Paramount Skydance's Lawsuit Against Warner Bros. Discovery: The Biggest Media Merger Battle of 2025

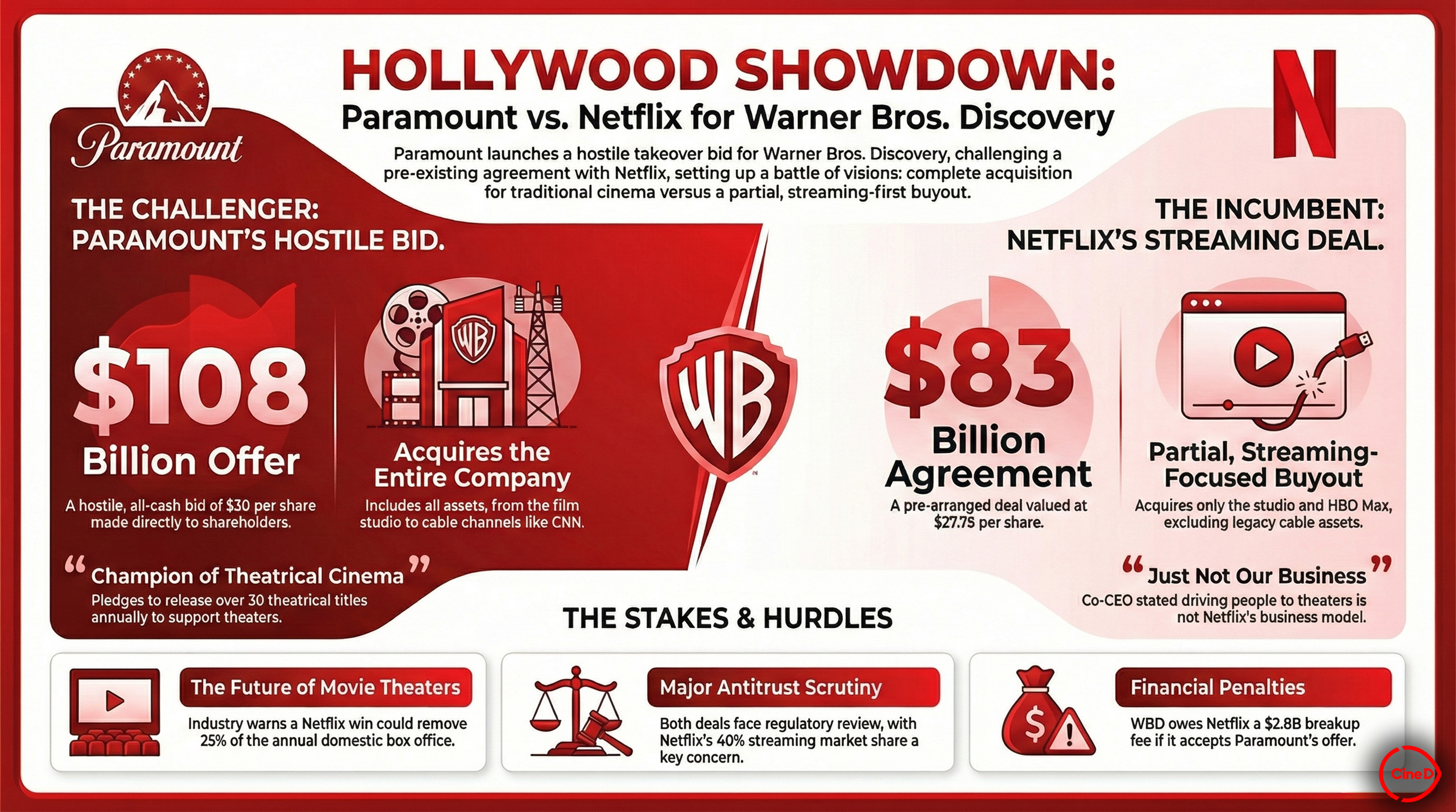

When Paramount CEO David Ellison announced the company wouldn't accept rejection, he wasn't bluffing. After multiple acquisition bids to Warner Bros. Discovery (WBD) got turned down flat, Paramount did something most companies only threaten: they lawyered up and filed suit. This isn't a standard corporate dispute that disappears after angry earnings calls. This is a genuine legal and financial war over the future of two media giants, and it's reshaping how we think about hostile takeovers in the streaming era.

The story starts with ambition. Paramount saw an opportunity to acquire WBD, believing the combined entity would create a media powerhouse capable of competing with Netflix and Disney+ at scale. But WBD's board had other plans. They rejected Paramount's offers, then doubled down by accepting a deal with Netflix instead. Netflix would acquire WBD's core entertainment business, while a newly spun-out Discovery Global would become its own publicly traded company. From Paramount's perspective, this decision was fundamentally flawed—and they decided to prove it in court.

What makes this battle fascinating isn't just the money. It's the chess game beneath the surface. Paramount is arguing that WBD shareholders never had the full picture. The company claims WBD hasn't disclosed how it actually valued the Discovery Global spinout, whether the Netflix deal will actually close, or how the board arrived at its recommendation. These aren't minor procedural complaints. They're core questions about whether WBD's shareholders got a fair shot at evaluating competing offers.

Paramount filed suit in Delaware Chancery Court, the most famous venue for corporate disputes in America. Delaware courts handle roughly 80% of Fortune 500 litigation. Filing there means Paramount is playing for keeps, using the most sophisticated legal infrastructure available. They're not just complaining to media outlets. They're forcing WBD to justify its decisions under oath, with unlimited discovery rights. That matters enormously when you're trying to prove the board made bad decisions.

The company also launched a proxy fight, meaning they're directly appealing to WBD shareholders to elect new board members who would be willing to negotiate. Proxy fights are expensive, require sophisticated investor relations campaigns, and often fail. But when they work, they can flip an entire board's composition. Paramount is betting they can convince enough shareholders that their offer is genuinely superior.

Here's what makes this different from typical M&A disputes: both sides have compelling arguments. WBD's board points to Paramount's debt burden, execution risk, and uncertain financing. Paramount argues the Netflix deal is actually riskier because it relies on a third party and leaves shareholders with a fractured company. Neither side is obviously wrong, which is why this case will probably drag on for months.

The lawsuit reveals something deeper about modern media: nobody's happy. Paramount wants bigger scale. WBD preferred a Netflix partnership. Netflix wanted entertainment assets without the management complexity. The shareholders just want clarity on which option actually makes them money. This lawsuit forces all those competing interests to hash it out in the legal system instead of boardrooms.

The Original Paramount Bids: What WBD Rejected

Paramount's initial approach wasn't hostile. They came with what they believed was a compelling offer: combine the two companies, eliminate redundant costs, and emerge as a leaner, more focused competitor. The proposed deal would have given WBD shareholders equity in the combined entity, along with a premium to the stock price at the time of announcement.

The first bid came in quietly, through private conversations between executives and board advisors. WBD's board listened, asked questions, and then said no. The stated reason was that Paramount's offer didn't provide sufficient value and didn't adequately address debt concerns. WBD worried about the "financial engineering" required to make a Paramount combination work. Specifically, they questioned whether Paramount could actually raise the necessary capital and pull off integration without stumbling.

Paramount came back with a revised bid. They increased the offer price, adjusted the payment structure, and tried to address WBD's specific concerns about debt and closing certainty. The board rejected this too. At this point, WBD had already begun deeper conversations with Netflix. Those talks appeared to be moving faster and hitting fewer obstacles. Netflix had clean financing—they could pay in cash or stock easily. Netflix already had streaming expertise and didn't need to integrate traditional cable assets. From WBD's board perspective, Netflix represented a faster, cleaner path.

Paramount, frustrated by rejection, made what they called their "best and final" bid. It was hostile now, meaning they went around the WBD board directly to shareholders. This hostile bid included improved financial terms and a binding commitment from a major lender that they could actually execute the deal. The board recommended shareholders reject this offer. They said Paramount was still undervaluing the company and that execution risk remained too high.

