NASA Space X Crew-12 ISS Docking Mission: Everything You Need to Know

The moment a rocket clears the launch pad at Cape Canaveral never gets old. On February 13, 2025, at 5:15 AM Eastern, SpaceX's Falcon 9 lifted off carrying four astronauts toward the International Space Station. What started that morning culminated hours later with one of spaceflight's most critical operations—the docking of the Dragon capsule to humanity's most ambitious orbital laboratory.

This was Crew-12, SpaceX's 20th crewed mission. But don't let the routine number fool you. Every single crew rotation to the ISS represents months of preparation, millions of dollars in investment, and the meticulous choreography of space agencies across the globe working toward a shared goal: keeping continuous human presence in low Earth orbit.

Let's walk through what made this mission significant, how the docking unfolded, who these astronauts are, and what they're actually going to do for the next eight months aboard the station.

What Is Crew-12 and Why It Matters

Crew-12 isn't just another supply run with people aboard. This is the 12th operational crew rotation to the ISS under NASA's Commercial Crew Program, a partnership between NASA, SpaceX, and commercial partners designed to end American dependence on Russian spacecraft for human spaceflight.

Let's rewind for context. Before SpaceX's Crew Dragon became operational in 2020, the United States hadn't launched humans from its own soil in nearly a decade. After the Space Shuttle retired in 2011, NASA relied exclusively on Soyuz spacecraft from Roscosmos to ferry astronauts to and from the station. That dependence became increasingly uncomfortable as geopolitical tensions rose.

SpaceX changed that. Starting with Crew-1 in November 2020, the company has demonstrated that private industry, working alongside government space agencies, could reliably transport humans to orbit and back. By February 2025, they'd logged dozens of successful crewed missions with zero fatalities and an enviable safety record.

Crew-12 continues this track record. The mission carried four astronauts representing three space agencies: NASA, the European Space Agency, and Roscosmos. That international composition matters. The ISS exists because nations that might otherwise be adversaries on Earth chose cooperation in space. Crew-12 embodied that partnership.

The timing was also notable. Crew-12 arrived just over a month after Crew-11 returned home, a shorter than usual gap driven by an unexpected medical situation that forced NASA to bring the previous crew home early. That decision demonstrated NASA's commitment to crew safety above schedule convenience—a principle that's fundamental to human spaceflight.

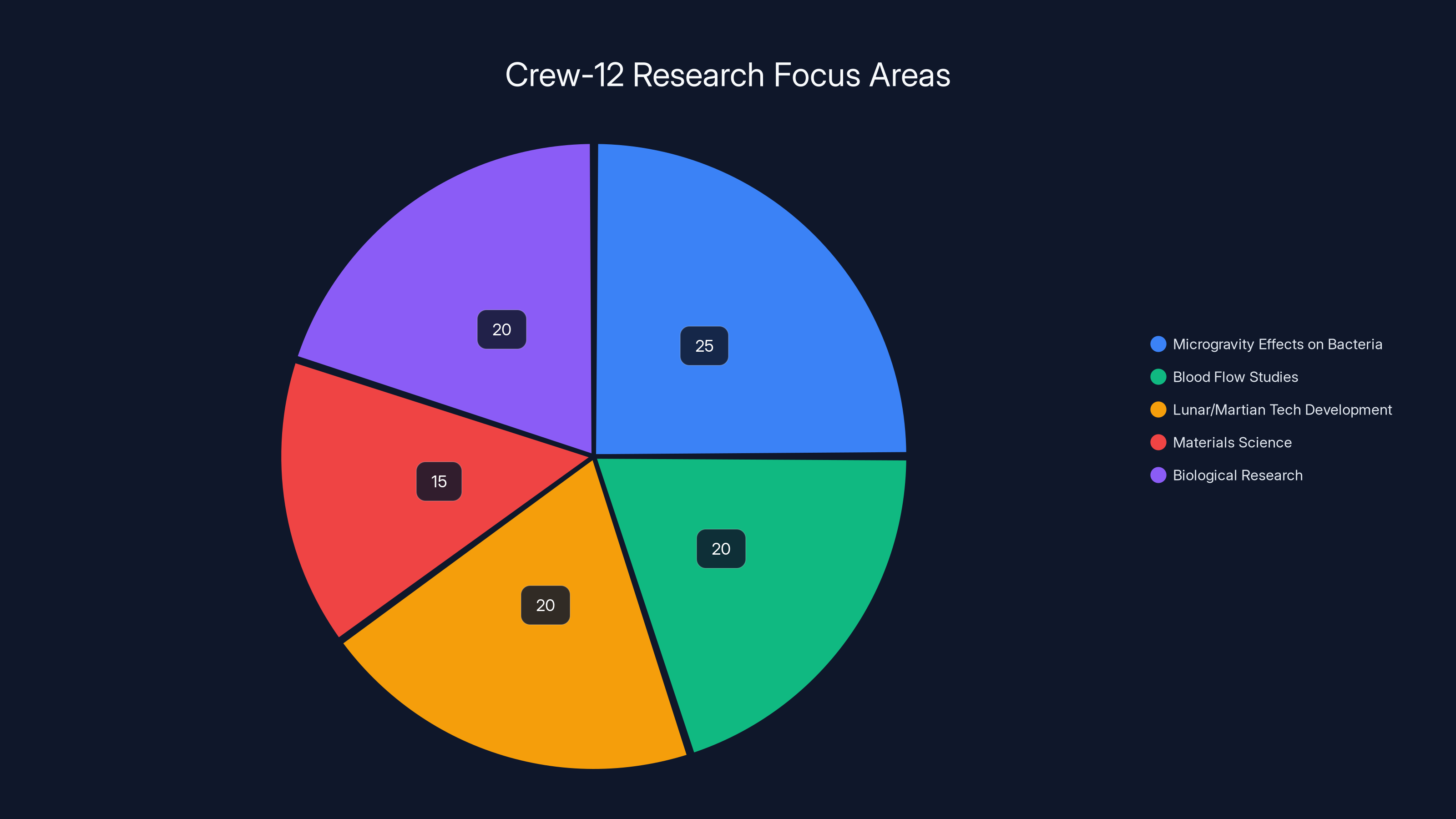

Estimated data shows a balanced focus on various research areas, with significant attention to microgravity effects on bacteria and blood flow studies.

