Introduction: Why Ocean Data During Hurricanes Actually Matters

Here's the thing: we're spending billions studying hurricanes, but we're still flying planes directly into them to collect data. Meanwhile, the ocean itself—the thing hurricanes feed on—remains basically mysterious during the storms that matter most.

That's where Oshen comes in. The company just did something that sounds like science fiction: deployed autonomous ocean robots that survived a Category 5 hurricane and collected continuous data the entire time. Not before the storm. Not after. During.

This isn't just a neat engineering trick. It's the kind of breakthrough that changes how we understand extreme weather systems, predict hurricane behavior, and prepare coastal communities for increasingly severe storms.

Anahita Laverack started Oshen in 2022 after a realization that hit her at an autonomous robotics competition. She was trying to send micro-robots across the Atlantic, but they kept failing. The technical challenges were brutal, sure. But there was something deeper: nobody had enough ocean data to even model weather conditions properly. The data gap was so big that researchers and defense agencies actually asked her to collect it.

That conversation transformed into a company. Four years later, Oshen has government contracts across multiple countries, robots that can operate autonomously for 100 days in extreme conditions, and proof that autonomous systems can do what manned missions struggle with: stay in place and observe.

This article breaks down how Oshen built this technology, why it matters, what they're doing now, and what autonomous ocean systems mean for climate science and disaster response.

TL; DR

- First autonomous robots to collect data in Category 5 hurricanes: Oshen's C-Star robots survived Hurricane Humberto and transmitted continuous data throughout the storm

- Fills a critical data gap: Ocean conditions during hurricanes have been largely unmeasured, limiting forecast accuracy and storm understanding

- Government-backed deployments: Oshen has contracts with NOAA, U. K. government, and defense agencies for weather and operational intelligence

- Swarm-based approach: Instead of deploying single expensive sensors, Oshen releases fleets of cheap, mass-producible robots

- 100-day autonomous operation: C-Star robots operate independently for extended periods without human intervention or maintenance

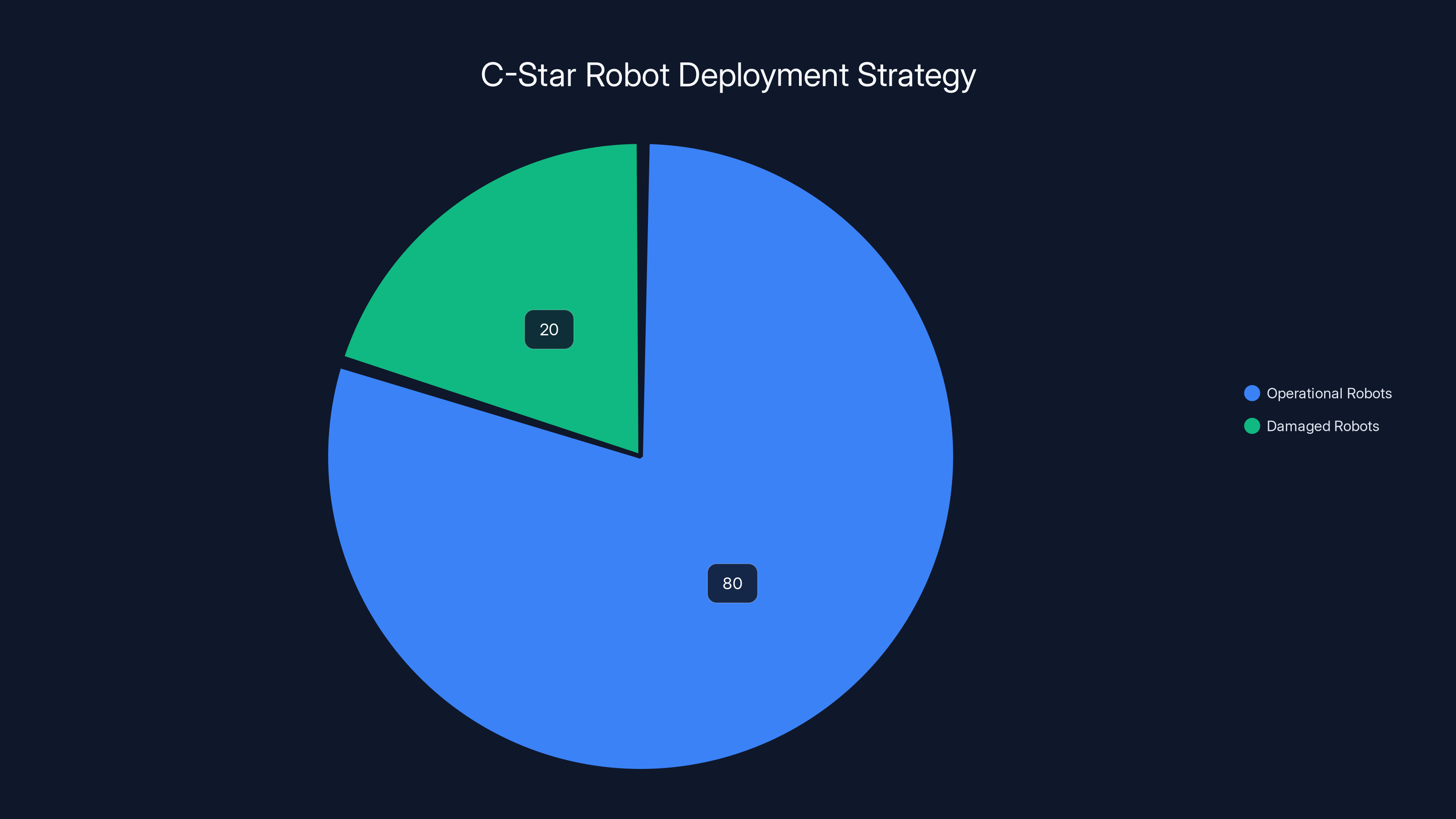

In a typical deployment of five C-Star robots, approximately 80% remain operational while 20% may be damaged, showcasing the system's redundancy and resilience. (Estimated data)

The Problem: Why Ocean Data During Storms Is Nearly Nonexistent

When a hurricane forms, meteorologists can see it on satellite. They know wind speeds. They know pressure drops. They can even predict its path with decent accuracy these days.

But they have almost no idea what's happening in the water beneath the storm.

This sounds strange until you think about it from a practical standpoint. Measuring ocean conditions during extreme weather means sending a person or instrument into conditions that could easily destroy both. Manned aircraft can fly into hurricanes because pilots can maneuver and escape. But permanently placed sensors? Buoys? They just sit there and potentially break.

