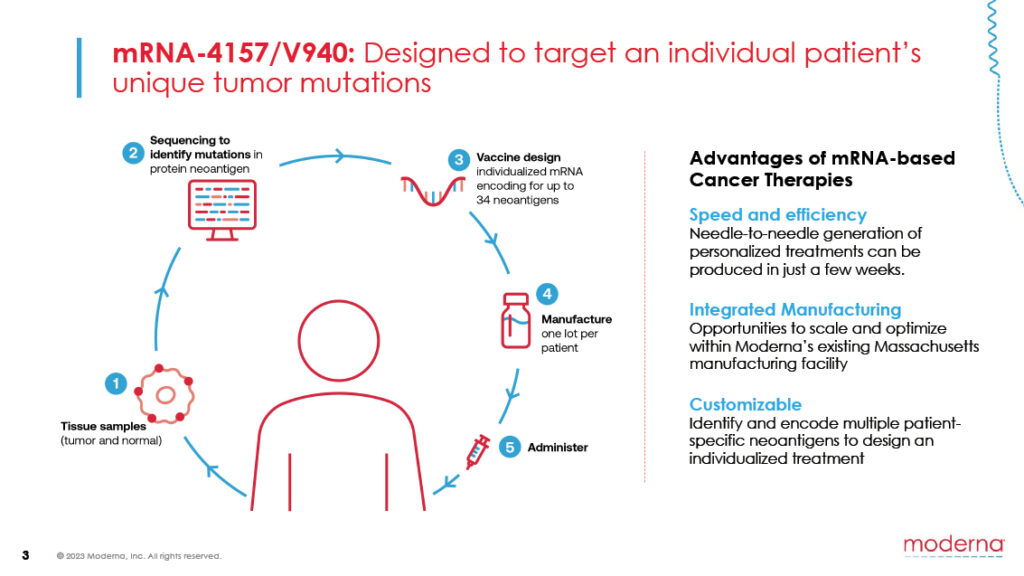

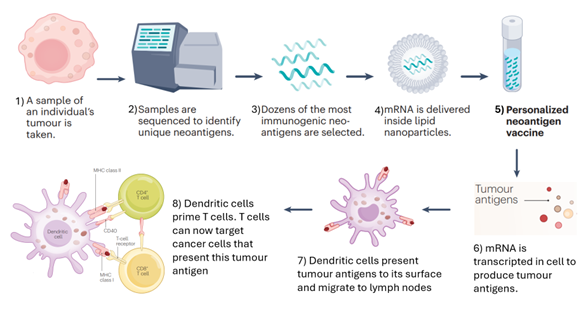

The Manufacturing Process: Sequencing the Enemy

The process begins after surgery. Surgeons remove your melanoma, and the tumor tissue goes to a lab. Technicians sequence the tumor's DNA and identify mutations that are unique to cancer cells. These mutations are what distinguish cancer from healthy tissue.

Not all mutations matter equally. The vaccine designers use sophisticated algorithms to identify which mutations are most likely to trigger an immune response. They're looking for mutations that: (1) are present in cancer cells but not in healthy tissue, (2) trigger strong T cell recognition, and (3) are unlikely to result in immune escape (where cancer cells evade the immune attack by shedding the markers).

Once they've identified the target mutations, usually 20 to 34 distinct cancer-specific markers, they design the mRNA sequence. This is where the name mRNA comes in: messenger RNA. It's genetic code that instructs your cells to produce proteins corresponding to those cancer markers.

