The FCC's Document Transparency Crisis: What's Really at Stake

Last year, when Frequency Forward and investigative journalist Nina Burleigh filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Federal Communications Commission, they thought they were asking a straightforward question: What exactly was the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) doing inside the FCC?

Almost two years and nearly 2,000 pages of documents later, they're back in federal court with an accusation that cuts to the heart of government accountability: the FCC has withheld responsive documents "in bad faith," deliberately obscured communications, and failed to produce evidence of potential conflicts of interest that could reshape how the agency operates.

Here's what makes this particularly important. DOGE, headed by billionaire Elon Musk, was supposed to be a lean, cutting-edge government efficiency unit. Instead, its presence at the FCC has created what critics describe as an unprecedented entanglement: a regulatory agency overseeing a billionaire's companies (Space X, Tesla, and others) while that same billionaire's lieutenant runs the efficiency operation inside the agency itself.

This isn't just a procedural dispute about document management. It's about whether the public has any meaningful way to understand potential conflicts of interest that could influence how billions in spectrum licenses are awarded, how broadband infrastructure gets funded, and how telecommunications regulations get written. When government agencies can effectively hide documentation of these interactions, the entire system of checks and balances starts to crumble.

The stakes are enormous. We're talking about an agency that controls the allocation of wireless spectrum worth hundreds of billions of dollars. We're talking about broadband deployment rules that affect tens of millions of Americans. And we're talking about a situation where the transparency mechanisms designed to protect the public are, according to this court filing, being systematically undermined.

Let's break down what's actually happening here, why it matters, and what the implications are for government transparency going forward.

Understanding the DOGE Experiment at the FCC

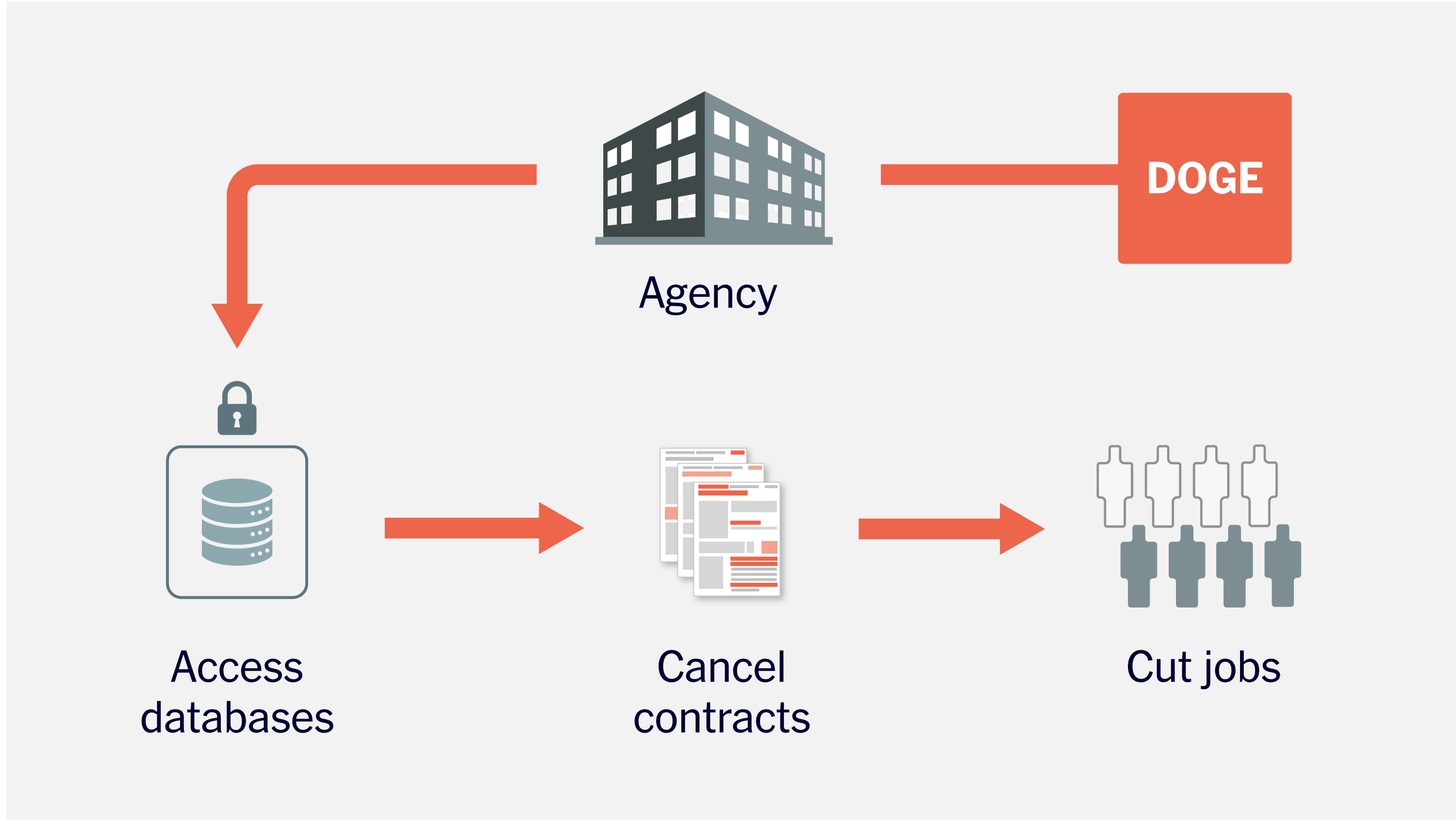

When DOGE operations launched, the arrangement seemed almost clinical in its simplicity. Federal employees from various departments would be temporarily assigned to work alongside DOGE operatives, tasked with identifying "waste, fraud, and abuse" within their respective agencies.

At the FCC, this manifested as the arrival of staffers like Tarak Makecha, a DOGE detailee from the Office of Personnel Management. According to the court filing, Makecha spent about two weeks at the FCC during his assignment. That might sound like a brief stint, but what he accessed during those two weeks is raising serious alarm bells.

Makecha requested and received what the filing describes as "a substantial amount of information from Commission staff including broadband mapping data and detailed personnel records regarding Commission employees." Think about what that means in practical terms. A temporary DOGE operative with unclear security clearances and undefined ethics obligations gained access to sensitive broadband infrastructure data and employee records.

Here's where it gets worse. The filing notes there's "no evidence that Makecha was ever actually 'onboarded' to the Commission or cleared required security or ethics checks prior to receiving such information." This isn't a minor administrative oversight. Access to broadband mapping data could inform strategic decisions about infrastructure deployment. Access to personnel records could be used to identify and potentially influence specific FCC staff members.

Makecha's financial disclosures showed he held stock in Tesla, Disney, and a telecommunications portfolio. That matters enormously. If he's making recommendations about FCC policies while holding Tesla stock and knowing his boss Elon Musk's financial interests, that's not just a conflict of interest, it's a structural problem with how DOGE was implemented in regulatory agencies.

The FCC didn't produce any documents discussing Makecha's ethics approvals or agreements to recuse himself from certain matters. When you're dealing with someone who has financial interests in the companies being regulated, you'd expect robust documentation of how those conflicts are being managed. The absence of that documentation suggests either it doesn't exist, or it's being withheld.