What's striking about WBD's rejections is they weren't clearly wrong. Paramount was proposing a risky integration of two massive, overlapping companies. Success would have required flawless execution and favorable financing conditions. One missed quarter or one financing snag could have tanked the whole thing. WBD's concerns were legitimate from a fiduciary duty perspective.

But that's also where Paramount's lawsuit becomes powerful. The board rejected Paramount's bids, then immediately accepted Netflix's offer. Netflix's deal is not obviously superior on paper. Netflix is acquiring WBD, sure, but leaving Discovery Global to fend for itself. That spinout company will have to operate independently, without WBD's traditional cable revenue or Disney's theme park licensing deals. Paramount's offer would have kept those assets together, creating a fully integrated media company.

The timing is suspicious to Paramount's lawyers. The board seems to have made a predetermined decision to go with Netflix, then rejected Paramount's bids without seriously engaging on the specific deficiencies. This is exactly what the lawsuit is trying to prove: that the process was rigged, not open, and that shareholders never got real alternatives to consider.

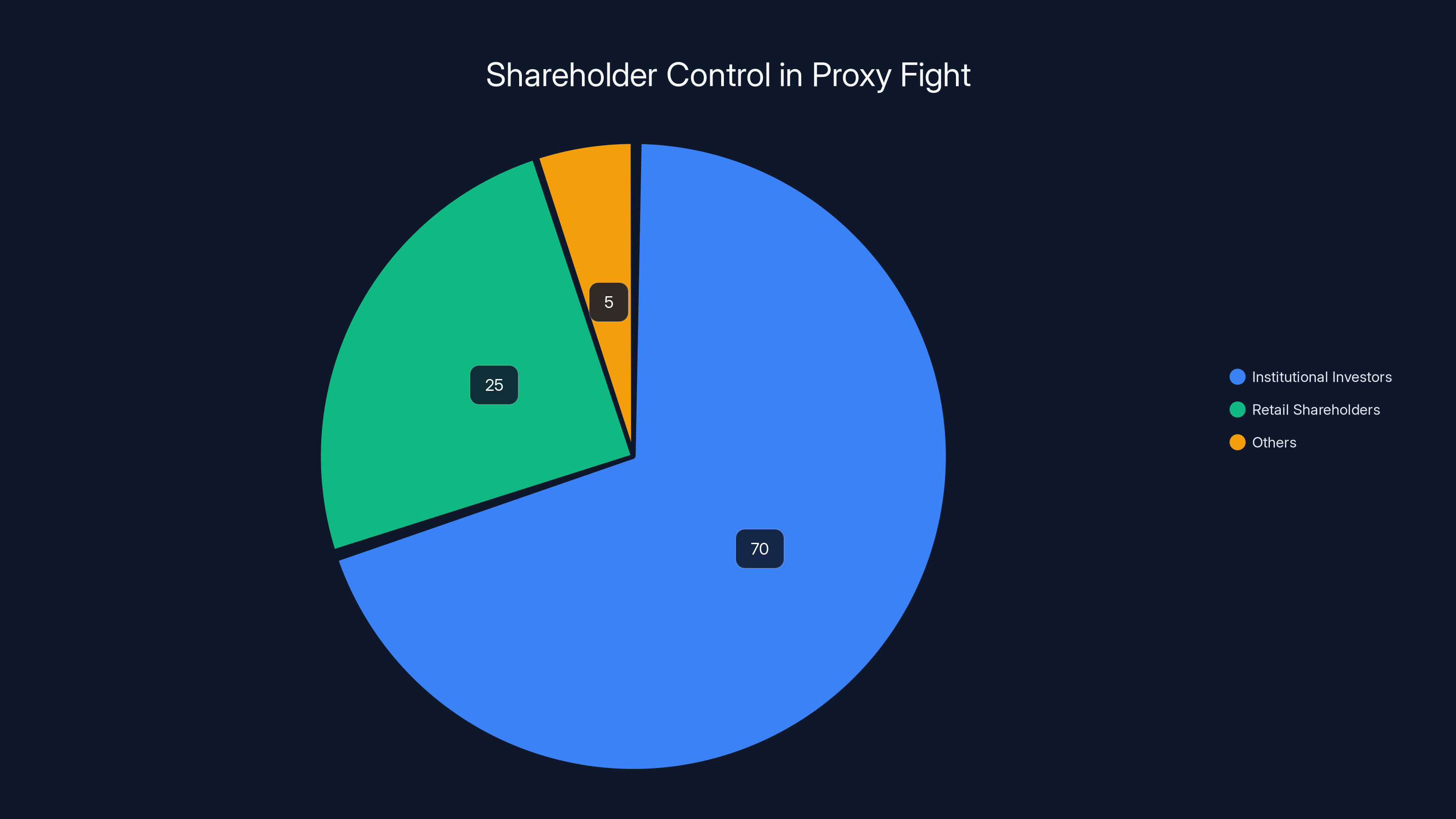

Institutional investors control approximately 70% of WBD shares, making them crucial in the proxy fight. Estimated data.

The Netflix Deal: Why WBD's Board Chose a Different Path

Understanding WBD's decision requires understanding the Netflix opportunity. Netflix wasn't just another buyer. Netflix came with something Paramount couldn't offer: proven streaming dominance, massive subscriber bases, and intimate knowledge of the global entertainment market. Netflix also came with uncomplicated financing and no integration risk. Netflix already knew how to run content businesses at scale.

WBD's board likely thought about this calculation: Netflix handles streaming distribution. Discovery Global handles traditional cable networks and content production. The two don't need to be merged to work together. Netflix could license content from Discovery Global. Discovery Global could distribute on Netflix. They could work as partners rather than a unified company.

This is appealing from a strategic perspective. It preserves Discovery Global as an independent entity while giving it Netflix's resources and distribution power. Netflix gets entertainment content and libraries. WBD shareholders get cash now and equity in Discovery Global later. It's elegant, assuming everything works.

The Netflix deal also comes with fewer regulatory risks. Paramount acquiring WBD would create a company with massive traditional cable footprint, streaming scale, and international reach. Regulators might block it on competition grounds. Netflix already exists as an independent company. Netflix acquiring entertainment assets from WBD looks like market consolidation but not necessarily a new monopoly threat.

WBD's board also valued speed. Netflix could close a deal faster than Paramount could arrange financing and plan an integration. In media, speed matters because content libraries depreciate and subscriber relationships shift. Getting the deal done this quarter rather than next quarter could be worth millions in streaming metrics.

But WBD's board may have underestimated Paramount's legal leverage. Paramount's complaint focuses on process, not valuation. Paramount isn't saying "we know Netflix's offer is worth less." They're saying "WBD didn't tell shareholders how it valued the assets at stake." That's a process argument, and Delaware courts care deeply about process. If Paramount can prove the board didn't give shareholders enough information, the court could require a new vote or even allow Paramount's bid to be reconsidered.

