Neil Young Takes Historic Stand: Music Donation, Political Activism, and the Amazon Boycott

Neil Young isn't your typical rock star content to fade quietly into the background. At an age when most musicians are focused on legacy tours and streaming royalties, the Canadian-American legend made headlines by doing something nobody saw coming—he donated his entire music catalog to Greenland absolutely free and doubled down on his refusal to let his work be sold through Amazon as long as it's owned by Jeff Bezos. According to Stereoboard, this move underscores Young's commitment to his principles over profits.

Yes, you read that right. We're talking about one of rock music's most iconic figures giving away decades of creative work to a territory most people couldn't point to on a map, while simultaneously taking a swipe at one of the world's richest men. It's the kind of move that says everything about Young's character—the guy doesn't care about playing it safe or maximizing profit margins. He cares about making a statement, as highlighted by Rolling Stone.

This isn't some random publicity stunt either. Young has been consistent in his activism for years, whether it's environmental causes, indigenous rights, or his well-documented criticisms of tech billionaires. But this particular move is bold, unconventional, and raises some fascinating questions about music rights, artistic control, and what it actually means to have the freedom to distribute your own work. As noted by Next Avenue, Young's actions are a testament to his lifelong commitment to activism.

The Greenland donation is particularly intriguing because it's not a typical charitable move. Greenland isn't exactly a market where Young was going to sell millions of albums anyway. So what's the real story here? What's Young's endgame? And what does his Amazon boycott actually mean for his fans, his legacy, and the future of artist autonomy in the streaming era?

Let's dig into the full context of this decision, examine what it means for music artists, and understand why a rock legend in his late seventies decided that controlling his artistic narrative was more important than maximizing his income stream.

TL; DR

- Neil Young donated his entire music catalog to Greenland for free, making it accessible to residents at no cost, as reported by Noise11.

- He refuses to sell music on Amazon, declaring it will never be available there while Jeff Bezos owns the company, according to Stereogum.

- This move reflects Young's long history of artistic activism and his commitment to controlling his own work, as noted by Mojo.

- The decision raises important questions about artist rights and streaming economics in the modern music industry, as discussed by Bloomberg.

- Young's stance illustrates the growing tension between mega-corporations and independent artists who want ownership of their creative output, as analyzed by The Street.

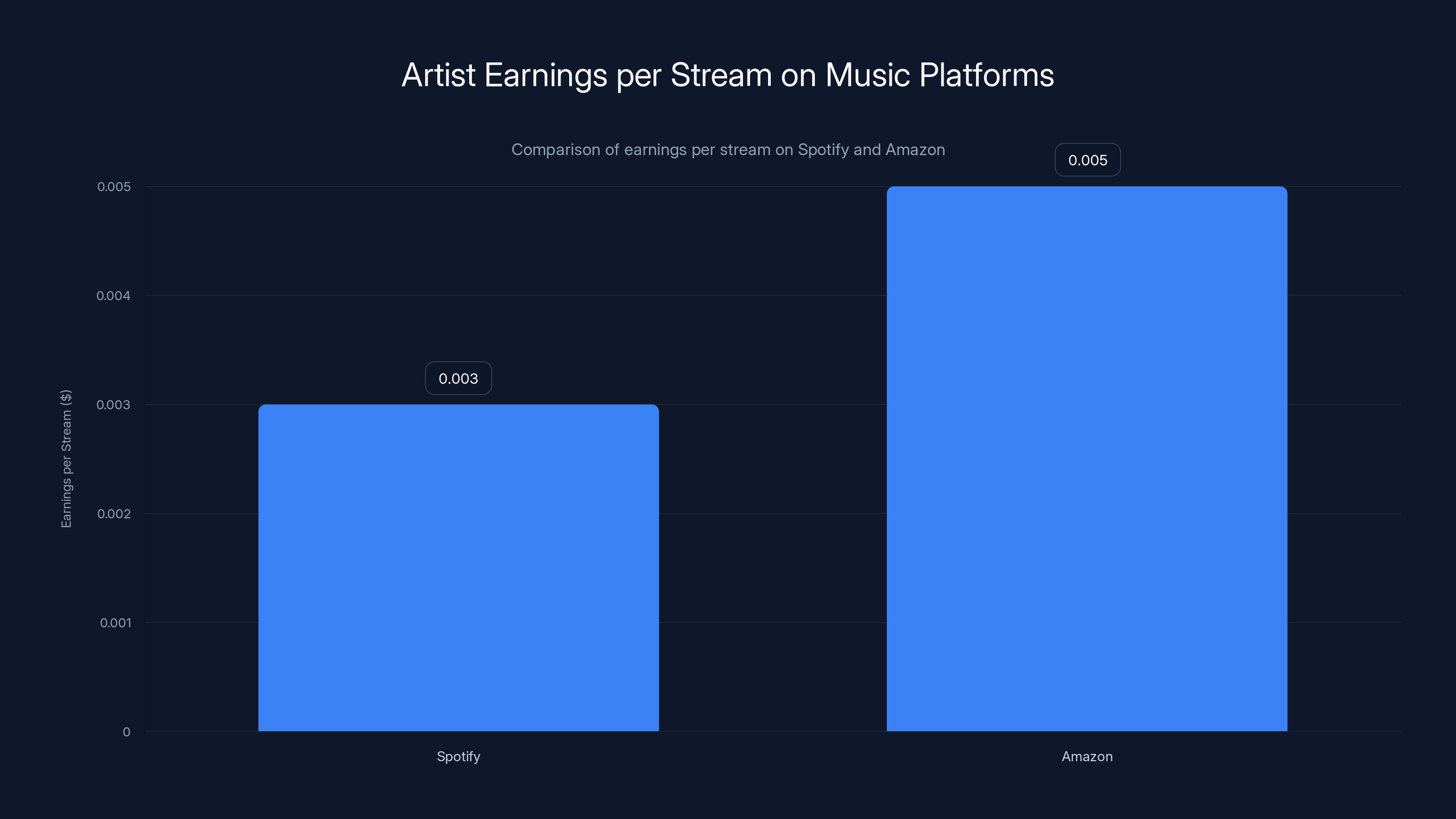

Artists earn between

Understanding Neil Young's Legacy and Activism

Neil Young didn't wake up one day and decide to make waves. His entire career has been built on defying expectations, challenging authority, and refusing to compromise his artistic vision for commercial gain. As Britannica notes, Young's influence spans multiple decades and genres.

Young's career spans over six decades. We're talking about the guy who played at Woodstock, who was part of Buffalo Springfield, who went solo and created some of the most influential albums in rock history. Albums like "Harvest," "Rust Never Sleeps," and "After the Gold Rush" aren't just commercially successful—they're culturally significant. They've shaped how people think about folk-rock, country-rock, and electric rock music.