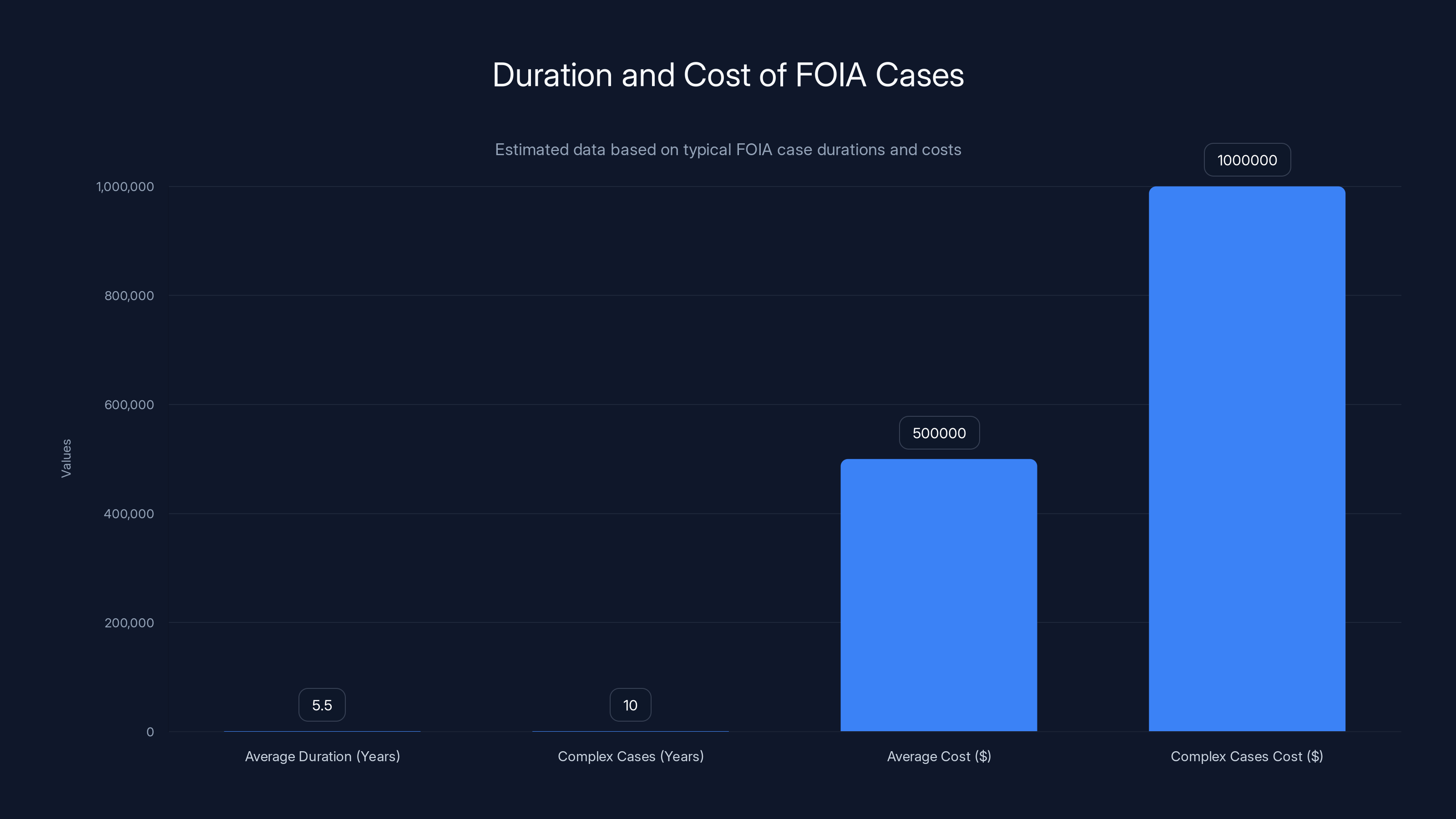

FOIA cases typically take 4-7 years, with complex cases extending over a decade. Costs can exceed $500,000, doubling for complex cases. Estimated data.

