Introduction: A Landmark Retreat in Labor Enforcement

In a move that shocked labor advocates and legal experts alike, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) quietly dismissed its case against SpaceX in early 2025. The complaint had accused the aerospace company of illegally firing eight employees who dared to criticize CEO Elon Musk in a 2022 open letter. What makes this dismissal extraordinary isn't just that the NLRB lost—it's how it lost. Rather than argue the merits of the case, the board essentially handed over its own regulatory authority, claiming SpaceX should be overseen by the National Mediation Board (NMB), an obscure federal agency designed to mediate labor disputes in the airline and railway industries.

Let that sink in. The NLRB, created by Congress in 1935 to protect workers' right to organize and speak up about workplace conditions, voluntarily surrendered jurisdiction over a case involving alleged retaliation against workers for protected speech. The legal argument? Because SpaceX operates under Federal Aviation Administration licensing and theoretically allows commercial space tourism, it's an "airline" and therefore falls outside the NLRB's purview.

This isn't just a quirk of regulatory classification. It's a watershed moment in American labor law. The decision represents an unprecedented erosion of worker protections in the technology and aerospace sectors, raising fundamental questions about how agencies interpret their mandates and whether they're willing to defend those mandates when challenged. For the eight SpaceX employees who filed complaints, it's a devastating outcome. For workers across tech and emerging industries, it's a warning signal that the traditional guardrails protecting your right to organize and speak up are being dismantled—sometimes not through direct assault, but through reinterpretation and jurisdictional retreat.

Understanding this case requires examining multiple threads: the original labor complaint, SpaceX's creative legal defense, the Trump administration's relationship with Elon Musk, and the broader implications for how American labor law adapts (or fails to adapt) to companies that don't fit neatly into twentieth-century regulatory categories. This comprehensive guide explores each dimension and explains why this moment matters far beyond SpaceX's corporate headquarters.

TL; DR

- The Core Issue: SpaceX fired eight workers in 2022 for circulating a letter criticizing CEO Elon Musk's conduct and public behavior, and the NLRB filed a complaint claiming this violated protected speech rights.

- The Regulatory Twist: Rather than contest the firing on its merits, SpaceX argued the NLRB lacks jurisdiction because SpaceX operates under FAA authority and therefore should be regulated by the National Mediation Board instead.

- The NLRB's Surrender: In January 2025, the National Mediation Board affirmed this jurisdictional argument, and the NLRB promptly dismissed its own case without ever adjudicating the underlying labor violation.

- The Political Context: This decision aligns with the Trump administration's pattern of weakening independent regulatory agencies, particularly after Elon Musk's prominent role in promoting Trump's election and his leadership of the Department of Government Efficiency.

- The Broader Implication: For tech workers and emerging industries, this creates a dangerous regulatory gap where companies can potentially escape NLRB oversight through creative jurisdictional arguments.

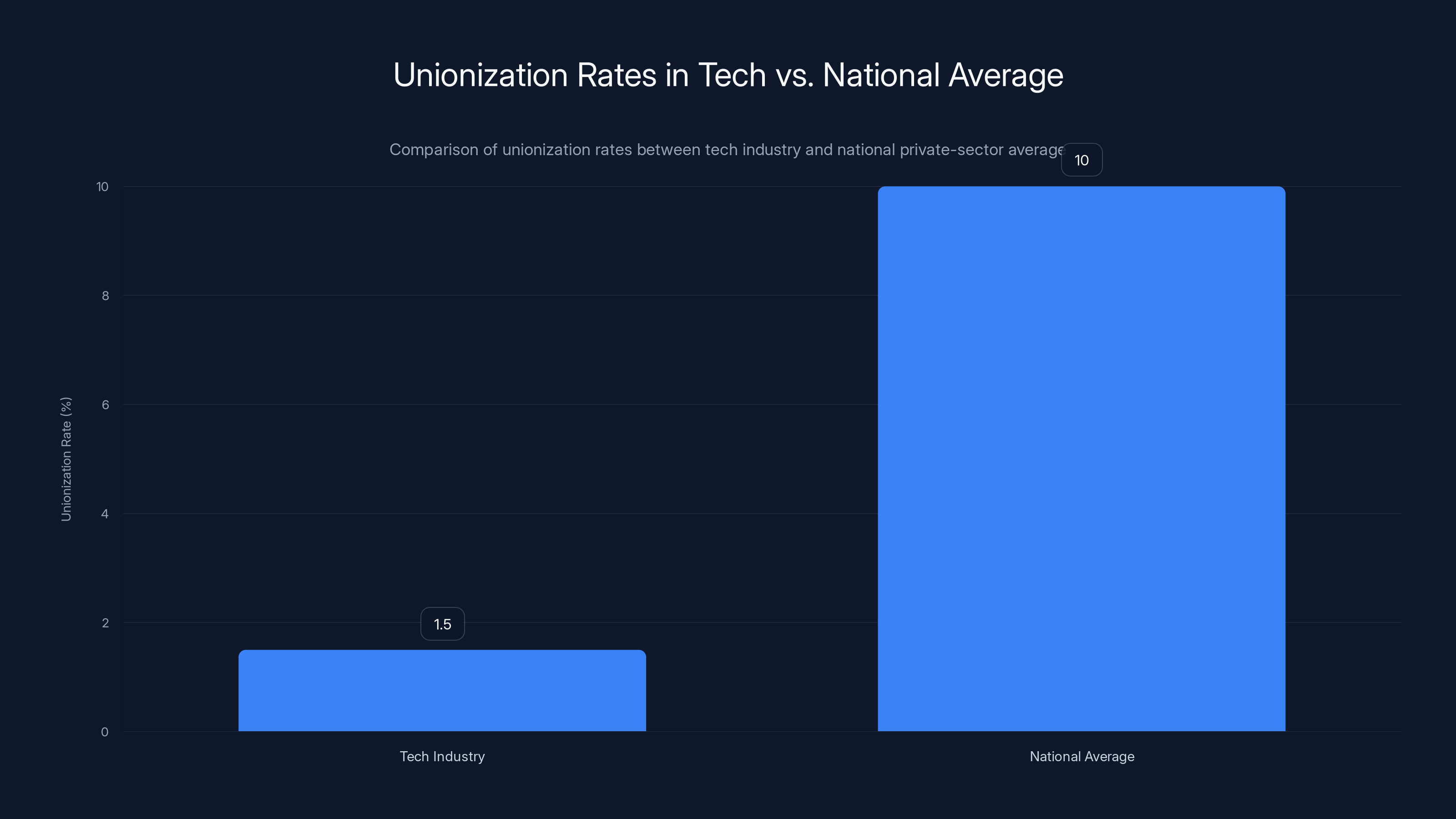

The tech industry has a significantly lower unionization rate (1-2%) compared to the national private-sector average of 10%, highlighting a unique labor challenge.

The Original Complaint: What the SpaceX Workers Actually Did

In June 2022, eight employees at SpaceX's Starbase facility in South Texas circulated an open letter to company management. The letter wasn't a manifesto calling for unionization or demanding radical workplace changes. It was a measured critique of their CEO's public behavior and its impact on the company's culture and reputation.

The letter specifically referenced published reports documenting Musk's sexual misconduct allegations, which had surfaced in both investigative journalism and legal settlements. The employees acknowledged the distinction between private conduct and professional standards, but they argued that in Musk's case, his high-profile social media activity and controversial statements were creating genuine business problems. They called him "a frequent source of distraction and embarrassment" for the company.

This language matters. The employees weren't attacking Musk personally or calling him names. They were making a business-oriented argument: that a CEO's public conduct affects company reputation, employee morale, and ability to attract talent. It's the kind of concern shareholders raise in proxy statements. It's the kind of thing board members discuss in closed meetings. But when regular employees raise it, the response was termination.

SpaceX fired all eight workers within days of the letter circulating. The company's justification centered on the claim that the letter was insubordinate, that employees had violated company policy by going public rather than using internal channels, and that the letter was inappropriate regardless of its factual premises.

