Why Bezos Abandoned the Washington Post's Newsroom [2025]

There's a moment in every business story where you realize the actual issue isn't what anyone's talking about. The Washington Post's recent gutting of its local news and sports desks looked like a straightforward cost-cutting move. But buried in the chaos was something far more revealing: a deal that could have kept hundreds of journalists employed. A deal that never happened.

In late January 2025, as the Post began eyeing elimination of its sports desk, the Washington City Paper—a scrappy, locally-rooted publication with deep DC connections—quietly approached then-CEO Will Lewis with a proposal. Mark Ein, owner of City Paper and part-owner of the Washington Commanders, had a solution: spin off the Post's sports and local sections into a separate entity that City Paper would invest in and host. It wasn't a bailout. It was a structural fix that would have cost Bezos nothing.

Lewis reportedly seemed receptive. The conversations continued for weeks. Then, last Wednesday, the Post closed both desks entirely and laid off everyone who worked there. The sports journalists were literally in the middle of covering the Winter Olympics and preparing for Super Bowl coverage.

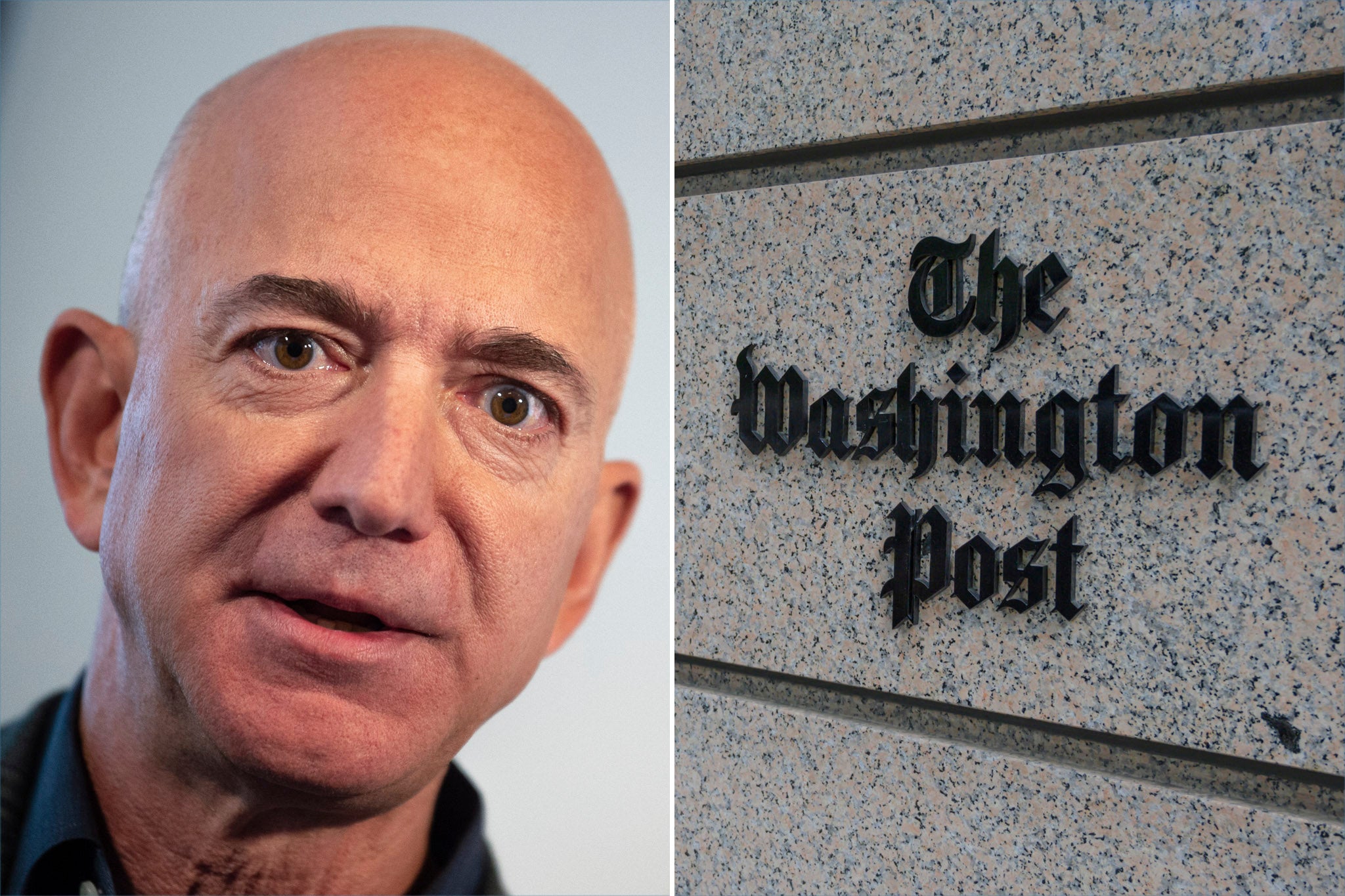

This story matters because it reveals something uncomfortable about billionaire ownership of newspapers. It's not about whether billionaires want to destroy journalism (most don't). It's about whether they're willing to do the unglamorous work of actually saving it. Bezos isn't a villain here. But his absence—his unwillingness to pick up the phone, engage with a creative solution, or even delegate someone to manage a conversation—tells you everything about how legacy media became so fragile.

TL; DR

- The Missed Deal: The Washington City Paper offered to acquire the Post's sports and local sections, keeping 400+ journalists employed. CEO Will Lewis seemed receptive, then abruptly closed both desks instead.

- Bezos's Absence: While the Post laid off reporters mid-Olympic coverage, Bezos remained uninvolved in negotiations. No phone calls. No engagement. Just cuts.

- Structural Problem: This wasn't about money. City Paper had the capital. It was about a billionaire owner treating a newspaper like a spreadsheet rather than a civic institution.

- Industry Pattern: The Post's decision mirrors broader failures in legacy media ownership, where deep-pocketed owners prioritize "rationalization" over journalism.

- The Real Cost: Local newsrooms across America continue to collapse while potential solutions—like the City Paper model—never reach decision-makers.

