Introduction: The Copper Crisis We're Not Ready For

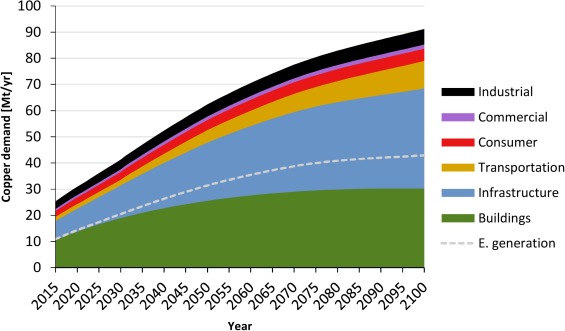

Copper is about to become the mineral everyone fights over. It's not flashy like lithium or rare earths, but it's absolutely critical. Every data center that powers AI, every electric vehicle on the road, every solar panel feeding the grid—they all need copper. Lots of it.

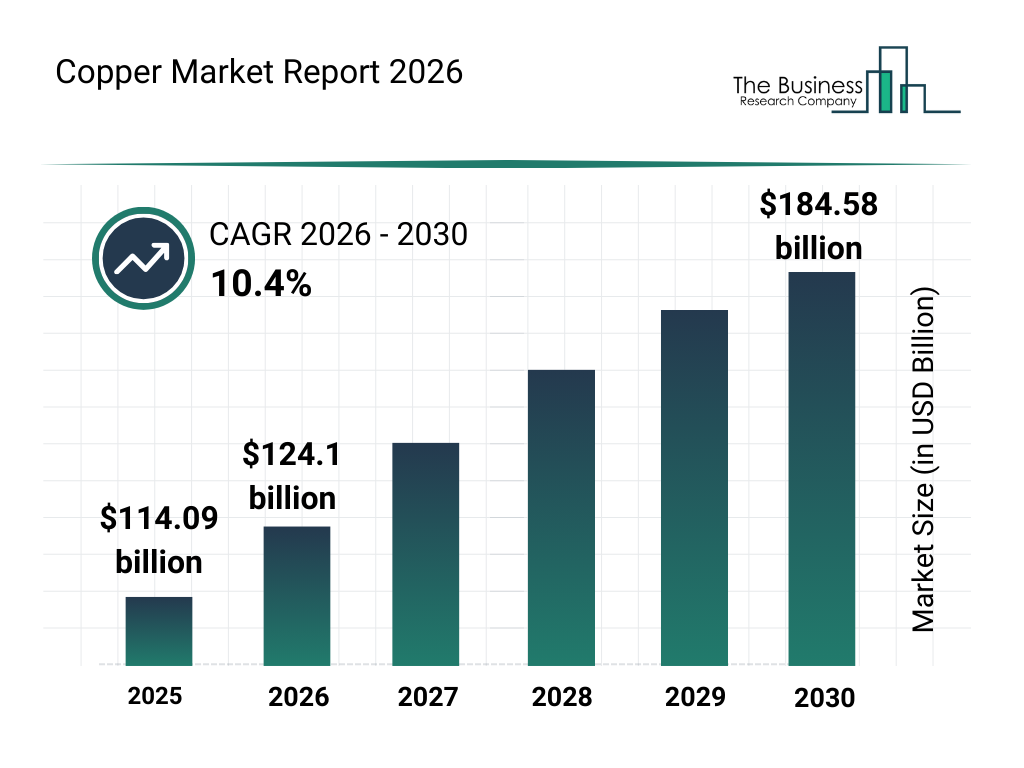

Right now, the numbers look grim. Demand is accelerating as we electrify everything and build out AI infrastructure. By 2040, the world could face a copper deficit of 25% or more—that's millions of tons short of what we need. Some estimates suggest we're looking at genuine scarcity by the early 2030s if nothing changes. Copper prices have already doubled in the past five years, and that's just the warm-up.

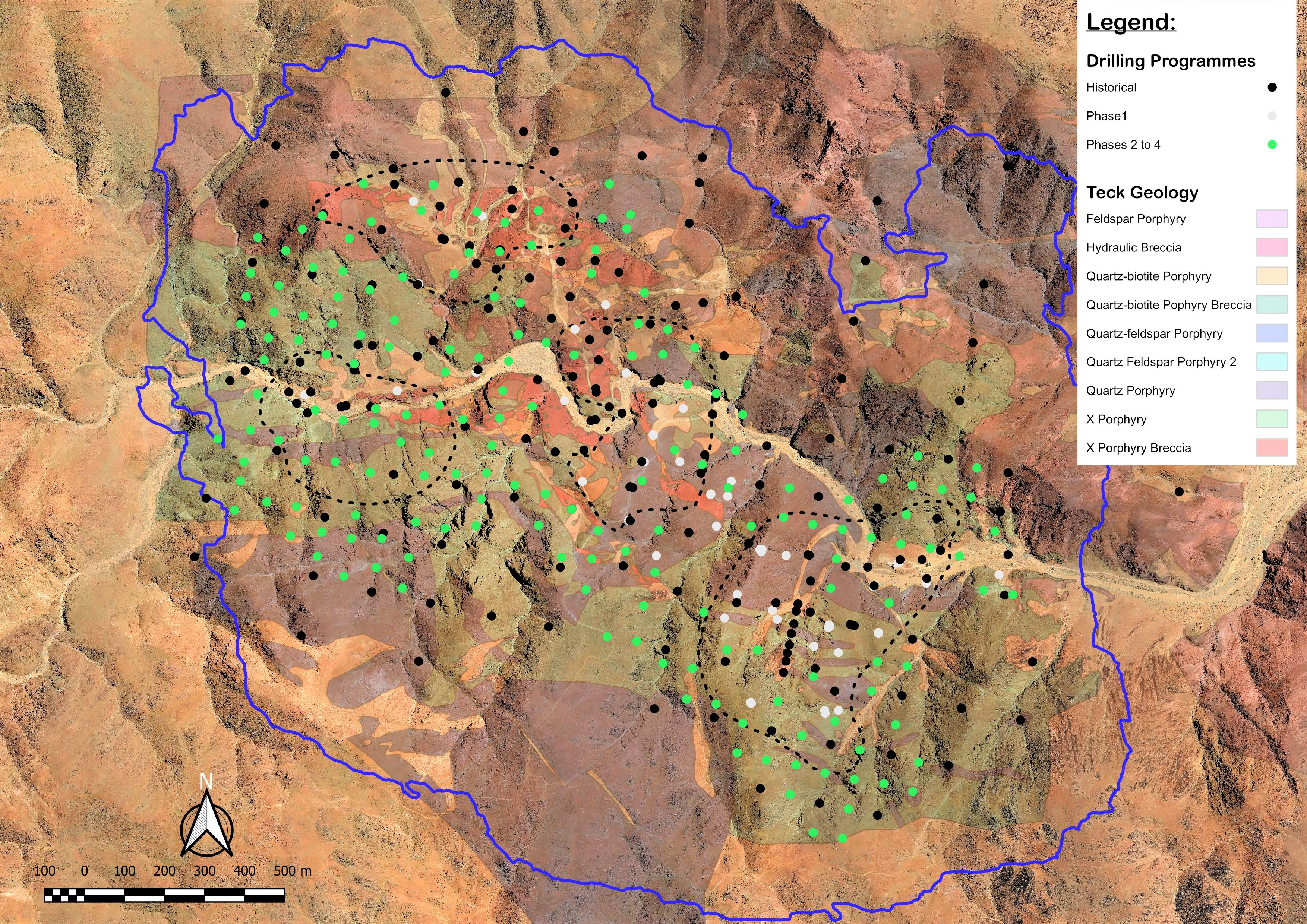

Companies are panicking. They're pouring money into new mining operations. Ko Bold, an AI-powered minerals startup, raised $537 million last year specifically to develop a copper deposit in Zambia. Other exploration firms are spending billions to find and develop new reserves. But here's the uncomfortable truth: finding new copper is getting harder and more expensive. We're mining lower-grade ore, going deeper underground, and operating in more challenging environments.

What if we didn't need to find so much new copper? What if we could squeeze 50% more copper out of the mines we already operate?

