Bezos vs Musk: The Race Back to the Moon [2025]

There's something almost poetic about a billionaire posting a grayscale photo of a turtle on social media to taunt a rival. But when Jeff Bezos did exactly that in February 2026, it wasn't random—it was a calculated jab wrapped in ancient mythology and modern space ambitions.

The turtle reference comes straight from Aesop's Fables. In "The Tortoise and the Hare," the slow, steady tortoise defeats the overconfident hare through patience and determination. Blue Origin, Bezos' private space company, has featured two turtles on its coat of arms since the beginning. It's a deliberate choice that signals the company's philosophy: methodical progress beats flashy promises.

Musk, for his part, had just announced something seismic. SpaceX was pivoting its primary focus from Mars—the long-stated holy grail of Musk's spacefaring dreams—to the Moon as a near-term destination. This wasn't a minor adjustment. For nearly two decades, Musk had publicly championed establishing a multi-planetary civilization on Mars. Mars represented the ultimate frontier, the planet where humanity would truly become a spacefaring species. The sudden shift caught the entire space community off guard.

But here's where Bezos' turtle post becomes significant. Blue Origin, the company that has only launched to orbit twice as of early 2026, is betting it can beat SpaceX to land humans on the Moon. Not just beat it—actually arrive first. This sounds absurd on its surface. SpaceX has over 600 successful orbital launches. The company's Starship represents perhaps the most ambitious rocket ever built. How could Blue Origin, with its modest launch record, possibly compete?

The answer lies in a strategic pivot that documents obtained by industry sources reveal: Blue Origin is developing an entirely new "accelerated" lunar architecture that doesn't require orbital refueling. This fundamentally changes the timeline and the competition itself. Instead of a drawn-out technical race favoring SpaceX's size and experience, Blue Origin is proposing a cleaner, simpler path that could potentially put humans on the lunar surface before 2030.

This shift represents far more than a corporate rivalry. It reflects a genuine disagreement about how humanity should return to the Moon. Should we build massive, reusable infrastructure requiring complex logistics (SpaceX's approach)? Or should we pursue something leaner, faster, and arguably smarter for this particular mission? The answer will shape the next decade of lunar exploration.

TL; DR

- Blue Origin is proposing an accelerated Moon landing architecture that eliminates the need for orbital refueling, potentially landing humans before 2030

- SpaceX's Starship approach is more ambitious but faces timeline challenges, with recent test failures raising questions about readiness before 2030

- Bezos' "tortoise" metaphor suggests Blue Origin believes patience and simplicity beat raw power and complexity in reaching the Moon first

- China's independent lunar program is advancing rapidly, creating urgency for American space agencies to accelerate lunar timelines

- The competition reflects fundamental disagreements about lunar architecture philosophy, with major implications for NASA's Artemis Program and long-term space exploration strategy

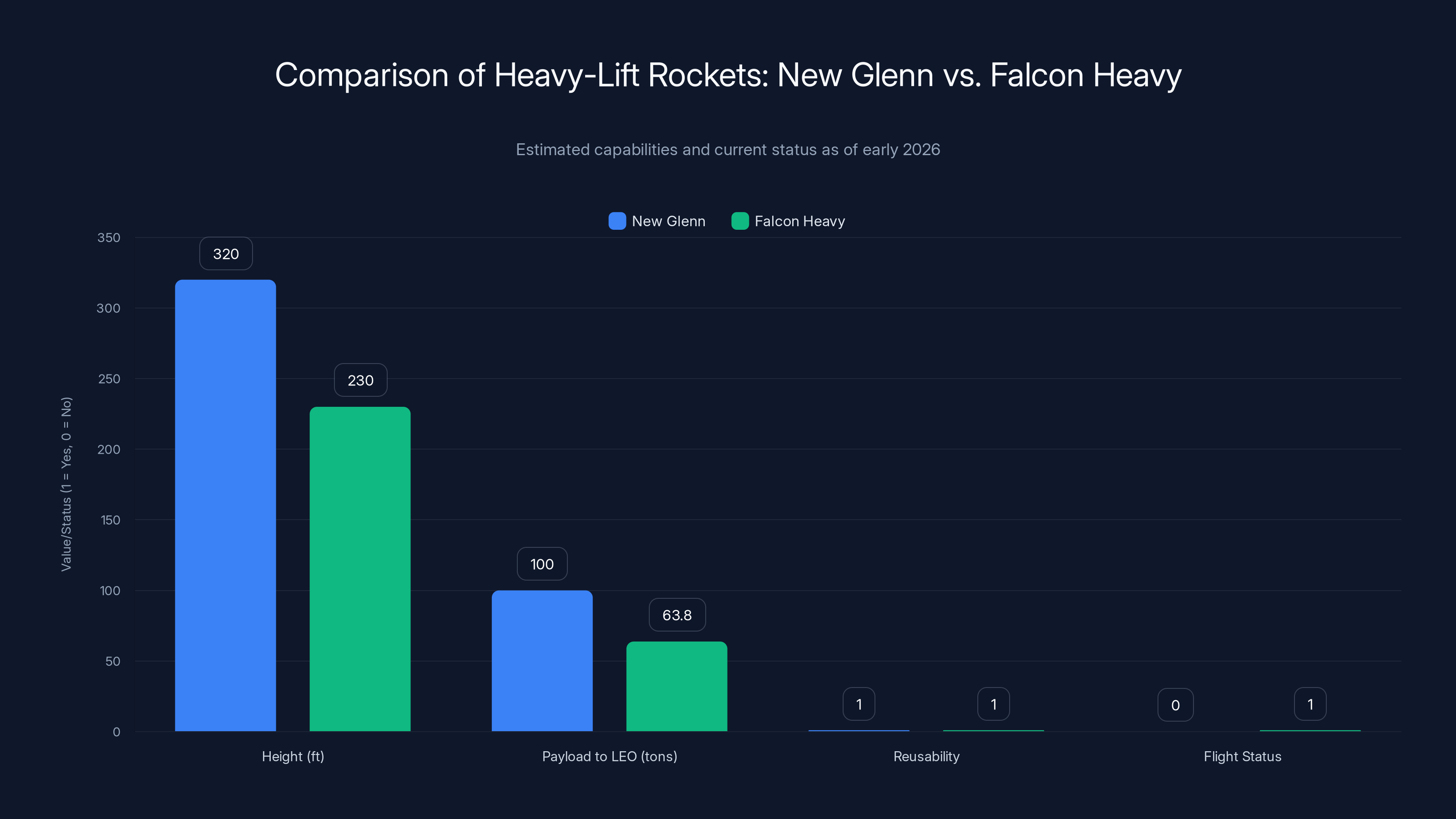

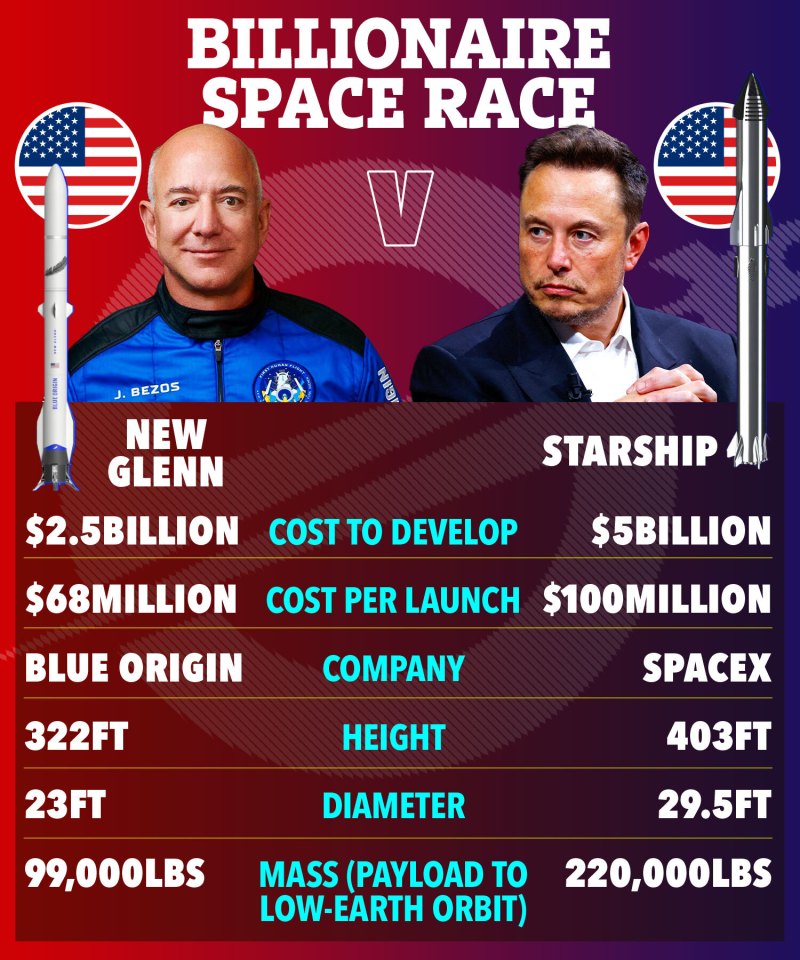

New Glenn is taller and has a higher payload capacity than Falcon Heavy, but it has yet to fly. Falcon Heavy is operational, giving SpaceX a significant lead. (Estimated data for comparison)

Understanding the Moon Race Context: Why Now?

