Space X's Strategic Pivot: Why the Moon Comes Before Mars

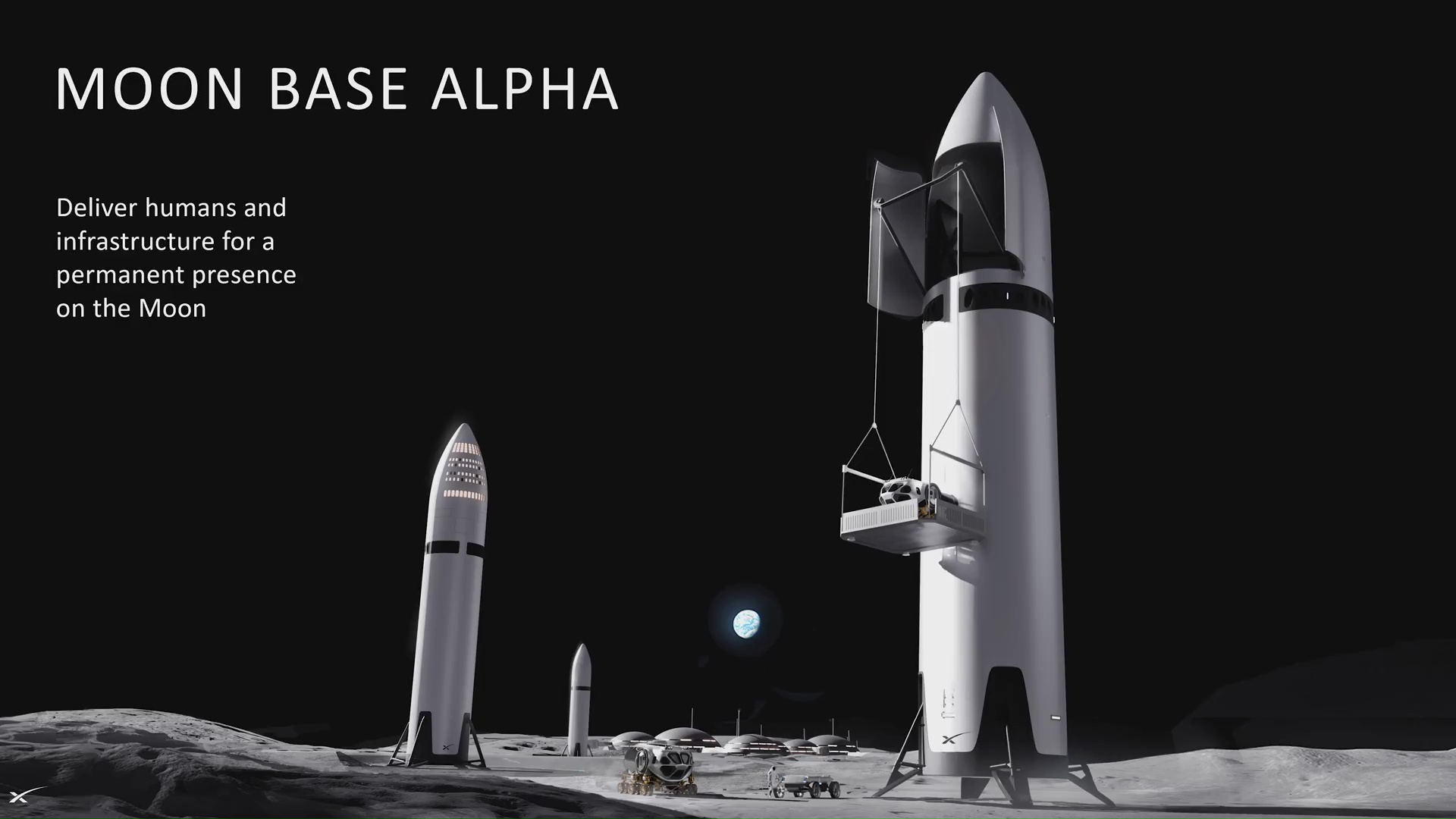

Elon Musk just dropped a bombshell. After years of declaring Mars as Space X's ultimate destination, the company is fundamentally restructuring its priorities. The new goal? A self-growing city on the Moon, completed within a decade. Mars still matters, sure, but it's now playing second fiddle to lunar development. According to Business Insider, this strategic shift is driven by logistical advantages and resource availability on the Moon.

This isn't a casual change of direction. It's a comprehensive rethinking of how humanity gets to Mars in the first place. And honestly, it makes more sense than the pure Mars-focused strategy ever did. As noted by CNN, the Moon serves as both a proving ground and a refueling station, making it a strategic waypoint for Mars missions.

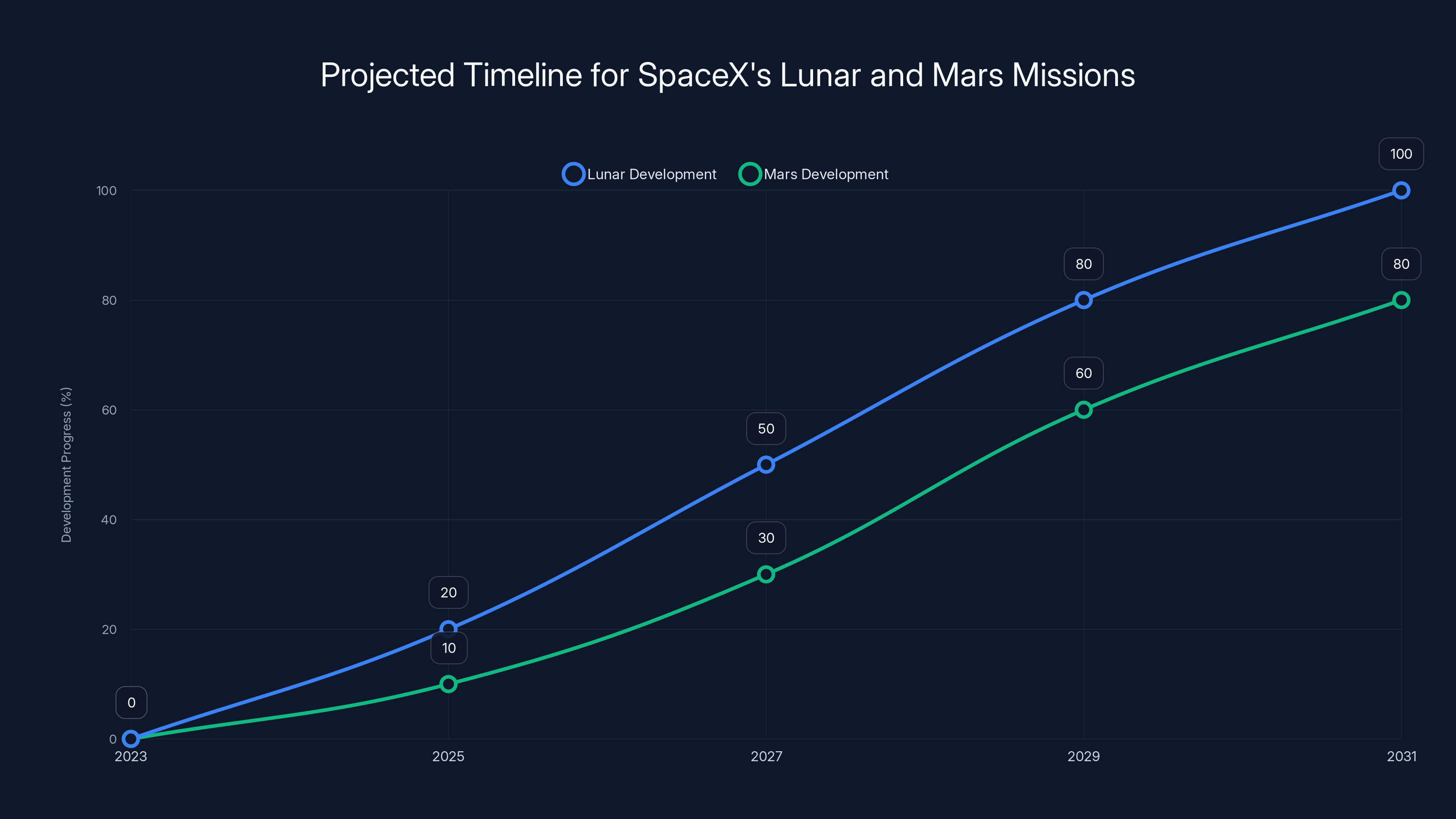

The shift happened quietly but decisively. In a series of posts on X (formerly Twitter), Musk outlined the new timeline: the Moon in under 10 years, Mars starting in 5-6 years but running parallel to lunar work. A crewed Mars flight might happen by 2031, though anyone familiar with Musk's track record knows these timelines come with asterisks. This timeline aligns with NASA's Artemis program, which is accelerating lunar exploration efforts.

This move reflects something important about space exploration. It's not about choosing one destination over another. It's about recognizing that the Moon serves as both a proving ground and a refueling station. Building a sustainable lunar base creates the infrastructure, experience, and confidence needed to make Mars settlements actually work. As reported by Sci.News, lunar regolith contains oxygen at concentrations around 45 percent by mass, which is crucial for supporting human presence.