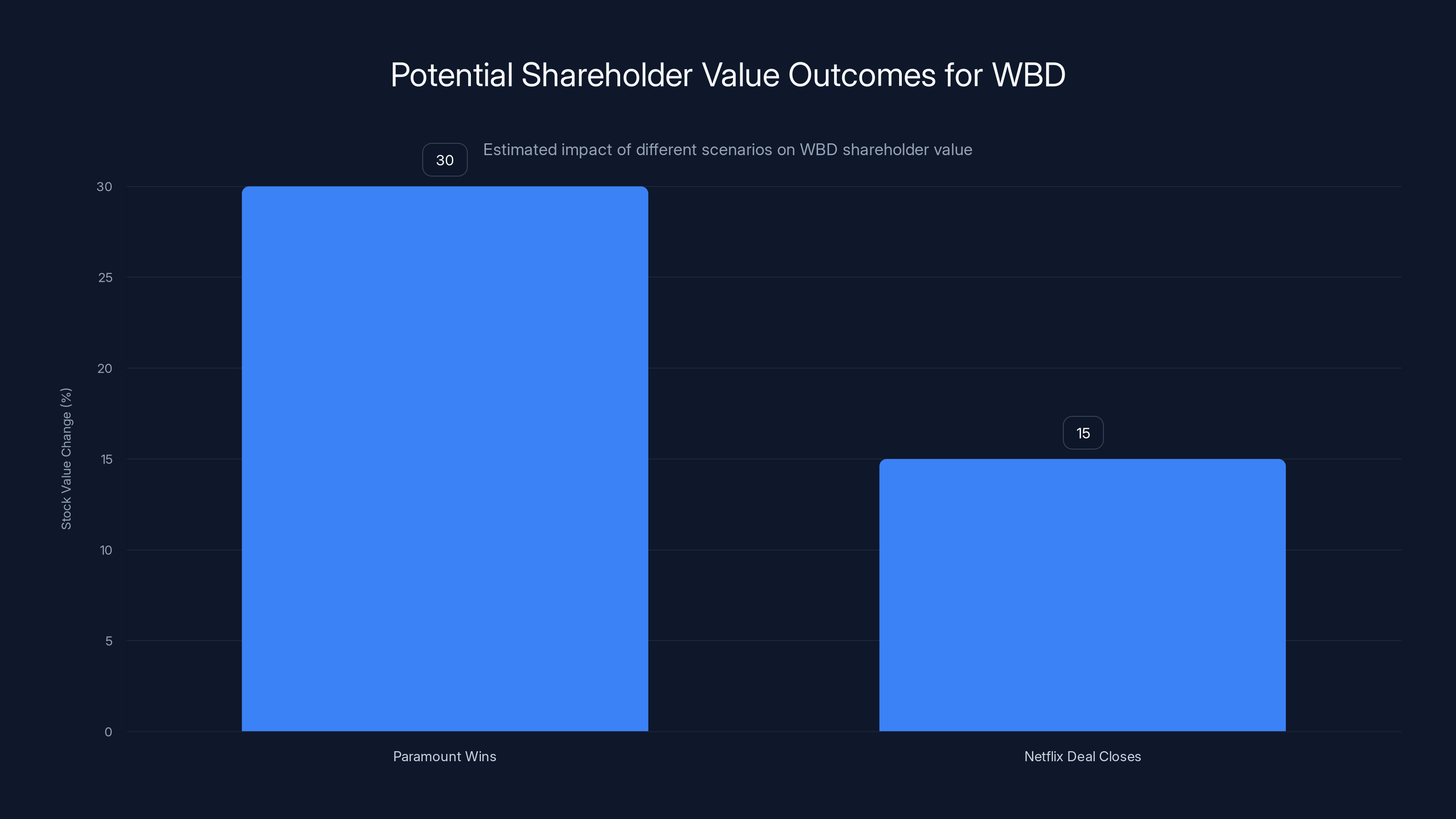

Estimated data: If Paramount wins, WBD shareholders could see a 20-40% increase in stock value over 3-5 years. If the Netflix deal closes, the increase might be around 15%, depending on deal specifics.

The Delaware Chancery Court Lawsuit: Legal Arguments and Discovery

Paramount filed suit in Delaware Chancery Court on specific grounds: breach of fiduciary duty, failure to make adequate disclosure, and violation of the merger agreement's terms regarding board conduct. These are technical allegations, but they're powerful ones.

The core claim is that WBD's board had a fiduciary duty to shareholders to get the best possible deal. The board also had a contractual obligation (in the WBD-Netflix merger agreement) to provide shareholders with information needed to evaluate that deal against alternatives. Paramount argues the board failed both duties by not disclosing how they valued Discovery Global and by not seriously engaging with Paramount's improved bids.

Discovery will be the real battleground. Paramount's lawyers can demand all internal WBD communications, board meeting notes, financial models, and fairness opinions. They can depose board members, executives, and financial advisors. Netflix's lawyers get involved too because Paramount's claims touch the Netflix deal's validity. This discovery process will likely reveal exactly how WBD's board made its decisions and what information they considered.

WBD will argue they acted reasonably. They evaluated Paramount's bids using independent financial advisors. They considered execution risk and financing uncertainty. They believed Netflix's offer was superior given all factors. These are legitimate board processes. WBD will argue that disagreement about deal value doesn't constitute breach of duty. The board was allowed to prefer Netflix's offer, even if Paramount's offer had some theoretical advantages.

The disclosure issue is subtler. Paramount isn't saying WBD lied to shareholders. They're saying WBD didn't provide enough information about how certain assets were valued. Specifically, Discovery Global's value. If Discovery Global is worth

Delaware courts historically support full disclosure. Judges often rule that when shareholders vote on a deal, they need comprehensive information. If material information was withheld, courts can unwind votes or require new ones. This gives Paramount a real chance of forcing supplemental disclosures at minimum.

The merger agreement with Netflix probably includes a termination fee and various covenants about how WBD's board should conduct itself. If the court finds WBD breached those terms by not adequately disclosing information, Netflix could face liability, or WBD could face specific performance orders to comply with disclosure requirements. This creates incentive for Netflix to pressure WBD to settle with Paramount rather than risk the agreement being invalidated.

Paramount's legal strategy here is sophisticated. They're not trying to prove Netflix's offer is worse (which would be hard). They're trying to prove the process was flawed. If the process is flawed enough, shareholders get another chance to evaluate. And if shareholders get another chance with better information, Paramount believes they'll choose Paramount's offer.

The Proxy Fight Strategy: Board Nominations and Shareholder Pressure

Suing is necessary but not sufficient for Paramount's strategy. They also need to win over shareholders directly. The proxy fight is that mechanism. Paramount nominated a slate of directors for WBD's 2026 annual meeting, promising these directors would be open to negotiating with Paramount.

Proxy fights work by appealing to shareholders' financial interests. Paramount's argument to shareholders is straightforward: "Your current board rejected an offer we believe is superior. We want to replace board members with people willing to seriously consider our proposal." If Paramount can get its slate elected, WBD's entire board composition changes. Paramount could then negotiate as a peer rather than a hostile outsider.

Winning a proxy fight requires extensive shareholder outreach. Paramount must contact major institutional shareholders, explain their case, and secure proxy votes. Institutional investors (pension funds, mutual funds, hedge funds) control roughly 70% of WBD shares. If Paramount can convert these institutions to their side, they can win even if most retail shareholders oppose them.

Paramount's pitch to institutions likely emphasizes financial returns. They'll argue the combined Paramount-WBD entity would have greater valuation than WBD alone plus Discovery Global as a separate company. They'll argue execution risk is manageable given Paramount's operational expertise. They'll highlight cost synergies and scale benefits that Netflix's deal doesn't capture.

WBD's board will counter with their own proxy campaign. They'll tell shareholders the Netflix deal is locked in, offers certainty, and involves less risk than a Paramount combination. They'll question Paramount's financing and execution capability. They'll emphasize that Netflix's resources and distribution give WBD assets better prospects than going independent or merging with Paramount.

Proxy fights are brutally expensive. Both sides might spend $30-50 million on lawyers, advisors, and shareholder communications. But the stakes justify the cost. A successful proxy fight could deliver a multi-billion-dollar company into Paramount's hands. A failed proxy fight costs money but doesn't change the outcome. So both sides will likely go all-in.

Paramount also demanded a bylaw change requiring shareholder approval for any Discovery Global separation. This is clever pressure. It says to shareholders: "Before WBD spins off Discovery Global, you need to vote again. You'll have a chance to reconsider whether separating these assets makes sense compared to Paramount's offer." This protects Paramount's position if they win the proxy fight, because even a Paramount-friendly board can't immediately merge with WBD without shareholder approval.

The proxy fight also creates leverage for settlement negotiations. WBD's board faces pressure from two directions: they could lose the proxy fight and be replaced, or they could settle with Paramount on improved terms. Sometimes facing serious proxy fight pressure, boards choose to negotiate rather than fight to the end. Paramount is banking on exactly that scenario.