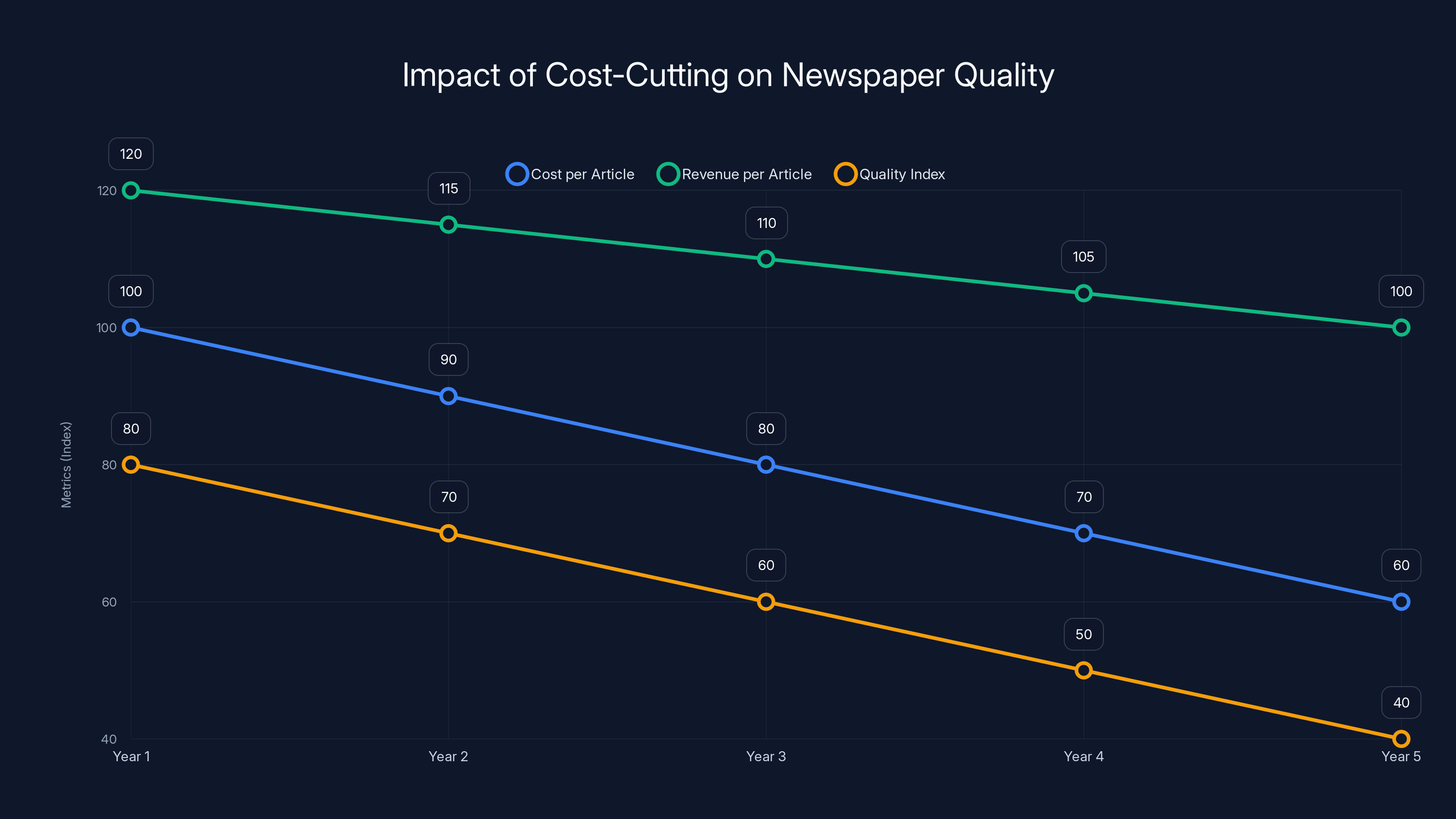

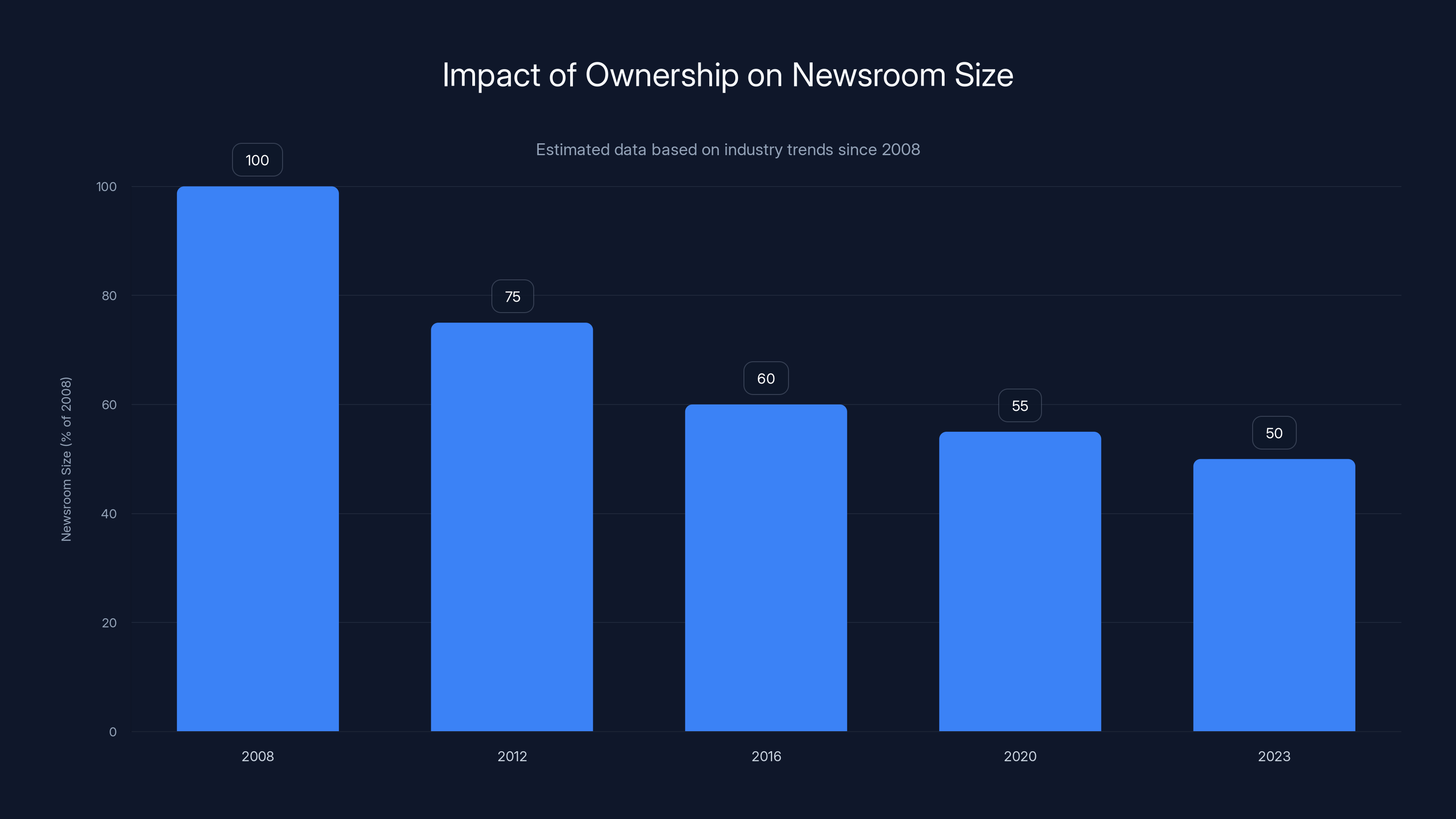

Estimated data shows that while cost-cutting improves financial metrics, it leads to a decline in newspaper quality over time. Engaged ownership could mitigate this trend.

The Washington Post's Identity Crisis

Understanding this story requires context on what the Washington Post actually is. It's not just another newspaper. For generations, it's been the heartbeat of Washington journalism. The Post's local reporting defined the city's political culture. Its sports coverage was legendary—the kind of beat reporting that turned local teams into civic institutions.

