NASA's Commercial Space Station Crisis: Senate Demands Timeline

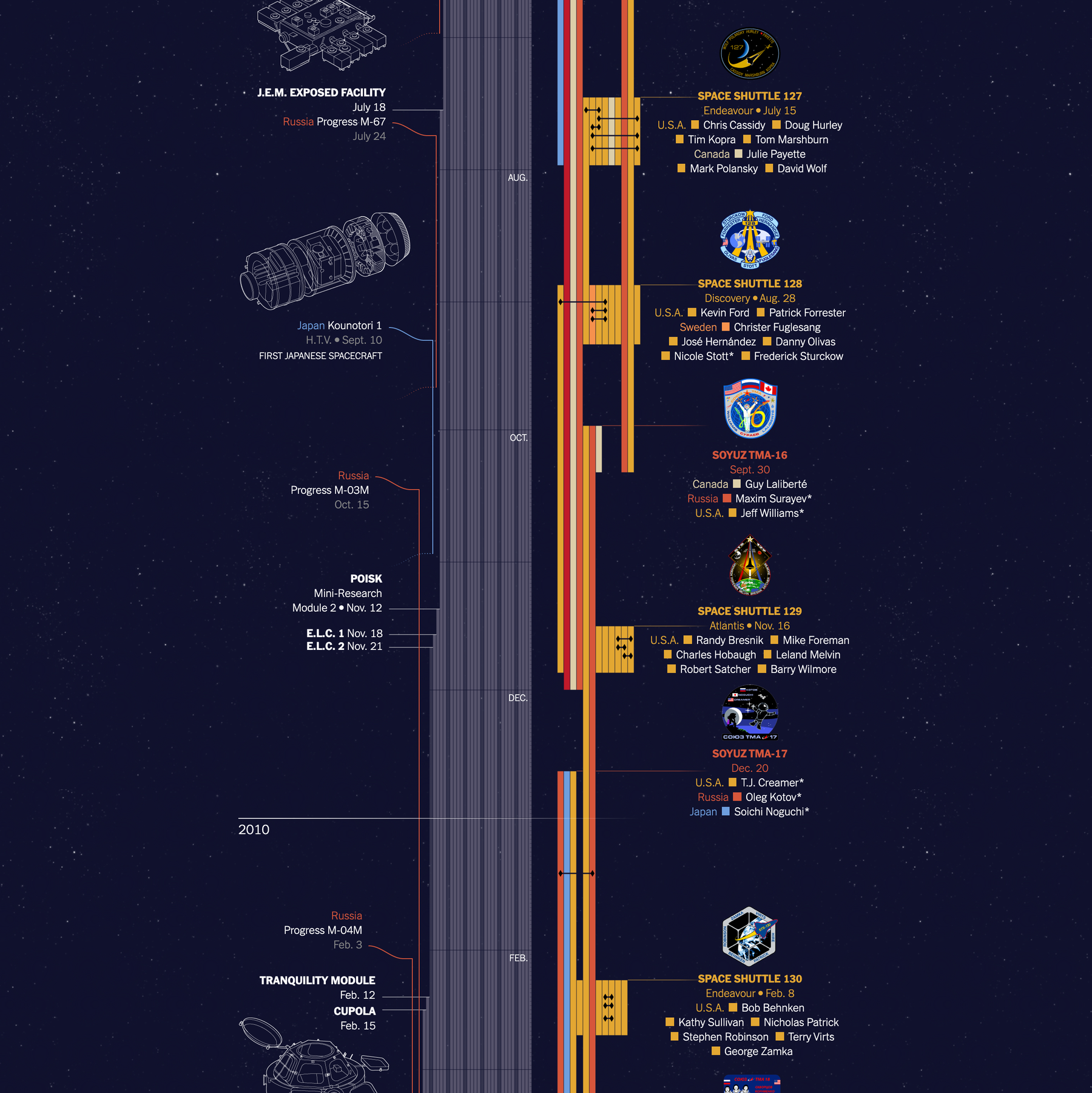

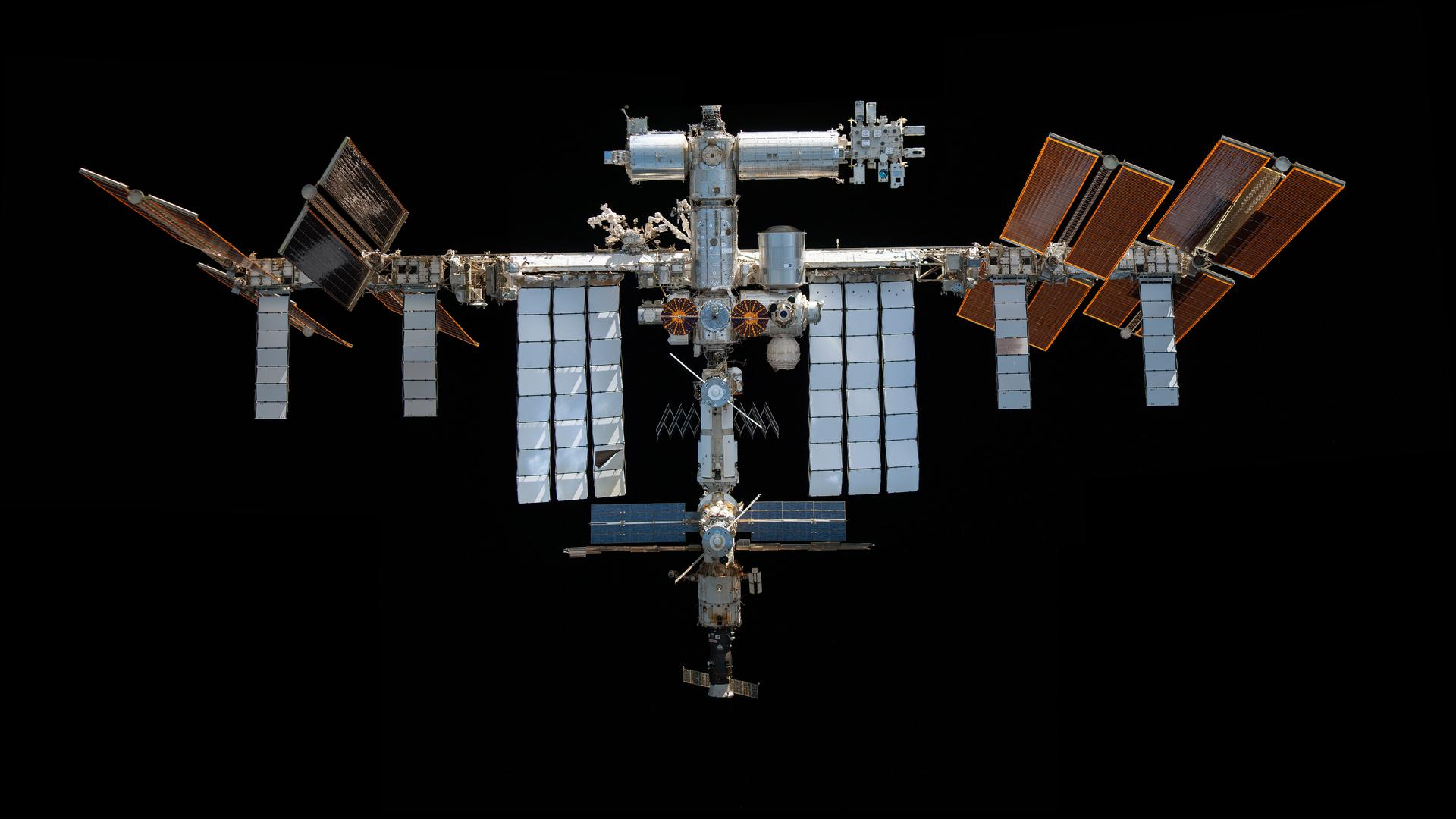

There's a ticking clock in low Earth orbit, and it's running faster than NASA wants to admit. The International Space Station, humanity's orbital research laboratory for over two decades, is scheduled to be deorbited in 2030. That gives the space agency roughly five years to transition continuous human presence in space to privately-owned commercial platforms. The math doesn't add up yet, and influential Senate staffers are losing patience.

