Commercial Genetic Testing: Understanding the Risks and Reality

You spit into a tube, mail it off, and two weeks later you get a report telling you your genetic predisposition for heart disease, depression, or even your chances of graduating college. It sounds like science. It looks like science. But here's the thing: we've collectively rushed into commercial genetic testing without actually understanding what these tests do, how accurate they are, or what happens when companies start using them to make life-altering decisions about embryos, insurance, and employment.

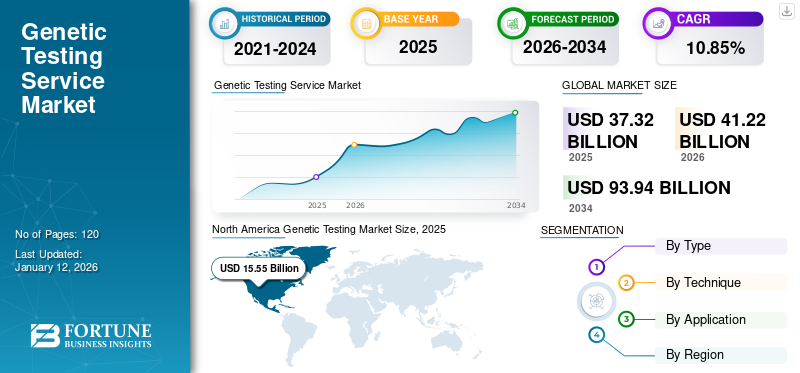

The genetic testing industry is now worth billions of dollars globally, with millions of people voluntarily submitting their DNA to companies with varying levels of oversight, varying levels of scientific rigor, and varying levels of commitment to using that data responsibly. Meanwhile, policymakers are playing catch-up, regulators are scrambling, and most consumers have no idea that a test claiming to predict their educational potential or mental health outcomes is based on science that's far messier, far less certain, and far more politically loaded than the glossy marketing suggests.

This isn't to say genetic research is useless. It's not. But there's a massive gap between what these tests can reliably do and what companies claim they can do. There's an equally massive gap between the science and the hype. And there's a chasm between the potential benefits of genetic research and the very real ways that genetic data has been weaponized throughout history to justify discrimination, inequality, and worse.

The question facing us right now isn't whether genetic testing is inherently good or bad. It's whether we're regulating it appropriately, whether we're being honest about its limitations, and whether we're prepared for the social and ethical consequences of treating probabilistic genetic predictions as facts that should guide major life decisions.

TL; DR

- Polygenic scores predict risk in populations, not individuals: These tests sum hundreds of thousands of genetic variants to estimate disease or trait likelihood, but they're probabilistic tools with serious accuracy limitations, not diagnostic tests.

- Accuracy drops dramatically for non-European ancestry groups: Because 96% of genetic studies use European participants, polygenic scores are significantly less accurate for Asian, African, and other populations, potentially widening existing health disparities.

- These tests are already reshaping human diversity through embryo selection: Companies like Genomic Prediction are offering to screen embryos for traits like height and intelligence based on polygenic scores, despite serious scientific questions about validity and ethical implications.

- Regulation is almost nonexistent: While gene editing faces intense scrutiny, polygenic scoring operates in regulatory gray zones with minimal oversight, allowing companies to market tests for conditions they're not validated for.

- Science education doesn't match reality: Most people's understanding of genetics is stuck in high school Mendelian inheritance, leaving them unprepared to evaluate claims about complex traits influenced by thousands of genes and environmental factors.