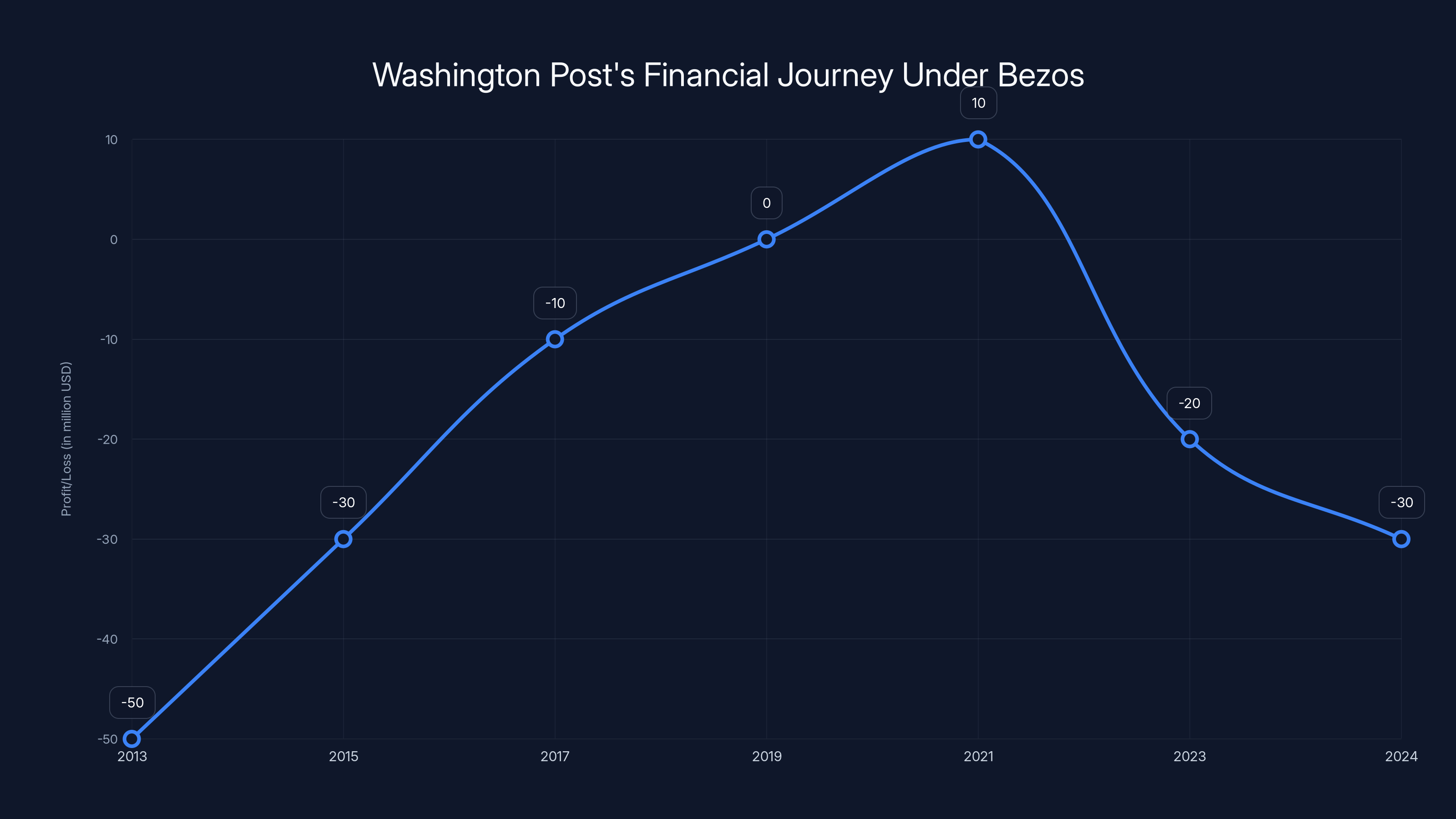

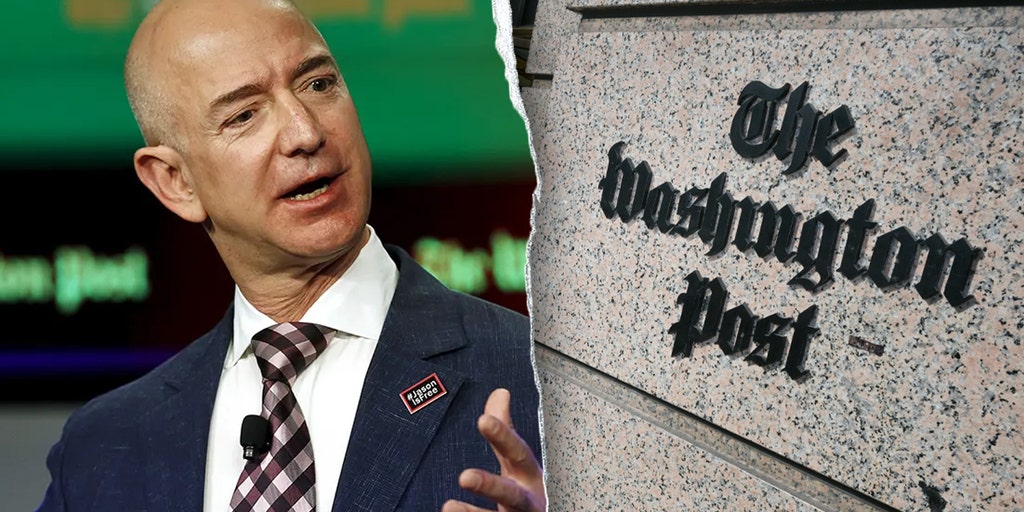

When Bezos bought the Post in 2013 for $250 million, the narrative was clear: a tech billionaire would rescue legacy media with capital and innovation. It was the kind of story everyone wanted to believe. Bezos wasn't taking over for profit (he actually lost money on it for years). He seemed genuinely interested in proving newspapers could survive in the digital age.

But "survive" and "thrive" are different things. By 2024, the Post had undergone multiple transformations. Bezos installed new leadership. The paper experimented with paywalls, memberships, and digital-first strategies. Some of it worked. Some of it didn't. The fundamental problem—that legacy newsrooms are expensive and unpredictable—never went away.

Then came Will Lewis. Hired from the Financial Times, Lewis arrived with a mandate: stabilize the business. Make it profitable. Stop the annual budget increases. His strategy was straightforward: cut costs aggressively and hope the remaining newsroom could do more with less.

It didn't work, obviously. Instead, it created the situation we're discussing now.

The City Paper Proposal: How It Could Have Worked

Here's what makes the City Paper proposal clever—and here's why its rejection is so revealing. Mark Ein didn't walk into the Post with a charity pitch. He brought a business model.

The idea was this: the Post's sports desk and local news desk are expensive. They require specialized reporters, editors, photographers, and production staff. They also generate complicated revenue streams. Some advertising. Some subscriptions. But they also create institutional loyalty—readers who open the Post specifically to see what's happening with the Commanders or the mayor's office.

City Paper, by contrast, has deep local credibility but limited resources. It can't afford to rebuild a sports section from scratch. But it could absorb the Post's existing operations, maintain quality, and find new revenue models through hyperlocal sponsorships, events, and community engagement.

The proposed structure would have worked like this: Post divests sports and local desks. City Paper acquires the journalists and IP. City Paper hosts the content on its digital platform. Ein's capital funds the operation while it finds sustainable revenue. The Post reduces its cost structure. City Paper gains institutional credibility and reader audience.

Everyone benefits. The journalists stay employed. Readers keep getting coverage. The Post becomes leaner. City Paper becomes a serious player in DC media.

Lewis apparently understood this. Sources close to the discussion said he was receptive. They had weeks of conversations. There was momentum.

Then it stopped. No negotiation. No counter-proposal. The Post simply announced the closures and executed the layoffs.

The Washington Post saw fluctuating financial performance under Bezos, with brief profitability around 2021 before returning to losses. (Estimated data)

Where Was Bezos?

This is where the story gets strange. Throughout the entire process—the proposal, the conversations, the negotiations, the decision—Bezos himself was nowhere in the narrative. He didn't approve the deal. He didn't reject it. He apparently wasn't even consulted.

Instead, the Post was operating under a leadership structure where a CEO hired to "stabilize" the business had unilateral power to make decisions about its fundamental direction. Lewis didn't need approval from Bezos to close desks. He didn't need to run the City Paper proposal up the chain. He just needed to execute his mandate.

