Meta Compute: Reshaping AI Infrastructure for the Gigawatt Era

Introduction: The Billion-Dollar Bet on Computation

Meta just made a move that most companies bury deep in their organizational charts. Instead, it elevated AI infrastructure planning to the C-suite level, creating a dedicated division that reports directly to Mark Zuckerberg. The move isn't flashy. No press conference. No keynote speech. Just a quiet restructuring that signals something massive is happening behind the scenes.

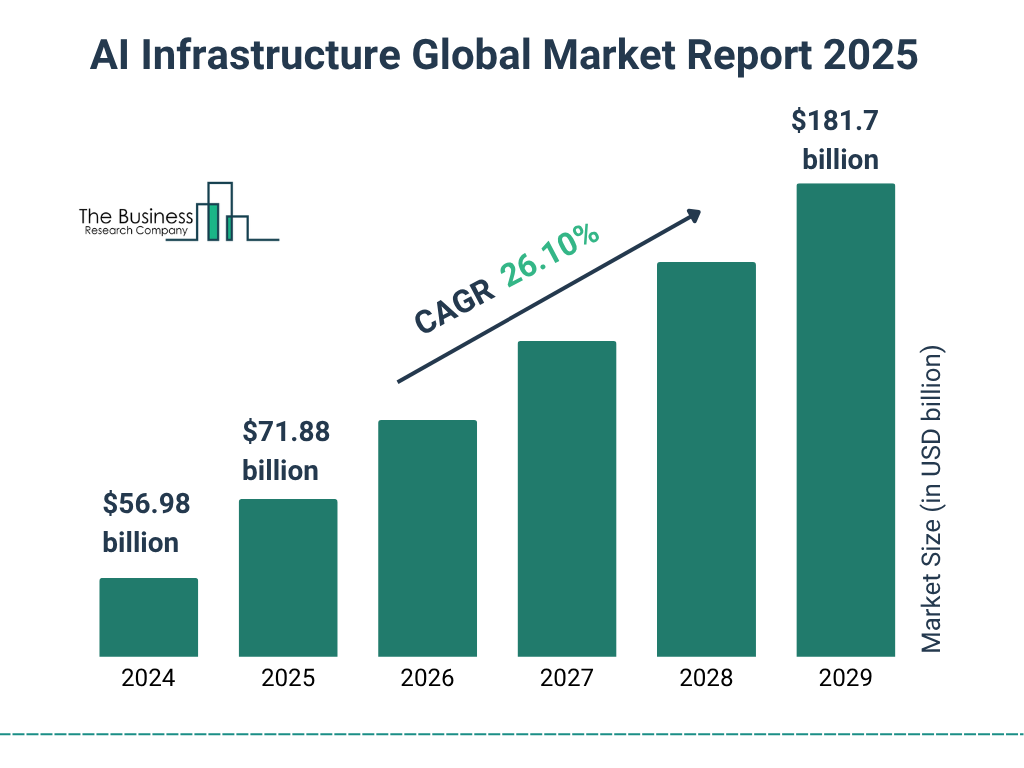

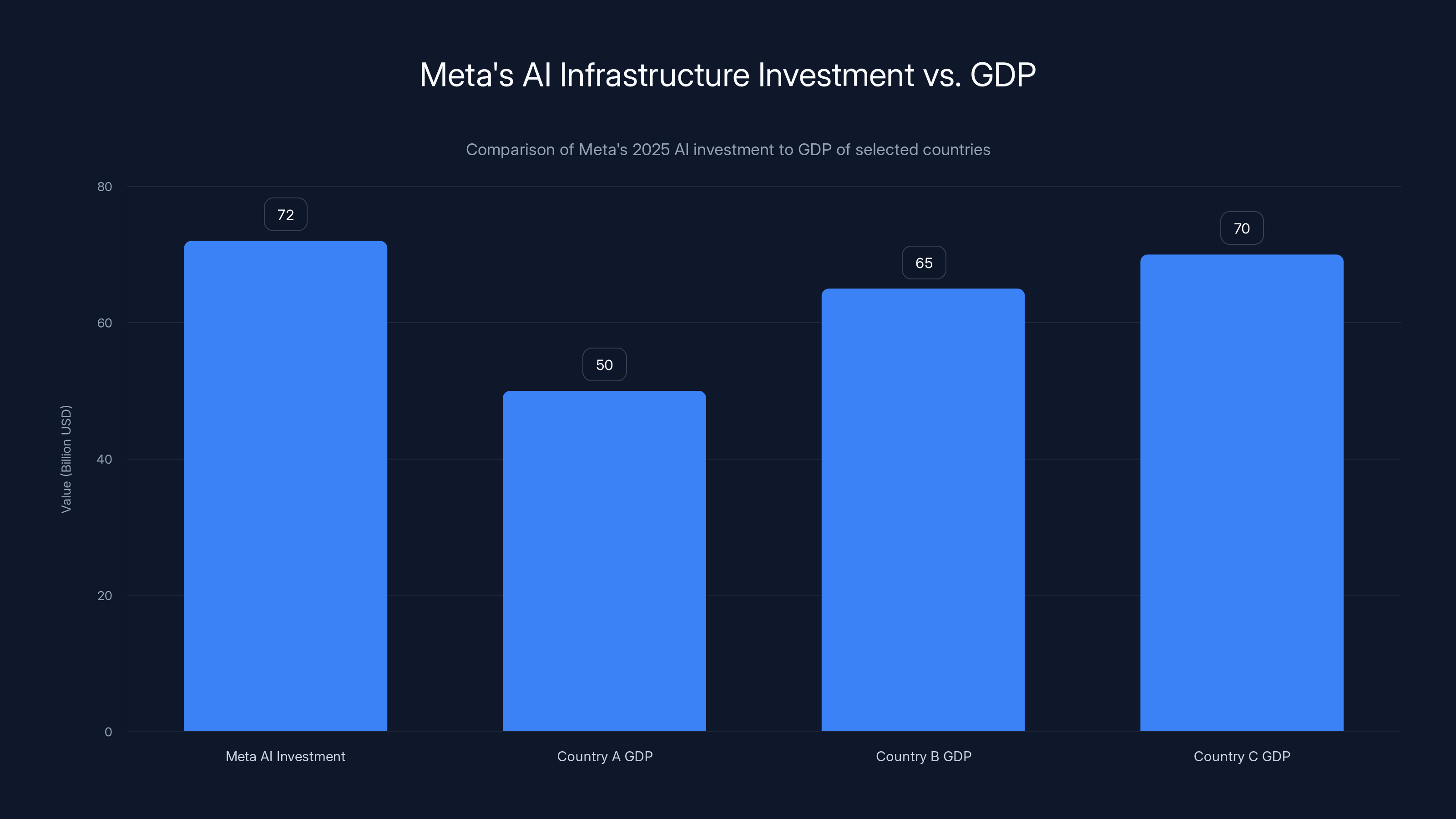

Here's the context: Meta spent roughly $72 billion on AI-related infrastructure and development in 2025. That's more than the annual GDP of many countries. Yet despite this staggering investment, the financial return remains murky. The company hasn't definitively proven that these expenditures translate into profitable AI products at scale. So why double down?