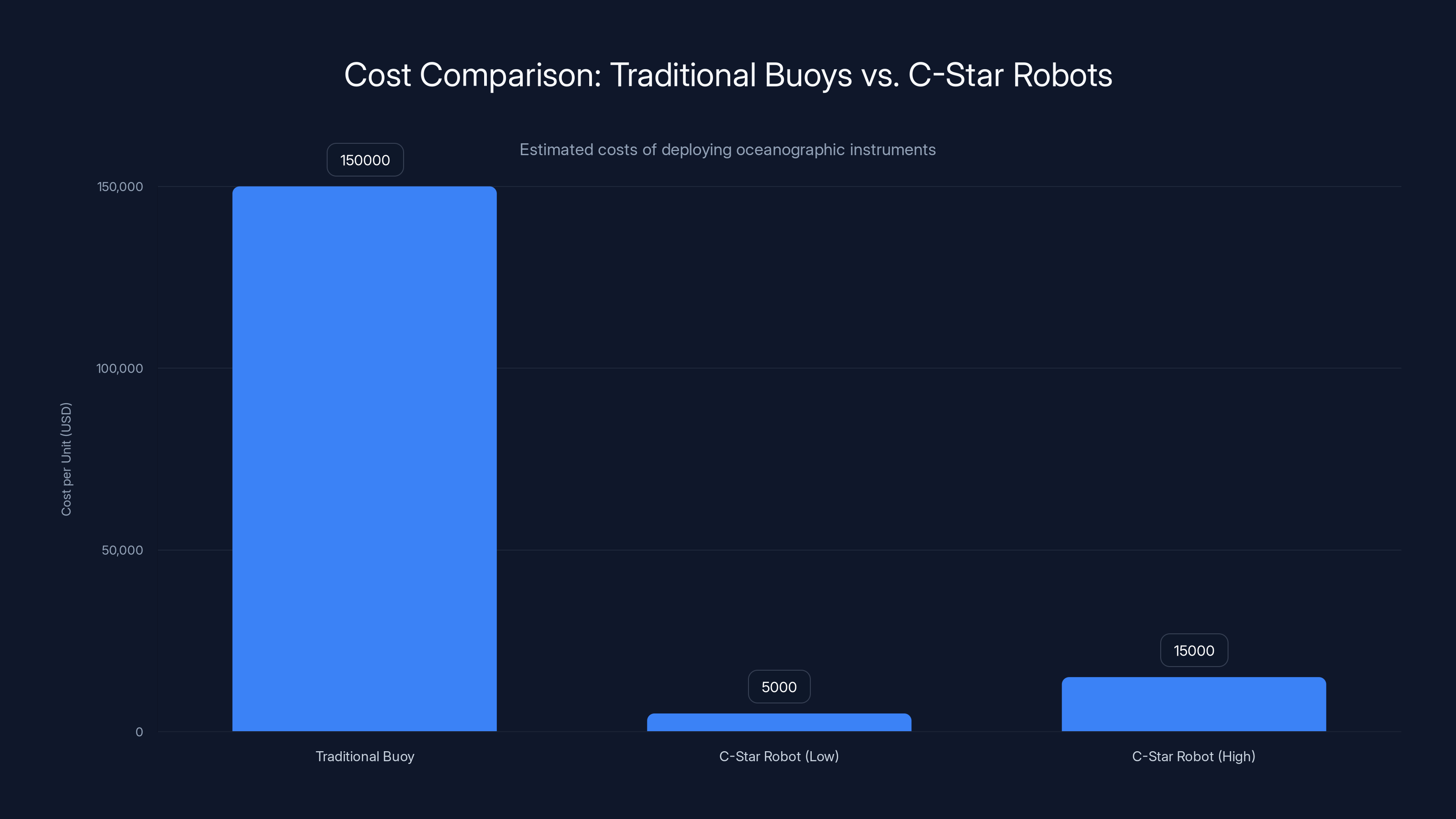

Traditional buoy deployments cost tens of thousands of dollars per unit. The technology is valuable, which means organizations are reluctant to risk them in situations where the equipment might be destroyed. So ocean observations during major storms remain sparse, fragmented, and often incomplete.

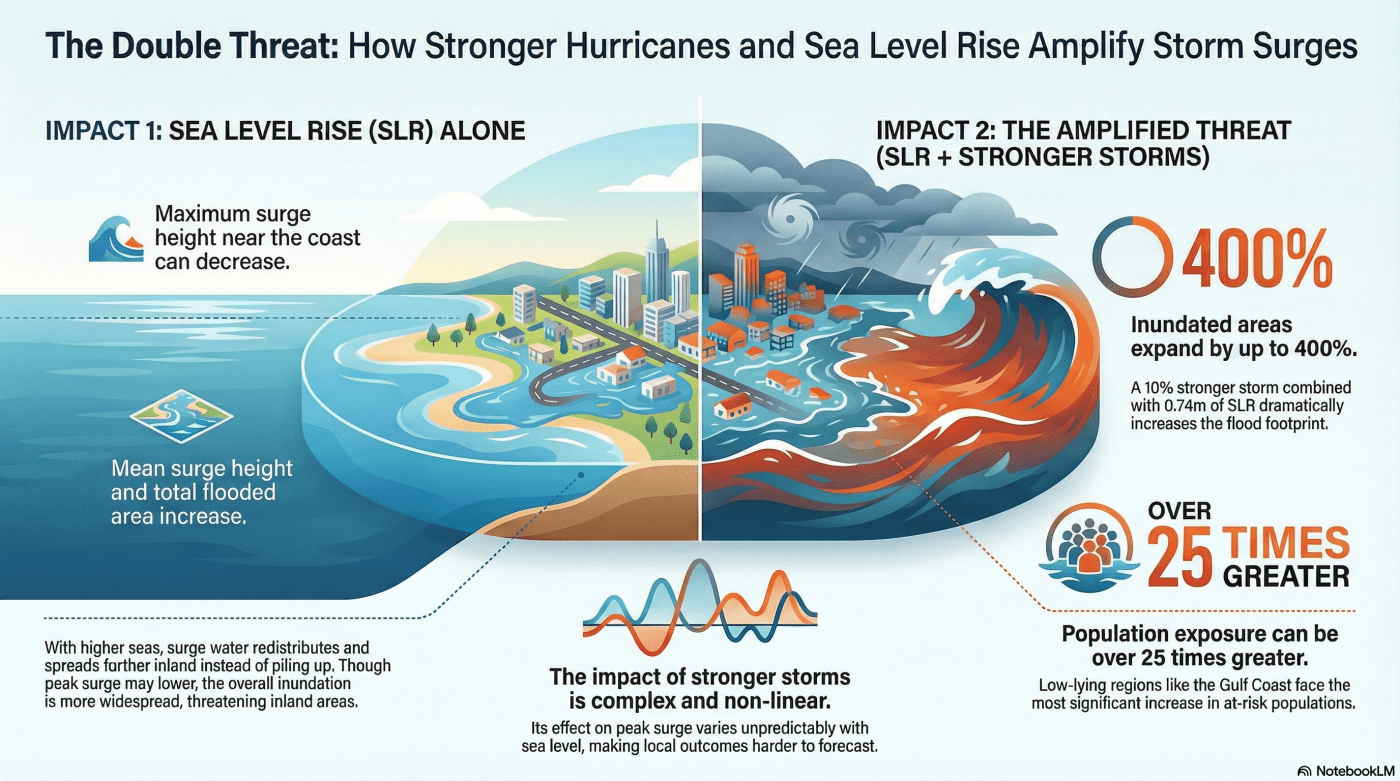

The data gap creates downstream problems. Hurricane forecast models are trained on incomplete information about ocean conditions. We don't really know how sea surface temperatures influence hurricane intensification during the storm itself. We're missing real-time feedback about how the ocean responds to hurricane forcing.

For climate science, this is huge. Understanding the ocean-atmosphere interaction during extreme weather events directly impacts our ability to predict how warming oceans will affect future hurricane behavior. Right now, we're making those predictions with incomplete observational data.

Laverack recognized this gap while attending industry conferences like Oceanology International. She wasn't looking for a business opportunity. She was looking for data. But everywhere she went, researchers told her the same thing: "Can you collect this data? We'll pay for it."

That repeated request was the actual business signal that Oshen was built on.

C-Star robots offer a cost-effective alternative to traditional buoys, with prices ranging from