This reveals a critical gap in billionaire media ownership. Bezos talks about supporting quality journalism. He's made that claim repeatedly. But he's also built a corporate structure where he doesn't have to engage with decisions about what journalism gets supported and what doesn't. He's abstracted himself from the work.

As one journalism executive told me: "Billionaires who own media properties don't want to write more checks. They think the subsidy they're providing is that they're not asking the paper to send them a check every year. All their other businesses give them dividends, right? But this one, they're like, Fine. Just don't lose money, and just don't bug me anymore. They're trying to rationalize the business by making it lose less money."

That's exactly what happened here. Lewis was hired to "rationalize" the business. He did his job. The fact that rationalization destroyed institutional newsroom capacity? That's someone else's problem.

The Human Cost: Journalists in the Olympics

Let's be specific about what this abstraction cost. The Post's sports journalists weren't fired during a slow news cycle. They were terminated in the middle of Olympic coverage. Some had already filed stories from Beijing. Others had planned travel for Super Bowl coverage. The reporting calendar had been built months in advance.

Cutting them mid-assignment wasn't a business decision. It was a notification of irrelevance. We don't care what stories you were working on. We don't care about your readers. We don't care about the logical continuity of your work. You're expenses. Expenses get cut.

For the readers, the impact was similarly jarring. A generation of DC sports fans had grown up on the Post's local team coverage. The beat reporters who covered the Commanders, the Nationals, the Wizards, and DC United weren't just journalists—they were institutional knowledge. They had relationships with players, coaches, and front offices. They understood the city's relationship with its teams in a way that no outsider could replicate.

Once they're gone, you can't easily get them back. The knowledge walks out the door. The relationships dissipate. New journalists would have to spend years rebuilding what was lost in weeks of cuts.

Why the Decision Abruptly Reversed

What exactly happened in that final week? Why did conversations that seemed productive simply stop?

The official story is that the Post decided to move forward with cuts as part of a broader restructuring. But that doesn't explain the timing. If the decision was already made, why did Lewis appear receptive to the City Paper proposal? Why didn't he simply tell Ein "We've already committed to closing these desks"?

One possibility: Lewis thought he had approval from above to negotiate but discovered he didn't. Someone senior—maybe someone close to Bezos—said no more discussions. Just cut and move on.

Another possibility: The numbers didn't work in Lewis's favor. If he reported to Bezos that the Post could divest sports and local and reduce expenses while maintaining quality, Bezos would have incentive to approve it. But if Lewis was already committed to deeper cuts across the board, divestment would complicate his mandate. It would require him to admit that the divisions he was cutting were valuable enough for someone else to buy.

