Section 230 at 30: The Law Reshaping Internet Freedom [2025]

Thirty years doesn't sound like much in human terms. A career, maybe. A mortgage. But in internet time? Thirty years is an eternity.

On February 8, 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act into law, tucking inside it a single provision that would reshape everything: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Twenty-six words. That's it. No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider. Those words became the legal foundation for virtually every platform you use today. YouTube, TikTok, Reddit, X, Instagram, Discord, Airbnb, Wikipedia. All of them exist in their current form because of those twenty-six words.

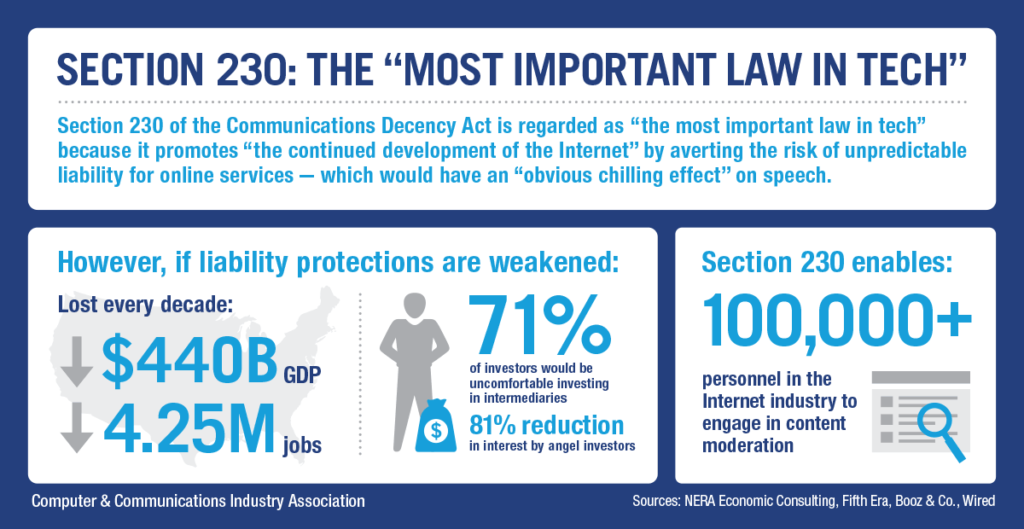

Here's what's wild about it. Nobody could've predicted what would happen. Section 230 was written when the internet was still mostly dialup connections, when the biggest websites were GeoCities and AltaVista. The law's creators were trying to solve a very specific problem: companies were getting sued for the terrible things users posted on their platforms. Early internet service providers faced crushing liability for hosting user content they had no control over. Section 230 was supposed to fix that. Let platforms exist without constant legal jeopardy.

It worked. Maybe too well.

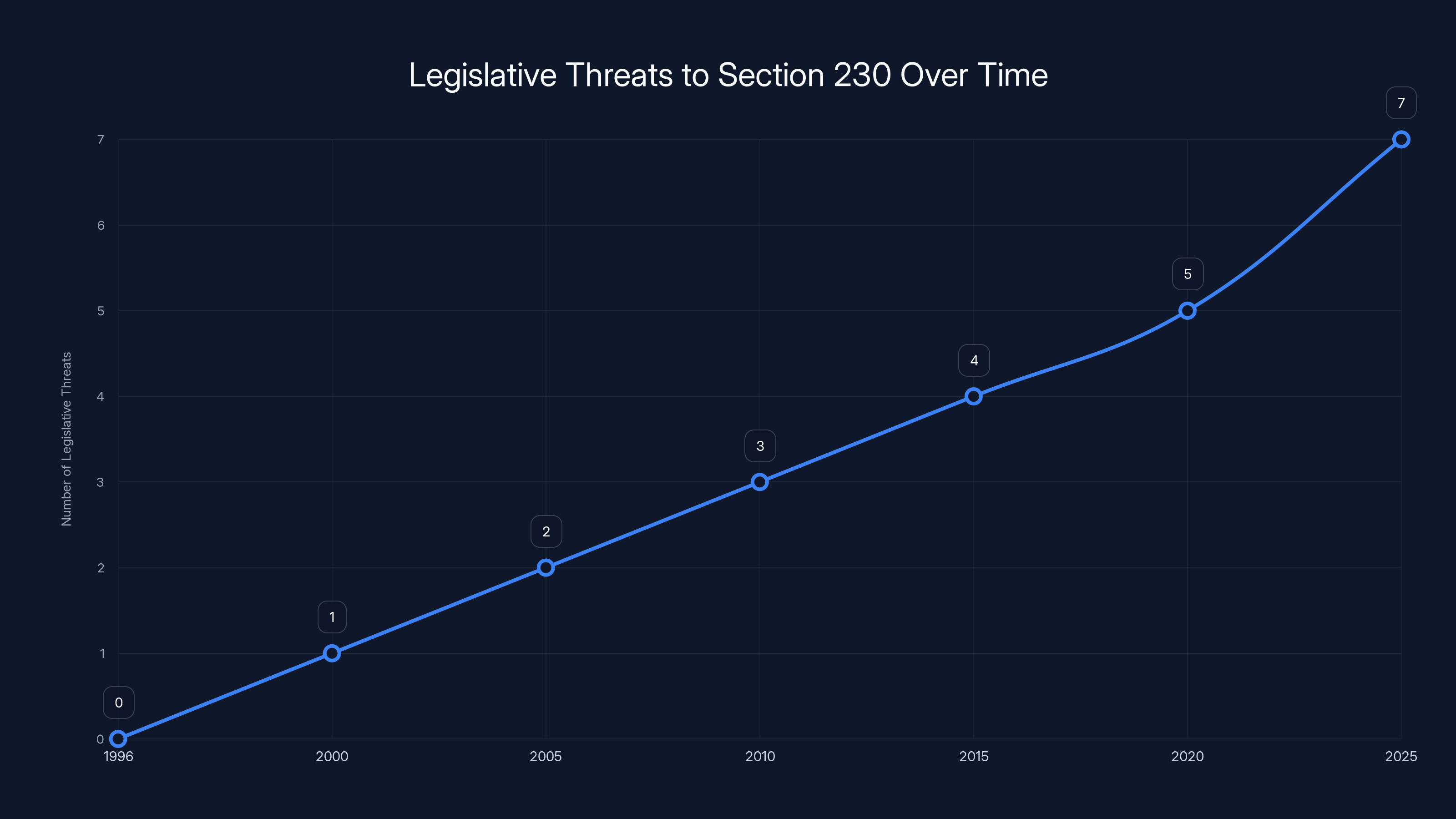

Now, thirty years later, Section 230 is under siege like never before. We're not talking about the usual complaints anymore. We're talking about serious legislative efforts to repeal it entirely. Lawsuits stacking up in courts across the country. Supreme Court justices hinting they might finally overturn precedent. Parents grieving dead children. Kids suffering addiction. The whole debate has shifted from "should Section 230 exist" to "how much longer can we tolerate it existing."

This is the moment where the law faces its biggest test yet.

TL; DR

- Section 230 has protected platforms for 30 years by shielding them from liability for user-generated content, enabling the modern internet as we know it.

- Legislative threats are real: Bills to repeal or sunset Section 230 have bipartisan support, with deadlines ranging from 2 to 5 years.

- Courts are narrowing the scope: Recent lawsuits are challenging Section 230's protections in addiction cases, algorithmic recommendation cases, and sexual abuse cases.