But Young has never been solely focused on making hit records. He's been an environmental activist, having written songs critical of fossil fuels decades before climate change became mainstream conversation. He's advocated for indigenous rights, spoken out against corporate consolidation, and consistently used his platform to challenge the status quo.

What's particularly interesting is Young's relationship with technology and big tech companies. He's been vocal about audio quality in streaming services, complaining that compressed audio formats are destroying music's integrity. He's criticized how streaming platforms compensate artists. And he's generally maintained an adversarial relationship with the idea that tech billionaires should control the distribution of creative work.

This context is crucial because it helps explain why Young would make such an unconventional decision. For Young, this isn't about money or market strategy. It's about principle.

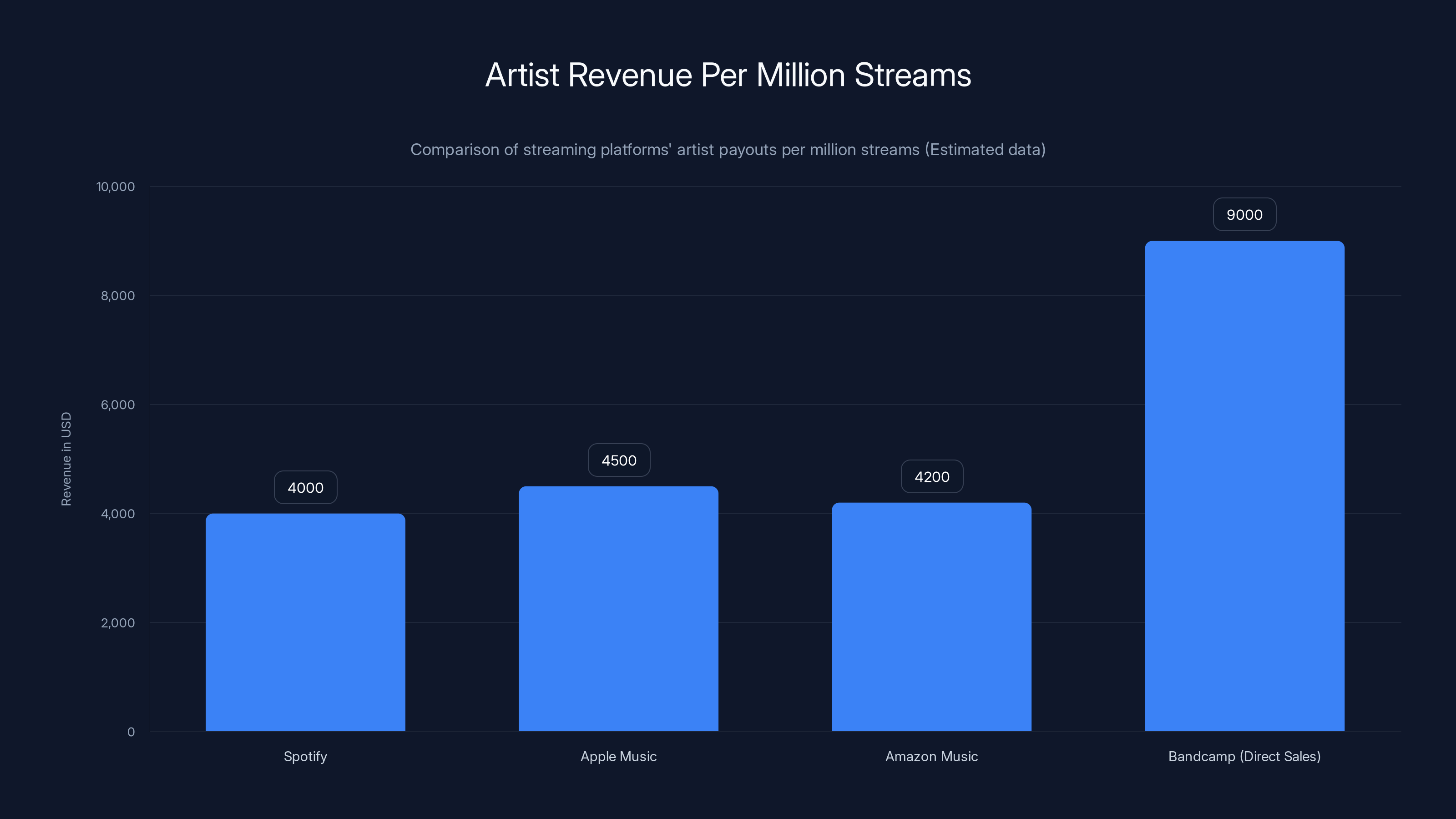

Artists earn significantly more per listener through direct sales platforms like Bandcamp compared to streaming services like Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music. Estimated data based on typical payouts.

The Greenland Music Donation: What Actually Happened

So let's break down what Young actually did. He announced that his entire music catalog—every song, every album, every recording—would be made available to residents of Greenland completely free of charge. As reported by Noise11, this was a gesture of peace and love.

Now, Greenland is an autonomous territory of Denmark with a population of roughly 57,000 people. It's not exactly the target market for major music releases. But that's precisely the point. Young wasn't looking for a commercial return on this investment. He was making a symbolic gesture.

The donation effectively means that anyone living in Greenland can listen to Young's complete discography without paying subscription fees, without ads interrupting their listening experience, without any intermediary taking a cut. It's full access to music that normally costs money.

Why Greenland specifically? Young has been increasingly focused on environmental issues and indigenous rights. Greenland is dealing with some of the most direct impacts of climate change, with melting ice sheets threatening the entire region. By making his music available to Greenland's residents for free, Young was essentially making a statement about where his values lie.

It's also worth noting that this move puts Greenland in an interesting position. The territory now has unique access to Neil Young's music that citizens of the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and other developed nations don't have—unless they pay for it. That inversion of typical music distribution is almost certainly intentional.

The Amazon Boycott: Why Young Won't License His Music There

Now comes the part that really grabbed headlines: Young's declaration that his music will never be available on Amazon Music (or any Amazon-owned platform) as long as Jeff Bezos owns the company. This bold stance was highlighted by Stereoboard.

This isn't Young's first rodeo with taking strong stances against streaming platforms. He's previously pulled his music from Spotify, complaining about the company's compensation model and its association with podcasters Young disagreed with. But the Amazon move is different because it's tied directly to his personal objection to Jeff Bezos.

