The Circular Deal That Changes Everything

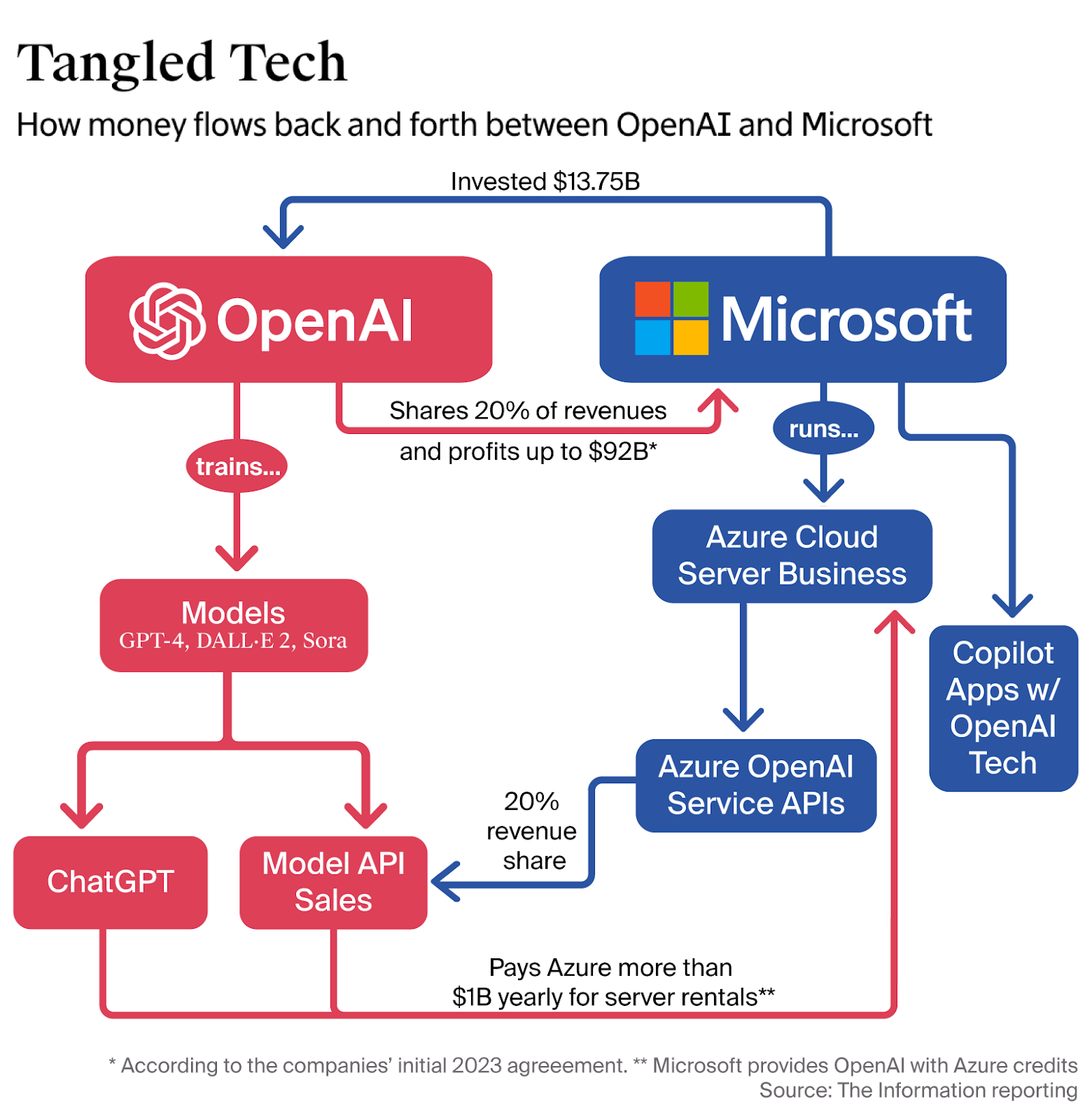

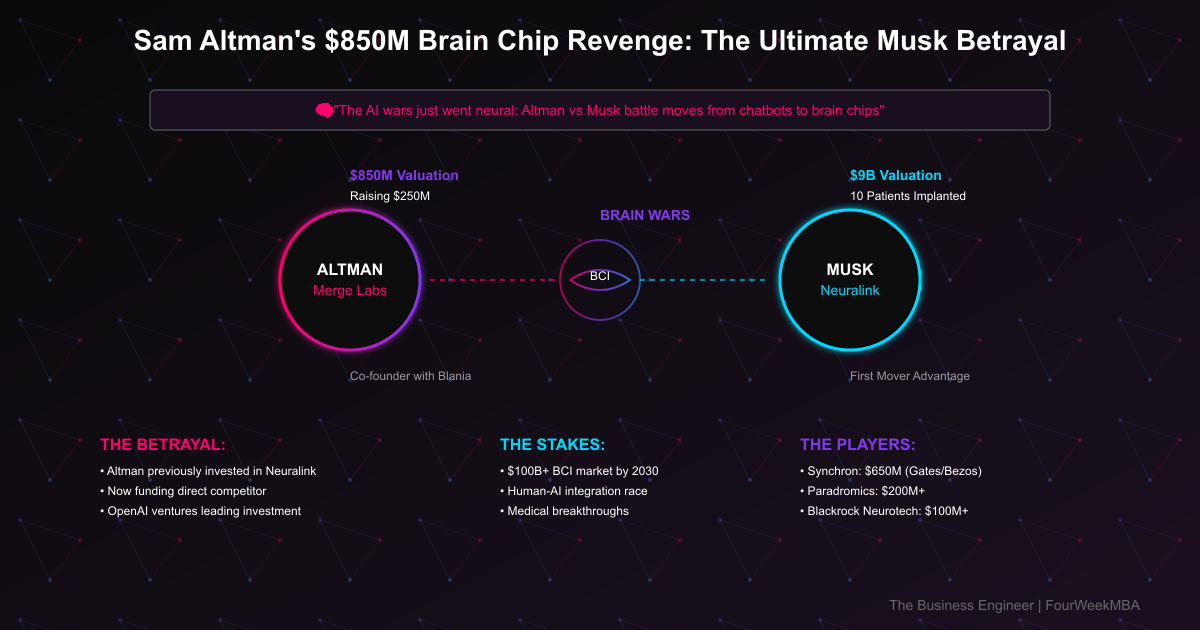

Last Thursday, the tech industry got a reminder that the lines between investment, leadership, and innovation have blurred beyond recognition. OpenAI announced it's investing in Merge Labs, Sam Altman's brain-computer interface startup. The headline seems straightforward enough: a

This isn't just another venture round. It's a strategic play that reveals how the most powerful AI companies think about the future of human-machine interaction. It's also a perfect example of how founders with multiple bets can create value across a portfolio of companies, sometimes in ways that benefit each other in circular loops.

Merge Labs came out of stealth with a mission that sounds ripped from science fiction: bridging biological and artificial intelligence to maximize human ability. The startup defines itself as a research lab dedicated to combining neuroscience, advanced AI, and bioengineering to create entirely new ways for humans to interface with technology. And unlike its more famous competitor, Neuralink, Merge Labs is pursuing a fundamentally different technological approach.

The question everyone's asking is why OpenAI cares so much. The answer reveals something important about where the AI industry thinks the next frontier lies. It's not in bigger models or faster inference. It's in the interface between human brains and artificial intelligence systems.