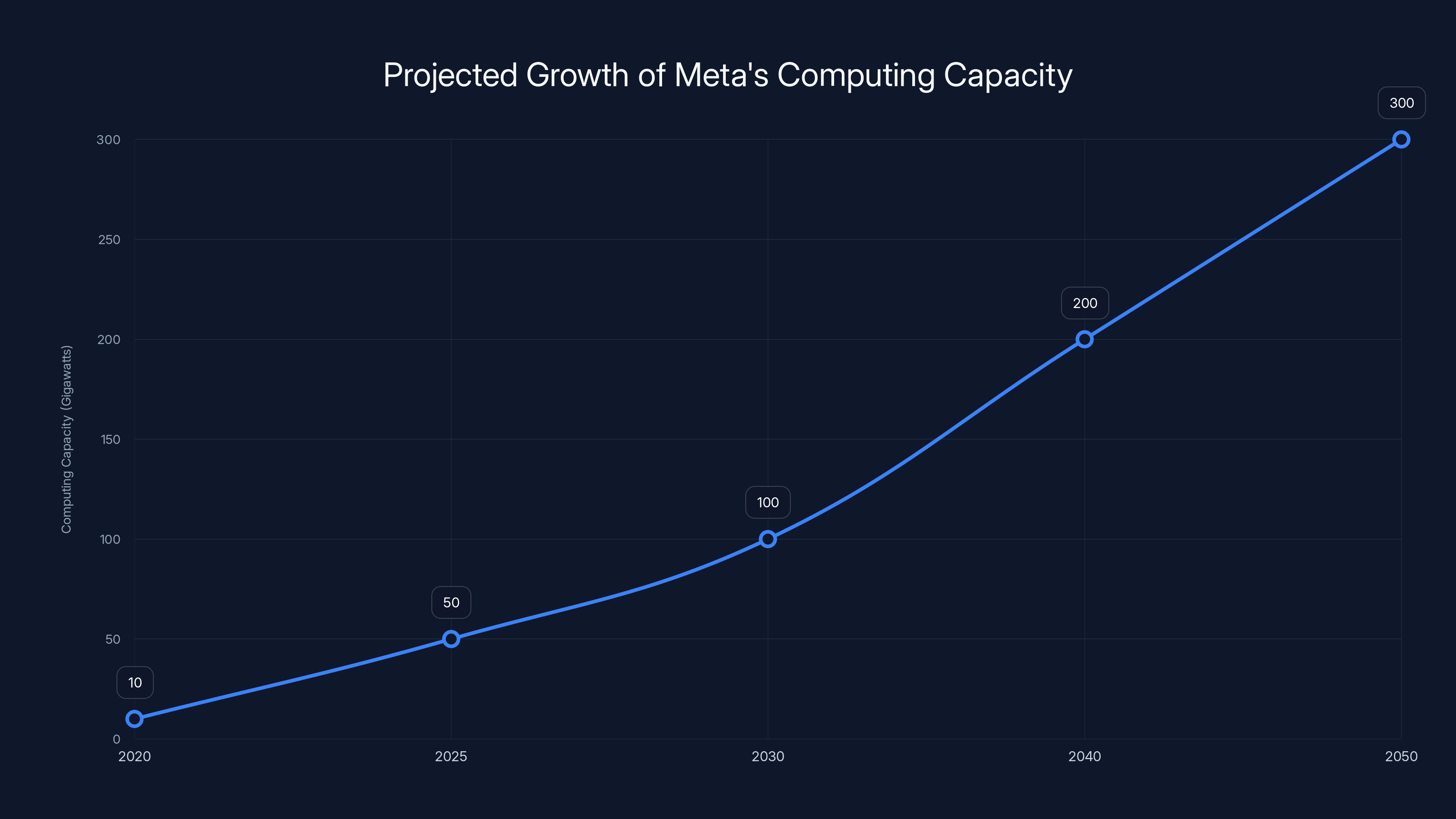

The answer is in Meta's ambition: tens of gigawatts of computing capacity this decade, scaling into hundreds of gigawatts over time. To put that in perspective, a single gigawatt powers roughly 750,000 homes. Meta is talking about building infrastructure for millions of homes worth of computing power. That's not incremental growth. That's redefining what scale means in the data center industry.

The creation of Meta Compute signals a fundamental shift in how Meta views infrastructure. It's no longer just supporting existing services like Facebook or Instagram. Instead, infrastructure has become the foundation for competing in AI itself. The company that can build and operate the largest, most efficient data centers wins the AI race. Everyone else is renting capacity or playing catch-up.

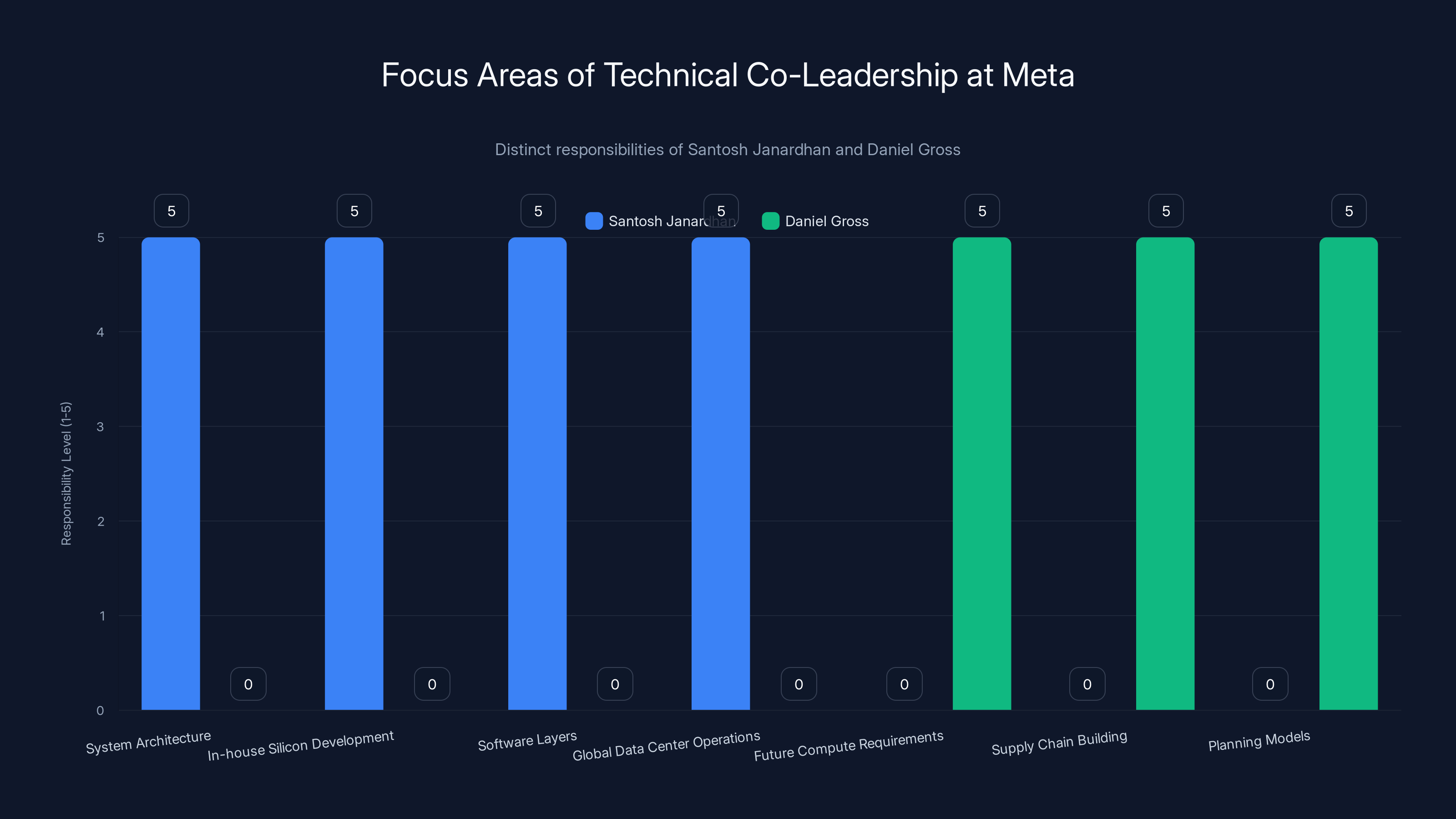

This reorganization brings together software engineers, hardware designers, networking specialists, and facilities planners under one umbrella. The two co-leaders, Santosh Janardhan and Daniel Gross, split their focus between execution and long-range strategy. Janardhan handles the technical details: system architecture, custom silicon, software layers, and operating the global data center fleet. Gross focuses on the future: modeling demand, building supply chains that can deliver hardware at multi-gigawatt scales, and planning for constraints nobody's had to think about before.