In January 2025, Maddy Davis, a space policy staffer for Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, made her frustration public during remarks to the Texas Space Coalition. Her words cut right to the heart of an institutional problem that's been festering behind closed doors: NASA simply hasn't moved fast enough on the Commercial LEO Destinations program, the initiative meant to replace the aging ISS with privately-operated alternatives.

"Earlier today, I was having a briefing with NASA and begging for—we really needed that RFP released for CLDs like nine months ago," Davis said. "But here we are still begging for it." That request for proposals, the formal document inviting companies to bid on multi-hundred-million-dollar contracts, should have launched months ago. Instead, it's stuck in bureaucratic limbo, delayed by leadership changes, conflicting directives, and unclear requirements that leave private companies uncertain about how to proceed.

This isn't abstract space policy talk. It's a genuine crisis that affects everything from American spaceflight capability to geopolitical influence in orbit. Without commercial alternatives ready before 2030, the United States faces a scenario where there's literally no American astronaut in orbit for the first time since 1992. That's not just a technological setback—it's a strategic vulnerability that competitors like China are watching very carefully.

Here's what's really happening behind the scenes, why it matters, and what needs to change for continuous human spaceflight to survive the ISS transition.

The ISS Retirement Timeline: A Deadline That Came Too Fast

When NASA and international partners decided on a 2030 retirement date for the International Space Station, it sounded distant. That decision came in 2021, which seemed like plenty of time to develop and deploy replacements. But here we are in 2025, halfway through the window, and commercial platforms are still in early-stage development. The clock accelerates when you realize how long it actually takes to build and certify space stations.

The ISS itself is showing its age. Major components are now over 25 years old. The station was originally designed for 15-year operation, then repeatedly extended. Keeping it functioning requires constant maintenance, regular resupply missions, and careful management of aging systems. Extending beyond 2030 would mean even higher costs and increasing risk of catastrophic failures that could endanger crews.

But here's the political reality that Davis was hinting at: if commercial alternatives aren't operational before the ISS is deorbited, Senator Cruz has explicitly stated he's open to extending the station's life. That's not ideal—it's more expensive and riskier—but it's preferable to a human spaceflight gap where American astronauts can't access low Earth orbit at all.

The 2030 deadline was supposed to create urgency. Instead, it's becoming a nightmare scenario that Congress is now forced to contemplate.

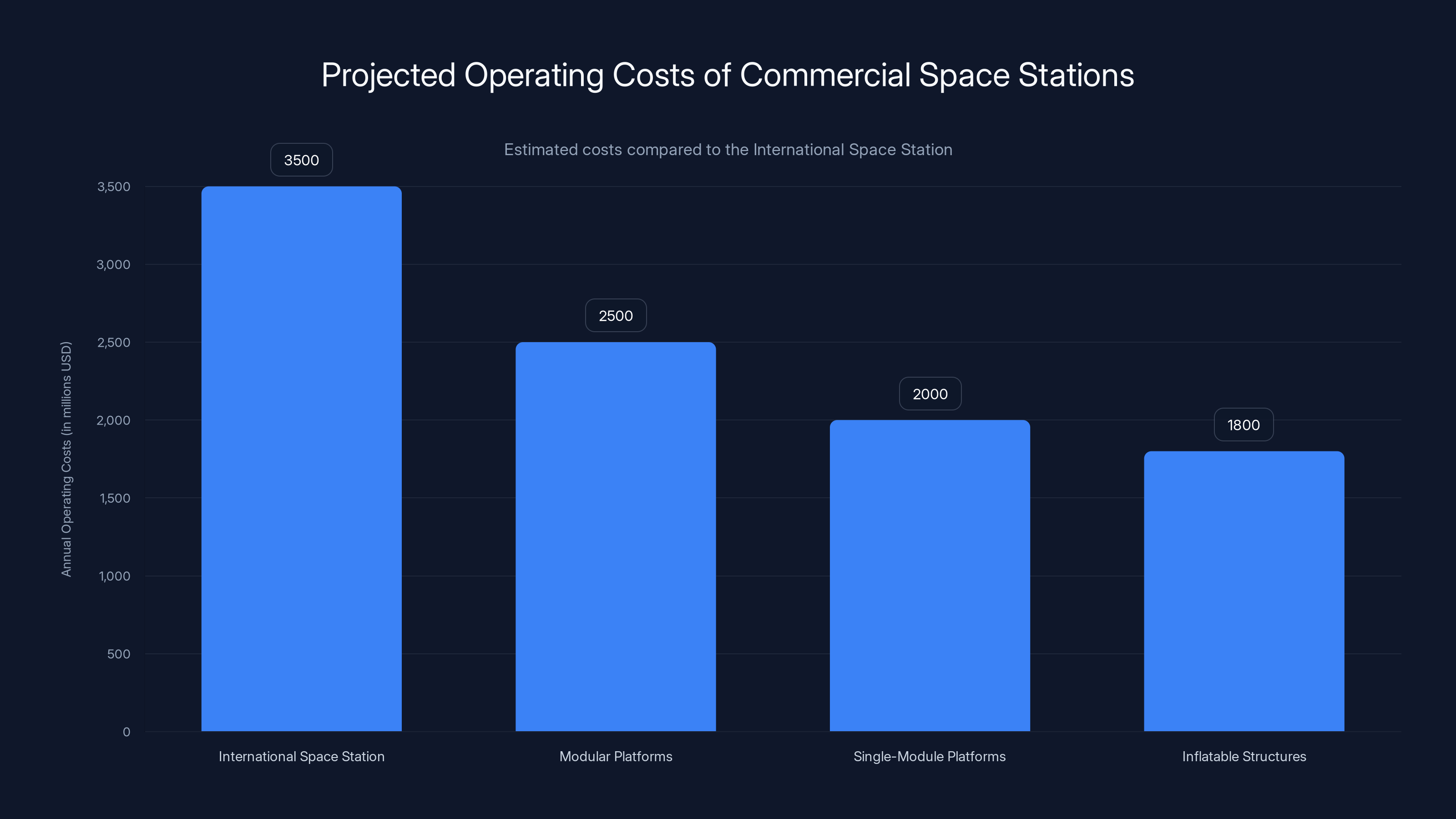

Estimated data suggests that commercial space stations will have lower operating costs than the ISS, with inflatable structures potentially being the most cost-effective.

Understanding Commercial LEO Destinations: What NASA Is Trying to Build

Commercial LEO Destinations, abbreviated CLDs, refers to a portfolio of privately-owned and operated space stations that would take over some of the functions of the International Space Station. The concept isn't revolutionary—it's based on decades of space station experience and the proven model of commercial cargo and crew vehicles that already service the ISS.

The program works like this: NASA provides seed funding to companies to develop initial concepts. These aren't full-funding contracts. They're development partnerships where companies use government money to prove their designs can work, then attract private investors and corporate clients to finance construction and operation. It's meant to create a sustainable market for microgravity research and manufacturing in orbit.

NASA previously funded four different companies under the initial phase of CLD development. Each company brought different technical approaches and business models. Some focused on module-based designs similar to ISS architecture. Others proposed different configurations optimized for manufacturing or research.

The next phase—Phase 2—is supposed to see increased competition. Instead of just maintaining current concepts, new companies can enter the competition. NASA will provide larger funding amounts, probably in the hundreds of millions of dollars per company, to the one or two finalists who demonstrate the most promise. These winners would then be responsible for actual construction and certification.

But Phase 2 can't even start without the request for proposals. That's the formal government document that outlines exactly what NASA is looking for, how much funding is available, what technical requirements must be met, and what the timeline looks like. Without it, companies are flying blind.

The Directive Chaos: How August 2024 Made Everything Worse

Then things got complicated. Last August, then-interim NASA Administrator Sean Duffy issued a new directive that fundamentally changed the rules for commercial space stations. The directive revised technical and operational requirements that companies would have to meet. On the surface, updating requirements makes sense—spaceflight technology evolves, lessons are learned, standards improve.