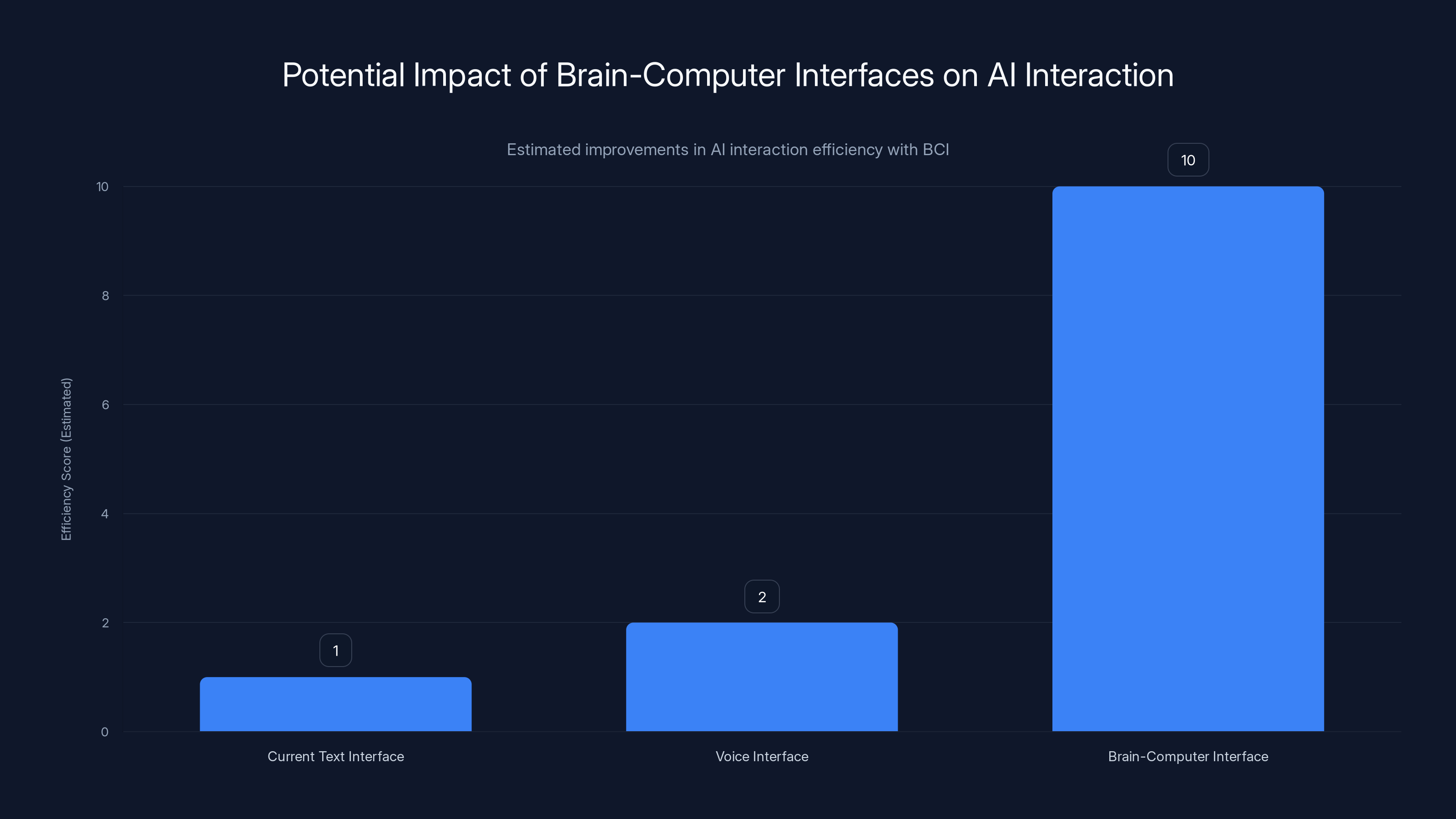

Real talk: this investment matters because it signals that the companies leading AI development believe the constraint isn't computational power anymore. The constraint is bandwidth. Right now, humans interact with AI through text, voice, and images. We're bottlenecked by the speed and capacity of these interfaces. A brain-computer interface would be exponentially faster, richer, and more natural.

But there's more going on here than just technological enthusiasm. There's the Altman factor, the competitive angle with Elon Musk's Neuralink, and the question of whether this is the future of human-AI collaboration or an elaborate financial mechanism that benefits a select few insiders.

Understanding Merge Labs: The Non-Invasive Approach

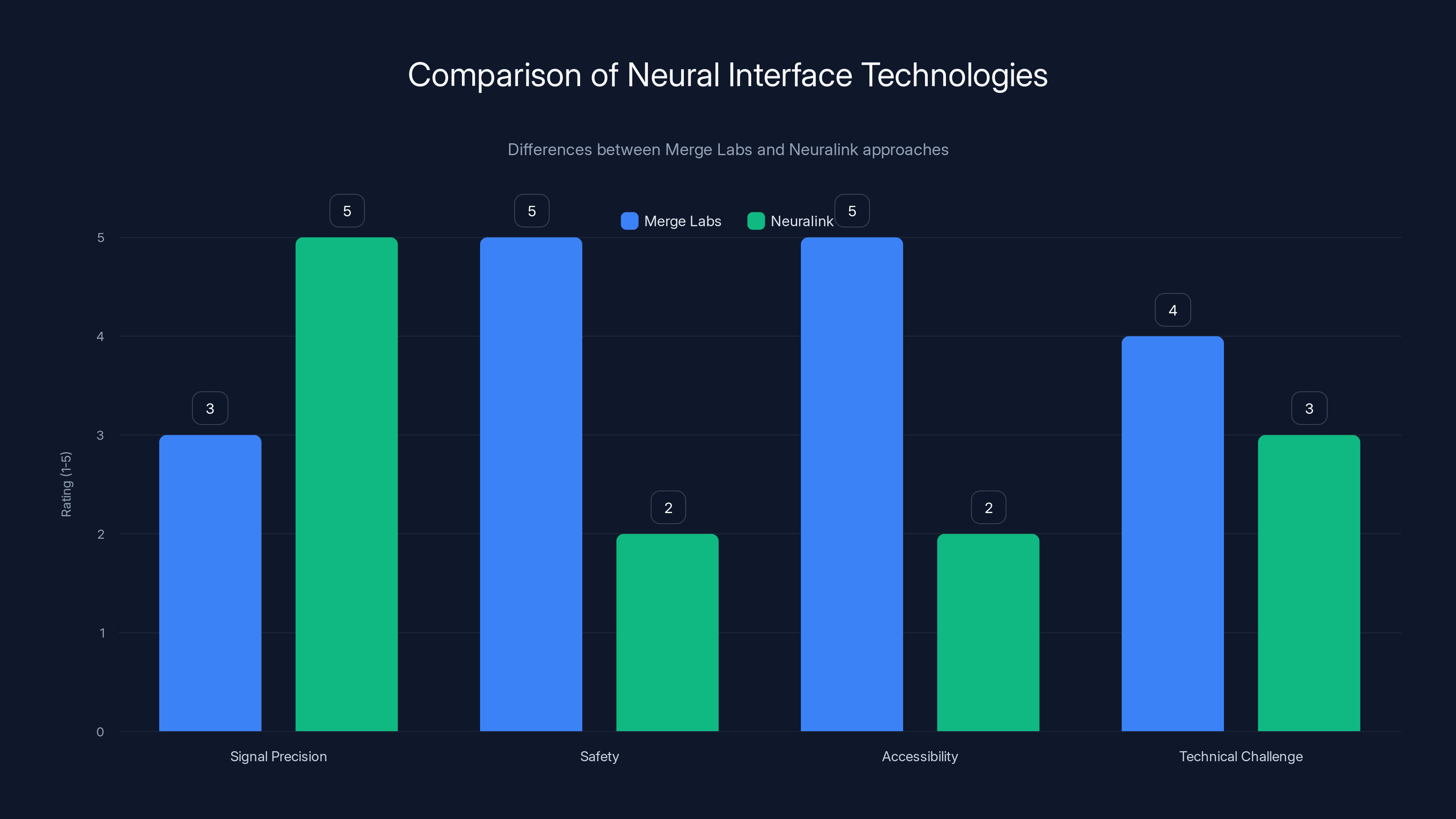

Let's be clear about what makes Merge Labs different from the existing landscape of brain-computer interface startups. Neuralink, which everyone knows about, requires invasive surgery. A surgical robot removes a small portion of your skull and inserts electrode threads into your brain tissue to read neural signals. It works, and it's impressive, but it carries real medical risks and limitations.

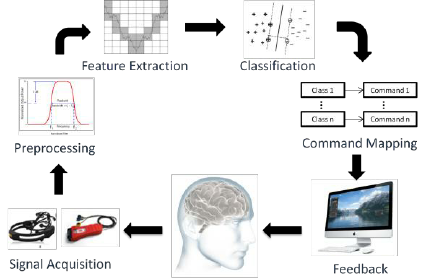

Merge Labs is pursuing something theoretically less risky but far more technically ambitious: non-invasive neural interfacing using molecules instead of electrodes. This is where it gets weird, but in a good way.

The technical approach is based on using ultrasound and other deep-reaching modalities to transit and receive information from neurons without physically penetrating the brain. Instead of electron-thin wires, you're using molecular-level technology that can transmit and receive signals from the brain through the skull. Think of it as wireless communication with your neurons.

This distinction matters more than the headlines suggest. Non-invasive means you don't need brain surgery. You don't need to recover from a major surgical procedure. You don't face the same infection risks or rejection concerns. In theory, you could use a device, take it off, and use it again weeks later without medical complications.

The challenge, and it's substantial, is that non-invasive approaches have historically been far less precise than invasive ones. You can read aggregate brain activity through electroencephalography (EEG), but you can't isolate individual neurons or get the same signal clarity that electrode arrays provide. Merge Labs claims they've developed entirely new technologies to overcome this limitation.

The co-founder team gives you a sense of their technical depth. Alex Blania and Sandro Herbig come from Tools for Humanity, which manages the World orbs that scan people's eyes for biometric identification. Tyson Aflalo and Sumner Norman are from Forest Neurotech, which specializes in implantable neural technology. Mikhail Shapiro is a researcher at Caltech working on molecular-scale bioengineering. This isn't a group of entrepreneurs guessing about neuroscience. They've actually worked on related problems.

The company's statement about their mission is worth reading carefully: "If we can interface with these neurons at scale, we could restore lost abilities, support healthier brain states, deepen our connection with each other, and expand what we can imagine and create alongside advanced AI." That last part is key. They're not just talking about medical applications. They're talking about enhancement.

