Uber's $8.5M Settlement: What the Legal Victory Means for Rideshare Safety

A federal jury in Phoenix made history in September 2024 when it ordered Uber to pay $8.5 million to a passenger named Jaylynn Dean, who accused one of the company's drivers of rape. This wasn't just another lawsuit settlement. It was a bellwether trial, which means it's designed to test the waters for thousands of similar cases pending against the ride-sharing giant. The verdict sent shockwaves through the industry, forcing conversations about contractor liability, corporate responsibility, and what happens when a passenger's safety fails catastrophically.

For Uber, the decision contradicts years of legal arguments that the company bears no responsibility for driver misconduct because drivers are independent contractors, not employees. For passengers, it represents a potential turning point. The case opened a window into Uber's safety protocols, its knowledge of high-risk riders, and whether the company deliberately avoided in-car camera technology to protect its growth. What makes this case especially significant is that despite the jury finding Uber liable, they also determined the company wasn't negligent in its safety practices. That contradiction matters enormously for the remaining 3,500 similar cases still in the pipeline.

This story reaches far beyond one passenger's tragedy. It touches on gig economy fundamentals, corporate liability frameworks, and whether rideshare companies can maintain a "we're just a platform" defense while wielding massive control over who drives and how. Let's walk through what happened, why it matters, and what comes next for passengers and the rideshare industry.

TL; DR

- A federal jury ordered Uber to pay $8.5 million to a passenger who accused her driver of rape in 2023, establishing potential precedent for 3,000+ similar cases

- Contractor vs. liability debate: The jury found Uber liable despite drivers being independent contractors, contradicting the company's core legal defense

- Safety systems questioned: Evidence showed Uber flagged the passenger as high-risk but didn't notify her, and the company reportedly resisted in-car cameras

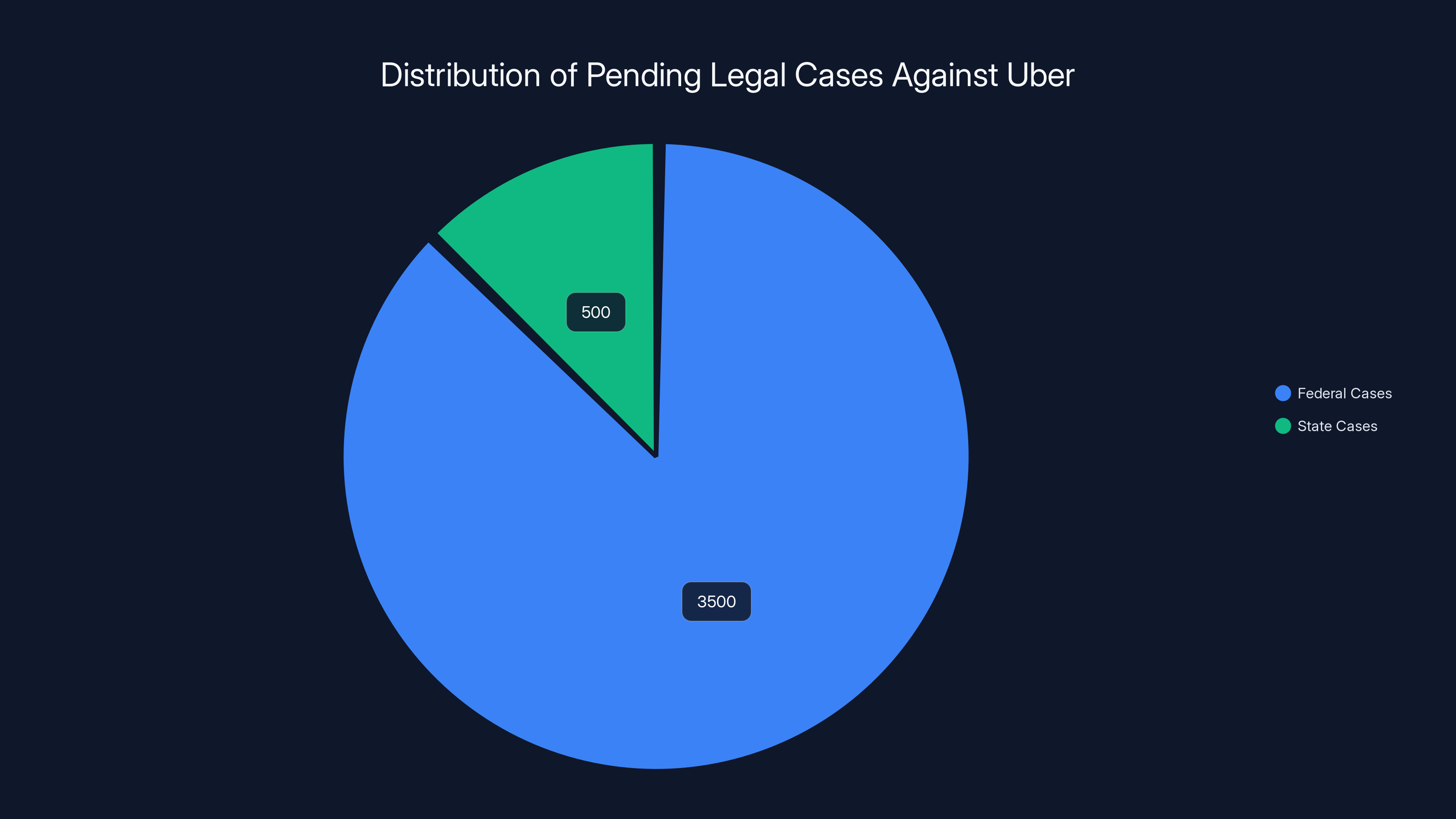

- Massive litigation ahead: Uber faces 3,500 consolidated federal cases and 500 more in California state court with similar allegations

- Appeal and precedent: Uber plans to appeal, but if upheld, the verdict could reshape settlements for thousands of pending cases

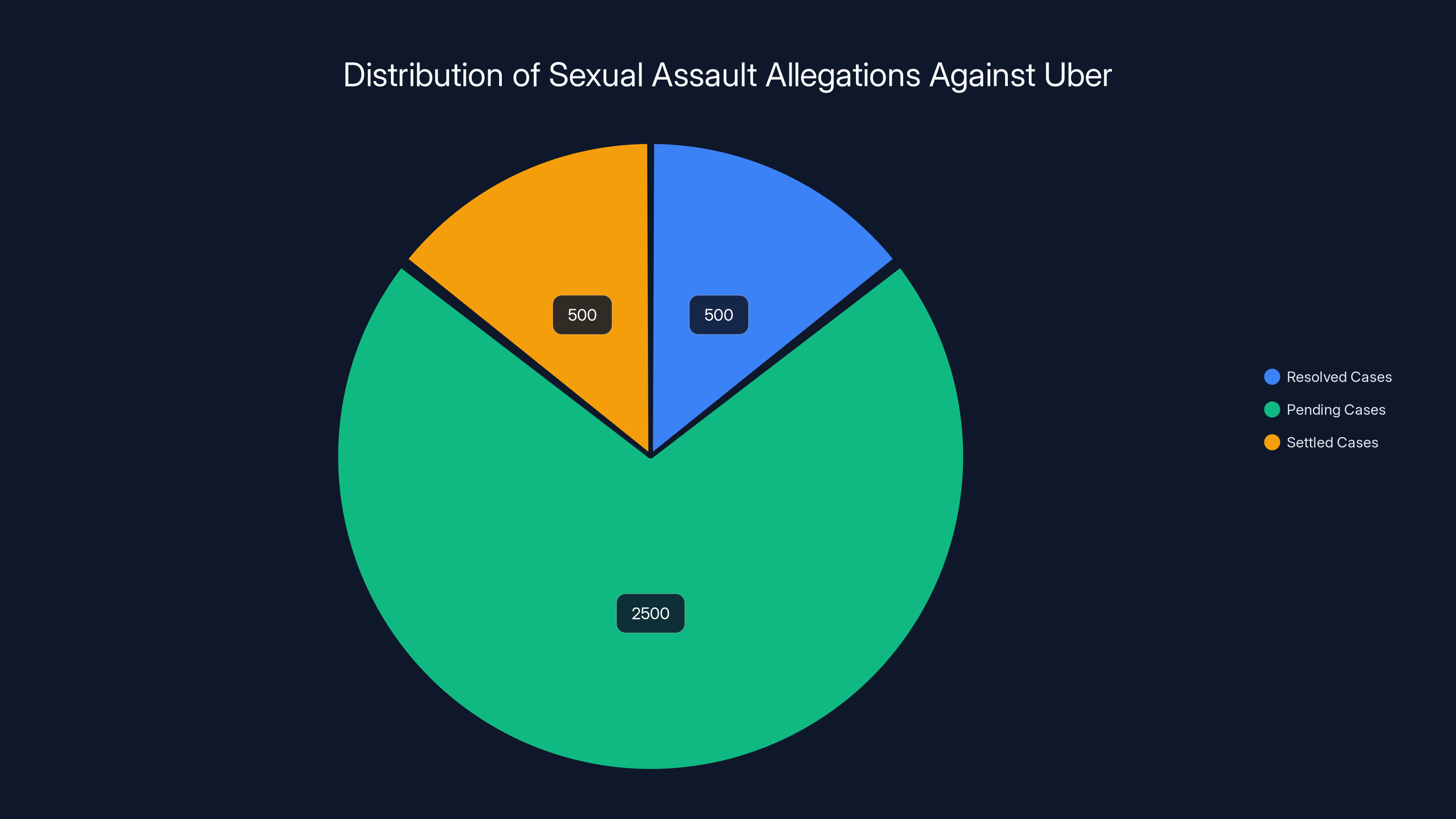

An estimated breakdown of the 3,500 sexual assault allegations against Uber shows a majority of cases are still pending resolution. Estimated data.