What's fascinating is what this division doesn't do. Meta Compute handles strategy and long-term capacity planning. Day-to-day data center operations remain with existing infrastructure teams. This separation is intentional. It's designed to prevent the trap that catches most large companies: reactive scaling driven purely by short-term demand. Meta Compute thinks in decades. It's building for problems that don't exist yet.

The timing matters too. As AI workloads become more demanding, traditional cloud computing wisdom breaks down. The hardware and software co-design requirements are completely different from what worked for Facebook's social networking or Instagram's content delivery. You can't just buy more GPUs off the shelf and expect efficiency. Every architectural decision cascades through power consumption, cooling requirements, real estate needs, and supply chain complexity.

When you combine this with Meta's stated goal of investing $600 billion in U.S. infrastructure and jobs by 2028, you're looking at the largest private infrastructure bet in tech history. It's not just about buying equipment. It's about building relationships with power utilities, acquiring land in strategic locations, managing environmental concerns, and keeping pace with innovation cycles that move faster than traditional capital equipment.

This article dives into what Meta Compute actually is, why it matters, how it works, what challenges it faces, and what it means for the AI industry. We'll cover the technical requirements, the business strategy, the environmental considerations, and what competitors are doing in response.

Meta plans to significantly increase its computing capacity from tens of gigawatts in the 2020s to potentially hundreds of gigawatts by 2050. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- Meta Compute unifies AI infrastructure across software, hardware, networking, and facilities under one top-level division reporting to Zuckerberg

- Tens of gigawatts planned this decade, with hundreds expected long-term, representing unprecedented scale in private data center deployment

- Custom silicon and co-design are critical differentiators, requiring tight integration between hardware and software teams

- Land, power, and cooling emerge as the real constraints in AI infrastructure, not GPUs

- Regulatory and environmental pressure is mounting on Meta and other hyperscalers, making planning and community relations essential

What Meta Compute Actually Is

Meta Compute isn't a single building or a product. It's an organizational structure designed to solve a specific problem: coordinating decisions about power, land, equipment, and networking as a single coherent system.

Traditionally, companies separate infrastructure concerns. One team buys hardware. Another designs software. A third manages data centers. A fourth handles real estate. This works fine when you're scaling incrementally. When you're trying to deploy tens of gigawatts—that's tens of thousands of megawatts—integration becomes the limiting factor.

Consider a typical scenario. An ML engineering team designs a new model that requires 50% more memory bandwidth than existing systems. Under the old structure, they'd request more GPUs. The hardware team would add them to the spec sheet. The facilities team would realize the power draw exceeds the data center's capacity. Six months of back-and-forth begins. By then, the model isn't cutting-edge anymore.

Meta Compute collapses this timeline by having everyone in the room simultaneously. If the ML team wants more memory bandwidth, the hardware designer immediately calculates power implications. The facilities team checks whether they have power available at that location. If not, they flag it early enough to plan for it. Decisions that used to take months happen in days.

This structure also separates strategy from operations. Meta Compute focuses on the long game. Where should data centers be built? What will AI workloads look like in five years? How do we build supply chains that don't break under the weight of billion-unit demand? What's the next innovation that makes current hardware obsolete?

Meanwhile, teams like Meta's Global Fitness Infrastructure continue running existing data centers efficiently. They optimize what's already deployed. Meta Compute builds what's next.

Meta's $72 billion investment in AI infrastructure in 2025 surpasses the GDP of several countries, highlighting the scale of their commitment to AI development. (Estimated data for GDP values)

The Technical Co-Leadership Model

Santosh Janardhan and Daniel Gross run Meta Compute together, but their responsibilities are distinct and complementary.

Janardhan comes from decades in system architecture and chip design. His domain includes the deeply technical aspects: system architecture (how GPUs, CPUs, memory, and networking connect), in-house silicon development (Meta designs its own chips rather than relying entirely on NVIDIA), software layers (the compilers, libraries, and frameworks that let code run efficiently on Meta's hardware), and global data center operations (the day-to-day management of deployed capacity).

This is the "what we're building right now" side of the equation. Janardhan's job is making sure that every server deployed works at peak efficiency. If a 1% improvement in memory latency saves 10% of energy consumption across a fleet of hundreds of thousands of servers, that matters. That's hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Gross focuses on the future. His role includes defining future compute requirements (what will AI actually need?), building supply chains (how do we get CPUs, GPUs, memory, and cooling systems at the scale Meta needs?), and developing planning models (how do we predict demand when the entire field is moving that fast?).

This is the "what we'll need in 2030" side. Gross doesn't have to optimize existing infrastructure. He thinks about second-order effects. If AI models continue scaling at current rates, memory bandwidth requirements will triple. So he starts negotiating with chip vendors now for memory designs that don't exist yet. He acquires land in regions with reliable power. He builds relationships with equipment manufacturers.

The split reflects a deeper truth: building infrastructure at gigawatt scale requires different skills from operating data centers. You can't learn to do both simultaneously. Separating the roles acknowledges this reality.

Power Constraints: The Real Limiting Factor

Most people assume GPU availability limits AI infrastructure expansion. They're wrong. Power is the real constraint.

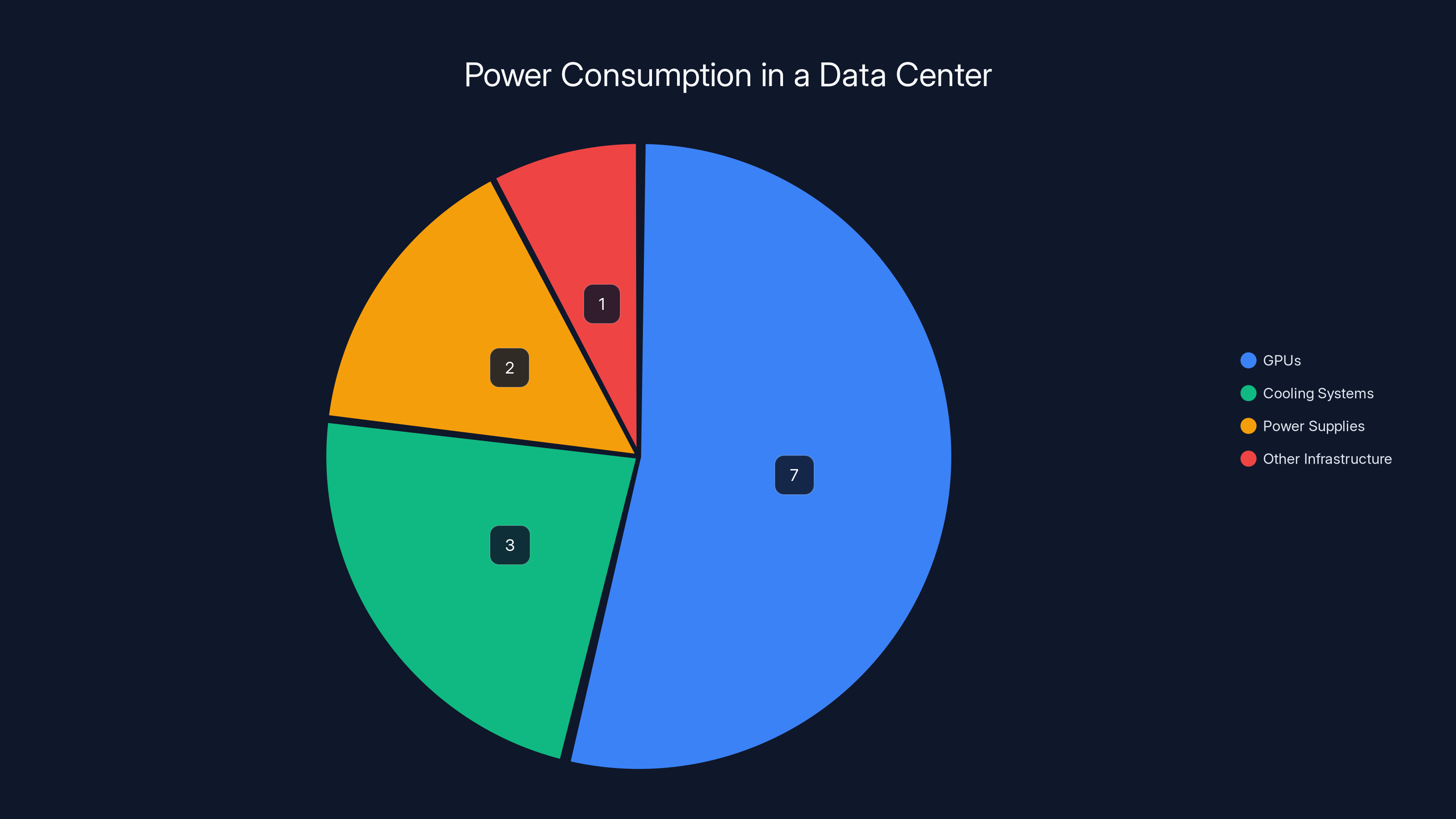

Here's the math. A state-of-the-art GPU like NVIDIA's H100 draws roughly 700 watts of power when fully utilized. A single data center might have 10,000 GPUs. That's 7 megawatts just for the processors. Add switches, cooling, power supplies, and losses, and you're easily at 10-15 megawatts total. A modest data center running a few thousand GPUs needs as much power as a mid-sized town.