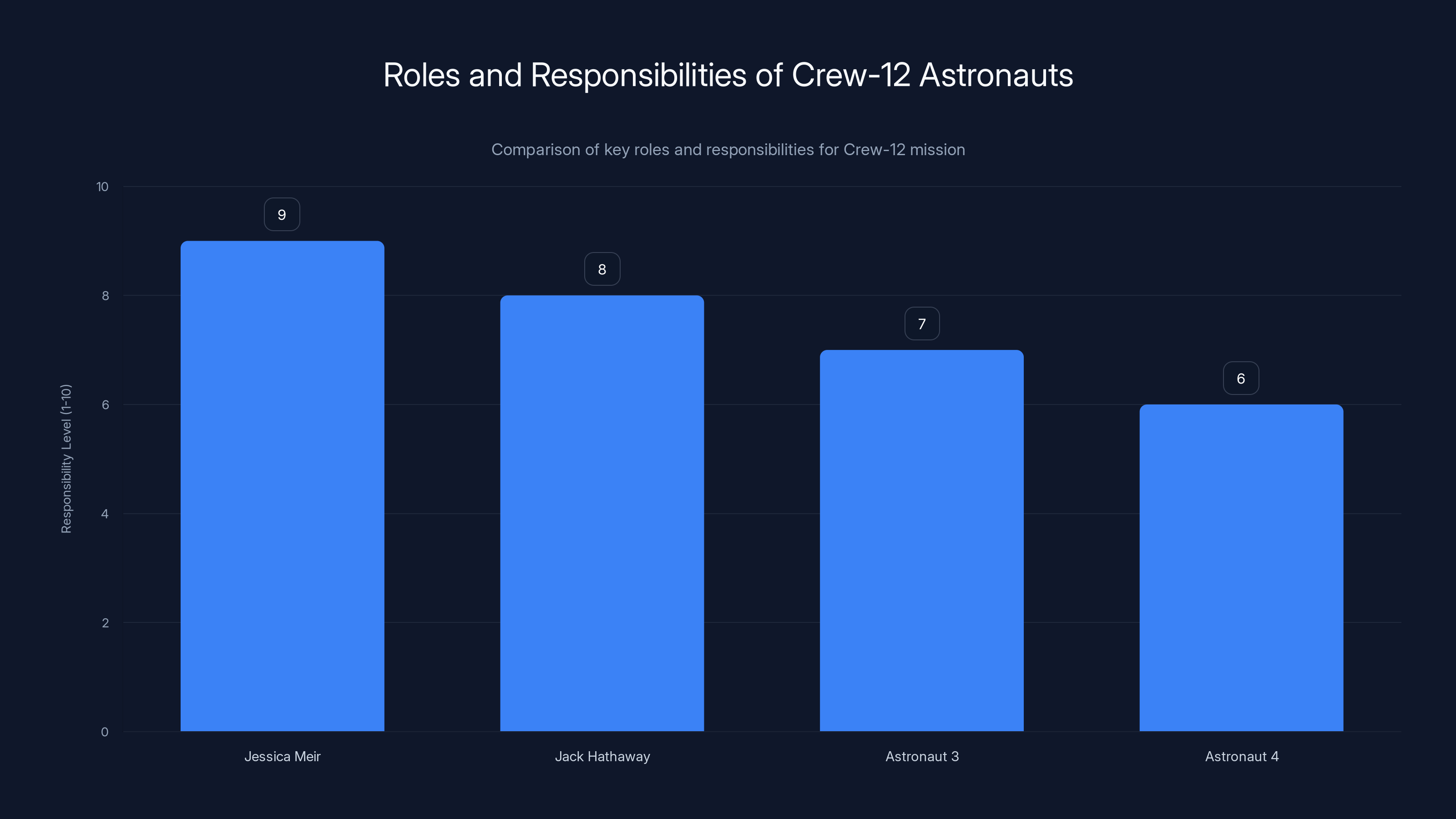

The Four Astronauts of Crew-12

Jessica Meir: NASA's Commander

Jessica Meir sits in the commander's seat for Crew-12, commanding the Dragon capsule and serving as the mission's operational lead. This role carries immense responsibility. The commander is ultimately accountable for every decision made during ascent, orbit, and descent.

Meir isn't new to this. She's a veteran astronaut who previously flew to the ISS on Soyuz MS-15 in September 2019, where she spent six months aboard the station. During that mission, she conducted multiple spacewalks, including one where she and Christina Koch performed maintenance work outside the station. Those experiences trained her for the complexities of commanding Crew-12.

Her background is fascinating. She holds a Ph.D. in marine biology and worked as a research scientist studying Arctic biology before joining NASA. That scientific foundation gives her credibility when evaluating the research agenda aboard the ISS. She understands what the experiments are measuring and why the data matters.

Jack Hathaway: NASA's Pilot

Jack Hathaway serves as pilot, responsible for the spacecraft's systems during all phases of flight. The pilot's role has evolved since the early days of spaceflight, but it remains critical. Hathaway monitors the Dragon's computers, propulsion systems, environmental controls, and abort mechanisms. If anything goes wrong, he's the first to diagnose the problem and implement corrective action.

Hathaway is a former U.S. Air Force test pilot with thousands of hours in high-performance aircraft. That background prepared him for the unique demands of spaceflight. Test pilots understand systems complexity, hardware limitations, and how to make split-second decisions under pressure.

This is Hathaway's first spaceflight. For any astronaut, that first launch is transformative. No amount of simulation can fully prepare you for the acceleration, the vibration, the moment when rocket engines ignite and you're committed to the mission.

Sophie Adenot: European Space Agency Astronaut

Sophie Adenot represents the European Space Agency, bringing France's representation to the ISS rotation. She's a French astronaut and former military helicopter pilot with experience in operations and emergency response.

