Introduction: The Convergence of Betting and Breaking News

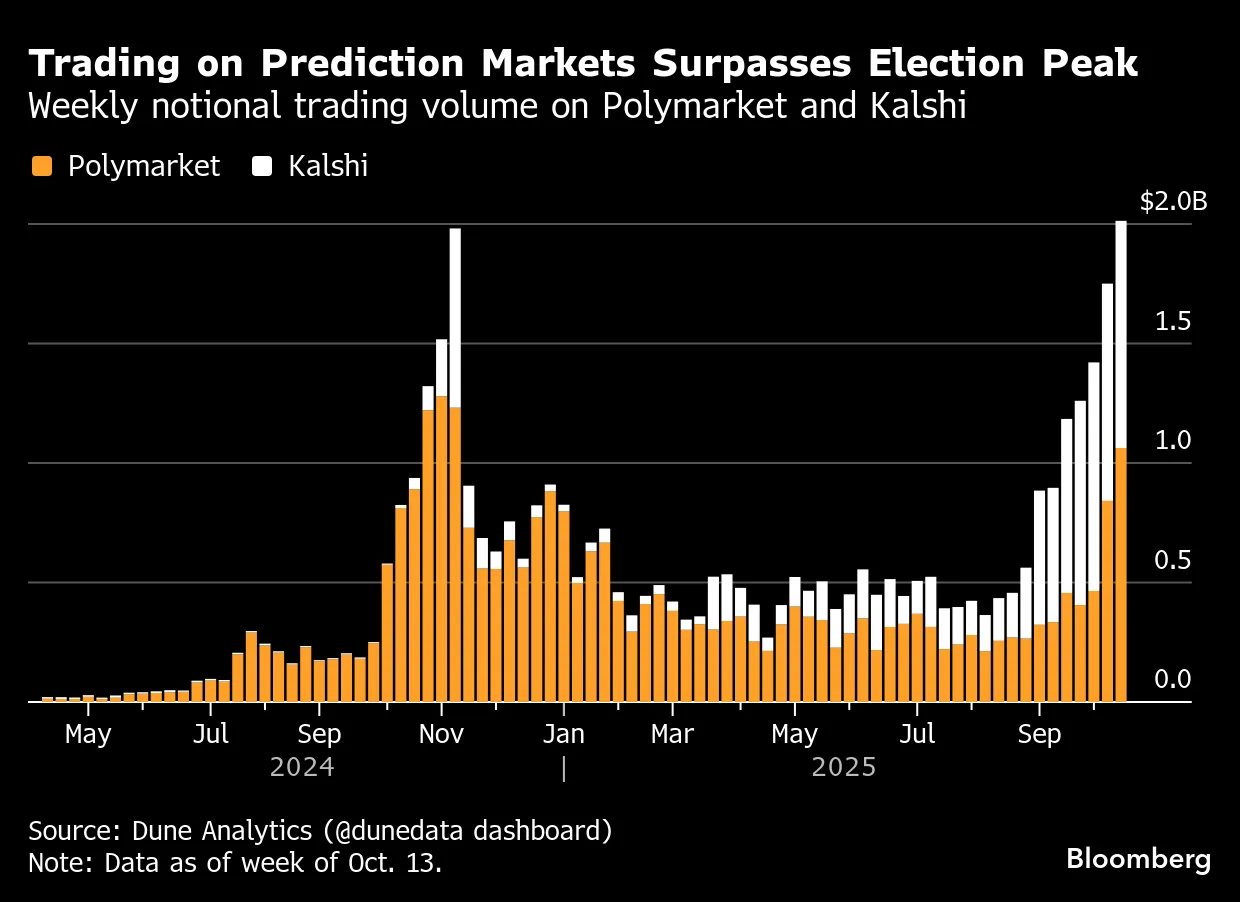

The landscape of modern journalism is undergoing a seismic shift that few anticipated just two years ago. What was once firmly separated—the world of financial betting and the world of news reporting—is now merging into a complex ecosystem where predictions about future events are becoming integrated into mainstream media coverage. Polymarket and Kalshi, two of the largest prediction market platforms, have orchestrated a series of high-profile partnerships with some of the world's most established news organizations: Dow Jones, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, CNBC, and others. These aren't casual collaborations—they represent a fundamental reconsideration of what news is, how it's valued, and who gets to define it.

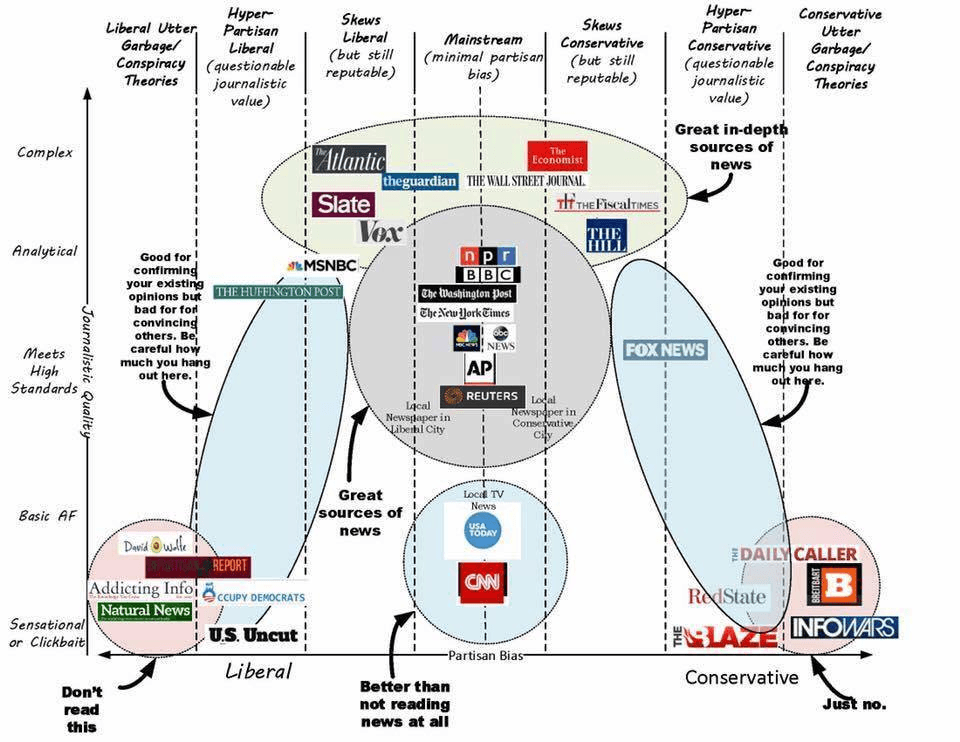

On the surface, this trend seems innocuous enough. What could be wrong with incorporating predictive data into news coverage? After all, markets have long been used as forecasting mechanisms, and aggregate wisdom from many participants often produces surprisingly accurate predictions. Yet beneath this veneer lies a more troubling narrative about the commercialization of information, the blurring lines between speculation and reporting, and the quiet but systematic rebranding of prediction markets as something they fundamentally are not: journalism.

The impetus for this pivot is revealing. Prediction markets initially gained prominence and profitability through sports betting and political wagering. However, as regulators began scrutinizing their operations and questioning the regulatory status of these platforms, the companies behind them faced mounting pressure. Rather than retreat, companies like Polymarket and Kalshi made a strategic choice: rebrand themselves as forward-looking news platforms rather than gambling operations. This maneuver is both commercially astute and conceptually troubling, blending a legitimate desire for better forecasting methods with a fundamental misunderstanding—or deliberate mischaracterization—of what journalism actually does and why it matters.

To understand why this distinction matters, we need to examine what news fundamentally is, how prediction markets work, what the partnerships between these platforms and news organizations actually entail, and what the long-term implications might be for media credibility, financial incentives, and the public's understanding of probability and uncertainty. This is not merely a story about business innovation; it's a story about information itself, and how powerful economic interests are reshaping the institutions we rely on to understand our world.

What Is Journalism, Actually?

The Historical Foundation of News

Journalism, in its most essential form, is a documented record of events that have already occurred. The earliest known predecessor to modern journalism was Rome's Acta Diurna, circulating over two thousand years ago as an official chronicle of births, deaths, laws, and financial transactions. These weren't predictions about what might happen—they were records of what had happened. Similarly, in the Tang Dynasty, China maintained official circulars documenting historical events. When European businessmen began circulating written accounts of important events to their contacts in the 15th century, they established the template for modern newspapers: communicating information about the recent past to those who needed to know.

This historical continuity is not incidental to understanding journalism. The core function of news has remained remarkably consistent across centuries and cultures: to document, verify, and communicate facts about events that have already transpired. A newspaper tells you what happened yesterday, or this morning, or twenty minutes ago. Online news sites, freed from the constraints of printing presses, accelerated this timeline further, but the fundamental purpose remained unchanged. News exists to establish a shared factual record of reality, which forms the foundation for informed citizenship, business decision-making, and social cohesion.

The Critical Role of Verification and Investigation

Beyond simply documenting events, journalism involves critical investigation—reporters pursuing leads, interviewing sources, cross-referencing documents, and uncovering information that powerful actors would prefer to keep hidden. This investigative function requires not just the reporting of facts, but the contextual understanding that gives those facts meaning. When The Washington Post published the Pentagon Papers, they weren't predicting the trajectory of the Vietnam War; they were revealing what had been hidden about its past. When investigative journalists expose corporate malfeasance or governmental corruption, they're documenting what happened, not what might happen.