But here's the critical legal point: under the National Labor Relations Act, workers have a protected right to engage in "concerted activity" about workplace conditions and management conduct. This protection exists specifically to prevent employers from retaliating against workers for speaking up collectively. The firing triggered an investigation by the NLRB, which concluded that SpaceX's terminations likely violated this protected right.

The NLRB formally filed a complaint in 2024, seeking reinstatement of the employees and back pay. On paper, this seemed like a straightforward protected speech case. The workers were engaged in collective communication, they were discussing matters directly relevant to the workplace (leadership and company reputation), and they were fired immediately after. These facts typically trigger NLRB protection.

What nobody anticipated was SpaceX's response: rather than argue about the substance of the firing, the company would argue the NLRB had no authority to hear the case at all.

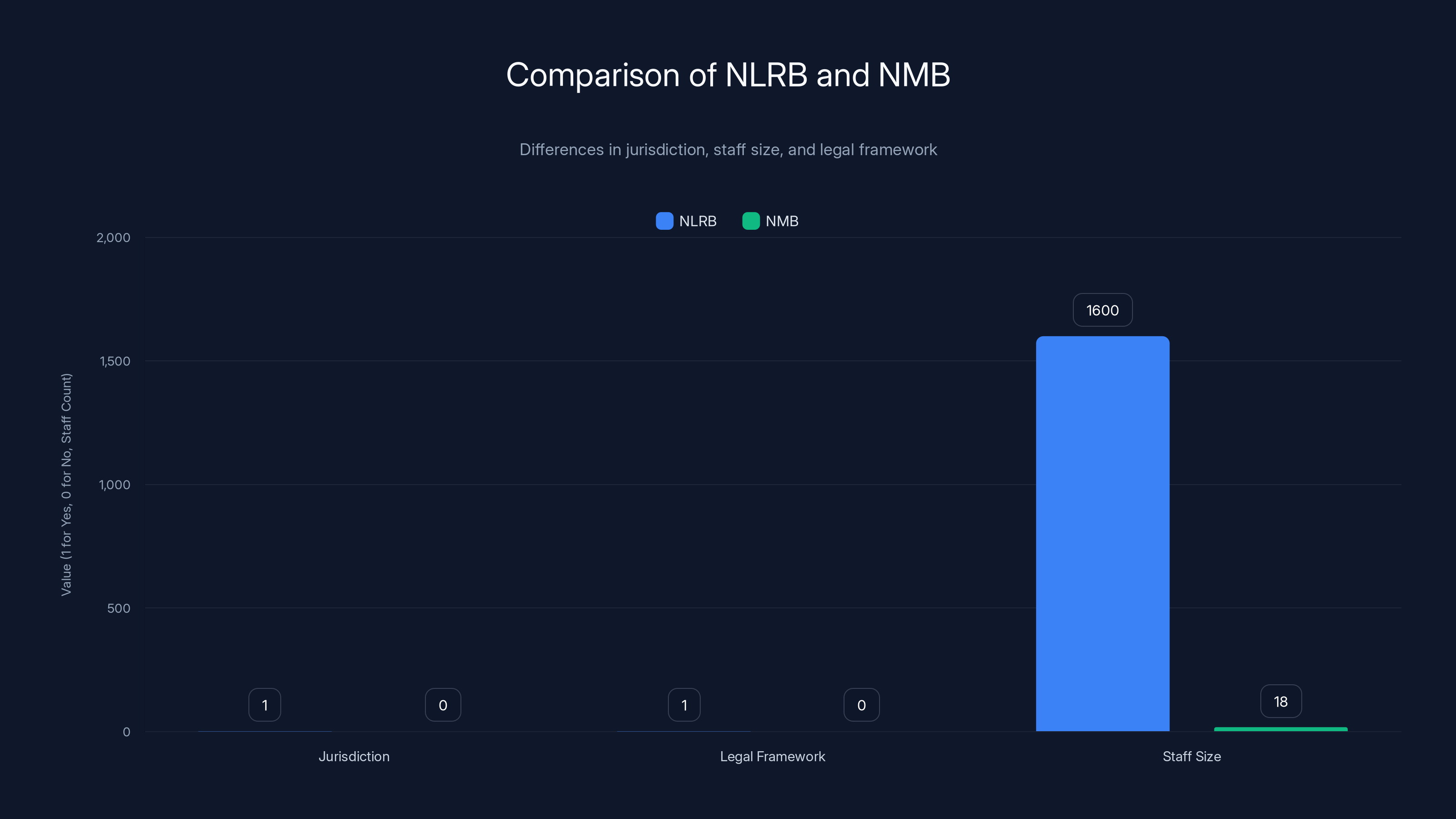

The NLRB and NMB differ significantly in jurisdiction and staff size, with the NLRB covering most private-sector workers and having a much larger staff. Estimated data for illustrative purposes.

SpaceX's Jurisdictional Defense: The "We're an Airline" Gambit

SpaceX's legal team made a move that was equal parts creative and audacious. Instead of defending the firing on its merits, they challenged the NLRB's fundamental authority to regulate the company. Their argument: SpaceX should be classified as an air carrier under federal aviation law, which would place labor disputes under the National Mediation Board's jurisdiction rather than the NLRB's.

To understand why this matters, you need to know that the National Mediation Board operates in a completely different legal framework. Created in 1934 (before the modern NLRB), the NMB has authority over labor disputes in the airline and railway industries. The NMB follows different procedures, has different standards for what constitutes a legal violation, and operates under the Railway Labor Act rather than the National Labor Relations Act. Most importantly, the NMB's framework is oriented toward "cooling off" disputes and forcing arbitration, while the NLRB has more aggressive tools for enforcing worker rights.

SpaceX's argument went like this: The company holds an FAA license as a commercial space launch provider. Under that license, SpaceX can technically offer commercial space flights to paying customers (like tourism flights). Therefore, SpaceX is engaged in air transportation. Therefore, it should be regulated by the NMB, not the NLRB. It's a jurisdictional judo move—using the company's own regulatory licensing against the agency trying to protect workers.