Adenot's presence on Crew-12 underscores the ISS's international character. Europe contributes essential hardware to the station, including the Columbus laboratory module, and rotates crew members to maintain continuous operations. Adenot's flight represents the ESA's commitment to ISS operations and human spaceflight research.

Her background in aviation gives her the technical foundation necessary for spaceflight operations, but her role also includes conducting European research experiments and contributing to the international crew's day-to-day operations.

Andrey Fedyaev: Roscosmos Cosmonaut

Andrey Fedyaev rounds out the crew as a Roscosmos cosmonaut. Despite geopolitical challenges between the United States and Russia on Earth, cooperation in space continues. Fedyaev's presence on Crew-12 represents the ongoing partnership between NASA and Roscosmos, a relationship that predates modern tensions and persists because both agencies recognize the value of collaboration.

Fedyaev brings operational expertise and represents Roscosmos's commitment to ISS operations. His role includes crewmate responsibilities and contributions to research activities.

The Launch: February 13, 2025

Every successful docking begins with a successful launch. At 5:15 AM Eastern on February 13, Falcon 9's nine Merlin engines ignited, producing 1.7 million pounds of thrust. The rocket cleared the launch pad at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and accelerated toward the stars.

Launch window precision matters enormously. Launch times are calculated months in advance based on the ISS's orbital position and the desired approach trajectory for the Dragon capsule. A launch window typically spans a few hours, but the actual launch must occur within a narrow window of minutes. If conditions aren't met—weather, technical issues, range safety constraints—NASA and SpaceX wait for the next opportunity.

February 13 was clear. The launch proceeded on schedule.

The first stage burn lasted about 2 minutes 45 seconds. During this phase, Falcon 9 accelerated through the densest part of Earth's atmosphere, experiencing maximum aerodynamic stress. At burnout, the first stage separated and the second stage's single Merlin Vacuum engine took over, continuing the acceleration to orbital velocity.

About nine minutes after launch, Crew-12 was in orbit. The four astronauts experienced roughly eight times Earth's gravitational acceleration during their ascent. The physical sensation of launch is profound—acceleration that pins you to your seat, vibration that resonates through your entire body, the sound of powerful engines below. Training prepares them for it intellectually, but the actual experience surpasses any simulation.

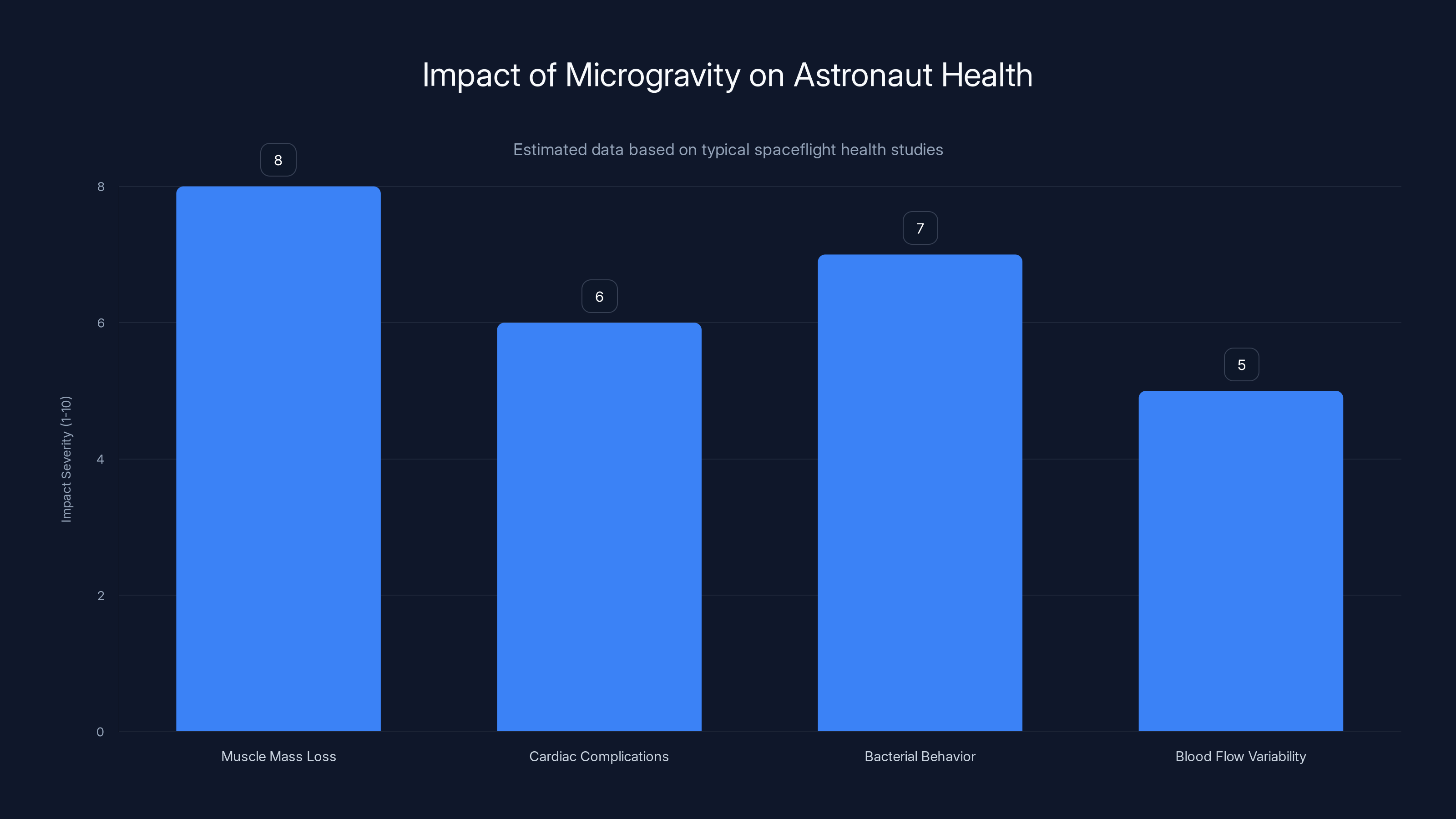

Estimated data suggests muscle mass loss is the most severe impact of microgravity, followed by changes in bacterial behavior and cardiac complications. Understanding these effects is crucial for long-term space missions.