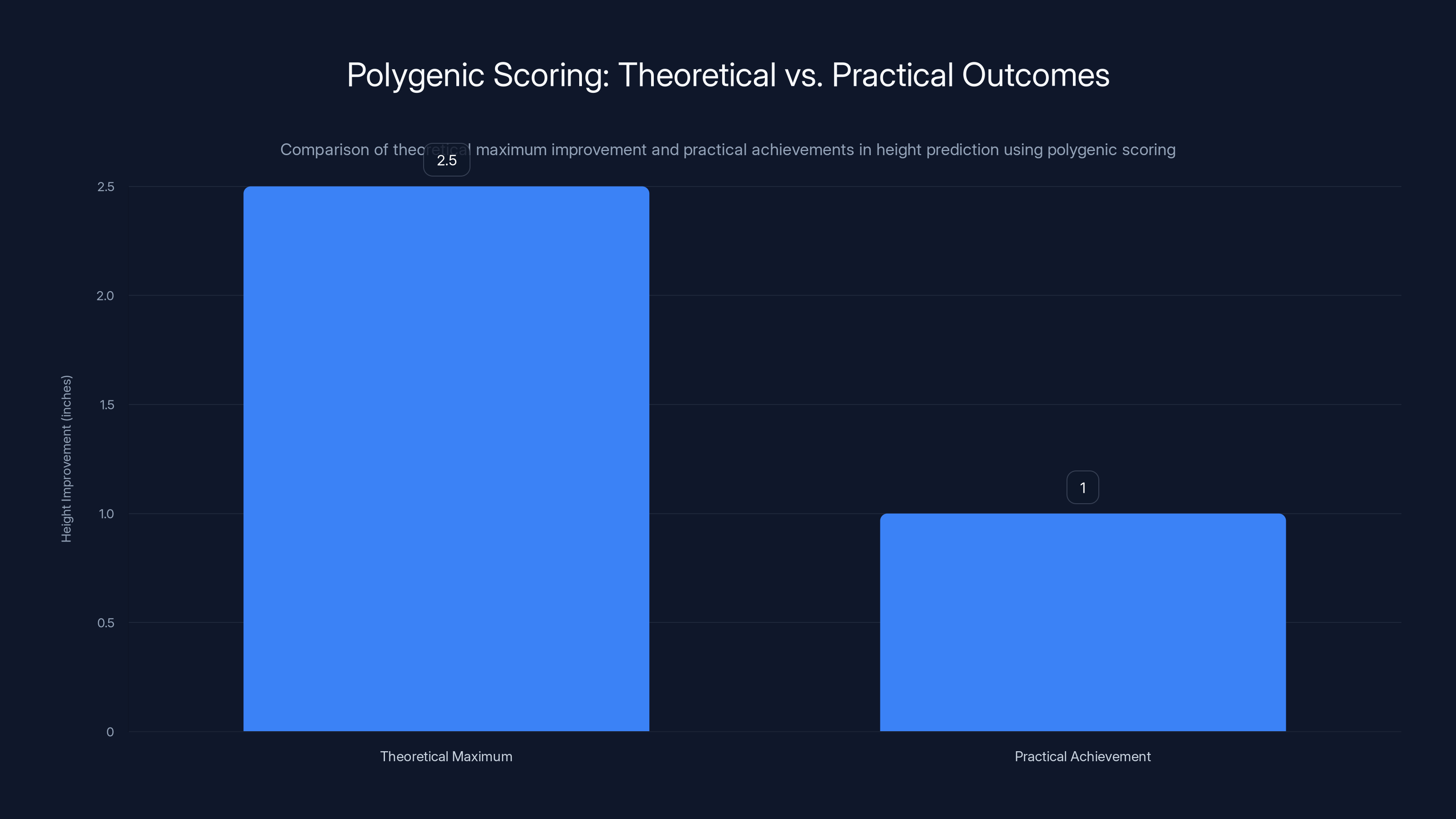

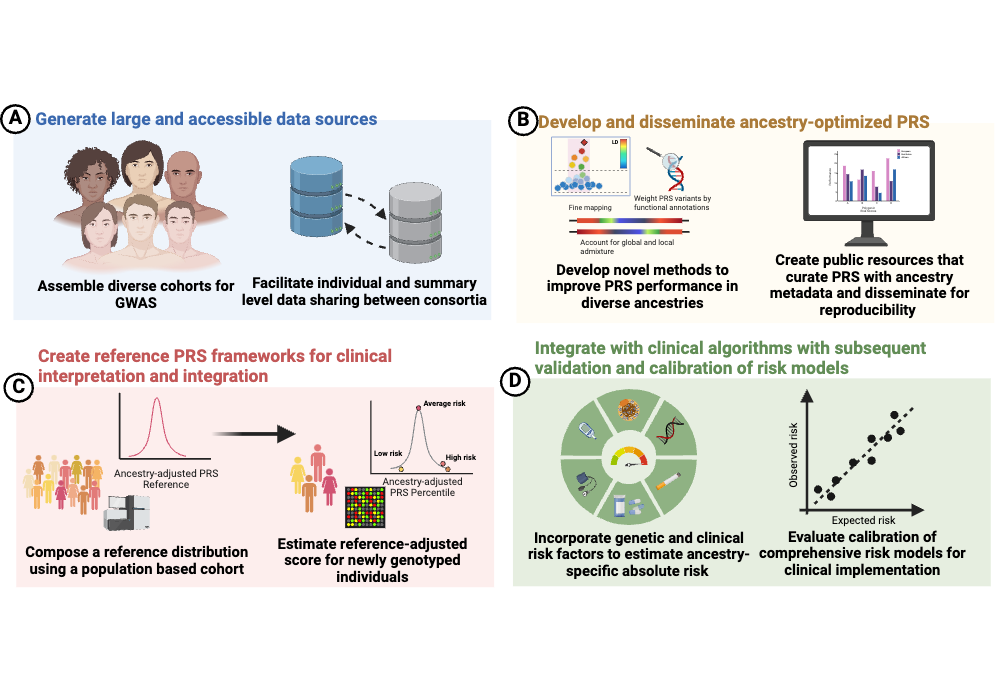

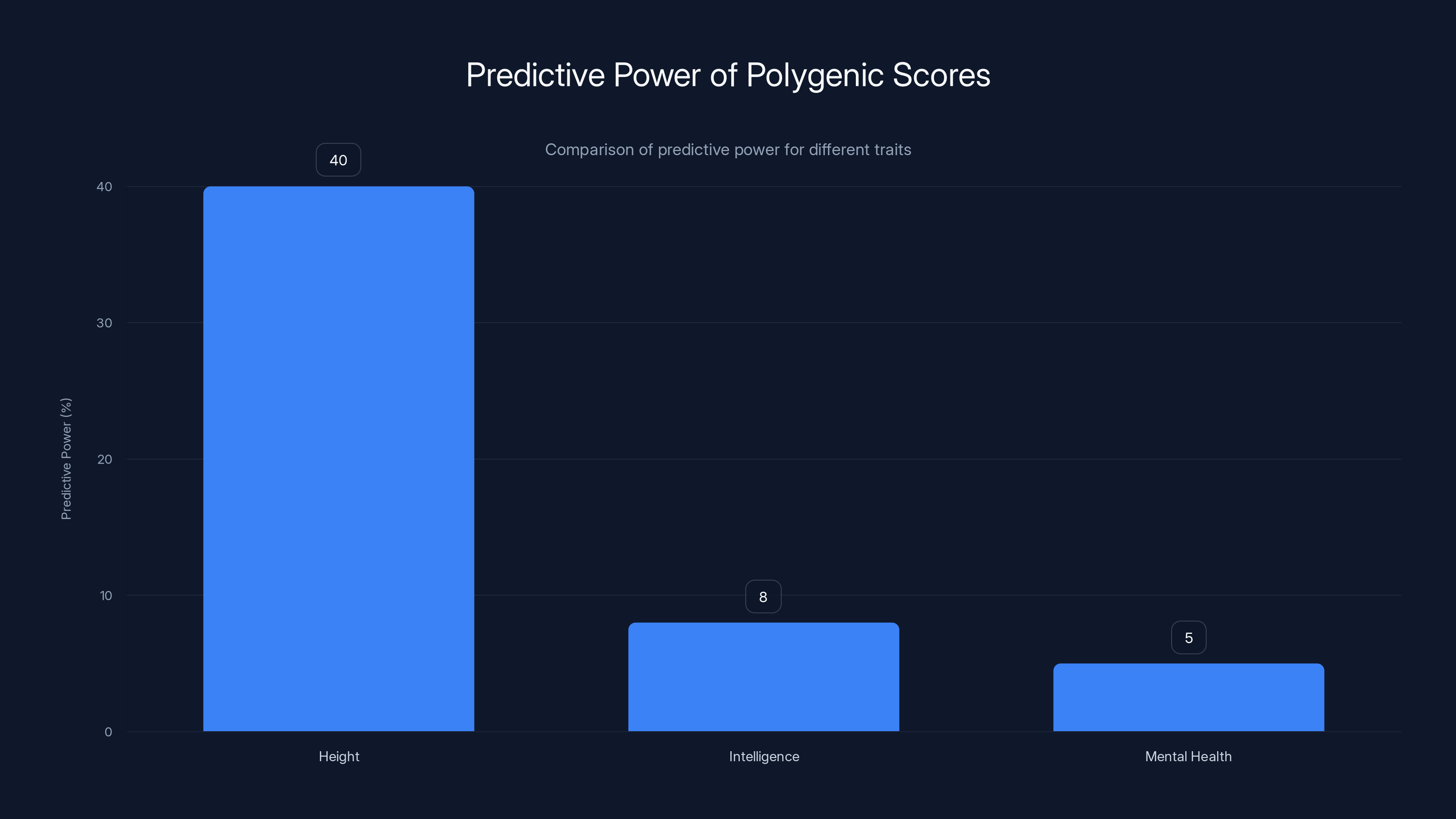

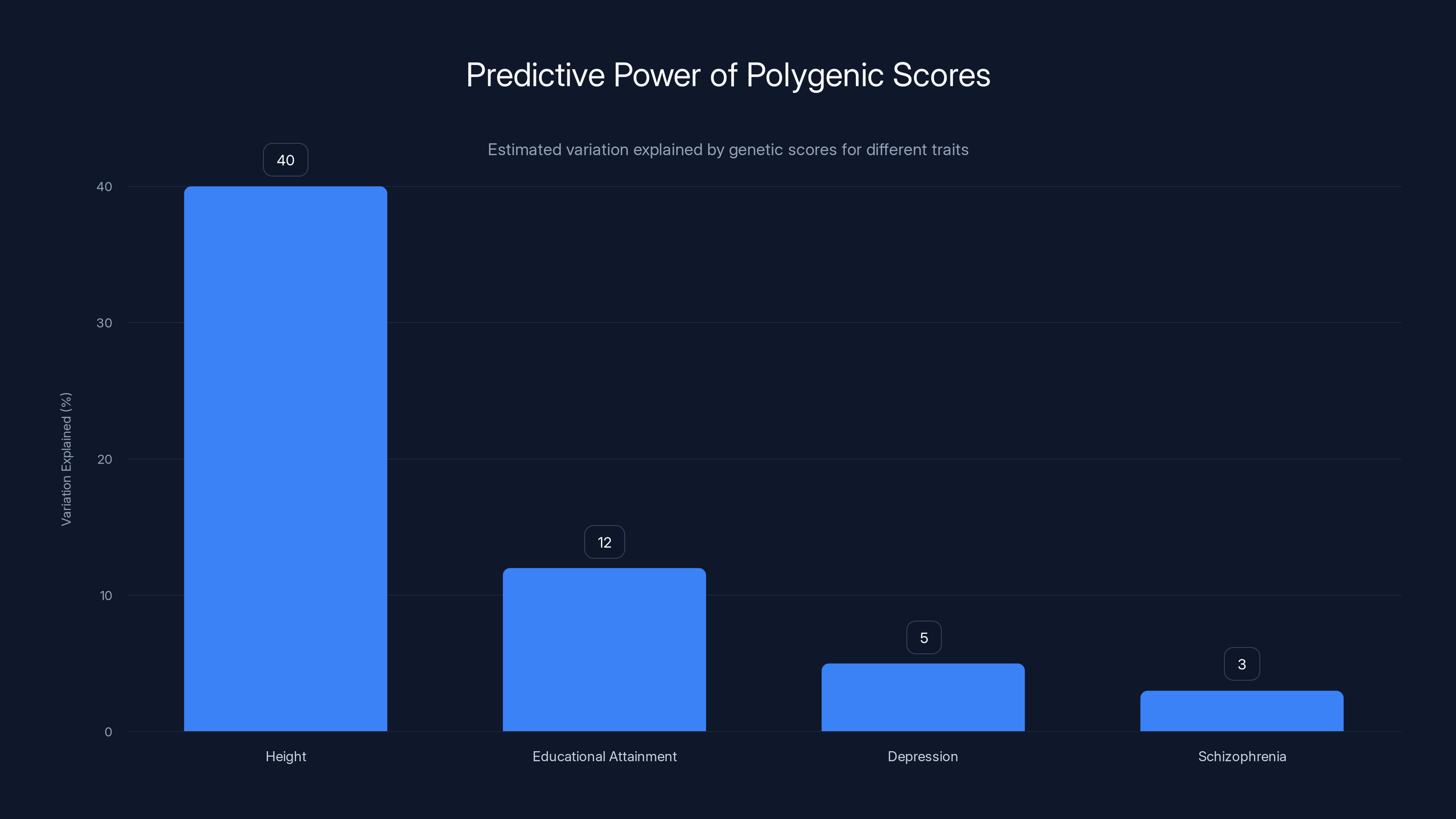

Current polygenic scoring for height achieves about 40% of the theoretical maximum improvement, highlighting the gap between potential and practical outcomes. Estimated data.