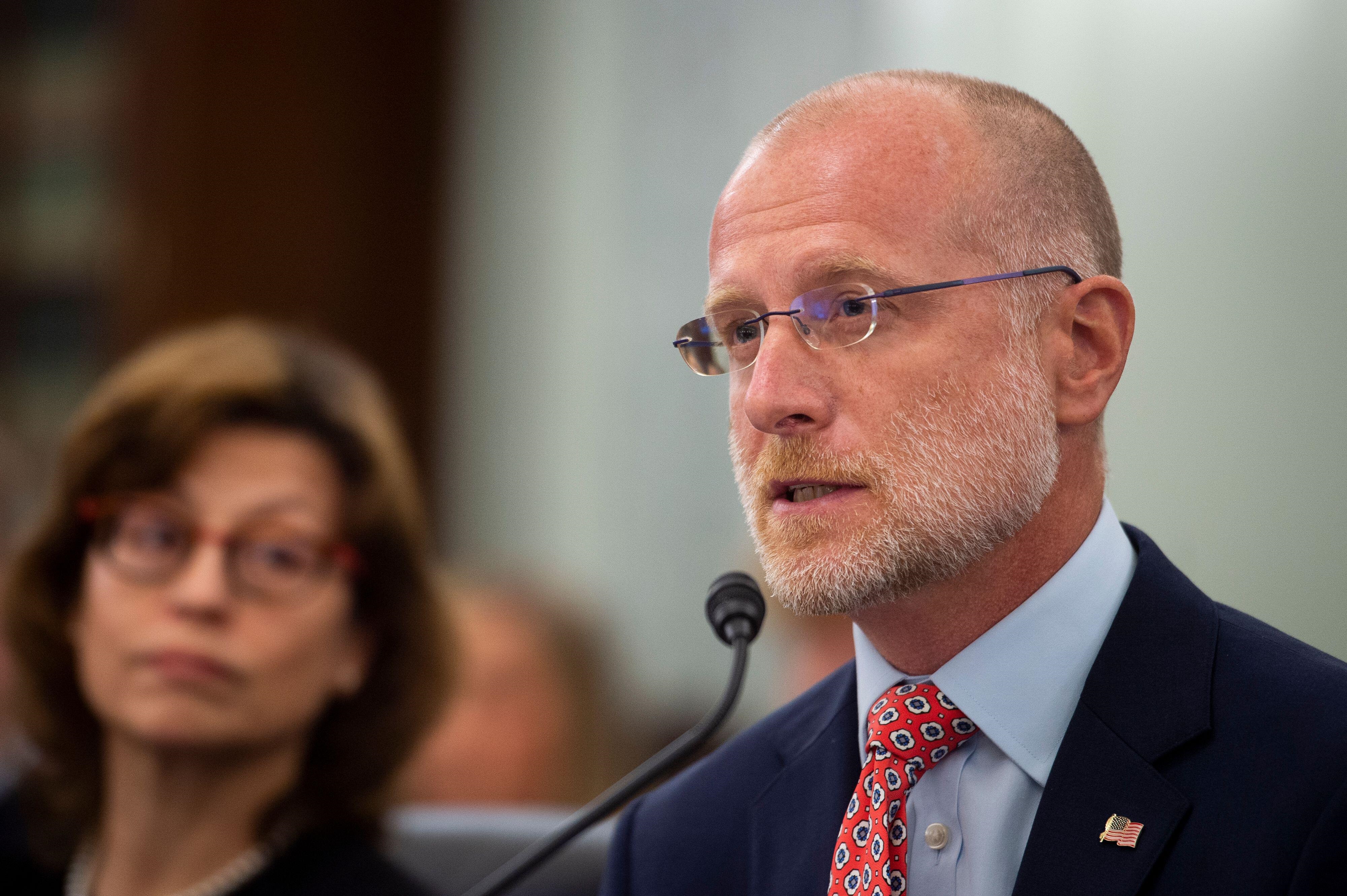

The Brendan Carr Connection and Undisclosed Visits

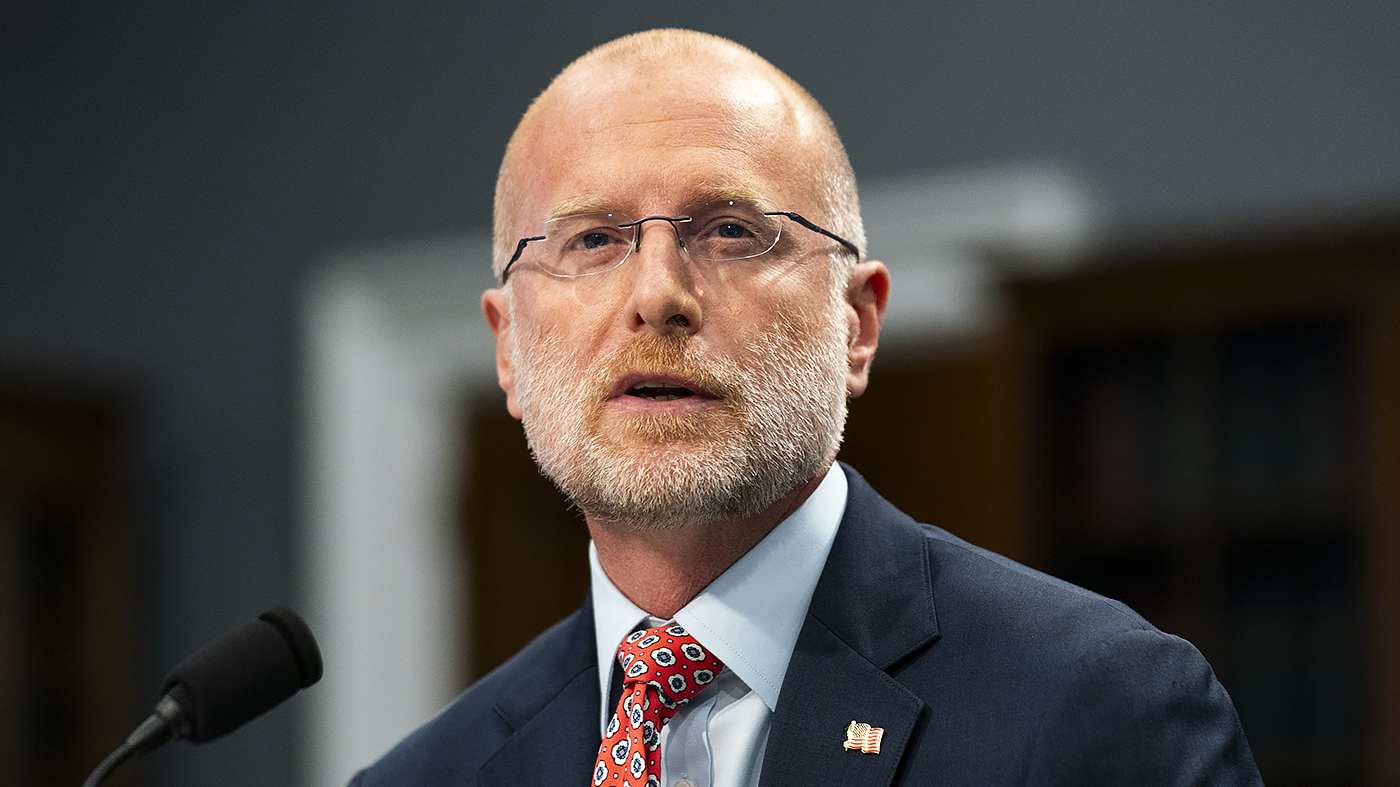

If the Makecha situation raises questions about DOGE operatives inside the FCC, the allegations about FCC Chair Brendan Carr raise questions about the agency's top leader and his interactions with Musk-affiliated companies.

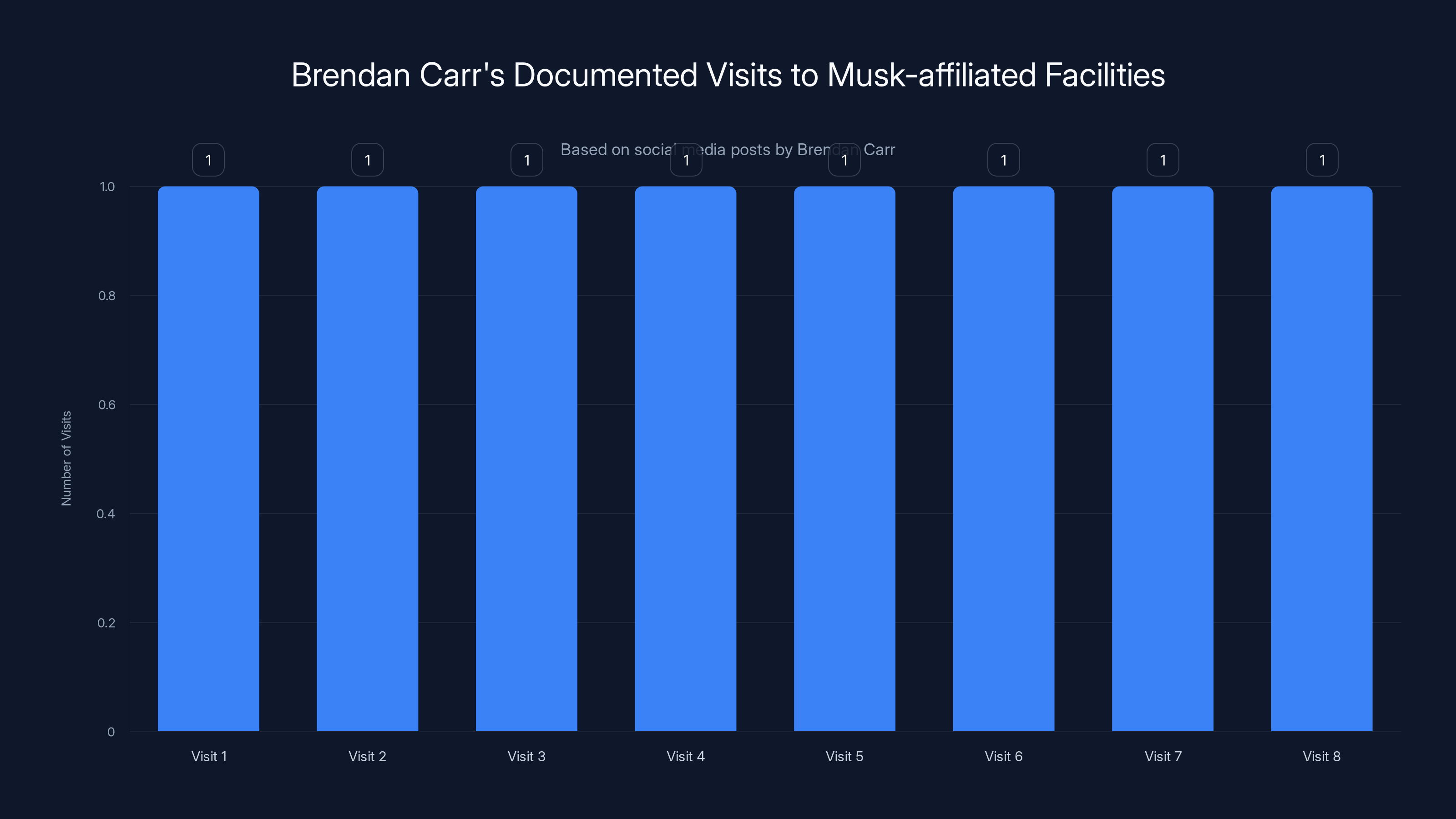

The court filing identifies eight posts Carr made on X (formerly Twitter) within the period covered by the FOIA request. Each of these posts shows him visiting what appears to be either a Space X or Tesla facility. These aren't hypothetical visits or secret meetings. They're publicly documented on social media. Carr was posting about being at these locations, presumably because he thought it was worth sharing with his followers.

But here's the problem: When Frequency Forward and Burleigh asked the FCC to produce documents about Carr's office planning these trips, about travel itineraries, about calendar events, about the purpose of the visits, the agency refused to produce them. Or more accurately, the agency claims such documents don't exist in any retrievable form.