The Journey to ISS: 34 Hours of Orbital Mechanics

Once in orbit, the Crew Dragon wasn't immediately headed to the ISS. That might seem counterintuitive, but modern crewed spacecraft don't use the fast rendezvous profiles of early spaceflight. Instead, they follow a deliberate approach.

Crew-12's Dragon spent approximately 34 hours in orbit before docking with the station. During this time, the capsule performed several orbital adjustments to match the ISS's orbital position and velocity. These maneuvers are calculated with extraordinary precision—the ISS orbits at roughly 17,500 miles per hour, traveling around Earth every 90 minutes. For the Dragon to dock, its velocity and orbital plane must match the station's exactly.

This extended approach timeline serves multiple purposes. It allows ground controllers to verify that all spacecraft systems are functioning normally. It gives the crew time to acclimate to microgravity. And it enables the ISS crew to prepare berthing areas and ensure the station is ready for the incoming vehicle.

During this period, Crew-12 conducted various housekeeping tasks, systems checks, and received briefings from mission control about station conditions and any last-minute adjustments to the approach profile.

The Docking Event: February 14, 2025, 3:15 PM Eastern

On Valentine's Day, Crew-12's Dragon executed its final approach to the International Space Station. The docking window opened at 3:15 PM Eastern, and that's when the critical event occurred.

Docking is simultaneously routine and extraordinarily complex. The Dragon doesn't simply collide gently with the station. Instead, it executes a carefully choreographed sequence of automated maneuvers while maintaining constant communication with ground control and the ISS crew.

The final approach began at a distance of about 250 meters (roughly 820 feet) from the station. From there, the Dragon used relative GPS and vision sensors to guide itself toward the designated docking port. Most of this final sequence is automated—SpaceX's sophisticated guidance systems handle the precision work. However, the crew can intervene at any moment if anomalies develop.

As the Dragon closed distance, relative velocity decreased incrementally. When spacecraft dock, they're moving at roughly 17,500 miles per hour in an absolute reference frame, but relative to each other, they close at just a few feet per second. This controlled slow approach minimizes docking loads and prevents damage.

The ISS has multiple docking ports. Crew-12's Dragon was assigned to a specific port, likely a Harmony module docking adapter. These ports are purpose-built for SpaceX spacecraft, equipped with automated mechanisms that engage when the Dragon makes contact.

When the Dragon's docking ring made contact with the station's adapter, automated capture mechanisms engaged. Latches locked the spacecraft together, and then a series of seals were verified to ensure an airtight connection. The entire sequence took minutes, but each second involved dozens of synchronized actions.

Once docking was confirmed complete and all systems verified, the Dragon crew initiated the hatch opening procedure. This involved pressurizing the tunnel between the two spacecraft, verifying seal integrity, and then physically opening the hatch doors.

At that moment—hatch open, the four Crew-12 members floating through the tunnel and into the ISS—the mission's primary objective was achieved. They were now part of the continuous human presence in space.

The ISS Crew Before Crew-12 Arrived

Crew-12 joined three astronauts already aboard the ISS. These were the final members of Expedition 72, awaiting the new crew's arrival to formally transition to Expedition 73.

The ISS operates on an expedition model. An expedition consists of the resident crew aboard the station at any given time. Expeditions typically overlap between crew rotations. When a new crew arrives, the previous crew remains for a few days to transfer knowledge and conduct joint operations. Then the returning crew departs, leaving the new crew to continue operations.

This overlap period is essential. Incoming crew members get real-time, in-person briefings on station systems, current experiments, and any quirks or workarounds that might not be documented in manuals. The institutional knowledge transferred during handover can't be replicated through training alone.