Restore lost abilities refers to treating paralysis, spinal cord injuries, and neurological conditions. Support healthier brain states could mean addressing depression, anxiety, or cognitive decline. But expand what we can imagine and create alongside advanced AI? That's the Silicon Valley fantasy: using BCIs to give normal, healthy people superhuman capabilities by directly connecting their brains to AI systems.

That's also the contentious part. Medical applications are one thing. Enhancement is something else entirely, with ethical implications that the industry is still figuring out.

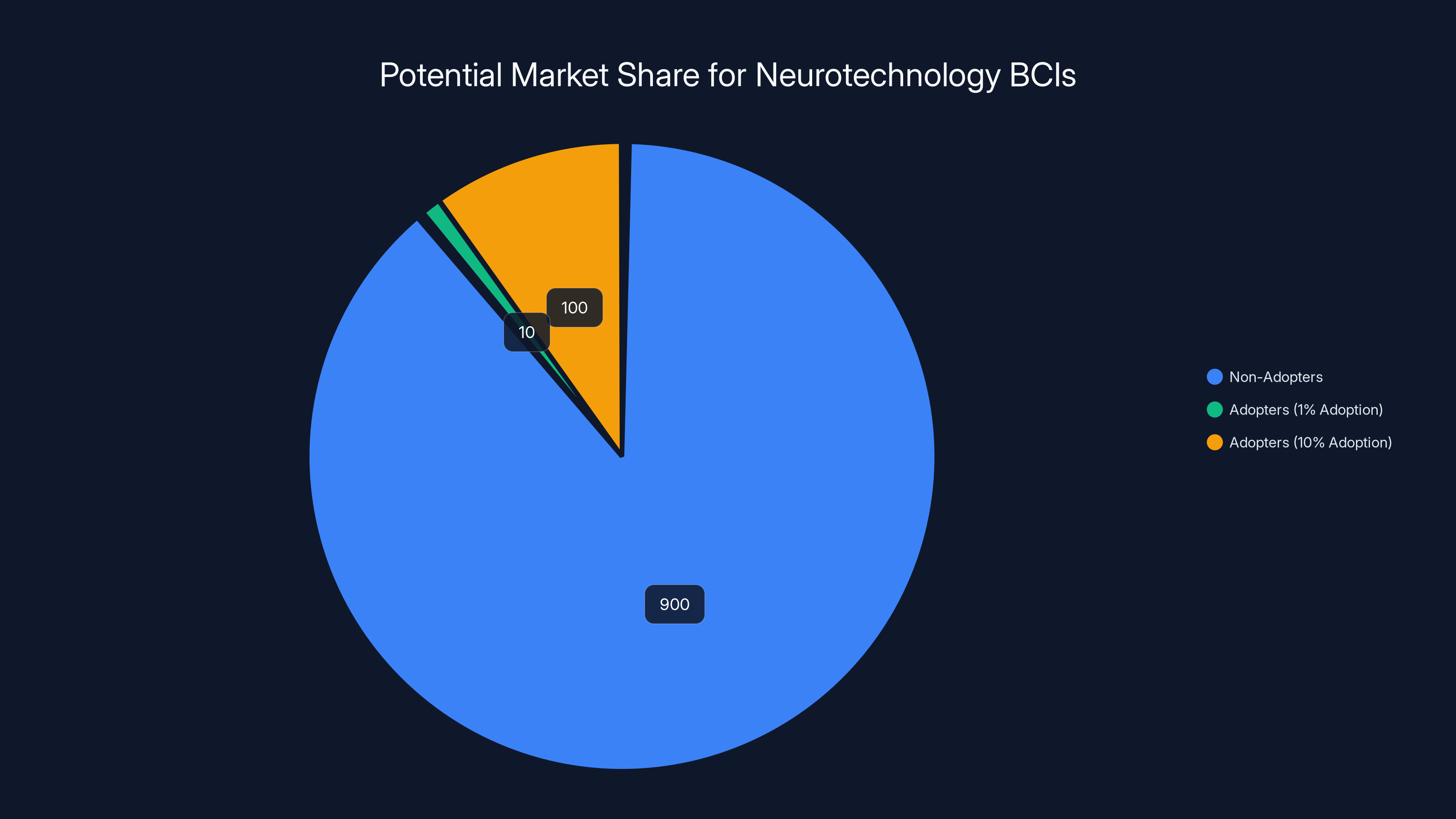

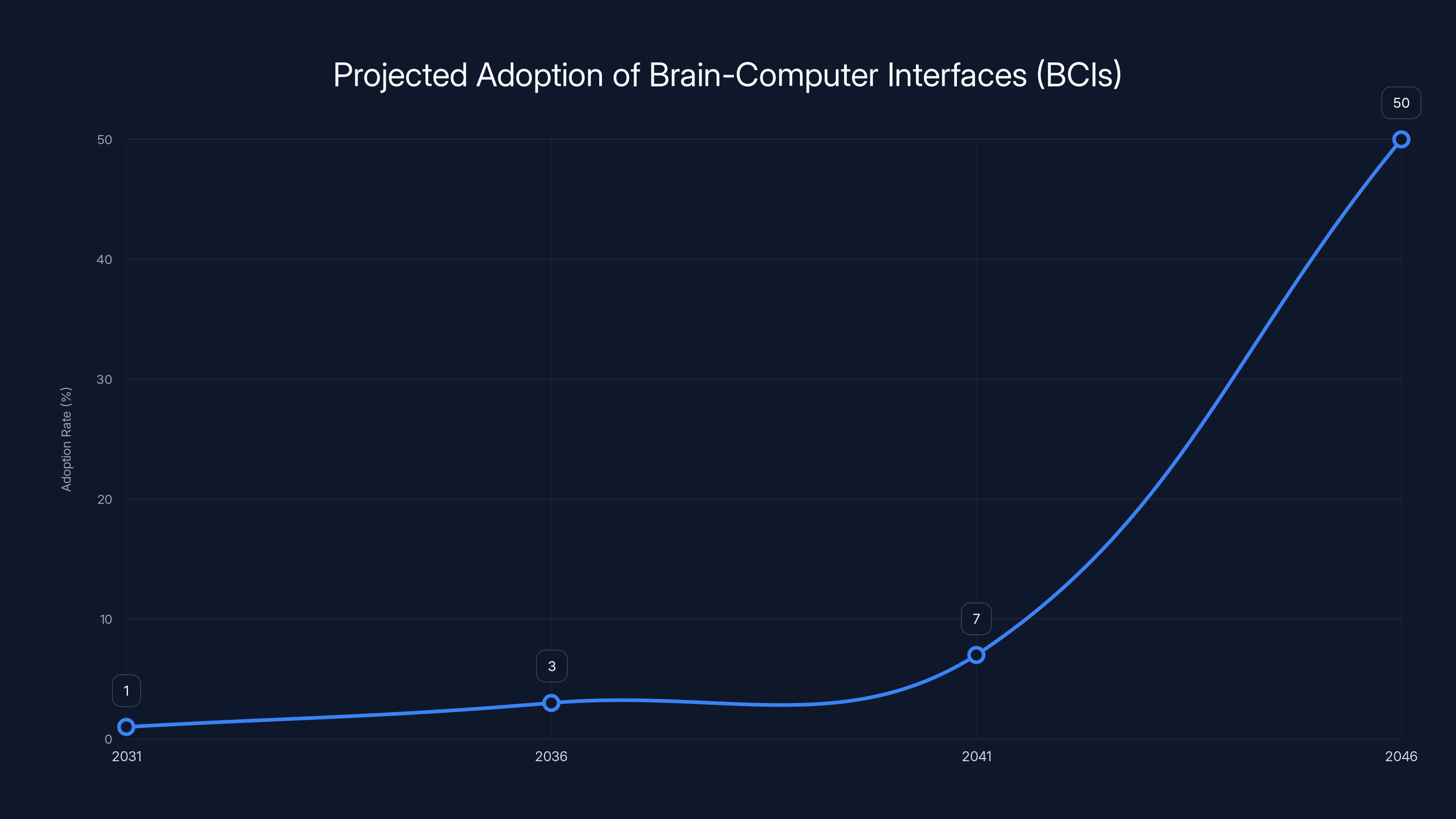

Estimated data shows that even a 10% adoption rate of BCIs could result in 100 million users, highlighting the significant market potential for neurotechnology.

Why Open AI Is Suddenly Interested in Neuroscience

OpenAI's reasoning for the investment is public, and it's revealing. The company wrote in a blog post that brain-computer interfaces "are an important new frontier" that will create "a natural, human-centered way for anyone to seamlessly interact with AI."

Let's unpack that. An AI system is only as useful as the interface allows. Today, you type a prompt into Chat GPT, wait a few seconds, and get a response back. That's the constraint. Even with voice interfaces, you're still limited by how fast you can speak and how much information you can convey in natural language.

A brain-computer interface changes that dynamic completely. You don't need to translate your thoughts into language. You don't need to wait for your brain to process text. The bandwidth between your mind and the AI system increases by orders of magnitude.