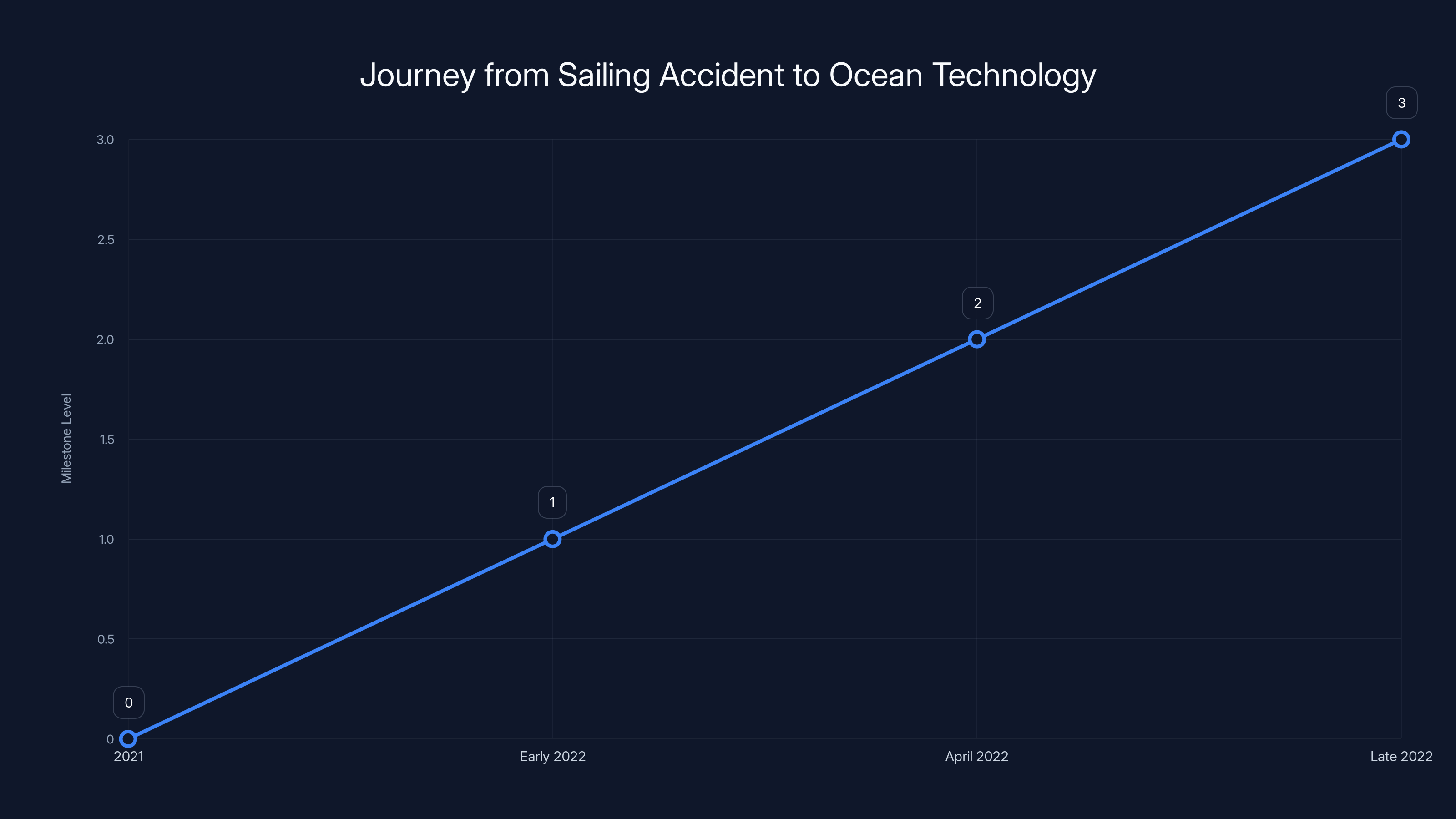

The Founder Story: From Sailing Accident to Ocean Technology

Anahita Laverack wasn't supposed to build ocean robots. She was training to be an aerospace engineer. The transition happened almost by accident.

In 2021, Laverack entered the Microtransat Challenge, an autonomous sailing robot competition where teams send tiny, self-guided boats across the Atlantic Ocean. It's one of the harder robotics challenges in existence. The robots need to survive weeks at sea, navigate storms, handle saltwater corrosion, manage power systems far from home, and reach a distant goal entirely on their own.

She failed. So did everyone else that year.

But her failure led to a different kind of success. While debugging why her robot crashed, she realized two things were happening simultaneously. First, yes, making micro-robots survive the ocean is genuinely hard. Materials corrode, electronics fail, storms break things.

But second, and more important: even if she'd succeeded technically, her robot wouldn't have had enough environmental data to navigate properly. It didn't know where the good winds were. It didn't know ocean current patterns. It couldn't make smart routing decisions because the data simply didn't exist at the resolution she needed.

This realization spiraled into conversations across the oceanography and meteorology communities. Laverack started asking researchers what data they needed. The answers were consistent: high-resolution ocean observations, particularly during extreme events, in locations where traditional monitoring was impossible.

She partnered with Ciaran Dowds, an electrical engineer, and they founded Oshen in April 2022. Rather than chase venture capital immediately, they made a deliberate choice to bootstrap and stay lean.

They bought a 25-foot sailboat. They moved to the cheapest marina they could find in the U. K. They used the boat as their testing platform and lived aboard it while building the company. This wasn't a romantic startup narrative—it was a practical decision. They needed to test robots in realistic conditions, and living on the water meant they could iterate rapidly, launch tests whenever weather permitted, and control costs.

The two-year testing phase forced them to solve problems that laboratory work would have missed. Getting a robot to work in calm summer conditions is one problem. Getting it to survive and operate in winter Atlantic storms is a completely different category of challenge.

Laverack mentioned later that testing in winter storms on a 25-foot boat created some "interesting events" she wouldn't detail. This is consultant-speak for "we nearly died several times," but it was exactly this push against real conditions that built the robustness Oshen would eventually become known for.

How C-Star Robots Work: The Engineering Behind Autonomous Ocean Data Collection

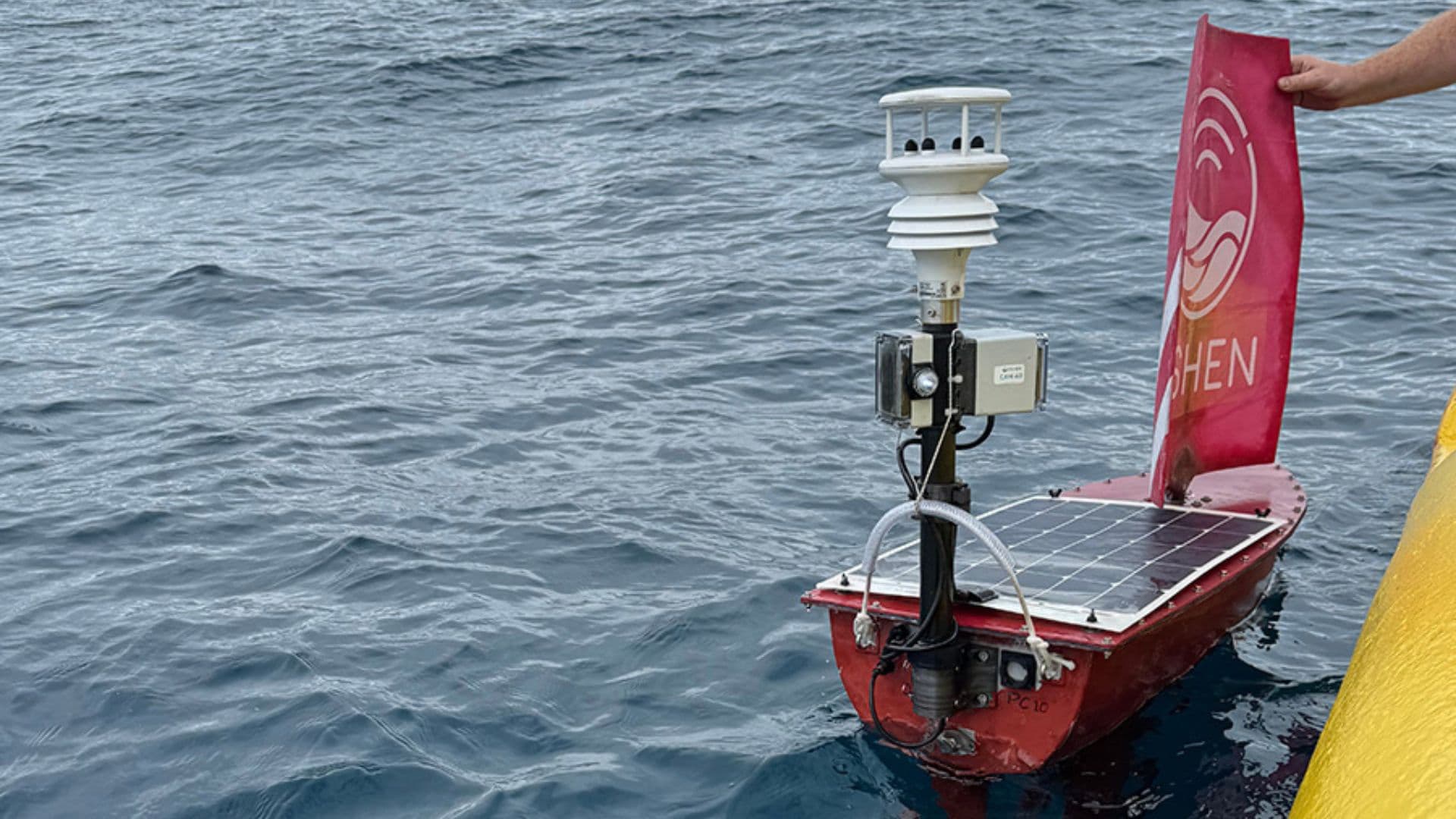

Oshen's core product is the C-Star, a small autonomous ocean robot designed for mass deployment. Understanding how it actually works requires thinking about robotics, marine engineering, and data science differently than you might expect.

First, the basic concept: C-Star robots are not individual super-intelligent units. They're simple, relatively inexpensive, and designed to be deployed in swarms. Rather than having one

Each C-Star combines several key systems. There's a hull designed to handle extreme pressure and saltwater corrosion. There's a power system—typically a combination of solar panels and batteries—that needs to provide sufficient energy for 100 days of continuous operation. There's a sensor array measuring oceanographic variables like temperature, salinity, pressure, and current velocity. And there's a communication system that transmits data back to shore via satellite or cellular networks when the robot surfaces.

The design challenge isn't making one advanced robot. It's making a robot that's simple enough to manufacture at scale, cheap enough to deploy in quantity, and robust enough to survive conditions that would destroy traditional oceanographic instruments.

Traditional oceanographic buoys achieve robustness through over-engineering: extra-thick hulls, redundant systems, expensive materials. This works fine when you're deploying one $150,000 instrument. It doesn't work when you want to deploy fifty robots and recover whatever data you can.