- The stakes are enormous: Repealing Section 230 could either revolutionize platform accountability or destroy the internet ecosystem entirely.

- A compromise middle ground is emerging: Some proposals want to preserve Section 230 while adding guardrails for algorithmic amplification and content moderation transparency.

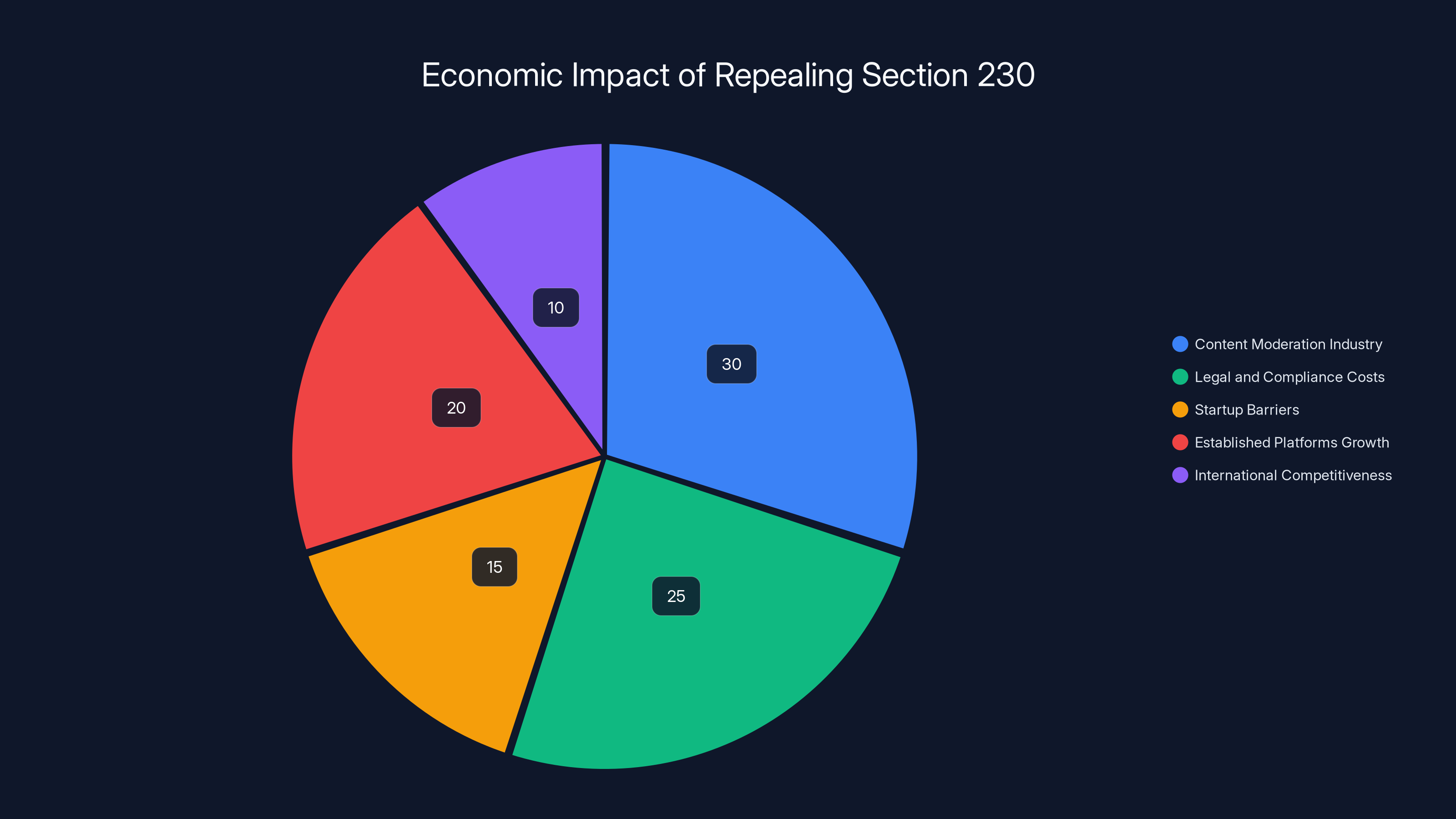

Repealing Section 230 would significantly boost the content moderation industry and legal costs, while increasing barriers for startups and benefiting established platforms. Estimated data.

What Section 230 Actually Does

Let's be precise about this, because the mythology around Section 230 has gotten completely divorced from reality.

Section 230 doesn't say platforms can do whatever they want. It doesn't shield them from copyright claims. It doesn't protect them from criminal liability. It doesn't let them ignore subpoenas or hide criminal activity. What it actually does is deceptively simple: it treats platforms as hosts, not publishers.

Pre-1996, there was a legal principle called publisher liability. If you published something defamatory, you were responsible for it, whether you wrote it or someone else did. Major newspapers had armies of lawyers checking everything. But the internet was growing. People were posting things on bulletin boards, forums, early websites. Should Prodigy be liable if a user wrote something defamatory in their message board? The courts in the late 1980s said yes, and that answer terrified every internet company trying to exist.

Then came the "Good Samaritan" provision of Section 230. It said that if a platform moderates content in good faith—removing hate speech, blocking harassment, deleting illegal content—they can't be sued for that moderation. They're not liable for being too aggressive in removing content, and they're not liable for hosting user speech. It's a liability shield specifically designed to encourage moderation.

The genius of this was recognizing that you can't have both unlimited user freedom and unlimited publisher control. You have to pick one. If platforms are publishers, they have to control everything, and that means most user speech goes away. If platforms are hosts, they have legal protection to make decisions about what they host.

But here's where it gets complicated. The law doesn't say Section 230 protects platforms from everything. Specific exemptions exist. Copyright claims go straight through. Claims involving sex trafficking—that got carved out in 2018 with FOSTA. Federal criminal law isn't affected. Trade secret theft isn't covered. The law is narrower than the mythology suggests.

Yet courts have interpreted it very broadly. When a parent sued TikTok for their child's suicide, arguing that TikTok's algorithm recommended harmful content, the courts have consistently said that falls under Section 230. When survivors of sexual abuse sued Backpage for hosting classified ads used to facilitate trafficking, the courts said Section 230 protected the platform (though Congress later changed that specific exemption). Section 230 became not just a shield but an impenetrable wall.

This is where the real disagreement starts. Is Section 230 actually too broad, or are courts interpreting it too broadly? That distinction matters enormously for what comes next.

The frequency of legislative threats to Section 230 has increased over time, with a notable rise projected by 2025. Estimated data.

How We Got Here: Three Decades of Pressure

Section 230 was born from genuine need and has died a thousand deaths that never quite took.

The 1990s were when the first challenges emerged. In 1997, a woman sued AOL for hosting a fake ad in a gay chat room that included her name. In 1998, a man sued Prodigy for libel over messages posted on their system. These early cases made it clear that without Section 230, platforms would face constant litigation just for existing. The law protected them, and the internet economy exploded.

But by the mid-2000s, the complaints started. MySpace was accused of not doing enough to prevent predators. YouTube was hosting copyright-infringing content. Twitter was spreading misinformation. Politicians started noticing that Section 230 seemed to be the villain in every tech story. By 2016, the complaints became a roar. Trump took office promising to "go after" social media. In 2019, Trump directly called for Section 230's repeal.