From OpenAI's perspective, this means their AI systems become exponentially more useful. Instead of text in, text out, you have continuous, bidirectional communication with far richer information transfer. You could be working with an AI assistant that understands your intent at a neurological level, not just a linguistic level.

OpenAI also mentioned that they'll work with Merge Labs on "scientific foundation models and other frontier tools." In other words, OpenAI isn't just investing money. They're committing engineering resources. OpenAI researchers will help build the AI systems that interpret neural signals. This is a partnership with significant technical collaboration.

But here's the circular part that everyone notices: if Merge Labs succeeds in creating a practical BCI, that BCI probably needs to run an operating system. That OS needs to interpret intent, adapt to individuals, and operate reliably with limited and noisy signals. Who's best positioned to build that? OpenAI. They have the AI expertise, the frontier models, and the resources to create an OS that can understand context and intent with remarkable precision.

So the investment makes OpenAI the default choice to power Merge Labs' interface layer. Success for Merge Labs drives adoption of OpenAI's software. Success for OpenAI's software increases the value of Merge Labs' hardware. It's symbiotic.

There's also the hardware angle. OpenAI is working with Jony Ive's startup io, which they acquired last year, to produce AI hardware that doesn't rely on a screen. The leaks suggest this might be an earbud. An earbud-based AI device that could integrate with a Merge Labs BCI? Now you're talking about a complete human-AI interaction ecosystem that OpenAI controls at multiple layers.

The Altman Factor: Multiple Bets, Convergent Interests

Sam Altman sits at the center of this web in a way that's increasingly hard to ignore. He's CEO of OpenAI. He founded or chairs multiple other companies. He has personal investments across AI, nuclear energy, and biological engineering. And now he's the co-founder of Merge Labs, which just received OpenAI's largest investment check.

This isn't necessarily corrupt. You can make a legitimate argument that having someone who understands both AI and neuroscience leading efforts in both domains is actually efficient. Altman has a coherent vision about the future of human-AI integration. He's been talking about "the Merge" since at least 2017, when he published a blog post speculating that humans and machines would eventually combine, possibly by "plugging electrons into our brains."

But it's also worth acknowledging the potential conflicts. When Altman makes a decision at OpenAI, he's potentially influencing his own wealth and the value of his other companies. When he recruits co-founders from Tools for Humanity to lead Merge Labs, he's pulling talent from another company he chairs. When he accepts OpenAI's investment, he's making his biggest competitor in AI his largest investor in BCIs.

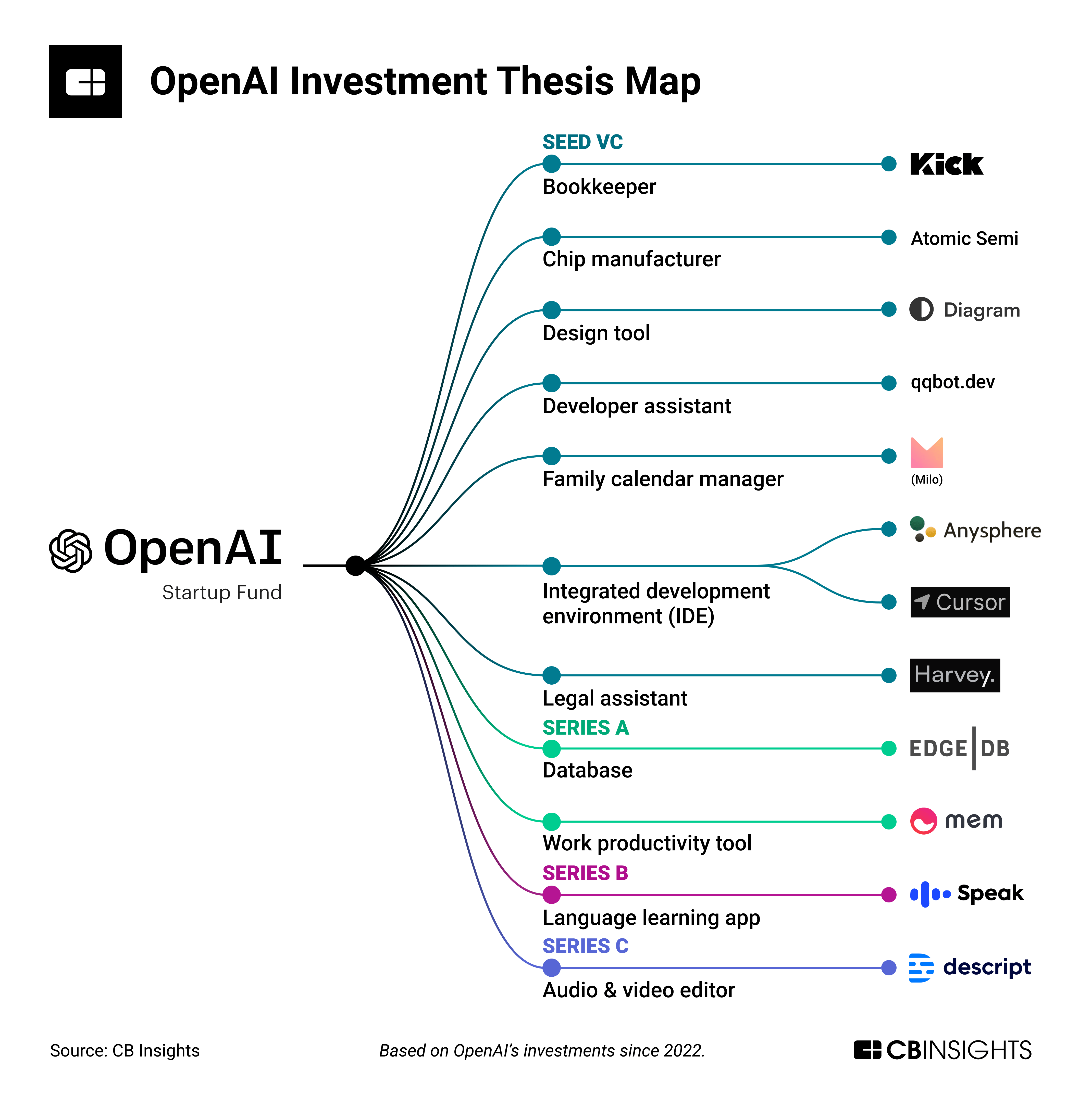

The previous reports mentioned that OpenAI primarily invests through the OpenAI Startup Fund, which has backed several other startups either founded or chaired by Altman. Red Queen Bio, Rain AI, and Harvey have all received OpenAI funding. So has Helion Energy, a nuclear fusion company Altman chairs. So has Oklo, a nuclear fission company. This pattern suggests a systematic approach where Altman identifies promising companies, occasionally takes a leadership role, and then channels OpenAI investment toward them.

You could call this ecosystem thinking. You could also call it circular deal-making. Probably it's both.

The key question is whether these investments are being made because they're genuinely strategic for OpenAI or because they benefit Altman's portfolio. And honestly, those things aren't mutually exclusive. An investment can be both genuinely strategic and personally beneficial. That's not unusual in venture capital. But the scale and pattern here are worth noticing.