Journalism also involves editorial judgment—decisions about what is newsworthy, what serves the public interest, and how information should be contextualized. A good journalist doesn't just report that a politician said X; they verify the claim, provide relevant context, and explain why it matters. This requires expertise, judgment, and a commitment to accuracy that is fundamentally different from the mechanics of prediction markets.

Daniel Boorstin's "Pseudo-Events" and Modern Media

Media theorist Daniel Boorstin's concept of "pseudo-events" is essential to understanding the current confusion about prediction markets and news. A pseudo-event, in Boorstin's framework, is a planned occurrence—an awards show, earnings call, political convention, or product launch—whose outcome can sometimes be known or predicted in advance because it is choreographed. Newspapers certainly cover pseudo-events, and they often do so alongside coverage of genuine events (natural disasters, unexpected vote outcomes, unplanned developments).

Prediction markets are, in a sense, betting on pseudo-events and genuine events alike. But here's the critical distinction: betting odds are not journalism; they are derivatives of journalism. A betting market might reflect informed speculation about what will happen, but that speculation depends entirely on the quality and accuracy of the underlying information (which must come from actual news reporting) and the collective judgment of market participants (who may or may not be knowledgeable). When Polymarket or Kalshi's odds shift, something significant has often been reported through traditional journalism—a poll was released, economic data came out, a political development occurred. The prediction market is responding to news, not generating it.

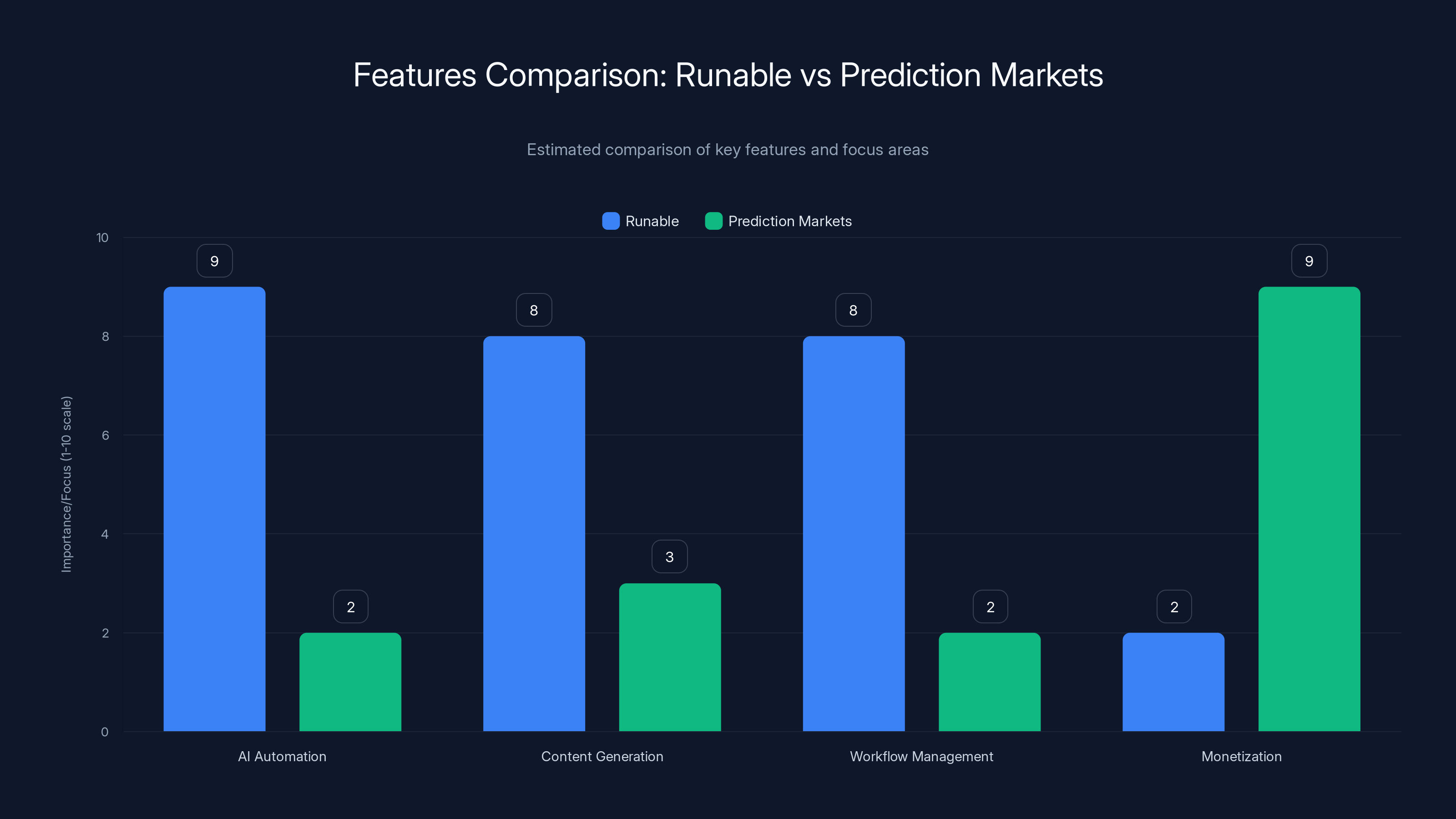

Estimated data shows Runable excels in AI automation and workflow management, while prediction markets focus on monetization. Estimated data.

Understanding Prediction Markets: Mechanics and Economics

How Prediction Markets Actually Work

Prediction markets operate on a deceptively simple principle: participants bet money on the likelihood of future events, and their aggregated bets create a market price that theoretically represents the collective probability assessment of that event. If you believe the probability reflected in the market is too high, you sell shares; if you believe it's too low, you buy shares. As new information arrives or participants revise their views, prices adjust.

The theoretical elegance of this mechanism is genuinely compelling. The "wisdom of crowds" effect suggests that when many people with diverse information and incentives are making probabilistic judgments, the aggregate outcome often approximates the true probability better than any individual expert could achieve. This principle has been documented across numerous domains—betting markets have correctly predicted many election outcomes, for instance, and commodity markets often anticipate economic trends before traditional forecasters do.

However—and this is crucial—prediction markets achieve their predictive power by processing information that comes from somewhere else. The bettors on Polymarket aren't conducting their own investigations into whether a particular policy will pass Congress; they're reading news reports about legislative prospects, polling data released by journalists, and expert analysis. The market aggregates this information and reflects it in odds, but it doesn't create new information.

The Economic Structure of Prediction Markets

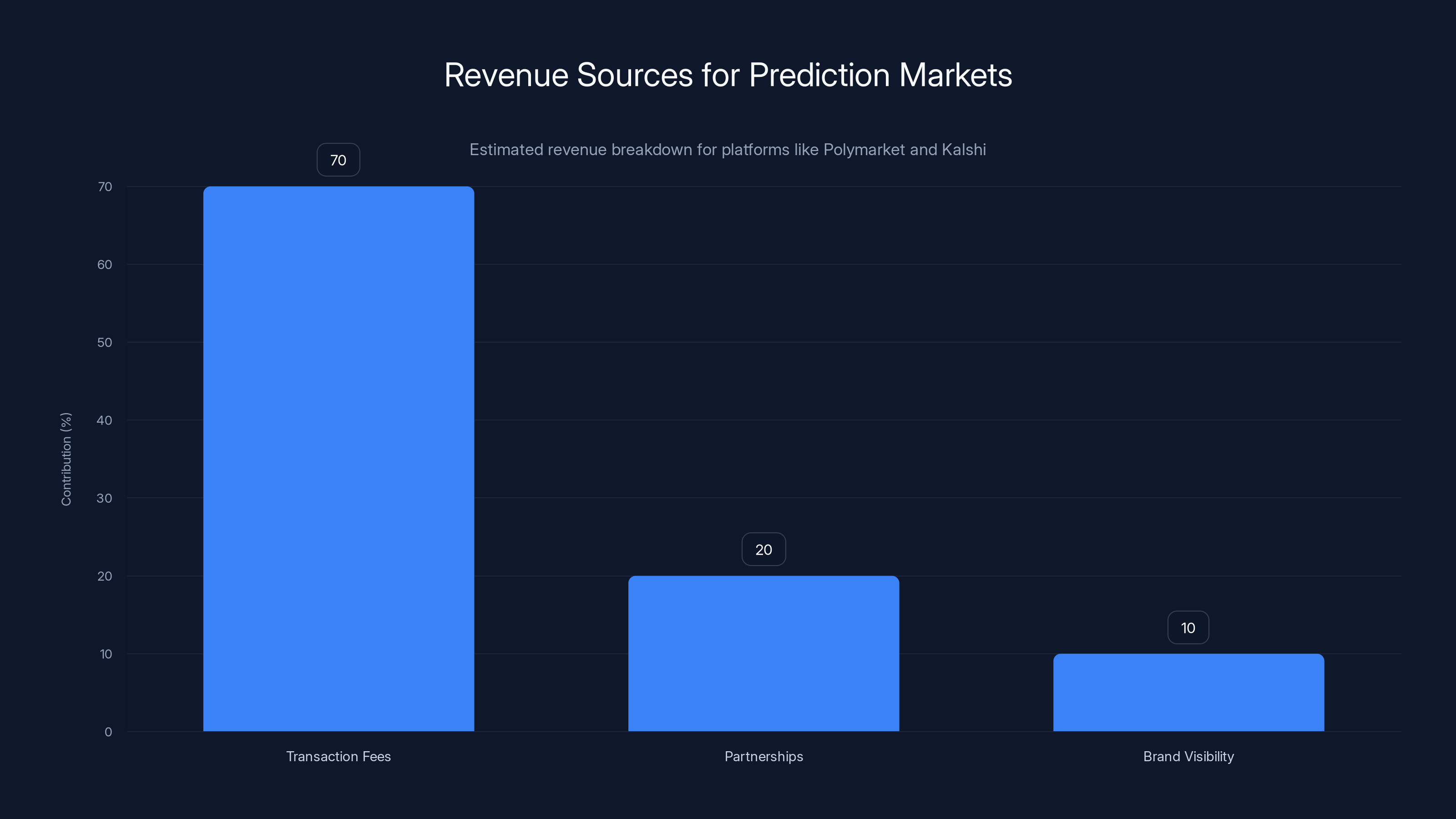

Prediction markets make money in several ways. The platform takes a percentage of bets (typically 2-5% commission), and the companies behind these platforms profit based on trading volume. For Polymarket and Kalshi, profitability scales with total transaction volume, not with the accuracy of predictions or the quality of information being aggregated.