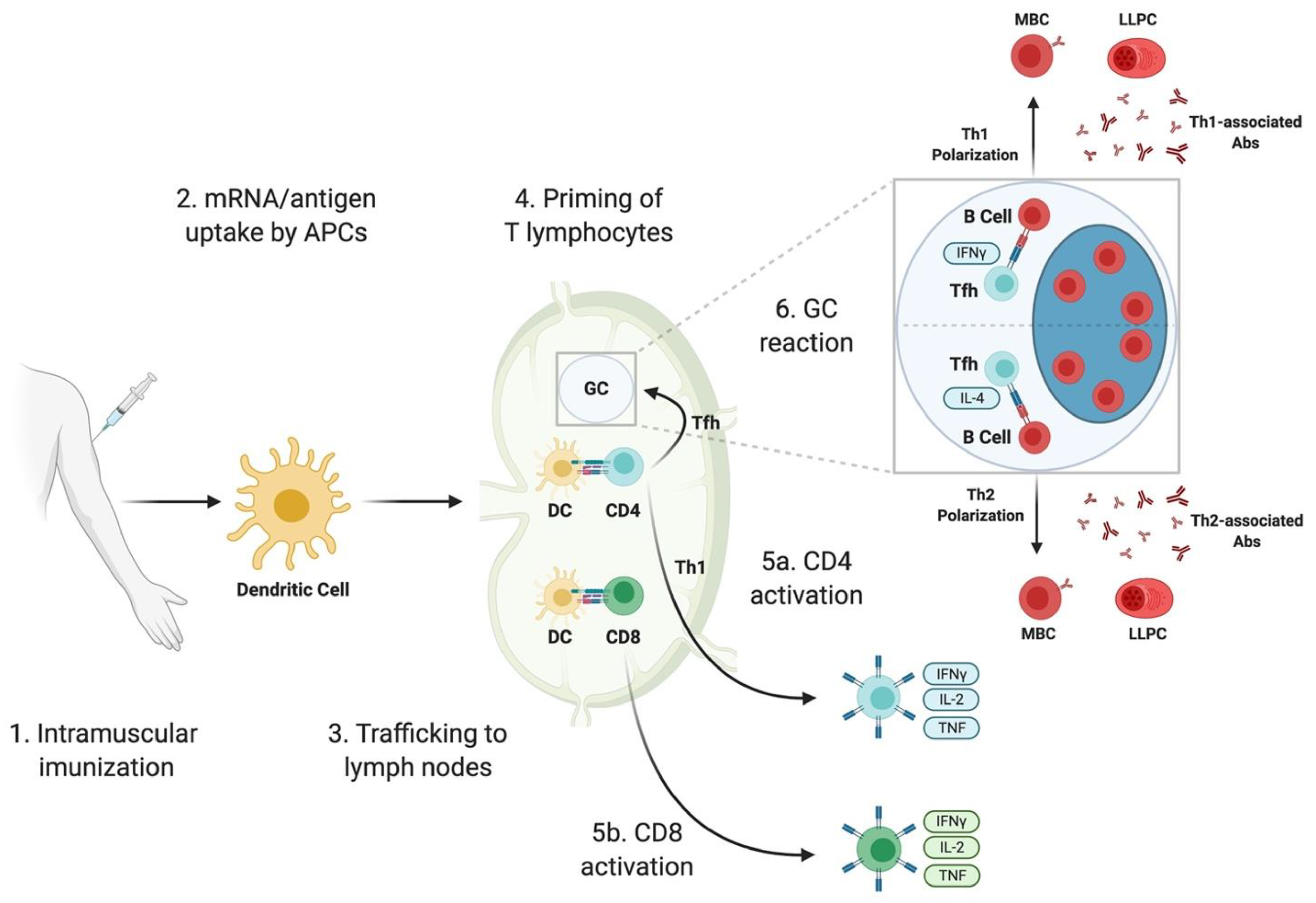

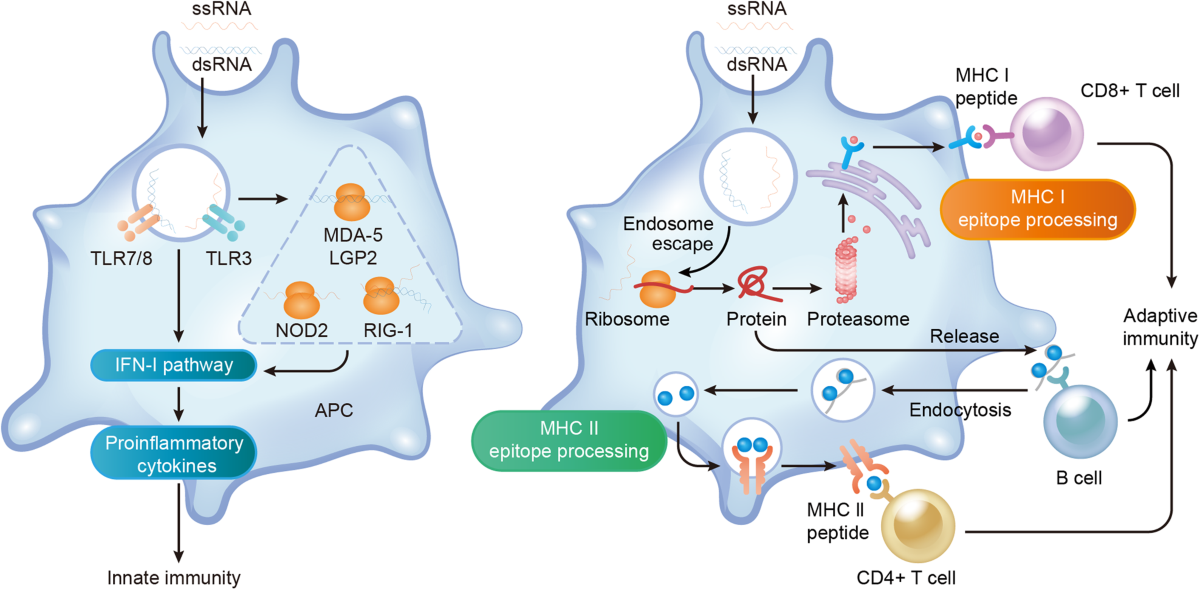

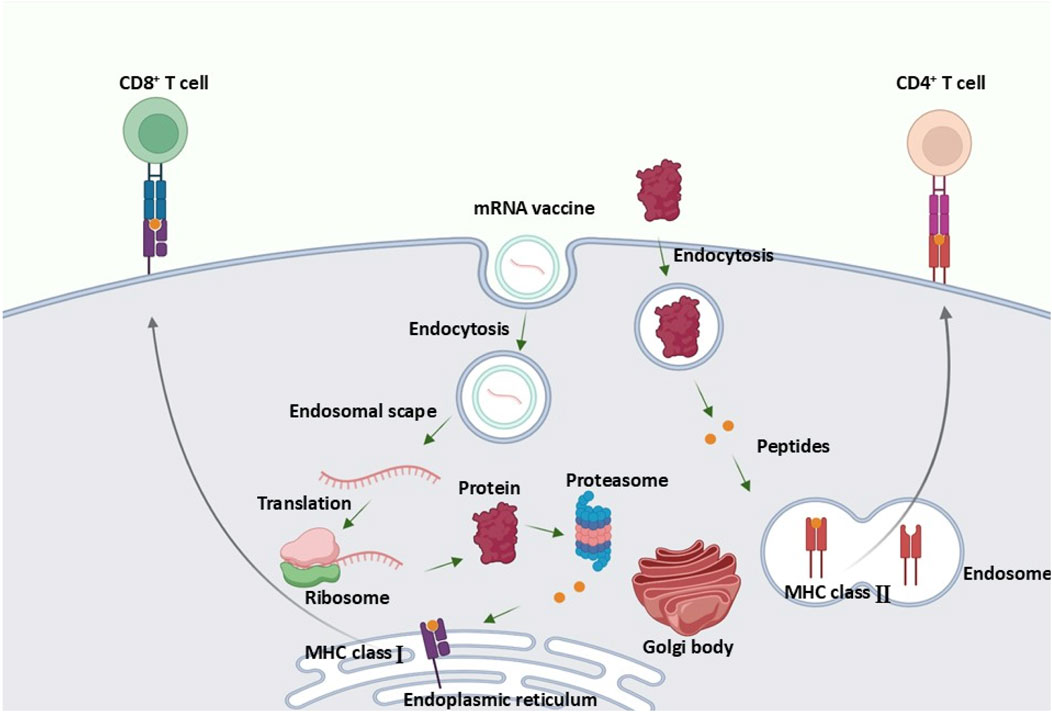

What Happens Inside Your Body

Once injected, the mRNA vaccine enters your cells, particularly immune cells called dendritic cells. These cells are essentially your immune system's training officers. They read the mRNA instructions and produce the cancer markers—the proteins your cancer cells make.

Dendritic cells then display these markers to T cells, essentially saying, "This is what we're hunting." T cells examine the markers and, if they recognize them as threats, activate and multiply. You're now training an army of immune cells to specifically recognize and destroy cells carrying those markers.

When combined with Keytruda, the effect amplifies. Keytruda removes the brake that cancer cells place on T cells, while the vaccine provides the target. It's a one-two punch: teach your immune system what to fight, then free it to fight.

The process takes weeks to establish, but once it does, the immune memory persists. This is critical. Memory T cells can last for years or even decades, which is why the five-year follow-up data showing sustained protection is so significant.

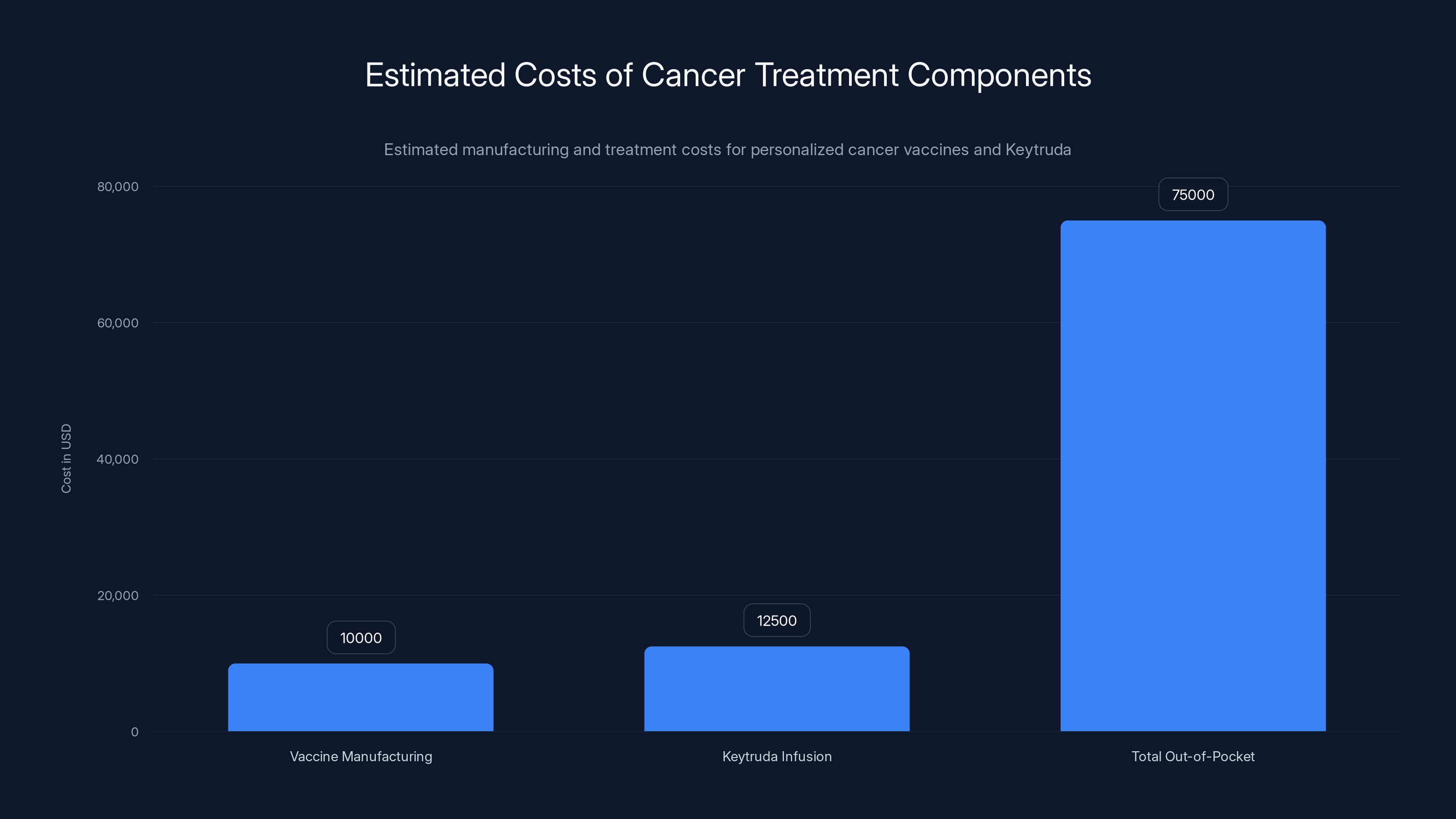

Estimated data shows that the total out-of-pocket cost for cancer treatment, including personalized vaccines and Keytruda, can range from