Let's think about how federal agencies actually work. When a chair or senior executive travels, there's almost always documentation. Someone has to book the trip. Someone has to arrange transportation or approve personal vehicle use. There might be advance briefing materials prepared. There might be meeting agendas or notes afterward. The idea that the FCC has eight publicly documented trips by its chair to Musk-affiliated facilities but zero internal planning documents strains credulity.

The only email in the entire production from Carr himself is fully redacted. The filing describes it as "an apparent response to how the agency should respond to a variety of press requests, including one from The Verge about DOGE employees found in its staff directory." In other words, when a reporter asks about DOGE at the FCC, and the chair responds to that inquiry, that response is completely blacked out.

Why would communication about how to respond to press inquiries be fully redacted? That's a difficult position to justify under FOIA law, which has narrow exemptions for deliberative process documents. A chair's response to "how should we answer this journalist" isn't exactly confidential strategy in the way that, say, legal advice or personnel decisions would be.

The lack of text message documentation is equally suspicious. The emails that were produced reference text exchanges between officials. Text messages don't automatically delete or disappear. They're stored on government devices and accessible through discovery. The fact that the FCC claims to have no responsive text messages, despite email references to text exchanges, suggests either systematic deletion or systematic non-production.

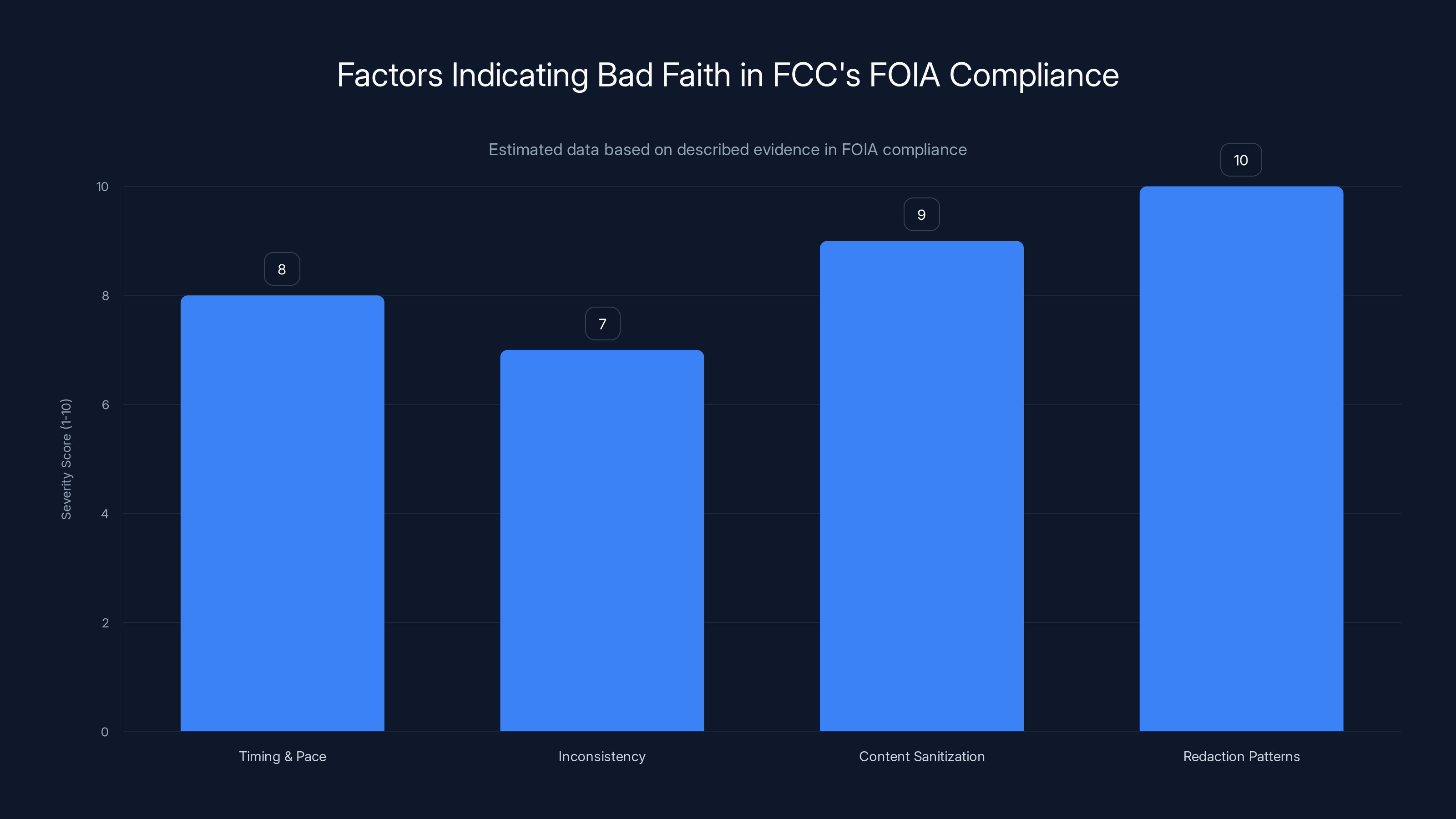

Estimated data suggests that the pattern of redactions and non-production is the most severe indicator of bad faith in the FCC's FOIA compliance.

The Bad Faith Allegation: What the Evidence Shows

Attorney Arthur Belendiuk's filing uses the phrase "bad faith" three times when describing the FCC's FOIA compliance. That's a legal term with specific meaning in administrative law, and it's serious.

Bad faith in the FOIA context means the agency isn't just making honest mistakes or having genuine disagreements about what's responsive. It means the agency is deliberately obstructing disclosure, withholding documents it knows are responsive, or misrepresenting what it has or hasn't produced.

What evidence supports this characterization? Several things pile up together to create a pretty damning picture.

First, there's the timing and pace. The FOIA request was filed over a year ago. The FCC has produced nearly 2,000 pages of documents, many of them heavily redacted. Some documents were produced only after court pressure. This pattern of slow, grudging production with significant redactions is consistent with agencies that don't want to disclose but are trying to minimize the appearance of non-compliance.

Second, there's the inconsistency. The FCC produced some emails about DOGE activities and some information about Carr's visits. This establishes that responsive documents exist in the system. But it also means when the FCC says certain documents don't exist or can't be found, that claim becomes harder to believe. If they found some documents about these topics, why can't they find others?

Third, there's the content of what was produced. The emails that made it through are "sanitized," as Belendiuk describes them. This suggests they've been heavily edited or had key details removed. Someone at the FCC made decisions about what information was okay to produce and what needed to be hidden, even after the documents were deemed responsive enough to release in edited form.

Fourth, and perhaps most compellingly, there's the specific pattern of redactions and non-production. The only email from Carr is completely blacked out. The responses to Verge reporter inquiries about DOGE are hidden. Documents about ethics clearances for temporary DOGE staff are absent. Travel and meeting arrangements are unlocatable. Documents about text exchanges referenced in emails aren't produced.

When redactions and non-productions cluster around topics that directly implicate potential conflicts of interest, a pattern emerges. It suggests not random incompetence but deliberate filtering of information.