The turning point came in 2018 with FOSTA, the first major exception carved into Section 230. Congress said that sex trafficking claims wouldn't be protected. This wasn't repeal, but it signaled something important: Section 230 could be modified. If Congress could remove the sex trafficking exemption, what else could they remove?

Then came 2020 and the Twitter controversy over the Hunter Biden laptop story. Twitter and Facebook limited the spread of a New York Post article about Hunter Biden's laptop. Republicans were furious. Democrats worried about election interference. Suddenly, both sides of the political aisle had a reason to hate Section 230. Republicans thought it enabled censorship. Democrats thought it enabled misinformation and election interference. Section 230 became one of the few things that truly united a fractured Congress—in opposition to it.

By 2024, the legislative threats became concrete. Bills appeared regularly. The Kids Online Safety Act proposed a framework that would effectively neuter Section 230 for platforms that failed to moderate enough content. The EARN IT Act proposed that platforms would lose Section 230 protection unless they adhered to best practices for encryption and child safety. These weren't theoretical threats. They had real support from real lawmakers.

Then came 2025, and everything accelerated.

The Legislative Assault: Multiple Bills, Multiple Timelines

Right now, there are at least seven different legislative proposals targeting Section 230 in various ways. Let's walk through the most serious ones.

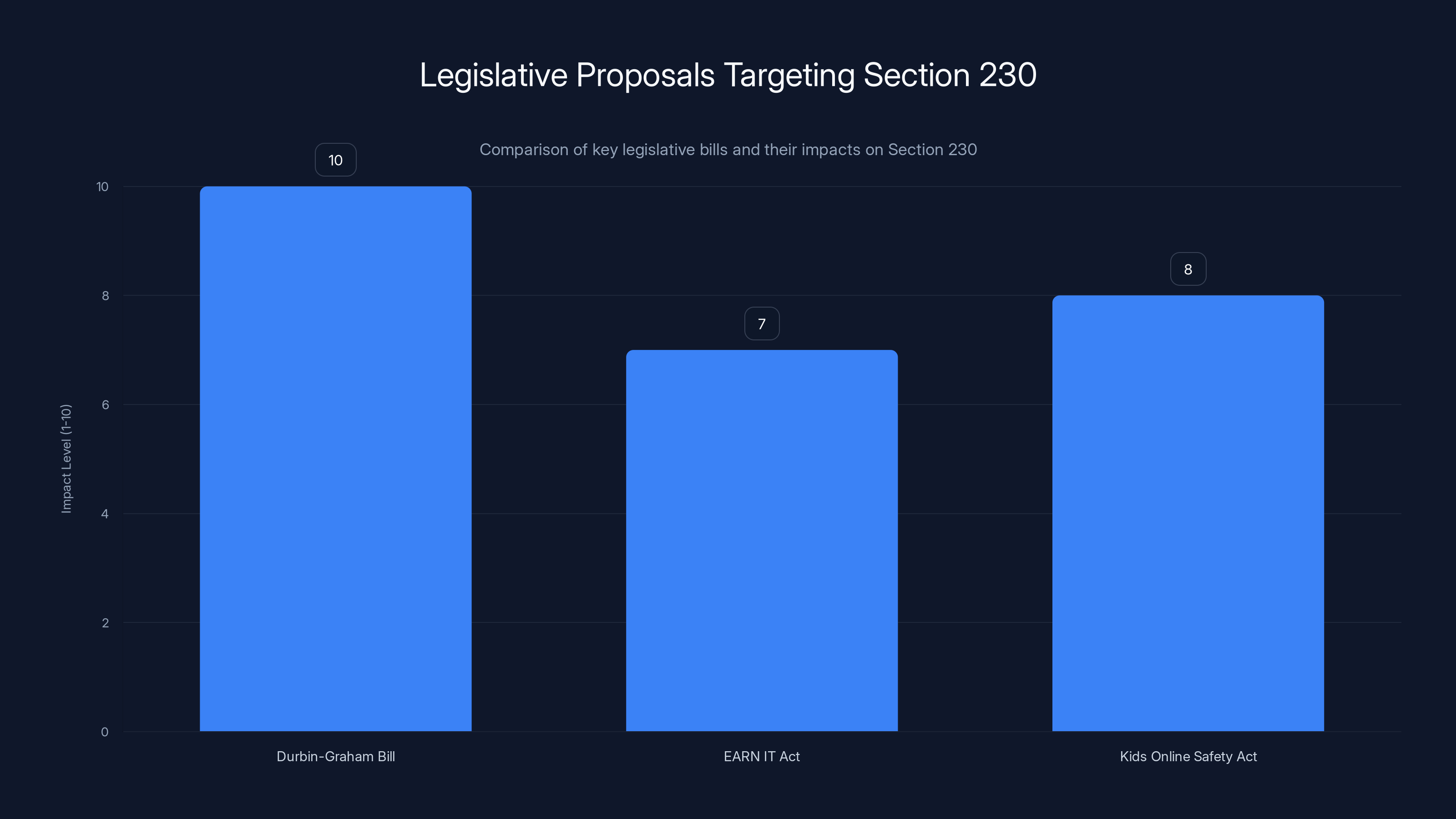

First, the Durbin-Graham bill. Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) introduced a bill to sunset Section 230 entirely in two years. Not modify it. Not carve out exceptions. Repeal it completely, giving Congress and tech companies two years to figure out what comes next. This isn't a fringe bill. Both senators were genuinely serious. They held a press conference with parents who lost children to fentanyl poisoning and sextortion, arguing that Section 230 enabled the harms that killed their kids.

The political calculation here is interesting. Durbin is a Democrat, Graham is a Republican. Neither party owns Section 230 criticism anymore. That makes it almost unstoppable in Congress. Democrats blame Section 230 for not preventing misinformation and algorithm-driven addiction. Republicans blame it for enabling what they see as censorship. There's literally no constituency in Congress defending Section 230 anymore, which means it's vulnerable.

The EARN IT Act, sponsored by Senators Richard Blumenthal and Lindsey Graham, takes a different approach. It doesn't repeal Section 230 outright. Instead, it says platforms lose Section 230 protection unless they follow government-mandated best practices for child safety. Sounds reasonable, right? The catch is that one of those best practices is encryption backdoors—a capability law enforcement wants for investigating crimes, but which security experts say is fundamentally impossible to implement safely. If a platform refuses to build encryption backdoors (and all of them do), it automatically loses Section 230 protection.

Then there's the Kids Online Safety Act. This one proposes that Section 230 protection disappears for platforms unless they can prove they're adequately protecting minors. The burden of proof shifts to the platform. They have to affirmatively demonstrate safety, or they lose liability protection. Combined with the difficulty of actually defining what "adequate protection" means, this effectively creates unlimited liability for any platform serving kids.

Each of these bills has different mechanics, different carve-outs, different enforcement approaches. But they all point the same direction: Section 230 is going away, either entirely or functionally.

The timeline matters. The Durbin-Graham bill gives platforms two years. The others don't specify. But politicians are serious about moving quickly. We're probably looking at legislative action within the next 18 to 24 months, not five years down the road. This isn't someday. This is now.