The Fundamental Gap Between Hype and Reality

When a genetic testing company tells you that your DNA predisposes you to depression or reduced educational attainment, what they're really telling you is this: in a large population study, people with similar genetic profiles showed slightly elevated rates of these outcomes. That's not nothing. But it's also not a prediction about you specifically. It's population-level statistics applied to an individual.

This distinction matters enormously, and it's where the confusion starts. A diagnostic test tells you whether you have a disease. A genetic test that claims to predict risk tells you something much vaguer: that you're in a statistical distribution where certain outcomes are somewhat more likely than in the general population. The gap between those two things gets lost in marketing materials, consumer expectations, and even in some cases, research papers.

Consider height, which is one of the most heritable traits we know. Height is influenced by thousands of genetic variants, each contributing a tiny effect. Even if you could perfectly read all those variants, you still couldn't predict someone's height with high precision because environmental factors (nutrition, childhood illness, sports participation) matter enormously. The theoretical maximum improvement in height prediction from genetic data gets you to explaining about 80% of variation. In practice? Current polygenic scores for height explain about 40%.

For more complex traits like educational attainment or depression, the picture gets much murkier. These traits are influenced not just by genetics and direct environmental factors, but by social systems, opportunity, discrimination, treatment options, family dynamics, and countless other variables that interact in ways we don't fully understand. A polygenic score for educational attainment isn't really measuring genetic "potential" for learning. It's measuring something that correlates with educational outcomes in the specific population where it was developed, which is mostly white, mostly Western, mostly privileged.

What Actually Are Polygenic Scores?

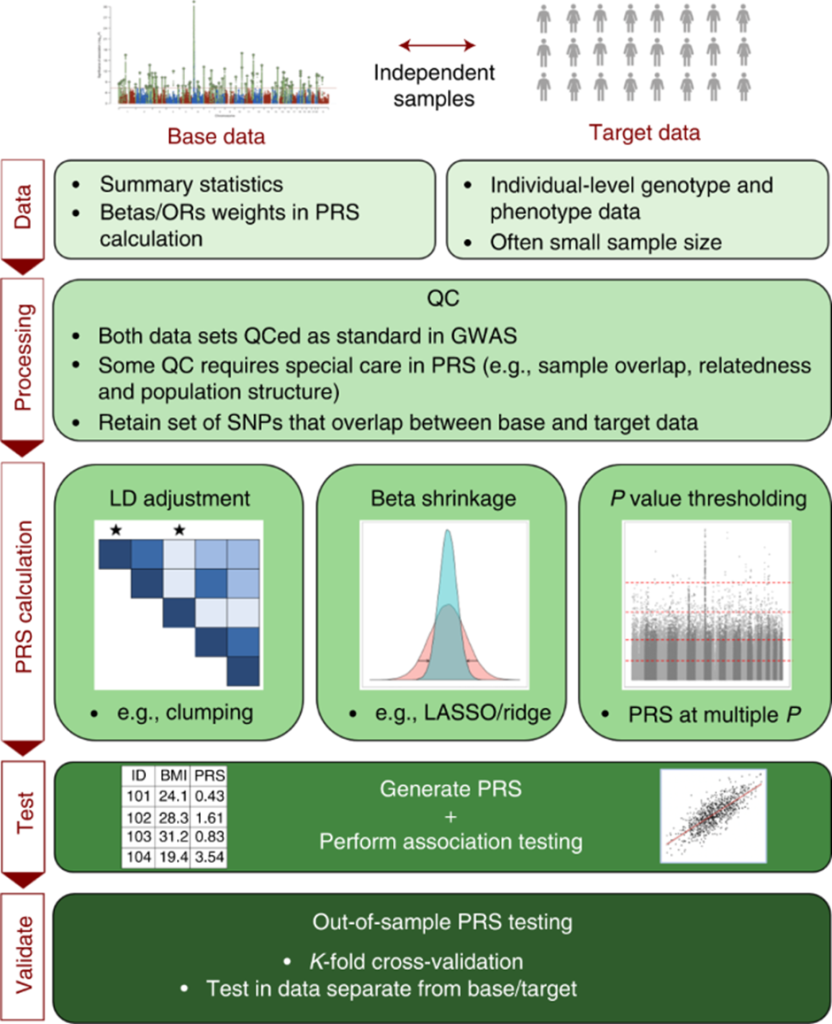

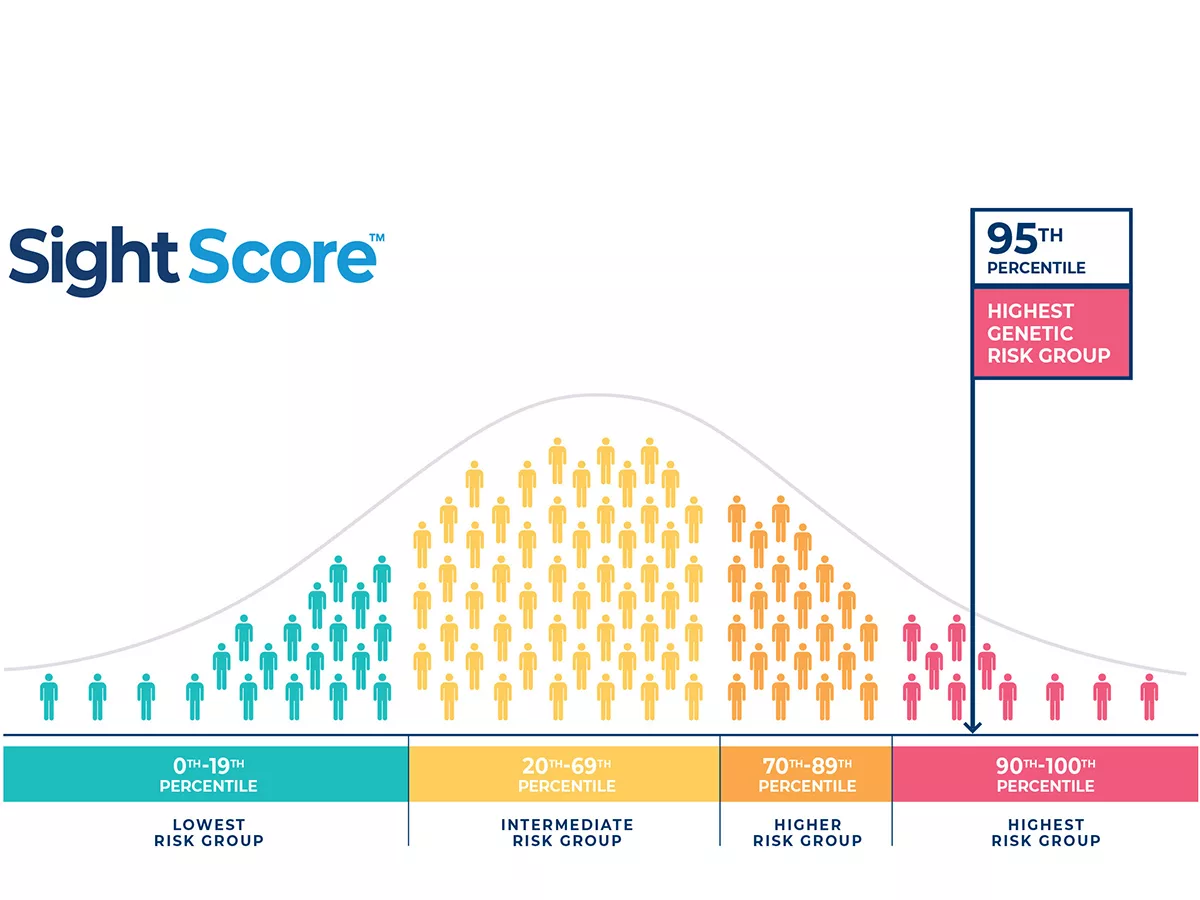

Polygenic scores are mathematical tools that work like this: researchers conduct a genome-wide association study (GWAS) where they compare the genomes of people with a particular outcome (say, type 2 diabetes) to people without that outcome. They identify genetic variants that appear more frequently in the affected group. Then they assign each variant a small weight based on how strongly it associates with the outcome. A polygenic score sums up these weighted variants to produce a single number that estimates genetic predisposition.

The appeal is straightforward. Most human traits and diseases don't follow simple Mendelian inheritance patterns where a single gene determines the outcome. Instead, they involve thousands or even millions of genetic variants, each contributing a tiny effect. Polygenic scores offer a way to aggregate all that information into something actionable.