This economic structure matters enormously when considering partnerships with news organizations. A prediction market platform benefits when more people are betting on more events. Every news story becomes a potential betting opportunity, and every partnership with a media outlet creates more visibility, more engagement, and more potential bettors. From a purely commercial perspective, the motivation for these partnerships is obvious: they're not designed to improve journalism, but to expand the market for prediction-based gambling.

Regulatory Pressures and the Rebranding Imperative

Regulators have taken an increasingly skeptical view of prediction markets, particularly regarding their classification and oversight. In the United States, the regulatory status of prediction markets exists in an ambiguous middle ground. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) treats some prediction markets as derivatives, while others have attempted to operate under exemptions meant for different purposes. For years, Polymarket operated in regulatory grey zones, and Kalshi has similarly faced regulatory scrutiny.

When a business model begins attracting regulatory attention and operating restrictions, there's a natural incentive to rebrand and reposition. By positioning prediction markets as a new form of journalism or data source for legitimate news organizations, Polymarket and Kalshi achieve multiple objectives simultaneously: they gain credibility by association with established media brands, they demonstrate that their platforms serve legitimate informational purposes (which might help with regulatory arguments), and they dramatically expand their addressable market from just bettors to include all consumers of news media.

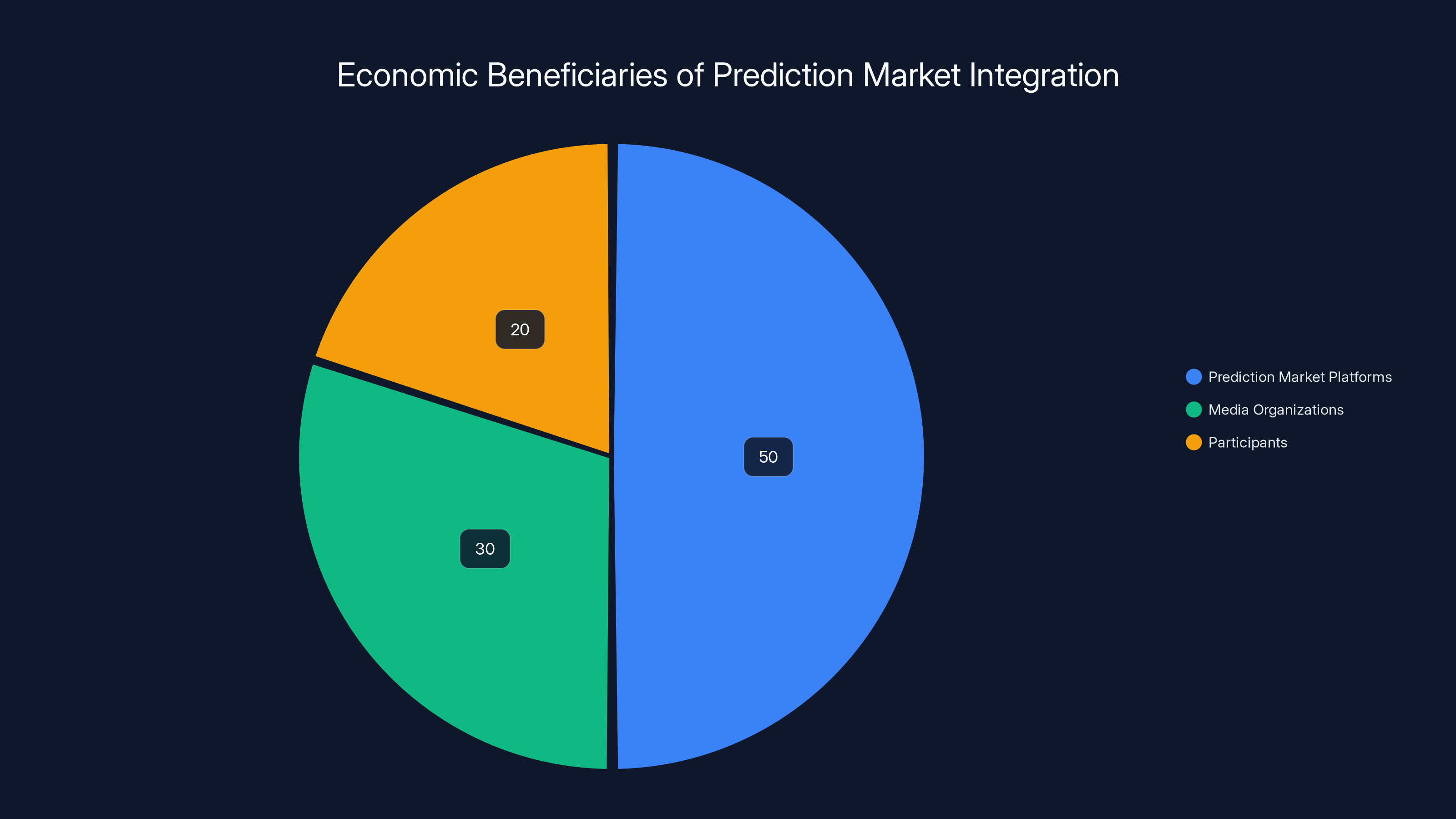

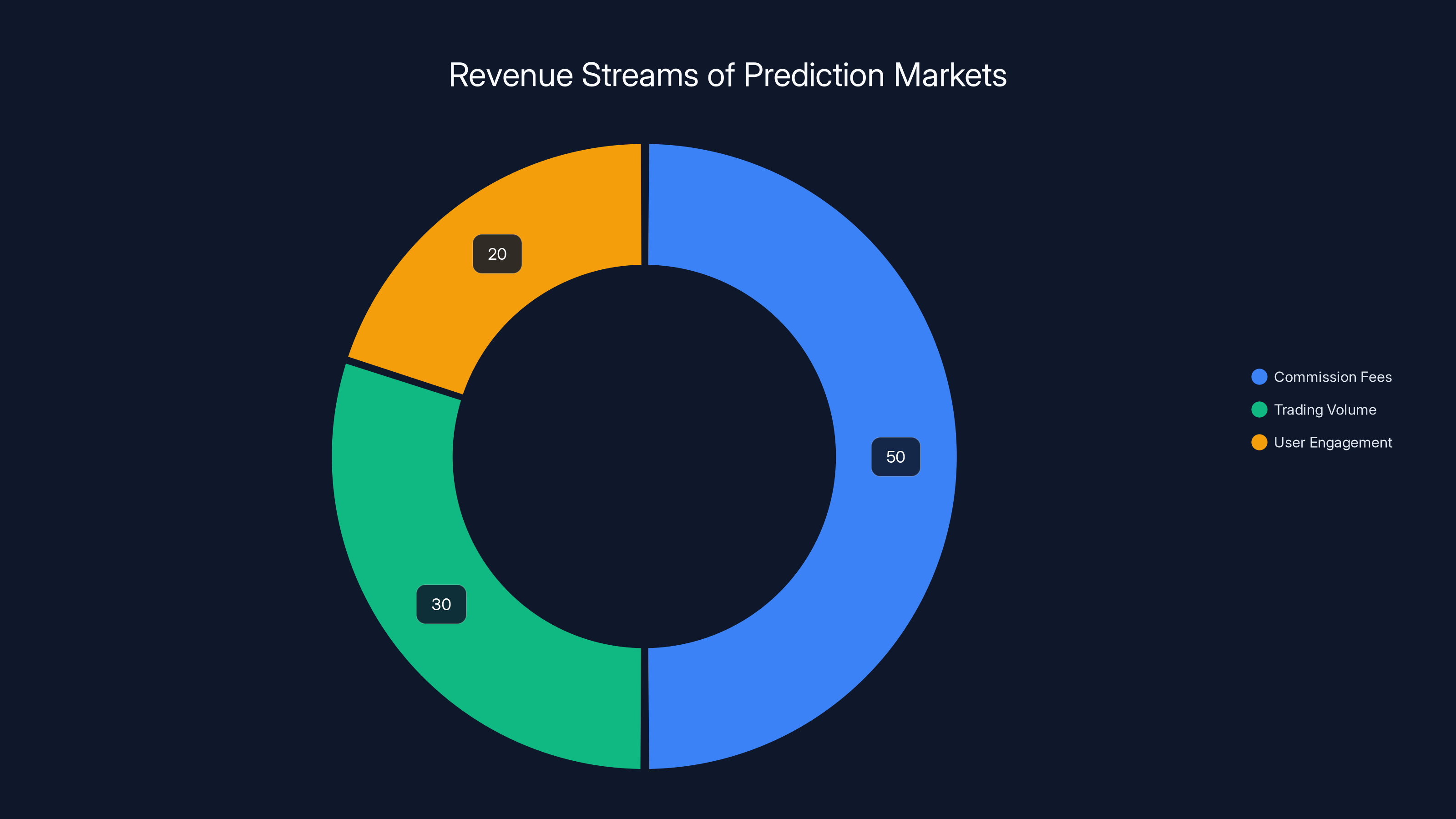

Prediction market platforms gain the most from transaction volume, followed by media organizations that leverage market data for content. Participants benefit the least, primarily through engagement. Estimated data.