Most likely: It was simpler and messier than that. Lewis was moving fast, making decisions without full organizational alignment, and when it came time to finalize conversations with Ein, it became clear that different people in the organization had different expectations. Rather than resolve that, they just executed the cuts and moved on.

This is what happens when media organizations are managed like technology companies. Move fast. Cut deeply. Sort out the details later. It works for software. It doesn't work for newsrooms.

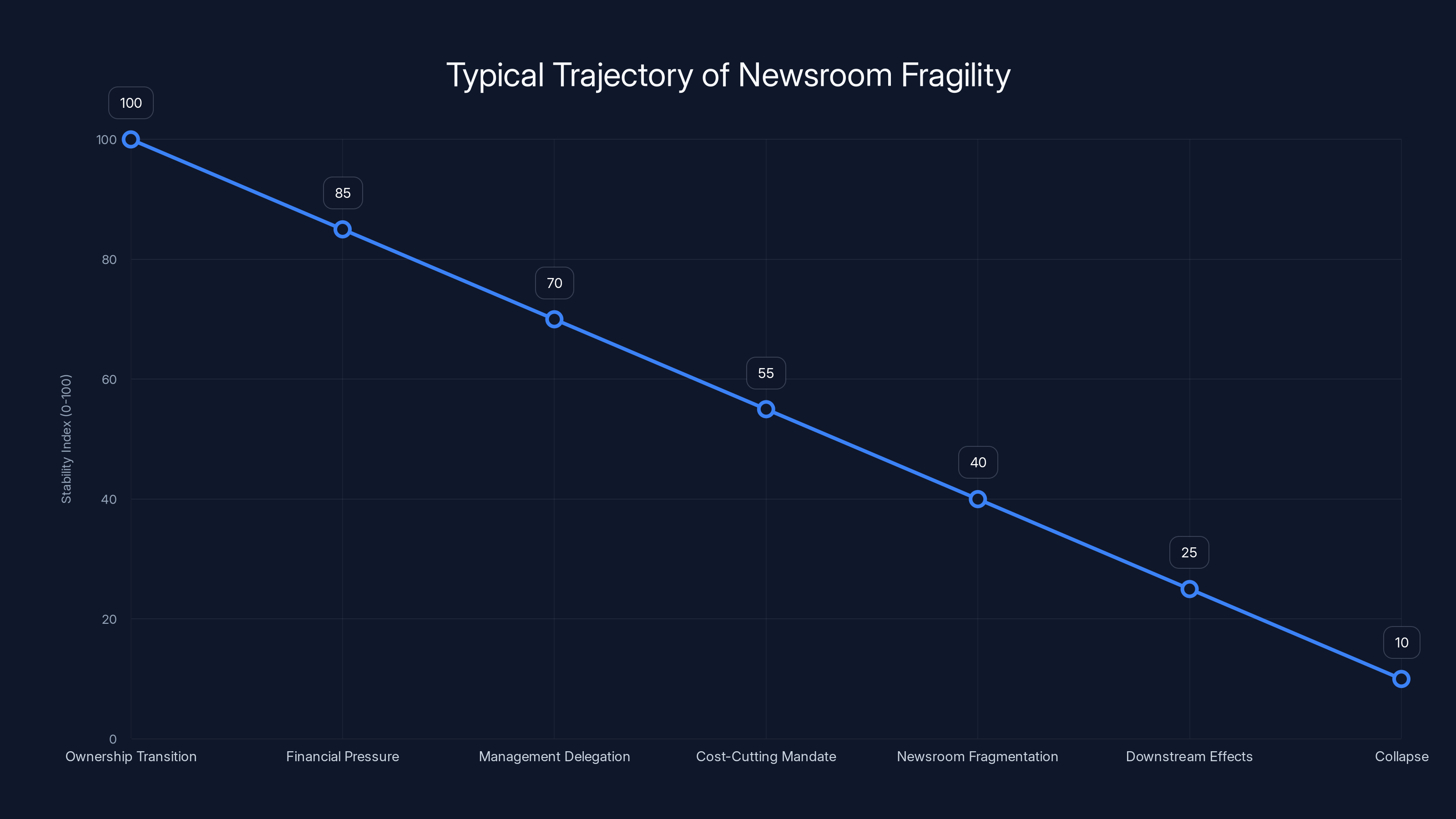

Estimated data shows a decline in newsroom stability through typical stages of financial and managerial challenges.

The Structural Problem: How Newsrooms Become Fragile

The Post's crisis isn't unique. It's a pattern we've seen at major newspapers across the country. And the pattern usually looks like this:

- Ownership transition: A billionaire buys the paper with good intentions and genuine interest in journalism.

- Financial pressure: The paper isn't profitable, and the owner grows tired of the annual losses.

- Management delegation: Rather than engage directly with journalism questions, the owner hires a CEO to "fix" things.

- Cost-cutting mandate: The CEO interprets "fix" as "reduce expenses" and starts cutting ruthlessly.

- Newsroom fragmentation: Desks close. Journalists leave. Institutional knowledge evaporates.

- Downstream effects: Reader engagement declines because coverage quality drops. Revenue shrinks. More cuts are justified.

- Collapse: The paper becomes a fraction of what it was.

At each step, there's a moment where a different decision could redirect the trajectory. Bezos could have stayed engaged. Lewis could have prioritized quality partnerships over clean cuts. The board could have pushed back on aggressive timelines. But at each moment, the path of least resistance leads downward.

The Post is large and well-capitalized enough to survive this process. It won't disappear. But it will be diminished. Readers will notice the sports coverage gets thinner. Local reporting becomes spotty. The institution that defined Washington journalism gradually becomes a shadow of itself.

And that happens not because anyone made a dramatic decision to destroy the Post, but because everyone made sensible decisions to optimize in the short term.

What the City Paper Approach Suggests About Alternative Models

The City Paper proposal is valuable because it suggests what differently-structured media ownership could look like. Instead of a single large institution trying to do everything, you'd have modular units where different organizations focus on what they do best.

City Paper's strengths are hyperlocal credibility, community relationships, and scrappy digital innovation. Those don't map directly onto the Post's national scale or investigative infrastructure. But they map perfectly onto local sports and government coverage.

The Post's strengths are resources, institutional credibility, and audience scale. It doesn't need to maintain a sports desk to keep those. It could divest the desk and focus on what it does uniquely—national politics, investigations, opinion.