Oshen's approach flips this. Instead of one super-robust system, deploy many good-enough systems. If one robot breaks, the others still collect data. If half the swarm gets damaged but keeps operating, you've still got continuous observations. The system becomes robust through redundancy rather than individual unit sophistication.

This is mathematically elegant. If each robot has a 70% probability of surviving a hurricane and continuing to operate, and you deploy five robots, your probability of having at least one functional unit rises to over 99%. This is why the Humberto deployment had five robots: redundancy was baked into the deployment strategy from the start.

The robots use solar charging when conditions permit, and battery power during storm surge conditions when light is blocked. Oshen had to solve power management problems that most roboticists never encounter: how do you keep systems operating when the environment is so dark and violent that solar charging becomes negligible?

Data transmission happens opportunistically. When the robot surfaces or is near a communication window, it transmits collected data. This creates intermittent but complete data records rather than continuous streaming. For ocean monitoring, this is actually ideal because you care about what the system observed, not real-time streaming.

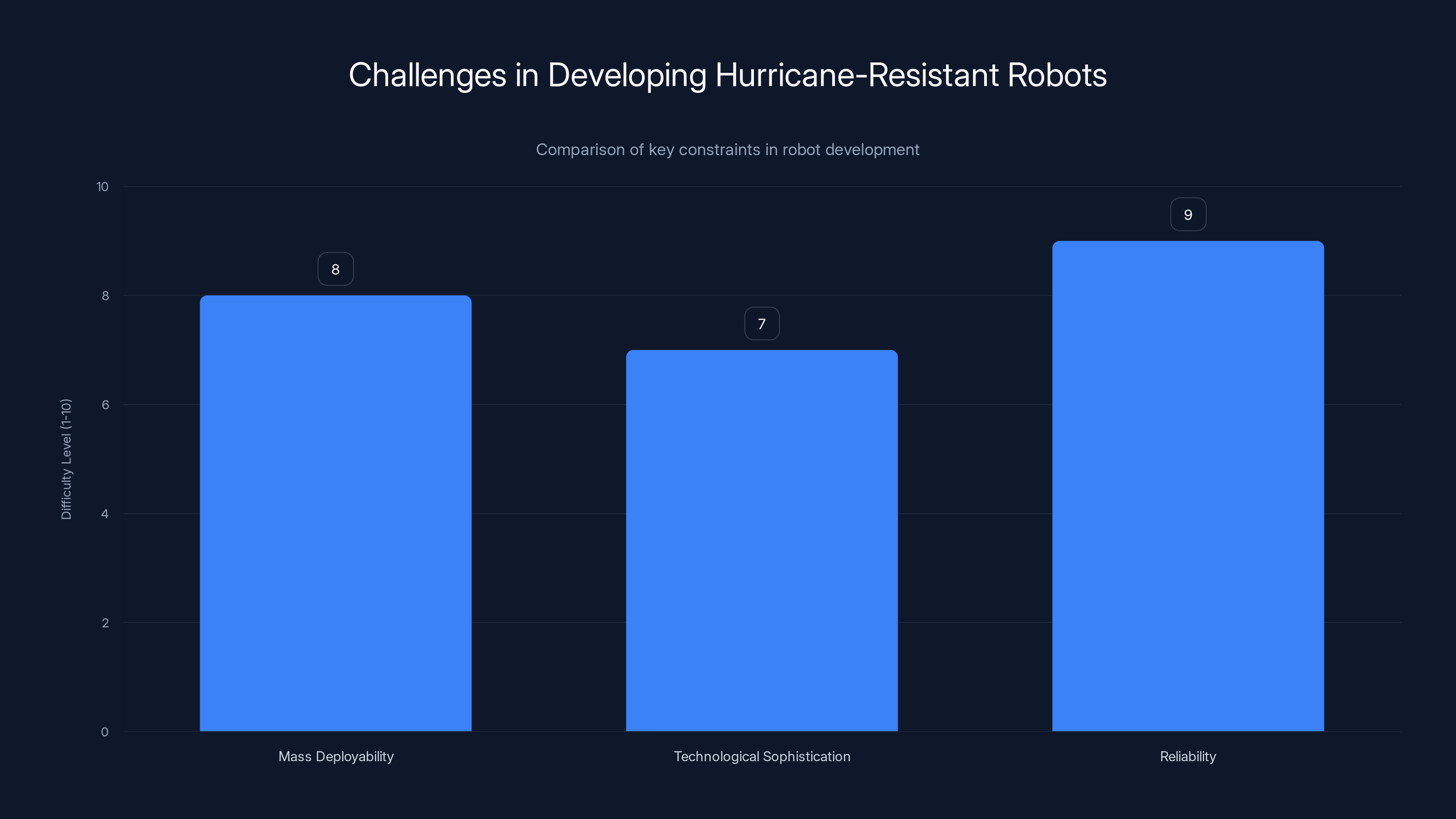

Mass deployability and reliability are the most challenging aspects in developing hurricane-resistant robots, with reliability being the most difficult to achieve. Estimated data.

Hurricane Humberto: The First Test in Extreme Conditions

The real-world test came faster than expected. In 2024, NOAA reached back out to Oshen. The organization had considered the robots for deployment two years earlier but concluded the technology wasn't ready. Over that time, Oshen had made significant improvements—especially after testing through U. K. winter storms, which are the closest you can get to extreme conditions without an actual hurricane.

When NOAA called again, it was two months before the 2025 hurricane season. They wanted to try deployment during actual hurricane activity.

Oshen responded by building and shipping over 15 C-Star robots in rapid turnaround. Five of these were positioned ahead of Hurricane Humberto, placed strategically at coordinates where NOAA predicted the storm would travel.

The team expected the robots to collect data leading up to the hurricane, then get overwhelmed when the storm arrived. That's what traditional instruments do—they measure the lead-up, then go offline when conditions exceed their specifications.

Instead, three of the five robots not only survived the entire hurricane but continued collecting data throughout. They lost some parts—sensors can get damaged, external components can break—but the core systems remained operational and transmitting.

When the data came back and Oshen analyzed what they had, it became clear: these were the first autonomous robots to collect continuous data through a Category 5 hurricane.

The data itself was valuable. Researchers got continuous observations of ocean temperature, salinity, pressure, and velocity changes as the hurricane passed directly over the sensor locations. They saw how the ocean responded to the extreme forcing in real-time rather than before and after the storm.

But perhaps more important than any single data point was the proof of concept. Autonomous systems could do this. They could survive extreme conditions that ground-based sensors couldn't. They could stay in place and observe rather than having to retreat.

This fundamentally changes what's possible in hurricane research.

The Technical Challenges Nobody Talks About

Getting a robot to survive a hurricane is harder than it sounds because the problems are not what you might expect.

Yes, high winds and waves break things. Yes, saltwater corrodes materials. Yes, pressure from storm surge can damage sensors. These are real problems, but they're not the hardest problems.

The harder problem is scale. Laverack mentioned this explicitly: you can't just take an existing oceanographic robot and shrink it down. The physics doesn't work that way. Materials that perform fine at large scales become brittle at small scales. Power systems that work for one robot become proportionally less efficient for many robots. Manufacturing complexity doesn't scale linearly.

Oshen had to solve for three constraints simultaneously:

First, mass deployability. The robots need to be cheap enough to deploy in quantity. If each robot costs $100,000, organizations will only deploy a handful. Oshen's target was getting costs low enough that deploying 50 robots was economically sensible. This forced decisions about materials, manufacturing, and component selection that traditional high-end oceanographic instruments never face.

Second, technological sophistication. Despite being cheap and simple, the robots need to be advanced enough to operate autonomously for 100 days, manage their own power systems, collect high-quality data, and transmit it reliably. This is the core engineering tension: simple but sophisticated.

Third, reliability. Mass deployment only works if the individual units are reliable enough that the system as a whole works even with component failures. You're not trying to make each robot 100% reliable. You're trying to make the fleet reliable enough to deliver value.

Laverack said that "many other companies have successfully gotten two of the three correct." That's actually a useful insight into why Oshen succeeded where others haven't. You can build cheap simple robots, but they won't collect useful data. You can build sophisticated data collection platforms, but they're too expensive to deploy in swarms. Balancing all three is where real innovation happens.

The technical execution involved solving problems in materials science (what plastics and metals resist saltwater corrosion over 100 days), power systems (how to maximize energy capture and minimize consumption), sensor engineering (how to collect high-quality data in compact form), and communication systems (how to transmit data reliably from the middle of the ocean).

Each of these is its own discipline. Oshen had to become competent in all of them simultaneously.