The Clinical Trial: What the Data Actually Shows

Understanding the trial design is crucial for interpreting what the results mean. This wasn't a vaccine-alone study. It was a vaccine-plus-immunotherapy study, which is important because it shows whether the vaccine adds benefit to existing standard care.

Trial Structure and Patient Population

The Phase 2 trial enrolled 157 patients with stage 3 or stage 4 melanoma who were at high risk of recurrence after surgical removal. All patients received Keytruda, the standard-of-care immunotherapy. They were then randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio: 107 patients got the personalized mRNA vaccine plus Keytruda, while 50 patients received only Keytruda.

This is a critical design choice. By giving everyone Keytruda, the researchers ensured a fair comparison. The question wasn't "Does the vaccine work?" but rather "Does the vaccine add benefit to standard care?"

The patient population matters too. These weren't early-stage melanomas with excellent prognosis. These were stage 3 and 4 patients—people at genuine risk of recurrence. For context, without any treatment, about 40% of stage 3 melanoma patients experience recurrence or death within five years.

The Five-Year Results: Breaking Down the Numbers

The companies didn't release granular data in their press release, but they reported the top-line result: a 49% reduction in risk of recurrence or death at the five-year mark.

What does that mean in practice? Let's use the two-year data, which was more detailed. At two years:

- Vaccine + Keytruda group: 24 of 107 patients (22%) had recurrence or death

- Keytruda alone group: 20 of 50 patients (40%) had recurrence or death

This represents a 44% relative risk reduction at two years. At three years, the risk reduction was 49%. At five years, it remained at 49%.

Here's why that matters: the protection didn't erode. Usually, when something works in the short term, benefit diminishes over time. But these numbers stayed stable from year three to year five. That's evidence of durable immune memory.

The Safety Profile: Side Effects Were Minimal

One concern with any vaccine is safety. But the adverse event data from the trial showed no surprising toxicities. The most common side effects were:

- Fatigue: Reported by some patients, typically mild to moderate

- Injection site pain: Local reactions at the injection site

- Chills: Short-lived systemic symptoms, usually resolved within hours

These side effects are remarkably similar to what people experience with the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. More importantly, they're similar between the two groups. The vaccine didn't introduce new safety concerns; it just added typical immune system activation symptoms on top of what Keytruda already causes.

There were no treatment-stopping toxicities attributable to the vaccine. No unexpected organ damage. No severe immune-related adverse events. For context, some cancer treatments carry genuinely brutal side effect profiles. This isn't one of them.

The Biology Behind the Breakthrough: Why This Works Better

The 49% risk reduction didn't happen by accident. It happened because of specific biological principles that make personalization so powerful in cancer treatment.

Tumor Heterogeneity and the Neoantigen Advantage

Every cancer is different at the genetic level. Two patients might both have melanoma, but at the mutation level, their tumors are unique. This is called tumor heterogeneity, and it's both a curse and an opportunity.

It's a curse because it means drugs that work for one patient might not work for another. It's an opportunity because it means you can exploit those unique mutations as personalized targets.

The mutations that the vaccine targets are called neoantigens—new antigens created by tumor mutations. Because they're unique to cancer cells and don't exist in healthy tissue, the immune system can recognize them without autoimmune consequences. This is huge. It means you can teach T cells to recognize cancer specifically, without worrying that they'll attack healthy cells.

Traditional cancer vaccines use shared tumor-associated antigens—markers found on multiple cancers. These are safe but less powerful because they've likely already been ignored by the immune system (that's why the cancer grew in the first place). Neoantigen vaccines are personalized to each tumor's unique mutations, making them genuinely novel to each patient's immune system.

Clonal Evolution and the Mutation Load Problem

Here's a complication: tumors evolve. Cancer cells with more mutations often develop faster because more mutations mean more diversity for natural selection to work with. This is why high-mutation tumors are sometimes called "high-burden" cancers.

For melanoma specifically, UV exposure causes thousands of mutations. This is actually good for the vaccine approach because it means there are more neoantigen targets. But it also means that by the time the cancer recurs, some cells might have additional mutations that aren't in the vaccine's target list.

The trial results suggest this isn't a major problem, at least over five years. The vaccine protected against recurrence robustly. This might be because: (1) the vaccines target 20-34 distinct markers, so even if some cancer cells acquire additional mutations, many targets remain present, (2) the T cell response is polyclonal (many different T cells targeting many different markers), making immune escape harder, or (3) the immune system itself is flexible enough to respond to variants of the cancer cells.

The Immunotherapy Synergy: Why Combination Matters

The vaccine doesn't work alone in this trial. It works in combination with Keytruda. Why is this combination so much more effective than either approach alone?

Keytruda enables existing T cells to attack cancer. But most existing T cells haven't been trained to recognize melanoma. The vaccine trains new T cells to recognize cancer. Together, you get both quantity and quality of anti-cancer immunity.

This synergy is powerful because:

- The vaccine primes new immunity: T cells that were never trained to recognize melanoma now are

- Keytruda enables that primed immunity: The newly trained T cells can actually attack cancer instead of being suppressed

- The combination attacks multiple mechanisms: The vaccine addresses the "what to fight" problem; Keytruda addresses the "permission to fight" problem

In contrast, Keytruda alone relies on spontaneous T cell recognition, which is often weak in cancer. The vaccine alone (in theory) would activate T cells but they'd be inhibited by PD-1/PD-L1 interactions without Keytruda.

The Vaccine + Keytruda group showed a consistent risk reduction of recurrence or death over five years, maintaining a 49% reduction at the five-year mark compared to Keytruda alone.

Comparison: How This Vaccine Approach Differs from Traditional Cancer Treatments

To appreciate what makes this vaccine special, it's worth comparing it to other post-surgical melanoma treatments.

Vaccine Approach vs. Immunotherapy Alone

Standard Keytruda (immunotherapy alone):

- Works by removing the brake on existing T cells

- Doesn't teach immune system new targets

- Works well if patient has strong spontaneous anti-tumor immunity

- Works poorly if tumor is immunologically "cold" (doesn't attract immune cells)

- Effect size varies widely based on tumor characteristics

Vaccine + Keytruda:

- Works by teaching T cells new targets AND removing brakes

- Targets neoantigens unique to each tumor

- Works even if tumor was initially immunologically cold

- More consistent results across patients

- Takes weeks to establish but provides durable memory

Vaccine Approach vs. Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy (historically used for high-risk melanoma):

- Direct toxicity to rapidly dividing cells

- Non-specific targeting (kills cancer and healthy cells alike)

- Significant side effects: nausea, hair loss, immunosuppression

- Limited durability beyond treatment period

- Less effective than modern immunotherapy

Vaccine + Keytruda:

- Specific targeting of cancer-unique mutations

- Side effects limited to immune system activation

- Durable protection through immune memory

- More effective than chemotherapy in modern trials

- Works with patient's own immune system

Vaccine Approach vs. Interferon Alpha

Interferon alpha (older adjuvant treatment for melanoma):

- Non-specific immune stimulation

- Significant flu-like side effects

- Modest benefit (10-15% reduction in recurrence)

- Requires long treatment duration

- Poorly tolerated

Vaccine + Keytruda:

- Targeted immune stimulation at specific tumor antigens

- Mild side effects

- Stronger benefit (49% reduction in recurrence)

- Shorter treatment duration

- Well-tolerated

| Treatment | Mechanism | Side Effects | Efficacy | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keytruda alone | Checkpoint inhibition | Immune-related, manageable | Moderate | Ongoing |

| Vaccine + Keytruda | Targeted immunity + checkpoint inhibition | Mild (fatigue, site pain) | 49% risk reduction | Weeks to establish |

| Chemotherapy | Cytotoxic | Severe (nausea, hair loss) | Limited | Treatment period |

| Interferon | Non-specific stimulation | Severe (flu-like) | Weak (10-15%) | Months |

The Manufacturing Reality: Why Personalization Is Complex

The five-year results are impressive, but they obscure a hard truth: manufacturing personalized mRNA vaccines is extraordinarily difficult. Understanding these challenges is crucial for understanding why these vaccines might not become ubiquitous overnight.