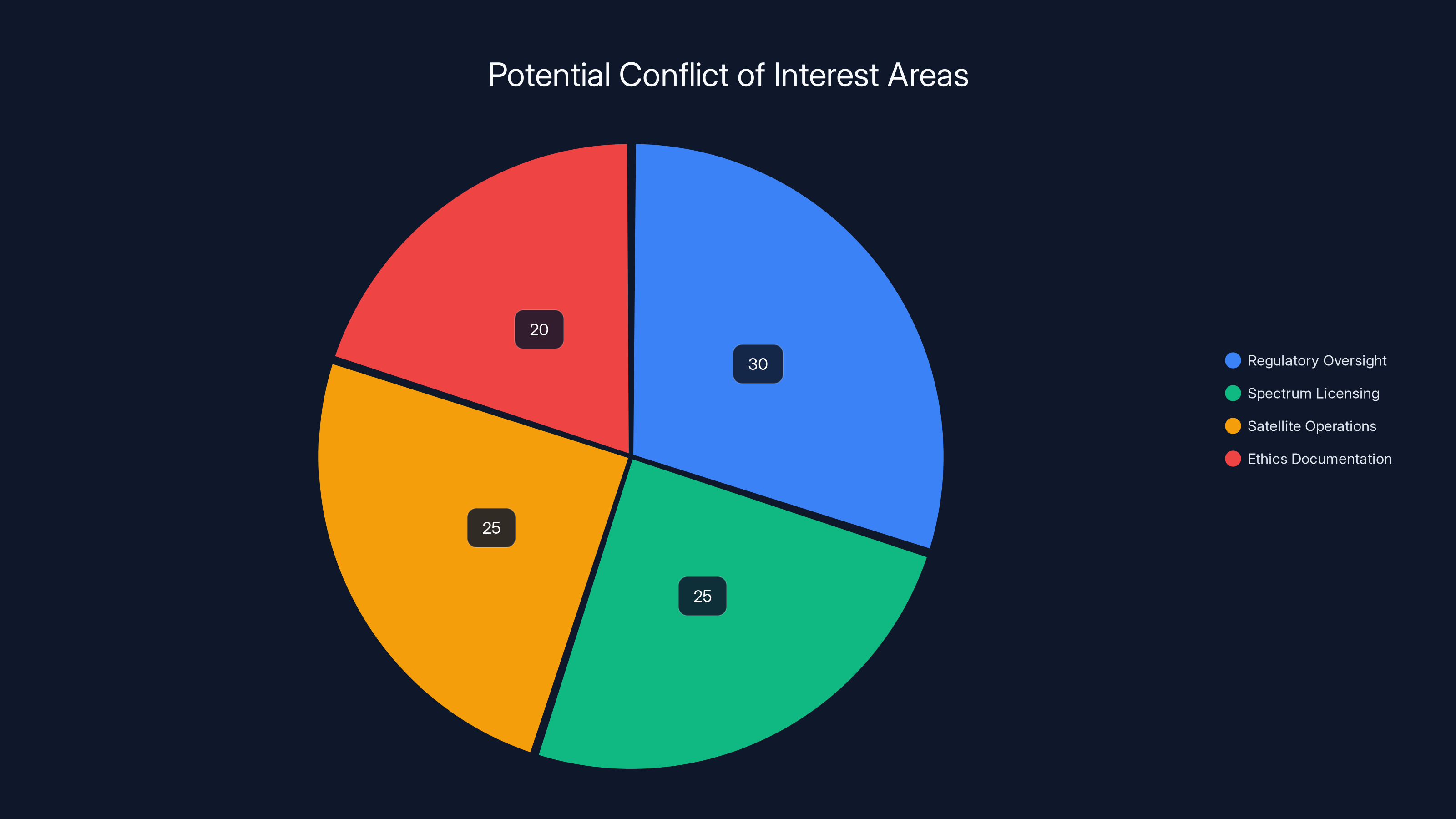

The Conflict of Interest Question That Nobody's Answering

Underneath all of this document wrangling is a more fundamental question: Is there a conflict of interest when the head of DOGE, a billionaire whose company Space X is heavily regulated by the FCC, has operatives inside that agency?

Musk isn't just some random billionaire being regulated. Space X operates a massive satellite internet constellation called Starlink, which the FCC has authorized and oversees. Space X also uses spectrum licenses granted by the FCC. The FCC also has authority over whether Space X complies with various regulations. It's a direct, ongoing regulatory relationship.

DOGE claims to be focused purely on identifying inefficiencies. But could a DOGE operative with financial interests in telecom or aerospace recommend that the FCC eliminate oversight mechanisms that Musk finds onerous? Could they suggest streamlining approval processes in ways that benefit Musk's companies? These aren't paranoid hypotheticals. They're the actual mechanics of how regulatory capture happens.

The reason conflict of interest disclosures and ethics clearances exist is precisely to prevent this kind of situation. When someone with financial interests in regulated companies has access to regulatory processes and data, institutions need to have documented safeguards. They need to have records of who approved that access, what limitations were placed on it, and what subsequent recusals were required.

Frequency Forward and Burleigh's argument is straightforward: You can't evaluate whether there's an actual conflict of interest problem without seeing the documentation of how these conflicts were supposedly managed. If the FCC had robust ethics processes in place, wouldn't they want to show them? Wouldn't they want to demonstrate that despite the appearance of a conflict, they had it all handled responsibly?

The fact that the FCC is withholding or can't locate this documentation creates exactly the opposite impression. It makes people wonder what they're hiding.

Brendan Carr documented eight visits to Musk-affiliated facilities on social media, yet no internal planning documents were found. Estimated data based on social media posts.

The Precedent This Sets for Government Transparency

This isn't just about DOGE at the FCC. It's becoming a template for how other agencies might operate with DOGE staff embedded inside them.

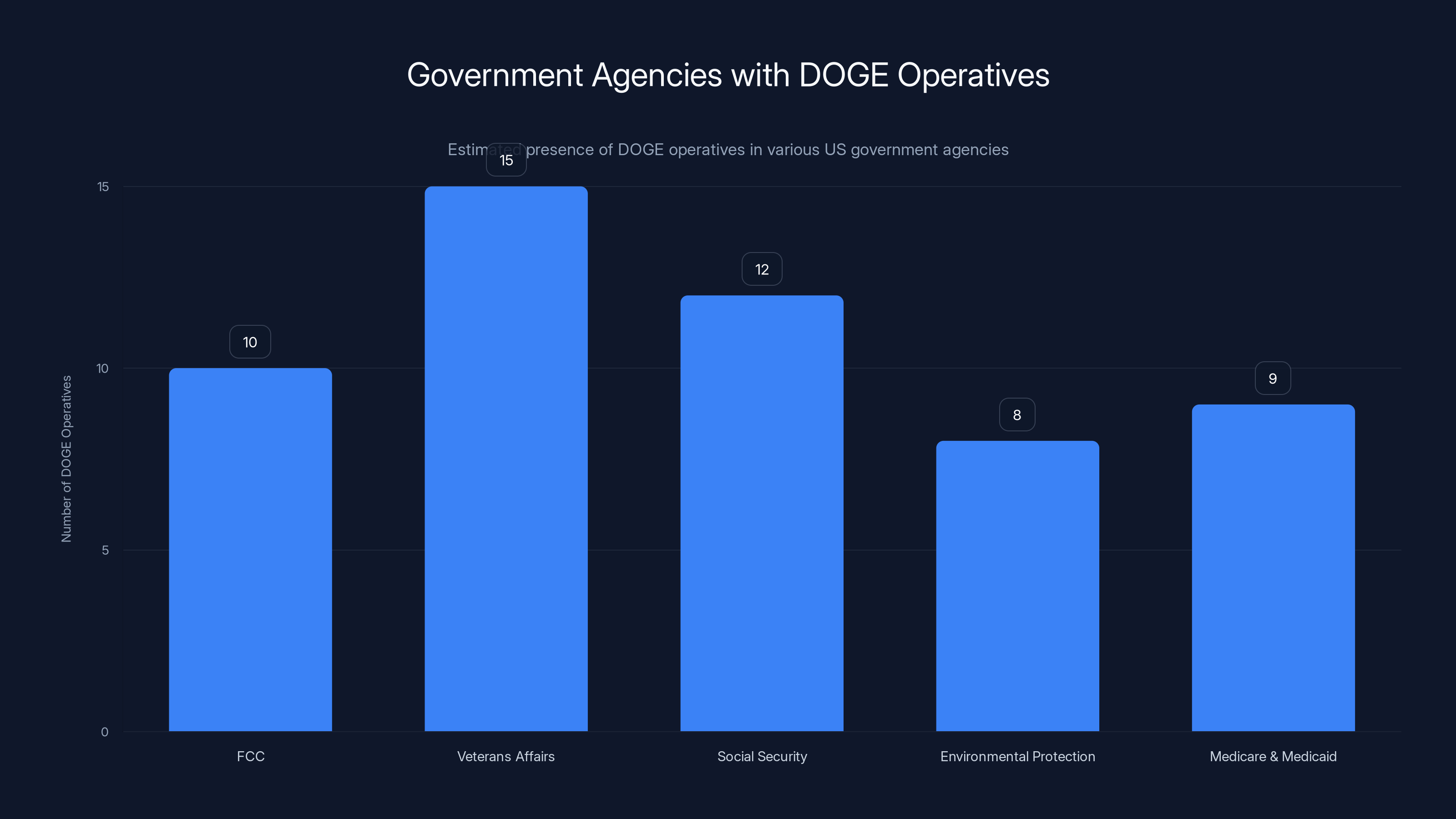

The Department of Veterans Affairs has DOGE operatives. The Social Security Administration has them. The Environmental Protection Agency has them. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has them. If the FCC can get away with producing heavily redacted documents, conducting incomplete searches, and claiming responsive documents don't exist, other agencies will notice.