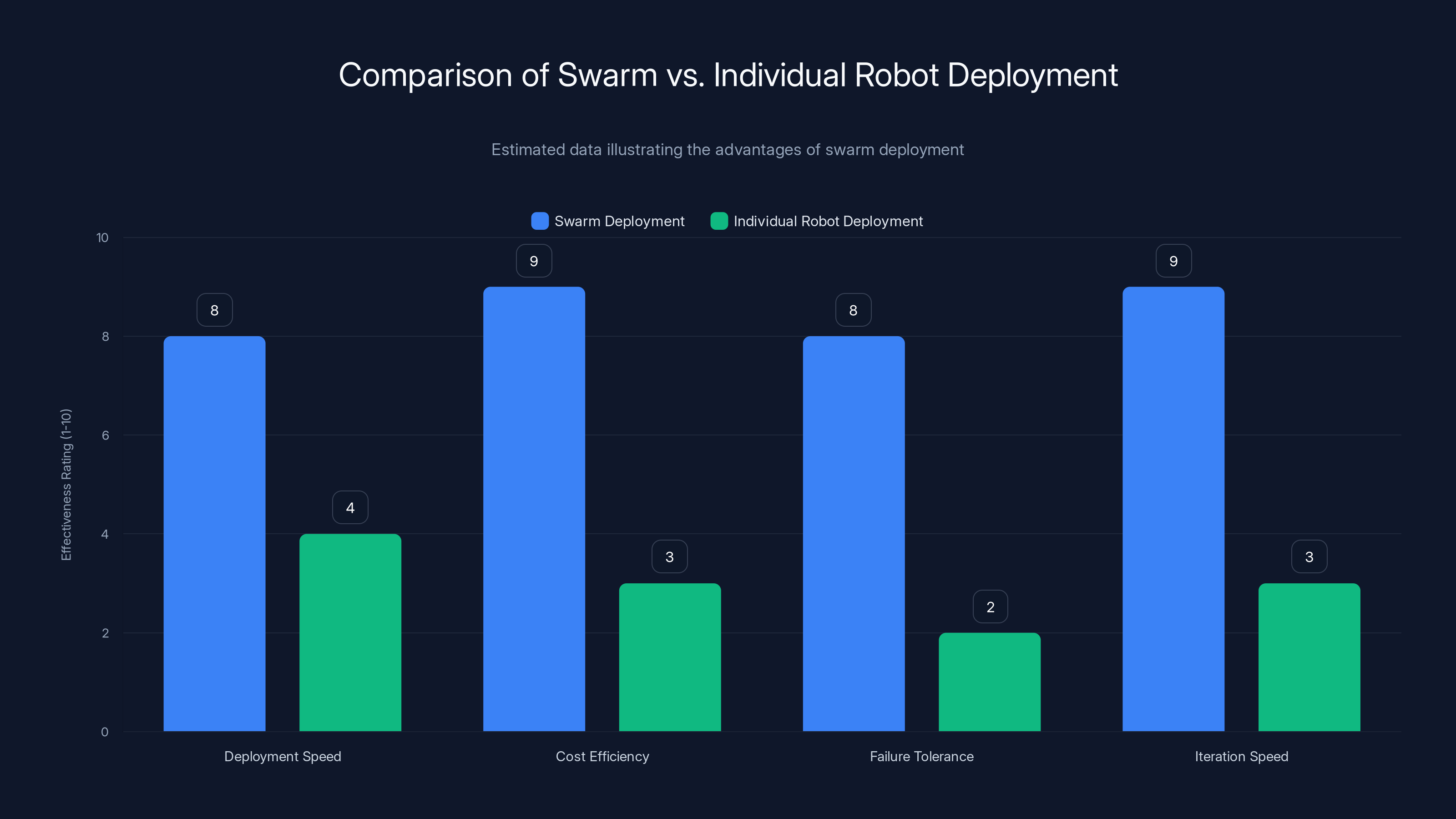

Swarm deployment offers significant advantages in speed, cost, failure tolerance, and iteration speed compared to individual robot deployment. Estimated data highlights these benefits.

The Business Model: From Bootstrapped Startup to Government Contracts

Oshen's path to revenue is instructive for hardware startups in climate and environmental tech.

The company didn't start by trying to raise massive venture capital. Laverack and Dowds bootstrapped with their own savings, lived frugally, and focused on building a product that solved a real problem. This forced lean decision-making and kept them focused on customers rather than investor narratives.

Once they had working prototypes and compelling proof of concept, the customer acquisition path became clear: government agencies and defense organizations with direct needs for ocean data.

NOAA became a major customer. The organization runs the National Weather Service and depends on accurate hurricane forecasting. Better ocean data during storms directly improves forecast models, which saves lives. That's a direct ROI story that justifies the investment.

The U. K. government signed contracts for weather operations. Other defense agencies followed. These aren't customers looking for flashy innovation—they're organizations with specific requirements, budgets allocated for specific purposes, and the ability to commit to multi-year contracts.

This is fundamentally different from the typical venture-backed startup path, which usually involves raising capital, building products for speculative markets, and hoping to achieve product-market fit. Oshen did the reverse: found the product-market fit first, then scaled the customer base.

Laverack mentioned that the company plans to raise venture capital soon to keep up with demand. This makes sense at this stage. They've proven the product works, they have contracts with government agencies, and they've demonstrated the technology can survive the most extreme conditions. These are the preconditions that make venture capital actually useful rather than just capital chasing ideas.

The funding round will be used for something specific: manufacturing scale-up. Moving from prototyping and small-batch deployment to mass production requires capital for tooling, manufacturing infrastructure, and working capital to build inventory ahead of customer orders.

That's a very different use of capital than a typical early-stage startup, which might use funding for team expansion or product development. Oshen knows what it's building and how to build it. It just needs to build more of it faster.

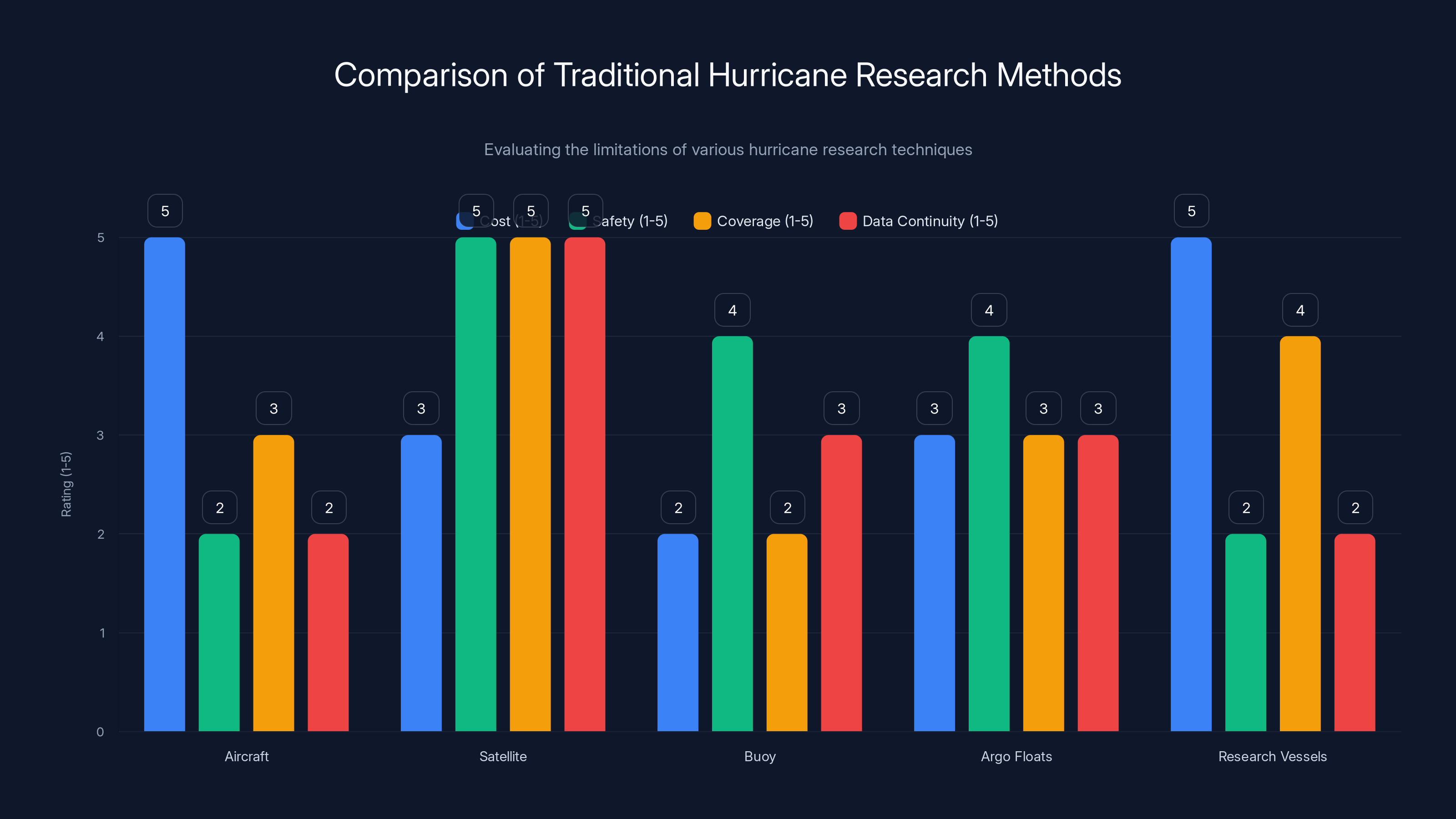

How This Compares to Traditional Hurricane Research Methods

To understand why Oshen's breakthrough matters, it's helpful to understand what hurricane research looked like before autonomous ocean robots.