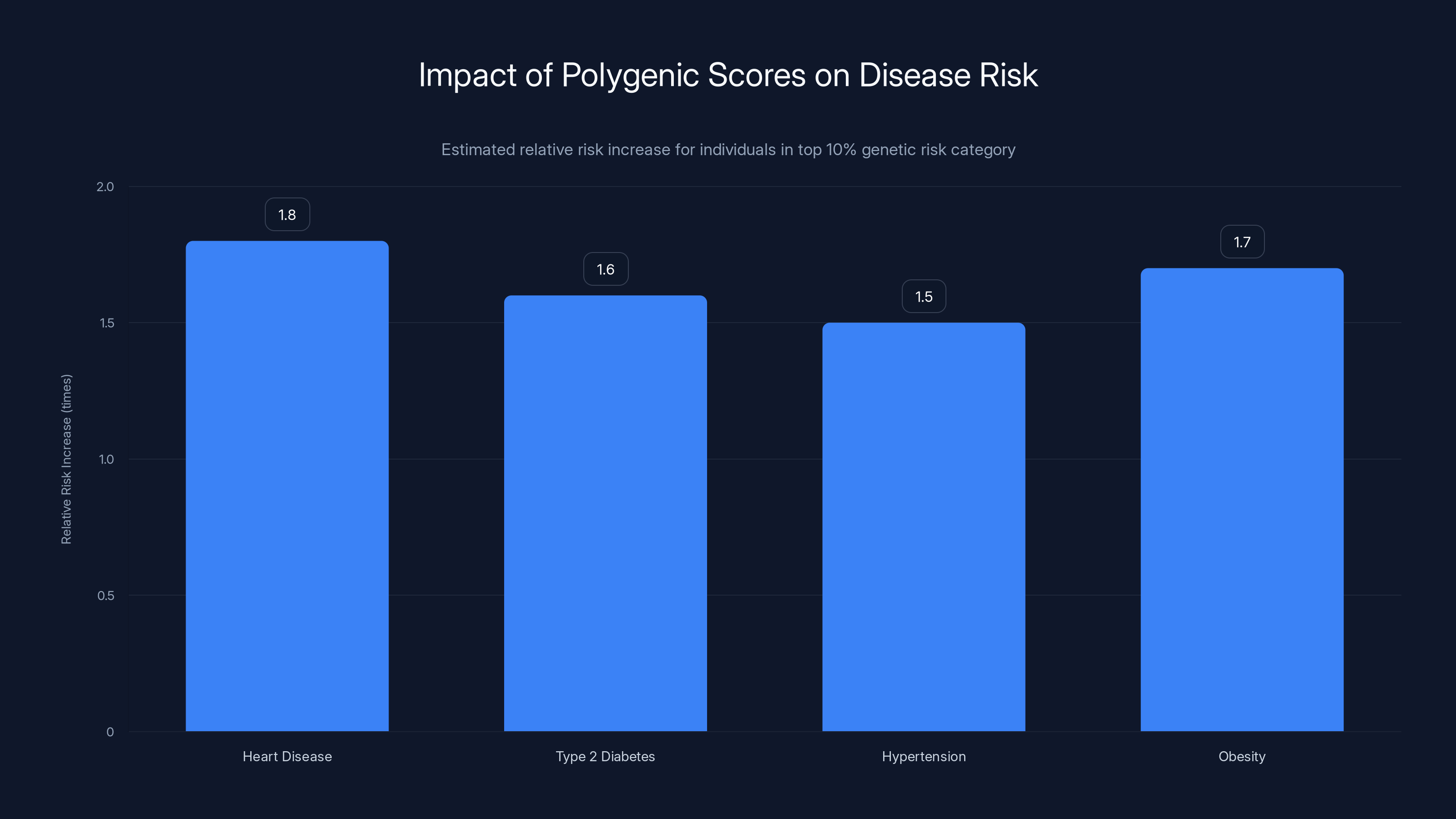

But here's where the science gets complicated. First, the effect sizes are tiny. A polygenic score might show that you're in the top 10% for genetic risk for heart disease, but that might only translate to a relative risk increase of 1.5 to 2.0 times compared to average. That's not nothing from an epidemiological perspective, but it's also not a strong predictor for any individual. Lots of people in the top 10% genetically won't get heart disease. Lots of people in the bottom 10% will.

Second, these scores are constructed in specific populations and don't transfer well. If a polygenic score was developed using only European ancestry participants, it will perform worse when applied to someone of African or Asian ancestry, even if that person has similar disease risks. This isn't because people of different ancestries have fundamentally different genetics in ways that change how traits work. It's because the specific genetic variants that matter in one population might not be the same variants that matter in another population, and linkage disequilibrium (the tendency for certain variants to be inherited together) differs across populations.

Third, polygenic scores fail spectacularly when you try to optimize for multiple traits simultaneously. You can develop a score that predicts height pretty well. You can develop a score that predicts cognitive performance okay. But if you try to create a score that predicts both at high accuracy, the performance of each drops substantially. This matters because embryo selection in the real world involves optimizing for multiple traits at once.

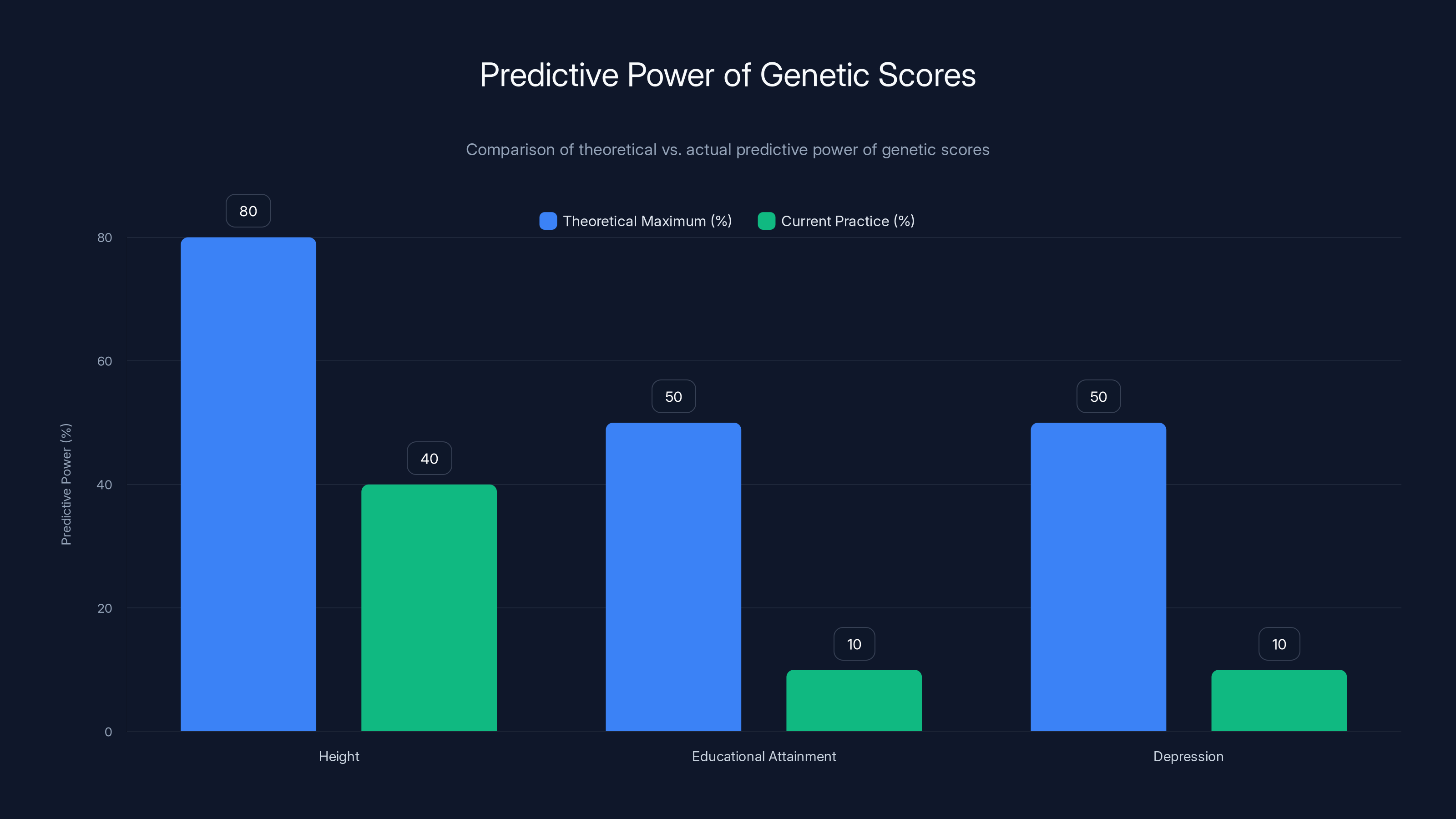

The gap between theoretical and actual predictive power of genetic scores is significant, especially for complex traits like educational attainment and depression. Estimated data.