The Sequencing Bottleneck

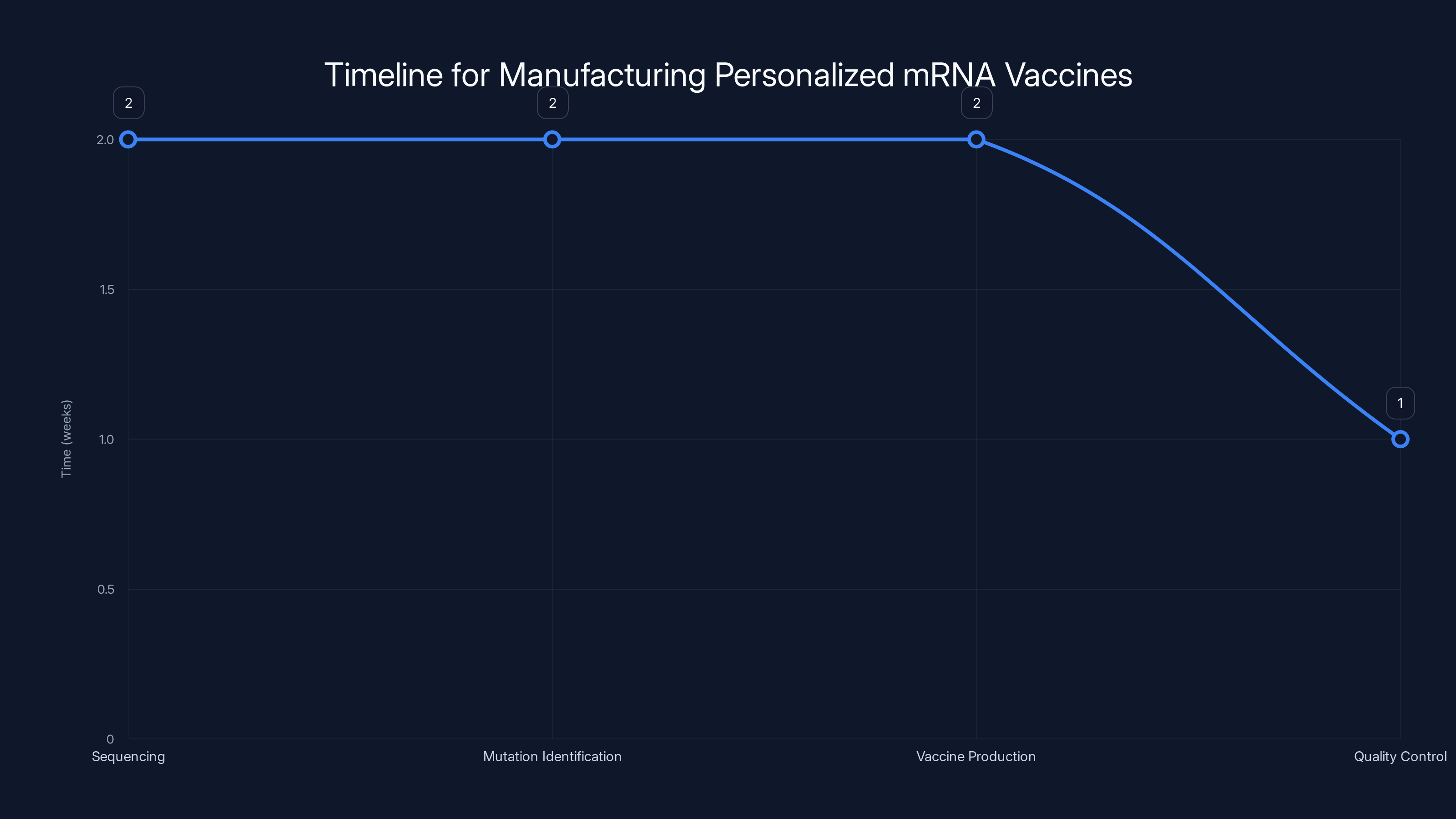

Each vaccine starts with tumor sequencing. This requires surgeons to obtain sufficient tumor tissue (not always straightforward), lab technicians to extract DNA reliably, and sequencers to generate high-quality data. Then, bioinformaticians must identify mutations that are cancer-specific and likely immunogenic.

This entire process currently takes 4-8 weeks. For some cancers, that's fine. For others, where metastasis happens fast, that timeline creates pressure. If a patient shows signs of recurrence while waiting for their vaccine, the treatment rationale changes.

The cost is also substantial. Manufacturing a personalized vaccine isn't like making Keytruda in bulk. Each one is custom. Labor, sequencing, manufacturing, quality control, all happen at small scale.

The Immunogenicity Prediction Problem

Here's a subtle issue: predicting which mutations will trigger strong T cell responses is still partly an art. Scientists use algorithms trained on genomic data, but individual variation in HLA (the system that presents antigens to T cells) means what works for one patient might not work for another.

The current approach handles this by including 20-34 neoantigen targets. The logic is that with that many targets, enough will trigger responses even if some don't. This works, as the data shows, but it's not elegant. More sophisticated prediction algorithms might eventually allow targeting fewer, more immunogenic neoantigens.

The Cold Chain Requirement

mRNA is fragile. It degrades rapidly at room temperature. All mRNA products require ultra-cold storage (around minus 70 degrees Celsius). This creates logistical challenges for manufacturing, transportation, and clinical use.

Moderna has worked on formulations that are more stable, but currently, the vaccine requires specialized cold chain management. For a treatment delivered in specialized cancer centers, this is manageable. For widespread use, it's a constraint.

The Manufacturing Time

Current manufacturing takes 2-4 weeks once sequencing is complete. As demand increases and companies optimize manufacturing, this will improve. But it won't become instantaneous. Personalization requires time.

For comparison, Merck's cancer vaccines and Johnson & Johnson's cancer programs are also exploring personalized approaches, and they face the same timeline constraints.

The manufacturing process for personalized mRNA vaccines takes approximately 7 weeks, with sequencing and mutation identification being the most time-consuming stages. Estimated data.