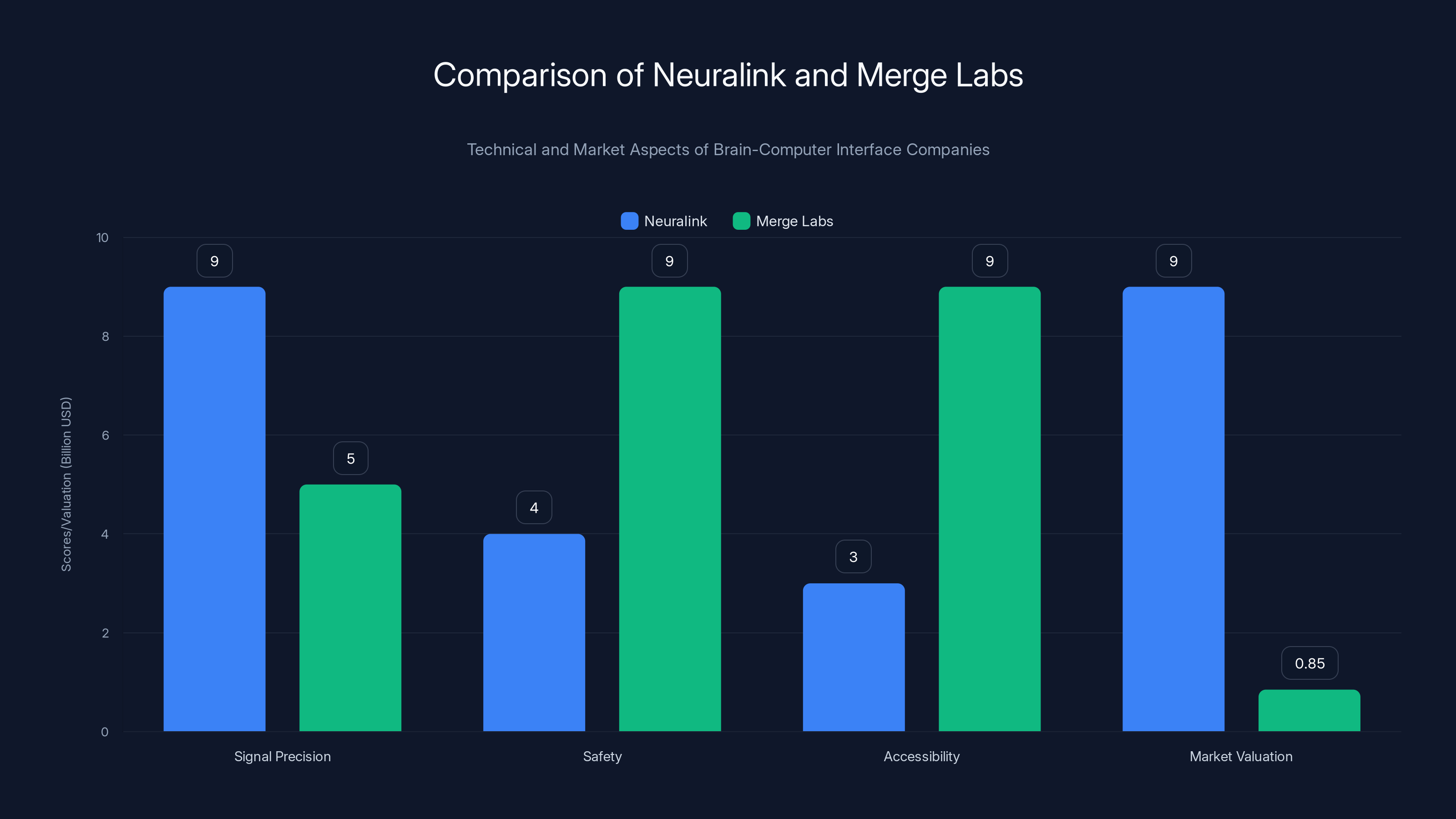

Neuralink offers higher signal precision due to its invasive approach, while Merge Labs prioritizes safety and accessibility with its non-invasive technology. Estimated data.

Merge Labs vs. Neuralink: The Technical Battle

The obvious comparison is Neuralink, Elon Musk's brain-computer interface startup. Both companies are working on roughly the same problem: reading neural signals and using them to control external systems. But they're pursuing radically different approaches.

Neuralink's strategy is invasive. You get surgery. Electrode threads go into your brain. You can read signals with remarkable precision because the electrodes are literally inside the tissue where the neurons are firing. The downside: you need brain surgery, recovery time, and you face risks of infection or rejection. The upside: the signal quality is exceptional.

Merge Labs' strategy is non-invasive. No surgery needed. You use molecular technology through the skull. The upside: accessibility and safety. Anyone could use this technology with minimal medical risk. The downside: signal quality and precision are historically much lower with non-invasive approaches.

These are opposite tradeoffs. Neuralink chose precision over accessibility. Merge Labs is betting that they can achieve adequate precision without invasive surgery, which would be a massive advantage if they pull it off.

From a market perspective, this matters enormously. Neuralink's first patient used the device to play video games and control a computer cursor with his thoughts. That's impressive. But it required brain surgery. How many people want to undergo brain surgery to play video games better? Probably not many.

Merge Labs doesn't need to get past that barrier. Their technology could be available to anyone, with no medical intervention required. That's a market advantage of potentially massive proportions.

Neuralink last raised a Series E at a

The investment landscape is interesting too. Neuralink has been entirely self-funded by Musk's companies and private investors. Merge Labs has OpenAI, which brings not just money but AI expertise and a commitment to building the software layer that makes the hardware useful.

Musk famously gets frustrated with how slowly things move in the AI and neuroscience space. He wanted faster progress on Neuralink and got frustrated with regulatory timelines. Merge Labs, with OpenAI backing, might move faster simply because they have both the funding and the strategic partners needed to accelerate.

There's also a competitive angle that shouldn't be ignored. Musk and Altman have a history, and it's not warm. They co-founded OpenAI together, but Musk eventually left the board amid disagreements about strategy and governance. Now Musk is building Neuralink while Altman is building Merge Labs, with backing from OpenAI. It's not quite a direct competition, but it's definitely a rivalry.

The Medical Use Case: Restoring Function

Let's start with the uncontroversial part: using BCIs for medical applications. For people with severe paralysis, spinal cord injuries, or degenerative neurological diseases, BCIs represent genuine hope. If you can't move your body, but your brain is intact, a device that reads your neural signals and translates them into movement or communication is life-changing.

Neuralink's first patient, a man named Noland Arbaugh who has quadriplegia from a 2016 diving accident, demonstrated the real potential. After receiving the Neuralink implant, he could control a computer cursor with his thoughts. He could play video games. He could send emails without a mouse or keyboard. These are abilities he'd lost. A BCI gave them back.

Merge Labs is positioning itself as having a similar goal but with a broader addressable market. Medical BCIs require FDA approval, clinical evidence, and a path to human trials. That's years of work. But if you can build non-invasive technology that works, you can potentially help more people.

The medical justification is strong. Stroke patients might regain motor control. People with Parkinson's disease might reduce tremors. People with locked-in syndrome might communicate again. These are real medical benefits that affect millions of people globally.

OpenAI's investment makes sense from this angle too. BCIs are going to be critical medical devices. Companies that develop them will become deeply involved in healthcare. OpenAI, as the primary software provider, would be positioned at the center of that ecosystem.

But here's where it gets complicated: the medical use case doesn't actually require a

The fact that Merge Labs is raising this much money suggests they're thinking beyond medical applications.

The Enhancement Fantasy: Where Things Get Weird

The real reason for the massive funding and valuation is the enhancement angle. Not fixing what's broken, but augmenting what's normal. Using a BCI to make a healthy person smarter, faster, more creative, or more capable.

Merge Labs' founding statement talks about "expanding what we can imagine and create alongside advanced AI." That's not medical language. That's enhancement language.

The vision is straightforward: your brain and an AI system become a unified intelligence. You're not typing prompts and reading responses. You're thinking at the AI, and the AI is thinking back at you, with the exchange happening at the neurological level where thought actually occurs.

What would this enable? Theoretically, everything. A researcher could explore a dataset in their mind at the speed of neural processing instead of at the speed of UI clicks. A writer could collaborate with an AI that understands their intent before they articulate it. A programmer could debug code by understanding the logical flow intuitively rather than by reading text on a screen.

This is why OpenAI cares. This is why the valuation is high. This is why the investment is strategic rather than just financial.

But this is also where ethical concerns emerge. Enhancement technology is always unequally distributed initially. The first BCIs will be expensive. They'll go to wealthy people, to researchers, to people with connections. That creates a technology gap that compounds over time. The people with BCI enhancement are more productive, more creative, more capable. They make more money. They invest in better BCIs. The gap widens.

This is the concern that critics raise about any enhancement technology. It's not necessarily wrong to pursue it, but you have to acknowledge the inequality implications.

Altman himself seems aware of this. In his 2017 blog post about the Merge, he framed it as humanity's best chance of surviving against superintelligent AI. The argument goes: if AI becomes superintelligent and humans remain unchanged, humanity might become irrelevant. But if humans and machines merge, we maintain control and participation in whatever comes next.

It's a compelling argument if you believe superintelligent AI is inevitable. It's less compelling if you think we should focus on building AI that remains aligned with human values without requiring us to restructure our brains.

Neuralink excels in signal precision due to its invasive approach, while Merge Labs offers superior safety and accessibility. Neuralink's market valuation is significantly higher, reflecting its advanced stage and proof of concept. (Estimated data)

The Neuroscience Challenge: Harder Than It Looks

The technical challenge Merge Labs faces is genuinely difficult, worth understanding if you want to assess whether they can actually pull this off.

Your brain operates through electrochemical signals. Neurons communicate by sending electric signals (action potentials) and receiving chemical signals (neurotransmitters). A BCI needs to read these signals and translate them into actionable information. The precision required varies by application.

If you want to read coarse-level activity, like "the user is thinking about moving their right arm," you can get away with lower precision. Invasive electrodes reading from a small region can do this. Non-invasive methods like EEG (electroencephalography) can sometimes do this too, though with more difficulty.

If you want to read fine-grained activity, like "which specific neurons are firing and in what sequence," you need higher precision. This is much harder non-invasively. The signal has to travel through cerebrospinal fluid, meninges, the skull, scalp, and skin. Each layer attenuates and distorts the signal. By the time it reaches the surface, a lot of information is lost.

Merge Labs claims they can overcome this by using molecules instead of electrodes and ultrasound as a transmission mechanism. The idea is that ultrasound can penetrate the skull better than electrical signals, and molecular markers can provide additional information density.

This is theoretically plausible. Ultrasound is already used medically to penetrate the skull for therapeutic purposes. Molecular markers are used in biological imaging. Combining these approaches for a BCI is novel but not absurd.

The challenge is getting it to work reliably at scale with high enough signal quality to be useful. There are papers in the neuroscience literature suggesting non-invasive approaches can achieve meaningful signal clarity, but these are early-stage findings. Real-world implementation at the quality level needed for practical BCIs is unproven.