Transparency advocates worry that this becomes the new standard. Temporary operatives from an executive efficiency office get access to sensitive data with minimal oversight. When anyone asks about what happened, the agency can rely on broad redactions and creative document interpretation to limit disclosure. The system becomes less accountable, not more.

The courts have a responsibility here to draw a line. If the FCC's FOIA compliance is accepted as adequate despite the glaring gaps and inconsistencies, it sends a signal that agencies don't need to work very hard at transparency when politically powerful interests prefer opacity.

Breaking the principle of bad faith FOIA compliance is important because it's one of the last mechanisms the public has to understand what's happening inside their government. When that mechanism fails, there's very little left.

The Practical Implications of Withheld Information

Some might argue this is all theoretical. So DOGE had staff at the FCC. So the chair visited Musk facilities. So what? What practical harm comes from not having complete documentation?

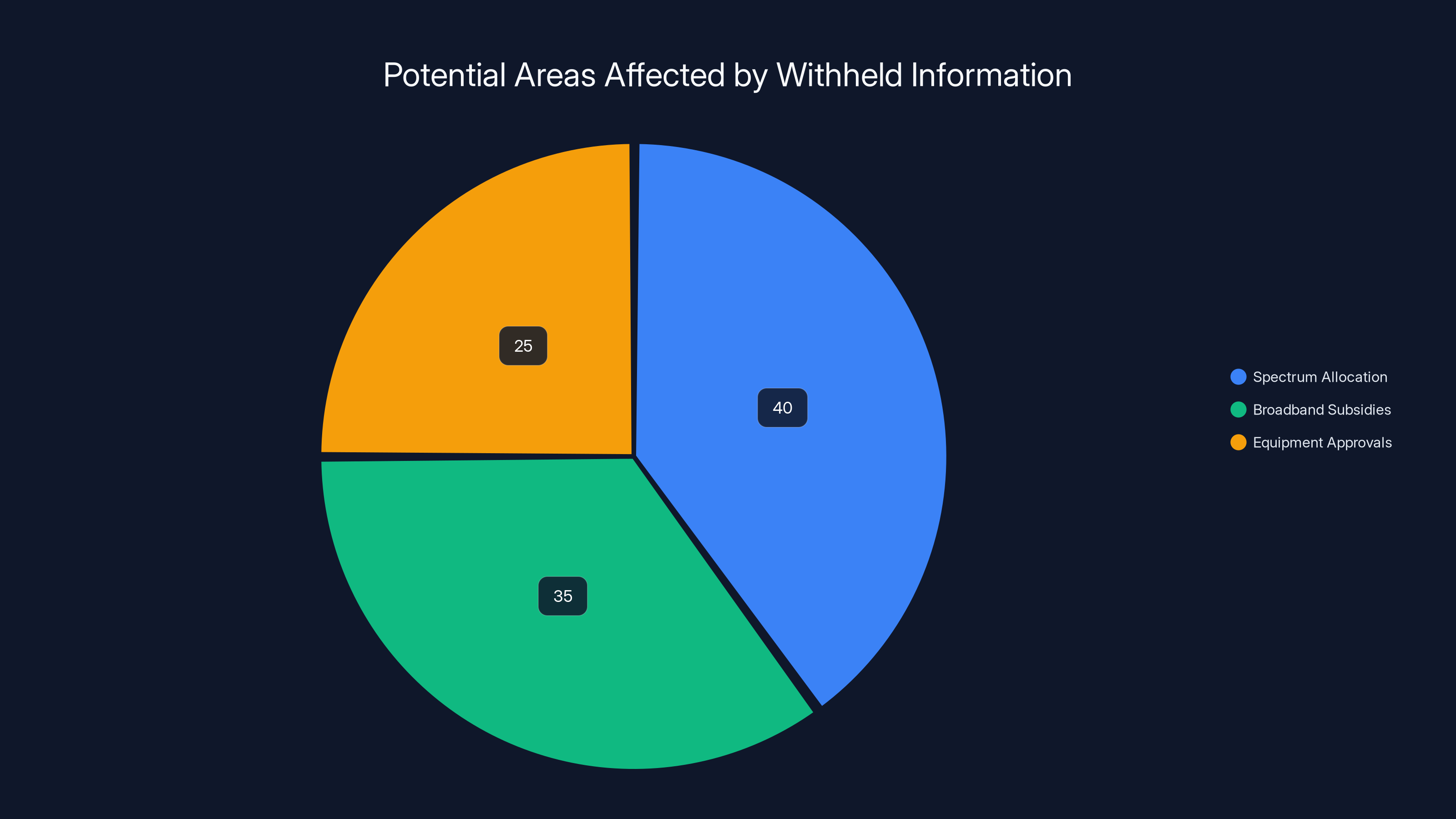

Here's what could be at stake. The FCC makes decisions about spectrum allocation, broadband infrastructure subsidies, and equipment approvals. These decisions involve billions of dollars. If the chair is meeting with Musk, and there's no documented discussion of what was discussed, what was decided, or what impact those meetings might have had on subsequent FCC actions, that creates a kind of informational darkness.

Consider broadband policy as a concrete example. The FCC can direct federal funding toward various broadband deployment approaches. Some of those approaches might favor satellite internet (Space X's business) over terrestrial options. Some might emphasize rural deployment (where Starlink has marketing advantages) over urban areas. If Carr met with Musk, and they discussed broadband policy, and there's no record of it, how can anyone evaluate whether the FCC's subsequent decisions were made on the merits or influenced by these off-the-books communications?

Or consider spectrum. The FCC regularly holds auctions for valuable spectrum licenses. If Carr visited Space X and discussed spectrum policy with Musk, and there's no documentation of it, was that visit about understanding Space X's needs? About getting Musk's input on regulatory policy? Neither scenario is ideal, but at least with documentation you could see what the relationship actually was.

Without documentation, you're left with suspicion. And suspicion about government is generally worse for public trust than actual disclosed conflicts, which can at least be managed and monitored.

Estimated data shows potential conflict areas with regulatory oversight and spectrum licensing as major concerns. The lack of ethics documentation exacerbates these issues.

The Document Production Process and Where It Failed

FOIA requests don't process themselves. An agency receives a request, identifies the responsible offices, searches their files, reviews documents for exempt information, and produces what doesn't fall under exemptions. It's a mechanical process, and it has failure points.

In the FCC's case, Belendiuk's filing suggests failures at multiple stages. The initial search may not have been comprehensive. Documents may not have been properly classified or flagged as responsive. The review for exemptions may have been overly broad, with staff erring on the side of redaction rather than disclosure.

The hiring of a contractor to conduct FOIA work is common, and it can either improve the process (by adding resources) or degrade it (by adding a layer of bureaucracy and potential miscommunication). Without seeing the FCC's FOIA procedures and search methodologies, it's hard to diagnose exactly where things went wrong.