The Case: What Actually Happened to Jaylynn Dean

Jaylynn Dean's evening started like countless rideshare rides across America. She'd been celebrating a major personal milestone: passing her written exam to become a flight attendant. That accomplishment deserved celebration, so she spent time at her boyfriend's apartment, then decided it was time to head home. Intoxicated and wanting a safe ride, she opened the Uber app on her phone and requested a ride.

What happened next would become the centerpiece of a $8.5 million federal judgment.

Dean's driver allegedly deviated from the normal route, steering the car toward a dark parking lot. Once there, he assaulted her in the backseat. The alleged attack wasn't a case of mistaken signals or miscommunication. By all accounts, it was a violent crime committed by someone who had access to a vulnerable passenger because of Uber's systems.

The timing of Dean's ride matters contextually. She was intoxicated, which isn't uncommon for Uber rides late at night. But here's where Uber's systems come into play: unbeknownst to Dean, Uber's internal algorithms had flagged her as a "high-risk" rider just before her ride was assigned. The company's machine-learning model had assessed that she faced elevated danger on that particular ride. The jury would later learn that Uber had this information but chose not to warn her.

Dean filed her lawsuit against Uber, not just the driver. That distinction is crucial. She wasn't seeking compensation through a typical criminal case against an individual who happened to use Uber. She was arguing that Uber itself bore responsibility for allowing this interaction to happen while possessing knowledge that the ride posed serious risks.

Uber's defense strategy relied on a simple argument: we're a technology platform connecting independent contractors with passengers. The driver committed the crime, not us. The company argued the driver had no criminal history, had completed safety training, and had received excellent feedback from previous passengers. From Uber's perspective, the company had done everything right.

But the jury disagreed.

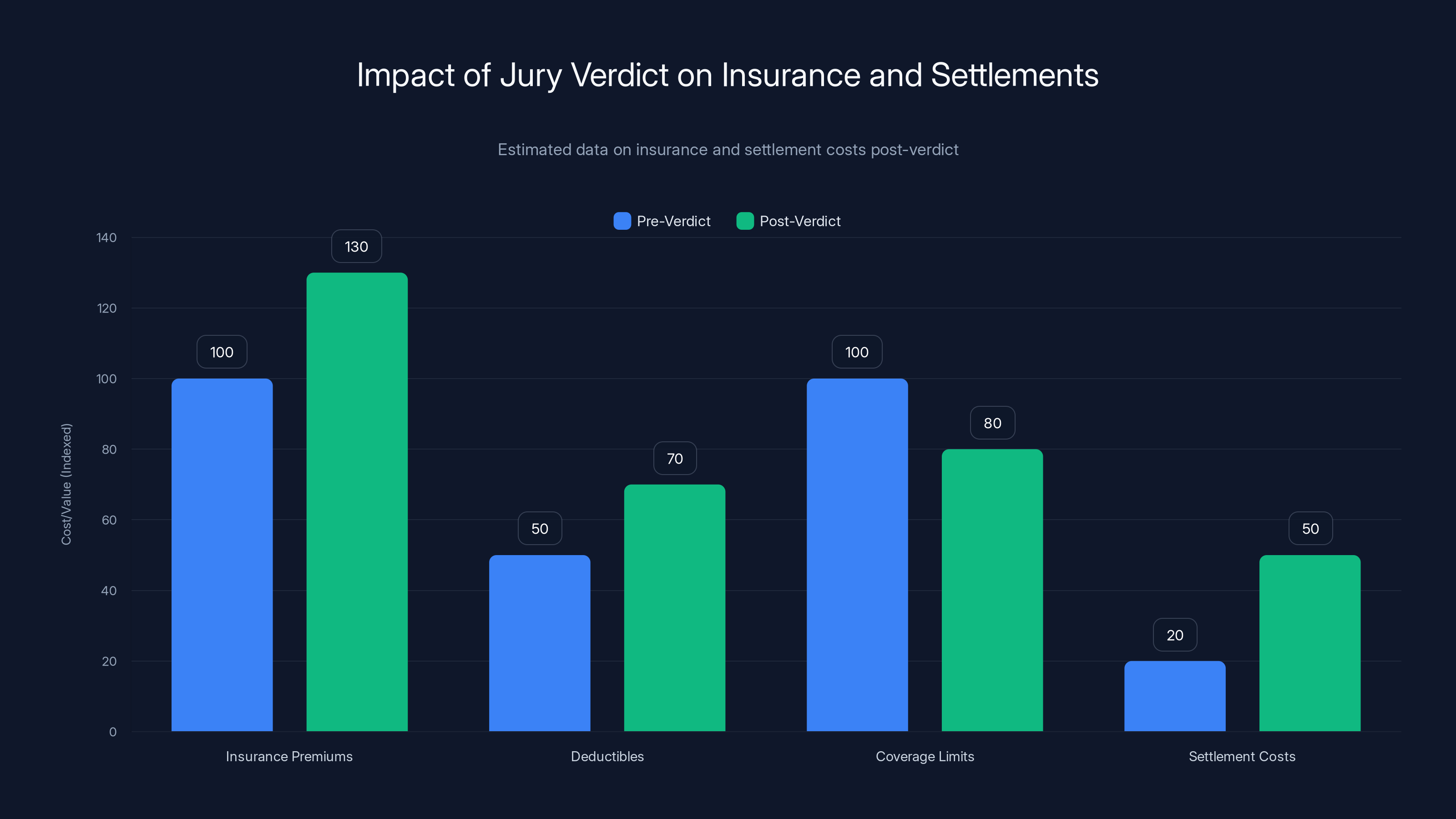

The $8.5 million verdict likely increases insurance premiums and deductibles while reducing coverage limits. Settlement costs may rise significantly as insurers prefer settling over risking higher jury awards. (Estimated data)

Understanding Bellwether Trials and Their Significance

The term "bellwether" comes from medieval sheep herding. The lead sheep, wearing a bell, would guide the flock. If you watched the bellwether, you'd understand where the entire flock was heading. In modern litigation, a bellwether trial serves exactly that purpose.

Uber currently faces roughly 3,500 consolidated sexual assault and misconduct cases in federal court. Processing each one individually would take decades and cost billions. Instead, lawyers for both sides agreed to select a small number of representative cases to go to trial first. These bellwether cases test key legal questions that apply to all the pending lawsuits. The outcome helps both sides understand likely jury attitudes, the strength of evidence, and the range of potential damages.

Dean's case was chosen as one of these test cases specifically because it represented common fact patterns among the allegations. A vulnerable passenger, alleged driver misconduct, questions about Uber's safety protocols, and arguments about contractor liability. If her case succeeded, it suggested many others might too. If it failed, defendants could gain confidence that jury verdicts would favor Uber's arguments.

The jury's decision to hold Uber liable was shocking to many legal observers because it punctured the "we're just a platform" defense that rideshare companies have leaned on for years. Lyft, Door Dash, and other gig economy companies have built their business models on the idea that they facilitate transactions between independent parties and bear no responsibility for individual worker behavior. The Dean verdict challenged that foundational assumption.