But the timing and scope of Duffy's directive raised red flags. It appeared to favor certain companies over others. Some interpreters saw it as potentially disadvantageous to companies that had already invested significant resources developing their initial concepts around the old requirements. Now they faced the prospect of expensive redesigns or being at a competitive disadvantage against companies that might pivot more easily to the new standards.

"Added a lot more gray to the process," as Davis diplomatically put it. For companies trying to attract private investment capital, that gray area is poison. Investors want clarity. They want to know exactly what NASA expects, how much it will pay, and what the timeline looks like. When government agencies suddenly change the rules mid-game, investor confidence evaporates.

The good news: new NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman is reviewing Duffy's directive and his team is reassessing the requirements. The bad news: that means more delays as the new administration figures out what the right standards actually are. Until they issue final guidance, companies are stuck in limbo, unable to finalize designs or investment pitches.

Isaacman's strengths lie in his business acumen, spaceflight experience, and communication skills, though institutional knowledge is an area for growth. Estimated data based on narrative insights.

The Staffing Crisis: Why Leadership Instability Cascaded Into Technical Delays

NASA's leadership turnover created a cascading set of problems that rippled through the entire commercial space program. Leadership changes meant new priorities, new perspectives, and new people trying to understand complex programs. When you change the top administrator, that person's vision for the agency's future suddenly becomes gospel. Entire strategic initiatives get re-evaluated.

That's not inherently wrong—new leadership should bring fresh thinking. The problem is the time lag. Leadership changes take months to cascade through the organization. New administrators need to get up to speed. They need to understand what their predecessor did and why. They need to develop their own vision for the agency. During that transition period, most programs just... wait.

The CLD program wasn't unique in experiencing delays. But it's particularly vulnerable to delays because it involves external partners—private companies with investors, employees, and deadlines. When government partners go quiet, private companies can't make plans. They can't commit capital. They can't hire specialized engineers or secure long-term contracts with suppliers.

Isaacman's arrival three weeks before Davis's comments suggests the delays might finally be ending. Early signals from his team seem positive. His handling of the Crew-11 situation—where Boeing's Starliner spacecraft ran into unexpected technical issues during astronaut testing—impressed both Davis and, presumably, other key stakeholders. Transparent communication and clear decision-making matter when you're trying to rebuild confidence in the space program.

The Request for Proposals Bottleneck: Why One Document Matters So Much

It might seem strange that a policy staffer for a powerful senator would devote significant political attention to a single government document. But the RFP isn't just paperwork. It's the actual mechanism that sets the whole competitive process in motion.

Once NASA issues the RFP, companies have a defined period—usually 60 to 90 days—to submit proposals. These proposals contain technical designs, cost estimates, development schedules, and plans for attracting private investment. NASA evaluates them against stated criteria. Winners get announced. Contracts are negotiated and signed. Then actual work begins.

Without the RFP, none of this happens. Companies can't officially submit bids. NASA can't conduct formal evaluations. The legal machinery that governs federal contracting can't engage. It's like a race that's supposed to start, but the starting gun never fires.

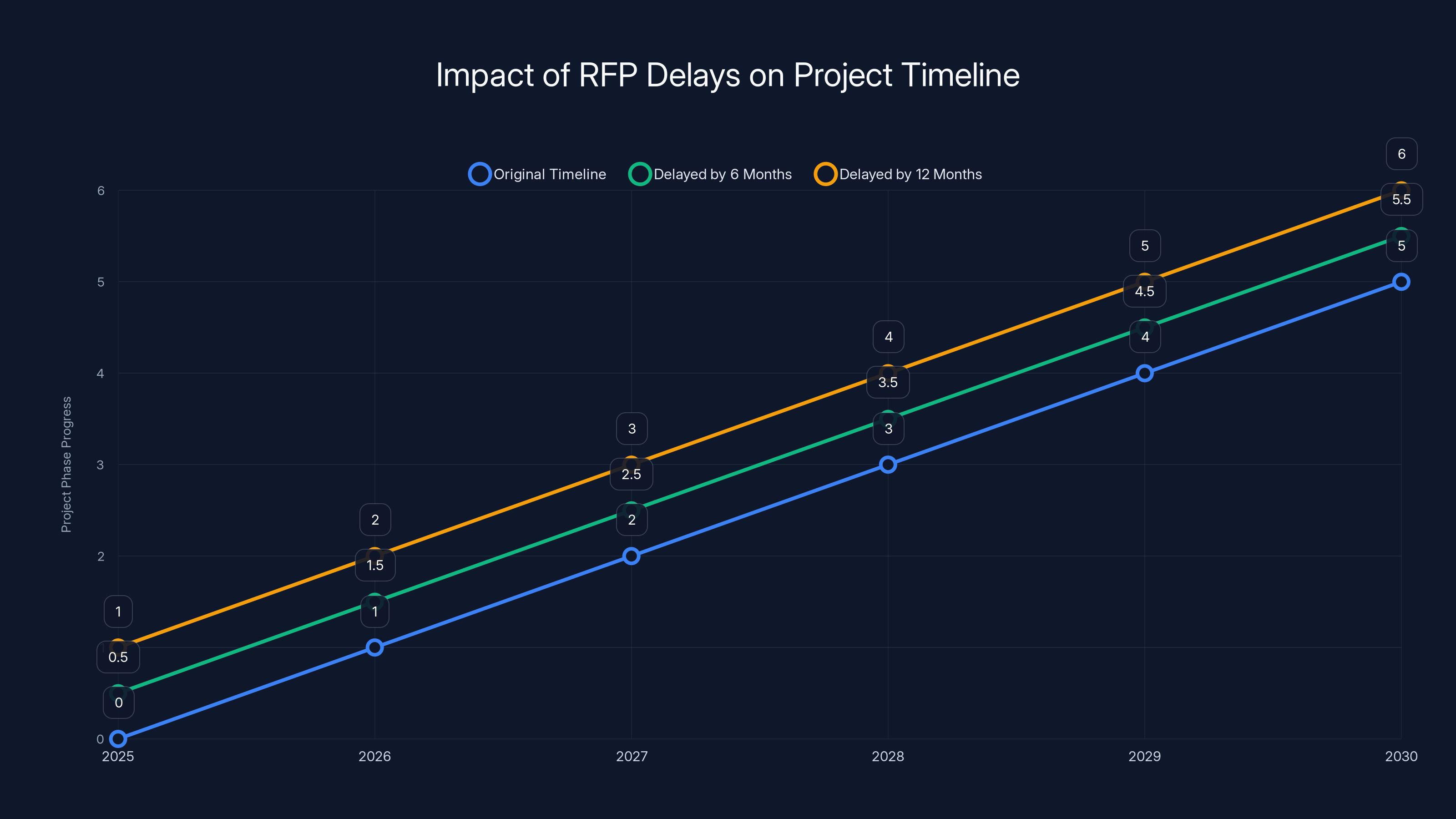

The nine-month delay Davis mentioned isn't just frustrating—it's actively damaging to the timeline. Every month that passes brings 2030 closer. Every month of delay compresses the schedule for construction, testing, certification, and human missions aboard new commercial platforms. If the RFP comes out in early 2025, and Phase 2 contracts are signed in late 2025, companies have barely five years to design, build, test, and certify hardware before the ISS is deorbited.

That's an aggressive but technically possible timeline. Extend the delays another six to twelve months, and suddenly it becomes infeasible. That's why Davis was so direct about the urgency.