The Moon has never left human consciousness, but our relationship with it has changed dramatically. After the Apollo program ended in 1972, the Moon became something we'd "already done." For decades, serious space exploration enthusiasts looked past the Moon toward Mars as the meaningful next destination. Yet something shifted in recent years—urgency crept back in.

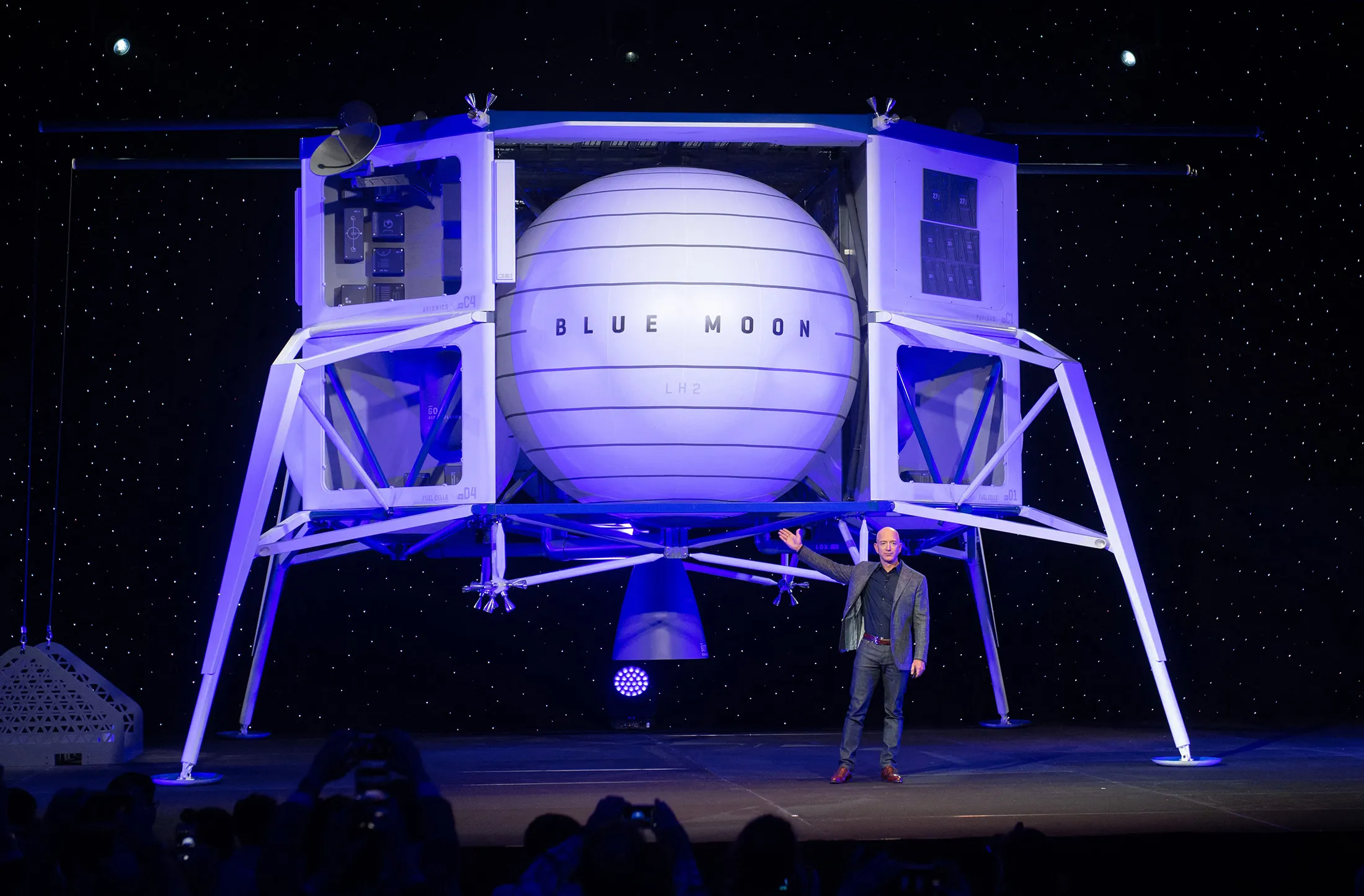

In 2019, when Bezos first publicly outlined his vision for Blue Origin's lunar program, he articulated something that resonates even more strongly today: "It's time to go back to the Moon—this time to stay." This wasn't nostalgia. It was pragmatism. Bezos recognized that the Moon isn't just a destination; it's a proving ground. Before humans live on Mars, they need to learn how to live on another world. The Moon, just three days away, is the perfect classroom.

NASA's Artemis Program, formally initiated in 2017, represents the American commitment to this philosophy. The agency set an ambitious goal: return humans to the lunar surface and establish sustainable operations. This isn't a quick flags-and-footprints mission like Apollo. Artemis imagines sustained human presence—research stations, resource utilization, the beginnings of infrastructure that could support deeper space exploration.

But there's a complication. Space exploration doesn't exist in a vacuum. China has been quietly building lunar capability for years. Chinese taikonauts haven't landed on the Moon yet, but the country's unmanned lunar program has been remarkably successful. Recent intelligence and industry analysis suggests China could potentially land humans on the Moon sometime in the late 2020s—possibly before 2030. This creates genuine urgency for American programs.

The geopolitical calculus is straightforward: whoever can sustain human presence on the Moon gains significant scientific, technological, and symbolic advantage. It's not about planting flags anymore. It's about establishing precedent, developing technology, proving capability. SpaceX and Blue Origin both understand this. But they're approaching it very differently.