This modular approach would have been better for readers (City Paper would likely do more interesting local coverage than the Post's centralized sports desk). It would have been better for journalists (they'd keep their jobs). It would have been better for the Post (lower costs, clearer focus). It would have been better for City Paper (access to a larger audience and established beat structure).

The only person it wasn't clearly better for was Will Lewis, because it would have complicated his narrative of unilateral cost-cutting and made him coordinate across organizations. Easier to just cut everything and call it "tough decisions."

Why Billionaires Keep Making the Same Mistake

Bezos isn't the first billionaire to buy a newspaper with good intentions and then gradually abstract himself from the difficult work of making it succeed. It happens repeatedly. The pattern is so consistent that you start to understand it's not accident—it's structural.

Billionaires have capital and good intentions. They buy newspapers to support journalism. But they also have other businesses that require attention. Amazon has quarterly earnings calls. They have board meetings. They have investors who demand growth. A newspaper that loses $50 million a year is an understandable luxury for a billionaire, but it's not a priority.

So they hire someone to manage it. That person's job is to improve the financials. The most direct path to improved financials is reduced expenses. So they cut. When readers complain, when journalists leave, when coverage quality declines, the billionaire owner looks at the metrics and sees: good, the business is more stable now. The margin is tighter. We're approaching breakeven.

What the billionaire can't see directly—because they've abstracted themselves from it—is what's been lost. The newsroom can't investigate the way it used to because the reporters are doing three jobs each. The sports desk can't follow teams through the season because they're working freelance gigs to supplement income. The local coverage is three-day-old wire copy because nobody's available to do reporting.

But this happens gradually, in metrics. The cost per article goes down. The revenue per article fluctuates but generally decreases. On a spreadsheet, the business looks like it's improving. In reality, it's hollowing out.

Bezos could have prevented this. He could have stayed engaged. He could have questioned Lewis about the City Paper proposal. He could have said, "Wait—if someone's willing to buy these desks and keep the journalists, why are we rejecting that?" But that would have required attention, conversation, and engagement. It's easier to let someone else make the decisions.

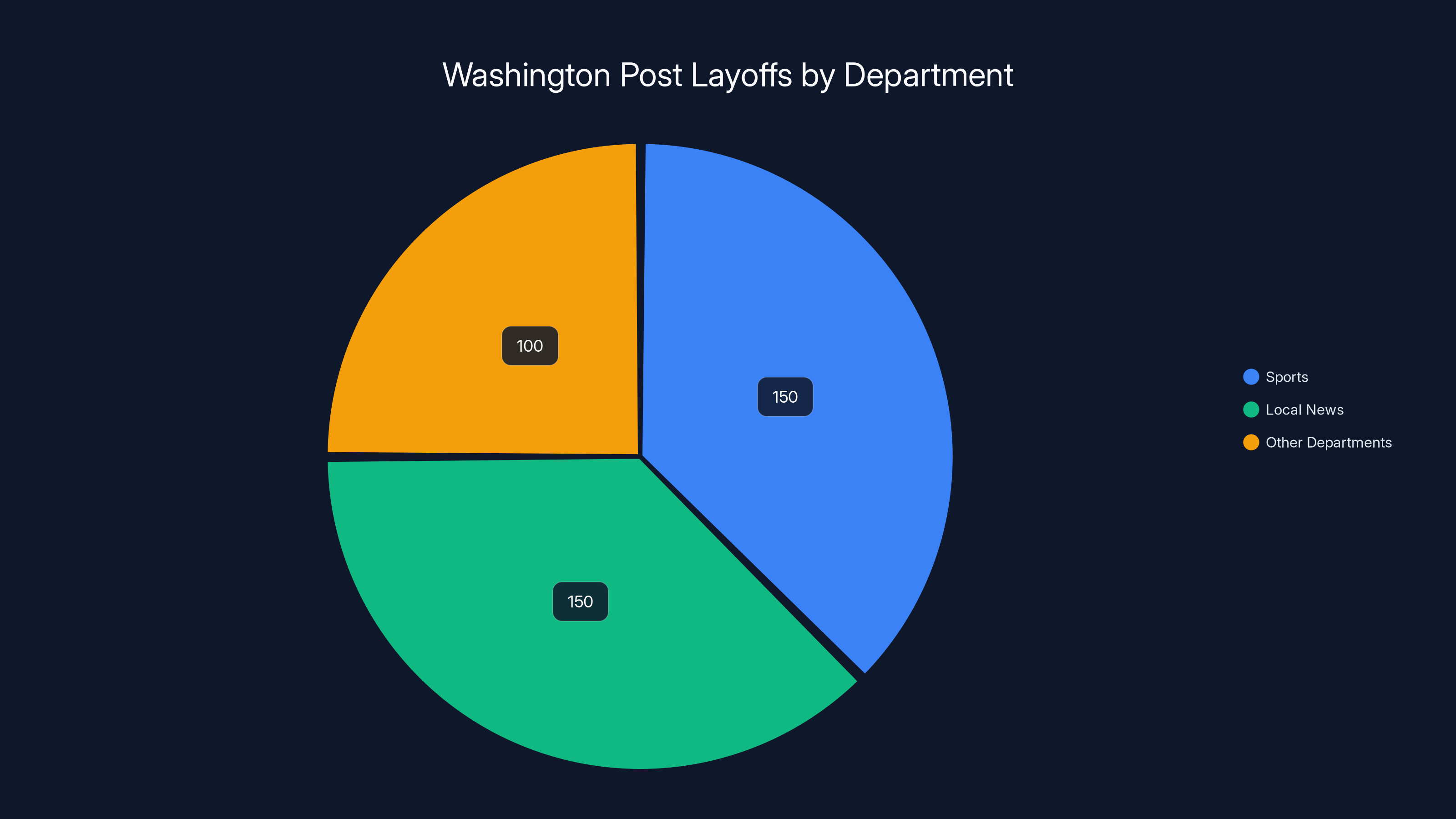

Estimated data suggests that sports and local news departments were equally affected, each accounting for around 150 of the 400 total layoffs.

The Wider Industry Crisis: Why Local News Keeps Collapsing

The Post's situation is extreme because the Post is a large institution with significant resources. But the underlying dynamics—billionaire ownership leading to slow abstraction and eventual gutting—are happening at smaller scale across the country.