The original Mars-only strategy always felt rushed. Skip the Moon, go straight to Mars. Bold, sure. But bold doesn't always equal smart. The new approach is methodical. It prioritizes what works logistically over what sounds impressive in marketing materials. According to USA Today, the Moon's proximity to Earth allows for more frequent resupply missions, making it a more practical first step.

What makes this pivot particularly significant is the reasoning behind it. Musk pointed specifically to launch windows and proximity advantages. Earth and the Moon exist in relative proximity, making resupply missions manageable. Mars? That's a completely different beast. Launch windows only occur every 26 months. Supply chains are exponentially more complex. Building up to Mars through lunar development creates a smoother transition. As noted by WRAL, NASA and the Department of Energy are developing nuclear power systems for the Moon, which will further support lunar infrastructure.

There's also the question of why this shift happened now. It's not random. It reflects growing acceptance within the space industry that lunar development provides critical advantages for Mars colonization. NASA proved something crucial in 2023: oxygen extraction from lunar regolith is viable. That material covers the Moon's surface at 45 percent oxygen. Extract that, and you've suddenly cut payload requirements dramatically when shipping supplies to Mars. This development was highlighted in a USRA report.

The timing also aligns with NASA's Artemis program accelerating. Artemis II is set to launch in March 2025, with crewed lunar landings expected by 2028. Space X isn't operating in isolation anymore. It's part of a larger ecosystem where government missions, private contractors, and independent space companies are all converging on the Moon first. This collaboration is detailed in NASA's official announcements.

Musk's earlier dismissal of lunar focus now reads differently. In early 2024, he posted that the Moon was a "distraction" and Space X would go "straight to Mars." That statement came in response to an analyst pointing out the oxygen extraction advantage. Now, he's evidently reconsidered. The oxygen advantage alone is transformative. Why haul liquid oxygen from Earth when you can mine it locally? This change in perspective is discussed in WESH's coverage of Space X's recent acquisitions.

This represents a maturation in thinking about space infrastructure. The romantic vision of Mars colonies is compelling. But the pragmatic approach says you need waypoints, supply caches, and proven systems first. The Moon becomes that waypoint. It's close enough for regular resupply missions, far enough to require solving critical problems, and resource-rich enough to support human presence. As Britannica notes, Musk's evolving strategy reflects a deeper understanding of space logistics.

The business implications matter too. A lunar base proves Space X can build and maintain long-term infrastructure beyond Earth. That's attractive to governments, private investors, and international partners. Mars is still the dream, but the Moon is the business case. This strategic alignment is echoed in Engadget's analysis.

Historically, space exploration has always involved incremental steps. The progression from suborbital flights to orbital missions to the Moon to deep space didn't happen by skipping steps. It happened because each achievement enabled the next. Space X's pivot essentially acknowledges this reality.

What's really fascinating is how this decision positions Space X within the broader space industry. Other companies, NASA, international agencies, and even space-faring nations are all looking at lunar development. Space X moving in that direction aligns with where the entire industry is moving. It's not abandoning Mars. It's recognizing that Mars success depends on lunar infrastructure first.

The Logistical Reality: Why the Moon Makes Sense

Let's talk about why launch windows matter so much. Earth and Mars don't maintain consistent proximity. They move in their respective orbits like dancers occasionally close together, occasionally far apart. When they're far apart, getting to Mars requires exponentially more energy. When they're close, you can actually make the journey.

This creates a problem called "launch window constraints." A Mars-bound spacecraft can only launch during certain periods, roughly every 26 months. Miss that window, and you wait 26 months for the next opportunity. That's two years of waiting. It's not just inconvenient—it's economically brutal. Every payload sitting in a warehouse is capital not producing returns.

The Moon? It's always there, relatively speaking. You can launch lunar-bound missions almost any day you choose. The orbital mechanics are straightforward. The distances are manageable. You gain enormous flexibility in scheduling, testing, and operations. That flexibility translates to efficiency.

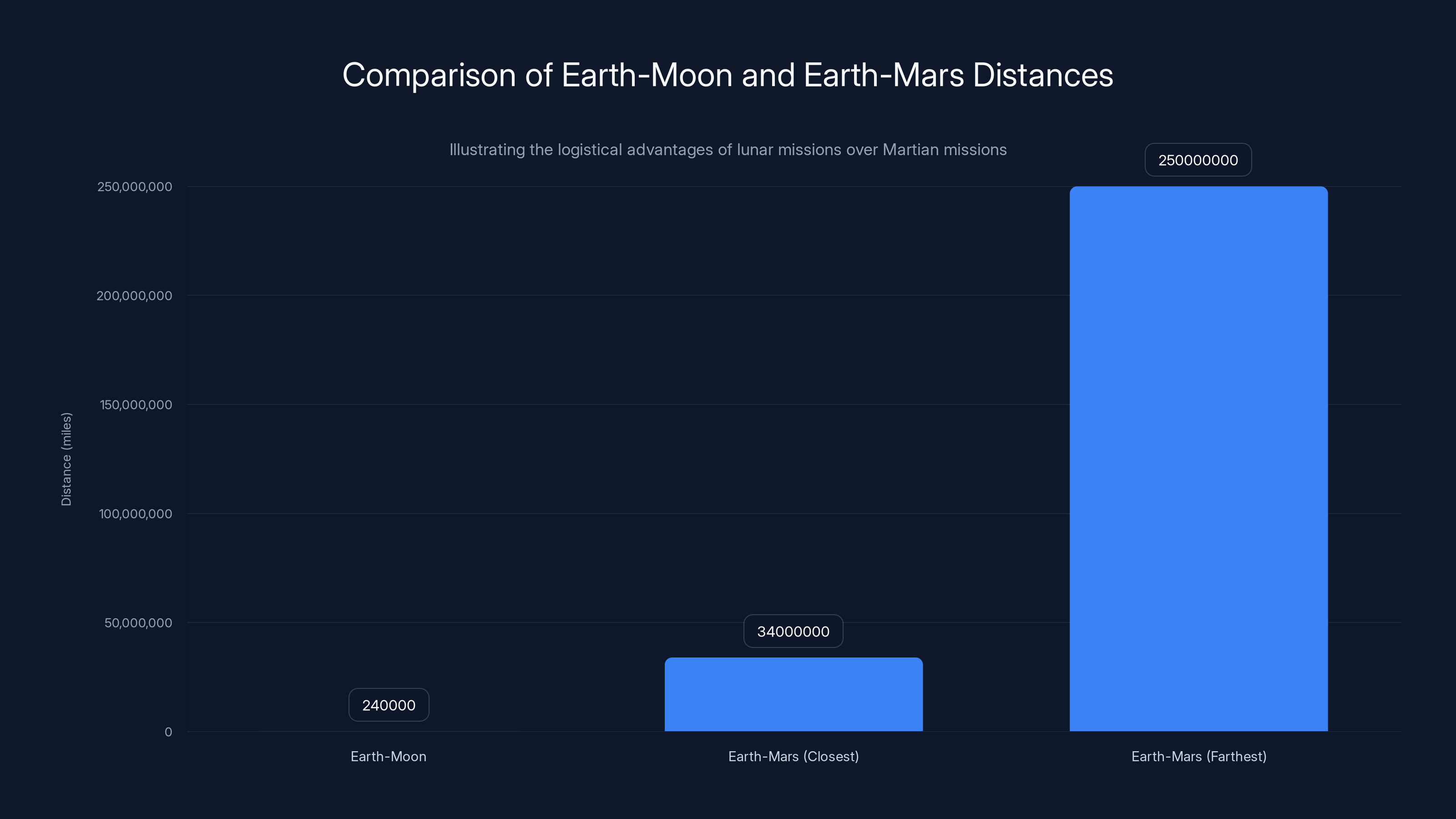

Distance also matters profoundly. The Moon orbits about 240,000 miles from Earth. Mars? Anywhere from 34 million to 250 million miles away, depending on orbital positions. When something breaks on the Moon, you can send a rescue mission or spare parts in days. On Mars, you're looking at 3 to 22 minutes of communication delay, one way. If an astronaut needs help, that help can't arrive for months.

This isn't abstract physics. It's the difference between manageable risk and catastrophic risk. Building systems on the Moon lets you debug them, repair them, and iterate while maintaining a lifeline to Earth. Do that on Mars, and you're essentially committed. You can't call for help. You can't send a replacement part next week.