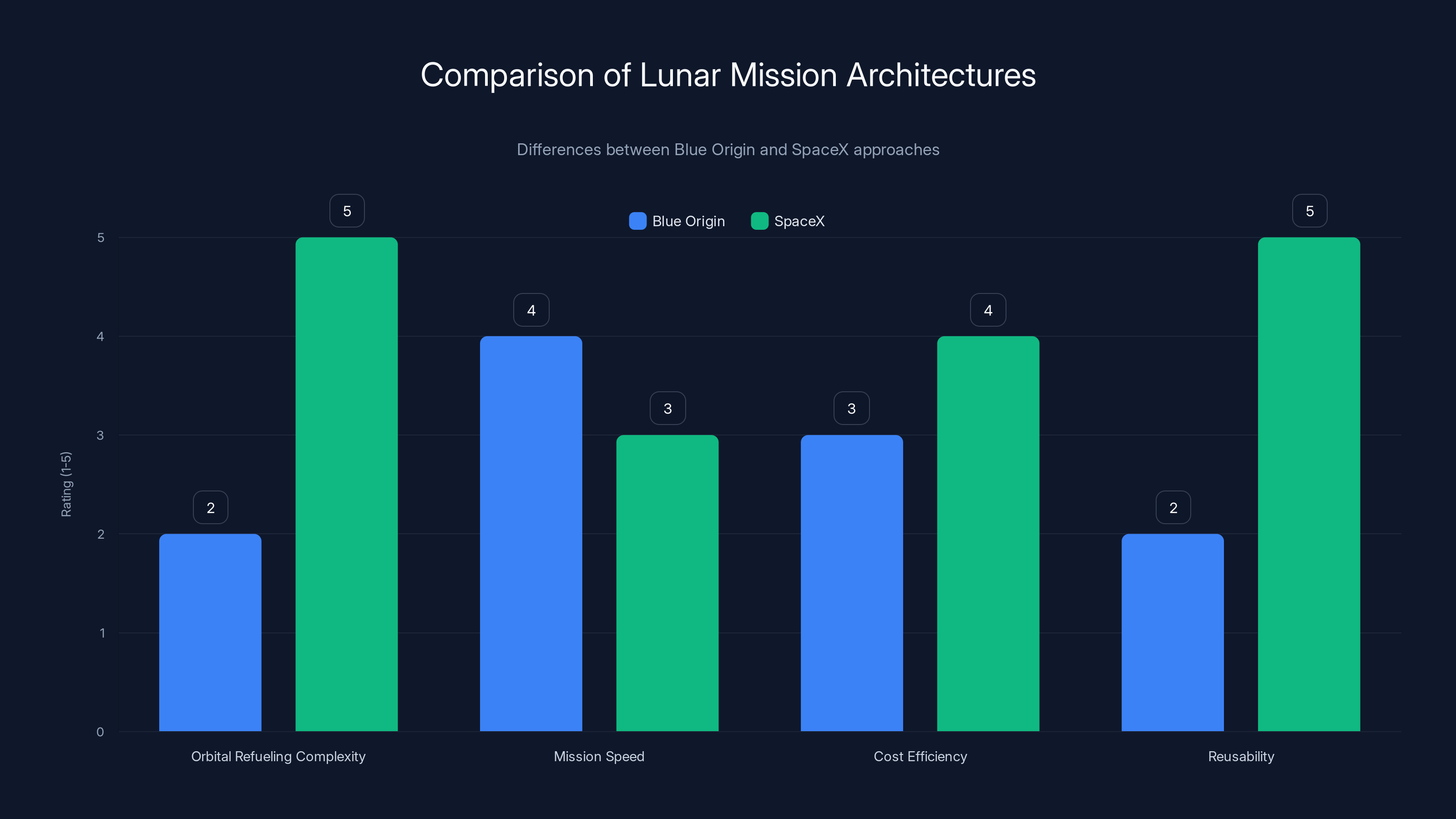

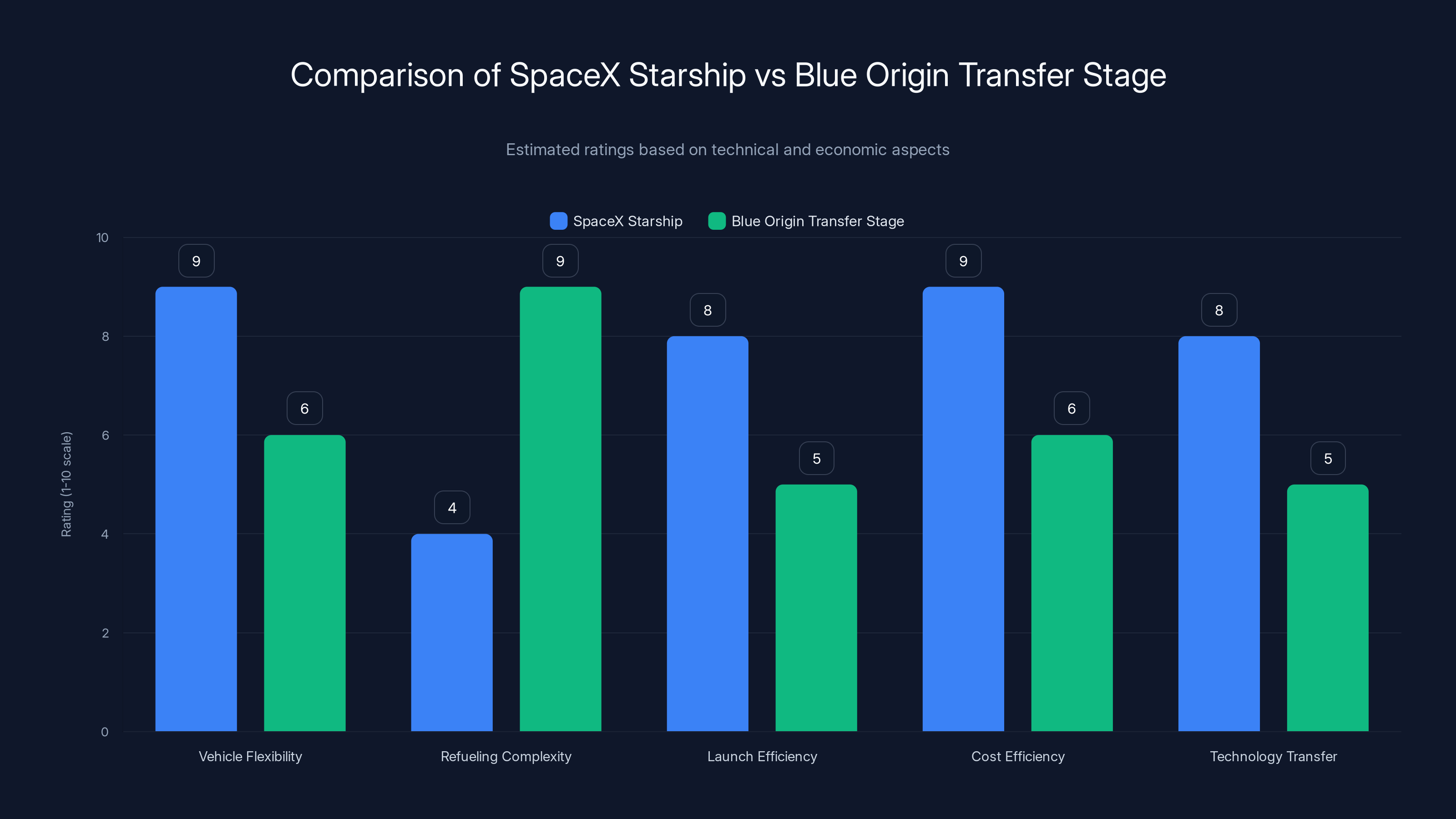

Blue Origin's approach minimizes refueling complexity and aims for faster lunar landing, while SpaceX focuses on reusability and long-term cost efficiency. (Estimated data)

SpaceX's Starship: Ambition Meets Reality

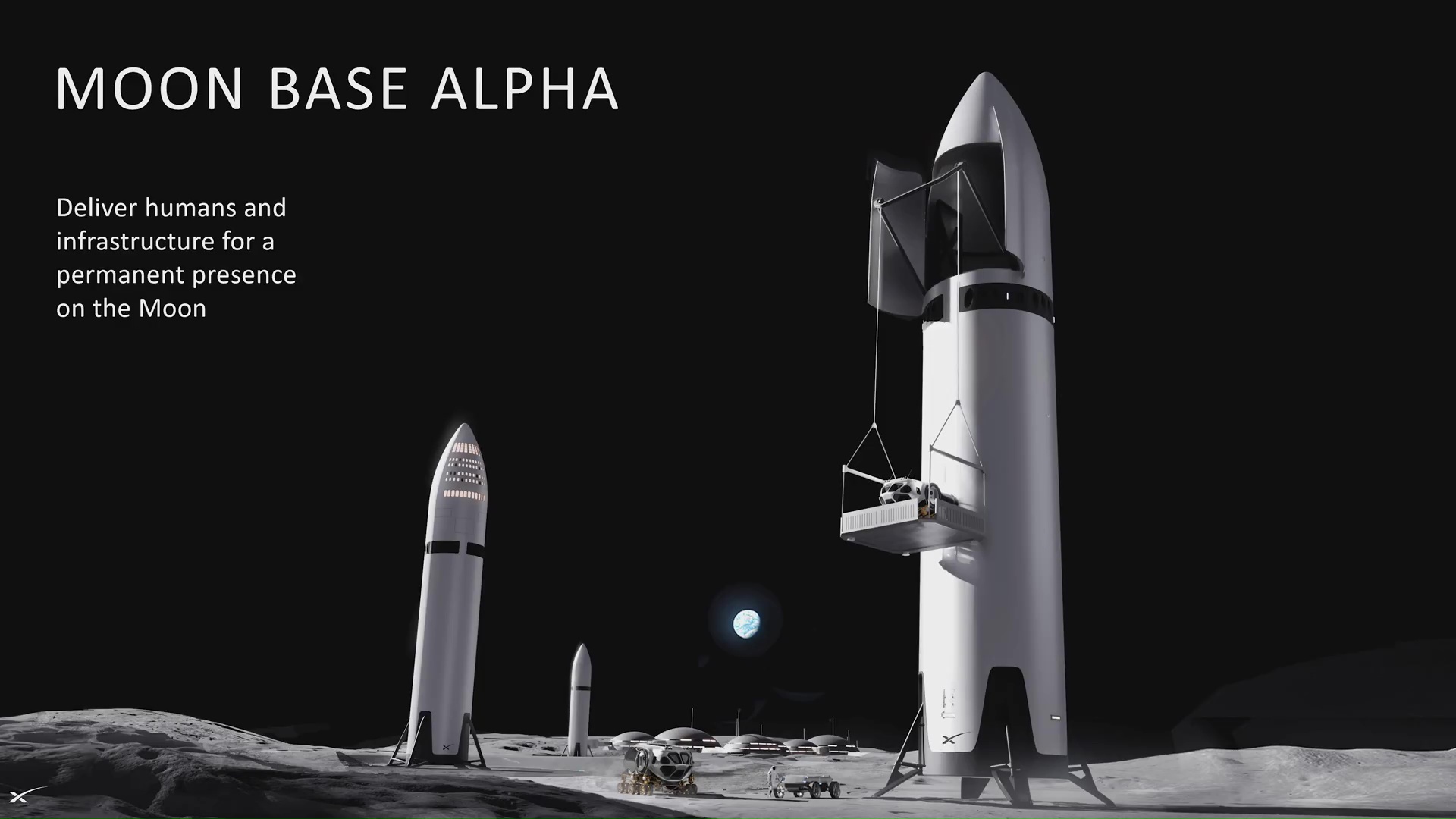

When Musk talks about Mars, he's always been thinking big. His vision for Mars colonization isn't just sending a few astronauts. It's establishing cities. It's creating a self-sustaining civilization capable of independent operation from Earth. This requires cargo, infrastructure, life support, radiation shielding, habitats. Starship, the massive stainless steel rocket system under development, was designed to make this economically feasible through full reusability.

