Why Companies Won't Admit to AI Job Replacement: The Transparency Gap [2025]

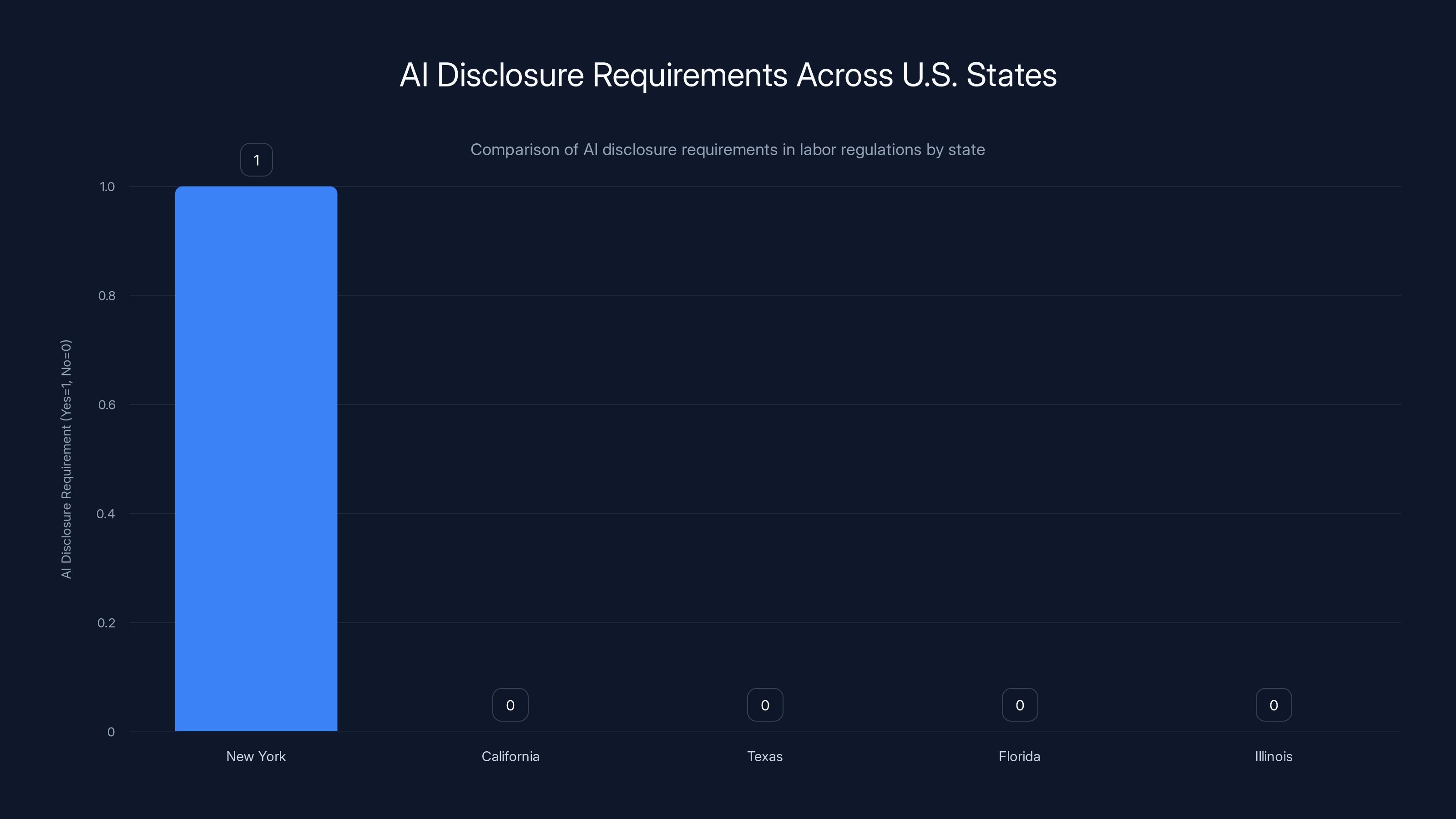

Last year, New York implemented something unprecedented: a requirement for companies to admit when they're cutting jobs because of artificial intelligence. It seemed like a straightforward solution to a murky problem. Workers want to know if AI is coming for their jobs. Policymakers want data on labor market shifts. Companies claim they're being thoughtful about automation.

So New York asked them directly.

As of now, zero companies have admitted it.