The Partnerships: Who's Involved and What Do They Actually Entail?

Dow Jones and The Wall Street Journal

Dow Jones' partnership with Polymarket represents the most significant integration to date. The agreement involves incorporating Polymarket's betting data and odds into Wall Street Journal content and broader Dow Jones newsroom operations. This isn't merely mentioning prediction markets as a data point; it's weaving market-generated predictions into regular editorial content, giving them the same editorial weight and presentation as traditional reporting.

The implications of this partnership are substantial. When readers encounter a Wall Street Journal article about an upcoming corporate merger or regulatory decision, they now see not just the journalist's analysis but also Polymarket's odds on the outcome. This creates an implicit endorsement—the Journal's editorial judgment suggests that these odds are meaningful data points worth presenting alongside traditional reporting. Yet the Journal's readers likely have no clear understanding of where these odds come from, how reliable they are, or what financial incentives might be influencing the bettors who create them.

CNN and CNBC: Broadcasting Prediction Markets

CNN's integration of Kalshi betting odds and CNBC's agreement to "infuse its programming" with Kalshi data represent a different dynamic—the incorporation of prediction market information into television news programming. When a cable news host mentions that Kalshi's odds suggest a 35% probability of a certain policy outcome, the audience rarely learns that these odds come from a betting market, that they're generated by unvetted participants who may have incomplete information, or that they're more similar to a sports betting line than a scientific forecast.

Television news, by its nature, has always been more focused on engagement and narrative than print journalism. The integration of prediction market odds fits neatly into cable news's preference for dramatic volatility and real-time updates. Odds shifting throughout the day provides built-in drama that feeds the news cycle, which creates an incentive for constant coverage, which drives more betting, which generates more content opportunities. It's a closed loop that benefits everyone except the viewer trying to develop an accurate understanding of what's actually likely to happen.

The Broader Pattern of Partnerships

These aren't isolated deals; they represent a coordinated strategy to integrate prediction market data across the media ecosystem. By securing partnerships with multiple major news organizations simultaneously, Polymarket and Kalshi are essentially establishing prediction markets as a standard data source for financial journalism. This creates network effects—once one major outlet integrates prediction market data, competitors feel pressured to do the same to avoid appearing behind the curve.

The Conceptual Problem: Conflating Predictions with News

The Fundamental Category Error

At the heart of these partnerships lies what philosophers would call a category error—the confusion of fundamentally different types of information into a single bucket. Predictions about the future and documentation of the past are not the same thing. A newspaper traditionally answers the question "What happened?" A prediction market answers the question "What do we think is likely to happen?" These are distinct epistemic projects with different standards of evidence, different sources of credibility, and different relationships to truth.

When Polymarket's CEO or other advocates suggest that prediction markets are "the next generation of news" or that "knowing the future before it happens" would be valuable journalism, they're either fundamentally confused about what journalism is, or they're deliberately obscuring the distinction for commercial purposes. The rhetoric suggests that predictive odds are a new form of information that should complement traditional reporting. But this misses something essential: odds don't tell you anything true about the world in the way that verified facts do. An 85% probability that a policy will pass is fundamentally different from confirmation that a policy has passed.

The Problem of Epistemic Authority

Journalism derives its authority from institutional practices designed to verify information and minimize error. A claim in The New York Times carries weight because of the Times's editorial standards, fact-checking procedures, and reputation for correction and accountability. If the Times gets something wrong, there are established procedures for acknowledging and correcting it. The Times also has incentives (though imperfect ones) aligned with accuracy—newspapers that consistently mislead their readers lose credibility and audience.

Prediction market odds derive their authority from an entirely different source: the aggregated bets of market participants. This is not a weak form of authority necessarily—markets can be surprisingly accurate at forecasting certain types of events. But the authority is contingent on several conditions: participants must have access to good information (which they get from news sources), they must have relevant expertise (which varies widely), and they must not have perverse incentives that would push odds away from their true probabilities (a condition that's frequently violated).

When news organizations present prediction market odds alongside traditional reporting, they're implicitly granting these odds the same epistemic authority as verified facts. This is a categorical mistake. The odds are interesting data points that might deserve discussion, but they're not equivalent to reporting.

Noted Poker Player as "Respected Stats Journalist"

The partnership between Nate Silver, a prominent statistician and poker player, and Polymarket illustrates the slippage in these categories. Silver built a valuable career in sabermetrics and political forecasting, using statistical methods to model elections and sports outcomes. His popularity and media presence gave him a platform to discuss probability and uncertainty in ways that reached broad audiences. However, there's a significant distance between teaching people how to think about uncertainty and endorsing a betting market as a news source. By accepting an advisory role with Polymarket, Silver is—whether intentionally or not—lending his credibility as a statistician to what is fundamentally a gambling platform.

Transaction fees are the primary revenue source for prediction markets, contributing an estimated 70% to their revenue. Partnerships and brand visibility also play roles but to a lesser extent. Estimated data.

Who Benefits? The Economic Incentives of Prediction Market Integration

The Business Model: Volume Over Accuracy

As noted earlier, prediction market platforms profit from transaction volume. Every bet placed, every share traded, generates a small percentage commission that flows to the platform. This creates a structural incentive that's independent of accuracy: the goal is to maximize engagement and participation, not to produce the most accurate forecasts.

Consider what happens when a news organization regularly covers prediction market odds. Each story generates interest, which drives new participants to the markets, which increases trading volume, which increases commission revenue for the platform. Accuracy in prediction is nice (it keeps people engaged and maintains the market's reputation), but it's secondary to volume. This is why prediction markets do so well at covering high-stakes, high-drama events—elections, major business outcomes, celebrity gossip—rather than the kinds of mundane, important issues that actually deserve more public attention.

Media Organizations: The Temptation of Free Content

From a news organization's perspective, incorporating prediction market data offers distinct advantages. First, it provides pre-made content that fills time or space without requiring original reporting or analysis. A CNBC segment on "What Prediction Markets Say About Fed Policy" requires no expensive investigative work; the host just reads odds and maybe adds some color commentary. This is content multiplication with minimal incremental cost.

Second, prediction market data provides a convenient angle for stories that might otherwise be hard to make interesting. Political coverage, business analysis, and economic commentary all become more "engaging" when there's a running scoreboard of probabilities. The odds provide dramatic narratives—"Will the merger go through? Kalshi says it's 60% likely, down from 75% this morning!"—that drive engagement.

Third, there's a reputational benefit. By associating with prediction markets, news organizations position themselves as forward-thinking, innovative, and engaged with cutting-edge forecasting methods. This appeals to a certain demographic of audience members and advertisers, particularly those in the financial industry who are already familiar with probability-weighted thinking.

The Circular Reinforcement Loop

These incentive structures create a circular reinforcement loop. Prediction markets drive engagement and betting volume partly because they're integrated into news coverage. News organizations find prediction market content valuable because it drives engagement. Prediction market platforms invest in partnership and integration because it drives betting volume. Each participant in this loop has strong incentives to continue and expand it, regardless of whether the outcome is actually beneficial for public understanding or journalistic quality.

The Accuracy Question: Do Prediction Markets Actually Predict Well?

The Case for Prediction Market Accuracy

There's genuine evidence that prediction markets can be surprisingly accurate forecasters. Betting markets on U. S. presidential elections, for instance, have often been more accurate than traditional polling, particularly in certain years and contexts. Commodity markets frequently anticipate economic trends. Sports betting markets are remarkably good at predicting outcomes. This track record has led to a considerable body of academic research suggesting that markets can aggregate dispersed information in ways that produce accurate probability estimates.

The theoretical logic is compelling: if many people are betting their money on outcomes, and each person has at least some relevant information or expertise, then the aggregated result should gravitate toward true probabilities. Wrong predictions get punished by losses; correct predictions get rewarded by gains. Over time, this should select for accuracy.

The Limitations and Failure Modes

However, this idealized version of how prediction markets work depends on conditions that are frequently not met in practice. First, participants in prediction markets don't all have equal access to information or expertise. A sophisticated hedge fund trader with proprietary research capabilities has an enormous advantage over an ordinary citizen with a Polymarket account. This creates opportunities for informed insiders to exploit uninformed participants, which means odds can be systematically skewed away from true probabilities if there's asymmetric information.

Second, prediction markets are vulnerable to herding and momentum effects. If early bets push odds in a particular direction, subsequent bettors may assume that the early bettors had good information and follow them, creating a cascade effect that pushes odds further from their true value. This is particularly pronounced for events that are relatively unfamiliar or difficult to assess.

Third, prediction markets can be manipulated by actors with sufficient capital and motivation. Someone who owns a media outlet, holds financial positions that would benefit from particular outcomes, or simply wants to influence public perception might be willing to lose money betting in a particular direction if the resulting odds generate news coverage that benefits them in other ways. This is especially true when the amounts wagered on prediction markets are tiny compared to the value at stake in actual outcomes.

Fourth, the quality of predictions depends entirely on the underlying information. If all market participants are reading the same biased or incomplete information sources, or if important information is asymmetrically distributed, the aggregation of bad information is still bad information. The wisdom of crowds effect breaks down when the crowd lacks relevant knowledge.