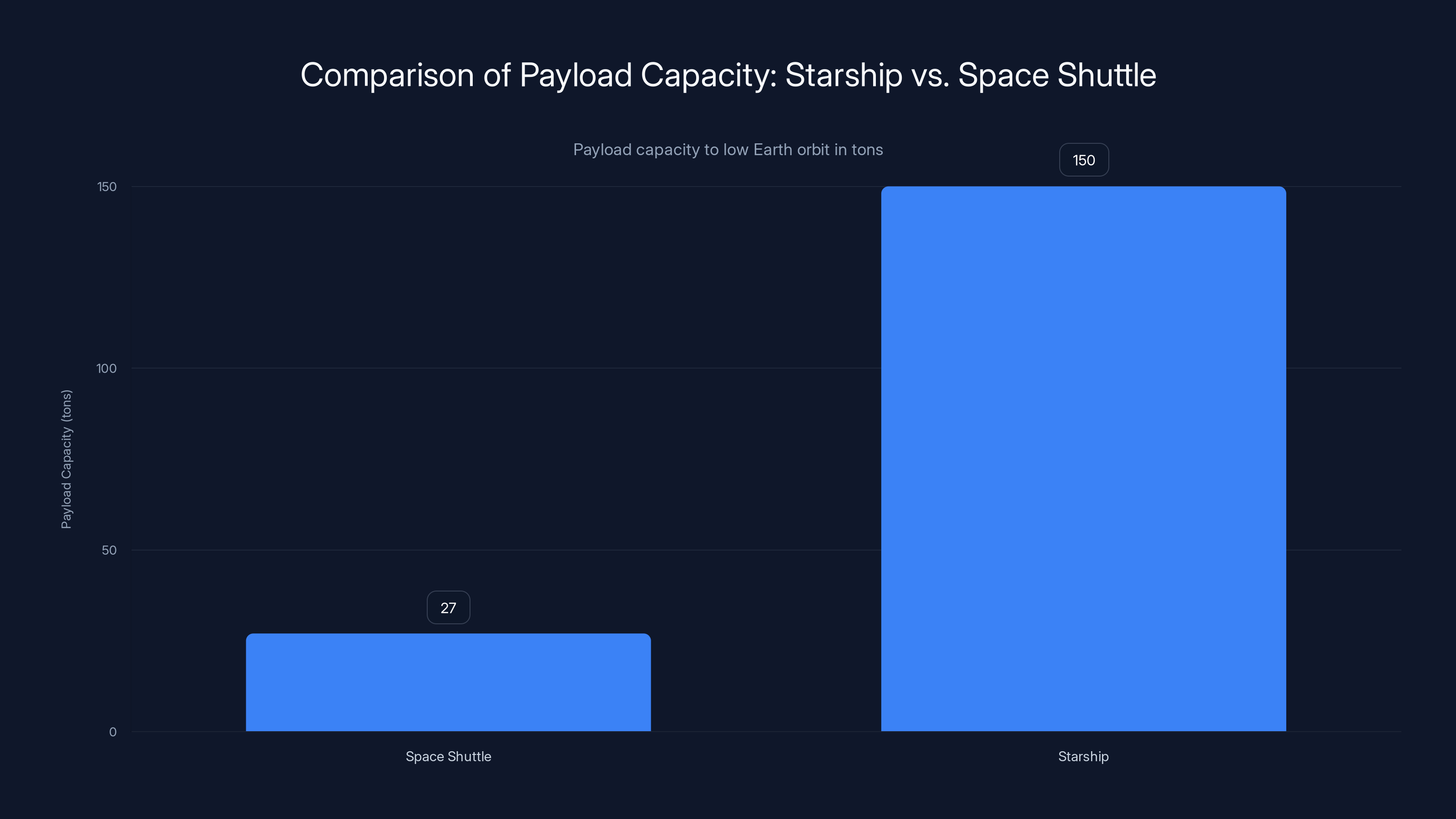

Starship is genuinely enormous. The fully stacked vehicle stands 400 feet tall and is designed to carry up to 150 tons to low Earth orbit. For comparison, the Space Shuttle could carry about 27 tons. SpaceX's vision involves launching multiple Starships, transferring fuel between them in orbit (orbital refueling), and then sending a Starship to Mars, the Moon, or anywhere else.

For lunar landing, the current NASA-contracted architecture involves these steps: Launch Starship with a crew aboard to low Earth orbit. Launch multiple tanker Starships to transfer propellant. Once refueled, launch one more crew Starship. The vehicles meet in orbit, and the crew transfers from their Starship to a specially configured lunar lander vehicle. The lander—essentially another Starship with heat shielding removed and landing legs added—descends to the Moon.

This approach is intellectually elegant. It uses the same basic platform for multiple missions. It demonstrates reusability, a core principle SpaceX has built its success upon. In theory, a single Starship vehicle could make multiple lunar visits if refurbished properly. For a program lasting decades, this efficiency is compelling.

But there's a problem: it hasn't been tested at scale yet. In 2025, SpaceX conducted three integrated flight tests of Starship. Two of them ended with dramatic explosions during the landing phase. The third was more successful but still didn't represent a complete, controlled landing of the full system. These failures don't make Starship impossible—they're expected in development of complex systems. But they've created a window of uncertainty about timeline.

When SpaceX confidently claimed it could land humans on the Moon before 2030, that timeline was already aggressive. The explosions made skeptics skeptical. Multiple industry observers now openly question whether Starship can be human-rated, fully tested, and operational for actual crewed landings in the next four years. That's not a technological impossibility—it's just a tight deadline for a complex engineering challenge.

This is where Bezos' turtle metaphor acquires teeth.

Blue Origin's Accelerated Architecture: The Pivot

Blue Origin has a very different philosophy. The company has built its reputation on methodical, incremental progress rather than revolutionary leaps. Every Blue Origin major system—the New Shepard suborbital vehicle, the New Glenn heavy-lift rocket, the Blue Moon lander—has been designed with longer-term reliability and sustainability in mind.

The New Glenn rocket, still under final development, represents Blue Origin's answer to SpaceX's Falcon Heavy and future Starship launches. It's a massive, reusable heavy-lift vehicle designed to carry 100 tons to low Earth orbit. It's not as large as fully stacked Starship, but it's purpose-built for reliability and operational efficiency.

Now, Blue Origin is proposing something different for lunar landing. The company has sketched out an "accelerated" architecture that sidesteps some of SpaceX's complexity. Instead of requiring multiple tanker launches to refuel in orbit, this approach uses what's called a "transfer stage." The transfer stage is essentially a special-purpose vehicle that carries fuel, boosts payloads from Earth orbit to lunar orbit, and then separates.

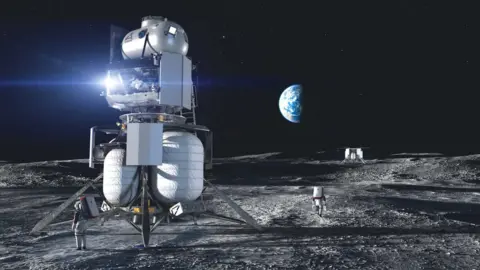

Here's how the proposed uncrewed demonstration mission would work: Three New Glenn launches place vehicles into low Earth orbit. The first two launches each deliver a transfer stage. The third launch delivers the Blue Moon MK2-IL lander (IL stands for Initial Lander, a smaller variant of the full MK2). All three vehicles dock together in orbit. The first transfer stage fires and pushes the combined stack into an elliptical Earth orbit. After that burn, the stage falls back to Earth and burns up in the atmosphere.

The second transfer stage then ignites and boosts the Moon lander from Earth orbit toward the Moon. It places the stack into a 15 by 100 kilometer orbit around the Moon—much lower than the traditional lunar orbit, but sufficient for the lander to separate and descend to the surface. The lander descends, accomplishes its mission (sampling, testing, measurements), and then ascends back to that lunar orbit where it waits for pickup on a later mission.

For a crewed mission, the architecture is more complex but fundamentally similar. Four New Glenn launches are needed. Three carry transfer stages, and one carries the lander and a smaller spacecraft to house the crew for the journey. The crew launches on a different vehicle entirely—likely a commercial capsule like Starliner or Dragon—and meets the lander in a high lunar orbit called the Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit (or NRHO, the same orbit NASA's Gateway station will occupy).

The crew transfers to the lander, the third transfer stage boosts everything to low lunar orbit, the lander separates and descends to the surface with the crew, lands, and the crew conducts their lunar operations. The lander then ascends, re-rendezvous with the crew vehicle in NRHO, and they prepare for return to Earth.

This approach has significant advantages over the SpaceX model. First, it eliminates orbital refueling complexity. There's no need for tanker vehicles, no need for precise propellant transfer operations in orbit, no need to repeatedly ignite and restart engines under microgravity conditions. Every burn in the architecture is a first burn or an early ignition in a controlled sequence.

Second, it's more modular. The transfer stages don't need to land safely. They burn up in the atmosphere after delivering their payload. This simplifies design. The lander itself only needs to land once, on the Moon. Everything is optimized for its specific role.