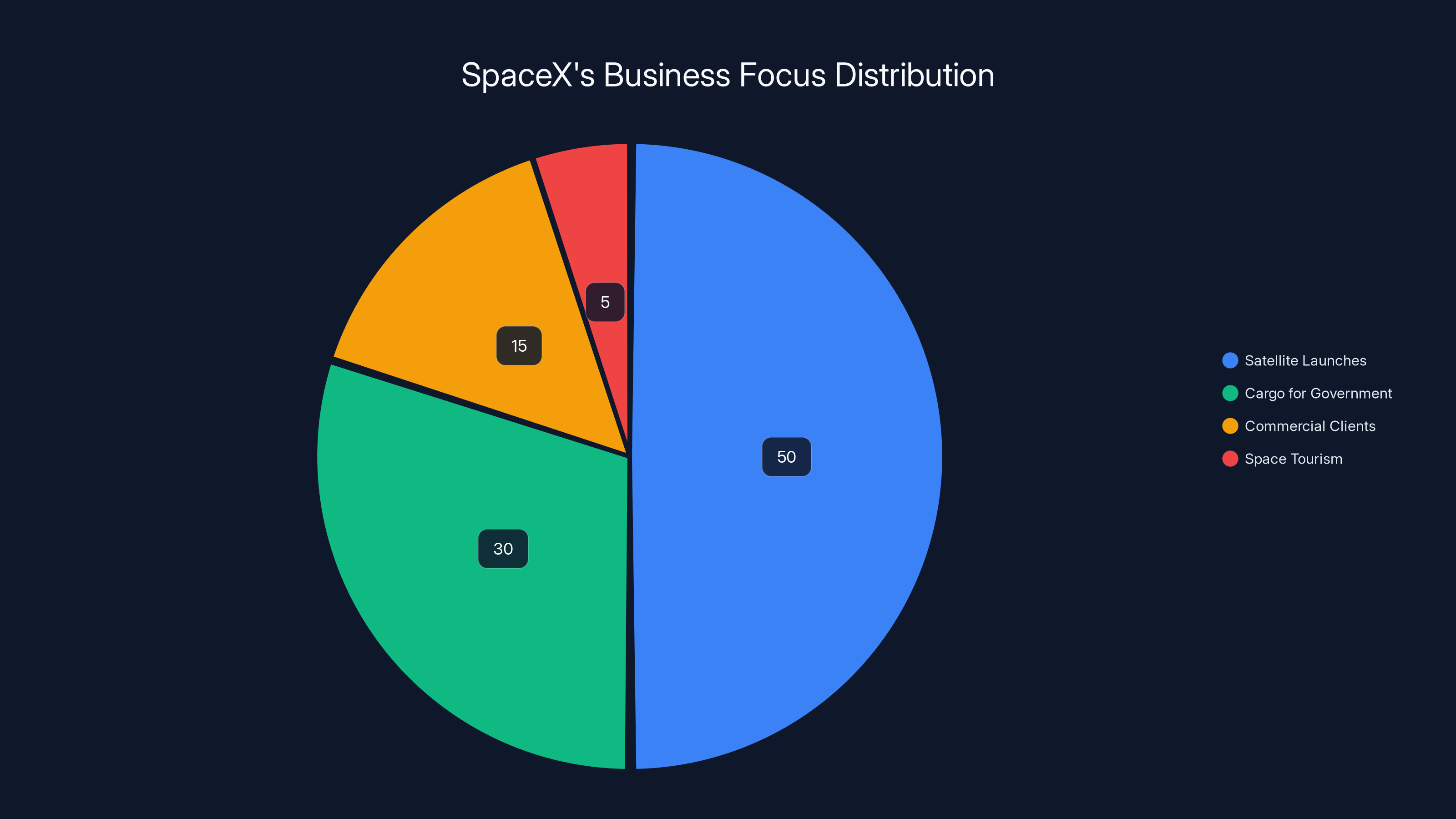

The argument is legally questionable. SpaceX's primary business is launching satellites and cargo for government contracts and commercial clients. Space tourism is a tiny fraction of what the company does. The FAA licensing SpaceX handles—called commercial space transportation licensing—is distinct from the air carrier licensing that typically triggers NMB jurisdiction. The Federal Aviation Administration regulates space launch operations under Title 51 of the United States Code, not the air transportation regulations that created the NMB framework.

Furthermore, SpaceX is not an airline. It doesn't carry passengers on regular commercial routes. It doesn't have flight crews and cabin attendants. It doesn't operate hubs and terminals. The comparison requires such a creative interpretation of what "air transportation" means that it essentially renders the NLRB's jurisdiction meaningless for any company touching the skies.

Yet this legally dubious argument found traction. And not from some obscure circuit court, but from the National Mediation Board itself, which in January 2025 issued a decision affirming that SpaceX should indeed fall under its jurisdiction. The decision essentially created new territory for the NMB—claiming authority over space launch operations—in a way that appears designed specifically to remove SpaceX from NLRB oversight.

The National Mediation Board's Surprising Power Grab

The National Mediation Board's decision to assert jurisdiction over SpaceX was remarkable for multiple reasons. First, it expanded the NMB's purview in ways it had never previously attempted. The agency has existed for over 90 years without claiming authority over space operations. The decision suddenly interprets "air transportation" to include commercial space launches.

Second, the NMB's reasoning appears to rest on a speculative interpretation of SpaceX's potential future business model. The company theoretically could expand space tourism offerings. This potential future activity became the basis for claiming current jurisdiction over all of SpaceX's labor matters. It's a legal precedent that could extend to any company with even tangential connection to aviation or space activities.

Third, and most troubling, the NMB essentially created a new labor regulatory framework for SpaceX without any congressional action or formal rulemaking. The agency simply declared that SpaceX was within its jurisdiction and therefore subject to Railway Labor Act procedures rather than National Labor Relations Act protections.

The National Mediation Board is not designed for modern tech and aerospace companies. Its procedures were developed for large, established airlines with unionized workforces and long histories of labor-management relations. The agency's whole framework assumes that disputes will be between established unions and large carriers. SpaceX's situation—individual workers speaking up without union representation—fits awkwardly into the NMB's model.

Moreover, the Railway Labor Act framework, which governs NMB jurisdiction, actually provides fewer protections for workers seeking to organize or engage in collective action than the National Labor Relations Act. The RLA requires union elections to include only employees in the specific class or craft affected—a high bar that makes organizing difficult. The NLRA's frameworks are generally more protective of worker rights and collective action.

The NLRB's response was swift and, frankly, startling. Rather than challenge the NMB's assertion of jurisdiction, the NLRB simply dismissed its own case. The board didn't issue a lengthy opinion explaining why it disagreed with the jurisdictional claim. It didn't appeal or seek clarification. It simply accepted the NMB's assertion and withdrew from the case.

This wasn't the NLRB being overruled by a court. It was the NLRB voluntarily ceding its authority based on another agency's assertion. The precedent is unprecedented: one regulatory agency essentially transferred its jurisdiction over a specific company to another agency, not through legislative action but through administrative deference.

Estimated data shows SpaceX's primary focus is on satellite launches and government contracts, with space tourism being a minor part of their operations.

The Elon Musk Factor: Politics and Regulatory Capture

Understanding why the NLRB abandoned its case requires understanding the peculiar relationship between Elon Musk and the Trump administration. This isn't speculation—the connection is explicit and documented.