The Accuracy Problem: Why These Tests Are Less Accurate Than You Think

When you see claims about genetic testing accuracy, you need to understand what's actually being measured. Researchers typically report something called "predictive power" or "R-squared," which essentially tells you how much of the variation in an outcome can be explained by the genetic score. For height, a highly heritable trait, modern polygenic scores explain about 40% of the variation. For educational attainment, they explain about 12%. For depression or schizophrenia, we're talking single-digit percentages.

Why so low? Because environment matters. A lot. You could have all the right genetic variants for high educational attainment and still drop out of high school because your school is underfunded, because your family can't afford tutoring, because you face discrimination, or because you need to work to help support your family. You could have genetic risk factors for depression but have access to good therapy and medication and supportive relationships that prevent symptoms from developing.

But here's something crucial: a 12% explanation of variation sounds low, but it's actually pretty good for complex behavioral traits in the social sciences. The problem is that this creates a false sense of precision. A polygenic score that explains 12% of educational attainment variation will correctly predict that someone in the top 10% genetically will on average have better educational outcomes than someone in the bottom 10%. But the overlap is enormous. There are people in the bottom 10% genetically who achieve more education than people in the top 10%.

Think of it like predicting height from weather patterns. If taller people are slightly more likely to live in certain climates, you could develop a "climate score" for height that explains, say, 2% of variation. It would be a real relationship. But it would also be nearly useless for predicting any individual's height. Polygenic scores have the same problem, just with better effect sizes.

When companies start applying polygenic scores in embryo selection, this accuracy problem gets worse. You're not just selecting for one trait with low predictive power. You're trying to optimize across multiple traits simultaneously, and possibly trying to predict outcomes that depend on environments that don't even exist yet (what will educational opportunities look like in 2040 when your embryo becomes a teenager?).

Two Visions of Genetic Truth

There's a fundamental disagreement in the scientific and bioethical community about what we should do with genetic information, and it's not really a disagreement about the science itself. Two researchers, Sam Trejo (a quantitative sociologist at Princeton) and Daphne Martschenko (a bioethicist at Stanford), spent ten years writing a book together from opposing perspectives, and their disagreement is instructive.

Trejo's position is essentially: more information is better than less. We can't know what benefits might come from basic genetic research. The research is happening anyway, whether we like it or not. So we should try to harness it toward good rather than ill. From this view, developing better polygenic scores, studying the genetic contributions to complex traits, and exploring how to use this information in medicine and elsewhere is fundamentally valuable.

Martschenko's position is: genetic research has almost always been used to justify existing inequalities. We already know how to solve most of the problems we claim genetic research will help with (poverty, mental illness, lack of opportunity). We don't need more genetic research to implement those solutions. And the track record of using genetic information to address social problems is dismal, ranging from eugenics to racial pseudoscience to medical discrimination. Maybe we should focus on actually implementing known solutions rather than generating more data that will probably be misused.

Both are right. And that's the problem. There are legitimate reasons to pursue genetic research, and there are legitimate reasons to be terrified of where it might lead. The issue is that we've structured the system as if only one of them is correct. We've let the research proceed with minimal oversight and minimal consideration of where it might lead. And now we're seeing the consequences.

Martschenko and Trejo identify two major myths that guide how people think about genetics. The first is the "Destiny Myth," originally articulated by Francis Galton in 1869, which falsely separates genetic and environmental effects as if they operate independently. Galton didn't deny that environment matters. He just treated nature and nurture as competing forces rather than as deeply intertwined factors that shape each other constantly. This myth has been used to justify everything from forced sterilization programs to claims that poverty is genetically determined.

The second is the "Race Myth," which claims that human genetic variation divides us into discrete racial groups with biological significance. This is false. Humans show continuous genetic variation. You can cluster people by ancestry using genetic data, but those clusters don't correspond neatly to conventional racial categories. Genetic variation within racial groups is greater than variation between them. And yet, this myth persists and gets reinforced every time someone uses genetic data to claim that racial differences in health outcomes or socioeconomic status are caused by genetics rather than by systems of racism and inequality.

The Eugenics Shadow: Why History Matters

You can't talk seriously about genetic testing without talking about eugenics. Because genetic ideas have been weaponized before, repeatedly, and with catastrophic consequences. Understanding this history isn't about paranoia or assuming everyone in genetics is a bad actor. It's about understanding that good intentions aren't enough, that scientific facts can be interpreted through ideological filters, and that once genetic data exists, it can be used in ways we didn't anticipate.

Francis Galton's "heredity" concept became the foundation for eugenics movements in the early 1900s. The idea was simple: if traits are inherited, then improving human genetics means selectively breeding people with "good" traits and preventing people with "bad" traits from reproducing. In the US, this translated into forced sterilization programs targeting poor people, disabled people, people of color, and anyone deemed genetically "unfit." Over 60,000 people were forcibly sterilized. In Sweden, it was tens of thousands. In Japan and Canada, similar programs existed.

Then came Nazi Germany, where eugenics ideology was adopted wholesale and combined with racist pseudoscience to justify genocide. Millions of people were killed based on the false belief that Jews, Roma, people with disabilities, and others were genetically inferior. After the Holocaust, eugenics lost respectability in mainstream science. But the underlying ideas—that human worth is determined by genetics, that some people are genetically superior to others, that societies should optimize human genetics—never fully died.

They just became more sophisticated. Instead of crude classifications, we have polygenic scores. Instead of "you're not allowed to reproduce," we have "here's the genetic risk for your embryos." Instead of state-mandated programs, we have individual consumer choice. But the fundamental logic—that genetics determines human worth, that we can and should make reproductive choices based on genetic prediction, that inequality is partly or mostly genetically determined—persists.

Polygenic scores can indicate a relative risk increase of 1.5 to 2.0 times for individuals in the top 10% genetic risk category for various diseases. Estimated data.

The Regulatory Vacuum: Why Companies Can Sell These Tests With Almost No Oversight

Here's where things get genuinely alarming: in most countries, including the United States, companies can develop and sell genetic tests with minimal regulatory oversight. The FDA doesn't review every genetic test before it hits the market. Most genetic tests don't require clinical validation before being offered to consumers. And the standards for what counts as "validated" vary wildly depending on who's doing the validating.

Gene editing faces intense scrutiny. Scientists who want to edit human embryos have to navigate international agreements, ethics reviews, and extreme pushback. But polygenic scoring, which arguably poses different but equally serious risks, operates in regulatory shadows. A company called Genomic Prediction started offering polygenic scores for embryo selection in 2020, scoring for conditions like diabetes, skin cancer, high blood pressure, and intellectual disability. They've since stopped advertising the intellectual disability score specifically "because it's too controversial," not because the science is unreliable or because the predictive power is too weak, but purely because of social pushback.

This is backwards. If a test is too scientifically weak to make reliable predictions, that should disqualify it immediately. But instead, companies are self-regulating based on how much controversy they face, which is a terrible system. It means that companies will keep pushing until society explicitly objects, and by then, the technology might already be embedded in clinical practice.

The theoretical maximum improvement in height prediction from polygenic scoring would be about 2.5 inches. That's assuming perfect genetic data, perfect understanding of all genetic contributions, and no environmental effects. In practice? Current scores for height achieve maybe 40% of that theoretical maximum. And that's for height, one of the most heritable, best-understood traits. For intellectual disability, the science is far murkier. The trait is heterogeneous (many different causes). Environmental interventions can substantially alter outcomes. And the ethical implications of screening for it in embryos are enormous.

Yet companies have been marketing these tests to prospective parents using IVF, with minimal regulation, minimal transparency about limitations, and minimal consideration of what selecting against these traits means for people currently living with these conditions.

Ancestry Bias: The Hidden Accuracy Problem

Here's a crucial fact that doesn't get nearly enough attention: almost all genetic studies have been conducted primarily or exclusively on people of European ancestry. This creates a systematic bias in every polygenic score, every genetic association finding, and every genetic test marketed to the general public.

When you develop a polygenic score using 95% European ancestry participants, you're identifying genetic variants that associate with a trait in that specific population, under that specific set of environmental conditions. When you then apply that score to someone of African, Asian, or other non-European ancestry, you're assuming that the same genetic variants drive the same trait in that population. Sometimes that's true. Often it's not, or not entirely.

This isn't a minor accuracy glitch. It's a systematic bias that means polygenic scores are substantially less predictive for non-European ancestry groups. Studies have documented this repeatedly. A polygenic score for heart disease developed in Europeans might explain 15% of variation in a European sample but only 8% in an African ancestry sample. The difference isn't huge in absolute terms, but it's meaningful. It means the test is less useful. It means the risk stratification is less accurate. And it means that clinical recommendations based on these scores might not apply equally to people of different ancestries.