Third, the timeline is potentially much faster. Because the architecture doesn't depend on proving orbital refueling at scale, Blue Origin can pursue development along a more independent track. The company can develop and test the New Glenn rocket, the transfer stages, and the Blue Moon lander relatively independently. Integration happens late in the process rather than requiring everything to work together from the beginning.

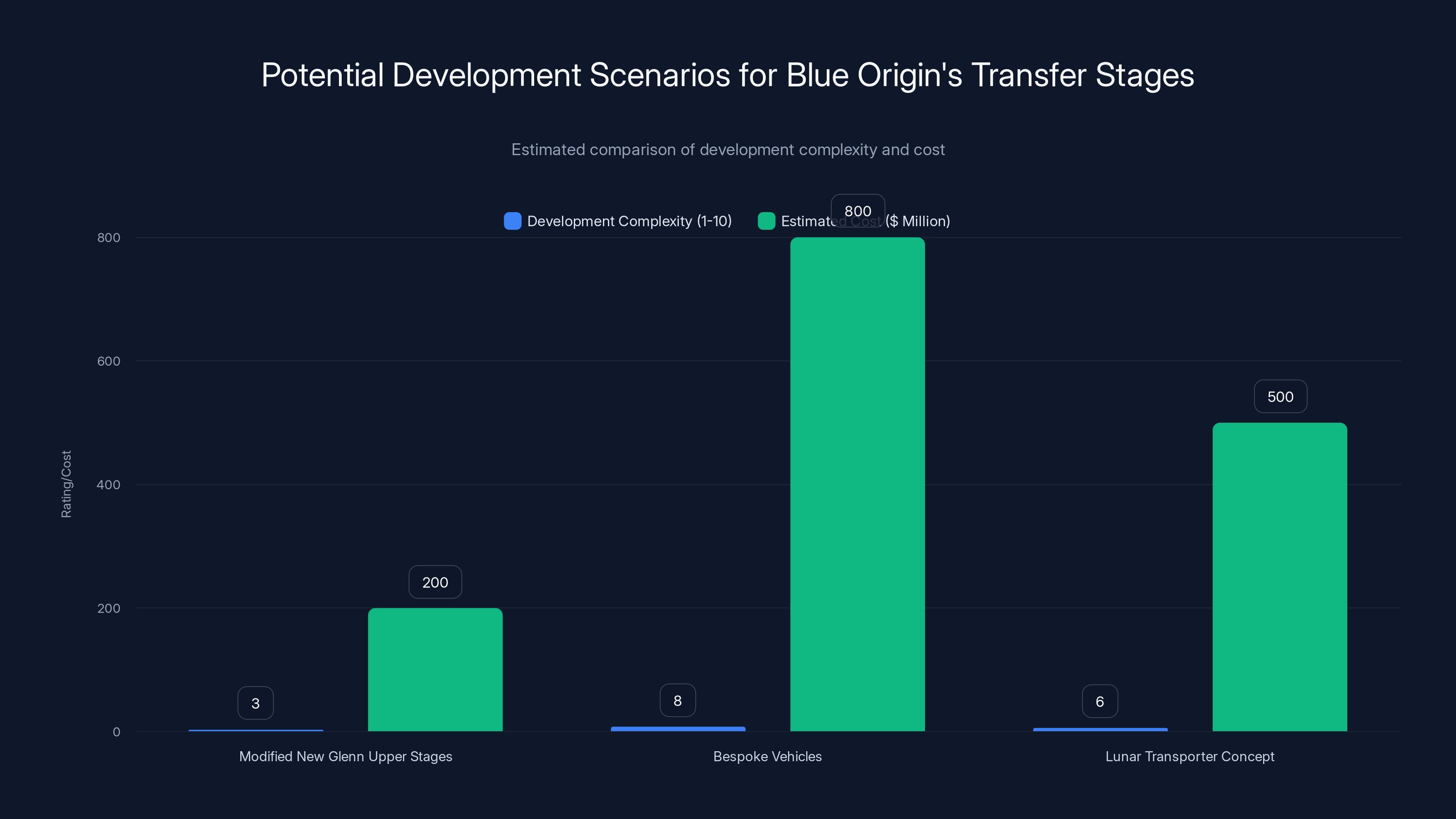

Estimated data suggest that using modified New Glenn upper stages is the least complex and costly option, while bespoke vehicles could significantly increase development complexity and costs.

The Unresolved Questions: What We Don't Know

The documents describing Blue Origin's accelerated architecture raise as many questions as they answer. Most crucially: what exactly are these transfer stages? Are they bespoke vehicles designed just for this application? Are they modified upper stages of the New Glenn rocket itself? Are they the Lunar Transporter, a reusable space tug concept Blue Origin has discussed? The documents don't specify.

This ambiguity matters because it affects timeline and cost. If the transfer stages are simply modified New Glenn upper stages, that's relatively straightforward—Blue Origin already needs to develop that upper stage for the rocket to function. But if they're entirely new vehicles, that's additional development work.

There's also the question of the Blue Moon MK2-IL itself. The "IL" designation suggests it's different from the full Blue Moon Mk 2 that NASA contracted. Is it smaller? Lighter? Does it carry less payload? Without detailed specifications, it's hard to assess whether this lander could actually accomplish significant scientific work on the lunar surface or whether it's primarily a technology demonstration vehicle.

Another unresolved question involves testing and validation. Blue Origin's current lunar lander program includes the Blue Moon Mk 1, a small uncrewed lander NASA is funding. That vehicle is scheduled to land uncrewed in 2025 or 2026. How does that fit into the accelerated architecture timeline? Does the company plan to use Mk 1 as a pathfinder, learning lessons that inform Mk 2-IL development? Or are they separate programs?

The orbital mechanics also deserve scrutiny. A 15 by 100 kilometer lunar orbit is a very low orbit, especially on the 100-kilometer periapsis side. At such a low altitude above the lunar surface, there are legitimate questions about stability, communications, and fuel margins. SpaceX's approach of reaching traditional lunar orbit before landing provides more margin for error and contingency operations.

Finally, there's the question of New Glenn itself. The rocket is not yet operational. It's under development, with a first flight date expected sometime in 2025 or early 2026. Blue Origin will need to successfully fly and validate this new rocket before it can launch lunar missions. SpaceX, by contrast, has Falcon Heavy already operational and Starship entering advanced flight testing. The comparison in terms of near-term capability is stark.

The NASA Artemis Program: Trying to Satisfy Everyone

Underlying this entire competition is NASA's Artemis Program, which has funded both SpaceX and Blue Origin to develop lunar landing capability. This is a deliberate strategy. Rather than betting on a single contractor, NASA spread risk by awarding contracts to multiple companies.

For SpaceX, the contract involves the Starship-based architecture. SpaceX is responsible for the full vehicle and development. NASA provides oversight and some funding but primarily lets SpaceX execute. For Blue Origin, the contract is for Blue Moon Mk 2 development, also with multiple NASA funding tranches tied to milestone achievement.

But here's the tension: NASA's internal planning for Artemis also assumes a specific timeline. The agency has publicly stated it intends to land humans again around 2025 or 2026. That deadline has already slipped. Now NASA is talking about the later 2020s, with some officials mentioning 2028 or 2029 as targets. But few people in the space community believe either SpaceX or Blue Origin can actually achieve crewed landings with confidence by 2026 or 2027.

This creates pressure. If Blue Origin's accelerated architecture could actually deliver a crewed landing before SpaceX's Starship-based approach, that would be a massive validation of the company's philosophy. It would also make Blue Origin the prime lunar contractor going forward, potentially relegating SpaceX to secondary roles or forcing SpaceX to develop entirely new systems.

Conversely, if SpaceX clears the hurdles—if Starship lands successfully, if orbital refueling works, if the system is human-rated—then SpaceX's reusable approach will have proven itself, and that will likely become the primary architecture for deep space exploration going forward. The economics of reusable spacecraft favor SpaceX's long-term vision.

NASA, in its official planning documents, hasn't clearly endorsed either approach over the other. The agency seems to be hedging, funding both, hoping that competitive pressure drives innovation and that at least one contractor can deliver results.

SpaceX's Starship scores higher in vehicle flexibility, launch efficiency, and cost efficiency, while Blue Origin's approach minimizes refueling complexity. Estimated data based on current architecture insights.

China's Lunar Program: The Unspoken Deadline

There's a third player in this race that rarely gets discussed in American media but motivates a lot of decision-making behind closed doors: China.

The Chinese space program has been systematically building lunar capability for years. The country has successfully landed multiple uncrewed probes on the Moon. The Chang'e missions, named after the Chinese moon goddess, represent a coordinated program that has advanced methodically and effectively. Unlike the American program, which has been marked by budget cycles, political changes, and shifting priorities, the Chinese program has maintained steady focus and incremental progress.

Recent analysis from multiple American intelligence and space industry sources suggests that China could be ready to land taikonauts (Chinese astronauts) on the Moon sometime in the late 2020s. Some estimates suggest this could happen as early as 2028 or 2029. The Chinese space administration hasn't announced an official date, but the technical capability is advancing steadily.