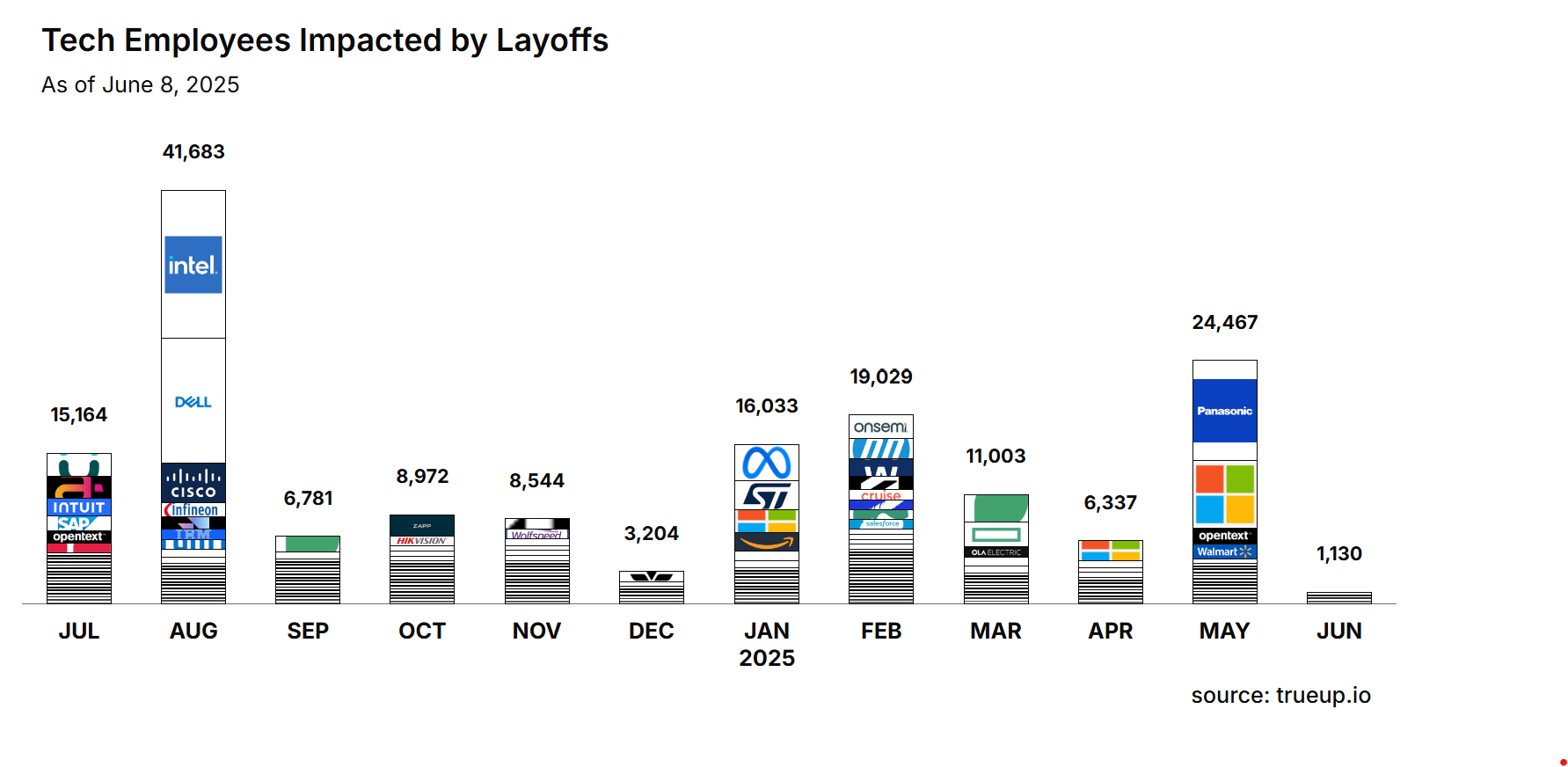

Over 160 employers in New York state have filed notices of mass layoffs since the requirement rolled out. That's nearly 28,300 affected workers across filings that include household names like Amazon, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley. All of them selected reasons for their cuts. Bankruptcy. Relocation. Merger. Economic conditions. But when given an explicit option to mark "technological innovation or automation" as the culprit, every single company looked the other way.

This isn't because AI hasn't been laying people off. The opposite is true. What it reveals is far more interesting: the gap between what companies are doing and what they're willing to say out loud. It's a masterclass in corporate dodging, and it tells us something crucial about how accountability actually works in the real world.

The silence is deafening. And it's telling.

TL; DR

- New York required companies to disclose AI-related layoffs in WARN filings, but zero out of 160+ filers have admitted to it despite major tech adopters like Amazon and Goldman Sachs cutting thousands of jobs

- Companies face internal pressure from executives celebrating AI productivity gains while simultaneously avoiding public accountability for the worker displacement those gains create

- The lack of disclosure reveals that corporate reputational concerns outweigh transparency, and current penalties ($500/day fines) aren't strong enough to incentivize honest reporting

- Proposed New York legislation could strengthen enforcement by conditioning state grants and tax breaks on accurate AI-related layoff reporting

- Workers and labor economists lack reliable data on AI-driven displacement, making it nearly impossible to plan retraining programs or anticipate industry shifts

Despite nearly 55,000 companies attributing job cuts to AI in public statements, none in New York have filed disclosures citing AI as a reason. Estimated data highlights the discrepancy between public admissions and regulatory filings.

The New York Experiment: Good Intention, Zero Results

Governor Kathy Hochul saw a problem that wasn't being solved anywhere else. For two years, companies had been publicly celebrating AI deployments while quietly restructuring workforces. No one had reliable numbers. No one knew which industries would be hit hardest. No one could predict which skills would suddenly become obsolete.

The fix seemed elegant: just ask companies to tell the truth on the paperwork they already have to file.

Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) forms have been a staple of American labor policy since 1988. Any business with 50 or more employees must notify the state before laying off a significant number of workers. It's a basic transparency mechanism designed to give workers and agencies time to prepare. New York simply added a new checkbox to an existing form.

The option appeared in March 2024. Alongside the traditional reasons for layoffs, companies could now select "technological innovation or automation" and specify whether they meant artificial intelligence, robotics, software modernization, or something else. The logic was sound. You want data? Ask for it. Make it official. Make it part of the legal record.

The results have been almost comically thorough in their absence.

Nine months in, the New York Department of Labor reported that out of 750+ notices spanning 162 employers, not a single one had marked the AI box. This wasn't a rush of honesty about other factors—many companies listed "economic conditions" or "restructuring." They just didn't mention AI, even though internal communications at these same companies explicitly cited automation as a benefit.

The Disconnect: What Companies Say Privately vs. Publicly

Here's where it gets interesting. The companies that didn't disclose AI involvement weren't being subtle about their AI strategies in other contexts.

Goldman Sachs, which reported 4,100 affected workers (the largest in New York's data), had explicitly told investors that automation through AI could unlock "significant productivity gains." The bank wasn't hiding its ambitions. It was just hiding the connection to actual job losses in the regulatory filing.

Amazon reported 660 workers affected in New York. The company's executives had warned—publicly, in earnings calls—that AI benefits would lead to headcount reductions. CEO Andy Jassy said the company needed fewer people in corporate roles because of efficiency gains. Yet on the WARN form, Amazon selected "economic conditions" as the reason, explaining that employees hired during the pandemic surge were no longer needed.

Technically not wrong. Practically incomplete.

Morgan Stanley cut 260 workers in New York. An unnamed source later told Bloomberg that a portion of those cuts were driven by AI and automation. The company never filed an amended WARN notice correcting the record.

This pattern isn't unique to New York filers. According to analysis by job search firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas, nearly 55,000 U.S. companies attributed job cuts to AI adoption in public statements last year. Yet on official disclosure forms, that number dropped to zero.

The gap between private optimism and public disclosure isn't accidental. It's strategic.