Traditional hurricane research relies on several methods, each with significant limitations:

Aircraft-based observations. NOAA flies specially equipped P-3 Orion aircraft directly into hurricanes. These planes carry instruments that measure wind speed, pressure, temperature, and moisture as they penetrate the storm. This data is incredibly valuable, but it's expensive (aircraft operation costs tens of thousands per flight hour), dangerous (pilots are at real risk), and temporally limited (a flight provides a snapshot, not continuous observation).

Satellite observations. Weather satellites provide continuous monitoring of storm development, cloud structure, and large-scale patterns. They're the primary tool for hurricane tracking. But they measure atmospheric conditions, not ocean conditions. They can see what the hurricane is doing, but not what the ocean beneath it is doing.

Buoy networks. NOAA maintains a network of moored buoys across the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. These provide continuous data when they're in the right place. But buoys are fixed in location, vulnerable to damage from storms, and there aren't nearly enough of them to provide good spatial coverage. During a major hurricane, you might have one or two buoys nearby.

Argo floats. These are autonomous profiling floats that drift with ocean currents, periodically diving to collect temperature and salinity profiles. They provide valuable data, but they drift with the current rather than staying fixed, so maintaining consistent spatial coverage is difficult.

Research vessels. These can go anywhere and carry sophisticated instruments. But they're slow to deploy, expensive to operate, and you can't put a research vessel directly in the path of a Category 5 hurricane.

Oshen's approach combines the best features of these methods: autonomous operation like Argo floats, fixed positioning like buoys, rapid deployment like satellites, and continuous data collection that's possible because the robots don't need human safety considerations.

The comparison might look like this:

| Method | Spatial Coverage | Temporal Resolution | Safety Constraints | Cost | Deployment Speed | |--------|------------------|----------------------|--------------------||------|------------------| | Aircraft | Limited (flight path) | Snapshot | High risk | Very High | Slow | | Satellites | Global | Continuous | None | Very High | Already deployed | | Buoys | Fixed points | Continuous | Can be damaged | High | Slow | | Argo Floats | Sparse drifting | Intermittent | None | Moderate | Very Slow | | Research Vessels | Flexible | Continuous | Can't enter storms | Very High | Very Slow | | C-Star Swarms | Flexible | Continuous | None | Moderate | Fast |

This table shows why autonomous robot swarms are transformative. They offer continuous observation with no safety constraints, relatively low cost per unit, and fast deployment. The trade-off is that each individual robot is less sophisticated than a research vessel or buoy, but the swarm approach more than compensates through redundancy and coverage.

Traditional hurricane research methods vary significantly in cost, safety, coverage, and data continuity. Aircraft and research vessels are costly and less safe, while satellites offer high coverage and continuity but lack ocean data. Estimated data.

Implications for Climate Science and Hurricane Forecasting

Let's talk about what this actually means for our understanding of hurricanes and climate change.

Right now, hurricane forecast models have gotten quite good at predicting track—where a storm will go. The skill in predicting intensity—how strong a storm will become—is much weaker. A hurricane that the model predicted to reach Category 3 strength might intensify to Category 5 very suddenly, or a predicted Category 5 might weaken unexpectedly.

This forecast uncertainty is partly due to atmospheric limitations in our models. But it's also due to ocean limitations. We don't understand the detailed ocean-atmosphere coupling during storm development well enough. The ocean has enormous thermal energy, and how that energy gets transferred to the storm depends on detailed conditions that we don't observe well.

With continuous ocean observations during actual hurricanes, researchers can improve their understanding of this coupling. They can see exactly what ocean temperature structure leads to rapid intensification. They can measure how the storm's wind forcing changes the upper ocean structure in real-time. They can validate and improve the physics in their models.

Over time, this should lead to better intensity forecasts. That might sound like an abstract improvement, but it has concrete implications. Better intensity forecasts mean better preparedness. Communities can make more accurate decisions about evacuation timing, infrastructure preparation, and resource allocation.

For climate change research, the implications are even larger. We're concerned that warming oceans will lead to more intense hurricanes. But "more intense" covers a lot of possibilities. Do storms intensify faster? Do they maintain stronger intensity longer? Do they expand in size? Do they slow down, lingering longer over populated areas?

Answering these questions requires detailed observations of how hurricanes interact with the ocean in different thermal regimes. With autonomous robot swarms, researchers can deploy observational networks during future storms in ways that were previously impossible.

Oshen's Hurricane Humberto deployment was three robots. A future research program might deploy three hundred robots, creating a dense observation network that captures the full complexity of hurricane-ocean interaction across many spatial scales. This kind of observational density would be impossible with any previous technology—too expensive, too risky, too slow to deploy.

Defense and Intelligence Applications

Oshen's contracts with government and defense agencies suggest applications beyond weather forecasting.

Ocean monitoring has defense implications. Naval operations, submarine traffic, coastal security, and strategic intelligence all depend on understanding ocean conditions. Autonomous robots that can operate in extreme conditions and transmit data provide capabilities that were previously difficult or impossible.

The details of these applications are necessarily classified, so public discussion is limited. But the fact that defense organizations have signed multi-year contracts suggests the technology provides capabilities they've been seeking.

One obvious application is persistent surveillance. Traditional naval sensors have limited range and must be actively powered and monitored. Autonomous robot swarms could remain deployed for months, collecting continuous data on ocean conditions, acoustic signatures, and environmental conditions that correlate with military activities.

Another application is operation in denied or hostile environments. If you're trying to operate in waters where you can't openly deploy ships or aircraft, autonomous robots deployed from distance and operating for extended periods provide options that crewed systems don't.

The fact that Oshen is simultaneously serving civilian weather research and defense organizations suggests the technology is genuinely dual-use. The same systems that improve hurricane forecasting also enable military applications. This is common in ocean technology—there's rarely a hard boundary between civilian and defense oceanography.

Anahita Laverack's journey began with a failed competition in 2021, leading to the founding of Oshen in April 2022, and subsequent development of ocean technology.

The Manufacturing and Scaling Challenge Ahead

Oshen has proven the technology works. They have customer contracts. They have proof that the approach is superior to previous methods.

The next challenge is manufacturing at scale. Going from deploying dozens of robots per year to deploying hundreds or thousands per year requires fundamental changes to operations.

Labware and prototype manufacturing look fundamentally different from production manufacturing. In prototype mode, you're building custom robots, hand-assembling components, and optimizing each unit for performance. In production mode, you're optimizing for cost and repeatability. You want every robot to be nearly identical, built by semi-automated processes, with predictable assembly times and quality metrics.

This requires capital investment in manufacturing infrastructure, tooling for specific components, and process engineering to find the balance between automation and flexibility. You can't just build more prototypes faster. You have to fundamentally re-engineer how you build.

This is where the venture capital Laverack mentioned becomes important. Scaling manufacturing typically requires millions of dollars in capital equipment, inventory, and working capital. Bootstrapped operations can't typically fund this alone.

The timeline and execution here will determine whether Oshen becomes a significant company or a specialized supplier. They have the technology and customers. The question is whether they can scale production without losing quality or running into technical problems at manufacturing scale.

Historically, hardware companies that succeed at this transition tend to have strong operational leadership, realistic timelines, and willingness to iterate on manufacturing processes. Companies that overestimate their ability to scale quickly or underestimate manufacturing complexity often struggle.

What Could Go Wrong: Technical and Commercial Risks

Oshen has momentum, but hardware companies face specific risks that software companies don't experience.

Technical risks: The robots performed well during one hurricane. Hurricanes are variable. What happens if a future deployment encounters conditions slightly different from Humberto? What if saltwater corrosion proves more significant than observed? What if battery performance degrades faster in certain conditions? Hardware startups often discover reliability issues that only show up at scale or after extended operation.