Young has been vocal about his concerns regarding billionaire wealth concentration, corporate consolidation, and the way tech companies have come to dominate multiple industries simultaneously. Amazon, in particular, is a company that's involved in e-commerce, cloud computing, streaming services, smart home devices, and numerous other sectors. Young sees this consolidation as problematic.

His specific complaint about Bezos centers on concerns about monopolistic practices, labor issues at Amazon warehouses, and the general concentration of power in the hands of a single individual. Young has made it clear that he doesn't want to contribute to Amazon's streaming service as long as Bezos is in control.

What's significant here is that Young actually has the leverage to make this demand stick. He's not some struggling artist who can be ignored—he's Neil Young. His music is valuable intellectual property. His refusal to license his catalog to Amazon actually matters to the platform.

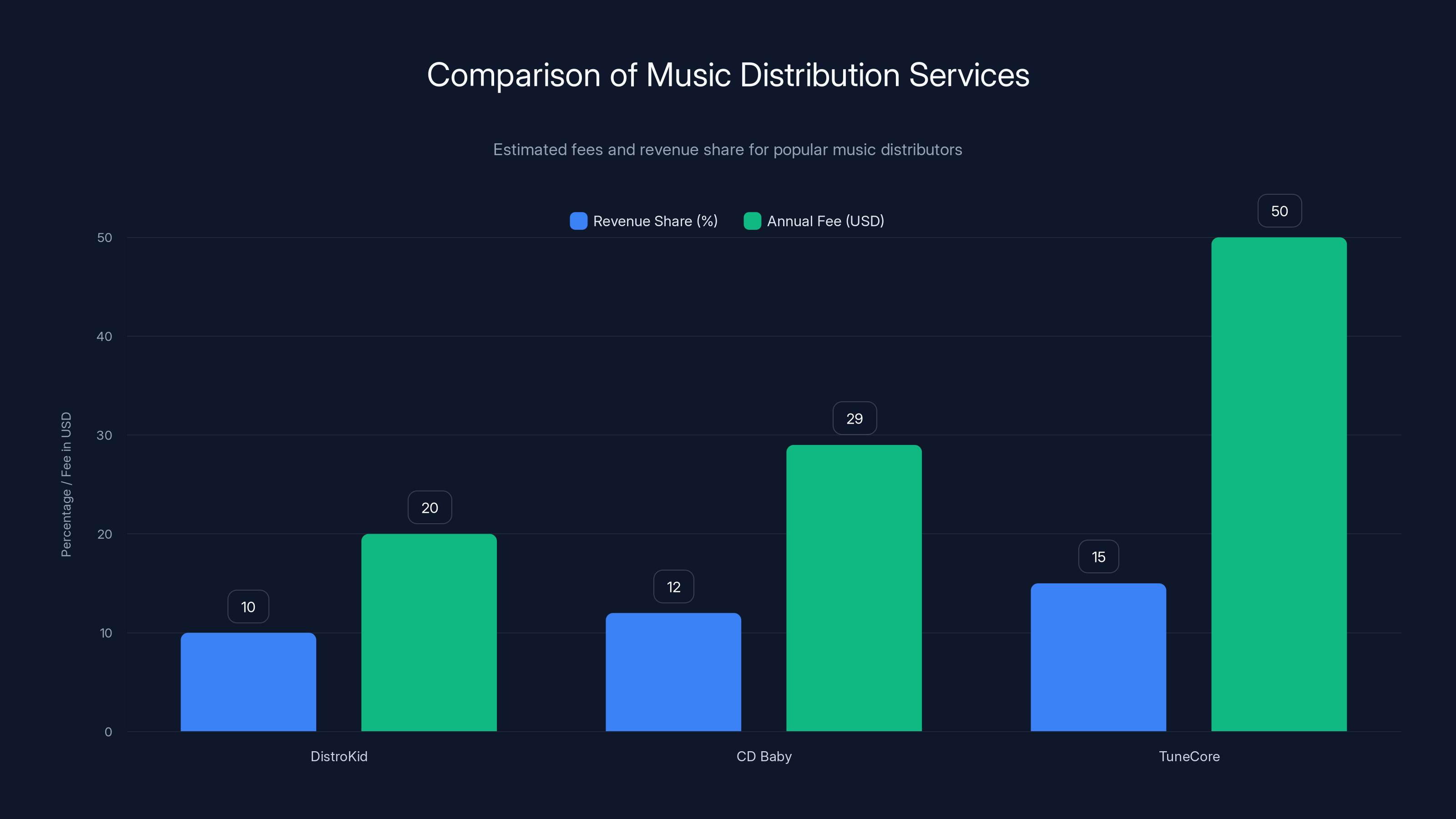

Estimated data shows that while DistroKid offers a lower annual fee, TuneCore has a higher revenue share percentage. CD Baby balances between fee and revenue share.

The Broader Context: Artist Rights in the Streaming Era

Young's moves need to be understood against the backdrop of ongoing tensions between artists and streaming platforms.

For decades, the music industry operated on a model where artists signed to record labels, the labels controlled distribution, and artists received royalties. It wasn't a perfect system, but it was predictable. Artists knew where their music would be sold and roughly how much they'd earn from each sale.

Streaming has fundamentally changed that dynamic. On platforms like Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music, artists earn fractions of a cent per stream. A song needs to be played thousands of times to generate meaningful revenue. And the algorithms that determine which songs get recommended—which essentially determines how much exposure and therefore how many streams you get—are controlled by the platforms themselves.

For major artists like Young with large back catalogs, this creates an interesting situation. They have negotiating power. They can say "you want my music on your platform? Here are my conditions." Smaller artists don't have that luxury.

Young has essentially chosen to use his negotiating power to make statements about his values rather than maximize his streaming revenue. He's saying: "I'd rather not be on Amazon than support Bezos's business. I'd rather give my music away to Greenland than compromise on the principle of artistic control."

This raises a crucial question: How many other artists would like to do the same if they had Young's level of leverage? How many artists are frustrated with how Spotify, Apple, and Amazon conduct business but feel they have no choice but to license their work there because that's where the listeners are?

Music Distribution Rights: The Legal and Technical Framework

To understand why Young can actually make these decisions and enforce them, you need to understand how music rights work.

When you write and record a song, you automatically own the copyright. You don't need to register it or do anything formal—the copyright exists the moment the work is fixed in a tangible medium (like a recording). This is true for Neil Young just as it's true for any independent artist.

However, most successful artists in the past signed their rights away to record labels. The label owned the master recordings, owned the copyright, and controlled where and how the music was distributed. In exchange, the label funded studio time, marketing, and distribution.

Young has been somewhat unusual in that he's retained ownership of much of his back catalog. He owns the master recordings, which means he has the legal right to decide where those recordings are sold and under what terms.