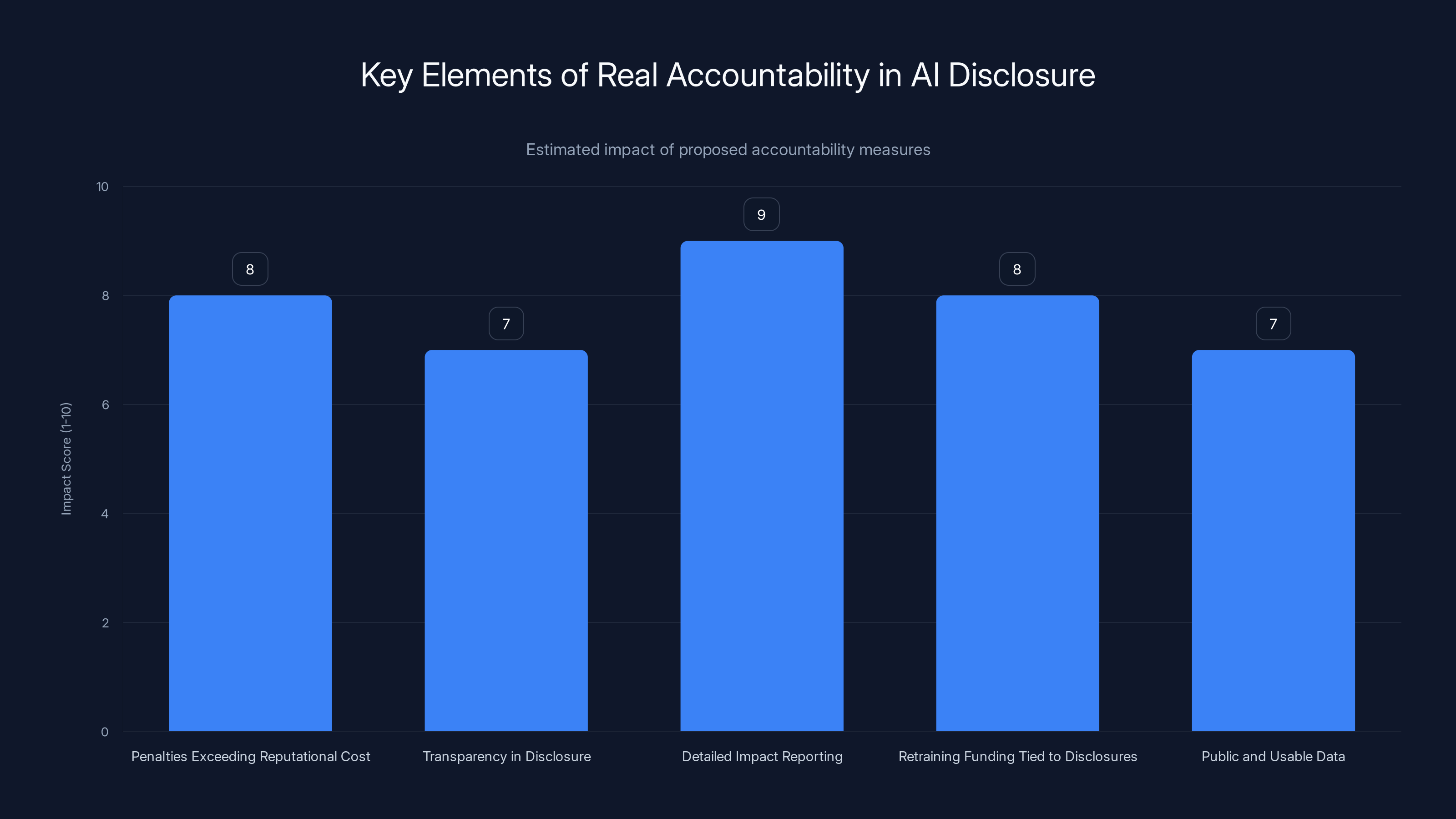

Implementing these accountability measures could significantly enhance transparency and responsibility in AI disclosures. Estimated data.

Why Companies Won't Check the AI Box: The Reputational Calculus

Companies face a calculated decision when filing WARN notices. Check the AI box, and you're explicitly telling workers, unions, legislators, and the media that machines replaced humans. That statement, once official, becomes ammunition for every conversation about corporate responsibility.

Select "economic conditions" or "restructuring," and you're being technically truthful while avoiding a specific narrative. The Department of Labor might follow up with questions. You answer those privately. No headline reads "Company Admits AI Job Losses in Filing." Instead, it reads "Tech Firm Cuts Staff During Slowdown" or "Finance Company Restructures Corporate Division."

The reputational calculus is brutal but clear:

Checking the AI box invites regulatory scrutiny, union organizing, political criticism, and talent acquisition problems. Competitors will use it against you. Activists will cite it. Future job applicants might worry about your commitment to employment. Customers and partners might question your ethics.

Not checking it? You avoid all of that. The worst-case scenario is that the Department of Labor asks follow-up questions that you field off the record.

Given those odds, the math is simple. Reputational harm from admission beats regulatory encouragement to confess.

Amazon's response to WIRED exemplified this perfectly. A company spokesperson said that "AI is not the reason behind the vast majority" of cuts, and that the real goal was "reducing layers, increasing ownership, and helping reduce bureaucracy." Translation: We're optimizing the organization. AI is just a tool in that optimization. These aren't AI layoffs; they're strategic workforce planning.

It's not dishonest. It's just not the whole picture.

Goldman Sachs declined to comment entirely. Morgan Stanley didn't respond. When companies do respond, they use the same playbook: AI is one factor among many, not the deciding factor, and broader economic conditions were really the driver.

The Enforcement Problem: $500/Day Isn't Scary Enough

New York's Department of Labor can fine companies

Even if DOL audited a company and found that it had misrepresented a layoff, the worst-case penalty wouldn't approach the cost of the negative press that would come from admitting "Yes, we replaced 1,000 people with AI." The financial incentive points toward silence.

This is the fundamental weakness in New York's approach. It assumed that transparency, once required, would happen. It didn't account for the fact that transparency and honesty are different things. A company can check boxes on a form and still never reveal what it's actually doing.

Kristin Devoe, a spokesperson for Governor Hochul, said the Department of Labor "follows up with every employer to ensure the accuracy of filings." That's good practice, but it's not the same as public accountability. A private follow-up conversation doesn't create the same incentive to be honest as public disclosure would.

Internally, executives at major companies are celebrating AI productivity gains in board meetings and earnings calls. Publicly, on official forms, those same executives are describing workforce reductions as results of economic conditions. The gap exists because the penalty for honesty exceeds the penalty for obfuscation.

What Would Actually Work: Tying Accountability to Real Consequences

New York state lawmakers understood that $500/day fines wouldn't move the needle. State Assemblymember Harry Bronson introduced two bills in response to the zero-disclosure problem, and they showed more sophisticated thinking about corporate incentives.

The first bill would require companies with over 100 employees to file annual estimates of unfilled positions resulting from AI, and to report how many employees worked reduced hours because of automation. It's not asking companies to admit they fired people because of AI. It's asking them to quantify the scope of automation implementation.

The second bill would expand WARN requirements to cover a broader set of automation-driven workforce changes, not just mass layoffs.