Expanding Beyond Melanoma: The Pipeline of Future Trials

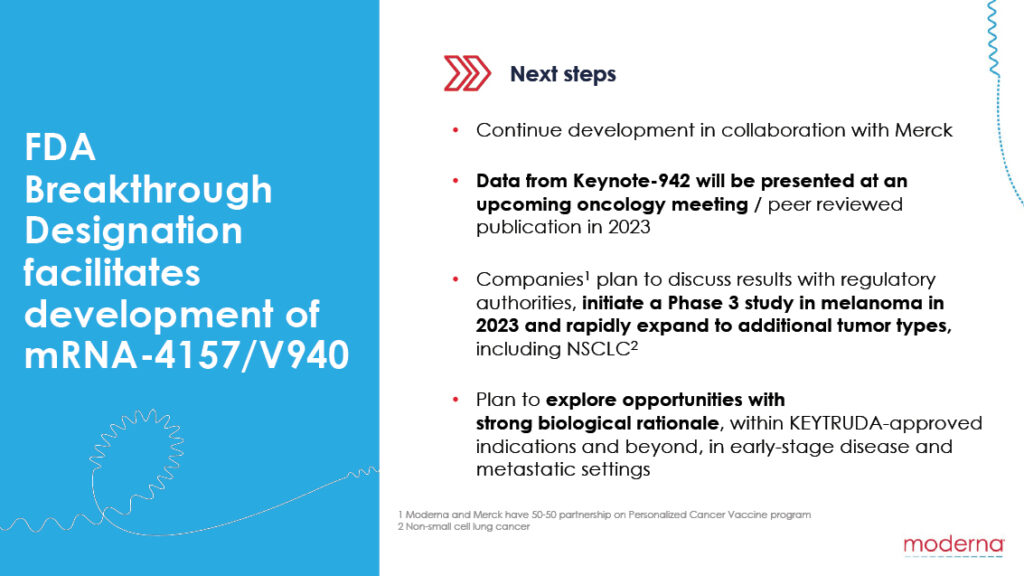

The melanoma results are impressive, but they're also the first domino. Moderna has eight additional Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials underway for other cancer types.

Lung Cancer: The Biggest Opportunity

Lung cancer kills more people than any other cancer type. If personalized mRNA vaccines work in lung cancer like they do in melanoma, the impact would be enormous.

Lung cancer actually has advantages over melanoma for this approach. Smokers develop high-mutation lung cancers, giving the vaccine more neoantigen targets. Non-smokers with lung cancer have fewer mutations, which could be a limitation, but early-stage lung cancers often have time for vaccine manufacturing before recurrence risk escalates.

Early data (not yet published in full form) suggests potential benefit, which is why Phase 3 trials are advancing. These trials will tell us whether a 49% risk reduction in melanoma translates to other cancers.

Kidney and Bladder Cancer

Both of these cancer types frequently develop high-mutation burdens, making them good candidates for neoantigen vaccination. Both have poor prognoses at advanced stages, making any improvement meaningful.

Kidney cancer trials are particularly important because kidney cancer doesn't respond well to chemotherapy. Immunotherapy (like Keytruda) helps, but benefit is limited. A personalized vaccine could meaningfully expand the patient population that benefits from immunotherapy.

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is common and often deadly when advanced. But many colorectal cancers have specific mutational signatures (like mismatch repair deficiency) that might make them good vaccine targets. Early trials will clarify this.

Ovarian, Pancreatic, and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

These cancers are historically treatment-resistant. If personalized vaccines can improve outcomes in these disease types, even modestly, the benefit would be transformative.

Pancreatic cancer, in particular, is desperately in need of new approaches. Five-year survival is under 10%. If a vaccine approach could improve that, it would be one of oncology's major advances.

The Regulatory Pathway: How This Vaccine Gets to Patients

The five-year data is impressive, but impressive data doesn't immediately translate to patient access. The regulatory pathway is complex.

Current Status: Phase 2 Complete, Phase 3 Underway

The melanoma trial that generated the five-year data is a Phase 2 trial—the stage where initial efficacy is evaluated in limited numbers. The companies now have Phase 3 trials running, which are much larger and designed to confirm benefit in broader populations.

Phase 3 trials take years. They typically involve hundreds or thousands of patients across multiple clinical centers. They must meet pre-specified endpoints with statistical rigor. Only after Phase 3 success would the company file for regulatory approval with bodies like the FDA.

The Accelerated Approval Pathway

There's a faster route: accelerated approval. If the FDA determines that a treatment addresses an unmet medical need and shows substantial improvement over existing therapy, it can grant accelerated approval based on Phase 2 data.

For personalized mRNA cancer vaccines, this pathway is plausible. The five-year data from Phase 2 is substantial. Melanoma is a serious disease with limited good options. The safety profile is favorable. An accelerated approval filing could happen, potentially allowing patient access before Phase 3 completion.

If accelerated approval occurred, the company would still conduct Phase 3 trials to confirm benefit. But patients could access the vaccine years earlier.

Manufacturing and Supply

Even with regulatory approval, supply would be constrained initially. Manufacturing personalized vaccines at scale is difficult. Capacity would start limited and expand gradually as companies build manufacturing infrastructure.

This will naturally create a tiering of access: patients at major cancer centers with trial connections would have access first. Broader access would develop over time.

The Vaccine + Keytruda approach shows a higher reduction in recurrence (49%) compared to Keytruda alone, chemotherapy, and interferon alpha, with milder side effects. Estimated data.

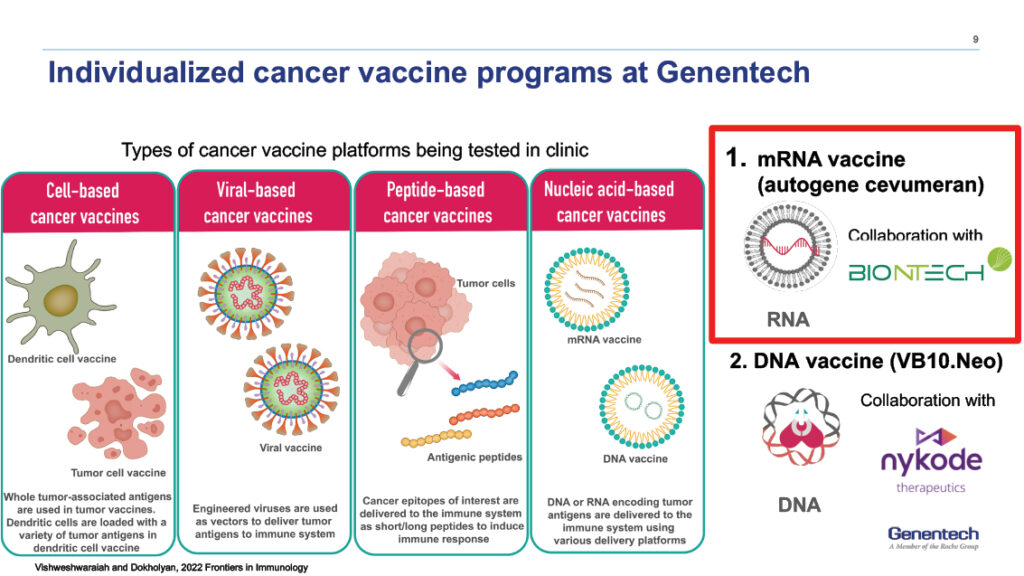

Comparing to Other Neoantigen Approaches: The Broader Landscape

Moderna and Merck aren't the only companies pursuing personalized neoantigen vaccines. The broader landscape includes competitors and complementary approaches.

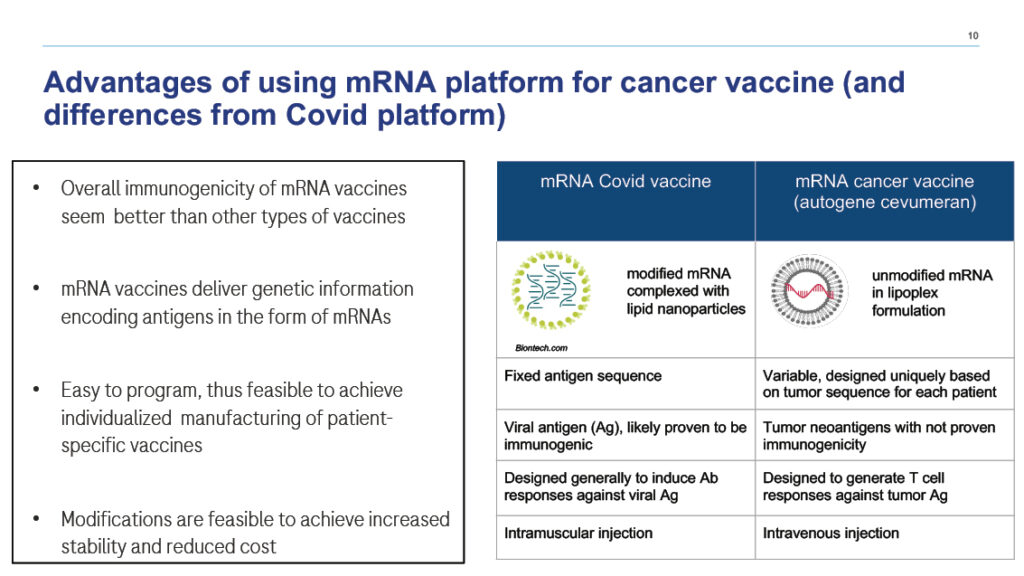

BioNTech and Pfizer's BNT122

BioNTech, in partnership with Pfizer, is developing BNT122, a personalized neoantigen vaccine combined with Merck's Keytruda. Early data suggests benefit similar to Moderna's approach.