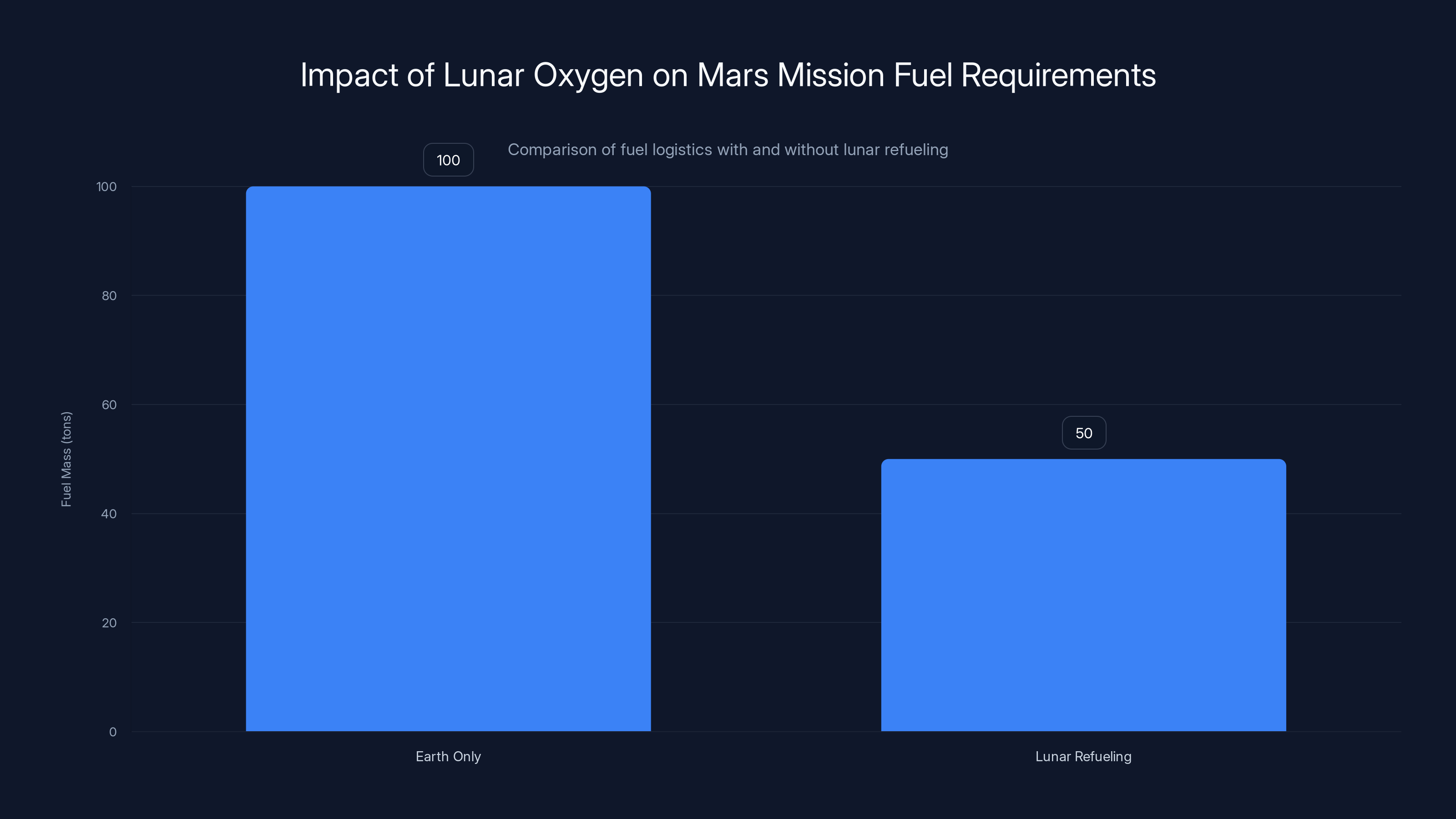

The payload calculus shifts dramatically with lunar development. Imagine you're sending supplies to a Mars base. Currently, you're hauling everything from Earth, including water, fuel, and oxygen. Every kilogram you send costs money, time, and rocket capacity. Now imagine you've got a lunar base extracting oxygen and water from local resources. Suddenly, Mars supply missions become exponentially lighter and cheaper.

There's also the engineering validation problem. New spacecraft, life support systems, habitat designs, and power generation equipment all need testing. Testing in Earth orbit is one thing. Testing on an actual planetary surface, even one as forgiving as the Moon, teaches you things you can't learn in simulations.

Musk's reference to "proof of concept" is key here. The Moon becomes the testing ground for technologies that will later operate on Mars. If a solar panel design fails on the Moon, you learn about it 240,000 miles away instead of 140 million miles away. If a water recycling system has problems, you can fix it while you still have reasonable access to support and replacement components.

The resource angle deserves deeper examination. Lunar regolith contains oxygen at concentrations around 45 percent by mass. That's not evenly distributed—some areas are richer than others. But the potential is staggering. A single lunar base extracting oxygen could eventually produce fuel for deep space missions. Imagine having fuel depots on the Moon. Now trips to Mars become cheaper and faster.

Water ice, increasingly confirmed in lunar polar regions, adds another dimension. Water means drinking water for inhabitants, oxygen through electrolysis, and hydrogen for fuel. A self-sustaining lunar base becomes possible because the Moon provides the raw materials needed for life support and propulsion.

Another crucial consideration is the testing of life support systems at scale. The Moon offers something Earth orbit and simulations cannot: the actual surface environment. Low gravity, solar radiation, dust interactions, thermal extremes, and seasonal variations all affect equipment differently than Earth-based testing predicts. Building lunar habitats and working there teaches you what actually breaks, what needs improvement, and what designs are fundamentally sound.

The political calculation matters too. International partners, investment firms, and government agencies are more comfortable with incremental progress than moonshot timelines. A decade-long program to build a lunar base looks achievable. A 20-year program to settle Mars looks vague. Backers, government approvals, and continued investment are easier to secure when timelines seem realistic.

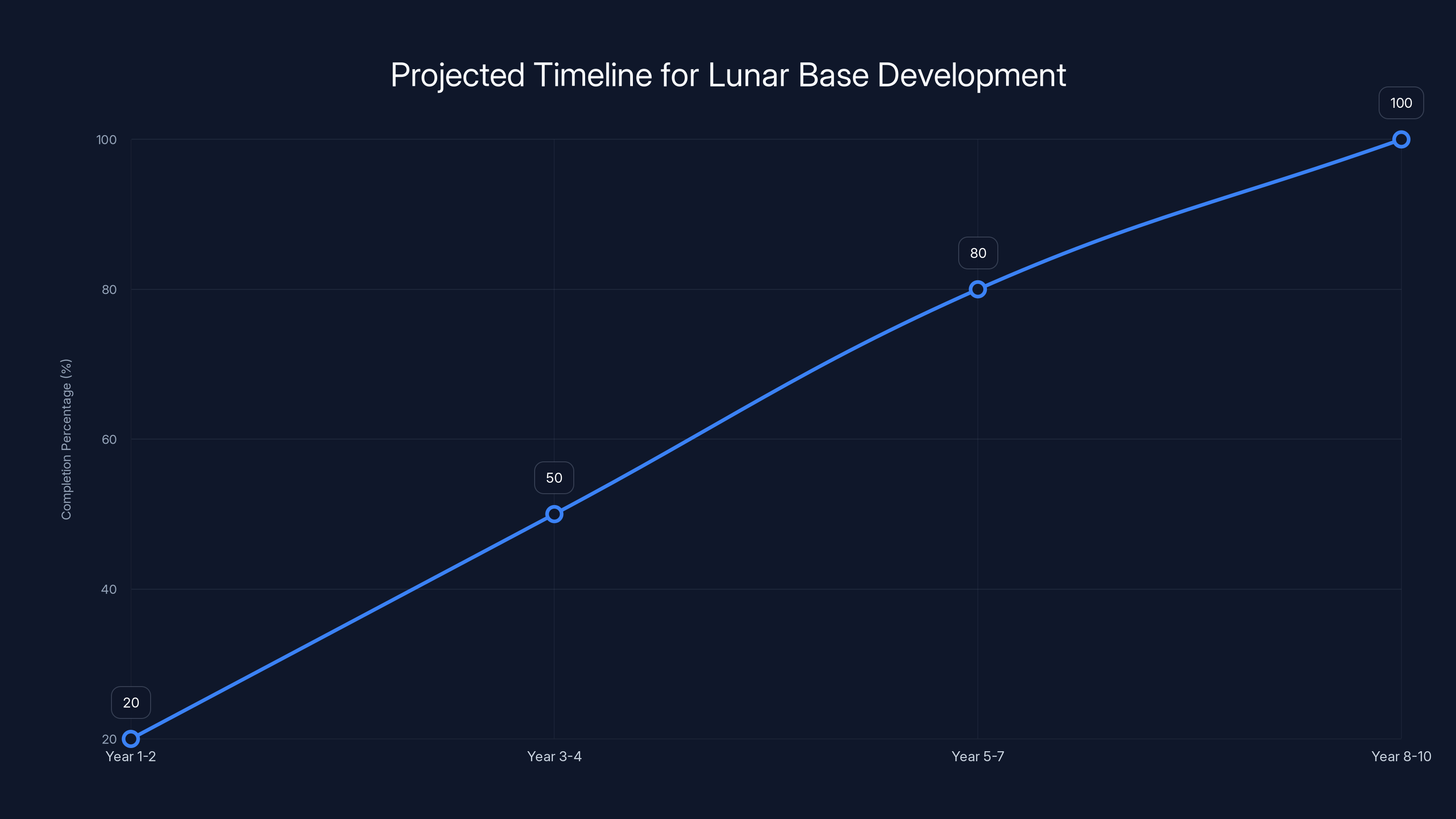

The projected timeline suggests a phased approach to building a lunar base, with significant milestones achieved every few years. Estimated data based on typical space project timelines.