Los Angeles Times. San Francisco Chronicle. Denver Post. Miami Herald. Each has gone through similar cycles. Each has been owned by billionaires or large media conglomerates that gradually extracted value rather than investing it.

The common thread: journalism requires investment and attention. Cost-cutting always seems smarter in the short term. But it's a ratcheting mechanism. Once you cut reporters, you can't easily hire them back (they've moved on, the knowledge is gone, your budget is locked). So the next year you cut again. Then the next year. Eventually you reach a point where the newsroom can't produce the journalism that made it valuable in the first place.

Local News is particularly vulnerable because it's harder to monetize than national news. People will pay for "New York Times" or "Wall Street Journal" because the reporting is valuable and not available elsewhere. But local news? Readers assume it's free. They get it from their local news website, or Facebook, or random blogs.

This creates a revenue problem that cost-cutting can't fix. You can't cut your way to profitability if your revenue model is broken. But every media CEO tries anyway. It's the only lever they can actually pull.

What Happened to the Journalists

Mark Ein said publicly that he was "on it"—meaning the City Paper would try to hire the Post's reporters. But that's harder than it sounds. The journalists were suddenly unemployed. They needed income immediately. Some would take freelance gigs with national outlets. Others would move to different cities for jobs. Some would leave journalism entirely.

City Paper could potentially hire some of them back, but not all. The budget doesn't exist for 400 journalists. More likely: City Paper hires 20-30 of the best reporters and editors, and the rest scatter.

That's the human cost of this decision. Individual lives disrupted. Families relocating. Careers redirected. And the question "why was this necessary?" hanging over all of it.

The Structural Fix That Could Have Prevented This

Let's imagine a different scenario. Bezos, when hiring Lewis, had included explicit guidance: "Find ways to improve the business without destroying its journalism capacity. If you want to cut desks, make sure those desks go somewhere where they can continue doing their work."

With that guidance, Lewis's conversation with Ein would have gone differently. Instead of stopping abruptly, the negotiations would have continued. They would have worked out details. The City Paper would have acquired sports and local. Both organizations would have announced the transition as a strategic restructuring.

The Post saves money. The journalists keep their jobs. Readers get continuity. The story becomes "Post streamlines to focus on national and investigative journalism while supporting local news through partnership" instead of "Post slashes local reporting."

This isn't theoretical. It would have worked financially. It would have worked operationally. It would have worked for everyone except the narrative that Lewis was aggressively cutting costs.

But it required Bezos to stay engaged. To actually care about the journalism. To be willing to have difficult conversations about what value a newspaper provides to a city and how to preserve that while also improving financials.

That's the real cost of abstracted ownership. Not that billionaires are evil (most aren't). But that they treat media ownership like a financial investment rather than a civic responsibility.

Since 2008, the average newspaper has reduced its newsroom size by approximately 50%, highlighting the impact of cost-cutting ownership structures. Estimated data.

DC's Anger: Why the City Turned on Bezos

Washington is not a city that casually forgets things. It's a city built on institutional memory and relationship-mapping. When Bezos bought the Post, the city saw it as a guy from outside who was going to save the paper. There was gratitude. Maybe some skepticism, but genuine hope.

That's dissipated. The reason isn't ideological (DC actually likes Bezos, generally). It's personal. You can't lay off journalists mid-Olympic coverage and expect a city not to notice. You can't close the desks that defined your institution for a generation and not create anger.

The city's fury isn't about Bezos being a bad person. It's about him being absent. It's about the Post being treated like a quarterly expense rather than a civic institution. It's about the incomprehensibility of rejecting a deal that would have kept people employed.

That anger will persist. It will shape how Washington sees the Post going forward. When the paper reports on local politics, readers will think "who's still covering this?" When sports stories run, they'll notice they're thinner, less expert. The cumulative effect is slow erosion of the institution's status.

Broader Tech Industry Failures in Media

This story also sits within a larger pattern of tech executives misunderstanding media. Elon Musk bought Twitter because he believed he could apply platform economics to social media. He was wrong about fundamental things. Mark Zuckerberg repeatedly claimed he wasn't a media company while making decisions that shaped what billions of people read. Bezos bought the Post thinking capital and operational discipline could fix journalism.

The issue is that journalism isn't like technology. You can't optimize it on a curve. There's no Moore's Law equivalent for reporting. Adding more engineers doesn't make journalism faster. Cutting costs always reduces quality because journalism is labor-intensive.

Bezos understood this intellectually. He said it repeatedly. But operationally, he structured the business in a way that made cost-cutting inevitable. That's the gap between understanding something and actually living with the implications.

What Comes Next for the Washington Post

The Post will continue. Bezos isn't selling. The paper will report on politics, investigations, and national news. It will be more profitable than it was. But it will be smaller. It will have less capacity. It will have less influence over how Washington sees itself.

Readers will notice. The people who loved the Post's sports desk will find coverage elsewhere. The people who relied on local reporting will cobble together information from City Paper, local blogs, and news alerts. The institutional relationship between Washington and its paper of record will slowly weaken.

This is how institutions die. Not all at once. Gradually. In choices that seem sensible in the moment but add up to something larger.

Lessons for the Future of Media Ownership

If you're a billionaire thinking about buying a newspaper, here's what this story should teach you: it's not enough to have capital. It's not enough to have good intentions. You have to stay engaged. You have to be willing to make difficult decisions about quality, strategy, and values. You have to resist the temptation to hire someone else to make those decisions and then ignore the results.

Alternatively: don't buy a newspaper. Support journalism in other ways. Fund investigative outlets. Support newsrooms directly. Invest in digital-native news organizations. But if you're going to actually own a paper, understand that you're not managing a business. You're maintaining an institution. That requires work.

The City Paper's Moment

Mark Ein is in an interesting position. He publicly committed to hiring the Post's journalists. That's a significant promise. City Paper has much smaller resources than the Post. Taking on 50-100 journalists would transform the organization.

But it could work. City Paper is exactly the kind of organization that could actually benefit from an influx of established journalists. The paper has credibility and roots. Add experienced reporters and editors, and suddenly you have a serious local newsroom again.

The challenge is financial. Can Ein sustain the payroll? Can the organization find revenue streams to support it? Or will this be another case where good intentions collide with economic reality?