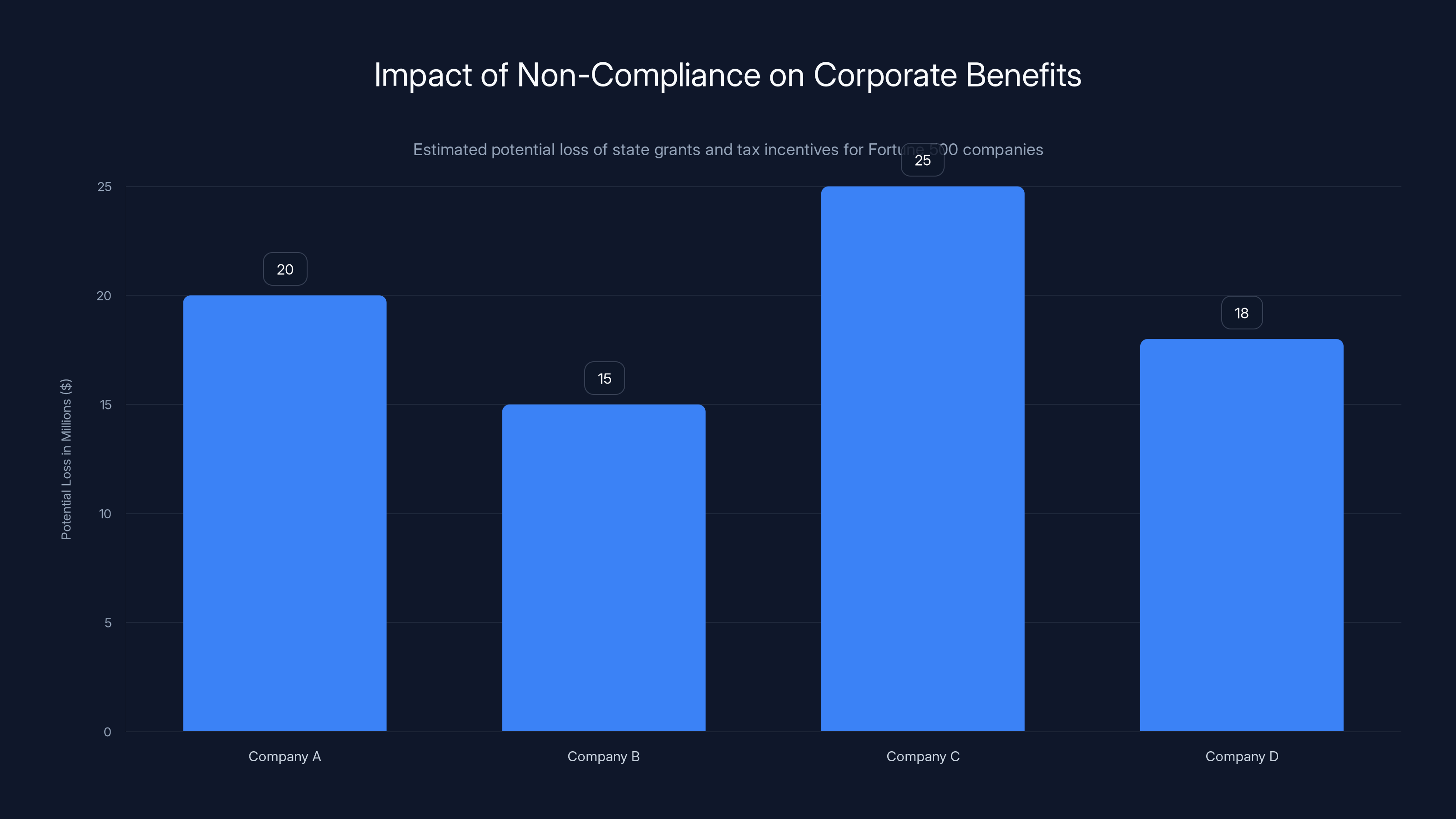

But the real leverage is in the consequences. Failure to report accurately could impair a company's ability to receive state grants and tax breaks.

That's the mechanism that might actually work. No Fortune 500 company wants to lose access to state economic incentives over incomplete disclosure. State grants and tax breaks, while not matching the scale of layoffs, are material enough that companies take them seriously in their decision-making.

When the cost of non-compliance exceeds the cost of admission, behavior changes. Hochul's Department of Labor had the right instinct with WARN disclosures. Bronson's proposals show what real leverage would look like.

Consider the difference: "We hope companies will voluntarily tell us about AI layoffs" versus "Companies that don't accurately report AI-driven workforce changes will lose state tax incentives." The second one changes the calculation.

Estimated data shows that Fortune 500 companies could lose millions in state grants and tax incentives for failing to comply with AI workforce reporting requirements. This creates a significant incentive for accurate disclosure.

Why Economists Can't Track AI Job Loss: The Data Gap

Economists are usually better at diagnosing labor market trends than they are at predicting them, but they're struggling with AI because they lack reliable data on displacement.