But the filing provides some clues. The fact that Carr himself produced only one fully redacted email is suspicious. A chair of a major agency usually has extensive email records. That one email doesn't tell us he only wrote one email during the relevant period. It tells us that either the search didn't find the others or the others were deemed not responsive.

Given that the request specifically asked for documents about Carr's visits to Musk facilities, and Carr publicly posted about these visits, emails regarding planning or scheduling those visits would seem clearly responsive. The failure to produce them suggests either an insufficient search or an overly aggressive interpretation of exemptions.

What Discovery Could Reveal

Frequency Forward and Burleigh are asking the court to allow discovery, which would give them the ability to depose FCC officials, demand production of documents under judicial oversight, and potentially compel the agency to explain the gaps in what's been produced.

Discovery is the nuclear option in FOIA litigation. It's much more intrusive than the standard FOIA administrative process. An agency can't just provide what it decides to produce. It has to respond to specific questions and produce everything responsive to those questions under penalty of perjury.

What might discovery reveal? Several categories of information become much harder to hide under discovery.

First, it could establish how the FCC actually conducts FOIA searches. What are the standard procedures? Which offices are contacted? How thoroughly are email systems and messaging platforms searched? Are any files systematically excluded? Depositions of FOIA officers would have to answer these questions truthfully.

Second, it could establish what the FCC actually has. Under discovery, the government can't just claim documents don't exist. It has to explain where they looked, why they're confident nothing was missed, and what happened to documents that were created but no longer exist. If Carr's calendar shows a meeting that no documents reference, that's a problem.

Third, it could establish intent. Were decisions made to redact or withhold information deliberately, or were they the result of unclear policies or bad judgment? Intent matters in bad faith analysis. If the FCC deliberately chose not to search email archives to avoid finding responsive documents, that's bad faith. If they just had a bad procedure that nobody fixed, that's negligence but maybe not bad faith.

Fourth, it could establish the nature of the withheld information. Right now, the public sees heavily redacted documents and gaps. Discovery could pull back the curtain on what's actually being hidden and why. In many cases, when documents are revealed in discovery, they turn out to be less sensitive than the redactions suggested.

Estimated data suggests that multiple US government agencies have embedded DOGE operatives, potentially impacting transparency standards.

The Historical Context of FOIA Disputes

FOIA compliance has been a persistent problem in federal agencies for decades. The statute is over 50 years old, but compliance remains inconsistent. Agencies chronically miss deadlines, produce heavily redacted documents, and claim exemptions that broad-minded courts often question.

What's different about this particular dispute is the political sensitivity and the profile of the individuals involved. Musk is the world's wealthiest person and holds significant political influence. Carr is a Trump appointee serving as FCC chair during a period of significant regulatory change. DOGE is a high-profile executive initiative. Everything about this situation has elevated stakes.

Previous FOIA disputes have often involved military or intelligence agencies claiming national security exemptions. This one involves communications with a billionaire businessman whose companies benefit directly from FCC regulatory decisions. The conflict of interest stakes are different.

Courts have shown increasing skepticism of broad FOIA non-compliance in recent years. The presumption of openness built into FOIA is being reasserted after decades of agency expansiveness with exemptions. If the courts are in a mood to enforce FOIA more strictly, the FCC's approach here could face serious judicial skepticism.

The Broader Questions About DOGE and Regulatory Agencies

Separate from the FOIA compliance question is a bigger structural question: Should efficiency operations have this kind of access to regulatory agencies?

DOGE was created with the rationale that federal government is bloated and inefficient. Some of that criticism is fair. Federal agencies do sometimes maintain outdated processes and unnecessary positions. But efficiency isn't the only value in government. Oversight, integrity, and transparency matter too.

When DOGE operatives get access to regulatory data and personnel records without clear oversight, you're trading one kind of efficiency (eliminating what Musk deems wasteful) for the loss of another kind of efficiency (the efficient operation of regulatory safeguards).

The question isn't whether some government waste should be eliminated. It's whether that elimination should happen through operatives who have financial interests in the regulated companies and undefined ethics obligations.

Future administrations might use the DOGE model differently. But the precedent being set here matters. If DOGE can operate inside agencies with minimal documentation and oversight, that becomes available to whoever is in charge next.

Estimated data shows that spectrum allocation, broadband subsidies, and equipment approvals are key areas potentially affected by undocumented FCC discussions with SpaceX.

The Role of the Courts in Enforcing Transparency

Ultimately, this dispute will probably be resolved by a federal judge. That judge has significant power to shape what information the public gets to see.

If the court allows discovery, the FCC will face much more intensive scrutiny of its document production and search procedures. That's likely to result in more documents being produced. If the court rejects discovery, the case ends with the FCC's FOIA production as it stands, heavily redacted and incomplete.

The court's decision will also send a signal about how seriously federal courts take FOIA compliance. Are agencies expected to conduct thorough, good-faith searches, or can they get away with claiming documents don't exist without extensive proof? Are broad redactions acceptable, or do agencies need to justify each one specifically?

Based on recent trends in FOIA litigation, courts have been pushing back against overbroad exemptions and incomplete searches. The judges who have developed expertise in FOIA disputes have become more skeptical of agency claims and more willing to order broader disclosure than they were decades ago.

That institutional learning might work in Frequency Forward and Burleigh's favor. Their allegations of bad faith aren't novel, but the context is high-profile enough that courts might take them seriously.

Implementation Challenges and Practical Realities

Even if the court agrees that the FCC has engaged in bad faith FOIA non-compliance and orders discovery, implementing that will be complicated.

FOIA cases can drag on for years. Depositions take time. Document production under discovery can be massive. The FCC might have to hire outside counsel and FOIA specialists just to manage the discovery process. The costs add up quickly.

There's also the question of what happens if documents don't exist. If Carr really doesn't have extensive email records about his visits to Musk facilities, that's not something discovery will create. It just means either the documents were deleted or the communications happened through channels (like in-person meetings or phone calls) that don't leave written records.

In that scenario, discovery reveals absence rather than presence. It confirms that the FCC wasn't documenting interactions that should have been documented. That's still important information, but it's different from discovering hidden documents that implicate Carr or DOGE operatives.

What Broader Implications This Has for Government Accountability

If Frequency Forward and Burleigh win this case, and if courts order discovery and compel broader document production, it establishes a precedent that FOIA compliance requires more than the FCC has been providing.

That precedent could affect how other agencies handle transparency requests going forward. It could signal that "documents not found" claims will be scrutinized. It could mean that more communications around sensitive political relationships get preserved and produced.

But it also raises questions about what transparency is for. Is it about keeping politicians and appointees accountable? Is it about preventing corruption? Is it about allowing advocacy groups to research policy decisions? The answer probably involves all of those things, but different people prioritize them differently.

From the FCC's perspective, transparency requirements can feel like obstacles to efficient governance. Officials have to be careful about what they write down. Meetings have to be documented. Every communication could become public. From the public's perspective, that's exactly the point. Officials should be careful about what they write down when they're making decisions that affect millions of people.

The tension between these perspectives is fundamental to how government works in a democracy. FOIA and discovery processes are the mechanisms for resolving that tension in favor of transparency.

The Specific Redactions and What They Suggest

One of the most telling elements of Belendiuk's filing is his detailed description of what's been redacted and what's missing entirely.

The fact that Carr's single email is completely blacked out is noteworthy. Under FOIA law, agencies can redact information that's exempt, but they have to explain the exemption being applied. If a document is entirely redacted, the agency has to say why the entire document qualifies for an exemption. That's a high bar.

Exemptions under FOIA are narrow. They include things like classified national security information, attorney-client privileged communications, trade secrets, and personal privacy information. A chair's email about how to respond to a reporter inquiry doesn't obviously fall into any of those categories.

The complete redaction suggests either that the entire email is attorney-client privileged, which would be unusual for a response about press inquiries, or that the FCC is interpreting exemptions very broadly.