Prediction Market Performance During Crises and Surprises

Historically, prediction markets have performed quite poorly at anticipating genuine surprises—events that run counter to widespread expectations. The 2016 U. S. presidential election, the 2008 financial crisis, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic—in each of these cases, prediction markets were significantly miscalibrated. They did well at predicting expected outcomes from existing information, but they failed catastrophically when the unexpected happened.

This limitation is crucial because it reveals something fundamental: prediction markets are only as good as the informational environment they operate in. When events break the historical pattern or when critical information hasn't yet entered public circulation, markets often fail. A news organization that presents prediction market odds as if they carry the authority of verified information is potentially misleading its audience about how much is actually known and how likely various outcomes actually are.

Estimated data shows that commission fees constitute the largest revenue source for prediction markets, followed by trading volume and user engagement.

Case Studies: Prediction Markets and Political Coverage

The 2024 Election and Market Volatility

The integration of prediction markets into election coverage has become one of the most prominent examples of this phenomenon. During the 2024 election cycle, cable news networks regularly reported on Kalshi and Polymarket odds alongside traditional polling, often giving them equal weight or even more prominence. When odds shifted—sometimes by single percentage points—it generated news stories and commentary that could be seen as treating the markets as if they were superior to actual polling data.

The problem is that election prediction markets are often less stable and less reliable than traditional polls when it comes to day-to-day movements. Polls measure actual voter intentions (even if imperfectly); betting odds measure the aggregated beliefs of market participants about what voters intend. When a poll changes significantly, it's reporting new information about voter preferences. When betting odds change, it could be reporting new information, or it could be the result of a few large bets by participants trying to position themselves for profit or influence.

Economic Policy and Business Outcomes

In business coverage, prediction markets have become integrated into stories about mergers, regulatory decisions, and company outcomes. A CNBC story about a pending merger might report the current betting odds on deal completion, treating this as equivalent to expert analysis of the merger's prospects. Yet these odds have been substantially wrong many times—bets placed by participants who may lack deep knowledge of corporate structures, regulatory environments, or management quality.

The Bias Toward Dramatic Scenarios

Prediction markets have a systematic bias toward covering dramatic, contested outcomes where large sums might be wagered. The probability that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates by 50 basis points gets substantial market attention and coverage. The probability that a regulatory agency will stick to its existing policy, even if that's the most likely outcome, generates less betting volume and less news coverage. This means prediction market integration systematically biases news coverage toward dramatic scenarios and away from baseline outcomes, even when the baseline is more probable.

The Role of Financial Incentives in Shaping Coverage

Direct Incentives: Betting Volume and Engagement

When a news organization regularly reports on prediction market odds, it creates direct financial incentives for the news organization and the platform. For the platform, each story drives potential new bettors to the market. For the news organization, stories about prediction markets generate engagement and attract audiences interested in probability and speculation. Over time, this creates an incentive structure that biases editorial decisions toward stories that can be framed around prediction market odds.

A financial reporter might reasonably choose to cover a merger story because there's substantial public interest and the outcome is genuinely uncertain. But the decision to emphasize prediction market odds in the coverage—to lead with them or give them equal weight to fundamental analysis—is influenced by the knowledge that readers interested in prediction markets drive engagement. This is a subtle but powerful form of bias that shapes what stories get told and how they're framed.

Indirect Incentives: Credibility and Audience Acquisition

Beyond direct engagement metrics, news organizations have incentives to maintain the credibility and growth of prediction markets themselves. If Polymarket or Kalshi loses credibility, or if regulatory action threatens their viability, the data that these news organizations have invested in incorporating into their coverage becomes less valuable. This creates an indirect incentive to avoid overly critical coverage of prediction market limitations or to downplay concerns about their accuracy or manipulation potential.

This is a subtle form of bias—nobody's telling reporters "don't be critical of prediction markets." Rather, the incentive structure creates an environment where critical analysis is less likely to be commissioned, and positive coverage is more naturally rewarded by engagement metrics. Over time, this shapes editorial culture in ways that favor prediction market integration without anyone explicitly making that decision.

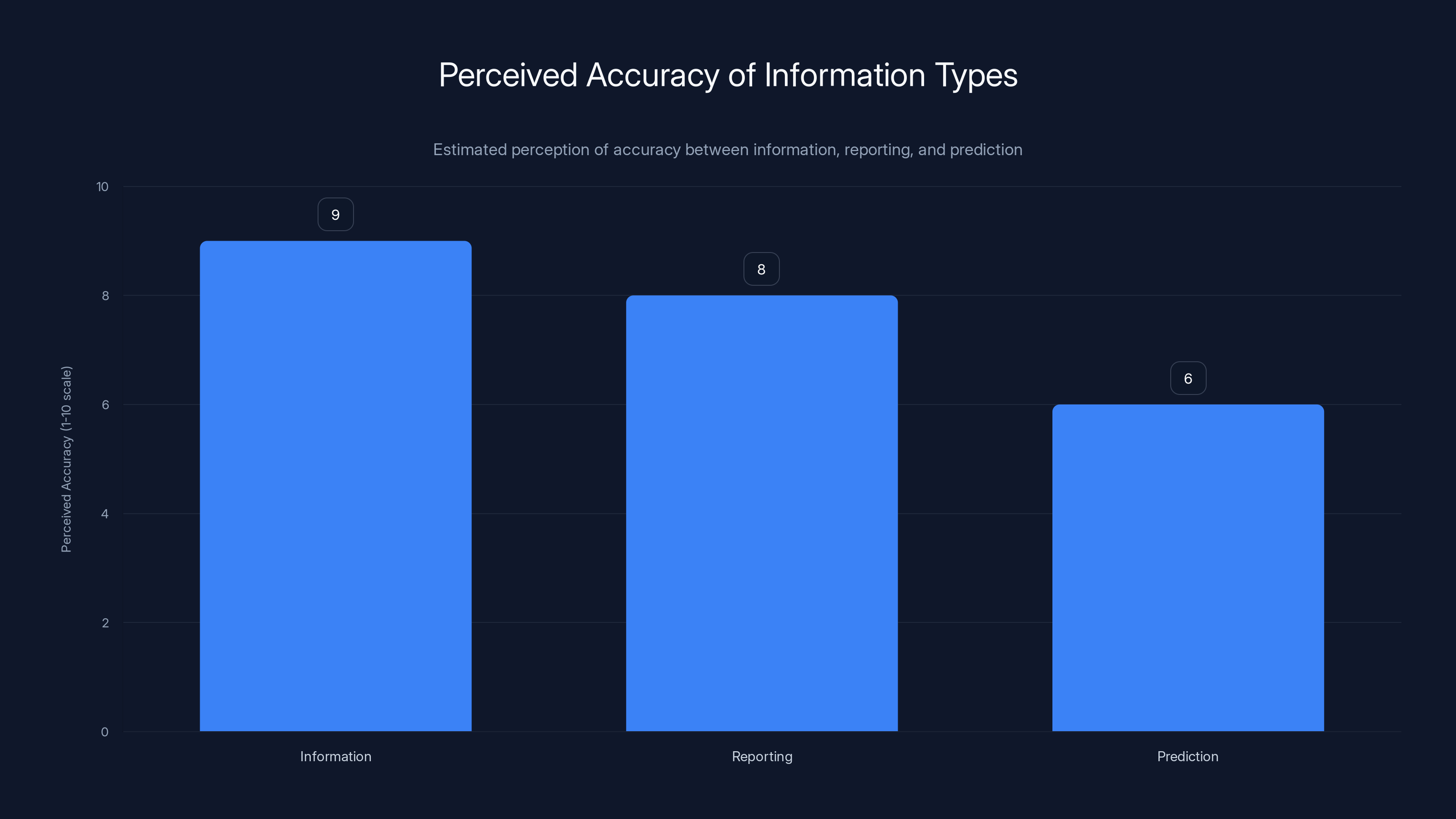

Information is perceived as most accurate, followed by reporting, with prediction viewed as less precise due to inherent uncertainty. Estimated data.

Regulatory Implications and Future Development

Current Regulatory Status in the United States

The regulatory status of prediction markets in the United States remains uncertain. The CFTC has historically exempted certain prediction markets from full regulation under the idea that they serve educational or research purposes. Polymarket has operated partially under such exemptions, though its status has been contested. Kalshi has taken a different regulatory approach, working more directly with CFTC guidance and structuring itself as a derivatives exchange.

The integration of prediction markets with major news organizations doesn't directly change their regulatory classification, but it does create political pressure around regulation. As prediction markets become more visible and more integrated into mainstream media, they gain political constituency (media companies have substantial political influence). This could influence how regulators approach these platforms in the future.

The Risk of Regulatory Capture

There's a risk that as prediction markets become more integrated with major news organizations and media brands, they could influence regulation through these associations. A regulator considering whether to impose stricter requirements on prediction markets must contend with the fact that such requirements might affect major media outlets' ability to incorporate prediction data into their coverage. This creates a form of regulatory capture where the entities being regulated gain influence over their regulators through relationships with powerful media institutions.

International Regulatory Landscape

Different countries have taken substantially different approaches to prediction market regulation. In the European Union, some prediction markets operate under betting and gambling licenses. In the United Kingdom, certain prediction markets are regulated under betting and gaming law. The global variation creates opportunities for arbitrage and regulatory shopping, where platforms locate their operations in jurisdictions with lighter-touch regulation while serving customers globally.

The Epistemological Problem: What Does "Knowing" Mean?

Information vs. Prediction vs. Reporting

At a fundamental level, this debate is about the nature of knowledge and how we constitute shared reality. Information is facts about the world that can be verified and documented. Reporting is the communication of verified information by trusted institutions. Prediction is an estimate of future likelihood based on current information and models. These are categorically different things, yet prediction market integration in news coverage conflates them.