What This Reveals About Billionaire Media Ownership More Broadly

The Post story is a case study in how billionaire ownership of media often fails. The owner has the best intentions. The institution is well-resourced. The city and readers are grateful. But something in the structure—the abstraction, the delegation, the willingness to "optimize"—gradually erodes the thing that made ownership valuable in the first place.

It doesn't have to be this way. Some billionaire-owned media works. The Washington Post could work. But it requires the billionaire to actually care. To stay engaged. To resist the logic of pure cost optimization.

Bezos didn't do that. That's not a moral failure. It's just a choice. But choices have consequences. And the consequence of this choice is that a major American newspaper is smaller, weaker, and less trusted than it was a month ago.

Conclusion: The Price of Abstraction

The Washington Post's crisis isn't really about Bezos or Lewis or the City Paper or even cost-cutting. It's about what happens when someone with the resources to support an institution decides not to. It's about the gap between saying you support journalism and actually doing the work to support it.

There was a deal on the table. It would have kept journalists employed. It would have preserved institutional capability. It would have cost Bezos nothing. It didn't happen because nobody engaged with it. Because Lewis was focused on his mandate. Because Bezos was focused on everything else. Because the easiest path was just to cut and move on.

That's the lesson here. Not that billionaires are evil. Not that cost-cutting is wrong. But that ownership without engagement, responsibility without attention, and promises without follow-through eventually hollow out the institutions they're meant to protect.

The Washington Post will survive. But a version of it has died. The one with robust local reporting. The one where sports journalism mattered. The one where the newsroom felt like the heartbeat of the city.

What replaced it is lighter, cheaper, and more "efficient." On a spreadsheet, that looks like progress. In reality, it's erosion. And erosion, if unchecked, eventually reveals bedrock.

FAQ

What is the Washington City Paper's proposal?

The Washington City Paper proposed acquiring the Washington Post's sports and local news desks, along with the journalists who worked there. The deal would have allowed City Paper to host this content on its platform with investment from Mark Ein, who owns the company. This would have preserved jobs while reducing the Post's operational expenses.

Why did the Washington Post reject the City Paper proposal?

The exact reasoning was never publicly explained, but the timing suggests that CEO Will Lewis, who had a mandate to cut costs, decided to execute immediate layoffs rather than pursue a more complicated restructuring. The negotiations, which had been ongoing for weeks and seemed productive, suddenly ended when the Post announced the closures without public explanation.

How many journalists were affected by the Washington Post's layoffs?

The Post laid off approximately 400 staff members across multiple desks, with specific cuts to sports and local news sections. These were operational roles, editors, reporters, photographers, and producers who had covered Washington's civic and athletic landscape for years.

What makes the Washington Post's decision unusual compared to other media cuts?

Most media layoffs are explained as necessary responses to revenue declines or market changes. The Post's decision was unusual because it involved rejecting an active proposal to preserve those jobs and continue the work through a partnership. Additionally, the timing—mid-Olympic and pre-Super Bowl coverage—suggested the cuts were driven by spreadsheet optimization rather than strategic necessity.

How does Jeff Bezos's ownership of the Washington Post factor into these decisions?

Bezos bought the Post in 2013 and has generally been supportive of the organization, even accepting losses in earlier years. However, his involvement appears to be hands-off, with operational decisions delegated to hired leadership. The City Paper proposal was never apparently escalated to Bezos for input or approval, suggesting his ownership is more financial than operational.

What could the modular media ownership model look like?

Instead of one large institution trying to do national politics, investigations, sports, and local reporting, the work could be distributed across specialized organizations. The Post could focus on national and investigative journalism, while City Paper handles hyperlocal sports and government coverage. This approach would theoretically match organizational strengths to coverage types and find sustainable revenue models for each piece.

Is local news coverage more sustainable when separated from national outlets?

Potentially yes. National outlets struggle to monetize local coverage because readers expect it to be free. Hyperlocal organizations like City Paper can sometimes find sponsorship, event revenue, and community-focused monetization that works better at smaller scale. However, this requires the local organization to have existing credibility and community relationships, which City Paper has but most startup news outlets lack.

What happens to journalists after major newspaper layoffs?

Some find positions at other outlets. Some move to different cities for available jobs. Some supplement journalism with freelance writing or other work. Some leave the field entirely. The institutional knowledge and beat relationships they've developed typically dissipate, as it takes years to rebuild those connections.

How does this compare to other billionaire-owned media?

The pattern is consistent: billionaires buy media with good intentions, delegate to hired executives who prioritize cost reduction, and gradually see quality and readership decline. Examples include the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, and Denver Post, which have all undergone similar cycles of cost-cutting that affected their journalism capacity.

Could Bezos have prevented this situation?

Yes. If Bezos had stayed engaged with strategic decisions and specifically asked about alternative structures to layoffs, the City Paper proposal likely would have moved forward. However, this would have required Bezos to treat the newspaper as a journalism venture rather than a financial investment to be managed by hired executives.

Key Takeaways

- The Washington City Paper offered to acquire the Post's sports and local sections for a modest investment while keeping journalists employed, but the proposal was rejected in favor of immediate layoffs

- CEO Will Lewis appeared receptive to the deal but ultimately chose swift cost-cutting over a more complex restructuring, suggesting the decision was driven by optimization rather than strategic necessity

- Bezos remained absent from the decision-making process, delegating to hired leadership and abstracting himself from the difficult work of managing a news institution

- The decision revealed how billionaire ownership of media often fails: good intentions get abstracted into cost-cutting mandates that gradually hollow out the institution

- The Post's situation mirrors broader patterns of newsroom decline across the industry, where ownership structures incentivize short-term financial optimization over long-term journalism quality

Related Articles

- Washington Post CEO Crisis: What Jeff D'Onofrio's Appointment Means for Media [2025]

- Washington Post's Tech Retreat: Why Media Giants Are Abandoning Silicon Valley Coverage [2025]

- Netflix's Warner Bros. Acquisition: The $82.7B Megadeal Explained [2025]

- Spotify's 751M User Milestone: How Wrapped & Free Tier Features Changed the Game [2025]

- YouTube TV $80 Discount: How to Get It Before 2025 Ends

- Amazon's Melania Documentary Box Office Collapse: Why Theatrical Release Failed [2025]

![Why Bezos Abandoned the Washington Post's Newsroom [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-bezos-abandoned-the-washington-post-s-newsroom-2025/image-1-1770768432690.jpg)