Commercial Space Station Concepts: What Companies Are Actually Building

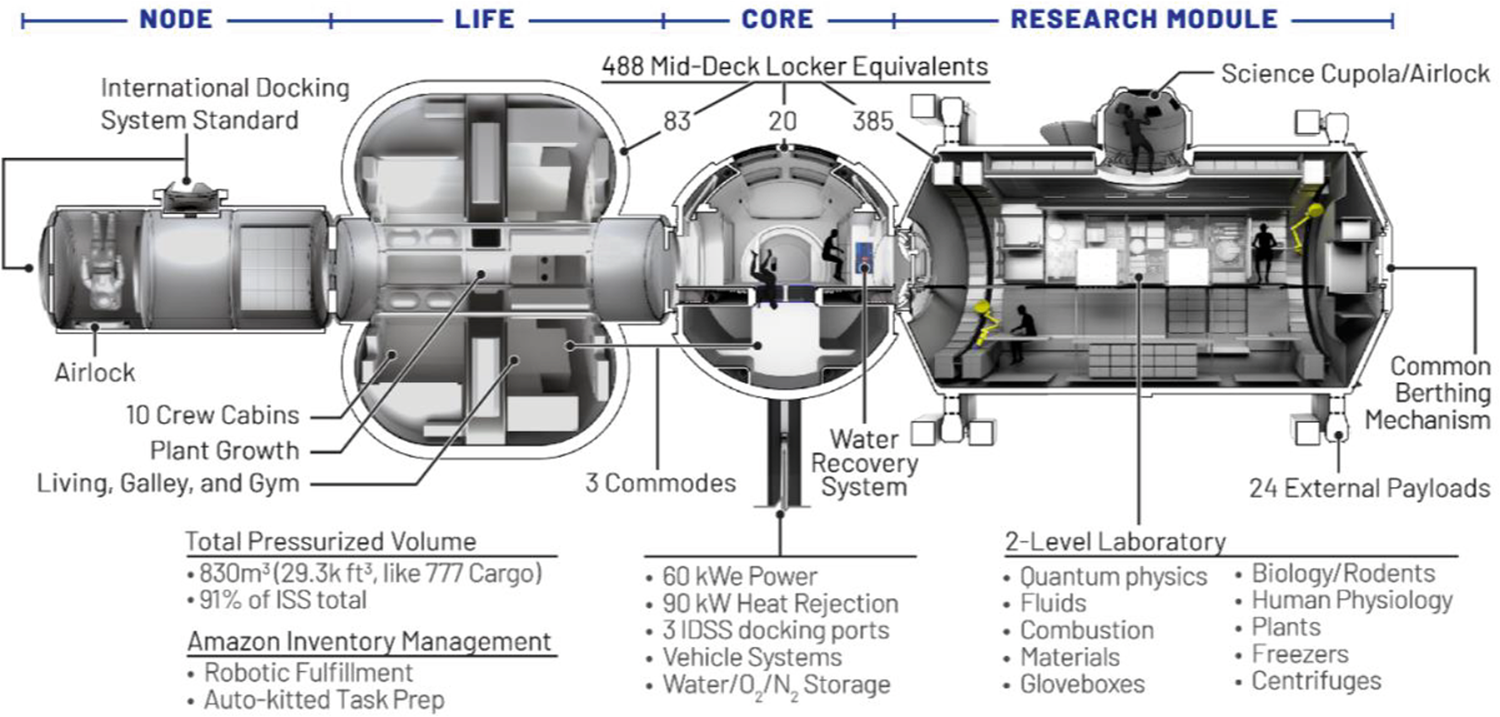

Before diving deeper into policy problems, it's worth understanding what these commercial platforms actually are. They're not ISS clones. They're purpose-built for different missions and business models.

Some companies are designing modular platforms—basically upgraded versions of ISS-style architecture. Modules connect to a central hub, equipped with docking ports for visiting vehicles and external attachment points for instruments and equipment. This architecture is well-understood and proven. It's evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

Other companies are pursuing different approaches entirely. Some are designing single-module platforms that are smaller and simpler, optimized for specific research applications rather than general-purpose use. Others are exploring inflatable structures that could launch more compact and expand in orbit, reducing launch costs significantly.

Each approach has tradeoffs. Modular designs offer flexibility and growth potential but are more complex. Simpler designs are faster and cheaper to build but offer less capacity and capability. The winning companies will probably be those that find the sweet spot between capability and cost, between proven technology and innovative cost reduction.

The point is that multiple companies are already working on this. They've invested their own capital. They've attracted investors. They're hiring engineers and planning construction facilities. They're not waiting for NASA's RFP—they're doing the work anyway because the market opportunity is clear. But the RFP clarifies exactly what NASA wants and how much it's willing to pay, which gives companies the final piece of information they need to make definitive investment commitments.

ISS operational costs are projected to increase slightly, while potential savings from commercial alternatives could grow significantly by 2030. Estimated data.

Boeing's ISS Extension Motive: Following the Money

One detail worth examining: Boeing has the contract to operate the ISS and would likely benefit from its extension beyond 2030. The company's interest in a longer operational life is entirely predictable from a business perspective. Extended ISS operations mean continued revenue, continued contracts, and continued employment of engineers and technicians dedicated to station management.

But there's a conflict of interest here. The company with the most to gain from delaying commercial alternatives is the company running the current system. That's exactly the kind of dynamic that makes career government staffers like Davis skeptical. You need independent verification that extending ISS operations is actually the right technical choice, not just the right financial choice for Boeing.

That's where congressional oversight matters. Staffers like Davis have no financial interest in which platform Americans use for microgravity research. They care about capability, cost, and schedule. Having Congress actively questioning delays forces NASA and contractors to justify decisions on technical merits rather than just on contractual convenience.

The political reality is that if commercial platforms aren't ready by 2029 or so, Congress will likely demand an ISS extension even if it's not ideal. That extension would probably come with additional oversight, new constraints, and demands for cost control. That's the backstop scenario—not what anyone wants, but better than a human spaceflight gap.

The Investor Confidence Problem: Why Companies Need Clarity

Here's something that pure space policy watchers sometimes miss: the companies developing these commercial platforms need to convince private investors that the business case is real. Those investors include venture capital firms, aerospace companies, and institutional investors looking for exposure to space industry growth.

Venture capital especially has a limited attention span and low tolerance for uncertainty. These investors want to understand the addressable market, the timeline to revenue, the competitive landscape, and the regulatory environment. When government partners go silent or suddenly change requirements, investor confidence gets destroyed. Venture firms start pulling back funding. Entrepreneurs get distracted by other opportunities. Talent moves to companies with clearer prospects.