When streaming services like Amazon Music want to carry music, they need a license from whoever owns the copyright. If Young owns the copyright, Amazon has to negotiate with Young directly. Young can set whatever terms he wants—or refuse to license at all.

This is different from, say, an artist signed to Universal Music Group. Universal owns those master recordings, so Universal negotiates with Amazon on the artist's behalf, and the artist gets whatever percentage Universal decides to pay them.

Young's ownership of his own recordings gives him something that most artists don't have: control. And he's using that control to align his distribution with his values.

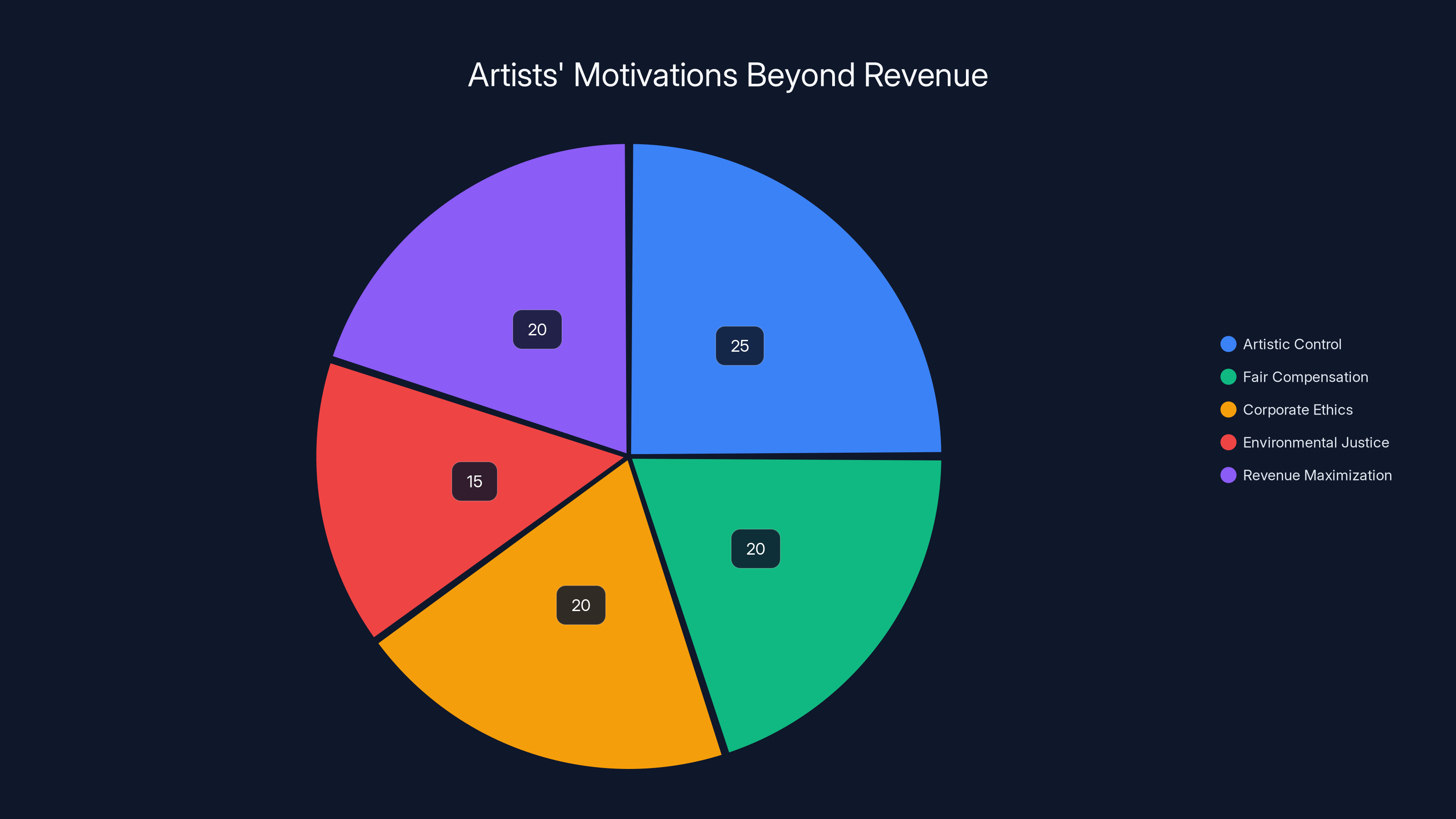

Estimated data suggests that while revenue maximization is important, factors like artistic control and ethics also significantly influence artists' decisions.

Why the Greenland Decision Makes Strategic Sense

On the surface, giving away your music to an island of 57,000 people might sound irrational. But there's actually a clever strategic element to Young's decision.

First, Greenland has become increasingly important in discussions about climate change, resource extraction, and geopolitics. Giving his music to Greenland aligns Young with a territory that's dealing with existential climate challenges. It's a way of putting his creative work at the service of a community facing environmental crisis.

Second, it's a precedent-setting move. By offering his entire catalog to one region for free, Young demonstrates that he's willing to distribute his music based on values rather than profit. This undermines the assumption that artists are solely motivated by revenue. It challenges the narrative that streaming services need to offer the lowest possible payouts because that's all artists will accept.

Third, it creates a conversation. By donating to Greenland specifically, Young has generated global media attention. More people are talking about his values and his stance against corporate consolidation than would be the case if he'd simply raised his streaming rates by a few percentage points.

In terms of actual revenue impact, Greenland represents a negligible portion of Young's potential music sales. But the symbolic value is enormous.

The Amazon Boycott in Context: Corporate Consolidation Concerns

Young's refusal to license his music to Amazon isn't just about Jeff Bezos as a person—though Young clearly has issues with Bezos. It's about what Amazon represents: a company that has become dominant across multiple industries and wields enormous economic and cultural power.