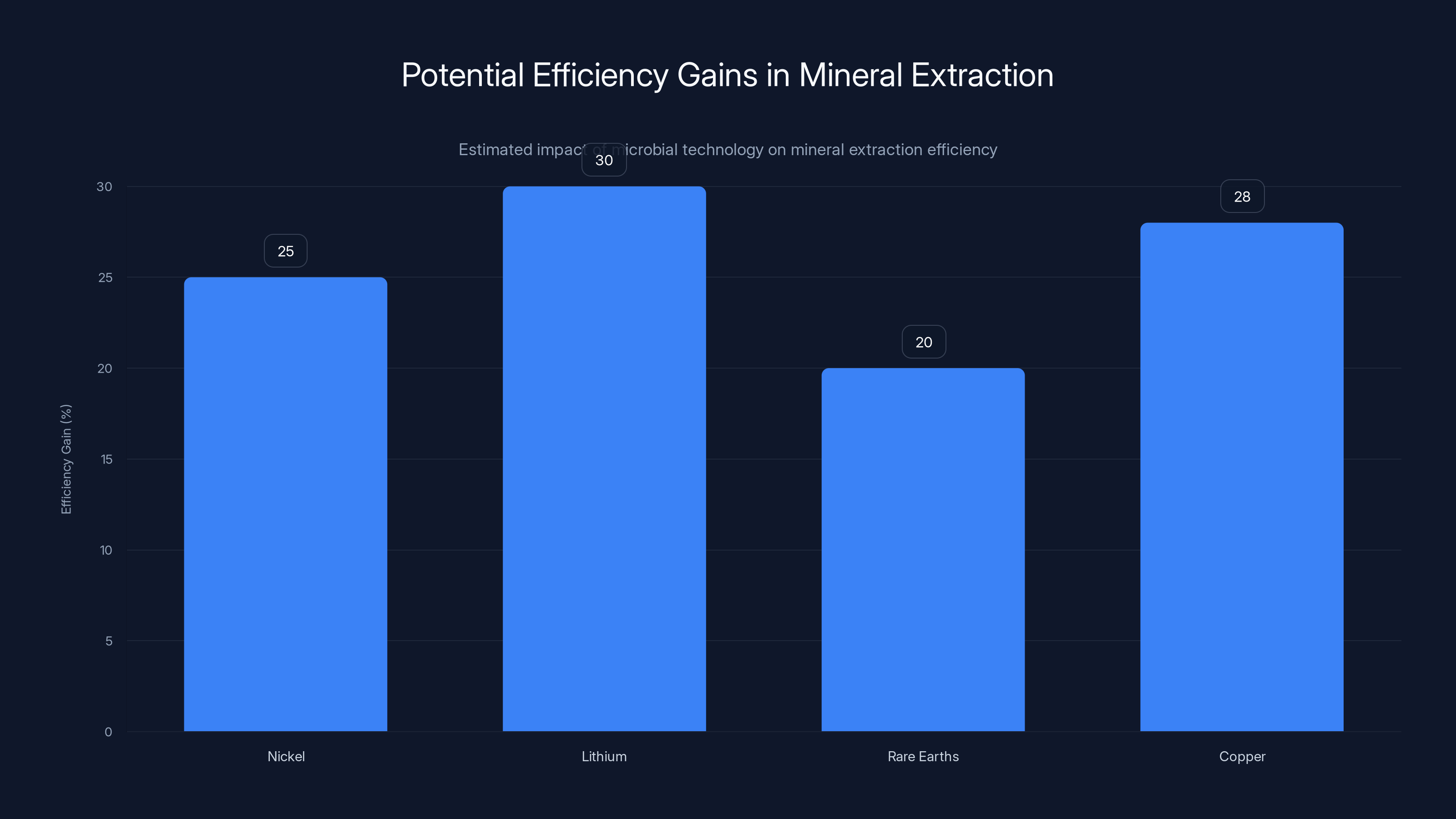

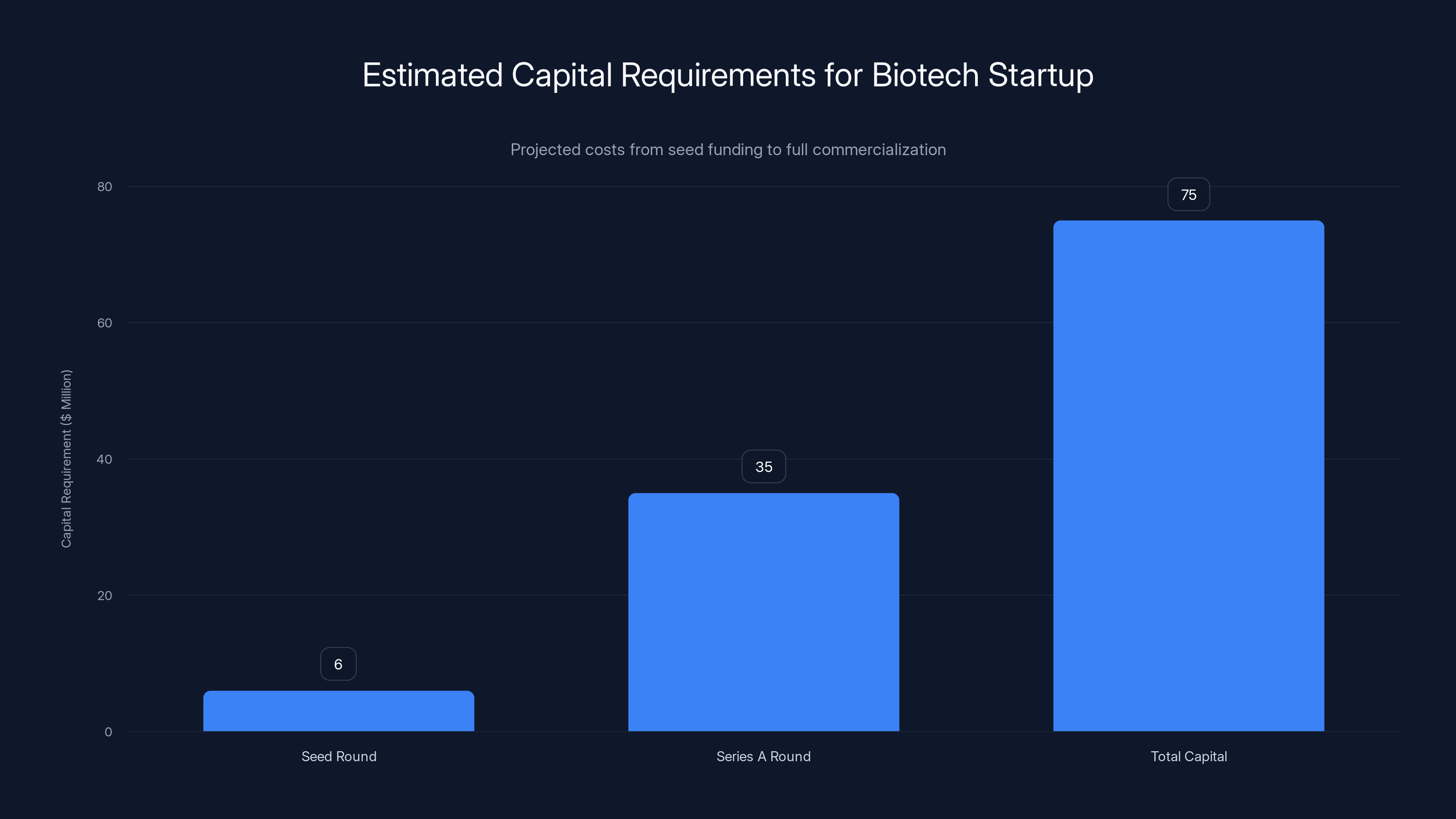

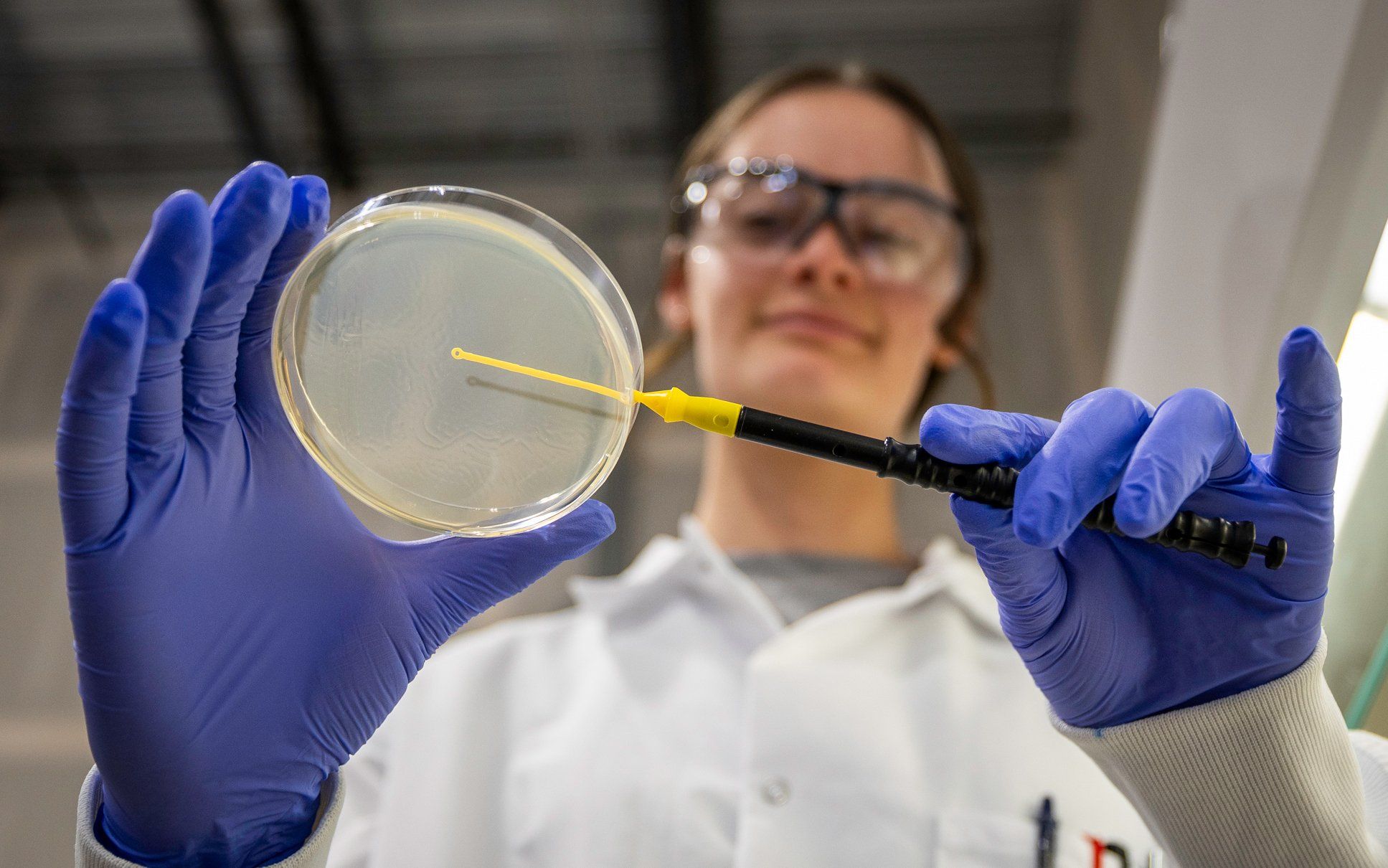

That's exactly what Transition Metal Solutions is betting on. The startup has figured out how to use microbial probiotics to boost copper extraction by 20-30%. It sounds absurd. It sounds like science fiction. But the science is real, the results are measurable, and investors are convinced. The company just closed a $6 million seed round led by Transition Ventures, with participation from a deep bench of climate and materials investors.

This isn't about discovering new bacteria. It's about understanding that the microbes already working in copper mines are basically living in chaos, and if you feed them the right compounds, they perform dramatically better. Think of it as nutritional optimization for microbial communities. Add the right probiotics, and suddenly you're extracting 90% of the copper from ore samples instead of 60%.

In a world staring down a real mineral shortage, this could change everything. Let's dig into how one startup is using bugs to solve a crisis.