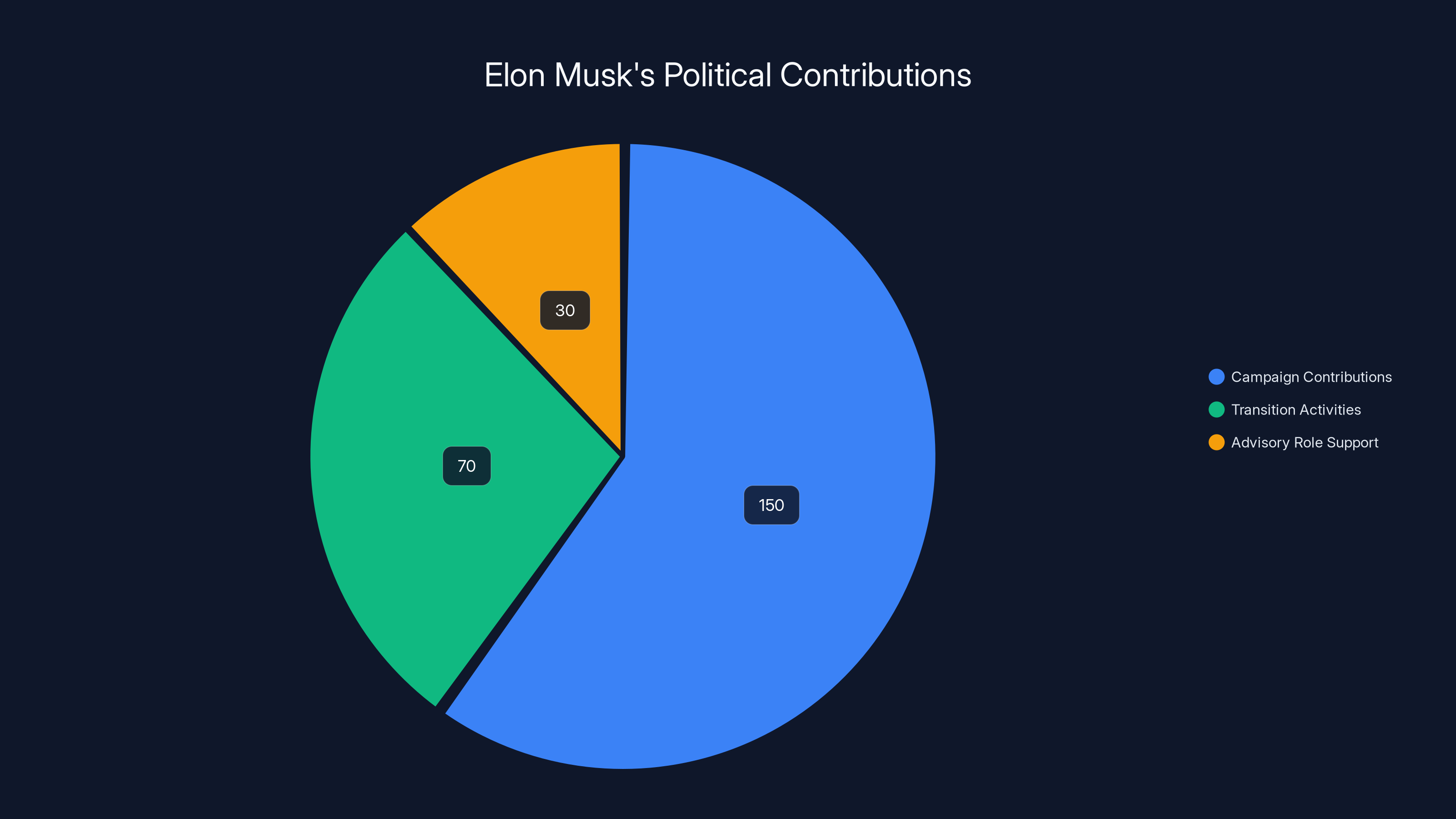

Musk spent over $250 million to support Donald Trump's 2024 election campaign and subsequent transition activities. After Trump's election, Musk received an informal advisory role in the Department of Government Efficiency, a Trump initiative focused on reducing federal spending and eliminating regulations. Musk used this position to advocate for cuts to federal agencies, including the NLRB.

The NLRB has been a particular target of Trump administration skepticism. The board has worked to protect worker organizing rights and enforce labor standards in ways that conservatives and business groups view as overreach. Multiple Trump appointees have questioned whether the NLRB's structure violates constitutional separation of powers principles. The same critique has been leveled at other independent agencies.

But here's what makes the SpaceX case different: the NLRB didn't get defunded. Congress didn't pass legislation stripping its authority. Instead, the board voluntarily interpreted its jurisdiction in a way that removed a politically significant company from its oversight. The decision appears designed to avoid a conflict with the Trump administration over an Elon Musk company.

This is regulatory capture in real time, except it's not being captured by the regulated industry in the traditional sense. Rather, it's being captured by political pressure. An independent agency is reshaping its interpretation of its legal authority to avoid conflict with the current administration and a politically connected billionaire.

The precedent is genuinely dangerous. If the NLRB can interpret its jurisdiction narrowly to avoid regulating companies with political connections, then the entire framework of worker protection becomes contingent on political influence. Tech companies without Musk's clout could still face NLRB investigation. Companies explicitly supporting Trump might receive similar deference. The law becomes whatever those currently in power want it to be.

Why the Jurisdictional Argument Falls Apart on Legal Grounds

From a straightforward legal perspective, SpaceX's argument and the NLRB's acceptance of it are problematic. Let's break down why.

First, SpaceX is not actually an air carrier in any meaningful sense. The company is a space launch provider. Its business model centers on launching satellites, cargo, and astronauts to orbit. Commercial space tourism is a sideline—discussed, planned, but not currently generating significant revenue. The Federal Aviation Administration licenses commercial space launch operations under a completely different statutory framework than air transportation.

The Federal Aviation Administration's authority over SpaceX comes from Title 51 of the United States Code, the Commercial Space Launch Act. This statute created a distinct regulatory regime for commercial space activities. Congress explicitly separated space transportation regulation from air transportation regulation. The FAA has a separate office—the Office of Commercial Space Transportation—that handles space launch licensing. It's not the same as air carrier licensing.

Second, the statutory definition of "air carrier" in federal aviation law does not include space launch providers. Air carriers are defined as entities that engage in "air transportation" of passengers or cargo on scheduled or charter flights. Space launches aren't air transportation—they're space transportation. They operate in space, not in airspace. The distinction matters legally because it determines which federal statutes apply.

Third, the National Mediation Board's assertion of jurisdiction contradicts decades of administrative practice. The NMB has not previously claimed authority over space operations. If Congress intended space transportation to fall under NMB jurisdiction, it would have amended the Railway Labor Act to explicitly include it. The fact that Congress hasn't done so, despite multiple opportunities, suggests the current regulatory structure is intentional.

Fourth, applying the Railway Labor Act to SpaceX creates absurd results. The RLA assumes union-represented workforces and formal labor-management structures designed for large carriers. SpaceX's workforce is non-unionized engineers and technicians. Shoehorning SpaceX into an RLA framework that was designed for airline flight crews and railway workers makes no practical sense.

Finally, the whole jurisdictional argument proves too much. If SpaceX is an airline because it theoretically could carry tourists to space someday, then would Amazon be an airline because it owns and operates planes for cargo delivery? Would Tesla be an airline because it manufactures vehicles that operate on roads underneath the sky? The logic is so expansive that it could encompass nearly any company with even tangential connection to transportation.

Yet despite these legal problems, the argument succeeded. Why? Because the NLRB chose not to fight it. The board had multiple options: it could have challenged the National Mediation Board's assertion of jurisdiction in federal court. It could have issued a decision explaining why the jurisdictional argument was unfounded. It could have asked Congress for clarification. Instead, it surrendered.