Meta's gigawatt plans mean coordinating with electrical utilities at massive scales. It's not just about paying for power. Utilities need to:

- Upgrade transmission lines to deliver power to data center locations

- Build new power generation capacity or secure long-term contracts

- Manage grid stability with massive, bursty loads

- Plan for years in advance because electrical infrastructure takes time to build

Power isn't something you just buy more of. It's a scarce resource that requires cooperation from municipalities, state regulators, and national energy policy. Meta's infrastructure team now has to play a role in energy policy discussions that used to be the domain of utilities and environmental advocates.

This is where Daniel Gross's supply chain work becomes critical. He's not just negotiating chip prices. He's securing long-term power contracts. He's identifying regions with clean, cheap power. He's probably negotiating with utilities about building dedicated power plants for Meta's use. These are thousand-person-year projects that unfold over decades.

Cooling adds another layer. Every watt of power consumed by a GPU becomes heat that needs to be removed. Traditional air cooling doesn't scale to data centers the size Meta is planning. Liquid cooling becomes necessary, but it introduces complexity. Where does the water come from? How do you cool the cooling systems? What happens to that heat?

Some companies are experimenting with immersion cooling—submerging servers in special fluids that conduct heat better than air. Meta's infrastructure team probably has a dozen different cooling technologies in development, each with trade-offs. One might be 30% more efficient but requires custom hardware. Another scales more easily but costs more to operate.

The point is this: power and cooling aren't side issues. They're the primary constraints. Everything else—GPUs, networking, storage—can be solved with money and time. But you can't build data centers if there's nowhere to put the power or nowhere for the heat to go.

Real Estate and Land Acquisition Strategy

Meta needs land. Lots of it. A single 100-megawatt data center occupies roughly 50-100 acres depending on layout and cooling approach. Scale that to gigawatts, and Meta needs thousands of acres across multiple geographic regions.

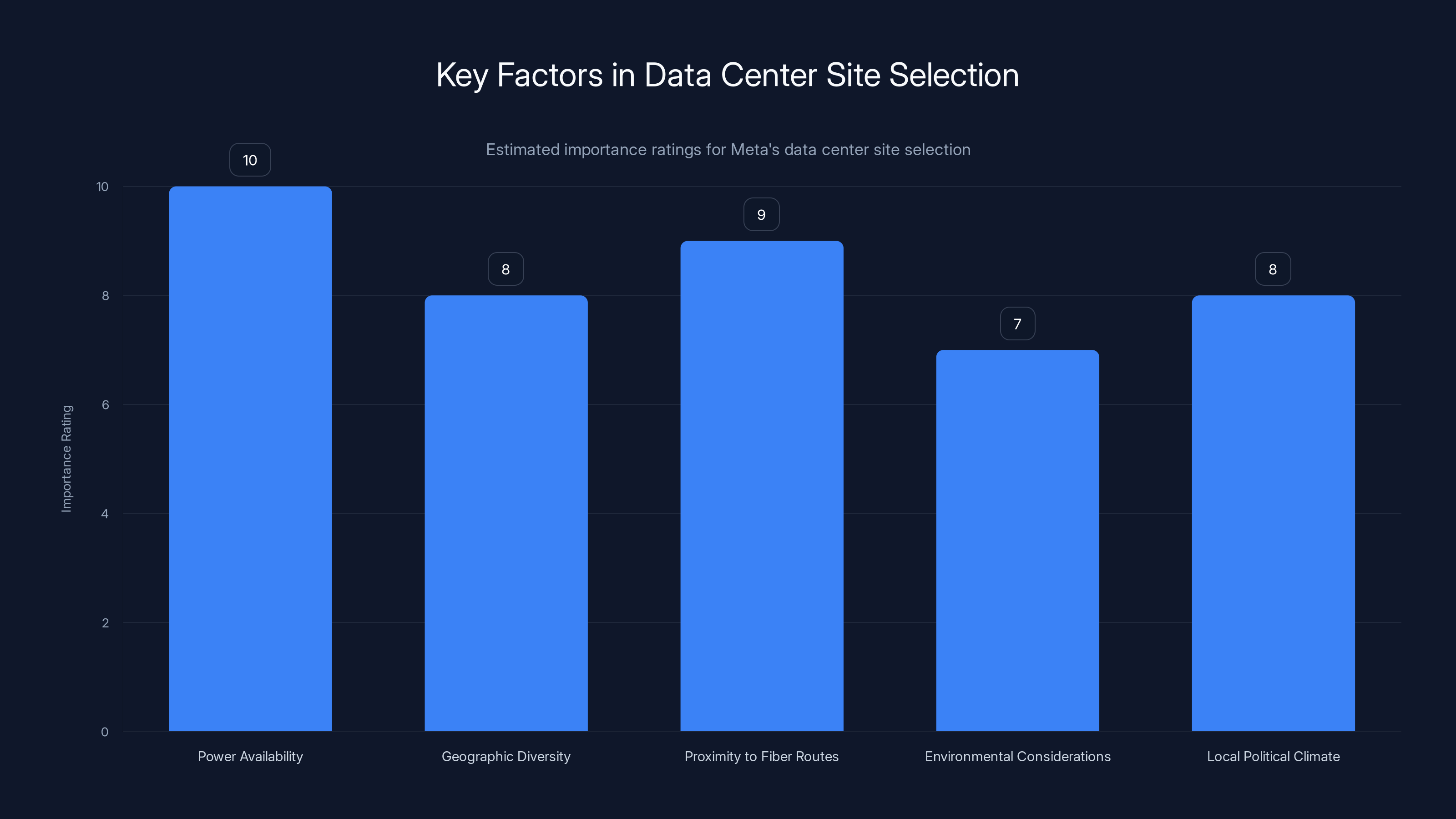

Land selection isn't random. Several factors matter enormously:

Power availability comes first. A data center location is useless without reliable, affordable electricity. This drives Meta toward regions with abundant hydroelectric power (Iceland, Norway, Sweden), geothermal power (parts of the U.S.), or nuclear capacity. It also makes Meta politically influential in those regions. When a company wants to build gigawatts of infrastructure, the local government pays attention.

Geographic diversity is critical for resilience. If one region loses power, services shouldn't go down. Meta needs data centers scattered across continents. This requires understanding regional infrastructure, politics, and environmental concerns in many countries simultaneously.

Proximity to fiber routes matters for connectivity. Data centers need ultra-low-latency connections to each other and to backbone networks. Building a data center in a remote location with great power but no fiber is useless. Meta either needs proximity to existing fiber infrastructure or must invest in building new routes.

Environmental considerations increasingly influence site selection. Water-intensive cooling makes some regions untenable due to drought concerns. Some countries have strict regulations about data center operations. Communities worry about environmental impact and job creation. Meta's infrastructure team has to navigate all these concerns.

Local political climate determines whether projects can move forward. A region might have perfect power and land, but if the local government opposes data centers, you're not building there. Meta is essentially becoming a geopolitical player, negotiating with governments about where to invest.