TL; DR

- Copper shortage imminent: Demand could exceed supply by 25% as early as 2040, with prices already doubling in five years

- Microbes are key: Bacteria already help extract copper, but current methods only optimize for isolated strains and ignore community dynamics

- Transition's innovation: Using proprietary microbial "probiotics"—inorganic additives—boosts copper extraction from 60% to 90% in lab samples

- Real-world impact: Commercial mines could improve extraction rates from 30-60% to 50-70% or higher, potentially solving shortage without new mining

- Business model: Tailored additive cocktails per mine, with third-party validation, $6M seed funding to prove concept

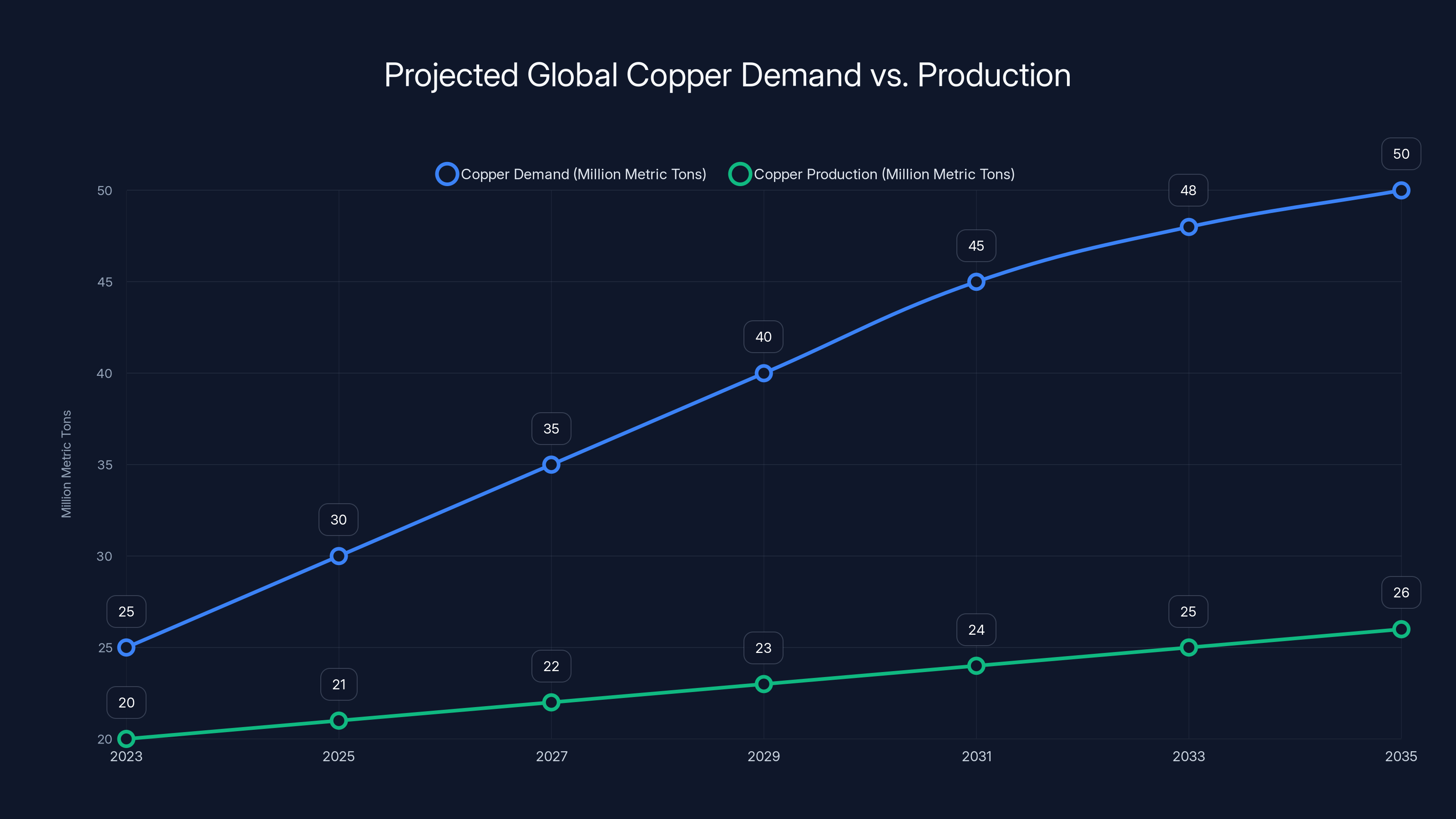

Estimated data shows a significant gap between copper demand and production by 2035, highlighting the urgency of addressing supply constraints.

Part One: Understanding the Copper Shortage

Why Copper Matters More Than Ever

Copper isn't a glamorous mineral. It's not going to power your phone battery or store energy in a grid-scale facility. But it's the connective tissue of the modern world, and that makes it absolutely essential.

Electric vehicles need about 3-5 times more copper than internal combustion cars. A typical EV has roughly 50-70 pounds of copper wired through motors, charging systems, and control electronics. Solar panels, wind turbines, transformers, data center infrastructure—all of it copper-hungry. As we transition to renewables and electrify transportation, copper demand is growing exponentially.

AI is accelerating this curve. Data centers consume enormous amounts of copper for wiring, cooling systems, and power distribution. Every GPU cluster that runs a large language model or trains a vision model requires substantial copper infrastructure. We're not just talking about powering existing technology more efficiently. We're talking about building entirely new computing infrastructure at unprecedented scale.

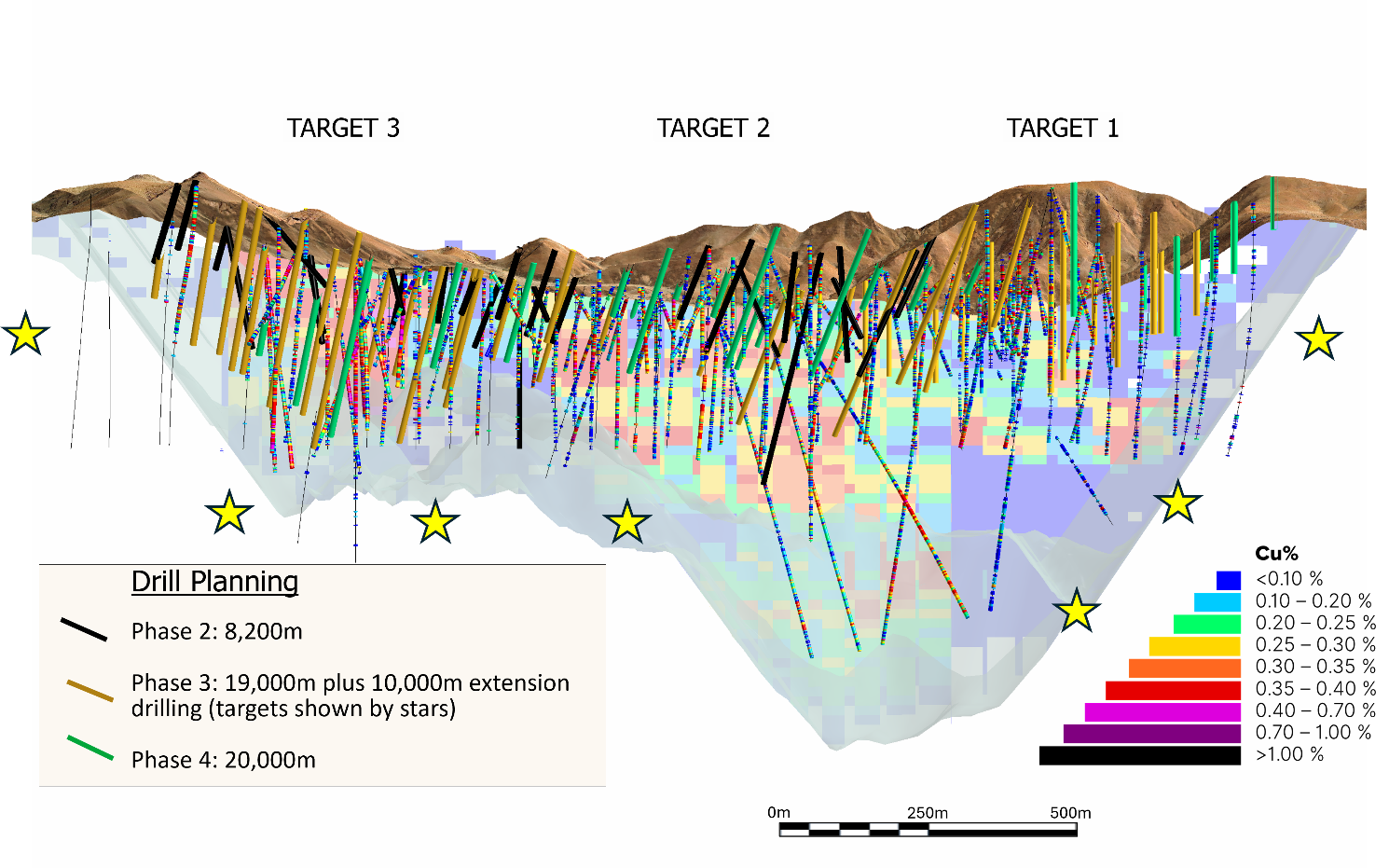

The supply side is much grimmer. Copper reserves exist, but they're increasingly difficult and expensive to access. The average grade of mined copper ore has declined over the past two decades. We're mining deeper, in more remote locations, with higher capital costs and environmental impacts. New mine development takes 15-20 years from discovery to production. That's not a timeline that matches demand acceleration.

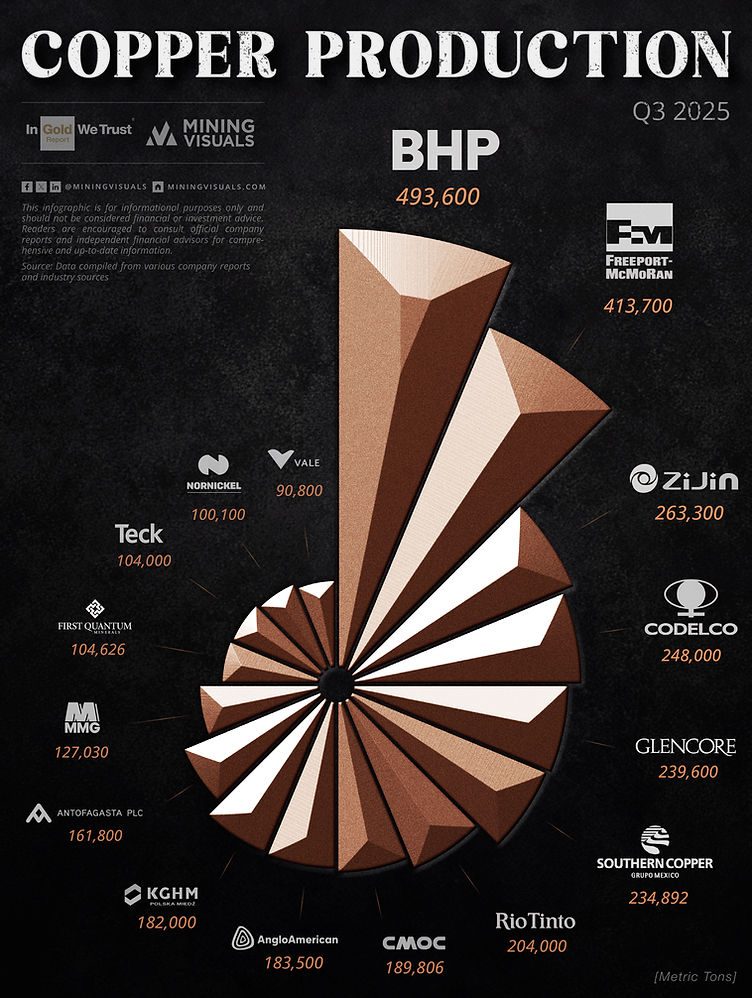

Consider the math. World copper demand is projected to reach 50 million metric tons annually by 2035. Current production sits around 20 million tons per year. The gap isn't small. And that gap gets worse every year as electrification accelerates. This isn't a problem a few new mines can solve in a decade.