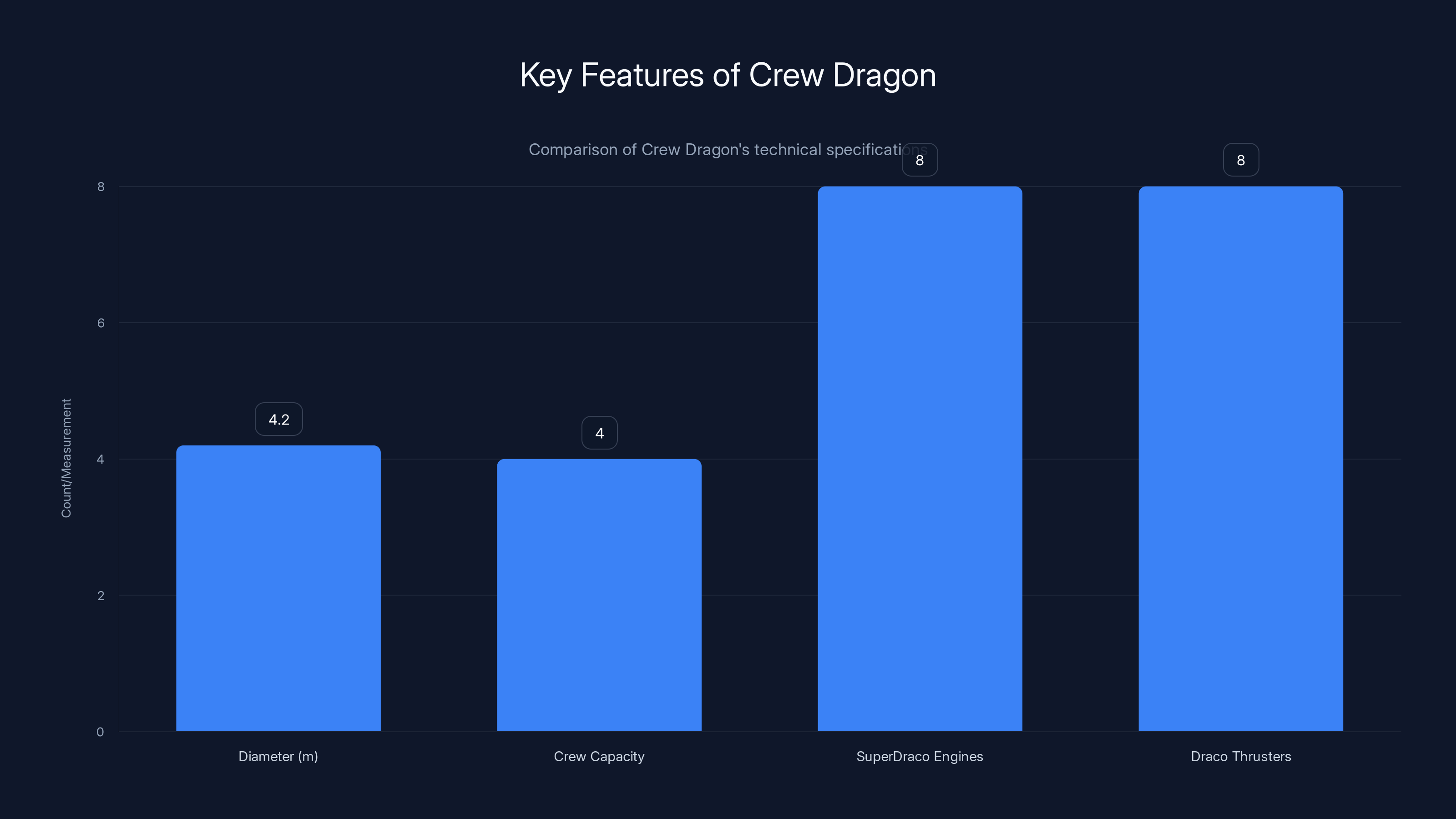

Crew Dragon features a 4.2-meter diameter, seats 4 crew members, and is equipped with 8 SuperDraco engines and 8 Draco thrusters for propulsion.

Mission Duration and Research Timeline

Crew-12 would spend eight months aboard the ISS. That's roughly 240 days—long enough to complete meaningful research programs but not so long that it approaches the limits of human adaptation to microgravity.

Research aboard the ISS is continuous. There's no such thing as "off hours" on the station. Experiments run 24/7, either autonomously or monitored by crew. Crew-12's eight months would be divided between scheduled research activities, routine maintenance, systems checks, emergency preparedness, and personal time.

The research agenda alone justifies the investment in human spaceflight. Unlike robotic missions, the presence of humans allows for adaptive, real-time investigation that robots can't provide.

The Scientific Research Agenda

Human Health and Physiology Studies

One critical area of investigation involves how spaceflight affects human health. This isn't merely academic—NASA plans to send humans to the Moon and Mars, missions that will last far longer than ISS rotations. Understanding how the human body adapts to microgravity is essential.

Crew-12 would investigate how pneumonia-causing bacteria—specifically pathogens like Streptococcus pneumoniae—behave in microgravity. On Earth, gravity affects how cells interact, how bacteria spread, and how immune systems respond. In orbit, gravity's influence vanishes. Studying these pathogens in microgravity reveals mechanisms that might not be apparent on Earth and could lead to better treatments for infectious diseases.

The research also examined potential long-term cardiac complications from bacterial infections. Some infections can trigger endocarditis—inflammation of the heart's inner lining—which can cause lasting damage. Understanding these pathways in a microgravity environment provides insights into infection biology that benefit both astronauts and terrestrial medicine.

Another study examined how physical characteristics affect blood flow during spaceflight. Not all astronauts respond identically to microgravity. Individual factors—body composition, cardiovascular fitness, metabolic factors—influence adaptation. By studying individual variation, researchers can predict who's at higher risk for adverse effects and develop countermeasures.

Technology Development for Deep Space Exploration

Beyond immediate health research, Crew-12 would conduct experiments advancing technologies for lunar and Martian exploration. This includes materials science research, understanding how various materials behave in the space environment, and testing technologies that future deep-space missions will rely upon.

The microgravity environment allows for unique manufacturing processes impossible on Earth. Certain alloys, crystals, and composite materials can be produced more perfectly in orbit than in any terrestrial lab. These aren't theoretical exercises—they produce actual useful materials that could eventually be sold commercially or used in space systems.

Biological Research

The ISS serves as a unique laboratory for biology. Plant growth in microgravity provides insights into how plants sense and respond to their environment. Understanding this could improve agricultural efficiency on Earth and inform strategies for growing food on the Moon and Mars.

Animal research—yes, the ISS hosts living creatures as research subjects—examines development, aging, and cellular processes in a gravity-free environment.

The Previous Crew-11 and the Early Return Decision

Understanding Crew-12's mission requires context about why they arrived when they did. Normally, crew rotations follow a predetermined schedule established months in advance. Crew-11 was supposed to return in late February 2025, but they came home roughly a month earlier.

The reason: one crew member experienced a medical issue that station medical resources couldn't diagnose. The specific nature of the condition wasn't disclosed publicly—astronaut medical records are private—but it was significant enough that NASA made the prudent decision to return the entire crew to Earth for proper evaluation.

This decision exemplified a core principle of human spaceflight: crew safety always overrides schedule convenience. An early return costs money, disrupts station operations, and creates scheduling complications. NASA and SpaceX didn't hesitate.

The returning crew member underwent comprehensive medical evaluation and made a full recovery. The incident demonstrated that even with protocols, training, and preparation, spaceflight remains risky. NASA's willingness to prioritize health over operations reflects its mature approach to human spaceflight risk management.

Jessica Meir, as the commander, holds the highest responsibility level in Crew-12, followed closely by Jack Hathaway as the pilot. Estimated data for other astronauts.

International Cooperation and the ISS Partnership

Crew-12's composition—NASA, ESA, Roscosmos—highlights the ISS's international nature. The station is jointly owned and operated by five space agencies representing 15 nations: NASA, Roscosmos, ESA, JAXA (Japan), and CSA (Canada).