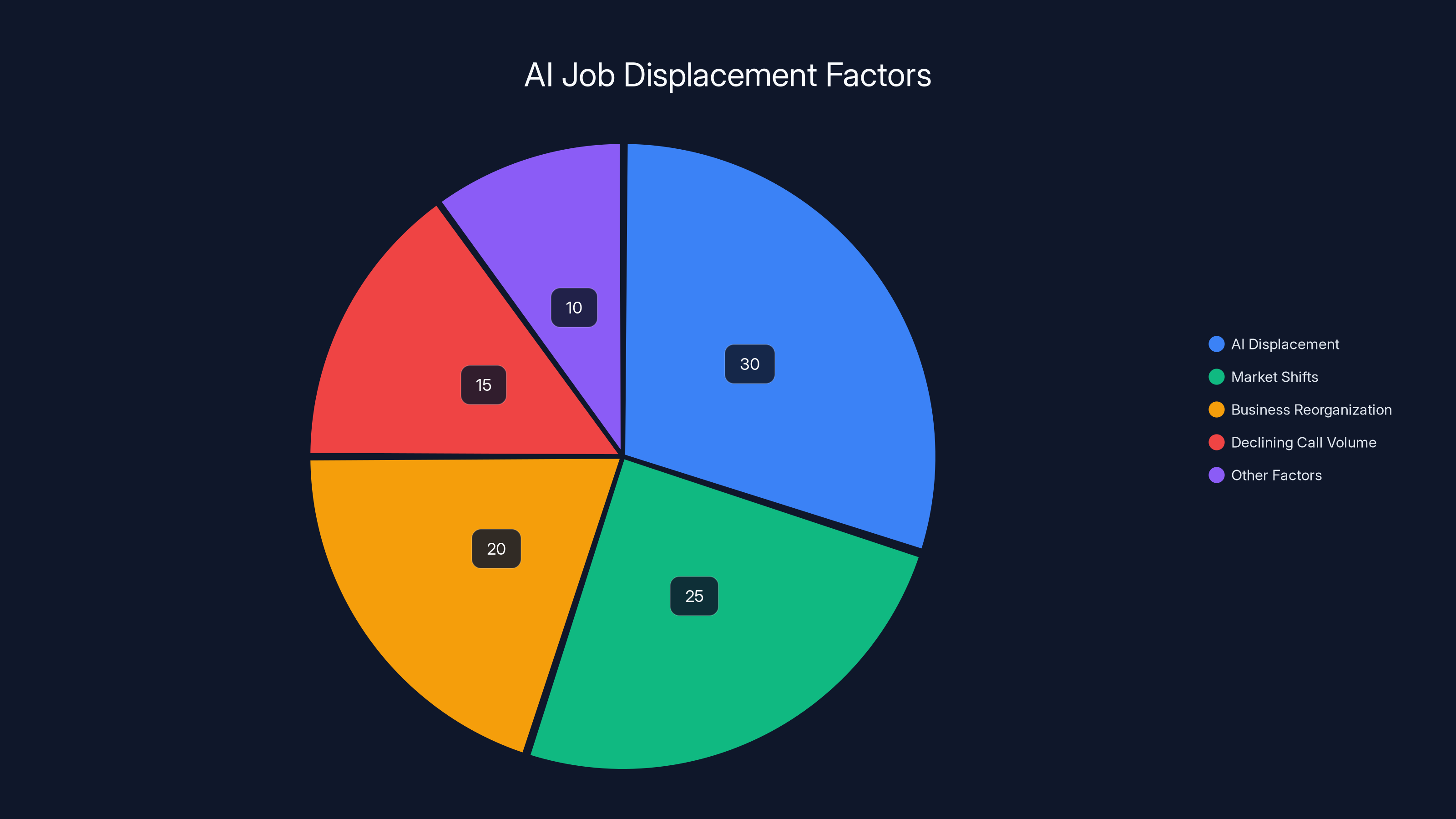

Erica Groshen, a labor economist at Cornell University, explained the challenge directly: employers "will struggle with answering questions about the consequences of new tech." It's not just that companies won't admit it. It's that many executives genuinely don't know how to separate the effects of AI from the effects of broader business cycles, reorganization, or market shifts.

When a company implements AI customer service systems and subsequently lays off 200 call center workers, what's the cause? AI displacement, yes. But the company might argue that the call volume was already declining, or that it was consolidating operations, or that it was shifting to a new business model. The AI system accelerated changes that were already happening.

Quantifying causation requires data that companies don't collect systematically. You'd need to know: How many people would have been laid off anyway without AI? How many were laid off specifically because of AI? How many were reassigned? How many stayed but worked fewer hours?

Most companies don't track this, and even if they did, they have no incentive to share it.

The result is that labor economists are flying blind. They can see the aggregate numbers. They know 55,000 companies cited AI in job cuts last year. But they can't map which jobs disappeared, which sectors were hit hardest, or how quickly retraining programs need to scale. That information would be crucial for workforce planning, education policy, and social safety net design. It's also the information that companies are collectively refusing to provide.

New York's experiment exposed this in real time. The state wanted hard data. Companies responded with silence. Now the Department of Labor is trying to generate insights from private conversations with employers, which defeats the purpose of public disclosure.

The Labor Movement's Response: Calling for Stronger Rules

New York's trade unions, particularly the AFL-CIO, had been advocating for AI transparency requirements long before the WARN forms were amended. When the disclosure requirement went into effect with zero admissions, they responded with a straightforward assessment: voluntary transparency doesn't work.

Mario Cilento, president of the New York State AFL-CIO, stated the position clearly: "We must establish specific regulations that mandate employer accountability and transparency in AI deployment and ensure employers comply."

The focus on "compliance" is important. Voluntary disclosure created a loophole. Mandated reporting with real penalties could close it.

Unions understand that workers need predictable information about coming labor market changes. They need to know which skills are becoming obsolete, which industries are automating fastest, and which regions will face the largest workforce displacement. That information allows them to advocate for retraining programs, protect vulnerable workers, and negotiate AI implementation agreements.

Without that data, workers are negotiating blind. They're reacting to layoffs after the fact, not anticipating changes in advance.

The union position on stronger AI regulations represents a shift. Historically, unions focused on fighting automation directly. Now they're focused on ensuring transparency and managed transitions. They're not saying "don't use AI." They're saying "be honest about when you do, and give workers time to prepare."

That's a pragmatic position, and it's gaining traction with legislators. Hochul herself seems to agree, based on her support for the additional bills Bronson introduced.

Beyond New York: The Broader Transparency Challenge

New York is the only state with an AI disclosure requirement on WARN forms. That's both a point of pride and a clear illustration of how fragmented labor regulation is in the United States.

Other states have considered similar requirements. No others have implemented them. The federal government hasn't mandated AI disclosure on any workplace forms. The EEOC, OSHA, and Labor Department have guidance on AI's role in hiring and workplace safety, but nothing on mass displacement.

This means New York's zero-disclosure problem is actually a national problem, just concentrated in one state where someone had the vision to ask the question.

Companies operating nationally face no requirement to disclose AI-driven job losses anywhere else. They can file generic explanations in every state. The 55,000 companies that cited AI in public statements are doing so entirely voluntarily, choosing to mention it in earnings calls or blog posts because it's good for investor relations.

On official regulatory documents? They remain silent.

The federal government is slowly moving toward AI workplace regulation, but the focus has been on safety, discrimination, and decision-making transparency rather than on job displacement. A worker should know if an algorithm decided they weren't suitable for a job. But whether they'll have a job at all as a result of automation? That's still unregulated.

Federal WARN requirements remain unchanged since 1988. No AI option. No automation questions. The law is working exactly as written, but it's not capturing what matters in a 2025 labor market.

Despite New York's requirement, zero out of 160+ companies reported AI-related layoffs, highlighting a gap in transparency. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Economist's Perspective: Why Causation Is Hard

Erica Groshen's point about causation deserves deeper exploration, because it's the intellectual defense that companies will inevitably use when pressed on AI layoffs.