Manufacturing risks: Scaling manufacturing always reveals problems. Components that worked fine at small scale might have quality issues at large scale. Suppliers might not meet specifications consistently. Labor and quality control become harder to maintain as volume increases.

Market risks: Government customers are valuable but also sticky and slow to grow. NOAA liked the robots, but will other agencies adopt them quickly? Will budgets remain allocated to ocean monitoring, or might government spending priorities shift? Commercial markets for ocean data exist but are less developed than government markets.

Competitive risks: Oshen is not the only company thinking about autonomous ocean robots. Competitors with more funding or existing manufacturing infrastructure could eventually enter this space. Right now Oshen has first-mover advantage and unique capabilities, but that advantage isn't permanent.

Regulatory risks: Deploying thousands of robots in international waters involves maritime law, environmental regulations, and international agreements. Right now this is relatively simple because Oshen deploys with government partners. But if the company wants to operate independently or expand to new geographies, regulatory complexity could increase significantly.

None of these risks are deal-killers. But they're real enough that execution matters as much as the underlying technology.

The Bigger Picture: Autonomous Systems and Climate Monitoring

Oshen isn't just building a company. They're part of a broader shift in how we monitor the environment.

Traditional environmental monitoring relied on sparse networks of fixed sensors, periodic surveys, and whatever governments could afford to maintain. This model worked okay for decades, but it has fundamental limitations. You can't observe everywhere all the time. You especially can't observe during extreme events because that's when fixed infrastructure breaks.

Autonomous robot swarms offer a different model: dense observation, self-healing resilience, and the ability to respond to events quickly. You deploy swarms into situations where you can't put humans or fragile equipment, and you accept that some units will be damaged while others continue operating.

This model is spreading beyond ocean monitoring. Autonomous systems are being deployed in atmosphere monitoring, wildfire tracking, volcanic monitoring, and glacier observation. The underlying logic is the same: if individual units are cheap and simple enough, you can deploy them in quantity and accept failures as part of the cost structure.

For climate science, this is transformative. Right now we're trying to understand a warming planet with observation networks designed for a stable climate. Those networks are sparse, expensive to maintain, and don't capture the important variations during extreme events. Autonomous robot swarms enable denser observation networks that can survive extreme events, which is exactly what climate science needs.

Oshen is one implementation of this broader trend, but it's early. Over the next decade, expect many more companies to emerge with autonomous systems for specific environmental monitoring niches. Some will succeed, some will fail. But the cumulative effect will be a fundamental shift in our observational capabilities.

Deployment Strategy: Why Swarms Are Better Than Individual Robots

One of Oshen's smartest decisions was embracing swarm deployment rather than trying to build one super-robot.

This is worth understanding because it reveals thinking about resilience that applies beyond ocean robotics.

Traditional engineering optimizes for individual unit reliability. If you're building a space probe or deep-sea lander, you want that one unit to work perfectly. You add redundancy—backup systems, over-built components, multiple pathways for critical functions. You test exhaustively. You accept that it costs millions of dollars but works reliably.

Swarm engineering optimizes for system-level reliability through redundancy, not individual unit reliability. Instead of spending

This shift in thinking has mathematical advantages. If you have one ultra-reliable unit with 99.9% reliability, one unit failing means you have no capability. If you have ten simple units with 85% reliability each, your expected system reliability is much higher, and even when units fail, you have partial capability.

For ocean monitoring, swarm deployment means you can:

-

Deploy faster. Building five robots takes less time than building one perfect robot. You can respond to hurricane forecasts with days of preparation instead of months.

-

Deploy cheaper. Five simple robots cost less than one advanced robot, even at the same unit cost. You can deploy more of them, creating better spatial coverage.

-

Accept failures. Some robots will break during hurricanes. That's fine. You've planned for it. Other robots keep operating.

-

Iterate rapidly. Instead of spending two years perfecting every component, you build good-enough robots, deploy them, learn from failures, and improve next time.

This approach requires a different mindset from traditional oceanography, where instruments are precious and failure is something to prevent at all costs. But it's increasingly the right approach for monitoring complex, variable systems like the ocean.

International Expansion and Partnerships

Oshen is based in the U. K. but has customers globally. This raises interesting questions about how the company might expand internationally.

Ocean robotics involves international maritime law, which is complex. Deploying in international waters has different regulations than deploying in Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) or territorial waters. International waters allow more freedom, but EEZs provide better data coverage for countries interested in their own coastal conditions.

Oshen's contracts with U. K. government and NOAA suggest two different market segments: domestic government customers and international partners. Expanding to more countries probably involves establishing regional partnerships or establishing local operations in major markets.

The U. K. government connection is notable. The U. K. is a major maritime nation with significant oceanographic research capabilities. Portsmouth and Plymouth have long histories as naval and oceanographic centers. Oshen's location in Plymouth positions it in the center of existing marine technology ecosystems, which makes recruitment, partnerships, and customer access easier.

Expansion to other countries might follow similar patterns: establish partnerships with national oceanographic agencies, navies, or research institutions in major markets, then grow the customer base from there.

There's also potential for partnerships with broader Earth observation companies. As satellite and drone companies expand their environmental monitoring offerings, ocean robots could complement their capabilities. A company like Planet Labs or Maxar might be interested in ocean data as part of broader environmental monitoring services. These partnerships could provide distribution channels and customer access that Oshen couldn't build alone.

The Economics of Ocean Monitoring Data

Understanding Oshen's long-term business model requires thinking about the economics of ocean data.

Ocean data has value, but the value isn't always direct and immediate. NOAA wants it for weather forecasting, which has clear societal value. Defense agencies want it for intelligence and operations. Research institutions want it for scientific understanding.

But pricing is challenging. How much should ocean data cost? Traditional oceanographic data from research institutions is often made publicly available for scientific research. This creates free competition for proprietary data services.

Oshen's approach seems to be positioning itself as a service provider to government and defense customers with specific needs rather than trying to sell raw data on open markets. This makes sense because government customers have budgets for specific capabilities, and ocean monitoring is a clear budget item. A government agency can say "we need real-time ocean data during hurricane season" and allocate resources for it. A commercial data buyer might struggle to justify the same investment.

Long-term, Oshen might diversify its customer base toward:

- Insurance companies: Better hurricane forecasts reduce insurance losses. Paying for better data is cost-effective.

- Port authorities: Safe harbor operations depend on accurate ocean and weather conditions.

- Shipping companies: Navigation safety and route optimization benefit from detailed ocean data.

- Oil and gas operators: Offshore operations face extreme weather risk. Better data improves safety and planning.

- Environmental agencies: Monitoring ocean health, pollution, and climate impacts increasingly requires detailed data.

Each of these markets represents potential customers who would pay for better ocean data. But developing these markets requires time, sales effort, and proof that the data actually improves their operations or reduces their costs.

Future Capability Expansion: What Comes After Hurricanes

Oshen proved robots can survive Category 5 hurricanes. What's next?

Logically, the company could extend capabilities in several directions:

Enhanced sensors: Current C-Star robots measure temperature, salinity, pressure, and currents. Future versions might include biological sensors (chlorophyll, zooplankton), chemical sensors (dissolved oxygen, nutrient levels), or acoustic sensors. Enhanced sensor packages mean the same robot platform collects more valuable data.

Longer endurance: Current robots operate for 100 days. Extending to 6 months or a year would require major improvements in power systems, but it's theoretically possible. Solar efficiency improvements, better battery chemistry, and more efficient electronics could extend operation dramatically.

Larger networks: Deploying dozens of robots simultaneously is impressive. Deploying hundreds simultaneously is the next logical step. This requires manufacturing scale and customer demand for that data density.

Different environments: Oshen proved the concept in open ocean hurricanes. Similar robots could be deployed in coastal estuaries, inland rivers, lakes, and Arctic waters. Each environment has different requirements but many shared technologies.

Docking and servicing infrastructure: Right now robots operate autonomously then get recovered. Future systems might include docking stations where robots autonomously recharge and transmit data, extending endurance indefinitely. This requires solving additional technical problems but opens new operational models.

Swarm coordination: Current robots operate independently. Future robots might coordinate with each other, sharing data and optimizing positions collectively. This requires more sophisticated onboard computing and communication, but it enables smarter deployments.

These expansions aren't necessary for Oshen to be successful. The core business—deploying robots for government customers—is viable as-is. But they represent opportunities for long-term growth and capability expansion.

Lessons for Other Hardware Startups

Oshen's journey offers several lessons relevant beyond just ocean robotics.