This partnership wasn't inevitable. It emerged from a deliberate Cold War-ending decision to transform space competition into space cooperation. The ISS Treaty, signed in 1988 and implemented through agreements finalized in 1993, created a legal framework for this unprecedented collaboration.

Designing the station required compromises. Russian modules use different docking interfaces than American modules. Communication protocols had to be standardized. Research procedures required compatibility across agencies with different traditions and regulations.

Yet it worked. The station has operated continuously for over 24 years with crews from dozens of nations, each bringing expertise, resources, and commitment.

Crew-12, carrying astronauts from three agencies, embodies this cooperation. When Andrey Fedyaev, Sophie Adenot, Jessica Meir, and Jack Hathaway docked with the ISS on February 14, they weren't just joining a space station. They were participating in humanity's most ambitious shared endeavor.

Space X's Role in Modern Human Spaceflight

Crew-12 wouldn't exist without SpaceX's success. In 2010, Elon Musk's company was six years old, had never launched a crewed vehicle, and was racing to demonstrate that commercial spaceflight was viable.

SpaceX's first crewed mission—Crew Dragon Demo-2 in May 2020—was the turning point. With NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley aboard, the Falcon 9 and Dragon spacecraft proved they could safely transport humans to the ISS and back.

Since then, SpaceX has completed numerous crewed missions under NASA's Commercial Crew Program, becoming the primary vehicle for ISS crew rotations. By 2025, the company had transported more humans to orbit than any other commercial entity and was running crew missions with the frequency and reliability of airline flights.

Crew-12 was SpaceX's 20th crewed human spaceflight mission—a remarkable achievement. Each mission required the same level of precision, preparation, and quality assurance as the first. There's no tolerance for complacency in human spaceflight.

The Technical Specifications of Crew Dragon

Understanding Crew-12 requires understanding the spacecraft carrying them. The Crew Dragon is built on principles established by decades of spaceflight heritage but incorporates 21st-century technology and manufacturing.

The capsule measures roughly 4.2 meters in diameter—a cone-shaped structure topped by a heat shield. Inside, four crew seats are arranged with two forward-facing seats for pilot and commander, two aft-facing seats for additional crew.

The Dragon carries life support systems generating oxygen, managing carbon dioxide, controlling temperature and humidity, and maintaining pressure. These systems are redundant—multiple independent systems ensure crew survival even if primary systems fail.

Propulsion comes from a combination of Super Draco engines for abort scenarios and eight Draco thrusters for orbital maneuvering. The Falcon 9 first stage provides ascent power; the Dragon's systems take over once in orbit.

The spacecraft is designed for crew comfort relative to other spacecraft, but spaceflight remains physically demanding. The acceleration of launch and descent impose stress on the human body. The ride is bumpy, loud, and intense.

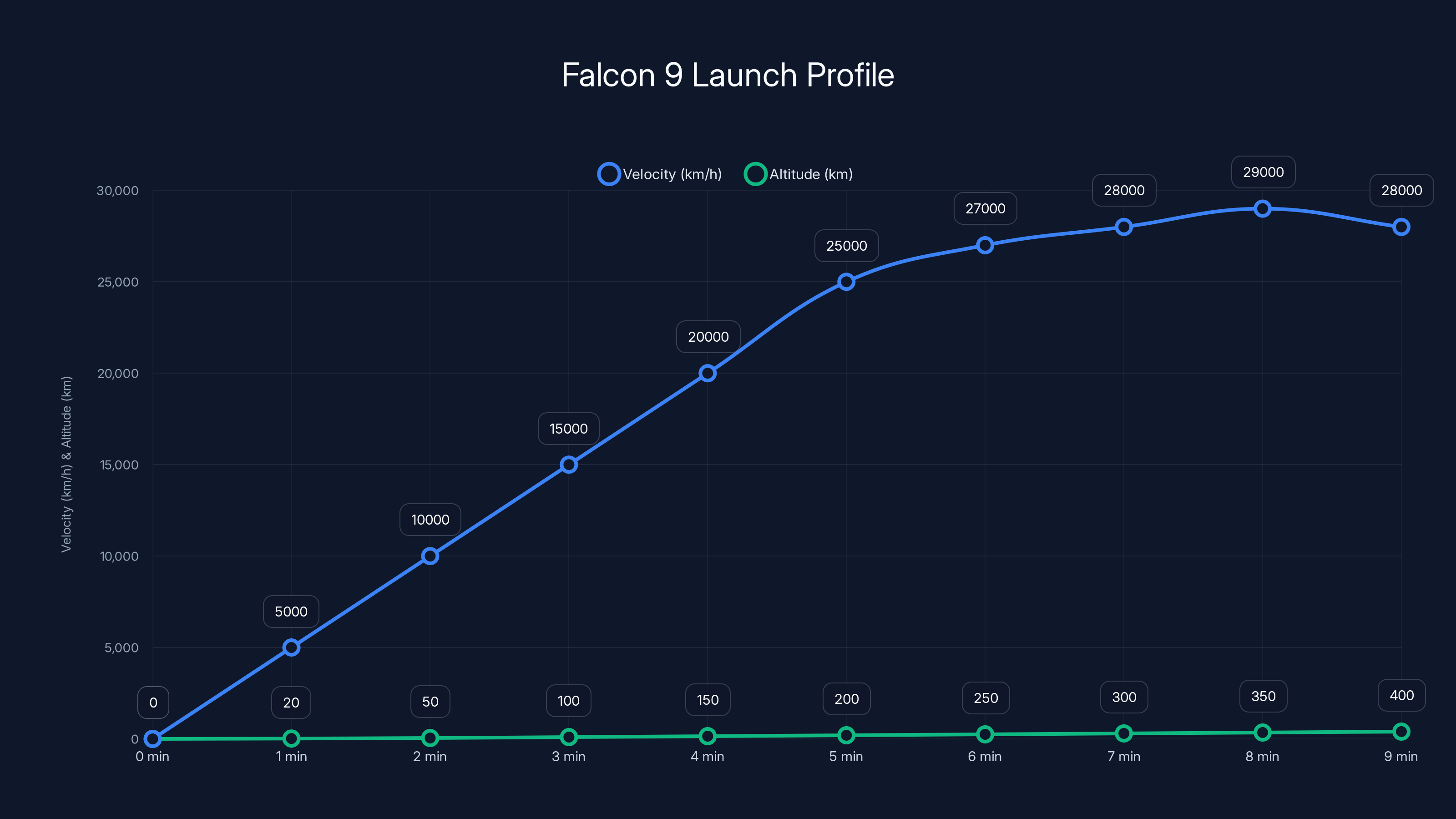

The Falcon 9 launch on February 13, 2025, saw the rocket reach orbital velocity in approximately 9 minutes, with altitude and velocity peaking before stabilizing as it entered orbit. Estimated data.