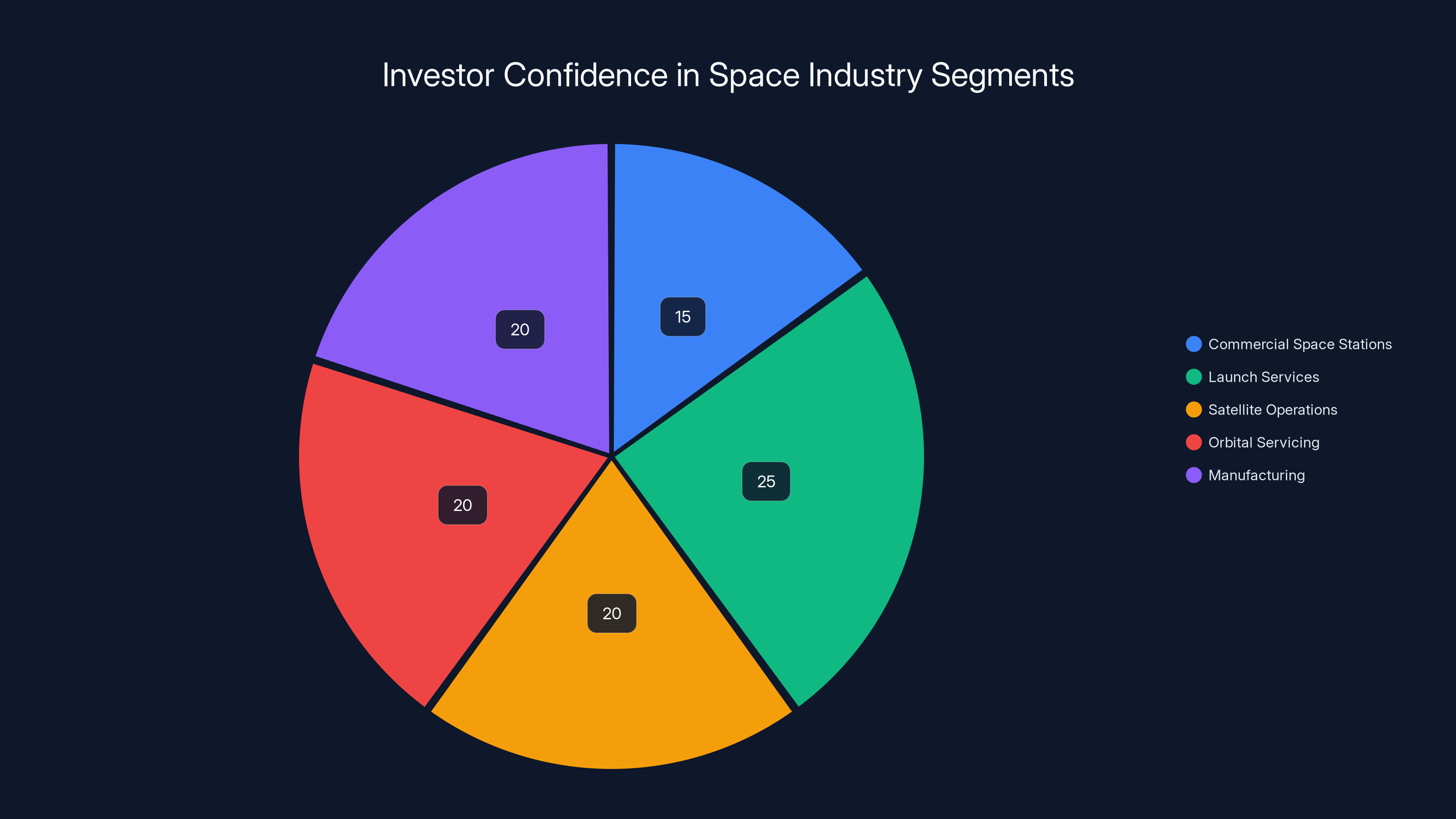

The consequence of the RFP delay and requirement changes isn't just that NASA's timeline slips. It's that companies might decide commercial space stations are too risky, too uncertain, and too dependent on government whims. They might redirect resources toward other space businesses with better clarity—launch services, satellite operations, orbital servicing, or manufacturing.

That would be catastrophic for the CLD program. NASA can't build a space station industry by itself. It needs partners that bring private capital, innovation, and commercial discipline. Without private investment, CLD becomes another government program competing for limited budget, vulnerable to every fiscal crisis and political dispute about spending.

Davis understood this dynamic. That's why she was so direct about demanding the RFP. It's the single most important document for giving private companies the clarity they need to commit resources.

Jared Isaacman's Early Track Record: Reasons for Cautious Optimism

Jared Isaacman brings an unusual background to the NASA administrator position. He's not a career government scientist or engineer. He's an entrepreneur who founded a payment processing company, sold it for a reported $500 million, and then became an accomplished pilot with interests in pushing the boundaries of spaceflight. He even flew to the International Space Station as a private mission participant, so he has hands-on experience with the system he's now managing.

That background could be an asset or a liability depending on execution. The asset side: he understands business, understands the private space industry firsthand, and has no institutional investment in the old way of doing things. He can think about how to create efficient markets for space services rather than just managing government programs.

The liability side: NASA is a massive, complex organization where institutional knowledge matters. Moving too fast or dismissing career staff opinions can create chaos. Understanding spaceflight is very different from managing an organization with 18,000 employees and a multi-billion-dollar budget spread across dozens of programs.

Davis's assessment after three weeks was positive. Specifically, she praised Isaacman's handling of the Crew-11 situation, where Boeing's Starliner spacecraft experienced technical anomalies during crewed testing that forced NASA to make difficult decisions about astronaut safety versus program schedule.

Isaacman's approach was apparently transparent and decisive. He communicated clearly with Congress, consulted with his team, and made decisions based on engineering merit rather than political convenience. For a brand-new administrator at a brand-new position, that's the kind of behavior that builds credibility with Congress and with the wider spaceflight community.

The real test will be whether Isaacman can accelerate the CLD program without rushing it to the point of creating problems. Getting that RFP released quickly matters, but releasing a bad RFP that's impossible to meet is worse than no RFP at all. The window is tight enough that there's no room for false starts.

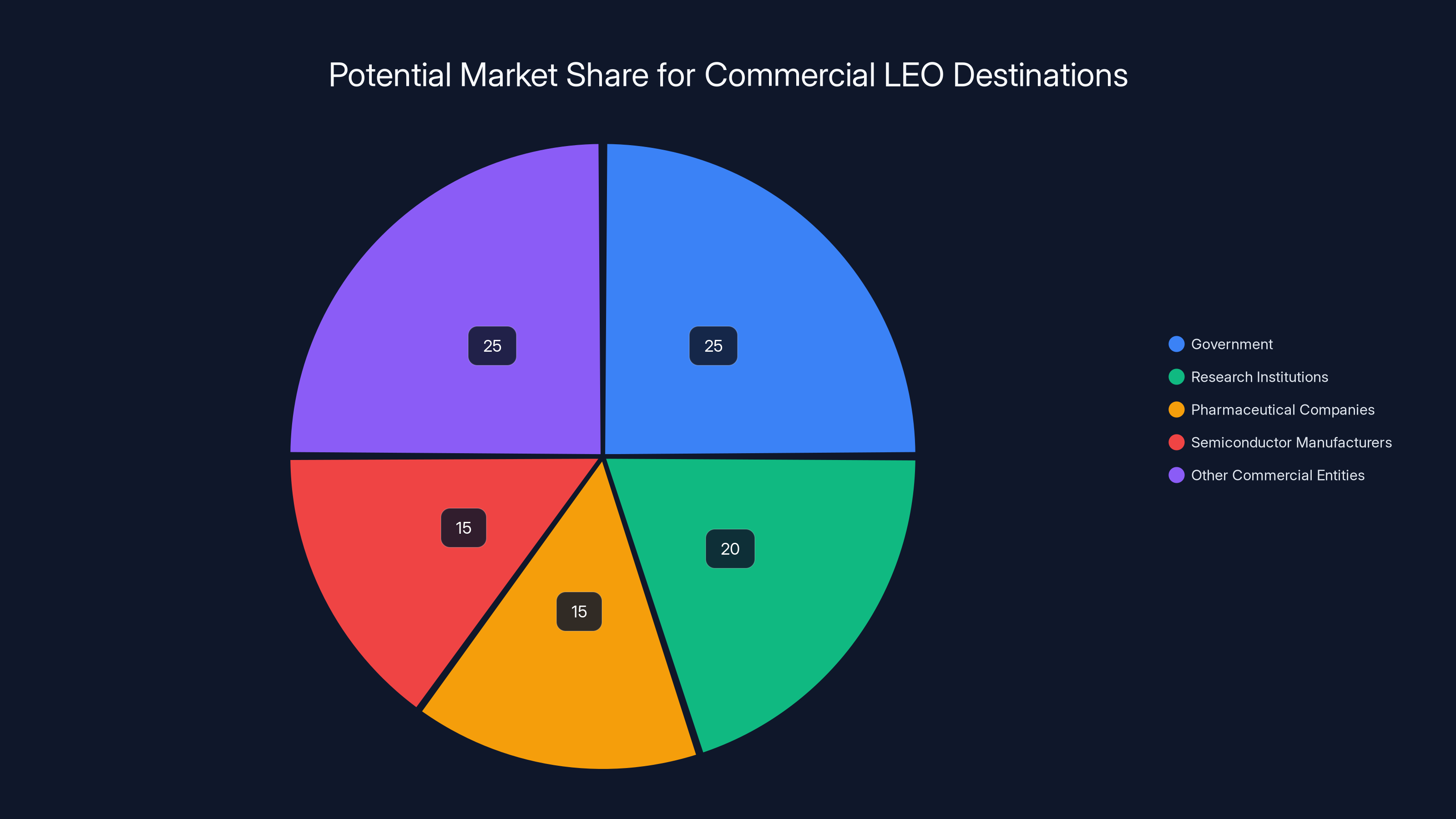

Estimated data shows a diverse market share for Commercial LEO Destinations, with government and other commercial entities leading the demand.