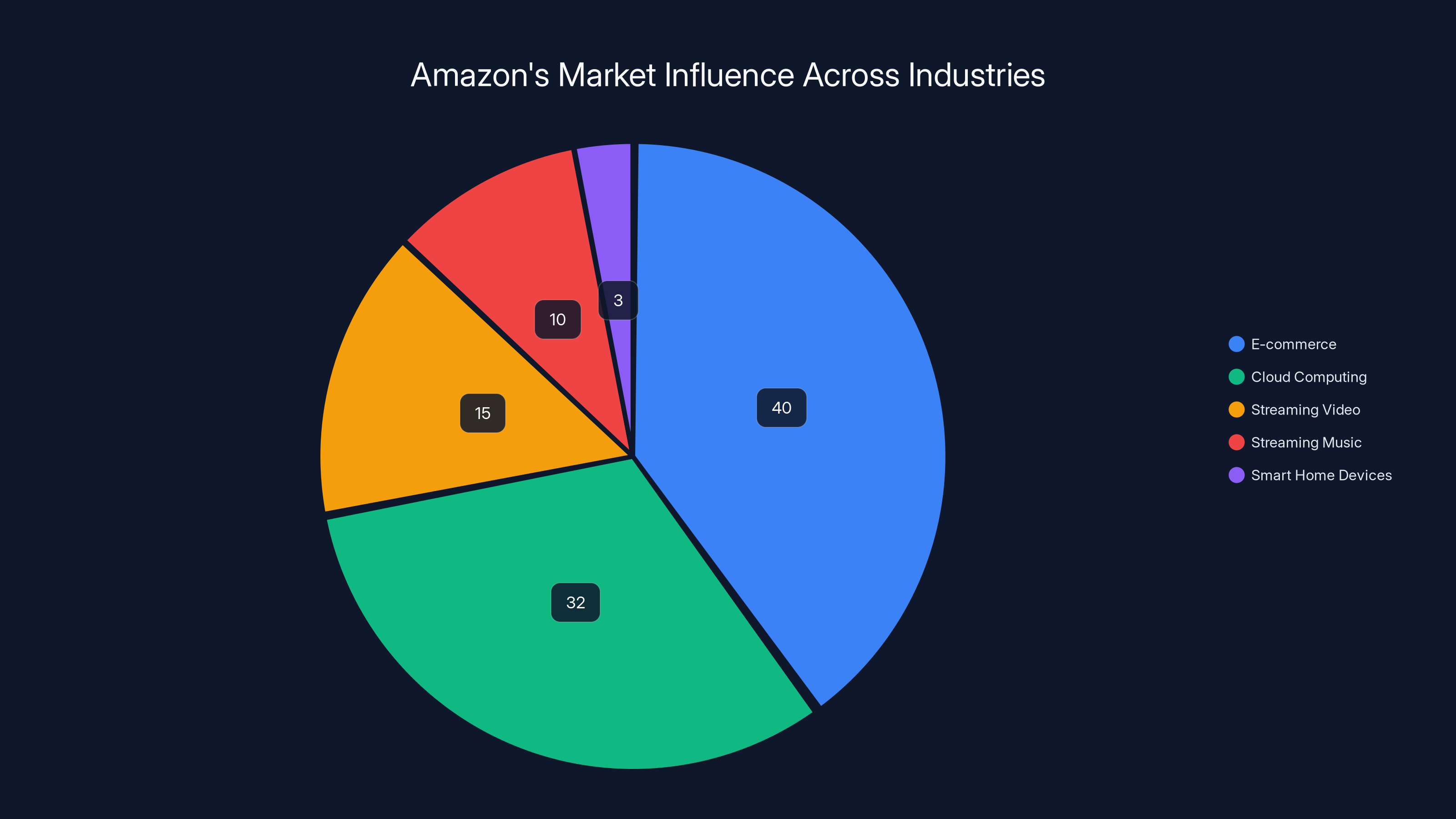

Consider what Amazon controls: e-commerce (where a massive percentage of retail sales happen), cloud computing (where much of the internet's infrastructure runs), streaming video (competing with Netflix and others), streaming music (competing with Spotify and Apple), smart home devices, and numerous other sectors.

For artists and creators, this consolidation is problematic because it means Amazon can dictate terms. Artists need their music on Amazon Music because that's where millions of listeners are. That gives Amazon leverage in negotiating licensing fees. Amazon can offer lower and lower per-stream payouts, and artists have limited ability to refuse because they need the exposure and revenue.

Young is essentially saying: "I have enough financial security and enough of a back catalog that I can afford to not be on Amazon. And I'm choosing not to be, as a matter of principle." That's a statement that most artists simply cannot make.

It also puts pressure on Amazon. If other artists with significant back catalogs started doing the same thing—refusing to license their music until Amazon offered better terms or changed its policies—Amazon would have to respond. Right now, Young is an outlier, but he's demonstrating what's theoretically possible if artists actually had the leverage to demand better treatment.