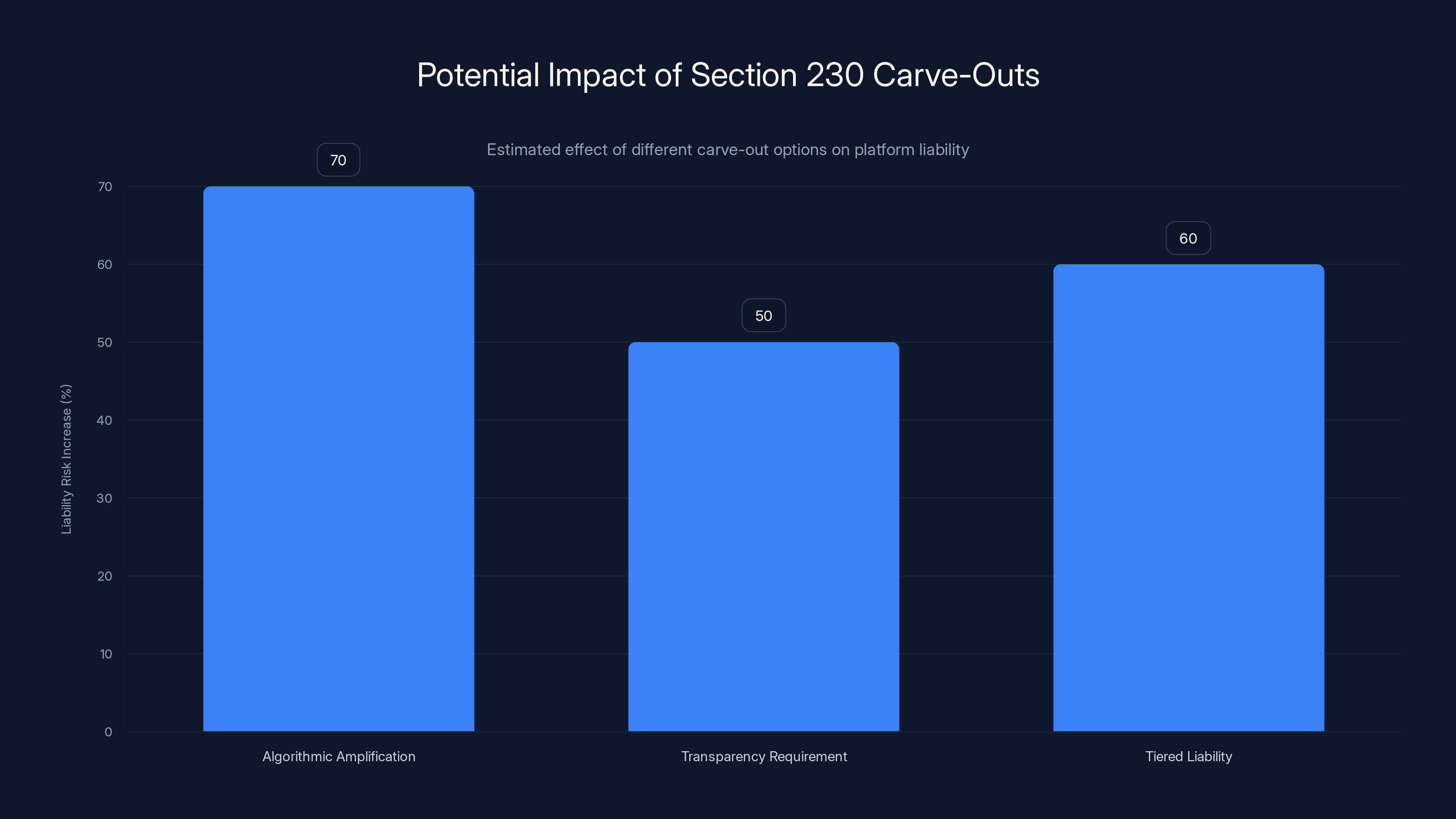

Estimated data suggests that algorithmic amplification carve-outs could increase platform liability risk by 70%, while transparency requirements and tiered liability could increase it by 50% and 60% respectively.

The Court Cases: Narrowing From Within

While Congress debates, courts are already narrowing Section 230 through litigation. This might matter more than legislation.

Look at the addiction cases. Parents are suing TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, and YouTube arguing that their algorithms are deliberately designed to addict children, causing psychological harm. The platforms argue Section 230 protects them because they're not liable for the content users create; they're just hosting it. But the parents' lawyers are making a clever argument: Section 230 protects you from being treated as a publisher of user content, but it doesn't protect you from being an algorithm designer. The algorithm that decides what content gets recommended? That's not user-generated. That's the platform's own creation. Therefore, Section 230 shouldn't protect it.

Some courts are beginning to agree with this distinction. It's not a full rejection of Section 230, but it's a narrowing. If recommendations are treated separately from hosting, platforms could face liability for algorithmic choices without losing Section 230 protection for the content itself.

Then there's the algorithmic amplification question. Does Section 230 protect a platform when it uses an algorithm to amplify specific content? If TikTok's algorithm specifically recommends videos designed to exploit children, is that the platform publishing those videos in a new way? The lawsuits keep piling up, and courts keep hinting that the answer might be no.

The sex trafficking cases have already resulted in partial carve-outs. FOSTA created an exception to Section 230 for claims involving sex trafficking. Now, courts are interpreting FOSTA broadly. If something even tangentially involves sex trafficking, Section 230 might not apply. This has caused some hosting companies to simply refuse to serve certain industries entirely, because the liability risk became too high.

Most dramatically, the Supreme Court has been signaling interest. In recent decisions, justices have questioned whether Section 230 goes too far. Justice Clarence Thomas, in particular, has written opinions suggesting that maybe platforms shouldn't be treated as hosts at all—that they're making editorial choices when they moderate content, and therefore they should be treated as publishers. If the Supreme Court overturns decades of Section 230 precedent, the entire liability landscape changes overnight.

The Real Harms: Why People Want Section 230 Dead

To understand why Section 230 has become so reviled, you have to understand the harm narratives.

Parents show up to congressional hearings with photos of dead children. Kids who were trafficked through Backpage, which existed because Section 230 protected it. Kids who died from fentanyl poisoning after buying pills on platforms with encrypted payment systems. Kids who took their own lives after being cyberbullied relentlessly on social media, where the platforms claimed they couldn't be held liable because their algorithm wasn't the problem—the users were.

The emotional argument is overwhelming. A parent who lost a child to overdose or suicide doesn't care about the constitutional implications of platform liability. They care that the platform that facilitated their child's death escaped accountability through legal technicality. Section 230 looks like a law that values platform profits over human life.

Then there's the addiction argument. Internal company documents from Facebook (now Meta) showed that executives knew their algorithms were making teenage girls more depressed and anxious. They knew. And they did nothing, partly because Section 230 meant they had no legal incentive to do anything. Under Section 230, Meta isn't liable for the psychological damage caused by infinite scroll and algorithmic addiction. If Section 230 went away, that changes.

The misinformation argument is subtler but equally powerful. During COVID, Facebook hosted vaccine misinformation that spread widely. During elections, Twitter and Facebook failed to remove obvious disinformation. During January 6th, platforms hosted insurrection planning. The argument goes: without Section 230 holding them harmless, maybe platforms would take misinformation more seriously. Maybe they'd employ more moderation. Maybe they'd care about truth.

The sex trafficking argument is hardest to counter. Backpage was explicitly used to traffic sex workers. Testimonies from survivors describe being kidnapped, exploited, and sold through classified ads that Backpage knew were trafficking-related. Backpage claimed Section 230 protection. It took an act of Congress to carve out that exemption. But the damage was already done. Thousands of people trafficked. Hundreds of millions of dollars in damages never paid because the company shut down. Section 230 enabled the harm, at least in the public's mind.