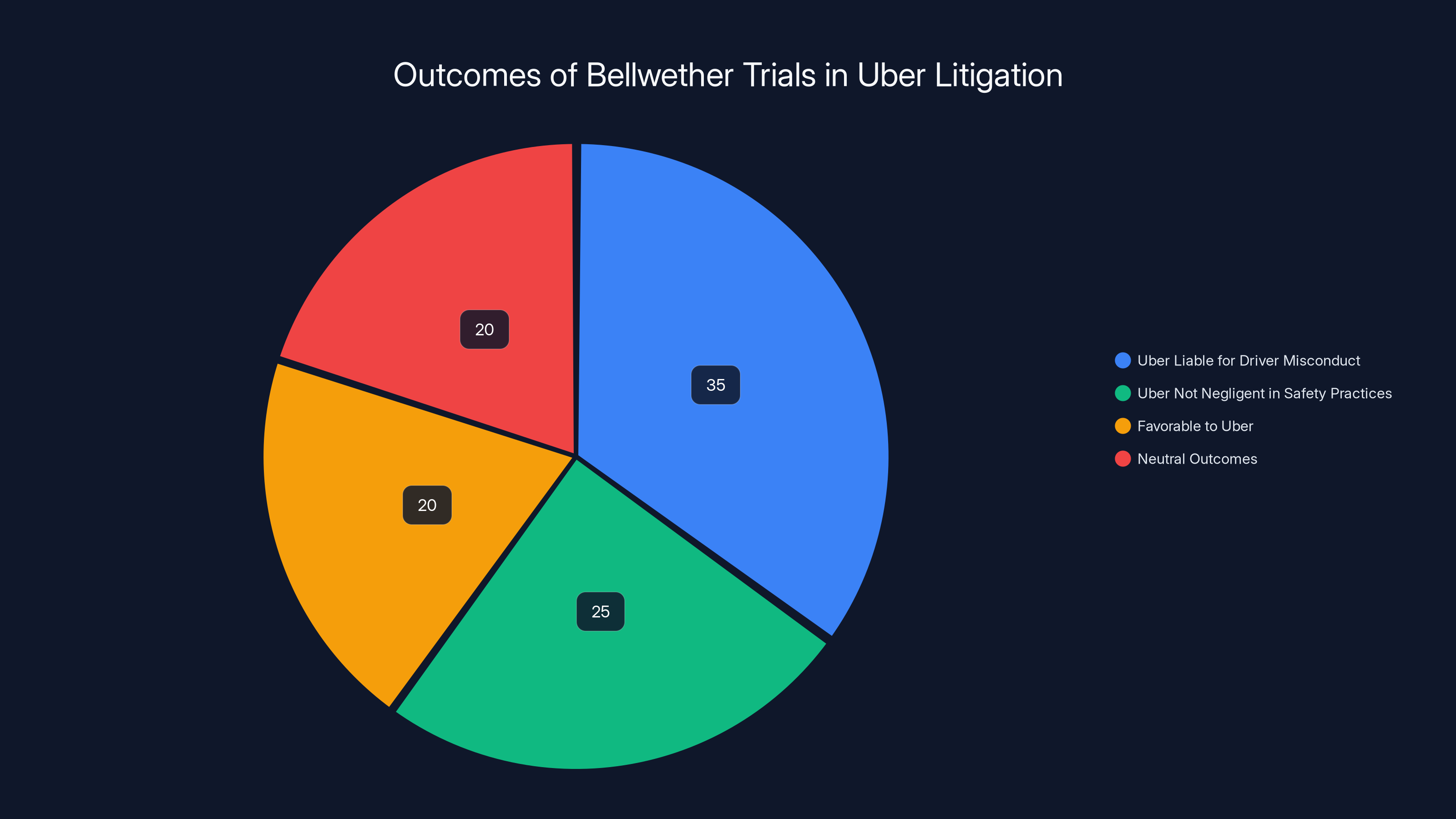

However, the jury made a critical distinction. They found Uber liable for the driver's misconduct, determining he was acting as an agent of the company when he committed the alleged assault. But they simultaneously decided Uber wasn't negligent regarding its safety practices. The company's app safety features weren't deemed faulty. This creates a strange legal space where Uber is responsible for what happened but didn't do anything wrong. That contradiction could affect how the remaining cases proceed.

Bellwether trials also generate enormous media attention, which shapes public perception and influences settlement negotiations. When a jury awards $8.5 million to a single plaintiff, it changes the calculus for thousands of similar cases. Defense lawyers now have to explain to insurance companies and corporate leadership why settling might be cheaper than litigating.

Uber's Safety Systems: What They Got Right and Wrong

Uber presented an extensive defense focused on its safety infrastructure. The company detailed background checks, driver screening processes, in-app safety features, and customer feedback mechanisms. By most metrics, Uber had built safety systems that appear comprehensive and responsible.

The background check process screens drivers for criminal history. Passengers can see driver ratings and vehicle information before accepting a ride. The app provides real-time trip tracking and emergency contact options. Drivers receive training on professional conduct. These features represent genuine efforts to reduce risk compared to hailing a random taxi from the street.

But the evidence presented at trial revealed gaps in these systems. The most damaging revelation involved Uber's machine-learning tool, which had flagged Jaylynn Dean as a high-risk rider for serious safety incidents immediately before her ride was assigned. The tool worked. It correctly identified elevated danger. But the system had no mechanism to notify the passenger that she was at high risk. Uber possessed critical safety information and withheld it from the person it was meant to protect.

This wasn't a technical failure or an oversight. Dean's lawyers presented documents suggesting Uber had resisted implementing in-car cameras because they feared it would slow user growth. If Uber installed cameras in every vehicle, the company's argument went, new drivers might be discouraged from signing up. The cameras could slow onboarding. Growth might decelerate. So the company chose not to implement them, according to the evidence presented.

Internally, Uber knew these systems mattered. The company had invested in machine-learning risk assessment. The technology existed to screen for dangerous situations. But the company didn't create systems where passengers received warnings matching the information Uber possessed. It's the difference between having a fire alarm and ringing it when there's a fire.

Jury members heard from Dean's lawyers that Uber essentially told passengers: "We've created a safe space where you don't need to worry about sexual assault." That messaging, combined with evidence that the company knew about risks but didn't communicate them, created a powerful narrative. Uber created an illusion of safety while possessing knowledge it didn't share.

The company's response emphasized investment in rider safety. An Uber spokesperson told major news outlets that the verdict "affirms that Uber acted responsibly and has invested meaningfully in rider safety." But that statement doesn't address the core jury finding: that Uber was liable for the alleged rape despite the driver being an independent contractor. The spokesperson also announced the company plans to appeal, suggesting Uber doesn't accept the jury's logic.