The 2030 Deorbiting Decision: How ISS Got a Retirement Date

Why 2030 specifically? The decision came from a combination of technical, economic, and political factors. On the technical side, 25-year-old station elements are approaching the end of their designed service life. Keeping them operational requires increasingly intense maintenance and becomes increasingly risky. Structural materials degrade, seals fail, and redundant systems start showing failures.

On the economic side, ISS operations cost roughly

On the political side, 2030 was far enough in the future to seem distant when the decision was made in 2021. It gave Congress confidence that there would be time to develop alternatives without rushing. It aligned with broader NASA goals to shift away from government-operated platforms toward private-sector leadership in low Earth orbit.

But here's the problem with that reasoning: 2030 was always going to arrive faster than it seemed in 2021. Now that it's 2025, five years looks short. Companies that were supposed to be on an accelerated schedule are behind schedule. The cascade of delays means Phase 2 contracts won't be signed until 2025 or later, compressing the construction and certification timeline dramatically.

The 2030 date isn't arbitrary, but it's starting to look less like a firm deadline and more like an aggressive target that requires perfect execution from here forward. Any additional delays risk making it infeasible. That's the operational reality that Davis was expressing when she talked about possibly extending ISS operations if commercial alternatives aren't ready.

Continuous Human Presence: Why This Matters More Than You Might Think

The phrase "continuous human presence in low Earth orbit" comes up repeatedly in conversations about ISS retirement and commercial platforms. It sounds like abstract policy language, but it describes something genuinely important: the capability to maintain American astronauts working in orbit on an ongoing basis.

The United States had continuous human presence in space from 1992 onward, first with the Space Shuttle program and Mir, then through the ISS. That's over three decades of continuous capability. The Soviet Union/Russia has maintained it even longer, with ongoing operations aboard Mir and then the Russian segment of ISS.

Losing that continuous presence—having a period of months or years where American astronauts can't access orbit—would be a strategic setback. It would affect scientific research, technology development, and fundamental understanding of what humans can accomplish in space. It would create a perception that American spaceflight capability is declining just as international competition is intensifying.

China, specifically, is actively developing its own space station and plans to maintain continuous human presence through its own programs. If the United States experiences a gap while China maintains continuous operations, the optics and the strategic implications are negative.

Senator Cruz's repeated emphasis on "no gap" in human presence reflects this strategic perspective. It's not just about staying ahead of China, though that's certainly part of it. It's about maintaining a core capability that demonstrates American leadership in space exploration and innovation.

That's why the commercial platform development timeline is critical. The platforms aren't just replacements for an aging facility. They're the mechanism that enables continuous human presence to continue beyond the ISS era.

The Gray Zone Problem: Why Unclear Requirements Hurt Private Companies

Davis used the phrase "added a lot more gray" when discussing the impact of changing requirements on the commercial space station companies. That gray zone—the uncertainty about exactly what NASA will require—creates cascading problems.

Companies need to make design decisions today that will affect them for years. They need to commit to specific structural approaches, specific life support systems, specific docking mechanisms. Every design decision involves tradeoffs: cost versus capability, simplicity versus flexibility, schedule versus reliability.

When requirements are unclear, companies either have to make conservative assumptions (which adds cost) or make optimistic assumptions (which creates risk). Neither is ideal. The solution is clear requirements that let companies optimize for the actual target rather than optimizing for worst-case scenarios or best-case hopes.

The August 2024 directive from Sean Duffy, well-intentioned as it might have been, created exactly this kind of uncertainty. Companies that had already committed to designs optimized for previous requirements suddenly faced the possibility that those designs might not meet new requirements. The question wasn't academic—it could affect hundreds of millions of dollars in development costs and years of timeline.

When Isaacman's team finishes reviewing the requirements and issues final guidance, companies can move forward with confidence. Until then, every day of delay is a day that companies are working with incomplete information, making tentative plans, and hedging their bets.

Estimated data shows that commercial space stations attract the least investor interest due to high uncertainty, while other sectors like launch services and satellite operations are more appealing.

Congressional Oversight: Why Staffers Like Davis Have Real Power

It's worth understanding where Davis gets her influence and why her concerns matter. She works for Senator Ted Cruz, who chairs the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. That committee has jurisdiction over NASA, the Federal Communications Commission, the Department of Transportation, and numerous other agencies.

The chair of that committee has outsized power in space policy specifically. Funding bills come through the committee. Nominations for leadership positions are confirmed through the committee. Oversight hearings happen in the committee. When the committee chair wants something, federal agencies pay attention.

Cruz, as a senator from Texas, also has a parochial interest in Johnson Space Center in Houston, where the International Space Station program is managed. Texas space jobs and Texas space industry matter to him politically. But by all accounts, his push for clear commercial platform requirements and accelerated development isn't just about protecting Houston jobs. It's a genuine policy position based on the conviction that maintaining human presence in space is strategically important.

Davis, as a staff member working for the committee chair on space policy issues, has direct access to NASA leadership. When she requests briefings, she gets them. When she expresses concerns about delayed RFPs, those concerns get back to the administrator. When she says Cruz considers something a priority, NASA interprets that as a directive—not a legal mandate, but certainly a strong signal about what Congress expects.

This dynamic is how American government actually works. Staffers like Davis are often the people who understand the details of complicated technical programs better than the nominal politicians. They develop relationships with program managers, engineers, and contractors. They ask tough questions in briefings. They flag problems that need attention.

Congressional oversight has been a crucial mechanism keeping ISS operations on track and pushing NASA to develop commercial alternatives. It's also an imperfect mechanism—sometimes Congress micromanages when it shouldn't, sometimes it demands timelines that are technically infeasible, sometimes it prioritizes parochial interests over good policy.

But in the case of commercial space stations, Congressional pressure through staffers like Davis seems to be pushing in the right direction: toward faster, clearer, more decisive action.

The Technical Reality: Building a Space Station Takes Time

One more critical context: building a functional space station is genuinely difficult. It's not just engineering challenge—it's an enormous, multi-disciplinary engineering challenge involving structures, life support, power systems, thermal management, communications, robotics, crew systems, and dozens of other technical domains.

Even with NASA's ISS experience and the learning curve that represents, building a new station from scratch is a massive undertaking. The companies involved aren't trying to rush it. They understand that cutting corners on critical systems can kill people.

But they're also aware that they need to accelerate. The 2030 timeline isn't generous. If Phase 2 contracts are signed in late 2025, they realistically have four years to design, build, test, certify, and conduct initial crewed missions. Four years for a completely new spacecraft with new life support systems, new docking systems, new hardware.

Historically, spacecraft development takes longer. Artemis II has been delayed multiple times. Commercial crew vehicles took longer to develop than initially expected. But commercial companies often move faster than traditional aerospace because they're incentivized by deadlines and by market opportunities.

The technical question is whether the aggressive timeline is feasible. The policy question is whether companies will be willing to take the risks that an aggressive timeline implies. That's another reason the RFP matters so much—it clarifies what NASA expects, which helps companies understand whether they should be betting on an aggressive development schedule.

International Perspectives: What Other Nations Are Doing

The commercial space station story isn't just an American narrative. International partners have their own perspectives on ISS retirement and what comes next.

The European Space Agency, Japanese Space Agency, and Canadian Space Agency all contributed significant elements to ISS and rely on it for research. They have stakes in whatever comes next. Some international partners are exploring their own mini-platform concepts. Others are looking at partnerships with American companies to access future commercial platforms.

Russia's segment of ISS has been a particular complication given geopolitical tensions. Russian cooperation on ISS has continued despite broader conflicts, but that cooperation is now being reconsidered. If Russia pursues fully independent orbital platforms, it further fragments the global spaceflight environment.

China's independent space station development represents another competitive element. As China develops its own platforms and capabilities, the competitive pressure on American development increases. Not in a zero-sum sense—there's plenty of room for multiple space stations serving different purposes—but in a strategic sense.