The $600 billion U.S. infrastructure commitment signals a strategic choice: focus on North America. This makes sense for several reasons. U.S. power grid is relatively stable. Property rights are clear. Regulations are knowable. Technology companies have established relationships in the U.S. The U.S. also provides access to talent for operating and maintaining facilities.

But land in the U.S. isn't unlimited, and the best sites get competitive. Meta is probably in land acquisition discussions with multiple regions simultaneously, leveraging federal and state incentives for infrastructure investment.

In a data center with 10,000 GPUs, the GPUs themselves consume about 7 megawatts, while additional infrastructure like cooling and power supplies account for 3 and 2 megawatts respectively. Estimated data.

Custom Silicon and Hardware Co-Design

Santosh Janardhan's responsibility for "in-house silicon development" deserves deep attention. Meta doesn't just buy NVIDIA GPUs. It designs custom chips.

Why? Because standard off-the-shelf hardware doesn't match Meta's specific workloads. Facebook's recommendation algorithms, Instagram's content ranking, and search systems all have particular requirements. NVIDIA makes general-purpose GPUs that work for everyone. Meta's chips are optimized specifically for Meta's problems.

A custom GPU might have:

- Different memory configurations optimized for Meta's bandwidth requirements

- Specialized instructions for AI operations Meta uses frequently

- Better power efficiency for Meta's specific workloads

- Interfaces optimized for Meta's network architecture

The tradeoff is complexity. Standard GPUs are tested, documented, and supported. Custom silicon requires Meta to hire world-class chip designers, invest in fabrication partners, and manage all the risks of hardware development. If a design has a flaw, you can't just patch it—you have to wait for the next revision.

But the upside is massive. If Meta can get 30% better power efficiency than standard GPUs, that's a gigantic advantage at multi-gigawatt scale. 30% on billions of dollars in power costs is hundreds of millions in savings annually.

This is also why Janardhan and Gross's roles integrate. Janardhan optimizes today's custom silicon. Gross plans tomorrow's. If current AI trends suggest memory bandwidth requirements will triple in five years, Gross tells chip designers to start work now on architectures that provide that. By the time workloads demand it, the hardware exists.

Custom silicon also provides strategic independence. Meta isn't as vulnerable to NVIDIA supply constraints. If NVIDIA's production hits bottlenecks, Meta still has internal capacity. This matters when supply is as tight as it is today.

The software layer on top of custom hardware is equally important. Companies like TensorFlow and PyTorch are general-purpose ML frameworks. Meta builds custom compilers and libraries optimized for its hardware. This creates a virtuous cycle: better hardware enables better software, which enables better AI, which justifies further hardware investment.

The Software-Hardware Integration Challenge

Most companies think of hardware and software as separate. You buy hardware, then write software to run on it. But at hyperscale, this separation becomes costly. Every inefficiency in hardware matching software requirements burns power and money.

Meta's structure recognizes this. By putting hardware and software teams under the same umbrella, decisions get coordinated. When a software engineer identifies that a particular operation would be 10x faster with custom hardware support, they can talk directly to the chip design team. When a hardware designer realizes a particular instruction could unlock 20% performance gains, they talk directly to the software teams.

This co-design approach isn't new—Apple does this with iPhone chips—but doing it at data center scale is rare. It requires organizational discipline. Without it, hardware teams build chips for yesterday's software, and software teams write code hoping hardware will catch up.

Consider memory bandwidth. Modern AI models are memory-bound, meaning performance is limited by how fast you can move data from memory to processors, not by raw compute power. A standard GPU might move 1 terabyte of data per second between memory and processors. But if your AI workload only needs 800 gigabytes per second, you've paid for capacity you don't use.

Meta's approach: design hardware with exactly the memory bandwidth needed, and write software that uses every bit of it. This saves power, reduces cost, and improves performance. But it requires intimate knowledge of both hardware capabilities and software requirements.

Networking at Gigawatt Scale

People underestimate networking. They focus on GPUs and power. Networking is equally critical.

When you have thousands of GPUs training a single model, they need to communicate constantly. A GPU in server A needs to share intermediate results with GPUs in server B. This happens billions of times per training run. If networking is slow, the GPUs sit idle waiting for data.

At small scales, standard networking equipment (switches, routers, Ethernet) works fine. At gigawatt scale, it becomes a bottleneck. You need:

- Custom network topologies that minimize the number of hops data travels

- Ultra-low latency switching (microseconds, not milliseconds)

- Massive aggregate bandwidth (terabits per second across the entire data center)

- Redundancy so that any single network component failing doesn't crash training

Meta probably has a team dedicated purely to data center networking architecture. They're optimizing switch placement, designing software-defined networking layers, and probably developing custom network chips.

This networking extends beyond individual data centers. Multiple data centers need to communicate too. Meta's "geo-distributed" approach means AI models might have some computation running in data centers on the East Coast and others on the West Coast. Coordinating this requires intercontinental networking capacity, and probably some clever algorithms that minimize the amount of data that needs to cross the continental network.

Cloud providers like AWS and Azure have invested heavily in this. Meta is doing the same, but with the added complexity that it's serving primarily Meta's internal needs, not external customers. This allows for optimization that wouldn't work in a multi-tenant cloud.

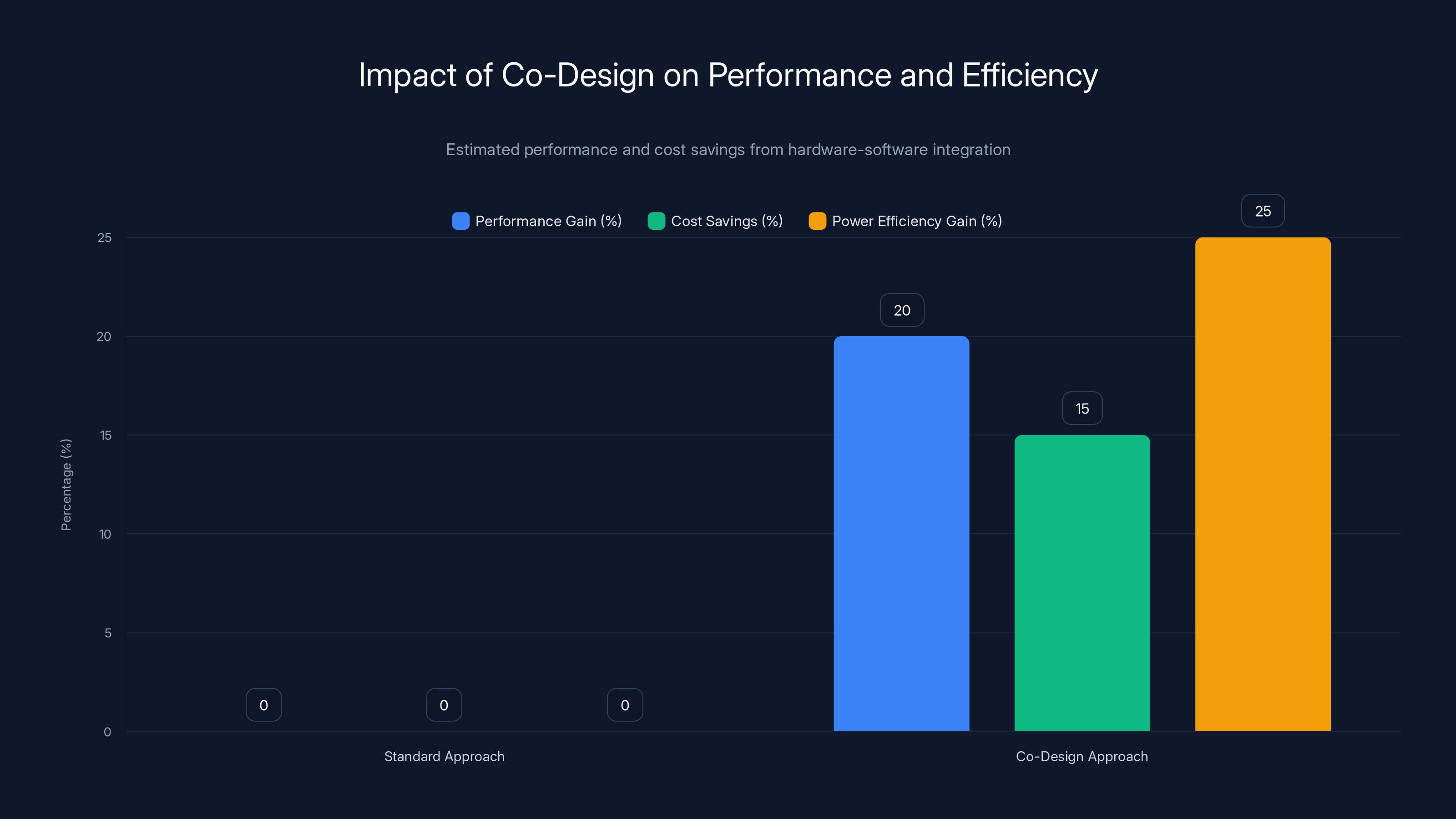

The co-design approach can lead to significant performance gains, cost savings, and power efficiency improvements by aligning hardware capabilities with software requirements. Estimated data.