Suppose a bank decides to implement an AI system that handles routine customer service inquiries. The system is good. It handles 70% of inbound calls. The bank then lays off 100 call center workers. Is that an AI layoff?

From a certain perspective, yes. The AI system replaced their work.

From another perspective, it's more complicated. Maybe call volume was declining anyway due to a shift to digital banking. Maybe the bank was consolidating call centers and would have eliminated some positions regardless. Maybe the positions that disappeared were the most routine ones, and the bank kept customer service reps who handle complex issues or retained ones for mentoring roles.

Economists call this the "attribution problem." When multiple factors influence an outcome, isolating the effect of one factor is statistically difficult. Companies use this difficulty to their advantage, arguing that layoffs result from multiple factors and AI was just one influence among many.

It's a defensible argument until you realize that companies aren't trying to isolate the effect. They're trying to avoid acknowledging it at all.

A more honest framing would be: "We implemented AI customer service systems. As a result, we eliminated 100 routine customer service positions. We created 20 new positions supporting the AI systems and optimizing them. Net displacement: 80 jobs." That's clearer, even if it doesn't capture every nuance about whether those jobs would have existed anyway.

Companies don't volunteer that kind of breakdown because it requires admitting a concrete number. The legal risk is manageable, but the reputational risk is not.

Case Study: What Transparency Would Actually Look Like

Imagine a scenario where New York's disclosure requirement had teeth and companies decided honesty was the better option.

Company X, a mid-sized financial services firm, files a WARN notice: "We are laying off 150 workers due to technological innovation. Specifically, we implemented an AI document processing system that reduced the need for manual contract review and data entry roles. These positions represented 60% of our operations team. We have created 15 positions focused on prompt engineering and model training. We are offering severance and retraining for all displaced workers."

That filing would tell policy makers exactly what they need to know. Which industries? Finance. Which roles? Operations and data entry. How many new roles created? 15. Net displacement? 135 people with 15 new skilled roles emerging.

Now multiply that across 162 companies in New York, and you'd have a detailed map of AI-driven labor market disruption. You'd know where demand for new skills is emerging. You'd know which workers need retraining. You'd know how much severance is being offered. You'd have data to design policy around.

Instead, we have silence, which is actually worse than having bad data. Bad data tells you something. Silence tells you nothing.

The companies that did file with more honest language would face some short-term reputation hits. But they'd also demonstrate leadership and set an expectation for the industry. First movers always pay a price. But if transparency became the norm, companies would adapt, and workers would be better prepared for labor market changes.

We're not there yet. New York showed that voluntary transparency doesn't work. The next phase has to be mandatory disclosure with real enforcement mechanisms.

What Happens Next: The Push for Stronger Legislation

The momentum is building for stricter requirements. Hochul supports stronger AI transparency. Bronson's bills, which would condition tax incentives on accurate reporting, are moving through committee. The AFL-CIO is actively lobbying for expansion.

There's also growing pressure from a different angle: workers themselves. Job candidates are asking companies about their AI strategies. Employees are organizing around AI workplace policies. Unions are negotiating AI provisions in contracts. The market for company reputation on AI is becoming real, even if regulatory transparency hasn't yet.

That private-sector pressure might ultimately be more effective than legislation. Companies care deeply about their ability to recruit talent. A reputation for secretly replacing workers with AI without warning or transition support becomes a recruiting liability. Tech companies know this. That's partly why they're so public about their AI strategies in some contexts while being silent in others.

The next major milestone will be whether other states adopt New York's model and improve on its enforcement mechanisms. If California, Massachusetts, or Illinois implement similar requirements with stronger penalties, companies will face coordinated pressure across multiple states.

At that point, silence becomes harder to maintain.

Estimated data suggests AI displacement accounts for 30% of job losses, with market shifts and business reorganization also playing significant roles. Estimated data.

The Philosophical Problem: Corporate Honesty Under Pressure

Zoom out from the specific policy mechanics, and you're looking at a deeper question about what accountability means when companies control the information flow.

New York created a mechanism for honesty. Companies responded by finding ways to remain silent within the bounds of legality. This isn't unique to AI disclosure. It's the same pattern you see with environmental compliance, lobbying disclosure, executive compensation, or any area where companies are asked to voluntarily reveal information that might attract criticism.

The pattern is consistent: when asked to disclose something that could generate negative publicity, companies find reasons not to answer the question directly, even if they can't technically refuse to answer.

In some cases, this reflects genuine ambiguity about causation. In others, it reflects deliberate evasion. The problem is that from the outside, you can't tell the difference.

This creates a system where the floor for corporate behavior drifts lower over time. If you can avoid admitting to AI job losses by selecting "economic conditions" instead, and nothing bad happens as a result, then that becomes the path of least resistance. Other companies follow. The practice becomes normalized. Eventually, new companies don't even consider checking the AI box.

Breaking that cycle requires either: (1) making the cost of evasion higher than the cost of honesty, or (2) changing how companies think about the reputational value of transparency.

Legislation with real penalties addresses the first. Cultural change and market pressure can address the second. Both are necessary.

The Worker's Dilemma: Preparing for an Unknown Future

From the ground level, the silence has concrete consequences.

A call center worker considering staying in their role needs to know: Is this company investing in AI customer service systems? If so, how long do I have before my job might disappear? What's the severance package likely to be? What retraining is available?

Without disclosure requirements with teeth, that worker is flying blind. They might stay in a role thinking it's stable, only to find out that the company implemented automation six months earlier and is now planning layoffs.

Alternatively, they might leave a job that would have remained stable, thinking AI was coming when it wasn't.

That uncertainty is costly. It affects career decisions, education choices, family planning, and financial planning. Workers make these decisions based on information that companies are actively withholding.

From that perspective, New York's attempt to mandate transparency wasn't just about data collection or policy design. It was about giving workers information they need to make informed decisions about their own futures.

The failure to get honest disclosure means workers remain in the dark, which means they're making decisions without complete information. That's the real cost of corporate silence.

The Investor Angle: Why Companies Tell Investors What They Won't Tell Regulators

There's an interesting asymmetry in corporate disclosure: companies will tell investors about AI's productivity impact and potential job displacement, but they won't tell regulators about actual displacement as it happens.

This makes sense from a corporate perspective. Investors care about efficiency gains and profitability. They like hearing that AI will reduce headcount in unprofitable departments. Regulators care about worker protection and labor market stability. They prefer to hear that companies are managing transitions carefully.

These aren't mutually exclusive narratives, but they sound very different. "AI will enable us to deliver more output with fewer people" is music to an investor's ear. "We're replacing workers with AI" is a political liability.