But here's where it gets really problematic: if these tests get integrated into clinical practice before the ancestry bias is fully understood and addressed, they could actually worsen existing health disparities. Imagine a polygenic score that's supposed to identify people at high risk for a particular disease. If the score is less accurate for Black patients than white patients, doctors might either over-screen white patients (unnecessary interventions, anxiety) or under-screen Black patients (missing preventable disease). Or they might distrust the score for Black patients and revert to other, equally biased ways of assessing risk.

The solution, obviously, is to conduct genetic studies in diverse populations. But that's not happening fast enough. Most genetic research funding still goes to studying Europeans. Most published GWAS studies still use mostly European samples. The institutions that do conduct diverse genetic research sometimes hit additional obstacles, including distrust from communities that have legitimate historical reasons to be wary of genetic research (see: Henrietta Lacks, the Tuskegee experiments, ongoing medical racism).

So we have a system that's developing genetic tests faster than it's addressing the diversity problem, which means that the tests being developed and deployed right now are probably being used in ways that aren't appropriate for large swaths of the global population.

Embryo Selection and the Specter of Eugenics

When a couple uses in vitro fertilization (IVF), they can already screen embryos for genetic diseases. Traditional PGT-M (preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic conditions) targets single-gene disorders like cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease. Nobody argues against this technology much because we're talking about preventing serious, life-altering disease.

But now companies are offering PGT-P (polygenic testing), which uses polygenic scores to screen embryos for traits like height, intelligence, educational attainment, or disease risk. This is where things get genuinely troubling because you're using weak probabilistic predictions to make definitive reproductive choices.

Here's the logic: if a polygenic score for intelligence explains 12% of variation in educational outcomes, and you select embryos that score higher on that metric, you're selecting for something. The children born from those embryos will on average have slightly better genetic predisposition for educational outcomes than they would have if you'd selected randomly. But you're also potentially doing several things: you're reducing genetic diversity for traits you've decided are important, you're making it more likely that specific genetic variants associated with these traits become more common, and you're essentially saying that these traits are worth selectively breeding for.

Now, individual couples making this choice doesn't sound so bad. But extrapolate it. If enough couples start using PGT-P to select for higher intelligence, or for height, or for reduced disease risk, the genetic composition of the population starts to shift. You get directional selection on traits that previously had been subject to natural variation. Over generations, this could substantially reshape human genetic diversity.

The counterargument is that this is just modern medicine. Parents already make choices to optimize their children's traits (private schools, enrichment activities, orthodontia). Why not use genetic information too? The answer is that genetic information is different. It's inheritable, population-level effects compound, and history shows that genetic selection technologies have been used to enforce conformity and justify discrimination.

Moreover, the traits being selected for are heavily influenced by environment and social context. Intelligence is influenced by thousands of genes but also by education quality, nutrition, socioeconomic opportunity, and discrimination. Height is influenced by nutrition and health status. Disease risk is heavily influenced by lifestyle and healthcare access. Selecting embryos for these traits based on polygenic scores assumes that the genetic component is the important part, which is scientifically dubious and socially dangerous.

Polygenic scores have moderate predictive power for height but are much less predictive for complex traits like intelligence and mental health. Estimated data.

The Science Education Problem

Daphne Martschenko and Sam Trejo both agree on at least one thing: American science education is abysmal and needs immediate improvement. Most people's knowledge of genetics is stuck at what they learned in high school biology. They understand dominant and recessive alleles, Punnett squares, and maybe a little bit about DNA structure. But modern genetics is nothing like that.

When you're talking about polygenic traits, you're not dealing with dominant and recessive alleles producing predictable phenotypes. You're dealing with complex interactions between thousands of variants, most with tiny effect sizes, in the context of massive environmental influences that we don't fully understand. A trait like height or intelligence or educational attainment isn't determined by a handful of genes. It's influenced by evolutionary history, developmental timing, epigenetic regulation, gene-environment interactions, cultural context, social systems, and pure chance.

But the mental models people bring to genetic testing are still shaped by high school biology. People think if a gene causes height, then genetic information should tell you how tall you'll be. People think if a gene contributes to intelligence, then genetic information should tell you how smart you'll be. Companies marketing genetic tests leverage this intuitive but incorrect understanding. They present polygenic scores as if they were strong predictors, when in reality they're weak signals in a vastly more complex system.

Improving science education doesn't solve this problem entirely, because even educated people struggle with probabilistic reasoning and complex systems. But it's necessary. People need to understand that correlation isn't causation, that population-level statistics don't translate to individual predictions, that environmental factors often matter more than genetic ones, and that human traits are rarely determined by neat genetic mechanisms.

This is partly a communication problem, partly an education problem, and partly a profit motive problem. Companies have incentives to oversimplify, to present weak evidence as strong, to emphasize what's genetically determined and downplay what's environmental. School systems have incentives to teach what's easy to test rather than what's most important. And people have cognitive biases that make them drawn to simple genetic explanations rather than systemic ones.

Complex Traits, Genetic Determinism, and the Illusion of Simplicity

Let's talk specifically about some of the traits that genetic testing companies claim to predict, because the gap between what these tests claim and what they can actually deliver is enormous.

Educational Attainment: Companies offer polygenic scores for "educational intelligence" or "genetic predisposition for educational attainment." What they're really measuring is something that correlates with how much education people in a genetic study obtained. Educational attainment is influenced by: quality of schools, family income, parental education level, cultural attitudes toward school, discrimination, learning disabilities, mental health, nutrition, sleep, whether you need to work to support your family, peer networks, geographic location, and dozens of other environmental factors. Some of those factors have nothing to do with genetics. Many of them are heavily influenced by social systems and inequality.

A polygenic score can identify genetic variants that statistically associate with higher education in a study population. But causal interpretation is dangerous. The genetic variants might not be directly causing education to happen. They might be tagging for socioeconomic status, which inherited both genetically and through family environment. They might correlate with traits like "ability to follow instructions" or "willingness to delay gratification," which are culturally valued in Western schools but aren't universal measures of intelligence. The polygenic score isn't measuring natural intelligence. It's measuring something that correlates with education in a specific cultural and socioeconomic context.

Mental Health Conditions: Companies offer polygenic scores for depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disorders. The scientific case for using these in clinical practice is weak. First, because these are heterogeneous conditions with multiple causes, so any genetic score will only explain a small fraction of variation. Second, because environmental factors like trauma, stress, and social support matter enormously in determining whether someone develops a condition. Third, because these are complex conditions where genetics might influence vulnerability, but whether someone actually develops the condition depends on life experience, access to treatment, and social context.

A polygenic score for depression might tell you that you're in the top 20% genetically for depression risk. But that doesn't mean you'll develop depression. It means you're at slightly elevated risk compared to average. Environmental interventions, therapy, exercise, social connection, economic security, and treatment access might make the difference between being at risk and actually becoming depressed.

Height and Physical Traits: Height is the polygenic trait scientists understand best because it's highly heritable, easy to measure, and not heavily influenced by social context (unless you count nutrition, healthcare, and environmental pollutants, which affect growth). Even for height, a polygenic score explains only about 40% of variation. The rest is environment. Want to predict someone's height? Knowing their parents' heights and their nutrition during development is more informative than a polygenic score.

Disease Risk: Companies offer polygenic scores for heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and other diseases. Again, genetic predisposition is just one factor. Disease risk depends on lifestyle, healthcare access, environmental exposures, healthcare treatment, medication adherence, and dozens of other factors. A polygenic score might identify people at slightly elevated genetic risk. But telling someone they're at high genetic risk without also assessing their modifiable risk factors, their access to preventive medicine, and their healthcare resources is incomplete at best, misleading at worst.

The Ancestry Question: What Is "Genetic Risk" Really Measuring?

Here's something that rarely gets discussed: when a polygenic score correlates with disease risk, what exactly is it measuring? Sometimes it's measuring actual genetic predisposition to disease. But sometimes it's measuring genetic ancestry, and genetic ancestry correlates with lifestyle, healthcare access, socioeconomic status, discrimination, diet, and a thousand other environmental factors that predict disease.

This becomes a serious problem when you're using genetic data to make clinical decisions. If you give someone a polygenic score for heart disease and tell them they're at high risk, but you don't assess their actual modifiable risk factors, you might cause harm. You might increase anxiety. You might cause them to request unnecessary medications or procedures. You might anchor them on a genetic narrative that leads them to believe their risk is inevitable rather than modifiable.

Moreover, if a polygenic score developed in European ancestry participants is applied to someone of African ancestry, and it's less accurate, you might systematically mis-stratify risk. Studies have shown that genetic risk scores for coronary artery disease developed in European populations don't predict risk as well in African ancestry populations. That's not because African ancestry people have fundamentally different genetics. It's because the specific genetic variants that matter, the environmental factors that combine with those variants, the healthcare systems, and other factors are different.