The Cost of Copper Extraction Today

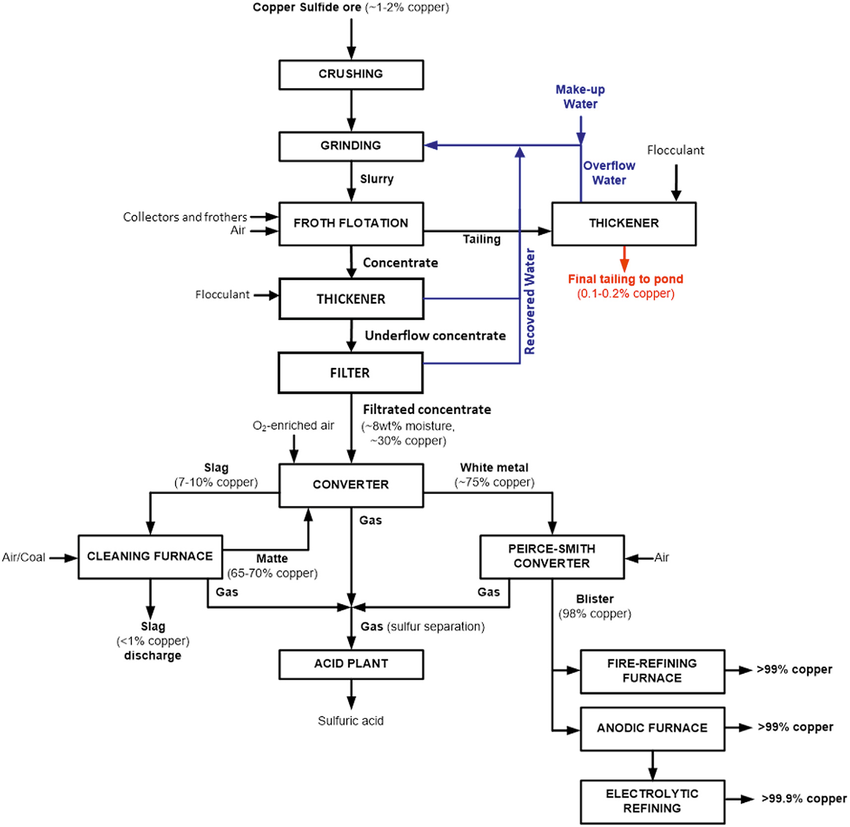

Traditional copper extraction is a multi-stage process, and it's wasteful. Mining operations use heap leaching, where ore is crushed, stacked in piles, and chemically processed to extract copper. The efficiency varies wildly by mine and ore quality, but industry averages hover around 30-60% copper recovery.

That means 40-70% of the copper in the ore is left behind in the tailings. Massive amounts of that copper are essentially abandoned. In a world of copper shortage, that's not just economically inefficient—it's criminal waste.

Costs are rising too. Processing ore requires sulfuric acid, water, and energy. All of these inputs are getting more expensive. Environmental regulations require better tailings management and reduced water consumption. New mine development in developed countries faces permitting delays and public opposition. Expanding production in existing mines runs into ore quality and geological constraints.

The industry response has been to either accept margin compression or accept production decline. A few companies are investing in new mines, but those projects represent a 10-15 year timeline and billions of dollars of capex with regulatory uncertainty.

Why Investors Are Panicking About Copper

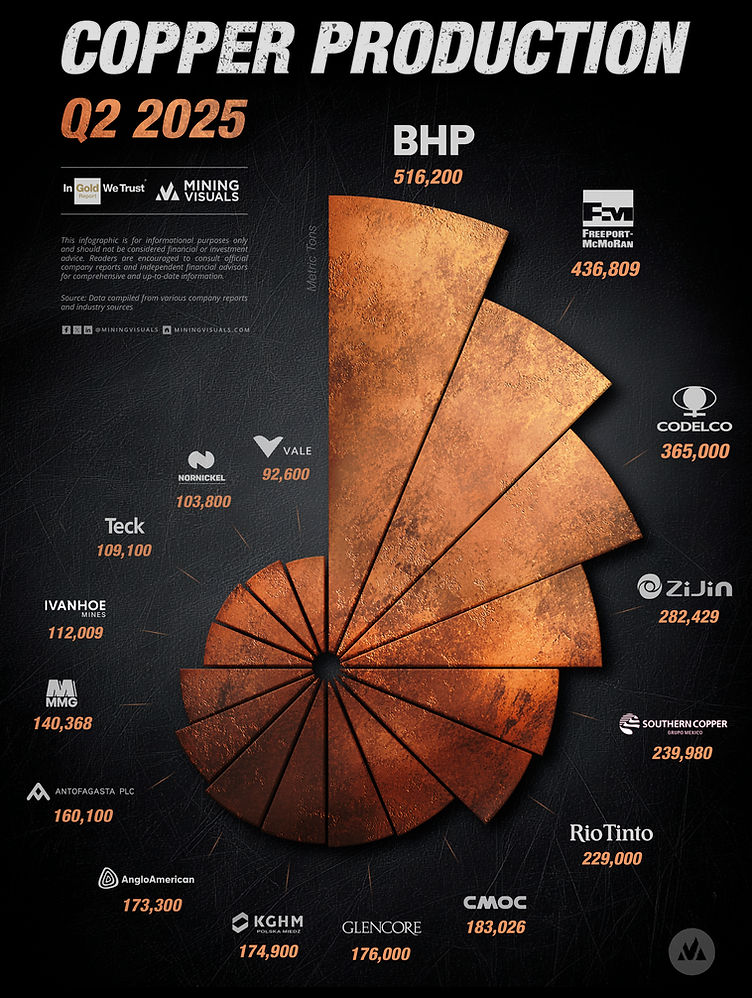

Climate tech investors and materials companies suddenly care about copper extraction because the math is brutal. If we want to hit net-zero energy and transport by 2050, we need dramatic increases in copper availability. The International Energy Agency estimates we'd need a 20-30% increase in copper production just to meet climate transition goals. That's on top of existing demand from AI, consumer electronics, and industrial infrastructure.

Ko Bold's $537 million funding round wasn't an anomaly. It was a signal that early-stage investors recognize copper as a gating factor for the entire clean energy transition. If we can't source enough copper, we can't build enough renewable energy infrastructure, EVs, and grid modernization. It's that fundamental.

So the investment thesis is simple: solve copper shortage, enable the energy transition, capture massive returns. The challenge is that most solutions are either 15 years away (new mines), environmentally questionable (deep-sea mining), or technically unproven (bioleaching optimization).

Transition Metal Solutions is betting the entire market is approaching copper shortage wrong. Instead of finding new copper, why not extract more from what we're already mining?

Microbial technology could boost mineral extraction efficiency by 20-30%, reducing the need for new mines. (Estimated data)

Part Two: How Microbes Extract Copper From Ore

The Biology of Copper Leaching

This is where the story gets interesting. Copper doesn't exist in mines as pure metal. It's locked inside rock as sulfide minerals, mostly chalcopyrite and bornite. Getting that copper out requires breaking those minerals apart. Acid can do it chemically, but there's a more elegant approach: let bacteria do the work.

Specific microbial species, particularly Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans, naturally break down sulfide minerals and release copper ions into solution. These microbes have been doing this for millions of years in acidic environments. Humans figured out how to use them maybe 80 years ago. Modern copper mining has leveraged bacterial biogeochemistry for decades.

The process works roughly like this: crushed ore is stacked into heaps. Dilute sulfuric acid is sprayed onto the piles, creating acidic conditions. Bacteria move through the ore, oxidizing sulfides, releasing copper ions. Copper-laden solution drains to the bottom, gets collected, and processed further. It's elegant. It's economical. It's biological.

But here's the thing almost nobody talks about: we barely understand what's actually happening. The microbial communities in heap leaches are insanely complex. Recent research suggests over 90% of the microorganisms present in active mining operations have never been formally identified or cultured in the lab. We know some of the major players—a few species of Acidithiobacillus, some archaeal thermophiles. But the ecosystem is fundamentally mysterious.

Why Traditional Microbial Optimization Fails

Industry attempts to boost copper extraction have mostly failed, and Sasha Milshteyn, the CEO of Transition Metal Solutions, has a clear theory about why. Companies have been thinking about microbial optimization all wrong.

The standard approach: identify a high-performing bacterial strain in lab conditions. Isolate it. Grow massive cultures. Inoculate the ore heap with millions of cells of this strain. Hope it thrives.

Sounds reasonable. It fails consistently. Why? Because microbes aren't solo performers. They're ensemble players. A single species can only do so much. The copper-leaching process depends on complex interactions between dozens of species playing different ecological roles. Boosting one species at the expense of others is like adding a virtuoso violin player to an orchestra but removing half the other instruments.

Second problem: we fundamentally don't understand the heap leach microbiome. You can only study what you can grow in a lab. That's maybe 5% of the community. The other 95% remains invisible until recently developed genetic sequencing techniques came along. But sequencing tells you what's there, not what it's doing or why it matters.

Millions of organisms are operating in conditions we can barely simulate. The pH is around 2—incredibly acidic. Iron, sulfur, and other metals are present at concentrations that would kill most organisms. Clay minerals absorb and alter compounds. It's a harsh, extreme environment that's nothing like a lab culture vessel.

Third problem: the biology is slow. A mining operation is patient. It runs for months and years. Lab tests run for weeks. The timescale mismatch creates illusions. Something looks promising for three weeks in a test tube, but the effect drops off dramatically in real conditions over real timeframes.

The Community Approach: A Paradigm Shift

Transition Metal Solutions is approaching this problem differently. Instead of boosting individual strains, they're trying to nudge the entire microbial community toward higher copper extraction performance.

The innovation is deceptively simple: apply low-cost, mostly inorganic chemical additives that are already present at mining sites. These compounds aren't antimicrobials or genetic modifications. They're not expensive proprietary biologics. They're simple chemistry that changes the environmental conditions in ways that favor more efficient copper extraction.

Think of it as creating the conditions where the existing microbial community can perform optimally. You're not imposing a solution from outside. You're enabling what the community wants to do anyway.

Millshteyn describes it like this: "We're trying to nudge the community towards the higher functional state." Not steering one species. Not killing others. Nudging the entire ecosystem toward better copper liberation.

Lab results suggest this works remarkably well. In samples treated with Transition's proprietary additive cocktail, extraction rates reached 90% compared to 60% with traditional methods. That's a 50% improvement in extraction efficiency. In mining terms, that's transformative.