This is why Merge Labs is probably going to take years before you see any public demonstrations. They need to:

- Develop the molecular markers and ultrasound technology to prototype level

- Test it in preclinical models to prove signal quality

- Design clinical trials with appropriate safety monitoring

- Run those trials and get results

- File for FDA approval

- Iterate based on feedback

Each step takes time. Even with $250 million in funding, you're probably looking at 5-7 years before you see a functional non-invasive BCI tested in humans.

Neuralink moved faster because they used existing electrode technology. They didn't have to prove a new technology worked. They just had to prove that existing technology could be implanted safely and used effectively. That's still hard, but it's a more established path.

Merge Labs is doing something more ambitious and more uncertain. That's fine, but it's worth acknowledging the technical risk.

The AI Operating System Layer: Open AI's Real Edge

Here's where OpenAI's involvement becomes crucial. A BCI without good software is just a device that reads brain signals and does nothing with them. The software layer that interprets those signals, understands intent, and responds appropriately is what actually makes the technology useful.

OpenAI has a significant advantage here. They've spent years building systems that understand human intent from limited input. Chat GPT interprets a text prompt that might be ambiguous or incomplete and produces a relevant response. The model has to infer intent, context, and desired outcome from minimal information.

Now imagine that model applied to neural signals instead of text. The model would need to interpret neural activity that's noisy, variable, and hard to standardize. It would need to understand what the user is trying to accomplish even when the neural signal is incomplete or ambiguous. It would need to learn from feedback and adapt to individual differences.

This is exactly what large language models are good at. They're trained on massive amounts of data to understand patterns and infer intent from incomplete information. Applying that capability to neural data is a logical extension.

OpenAI's contribution to Merge Labs includes "scientific foundation models and other frontier tools." Translation: they're going to build AI models specifically designed to interpret neural signals and understand user intent from those signals. This will take significant R&D, but OpenAI has the capability.

The real innovation might not be the hardware. It might be the software. The BCI that can interpret your intent at a neural level, learn your individual neural patterns, adapt to how your brain evolves, and seamlessly interface with AI systems is going to be powerful precisely because the software understands you at a deep level.

That's the moat. Not the electrodes or the molecules or the ultrasound, but the AI models that make sense of what the brain is doing.

Funding Landscape: Who's Backing What

The

Why? Because the potential market is enormous, and the companies that succeed could be worth tens of billions. If you can create a practical BCI that even 1% of the population adopts, you're talking about hundreds of millions of users. At any reasonable price point, that's an enormous market.

Numerical analysis: if BCIs become a consumer product, assume a TAM (total addressable market) of 1 billion potential users globally. Assume even 10% adoption is possible (which is low if the technology works and becomes cheap). That's 100 million users. At an average revenue per user of

Of course, those are big assumptions. But the math explains why investors are interested.

The sources for Merge Labs' funding aren't fully public yet, but OpenAI being the largest check suggests that other investors included major venture firms and possibly strategic partners. The fact that Altman is involved probably helped attract attention, for better or worse.

Neuralink's funding path has been different. It's primarily self-funded by Musk through his other companies and close associates. This gives Musk complete control but also limits funding to what he's personally willing to invest. Neuralink has probably cost Musk several billion dollars so far, which is meaningful but not catastrophic given his wealth.

Merge Labs' fundraising from multiple sources, including OpenAI, suggests a more traditional venture path. This could allow faster growth and more distributed risk, but it also means more stakeholders and more governance complexity.

Brain-computer interfaces could increase AI interaction efficiency by an estimated tenfold compared to current text and voice interfaces, enabling richer and faster communication.

The Regulatory Path: Faster Than You Think

One underrated aspect of Merge Labs' non-invasive approach is regulatory advantage. The FDA treats invasive devices differently from non-invasive devices. Invasive devices require more extensive safety testing and clinical trials because they literally enter the brain.

Non-invasive devices face lower regulatory hurdles. If Merge Labs can prove their technology doesn't pose safety risks (no unexpected heating from ultrasound, no neurological harm from the molecular markers, etc.), they might be able to move into human trials faster than Neuralink did.

Neuralink had to navigate the FDA's de novo pathway for truly novel devices. That meant no existing regulatory framework existed. They had to work with the FDA to define what approval would even look like. Neuralink eventually got approval, but it took time and probably a lot of discussion.

Merge Labs might be able to navigate the 510(k) pathway, which is for devices substantially similar to existing approved devices. This is faster. If they can argue their technology is substantially similar to other non-invasive neural measurement devices (like EEG or fMRI scanners), they might get regulatory clearance in 2-3 years instead of 5-7.

That's not a guarantee, and regulatory paths are always uncertain. But it's another advantage of the non-invasive approach.

The timeline probably looks like this: 1-2 years for technology development and preclinical validation, 2-3 years for regulatory work and FDA approval, 2-3 years for limited clinical trials to prove safety and efficacy. That puts a functional medical-grade BCI from Merge Labs maybe 5-8 years out, which is ambitious but not impossible.

The Ethics Question: Who Gets Augmented?

Here's the conversation no one in Silicon Valley wants to have, but everyone should: if BCIs become available, who gets them?

Initially, they'll be expensive. Very expensive. The hardware will cost tens of thousands of dollars. The surgery (or fitting process for non-invasive devices) will cost thousands more. The software subscriptions will add ongoing costs. The initial users will be wealthy people, researchers with well-funded labs, maybe some patients with serious medical conditions covered by insurance.

That's not necessarily wrong. Most new technology follows this pattern. But BCIs are different because the advantage compounds. If a researcher can think 2x faster with a BCI, they become more productive. They publish more papers. They get more grants. They buy better BCIs. The gap widens.

Over decades, this could create a society where some people have AI-augmented minds and others don't. The augmented people would be smarter, faster, more capable. They'd control more resources. The technology gap becomes a power gap becomes a class gap.

Altman frames this as necessary for surviving superintelligent AI. But you could also frame it as a way to create a permanent underclass of unaugmented humans.

There's no obvious solution here. You can't prevent technology development because you're worried about inequality. But you also can't ignore the implications.

Some possible approaches: mandate insurance coverage for BCIs so they're not purely private purchases. Require open standards so no single company controls the technology. Tax the companies profiting from BCIs to fund equitable access. Create public versions of BCI technology like we do with other medical devices.

None of these are perfect, and implementing any of them would require regulatory action that doesn't exist yet.

The Competitive Landscape: More Players Than You Think

Merge Labs and Neuralink are the most famous BCI companies, but they're not alone. There's a whole ecosystem of startups and research institutions working on neural interfaces.

Intelligence and Moore (now part of a larger group) has been working on non-invasive BCIs using similar ideas to what Merge Labs is attempting. Brain Gate is an academic-led effort focused on neural prosthetics. Synchron is working on a less invasive endovascular approach that doesn't require opening the skull. Kernel is developing hardware for measuring and potentially stimulating neural activity.

The competitive landscape is crowded, which suggests two things: first, the technology is moving fast enough that multiple approaches seem viable. Second, the prize is big enough that lots of companies think they can win.

Merge Labs' advantages are clear: a founder with deep connections to AI (Altman), backing from the most powerful AI company (OpenAI), a team with relevant neuroscience experience, and a technical approach (non-invasive) that has fewer adoption barriers than invasive alternatives.

Their disadvantages: they're less proven than Neuralink, their technology is more technically ambitious and less proven, and they don't have Neuralink's first-mover advantage in human trials.

In the long run, this might be a Betamax vs. VHS situation where multiple approaches coexist. Neuralink focuses on high-precision, medical-grade BCIs for people who need them most. Merge Labs focuses on broad accessibility. Other companies work on specific applications or niche use cases.

Or one approach crushes the others. If Merge Labs achieves signal quality comparable to invasive BCIs without the surgery, they win. If invasive BCIs turn out to be dramatically superior and people accept the surgery risk, Neuralink wins. Both outcomes are plausible.

Estimated data suggests that BCI adoption could reach 50% by 2046, with significant growth starting around 2041 as technology becomes more accessible.

The Hardware-Software Integration: Where Real Value Exists

The smartest thing about OpenAI's investment is that it ensures integration between hardware and software from the earliest stages. Most medical devices get developed with the hardware in mind and the software bolted on later. It's inefficient.

But OpenAI is committing resources to build the software alongside the hardware. They're helping architect what the interface will look like, what data the hardware needs to capture, how the models will interpret the signals, and how the system will adapt to individual users.

This is how you build truly innovative products. The hardware enables certain possibilities, the software realizes them.

Consider the iPhone. The real innovation wasn't the hardware. It was the touch interface, the app ecosystem, the integration between hardware and software that made the whole thing work. The competitors had similar processors and similar hardware capabilities. They lost because their software was worse.

Merge Labs could win the same way. Even if other companies develop comparable BCI hardware, if Merge Labs has better software for interpreting neural signals and understanding intent, they win. And OpenAI is well-positioned to build that software.