If China lands humans on the Moon before the United States in a second lunar age, the symbolic and geopolitical consequences would be significant. It wouldn't mean China is inherently superior at space exploration—the programs have different philosophies and constraints. But it would represent a milestone moment, a passing of the torch that would resonate globally.

This reality creates genuine urgency for both SpaceX and Blue Origin. It's not just about beating each other; it's about ensuring that an American program lands first. This urgency infuses Bezos' turtle post with additional meaning. The message isn't just "we'll beat you eventually." It's "we'll beat both you and China if we execute properly."

Orbital Refueling: The Technical Crux

One of the most fundamental disagreements between these companies involves orbital refueling. SpaceX's architecture depends on it. Blue Origin's accelerated approach avoids it. Why is this such a big deal?

Orbital refueling sounds straightforward in principle. You launch a tanker vehicle with fuel. You send a spacecraft to rendezvous with that tanker. You transfer fuel from the tanker to the spacecraft. Simple.

In practice, it's one of the most complex operations in spaceflight. Fuel transfer in microgravity is challenging. You're dealing with cryogenic propellants—liquid methane and liquid oxygen in SpaceX's case—at extremely low temperatures. In orbit, these propellants can boil off, they can separate, they can cause unexpected pressure surges. The plumbing and the procedures have to be absolutely precise.

Moreover, you need to do this repeatedly and reliably. SpaceX's vision involves launching multiple tankers for each lunar mission. That means performing this complex operation multiple times in sequence before committing a crewed spacecraft.

SpaceX engineers argue that orbital refueling is achievable and will eventually become routine. In the long term, they're probably right. But "long term" is key. The learning curve for reliably performing these operations at scale could stretch timeline.

Blue Origin's approach bypasses this problem entirely by using transfer stages that don't return. You launch the transfer stage, it does its job, it burns up. No refueling required. This trades eventual operational efficiency for near-term timeline advantage.

From a purely technical standpoint, both approaches will work eventually. The question is which works first, at scale, with human crews depending on it.

SpaceX's Starship is designed to carry up to 150 tons to low Earth orbit, significantly surpassing the Space Shuttle's capacity of 27 tons.

The New Glenn Factor: Blue Origin's Wild Card

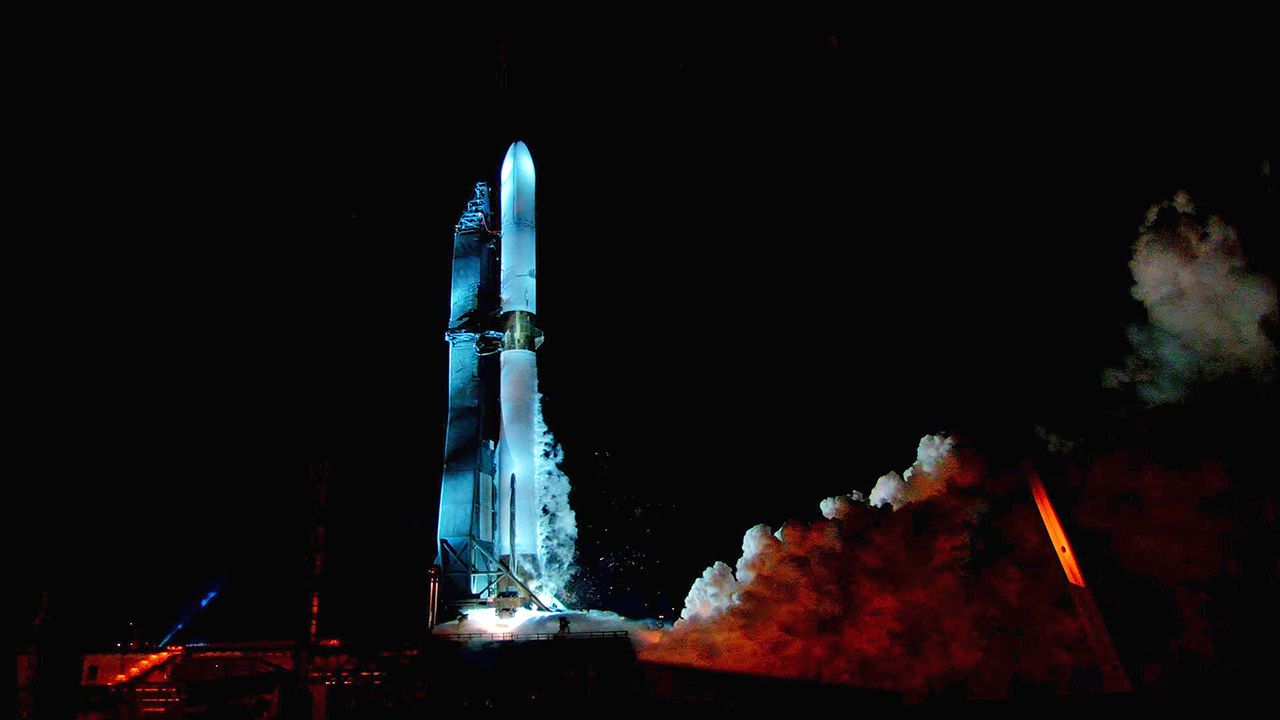

Blue Origin's entire accelerated architecture depends on a rocket that hasn't flown yet: the New Glenn.

This is a critical point. New Glenn is a massive engineering undertaking. The rocket is designed to be 320 feet tall, capable of carrying 100 tons to low Earth orbit. It uses a unique engine design (the BE-4 engine, heavily modified from the engine Blue Origin supplies to United Launch Alliance). It's intended to be fully reusable, with the first stage returning to the launch site after release of the upper stage.

For Blue Origin's lunar plans to work on their claimed timeline, New Glenn needs to become operational and then fly multiple times successfully. The company has been developing New Glenn for years, but a first flight hasn't happened yet as of early 2026. If New Glenn experiences delays—which is not uncommon for new heavy-lift rockets—Blue Origin's entire lunar schedule slips.

SpaceX, by comparison, has Falcon Heavy already flying. The company also has Starship actively testing. While Starship has experienced failures, the rocket is being tested. SpaceX is accumulating flight data. Engineers are iterating rapidly.

This is another way the "tortoise vs. hare" metaphor breaks down when you examine the details. The hare (SpaceX) is already sprinting. The tortoise (Blue Origin) is still getting ready to start the race, depending on a vehicle that hasn't flown yet.

Technical Comparison: Architecture Deep Dive

Let's break down the two approaches side by side to understand their relative merits.

SpaceX Starship Approach:

- Uses one vehicle type for everything (Starship)

- Relies on in-space refueling operations (complex, unproven at scale)

- Eliminates single-use vehicles (theoretically more efficient long-term)

- Requires fewer total launches if refueling works reliably

- Starship technology could be applied to Mars and other deep space missions

- Current challenges: Starship testing has experienced failures; timeline to human-rating uncertain

- Cost trajectory: If successful, reusable approach scales economically

Blue Origin Transfer Stage Approach:

- Uses purpose-built vehicles for each mission role

- Eliminates complex orbital refueling from the critical path

- Requires more total launches to accomplish same mission

- Stages are expendable, increasing operational costs long-term

- Less technology transfer to other mission types

- Current challenges: New Glenn hasn't flown yet; entire architecture depends on new rocket

- Cost trajectory: Expendable stages mean higher per-mission costs

From an engineering standpoint, the SpaceX approach is more elegant and economical for a sustained program. From a near-term timeline perspective, Blue Origin's approach eliminates a major technical hurdle.