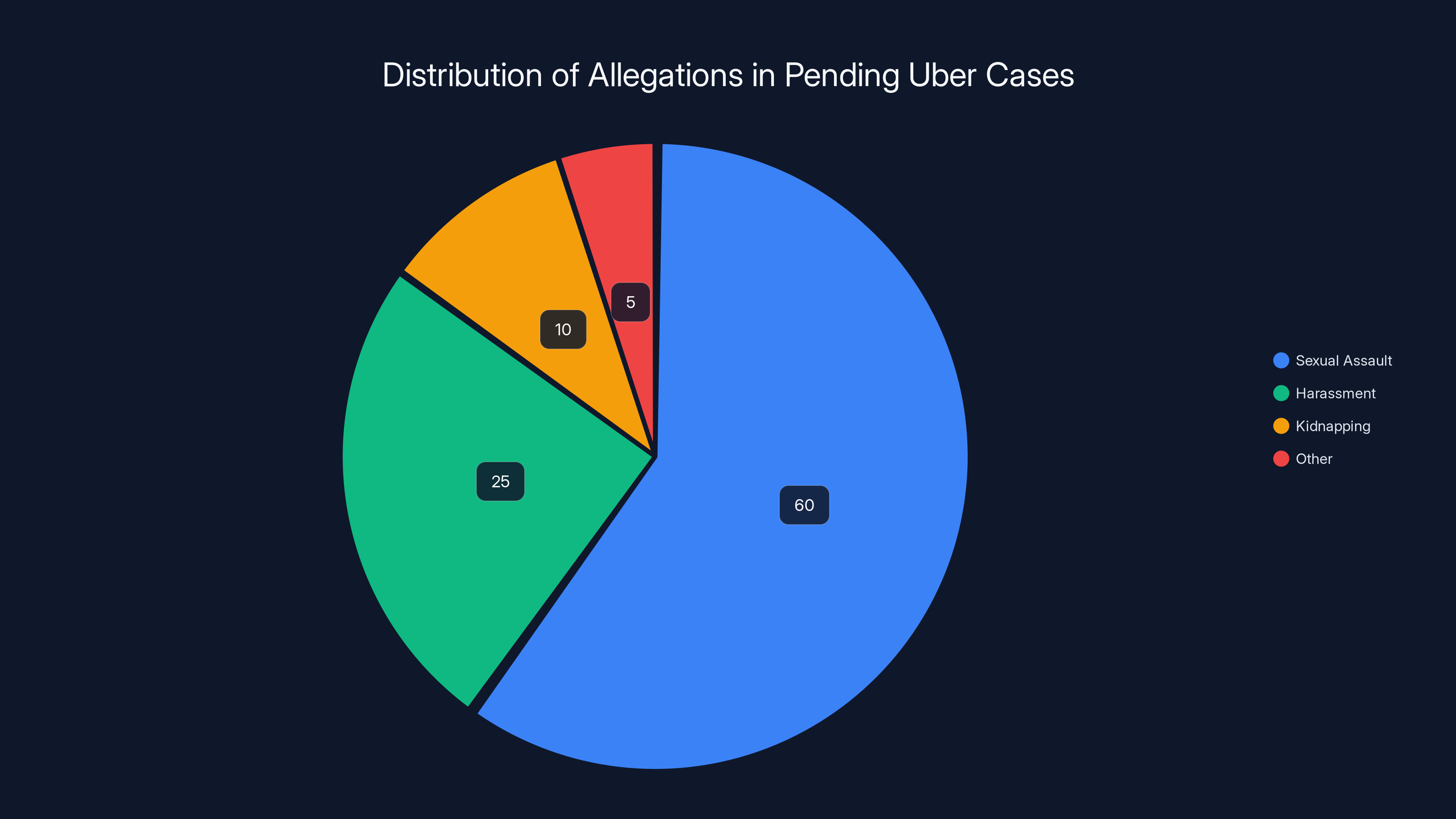

Estimated data suggests that the majority of the 3,500 pending cases involve sexual assault allegations, followed by harassment and kidnapping. This distribution highlights the primary concerns in the litigation against Uber drivers.

The Independent Contractor Problem

The entire gig economy is built on independent contractor classification. Drivers for Uber and Lyft aren't employees. They're independent contractors who provide their own vehicles, set their own schedules (within parameters), and technically run their own small businesses as ride providers. This classification offers massive benefits to Uber.

Employees come with significant costs. The company would need to provide benefits, workers' compensation insurance, unemployment insurance, and payroll taxes. Employees can be fired only for legal reasons, creating potential wrongful termination litigation. Training employees requires investment. The independent contractor model strips away these costs and liabilities. Uber becomes a platform connecting contractors with customers, rather than a business responsible for its workforce.

This classification also shields Uber from certain liability. If a driver were an employee, Uber would be automatically liable for the driver's misconduct committed during employment, a concept called respondeat superior. With independent contractors, Uber could argue the driver acted on their own behalf, not on Uber's behalf, so the company bears no responsibility.

The Dean case fundamentally challenges this logic. The jury decided that even though the driver was an independent contractor, he was acting as an agent of Uber when the alleged assault occurred. The driver wasn't doing something for himself; he was performing a service on Uber's platform, using Uber's systems, within Uber's processes. By that logic, the driver was functioning as Uber's agent at the moment of the alleged crime.

This distinction has enormous implications. If courts begin accepting that contractors can be agents of the platform in certain contexts, it expands corporate liability significantly. Uber could theoretically be held responsible for contractor misconduct even though the contractors aren't employees. That inverts the entire cost-benefit calculation of the independent contractor model.

Uber will argue on appeal that the jury misunderstood the legal definition of agency. The company will contend that independent contractors, by definition, can't be agents. But the jury's decision suggests there are limits to how far companies can distance themselves from contractor behavior when the company's platform, systems, and knowledge facilitate harmful interactions.

Other gig economy companies are watching closely. If the Dean verdict survives appeal, it could reshape liability for Door Dash (drivers), Task Rabbit (taskers), Fiverr (freelancers), and countless other platforms built on contractor models. That's why Uber is appealing. That's why this case matters far beyond one passenger's tragedy.

The 3,500 Cases Pending in Federal Court

Dean's case is one test case among hundreds waiting for jury decisions. Approximately 3,500 sexual assault and misconduct allegations against Uber drivers are consolidated in federal court in Phoenix, presided over by Judge Dominic Lanza. These cases allege incidents ranging from sexual assault to harassment to kidnapping. Most occurred between 2010 and 2024, though allegations continue to accumulate.

The consolidation process, called multidistrict litigation, groups geographically dispersed cases together for efficiency. Rather than having identical legal issues litigated in dozens of courts nationwide, all cases go to one judge. This saves the legal system enormous resources and ensures consistency. But it also creates pressure points. One judge's decisions affect thousands of cases simultaneously.

When a bellwether verdict like Dean's is rendered, the pressure intensifies. Defense counsel must now explain to clients, insurance carriers, and corporate boards why the company should risk more trials when a jury just awarded $8.5 million to a single plaintiff. Insurance companies may recalculate their exposure. Settlement negotiations may accelerate. Some defendants will become more willing to settle at higher amounts to avoid jury verdicts in other cases.

Conversely, plaintiffs' lawyers gain confidence. They now have a jury verdict suggesting juries will hold Uber liable for contractor misconduct. They can point to the Dean case when negotiating settlements for other plaintiffs. The verdict becomes a benchmark, whether Uber accepts it or not.

The remaining cases involve similar fact patterns. Riders alleging assault by drivers. Questions about whether Uber knew about risks and failed to communicate them. Arguments about safety training and background checks. Uber will likely argue in each case that it acted responsibly and invested in safety, just as it did in Dean's trial. But juries have now seen a precedent where that defense wasn't sufficient.

Some cases may be stronger than Dean's. Some may be weaker. Background facts vary. Evidence differs. Witness credibility fluctuates. But the bellwether verdict establishes a baseline expectation about jury attitudes. That changes settlement dynamics fundamentally.

The 3,500 cases represent enormous financial exposure for Uber. Even if only 10% settle or win at the average bellwether trial award of

Estimated data suggests that bellwether trials in Uber's litigation may result in varied outcomes, with a significant portion potentially holding Uber liable for driver misconduct while not finding negligence in safety practices.

California State Court: Another 500 Cases

While 3,500 cases proceed in federal court in Phoenix, an additional 500+ sexual assault allegations are pending in California state courts. California's legal system operates independently from the federal system, which means Uber faces parallel litigation in two separate judicial systems with different rules, judges, and jury pools.

California's legal landscape has historically been more favorable to plaintiffs in many contexts. The state's courts have been aggressive about expanding corporate liability. California juries tend to be sympathetic to individual plaintiffs against large corporations. That geography matters for settlement calculus.

Last year, before the Phoenix verdict, a California jury found Uber not liable for a sexual assault that a plaintiff alleged her driver committed in 2016. That verdict suggested California juries might be more skeptical of holding Uber responsible for independent contractor misconduct. But that was a single case, and jury composition varies dramatically. The California verdict provided some defense optimism, but the Phoenix verdict inverts the script.

Uber now faces a two-front war. Federal litigation in Arizona proceeds with a bellwether verdict establishing precedent. California litigation proceeds with at least one jury verdict favoring Uber, but now facing the new reality of the Phoenix verdict. Settlement negotiations in California will likely reference the $8.5 million Phoenix award, putting pressure on Uber to settle California cases at comparable levels.

The geographic separation also creates strategic issues for Uber's defense. The company needs consistent messaging across jurisdictions, but different judges and juries may respond differently to the same arguments. California courts may interpret contractor liability differently than Arizona federal courts. Uber's legal team faces the nightmare scenario: defending cases in multiple jurisdictions simultaneously while each jurisdiction's outcomes influence the others.

Passengers in California considering Uber litigation now have stronger leverage. They can point to the Phoenix verdict and argue their cases deserve similar compensation. The state court lawsuits, while geographically separate, now exist in the shadow of federal court precedent. That changes settlement conversations immediately.

What the Jury Decision Actually Means Legally

The jury's verdict contains a crucial contradiction that legal experts are still parsing. The jury found Uber liable for the driver's alleged misconduct but determined the company wasn't negligent regarding its safety practices. How can a company be liable for something without being negligent about it?

The answer lies in legal theory about agency and vicarious liability. Vicarious liability means one party is responsible for another party's conduct based on their relationship, not based on the first party's own negligence. If your employer hires a driver and that driver causes an accident, your company might be vicariously liable for the accident even if the company exercised reasonable care in hiring and training.

The jury appears to have applied similar logic. They decided the Uber driver was acting as Uber's agent when the alleged assault occurred. By that theory, Uber is vicariously liable. The company didn't need to be negligent in its safety practices (the jury found it wasn't) because liability flows from the agency relationship, not from faulty systems.

This distinction matters enormously on appeal. Uber's attorneys will argue the jury misunderstood vicarious liability. They'll contend that independent contractors can't create vicarious liability for platforms. The legal battle will focus on whether a contractor can be an agent in the agency sense that creates vicarious liability.