Part Three: Transition Metal Solutions' Technical Approach

The Proprietary Additive Formulation

Transition isn't disclosing exactly what's in the formula—that's the secret sauce. But the approach is knowable. The company applies what Milshteyn describes as a "cocktail" of mostly inorganic compounds. These are substances already present at mining sites, just in different concentrations or combinations.

The formula likely includes iron compounds (ferric iron is critical to sulfide oxidation), sulfur compounds (which feed certain bacterial metabolic pathways), possibly some trace elements that support microbial growth. The specifics vary by mine because each mine has a different microbial community.

This is where Transition's approach gets genuinely clever. They don't apply the same formula everywhere. They test the microbial community in a target mine, understand what's currently limiting copper extraction, and tailor the additive cocktail to that specific context. Personalized probiotics for mining.

Over time, as they accumulate more data from more mines, Milshteyn expects they'll be able to predict optimal formulations without extensive testing. Machine learning could eventually crack the pattern. For now, it's research and development work on a per-mine basis.

Why Inorganic Additives Work Better Than Biological Inoculants

There's an important technical insight here. Transition's approach actually works better than the traditional approach of adding more bacteria, for several reasons.

First, biological inoculants compete with existing microbial communities. You introduce external cells into an environment already colonized by billions of native organisms. The new cells have to compete for nutrients, space, and ecological niche. Most fail. You're essentially trying to invade an established ecosystem with a foreign species.

Chemical additives don't compete. They feed the existing community. They create conditions where the native species already present can flourish. You're working with what's already there, not against it.

Second, inoculants require living cells. Cells are fragile. They die during transport, storage, and application. By the time they reach the ore heap, viability is degraded. Chemical additives are stable. No viability loss. You get the full benefit.

Third, optimizing for individual species creates fragile monocultures. If conditions shift slightly, that single species crashes and extraction plummets. A diverse community is resilient. It adapts. Multiple species playing complementary roles means the system keeps working even when individual conditions change.

Transition's approach aligns better with ecological principles. You're not fighting complexity. You're working with it.

Lab Results and Expected Field Performance

In controlled lab samples, Transition achieved 90% copper extraction using their additive cocktail, up from 60% with baseline methods. That's the headline number. But it's important to understand what that means and what to expect in real mining operations.

Lab conditions are controlled and simplified. You're working with uniform ore samples, precise chemical control, constant temperature, no geological variation. It's ideal but not real. When you scale to an actual ore heap—potentially containing tens of thousands of tons of material—conditions become heterogeneous. pH varies. Ore grade varies. Microbial populations vary. Results degrade.

Millshteyn is realistic about this. He expects field performance to be lower than lab results, but not by catastrophic margins. His estimate: traditional heap leaches extract 30-60% of copper depending on ore quality and mine conditions. With Transition's treatment, he expects to boost that to 50-70%, potentially higher.

That's a meaningful improvement. If you're mining ore that contains, say, 1% copper by weight, and you're currently extracting 40% of it (0.4% from original ore), Transition's technology could boost that to 60% extraction (0.6% from original ore). That's a 50% improvement in yield without finding a single new ton of ore.

The Environmental Story

There's a clean angle here too. More efficient extraction from existing mines means less mining. You don't need to open as many new deposits. New mines require environmental permitting, land use conversion, and tremendous water consumption. Squeezing more copper from existing operations is environmentally cleaner.

Using mostly inorganic additives that are already present at mining sites means minimal new chemical introduction. You're not dumping novel compounds into the environment. You're adjusting concentrations of things already there.

This positioning matters for investor appeal and mine operator buy-in. The technology solves a technical problem while improving the environmental story. That's a rare combination.

Transition is projected to grow from

Part Four: The Business Model and Path to Market

The Validation Challenge

Transition Metal Solutions faces a fundamental credibility problem, and the company is aware of it. The mining industry is conservative. Operators don't experiment lightly. Capital costs are enormous. Failure means disrupted production and lost revenue. No mine operator is going to change their leaching process based on a startup's lab results and promises.

That's why Transition's first major milestone is third-party validation. The company plans to work with a recognized metallurgy lab—one trusted and known within the mining industry. Third-party confirmation of the lab results is non-negotiable.

Millshteyn was explicit about this: "Without third party results, nobody's going to believe you." That's not cynicism. That's pragmatism. The mining industry wants independent verification. It's reasonable. It's also expensive and time-consuming. But it's necessary.

The $6 million seed round should cover that validation phase. Transition will run extensive tests with third-party labs, generate reproducible results, publish findings (or at least make them available to potential customers), and build a case that the technology works.

Second phase: demonstration scale. Not a tiny lab test. A real ore heap containing tens of thousands of tons of material. Actual mineral processing equipment. Real geological and environmental conditions. This phase proves that lab results translate to commercial scale.

Third phase: deployment at commercial mining sites. Multiple mines, multiple ore types, multiple geographical locations. Prove the technology is robust and reproducible.

Revenue Model: Additive Supply + Consulting

Transition's business model is reasonably straightforward. The company develops proprietary additive formulations tailored to specific mines. It sells these additives to mining operators, presumably taking a margin on the cost of production. Alternatively, it could license the technology and take a royalty on improved copper extraction.

There's also a consulting element. Testing a new mine's microbial community, developing a customized additive cocktail, optimizing application rates—all of this is services revenue. Maybe Transition becomes a lab services provider in addition to an additive supplier.

The value proposition for mining operators is compelling if the technology works: extract 50% more copper from existing ore using low-cost additives. The payback period is probably measured in months, not years. A 20-30% boost in extraction efficiency is worth substantial amounts of money to a mining company.

Consider rough math: a mid-sized copper mine might process 50,000 tons of ore per year with 0.8% copper content. That's 400 tons of copper processed. If current extraction is 40%, that's 160 tons of actual copper. If Transition boosts extraction to 60%, that's 240 tons. That's 80 tons of additional copper per year. At current prices around

Oddly, the additive costs are probably under $100,000 per year. The ROI is enormous. Mining operators should be eager to adopt something that works.

Investor Appeal and Funding

Transition's $6 million seed round included Transition Ventures (climate-focused VCs) alongside other climate and materials investors. The pitch is compelling: a small amount of capital solves a major mineral shortage that gates the entire energy transition. If copper shortage limits EV adoption, renewable energy deployment, or grid modernization, that's a multi-trillion-dollar problem.

A technology that ameliorates that problem, even partially, is enormously valuable. Investors aren't betting on Transition's additive formulation. They're betting that somebody solves the copper shortage, and if Transition has even a 20-30% probability of being that somebody, the expected value is massive.

Future funding will probably be easier if early validation results are positive. A successful demonstration at a real mine changes the narrative from "interesting lab results" to "proven commercial technology." That shifts valuation dramatically.

The path to acquisition is also clear. Major mining companies (Rio Tinto, BHP, Antofagasta) would probably be interested in acquiring a proven extraction efficiency technology. They have the distribution, the mine relationships, and the capital to deploy globally. A successful acquisition could exit early investors at substantial returns within 3-5 years.

Part Five: Real-World Implementation Challenges

Scaling from Lab to Field

Transition's next big challenge is translating lab results to field performance. Sounds simple. It's not.

Ore composition varies between mines and within mines. The microbial communities are different. Water chemistry is different. Climate affects temperature and evaporation. Geological structures affect how additives percolate through ore piles. You can control maybe 30% of the variables in a field setting. The other 70% are just environmental complexity.

That's why demonstration heaps are crucial. They're not as controlled as a lab, but they're smaller and more manageable than a full-scale mining operation. They provide a bridge between controlled conditions and uncontrolled reality.

Transition will probably need to run multiple demonstration heaps across different ore types and locations to build evidence that the technology is robust. If results vary wildly between sites, the technology isn't ready for commercialization. If results cluster within 10-15% of expected values, that's probably acceptable variance for a mining operation.

Regulatory and Environmental Approval

Mining is heavily regulated. Any change to processing methods requires environmental review, potentially permitting, and regulatory approval. Transition's additives are probably benign from an environmental perspective—mostly inorganic compounds already present at mines—but documentation and testing will be required.

Different jurisdictions have different standards. An approval process in Chile (where 28% of global copper is produced) might differ from approvals in Peru or Australia. Transition will need to navigate multiple regulatory environments.

On the positive side, the environmental story is strong. More efficient extraction from existing mines means fewer new mines. That's genuinely better from an environmental perspective. Regulators and permitting authorities should view it favorably. But paperwork and proof will be required.

Adoption Barriers Among Conservative Mine Operators

Here's the uncomfortable truth: mining companies are conservative. Not intellectually conservative. Operationally conservative. A change in processing methodology creates risk. If something goes wrong, production falls offline. That's immediate revenue loss. For a large mining operation, losing production for even a week is worth millions in lost copper sales and economic disruption.

Mining operators will probably require extensive proof before they implement Transition's technology at scale. Third-party validation helps. But they'll probably want to see the technology work at a demonstration mine they operate or closely monitor. Some might run small-scale tests before full implementation.