The integration also works the other way. As Merge Labs develops a practical BCI, they'll learn what signals are most useful to capture, what latency is acceptable, what error rates users tolerate. That feedback flows back to OpenAI, helping them build better models. It's a virtuous cycle.

Neuralink doesn't have this advantage. Musk is a brilliant engineer, but OpenAI is a better AI company. Pairing a mediocre AI system with a great BCI means the BCI underperforms its potential. Pairing a great AI system with a good BCI means the BCI becomes great through software.

Timeline and Milestones: What to Watch For

If you want to track Merge Labs' progress, here are the milestones that matter:

Year 1 (2026): Prototype development and preclinical validation. You'll probably see published papers describing the technology in more detail. Academic conferences like the Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting will feature research from Merge Labs.

Year 2 (2027): Regulatory strategy becomes public. You'll hear about FDA meetings and the pathway they're pursuing for approval. They might announce animal testing protocols.

Year 3 (2028): First human trials in limited cohorts, probably with patients who have medical needs rather than healthy enhancement candidates. Early results from these trials will determine whether the technology actually works.

Year 4-5 (2029-2030): Broader clinical trials. More data about safety and efficacy. Potential acquisition by a larger healthcare company, or continued independence with significant funding success.

Neuralink is already 3-4 years ahead on this timeline. They've had human patients using their devices. So Merge Labs is playing catch-up in some sense. But the non-invasive approach might accelerate certain phases.

Watch for academic partnerships. Universities will be where much of the early research happens. Caltech's involvement (through founder Mikhail Shapiro) is significant. Other major neuroscience research institutions might join in collaborative efforts.

Watch for talent moves. Top neuroscientists, AI researchers, and bioengineers will be recruited. Their moves signal where the field thinks progress will happen.

Watch for regulatory filing announcements. When Merge Labs applies for FDA approval to conduct human trials, that's when the technology becomes real rather than theoretical.

Watch for investment follow-ups. The $250 million seed round is just the first step. If the technology is working well, Series A and Series B rounds will follow. If it's struggling, follow-on funding might be harder to get.

What This Means for Open AI's Strategy

Zooming out, this investment reveals something important about how OpenAI thinks about the future. They're not content to build language models and sell API access. They're building a broader vision of how AI and humans will interact.

The jio hardware project with Jony Ive suggests they think the interface needs complete rethinking. No screens. Probably something voice-based or gesture-based or eventually neural. The Merge Labs investment suggests they think the ultimate interface is direct neural connection.

This is a 10-20 year vision. OpenAI is positioning itself to own multiple layers of the AI-human interface stack: the models (via Chat GPT and other products), the hardware (via partnerships with io), and now the neural interface (via Merge Labs).

It's ambitious. It's also potentially monopolistic if one company controls all layers. But from OpenAI's perspective, it's rational strategic thinking.

The other dimension is risk hedging. If BCIs become important, OpenAI wants to be involved. They're hedging against a future where someone else owns the BCI technology and controls access to human brains. By investing in Merge Labs, they're ensuring they have influence and access.

It's also about keeping Sam Altman happy. Whether you think that's good corporate governance or a problem depends on your view of founder control. But it's real.

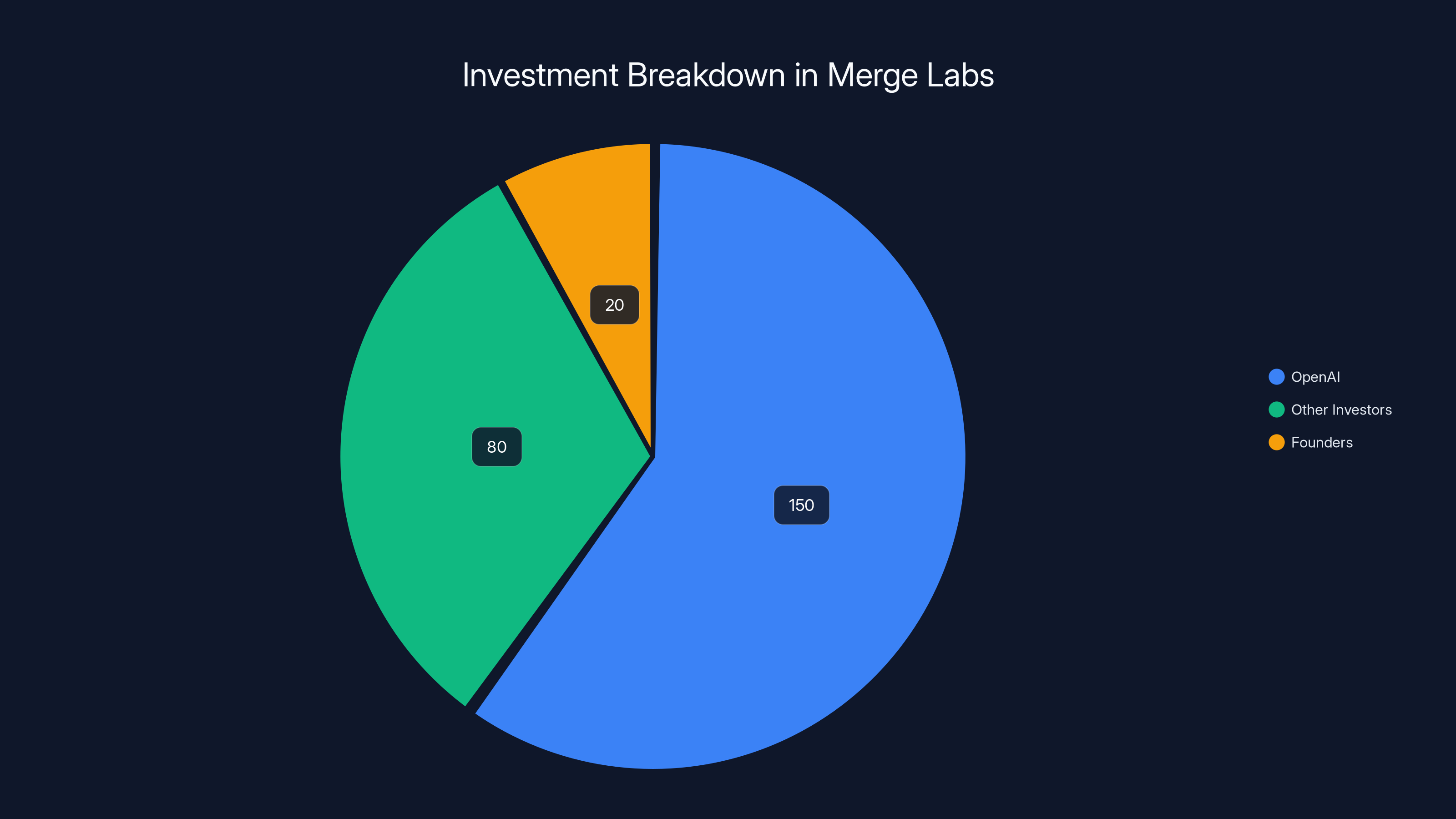

OpenAI leads the investment in Merge Labs with an estimated $150 million, highlighting its strategic interest in brain-computer interfaces. Estimated data.

The Broader AI Context: Integration and Control

There's a larger trend here that's worth noting. AI companies are increasingly integrating vertically. They're not just building models. They're building applications, platforms, hardware, and infrastructure.

OpenAI is doing this with io (hardware), with partnerships for deployment, and now with Merge Labs (neural interface). But they're not the only ones. Google is integrating AI across hardware (Pixel phones, smart home devices), software (Android, Chrome), and services. Microsoft is integrating AI into Office, Windows, and Azure. Meta is building AI into their social platforms and now eyeing AR hardware.

The logic is clear: if you control the full stack, you control the experience. You can optimize all layers together. You can ensure your models are used. You can capture more value.

The concern is equally clear: if any single company controls all layers of human-AI interaction, they have enormous power. They could influence what information people see, how they think, what they're capable of. That's a lot of power in one entity.

Merge Labs is just one piece of this larger story. But it's an important piece because BCIs, more than any existing interface, would put a company directly inside human cognition.

Predictions: Where This Goes

Let me make some predictions based on the available information:

In 5 years (2031): Merge Labs has working prototypes tested in humans with positive results. The non-invasive approach proves viable. They're ready for broader human trials. OpenAI's software is being used to interpret signals. The competitive advantage is becoming clear.

In 10 years (2036): BCIs are becoming more common but still expensive and primarily medical. The enhancement angle hasn't fully materialized because the technology still requires meaningful effort to use effectively. Some wealthy people have BCIs for productivity enhancement, but it's not mainstream. Neuralink and Merge Labs are the two dominant companies.

In 15 years (2041): If the technology continues improving, BCIs become more accessible. Pricing comes down. The enhancement use case becomes real. Some percentage of the population (maybe 5-10% in wealthy countries) use BCIs regularly. Questions about cognitive inequality become serious policy concerns. Regulation emerges requiring open standards or equitable access.

In 20 years (2046): Assuming the technology keeps advancing, BCIs could be as common as smartphones are today. The ultimate vision of humans and AI being tightly integrated might start becoming real. This is where the existential questions get serious.