Elon Musk's Evolving Vision: From Mars-Only to Strategic Sequencing

Musk's about-face on the Moon deserves analysis because it reveals something about how strategic planning actually works at Space X. Early declarations about "going straight to Mars" sounded decisive. They also sounded wrong, as it turned out.

In early 2024, Musk posted emphatically that the Moon was a distraction. The company would focus exclusively on Mars. This came in response to a space industry analyst, Peter Hague, noting that lunar oxygen extraction could save enormous payload costs. Musk's response at the time was essentially: we don't need that. We're going to Mars.

Fast-forward less than a year. Musk is now saying the company will focus on the Moon first, with Mars development running parallel. The question is: what changed?

The most obvious answer is that the engineering realities became clearer. Space X has been working on Starship, testing orbital mechanics, and running simulations. These tests probably revealed something important: the payload requirements for Mars settlement are even more daunting than previously acknowledged. You can't just land once and have people survive. You need redundancy, supplies, backup systems, and local resource development. The Moon becomes the training ground for all of that.

Musk has a history of making bold predictions then adjusting course. In 2017, he said a Mars base would be ready for settlers by 2024. That obviously didn't happen. He predicted full self-driving cars, Tesla factories in every state, and various other timelines that slipped. These slippages aren't failures so much as evidence that he's working with incomplete information and adjusting as new data arrives.

The pivot also reflects conversations he's likely had with engineers, partners, and analysts. When you're planning actual missions rather than theoretical roadmaps, the complexity reveals itself. A team of engineers working through the details probably convinced leadership that a phased approach makes more sense.

There's also the competitive element. Other companies and space agencies are moving toward lunar development. If Space X ignored the Moon while everyone else built infrastructure there, Space X would eventually need that infrastructure to support Mars work. Better to lead the effort and control the narrative than follow later.

Musk's statement that Mars development would run parallel to lunar work is strategic. It suggests Space X isn't pausing Mars work. It's reprioritizing focus while keeping Mars development ongoing. That's different from abandoning Mars. It's sequencing the work differently.

The timeline of "Mars will start in 5 or 6 years" is interesting because it's concrete enough to sound committed but vague enough to adjust later. A manned Mars flight by 2031 is similarly positioned. It's far enough away that many factors could change, near enough to feel like progress.

What's changed in Musk's thinking is public acknowledgment that sequencing matters. You don't jump directly to the hardest challenge. You work your way up. The Moon is harder than Earth orbit but far easier than Mars. It's the logical intermediate step.

This reveals something about Musk's leadership style. He's willing to reverse previous positions when engineering evidence suggests he should. That's actually good engineering judgment, even when it looks like inconsistency from the outside.

The Mars-only strategy, in retrospect, was more about clarity of vision than practical feasibility. Clear vision is motivating. It energizes engineers, attracts investment, and captures public imagination. But you can't actually build civilization on Mars without solving the intermediate problems. The Moon solves those problems first.

SpaceX plans to complete a lunar city by 2033, with Mars missions starting in parallel by 2029. Estimated data based on Musk's timelines.

NASA's Artemis Program: How Government and Private Sector Align

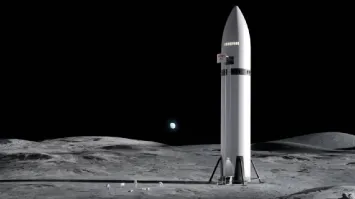

Space X's pivot doesn't happen in isolation. NASA's Artemis program is simultaneously planning lunar return missions. Space X is a contractor for portions of Artemis, including Starship development. These two paths aren't separate. They're increasingly overlapping.

Artemis II, scheduled for March 2025, will send astronauts to circle the Moon and return to Earth. It's a relatively modest mission in scope but crucial for testing procedures and systems. Artemis III, planned for 2028, will actually land humans on the Moon again, the first time since 1972.

Space X's involvement in Artemis is significant. NASA selected Space X's Starship as the lunar lander for Artemis missions. That means Space X is developing the actual vehicle that will land NASA astronauts on the Moon. This isn't a theoretical exercise. It's a funded, contractual obligation.

How does this align with Space X's internal goals? Perfectly, actually. By developing a lunar lander for NASA, Space X is simultaneously building the hardware needed for its own lunar base. The vehicle and systems designed for government missions become the foundation for private operations. It's the same spacecraft serving dual purposes.

This arrangement is increasingly common in modern spaceflight. NASA provides funding, certification requirements, and national prestige. Space X provides engineering, operations, and reusability innovation. The collaboration is synergistic.

The Artemis program is more ambitious than its 1960s namesake. The original Artemis was the brief, focused program that sent twelve astronauts to the Moon in just two years (1969-1972). Modern Artemis is designed for sustained presence. It includes lunar gateway stations, surface habitats, and long-duration missions.

Musk's pivot aligns Space X's commercial goals with NASA's government objectives. Both are moving toward sustained lunar presence. Both recognize that initial landings are just the beginning. The real goal is establishing infrastructure that supports long-term occupation.

The oxygen extraction research NASA funded and completed in 2023 is particularly relevant. NASA scientists developed and tested technology to extract oxygen from lunar regolith in a lab setting. The results were clear: viable extraction is possible. This isn't theoretical science. It's demonstrated engineering.

What this means for Space X is that lunar base planning can now include realistic assumptions about resource production. You're not speculating about whether oxygen extraction is possible. You're planning how to scale it, where to deploy it, and how to make it reliable.

The timeline alignment is also strategic. Artemis III in 2028 means NASA will have boots on the Moon within three years. Space X's lunar base development runs parallel and slightly faster. By the time NASA is planning longer missions, Space X's infrastructure might already be operational.

There's also a regulatory component. NASA's involvement means Space X operates within established frameworks for space operations. NASA provides guidance on everything from habitat design to radiation protection to waste management. This isn't bureaucratic obstacle. It's accumulated knowledge from decades of spaceflight.

International partners matter too. Artemis involves international cooperation. European, Canadian, and Japanese space agencies are contributing modules, equipment, and expertise. This international layer makes lunar development a truly global effort, not just an American company project.

The economic implications deserve attention. Government contracts provide stable funding. Space X can develop lunar infrastructure knowing it has revenue streams from NASA. Private operations can then expand that infrastructure for commercial purposes. Government subsidizes the initial investment. Private sector scales it.

The Oxygen Advantage: Why Lunar Resources Change Everything

Remember when Musk dismissed the Moon's oxygen advantage? That dismissal now seems shortsighted. Understanding why oxygen extraction matters requires getting into some basic chemistry and payload mathematics.

Rocket fuel comes in different types. Space X uses methane and liquid oxygen. Both have to be loaded at launch on Earth. For a Mars mission, you're looking at massive payloads. A vehicle capable of reaching Mars needs enough fuel to brake into orbit, descend to the surface, and return to orbit. That's a lot of fuel.

Here's the physics problem: fuel is heavy. If you're carrying all your fuel from Earth to Mars, your spacecraft has to lift that fuel mass. More fuel mass means bigger rockets, which require more fuel, creating a spiral. It's thermodynamically expensive.

Now imagine another scenario. You're going to Mars, but you're refueling on the Moon first. You don't need to carry as much fuel from Earth because you'll get more on the Moon. This dramatically reduces Earth launch requirements.

Lunar regolith contains oxygen at roughly 45 percent by mass. This isn't pure oxygen sitting in accessible form. It's locked into mineral compounds. Extraction requires energy and equipment. But the resource is abundant. The Moon's surface covers about 38 million square kilometers. The resource is essentially unlimited at the scales we're discussing.

The extraction process uses equipment called oxygen processing or ISRU (in-situ resource utilization) systems. A lunar base could include these systems, producing oxygen continuously. Over time, oxygen accumulates. This becomes fuel for deep space missions.

Let's put numbers to this. A Mars-bound spacecraft might need 100 tons of fuel. If you manufacture that on the Moon using local resources, you avoid shipping 100 tons from Earth. Every ton of Earth-derived supplies saves money, launch vehicle capacity, and energy.

Musk's earlier dismissal likely stemmed from confidence that Space X's rockets could handle the payload. They're powerful. But more powerful doesn't mean efficient. Using local resources is more efficient, regardless of rocket capability.

Water ice adds another dimension. Lunar ice exists in permanently shadowed craters, particularly near the poles. Water can be split into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis. That gives you two rocket fuels from one source. It also gives you drinking water and oxygen for life support.

The economic calculation is straightforward. Every kilogram you produce locally rather than shipping from Earth saves money. Over time, as a lunar base matures, local production costs decrease. The breakeven point occurs after you've amortized infrastructure costs. Long-term, producing supplies on the Moon beats shipping them from Earth.