When you read in The Wall Street Journal that "earnings are expected to increase 5% this year," that statement synthesizes multiple types of knowledge: historical data about earnings (verifiable), analyst models and predictions (estimates), and aggregated expert opinion. It's presented as a reporting statement, but it contains predictive elements. This is normal and acceptable in news coverage because journalists transparently communicate the conditional, predictive nature of such statements.

But when prediction market odds are presented alongside traditional reporting, they're often presented without this contextual framing. The odds appear as objective facts rather than as estimates with substantial uncertainty and potential bias. This subtly reshapes how audiences understand the nature of the information they're receiving.

The Probabilistic Illusion

There's something seductive about probability numbers. Statements like "75% probability" feel more precise and scientific than qualitative assessments like "likely" or "probably." Yet this precision is frequently illusory—a 75% probability that emerges from a betting market may be no more accurate or well-grounded than a journalist's assessment that something "probably" will happen. The number creates an appearance of precision that exceeds the actual knowledge being communicated.

This "probabilistic illusion" is particularly problematic when prediction market odds are reported without careful contextualization. An audience member might reasonably interpret a 65% prediction market probability as equivalent to a scientific measurement or expert consensus, when it's actually an aggregation of bets from market participants with varying expertise and information.

The Risk of Reducing Uncertainty

One of journalism's functions is to acknowledge and communicate uncertainty. Good reporting says "we don't know yet" when that's accurate. It says "experts disagree" when they do. It resists the temptation to reduce complex, uncertain situations to false certainty. Prediction markets, by their nature, convert uncertainty into probability distributions. This isn't wrong per se—sometimes quantifying uncertainty is valuable. But when integrated into news coverage without careful framing, it can create a false impression that important uncertainties have been resolved.

Consider a story about potential merger approval. The actual relevant uncertainties are numerous: Will the regulatory agencies approve it? Will the companies satisfy all conditions? Will market conditions change and make the deal less attractive? How fast will approval take? A prediction market might aggregate these into a single probability—say, 70% chance of completion. But this masks the underlying uncertainties and makes it appear that one key question has been answered when actually many uncertain questions have been compressed into a single number.

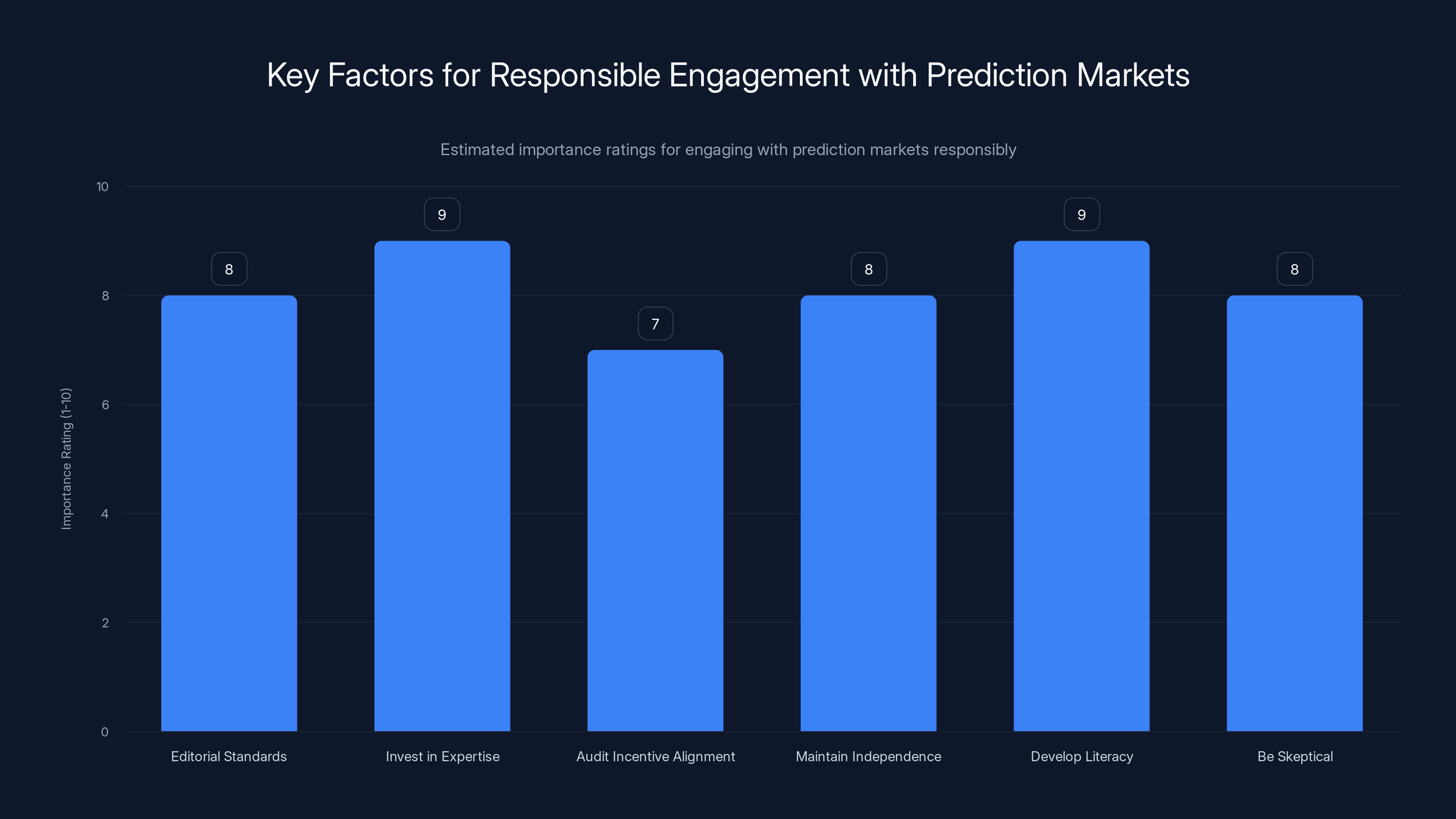

Investing in expertise and developing prediction market literacy are rated as the most important factors for responsible engagement with prediction markets. (Estimated data)

Real-World Implications: How This Affects Public Understanding

The Sophistication Gap

Not all audiences have equal sophistication in interpreting probability and understanding prediction markets. A financial industry professional might understand that betting odds reflect market sentiment and have specific limitations. A casual news consumer might simply internalize the odds as expert predictions. This sophistication gap means that prediction market integration in mainstream news has potentially different effects on different audience segments.

This creates a form of information inequality. Savvy consumers can mentally adjust for the specific properties of prediction markets and integrate that data appropriately. Less savvy consumers might treat the odds as equivalent to expert consensus or scientific measurement. News organizations have some responsibility to narrow this gap through clear communication, but the incentive structures created by prediction market partnerships work against this responsibility.

The Commodification of Uncertainty

When predictions about important events—elections, policy outcomes, business decisions—are regularly presented as betting odds, it subtly reshapes how people think about uncertainty. Uncertainty becomes something that can be wagered on, monetized, and tracked like a stock price. This isn't inherently wrong, but it can shift the cultural frame from "how can we make good decisions despite uncertainty" to "what's the market price of this uncertainty."

This shift has real consequences. When elections are presented through the lens of betting odds, they become spectacles to bet on rather than civic events to engage in. When policy outcomes are covered through prediction markets, the focus becomes what traders think will happen rather than what citizens want to happen. Over time, this reframing can reshape political and social engagement.

The Attention Distraction Effect

Prediction markets are excellent at capturing attention because odds change, creating news hooks. "Odds shift on merger approval!" is a story headline that can be generated multiple times a day. This creates substantial potential for distraction—where disproportionate news coverage focuses on what prediction markets think will happen, pulling attention away from substantive analysis of whether various outcomes would be good or bad.

For example, a story about whether a particular regulation will be approved might spend 70% of its content discussing prediction market odds and 30% discussing what the regulation would actually do. This distribution doesn't necessarily match what readers need to know to form informed opinions.

The Role of Technology and Platforms

Algorithmic Amplification of Prediction Market Content

News organizations distribute their content through multiple channels: direct websites, social media, email newsletters, and platform aggregators. Algorithmic systems that recommend content to users—whether YouTube's recommendation engine, Facebook's news feed algorithm, or Twitter's timeline algorithm—can systematically amplify certain types of content.

Prediction market coverage, with its real-time volatility and dramatic narratives ("odds surge on X"), is particularly well-suited to algorithmic amplification. A story about odds shifting is inherently more time-sensitive and attention-grabbing than a story about fundamental changes in underlying conditions. This means that algorithmic distribution could naturally amplify prediction market coverage beyond what editorial judgment would suggest, further biasing the information environment.

Data Integration and the Prediction-Journalism Complex

As prediction markets become more established and their data becomes more integrated into news systems, we could see the emergence of what might be called a "prediction-journalism complex"—deep integration between prediction markets and news organizations at the technical and organizational level. News organizations might begin licensing prediction market data in real-time, automatically updating their coverage with current odds. Headlines might be generated by algorithms that recognize when odds have moved beyond certain thresholds.

This technical integration would further entrench the cultural assumption that prediction markets are a legitimate data source equivalent to traditional reporting. It would also create substantial switching costs and economic lock-in, making it harder for news organizations to disengage even if they wanted to.