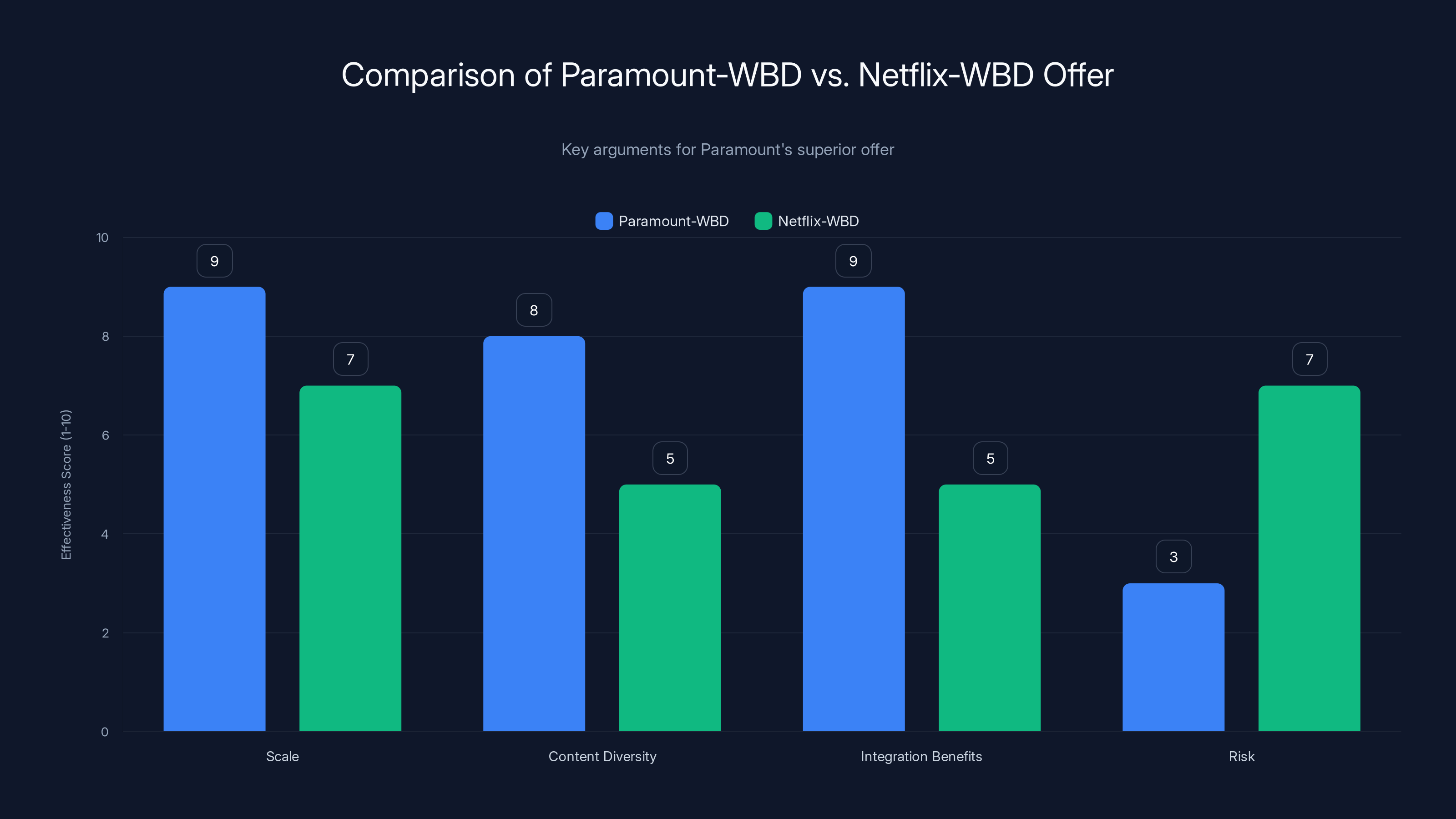

Paramount-WBD offers superior scale, content diversity, and integration benefits with lower risk compared to Netflix-WBD. Estimated data based on qualitative analysis.

Discovery Global: The Spinout Company at the Center of the Fight

Discovery Global is the real prize in this dispute. It's not one company but a collection of assets: traditional cable networks like HGTV, Food Network, TLC, Animal Planet, and others. It also includes Max and other digital properties. Critically, it's profitable, generative of cash flow, and independent from Netflix's streaming model.

WBD's Netflix deal spins out Discovery Global as its own public company. The assumption is Discovery Global will become a mid-cap media company, probably valued in the $10-15 billion range, and will operate independently or potentially as a Netflix affiliate. Shareholders would own both WBD entertainment assets (being acquired by Netflix) and Discovery Global shares separately.

Paramount's offer keeps Discovery Global within the combined company. This means all the cable networks, streaming apps, and content libraries would operate as one unit under Paramount's leadership. From Paramount's perspective, this is superior because it preserves the value of traditional cable networks. Cable networks still generate meaningful cash flow and have loyal audiences. They're not as cool as Netflix, but they work.

The disagreement hinges on asset values. If Discovery Global is worth

Paramount's lawsuit specifically demands disclosure of how WBD valued Discovery Global. This isn't random nitpicking. Valuation directly determines whether shareholders should prefer Netflix or Paramount. Paramount wants shareholders to see the valuation assumptions, because they believe the assumptions are too optimistic. They believe Discovery Global's independent value is overstated.

There's also a strategic angle. Cable networks are struggling in the streaming era. Their traditional advertising bases are declining. Their subscriber bases are aging. A spinout Discovery Global would face serious headwinds: shrinking cable advertising, cord-cutting pressures, and dependence on relatively dated content franchises. Whether shareholders understand these headwinds depends on what information WBD discloses about Discovery Global's prospects.

Paramount's argument is that combining with them gives Discovery Global better prospects. Paramount has experience with traditional media, relationships with distributors, and content production capabilities. Paramount could help Discovery Global adapt. Netflix, by contrast, might not care about Discovery Global's long-term success as long as Netflix gets the entertainment assets it wants.

This is where Paramount's legal strategy gets clever. They're not just asking for valuation numbers. They're asking for the assumptions behind those valuations, the sensitivity analyses showing how changes affect value, and the board's own assessment of Discovery Global's competitive position. If the board didn't do proper analysis, or if assumptions are unreasonable, courts might order a new valuation or give shareholders another chance to vote.

Paramount's Core Argument: Why Their Offer is Superior

Paramount's fundamental argument is that combining Paramount and WBD creates a better company than Netflix's plan does. Let's break down their reasoning, because it's more sophisticated than "we're bigger so you should combine with us."

First, Paramount argues scale. Combined, Paramount and WBD would represent the third-largest media company globally (after Netflix and Disney). This scale enables better negotiations with distributors, better leverage with advertisers, and lower per-unit costs for content production. Scale also provides financial cushion for investing in new markets and experimenting with new formats.

Second, Paramount emphasizes content diversity. Paramount owns movie studios, television networks, and streaming platforms. Adding WBD's cable networks and content libraries creates a company with unmatched diversity: premium theatrical films, episodic TV content, documentary programming, news operations, international channels, and more. Netflix, by contrast, is primarily streaming-focused. Netflix's deal leaves Netflix focused on entertainment at scale but leaves WBD's traditional assets to fend for themselves.

Third, Paramount argues integration benefits. Paramount knows how to integrate acquisitions. They've successfully combined CBS and Viacom. They've integrated various smaller properties. They have systems, processes, and experienced executives for managing complex media companies. The Paramount-WBD combination would eliminate duplicate corporate functions, consolidate technology stacks, and streamline content planning. Paramount estimates savings of $3-5 billion annually, though these estimates haven't been independently verified.

Fourth, Paramount argues that Netflix's deal is actually riskier. Netflix acquiring WBD depends on Netflix (a third party) closing the deal, navigating regulatory review, and executing integration. If Netflix walks away, WBD is left in limbo. If Netflix faces regulatory obstacles, the whole deal is delayed. Netflix also has its own priorities (subscriber growth, profit margins, content strategy), which might not align with WBD asset interests. Paramount, as an insider in the media industry, faces fewer external obstacles.