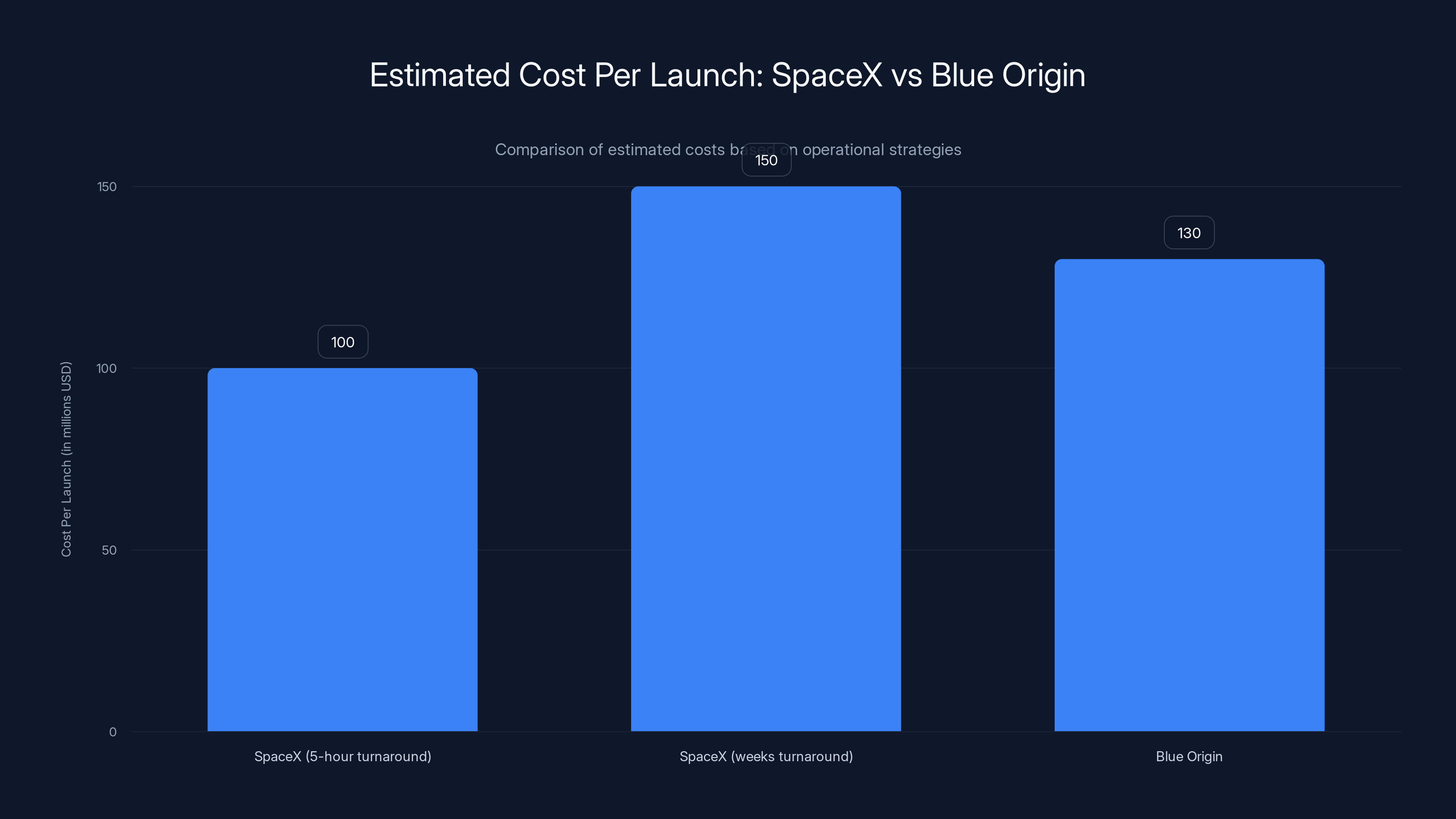

Estimated data suggests SpaceX could achieve lower costs with rapid turnaround, but costs increase with longer intervals, making Blue Origin competitive.

The Political and Funding Dimension

It's worth noting that these technical choices exist in a political context. Both companies are dependent on NASA funding to some degree. SpaceX has the advantage of a broader commercial spaceflight business (launching satellites, cargo resupply missions, etc.) that funds ongoing operations. Blue Origin's main revenue source is the New Glenn development contract and various government programs.

If the Trump administration, or any future administration, decided to heavily fund one approach over the other, that would affect timeline and priority. SpaceX has been the administration's preferred contractor for national security launches. Blue Origin has had to work harder to prove its case.

Additionally, Blue Origin's shift to an accelerated approach might be partly strategic positioning. By proposing a path to lunar landing before 2030 without relying on orbital refueling, Blue Origin is essentially saying: "We can deliver this if given priority and steady funding." It's a competitive move designed to win future contracts and demonstrate capability.

SpaceX, conversely, is staying the course. Musk's pivot from Mars to Moon as a near-term focus is interesting, but SpaceX's fundamental technical approach hasn't changed. The company is still betting on Starship, still betting on reusability, still betting on the long-term vision.

Risk Assessment: What Could Go Wrong

For SpaceX, the risks are concentrated in Starship development and human-rating. If Starship continues to fail in test flights, if the learning curve proves longer than expected, if there are structural or engineering problems discovered during the human-rating process, timeline extends significantly. NASA will not send humans to the Moon on an unproven vehicle. The stakes are too high. Public confidence in the program depends on demonstrated reliability.

For Blue Origin, the risks are broader. New Glenn is a new rocket with unproven systems. The transfer stage concept requires validation. The Blue Moon Mk 2-IL design needs to be finalized and tested. The integrated mission architecture needs to be validated. Any of these could experience delays.

Additionally, Blue Origin faces a credibility gap. The company has only launched to orbit twice. Its human spaceflight experience is limited to brief suborbital flights on New Shepard. Many people in the space community are skeptical that Blue Origin can execute on this accelerated timeline, regardless of the technical merits of the architecture.

China's timeline also introduces uncertainty. If China lands humans on the Moon in 2028, that doesn't invalidate American efforts, but it does change the symbolic and geopolitical context. American programs would be answering China's achievement rather than setting their own pace.

Economic Implications: Cost Per Launch and Mission

One factor often overlooked in this comparison is cost. SpaceX's reusable approach, if it achieves rapid turnaround, should eventually become cheaper per flight. But "eventually" is the operative word. Developing the infrastructure to turn around Starships quickly, to inspect them thoroughly between flights, to maintain launch facilities, all of this requires significant investment.

Blue Origin's transfer stage approach, using expendable components, is more expensive per mission initially. But if New Glenn achieves operational status with good launch frequency, the overall cost structure becomes reasonable. The company benefits from a simpler vehicle architecture that requires less maintenance between flights.

Mathematically, if SpaceX can achieve a five-hour turnaround between Starship launches, with each launch costing $100 million in propellant and operational costs, the economics become compelling. But if turnaround stretches to weeks and operational costs climb, Blue Origin's approach becomes competitive on pure cost grounds.

These are estimates, and both companies guard their actual costs closely. But the math of reusability is complex, and SpaceX's theoretical advantage depends on achieving operational cadences that are historically difficult in spaceflight.

The Broader Implications for Space Exploration

Beyond just who lands first, this competition shapes the future of human space exploration.

If SpaceX succeeds with Starship, the implications are profound. A fully reusable, super-heavy-lift vehicle opens economic possibilities that were previously theoretical. Mars becomes more feasible. Orbital manufacturing becomes practical. The cost to access space drops by orders of magnitude. SpaceX's long-term vision of multi-planetary civilization gains credibility.

If Blue Origin succeeds with its accelerated approach, the implications are different but equally significant. It validates a more cautious, step-by-step philosophy. It demonstrates that the Moon is an achievable near-term goal without requiring breakthrough technologies. It suggests that multiple contractors can win major space missions, which encourages competition and diversity.

From a NASA perspective, the ideal outcome is likely both succeeding but on different timelines. NASA could use Blue Origin's architecture for the initial Artemis missions, landing humans by 2028-2029. Simultaneously, SpaceX could develop Starship capability for subsequent missions. By the early 2030s, NASA would have multiple options and redundancy in its lunar capability.

But competition rarely produces ideal outcomes. Someone wins, and winners shape the future.

Industry Response and Next Steps

The space industry is watching this competition intently. Other contractors—United Launch Alliance, Sierra Space, Axiom Space—have roles in the lunar economy, but SpaceX and Blue Origin are the primary competitors for landing systems.

Other countries' space agencies are also watching. The European Space Agency, Japan's JAXA, even smaller space nations are evaluating which American approach aligns with their own goals. Some may prefer the reusable Starship model for long-term partnership. Others might prefer the modular Blue Origin approach.

Private companies are also affected. If SpaceX wins the race with Starship, companies interested in orbital manufacturing or space-based resources look to SpaceX as a foundational infrastructure provider. If Blue Origin wins, the space industry develops along different lines.

The next 18-24 months will be decisive. SpaceX needs successful, unmanned Starship landings, ideally some rapid test-flight sequence. Blue Origin needs New Glenn first flight success and demonstration of the transfer stage concept. Whichever company achieves major technical milestones first gains momentum, attracts additional contractors to their supply chain, and likely wins the race to land humans.

Historical Context: Echoes of the Space Race

There's something almost nostalgic about this competition, though the parallels to Apollo are limited. The original Moon race was driven by Cold War competition and nationalist fervor. This competition is driven by commercial competition and billionaire ambition.

But the underlying pattern is similar: two organizations pursuing the same goal via different technical approaches, learning from competition, pushing each other toward the goal faster than either might reach it alone.

During Apollo, NASA funded both a Lunar Orbit Rendezvous approach (used for the missions that landed) and a Lunar Module approach (the alternative architecture). Competition between different NASA centers and contractors led to innovation. The winning approach (Lunar Orbit Rendezvous) was championed by NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston and became the cornerstone of the program.

Today's competition plays a similar role, even if it's nominally within the same NASA program. SpaceX and Blue Origin are competing architectures, and that competition creates pressure for excellence.

The difference is that both contractors are private companies with their own incentives and long-term visions. This introduces elements the Apollo program never navigated—proprietary technology, competing agendas beyond the current mission, the possibility that one contractor might drop out if they believe they're not winning.

Looking Forward: 2026-2030

The next few years will determine the trajectory of lunar exploration for the following decade. Based on current timelines and known developments:

2026: New Glenn conducts first crewed flights (or completes initial unmanned flights). Blue Origin's lunar architecture becomes clearer as design matures. SpaceX continues Starship testing with focus on controlled landing techniques.