Alternatives: How News Could Engage with Predictions Better

Transparent Contextualization

News organizations can continue to report on prediction markets without the current confusion and category errors. The key is transparent contextualization. Stories could explicitly state: "Prediction market data represents the aggregated beliefs of market participants about this outcome, not a scientific forecast or expert consensus. The odds reflect current betting activity and are subject to change based on new information, market manipulation, or shifts in participant sentiment."

With this framing, prediction market data becomes a useful piece of information alongside other relevant data—polling, expert analysis, fundamental factors affecting likely outcomes. But it doesn't become a substitute for journalism or an authoritative prediction of what will happen.

Expert Validation and Scrutiny

News organizations could develop stronger relationships with forecasting experts who can critique prediction market odds and explain their limitations. Alongside reporting prediction market odds, they could report expert assessments of whether those odds seem reasonable given available information. This creates a form of editorial quality control—the news organization is explicitly taking responsibility for assessing whether the predictions being reported are credible.

Deeper Coverage of Drivers vs. Odds

Newsrooms could rebalance their coverage to spend more time on the fundamental factors driving outcomes and less time on the odds themselves. Rather than tracking odds as a running commentary, they could focus on investigating what will actually determine outcomes, explaining the relevant uncertainties, and helping audiences understand the important decisions at stake. This requires more work than simply reporting odds, but it's also more valuable journalism.

Dedicated Prediction Market Literacy

News organizations could develop expertise in explaining prediction markets themselves—how they work, what drives odds, where they've been accurate and inaccurate, what biases they're subject to. Rather than treating prediction markets as a data source to incorporate without explanation, they could be the subject of substantive reporting and analysis. This would require investment but would serve the public by building literacy about these platforms.

The Broader Transformation of Information Markets

Financialization of Information

What we're seeing with prediction market integration in news is part of a broader trend toward the financialization of information. Information becomes valuable not primarily because of its truth or its usefulness for informed decision-making, but because it can be wagered on and traded. This transformation has been happening for decades in financial markets (where vast resources are devoted to predicting prices), and it's now extending into political, social, and cultural domains.

This financialization brings both benefits and costs. On the benefit side, financial incentives can motivate information gathering and analysis. On the cost side, financial incentives can distort what gets analyzed, how it gets framed, and what serves the financial interests of those controlling the capital versus what serves the broader public interest.

The Venture Capital Model of News

Prediction market companies like Polymarket and Kalshi are venture-backed operations seeking substantial returns on invested capital. Their exit strategy likely involves regulatory approval and expansion into new markets, acquisition by larger financial firms, or public offerings. Achieving these outcomes requires demonstrating substantial growth and market potential.

Integration with major news organizations serves this growth objective. It increases brand visibility, lends legitimacy, and expands the addressable market. But this means that the news partnerships are primarily instruments of capital growth for venture-backed companies, not organic responses to journalistic need or public interest. This dynamic should be transparent and acknowledged in coverage.

The Attention Economy and Uncertainty

In the attention economy, uncertainty is a valuable commodity. Events that could go multiple ways, where the outcome is genuinely unclear, generate attention and engagement. Prediction markets thrive on this uncertainty—they profit from people wagering on unknowns. News organizations profit from engaging audiences by covering these uncertain events.

This creates an interesting dynamic: there are now businesses that profit when the future is uncertain, that benefit when people care about probability estimates, and that can afford to invest heavily in making uncertainty salient. These businesses are now deeply integrated with the institutions that shape public understanding. As this integration deepens, it's worth asking whether the informational environment is being subtly shaped to emphasize uncertainty and volatility in ways that serve financial interests rather than public understanding.

Critical Perspectives: The Voices of Skepticism

Journalist and Media Critic Perspectives

Some established journalists and media critics have raised concerns about prediction market integration. The criticism focuses on category confusion: prediction markets generate data about what traders believe will happen, not data about what will happen or what should happen. By integrating this data into news coverage without clear distinction, news organizations blur the line between reporting (what has happened) and speculation (what might happen).

This criticism is particularly sharp regarding political coverage, where prediction market integration can subtly shift framing from "what do voters want" to "what do traders expect voters will do." These are fundamentally different questions with different normative weight, but in coverage dominated by prediction market odds, they can become conflated.

Academic Research on Market Efficiency

Academic researchers studying prediction markets have documented numerous failure modes, limitations, and conditions under which markets perform poorly. The academic literature is substantially more cautious about prediction market accuracy than the promotional rhetoric surrounding these platforms. Yet news organizations often report on prediction markets as if the academic consensus were more positive than it actually is.

Regulatory and Legal Concerns

Regulatory agencies and some legal scholars have raised concerns about whether prediction markets serve legitimate purposes or primarily function as gambling platforms. The integration with news organizations doesn't resolve these underlying regulatory questions; it simply makes the platforms more visible and potentially influences regulatory outcomes through media prominence and political pressure.

What About Tools Like Runable? Alternative Approaches to Information

As the media landscape becomes increasingly complex, with traditional journalism under financial pressure and new platforms competing for attention and audience, it's worth considering what alternative approaches to information organization and dissemination might look like. While Runable operates in a different space—focused on AI-powered automation and content generation—its existence points to a broader category of tools that could reshape how organizations handle information.

Runable's approach to workflow automation and AI-driven content generation represents a different model for information handling than what prediction markets offer. Rather than trying to monetize uncertainty and speculation, platforms like Runable focus on automating information work—generating reports, creating presentations, organizing data, managing workflows. For news organizations looking to increase efficiency without compromising editorial standards, tools like Runable could provide alternatives to simply incorporating external data sources like prediction markets.

Where prediction markets commodify uncertainty, automation tools commodify routine information work. A news organization using Runable's AI capabilities could potentially handle more stories with fewer resources, focusing human journalists on analysis, investigation, and judgment while automating routine production tasks. This is philosophically different from the prediction market model—it's about enhancing journalism through efficiency rather than replacing journalism with speculation.

For teams and organizations building modern content operations, Runable offers features like AI-powered document generation, automated workflows, and developer tools that could help manage the increasing volume of information and content they need to process. The platform's pricing model ($9/month) is also substantially different from the venture-backed, growth-obsessed model of prediction market companies, which suggests different long-term incentive structures.

While Runable isn't a substitute for the journalistic issues raised by prediction market integration, it represents an alternative philosophy: enhancing human capabilities through automation and efficiency, rather than replacing human judgment with market-generated probabilities.

Recommendations: How to Engage with Prediction Markets Responsibly

For News Organizations

Establish clear editorial standards for prediction market coverage. If your organization chooses to incorporate prediction market data, develop explicit guidelines about when and how to do so. Prediction market odds should be labeled clearly as such, distinguished from polling, expert consensus, or scientific forecasts. They should be contextualized with information about their limitations, track record, and potential biases.

Invest in expertise. Rather than simply reporting betting odds, develop in-house expertise about prediction markets, how they work, what drives them, and what their limitations are. This expertise should inform coverage decisions and provide readers with substantive information about these platforms.

Audit incentive alignment. Examine whether the integration of prediction market data into your coverage is being driven by editorial judgment about what serves readers, or by engagement metrics and audience growth. If prediction market coverage is disproportionately rewarded by algorithms and analytics, that's a sign to be cautious about over-reliance on this data source.

Maintain editorial independence. Be cautious about relationships with prediction market companies that go beyond simple data access. Speaking engagements, advisory roles, or other forms of entanglement create conflicts of interest that can subtly bias coverage.

For Readers and Audiences

Develop prediction market literacy. Understand what prediction markets are, how they work, and what determines their outputs. Recognize that betting odds are not equivalent to expert predictions or scientific forecasts. They're aggregations of financial bets made by people with varying expertise and information.

Be skeptical of certainty masquerading as probability. When you encounter prediction market odds presented as a key fact in news coverage, think about what's actually being communicated. A 75% probability is still saying that a 25% alternative is possible—substantial uncertainty remains.

Question the narrative framing. When a news story emphasizes prediction market odds, ask whether that's the most important or relevant information about the situation. Would understanding fundamental factors, expert analysis, or different perspectives be more valuable?

Demand transparency. If news organizations use prediction market data, they should clearly explain what it is, where it comes from, what it represents, and what its limitations are. If coverage doesn't provide this transparency, it's worth questioning why.

For Regulators and Policymakers

Maintain skepticism of claims about innovation and legitimacy. The integration of prediction markets with news organizations doesn't resolve underlying questions about whether these platforms serve the public interest or primarily generate profits for their operators. Business arguments about innovation shouldn't override concerns about accuracy, fairness, and manipulation potential.

Scrutinize regulatory capture. Be alert to ways that prediction market companies, through partnerships with major media outlets, might influence regulatory decisions. The fact that a platform is used by major news organizations shouldn't automatically increase its regulatory legitimacy if underlying concerns about its operation remain valid.

Support prediction market literacy. Investment in public understanding of how prediction markets work, what drives them, and what their limitations are would serve the public interest and make audiences more resistant to confusion and manipulation.

The Deeper Stakes: What's Actually at Risk

The integration of prediction markets into news coverage might seem like a technical question about data sources. But it's actually a question about the nature of shared reality, how societies constitute knowledge, and who gets to define what counts as reliable information. These are fundamental questions that have been implicitly resolved in the post-WWII era through a rough consensus around journalistic institutions as knowledge-arbiters.

That consensus is fraying. News organizations are under financial pressure, public trust in institutions is declining, and new information sources (social media, alternative platforms) are competing with traditional journalism. In this environment, prediction markets offer an appealing solution: objective, quantifiable, continuously updated information about the future. But this appeal rests on a misunderstanding of what prediction markets actually provide and what journalism actually does.