But if you don't account for ancestry-specific accuracy, you might systematically under-risk-stratify Black patients, who already face barriers to healthcare and suffer worse outcomes from cardiovascular disease. You could end up using a genetic test in a way that worsens health disparities.

This is why the ancestry bias in genetic studies is so consequential. It's not just an academic problem. It's a problem with real-world clinical implications and real-world consequences for people from underrepresented populations.

Current regulation levels for genetic testing are significantly lower than those proposed, especially for direct-to-consumer tests and embryo selection. Estimated data based on narrative context.

Individual Choice, Population Effects, and The Ethics of Genetic Testing

Here's the crux of the ethical problem: genetic decisions look like individual choices, but they have population-level effects. If one couple uses PGT-P to select for higher intelligence, that's their individual choice, exercised within their reproductive autonomy. But if thousands or millions of couples do this, you start to see population-level shifts in genetic frequencies.

Over many generations, this could substantially reshape human genetic diversity for traits that have previously been subject to natural variation. That has unpredictable consequences. You might reduce genetic diversity for intelligence or height, which could make humans more vulnerable to new environmental challenges. You might inadvertently select for alleles that have negative pleiotropic effects (where a genetic variant is beneficial for one trait but harmful for another). You might create new forms of inequality where enhanced traits become markers of socioeconomic status and reproductive success.

Moreover, there's an assumption in all of this that "better" traits are obvious and universal. But they're not. Height and intelligence are valued in modern Western societies, but in different environments, different traits might be advantageous. And traits that seem obviously good (intelligence, disease resistance) might have tradeoffs. The genetic variants associated with higher intelligence in one study might be associated with increased anxiety or reduced fertility in other studies. We don't understand the full network of effects.

Then there's the question of what happens to people who don't get selected for, or who don't have access to selection. If genetic selection for intelligence becomes common among the wealthy, what does that do to social inequality? Does it create a genetic basis for class differences? Does it reduce genetic diversity in ways that make everyone more vulnerable? Does it stigmatize people who have lower polygenic scores?

These aren't paranoid hypotheticals. These are predictable consequences of widespread genetic selection based on imperfect predictions of complex traits. We need to think about them before the technology is entrenched in clinical practice.

Regulation: The Crucial Missing Piece

Both Trejo and Martschenko agree on this: we need much more aggressive regulation of genetic testing, especially for applications like embryo selection. Currently, the regulatory framework is a patchwork of FDA oversight for some tests, state-level regulations for genetic counseling, and almost no oversight for companies offering direct-to-consumer genetic testing or embryo selection services.

Why is this a problem? Because it allows companies to move into new territory before we've established whether the new territory is scientifically sound or ethically appropriate. Genomic Prediction could offer polygenic screening for intellectual disability because it was technically possible and legally permissible, not because the science supported it or because we had consensus that it was ethical.

The regulatory approach to gene editing (strict, multi-layered, international) is actually more appropriate than the current approach to polygenic scoring (almost nonexistent). You don't edit genes in human embryos without extensive review. But you can screen embryos using weak probabilistic predictions with minimal oversight.

What better regulation might look like:

-

Validation requirements: Tests should require validation in the populations they'll be used in, not just in the population where they were developed. A polygenic score developed in Europeans should be validated in African ancestry populations before being marketed to Black patients.

-

Clinical utility standards: Tests should demonstrate not just that they correlate with outcomes, but that having test results actually improves outcomes. Does knowing your polygenic score for depression lead to better treatment and better outcomes? That needs to be demonstrated, not assumed.

-

Ancestry-specific performance: When accuracy differs by ancestry, that should be explicitly disclosed and acknowledged. Doctors need to know that a test is more accurate for their white patients than their Black patients.

-

Transparency about limitations: Marketing materials should be required to include predictive power (how much variation explains), false positive/false negative rates, and what the score doesn't capture.

-

Oversight of reproductive applications: Embryo selection using polygenic scores is a novel application with population-level effects. It should require ethics review and oversight, similar to what gene editing requires.

-

Data sharing requirements: Research using human genetic data should require researchers to make findings available in diverse populations or to share data with researchers working in underrepresented populations.

None of this is radical. These are standard research and clinical practice principles applied to genetic testing. But applying them would require the genetic testing industry to slow down, to validate more carefully, to acknowledge limitations, and to consider broader ethical implications. Companies have incentives not to do any of this.

The Diversity Problem: Why Current Genetic Research Isn't Representative

Approximately 96% of genetic association study participants are of European descent. This is despite European ancestry people being only about 15% of the global population. Why is this such a massive gap?

Partly, it's historical. Genetic research has been concentrated in wealthy, Western countries where research infrastructure and funding exist. Partly, it's practical. Studying genetics requires access to large numbers of participants with detailed health records, which is easier in wealthy countries. Partly, it's cultural and historical. Communities of color have legitimate reasons to distrust genetic research, given the history of eugenics, medical racism, unethical research, and exploitation of genetic data.

But the consequence is that our genetic knowledge is systematically biased toward European ancestry people. Every polygenic score is calibrated for Europeans. Every genetic association finding is primarily based on European data. Every genetic test is less accurate for non-Europeans. And this gets baked into clinical practice, further disadvantaging people who are already underserved by medicine.

Improving this requires funding diverse genetic research, requiring validation in diverse populations as a condition of publishing, reducing barriers for communities to participate in research (including addressing historical injustices and ensuring equitable benefit-sharing), and prioritizing diversity in research participants.

It also requires being honest about why diversity is lacking. It's not because non-European populations are less interested in participating. It's because research institutions haven't prioritized reaching those populations, haven't built trust, haven't addressed historical exploitation, and haven't made participation convenient or beneficial for communities.

Polygenic scores explain 40% of height variation but only 12% for educational attainment and even less for mental health traits. Estimated data.

What Individual Consumers Should Actually Know

If you're considering genetic testing, whether for health information, ancestry, or reproductive decisions, here's what actually matters:

For disease risk scores: Understand that a genetic risk score tells you about population-level probability, not individual destiny. A high score doesn't mean you'll develop the disease. A low score doesn't mean you're safe. Genetic risk should be integrated with lifestyle factors, family history, and actual clinical assessment. A genetic score for heart disease risk is less useful than knowing your actual cholesterol levels, blood pressure, weight, fitness, diet, and family history.

For ancestry and genealogy testing: Understand that you're getting an estimate of ancestry based on comparison to reference populations. The precision is lower than marketing materials suggest. The categories (European, Asian, African) are human-imposed categories, not biological essences. Your genetic ancestry might not match your cultural or self-identified ancestry, and that's fine. Both matter.

For embryo selection: Understand that you're making reproductive choices based on probabilistic genetic predictions of complex traits heavily influenced by environment. You're selecting for traits that might have tradeoffs, using science that's still unsettled, with population-level implications you can't fully predict. This is legitimate to consider, but it's not simple or obvious.

For mental health: Be especially cautious about genetic risk scores for psychiatric conditions. These conditions are highly responsive to environmental interventions, highly influenced by trauma and social factors, and heavily stigmatized. A genetic score might increase anxiety or fatalism. It might lead to unnecessary medication. Environmental changes (therapy, social support, reducing stress) might be more impactful than knowing your genetic risk.

For all testing: Ask what you'll do with the information. If knowing your result doesn't change your behavior or medical care, is the test worth taking? Will it increase anxiety without providing actionable information? Is it validated in people like you, or only in Europeans?

And be skeptical of any test that claims to predict your future based on genetics. Human futures are shaped by genetic endowments, yes, but also by choices, chance, opportunity, social systems, and environmental factors we can't predict. No genetic test can really tell you who you'll become.

The Path Forward: How to Do Better

We don't need to ban genetic testing. Genetic research has real value. But we need to do it better. That means:

Slow down, check your work: Validate carefully. Test in diverse populations. Publish negative results. Don't move technology into clinical practice before understanding its limitations and its potential for harm.

Invest in diverse research: Fund genetic research in non-European populations. Make diversity in research participants a requirement for publication. Address historical injustices that make communities wary of participating.

Regulate appropriately: Apply oversight to genetic testing similar to what's applied to gene editing. Require disclosure of limitations. Require clinical utility, not just correlation. Oversee reproductive applications.

Improve education: Teach people how to evaluate probabilistic information, how to think about gene-environment interactions, and how genetic data has been misused historically. Make science education about thinking clearly, not just learning facts.

Be honest about what we don't know: We don't fully understand complex traits. We don't understand all the ways genetic variants interact with each other and with environment. We don't fully understand what happens if we start selecting for specific traits across a population. Rather than hiding this uncertainty, we should be transparent about it.

Center equity: Genetic technologies can easily widen existing inequalities or create new ones. They should be designed and deployed with equity in mind. That means considering who benefits, who might be harmed, and whether the technology increases or decreases inequality.