Watching the Docking: How to Follow the Live Coverage

NASA provided live coverage beginning at 1:15 PM Eastern on February 14, well before the 3:15 PM docking. The broadcast featured mission control commentary, views from the Dragon's external cameras, and perspective from the ISS.

Watching a docking event offers unique perspective on spaceflight. You see two spacecraft moving at 17,500 miles per hour, yet from their own perspectives, approaching at a few feet per second. You hear mission control engineers tracking every system, the tension in their voices as the final approach unfolds. You witness the moment of capture—the subtle indication that latches engaged and two vehicles became one.

These broadcasts democratize spaceflight. Millions of people who'll never ride a rocket can still experience the intensity of these operations. That accessibility matters for maintaining public engagement with space exploration.

Post-Docking Operations and Crew Handover

Once Crew-12 boarded the station, the work of transition began. The first priority is safety—verifying that both the Dragon and ISS systems remained functional after docking. Any anomalies detected during this verification period would be addressed immediately.

The crew then began unpacking cargo. The Dragon carries supplies, experiments, and equipment along with the crew. Several hundred kilograms of gear would be transferred to station storage.

In the days following docking, Crew-11 would conduct detailed handover briefings with Crew-12. This includes system status, procedures unique to each module, current research status, and any issues requiring attention. This transfer of institutional knowledge is irreplaceable.

After roughly a week of overlap, Crew-11 would depart for Earth. They'd board the Dragon, undock from the ISS, and ride the spacecraft back to the atmosphere. Re-entry is its own adventure—intense heating as the capsule plunges through the thermosphere, parachute deployment, and eventual splashdown in the ocean where recovery ships waited.

The Eight-Month Mission Ahead

With Crew-11 departed, Crew-12 would assume full control of station operations. Their eight months would follow a rhythm: research activities in the morning, maintenance and systems checks in the afternoon, exercise and personal time in the evening. That's simplified—the actual schedule is far more complex, but the general rhythm holds.

Crew-12's timeline would include milestones. Cargo vehicles would arrive with supplies and experiments. Extravehicular activities—spacewalks—might be conducted if repairs or maintenance required external work. Other crew rotations would follow, potentially bringing new faces to the station or swapping crew members.

By late August or early September 2025, Crew-12's mission would conclude. They'd depart on a Dragon capsule, leaving the station to the next rotation. The ISS would continue, its human presence uninterrupted.

The Significance of Continuous Human Presence

Why maintain humans in space? What justifies the expense, risk, and complexity?

The answers are scientific, technological, and philosophical. The ISS conducts research impossible on Earth. Certain manufacturing processes, biological studies, and materials science requires the microgravity environment. That research has practical applications benefiting people on Earth.

Beyond research, the ISS serves as a test bed for technologies essential for deeper space exploration. Human missions to the Moon and Mars require life support systems, radiation protection, landing vehicles, and return systems. Many of these technologies are tested aboard the ISS before commitment to deep space missions.

There's also a philosophical dimension. Humans have always explored beyond their immediate reach. The ISS represents that impulse extended to space. Maintaining continuous human presence in orbit demonstrates that exploration beyond Earth isn't impossible. It's achievable, it's sustainable, and it builds knowledge for future generations.

Crew-12 embodied all these purposes. Four humans launched by private industry, funded by government agencies, working aboard an international facility, conducting research that would benefit humanity—it's a story worth paying attention to.

Future Crew Rotations and the Trajectory of ISS Operations

Crew-12 was one rotation in an ongoing series. NASA and SpaceX had planned multiple additional crew missions extending years into the future. The ISS's operational lifespan, originally planned to end in 2015, had been extended repeatedly. As of 2025, operations were planned through at least 2030, possibly longer.

Each crew rotation follows similar patterns, yet each carries unique research objectives and team dynamics. The ISS's extended lifetime meant that human spaceflight had transitioned from an occasional special event to routine operations. Not routine in the sense of boring—every launch and docking demands full attention and preparation—but routine in the sense of established, regularized, predictable operations.

This transition matters. Routine human spaceflight is a prerequisite for deeper space exploration. Before humans return to the Moon or land on Mars, we need to demonstrate reliable, safe human spaceflight operations in Earth orbit. Crew-12, Crew-13, and subsequent crews would provide that demonstration.

Conclusion: The Continuing Story of Human Spaceflight

When Crew-12's Dragon docked with the ISS on February 14, 2025, it marked another chapter in the remarkable story of human spaceflight. Four people—Jessica Meir, Jack Hathaway, Sophie Adenot, and Andrey Fedyaev—boarded the station and became part of something larger than themselves.

They became residents of humanity's outpost in space. They would conduct research advancing medicine and technology. They would troubleshoot problems, maintain systems, and manage emergencies. They would live, work, and exist in an environment that 99.9999% of all humans who've ever lived never experienced.

But the significance of Crew-12 extends beyond those four individuals. Their mission represented continued commitment to human spaceflight, international cooperation, and the belief that space exploration benefits humanity. It demonstrated that private industry, working alongside government agencies, could sustain routine operations in the realm once reserved for superpowers with unlimited budgets.

SpaceX's success with Crew Dragon transformed human spaceflight from an occasional event requiring years of preparation to a regular routine. This normalization of spaceflight—making it achievable, affordable, and reliable—is essential for humanity's future beyond Earth.