The broader context is that low Earth orbit is becoming a contested domain in which multiple nations and companies are building infrastructure. American leadership in that domain isn't automatic or inevitable. It requires maintaining continuous presence, attracting talented people, and making smart investment decisions.

Delays in the RFP release can significantly compress the timeline for NASA's project phases, making it challenging to complete necessary tasks before the ISS deorbit in 2030. Estimated data.

The Private Investment Angle: Why Markets Matter

One of the core ideas behind the Commercial LEO Destinations program is that private investment, combined with government purchasing, can create a sustainable space station market. NASA would be one customer among many. Research institutions, pharmaceutical companies, semiconductor manufacturers, and other entities would also purchase access to microgravity environments.

This model has worked in other areas of spaceflight. SpaceX developed Falcon 9 with a combination of government funding (initially) and private investment, then transformed it into a highly profitable business by servicing a broad market. Commercial crew vehicles work the same way. Government was one early customer, but the capability now serves other customers too.

Applying that model to space stations makes sense. A single government customer can't support the $3-4 billion annual operating cost of ISS. But distributed across multiple customers in the commercial, research, and government sectors, that cost becomes sustainable.

The problem, again, is the chicken-and-egg problem that commercial markets have. Private investors need to see existing demand to commit capital. But demand won't materialize until platforms are available to deliver services. Breaking that cycle requires either government commitment to a customer base (which is what NASA is trying to do) or a visionary entrepreneur willing to bet massive sums on eventual demand (which is what Elon Musk did with SpaceX).

NASA's approach—providing development funding and committing to purchase services from commercial platforms—is designed to bridge that gap. But it only works if the program moves forward with sufficient momentum. Delays and unclear requirements undermine the whole model because they reduce investor confidence.

Timeline to Watch: Critical Milestones in the Next Five Years

If everything accelerates as it should, here's what the timeline might look like:

Early 2025: NASA's new leadership finalizes CLD requirements and issues the RFP.

Spring-Summer 2025: Companies submit detailed proposals in response to RFP. NASA evaluates them against established criteria.

Fall 2025: NASA announces Phase 2 winners. Contracts are negotiated and signed with one or two lead companies.

2025-2027: Detailed design and initial construction phases. Companies finalize designs, procure long-lead items, begin manufacturing key components.

2027-2029: Final assembly, integration, and testing. Hardware is built, systems are tested, certification processes begin.

2029: Unmanned orbital deployment of first commercial platform for checkout and verification.

2030: Crewed missions to verify platform operations. Concurrent ISS deorbiting logistics begin.

2030-2031: Transition of continuing human spaceflight operations to commercial platforms. ISS is deorbited.

That timeline is aggressive but plausible. Every delay compresses subsequent phases. By late 2025, if RFPs still haven't been released, several of these milestones start shifting right. By mid-2026, if Phase 2 contracts still aren't signed, you're looking at a genuine scheduling crisis.

That's the operational context Davis was expressing. It's not fear-mongering or political theater. It's realistic assessment of how long things take and how little margin for error remains.

What Success Looks Like: The End State

If the commercial space station program succeeds, what does that look like?

By 2032, successful completion looks like multiple commercial platforms in operation, each serving different purposes and customer bases. One might focus on pharmaceutical research and material science. Another might specialize in Earth observation or technology testing. A third might be optimized for educational and corporate partnerships.

American astronauts would be working aboard these platforms on a continuous basis, just as they do on ISS. International partners would have access through partnerships, just as they do now. Government funding would continue, but distributed across multiple platforms rather than concentrated on a single facility.

Private companies would be operating these platforms at lower cost than ISS because they're purpose-built for their specific missions rather than optimized for general-purpose use. Competition between platforms would drive innovation and efficiency improvements.

Scientific research in microgravity would continue uninterrupted. The transition would be transparent to researchers—they'd move from ISS to commercial platforms with minimal disruption.

That's the vision. Achieving it requires decisions and actions now. That's why staffers like Davis are pushing so hard for progress on the RFP and why newly confirmed administrators like Isaacman need to move decisively.

The Bigger Picture: Low Earth Orbit's Strategic Importance

Step back from the immediate ISS transition and you see a broader trend: low Earth orbit is becoming crowded. Satellite megaconstellations are launching thousands of spacecraft. Countries and companies are building space stations. Military and intelligence operations are expanding in orbit. Orbital servicing and manufacturing are emerging as real business lines.

What happens in LEO over the next decade will shape spaceflight capability for generations. Nations and companies that establish strong positions now—through platforms, through supply chains, through partnerships—will have advantages later.

America's position in LEO has been strong because of ISS. ISS demonstrated decades of sustained human presence, continuous research capability, and technological leadership. But that advantage is fleeting if continuous presence is lost during a transition period. American commercial platforms need to establish themselves quickly, prove their capability, and demonstrate that American industry can sustain human presence without ISS.

That's not paranoia. That's strategic thinking about how capabilities and influence compound over time. Countries that maintain continuous presence and operational infrastructure have more ability to pursue goals in orbit. Countries that lose that presence face a period of rebuilding and catching up.

Cruz's insistence on "no gap" in human presence isn't just about avoiding domestic political embarrassment. It's about maintaining the strategic position that America has held in space since the 1970s.

The CLD Program's Broader Significance: Privatization of Space Stations

The Commercial LEO Destinations program represents a fundamental shift in how space infrastructure is developed and operated. Instead of government agencies designing and building facilities, commercial companies take the lead. Government is a customer and early funder, but not the operator.

This shift happened gradually in spaceflight. Launch vehicles were the first domain—companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and others now dominate launch services. Crew and cargo transportation came next—companies have captured most ISS resupply missions and crew operations.

Space stations are the next frontier in that privatization. If the CLD program succeeds, it will demonstrate that the private sector can design, build, and operate complex orbital infrastructure. If it fails or is delayed indefinitely, it will suggest that space stations are too complex or require too much government involvement for privatization to work.

The success of CLD will ripple through the entire commercial space industry. It will demonstrate that markets for orbital operations can be created and sustained. It will encourage investment in supporting services like orbital refueling, orbital servicing, orbital construction, and orbital logistics.

This isn't just about replacing ISS. It's about establishing the template for how human spaceflight infrastructure develops in the 2030s and beyond. That's why the timeline matters so much. If commercial platforms can be demonstrated to work in time to provide continuous human presence, it validates the model. If there's a gap, it raises questions about whether the model is viable.

Regulatory and Certification Challenges Ahead

One dimension that Davis's remarks touched on indirectly: certifying commercial platforms for human habitation is extraordinarily complex. These stations will be American spacecraft, potentially operated in international orbit, accessed by crews from multiple nations. Safety certification, operational certification, environmental compliance—all of these require extensive regulatory oversight.

NASA has to establish certification standards that are rigorous enough to ensure astronaut safety but flexible enough to let companies innovate and optimize costs. Getting that balance right is genuinely difficult. The previous directive from Sean Duffy apparently tried to get that balance and raised questions about whether the balance was right.

Isaacman's team has to resolve those questions and publish clear standards that companies can design to. That's not just a bureaucratic exercise. The standards effectively define what's possible and what's not. Overly restrictive standards could make commercial platforms infeasible. Insufficiently restrictive standards could create safety risks.

Given that this is a complex regulatory problem with genuine technical substance, the delays actually somewhat make sense. You don't want to publish requirements hastily, realize they're wrong halfway through Phase 2, and have to revise them again. But you also can't delay indefinitely. At some point, the requirements have to be published and companies have to move forward.

The window for getting that balance right is narrow. The next few months are genuinely critical for Isaacman's team to finalize requirements and get them published.

What Happens If Timelines Slip Further: Contingency Planning

Davis hinted that if commercial platforms truly aren't ready, ISS extension beyond 2030 is "not off the table." What would that actually entail?

First, it would require Congressional approval and funding. Extending ISS operations costs additional billions. Those funds have to come from somewhere—either new NASA budget or redirected from other programs. The fiscal implications would be significant.

Second, it would require technical assessment of whether ISS systems can be kept operational beyond 2030. Aging components would need replacement. Structural assessments would be necessary. Contingency systems might need upgrades. The cost per year would probably increase as systems age.