The key difference: BioNTech uses a somewhat different vaccine design and manufacturing process. Whether one approach ultimately proves superior remains unclear, but competition in this space is healthy for pushing innovation.

Gritstone Bio and GSK Collaboration

Gritstone is working with GlaxoSmithKline on personalized cancer vaccines. Their approach emphasizes HLA-binding prediction and manufacturing efficiency.

Neon Therapeutics (Now Part of BioDecodics)

Neon developed early neoantigen vaccines and was acquired by BioDecodics. The team and technology live on, but as part of a larger platform.

How They Compare

| Company | Approach | Partner | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderna | mRNA platform, personalized neoantigens | Merck | Phase 2 complete, Phase 3 underway |

| BioNTech/Pfizer | mRNA platform, optimized formulation | Merck | Phase 2 ongoing, Phase 3 planned |

| Gritstone | Personalized, AI-optimized targets | GSK | Phase 1/2 early stage |

| Neon/BioDecodics | Personalized approach | Multiple | Platform development |

All of these approaches are fundamentally similar: sequence the tumor, identify neoantigens, deliver vaccine, combine with checkpoint inhibitor. The differences are in optimization details and regulatory progress.

Cost, Access, and Economic Reality

One question the five-year data doesn't answer: who can actually afford this treatment, and will insurance cover it?

Manufacturing Cost Estimates

Exact manufacturing costs aren't publicly disclosed, but industry experts estimate

Add the cost of Keytruda (which runs about

For context, some cancer treatments cost more. For other treatments, this is unaffordable.

Insurance Coverage Prospects

If the vaccine receives FDA approval and Phase 3 data confirms Phase 2 benefits, insurance companies will likely cover it. The rationale is straightforward: if it reduces recurrence by 49%, it's cost-effective even at high cost because it prevents more expensive recurrence treatment.

But coverage doesn't happen automatically. Companies must demonstrate that the treatment is cost-effective. For mRNA vaccines, with durable benefit, cost-effectiveness models are favorable. A one-time

Global Access

In wealthy countries, insurance or government programs will likely cover approved vaccines. In middle-income and low-income countries, access will be limited by cost.

This is a broader problem in oncology: advanced treatments concentrate in wealthy nations. Global equity remains elusive, though some organizations work to expand access.

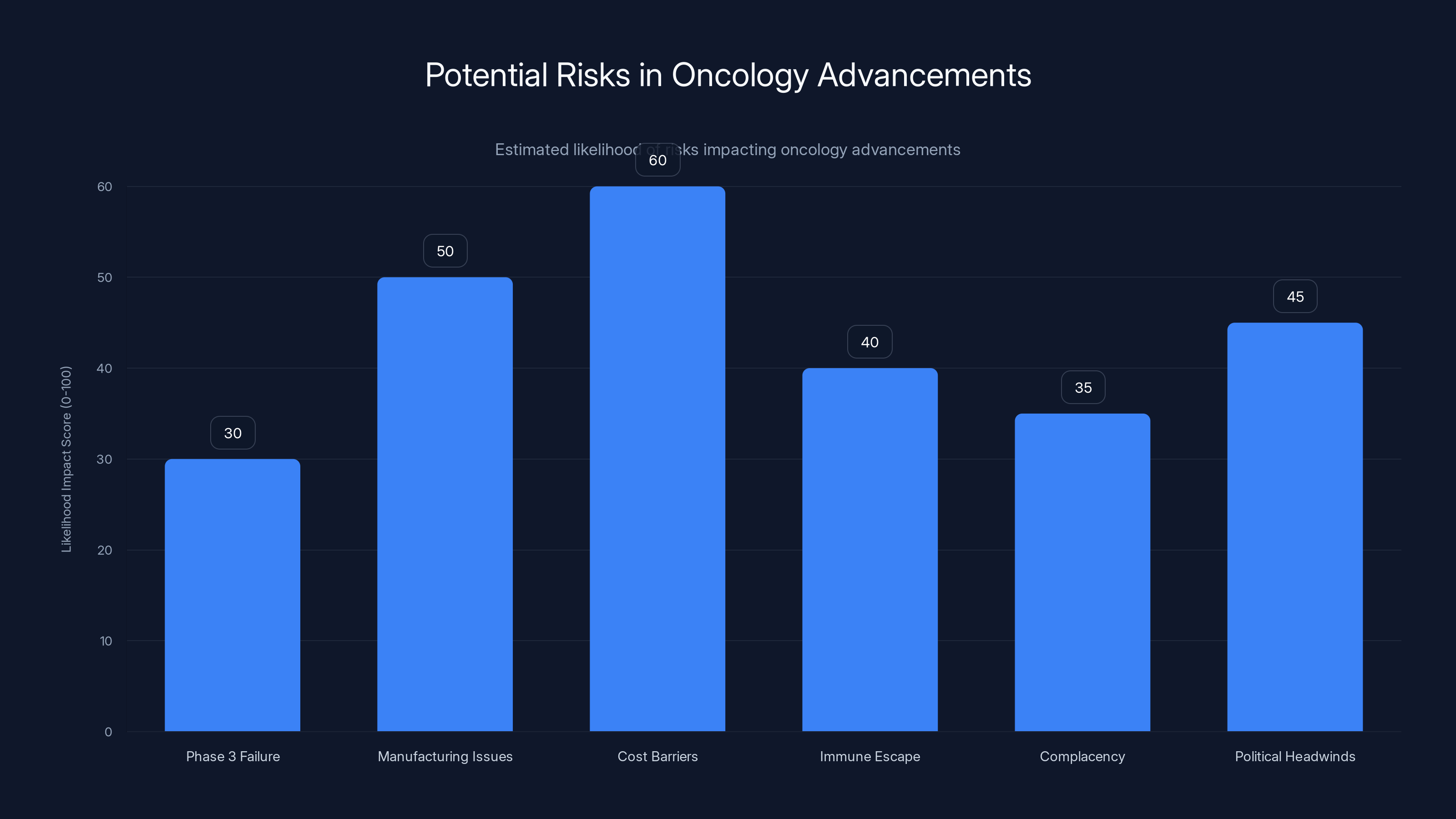

Manufacturing issues and cost barriers are estimated to have the highest impact on oncology advancements, highlighting the need for strategic planning. Estimated data.

The Political and Social Context: mRNA Vaccines and Trust

The mRNA cancer vaccine development happens in a fraught political environment. This context matters for the ultimate success of the technology.

The COVID-19 Legacy and Vaccine Skepticism

mRNA COVID-19 vaccines saved millions of lives and proved the fundamental technology works. But they also became politicized in ways that damaged public trust.

Minority populations, rightfully skeptical due to historical medical racism, sometimes avoided the vaccines. Conspiracy theorists spread false claims about rapid development and long-term effects. Even now, years later, vaccine hesitancy persists.

This skepticism threatens to spill over into cancer vaccines. Some people who refuse COVID-19 vaccines for ideological reasons will refuse cancer vaccines too, even though cancer vaccines address a life-threatening disease in a person's own body, making the risk-benefit analysis completely different.