There's also a resilience argument. If your Mars settlement depends entirely on Earth supply missions, system failures in Earth launch capability create existential risk. If your Mars settlement is supplied partly from local Moon production, you have redundancy. You're less dependent on Earth supply chains.

The technology to extract and process lunar oxygen is real, not speculative. NASA demonstrated it. The engineering to scale it up is challenging but solvable. Space X's pivot essentially acknowledges: we're going to need this technology developed and operational. Better to do it methodically on the Moon first than to improvise on Mars.

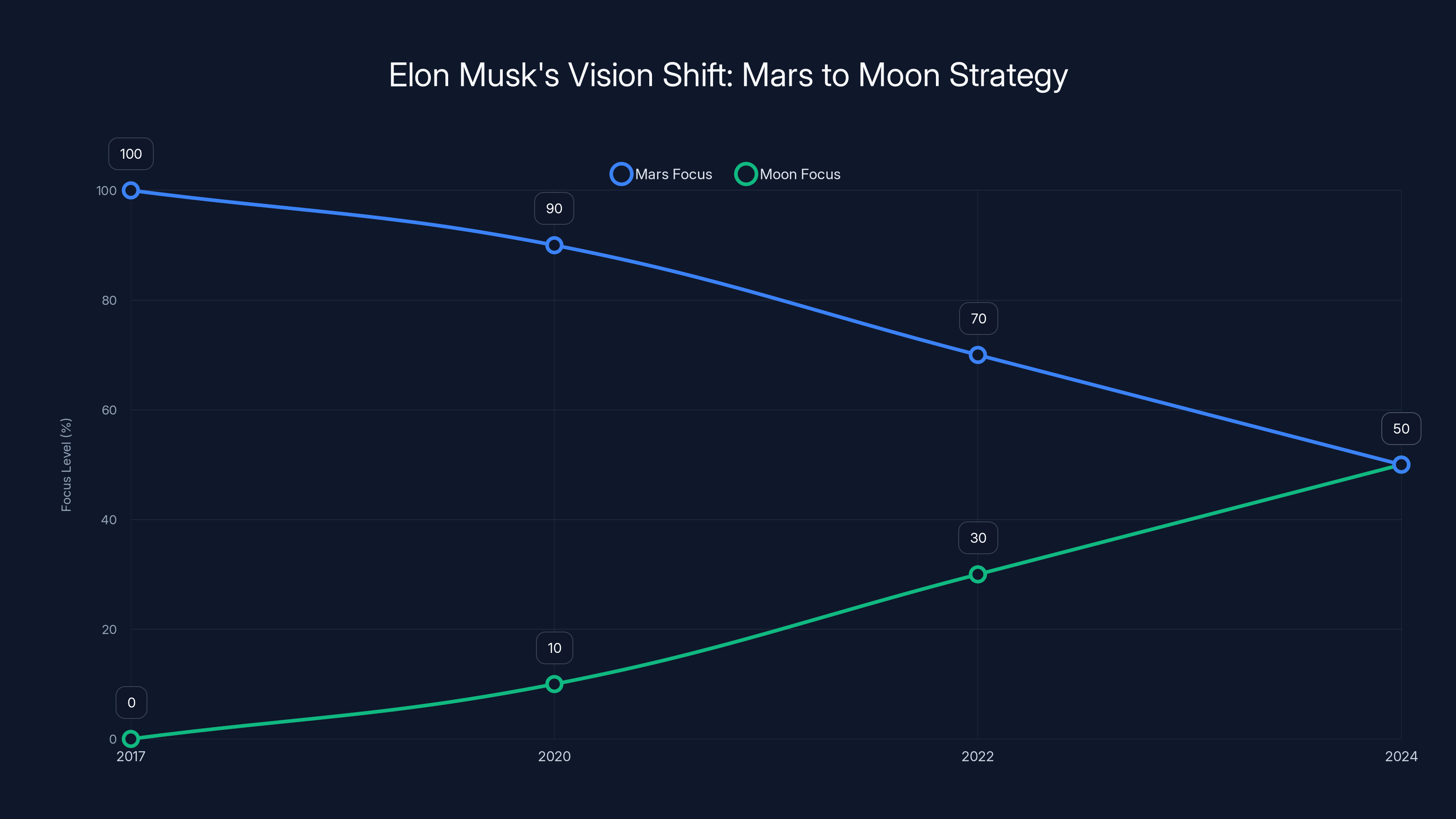

Elon Musk's strategic focus has shifted from a Mars-only approach to a balanced Moon-Mars strategy, reflecting engineering realities and strategic planning adjustments. Estimated data.

Timeline Realities: Is 10 Years Actually Feasible for a Lunar Base?

Musk claims Space X can build a self-growing city on the Moon in less than 10 years. This requires evaluation. Is it plausible?

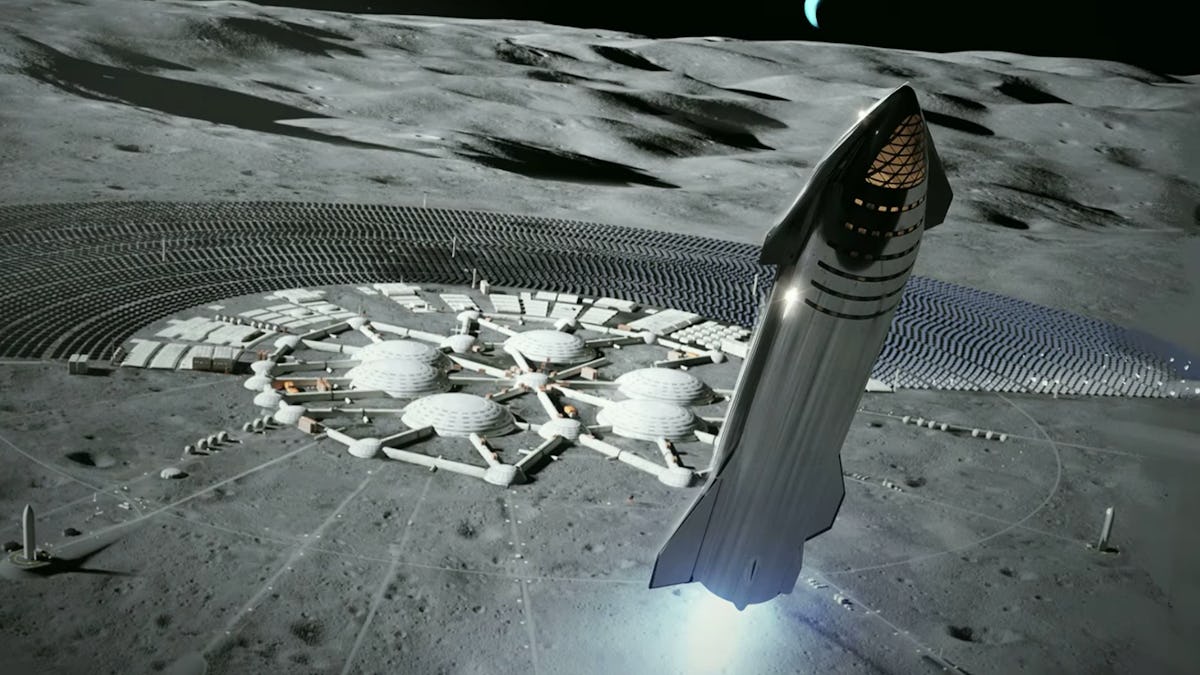

First, define "self-growing city." This likely means a habitat that can sustain human population, conduct scientific research, support resource extraction, and expand its own infrastructure. That's more complex than a simple outpost. It suggests autonomous or semi-autonomous systems, multiple modules, and redundant life support.

Ten years is 120 months. Building a city anywhere, let alone on the Moon, is extraordinarily complex. You need vehicles, habitat modules, power systems, life support, scientific equipment, water processing, oxygen production, and various other systems. Each component is itself a massive engineering project.

However, timelines have become faster in space. Space X built and tested Starship prototypes in years, not decades. Previous aerospace programs took longer partly because they operated with less efficiency, more oversight, and older supply chains. Space X operates differently.

The parallel development model Musk described is interesting. If work on Mars infrastructure runs simultaneously with lunar base construction, resources and learning flow both directions. Technologies proven on the Moon transfer to Mars vehicles. This speeds both development paths compared to doing them sequentially.

Breaking down a 10-year timeline helps assess feasibility. First two years: establish initial outpost with crewed landings, basic habitat, power systems, and life support. Next two years: expand habitat, begin ISRU experiments with oxygen extraction, conduct extended EVAs, and develop supply chain routines. Years five through seven: scale up ISRU production, establish multiple habitat modules, begin local construction with extracted materials, and test expanded mission profiles. Final years: build redundant systems, increase crew rotations, demonstrate full self-sufficiency in basic supplies, and construct facilities for rotating human presence.

This breakdown sounds ambitious but not impossible. Each phase builds on the previous one. Early landings prove the vehicle works and crews can function. ISRU experiments prove resource extraction at small scales. Scaling then becomes an engineering problem, not a capability problem.

Historical parallels provide perspective. The Apollo program landed humans on the Moon in less than a decade (starting from 1962). But Apollo had vast government funding, national competition driving urgency, and lower safety standards than modern missions. Modern development is more careful but also more efficient in some ways.