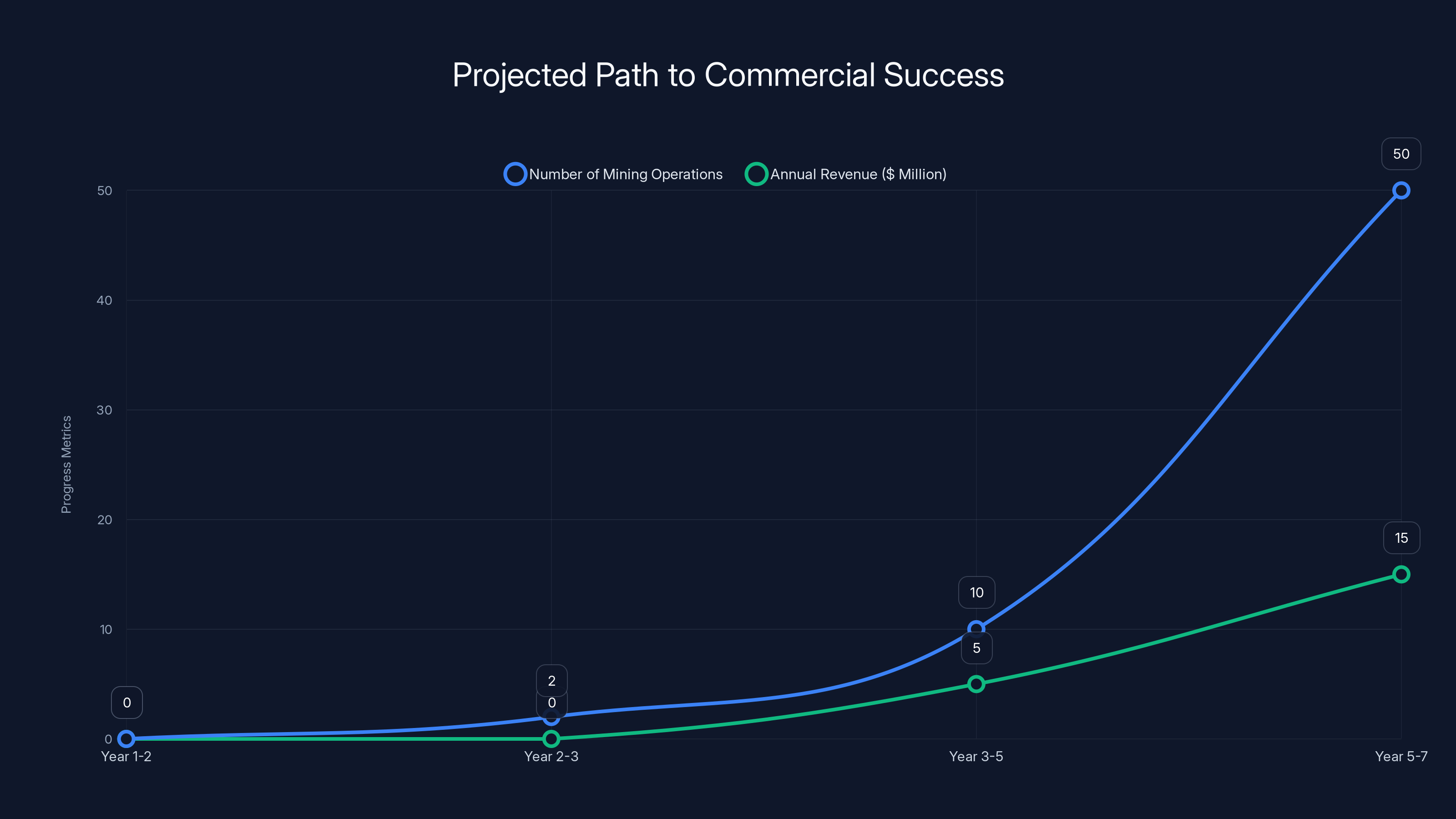

This conservatism extends the adoption timeline but isn't necessarily bad. It ensures that only proven technology gets deployed. Transition should expect 2-3 years from successful third-party validation to first commercial deployment. Then another 2-3 years to get multiple mining operations onboard. The timeline is measured in years, not months.

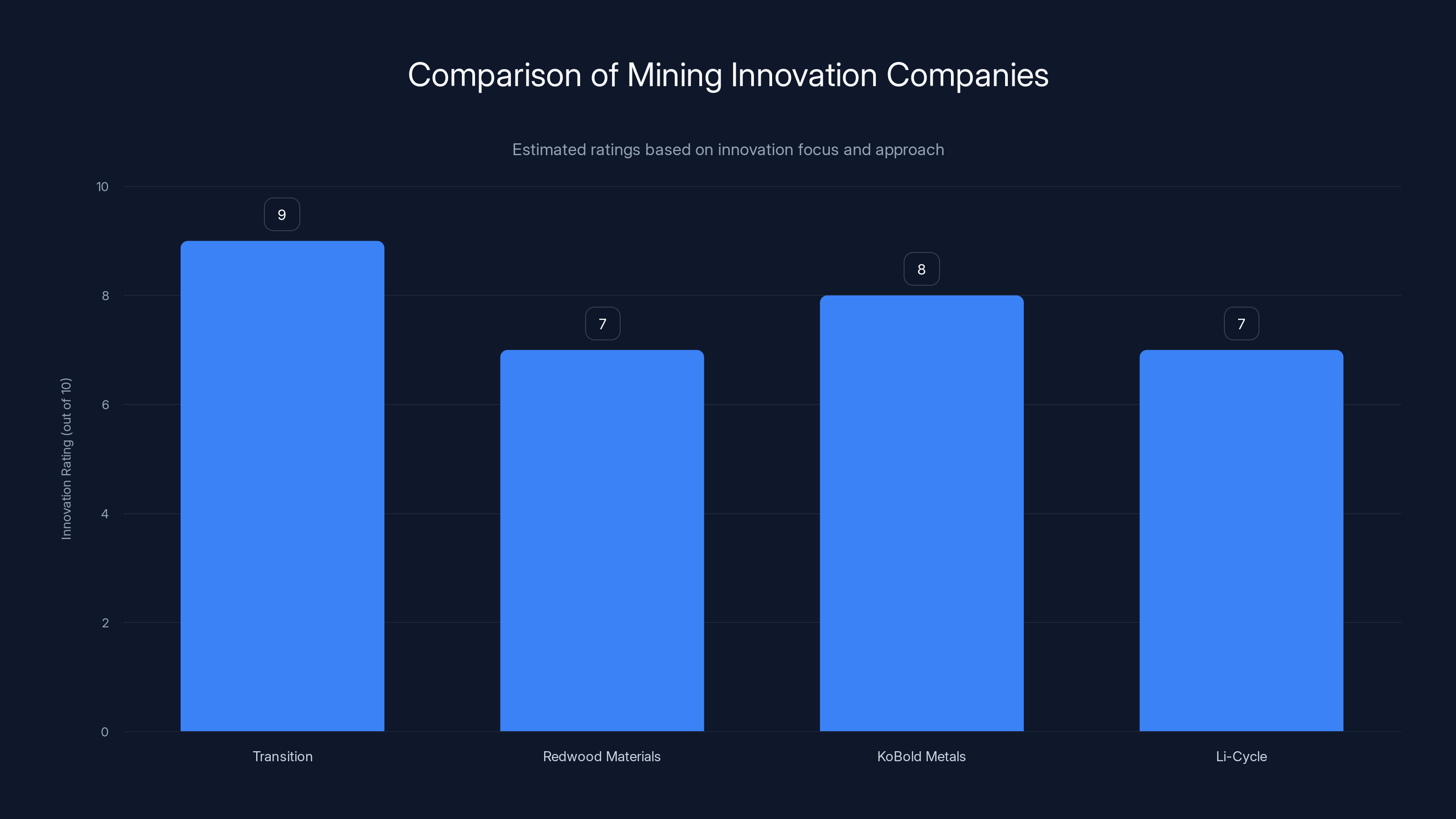

Transition leads in innovation with its unique biological approach to mining efficiency, setting it apart from competitors focused on recycling or AI-driven discovery. Estimated data.

Part Six: Why Microbial Technology Matters for Critical Minerals

The Biotech-Materials Interface

Transition Metal Solutions represents a convergence of two previously separate worlds: biotechnology and materials science. For decades, they've been siloed. Biotech companies worked on pharma and agriculture. Materials companies worked on metals and minerals. They didn't talk much.

Climate change and material shortage are forcing integration. Materials companies realize biology offers tools they haven't considered. Biotech companies realize there are massive markets in industrial minerals if they can solve technical problems. Transition is at the intersection.

This convergence is going to accelerate. Every critical mineral has biological extraction opportunities. Nickel leaching can be optimized. Lithium extraction from geothermal brines has biological components. Even rare earth separation has biological pathways. The mineral industry is waking up to biotech as a toolkit.

Transition isn't alone. Other startups are exploring biobleaching for different minerals. Universities are researching microbial extraction methods. The field is nascent but growing rapidly.

Companies that figure out how to apply biotechnology to materials extraction are sitting on multi-billion-dollar opportunities. The markets are enormous. The technical challenges are substantial but solvable. The regulatory framework is evolving but generally favorable.

Implications for Mineral Supply Chains

If Transition and similar technologies succeed, the entire economics of mineral supply chains shift. Current thinking assumes new mining is the only way to increase supply. But supply can also increase through efficiency. A 20-30% boost in extraction efficiency is equivalent to developing new mines without the environmental impact, permitting delays, or capital intensity.

That changes geopolitics too. Countries with existing large mines become more powerful. Chile and Peru control 60% of global copper. If they can extract 50% more copper from their existing operations, they become even more dominant in supply. Conversely, geopolitical risk decreases because you're not as dependent on developing mines in difficult jurisdictions.

It also changes the economics of lower-grade ore. As ore grades decline (which they have been), extraction efficiency becomes more economically important. A technology that boosts extraction by 20% from 0.8% ore grade is worth more than the same 20% boost from 1.2% ore grade. This means Transition's technology actually becomes more valuable as ore quality degrades over time.

Integration with AI and Predictive Mining

Transition's path to eventually predicting optimal additives for new mines without extensive testing is a machine learning problem. Feed the model data on ore composition, microbial community genetics, environmental parameters, and additive formulations, then predict optimal output.

This integrates neatly with broader AI-driven mining trends. Mining companies are increasingly using AI for mine planning, equipment optimization, and predictive maintenance. Integrating Transition's microbial optimization into that stack is a natural fit.

Ko Bold (the minerals startup that raised $537 million) uses AI to identify mineral deposits. If they or companies like them also use AI to optimize extraction efficiency, they're compounding competitive advantage. Better mineral detection plus better extraction equals dominant mineral supply control.

Transition could position itself as a critical component of the next-generation mining stack: discover minerals with AI, develop them with advanced geology, extract them more efficiently with microbial optimization.

Part Seven: The Competitive Landscape

Who Else Is Working on This?

Transition isn't entirely alone. There are other companies working on bioaugmentation and microbial optimization for mining. Some are traditional mining services companies experimenting with biological additives. Others are biotech startups focused on specific minerals.

The competitive advantage for Transition is multi-fold. First, they got to this problem early. Earlier teams are claiming intellectual property territory. Second, their specific approach of community optimization rather than strain isolation appears more scientifically sound than competitor approaches. Third, they have funding and investor support.

But competition will increase. Once Transition validates their approach, other well-funded biotech companies will enter the space. Mining giants might develop in-house capabilities. The barriers to entry aren't enormous—it's mostly specialized knowledge and investment capital.

Transition's sustainable advantage is probably data. As they work with more mines and accumulate results, their machine learning models improve. They learn the patterns that optimize extraction across different ore types and conditions. That's a moat that gets stronger over time.

Potential from Mining Giants

Major mining companies have research budgets and operational data that startups will never have. Rio Tinto, BHP, Antofagasta, and others know their microbial communities deeply. They understand the specific geology and processing challenges in their mines. If they decide to optimize extraction efficiency, they have tremendous internal resources.

However, large companies also move slowly. They have legacy processes, capital investments in existing infrastructure, and organizational inertia. A startup can move faster, take risks, and potentially beat incumbents to a breakthrough.

Large companies will probably acquire successful startups rather than build from scratch. That's typical in mining tech. An acquisition lets them deploy proven technology across their mine portfolio quickly. For Transition, an acquisition by a major mining company could be an excellent exit. For investors, it means returns within 5-7 years rather than building an independent company over decades.