If the verdict survives this challenge, it fundamentally changes platform liability. Companies could be held responsible for contractor conduct even if they exercise reasonable care. That expands liability far beyond what companies anticipated when they adopted contractor models.

If the verdict is overturned on appeal, the entire precedent collapses. Thousands of pending cases would see their legal theory rejected. Settlements might decrease. The gig economy platform model would receive appellate validation.

The courts haven't fully resolved these questions yet. This is an emerging area of law where judges and juries are grappling with novel questions about platform liability that didn't exist before the gig economy exploded. The Dean case is one test. Others will follow. Eventually, either the Supreme Court or appellate courts will provide clearer guidance.

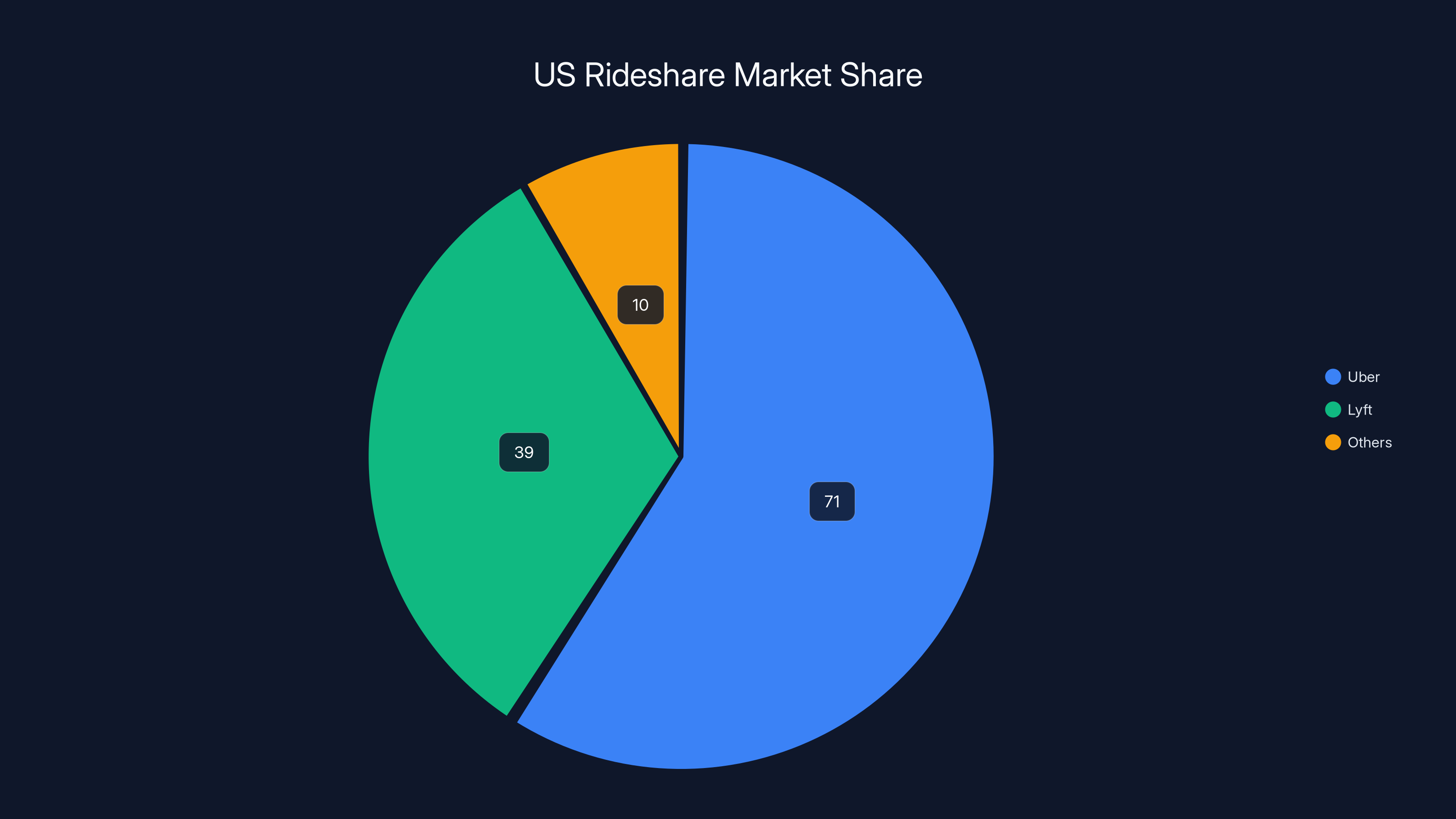

Uber holds a dominant 71% of the US rideshare market, while Lyft has 39%. 'Others' account for the remaining 10%. Estimated data.

The Safety Camera Question: Deliberate Choice or Corporate Prudence?

One of the most striking revelations from the trial was the question of in-car cameras. Dean's lawyers presented evidence suggesting Uber had consciously resisted implementing in-car cameras that could record interactions between drivers and passengers, supposedly because the cameras would slow growth.

This allegation cuts to the heart of corporate incentives. From a safety perspective, in-car cameras seem like an obvious tool. They'd create accountability for both drivers and passengers. They'd provide evidence in cases of assault, harassment, or other misconduct. They'd deter bad behavior by increasing the likelihood of consequences. Modern cameras are small, inexpensive, and technically straightforward to implement.

But from a growth perspective, in-car cameras present a different calculation. A new driver considering joining Uber might hesitate if they knew their every interaction was recorded. Passengers might feel their privacy was invaded by cameras recording them in moments of vulnerability. If either party felt uncomfortable with constant recording, Uber's growth could suffer. Each percentage-point decline in new driver or passenger adoption has massive financial implications for Uber's valuation and revenue.

The jury heard that internal documents suggested Uber prioritized growth over implementing cameras. That's a corporate ethics issue with legal implications. If Uber knowingly chose to forego a safety measure that would prevent harm, specifically to maximize growth, that transforms the calculus of responsibility. The company didn't accidentally overlook cameras. The company allegedly made a deliberate choice.

This feeds directly into the negligence analysis. Even if the jury found Uber wasn't negligent in its safety practices overall, the deliberate choice to avoid a safety tool despite knowing it could prevent harm might constitute negligence in a different context. Future plaintiffs' lawyers will reference this evidence when arguing Uber should have implemented cameras.

Post-verdict, Uber announced plans to invest in in-car camera technology, but only in certain markets where state laws permit it. This announcement looks responsive to jury findings. It also raises the question: if cameras are so important that Uber will implement them now, why didn't Uber implement them earlier? The company's own actions suggest cameras provide genuine safety value.

The in-camera question also extends to other potential safety measures. How many other technologies exists that Uber hasn't implemented because of growth considerations? How many risk-mitigation strategies has the company rejected based on cost-benefit analysis? If internal documents show Uber systematically chooses growth over safety when the two conflict, that establishes a pattern relevant to liability questions.

Future cases will likely explore this question more deeply. Uber's decision to implement cameras now, post-verdict, might actually be used against the company. Plaintiffs' lawyers will argue: "Uber admits cameras make rides safer. They admit cameras prevent assault. They just didn't want to implement them before because growth mattered more." That's a powerful narrative.