The real constraint is probably funding and political will. Engineering challenges are solvable if resources are adequate. Space X would need sustained investment, government partnerships, and commercial contracts. The company is working toward this. Artemis contracts provide government funding. Private investment interest in space is growing. It's plausible.

One crucial factor: what counts as "completion"? If completion means sustained human presence with self-sufficient resource production, 10 years is aggressive but possible. If it means a thriving settlement with thousands of residents, 10 years is too optimistic. Musk probably means the former—a functioning base that demonstrates the concept and provides the infrastructure for expansion.

Comparison to other major projects helps calibrate expectations. Large infrastructure projects like major tunnels, dams, or bridges take 5-10 years. A lunar city is more complex than those but benefits from Space X's experience and modern technology. 10 years is optimistic but not laughably so.

Mars Timeline Realignment: A 2031 Crewed Mission?

Musk mentioned a possible crewed Mars flight in 2031. That's six years away from 2025. Is a manned Mars mission possible in that timeframe?

Unmanned Mars missions are well-established. NASA has rovers operating now. Reaching Mars is proven. Getting humans there is a different problem.

A crewed Mars mission requires: a spacecraft capable of reaching Mars, systems to sustain a crew for the journey (months), landing capability that works on Mars, ascent vehicles to return, and all redundancy and safety systems. This is orders of magnitude more complex than robotic missions.

The absolute minimum timeline involves several crucial steps. First, you need a tested spacecraft. Starship is under development. Testing a crewed-capable vehicle through numerous orbital flights, then a lunar mission, then a Mars trajectory test might take 4-5 years minimum, assuming no major setbacks. Second, you need Earth-to-space logistics proving reliability. Third, you need to assemble hardware in orbit or on the Moon for a Mars mission.

A 2031 first crewed Mars flight would require launching in late 2028 or 2029 to arrive in 2030-2031. That gives roughly 3.5 years from now for design, testing, and assembly. For a first crewed mission, this is extremely aggressive.

However, Space X might define this differently. An uncrewed test mission reaching Mars doesn't require crew life support, is faster to complete, and would qualify as "a Mars flight." The first human landing might occur later.

Musk's track record on Mars timelines is... let's say inconsistent. He predicted a Mars base by 2024 in 2017. That didn't happen. Current predictions should be taken with significant skepticism.

But here's what's changed: Starship is real and approaching operational capability. Orbital refueling technology is being tested. In-space assembly is becoming routine. The foundational capabilities that didn't exist five years ago are now within reach.

A realistic reading is probably this: an uncrewed mission to Mars in the early 2030s is plausible. A crewed landing several years after that is more realistic. But Musk's optimism about timelines is famous, and he's been wrong before.

The Moon is significantly closer to Earth than Mars, making lunar missions more logistically feasible and flexible compared to the limited launch windows and vast distances involved in Martian missions.

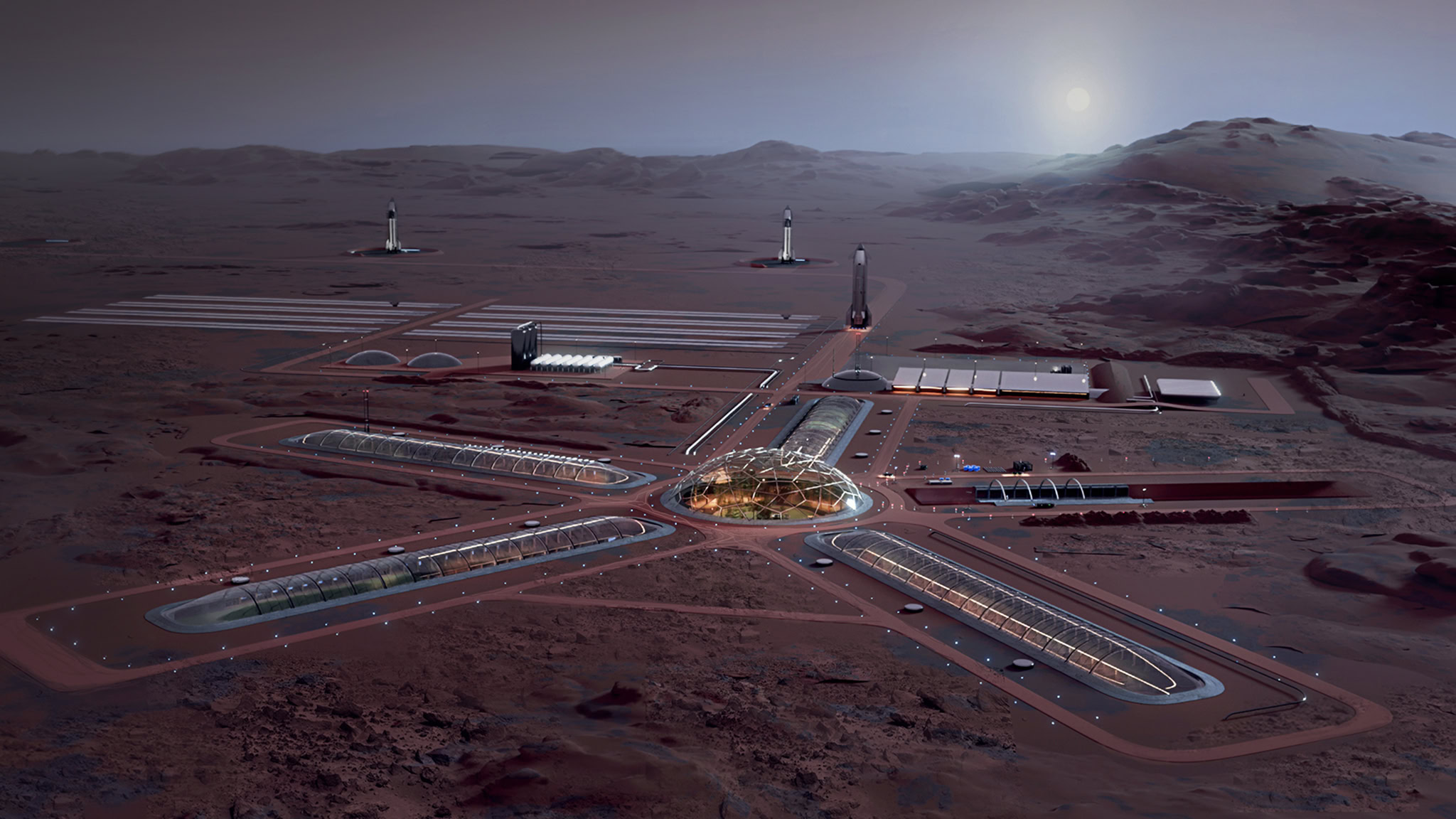

Building Infrastructure: What a "Self-Growing City" Actually Requires

What does "self-growing city" mean technically? It implies infrastructure that can expand itself, using local resources and minimizing dependence on Earth resupply.

Core systems needed include habitat modules providing radiation shielding, pressure maintenance, temperature control, and living space. Power generation systems, probably solar panels supplemented by nuclear for the long lunar night. Water extraction and processing systems that use ice from frozen lunar deposits. Oxygen production through regolith processing. Food production, probably through hydroponic systems. Medical facilities and scientific laboratories.

Beyond basics, a self-growing settlement needs construction equipment. Lunar concrete can be made from regolith. Robotic construction systems could build walls, roads, and structures. Mining equipment extracts resources. Processing plants refine materials. This all requires development and deployment.

Communications infrastructure includes antennas linking to Earth, internal networks, and eventually connections to other lunar facilities. Power distribution networks move electricity from generation to consumption points. Water and oxygen pipelines move processed materials to where they're needed. Waste processing systems handle human refuse and system byproducts.

The challenge with "self-growing" is that initial buildout requires supply from Earth. You can't bootstrap a settlement without launching everything first. Only after you've got basic infrastructure operational can local production meaningfully reduce Earth dependence.

This is why multiple cargo flights precede crewed missions. Robots, equipment, habitat modules, and supplies go first. This lays the foundation for crews to arrive to a partially functional facility.

Autonomous systems become essential at scale. Humans can't be everywhere simultaneously. Robots with human supervision can mine, process materials, and construct. Artificial intelligence controlling operations during the lunar night (which lasts about 14 Earth days) means work continues when human crews are sleeping or offline.

The concept of "self-growing" might actually mean that systems are designed to expand modularly. Adding another habitat module doesn't require a massive new investment. It just requires additional launched components assembled on the surface. Expansion becomes a matter of repeated deployment of proven modules rather than entirely new engineering.

The Role of Commercial Space Companies Beyond Space X

Space X isn't alone in pursuing lunar development. Other companies are moving toward the Moon too, reshaping how space infrastructure develops.

Blue Origin is developing Blue Moon, a lunar lander for cargo and crew. The company has national security contracts and is working toward crewed missions. Blue Origin's approach emphasizes large payload capacity and reliability over speed.