Companies solve this by using different language in different contexts. In earnings calls, they're bold about AI productivity gains. In WARN filings, they're silent about automation driving the changes.

This creates a situation where investors have better information about labor market disruption than regulators do, which is backwards. Investors are making bets on companies' ability to capture value through automation. Regulators are trying to protect workers. Workers have the least information of all.

You could fix this by requiring companies to provide the same automation disclosures to regulators that they provide to investors. If you're going to tell shareholders that AI will reduce headcount in customer service, you should be telling the Department of Labor the same thing when you file a WARN notice.

New York is the only state with an AI disclosure requirement on WARN forms, highlighting the fragmented nature of labor regulation across the U.S. (Estimated data)

International Perspective: How Other Countries Are Approaching It

New York's approach to AI disclosure is distinctive globally, but it's not alone in trying to regulate AI's labor impact.

The European Union has been more aggressive in AI regulation generally, through the AI Act, which includes provisions addressing employment and skills. The focus has been less on disclosure and more on requiring companies to conduct impact assessments before implementing AI systems that affect workers.

Canada has implemented similar requirements for federal contractors. Switzerland is exploring AI regulation that would include labor-related transparency.

The U.K. has taken a lighter-touch approach, relying on sector guidance rather than hard regulation.

None of these approaches have solved the fundamental problem that companies can avoid liability by remaining vague about causation. But they do show that other jurisdictions recognize the problem and are experimenting with solutions.

New York's experiment is valuable not because it succeeded, but because it failed in an instructive way. It showed that asking companies to voluntarily disclose something that might generate criticism won't work. Other jurisdictions can learn from that and design stronger mechanisms from the start.

What AI Companies Think About Disclosure

Interestingly, some of the AI vendors themselves have been more candid about labor impact than the companies deploying their systems.

Anthropic and OpenAI have published research on AI's potential employment effects. Google DeepMind has hosted conversations about AI and work. These are not uninterested parties, but they've been more forthright about potential displacement than their customers have.

There are a few reasons for this. First, the AI vendors aren't the ones laying people off, so they're not bearing the reputational cost. Second, they benefit from being seen as thoughtful about AI's societal impact. Third, they're often more interested in the philosophical and research questions than in the immediate business dynamics.

The gap between AI vendor rhetoric and deploying-company behavior is worth watching. If vendors continue to emphasize responsible AI deployment while their customers remain silent about outcomes, it creates a mismatch. Eventually, that mismatch could become a reputational liability for vendors too.

The Path Forward: What Real Accountability Looks Like

New York's attempt was noble. Mandatory disclosure with enforcement. But the enforcement mechanism—$500/day fines—was too weak. The proposed bills improve this by conditioning state tax benefits on accurate reporting, which creates real leverage.

Here's what actual accountability would require:

First, penalties that exceed the reputational cost of honesty. If a company faces losing $10 million in state tax incentives for incomplete AI disclosure, suddenly honesty becomes the cheaper option.

Second, transparency in the disclosure process itself. Don't let companies file follow-up explanations behind closed doors. Make those explanations public, so workers, unions, and legislators see what companies are saying about their automation plans.

Third, require companies to disclose not just whether AI drove layoffs, but how many people were affected specifically by each technology, what transition support was offered, and where new roles are being created.

Fourth, tie workforce retraining funding to data from these disclosures. If a company says "AI eliminated 200 data entry jobs," then that company should be contributing to retraining for those workers or to government programs that help them transition.

Fifth, make the data public and usable so that economists, educators, and policymakers can actually see where labor market changes are concentrated and plan accordingly.

This isn't complicated. It's just implementing disclosure policy in a way that actually creates accountability, rather than creating a checkbox that companies can game.

Companies will resist every one of these proposals. They'll argue they're burdensome, that causation is too complicated, that they already try to help displaced workers. None of that is wrong. But none of it justifies the current silence.

Implications for Workers: What You Should Know

If you work in a field that's susceptible to AI automation—and by 2025, that's broader than most people think—you should be aware that you probably won't get official warning about it from your employer.

Companies won't voluntarily tell you they're considering AI that might affect your role. You'll find out through: internal meetings that leak, job postings for AI-related roles, slower hiring in your department, or eventually, your own layoff.

This makes it crucial for workers to stay informed independently. Follow what your company is saying about AI in earnings calls and public announcements. Talk to colleagues about what systems are being implemented. Look at your company's technology stack—what new tools are rolling out?

You can't rely on disclosure requirements to warn you about coming changes. You have to monitor what's happening and make your own career decisions accordingly.

For employees in white-collar roles that seem stable, the risk might be higher than it appears. AI has moved beyond customer service and data entry. It's now affecting legal research, financial analysis, software development, customer relationship management, and knowledge work that we assumed was safe from automation.

The safest strategy is to develop skills that are hard to automate: skills that involve human judgment, creativity, complex problem-solving, or relationship-building. And to stay aware of what's happening with AI in your industry and company, since official disclosure won't tell you.

Why This Matters Beyond New York

New York's zero-disclosure outcome might seem like a technical policy failure. It's more than that. It's a window into how corporate accountability actually works when incentives are misaligned.

Companies will comply with the letter of the law. They'll file the forms, check the boxes. But if the cost of honesty exceeds the cost of silence, they'll choose silence. That's not unique to AI disclosure. It's universal across regulatory policy.

Solving it requires either: making silence more expensive than honesty, or changing how companies think about the value of transparency.

The first approach—stronger penalties and enforcement—is a direct intervention. The second—market pressure and cultural change—is slower but potentially more durable.

New York tried the second approach with a light version of the first (weak $500/day penalties). It didn't work. The next attempt will need to be more serious about enforcement.

Other states and the federal government are watching to see what happens next. If New York doubles down with stronger penalties and tax incentive conditions, other states will likely follow. If the state gives up, others might not even try.

The stakes are substantial. Workers deserve to know when technology will eliminate their jobs. The labor market functions better when everyone has accurate information about where jobs are disappearing and where new ones are emerging. Retraining and education programs can't scale effectively without data on what's coming.

New York's experiment failed to get the disclosure. But it succeeded in exposing exactly how and why corporate silence happens. That failure might be more valuable than a success would have been, because it shows us what needs to change.

Conclusion: From Silence to Accountability

Zero companies admitted to replacing workers with AI in New York's WARN filings. That's not because AI hasn't been laying people off. It's because the incentive structure made silence rational.