Crew-12's eight-month mission would unfold over the following months, largely out of public view. The daily work of science, maintenance, and operations would continue with minimal fanfare. But that unglamorous work is the foundation of exploration.

When you think of Crew-12, remember that docking event—two spacecraft moving at tremendous velocity in perfect synchronization, thousands of engineers and scientists supporting from Earth, systems working as designed, and humans crossing the boundary between Earth and space. That moment represented decades of learning, billions of dollars invested, and thousands of people dedicated to one goal: maintaining human presence in space.

That's worth watching. That's worth understanding. And that's the foundation of everything humanity will do in space in the years to come.

FAQ

What is Crew-12 and when did it launch?

Crew-12 is NASA's 12th operational crew rotation to the International Space Station under the Commercial Crew Program. The mission launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on February 13, 2025, at 5:15 AM Eastern from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. The Crew Dragon spacecraft docked with the ISS on February 14, 2025, at 3:15 PM Eastern.

Who are the astronauts on Crew-12?

Crew-12 consists of four space professionals: Jessica Meir (NASA Commander), Jack Hathaway (NASA Pilot), Sophie Adenot (European Space Agency), and Andrey Fedyaev (Roscosmos). Meir is a veteran astronaut with previous ISS experience and a Ph.D. in marine biology. Hathaway is a former Air Force test pilot on his first spaceflight. Adenot is a French astronaut and military helicopter pilot. Fedyaev is a Roscosmos cosmonaut contributing to the international crew.

How long will Crew-12 stay on the ISS?

Crew-12 was scheduled to remain aboard the International Space Station for eight months, approximately 240 days. During this time, they would conduct scientific research, maintain station systems, perform exercise to counteract microgravity effects, and contribute to station operations alongside other crew members during the overlap period with the departing Crew-11.

What research will Crew-12 conduct?

Crew-12's research agenda includes multiple areas: studying how pneumonia-causing bacteria behave in microgravity and their potential for causing long-term heart damage, investigating how physical characteristics affect blood flow during spaceflight, developing technologies for lunar and Martian exploration, conducting materials science experiments, and biological research including plant growth studies. The research has applications both for astronaut health and for advancing terrestrial medicine.

Why did Crew-11 return early?

Crew-11 returned to Earth approximately one month earlier than scheduled because one crew member experienced a medical condition that the ISS medical facilities couldn't adequately diagnose. The specific nature of the condition wasn't publicly disclosed, but it was serious enough that NASA made the decision to prioritize crew health and medical evaluation over maintaining the planned schedule. The returning crew member made a full recovery.

How does SpaceX's Crew Dragon differ from previous spacecraft?

The Crew Dragon is designed as a modern, reusable spacecraft incorporating decades of spaceflight heritage with contemporary technology. It features automated docking systems, redundant life support, touchscreen controls replacing mechanical switches, and is designed for crew comfort relative to historical spacecraft. Unlike single-use capsules, the Dragon can be refurbished and reflown multiple times, reducing costs and enabling more frequent missions. The spacecraft's design incorporates safety enhancements including the Super Draco abort engines.

What is the significance of international crew composition?

Crew-12's composition with astronauts from NASA, the European Space Agency, and Roscosmos exemplifies the ISS's international partnership. The station is jointly owned and operated by five space agencies representing 15 nations. This cooperation transformed space competition into collaboration, with crew members from different countries working together despite geopolitical differences on Earth. This international approach strengthens the ISS program and demonstrates that space exploration benefits from shared resources and expertise.

How does crew rotation work at the ISS?

Crew rotation follows an expedition model where incoming crews overlap with departing crews for several days. This overlap allows for detailed knowledge transfer about station systems, current research status, and operational procedures. The departing crew then departs aboard a Crew Dragon spacecraft while the new crew assumes full control of station operations. This handover process is critical for maintaining continuity and institutional knowledge aboard the station.

What makes the docking procedure so critical?

Docking is among the most complex and risky procedures in spaceflight. The spacecraft must approach at the ISS's orbital velocity of approximately 17,500 miles per hour while maintaining precise alignment and relative velocity of just a few feet per second. The procedure requires sophisticated guidance systems, constant communication between Dragon and ISS, and crew readiness to intervene if anomalies develop. Successful docking requires coordination of multiple independent systems and represents the culmination of months of mission planning and preparation.

How can I watch ISS passes and follow Crew-12 activities?

NASA provides multiple resources for following ISS operations: the Spot the Station tool (available on NASA's website) notifies you when the ISS will pass over your location as a bright moving point visible to the naked eye. NASA Television broadcasts major mission events including crew launches, docking operations, and emergency procedures. ISS Update podcasts and social media provide regular mission information. The ISS national laboratory website offers detailed information about research being conducted aboard the station.

Key Takeaways

- Crew-12 launched February 13, 2025, carrying four astronauts: Jessica Meir (NASA), Jack Hathaway (NASA), Sophie Adenot (ESA), and Andrey Fedyaev (Roscosmos)

- Dragon docked with ISS February 14 at 3:15 PM after 34-hour orbital approach, completing SpaceX's 20th crewed human spaceflight mission

- Eight-month mission research agenda includes studying microgravity effects on bacterial pathogens, cardiovascular health, and technology development for lunar/Martian exploration

- Crew-12 exemplifies international space cooperation with representation from three space agencies and demonstrates SpaceX's role in sustaining routine human spaceflight

- Mission represented continuation of unbroken human presence on ISS since 2000, essential foundation for future deep-space exploration

Related Articles

- NASA Crew-12 Mission to ISS: Everything About February 11 Launch [2025]

- SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Take Smartphones to Space [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

- Bezos vs Musk: The Race Back to the Moon [2025]

- SpaceX Super Heavy Booster Cryoproof Testing Explained [2025]

![NASA SpaceX Crew-12 ISS Docking: Complete Mission Guide [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-spacex-crew-12-iss-docking-complete-mission-guide-2025/image-1-1771094273627.jpg)