Third, it would require international coordination. International partners would need to agree to extended operations. Russia's participation would be particularly complex given current geopolitical tensions.

An ISS extension to 2035 or 2040 would give commercial platforms more time to develop, mature, and prove themselves. It would reduce the schedule pressure that creates risk. But it would also increase costs significantly and reinforce government-operated spaceflight rather than accelerating transition to commercial operations.

The scenario nobody wants but might need to contemplate: ISS operations continue at reduced capacity past 2030 while commercial platforms come online, then ISS is gradually retired as commercial capability increases. That staged transition approach would reduce risk but increase costs.

The Bottom Line: Why This Moment Matters

There's a particular moment that matters in every complex development program. It's the moment when you move from planning to execution, from concepts to concrete deliverables, from promising to doing.

The CLD program is at that moment right now. The seed funding phase is complete. Companies have concepts and preliminary designs. The next phase requires actual construction and certification. To start that phase, NASA needs to publish requirements and issue the RFP.

Davis's comments are significant because they represent Congressional pressure at the exact moment when that pressure matters most. She's not asking NASA to do something impossible. She's asking NASA to publish a document that defines what needs to happen next.

Isaacman's early performance is significant because new leadership has an opportunity to reset the trajectory and move decisively. The first decisions a new administrator makes establish patterns that persist. If Isaacman prioritizes CLD and moves quickly on the RFP, it signals that this program matters and it will be resourced appropriately.

The five-year window until 2030 is not generous. But it's sufficient if everything moves forward with appropriate urgency and clarity. It's insufficient if delays continue and requirements remain unclear.

That's the operational reality. That's why staffers are "begging" for action, not because of political drama, but because the technical timeline genuinely requires it.

Looking Forward: Sustainable Human Presence Beyond ISS

The International Space Station will eventually be gone. Its modules will be deorbited and burned up on reentry. The facility that has been continuously occupied since November 2000 will become history.

What matters now is what comes next. The vision is that commercial platforms, multiple platforms operated by different companies for different purposes, will provide continuous human presence in orbit. That vision is achievable, but it requires decisions and actions happening right now.

The weeks and months ahead will be critical. The RFP will either get published or it won't. Requirements will either be clarified or they'll remain uncertain. Companies will either have clear direction or they'll continue operating in ambiguity.

Davis's comments serve as a public accountability mechanism. She's signaling, on behalf of the Senate Commerce Committee and Senator Cruz, that Congress is watching. Congress will be asking questions if timelines slip further. Congress will be evaluating whether the program is moving with appropriate urgency.

For the space industry, for the researchers who depend on microgravity research facilities, and for America's strategic position in space, the next decision matters. The RFP matters. Getting clear requirements out matters. Authorizing Phase 2 contracts matters.

Those aren't glamorous topics that capture public attention like Moon landings or Mars missions do. But they're the foundation that makes everything else possible. They're the unglamorous infrastructure decisions that either enable or prevent the future of human spaceflight.

The countdown clock is real. The deadline is real. The work needs to happen now.

FAQ

What is the Commercial LEO Destinations program?

The Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) program is NASA's initiative to transition human spaceflight operations in low Earth orbit from government-operated platforms like the International Space Station to privately-owned and operated commercial space stations. NASA provides development funding and commits to purchasing services from these platforms, creating a market that encourages private investment and long-term sustainability.

Why is NASA retiring the International Space Station?

The International Space Station was originally designed for 15-year operation but has been extended multiple times since its launch in 1998. Major station elements are now over 25 years old, approaching the end of their designed service life. Operating aging hardware becomes increasingly expensive and risky. The 2030 retirement date gives NASA time to transition to commercial alternatives before ISS systems reach critical failure points, though this timeline is becoming increasingly challenging as development delays accumulate.

What are the main technical approaches being used for commercial space stations?

Companies are pursuing different architectural approaches optimized for various missions and cost structures. Some are designing modular platforms using ISS-style architecture with multiple docking ports and expandable capacity. Others are developing single-module platforms optimized for specific research applications. Some companies are exploring inflatable structures to reduce launch costs and complexity. Each approach involves different tradeoffs between capability, cost, development timeline, and operational flexibility.

How much will commercial space stations cost to operate?

Operating costs for commercial platforms are expected to be lower than ISS's current $3-4 billion annually, though exact costs depend on each platform's design and operational model. Commercial platforms will be purpose-built for specific applications rather than general-purpose, potentially reducing overhead. However, distributing operating costs across multiple customer types and companies rather than a single government operator introduces different economic dynamics that are still being tested.

What is the realistic timeline for commercial platforms to achieve human operations?

If the RFP is released in early 2025, Phase 2 contracts are signed in late 2025, and development proceeds without further delays, initial crewed missions could potentially occur in 2029-2030. However, this timeline assumes perfect execution and no unexpected technical challenges. More realistic projections account for typical delays and build contingency into the schedule, suggesting crewed operations might not commence until 2031-2032. The current five-year window between Phase 2 contract signing and the 2030 ISS retirement is extremely tight.

What happens if commercial platforms aren't ready by 2030?

If commercial platforms aren't operational in time to maintain continuous human presence in orbit, Congress has indicated willingness to extend ISS operations beyond 2030. An extension would require additional funding, technical assessments of aging systems, and international coordination with partner agencies. While an extension would reduce schedule pressure and technical risk, it would significantly increase program costs and delay the transition to fully commercial orbital operations. The alternative—accepting a gap in continuous human presence—is considered unacceptable from both technological and strategic perspectives.

Why is Congress pressuring NASA to accelerate the commercial space station timeline?

Congressional pressure reflects several concerns: maintaining American continuous human presence in low Earth orbit (which the United States hasn't been without since 1992), staying competitive with international programs like China's space station, and supporting the development of commercial space industry infrastructure. Senator Ted Cruz and his staff also have direct interest in spaceflight policy through NASA's Johnson Space Center in Texas. The pressure is substantive, based on realistic assessment of program requirements and timelines, rather than purely political.

How does private investment fit into the commercial space station model?

NASA's approach combines government development funding and procurement commitments with private investment to create sustainable platforms. NASA funds initial concept development and provides purchasing guarantees that give private companies confidence to attract venture capital and institutional investors. This model worked successfully for commercial cargo and crew vehicles, but space stations represent a larger capital investment and require broader customer bases beyond just NASA. Success depends on creating viable markets where research institutions, manufacturers, and other entities purchase access to microgravity environments.

What role do international partners play in commercial space station development?

International partners including the European Space Agency, Japan, Canada, and Russia have stakes in ISS and the transition to commercial platforms. Some partners are exploring independent platform development or partnerships with American commercial companies. The environment is becoming more competitive, with multiple nations pursuing independent orbital capabilities. This competition creates urgency for the United States to maintain leadership in orbital infrastructure development and human presence sustainability.

Key Takeaways

- Senate staffers are pressuring NASA to release the critical Request for Proposals that kicks off Phase 2 commercial space station competition

- The 2030 ISS retirement deadline creates a five-year window for commercial platforms to achieve operational status, which is aggressive but technically feasible

- Leadership instability at NASA and unclear requirements from recent directives have damaged private company investor confidence and slowed development progress

- Maintaining continuous human presence in low Earth orbit is a strategic priority that requires commercial platforms to launch before the ISS is deorbited

- New NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman's early performance suggests potential for accelerated decision-making and clearer policy direction on the CLD program

Related Articles

- SpaceX's 15,000 Starlink Gen2 Satellites: What It Means [2025]

- Trump's 25% Advanced Chip Tariff: Impact on Tech Giants and AI [2025]

- UK Digital ID No Longer Mandatory: What Changed [2025]

- Senate Passes DEFIANCE Act: Deepfake Victims Can Now Sue [2025]

- SpaceX's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What It Means [2025]

- Nvidia's Upfront Payment Policy for H200 Chips in China [2025]

![NASA's Commercial Space Station Crisis: Senate Demands Timeline [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-s-commercial-space-station-crisis-senate-demands-timeli/image-1-1768491513783.jpg)