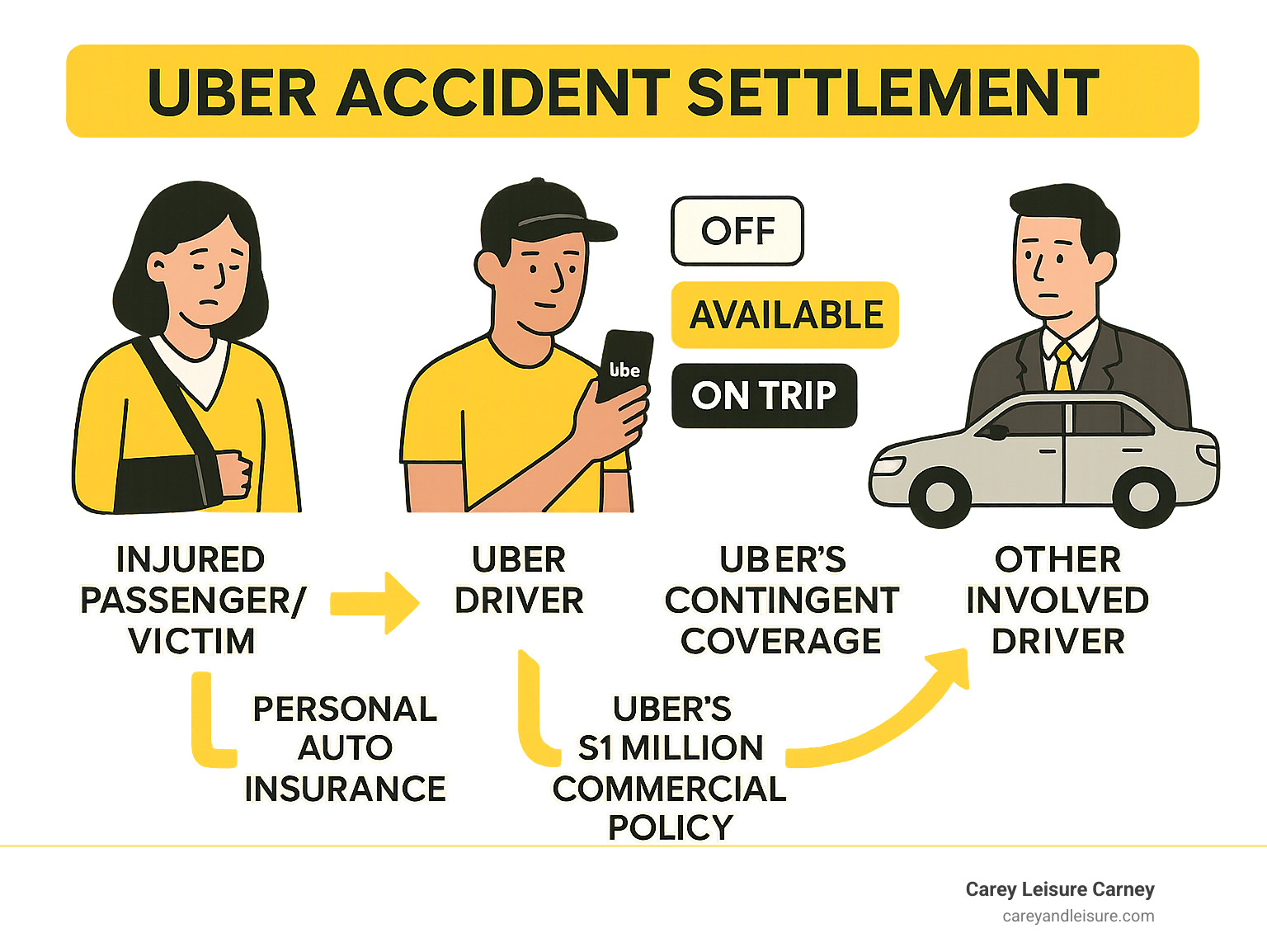

Insurance, Corporate Liability, and the Financial Reality

When a company faces a jury verdict of $8.5 million, the financial impact depends partly on whether insurance covers it. Uber, like most large corporations, maintains liability insurance that covers certain types of harm and misconduct. If insurance covers sexual assault liability, the insurance company pays (up to policy limits), not Uber directly.

But here's where the verdict becomes significant even if insurance covers it: the verdict affects future insurance costs. When Uber renews its policies or obtains new coverage, insurance companies will factor in the $8.5 million verdict and the thousands of pending cases. Insurance premiums will increase. Deductibles may rise. Coverage limits may be reduced. The total cost of risk transfer increases.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, jury verdicts affect settlement negotiations for all pending and future cases. When insurance adjusters evaluate liability for the remaining 3,500 federal cases, they use bellwether verdicts as benchmarks. If juries award $8.5 million in one case, adjusters assume they might award similar amounts in similar cases. That increases the insurer's expected payout across all cases.

From an insurer's perspective, it becomes rational to push Uber toward settlement at higher amounts to avoid the risk of multiple jury verdicts. The insurance company's expected value calculation changes. Settling ten cases at

Third, the verdict creates reputational damage that financial metrics don't fully capture. Uber's brand is built on reliability and safety. Headlines reading "Jury Finds Uber Liable for Driver's Rape" damage the brand. Investors worry about further verdicts. Customer acquisition costs might increase as safety concerns deter new users. The financial impact extends beyond the $8.5 million verdict itself.

Uber's stock price fluctuates based on multiple factors, but major litigation outcomes affect investor confidence. A single verdict is manageable. But if 3,500 cases proceed toward similar verdicts, that's existentially different. Investors will demand management address the liability exposure, either through massive settlements or fundamental business model changes.

This financial pressure is often what drives corporate policy changes. Not jury verdicts alone, but the financial implications of jury verdicts. Uber will implement in-car cameras partly because of the verdict, but mostly because the verdict makes the financial case for cameras undeniable.

The majority of pending legal cases against Uber are federal, with over 3,500 cases compared to 500 state cases. Estimated data.

What This Means for Passenger Safety Going Forward

The Dean verdict will likely force concrete safety changes at Uber. The company announced plans to expand in-car camera availability. It will likely invest in improved risk-assessment tools. Background checks may become more rigorous. Training for drivers may expand. These changes represent the verdict's most tangible impact.

But beyond Uber-specific changes, the verdict establishes a legal framework that could affect the entire rideshare industry. Lyft, Door Dash, and other platforms will watch closely as the case proceeds through appeals. If courts affirm that platforms can be held liable for contractor misconduct despite contractor classification, other platforms face similar exposure.

That creates industry-wide pressure to improve safety measures. Platforms that had resisted investing in safety may decide investment now makes financial sense. The cost of litigation becomes higher than the cost of prevention. That's a perverse way to incentivize safety, but it works. When lawsuits become expensive enough, companies address the underlying problems.

The verdict also empowers passengers. Knowing that at least one jury held a platform liable for driver misconduct means future plaintiffs' cases aren't fighting an established precedent that platforms bear no responsibility. The legal landscape has shifted. Passengers have stronger cases, which gives them stronger leverage in settlement negotiations.

For individual passengers using these services, the immediate impact is modest. Uber's app will likely gain more safety features. Communication may improve about high-risk rides. In-car cameras will be available in more markets. These are incremental changes. But they're real changes driven by the verdict's financial pressure.

The deeper change involves how platforms think about their responsibility. For years, Uber could argue it was merely a technology platform connecting independent parties. The company bore no responsibility for what happened between drivers and passengers because those were separate individuals engaging in a private transaction.

The Dean verdict challenges that framing. The jury decided that even though the driver and passenger were separate parties, Uber's platform, systems, and knowledge connected them in a way that created corporate responsibility. The company couldn't distance itself from the interaction. That conceptual shift will ripple through litigation and corporate policy for years.

Appeals, Legal Precedent, and the Path Forward

Uber's announcement that it plans to appeal the verdict is standard litigation practice. Almost all large verdicts are appealed. The appeal process involves reviewing whether the trial judge made legal errors, whether jury instructions were proper, and whether the verdict is supported by evidence. Appeals can take years. The original verdict won't be final until appellate courts weigh in.

Uber's strongest appeal argument likely focuses on the agency and contractor liability questions. The company will argue the jury misunderstood the law of vicarious liability. Independent contractors, by definition, aren't agents of the platform. Therefore, Uber can't be vicariously liable for the driver's conduct. This is a pure legal question, not a factual one, so appellate courts can review it without deferring to the jury.

But appellate courts also apply a high bar for overturning jury verdicts. Juries get considerable deference about factual findings. If evidence supports that the driver was acting as Uber's agent, appellate courts may affirm even if they would have reached a different legal conclusion. The appeal isn't won just because Uber has a plausible legal argument.

If the verdict survives the first appeal, Uber could appeal further to higher courts, potentially reaching a state supreme court or, in some theories, federal court. But each appeal level narrows the scope of review. Once a jury verdict is affirmed on appeal, it becomes extremely difficult to overturn on further appeals.

The verdict's precedential value is already significant, even before appeals conclude. Future plaintiffs' lawyers will reference the Dean case when litigating similar allegations. Trial judges will reference it when ruling on motions and jury instructions. Settlement negotiators will use it as a benchmark. Appeals take years, but the verdict influences behavior immediately.

Eventually, appellate courts will likely need to clarify the law of platform liability. Are contractors agents in the legal sense that creates vicarious liability? Can platforms be held responsible for misconduct despite contractor classification? How do companies balance safety investment with business model incentives? These are the fundamental questions the Dean case raises.

The legal answers to these questions will shape the gig economy's future. They'll influence how platforms operate, what safety measures they implement, and how much liability they accept. They'll determine whether the independent contractor model survives intact or evolves into something that incorporates greater corporate responsibility.

Industry Impact and Implications for Other Platforms

Uber didn't create the gig economy, but the company perfected the model. Uber built a business where independent contractors provide services coordinated through a platform, with the company taking a percentage of each transaction while disclaiming responsibility for worker conduct. That model has been copied by Door Dash, Lyft, Instacart, Task Rabbit, and countless other platforms.