These are guesses, not predictions. Technology almost always takes longer than optimists think and faster than pessimists expect. But the direction is clear: BCIs are coming, and they're going to be important.

The Sam Altman Thesis: Merging With AI

In his 2017 post about the Merge, Altman wrote that "the world's most powerful humans would be enhanced humans. That's not surprising or troubling, because that's already true in a sense." He also wrote that a merge with AI is humanity's "best-case scenario" for surviving superintelligent AI.

The argument is that if superintelligent AI emerges as a separate entity with its own goals, humans might be left behind. We'd be to superintelligent AI what insects are to us. But if humans can merge with AI, becoming partially artificial ourselves, we stay relevant. We stay in control. We become one with the force that's most powerful.

There's something compelling about this logic, and something troubling. Compelling because it acknowledges the potential power of AI and tries to find a way for humans to remain central. Troubling because it assumes merger is inevitable or necessary rather than one possible path among many.

Altman has spent years positioning himself as the person leading this future. Through OpenAI, he influences AI development. Through Merge Labs, he's influencing how humans might interface with AI. Through his other companies, he's building the supporting infrastructure (nuclear energy, biotech, eye scanning).

Whether you see this as far-sighted leadership or suspicious consolidation of power probably depends on your general view of tech concentration. But it's undeniably ambitious.

What We Don't Know: The Real Uncertainties

Before we conclude, let's be clear about what we actually know versus what we're assuming:

We know: OpenAI invested in Merge Labs. The round is

We don't know: How much the technology actually works. Whether the non-invasive approach can achieve signal quality sufficient for practical applications. How long it will take to get regulatory approval. Whether there's sufficient demand for non-invasive BCIs if they sacrifice some signal quality compared to invasive approaches. Whether other companies will develop competitive technologies that are better or cheaper.

We're assuming: That BCIs will become important. That the market is large enough to justify the funding. That OpenAI's involvement accelerates development. That Altman's motivations are primarily about advancing the technology (versus personal enrichment). That the timeline moves forward at a reasonable pace.

These assumptions are probably reasonable, but they're still assumptions. BCIs could remain a niche medical technology. The non-invasive approach could prove inferior to invasive alternatives. Regulation could be more restrictive than expected. The technology could turn out to be harder than anyone currently thinks.

But the direction is clear enough. This is a bet that BCIs matter and that Merge Labs plus OpenAI is the best positioned team to develop them.

Conclusion: The Interface Between Humans and AI Is the Real Game

We started with a straightforward announcement: OpenAI invested in Merge Labs. We've spent considerable effort understanding why this matters and what it reveals about the future of AI.

The simple version is this: the constraint on AI usefulness isn't computational power anymore. It's bandwidth. How fast and effectively can humans communicate intent to AI systems and receive back useful results? Right now, that bandwidth is limited by text, voice, and vision interfaces. A brain-computer interface would increase bandwidth by orders of magnitude.

OpenAI is betting that BCIs will become important. They're positioning themselves as the company that will power the software layer that interprets neural signals. Sam Altman is positioning himself as the person who sees this future most clearly and is building multiple companies to pursue it.

Whether this works out depends on whether Merge Labs can actually develop working non-invasive BCIs, whether they're useful enough to justify adoption, whether OpenAI's software can interpret neural signals effectively, and whether the whole package is better than alternative approaches (like Neuralink's invasive method).

There are real technical challenges here. There are real ethical concerns about enhancement inequality. There are real questions about whether this is the right direction for humanity or a distraction from more important problems.

But one thing's clear: this $250 million investment is not just about Merge Labs. It's about OpenAI's long-term vision of how humans and AI will interact. It's about Altman's vision of the future of human-machine integration. It's about the next frontier in technology, where the interface between biology and artificial intelligence becomes the most important thing.

And it's about the fact that the most powerful companies and individuals in tech are betting serious money that this future is worth building toward.

FAQ

What is Merge Labs?

Merge Labs is a brain-computer interface startup co-founded by Sam Altman and others. The company is developing non-invasive neural interface technology designed to connect human brains with artificial intelligence systems. Rather than using implanted electrodes like Neuralink, Merge Labs aims to use molecular-level technology and ultrasound to read neural signals without requiring surgery.

How does Merge Labs' technology differ from Neuralink?

Merge Labs is pursuing non-invasive neural interfaces that don't require brain surgery, using molecular technology and ultrasound instead of electrode implants. Neuralink requires surgical implantation of electrode threads into the brain. The tradeoff is that Neuralink's invasive approach provides higher signal precision, while Merge Labs' non-invasive approach is safer and more accessible but technically more challenging.

Why did Open AI invest in Merge Labs?

OpenAI invested because brain-computer interfaces represent the next frontier for human-AI interaction. BCIs would dramatically increase the bandwidth for communication between humans and AI systems. OpenAI is committing to develop the AI software and foundation models that interpret neural signals. If BCIs become widespread, this positions OpenAI as the default provider of the software layer that makes the hardware useful.

What is the circular deal problem with this investment?

The "circular" aspect refers to how the investment benefits both companies. OpenAI invested in Merge Labs, where Sam Altman is CEO of OpenAI and co-founder of Merge Labs. If Merge Labs succeeds with a practical BCI, that BCI likely needs OpenAI's software to function. Success for Merge Labs drives adoption of OpenAI's software. Success for OpenAI's software increases the value of Merge Labs' hardware. Both investments in Altman-connected companies and investments that benefit OpenAI create a pattern that some view as concerning.

How long until Merge Labs' BCIs are available to consumers?

Based on typical timelines for medical device development, functional BCIs from Merge Labs are probably 5-8 years away, assuming regulatory approval and successful human trials. The non-invasive approach might move faster than invasive approaches because it faces lower regulatory hurdles, but they're still starting from research stage. You can expect academic papers and announcements about human trials in the next 2-3 years.

Is this technology safe?

The non-invasive approach using ultrasound and molecules is theoretically safer than invasive electrode implants because it doesn't require brain surgery. However, the technology is still being developed and hasn't been tested extensively in humans. All new medical devices carry risks until they're fully validated through clinical trials. Merge Labs will need FDA approval before offering any devices to the public, which involves rigorous safety testing.

What are the ethical concerns with BCIs?

The main ethical concerns are: (1) enhancement inequality if BCIs become expensive luxury technology available only to wealthy people, (2) privacy and autonomy if companies can interface directly with human brains, (3) potential for coercion or control if neural interface software can be modified, and (4) unknown long-term health effects of using neural interfaces regularly. These concerns are serious and currently lack clear regulatory or policy answers.

Could brain-computer interfaces change human intelligence?

In theory, yes. If BCIs allow direct communication between human brains and AI systems, humans could access information and processing power far beyond current capabilities. A person could theoretically think 10x faster or access vast databases of knowledge instantly. Whether this constitutes "changed intelligence" or just "augmented capabilities" is philosophical, but the practical effects would be significant.

How does this investment relate to AI safety and alignment?

Brain-computer interfaces add complexity to AI safety by creating a tight coupling between human cognition and AI systems. If the AI system has goals misaligned with the human operator, the interface could propagate those misalignments at the neural level. Conversely, some argue BCIs help with AI alignment by keeping humans directly involved in AI decision-making. The relationship is complex and still being thought through.

What's the market size for BCIs?

The addressable market depends on how many people want or need BCIs. Medical applications (stroke recovery, paralysis, neurological conditions) address maybe 50 million people globally. Enhancement applications could address hundreds of millions if the technology becomes cheap and safe. Current estimates value the BCI market at $20+ billion by 2030, with potential for much larger growth if consumer adoption happens.

Key Takeaways

- OpenAI's $250 million investment in Merge Labs signals that brain-computer interfaces are critical to AI's future, not just medical devices

- Merge Labs' non-invasive approach using ultrasound and molecules differs fundamentally from Neuralink's invasive electrode implants, offering broader accessibility

- The investment reveals how AI companies are integrating vertically across hardware, software, and interfaces to control complete ecosystems

- Sam Altman's multiple companies (OpenAI, Merge Labs, Tools for Humanity) create strategic synergies that could accelerate BCI development or raise governance concerns

- Functional BCIs from Merge Labs are estimated 5-8 years away, with significant regulatory, technical, and ethical challenges remaining

Related Articles

- Meta Compute: The AI Infrastructure Strategy Reshaping Gigawatt-Scale Operations [2025]

- Why AI PCs Failed (And the RAM Shortage Might Be a Blessing) [2025]

- AI PCs Are Reshaping Enterprise Work: Here's What You Need to Know [2025]

- CES 2026 Best Tech: Complete Winners Guide [2026]

- Meta Ray-Ban Smart Glasses Handwriting Feature: Complete Guide [2025]

- Best Tech of CES 2026: 15 Innovations That Matter [2025]

![OpenAI's $250M Merge Labs Investment: The Future of Brain-Computer Interfaces [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/openai-s-250m-merge-labs-investment-the-future-of-brain-comp/image-1-1768497009775.jpg)