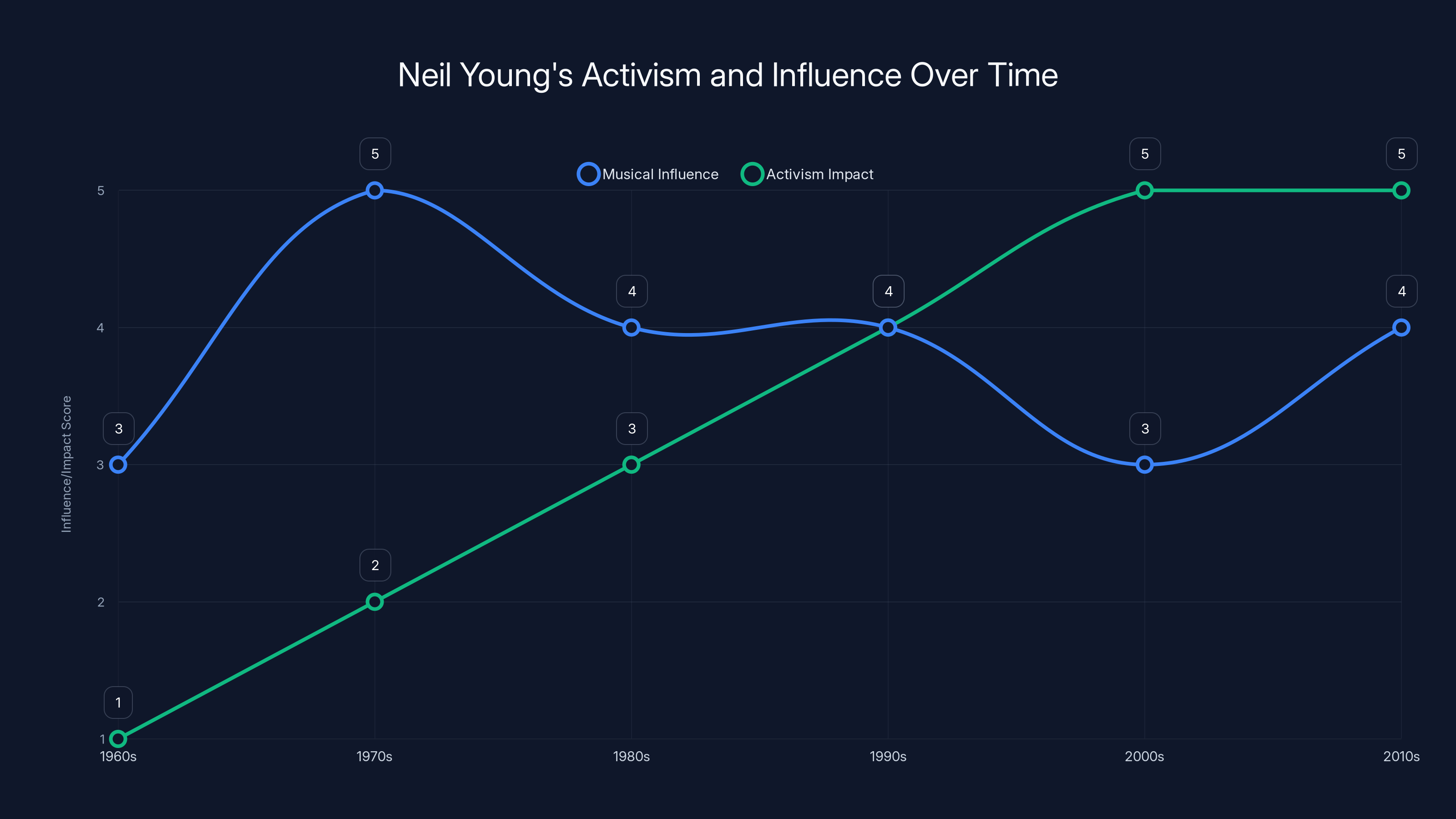

Neil Young's influence in music peaked in the 1970s, while his activism impact has grown significantly, especially in the 2000s and 2010s. (Estimated data)

The Streaming Wars: Why Artist Compensation Matters

Underlying all of this is a fundamental issue in the music industry: artists make very little money from streaming.

Spotify, which dominates the streaming space, generates revenue from advertising and subscription fees. The company then distributes somewhere between 60-70% of its revenue to rights holders (record labels, publishing companies, and artists). The actual amount any individual artist receives depends on their share of streams.

Here's the math: if you get one million streams on Spotify, you earn somewhere between

Compare that to the old model. In the 1990s and 2000s, if you sold a million albums at even

Amazon Music, Apple Music, and other platforms operate on similar models to Spotify. So Young's refusal to be on Amazon is, in part, a refusal to participate in a system where artists are systematically underpaid for their work.

By offering his music to Greenland for free, Young is at least being honest about the transaction: these residents get access to his music in exchange for nothing. That's clearer and more direct than the Spotify model, which pretends to be paying artists while actually generating less revenue per listener than almost any other distribution method in music history.

Precedent: Young's History of Distribution Control

This isn't the first time Neil Young has made unconventional decisions about where and how his music is distributed.

Back in 2014, Young launched Pono, a high-fidelity music service designed to distribute music in lossless format—essentially music without the compression that Spotify and other streaming services use. Young's argument was that compressed audio formats sacrifice sound quality for convenience, and he wanted to offer an alternative where people could hear music exactly as he intended it.

Pono was met with skepticism from the industry, and it eventually faded away. The market simply wasn't ready for lossless streaming, and the infrastructure to support it wasn't in place. But the effort demonstrated Young's willingness to go against the grain of the industry if he believed it was the right thing to do.

Young has also previously pulled his music from Spotify, complaining about the company's low payouts and its association with Joe Rogan, whose podcast Spotify signed to an exclusive deal. While Young did eventually return his music to Spotify, the incident showed that he's willing to withdraw his work if he disagrees with the platform's direction.

Similarly, Young has been critical of Apple Music's compensation model and has refused to make his music available on some platforms indefinitely. His decisions are driven by conviction rather than commercial calculation.

What's changed with the Amazon decision is that it appears to be permanent (or at least permanent as long as Bezos owns Amazon). Young has made it clear this isn't a negotiating tactic—it's a principle.

Amazon holds significant market share in e-commerce and cloud computing, highlighting its influence across multiple sectors. (Estimated data)

The Role of Wealth and Legacy in Artist Autonomy

Let's be honest: Neil Young can make these decisions because he's wealthy and already has a legacy.

Young has earned millions of dollars over his career. He doesn't need to maximize every revenue stream. He can afford to take a principled stand that reduces his income because he's already financially secure.

An up-and-coming artist in 2025 doesn't have that luxury. If you're trying to build an audience and generate income from your music, you need to be on Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music. You can't afford to refuse Amazon because that would mean losing access to millions of potential listeners and the revenue those streams generate.

This raises an uncomfortable question: Is Young's stance actually helpful for other artists, or is it just something that wealthy, established artists can afford to do while less successful artists are forced to accept unfavorable terms?

The argument for Young's stance being helpful is that it demonstrates to the industry that some artists care more about principles than profits. It shows that the industry's assumptions about artist motivations are wrong. It puts pressure on platforms to improve their terms because if talented artists can afford to refuse them, platforms need to offer better deals.

The argument against is that Young's position actually highlights the inequality in the music industry. Most artists can't afford to make the choices Young makes. So his boycott is, in some sense, a luxury available only to the wealthy and established.

Most likely, the truth is somewhere in the middle. Young's stance is valuable precisely because he has the leverage to make it stick, but that same fact limits how widely his approach can be applied across the industry.

Implications for Independent Artists and Creators

What does Young's decision mean for independent musicians and creators who don't have decades of back catalog or commercial success to fall back on?

The most important implication is about ownership. Young can make these decisions because he owns his master recordings. If you're an independent artist today, you should think very carefully about retaining ownership of your work. Don't sign agreements that transfer ownership to record labels, distributors, or other third parties unless you're getting paid extremely well for that ownership transfer.

Second, there's the question of distribution strategy. Young has essentially decided to distribute his music selectively rather than omnipresently. Instead of being everywhere (Spotify, Apple, Amazon, YouTube Music, etc.), he's choosing to be in some places and not others.

For independent artists, this might translate into a strategy of: "I'll be on the platforms where I'm compensated fairly, and I'll sell directly to fans through my own website or other direct channels." This requires building an audience and a direct relationship with listeners, which is hard work. But it potentially generates more revenue per listener than streaming platforms.

Third, Young's approach suggests that artists should think strategically about who they partner with. Instead of just uploading your music to a distributor who sends it everywhere, you could be more selective. You could offer your music free in certain communities (like Young did with Greenland) while selling it through other channels. You could refuse to work with platforms you disagree with on principle.

Most of this requires leverage, and most independent artists are still building their leverage. But Young's example shows what's theoretically possible when artists have both the commercial success to enforce their principles and the clear conviction about those principles.

The Ethics of Corporate Power in the Streaming Age

At the heart of Young's stance is a broader ethical question about how much power corporations should have over the distribution of creative work.