Storage and Data Management

AI training requires massive amounts of data. ImageNet alone is 150 GB. Large language models are trained on trillions of tokens—terabytes or petabytes of text. Meta's training workloads are probably in the exabyte range (1 exabyte = 1,000 petabytes).

Storing this data and making it accessible to thousands of training GPUs across multiple data centers is a non-trivial engineering problem. You need:

- Storage systems that can handle exabyte-scale datasets

- Network bandwidth to stream data from storage to GPUs during training

- Redundancy to prevent data loss

- Organization systems to track and manage different versions of datasets

Traditional storage systems designed for web application workloads don't scale here. Meta probably uses a combination of approaches:

- Flash storage (SSDs) for active training datasets that need fast access

- Hard drives for archival and less-frequently accessed data

- Custom storage systems optimized for AI workloads

The data itself becomes a liability if not managed properly. Storing terabytes of training data isn't just expensive; it's complicated. You need to track versions, maintain provenance, ensure data quality, and manage access controls.

This is where Daniel Gross's planning becomes critical. As AI models scale, data requirements grow. Planning ahead for storage capacity means securing hardware now, building systems that scale, and developing data management practices that work at exabyte scale.

Workload Characterization and Demand Planning

Meta needs to predict how much compute it will need. This is hard. AI is a moving target. New architectures emerge constantly. What's cutting-edge this year is commodity next year.

Workload characterization involves understanding what Meta's AI systems actually do:

- Training workloads: Building new models requires massive compute over weeks or months

- Inference workloads: Running models to make recommendations and rank content for billions of users happens constantly

- Experimentation workloads: Trying different model architectures, hyperparameters, and techniques

- Development workloads: Engineers training small models locally or in clusters

Each workload has different characteristics. Training is bursty—you might need massive capacity for a month, then nothing. Inference is constant but variable (more users during certain hours).

Daniel Gross's planning models probably account for:

- Historical growth rates of compute demand

- Trends in AI model sizes (they keep scaling)

- New products Meta might launch

- Potential market dynamics (competition from Google, OpenAI requiring Meta to innovate)

- Technological improvements (more efficient algorithms, better hardware)

Getting this wrong is catastrophic. Build too little capacity, and you can't train new models fast enough. Competitors ship better products. Build too much, and you've sunk billions into infrastructure that sits idle.

The multi-year timeline of gigawatt deployment suggests Meta expects sustained, significant demand. This isn't a hedging strategy. It's a commitment.

Sustainability and Environmental Considerations

Here's where Meta Compute gets politically complex. Building gigawatts of infrastructure raises environmental concerns that can't be ignored.

Data centers consume vast amounts of electricity. Even if the electricity comes from renewable sources, the sheer scale triggers questions:

- Where does the water for cooling come from, and what's the environmental impact?

- What's the carbon footprint of manufacturing hardware and building facilities?

- How does this affect local power prices for other consumers?

- What happens to electronic waste when hardware is retired?

Meta faces pressure to address these concerns. Some of this is genuine environmental concern. Some is political pressure from communities worried about local impact.

Meta's approach likely includes:

- Commitment to renewable energy for powering data centers

- Water-efficient cooling technologies

- Recycling and refurbishment programs for hardware

- Transparency about environmental impact

- Collaboration with local communities

The sustainability angle also has a business component. Renewable energy is increasingly cheap. If Meta can secure long-term renewable power contracts, it gets cheaper electricity than competitors. This is a business advantage disguised as environmental commitment.

But the environmental concerns are real. Hyperscalers are making measurable impacts on regional power grids and water supplies. Ignoring this invites regulation. Building it into planning proactively is smarter.

The chart illustrates the distinct focus areas of Santosh Janardhan and Daniel Gross at Meta, highlighting their complementary roles in current infrastructure optimization and future planning.

Supply Chain Logistics and Resilience

Building gigawatts requires securing massive amounts of hardware. NVIDIA alone can't supply all the GPUs. Custom chips take years to design. Memory, networking equipment, and cooling systems all have their own supply chains.

Daniel Gross's supply chain work is probably the most underestimated part of Meta Compute. He's coordinating:

- GPU procurement from multiple vendors (NVIDIA, AMD, potentially Meta's own designs)

- Memory chip manufacturing partnerships

- Networking equipment suppliers

- Custom chip fabrication through partners like TSMC

- Power supply and cooling equipment

- Construction and materials for physical facilities

Any single bottleneck in this supply chain delays everything. If TSMC can't produce Meta's custom chips on schedule, the entire expansion slows. If suppliers run short on memory, projects pause.

Meta is probably in multi-year, multi-billion-dollar supply agreements with vendors. These negotiations are complex. Meta wants guaranteed capacity at favorable prices. Suppliers want predictable demand. The balance requires careful negotiation and trust.

Resilience matters too. Relying on a single supplier for critical components is risky. Meta probably diversifies suppliers even if it costs more. Having backup sources for GPUs, memory, and custom silicon means that if one supplier fails, projects continue.

This supply chain work is invisible to most people. It's not the kind of announcement Meta makes in blog posts. But it's absolutely essential. Without it, the grand vision of gigawatt-scale infrastructure is just fantasy.

Competitive Dynamics and the Race for Compute

Meta isn't alone in pursuing gigawatt-scale infrastructure. Google is doing it. Microsoft (for OpenAI and its own services) is doing it. Amazon Web Services is building for cloud customers. Everyone with serious AI ambitions needs massive compute.

This creates a competition for the most important resources:

-

GPU allocation: NVIDIA can't make enough chips for everyone. Companies fight for production slots. Meta's scale gives it leverage—a company buying tens of thousands of GPUs per month gets better pricing and allocation than smaller players.

-

Power contracts: Electricity is finite. If Meta secures long-term renewable power contracts in the most attractive regions, competitors have to find alternatives. This could mean higher power costs, less efficient locations, or reliance on less reliable power sources.

-

Talent: Building this infrastructure requires extraordinary engineering talent. The best chip designers, systems architects, and infrastructure engineers are in demand. Meta needs to attract and retain them. This means high salaries, interesting problems, and institutional investment in their development.

-

Real estate: Prime locations for data centers are competitive. Meta moving into a region early signals opportunity but also locks up land that competitors might want.

What Meta Compute signals is that the company is going all-in on compute as a competitive advantage. It's not outsourcing to AWS or Microsoft. It's not making do with limited capacity. It's betting that controlling its own infrastructure gives it strategic advantages that justify the investment.

Google is doing something similar with its Technical Infrastructure. Microsoft is doing it for cloud gaming and AI services. The convergence suggests that in the AI era, controlling your own infrastructure is becoming table stakes for competing at the highest level.

Governance and Organizational Alignment

Putting Meta Compute at the top level reporting to Zuckerberg is a governance choice with implications.

It signals that infrastructure decisions are CEO-level concerns. They're not delegated to middle management. They're not one of many competing priorities. They're central to Meta's strategy.