Fifth, Paramount emphasizes shareholder value. WBD shareholders would own equity in the combined Paramount-WBD entity and benefit from its superior operational performance. They'd also benefit directly from the $3-5 billion in annual synergies Paramount projects. Netflix's deal gives shareholders cash now but separates them from WBD's most valuable assets (which go into the Netflix deal) and leaves them with only Discovery Global equity.

Paramount also argues that preserving WBD's integrated structure protects shareholder value. Spinning out Discovery Global creates two mid-cap companies where one large company existed before. Mid-cap companies trade at lower valuations per dollar of earnings than large-cap companies (this is the "conglomerate discount"). By avoiding the spinout, Paramount's plan preserves valuation multiples and protects shareholder economics.

These are reasoned, sophisticated arguments. They're not obviously correct (which is why smart people disagree), but they're not baseless either. A board could legitimately prefer Paramount's offer on these merits. Or a board could prefer Netflix's offer because of execution risk, financing uncertainty, or strategic fit. The point is shareholders deserve to evaluate both, with full information, to reach their own conclusions.

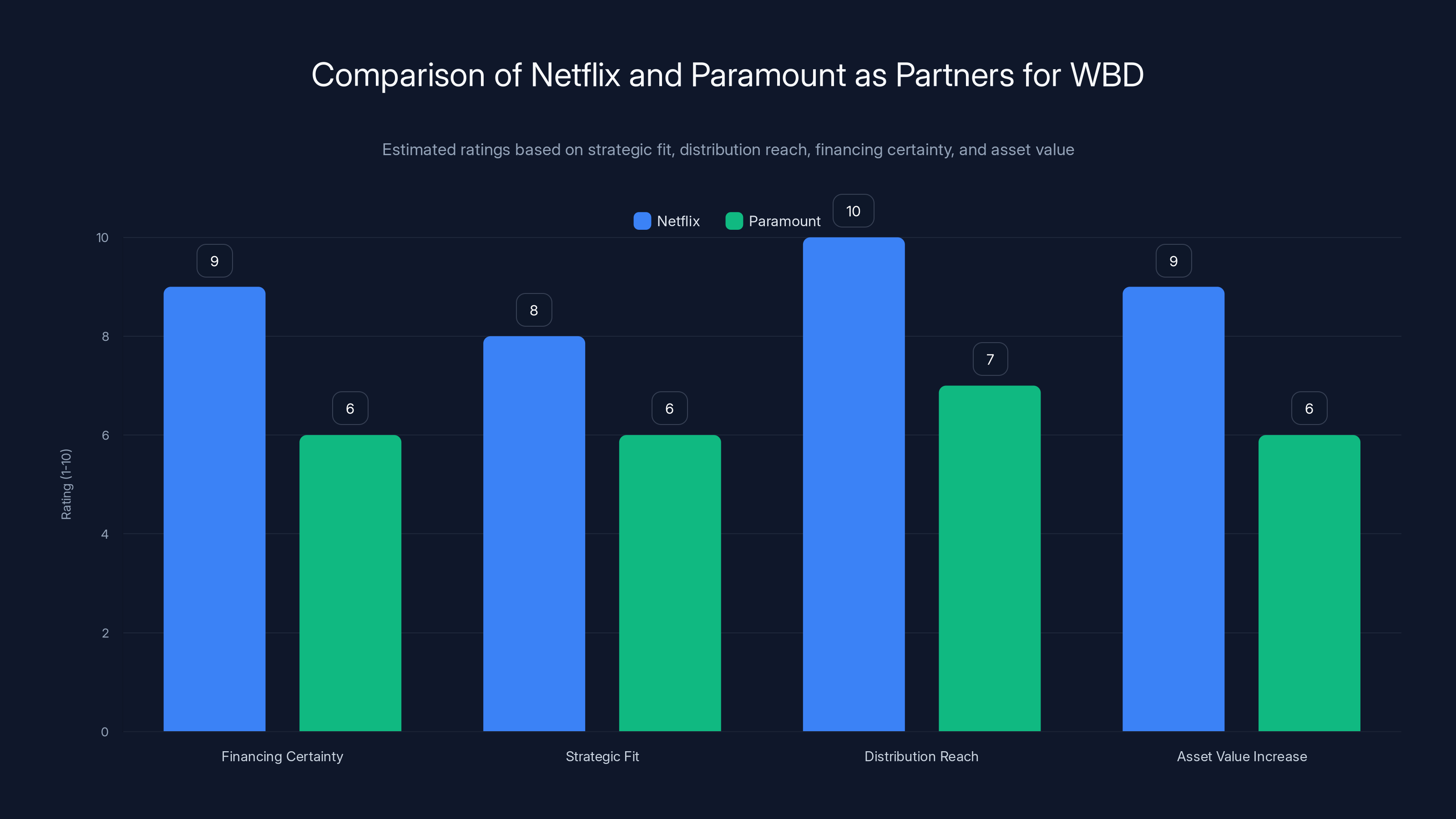

Netflix scores higher across all criteria, making it a superior partner for WBD. Estimated data based on qualitative analysis.

WBD's Counter-Argument: Why Netflix is the Superior Partner

WBD's board has equally sophisticated reasons for preferring Netflix. Understanding their reasoning is crucial to evaluating who's actually right.

First, WBD argues that Netflix brings certainty. Netflix has a committed financing package. Netflix doesn't need to raise debt from banks or private equity firms. Netflix can close the deal quickly without regulatory uncertainties that plague larger mergers. Paramount's offer, by contrast, requires Paramount to arrange financing, which takes time, faces interest rate risk, and could fall apart if financing conditions change.

Second, WBD emphasizes strategic fit. Netflix needs entertainment content and library assets. WBD has exactly those things. The combination is logical: Netflix handles distribution, WBD's entertainment division handles content. This is cleaner than a Paramount combination, which would require integrating overlapping distribution systems and duplicate content production capabilities.

Third, WBD argues that Netflix's ownership increases WBD assets' value, not decreases it. Netflix has massive subscriber relationships, proven monetization models, and global distribution. WBD's entertainment content distributed through Netflix's platform reaches 250+ million subscribers. That reach is valuable. Paramount's distribution, while substantial, is smaller and less efficient than Netflix's. WBD assets probably reach more customers and generate more value under Netflix's ownership than under Paramount's.

Fourth, WBD emphasizes that preserving Discovery Global as independent is valuable. Discovery Global's cable networks serve specific, loyal audiences. Their content (cooking, home improvement, nature documentaries) appeals to demographics that don't necessarily want Netflix's prestige dramas or action blockbusters. Keeping Discovery Global independent lets it optimize for its audiences without being pressure-tested against Netflix's metrics. Combining with Paramount might force these networks toward Paramount's content strategy, which could alienate existing audiences.

Fifth, WBD argues Paramount's synergy estimates are aggressive and uncertain. Paramount projects $3-5 billion in annual savings, but these projections depend on integration succeeding perfectly. Media integrations often disappoint. Cost savings are harder to realize than projected. Revenue synergies rarely materialize. WBD shareholders could end up with less value if Paramount's projections prove optimistic. Netflix's deal, by contrast, doesn't depend on magical synergies. It's straightforward: Netflix acquires entertainment content, Discovery Global operates independently.

Sixth, WBD likely argues that Paramount's leverage requirements are concerning. Paramount would need to borrow heavily to finance a WBD acquisition. This increases debt service costs and financial risk. If Paramount's operations underperform or economic conditions worsen, the debt burden could become unsustainable. WBD shareholders would bear that risk. Netflix's all-cash (or all-stock) offer avoids this leverage risk.