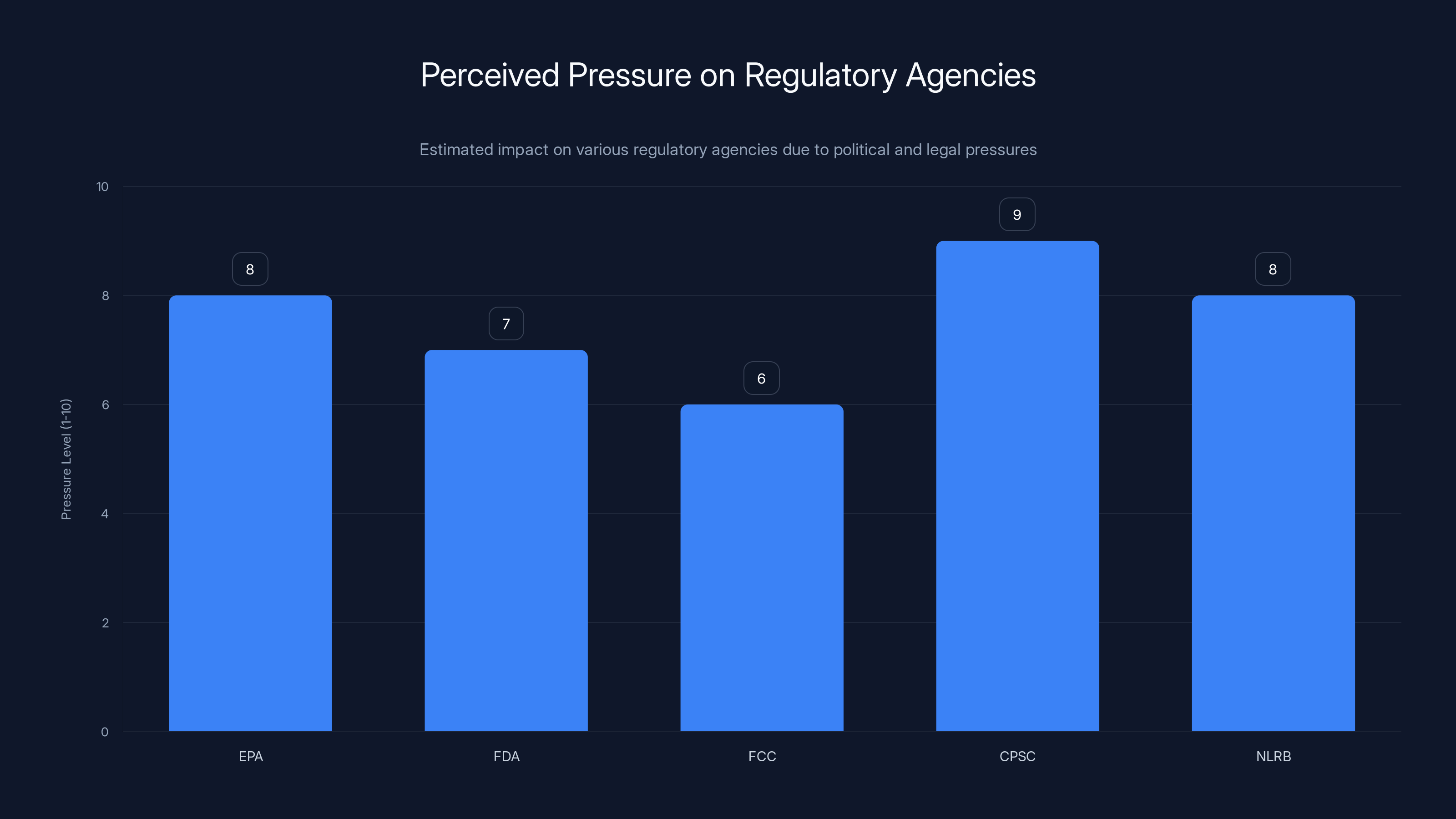

Estimated data shows that agencies like the CPSC and EPA are under significant pressure due to legal and political challenges, potentially affecting their regulatory capabilities.

The Broader Context: Regulatory Agencies Under Pressure

The SpaceX decision doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a pattern of independent regulatory agencies being pressured, defunded, or reinterpreted to reduce their oversight of politically connected companies and industries.

Consider the Consumer Product Safety Commission, which Amazon has also challenged on constitutional grounds similar to SpaceX's challenges to the NLRB. The CPSC regulates product safety—an area where Amazon has interests given its marketplace operations. Amazon's legal team argued that the CPSC's structure violates separation of powers principles, meaning Congress can't delegate certain enforcement powers to independent agencies.

That argument sounds like a technical constitutional question. But in practice, if courts accept it, it would essentially eliminate independent agency authority across the federal government. The implications are staggering: the EPA couldn't regulate pollution, the FDA couldn't approve drugs, the FCC couldn't manage spectrum. Accepting these challenges would require restructuring the entire administrative state.

Yet these constitutional arguments are being taken seriously by courts, particularly courts appointed during the Trump administration. The Supreme Court has already suggested sympathy to these separation of powers arguments in other contexts.

What we're seeing is a coordinated effort to weaken regulatory agencies, either through direct attacks on their constitutional authority or through the jurisdictional maneuvers employed in the SpaceX case. Companies use constitutional arguments to force agencies to surrender jurisdiction or narrow their interpretation of their powers. Agencies under political pressure comply rather than fight.

The result is a system where regulatory protection depends increasingly on political factors. Companies with political connections, supportive administrations, or sufficient legal resources can escape regulation. Other companies face full enforcement. Workers at politically connected companies lose labor protections. Workers at other companies retain them.

This isn't the regulatory system Congress designed. It's a system corroded by politics and financial pressure.

What "Protected Speech" Means Under Labor Law

To understand what the SpaceX workers lost when the NLRB dropped its case, you need to grasp what protected speech actually means in the labor context. It's not the same as First Amendment protection, which only constrains government action.

The National Labor Relations Act, passed in 1935, established the principle that workers have a right to engage in "concerted activity." This includes the right to organize unions, but it's broader than that. It includes the right to collectively discuss wages, hours, benefits, and terms and conditions of employment. It includes the right to publicly criticize management practices that affect workers.

The protection exists because Congress recognized that individual workers have little power to negotiate with large employers. Without legal protection, workers who speak up face retaliation. With protection, workers can collectively advocate for change without fear of termination.

For the SpaceX workers, the protected activity was clear: eight employees collectively decided to send a letter to management raising concerns about the CEO's conduct and its workplace impact. This is textbook concerted activity. They weren't acting alone. They weren't expressing purely personal views. They were engaging in collective communication about workplace matters.

The fact that the letter was public (rather than confidential) strengthens the case, not weakens it. The NLRB has consistently held that public communication about workplace conditions is protected activity. In fact, going public is often a more powerful form of concerted activity than private grievances because it creates external pressure on the employer.

The fact that the workers criticized the CEO personally doesn't remove protection either. Courts have held that workers can criticize management conduct as long as the criticism relates to workplace conditions or the company's operations. Musk's public conduct and reported misconduct are relevant to SpaceX's workplace culture and reputation, making the workers' criticism clearly workplace-related.

Under normal NLRB procedures, SpaceX's retaliation would be found to violate the National Labor Relations Act. The company would be ordered to reinstate the workers with back pay and remove any discipline from their records. The company might also be required to post notices about workers' rights and commit to preventing future retaliation.

These remedies exist precisely because employers have overwhelming power over workers. A single termination can wreck a career, particularly in specialized industries like aerospace engineering where references matter. The NLRA's protections try to level the playing field by making retaliation itself illegal.

But those protections only work if the NLRB actually enforces them. Once the board stepped aside, the workers lost their legal recourse.

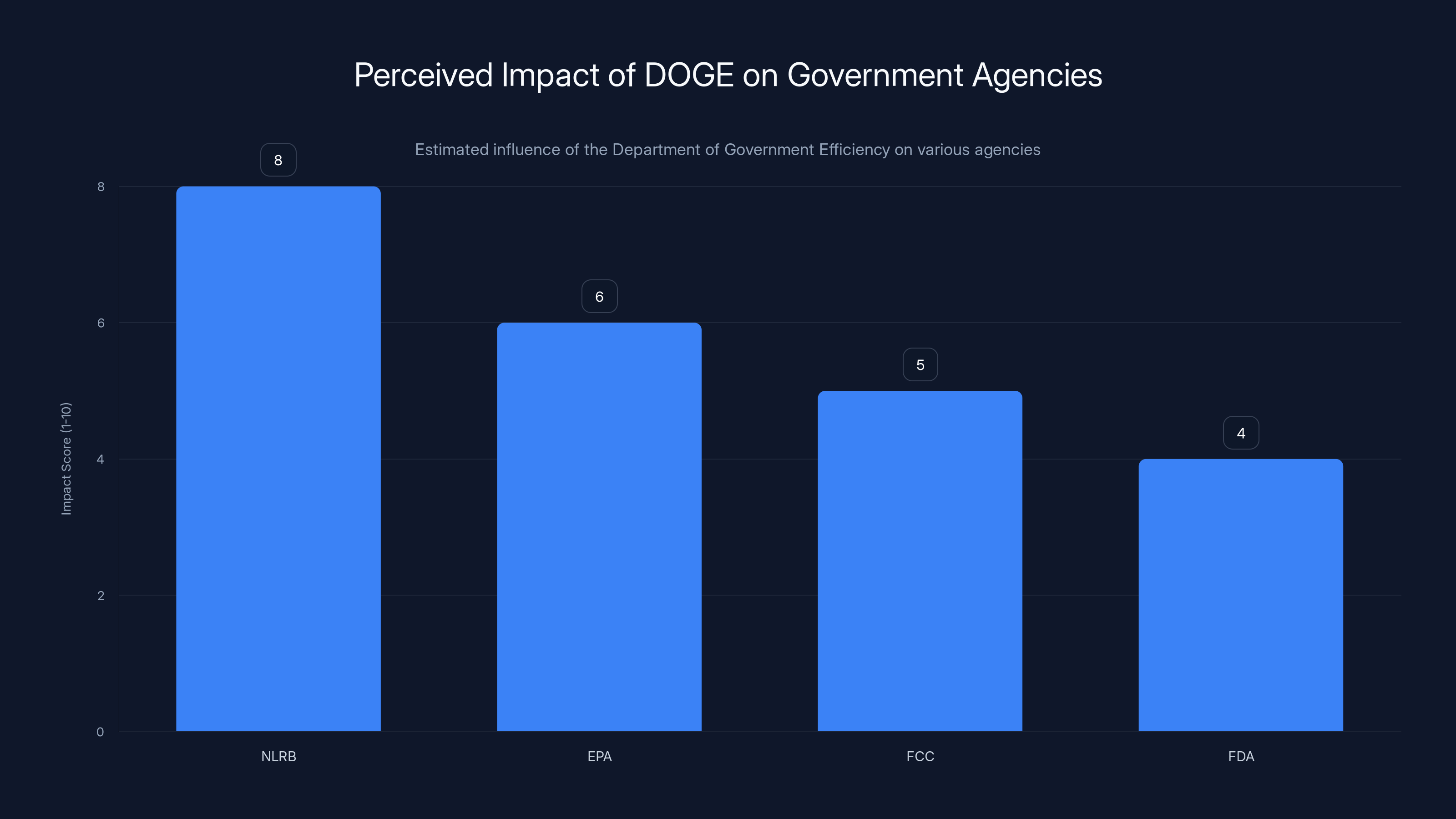

Estimated data suggests that DOGE has the highest perceived impact on the NLRB, aligning with its focus on reducing regulatory burdens.