All of these narratives are emotionally resonant. All of them contain truth. And none of them are the complete picture. That's the problem with the Section 230 debate. Both sides are right about something, and both sides are missing something important.

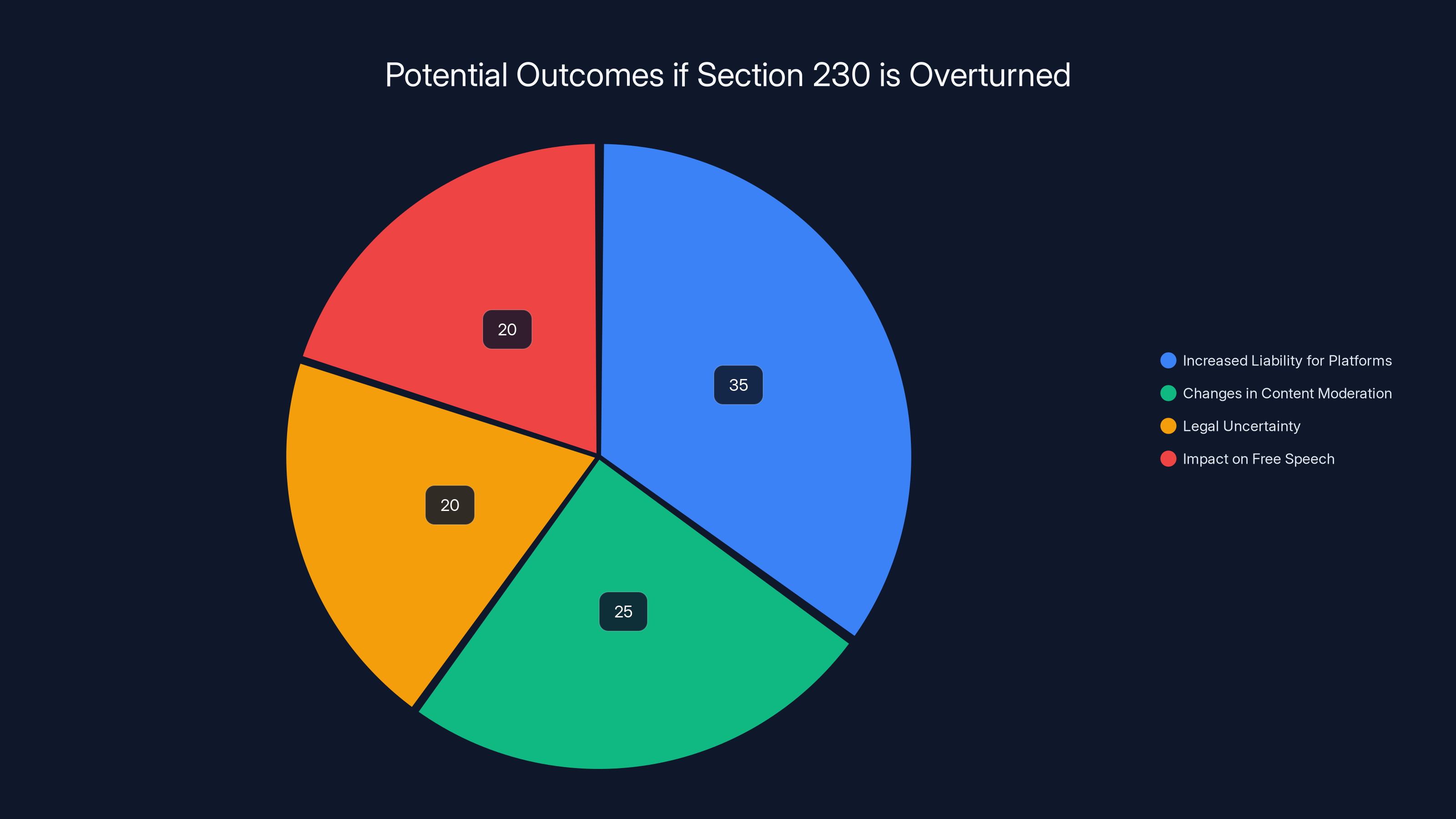

If Section 230 is overturned, platforms could face increased liability (35%), significant changes in content moderation practices (25%), legal uncertainty (20%), and potential impacts on free speech (20%). Estimated data.

The Counterargument: What We'd Lose If Section 230 Dies

But here's where the other side gets a hearing. If Section 230 disappears, what actually happens?

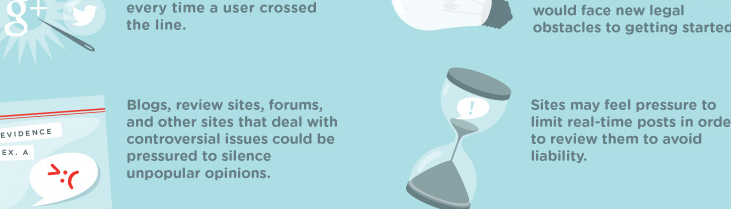

The most likely outcome is the dumbest internet ever created. Moderation becomes binary. Either a platform doesn't host user content at all (become a curated publisher like a newspaper), or they become an unmoderated hellhole like 4chan. The middle ground—platforms that allow broad user speech while removing the worst stuff—becomes legally untenable.

Consider what happens to YouTube. YouTube hosts 720,000 hours of video uploaded daily. YouTube can't possibly hire enough moderators to review all of it. With Section 230, YouTube has legal protection to keep bad content off the platform. Without it, YouTube faces liability for everything it hosts. The math no longer works. YouTube either becomes like Netflix, where only Netflix-approved content appears, or it becomes an unmoderated landfill.

The same logic applies to every platform. Reddit becomes either a handful of celebrity AMAs and nothing else, or pure chaos. Discord becomes either a dead platform or a place where illegal activity runs unchecked. Wikipedia becomes either locked down completely or filled with vandalism. The middle ground dies.

Smaller platforms and communities get crushed worse. A tiny forum for people with a rare disease can't afford the legal risk of hosting any user content. A community platform for artists can't survive if it's liable for every image uploaded. The ecosystem fragments. We lose the connective tissue that made the internet "democratic." Everything centralizes into a handful of massive platforms that can afford the legal burden, and they all implement strict, algorithmic moderation because that's the only thing that scales.

There's also the free speech argument. Section 230 doesn't just protect platforms; it protects your ability to publish online. When you post on Twitter, you're publishing. You're not a journalist; you don't have a newsroom behind you. But Section 230 lets you publish without facing the same liability risks as the New York Times. If Section 230 goes away, personal publishing becomes legally risky in ways it never was before.

Finally, there's the international angle. If the US kills Section 230, other countries might too. The EU is already creating digital regulations that essentially replicate Section 230's carve-outs while adding conditions. If the US repeals it completely, other democracies might follow, and authoritarian governments would have cover to build even more restrictive regimes. The internet would balkanize faster.

The Compromise Position: Carving Out Specific Harms

Between "repeal Section 230 entirely" and "leave it untouched" lies a middle ground. Most serious technologists and lawyers think the answer isn't radical change, but targeted modification.

The algorithmic amplification carve-out is one option. Section 230 would still protect platforms from being liable for the content users create and upload. But it wouldn't protect them for how the platform's algorithm amplifies or promotes that content. A recommendation system isn't user-generated content; it's platform engineering. If a platform makes a deliberate choice to amplify harmful content through algorithmic recommendation, maybe it shouldn't get Section 230 protection for that specific act.