It also means Zuckerberg is personally accountable for the success or failure of these massive investments. The $72 billion spent in 2025 has to deliver returns. The hundreds of billions planned need to justify themselves.

This creates pressure, but also focus. Middle managers might hesitate to challenge a project when returns are uncertain. A CEO taking personal ownership has skin in the game. If it fails, it reflects directly on them.

The co-leadership structure with Janardhan and Gross reflects similar thinking. By not anointing a single leader, Meta is saying that execution and vision are equally important. You need both. Neither dominates.

This is different from how many companies structure infrastructure. Often, it's buried in ops, seen as a cost center. Meta is treating it as a profit center and a strategic asset.

Power availability is the most critical factor for Meta's data center site selection, followed closely by proximity to fiber routes and geographic diversity. (Estimated data)

Risk and Failure Modes

Building gigawatts of infrastructure is risky. Things can go wrong in multiple ways:

Technological obsolescence: The infrastructure Meta is building today might be obsolete in five years. New chip architectures might demand completely different infrastructure. New AI techniques might reduce compute requirements. Meta would have sunk billions into infrastructure that's no longer optimal.

This is why Daniel Gross's planning is critical. By constantly re-evaluating technology trends and adjusting plans, Meta tries to stay ahead. But this can't fully eliminate the risk.

Cost overruns: Building data centers at this scale is expensive and complex. Overruns are common. A facility that was budgeted at

Demand shortfalls: What if Meta's AI products don't need all this capacity? What if the business model doesn't support the spend? The company would have vast infrastructure with no revenue to justify it. This is the deepest risk. The entire strategy assumes Meta will find ways to use and monetize gigawatt-scale compute.

Regulatory changes: Governments might impose restrictions on AI, data centers, or power consumption. Environmental regulations might tighten. These could force Meta to shut down facilities or reduce capacity. Depending on scale, this could erase years of investment.

Geopolitical tensions: If U.S.-China tensions escalate around AI and chips, U.S. regulations might restrict selling AI infrastructure internationally. If Meta has planned international expansion, this could be disrupted.

Power grid instability: Relying on specific power sources creates vulnerability. If a regional power grid becomes unstable or unreliable, data centers in that region become useless. Diversification helps, but it's not foolproof.

Meta is managing these risks through diversification, staged investment (building gradually rather than all at once), and constant re-evaluation. But the fundamental risk of betting billions on uncertain returns remains.

Operational Excellence and Efficiency

Once infrastructure is built, running it efficiently matters enormously. A data center that's 5% less efficient than competitors costs hundreds of millions more to operate over its lifetime.

Operational excellence involves:

Power efficiency: Every watt matters. Reducing power consumption by 1% across gigawatt-scale infrastructure saves millions annually. This drives investments in:

- Better cooling systems

- More efficient power supplies

- Hardware that draws less power

- Software that minimizes compute through more efficient algorithms

Uptime and reliability: Data center outages are costly. Every minute of downtime affects billions of users and loses money. Meta invests in redundancy, monitoring, and maintenance practices that keep systems running.

Maintenance: Hardware fails. Storage devices wear out. Fans and cooling systems need servicing. Having maintenance practices that minimize downtime while keeping costs reasonable is a distinct discipline.

Capacity utilization: Keeping hardware fully utilized is hard. Sometimes workloads are bursty. Sometimes new capacity sits idle waiting for demand. Sophisticated scheduling and workload management keep utilization as high as possible.

Meta probably has teams dedicated to each of these areas. The work is unglamorous—optimizing cooling algorithms or managing spare parts inventory—but it's essential. This is where Santosh Janardhan's day-to-day operational role becomes critical.

Future Trajectory and Next Steps

Where does Meta Compute go from here?

Short term (next 2 years), Meta is probably focused on deployment. Building initial capacity in prime locations, validating that the organization structure works, and proving that custom hardware and integrated teams deliver advantages.

Medium term (2-5 years), Meta scales aggressively. If early results are positive, investments accelerate. New data center regions come online. Custom silicon production ramps up. Supply chain partnerships deepen.

Long term (5+ years), Meta is either a credible infrastructure company—a peer to Google and AWS in infrastructure sophistication—or it's realized that this bet didn't pay off and adjusted course.

The stakes are enormous. The company is betting that controlling infrastructure and having in-house expertise in every layer (chips, systems, software) provides advantages that justify multi-hundred-billion-dollar investments. If true, Meta's AI capabilities will be unmatched. If false, it's wasted capital.

Industry observers should watch for:

-

Custom chip announcements: How frequently are new Meta-designed chips announced? This signals innovation velocity.

-

Data center expansion announcements: Which regions is Meta choosing? This reveals geographic strategy and power priorities.

-

AI product launches: Does Meta's compute capacity translate into products that compete with Google and OpenAI? Or does it remain internally-focused?

-

Financial impacts: When does all this investment start showing up in revenue and profit? If it never does, investors will question the strategy.

-

Talent movements: Are top infrastructure engineers and chip designers leaving or joining Meta? This signals whether the strategy is attracting or losing talent.

-

Competitor responses: How are Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI responding to Meta's moves? Imitation suggests Meta is on the right track.

Implications for the Broader AI Industry

Meta Compute isn't just important for Meta. It signals something broader about the AI industry.

The first implication is that AI at scale requires integration. You can't bolt together off-the-shelf components and expect to compete. You need custom hardware, custom software, and deep organizational integration. This raises barriers to entry. Only companies with billions to invest in integrated infrastructure can really compete in AI.

The second implication is that infrastructure is becoming a strategic asset. The companies that can build and operate the most efficient, largest-scale infrastructure will have advantages in AI that are hard to overcome. This is a shift from the cloud computing era, where infrastructure was a commodity that companies bought. Now it's becoming proprietary.

The third implication is that the AI race is increasingly a game of capital availability and operational excellence. You need money to build, talent to design, and execution capability to operate. All three are rare. Only a handful of companies have all three simultaneously.

For smaller companies and startups, this is sobering. They can't match Meta, Google, or Microsoft in infrastructure. Their strategy has to be different—either focusing on specific applications where they don't need gigawatt-scale compute, or offering services that larger companies use. Pure AI research without infrastructure backing becomes harder to monetize.

Comparison to Competitor Approaches

Google has similar infrastructure ambitions but took a different path. It's integrated infrastructure from the beginning because Google Search required it. Google also built custom chips (TPUs) early. But Google's structure might keep infrastructure in specialized divisions rather than centralizing like Meta is doing.

Microsoft is outsourcing infrastructure to OpenAI partnerships and cloud services, building capacity on Azure. This is different from Meta's approach—Microsoft is relying on partnerships and cloud services rather than pure internal development. It's a different bet: that partnerships are more flexible than vertical integration.

OpenAI doesn't build its own infrastructure. It relies on Microsoft's cloud and buys GPUs. This limits OpenAI's margin and makes it dependent on Microsoft, but it avoids the capital requirements of building infrastructure. It's a strategic choice with tradeoffs.

Amazon Web Services is providing infrastructure as a service. AWS isn't competing with Meta and Google for proprietary AI. It's building infrastructure that anyone can rent. This is a different business model entirely.

Meta's bet is that vertical integration (building everything in-house) is better than partnerships (Microsoft's approach) or outsourcing (OpenAI's approach). History suggests vertical integration works well for companies at scale (Apple, Meta's earlier web infrastructure) but also creates dependencies and rigidity.

We'll learn which approach is better over the next 3-5 years.

The Human Cost and Organizational Challenge

Building and maintaining gigawatt-scale infrastructure requires people. Thousands of them. Engineers, technicians, operations staff, supply chain specialists, facility managers, and more.

Meta is betting that it can attract and retain the talent needed. This requires competitive compensation, interesting work, and institutional support for growth. It's not guaranteed. The best infrastructure engineers have options. If the work is too political, the strategy fails, or the culture is wrong, they leave.

There's also an organizational culture question. Infrastructure is unglamorous. It doesn't produce the customer-facing products that get press coverage. It's easy for infrastructure work to feel like it's always in crisis mode, always fighting fires, always underfunded relative to product teams.