What's at stake is not merely whether odds are accurate (they sometimes are, sometimes aren't). What's at stake is whether societies can maintain institutions dedicated to establishing shared facts about the world, or whether such facts will be increasingly crowded out by speculation, prediction, and wagering. A world where what you can bet on matters more than what actually happened is a fundamentally different kind of world. We should be thoughtful about drifting into it without explicitly choosing to do so.

Conclusion: Clarity, Caution, and the Future of Information

Prediction markets are genuinely interesting phenomena. They aggregate information in ways that can sometimes produce surprisingly accurate forecasts. They raise important questions about how we model uncertainty and make decisions when outcomes are unknown. There's legitimate value in understanding what market participants believe will happen, and what odds are being assigned to various outcomes. But this value exists alongside an important recognition: market-generated probabilities are not news, and betting markets are not journalism.

The strategic integration of prediction markets with major news outlets—Polymarket with Dow Jones and the Wall Street Journal, Kalshi with CNN and CNBC—represents a watershed moment. These partnerships, if they become the norm rather than the exception, will have consequences for how societies understand themselves and make collective decisions. Those consequences could be broadly positive if the integration is done thoughtfully, with full transparency about what prediction markets are and what their limitations are. But the current trajectory suggests something different: a quiet, incremental conflation of categories, driven by economic incentives that favor engagement and speculation over accuracy and understanding.

The most important thing audiences, journalists, and policymakers can do is maintain clarity about what prediction markets are and aren't. They are aggregations of bets made by people with varying expertise. They are sometimes accurate, sometimes dramatically wrong. They can be manipulated, and they can be biased by asymmetric information and herding dynamics. They tell us what traders think will happen, but not what should happen, what citizens want to happen, or what experts believe will happen. They are a data source worth paying attention to, but not a replacement for journalism, expertise, or democratic deliberation.

As prediction markets become increasingly integrated into the media landscape, the question is whether this integration will be done transparently and responsibly, or whether it will subtly reshape how we understand the world without explicit public discussion or understanding. The answer depends on choices being made right now by news organizations, by regulators, and by the public. Those choices deserve careful attention, thoughtful scrutiny, and explicit discussion about what kind of informational environment we want to inhabit and how we want to constitute our shared understanding of reality.

The future of journalism depends not on resisting innovation or new data sources, but on maintaining clarity about what journalism is and what it's for. A news organization can report on prediction markets and incorporate their data without losing sight of its core mission: establishing reliable facts about the world and helping audiences understand what happened and why it matters. The challenge is doing both at once—engaging with prediction markets as an interesting phenomenon without mistaking them for reporting, and serving audiences honestly in an increasingly complex information environment.

In the end, this is a story about incentives, about business models, and about the cultural assumptions we make about what counts as knowledge. It's a story where we still have agency, where we can still make choices about what kind of information environment we want and how we want it structured. But that agency is time-limited. Once certain assumptions become embedded in institutional practice, once audiences become habituated to certain ways of understanding information, change becomes harder. Now is the moment for explicit choices about whether prediction markets should be integrated into journalism, on what terms, with what transparency, and for what purposes. The next few years will likely determine whether that integration happens thoughtfully or by default.

FAQ

What is a prediction market and how does it differ from traditional journalism?

A prediction market is a platform where participants wager money on the likelihood of future events. Unlike journalism, which documents events that have already happened and maintains editorial standards for accuracy and verification, prediction markets aggregate bets from participants to create probability estimates of future outcomes. Prediction markets generate odds based on financial incentives, while journalism generates reporting based on investigation and verification. These are fundamentally different information systems serving different purposes, though they increasingly overlap in media coverage.

How do Polymarket and Kalshi make money from their partnerships with news organizations?

Polymarket and Kalshi generate revenue primarily through transaction fees—they take a percentage (typically 2-5%) of all bets placed on their platforms. When news organizations regularly report on prediction market odds, it drives audience interest, which increases engagement with the platforms and generates more betting volume, thereby increasing commission revenue. The partnerships also increase brand visibility and credibility for the prediction market companies, which can support growth objectives and valuations important to venture-backed operations.

Are prediction markets actually accurate at forecasting future events?

Prediction markets have demonstrated accuracy on certain types of events, particularly high-stakes political and sporting outcomes, but they have substantial limitations. They depend entirely on the quality of available information, are vulnerable to manipulation and herding effects, and have performed poorly during surprise events that contradict historical patterns. Their accuracy also varies significantly based on whether participants have relevant expertise and access to good information. Unlike scientific forecasts or expert predictions, betting odds are influenced by financial incentives and participant behavior, not just underlying probabilities.

Why is integrating prediction market data into news coverage problematic if the odds are sometimes accurate?

Accuracy is not the primary concern. The issue is conceptual clarity—prediction markets provide speculative information about what might happen, while journalism documents what has happened. When news organizations present betting odds alongside traditional reporting without clear distinction, they blur this fundamental difference. This can mislead audiences about how much is actually known, what counts as reliable information, and whether consensus or speculation is being reported. Additionally, presentation of odds can shift focus from substantive analysis to dramatic narrative, and incentivizes coverage of events with high betting volume rather than highest public importance.

What are the conflicts of interest when news organizations incorporate prediction market data?

Multiple conflicts exist: news organizations benefit from audience engagement driven by prediction market coverage; prediction market platforms benefit from news coverage that increases betting volume; and journalists may face subtle pressure (through engagement metrics and editorial encouragement) to emphasize prediction market content. Additionally, news organizations that partner with prediction market companies develop financial relationships that could bias editorial judgment. Regulators examining prediction markets may give them more credibility if they're integrated with major media outlets, which benefits the platforms while potentially influencing regulatory decisions inappropriately.

How can news organizations report on prediction markets responsibly?

Responsible coverage requires transparent contextualization: clearly labeling odds as such, distinguishing them from polling data or expert consensus, explaining how prediction markets work and what drives their outputs, and acknowledging their limitations and failure modes. Organizations should develop in-house expertise about prediction markets rather than simply reporting odds. Coverage should emphasize fundamental factors and substantive analysis over tracking odds changes. Editorial standards should ensure that prediction market data is incorporated because it serves readers, not because engagement metrics reward its coverage. Relationships with prediction market companies should be limited and transparent.

What role do algorithmic platforms play in amplifying prediction market coverage?

Algorithmic systems that recommend content—YouTube's recommendation engine, social media feeds, news aggregators—tend to amplify content that generates engagement through drama and novelty. Stories about odds shifting or probabilities changing are particularly well-suited to algorithmic amplification because they're time-sensitive and emotionally engaging. This means that algorithmic distribution can naturally amplify prediction market coverage beyond what editorial judgment would suggest, biasing the information environment toward speculation and volatility. This dynamic is largely invisible but powerful in shaping what audiences see and what topics dominate public conversation.

How has prediction market integration changed political coverage specifically?

Integration has shifted political coverage toward emphasizing what traders expect will happen rather than focusing on substantive issues, policy differences, or voter preferences. Election coverage now regularly includes betting odds alongside traditional polling, sometimes giving odds equal or greater prominence. This can subtly frame elections as spectacles to bet on rather than civic events to engage in. Additionally, prediction market coverage can overemphasize volatility and dramatic odds changes while underemphasizing the underlying fundamental factors that should actually drive political outcomes and voter decisions.

What regulatory concerns exist around prediction markets and their media integration?

Regulatory concerns include the basic question of whether prediction markets serve public purposes or primarily function as gambling platforms. There's also concern about regulatory capture—when prediction market platforms gain credibility and political constituency through media partnerships, regulators may feel pressure to be less stringent. The fact that platforms operate in regulatory grey zones (particularly in the U. S.) and use media integration to establish legitimacy raises questions about whether they should be treated as legitimate information services rather than financial instruments subject to existing gambling and derivatives regulations.

What alternatives exist to prediction market integration for news organizations seeking innovative data sources?

Alternatives include investing more in data journalism and statistical literacy to better explain uncertainty and probability; developing stronger relationships with forecasting experts who can validate or critique claims; focusing on fundamental analysis rather than tracking speculative odds; and using automation tools to handle routine information work more efficiently, freeing resources for substantive journalism. Organizations can also develop prediction market literacy—reporting on how these platforms work, when they've been accurate or inaccurate, and how they differ from other forecasting methods. This educates audiences while maintaining journalistic standards for verification and transparency.

Key Takeaways

- Prediction markets are aggregations of financial bets, not journalism or expert predictions

- Major news organizations have integrated prediction market data (Polymarket/Kalshi) into regular coverage alongside traditional reporting

- This integration blurs fundamental distinctions between documenting what happened versus speculating about what might happen

- Economic incentives drive prediction market integration: platforms profit from betting volume, news organizations profit from engagement

- Prediction market accuracy varies substantially and depends on information quality, expert knowledge, and vulnerability to manipulation

- Integration with news outlets provides prediction markets with credibility and regulatory legitimacy they would otherwise lack

- Responsible coverage requires transparent contextualization, clear distinction from other information types, and rigorous examination of limitations

- Algorithmic amplification naturally favors prediction market coverage because odds changes generate drama and engagement

- Public understanding depends on clear media literacy about what markets are, how they work, and what their limitations are

Related Articles

- Prediction Markets Regulation Battle: Senate vs CFTC [2025]

- Polymarket's $408K Maduro Bet Exposes Prediction Market Insider Trading Problem [2025]

- Why Bezos Abandoned the Washington Post's Newsroom [2025]

- New York's AI Regulation Bills: What They Mean for Tech [2025]

- Washington Post CEO Crisis: What Jeff D'Onofrio's Appointment Means for Media [2025]

- 2026 Winter Olympics Sports Betting: Integrity, Growth & Future