The missing documents about ethics clearances are equally suggestive. If Makecha went through proper ethics approval processes, the FCC should have documented them. Documents showing compliance are usually uncontroversial. If they're missing, it either means the processes weren't documented, or the processes didn't happen, or the documents are being withheld.

None of those scenarios reflects well on the FCC's handling of DOGE staff.

Moving Forward: What Comes Next in the Case

The court will now have to decide whether to grant Frequency Forward and Burleigh's motion to allow discovery. This decision won't happen immediately. The FCC gets to file a response to the motion, arguing why discovery shouldn't be allowed. Then the court will rule.

If discovery is granted, the pace of the case will accelerate. The FCC will have to produce documents systematically in response to specific discovery requests. Depositions will be scheduled. Interrogatory responses will be due. The whole process could take 6 to 12 months, depending on how complex the document production becomes.

If discovery is denied, the case essentially ends in a negotiation. The FCC might be ordered to do supplemental FOIA searches based on the court's findings about the inadequacy of the initial search. Or the case might just conclude with the heavily redacted documents the FCC has produced.

Either way, this case is going to have implications beyond DOGE and the FCC. It will establish precedents about how seriously courts take FOIA compliance when politically sensitive matters are involved.

Conclusion: The Stakes of Government Transparency

At its core, this case is about whether government agencies can hide their activities when those activities involve potential conflicts of interest. When a regulatory agency oversees a billionaire's companies, and that billionaire's representatives are working inside the agency, transparency becomes essential.

Frequency Forward and Burleigh's lawsuit is asking a straightforward question: What happened? What did DOGE do at the FCC? What did the chair discuss with Musk? What documents exist about these interactions?

The FCC's response has been: We don't have those documents, or they're too sensitive to share, or they're covered by exemptions. We've produced what we can.

The court will have to decide whether that response is acceptable or whether the public deserves more information. That decision will ripple far beyond the FCC. It will shape how all federal agencies handle transparency when politically sensitive matters are involved. It will determine whether FOIA remains a meaningful tool for public accountability or becomes something much weaker.

The document dispute might seem technical and obscure. But it's about something profound: whether government in a democracy is genuinely accountable to the people it serves, or whether that accountability is just theater while the real decisions get made in undocumented meetings and withheld communications.

What happens in this courtroom matters far more than the headlines suggest.

FAQ

What is the FOIA and how does it apply to this FCC case?

The Freedom of Information Act is a federal law requiring government agencies to provide public access to their records, with limited exemptions for national security, personal privacy, and similar categories. In the FCC case, Frequency Forward and journalist Nina Burleigh filed a FOIA request asking for documents about DOGE activities and FCC Chair Brendan Carr's visits to Musk-affiliated facilities. The FCC's production of heavily redacted and incomplete documents led to the bad faith allegation.

Why is Elon Musk's involvement with DOGE at the FCC considered a conflict of interest?

Musk is the controlling owner of Space X, which is directly regulated by the FCC through spectrum licenses, satellite operations, and broadband services (Starlink). DOGE, headed by Musk, placed operatives inside the FCC with access to sensitive data and regulatory processes. This creates a structural conflict where Musk's financial interests in Space X could influence how DOGE recommendations at the FCC are implemented, particularly around regulatory burden and approval processes.

What documents is the FCC accused of withholding?

The FCC is accused of withholding or failing to adequately search for documents related to FCC Chair Brendan Carr's visits to Musk-affiliated facilities, ethics clearances and onboarding documents for DOGE temporary staff like Tarak Makecha, internal planning and calendar documents for Carr's trips, text messages referenced in emails but never produced, and communications about how to respond to press inquiries regarding DOGE presence at the FCC.

What does "bad faith" mean in the context of FOIA compliance?

Bad faith FOIA non-compliance means an agency is not making a genuine good-faith effort to locate and produce responsive documents. It includes deliberately withholding documents the agency knows are responsive, conducting incomplete searches to avoid finding documents, misdescribing what was produced, or misrepresenting what documents exist. This is distinct from honest disagreements about exemptions or genuine inability to locate records.

What is discovery in a FOIA lawsuit, and why is it significant?

Discovery is a legal process that allows parties to compel production of information and testimony under oath. In FOIA litigation, discovery gives plaintiffs the ability to depose FCC officials, demand extensive document production under judicial oversight, and require the agency to explain gaps in what was produced. It's more powerful than the standard FOIA administrative process because an agency cannot simply decide what to produce.

What could happen if the court grants discovery in this case?

If discovery is granted, the FCC would face intensive scrutiny of its FOIA search procedures, document management practices, and decision-making about redactions. Officials would have to be deposed and answer questions under oath about how documents were searched for and reviewed. More complete document production would likely result. The case could take 6 to 12 months or longer, and the FCC would incur significant legal costs managing the discovery process.

How could this case affect transparency practices at other federal agencies?

If the court finds the FCC engaged in bad faith FOIA non-compliance and orders discovery, it establishes a precedent that federal courts will scrutinize agency transparency claims skeptically. Other agencies would face similar pressure to conduct more thorough searches, justify redactions more carefully, and avoid the pattern of claiming documents don't exist when some responsive documents have been produced. The case could strengthen FOIA enforcement government-wide.

What are the implications if documents about Carr's visits to Musk facilities truly don't exist?

If discovery reveals that the FCC genuinely has no documents about planning or discussing Carr's publicly posted visits to Musk-affiliated facilities, that itself becomes a significant finding. It would indicate the FCC is not documenting high-level visits to regulated companies, which is a governance and transparency failure. It would suggest either deliberate non-documentation or absence of internal communication about visits that should have been discussed.

How long does a case like this typically take to resolve?

FOIA litigation typically takes 4 to 7 years from initial request to final resolution. If discovery is granted, this case could take several more years. The process involves motion practice, discovery disputes, deposition preparation, and potentially appeals. Complex cases involving multiple agencies or sensitive political matters often extend beyond 10 years from initial request to final court decision.

What is DOGE and why was it placed inside the FCC?

The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is an executive office created to identify and eliminate what Musk considers waste, fraud, and abuse in federal agencies. DOGE placed temporary operatives inside various agencies, including the FCC, to analyze operations and recommend changes. The practice is controversial because temporary appointees from an executive efficiency office gained access to sensitive data and regulatory processes with unclear oversight and ethics management.

Key Takeaways

- The FCC has been accused of withholding documents about DOGE activities 'in bad faith,' producing nearly 2,000 heavily redacted pages but failing to deliver responsive documents about FCC Chair Carr's visits to Musk facilities

- DOGE operatives like Tarak Makecha gained access to sensitive broadband mapping data and FCC personnel records with no documented ethics clearances or security vetting, creating unprecedented conflict-of-interest risks

- Eight publicly posted visits by FCC Chair Carr to SpaceX or Tesla facilities have no corresponding internal FCC documents for planning, itineraries, or discussions, suggesting either systematic non-documentation or deliberate withholding

- If courts grant discovery in this case, the FCC will face intensive scrutiny of its FOIA search procedures, and more complete document production will likely result, setting precedents for government-wide transparency enforcement

- This dispute has implications far beyond DOGE and the FCC: it will establish whether federal agencies can hide politically sensitive activities involving conflicts of interest or whether transparency mechanisms remain enforceable checks on government power

Related Articles

- Why Elon Musk Pivoted from Mars to the Moon: The Strategic Shift [2025]

- SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]

- State Department Deletes X Posts Before Trump's Term: What It Means [2025]

- Elon Musk's Orbital Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- SpaceX's Starbase Gets Its Own Police Department: What It Means [2025]

- Space-Based AI Compute: Why Musk's 3-Year Timeline is Unrealistic [2025]

![FCC Accused of Withholding DOGE Documents in Bad Faith [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fcc-accused-of-withholding-doge-documents-in-bad-faith-2025/image-1-1770673096410.jpg)