Structurally, putting Meta Compute at the top level (reporting to Zuckerberg) helps. It signals that infrastructure isn't second-class. It's central. This helps with culture and retention.

But the fundamental tension remains: AI researchers want to iterate quickly and try new ideas. Infrastructure operators want stability and careful planning. These incentives conflict. Organizations that manage the tension well win. Those that don't are torn apart by internal conflict.

Meta seems aware of this—hence the explicit separation between Meta Compute's planning and execution divisions. It's an attempt to acknowledge that different teams need different approaches.

The Path Forward for Meta

Meta's next 5 years will be defined by how well Meta Compute executes.

If it succeeds, Meta becomes an infrastructure powerhouse. The company's AI products become faster, cheaper, and better than competitors. Meta's margins improve because it's not paying cloud providers—it's operating its own infrastructure. The company's strategic autonomy increases because it controls its own destiny.

If it fails, Meta is saddled with billions in infrastructure costs and doesn't have the product revenue to justify them. Competitors might have picked better technology choices. Meta might have built in locations that became less favorable. The organizational complexity might have slowed innovation. The company would have to recognize losses and write off capital.

The outcome is genuinely uncertain. But the fact that Meta is making the bet shows it believes the upside justifies the risk. The company that can build and operate the most efficient, largest-scale AI infrastructure will likely dominate the AI era. Meta is betting it can be that company.

FAQ

What exactly is Meta Compute?

Meta Compute is a new top-level organizational division within Meta that consolidates AI infrastructure planning, hardware design, software development, networking, and facilities management. It operates at the CEO level, reporting directly to Mark Zuckerberg, and separates long-term capacity planning from day-to-day data center operations to ensure coordinated decision-making across all infrastructure concerns.

How much computing power is Meta planning to build?

Meta plans to deploy tens of gigawatts of computing capacity during the 2020s, with expectations to scale into hundreds of gigawatts or more over subsequent decades. A single gigawatt provides enough power for roughly 750,000 homes, putting into perspective the massive scale of Meta's infrastructure ambitions.

Why did Meta reorganize its infrastructure under Meta Compute?

Meta reorganized infrastructure to address coordination problems that arise at gigawatt scale. Traditional structures separate software teams from hardware teams, facilities from design, and strategy from operations. This works for incremental growth, but AI infrastructure demands tight integration between all these domains because decisions in one area cascade through all others, affecting power consumption, cooling requirements, real estate needs, and supply chain complexity.

What is Daniel Gross's role in Meta Compute?

Daniel Gross oversees long-term strategic planning at Meta Compute, including defining future compute requirements, building supply chains capable of delivering hardware at multi-gigawatt scales, and developing planning models that account for technological trends, industry dynamics, and resource constraints. He focuses on what Meta will need in five to ten years, not what's required today.

What is Santosh Janardhan's role in Meta Compute?

Santosh Janardhan handles execution and operations at Meta Compute, including system architecture design, in-house silicon development, software optimization layers, and management of Meta's global data center fleet. His focus is on making existing infrastructure work optimally and bringing new capacity online efficiently.

Why is power such a critical constraint for AI infrastructure?

High-end GPUs like NVIDIA's H100 consume 700 watts each. A modest data center with 10,000 GPUs requires 10-15 megawatts of total power including cooling and auxiliary systems. Utilities need years to upgrade transmission lines, build new power generation, or secure long-term contracts. Power is finite and requires cooperation from external stakeholders, making it the true limiting factor rather than GPU availability.

How does Meta's custom silicon strategy provide advantages?

Meta designs custom chips optimized specifically for its workloads rather than relying entirely on NVIDIA's general-purpose GPUs. Custom silicon can be tailored for Meta's specific memory bandwidth requirements, common AI operations, power efficiency needs, and network interfaces. A 30% improvement in power efficiency across gigawatt-scale infrastructure translates to hundreds of millions in annual operating cost savings.

What makes coordinating software and hardware teams so important?

Traditional separation of software and hardware teams creates inefficiencies. If software engineers discover that certain operations would be 10x faster with custom hardware support, it takes months to communicate this to chip designers under old structures. Co-locating these teams under Meta Compute enables rapid iteration, ensures hardware matches software requirements, and eliminates waste from misaligned priorities.

How does Meta plan to secure reliable power for gigawatt-scale infrastructure?

Meta prioritizes locations with abundant power sources like hydroelectric power in Iceland and Norway, geothermal capacity in certain U.S. regions, or access to nuclear power. The company negotiates long-term power contracts with utilities, may invest in dedicated power plants for its use, and strategically diversifies geographic locations to reduce dependence on any single power source or region.

What are the biggest risks to Meta's gigawatt-scale infrastructure plans?

Major risks include technological obsolescence (new AI techniques or chip architectures rendering current infrastructure suboptimal), cost overruns from construction complexity, demand shortfalls if Meta's AI products don't need the capacity, regulatory changes restricting AI or data centers, geopolitical tensions limiting international expansion, and power grid instability in critical regions. Meta addresses these through diversification, staged investment, constant re-evaluation, and supply chain redundancy.

How does Meta Compute compare to how Google and Microsoft handle infrastructure?

Google integrated infrastructure from the beginning due to Search requirements and built custom chips (TPUs) early, but may not have a single unified division like Meta Compute. Microsoft relies more on partnerships with OpenAI and cloud services rather than pure internal development. OpenAI outsources infrastructure to Microsoft's cloud entirely. Meta's approach of vertical integration is a distinct bet that controlling all layers provides advantages others don't achieve through partnerships or outsourcing.

Meta Compute represents a fundamental shift in how the company views AI. It's no longer a software problem to be solved by clever engineers. It's an infrastructure problem that requires decades of planning, billions in capital, and seamless integration across every technical domain. The organization reflects this reality. By centralizing infrastructure under one top-level division, Meta is saying: this matters. This is core. This is how we compete.

The next few years will test whether the bet pays off. If Meta can build gigawatt-scale capacity efficiently, run it reliably, and translate it into AI products that outcompete Google and OpenAI, the strategy will be vindicated. Competitors will follow. The AI race becomes an infrastructure race.

If the bet fails—if custom silicon lags NVIDIA's, if data centers cost more to operate than competitors', if AI products never materialize to justify the spend—then Meta has made an expensive mistake. It would be a cautionary tale about the limits of vertical integration.

But the company is making the bet anyway. That tells you something about how seriously Meta takes AI and how confident it is that infrastructure is the path to dominance in the decades ahead.

Key Takeaways

- Meta Compute reorganizes infrastructure to unify hardware, software, networking, and facilities under a single top-level division reporting to CEO Mark Zuckerberg, addressing coordination problems that emerge at gigawatt scale

- Power is the true limiting factor for AI infrastructure expansion, not GPU availability; securing reliable, affordable electricity through long-term utility contracts and renewable sources is essential for Meta's multi-gigawatt plans

- Dual leadership model separates execution (Santosh Janardhan handling current operations and custom silicon) from vision (Daniel Gross planning future requirements and building supply chains) to balance today's efficiency with tomorrow's innovation

- Custom silicon provides significant competitive advantages through power efficiency, workload optimization, and strategic autonomy, but requires extraordinary engineering investment and carries technology obsolescence risks

- Building hundreds of billions in infrastructure over decades is a high-stakes bet that AI will remain a core business driver; failure would represent an expensive strategic miscalculation, while success would provide unmatched competitive advantages

Related Articles

- OpenAI's $10B Cerebras Deal: What It Means for AI Compute [2025]

- AI's Real Bottleneck: Why Storage, Not GPUs, Limits AI Models [2025]

- MSI's AI and Business Focus at CES 2026 [2025]

- Skild AI Hits $14B Valuation: Robotics Foundation Models Explained [2025]

- VoiceRun's $5.5M Funding: Building the Voice Agent Factory [2025]

- Meta's Reality Labs Layoffs: What It Means for VR and the Metaverse [2025]

![Meta Compute: The AI Infrastructure Strategy Reshaping Gigawatt-Scale Operations [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-compute-the-ai-infrastructure-strategy-reshaping-gigawa/image-1-1768441062843.jpg)