WBD also emphasizes execution risk. Paramount would need to integrate two massive companies while managing content pipelines, technology systems, and hundreds of thousands of employees. This is hard. It goes wrong frequently. Netflix's deal, by contrast, requires less integration. Netflix can largely operate WBD's entertainment division as is, with management changes at the top. Less integration means fewer things can go wrong.

Finally, WBD probably emphasizes regulatory risk. A Paramount-WBD combination creates a company with enormous reach across theatrical, television, streaming, cable, and international markets. Regulators might view this as threatening competition. Netflix acquiring WBD is less likely to trigger major regulatory objections because Netflix already exists as an independent entity and the acquisition strengthens its content library rather than creating a new dominant player.

These arguments are also sophisticated and reasonable. Boards facing this choice could legitimately prefer Netflix's offer based on risk management, strategic clarity, and financing certainty.

The Financing Challenge: Paramount's Debt Burden

Here's where the real divide emerges between the two offers. Paramount's offer requires substantial leverage. Paramount would need to borrow $15-20 billion (estimates vary based on deal structure) to finance an acquisition of WBD. This debt would sit on the combined company's balance sheet, increasing financial risk and limiting strategic flexibility.

WBD's board raised this specifically in their rejections. They asked Paramount to prove they could actually finance the deal at reasonable rates. Paramount provided a financing commitment letter from a major lender, but financing commitment letters come with conditions. If markets deteriorate, interest rates spike, or economic conditions worsen, the financing could fall apart. This scenario happened frequently during the 2008 financial crisis, when deals announced with committed financing collapsed when actual funding became unavailable.

Netflix's offer avoids this problem entirely. Netflix can fund a WBD acquisition from operating cash flow, borrowing (Netflix's credit rating is strong), or stock issuance (Netflix's stock is valuable). Netflix doesn't need to prove it can arrange "committed" financing from banks because Netflix can self-fund. This is a massive advantage for Netflix's offer.

Paramount's financing burden also raises operational questions. After borrowing $15-20 billion, the combined Paramount-WBD company would have debt-to-EBITDA ratios around 3-4x (depending on how costs are structured). This is manageable but leaves little room for error. If revenues decline, costs increase, or markets soften, the company could face covenant violations or forced asset sales.

This financial burden also constrains strategic flexibility. Instead of investing in new content, technology, or international expansion, the combined company would need to focus on debt repayment. Paramount executives would face pressure to cut costs and maximize cash generation rather than taking risks on experimental content or new markets.

WBD's board was right to be concerned about Paramount's leverage requirements. This isn't just theoretical risk. It's a genuine constraint on Paramount's offer's attractiveness. Paramount could potentially reduce leverage by offering fewer shares or less cash to WBD shareholders, but that would make their offer less financially attractive. So Paramount faces a genuine tension: high leverage makes the offer more valuable to WBD shareholders but more risky financially, while lower leverage makes the offer safer but less attractive to shareholders.

Paramount would need to borrow an estimated $15-20 billion, resulting in a debt-to-EBITDA ratio of around 3-4x, while Netflix can self-fund without additional debt. Estimated data.

Paramount's Legal Disclosure Claims: What Information is Actually Missing?

Paramount's lawsuit specifically alleges that WBD failed to provide shareholders with critical information needed to evaluate the Netflix deal versus Paramount's offer. Let's examine what information Paramount claims is missing and why it matters.

First, WBD's valuation of Discovery Global. If Discovery Global is worth

Second, WBD's internal financial projections for the businesses being acquired by Netflix. How much revenue does WBD project? What are margin expectations? What content spending is budgeted? Paramount's argument is that if WBD is projecting strong growth and high margins, Netflix's valuation might be leaving shareholder value on the table. If WBD is projecting decline, Netflix's deal might be appropriate. Shareholders deserve to see these projections.

Third, documentation of how WBD's board engaged (or didn't engage) with Paramount's improved bids. WBD's board rejected multiple Paramount offers. Did they seriously analyze each one? Did they understand Paramount's cost-saving arguments? Did they consider specific weaknesses in Paramount's proposals? Or did they dismiss Paramount's offers reflexively? Paramount wants to prove the process was flawed, and board meeting notes would reveal whether serious engagement happened.

Fourth, fairness opinions from financial advisors. When WBD's board decided to accept Netflix's offer, they hired financial advisors (probably Goldman Sachs or similar firms) to issue fairness opinions stating the deal price was fair. These fairness opinions rest on assumptions: what comparable companies are trading at, what discount rates are appropriate, what growth rates are realistic. Paramount wants to challenge these assumptions and see whether advisors adequately considered Paramount's offer.

Fifth, the specific terms of WBD's merger agreement with Netflix. What covenants does WBD have? What conditions could terminate the deal? What termination fees apply? Paramount's argument is that WBD shareholders should understand how locked-in the Netflix deal actually is. If termination is expensive or difficult, shareholders have less real choice. If termination is easy and inexpensive, shareholders have more optionality.

Sixth, regulatory risk assessment. Did WBD's advisors seriously evaluate whether Netflix's deal faces regulatory obstacles? Did they consider potential regulatory conditions or divestitures? Paramount wants shareholders to understand this risk. If Netflix's deal faces significant regulatory uncertainty, Paramount's offer might be more reliable even if it requires more leverage.

Paramount's disclosure argument essentially says: "Shareholders can't make an informed decision without seeing these materials. WBD's board is withholding information that shareholders need. Delaware law requires full disclosure, so we're asking the court to force it."

WBD's counter-argument will be that this information is confidential, that it's preliminary and subject to change, and that shareholders don't need every internal document to understand the Netflix deal's merits. WBD will probably argue that proxy statements already disclose all material information and that Paramount's demands for full internal files exceed what Delaware law actually requires.

The judge will ultimately decide whether shareholders need this additional information before voting. This is a genuinely close legal question. Historically, Delaware courts have required broad disclosure but haven't required companies to disclose every internal memo. The judge will balance shareholder interests (getting information to make good decisions) against companies' legitimate confidentiality interests.

Delaware Chancery Court Procedure and Timeline

Now let's discuss what actually happens in Delaware Chancery Court and what timeline to expect. Understanding procedure helps predict how the case will develop and what leverage each side has.

Delaware Chancery Court is specialized. Judges in Chancery Court handle only business law cases. They're experts in corporate governance, mergers, shareholder rights, and similar issues. This expertise is good news for both sides because the judge will understand complex financial and business arguments. It's bad news for whoever has the weaker legal claim because an expert judge can't be confused or persuaded by simplistic arguments.

The case will proceed in phases. First, Paramount will file their complaint and seek preliminary relief, probably including a preliminary injunction that would halt the Netflix deal or require additional shareholder disclosures. WBD will file a motion to dismiss, arguing that Paramount's claims don't state a legal claim for relief. These initial motions will probably happen within 60 days.

If the judge denies the motion to dismiss, the case proceeds to discovery. Discovery means both sides can demand documents from the other side and depose witnesses. Paramount will demand all WBD board materials, valuation analyses, and communications about the Netflix deal and Paramount's bids. WBD will demand Paramount's financing commitments, operational projections, and board materials about the proposed acquisition.

Discovery typically takes 4-6 months. During this period, both sides will develop evidence supporting their positions. Paramount will try to prove the board didn't seriously engage with Paramount's offers or that WBD's valuation assumptions are flawed. WBD will try to prove the board conducted a fair process and that Netflix's offer is genuinely superior.

After discovery, both sides will file summary judgment motions, arguing that the undisputed facts entitle them to win without going to trial. If the judge agrees with either side, the case ends. If not, the case proceeds toward trial.

Trial is unlikely because judges in Chancery Court can rule on law and facts without a jury. Most parties settle before trial because trial results are uncertain and expensive. The judge might indicate through preliminary rulings which way the case is heading, and that can motivate settlement negotiations.

Timeline-wise, expect this process to take 12-18 months minimum. The Netflix-WBD merger agreement probably includes provisions allowing the parties to delay shareholder vote if litigation is pending. So even if the Netflix deal is technically "approved," the actual closing might not happen while litigation is pending. This creates leverage for Paramount: WBD wants to resolve the lawsuit so the Netflix deal can close.