2027: Both companies target major technical demonstrations. SpaceX aims for Starship orbital refueling demonstrations or at least completed test sequence. Blue Origin targets integrated New Glenn and transfer stage operations.

2028-2029: One or both companies likely demonstrate uncrewed lunar missions. This is the real test—landing on the Moon, operating equipment, ascending safely. Whichever company achieves this first gains enormous advantage in the crewed race.

2029-2030: Crewed lunar missions become possible if uncrewed demonstrations succeed. The first American crewed landing since Apollo 17 in 1972 could happen in this window, if programs execute well.

This timeline is optimistic in some respects, realistic in others. History suggests that first crewed missions to anywhere don't happen on accelerated schedules. But these companies are betting on doing exactly that.

The Real Winner: Space Exploration

Regardless of whether the tortoise or the hare wins this race, the outcome favors space exploration. If Blue Origin achieves crewed lunar landing first, that validates a methodical approach and demonstrates that experience advantage isn't absolute. If SpaceX succeeds first, that validates the reusable spacecraft philosophy and opens economic possibilities for deep space.

Most likely, both will eventually succeed, but on different timelines. The first American crewed lunar landing in the 21st century will likely happen on either Starship or a Blue Moon lander. Subsequent missions will probably use both systems, establishing a lunar economy that supports science, resource exploration, and eventually human settlement.

Bezos' turtle post might seem like simple trolling, but it represents something deeper: confidence in a different approach, belief in slow and steady methodology, and faith that the simplest solution often wins in the end. Whether that confidence is justified will become clear over the next few years.

For now, the race is on. The Moon waits for humans to return, and two billionaires are racing to determine who gets there first. May the best architecture win.

FAQ

What is Blue Origin's accelerated lunar architecture?

Blue Origin's accelerated lunar architecture is a mission design that eliminates the need for orbital refueling by using expendable transfer stages to boost spacecraft from Earth orbit to lunar orbit. The architecture requires multiple launches of the New Glenn rocket, with each launch delivering either a transfer stage or a lander component. The transfer stages dock in orbit, perform a series of burns to reach the Moon, and then burn up in the atmosphere. This approach is designed to land humans on the Moon before 2030 without requiring the complex fuel transfer operations that SpaceX's Starship architecture depends on.

How does the Blue Origin approach differ from SpaceX's Starship architecture?

The primary difference is that SpaceX's Starship architecture depends on in-space propellant refueling, where multiple tanker vehicles transfer fuel to a single spacecraft that will make the lunar journey. Blue Origin's approach uses expendable transfer stages that are launched alongside the lander, dock in orbit, perform their burns, and are discarded. SpaceX's approach is theoretically more economical long-term because Starship vehicles are reusable, but Blue Origin's approach avoids the technical complexity of orbital refueling and potentially achieves crewed lunar landing faster.

Why is Bezos posting turtle images on social media?

Bezos' turtle images reference Aesop's Fable of "The Tortoise and the Hare," in which the slow and steady tortoise defeats the faster but overconfident hare. Blue Origin's coat of arms features two turtles for this very reason. By posting the image after Musk announced SpaceX was pivoting to the Moon, Bezos was suggesting that Blue Origin's methodical approach will ultimately succeed faster than SpaceX's more ambitious but technically complex architecture. It's competitive messaging wrapped in ancient mythology.

What is the significance of New Glenn for Blue Origin's lunar plans?

New Glenn is the heavy-lift rocket on which Blue Origin's entire accelerated lunar architecture depends. Without New Glenn becoming operational and flying successfully multiple times, Blue Origin cannot execute its proposed mission sequence. New Glenn has not yet flown as of early 2026, which represents a timeline risk. If the rocket experiences delays, Blue Origin's lunar schedule automatically slips. This is Blue Origin's critical dependency, whereas SpaceX has multiple rockets already operational that could theoretically support lunar missions.

Could China's lunar program affect the U. S. space race timeline?

Yes, significantly. Intelligence assessments suggest China could land taikonauts on the Moon sometime in the late 2020s, possibly as early as 2028-2029. This creates geopolitical urgency for American space programs. If China achieves crewed lunar landing before the United States, it represents a symbolic milestone even if it doesn't represent superior spaceflight capability. This possibility drives both SpaceX and Blue Origin toward earlier timelines and helps justify accelerated NASA Artemis Program schedules.

What is orbital refueling and why is it controversial?

Orbital refueling involves launching a tanker vehicle with fuel, having it rendezvous with another spacecraft in orbit, and transferring cryogenic propellants (like liquid methane and liquid oxygen) from one vehicle to another in microgravity conditions. It's controversial because it's technically complex—fuel can boil off, pressures can surge unpredictably, precise procedures are required—and it's unproven at the scale SpaceX proposes. While some space engineers believe it's achievable, others question whether it can be reliably performed multiple times per mission for crewed operations. Blue Origin's approach avoids this complexity entirely.

How many New Glenn launches would each mission type require?

According to Blue Origin's documented architecture, an uncrewed demonstration mission requires three New Glenn launches (two transfer stages and one lander). A crewed mission requires four New Glenn launches (three transfer stages and one lander). This is significantly more launches than SpaceX's refueling approach would theoretically require, but each individual launch is simpler and doesn't depend on complex orbital operations that could fail.

What timeline is realistic for crewed lunar landing?

Based on current development status, a realistic timeline for first crewed lunar landing is 2028-2030, with either company potentially achieving it depending on development pace and testing results. Neither company will have humans on the Moon before 2028 with current schedules and realistic technical expectations. However, both companies have announced ambitions to attempt crewed missions in this window, and if uncrewed demonstrations succeed in 2027-2028, crewed missions could follow quickly.

Why does NASA fund both SpaceX and Blue Origin for lunar missions?

NASA deliberately funds multiple contractors to reduce risk and encourage competition. If the agency bet everything on one company and that company experienced delays, the entire program would be delayed. By funding both SpaceX (Starship approach) and Blue Origin (Blue Moon approach), NASA hedges against timeline slippage. The competition also encourages innovation and reduces the chance that both contractors would miss deadline. The downside is higher overall program cost, but the upside is redundancy and competitive pressure driving performance.

Could both companies successfully land humans on the Moon?

Yes, absolutely. The most likely long-term outcome is that both SpaceX and Blue Origin achieve successful crewed lunar landing, likely separated by months or a year or two. After the initial race to be first, NASA would likely use both systems for subsequent Artemis missions, with each contractor handling different objectives or time periods. This would maximize the government's lunar capability and ensure multiple pathways for accessing the Moon.

Conclusion

Jeff Bezos' turtle post was more than a billionaire trolling a rival on social media. It was a calculated assertion of Blue Origin's confidence in a fundamentally different approach to returning humans to the Moon. While SpaceX pursues a path based on massive reusable rockets and complex orbital refueling operations, Blue Origin is betting on a simpler, more direct architecture using expendable transfer stages and the yet-untested New Glenn rocket.

Who will win this race? The honest answer is that it's still uncertain. SpaceX has more flight heritage and a more ambitious long-term vision. Blue Origin has a potentially simpler near-term path and methodical development philosophy. Both companies are motivated by a mixture of genuine belief in their approaches, competitive drive, and the knowledge that the next few years will determine who shapes lunar exploration for the following decade.

What we know for certain is that this competition will accelerate progress. Both companies will push harder, test more aggressively, and innovate faster because the other company is pursuing the same goal. Whether the tortoise or the hare wins, space exploration benefits from the competition.

The Moon has waited over 50 years for human visitors to return. By 2030, if both companies execute as planned, humans will finally be back. Whether they arrive aboard a Starship or a Blue Moon lander might depend on whether engineering triumphs over ambition, or ambition triumphs over complexity. The answer will reshape not just the Moon race, but the future of human spaceflight itself.

For now, the race continues. Bezos has thrown down his turtle. Musk is accelerating his hare. The Moon awaits the result.

Key Takeaways

- Blue Origin proposes an accelerated lunar architecture using expendable transfer stages that avoids the complexity of orbital refueling that SpaceX depends on.

- SpaceX's Starship approach is more elegant long-term through reusability but faces timeline risks from recent test failures in 2025.

- Both companies are racing to land humans on the Moon before 2030, with the winner potentially shaping all subsequent deep space exploration.

- China's advancing lunar program creates genuine urgency for American space initiatives, adding geopolitical pressure beyond corporate rivalry.

- New Glenn rocket must achieve operational status for Blue Origin's timeline to be credible, representing the company's critical dependency.

Related Articles

- Why Elon Musk Pivoted from Mars to the Moon: The Strategic Shift [2025]

- SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]

- Commercial Deep Space Program: Congress Shifts NASA Strategy [2025]

- SpaceX Super Heavy Booster Cryoproof Testing Explained [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

- Ariane 6 Rocket: Europe's Heavy-Lift Success & Space Launch Evolution

![Bezos vs Musk: The Race Back to the Moon [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/bezos-vs-musk-the-race-back-to-the-moon-2025/image-1-1770997169927.jpg)