In the past, artists had limited distribution options. If a major label wanted to sign you, you signed or you didn't get distribution. That gave labels enormous power. But the alternative (being unsigned and having no distribution) was also difficult.

Streaming has changed the distribution problem in one sense—anyone can upload their music to Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music now—but it's created a new power problem: once your music is on these platforms, the algorithms that determine visibility are controlled by the companies themselves. You have no direct relationship with the listener. The platform controls that relationship.

This creates a situation where a few massive companies essentially gate-keep access to listeners. Artists are forced to distribute through these platforms if they want to reach large audiences. The platforms then dictate terms, compensation levels, and policies.

Young's stance is essentially saying: "This concentration of power is wrong, and I'm going to use my position to resist it." Whether you think he's right or not, that's the underlying argument.

What makes it an interesting ethical issue is that it's not just about artist compensation—though that's part of it. It's also about cultural diversity. When a few companies control music distribution and can decide which artists get promoted through algorithms, there's a risk that only music that fits certain commercial profiles gets attention. Music that's challenging, experimental, or culturally different might get buried.

Young's career has included plenty of experimental music. He's made albums that were commercially risky and critically challenging. In today's algorithm-driven environment, some of that work might not get the attention it deserves. That's another reason to be concerned about concentrating distribution power in the hands of a few massive companies.

Potential Ripple Effects: Could This Become a Movement?

The question everyone's asking is: Will other artists follow Young's lead?

Right now, Young is unique because of his stature and his financial security. But if other established artists with significant back catalogs started refusing to license their music to Amazon until better terms were offered, it could actually shift the industry dynamics.

Imagine if all the artists signed to independent labels collectively refused to be on Amazon Music. Amazon would have to negotiate, because losing a significant portion of the music catalog would be catastrophic for their streaming service.

But coordinating that kind of action is difficult. Artists compete with each other for listeners and streams. Getting them to cooperate in refusing to work with a major platform would require a level of industry solidarity that doesn't currently exist.

More likely, we'll see individual artists following Young's lead in smaller ways—refusing to be on specific platforms for specific reasons, licensing their music selectively, finding alternative distribution methods. But a wholesale shift in how music distribution works would require systemic change at an industry level, which seems unlikely in the near term.

What Young's stance does do is open the conversation. It makes it clear that not all artists are willing to accept whatever terms the streaming platforms offer. It shows that there are alternatives to ubiquitous distribution. And it puts pressure on platforms like Amazon to improve their behavior if they want to maintain relationships with high-profile artists.

Technical Considerations: How Distribution Control Works in Practice

For those interested in the technical side, understanding how music licensing actually works is instructive.

When you distribute music to streaming platforms, you typically use a distributor like DistroKid, CD Baby, or TuneCore (now owned by Believe). These companies take your music files and deliver them to Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, and dozens of other platforms simultaneously.

For this convenience, they take a percentage of your revenue (typically 10-15%) or charge an annual fee.

However, the contracts with these distributors typically include clauses that let you remove your music at any time. So if you suddenly decide you don't want your music on Amazon anymore, you can instruct your distributor to stop delivering your music there.

For Neil Young, who owns his master recordings, this is straightforward. He can tell his distributor (if he uses one) or deal directly with platforms to stop licensing his music to Amazon.

For artists signed to major labels, it's more complicated. The label typically controls where the music is distributed. The artist might not have a contractual right to refuse specific platforms. They'd have to negotiate with the label, which reduces their leverage significantly.

This is yet another reason why owning your master recordings is valuable. It gives you the ability to make these kinds of distribution decisions independently.

Looking Forward: The Future of Artist-Platform Relations

What does the future look like for artists and streaming platforms?

There are several possible scenarios. One is that the status quo continues, with artists having limited leverage and platforms dictating increasingly unfavorable terms. This could lead to a situation where making music as a full-time career becomes increasingly difficult for anyone who doesn't have a massive audience or successful side career.

Another scenario is that new technologies or platforms emerge that offer artists better economics. This could be blockchain-based music distribution, AI-powered tools that let artists connect directly with fans, or something we haven't imagined yet.

A third scenario is that regulations change to protect artist interests. Governments could mandate higher minimum payouts, require platforms to be more transparent about algorithms, or impose antitrust restrictions on companies like Amazon that dominate multiple industries.

A fourth scenario is that artists increasingly follow Young's lead and become more selective about where their music is distributed, creating real pressure on platforms to improve their practices.

Most likely, we'll see some combination of these developments. Artists will continue to experiment with new distribution models. Technology will evolve. Regulations will gradually tighten. And some artists will take principled stands like Young's.

What's clear is that the current system—where artists make pennies per thousand streams on platforms that are worth billions of dollars—is not stable long-term. Something has to change, whether through market forces, technological innovation, or regulatory intervention.

Young's stance is a signal that at least some artists are aware that something needs to change, and they're willing to act on that conviction.

The Bigger Picture: Artist Rights in the 21st Century

Neil Young's decisions about his music catalog need to be understood in the context of broader questions about artist rights and creative work in the digital age.

For most of the 20th century, artists had relatively limited options for distributing their work. You either had a record deal or you didn't. If you had a deal, the label controlled distribution and took the majority of the revenue. If you didn't have a deal, you were relegated to local performances and might never reach a national or international audience.

Digital technology was supposed to democratize this. Artists could now upload their work directly to the internet and reach listeners worldwide without needing permission from a corporate gatekeeper.

In some ways, that happened. Independent artists can now build massive audiences without ever signing to a label. But in other ways, new gatekeepers emerged—Spotify, Apple, Amazon—that now control which music gets recommended and how much artists earn from it.

Young's stance is basically saying: "We traded the power of record labels for the power of tech platforms, and it's not clear we made a good deal." That's a conversation worth having.

Moreover, Young's decision to donate his music to Greenland is interesting precisely because it doesn't fit into either the traditional commercial model or the new streaming model. He's creating a distribution method based on values—making music available to people who care about the same issues he does—rather than based on profit maximization or algorithmic recommendation.

If nothing else, Young's actions demonstrate that there are alternatives to the systems we've accepted as inevitable. Artists don't have to be on every streaming platform. They don't have to maximize their streams. They can make choices based on principle, and those choices can carry significant weight and cultural meaning.

That's a valuable lesson for any creative professional thinking about their own work and how they want to distribute it in the world.

FAQ

Why did Neil Young donate his music to Greenland?

Neil Young's donation reflects his commitment to environmental and social causes. Greenland is facing some of the most severe impacts of climate change, and by making his entire catalog available free to residents, Young demonstrated solidarity with a community dealing with existential challenges. The move was more about aligning his creative work with his values than about commercial calculation—Greenland's small population represents minimal revenue potential but enormous symbolic significance.