The Dean verdict creates pressure on all these companies. If platforms can be held liable for contractor misconduct, contractor models become more expensive. The financial benefit of contractor classification decreases. Companies may need to either invest dramatically in safety measures to reduce liability or reclassify workers as employees.

Some companies may migrate toward employee classification, especially if litigation costs rise significantly. Others may double down on safety investment to reduce the underlying risk. Either path increases costs, which get passed to consumers through higher prices or reduced service quality.

Food delivery platforms like Door Dash face similar questions about responsibility for driver conduct. Ride-sharing competitors like Lyft face identical legal frameworks. Even companies like Fiverr, where freelancers provide services through a platform, could face similar arguments about platform responsibility.

The verdict also creates precedent for other types of contractor misconduct, not just sexual assault. If platforms can be held liable for violent crime, can they also be held liable for fraud, theft, property damage, or harassment by contractors? The legal principles extend beyond sexual assault to any contractor misconduct that harms the other party in the transaction.

Large platforms with resources will likely invest in safety infrastructure, legal compliance, and risk mitigation. Smaller platforms may struggle with the cost and complexity. This could create a market dynamic where safety liability becomes a competitive advantage for well-resourced companies. It could also push smaller platforms out of business if liability exposure becomes unmanageable.

The gig economy as a concept won't disappear. Platforms connecting contractors with customers will continue to exist. But the legal framework governing platform liability is evolving. The Dean case is a major data point in that evolution. Future business models will incorporate these legal realities.

Passenger Vulnerability and the Role of Intoxication

Jaylynn Dean's intoxication at the time of her ride is relevant to the case in complicated ways. Intoxication didn't cause the alleged assault, and it certainly doesn't suggest the passenger was responsible for what happened. But intoxication does increase vulnerability. Intoxicated passengers have reduced situational awareness, impaired judgment, and less capacity to resist or escape dangerous situations.

Uber's machine-learning risk assessment tool allegedly flagged Dean as high-risk partly because of her intoxication status. The algorithm identified that an intoxicated passenger had elevated danger risk on that particular ride. The system worked. The algorithm correctly identified an elevated-risk situation.

But Uber didn't communicate this information to Dean. She didn't know the system had identified her as high-risk. She couldn't take additional precautions like waiting for a different driver or choosing a different route. The information existed in Uber's systems but wasn't shared with the person most affected by the risk.

This raises broader questions about when and how platforms should communicate risk information. If Uber's system identifies a high-risk ride, does the company have an obligation to warn the passenger? Does warning the passenger create liability if the passenger is then harmed despite the warning? These are new questions without established legal answers.

The intoxication also relates to informed consent. Passengers might have different expectations about safety if they knew they were riding while intoxicated, or if they knew the app had flagged them as high-risk. Transparency about risk assessment could allow passengers to make different choices. But providing such transparency might also encourage passengers to decline rides they otherwise would have accepted, reducing platform revenue.

Future cases will likely focus more on how platforms communicate risk to passengers. This could become a key competitive differentiator. Platforms that proactively warn passengers about potential risks might reduce liability while earning passenger trust. Platforms that withhold risk information while possessing it become litigation targets.

The vulnerable passenger angle also resonates with juries. Passengers who use rideshare services are often in vulnerable situations: intoxicated, traveling alone, in unfamiliar areas, or with mobility limitations. The jury likely sympathized with a passenger in a vulnerable state who was unaware the platform had assessed her as high-risk. That human element matters in jury deliberations.

Comparative Industry Responses and Competitive Pressure

Uber isn't the only rideshare company, and the Dean verdict creates competitive pressure for safety measures. Lyft, the primary competitor, could use this opportunity to differentiate itself as a safer alternative. If Lyft invests in better safety features than Uber, the company gains marketing advantage.

Lyft has approximately 39% of the US rideshare market compared to Uber's 71% market share. Lyft is smaller and has less financial resources than Uber. But the Dean verdict creates an opportunity for Lyft to make safety a competitive advantage. Marketing messaging along the lines of "Lyft prioritizes your safety more than Uber" could resonate with passengers concerned about assault risk.

In international markets, rideshare safety is an even bigger issue. In India, sexual assault by Uber and Lyft drivers has generated intense media coverage and regulatory scrutiny. Those markets are particularly alert to platform safety. A verdict like the Dean case has amplified impact in regions where rideshare safety is politically sensitive.

Uber's response will likely involve substantial safety investment, transparency improvements, and perhaps business model adjustments in certain markets. The company can't afford to be perceived as cavalier about passenger safety when jury verdicts and regulatory scrutiny are converging.

Lyft could gain market share if the company positions itself as the safer option. That would create a virtuous cycle where focus on safety generates competitive advantage, which justifies further safety investment, which generates more competitive advantage. Whether Lyft actually captures this opportunity depends on effective marketing and implementation.

The competitive dynamic also affects driver quality. If Lyft becomes known as more selective about drivers and more protective of passenger safety, higher-quality drivers might prefer Lyft. That improves Lyft's service quality and safety profile. The reverse could happen with Uber if the company is perceived as prioritizing growth over safety.

Looking Ahead: What's Next in This Saga

The Dean case is far from over. Multiple years of appellate review likely await. But the immediate next steps involve settlement negotiations for the 3,500+ pending federal cases and 500+ pending state cases. Plaintiffs' lawyers will reference the $8.5 million verdict heavily. Insurance adjusters will factor it into liability calculations. Settlement offers will likely be higher than they would have been pre-verdict.

Uber will continue litigating some cases while settling others. The company will likely pursue a mixed strategy: appeal the Dean verdict aggressively to avoid precedent while simultaneously settling cases where the evidence is weak for Uber or where settlement is cheaper than trial. That's standard practice in mass litigation.

The next major milestone will be appellate decisions. If appellate courts affirm the verdict, it becomes binding precedent that affects all subsequent cases. If appellate courts overturn it, the legal theory collapses and Uber gains significant leverage in remaining cases. The appellate process will likely take 2-3 years minimum.

Regulatory attention could accelerate policy changes. State attorneys general, city transportation authorities, and federal regulators might use the Dean verdict as justification for stricter safety requirements. A few states have already passed laws requiring rideshare companies to improve safety features. The Dean case provides political cover for further regulation.

Social media and public opinion will continue to shape the narrative. Stories about the Dean verdict will be shared widely, associating Uber with sexual assault liability. That reputational damage will persist regardless of how appeals ultimately resolve. Future passengers will remember that a jury found Uber liable for a driver's alleged rape.

Uber itself may undergo strategic shifts in response to this verdict. The company might invest more in safety, implement more rigorous driver screening, offer in-car cameras as standard features, or improve risk communication to passengers. These are changes litigation essentially forces the company to make.

The broader legal system will struggle with the questions this case raises. Can platforms be held liable for contractor misconduct? What legal principles govern the gig economy? How do we balance contractor freedom with consumer protection? These questions will work through courts for years, likely reaching appellate courts and potentially state supreme courts. They might eventually need Supreme Court resolution if different courts reach different conclusions.

For passengers, the verdict represents a small victory even if it's not fully final. It establishes that at least one jury believes platforms bear responsibility for creating safe environments. It suggests future lawsuits have better legal foundations than they might have pre-verdict. It validates the experiences of assault survivors who questioned whether platforms cared about their safety.

For Uber, the verdict represents a significant challenge. The company faces massive litigation exposure, reputational damage, and potential business model constraints. The independent contractor model that worked brilliantly for years is now legally questionable. The company will need to invest in safety, accept greater liability, or negotiate its way through thousands of lawsuits.

For the gig economy writ large, the verdict signals that the wild west of contractor platforms is ending. Regulatory oversight, legal liability, and safety investment will constrain how these businesses operate. That doesn't mean the gig economy will disappear, but it will look different in the future.

Key Takeaways and Practical Implications

The Uber verdict matters for several concrete reasons. First, it establishes that juries will hold platforms liable for contractor misconduct under certain circumstances. That changes the calculus for future cases. Plaintiffs' lawyers have stronger legal foundations. Defendants face higher litigation costs.

Second, the verdict forces business model reconsideration. If contractor classification doesn't shield platforms from liability, the model becomes more expensive. Companies will need to invest in safety, accept greater risk, or potentially reclassify workers. That affects costs, which eventually affect consumers.

Third, the verdict impacts passenger safety directly. Uber will almost certainly implement more rigorous safety measures, better risk communication, and possibly in-car cameras. Similar pressure will apply to competitors. Passengers benefit from these improvements.

Fourth, the verdict creates market disruption. Smaller platforms might struggle with litigation costs. Larger platforms with resources will adapt. The competitive landscape will shift. Investors will demand safety-oriented business models. The industry will consolidate around companies that can manage liability effectively.