Estimated data shows that while

Part Eight: Scaling Challenges and Capital Requirements

From $6M Seed to Commercial Reality

Six million dollars is decent funding for a biotech startup, but it's not enormous for a mining technology company. That capital needs to cover:

- Third-party lab validation work

- Demonstration heap construction and operation

- Multiple site testing and data collection

- Regulatory approval and documentation

- Team expansion (especially technical and business development staff)

- Intellectual property protection (patents, trade secrets)

If each major milestone costs $1-1.5 million, the seed round funds maybe 4-6 major milestones. That gets them through validation and one demonstration heap, but probably not global deployment.

A Series A round (likely $20-50 million range) would be needed to fund multiple demonstration sites, regulatory approvals in different jurisdictions, and early commercialization. That assumes positive results from seed-round work.

Total capital to get from current state to profitable, deployed technology at multiple mining sites probably totals $50-100+ million over 5-7 years. That's reasonable for a mining tech company but substantial for a startup.

Go-to-Market Strategy

Transition probably won't go direct-to-mine initially. Too risky for mine operators. Instead, they'll probably partner with mining services companies that already work with mining operators. These companies have relationships, trust, and operational expertise.

Alternatively, they might partner with one or two major mining companies that operate enough mines to justify investment in validation and implementation. Get one major player to adopt the technology, prove it works at scale, then use that success to recruit others.

A third path: work through toll processing or mineral trading companies that buy ore and process it. If you can prove additives boost extraction for tollers, they become advocates within the mining community.

International Expansion Complexity

Copper mining spans the globe, but supply is concentrated. Chile, Peru, Indonesia, China, and Australia represent 60%+ of global production. Transition needs to succeed in these markets to matter at scale.

Each country has different regulations, mining cultures, and technical expertise. A solution validated in Chile might require different configurations in Peru due to different ore types. China's mining is partly state-controlled, creating different business model requirements. Australia has stringent environmental regulations.

International expansion adds complexity and cost. But it's necessary to achieve market scale. A company that only works in one country will never be a meaningful player in global copper supply.

Part Nine: Financial Impact Projections

Potential Value Creation

Let's do some back-of-envelope math on what success looks like financially.

Global copper extraction is roughly 20 million tons annually from about 1,000 operating mines. A 20-30% boost in extraction efficiency is equivalent to creating 4-6 million tons of additional annual copper supply. At current prices around

Transition doesn't capture all of this. Mining operators capture most through improved margins. But if Transition takes even 2-5% of the value they create (through additive sales, consulting fees, or licensing royalties), that's

Actually reaching that scale takes time. But the math shows why investors are interested. The total addressable market is enormous.

For an earlier calculation, consider a single mid-sized mine processing 50,000 tons of ore per year. If Transition improves extraction by 20%, that's 80 tons of additional copper. At

Applied to 100 mines, that's

Timeline to Profitability

Assume Transition is breakeven at around

That's a 10-year path from founding to scale. Long by software startup standards. Normal for materials and industrial tech. Investors should expect this timeline.

The startup is projected to scale from 0 to 50 mining operations and achieve $15 million in annual revenue by Year 5-7, assuming successful technical validation and market adoption. Estimated data.

Part Ten: Risks and Failure Modes

Technical Risks

The biggest technical risk is that results don't translate from lab to field. This is the most common reason biotech startups fail. Controlled conditions hide complexity. Real-world conditions reveal it.

Second technical risk: the additive formulations don't generalize across different ore types and mines. If Transition needs to completely reformulate the cocktail for every mine, it becomes a custom-chemistry operation rather than a repeatable platform. That's lower margin, longer timelines, and harder to scale.

Third technical risk: competitive alternatives emerge. Maybe large mining companies develop in-house solutions faster than expected. Maybe other startups find better approaches. Maybe biological approaches to extraction optimization don't work as well as hoped and chemical extraction methods improve instead.

Market Risks

Market risk is real but not enormous. Copper shortage is widely recognized as a genuine problem. Mining companies desperately want solutions. But adoption could still be slower than expected.

Alternative solutions could emerge. Major breakthroughs in copper recycling might reduce primary mining demand. New technologies might enable extraction from lower-grade ore without bioleaching. Dramatic improvements in battery chemistry might reduce copper intensity of energy storage.

Geopolitical disruption to copper supply from South America (where most global copper is mined) could reduce demand for efficiency improvements by accelerating new mine development elsewhere.

Execution Risks

Transition is led by domain experts (Sasha Milshteyn appears to have microbiology/mining background), but building a commercial company is different from scientific discovery. Hiring the right team, managing investor expectations, navigating regulatory processes—these are hard.

Acquisition risk: if mining giants decide they want this technology and can't acquire it, they might develop competing solutions or lobby against regulatory approval. Transition could get squeezed out of their own market by better-resourced incumbents.

Regulatory Risks

Environmental regulations could tighten in ways that make additives problematic or require extensive additional testing. Mining permitting in new jurisdictions could slow deployment. Unexpected interactions between additives and local environments could trigger regulatory attention.

Likely: any of these could delay commercialization. Less likely (but possible): major regulatory obstacles could derail the entire approach.

Part Eleven: What Success Actually Requires

Milestone-Based Path to Success

Here's a realistic path to commercial success:

Year 1-2 (Seed round work):

- Third-party validation of lab results

- Multiple successful tests at different ore types

- Build dataset on additive formulations and outcomes

- Establish regulatory and compliance framework

Year 2-3 (Series A work):

- Demonstration heaps at 2-3 different mining sites

- Real-world performance at 50-70% extraction (vs. lab 90%)

- Publication or controlled release of results to build credibility

- Preliminary conversations with major mining operators

Year 3-5 (Series B and early commercial):

- First commercial contracts with 3-5 mining operations

- Operations scaling across 10+ mines

- International expansion (Chile, Peru)

- Build proprietary data advantage through accumulated results

Year 5-7 (Scale phase):

- 50+ mining operations using Transition's additives

- $10-20 million annual revenue

- Profitable or near-profitable operations

- Potential acquisition by major mining company or IPO consideration

The timeline is long but achievable if technical validation succeeds.

Critical Success Factors

-

Third-party validation actually works: This is the gating factor. If independent labs confirm results, everything else becomes possible.

-

Economics pencil out for mining operators: The value proposition has to be genuinely compelling (ROI in months, not years).

-

Technology generalizes: It needs to work across different ore types and mine types, not just the one mine where it was developed.

-

Team execution: The startup needs strong technical, business, and operational leadership.

-

Capital availability: Funding needs to be available for each milestone. If capital markets freeze, progress stalls.

-

Mining operator adoption: Even proven technology doesn't sell itself. Transition needs to overcome conservatism and build strong partnerships.

Part Twelve: Broader Implications for Materials Science and Climate Tech

Biotech as a Critical Infrastructure Technology

Transition's approach signals something important: biotechnology isn't just for pharma and agriculture. It's increasingly a materials and infrastructure technology. That changes how we think about biotech investment and capability building.

Climate transition requires enormous amounts of minerals. Biology offers tools to extract them more efficiently. This creates a new investment thesis: biotech for materials. Companies that crack biological approaches to mineral extraction, metal recycling, or materials manufacturing are going to be enormously valuable.

Universities should be training materials scientists who understand biology. Biotech companies should be exploring mineral applications. Materials companies should be hiring microbiologists. The interdisciplinary boundaries are breaking down.

The Case for Efficiency Over Discovery

For decades, the mineral industry has focused on discovery: finding new deposits, opening new mines, developing new geological prospects. Transition's approach inverts that: extract more from what we're already mining.

From a climate perspective, efficiency is often better than growth. Extracting 50% more copper from existing mines is better than opening new mines in frontier territories. Using biology to achieve that efficiency is elegant and scalable.

This could shift thinking across the entire materials industry. What if the path to meeting material demand isn't primarily through new mining, but through smarter extraction from existing operations?

It's not either/or. We probably need both new mining and efficiency improvements. But the emphasis might shift toward efficiency as it becomes technically proven and economically attractive.

Implications for Supply Chain Resilience

More efficient copper extraction could actually improve global supply chain resilience. If Chile improves extraction efficiency and increases output by 20%, that strengthens their market position but also diversifies supply sources. Geopolitical concentration risk decreases when production increases without requiring development of mines in new jurisdictions with new political risks.

From a climate standpoint, improving supply resilience without expanding mining footprint is nearly perfect. It addresses shortage concerns without new environmental impacts.

Part Thirteen: The Competitive and Economic Landscape

How Transition Compares to Other Mining Innovation

Other mining startups are working on different challenges: precision ore sorting, sensor networks for detection, AI for mine planning. Transition is unique in addressing extraction efficiency at the biological level.

Comparable companies might include:

- Redwood Materials: Recycling lithium-ion batteries. Different material but similar core challenge—get more valuable material from complex sources.

- Ko Bold Metals: Finding new deposits using AI. Different approach (discovery vs. efficiency) to the same problem (copper shortage).

- Li-Cycle: Lithium recycling. Similar positioning (efficiency and supply augmentation vs. mining).

Transition's specific advantage is the biological approach. It's novel enough that intellectual property protection should be available. It's differentiated from competitors working on materials flow, sensor technology, or mine planning.

Pricing Power and Margin Structure

Transition has genuine pricing power if the technology works. Mining operators will pay for extraction improvements that generate hundreds of thousands in annual value. The additive costs are probably low relative to value created, allowing Transition to capture 10-20% of value creation and still be attractive to customers.

Margin structure in mining services is typically healthy. Gross margins on specialized services often exceed 70-80%. Transition probably targets 60-70% gross margins on additive sales, plus additional margin on consulting and optimization services.

A company achieving

Part Fourteen: Regulatory and Environmental Considerations

Environmental Permitting in Key Markets

Chile, Peru, and Indonesia are the first-tier markets for Transition. Chile has become increasingly strict on mining environmental standards. Peru faces political risk around mining. Indonesia has been tightening restrictions on extractive industries.

But the environmental story helps. Using inorganic additives that are already present in mining sites to improve extraction efficiency shouldn't trigger major regulatory resistance. If anything, it might be viewed favorably as a way to reduce new mining.

Transition will need to:

- Document that additives are safe and already present in mining sites

- Show that treatment improves not just copper extraction but overall environmental outcomes

- Work with local regulatory bodies in each country

- Possibly fund independent environmental assessments

None of this is unusual for mining innovation. It's doable within the $6 million seed budget for initial market validation.

Water and Tailings Considerations

Heap leaching uses water, and water is increasingly constrained in mining regions. An efficiency improvement that enables existing mines to increase copper extraction without proportionally increasing water consumption is valuable.