The judge also has power to order expedited procedures if shareholders need clarity before voting. If the judge believes shareholders should vote on the Netflix deal and need information to do so fairly, they might order expedited discovery and expedited trial to resolve the case quickly. This would compress the timeline but wouldn't eliminate it entirely.

Short-term risks are high due to litigation uncertainty, medium-term risks increase with potential leverage, while long-term risks depend on industry consolidation trends. (Estimated data)

Shareholder Implications: What This Means for WBD Holders

If you own WBD stock or are considering buying it, this lawsuit has major implications. Let's think through the scenarios and what they mean for shareholder value.

Scenario 1: Paramount Wins the Lawsuit and Proxy Fight

If Paramount succeeds in court and wins the proxy fight, WBD shareholders would end up with equity in the combined Paramount-WBD company. This combined company would be larger, potentially more efficient, and positioned differently in the market. Shareholder value would depend on whether Paramount actually executes the combination successfully and realizes promised synergies.

Historically, acquisitions destroy value 50% of the time or more. Paramount might overestimate synergies, overestimate cost savings, or struggle with integration. But if Paramount executes well, shareholders could realize significant value creation. The stock might rise 20-40% over 3-5 years post-integration if operations go well.

The downside is debt and execution risk. The combined company would carry heavy debt, limiting strategic flexibility. If revenues disappoint or costs increase, shareholders could face dilution or financial stress. Paramount's own performance matters: if Paramount is struggling operationally, adding WBD's assets might just create a bigger struggling company.

Scenario 2: Netflix Deal Closes as Planned

If WBD's board holds firm and the Netflix deal closes, shareholders end up with cash or Netflix stock (depending on deal structure) and shares in the spun-out Discovery Global company. This is the board's preferred outcome.

Value would depend on Netflix's payments, Discovery Global's independent viability, and how the market values Discovery Global as a standalone company. If Netflix overpays for WBD's assets and Discovery Global's cable networks remain profitable, shareholders do well. If Netflix underpays and Discovery Global faces secular decline, shareholders underperform.

Scenario 3: Paramount Wins in Court but Loses the Proxy Fight

If the Delaware judge rules that WBD didn't provide adequate disclosure but Paramount's proxy fight fails, shareholders might get supplemental information and another chance to vote, but the board composition doesn't change. The board remains opposed to Paramount.

This scenario is awkward. The judge has indicated the process was flawed, but shareholders elected to keep the existing board. The board might negotiate improved terms with Paramount (to avoid further litigation) or might simply push forward with Netflix. This scenario probably ends with WBD making additional disclosures and holding a new shareholder vote on the Netflix deal.

Scenario 4: Paramount Loses on the Merits

If the judge rules that WBD's board process was adequate and disclosures were sufficient, the Netflix deal probably proceeds. Paramount can appeal, but appeals take time. Eventually, the Netflix deal closes unless regulatory obstacles emerge.

In this scenario, WBD shareholders get the Netflix deal outcome. Paramount walks away empty-handed. Paramount's shareholders might be relieved (no debt and risk of failed integration) or disappointed (missed opportunity for a bigger company). Paramount would likely redirect its acquisition strategy toward smaller targets or pursue organic growth.

Investment Implications and Risk Management

If you own WBD shares or are considering an investment, think carefully about your risk tolerance and investment timeframe.

Short-term risk: Litigation uncertainty creates stock volatility. WBD shares might trade at a discount to the Netflix deal price while litigation is pending because there's a possibility Paramount wins. If risk-averse investors sell, the discount could be meaningful (5-15% is common in litigation situations). Risk-tolerant investors might view this as an opportunity. Conservative investors might want to avoid the uncertainty entirely.

Medium-term risk: If Paramount wins, WBD becomes part of a highly leveraged company. Leverage increases in bad economic times, which is when you least want financial stress. If a recession hits while the combined company is integrating, operational problems and financial stress could emerge simultaneously.

Long-term value: The real question is which deal structure creates more value over 5-10 years. If you believe streaming will consolidate further (Netflix, Disney, a few others), combining Paramount with WBD makes sense because scale and content diversity matter. If you believe specialized media (cable networks, documentary programming, international channels) can prosper independently, the Netflix deal with an independent Discovery Global might be better.

Neither outcome is obviously superior. This is why reasonable board members disagree and why shareholders might reach different conclusions.

The Broader Media Consolidation Story

This lawsuit isn't just about Paramount and WBD. It's a window into the broader media consolidation that's reshaping the industry.

Over the past 20 years, media has consolidated dramatically. The number of companies controlling most of the world's entertainment has shrunk from dozens to roughly six: Netflix, Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount, Sony, and a few others. This consolidation reflects economics: global reach, diverse content, and streaming scale matter enormously. Companies without scale struggle.

The Paramount-WBD dispute is part of this consolidation story. Paramount wants to stay relevant as a competitor by growing scale. WBD is trying to position itself optimally in a market dominated by Netflix and Disney. Netflix is consolidating entertainment assets. Everyone is jockeying for position in a market that's consolidating toward a small number of huge players.

From a shareholder perspective, consolidation can be good (scale benefits, cost savings, broader market reach) or bad (monopoly power, less innovation, higher prices). From a consumer perspective, consolidation might reduce choice and increase costs, but it might also increase content quality and investment if consolidated companies can achieve better economics.

From an industry perspective, consolidation is probably inevitable. Media economics increasingly favor scale. Companies without global reach and diverse content libraries will struggle. Paramount-sized companies are genuinely at risk of being marginalized between Netflix (larger, better positioned) and Disney (more diversified, stronger brand). This is why Paramount is fighting hard to acquire WBD. Without WBD or similar scale-increasing M&A, Paramount's long-term competitive position might deteriorate.

What Regulatory Obstacles Might Emerge?

Neither the Netflix deal nor the Paramount offer is obviously blocked by regulators, but both face some risk.

The Netflix deal might face scrutiny because Netflix is acquiring significant entertainment assets and becoming even more dominant in streaming. If regulators believe Netflix has excessive market power, they might require conditions (like content licensing requirements) or might even block the deal entirely. This risk is probably modest because Netflix already exists as a dominant player, so the incremental market power from WBD assets is limited.

Paramount's proposed combination might face more regulatory risk because it creates a new large player with presence across theatrical, television, streaming, cable, and international markets. Regulators might view this as threatening competition in any particular segment. However, Paramount's overall market share (across all media) would be smaller than Netflix or Disney, so there's likely no absolute size threshold triggering automatic regulatory concern.

The most likely regulatory outcome is that both deals would be approved, possibly with conditions. Netflix might need to accept content licensing requirements or commit to independent production company relationships. Paramount might need to divest certain assets to address specific competitive concerns. But outright regulatory blocks seem unlikely unless regulators fundamentally change their approach to media consolidation.

The Precedent: What This Case Means for Future M&A

Regardless of the outcome, this case will establish legal precedent affecting future M&A disputes. If Paramount wins, they'll establish that boards must seriously engage with all bidders and provide extensive disclosure about alternative offers. This would strengthen hostile bidders in future disputes.

If WBD wins, they'll establish that boards have substantial deference to prefer one bidder over another, even if the rejected bidder makes a reasoned argument for superiority. This would strengthen incumbent boards in future disputes.

Either way, the case will generate legal guidance about what disclosure Delaware law actually requires and what "fair process" means in the context of competing bids. This guidance will affect every future major M&A dispute.

The case will also signal to companies how seriously Delaware courts take process and disclosure. If the judge issues harsh findings against WBD's board, future boards will be more careful about engaging with all bidders and documenting fair processes. If the judge sides with WBD, boards will feel more comfortable making strategic decisions and moving forward without endless engagement with alternative bidders.

Litigators are probably already analyzing this case to understand likely precedent and how it might affect their own disputes. This is how common law works: individual cases establish principles that guide future behavior and decision-making.