This is narrower than full repeal. YouTube keeps Section 230 protection for hosting the videos. YouTube loses it for algorithmically recommending videos designed to radicalize viewers or addict children. The liability risk is specific to algorithmic choice, not hosting choice.

Then there's transparency. A compromise position would say: platforms keep Section 230 protection, but they have to publicly disclose how their moderation works and how their algorithms operate. No more secret rules. If TikTok's algorithm is deliberately designed for addiction, that becomes public knowledge. The market, regulators, and courts can respond with informed decisions.

Another option: tiered liability based on platform responsibility. A platform that takes moderation seriously, publishes clear policies, responds to complaints, and demonstrates good-faith effort to prevent harm might get full Section 230 protection. A platform that ignores reports of trafficking, doesn't moderate at all, and deliberately amplifies harassment might lose Section 230 protection. You're not eliminating the protection; you're making it conditional on basic responsibility.

The carve-out approach is the most politically viable. You can add specific, narrow carve-outs for specific harms without burning down the entire system. Addiction? Add a carve-out. Trafficking? Already have one. Child exploitation? Carve it out. Algorithmic amplification of misinformation? Carve it out. You end up with a version of Section 230 that's more limited but still exists, still protects basic hosting, but creates liability for specific, intentional harms.

The problem is that carve-outs create complexity. Every time Congress carves out an exception, courts have to interpret what that exception means. FOSTA was meant to target trafficking. Courts have interpreted it so broadly that some hosting companies refuse to host adult content entirely. Carve-outs have unintended consequences.

But they're probably the most realistic outcome. Complete repeal seems too extreme, affecting too many innocent platforms and users. Full preservation seems politically impossible. Targeted modification is the middle path.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in legal challenges and legislative efforts against Section 230, peaking in 2025 as debates intensify.

The Supreme Court Wildcard: What If They Overturn Precedent?

Here's the wildcard that keeps lawyers awake at night: the Supreme Court.

For thirty years, courts have consistently interpreted Section 230 broadly. The most famous case is Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy in 1995, which said that Prodigy, by moderating some content, was acting as a publisher and therefore liable for defamatory content. Congress wrote Section 230 specifically to overturn Stratton Oakmont. Courts have followed that precedent ever since.

But Supreme Court justices have started questioning it. Justice Thomas has written opinions suggesting that maybe the original Stratton Oakmont logic was right, and Section 230 is actually unconstitutional because it prevents platforms from being held liable for editorial choices. If platforms moderate content, they're making editorial decisions, and the First Amendment doesn't let you escape liability by moderating more. Conservative justices have signaled interest in revisiting this.

If the Supreme Court overturns Section 230 precedent—and it's a real possibility in the next few years—everything changes overnight. Courts would stop treating platforms as hosts. They'd start treating them as publishers. Liability would explode. The internet would not resemble what we know.

This is where the stakes really become clear. Congress is threatening repeal. Courts are narrowing it. The Supreme Court might overturn it entirely. Section 230 is under assault from every direction, and most people in Washington are cheering for its destruction.

International Implications: The EU Model and Beyond

America isn't alone in this. Other democracies are watching the Section 230 debate and making their own decisions.

The European Union created the Digital Services Act, which essentially replaces Section 230 with a more restrictive framework. European platforms still aren't liable for user content by default, but they have to follow strict rules about moderation, algorithmic transparency, and content removal. It's Section 230 with conditions. Platforms have to prove they're responsible, or they lose protection.

This creates a weird dynamic. If the US repeals Section 230 and the EU keeps a limited version with conditions, European platforms might actually have an advantage. They'll know exactly what the regulatory framework is. US platforms will face complete uncertainty.

India, the UK, Australia, and other democracies are all considering their own versions of Section 230 changes. Some are going the EU route: conditions and conditions. Some are going further, imposing data localization rules and additional liabilities. Canada has proposed a bill that would make platforms liable for algorithmic amplification of harmful content.

The global pattern is clear: Section 230-style protections are going away, being conditioned, or being narrowed. The question isn't whether change is coming. The question is how fast and how extreme.

For the US, this creates competitive pressure. If Europe has a clear regulatory framework for platforms, and America has chaos, where will new platforms locate? Probably Europe. Or China, where there's no liability at all because there's no free speech. The middle ground—free platforms with moderate accountability—seems to be disappearing globally.

The Durbin-Graham Bill proposes a complete repeal of Section 230, showing the highest impact level. The EARN IT Act and Kids Online Safety Act propose conditional protections, reflecting significant but slightly lower impacts. (Estimated data)

The Economic Impact: Who Bears the Cost?

Let's talk money, because policy doesn't exist in a vacuum. It has costs and benefits.

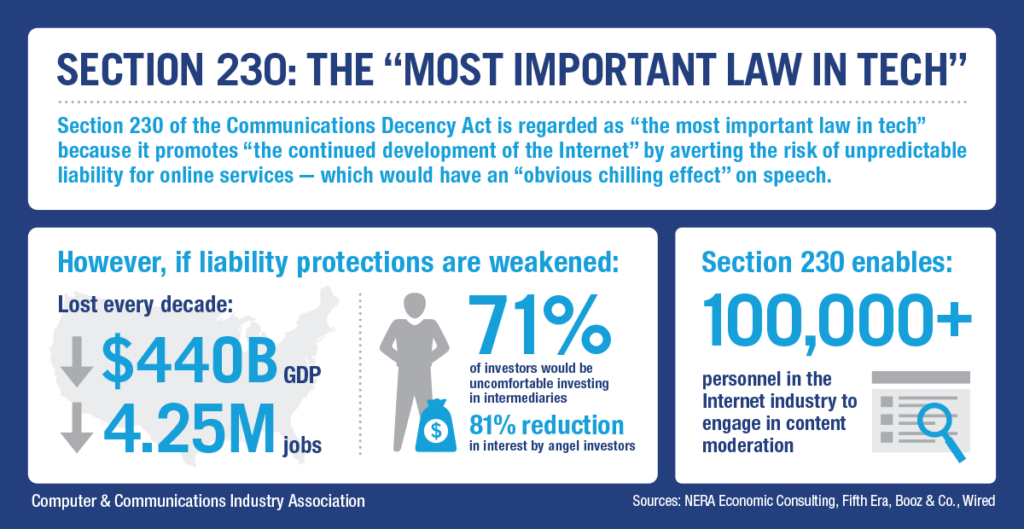

The economic impact of repealing Section 230 would be catastrophic for some sectors, massively beneficial for others. Content moderation would become a massive industry. You'd need millions of moderators, AI moderation systems, legal consultants, compliance officers. That's jobs and spending, which economists call a benefit. But it's also costs that get passed to users through higher fees.

Small startups would be effectively banned. A startup with 100 users can't afford $1 million in annual legal exposure. Section 230's absence means any startup hosting user content faces potentially unlimited liability. The barrier to entry explodes. Established platforms with legal resources survive and grow. Startups get crushed.

This is actually a hidden feature of repealing Section 230 for big tech companies. They're rich enough to survive. Competitors aren't. Repealing Section 230 in the name of making tech companies accountable actually makes them more dominant by eliminating competition.

The content industry would shift dramatically. If platforms can't afford to host user content, they'd shift toward commissioned content, creator partnerships, and curated experiences. This is actually better for professional creators but worse for casual users. The barrier to having your stuff on the internet goes up.