Transition's approach probably doesn't significantly increase water needs. The additives work by optimizing microbial activity, not by requiring additional processing steps. This is actually an environmental advantage worth highlighting.

Tailings management is another consideration. Mining generates tailings—waste rock. More efficient extraction means less tailings per unit copper. That's an environmental win. Mining operators will appreciate this because tailings management is expensive and increasingly regulated.

Part Fifteen: Investment and Exit Scenarios

Path to Acquisition by Major Mining Company

Most likely exit: acquisition by Rio Tinto, BHP, Antofagasta, or another major mining company within 5-7 years post-seed. Once Transition proves the technology works commercially, major mining companies will want to deploy it across their global mine portfolio.

Acquisition valuation depends on demonstrated commercial success. If Transition reaches

For seed investors who invested at modest valuations (probably $20-40 million post-money), this represents 5-20x returns over 5-7 years. For an early-stage climate tech investment, that's reasonable.

Independent Company Path

Less likely but possible: Transition remains independent and scales to become a substantial mining services company. This requires longer runway, more capital, and more operational complexity. But if the technology proves dramatically successful, the TAM is large enough to support an independent company.

As an independent company, Transition could eventually IPO or be acquired by a financial buyer or private equity firm. This path is harder and takes longer but potentially more lucrative for investors.

Strategic Partnership Path

Middle path: Transition partners with one or more major mining companies or mining services companies rather than being fully acquired. The partner handles deployment and customer relationships. Transition handles technology development and R&D. This preserves upside while providing capital and distribution.

This path is often less appealing to VC investors (lower returns than acquisition) but could be attractive to founders who want to maintain independence.

Part Sixteen: Why Timing Matters Now

The Convergence of Multiple Pressures

Transition is entering the market at a moment of unique convergence. Copper demand is spiking due to electrification and AI. New mining is becoming harder and more expensive. Environmental regulations are tightening. Existing mines are mining lower-grade ore. The economics of extraction efficiency have never looked better.

Ten years ago, this technology wouldn't have been fundable. Copper prices were lower, shortage concerns were smaller, and extraction efficiency wasn't a priority. Now it's urgent.

Timing doesn't guarantee success, but it increases probability. Transition is working on the right problem at the right moment when multiple factors align to make the solution valuable.

Climate Tech Momentum

Climate tech has shifted from "nice to have" to "essential infrastructure." Governments and investors are backing it massively. Energy transition requires materials. Materials shortage could bottleneck transition. Technologies that augment material supply without expanding mining footprint fit neatly into climate investment theses.

Transition benefits from favorable climate tech tailwinds. Investors are actively looking for solutions to mineral shortage. Mining companies are under pressure to increase production sustainably. The market is ready.

Conclusion: The Future of Mining Is Biological

Transition Metal Solutions is betting on a specific technology: using microbial probiotics to boost copper extraction. But the company represents something bigger: the convergence of biotechnology and materials science.

For decades, we've thought about mineral shortage as a discovery problem. Find more copper. Open new mines. But that's becoming harder and more costly. The world needs a new approach.

Biology offers one. Microbes are already working in copper mines. They've been doing it for millennia. We're just beginning to understand and optimize their work. With the right additives, the right understanding, and the right microbial communities, we might extract 50% more copper from existing mines without finding a single new ton of ore.

That changes the math. If Transition's technology works at scale, copper shortage becomes solvable through efficiency rather than requiring massive new mining operations. New mines won't disappear—we'll probably still develop them—but efficiency improvements could substantially ease the timeline and economic pressure.

The bigger insight: this same approach applies to nickel, lithium, rare earths, and other critical minerals. The biotech-materials interface is where breakthrough innovation is happening. Companies that master biological approaches to extraction will own the materials infrastructure of the energy transition.

Transition Metal Solutions probably won't exist as an independent company in 10 years. It'll either be acquired, scaled dramatically, or outcompeted. But regardless of Transition's specific fate, the approach it's pioneering is the future. Biology is coming to mining. And that changes everything.

The world is facing genuine material shortage. Copper is just the most urgent. Companies that solve extraction efficiency through biological innovation are sitting on potentially trillion-dollar problems. If Transition cracks this—if they prove that microbial probiotics genuinely work at scale—the impact on supply chains, climate transition, and mining economics will be enormous.

We're still in the very early stage. Third-party validation hasn't happened yet. Demonstration-scale testing is months or years away. Commercial deployment is years beyond that. But the technical approach is sound. The market need is real. The capital is interested. And the team is credible.

Sometimes the most important innovations look simple until you understand the biology, chemistry, and economics underneath. Transition Metal Solutions might be that kind of innovation: simple elegant approach to genuinely intractable problem. Watch this space. Microbes might be the answer to mineral shortage.

FAQ

What exactly are probiotics in the context of copper mining?

In mining, "probiotics" refers to inorganic chemical additives that optimize microbial communities already present in ore heaps. Unlike biological probiotics that add live organisms, mining probiotics are mostly inorganic compounds that create conditions where existing microbes perform more efficiently at extracting copper from ore. Transition Metal Solutions' proprietary formulation adjusts concentrations and combinations of these additives to nudge microbial communities toward better copper liberation without introducing new organisms or novel chemicals.

How does Transition's approach differ from traditional microbial inoculation in mining?

Traditional approaches isolate high-performing bacterial strains, grow them in large quantities, and inoculate ore heaps with the hope they'll thrive. This method often fails because individual strains compete with established microbial communities, the imported organisms have viability loss during transport and application, and isolated strains lack the support of complementary species. Transition instead works with the existing microbial community already present (which is over 90% unknown species) and applies inorganic additives that optimize the entire community's performance rather than boosting single species.

What's the expected improvement in copper extraction from using these additives?

Lab results show extraction rates improving from 60% to 90% using Transition's additive cocktail. Field performance is expected to be more modest but still significant. Traditional heap leaches extract 30-60% of copper depending on ore quality and mine conditions. With Transition's treatment, expectations are 50-70% extraction, potentially higher. The exact improvement varies by ore type, microbial community composition, and local conditions, which is why Transition tailors additive formulations for each mine after initial testing.

Why does Transition need a different additive formulation for each mine?

Every mine has a unique microbial community shaped by local geology, climate, ore composition, and historical mining practices. The specific microorganisms present, their metabolic capabilities, and ecological relationships vary by location. A formulation optimized for one mine's community might be suboptimal for another. Transition's testing process characterizes each mine's microbial community and develops a customized cocktail that nudges that specific community toward better copper extraction. Over time, as they accumulate data from many mines, machine learning models should predict optimal formulations without extensive testing.

What's the environmental impact of using these additives in mining operations?

The additives are mostly inorganic compounds already present at mining sites, just in different concentrations or combinations. This minimizes environmental risk compared to introducing novel chemicals. More efficient copper extraction actually reduces environmental impact by decreasing the need for new mining operations, reducing water and energy consumption per unit copper extracted, and generating less tailings waste per ton of ore processed. Environmental regulators should view extraction efficiency improvements favorably compared to traditional approaches.

How long before Transition's technology reaches commercial deployment at actual mining operations?

Realistic timeline spans 3-5 years. Current phase involves third-party validation of lab results (1-2 years). Next phase is demonstration-scale testing at sites containing tens of thousands of tons of ore (1-2 years). Only after successful field demonstration will mining operators likely implement the technology commercially. Even then, adoption will be gradual as operators test and verify results. Global deployment across hundreds of mining operations probably spans 5-10 years post-seed round.

Could this technology solve the global copper shortage?

Partially, yes. If Transition's technology achieves 20-30% improvement in extraction efficiency across global copper mines, that's equivalent to adding 4-6 million tons of annual copper supply. That would substantially ease shortage pressures without requiring all the new mining that would otherwise be necessary. However, it's probably not a complete solution—some new mining will still be needed. But efficiency improvements could buy the transition time to develop alternatives to copper-intensive technologies and push out the timeline of severe shortage.

Why haven't mining companies developed this technology themselves if the potential value is so large?

Mining companies are operationally conservative and focused on immediate production. R&D budgets, while real, are often allocated to proven technologies rather than moonshot biology projects. Additionally, microbial biogeochemistry is outside most mining companies' core expertise. They excel at moving dirt and processing ore with established methods, not optimizing microbial communities. Startups and academic labs often solve problems that large companies don't prioritize, then get acquired or become partners when success is demonstrated. This pattern is typical in mining technology innovation.

What are the biggest risks that could derail Transition's technology?

Technical risk: results might not generalize from lab to field conditions across different ore types. Market risk: adoption could be slower than expected due to mining industry conservatism or emergence of superior alternative technologies. Execution risk: the startup might struggle with team building, regulatory navigation, or raising subsequent funding rounds. Competitive risk: major mining companies might develop competing solutions or biotech companies might pioneer superior approaches. Regulatory risk: environmental concerns about additives could trigger unexpected restrictions. None of these is likely to be fatal, but all could delay commercialization or reduce eventual market size.

Could Transition's approach work for other minerals like lithium or nickel?

Proof of concept exists for nickel bioleaching and lithium extraction from geothermal brines involves biological components. The underlying principle—using microbial communities to improve mineral liberation and extraction—is generalizable. However, each mineral presents unique challenges requiring custom research. Transition is currently focused on copper, but long-term success could position them or their competitors to apply similar approaches across critical minerals. That's part of what makes the broader biotech-materials convergence potentially transformative.

Try Runable for Your Research and Documentation

Use Case: Automatically generate research summaries and technical documentation from complex mining studies and scientific papers in minutes.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- Copper shortage of 25%+ by 2040 makes extraction efficiency critical to climate transition success

- Transition's approach optimizes entire microbial communities (90% unknown) rather than isolated strains for 50%+ extraction improvement

- Lab results show 90% extraction versus 60% baseline; field performance expected at 50-70% from current 30-60%

- A single mid-sized mine gains $800,000 annual value from 20% extraction improvement using inorganic additives

- Timeline to commercial deployment spans 3-5 years minimum; path to profitability at 100+ mining operations takes 5-7 years

- Biotech-materials convergence represents broader trend: biology increasingly critical to solving mineral shortage and supply chain resilience

Related Articles

- Game of Thrones: Knight of the Seven Kingdoms Almost Became a Film [2025]

- NASA's Commercial Space Station Crisis: Senate Demands Timeline [2025]

- Wikimedia's AI Partnerships: How Wikipedia Powers the Next Generation of AI [2025]

- Sesame Street on YouTube: 100+ Classic Episodes Now Streaming [2025]

- Wikipedia AI Licensing Deals: How Big Tech Is Paying for Knowledge [2025]

- Spotify Price Increase to $13: What You Need to Know [2025]

![Probiotics for Mining: How Microbes Could Solve the Copper Shortage [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/probiotics-for-mining-how-microbes-could-solve-the-copper-sh/image-1-1768491955040.jpg)