The Tech Industry's Broader Labor Challenges

The SpaceX case resonates throughout the technology industry because many tech companies face similar pressures from labor organizing and worker activism. The case establishes a precedent: if you're creative enough with jurisdictional arguments and politically connected enough to make those arguments stick, you can escape labor law oversight.

Tech companies have been remarkably successful at avoiding unionization compared to other industries. Only about 1-2% of tech workers are unionized, far below the national private-sector average of around 10%. This low unionization rate persists despite significant worker discontent with wages, benefits, overtime, and workplace culture.

But the lack of unionization hasn't meant the absence of worker activism. Tech workers have organized walkouts, written open letters, started employee networks, and engaged in public advocacy around compensation, working conditions, and company conduct. Companies like Google, Amazon, and Meta have faced internal organizing drives.

The NLRB has been the backstop for these efforts, providing legal protection for worker speech and organizing activity. When companies retaliate against organizing leaders or speaker-activists, the NLRB investigates and seeks remedies.

The SpaceX precedent suggests that mechanism is now in jeopardy. Tech companies could explore similar jurisdictional arguments. A drone delivery company might argue it falls under FAA authority. An autonomous vehicle company might claim transportation regulation. A biotech firm might invoke FDA jurisdiction. If the NLRB accepts these arguments, worker protections evaporate.

The precedent also matters for emerging industries. Space, autonomous systems, artificial intelligence, biotechnology—these are all areas where regulation is still being developed. Companies will argue that existing frameworks don't apply or that new specialized regulators should take jurisdiction. If the NLRB cedes authority in these areas, workers in these high-growth sectors will lose labor law protection just as industries are scaling.

For workers in tech and adjacent industries, the SpaceX decision is a warning signal. The legal protections you thought you had might not apply if your employer is politically connected or operates in an emerging technology area.

How the National Mediation Board Actually Works

Understanding the implications of SpaceX falling under NMB jurisdiction requires knowing how the National Mediation Board operates. It's a very different system than the NLRB, designed for a completely different context.

The National Mediation Board was created in 1934 to handle labor disputes in the airline and railway industries. At the time, these were dominant industries with large unionized workforces and significant labor-management conflict. Congress created the NMB as a specialized agency to mediate these disputes and prevent the disruptions that labor unrest could cause in critical transportation industries.

The NMB's primary function is mediation and arbitration. When a labor dispute arises, the NMB tries to bring the parties together and help them reach agreement. If mediation fails, disputes go to arbitration, where a neutral arbitrator hears both sides and imposes a binding decision. This system is designed to minimize disruption to transportation services.

But here's the critical difference: the NMB framework assumes unionized workforces. It's designed for situations where you have a union representing employees and management representing the company. The processes are structured around collective bargaining agreements, grievance procedures, and formal labor-management institutions.

SpaceX's workforce isn't unionized. The company doesn't have collective bargaining agreements. There's no established union representing engineers and technicians. Trying to fit SpaceX into the NMB framework creates practical problems.

Moreover, the NMB has much smaller resources than the NLRB. The NMB has approximately 18 employees. The NLRB has approximately 1,600 employees across regional offices nationwide. The NMB simply doesn't have capacity to investigate claims the way the NLRB does.

The NMB also operates under the Railway Labor Act, which has different legal standards. The RLA doesn't have the same protections for individual workers engaging in protected activity. It's focused on collective bargaining between unions and management. A single worker or small group of workers claiming retaliation might not fit neatly into the RLA framework.

The practical result: SpaceX workers now fall under an agency that wasn't designed for their situation, lacks resources to investigate their claims, and operates under statutory frameworks that offer less protection than the NLRA.

Estimated data shows Musk's $250M support was primarily directed towards campaign contributions, with significant funds also allocated to transition activities and advisory role support.

The Political Dynamics: Department of Government Efficiency and Regulatory Rollback

Elon Musk's role in the Trump administration's Department of Government Efficiency deserves detailed examination because it provides context for why the NLRB might have abandoned the SpaceX case.

The Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, is not a traditional federal agency. It doesn't have statutory authority or independent funding. Instead, it's an advisory body consisting of Musk and another entrepreneur, positioned within the executive office to recommend ways the government can reduce spending, eliminate regulations, and increase efficiency.

Musk's mandate is explicitly to cut government spending and eliminate agencies and regulations he deems wasteful. The NLRB has been explicitly targeted in DOGE discussions and proposals. Musk and his allies view the NLRB as a regulatory burden on business, an agency that creates unnecessary litigation and prevents companies from managing their workforces as they see fit.

From this perspective, the NLRB investigating SpaceX is exactly the kind of regulatory overreach that DOGE seeks to eliminate. The case represents government meddling in private business operations. The fact that the case involves Musk's own company makes it a perfect symbol of regulatory excess to attack.

Now, the NLRB isn't directly controlled by the executive branch in the way traditional agencies are. The President appoints the board members, but there's supposed to be some independence once they're in office. The board doesn't answer to the President or the Department of Government Efficiency.

But NLRB leadership is aware of the political environment. They know that Musk has the President's ear. They know that the administration is seeking to weaken the NLRB. They know that a high-profile clash with Musk's company could be used to justify efforts to defund or eliminate the agency.

In this context, accepting the National Mediation Board's jurisdictional claim becomes attractive to NLRB leadership. It allows them to avoid a confrontation with Musk and the Trump administration. It removes a politically sensitive case from the board's docket. It demonstrates deference to other agencies' jurisdictional claims, which could become useful if Congress challenges the NLRB's scope.

This is regulatory capture, but not in the traditional form. The NLRB isn't being captured by the regulated industry directly. Instead, it's being captured by political pressure from the executive branch and the political influence wielded by a single billionaire with administration access.

The precedent is alarming: if agencies can be pressured to abandon jurisdiction through political influence, then regulatory protections become contingent on political power rather than law.

Precedent and Implications: What This Means for Other Companies and Industries

The SpaceX decision creates a dangerous precedent for future regulatory evasion. Once a company successfully escapes one agency's jurisdiction through creative legal arguments, other companies will attempt similar strategies.

Consider the implications for different industries. A commercial drone delivery company might argue it's an air carrier and therefore falls under NMB jurisdiction. An autonomous vehicle company might claim DOT transportation authority supersedes NLRB jurisdiction. A gene therapy company might argue FDA authority over healthcare matters puts it outside NLRB scope. A financial technology company might claim SEC jurisdiction over securities matters removes NLRB authority.

Each argument follows the same template: the company operates in a regulated industry, a specialized regulator has authority over that industry, therefore labor matters should fall under that specialized regulator. The arguments are often legally weak, but they're strategically useful because they force the NLRB to expend resources defending jurisdiction rather than protecting workers.

If the NLRB consistently accepts these jurisdictional challenges, the agency's scope of authority shrinks dramatically. The board could end up with jurisdiction only over traditional manufacturing and retail operations, while technology, aerospace, healthcare, and finance—all rapidly growing sectors—escape coverage.

The result would be a two-tiered labor system. Workers in traditional industries have NLRB protection. Workers in emerging industries and regulated sectors have protections from specialized agencies designed for different contexts. The protections are unequal and unpredictable.