International competitiveness is also a factor. Europe and Asia would likely develop their own platforms if US platforms face unlimited liability. Today, American platforms dominate globally partly because Section 230 lets them operate with manageable legal risk. Without it, that advantage disappears. We might see a genuine decentralization of the internet along geographic lines.

The moderator job market would explode in size and terrible working conditions. Content moderation is one of the most psychologically damaging jobs that exists. People watch hours of child abuse, murder videos, and extreme violence. Wages are typically $10-15 per hour. Expanding this industry massively would mean hiring even less qualified people for even worse working conditions. That's not a benefit; it's a tragedy that we'd celebrate as accountability.

Alternative Frameworks: What Could Replace Section 230?

If Section 230 dies, what takes its place?

One option: strict liability with safe harbors. Platforms are liable by default but get protection if they follow specific moderation best practices. The problem: Congress would have to define what best practices are, and reasonable people disagree enormously about content moderation.

Another option: a licensing system. Platforms get a license to operate that comes with conditions, and they can lose the license if they violate those conditions. This is roughly what the EU is implementing. It's more predictable than Section 230 but also more restrictive. Small platforms struggle. Government gets more control.

A third option: insurance-based liability. Instead of government creating rules, the insurance market creates incentives. Platforms buy liability insurance, and insurance companies set the conditions for coverage. This is market-based instead of regulatory, but it shifts the rules from Congress to insurance companies, which is its own problem.

A fourth option: distributed liability. Section 230 protection goes away, but platforms can't be sued for user content—users can. If someone posts defamatory content, they're liable, not the platform. This preserves the ability to host user content but shifts liability to the person creating the content. Sounds fair in theory; in practice, this just means anonymous users with no assets post terrible stuff and platforms can't do anything about it.

None of these alternatives is obviously better than Section 230. They all have downsides. But if Section 230 dies, we'll probably end up with some hybrid of these options, and it'll be chaotic for a decade while courts interpret the new rules.

The Addiction Angle: How Section 230 Enables Design-Based Harm

One of the most sophisticated arguments against Section 230 focuses on algorithmic design and addiction.

The claim is simple: Section 230 protects Facebook from being liable for user content—the posts your friends make, the videos people upload. But it doesn't have to protect Facebook from being liable for Facebook's algorithmic choices. The algorithm that decides what content shows up in your feed? That's not user-generated. That's Facebook's product.

Internal documents from Meta show that executives knew their engagement-maximizing algorithms were specifically designed to create addiction, especially in teenagers. The algorithm learns what keeps you scrolling and amplifies that, whether it's anxiety-inducing conspiracy theories, body-image-destroying beauty standards, or straight-up misinformation. The algorithm works. People get addicted. Mental health suffers.

Section 230 has been interpreted to protect Meta from liability for this design choice, because the content itself is user-generated. But courts are starting to distinguish between the content and the amplification. If you sue Meta because a user uploaded a video, Section 230 might protect them. If you sue Meta because their algorithm deliberately amplified that video to vulnerable teenagers in ways designed to cause harm, Section 230 might not apply.

This distinction could reshape Section 230 without repealing it. You're not saying platforms can't host user content. You're saying they can't deliberately weaponize their algorithm against users and hide behind Section 230.

The tricky part is proving intent. How do you prove that the algorithm was deliberately designed to cause harm versus just optimized for engagement? Internal documents help, but most platforms don't leak internal memos. You'd need discovery, and discovery costs money. The litigation would be massive.

But this is probably the most realistic path forward: narrowing Section 230 to exclude algorithmic amplification while preserving it for basic hosting. It's a middle ground that addresses genuine harms while preserving the core function of Section 230.

The Global Internet Implications: Balkanization and Control

One implication of weakening US Section 230 is that it accelerates internet balkanization.

Right now, a handful of American platforms dominate the global internet. This has obvious downsides: American values get imposed everywhere, American regulations affect everyone, American companies control global discourse. But it also has an upside: there's a single, relatively open internet where people from different countries can interact.

If US platforms face unlimited liability for hosting international content, they'll probably geo-fence more heavily. The EU has GDPR rules, so platforms comply with GDPR for Europe. China has strict censorship rules, so platforms either leave China or comply with censorship. If the US creates unlimited liability for harmful content, platforms will probably just not serve the US, or they'll implement American censorship rules globally to reduce liability.

This creates incentives for countries to build their own platforms. China already did this successfully. The EU is experimenting with European social networks. India is backing local platforms. If US platforms become too legally risky, other regions will deliberately build alternatives. The internet fragments along geographic lines.

Authoritarian governments actually benefit from this scenario. If the US kills Section 230 and causes balkanization, authoritarian governments can point to the chaos and say "See? We need government control to prevent this mess." They'll implement strict, centralized platforms with Chinese-style control. The unintended consequence of trying to make the internet safer might be making it more subject to government control globally.

This is the geopolitical dimension most American politicians miss. Section 230 isn't just about platform liability. It's about whether the internet remains globally connected or becomes a collection of national internets.

What Happens to Your Data and Privacy If Section 230 Changes

Here's something nobody talks about: Section 230 changes could actually expand data collection and surveillance, not reduce it.

If platforms face liability for user-generated content, they'll need to monitor everything more aggressively. That means more data collection, more algorithmic scanning, more surveillance infrastructure. Your posts, your messages, your uploads—all get scanned by increasingly sophisticated systems trying to prevent liability.

So the platforms become more surveillant in the name of responsibility. They collect more data about you to predict what might cause liability. They build better models of who you are and what you'll do. They use that data to target you with more precision.

Paradoxically, you might get a "safer" internet with more moderation and less terrible content, but at the cost of being surveilled more intensely. That's the trade-off that Section 230 changes might create.

The privacy advocates who want Section 230 reformed might be opening a door to the kind of digital surveillance they claim to oppose. The platforms defending Section 230 are actually defending your ability to post pseudonymously and be somewhat anonymous online. Without that protection, platforms have to know exactly who you are before they can be confident they won't face liability for your content.

The Human Stories: Why Parents Are Angry

Turn past all the legal theory and legislative maneuvering, and you find human tragedy.

Parents have shown up at Congress with photos of dead children. A teenager who was sold for sex through an app where the platform claimed Section 230 protection. A young person who bought counterfeit fentanyl through encrypted apps where the platform claimed it couldn't be held liable. A kid who committed suicide after being cyberbullied relentlessly on a platform that, when the parents asked for help, said "we're not responsible for user content."

These stories are real. The harm is real. And Section 230 is protecting the platforms from accountability in many of these cases.

At the same time, Section 230 is also protecting the platforms that host abuse support groups. It protects the communities where people find help. It protects activist forums where dissidents in authoritarian countries can speak freely. It protects your ability to post your thoughts online without worrying that every typo or misstatement might result in personal liability.

The debate over Section 230 is ultimately a debate about acceptable risk. We can't have perfect safety online. We can have more platform accountability, but only by accepting less user freedom. We can have more user freedom, but only by accepting more platform negligence. The question is where the line belongs.

Right now, Section 230 puts the line pretty far toward user freedom. The movement to reform or repeal it is trying to move the line toward accountability. Whether that's the right move depends on what trade-offs you're willing to accept.

2025 and Beyond: The Timeline and What's Likely to Happen

Let's be concrete about timing because vagueness makes this all feel theoretical.

We're probably 18 to 24 months away from significant legislative action. Multiple bills are in Congress. Some have bipartisan support. The political moment is right for change. We're likely to see either a compromise bill that modifies Section 230 rather than repealing it, or a phased implementation that gives platforms time to adjust.