Anti-Vaccine Health Leadership

In late 2024, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. became the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary despite a long history of anti-vaccine advocacy and statements about mRNA vaccines that contradict scientific evidence.

In August 2024, Kennedy canceled $500 million in grant funding for mRNA vaccine development targeting pandemic threats. This decision was politically motivated but creates uncertainty for future mRNA research funding.

For cancer vaccines specifically, this creates a concerning climate: research funding becomes uncertain, political pressure increases, and public trust in mRNA technology may further erode.

How This Affects Development

Unlike COVID vaccines that require population-scale rollout, cancer vaccines work within the medical system. Oncologists and cancer patients make individual decisions. The political climate matters but is less determinative.

However, funding cuts affect basic research that underlies future improvements. If mRNA vaccine research in general faces skepticism, cancer vaccine development may progress slower than it otherwise would.

The five-year results become even more important in this context: real evidence of benefit, published in reputable journals, gives the field credibility against misinformation.

The Open Questions: What We Still Don't Know

The five-year data is encouraging, but significant questions remain unanswered.

Question 1: Do Benefits Last Beyond Five Years?

We have five-year data, but not ten-year data. Does protection continue indefinitely, or does it fade? Do T cell responses persist, or do they wane?

This matters because if benefit fades after five years, patients might need booster vaccines. If it lasts indefinitely, one round of vaccination provides permanent protection.

Historically, vaccines that establish good immune memory (like measles vaccines) provide lifelong protection. mRNA vaccines have shown durable responses, suggesting long-term protection is plausible. But cancer is different than measles, and melanoma recurrence happens differently than measles reinfection.

Longer follow-up will answer this.

Question 2: Does This Work in Earlier-Stage Cancers?

The trial enrolled stage 3 and 4 melanoma patients. But stage 1 and 2 patients might benefit even more because their recurrence risk is lower to start, and any additional protection would push them close to cure.

Does the vaccine work in stage 1? Likely yes, by the same biological mechanism. But will the benefit be meaningful if baseline recurrence risk is only 10%? This requires testing.

Question 3: Does This Work Without Checkpoint Inhibition?

The trial combined the vaccine with Keytruda. What if you gave the vaccine alone? Would it work?

Theoretically, maybe. The vaccine activates T cells. Checkpoint inhibitors amplify activation. But some benefit might persist even without them, especially in younger patients with better immune function.

Future trials might test this. Some patients might be treated with vaccine alone, others with vaccine plus immunotherapy, and outcomes compared.

Question 4: Can We Predict Who Benefits Most?

Not all patients benefit equally. Some experienced recurrence anyway despite treatment. Can we identify which patients will respond best to personalized vaccines?

Factors that might matter include: tumor mutation load, HLA type (affects antigen presentation), immune cell composition in the tumor, patient age and health status, and maybe genetic factors we don't yet understand.

Biomarker discovery will make this field more precise. Instead of offering everyone the vaccine, we might eventually identify which patients have the highest probability of benefit.

Question 5: What's the Escape Mutation Risk?

Theoretically, cancer could evolve to escape the vaccine by acquiring mutations that eliminate the targeted neoantigens. This might happen after months or years.

Why hasn't this been a major problem in the trial? Several possibilities: (1) the vaccine targets so many neoantigens that escape is difficult, (2) the tumor cells have mutational constraints that prevent escape, or (3) the combination with Keytruda is effective enough that escape cells are killed before expansion.

Understanding this mechanism will help predict long-term durability.

The Path Forward: What Happens Next

Assuming Phase 3 trials succeed (which is plausible given Phase 2 results), the regulatory timeline looks roughly like this:

2026-2028: Phase 3 data accumulates. Early interim data might support accelerated approval filing.

2027-2029: FDA grants accelerated approval, likely starting in melanoma. Vaccine becomes available at specialized centers, probably at major academic cancer centers with trial experience.

2028-2030: Manufacturing scales. Broader hospital systems gain access. Insurance coverage solidifies.

2030+: Additional cancer types receive approval. The vaccine becomes part of standard care for multiple high-risk cancers.

This timeline is ambitious but realistic. If Phase 3 doesn't confirm Phase 2 benefit, timelines slip significantly or the program pauses.

The Bigger Picture: Cancer Care Evolution

Personalized mRNA vaccines represent a shift in cancer treatment philosophy. Instead of using drugs designed for populations, you're using treatments designed for individuals.

This individualization extends beyond vaccines. Personalized tumor sequencing is becoming standard for many cancers. Targeted therapies hit specific mutations. Immunotherapies activate immune cells. Personalized vaccines train immune cells.

The next decade will likely see cancer treatment become increasingly individualized. Genomics guides therapy selection. Personalization increases efficacy and reduces unnecessary toxicity. The technology supporting this—sequencing, manufacturing, analysis—gets cheaper and faster.

Personalized mRNA cancer vaccines are early evidence of this transformation. If they fulfill their promise, they'll be among the foundational tools of modern oncology.

Critical Perspective: What Could Go Wrong

It's worth being honest about risks and limitations alongside optimism about benefits.

Risk 1: Phase 3 Failure

Phase 2 results are promising, but Phase 3 trials are larger and less controlled. They might fail to confirm Phase 2 benefits. This happens in oncology regularly. It's unlikely here, but possible.

Risk 2: Manufacturing at Scale

Current manufacturing works in research settings. Scaling to thousands of patients per year is harder. Quality consistency might suffer. Manufacturing bottlenecks might prevent broad access.

Risk 3: Cost and Access Barriers

Even if effective, high cost could limit access to wealthy patients in wealthy countries. Global equity issues might worsen, concentrating advanced cancer treatment in privileged populations.

Risk 4: Immune Escape

Cancer is clever. It might evolve faster than we expect, acquiring mutations that eliminate vaccine targets. Long-term benefit might be lower than current data suggests.

Risk 5: Complacency About Prevention

If effective vaccines create the impression that melanoma can be easily treated post-diagnosis, investment in prevention (sunscreen, UV protection) might decrease. Prevention is still cheaper and easier than treatment.

Risk 6: Political Headwinds

Antivax sentiment, political skepticism about mRNA technology, and funding cuts could slow development. Public perception matters for patient acceptance and research support.

None of these risks is fatal to the program, but they're realistic. Success isn't guaranteed. The field must remain cautiously optimistic but intellectually honest about limitations.

What This Means for Cancer Patients Today

If you or a loved one has recently been diagnosed with high-risk melanoma, what should you know?

Don't expect immediate access: Personalized mRNA vaccines aren't yet approved. They're available only in clinical trials. Talk to your oncologist about whether you're eligible for a trial.

Standard care remains effective: Keytruda (or other immunotherapies) are effective for many patients. Don't delay standard treatment hoping to wait for the vaccine.

Ask about trials: Major cancer centers are enrolling patients in Phase 3 trials. If you meet criteria (stage 3 or 4 melanoma post-surgery), ask your oncologist whether trial participation makes sense for you.

Understand the timeline: Manufacturing takes 4-8 weeks. This needs to fit into your treatment timeline. If recurrence signs emerge, you might not have time to wait.

Insurance considerations: Trial costs are typically covered by the trial sponsor and your insurance. But clarify this upfront.

Manage expectations: This vaccine is promising but not proven in routine care yet. The results are encouraging, but they come from controlled trials. Real-world effectiveness might differ.

The Bigger Story: Why This Matters Beyond Melanoma

The melanoma vaccine results capture headlines because melanoma is serious. But the broader significance extends beyond one cancer type.

These results prove that personalized cancer immunotherapy works. They show that custom-built treatments can outperform standard approaches. They demonstrate that mRNA technology, despite political controversy, delivers medical benefit.

If personalized vaccines work in melanoma, lung cancer, kidney cancer, and others, the entire framework of cancer care shifts. Instead of searching for one drug that works for many patients, oncologists design treatments for individual patients.

This is how medicine will probably look in fifty years. Personalized, genomically guided, targeted to individual tumor genetics and immune status.