Furthermore, this precedent empowers other agencies to accept jurisdiction even when they're not well-suited to the task. The National Mediation Board has no particular expertise in space launch operations or commercial spaceflight. It has no established procedures for investigating worker complaints in non-unionized tech companies. By accepting jurisdiction, the NMB takes on responsibilities it's not equipped to handle.

The real loser in this scenario is workers. They lose clear, predictable legal protections. They gain protections from agencies that may not be equipped to provide them. Meanwhile, companies gain the ability to shop for favorable regulatory jurisdictions based on creative legal arguments and political pressure.

The Question of Congressional Intent and Statutory Interpretation

At its core, the SpaceX decision raises fundamental questions about how federal agencies should interpret their statutory authority. These questions matter not just for labor law but for the entire administrative state.

When Congress creates an agency and grants it jurisdiction over certain activities, there are different ways to interpret that jurisdiction. One approach, called textualism, focuses strictly on the words Congress used. If Congress said the NLRB regulates "interstate commerce" in specified industries, then the NLRB's jurisdiction extends to all such commerce except what Congress explicitly excluded.

Another approach, called purposivism, looks at what Congress intended to accomplish when it created the agency. What problems was Congress trying to solve? What activities did Congress view as problematic? The agency's jurisdiction should extend to modern versions of those problems, even if Congress didn't anticipate the specific activities.

A third approach, often used in administrative law, is deference to agency interpretation. If an agency interprets its own jurisdiction in a reasonable way, courts should defer to that interpretation rather than second-guessing the agency's judgment.

The SpaceX case suggests a fourth approach: deference to other agencies' jurisdictional claims. The NMB asserted jurisdiction, and the NLRB accepted that assertion without significant questioning. Neither agency carefully analyzed whether Congress intended space launch operations to fall under RLA jurisdiction. Neither agency examined whether the NMB is well-equipped to handle these disputes. Instead, there was an implicit agreement that the NMB gets to expand its jurisdiction, and the NLRB gets to contract its own.

This approach is problematic because it removes the decision-making from Congress, where it belongs. Congress structured the NLRB and the NMB with different authorities for different reasons. If Congress wanted space companies to fall under NMB jurisdiction, it would have amended the RLA to say so explicitly. The fact that Congress hasn't done so, despite multiple opportunities, suggests the current allocation of jurisdiction is intentional.

When agencies rewrite their jurisdictions through interpretation, they usurp Congressional authority. Congress designed our labor law system. Congress decided which workers get NLRB protection and which might fall under other frameworks. For agencies to simply trade jurisdiction based on convenience or political pressure violates the basic principle that agencies derive their authority from Congress.

The SpaceX case suggests we need clearer Congressional direction on how emerging industries should be regulated. Space companies, autonomous systems, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology are all growing rapidly. Rather than letting agencies compete for jurisdiction or allowing companies to forum-shop, Congress should clarify which agencies regulate which activities and ensure that workers in all industries have clear, predictable labor law protections.

What Happens to the Eight Workers Now

For the eight SpaceX employees who filed the original complaint, the NLRB's decision is devastating. They've lost their primary legal recourse for challenging their terminations.

Some of these workers might be able to file lawsuits in civil court, arguing breach of implied covenant of good faith or similar tort theories. But these suits face significant obstacles. First, Texas, where SpaceX is based, is an at-will employment state, meaning employers can fire workers for any reason except a few specifically prohibited reasons (like race discrimination or legal retaliation). Second, proving a tort claim requires clear evidence of wrongdoing, and SpaceX will argue it had legitimate business reasons for termination.

Other workers might pursue remedies through the National Mediation Board now that it has asserted jurisdiction. But as discussed, the NMB's framework is designed for unionized industries and collective bargaining, not individual worker complaints. The remedies available under the RLA are different from NLRB remedies, and potentially less robust.

Some workers might try to appeal the NLRB's decision in federal court, arguing the agency misinterpreted its own jurisdiction. But courts are generally deferential to agency interpretations of their scope, and challenging an agency's decision to surrender jurisdiction is unusual.

In practical terms, these workers are unlikely to get their jobs back or receive back pay. They may have references problems at other aerospace companies. They've been labeled as people who criticized the CEO publicly, which future employers might view as a negative signal regardless of the legality of their action.

Their case has become a cautionary tale for other workers: the legal protections you thought you had might not apply if your employer is politically connected or operates in an emerging industry. Speaking up collectively about workplace conditions is risky in ways it wasn't supposed to be under the National Labor Relations Act.

Comparing NLRA vs. RLA: Why the Framework Matters

To fully understand what workers lost when the NLRB ceded jurisdiction to the NMB, you need to compare the legal frameworks governing each agency.

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA)

Passed in 1935, the NLRA established a broad framework protecting worker organizing and collective action. The statute covers most private-sector workers except those explicitly excluded (independent contractors, supervisors, agricultural workers, domestic workers).

Under the NLRA, workers have the right to organize unions, engage in collective bargaining, and engage in protected concerted activity. The statute prohibits employer retaliation for protected activity. The NLRB investigates violations and can order reinstatement, back pay, and other remedies.

The NLRA protects individual workers and small groups, not just formally designated unions. A few workers talking about wages or working conditions, even without union involvement, are protected.

The NLRA allows workers to strike and protects them from retaliation for striking. It requires companies to bargain in good faith with unions. It prohibits company unions and other forms of employer interference in worker organization.

The Railway Labor Act (RLA)

Passed in 1926 (before the NLRA), the RLA governs labor relations in the railway and airline industries. The statute assumes unionized workforces and formal collective bargaining relationships.

Under the RLA, workers can organize unions and engage in collective bargaining, but the processes are different from the NLRA. The RLA requires unions to represent entire classes or crafts of workers, not just specific groups. The RLA mandates that labor disputes go to the National Mediation Board for mediation and, if necessary, arbitration.

The RLA heavily restricts strikes. Before striking, unions must follow extensive mediation and arbitration processes. The President can invoke cooling-off periods, essentially stopping strikes for months at a time. The RLA assumes that strikes in transportation industries are so disruptive to the public that they should be heavily restricted.

The RLA is oriented toward stability and public interest rather than worker protection. It assumes unionized, organized workforces negotiating collective agreements. It doesn't protect individual workers or small groups engaging in spontaneous action.

The Consequences for SpaceX Workers

Under the NLRA, eight SpaceX workers collectively circulating a letter is protected activity. The NLRB investigates, finds the firing violated the statute, and orders reinstatement and back pay.

Under the RLA, those same eight workers would need to belong to a union representing their class of workers. The activity might not be "protected" in the same way because the RLA focuses on formal collective bargaining. The National Mediation Board would mediate rather than investigate and enforce.

The RLA framework essentially requires workers to be unionized before engaging in protected activity. Individual workers speaking up don't have the same protections. The system is designed for formalized labor relations, not spontaneous worker action.

This difference is profound. The NLRA protected the SpaceX workers because they engaged in collective action without needing a union. The RLA would likely not provide the same protection because they're not part of an established bargaining unit.

By moving SpaceX to RLA jurisdiction, the NLRB removed protection for exactly the kind of worker activity that occurred—spontaneous collective speech by non-unionized workers.

FAQ

What is the National Labor Relations Board and why does it matter?

The National Labor Relations Board is a federal agency created in 1935 to enforce the National Labor Relations Act. The NLRB protects workers' rights to organize unions, engage in collective bargaining, and engage in protected concerted activity without fear of employer retaliation. The board investigates complaints of unfair labor practices and can order remedies like reinstatement and back pay. For non-unionized workers, the NLRB is often their primary source of legal protection against workplace retaliation.

What is concerted activity under labor law?

Concerted activity means action taken by two or more employees together for the purpose of improving working conditions, wages, benefits, or addressing workplace grievances. This can include organizing for union representation, collectively discussing wages or working conditions, publicly criticizing management practices that affect work, and similar activities. The National Labor Relations Act protects concerted activity even when workers aren't unionized, meaning employers cannot legally retaliate against workers for engaging in these activities.