Fifth, the verdict raises broader questions about corporate responsibility. Companies can't simply disclaim responsibility for harms caused by people they facilitate interacting through their platforms. That principle extends beyond rideshare to any platform that connects users. It potentially affects social media companies, gig platforms, and any business model based on connecting parties.

For passengers reading this, the immediate practical advice is simple: use available safety features. Share your location. Verify driver details match the vehicle. Communicate your estimated arrival time to friends. If something feels wrong before or during a ride, cancel. Trust your instincts.

For employees or contractors considering rideshare work, understand that the legal landscape is evolving. Safety standards, background checks, and liability frameworks are changing. Research companies' safety practices before signing up. Understand that better safety standards likely mean more work for drivers (training, monitoring), but also mean platforms taking responsibility for safety.

For investors and business leaders, the verdict signals that the assumption of contractor immunity is now challenged. Future business models need to account for potential liability even with contractor classification. That means safety investment becomes a core business expense, not a discretionary cost-control measure.

For regulators and policymakers, the verdict provides evidence that existing frameworks may not adequately protect vulnerable passengers. Additional regulation, safety standards, and liability frameworks may be needed. The verdict won't determine what policymakers do, but it will influence regulatory conversations.

FAQ

What happened in the Uber case that resulted in the $8.5 million verdict?

A federal jury in Phoenix found Uber liable for a passenger named Jaylynn Dean, who alleged that an Uber driver raped her in 2023. Dean had ordered a ride after celebrating passing her flight attendant exam while intoxicated. The driver allegedly diverted to a dark parking lot and assaulted her. Uber had flagged Dean as high-risk for safety incidents before her ride, but didn't notify her. The jury determined that despite the driver being an independent contractor, he was acting as an Uber agent when the alleged assault occurred, making the company liable.

Why is this case considered a bellwether trial?

A bellwether trial is a representative case selected from hundreds of similar lawsuits to test legal theories and gauge likely outcomes. The Dean case was chosen from approximately 3,500 sexual assault allegations against Uber consolidated in federal court. The jury verdict in Dean's case establishes precedent that influences how the remaining cases will likely be resolved, what settlements will be offered, and whether juries believe platforms can be held liable for contractor misconduct. If upheld on appeal, the verdict could become the baseline for thousands of other cases.

How did Uber argue it wasn't responsible for the driver's actions?

Uber's core defense was that it's a technology platform connecting independent contractors with passengers. Since drivers are independent contractors, not employees, Uber argued it bears no responsibility for what contractors do. The company presented evidence that it conducted background checks, trained drivers, and implemented safety features like passenger feedback ratings. Uber also argued that the specific driver had no criminal history and had received excellent ratings from previous passengers. However, the jury rejected this argument by finding that even though the driver was an independent contractor, he was functioning as an agent of Uber when the alleged crime occurred.

What does "finding Uber liable but not negligent" actually mean?

This seeming contradiction reflects two different legal theories. Vicarious liability means one party is responsible for another party's conduct based on their relationship (like employer-employee relationships), regardless of whether the first party was negligent. The jury found Uber vicariously liable because the driver was acting as Uber's agent. However, the jury also determined that Uber's actual safety practices weren't negligent. Uber wasn't wrong in how it hired or trained this particular driver. This distinction matters because it suggests Uber could still be held responsible for future incidents even if the company exercises reasonable care in its practices.

How many other cases like this is Uber facing?

Uber is facing approximately 3,500 consolidated sexual assault and misconduct allegations in federal court in Phoenix, overseen by Judge Dominic Lanza. Additionally, the company faces about 500 similar cases in California state courts. These cases allege incidents spanning from 2010 to 2024, with allegations including sexual assault, harassment, kidnapping, and other forms of misconduct. The Dean case is just one test case, but the verdict's outcome influences expectations and settlement negotiations for all the remaining cases.

Will the $8.5 million verdict definitely stand, or could it be overturned?

Uber announced it plans to appeal the verdict, which is standard practice for large jury awards. The appellate process involves reviewing whether the trial judge made legal errors and whether the verdict is supported by evidence. Uber's strongest argument likely focuses on the independent contractor classification: the company will argue that contractors can't be agents of the platform in a legal sense that creates vicarious liability. However, appellate courts give significant deference to jury verdicts on factual findings. If evidence supported that the driver was acting as Uber's agent, the verdict could survive appeal. The appellate process typically takes several years. The verdict influences behavior and settlement negotiations immediately, even while appeals proceed.

What safety changes might Uber implement in response to this verdict?

Uber has announced plans to expand in-car camera availability in certain markets where state law permits recording. The company will likely invest in improved risk-assessment technology, more rigorous background checks, enhanced driver training, and better communication about safety features. The jury's finding that Uber possessed high-risk information but didn't communicate it to Dean suggests Uber will likely implement notifications when the algorithm flags riders or drivers as high-risk. These changes will increase Uber's operational costs but could reduce liability exposure. Whether Uber invests aggressively or minimally while appealing the verdict remains to be seen.

How might this affect other rideshare companies like Lyft?

The verdict creates competitive pressure for all rideshare platforms. If Lyft positions itself as having superior safety practices or commits to in-car cameras and better risk communication, the company could gain market share from Uber. However, the verdict could also create liability exposure for Lyft if the company faces similar allegations. Other platforms will likely accelerate safety investments to reduce legal risk. The verdict establishes that juries will consider holding platforms liable for contractor misconduct, which changes the risk calculation for all gig economy companies. Platforms that invest in safety early may gain competitive advantage over those that wait for their own litigation disasters.

What does this verdict mean for the independent contractor model that most gig economy companies use?

The verdict challenges the assumption that independent contractor classification shields platforms from liability for contractor misconduct. If contractors can be agents of the platform in situations that create vicarious liability, contractor classification becomes less protective. This doesn't mean contractor models will disappear, but companies will need to invest more in safety, accept greater liability, or possibly reclassify some workers as employees. The contractor model's cost advantage diminishes if platforms remain liable for contractor conduct. Future gig economy business models may incorporate greater platform responsibility and higher safety investment costs, which could be passed to consumers through higher prices or reduced service quality.

What should passengers do to stay safer while using rideshare services?

Passengers should use available app safety features like real-time location sharing and trip notification options. Before accepting a ride, verify the driver's photo, vehicle details, and license plate match what the app displays. Share your trip details and real-time location with a trusted friend or family member. If anything feels wrong before or during a ride, cancel immediately and request a different driver. Avoid sharing your home address for pickup if you're riding alone; instead, choose a public, well-lit location. Trust your instincts about driver behavior. Document any incidents with screenshots and written descriptions. Intoxicated passengers should ask friends or family members to track their trip or consider alternative transportation like designated drivers or taxis.

How could this verdict affect consumer costs or service availability?

If platforms must invest significantly in safety measures and accept greater liability, operational costs increase. These costs could be passed to consumers through higher per-ride fees. Alternatively, platforms might reduce driver compensation or limit service in markets where liability is highest. However, increased safety investment could also justify premium pricing that safety-conscious consumers are willing to pay. Some smaller platforms might exit certain markets if liability costs become unsustainable. The long-term effect depends on how much liability exposure materializes and how platforms choose to manage costs. Uber's size and resources give it advantages in absorbing liability costs that smaller competitors might not have.

The Uber verdict represents a genuine turning point in how courts and the public understand platform responsibility. For years, companies built billion-dollar businesses on the assumption that they could facilitate transactions while disclaiming responsibility for what happened through their platforms. The Dean verdict challenges that assumption in a way that could reshape the entire gig economy. Whether Uber's appeal succeeds or fails, the landscape has already shifted. Passengers know they have legal recourse. Platforms understand they can't hide behind contractor classification. And the legal system has begun grappling with hard questions about what responsibility platforms owe to the people who use them. That conversation, once started, will continue for years. The ripple effects of this single $8.5 million verdict will reverberate through courts, boardrooms, and regulatory agencies across the country.

Related Articles

- Uber Liable for Sexual Assault: What the $8.5M Verdict Means [2025]

- The SCAM Act Explained: How Congress Plans to Hold Big Tech Accountable for Fraudulent Ads [2025]

- Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What We Know [2025]

- Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What Happened & Safety Implications [2025]

- AI Drafting Government Safety Rules: Why It's Dangerous [2025]

- NTSB Investigates Waymo Robotaxis Illegally Passing School Buses [2025]

![Uber's $8.5M Settlement: What the Legal Victory Means for Rideshare Safety [2024]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uber-s-8-5m-settlement-what-the-legal-victory-means-for-ride/image-1-1770388668067.jpg)