Complete repeal seems unlikely because the chaos would be too obvious. Courts would get immediately flooded. Platforms would shut down. Congress would look incompetent. A more likely outcome is a modified Section 230 that:

- Adds carve-outs for algorithmic recommendation of harmful content

- Requires transparency in moderation practices and algorithmic operation

- Creates conditions for Section 230 protection based on demonstrated responsible behavior

- Adds specific exemptions for addiction-related and trafficking-related content

This would happen somewhere in the next 24 to 36 months, probably.

In parallel, courts will keep narrowing Section 230 through litigation. The addiction cases will continue. The algorithmic amplification cases will continue. Some will succeed, some will fail. But the trend is clearly narrowing.

The Supreme Court wildcard remains. If they revisit Section 230 precedent in the next few years, everything accelerates. The Court could overturn precedent and basically repeal Section 230 without Congress doing anything.

The most likely scenario: by 2027 or 2028, Section 230 will look significantly different than it does today. Not gone, but narrower. Platforms will face new categories of liability. The internet will be more moderated and less anonymous. User-generated content will become riskier to host. The ecosystem will shift toward more professional, curated content and away from open platforms.

The less likely but possible scenario: a Supreme Court decision overturns Section 230 precedent, or Congress repeals it entirely. Chaos follows. It takes years to establish a new framework. Some platforms shutdown. Others become more restrictive. The internet becomes smaller and more centralized.

FAQ

What exactly is Section 230 and why does it matter?

Section 230 is a 26-word law passed in 1996 that shields online platforms from liability for user-generated content. It's the legal foundation that allows YouTube, Twitter, Reddit, and virtually every user-driven platform to exist without facing crushing lawsuits for everything their users post. Without Section 230, platforms would either have to pre-approve all content (killing open internet) or face limitless legal liability.

How has Section 230 survived for 30 years when so many people want it gone?

Section 230 survived because repealing it seemed unthinkable—the chaos would be obvious and immediate. Platforms would shut down or become heavily censored. Congress knew this, so even when they complained about Section 230, they didn't actually repeal it. But 2025 is different. The political calculation has shifted. Enough legislators now believe the harms of Section 230 outweigh the chaos of changing it, and that's made repeal seem possible for the first time.

What would happen if Section 230 actually got repealed entirely?

If Section 230 fully disappeared, platforms would face unlimited liability for user content and would have to choose: become heavily curated (like Netflix, where only pre-approved content appears) or become lawless (like 4chan). The middle ground would die. Small platforms and communities would disappear entirely due to liability risk. The internet would become more centralized, more controlled, more moderated, and less diverse. International platforms would likely withdraw from the US market, fragmenting the global internet.

What are the most serious legislative threats to Section 230 right now?

The Durbin-Graham bill proposes a complete repeal with a two-year sunset. The EARN IT Act would strip Section 230 protection unless platforms adopt government-mandated best practices (including encryption backdoors). The Kids Online Safety Act would remove protection unless platforms prove they're protecting minors adequately. Multiple other bills propose carve-outs for specific harms like addiction or algorithmic amplification. Most of these have real support and could move through Congress in 2025 or 2026.

Could the courts overturn Section 230 without Congress doing anything?

Yes. The Supreme Court could overturn decades of precedent and basically repeal Section 230 through judicial decision. Justice Clarence Thomas has already written opinions suggesting this is possible. If the Court decides that moderating content makes platforms into publishers, Section 230 protection might disappear entirely. This is probably the wildcard scenario that keeps tech lawyers awake at night.

What would a compromise version of Section 230 look like?

A realistic compromise would preserve Section 230's core protection for hosting user content while adding carve-outs and conditions. Platforms might lose Section 230 protection specifically for algorithmic amplification of harmful content, while keeping it for hosting. They might have to publicly disclose moderation policies and algorithmic operation. They might get conditional protection based on demonstrable good-faith moderation efforts. This would narrow Section 230 without destroying it entirely.

How would losing Section 230 affect small creators and communities?

Small platforms and independent communities would be devastated. A tiny Discord server for people with a rare disease, a Lemmy community for a niche hobby, a small forum for local organizing—all would face unmanageable liability if they lost Section 230 protection. Most would simply shut down rather than face legal exposure. The barrier to hosting user content would jump from basically zero to millions of dollars in legal risk and infrastructure. Only large, well-funded platforms would survive.

Is the EU's approach better than Section 230?

The EU's Digital Services Act creates a middle ground with conditions. Platforms still have liability protection but have to follow strict rules about moderation, transparency, and content removal. It's less wild-west than Section 230 but more protected than a full repeal. Whether it's better is subjective. It's definitely more regulated and creates more government control over content decisions. It also provides clarity about what's allowed. There are trade-offs both directions.

Could Section 230 changes actually make the internet less safe and more controlled?

Yes. Ironically, trying to make platforms more accountable through Section 230 changes could result in more surveillance, more censorship, and more government control. Platforms facing liability would implement aggressive content scanning and data collection. Authoritarian governments would use the chaos to justify building state-controlled alternatives. The internet would become more fragmented and more controlled. The unintended consequences could be worse than the original problems.

What should platforms and communities do to prepare if Section 230 changes?

Start now: document moderation efforts, create clear community policies, implement content filtering and monitoring infrastructure, build evidence of good-faith responsibility, and establish legal hedges. If you operate a platform with user content, assume Section 230 might not exist in 2027 and build accordingly. Consult with lawyers about liability exposure. Join industry associations pushing for reasonable Section 230 reform rather than radical repeal. The time to prepare is now, not when the law changes.

Section 230 is a law written for an internet that doesn't exist anymore. It was created for small bulletin boards and chat rooms, not billion-user platforms with algorithms designed by artificial intelligence. The question isn't whether Section 230 needs updating. The question is how much we're willing to break in the process of fixing it. The answer to that question will shape the internet for the next thirty years.

Key Takeaways

- Section 230's 26-word legal protection has enabled the modern internet for 30 years but faces unprecedented threats from legislation, litigation, and judicial reinterpretation in 2025.

- Multiple bills with bipartisan support propose repealing, sunsetting, or conditionally limiting Section 230 within 2-5 years, representing the most serious legislative threat yet.

- Courts are narrowing Section 230 through litigation focused on algorithmic amplification, addiction harms, and trafficking, potentially creating new liability categories without legislative action.

- The Supreme Court could overturn Section 230 precedent entirely, making judicial decisions potentially more consequential than legislative action.

- Repealing Section 230 would paradoxically increase platform surveillance, accelerate internet balkanization, and eliminate competition, harming user freedom while attempting to increase accountability.

- Compromise approaches like carving out algorithmic amplification or requiring transparency offer a middle path between complete repeal and full preservation.

Related Articles

- Tech Politics in Washington DC: Crypto, AI, and Regulatory Chaos [2025]

- How Roblox's Age Verification System Works [2025]

- Uber's $8.5M Settlement: What the Legal Victory Means for Rideshare Safety [2024]

- EU's TikTok 'Addictive Design' Case: What It Means for Social Media [2025]

- X's AI-Powered Community Notes: How Collaborative Notes Are Reshaping Fact-Checking [2025]

- Are VPNs Legal? Complete Global Guide [2025]

![Section 230 at 30: The Law Reshaping Internet Freedom [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/section-230-at-30-the-law-reshaping-internet-freedom-2025/image-1-1770559573120.jpg)