How is the National Mediation Board different from the NLRB?

The National Mediation Board, created in 1934, handles labor disputes in the airline and railway industries. The NMB operates under the Railway Labor Act and focuses on mediation and arbitration. It's designed for unionized workforces negotiating collective agreements in transportation industries. The NLRB, created a year later, operates under the National Labor Relations Act and covers most private-sector workers. The NLRB investigates unfair labor practices and can order enforcement remedies. The NMB has much smaller staff (about 18 employees versus the NLRB's 1,600) and operates under a different legal framework with different protections.

Why did SpaceX argue it should fall under the National Mediation Board's jurisdiction?

SpaceX argued that because it holds a Federal Aviation Administration license for commercial space transportation and theoretically offers commercial space flights, it should be classified as an air carrier. Air transportation falls under the National Mediation Board's jurisdiction via the Railway Labor Act. By moving to the NMB's jurisdiction, SpaceX would escape the NLRB's investigation into the illegal firing claims. The National Mediation Board's framework provides fewer protections for individual workers engaging in spontaneous activity and is oriented toward formal collective bargaining in unionized settings.

What happens to worker protections if the NLRB loses jurisdiction over tech and aerospace companies?

If the precedent established in the SpaceX case spreads, tech and aerospace workers could lose the protections the NLRB provides. These workers would fall under specialized regulators (FAA, FCC, FDA) that weren't designed to protect worker rights. The result would be a two-tiered system where workers in traditional industries have strong NLRB protections while workers in emerging industries lack clear labor law protection. This creates incentives for companies to argue for specialized regulatory jurisdiction to escape labor law oversight.

What was Elon Musk's specific involvement in the decision to drop the case?

Elon Musk didn't directly make the decision to drop the case, which was made by NLRB leadership and affirmed by the National Mediation Board. However, Musk's political influence likely created pressure behind the scenes. Musk spent over $250 million supporting the Trump administration and serves in an advisory role in the Department of Government Efficiency, which has explicitly targeted the NLRB for criticism. The NLRB's decision to accept the NMB's jurisdictional claim, rather than fight it, appears influenced by the political environment and Musk's access to the Trump administration.

What legal options do the eight SpaceX workers have now?

The workers have limited options. They could attempt to appeal the NLRB's decision in federal court, though courts are generally deferential to agency interpretations of jurisdiction. They could pursue claims under the National Mediation Board's framework, though the NMB is designed for different types of disputes and workers. They could file state law suits alleging tort claims like breach of good faith, though Texas at-will employment law makes such suits difficult. They could attempt to organize their workplace for union representation, which would provide protections under the Railway Labor Act.

Could Congress fix this jurisdictional problem?

Yes, Congress could amend the relevant statutes to clarify which agencies regulate which industries and ensure workers in all sectors have consistent NLRB protection. Congress could explicitly exclude space launch operations from the Railway Labor Act, ensuring they fall under NLRB jurisdiction. Congress could amend the NLRA to explicitly extend protections to workers in emerging industries. Congress could require specialized regulatory agencies to defer to NLRB jurisdiction for labor matters. These legislative fixes would provide clarity and prevent agencies from negotiating away their jurisdictions based on political pressure.

Why is this precedent dangerous for other industries?

Once SpaceX succeeds with a jurisdictional argument, other companies will attempt similar strategies. A drone delivery company could argue FAA authority, an autonomous vehicle company could claim DOT authority, a biotech firm could invoke FDA jurisdiction. If the NLRB consistently accepts these arguments, its jurisdiction shrinks, and workers in emerging industries lose labor law protection. This creates incentives for companies to operate in multiple regulated areas specifically to claim jurisdiction elsewhere.

What does this case suggest about the future of the NLRB?

The case suggests the NLRB is vulnerable to political pressure and may not vigorously defend its jurisdiction when facing politically connected companies. The board appears willing to voluntarily cede authority rather than fight jurisdictional challenges, particularly when those challenges come from companies with administrative connections. This trend could lead to a gradual erosion of the NLRB's scope and reduced worker protections in high-growth industries.

Conclusion: A System Corroded by Politics

The NLRB's decision to drop its case against SpaceX for allegedly illegally firing workers is not a technical legal ruling about jurisdictional boundaries. It's a signal that the American labor law system is being corroded from within by political pressure, regulatory capture, and the concentration of political influence in the hands of wealthy individuals.

For over eight decades, the National Labor Relations Act provided a consistent framework for protecting worker rights. That framework wasn't perfect—it excluded agricultural workers, domestic workers, and supervisors. It left room for employers to retaliate against unionized workers through subtle means. But it established a clear principle: workers have a right to organize collectively and engage in concerted activity without fear of retaliation.

The SpaceX case demolishes that principle. It shows that when a company is politically connected, when its CEO has the administration's ear, when the company operates in an emerging regulatory area, the protections evaporate. An agency that was supposed to defend worker rights instead surrenders jurisdiction to avoid conflict.

What makes this more troubling than typical regulatory agency failures is that it happened voluntarily. The NLRB wasn't overruled by a court or defunded by Congress. The board chose to interpret its jurisdiction narrowly and defer to the National Mediation Board's assertion. That choice reveals the board's vulnerability to political pressure.

For workers in tech, aerospace, autonomous systems, artificial intelligence, and other emerging industries, the lesson is clear: you cannot rely on the NLRB to protect you. The legal framework that was supposed to protect your right to speak up and organize is being systematically dismantled through jurisdictional arguments and political pressure. You need to document everything, involve multiple coworkers in your actions, understand your state's employment law, and consult with employment attorneys before engaging in workplace activism.

For Congress, the lesson is that the current system requires clarification. Congress should explicitly address how labor law applies in emerging industries. Congress should ensure that specialized regulatory agencies don't usurp labor law jurisdiction. Congress should consider whether the NLRB needs structural protection against political pressure.

For society, the lesson is that regulatory systems require constant defense. Once you allow agencies to interpret their jurisdiction in politically convenient ways, you've opened the door to regulatory capture and systematic erosion of protections. The SpaceX case won't be the last time an agency surrenders jurisdiction or narrowly interprets its authority to avoid conflict with politically connected companies.

The question is whether Congress, courts, and ultimately workers will accept this corroded system or demand that our regulatory agencies actually fulfill their statutory mandates regardless of political pressure. The answer to that question will determine whether worker protections remain meaningful in the industries of the future.

Key Takeaways

For Workers: Monitor changes to regulatory jurisdiction over your industry. The NLRB's surrender of SpaceX jurisdiction shows that labor protections you assume you have may not actually apply. Consult employment attorneys and document workplace activism carefully.

For Companies: Jurisdictional arguments that successfully move labor disputes away from the NLRB to specialized regulators are attractive, but they set precedents that other companies will follow, potentially leading to Congressional action and stricter regulations.

For Policymakers: The SpaceX decision reveals vulnerabilities in agency independence and the need for clearer Congressional direction on jurisdictional boundaries. Leaving jurisdictional questions ambiguous invites regulatory capture and political pressure.

For the Labor Movement: Traditional organizing strategies may not work in emerging industries where jurisdictional questions are unresolved. Unions need to engage in legislative advocacy, not just workplace organizing.

For Regulatory Reform: This case shows that independent agencies need protection against political pressure. Simply having statutory authority doesn't prevent agencies from voluntarily surrendering that authority.

Related Articles

- FCC Accused of Withholding DOGE Documents in Bad Faith [2025]

- xAI Founding Team Exodus: Why Half Are Leaving [2025]

- xAI Co-Founder Exodus: What Tony Wu's Departure Reveals About AI Leadership [2025]

- Why Elon Musk Pivoted from Mars to the Moon: The Strategic Shift [2025]

- SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]

- Why Companies Won't Admit to AI Job Replacement [2025]

![NLRB Drops SpaceX Case: What It Means for Worker Rights [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nlrb-drops-spacex-case-what-it-means-for-worker-rights-2025/image-1-1770761213434.jpg)