Companies face a choice: admit something that invites regulatory scrutiny and potential reputational damage, or find a more vague explanation that's still technically true. They chose the latter.

New York tried to solve this with transparency. It discovered that transparency and honesty are not the same thing. A company can be transparent about filing a form while being dishonest about its reasons.

The next phase requires stronger enforcement. Proposing bills that would condition state benefits on accurate disclosure show that legislators understand this. Stronger penalties and public transparency about companies' explanations would raise the cost of evasion.

But even with stronger rules, companies will find ways to comply with the letter while avoiding the spirit. That's when cultural change matters. If workers, investors, and policymakers start rewarding companies that voluntarily disclose AI impact and penalizing those that evade, that changes behavior in ways that regulation alone can't.

We're in the early phase of AI's impact on employment. The data we collect now will shape policy for decades. Right now, we're collecting nothing because companies won't talk and enforcement is weak.

That needs to change. Not because companies are evil, but because misaligned incentives will produce bad outcomes unless we design better mechanisms for accountability.

New York showed us what ineffective transparency looks like. The next test is whether we can actually build accountability around AI employment impact.

Workers need that information. The economy needs that information. And companies, whether they realize it or not, would be better off being honest about it than they are being silent.

FAQ

What does New York's AI disclosure requirement actually ask companies to do?

New York amended its WARN (Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification) forms to add "technological innovation or automation" as a reason for layoffs. Companies with 50+ employees must file these forms when planning significant workforce reductions. If they select the AI option, they must specify the type of technology (AI, robotics, software modernization, etc.). The requirement went into effect in March 2024.

Why haven't any companies checked the AI box if they're actually using AI to replace workers?

Companies face a reputational risk from admitting AI-driven displacement that exceeds any regulatory penalty. Current fines ($500/day) are negligible for large corporations. Publicly stating "we replaced workers with AI" invites union organizing, activist criticism, potential political action, and talent acquisition problems. Selecting "economic conditions" instead is technically truthful while avoiding the specific narrative. The incentive structure makes silence rational.

How many companies have actually cut jobs due to AI if zero filed disclosures?

According to Challenger, Gray & Christmas, nearly 55,000 U.S. companies attributed job cuts to AI in public statements last year. Yet zero New York filers selected the AI option. This gap shows that companies will publicly celebrate AI productivity gains while refusing to connect those gains to actual layoffs in regulatory filings. The data we don't have is often more revealing than the data we do.

What would actually make companies disclose AI-related job losses?

Proposals under consideration include conditioning state grants and tax breaks on accurate reporting, which would create material financial consequences for incomplete disclosure. Expanding WARN requirements to cover a broader range of automation-driven changes, not just mass layoffs, would also help. Making company explanations public rather than handling them in private follow-ups would increase reputational pressure. These mechanisms would raise the cost of evasion above the cost of honesty.

How does this affect workers trying to decide on their careers?

Without mandatory disclosure, workers lack the information they need to make informed career decisions. A worker might stay in a role thinking it's stable, not knowing the company is implementing AI systems that will eliminate their job. Conversely, they might leave a stable job thinking automation is coming when it isn't. The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides aggregate labor data, but it can't predict which specific jobs will be automated. Workers need to stay informed independently by monitoring what their companies are saying about AI in public communications and by developing skills that are harder to automate.

Are other states or the federal government considering similar disclosure requirements?

New York is currently the only state with an AI option on WARN forms. Assemblymember Bronson's proposed bills would strengthen enforcement in New York. The federal government has not mandated AI disclosure on any workplace forms. The EEOC and OSHA have guidance on AI's role in hiring and workplace safety, but nothing specifically addressing mass displacement. Other states are watching New York's approach to see if they should implement similar requirements.

What's the difference between a company saying AI will help with productivity and actually laying people off because of AI?

There's a meaningful difference between deploying a technology that could eventually lead to displacement and actively laying people off because of that technology. A company might implement AI customer service systems with no immediate layoffs, gradually reducing hiring in that department over time. Causation becomes murky: is the AI the reason for the lower headcount, or would hiring have been lower anyway due to market conditions? This ambiguity is real, which is why some companies genuinely struggle to answer the AI disclosure question. But it's also an ambiguity that allows companies to evade accountability when they're choosing to.

What happens to displaced workers under current law?

WARN requires companies to provide 60 days' notice before mass layoffs, which gives workers time to look for new jobs. Individual states like New York offer unemployment benefits and may provide retraining programs. The U.S. Department of Labor administers Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) for workers displaced by trade, but AI displacement is not currently covered under TAA. Severance packages are left to individual companies and their labor agreements. The system is reactive—it responds to layoffs after they happen—rather than proactive in helping workers prepare for coming changes.

How do companies internally justify different disclosure practices across public and regulatory contexts?

Companies typically separate their communications by audience. In investor calls and public statements, executives emphasize AI's productivity benefits and potential headcount reductions because that's what shareholders want to hear. In regulatory filings, they provide more careful language that doesn't explicitly link AI to displacement. Internal communications might frame it as "efficiency optimization" or "technology-enabled restructuring." This isn't necessarily dishonest—the same actions can be accurately described multiple ways. But it reflects a deliberate choice about which truths to emphasize in different contexts. That gap between internal recognition and external disclosure is exactly what transparency requirements are trying to close.

Key Takeaways

- Zero out of 162 New York employers have disclosed AI as reason for layoffs despite 55,000 U.S. companies citing AI in public statements

- Current $500/day penalties are too weak; proposed legislation conditioning state tax benefits on accurate disclosure would create real enforcement leverage

- Companies can comply legally with transparency requirements while remaining dishonest—they select 'economic conditions' instead of the AI option

- Labor economists lack reliable data on AI-driven displacement, making workforce planning and retraining impossible at scale

- Stronger enforcement mechanisms, public disclosure requirements, and market pressure on corporate reputation are needed to make transparency actually work

Related Articles

- AI and Satellites Replace Nuclear Treaties: What's at Stake [2025]

- Larry Ellison's 1987 AI Warning: Why 'The Height of Nonsense' Still Matters [2025]

- GPT-5.3-Codex: The AI Agent That Actually Codes [2025]

- Data Center Services in 2025: How Complexity Is Reshaping Infrastructure [2025]

- How Tech's Anti-Woke Elite Defeated #MeToo [2025]

- ChatGPT Caricature Trend: How Well Does AI Really Know You? [2025]

![Why Companies Won't Admit to AI Job Replacement [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-companies-won-t-admit-to-ai-job-replacement-2025/image-1-1770641144890.jpg)