The five-year melanoma data is one waypoint on that journey. A significant one, but not the destination.

FAQ

What exactly is a personalized mRNA cancer vaccine?

A personalized mRNA cancer vaccine is a custom-designed genetic treatment created specifically for each patient's individual tumor. After surgery removes the tumor, doctors sequence the cancer's DNA, identify mutations unique to that tumor, and design an mRNA vaccine carrying instructions for your immune cells to produce proteins corresponding to those cancer mutations. When injected, this vaccine trains your T cells to recognize and attack cancer cells that carry those same mutations. Each vaccine is manufactured specifically for one patient and cannot be used for anyone else.

How does the mRNA vaccine teach the immune system to recognize cancer?

The vaccine works through a carefully orchestrated biological process. When injected, the mRNA enters your cells, particularly immune cells called dendritic cells. These cells read the mRNA instructions and produce proteins corresponding to your cancer's unique mutations. The dendritic cells then display these proteins to your T cells, essentially showing them what to hunt for. T cells examine these proteins and, if they recognize them as threats, activate and multiply, creating an army of specialized cells trained to specifically target cancer cells carrying those mutations. This immune training persists for years through immune memory cells.

What does a 49% risk reduction actually mean for individual patients?

A 49% relative risk reduction translates to meaningful individual benefit, though the size varies. In the trial, about 40% of patients receiving only immunotherapy experienced recurrence or death over five years. With the vaccine added, this dropped to about 22%. That means the vaccine prevented recurrence or death in approximately 18 out of every 100 patients treated. For an individual patient, this represents nearly a 50% improvement in chances of remaining cancer-free, which is substantial for a serious disease like high-risk melanoma.

How long does manufacturing take, and could that delay treatment for rapidly advancing cancers?

Manufacturing currently takes 4-8 weeks total, including tumor sequencing, bioinformatic analysis, mRNA synthesis, formulation, and quality control. This timeline could be problematic for fast-growing cancers where recurrence develops quickly. However, for melanoma specifically, high-risk patients don't typically develop metastatic recurrence immediately after surgery, giving a window for vaccine manufacturing. As manufacturing processes improve, timelines should decrease. Some experts estimate manufacturing could be compressed to 2-3 weeks with optimization.

Will insurance companies cover personalized mRNA cancer vaccines once they're approved?

Unlike some cutting-edge treatments, personalized mRNA vaccines have favorable insurance coverage prospects. If approved vaccines demonstrate the 49% risk reduction shown in current trials, they'll be cost-effective from an insurance standpoint. A one-time personalized vaccine costing

Could cancer cells evolve mutations that escape what the vaccine targets?

This is a genuine biological concern, but current evidence suggests it's not a major problem in the medium term (at least through five years). The vaccine targets 20-34 distinct cancer-specific mutations simultaneously, making escape difficult because cancer cells would need to shed multiple mutations simultaneously. Additionally, the combination of the vaccine with Keytruda means that even cells with some mutations eliminated would still be vulnerable to Keytruda's mechanism. Long-term escape might eventually occur, potentially requiring booster vaccines, but early data doesn't show this happening in the first five years. Longer follow-up beyond five years will clarify whether escape becomes problematic over time.

Are there patient populations who shouldn't receive personalized mRNA cancer vaccines?

The current trials focused on stage 3 and 4 melanoma patients, so safety data for other populations is limited. Pregnant women shouldn't receive the vaccine pending safety data. Patients with severe immunosuppression from other diseases or medications might not mount adequate vaccine responses. Patients with active uncontrolled cancer or rapidly progressive metastatic disease might not have time for the 4-8 week manufacturing period. Patients unwilling to receive checkpoint inhibitors like Keytruda might not benefit, since current evidence supports combining these approaches. Your oncologist can assess whether you're a good candidate based on your specific situation.

What happens if the vaccine doesn't prevent recurrence? Are there other treatments?

If melanoma recurs despite the vaccine and Keytruda, additional treatment options exist. Other checkpoint inhibitors are available with different mechanisms. Targeted therapies work against specific mutations (like BRAF mutations in melanoma). Traditional chemotherapy, though less effective than immunotherapy, remains an option. Combination immunotherapies using multiple checkpoint inhibitors together sometimes work when single agents fail. Brain radiation or surgery can address brain metastases. Clinical trials for experimental treatments might be available. Modern melanoma treatment failure is serious but not hopeless—ongoing research constantly adds new options.

Conclusion: A Turning Point in Cancer Treatment

The five-year follow-up data from Moderna and Merck's personalized mRNA cancer vaccine trial represents something genuinely significant: proof that radical personalization in cancer treatment works.

The numbers are encouraging: a 49% reduction in recurrence and death risk. But the deeper significance is the confirmation that this approach fundamentally works. Custom-built vaccines, tailored to each patient's tumor genetics, can train the immune system to prevent cancer's return.

This isn't the first personalized cancer treatment—targeted therapies have existed for years. But it's the first successful personalized vaccine for cancer, opening an entirely new therapeutic domain. Instead of searching for drugs that work for thousands of patients, you're designing treatments for individuals.

The road ahead has obstacles. Manufacturing needs to scale. Cost needs to come down. Longer follow-up is needed to confirm durability. Phase 3 trials must succeed. Regulatory approval requires navigating complex processes. And the political environment around mRNA technology remains fraught despite clinical evidence of benefit.

But the Phase 2 five-year data provides a foundation. It shows that when you do the work to understand each tumor's unique genetics, when you leverage mRNA's flexibility to create custom vaccines, and when you combine targeted immunity with checkpoint inhibition, you get meaningful clinical benefit in patients with serious disease.

This is how modern cancer medicine should work. Not one-size-fits-all chemotherapy or generic immunotherapy, but personalized treatments designed for individual tumor genetics. The melanoma vaccine is an early example. If it translates to lung cancer, kidney cancer, pancreatic cancer, and others—as the pipeline suggests—the transformation of cancer treatment is underway.

For patients currently facing high-risk melanoma, this work offers hope. For oncologists designing treatment plans, it opens new possibilities. For researchers advancing the field, it validates the personalization approach. For everyone eventually facing cancer—and statistically, most of us will—it suggests better days ahead.

The five-year results aren't the end of the story. They're a beginning. They prove the concept works. Now comes the harder work: making it scalable, accessible, affordable, and durable for the millions of patients who need it.

That work has begun. And based on these five-year results, it's worth the effort.

Key Takeaways

- Personalized mRNA vaccines reduce high-risk melanoma recurrence by 49% when combined with Keytruda immunotherapy over five years

- Each vaccine is custom-designed from tumor genetic sequencing, targeting 20-34 cancer-specific mutations unique to the patient

- Manufacturing takes 4-8 weeks, requiring careful timing within treatment protocols for patients at risk of rapid recurrence

- Safety profile is favorable with mild side effects (fatigue, injection site pain) comparable to standard immunotherapy

- Moderna has eight additional Phase 2/3 trials underway extending this approach to lung, kidney, bladder, and pancreatic cancers

- Five-year data shows durable protection without benefit degradation, suggesting long-term immune memory establishment

- Cost and access will likely be managed through insurance coverage based on strong cost-effectiveness rationale

- Political skepticism about mRNA vaccines creates challenging development environment despite clinical proof of efficacy

Related Articles

- Hi-Res Music Streaming Is Beating Spotify: Why Qobuz Keeps Winning [2025]

- Windows 11 Xbox App on Arm PCs: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Apple's AI Chatbot Siri: Complete Guide & Alternatives 2026

- Claude's Revised Constitution 2025: AI Ethics, Safety & Consciousness Explained

- Todoist Ramble: Voice-Powered Task Creation Transforms Productivity [2025]

- Apple's AI Wearable: AirTag-Sized Device Explained [2025]

![mRNA Cancer Vaccines Show 49% Protection at 5-Year Follow-Up [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/mrna-cancer-vaccines-show-49-protection-at-5-year-follow-up-/image-1-1769037138245.jpg)