First: Start with a real problem, not a technology looking for a problem. Laverack started when she realized ocean data was missing and people would pay to collect it. She didn't start with "let me build ocean robots" and then look for applications. The problem came first.

Second: Bootstrap if you can, at least long enough to prove the product works. Laverack and Dowds kept costs low and focused on building something customers wanted rather than raising capital to build something investors thought was cool. Venture capital came after they'd proven success, not before.

Third: Test in real conditions, relentlessly. Two years of testing in actual ocean conditions, including winter storms, built robustness that laboratory testing alone would never achieve. Real-world testing teaches you things you can't predict.

Fourth: Optimize for system-level performance, not individual unit performance. Swarms and redundancy are mathematically superior to optimization of individual components. Accept that some units will fail and design your system around that reality.

Fifth: Government and institutional customers are good early markets for environmental technology. They have explicit needs, budgets, and willingness to commit to multi-year contracts. This provides stable revenue while you figure out broader markets.

Sixth: Hardware manufacturing at scale is genuinely different from prototyping. Raise capital specifically for manufacturing infrastructure, and plan for longer timelines than you think you need. This phase is where many hardware startups stumble.

FAQ

What is Oshen and what does it do?

Oshen is a technology company that builds autonomous ocean robots called C-Star units designed to collect oceanographic data in extreme conditions, including during hurricanes. The robots operate independently for up to 100 days, collecting data on ocean temperature, salinity, pressure, and current velocity. Oshen deploys these robots in swarms to government and defense agencies for weather forecasting, climate research, and maritime operations.

How do C-Star robots survive hurricanes?

C-Star robots survive hurricanes through a combination of robust hull design, redundant systems, efficient power management, and swarm deployment strategy. Individual robots are built to handle extreme pressure and saltwater corrosion, but the key survival factor is redundancy. By deploying multiple robots (typically five), Oshen accepts that some might be damaged while others continue operating and transmitting data. The system is designed for graceful degradation rather than perfect reliability of individual units.

Why is ocean data during hurricanes important?

Ocean data during hurricanes fills a critical gap in hurricane research and forecasting. Currently, meteorologists can observe storm structure and intensity from aircraft and satellites, but they lack direct observations of ocean conditions beneath the storm. Understanding how the ocean interacts with hurricane forcing is essential for improving intensity forecasts, validating climate models, and understanding how warming oceans will affect future hurricane behavior. Oshen's robots provide the first continuous observations of these critical ocean-storm interactions.

How long can C-Star robots operate independently?

C-Star robots are designed to operate continuously for approximately 100 days without human intervention or maintenance. They manage power through a combination of solar panels for charging during favorable conditions and onboard batteries for energy storage during storms or low-light periods. The extended endurance allows for monitoring of seasonal weather patterns and hurricane events that span weeks or months.

What do the robots actually measure?

Oshen's C-Star robots carry sensor arrays that measure multiple oceanographic variables including sea surface temperature, salinity levels, water pressure at various depths, and current velocity and direction. Advanced deployments might include additional sensors for dissolved oxygen, nutrient levels, or biological indicators depending on customer requirements. All data is stored onboard and transmitted to shore via satellite or cellular networks when communication windows are available.

Who uses Oshen's robots and why?

Oshen's primary customers are government agencies and defense organizations including NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), the U. K. government, and various defense agencies. NOAA uses the robots for weather forecasting and hurricane research. Defense organizations use them for maritime intelligence and operational awareness. Each customer has specific requirements for data type, deployment location, and frequency, which Oshen tailors through customized deployments.

What made the Hurricane Humberto deployment significant?

The Hurricane Humberto deployment was significant because it proved that autonomous ocean robots could collect data continuously throughout a Category 5 hurricane—something that had never been demonstrated before. Three of five deployed robots not only survived the entire storm but continued collecting and transmitting data, providing the first real-time observations of ocean conditions during the most extreme weather on Earth. This proof of concept validated the technology and demonstrated capabilities that traditional oceanographic instruments cannot match.

Why did Oshen choose a swarm deployment strategy instead of building one advanced robot?

Swarm deployment is more effective than individual advanced robots because it provides system-level resilience through redundancy rather than perfecting individual units. Five robots with 85% individual reliability provide better overall performance than one ultra-reliable robot, especially in extreme conditions where failure is difficult to prevent. Swarm deployment also enables faster manufacturing, lower unit costs, better spatial coverage, and the ability to accept and learn from failures without catastrophic system failure.

What are the future plans for Oshen?

Oshen plans to raise venture capital to scale manufacturing and increase deployment capacity. The company will expand its customer base beyond initial government partners, potentially serving insurance companies, shipping firms, port authorities, and commercial operators who benefit from detailed ocean data. Future capability expansions might include enhanced sensor packages, longer endurance, larger deployment networks, and expansion to different ocean environments beyond open ocean hurricane tracking.

How is this technology different from traditional oceanographic buoys?

Oshen's robots differ from traditional buoys in several critical ways. Traditional buoys are expensive ($100K-150K each), fragile in extreme conditions, and deployed sparingly due to cost and recovery challenges. C-Star robots are cheaper per unit, designed to survive extreme conditions, and deployed in quantity as expendable components of a larger system. Traditional buoys require maintenance and recovery, while C-Star robots operate autonomously and are expected to be partially recovered or lost as part of normal operations.

Conclusion: The Future of Ocean Observation

Oshen's achievement with Hurricane Humberto represents more than just a successful product deployment. It represents a fundamental shift in how we observe complex environmental systems.

For decades, ocean monitoring has been constrained by the same limitation: observation during extreme events was nearly impossible. We could study hurricanes in their lead-up phase. We could study them from aircraft. We could study them after they passed. But we couldn't study them in real-time while they were happening, from the ocean's perspective.

Autonomous robot swarms remove that constraint. They enable the kind of continuous, real-time observation that climate science needs. They provide data density that was previously impossible. They do this at costs that are reasonable enough to deploy in quantity.

Laverack's insight—that the missing piece wasn't better predictions but better data—turned out to be correct. By focusing on solving the data collection problem rather than the prediction problem, Oshen created technology that makes everyone else's job easier. Meteorologists can build better forecast models with better data. Climate scientists can validate their understanding of extreme weather. Defense organizations gain new operational capabilities.

This pattern repeats across environmental monitoring. Wildfire research is limited by sparse observations during fires. Glacier research is limited by difficulty accessing ice sheets. Atmospheric chemistry research is limited by sparse measurement networks. In each case, autonomous systems that can operate in extreme conditions would be transformative.

Oshen is the early example, but it won't be the only one. Over the next decade, expect to see autonomous systems deployed across environmental monitoring. Some will be built by companies like Oshen, others by traditional instrument manufacturers adapting to new models, others by entirely new entrants seeing opportunities in specific niches.

The broader implication is that our understanding of climate, extreme weather, and environmental change is about to get much better. Not because we suddenly had a new theory or discovered something surprising, but because we finally built the measurement capability we should have had all along.

For Oshen specifically, the path forward is clear: prove the technology works with government customers, scale manufacturing to handle demand, expand to additional markets, and eventually become a fundamental piece of global ocean and environmental monitoring infrastructure.

Laverack started by trying to win a robot sailing race. She failed. But that failure led to something more important than winning a race—it led to technology that enables us to understand our ocean in ways we couldn't before. That's the kind of failure that usually turns out to matter most.

Key Takeaways

- Oshen's C-Star robots became the first autonomous systems to collect continuous oceanographic data through a Category 5 hurricane, filling a critical gap in hurricane research

- Swarm deployment strategy using cheap, redundant robots proved superior to traditional expensive, fragile oceanographic buoys for extreme condition monitoring

- Government agencies like NOAA signed contracts after observing successful hurricane data collection, validating the technology's value for weather forecasting

- The company bootstrapped for two years on a sailboat before raising capital, proving product-market fit with customers before scaling manufacturing

- Ocean observations during hurricanes will improve hurricane intensity forecasts and validate climate models—capabilities that were previously impossible with traditional oceanographic methods

Related Articles

- CES 2026 Picks Awards: Complete Winners List [2025]

- Brunswick Boats at CES 2026: AI, Self-Docking & Solar [2026]

- Home Robots in 2026: Why Specialized Bots Beat the Robot Butler Dream [2026]

- Nvidia Cosmos Reason 2: Physical AI Reasoning Models [2025]

- How to Watch Hyundai's CES 2026 Press Conference Live [2026]

- Kodiak and Bosch Partner to Scale Autonomous Truck Technology [2025]

![Ocean Robots in Category 5 Hurricanes: Oshen's Breakthrough [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ocean-robots-in-category-5-hurricanes-oshen-s-breakthrough-2/image-1-1768667808997.jpg)