TL; DR

- Paramount Escalates: After multiple rejected bids, Paramount Skydance filed suit in Delaware Chancery Court challenging WBD's rejection and demanding disclosure of valuation assumptions and board decision-making.

- Proxy Fight Initiated: Paramount CEO David Ellison nominated a slate of directors for WBD's 2026 annual meeting, aiming to replace board members resistant to Paramount's offer.

- Netflix Deal at Risk: The Netflix deal, while committed, faces uncertainty from litigation. Court orders could force shareholder disclosure or voting on alternatives.

- Discovery Global is Central: The valuation and future of Discovery Global (cable networks spinout) is the financial crux. Different valuations favor different deals.

- Leverage vs. Certainty Trade-off: Paramount's offer provides higher scale but requires significant debt. Netflix's offer provides execution certainty but relies on a third party and splits assets.

- 12-18 Month Timeline Expected: Delaware Chancery proceedings typically take 12-18 months minimum. Shareholder votes might be delayed pending litigation outcomes.

- Shareholder Value Depends on Execution: Paramount shareholders benefit if integration succeeds and synergies materialize; WBD shareholders benefit if Netflix deal closes and Discovery Global thrives independently.

FAQ

Why is Paramount suing instead of just accepting rejection?

Paramount believes WBD's board process was flawed and shareholders didn't get adequate information to make an informed decision. By suing, Paramount forces WBD to disclose additional information and potentially hold a new shareholder vote where Paramount can make its case directly. Litigation also creates pressure for settlement negotiations, where WBD might accept improved terms from Paramount rather than continue fighting.

What is Discovery Global and why does it matter so much?

Discovery Global is the collection of cable networks (HGTV, Food Network, TLC, Animal Planet) that WBD plans to spin off as an independent publicly traded company under the Netflix deal. Its valuation is crucial because if it's worth more under Paramount's combined ownership versus independent, that favors Paramount's offer. If it's more valuable independent, that favors Netflix's deal. Paramount's lawsuit specifically demands disclosure of how WBD valued this asset.

Could regulatory authorities block either deal?

Regulatory risk exists for both deals but isn't extreme. The Netflix deal might face scrutiny for expanding Netflix's content dominance, but Netflix already dominates streaming. Paramount's combination might face scrutiny for creating a company with presence across theatrical, television, streaming, and cable markets. Most likely, both deals would be approved with possible conditions, but regulatory uncertainty could delay either deal by 6-12 months.

What are the chances Paramount actually wins the lawsuit?

This is genuinely uncertain. Paramount has legitimate arguments about board process and disclosure, but WBD also has legitimate defenses about fiduciary judgment and strategic preference. Delaware judges understand M&A law deeply, so sophisticated legal maneuvering doesn't help either side. The outcome probably depends on specific factual findings about what the board knew, when they knew it, and whether they seriously considered Paramount's bids. Based on historical Delaware precedent, I'd estimate roughly 40-50% probability that Paramount wins on major claims, but exact odds depend on undisclosed board materials discovered during litigation.

What happens to WBD shareholders if Paramount wins?

WBD shareholders would receive equity in the combined Paramount-WBD company instead of cash/stock from Netflix and shares in spinoff Discovery Global. Value would depend on how successfully Paramount integrates the companies and realizes promised cost savings. Shareholders would also bear the financial risk of Paramount's debt burden. The combined company would be larger (potentially the third-largest global media company) but also more leveraged and more complex operationally.

Why would Netflix agree to sell to Paramount if Paramount's offer is superior?

Netflix wouldn't voluntarily sell to Paramount, but if Paramount wins litigation and proxy fight, WBD's board could be forced to reject the Netflix deal (or WBD shareholders could vote to terminate it) to accept Paramount's superior offer. This is exactly why WBD's merger agreement with Netflix includes "fiduciary out" provisions allowing the board to terminate for superior offers. If courts rule that Paramount's offer is superior and process was flawed, these fiduciary outs might force WBD to negotiate with Paramount.

How long will this litigation actually take?

Expect 12-18 months minimum from lawsuit filing to resolution. This includes initial motions (60 days), discovery (4-6 months), summary judgment briefing (2-3 months), and potentially trial preparation. If either side appeals adverse rulings, add another 6-12 months. The Netflix deal probably won't close while material litigation is pending, so WBD shareholders should expect extended uncertainty. Some Delaware judges expedite proceedings if shareholder votes are imminent, which could compress the timeline slightly.

Could this lawsuit force a new shareholder vote on the Netflix deal?

Yes, that's one of Paramount's goals. If the Delaware judge finds that WBD's disclosures were inadequate, they might order supplemental disclosure to shareholders and a new vote on the Netflix deal. This new vote would occur with better information about asset valuations and board decision-making. Alternatively, shareholders could vote on whether to permit the Netflix deal to close before the 2026 annual meeting where Paramount's proxy fight occurs. The judge has significant power to determine what shareholders need to vote fairly and can order new votes if current votes are uninformed.

Is the Netflix deal binding or can WBD's board still back out?

The Netflix deal is binding in the sense that WBD's board committed to it, but "fiduciary out" provisions allow the board to terminate for superior offers or if a superior acquisition proposal emerges. If Paramount's litigation succeeds in proving their offer is superior and process was flawed, the board might be required to engage with Paramount rather than forcing shareholders to accept Netflix. This is the legal uncertainty that makes the Netflix deal somewhat fragile while litigation is pending.

Where Technology and Automation Can Help Media Companies Navigate Complex M&A

Interestingly, the complexity of major M&A disputes like this one highlights where modern automation tools could genuinely help. The massive discovery processes, document analysis, and financial modeling required in cases like Paramount v. WBD could benefit tremendously from AI-powered automation.

For example, Runable offers AI-powered document generation and workflow automation that could help legal teams automatically generate comprehensive briefing documents, organize discovery materials, and create financial presentations from raw data. When law firms are managing millions of pages of documents in a case like this, Runable's automation capabilities could significantly reduce manual work and accelerate analysis.

Use Case: Automate generation of discovery summary reports by extracting key data from thousands of documents, turning unstructured information into organized, executive-ready presentations.

Try Runable For FreeSimilarly, media companies evaluating acquisition offers (like WBD did) could use AI-powered tools to rapidly model different scenarios, generate financial presentations, and create comparison documents that shareholders need to make informed decisions. Better tools might have helped WBD create the exact disclosures Paramount is now suing for, avoiding litigation entirely.

The lesson here is that as deals and disputes get more complex, the supporting technology infrastructure becomes more important. Companies that can rapidly organize information, generate clear presentations, and create comprehensive documentation are better positioned to navigate disputes and make good strategic decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Paramount filed suit in Delaware Chancery Court demanding WBD disclose how it valued Discovery Global and engaged with competing bids

- Paramount launched parallel proxy fight to nominate new board members who would negotiate, escalating pressure significantly

- WBD's Netflix deal faces genuine legal and shareholder uncertainty while litigation proceeds, likely 12-18 months minimum

- Paramount's offer provides scale and integration benefits but requires significant debt leverage, creating financial risk

- Netflix deal offers execution certainty but splits assets and leaves Discovery Global to operate independently in challenging environment

- Delaware courts emphasize board process and disclosure, giving Paramount real chance of forcing shareholder vote on alternatives

- Case will establish precedent affecting future M&A disputes about what disclosure Delaware law requires

Related Articles

- Warner Bros. Discovery Rejects Paramount Skydance Bid: Why Netflix Won [2025]

- The Complete History of TiVo: How It Changed TV Forever [2025]

- TikTok's 2026 World Cup Live Deal: What It Means for Sports Broadcasting [2025]

- Star Trek: Starfleet Academy Balances Teen Drama With Intergalactic Stakes [2025]

- Why Stranger Things Finale in Theaters Proved Streaming's Missing Piece [2025]

![Paramount Skydance's Lawsuit Against Warner Bros. Discovery [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/paramount-skydance-s-lawsuit-against-warner-bros-discovery-2/image-1-1768241517055.jpg)