Reliance on established aerospace contractors like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman also matters. These companies are designing gateway stations, habitat modules, and life support systems for Artemis. They bring decades of human spaceflight experience.

Smaller companies are pursuing specific niches. Axiom Space is building commercial space station modules that could eventually be used off-world. Made In Space is developing manufacturing processes in orbit. Axiom, Intuitive Machines, and others are competing for lunar lander contracts.

The commercial lunar economy is beginning to form. Companies offering transportation, life support, power, communications, and other services on the Moon will enable long-term settlement. No single company does everything. The ecosystem of companies collectively builds infrastructure.

This competition benefits everyone. Multiple companies pursuing lunar access means more options, faster innovation, and redundancy if one company hits delays. Space X isn't creating a lunar monopoly. It's leading a trend that the entire industry is following.

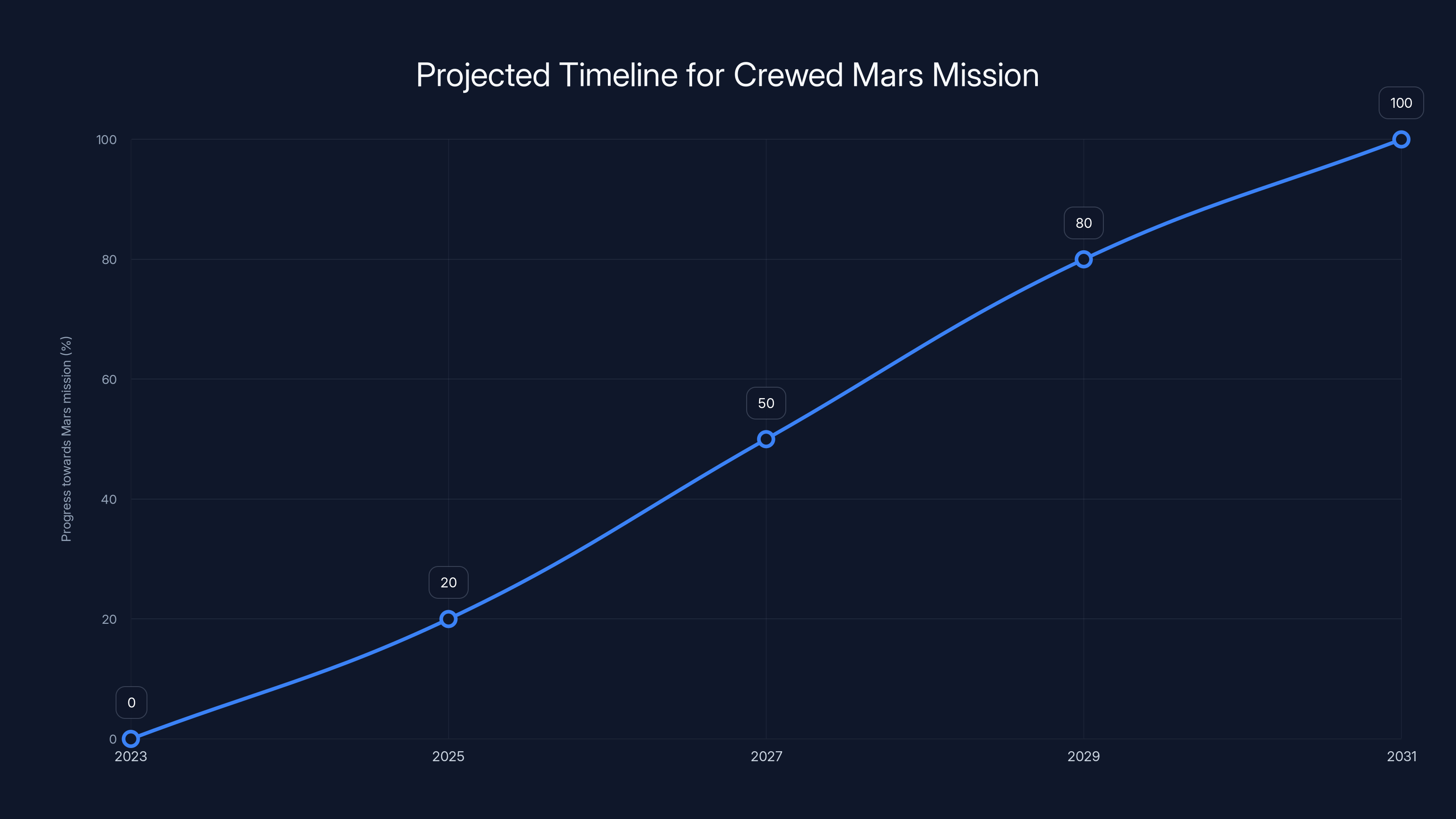

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in progress towards a crewed Mars mission, with significant milestones expected by 2031. The timeline is aggressive, given the complexity of required technologies.

Regulatory and International Considerations

Where jurisdiction authority lies on the Moon is complicated. International treaties govern space exploration. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 established that no nation can claim the Moon as territory. However, companies and nations can claim resources they extract.

For Space X, this means the company can build infrastructure and conduct operations, but within international law frameworks. Safety regulations, environmental considerations, and conflict of interest issues all apply.

Intentional cooperation with international partners becomes important. NASA involves international partners in Artemis. Space X will likely do the same for commercial operations. This improves relations, distributes costs, and builds institutional support.

There's also the question of property rights in space. Space X can claim resources it extracts and use infrastructure it builds. But ownership of real estate is less clear. Current frameworks treat space as a shared domain where use rights apply rather than ownership.

Rocketing space mining into practicality at scale will require updated regulations. As operations mature and resources become valuable, questions about extraction rights, environmental protection, and commercial monopoly prevention will need addressing. These regulatory frameworks are developing.

Scientific Discovery and Research Opportunities

A lunar base isn't just about infrastructure. It's a research platform. The Moon provides unique environment for studying geology, physics, and biology.

Lunar geology holds clues to planetary formation. Rock samples can be studied in situ and returned to Earth for detailed analysis. Understanding lunar composition informs theories about the Moon's origin and the early solar system.

The lunar environment itself is scientifically valuable. Radiation levels, temperature extremes, vacuum conditions, and low gravity provide conditions unavailable on Earth. Materials science experiments in this environment produce results impossible to achieve at home.

A crewed presence enables research that robots cannot. Humans make decisions, change approaches, and discover unexpected phenomena. A geologist on the Moon accomplishes more than rovers could in years.

Lunar research also benefits Earth. Understanding how to sustain human life in hostile environments has practical applications. Water extraction technology, power generation in extreme conditions, medical support for isolated environments, and autonomous systems all have terrestrial applications.

The Moon becomes a testing ground for technologies eventually deployed on Earth. It's a more challenging environment than most Earth locations, so if something works on the Moon, it generally works anywhere.

Refueling on the Moon can reduce the fuel mass required from Earth by 50%, significantly lowering launch costs and energy expenditure. Estimated data based on typical mission profiles.

Economic Models: How Lunar Development Gets Funded

Building a Moon base costs enormous amounts of money. Estimates range from tens to hundreds of billions of dollars depending on scope. How does this funding happen?

Government contracts provide the primary funding source initially. NASA awards contracts for lunar development. Space agencies from other nations do the same. These contracts fund specific capabilities: landers, habitats, life support systems, and so on.

Space X uses government contracts to develop capabilities that also serve commercial purposes. A lunar lander built for NASA can be used for private missions. Habitat modules developed for government work can support commercial operations.

Private investment increasingly funds space ventures. Companies raising capital through venture funding or public offerings can invest in lunar infrastructure. As opportunities emerge, commercial investors see potential returns.

Resource extraction is the eventual revenue model. Oxygen, water, and other resources extracted on the Moon can be sold to spacecraft en route elsewhere. A lunar fuel depot becomes profitable if enough deep space traffic exists. Currently, that traffic is hypothetical. But as more missions occur, it becomes real.

Tourism is another revenue stream, though not initially. Eventually, wealthy individuals might visit lunar bases. Tourism revenue could offset operational costs.

Scientific research funding represents another source. Universities and research institutions pay for access to lunar research facilities. This funds operations while advancing knowledge.

The business model evolves as infrastructure matures. Initially, everything is government-funded and experimental. As capabilities become reliable, commercial opportunities expand. The transition from purely exploratory to economically self-sustaining takes time.

Technology Development Pathways: From Today to Moon Base

What needs to happen technologically between now and a functioning lunar base?

Space X's Starship must prove reliable for crew transport. This requires numerous test flights, life support validation, and crew procedures development. The vehicle exists. Proving it works safely for humans takes time.

Lunar lander development continues. Space X's lunar Starship variant must be tested, refined, and validated. Landing large payloads on the Moon is difficult. Proving repeatability is essential.

Habitat modules need design and testing. These aren't simple structures. They must withstand thermal extremes, protect against radiation, maintain pressure, and support life indefinitely. Constructing prototypes and testing them is necessary.

Robotic systems require development. Autonomous equipment for mining, construction, and materials processing needs design and field testing. These aren't off-the-shelf products. They're being created specifically for lunar work.