This is hard work. It's slower than what companies want to do. It requires regulation that limits profit potential. It requires humility about what science knows. But the alternative is rushing into genetic technology without understanding the consequences, which is basically what we're doing now.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Analyzing Genetic Data

One development that could help or hurt the situation is the increasing application of artificial intelligence and machine learning to genetic data. On one hand, AI models could identify patterns in genetic data that humans miss, potentially improving prediction. On the other hand, AI models trained on biased data (mostly European participants) will amplify those biases. And AI creates a black-box problem: even if a machine learning model predicts outcomes accurately, understanding why it makes those predictions and whether it's making them for the right reasons becomes harder.

There's also the possibility that AI-driven genetic prediction tools get deployed in ways nobody fully understands. A machine learning model might identify genetic patterns that correlate with outcomes for reasons that have nothing to do with biological causation. It might identify patterns that are artifacts of the training data or the populations studied. But if the model makes accurate predictions, it might get used clinically anyway.

This is where regulation becomes crucial. Machine learning models for genetic prediction should require the same validation and oversight as traditional genetic tests. They should be tested for ancestry-specific performance. They should be required to explain their predictions in interpretable terms. And clinical use should require evidence that using the model improves outcomes compared to standard care.

Right now, that's not happening. AI companies and genetic testing companies are rushing to apply machine learning to genetic data without sufficient validation or oversight. The same regulatory vacuum that allows polygenic testing applies to AI-driven genetic analysis.

Looking Ahead: What Might Genetic Testing Be Like in Five Years?

If current trends continue without intervention, here's what we might see in five years:

- Polygenic testing becomes more common in prenatal settings, though still concentrated among affluent populations that can afford IVF and genetic screening.

- Machine learning models for genetic prediction proliferate, with variable validation and minimal oversight.

- Ancestry bias remains a significant problem because the massive investment needed to collect and study genetic data in diverse populations hasn't materialized.

- Health insurers start using polygenic scores in risk stratification, creating potential for discrimination or inappropriate coverage decisions.

- Direct-to-consumer genetic testing expands to include more behavioral and complex trait predictions.

- Genetic counseling becomes more important but potentially less available to people who most need it.

If we intervene more proactively, we might see:

- Stronger regulatory standards requiring validation in diverse populations before clinical use.

- Significant investment in genetic research with non-European participants.

- More nuanced understanding of gene-environment interactions, leading to more humble predictions.

- Clinical guidelines on appropriate use of genetic testing that emphasize clinical utility over correlation.

- Oversight of embryo selection applications with ethics review processes.

- Better science education allowing consumers to evaluate genetic testing claims critically.

The difference between those two futures is substantial. The choice is still ours to make, but it gets narrower as technology becomes embedded in practice.

FAQ

What exactly is a polygenic score?

A polygenic score is a mathematical tool that sums the effects of hundreds of thousands of genetic variants to estimate genetic predisposition to a trait or disease. It works by identifying genetic variants that statistically associate with a trait in research studies, assigning each variant a weight, and adding them together to produce a score. The score tells you whether you have more or fewer genetic risk factors for a trait compared to average, but it doesn't predict whether you'll actually develop that trait, because environmental factors matter enormously.

How accurate are commercial genetic tests?

Accuracy depends on the trait, the population the test was developed in, and what you mean by accuracy. For height (highly heritable and well-studied), polygenic scores explain about 40% of variation, meaning they're moderately predictive at a population level but weak for individuals. For complex traits like intelligence or mental health, predictive power is much lower, often single-digit percentages. These tests are also significantly less accurate for people of non-European descent because genetic research has been concentrated on Europeans.

Should I get genetic testing for disease risk?

That depends on whether knowing your genetic risk would change your health decisions and whether the disease is one where genetic risk is actionable. For something like breast cancer where there are validated high-risk genes (BRCA1/BRCA2) and proven screening protocols, genetic testing can be valuable. For polygenic risk scores predicting complex diseases, the value is less clear. You might benefit more from assessing your actual modifiable risk factors and talking to your doctor about prevention strategies that are proven to work.

Is it ethical to use genetic testing to select embryos?

This is genuinely complicated. Selecting embryos to prevent serious genetic diseases seems reasonable to most people. Selecting embryos based on weak probabilistic predictions of complex traits influenced by environment is much more ethically fraught. It assumes that genetic predisposition is destiny, that specific traits are obviously worth selecting for, and that the population-level effects of widespread genetic selection are acceptable. These are big assumptions without clear answers.

Why are genetic tests less accurate for people of color?

Genetic studies have been conducted almost exclusively on people of European descent, so genetic variants that matter were identified in European populations. Those same variants might not be as important in other populations, or different variants might be important in other populations. Polygenic scores developed in Europeans perform worse when applied to non-Europeans, not because of biological differences, but because the genetic architecture of traits differs across populations. This creates systematic inaccuracy and potential for harm if these tests get used clinically without acknowledging ancestry-specific performance.

What's the difference between genetic research and eugenics?

Genetic research itself is neutral technology. Eugenics is the application of genetic ideas toward selective breeding or elimination of specific groups. The risk isn't genetic research, but genetic research being used to justify discrimination, selection against specific groups or traits, or claims that human inequality is genetically determined. Historical eugenics programs in the US, Sweden, Japan, and Nazi Germany show that genetic ideas can easily become tools for enforcing conformity and justifying genocide. This history matters when thinking about applications like embryo selection.

How can I evaluate claims about genetic testing?

Ask these questions: How much of the variation in the trait does this genetic test actually explain (what's the R-squared or predictive power)? Was it validated in people like me, or only in Europeans? What would I do with this information? Does knowing my genetic risk change what my doctor would recommend, or does it just increase anxiety? Is the test scientifically validated or marketing hype? If something sounds too good to be true ("discover your true potential" or "know your real future"), it probably is.

Conclusion: Science in Service of People, Not Ideology

We're in a strange moment with genetic technology. We have more powerful tools than ever before for reading and understanding human genetics, but our wisdom about how to use those tools hasn't caught up. We're deploying tests before we fully understand their limitations. We're making reproductive choices based on probabilistic predictions of complex traits. We're allowing companies to market genetic information with minimal oversight. And we're doing all of this without adequately addressing the history of how genetic ideas have been weaponized or the ways that genetic technologies can widen inequality.

The solution isn't to ban genetic research or genetic testing. That's not realistic and would forfeit real benefits. The solution is to slow down, to validate carefully, to acknowledge limitations, to invest in diverse research, to regulate appropriately, and to keep asking the hard questions about what we're doing and why.

It's notable that two researchers with fundamentally different views on genetic testing (Trejo believing in the value of genetic information, Martschenko concerned about misuse) spent ten years collaborating and still managed to have a genuine disagreement. That disagreement reflects something real: there are legitimate tensions in how we think about genetic technology. We genuinely do want genetic research to happen so we can understand ourselves better and potentially develop new treatments. We also have good reasons to be worried about where genetic technology might lead, given historical precedent.

Those tensions don't have easy resolutions. But pretending they don't exist, which is what we're doing by allowing genetic testing to proceed with minimal oversight, is a mistake. The tests are here. They're being used. People are making decisions based on them. We still have the opportunity to shape how this plays out, but that opportunity is closing. The time to think carefully about genetic testing was a decade ago. The second-best time is now.

Genetic science should be in service of human flourishing, human dignity, and human equality. It can be. But only if we're willing to slow down, to be honest about limitations, to address the ways that power and inequality shape genetic research, and to subordinate profit motives to human welfare. That's not guaranteed to happen, which is why science education, regulation, and public engagement with these issues matter so much.

Key Takeaways

- Polygenic scores predict population-level risks, not individual destinies, and explain only 12-40% of variation in complex traits depending on the trait

- Genetic research is systematically skewed toward European ancestry participants (96%), making all predictions significantly less accurate for other populations

- Companies are marketing embryo selection based on polygenic scores for intelligence and other complex traits despite weak scientific evidence and serious ethical concerns

- Gene editing faces strict regulatory oversight while polygenic testing operates with almost no regulation, creating a dangerous regulatory gap

- Genetic ideas have repeatedly been weaponized throughout history (eugenics, forced sterilization, racial pseudoscience), justifying caution about modern applications

Related Articles

- Meta Teen Privacy Crisis: Why Senators Are Demanding Answers [2025]

- HHS AI Tool for Vaccine Injury Claims: What Experts Warn [2025]

- Prediction Markets Like Kalshi: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- Viome Full Body Intelligence Test Review: Worth It or Waste of Money? [2025]

- Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What We Know [2025]

- Trump Administration Relaxes Nuclear Safety Rules: What It Means for Energy [2025]

![Commercial Genetic Testing: Understanding the Risks and Reality [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/commercial-genetic-testing-understanding-the-risks-and-reali/image-1-1771677387659.jpg)