Can Neil Young legally refuse to have his music on Amazon?

Yes, because Young owns his master recordings. Master recording ownership gives the copyright holder the legal right to decide where and how their music is distributed. Young can refuse to license his music to Amazon or any other platform. Most artists signed to major labels don't have this power because the label owns the master recordings and controls distribution decisions. This highlights the critical importance of artists retaining ownership of their own work.

How much money does an artist earn per stream on Spotify or Amazon?

Artists earn approximately

What is a master recording and why does it matter?

A master recording is the actual audio file of a song—the specific recording in a particular key and tempo that you hear. The copyright holder of a master recording controls where it can be distributed and under what terms. When artists own their master recordings, they have the power to negotiate licensing terms, refuse problematic platforms, and maintain control over their artistic legacy. Most 20th-century recording artists didn't own their masters because record labels historically claimed ownership as part of the record deal.

Will other artists follow Neil Young's lead and boycott Amazon?

It's unlikely on a widespread scale because most artists lack Young's leverage. You need significant back catalog value and financial security to afford refusing a major distribution platform. However, some established artists with ownership of their masters might follow Young's lead on smaller scales. The more significant impact is likely to be individual artists becoming more strategic about which platforms they license to and finding alternative distribution methods that generate better revenue per listener.

What are alternatives to streaming for music distribution?

Alternatives include direct sales through personal websites, Bandcamp (which pays artists 85% of revenue versus Spotify's much smaller percentage), physical media sales, merchandise, live performances, and licensing deals with films or television. Some artists are also experimenting with blockchain-based platforms, subscription services where fans pay directly, and fan-funding models. Most successful independent artists combine multiple revenue streams rather than relying solely on streaming.

Is streaming economically sustainable for musicians as a primary income source?

For most musicians, streaming alone is not sustainable as a primary income source. The math is simply difficult—even successful artists with millions of streams often make less per stream than they would from selling physical media or selling directly to fans. For artists to make a full-time living from music in the streaming age, they typically need to combine streaming revenue with touring, merchandise, crowdfunding, licensing deals, and other income sources. Young's position reflects frustration with this reality.

What does Young's Amazon boycott actually accomplish?

The boycott serves multiple purposes: it signals that not all artists will accept whatever terms platforms offer, it generates media attention around issues of artist compensation and corporate consolidation, it provides a concrete example of an artist exercising control over their work, and it puts pressure on Amazon to improve its practices if it wants to maintain relationships with high-profile artists. Individually, Young's boycott is symbolic, but collectively, if other artists followed suit, it could have significant market impact.

How does music licensing differ from music ownership?

Ownership means you control the work and can decide how it's used. Licensing means you're granting another party permission to use your work under specific terms. For example, Young owns his master recordings, but when he refuses to license them to Amazon, Amazon cannot distribute the music even though Young's music might be in high demand there. The copyright owner always has the right to refuse licensing, which is why ownership matters.

Could Neil Young's stance inspire legislative changes in music industry practices?

Possibly. Young's public advocacy for artist rights contributes to the broader conversation that might eventually lead to legislative action. For example, governments might impose minimum per-stream payouts, require algorithmic transparency, enforce antitrust regulations on companies like Amazon, or mandate profit-sharing arrangements between platforms and creators. However, legislative change typically takes years to develop and implement, and the music industry lobbies heavily to maintain the status quo.

Conclusion: Principles Over Profits

Neil Young's decision to donate his music to Greenland and refuse to license it to Amazon might seem like a simple business decision or a publicity stunt. But it's actually much more significant than that. It's a statement about what artists value and what they're willing to sacrifice for principle.

In an era when streaming platforms control artist visibility and destiny, when tech billionaires amass unprecedented wealth and power, and when corporate consolidation seems inevitable and unstoppable, Young is saying: "I still own my work, I still control my work, and I'm willing to walk away from money if it means staying true to my values."

That's not a solution to the broader problems in the music industry. It's not going to fix the fact that most artists earn pennies per stream or that a few massive companies control music distribution. But it is a demonstration that alternatives exist, that artists don't have to accept whatever terms they're offered, and that there's power in making choices based on conviction rather than commercial calculation.

For artists considering their own distribution strategy, Young's example raises important questions: Do you own your master recordings? Are you comfortable with the platforms carrying your music? Are there ways to distribute your work that better align with your values? Do you have the leverage to make demands, or do you need to build that leverage?

For platforms like Amazon, Young's boycott is a reminder that not all artists are motivated purely by revenue maximization. Some artists care about more than making money. They care about artistic control, fair compensation, corporate ethics, and environmental justice. Platforms that ignore those concerns do so at their peril.

And for the broader music industry, Young's stance is a signal that the current system—where artists subsidize billionaire tech companies with their creative work—might not survive long-term. Eventually, something has to give. Whether it's through market forces, technological innovation, regulatory intervention, or artists collectively demanding better treatment, the economics of streaming are not sustainable in their current form.

Neil Young might not single-handedly change the music industry. But his willingness to make unconventional decisions based on principle rather than profit is exactly the kind of action that shifts cultural expectations over time. It shows what's possible. It opens conversations. It makes people reconsider their assumptions.

In a world where it often feels like profit motive controls everything, watching an older artist with nothing left to prove use his leverage to stand up for his values is genuinely refreshing. It's a reminder that some people—and some artists—still believe that principles matter.

Key Takeaways

- Neil Young donated his entire music catalog to Greenland residents for free, making it accessible without payment

- He refuses to license music on Amazon, declaring it will never be available there while Jeff Bezos owns the company

- Young's decisions reflect his 60-year history of artistic activism and commitment to creative control

- Most artists lack Young's leverage to refuse major platforms because they don't own their master recordings

- Alternative distribution platforms and direct-to-fan sales generate significantly better revenue per listener than streaming services

Related Articles

- AI Music Flooding Spotify: Why Users Lost Trust in Discover Weekly [2025]

- Hi-Res Music Streaming Is Beating Spotify: Why Qobuz Keeps Winning [2025]

- Spotify Listening Activity on Mobile: How to Share What You're Playing [2025]

- Spotify's Real-Time Listening Activity Sharing: How It Works [2025]

- Blue Origin's TeraWave: The Next Satellite Internet Game-Changer [2025]

- Spotify's Prompted Playlist: The AI Music Discovery Feature Explained [2025]

![Neil Young's Greenland Music Donation & Amazon Boycott [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/neil-young-s-greenland-music-donation-amazon-boycott-2025/image-1-1769519286587.jpg)