Life support systems need advancement. Current International Space Station systems work fine for days or weeks. Lunar bases need systems reliable for months, with minimal maintenance and resupply. Technological maturation is ongoing.

Power systems need capacity. Solar panels work on the Moon but face challenges during the lunar night. Nuclear power systems are being considered. Whichever approach dominates, the systems need development, testing, and deployment.

Communications infrastructure must be deployed. Antennas, relay systems, and Earth-link equipment establish connectivity. This is relatively mature technology but requires deployment at scale.

Each of these technology pathways is pursuing multiple solutions. Competition drives innovation. What works best emerges through implementation, not theory.

The Political and Cultural Implications

A Moon base carries geopolitical weight. It signals technological capability, national leadership, and long-term vision. For Space X, it demonstrates American space leadership and private sector competence.

Culturally, lunar development shifts human imagination. Instead of space being a place for flags and footprints, it becomes home. That's different. It suggests permanence, civilization, and expansion beyond Earth.

The narrative matters. Musk's emphasis on a "self-growing city" appeals to humanity's expansion instinct. People find meaning in frontier expansion. That's powerful for motivation and public support.

There's also competition with other nations. China is pursuing lunar development. European and international programs are accelerating. America and American companies leading in these efforts carries strategic weight.

Public imagination matters for funding and support. A charismatic vision of lunar settlement attracts investment, talent, and political support. Mars settlement is the endgame dream, but the Moon is the near-term proof point.

Risks and Challenges Ahead

Lunar development faces substantial obstacles. Technical failures could cause delays. Budget overruns could reduce scope. Personnel losses in dangerous environments would be tragic and politically damaging.

The environment is harsh. Radiation exposure, dust effects on equipment and humans, temperature extremes ranging from -170°C to 120°C, and vacuum conditions all create challenges. Mitigating these requires constant vigilance.

Equipment failure on the Moon is serious. Repair options are limited. Redundancy becomes essential, but it adds cost and complexity. Designing systems for lunar conditions where testing is limited is difficult.

Human factors matter. Isolation, confinement, and distance from home create psychological challenges. Crews need selection, training, and support. Medical emergencies 240,000 miles from the nearest hospital require self-sufficiency.

Budget reality might constrain ambition. If costs exceed expectations, scope gets cut. This might mean slower progress or reduced capability. Managing expectations becomes politically important.

Schedule slips are nearly inevitable. Space projects historically run behind timelines. The optimistic 10-year projection might actually take 12-15 years. That's not failure. That's reality.

Looking Forward: Moon as Stepping Stone to Mars

The fundamental truth underlying Space X's pivot is that Mars settlement requires solved problems. The Moon provides the place to solve them.

Having infrastructure on the Moon, proven systems, extracted resources, and established supply chains makes Mars feasible. Without that groundwork, Mars becomes an aspirational dream rather than a practical goal.

Musk's statement that Mars development runs parallel to lunar work suggests the company is pursuing both but with lunar development taking priority focus. This is sensible sequencing. You test at the nearer location first.

The technology developed for the Moon transfers to Mars. Life support systems, habitat design, power generation, mining and processing equipment—all get tested at scale on the Moon. Lessons learned transfer directly to Mars applications.

The settlement timeline shifts. Instead of trying to crack Mars directly, Space X is recognizing that sustained human presence requires building up incrementally. The Moon is intermediate, providing accessible location for infrastructure that later serves Mars.

This represents maturity in vision. Romantic dreams of Mars colonization are compelling, but pragmatic engineering recognizes prerequisites. The Moon supplies those prerequisites.

For humanity's future, lunar development matters enormously. The Moon becomes the proving ground for off-world settlement. Success here enables everything that follows.

Five, ten, or twenty years from now, when humans are living and working on the Moon, conducting research, extracting resources, and sustaining themselves, this pivot will seem obvious in hindsight. The fact that Space X is now prioritizing this represents a shift from aspirational thinking toward practical execution.

FAQ

Why is Space X shifting focus from Mars to the Moon?

Space X is prioritizing the Moon because it offers significant logistical advantages over Mars. The lunar location allows for regular resupply missions, faster launch windows, and proven resource extraction potential. Building a lunar base provides a testing ground for technologies and life support systems needed for Mars settlement, making Mars colonization ultimately more feasible when undertaken after lunar infrastructure is established. The shift reflects practical engineering realities rather than abandoning Mars entirely.

What is a "self-growing city" on the Moon?

A self-growing city on the Moon refers to a settlement that can sustain human inhabitants, expand its own infrastructure using local resources, and minimize dependence on Earth supply missions. This includes habitat modules, power generation systems, water and oxygen production facilities, mining equipment, and autonomous construction systems. The term implies modular expansion where additional resources extracted locally enable construction of new structures without requiring massive new investments from Earth.

How will Space X extract oxygen from the Moon?

Oxygen extraction from lunar regolith uses in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) technology, which NASA proved viable in 2023. The process involves heating lunar soil to extract oxygen locked within mineral compounds, then storing or using it for fuel production, life support, or propellant. Since lunar regolith contains approximately 45 percent oxygen by mass, this resource is essentially unlimited at the scales needed for human settlement and fuel production for deep space missions.

What role does NASA play in Space X's lunar strategy?

NASA and Space X collaborate through the Artemis program, where Space X is developing the lunar lander for NASA crewed missions planned to land on the Moon by 2028. This partnership provides government funding for hardware development while Space X uses the same vehicles and infrastructure for its own commercial lunar operations. The collaboration aligns government objectives with Space X's business strategy, making lunar development economically viable.

When will humans actually land on the Moon again?

NASA's Artemis III mission is planned for 2028, which will land humans on the Moon for the first time since 1972. Space X's crewed lunar base timelines suggest sustained human presence could begin during this same period, with expansion continuing over the following years. Space X's independent crewed missions may occur slightly later after proving systems through cargo deliveries and uncrewed validation flights.

How does the Moon serve as a waypoint to Mars?

The Moon serves as an intermediate proving ground for Mars technologies and a source of resources. Life support systems, habitat designs, power generation, and mining equipment can be tested on the Moon before deployment on Mars. Additionally, producing fuel and water on the Moon reduces the payload requirements for Mars missions significantly. The Moon's proximity to Earth also allows for rescue operations and rapid resupply, making it safer for developing and testing critical capabilities.

What makes launching to the Moon easier than reaching Mars?

Launch windows to the Moon can occur almost any day, while Mars launch windows open only every 26 months. The Moon's distance of 240,000 miles allows supply missions in days, whereas Mars is 34 to 250 million miles away, with supply missions taking months. The Moon's relative proximity enables rapid iteration, equipment repair, and rescue operations that are impossible for Mars destinations. This flexibility makes lunar development more efficient and lower-risk than attempting direct Mars settlement.

Is a 10-year timeline for a lunar base realistic?

A 10-year timeline for establishing a functioning lunar base is ambitious but not impossible. It requires breaking development into phases: initial crewed landings and basic habitat establishment in years 1-2, expansion and ISRU experimentation in years 3-4, scaling and redundant system development in years 5-7, and full operational capability by year 10. Space X's rapid development pace and access to government funding through Artemis contracts make this challenging but achievable timeline plausible, though historical space projects typically experience delays.

What happens to Mars exploration in this new strategy?

Mars exploration continues in parallel with lunar development. Space X stated that Mars work will run simultaneously with lunar base construction, expected to begin in 5-6 years. However, a first crewed Mars landing will likely occur after lunar infrastructure is operational, probably in the early 2030s. This sequencing allows knowledge, technology, and resources from the Moon to inform Mars missions, making eventual settlement more viable than attempting Mars colonization without prior lunar development experience.

Who are other companies pursuing lunar development besides Space X?

Multiple companies are advancing lunar capabilities. Blue Origin is developing the Blue Moon lunar lander for cargo and crewed missions. Axiom Space designs habitat modules for orbital and eventually lunar deployment. Intuitive Machines and other companies compete for NASA lunar transportation contracts. This competitive ecosystem accelerates innovation and provides redundancy, ensuring that multiple pathways to sustained lunar presence exist rather than relying on a single company.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX is prioritizing a lunar base within 10 years over direct Mars settlement, driven by logistical advantages and resource availability

- The Moon's proximity to Earth enables frequent resupply missions every few days, versus Mars's 26-month launch windows limiting opportunities

- Lunar regolith contains 45% oxygen by mass, which NASA proved extractable in 2023, potentially reducing Mars payload requirements by half

- SpaceX's strategy aligns with NASA's Artemis program, where SpaceX develops the lunar lander for government crewed missions beginning 2028

- A 'self-growing city' on the Moon requires modular habitat expansion, autonomous mining equipment, ISRU production facilities, and redundant life support systems

Related Articles

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

- NASA Crew-12 Mission to ISS: Everything About February 11 Launch [2025]

- SpaceX Starship Upper Stage Malfunction: Launch Recovery Timeline [2025]

- Elon Musk's Orbital Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]

- SpaceX's Starbase Gets Its Own Police Department: What It Means [2025]

![SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-s-moon-base-strategy-why-mars-takes-a-backseat-in-202/image-1-1770647775809.jpg)