Social Companion Robots and Loneliness: The Promise vs Reality [2025]

TL; DR

- Social robots promise companionship: Devices like Mirumi are designed to help combat loneliness, particularly in aging populations facing isolation.

- The science has merit: Studies show robotic pets can enhance well-being during lockdowns, but results vary widely based on context and expectations.

- Reality is messier than marketing: Most users find the robots cute but ultimately boring, with limited real emotional engagement.

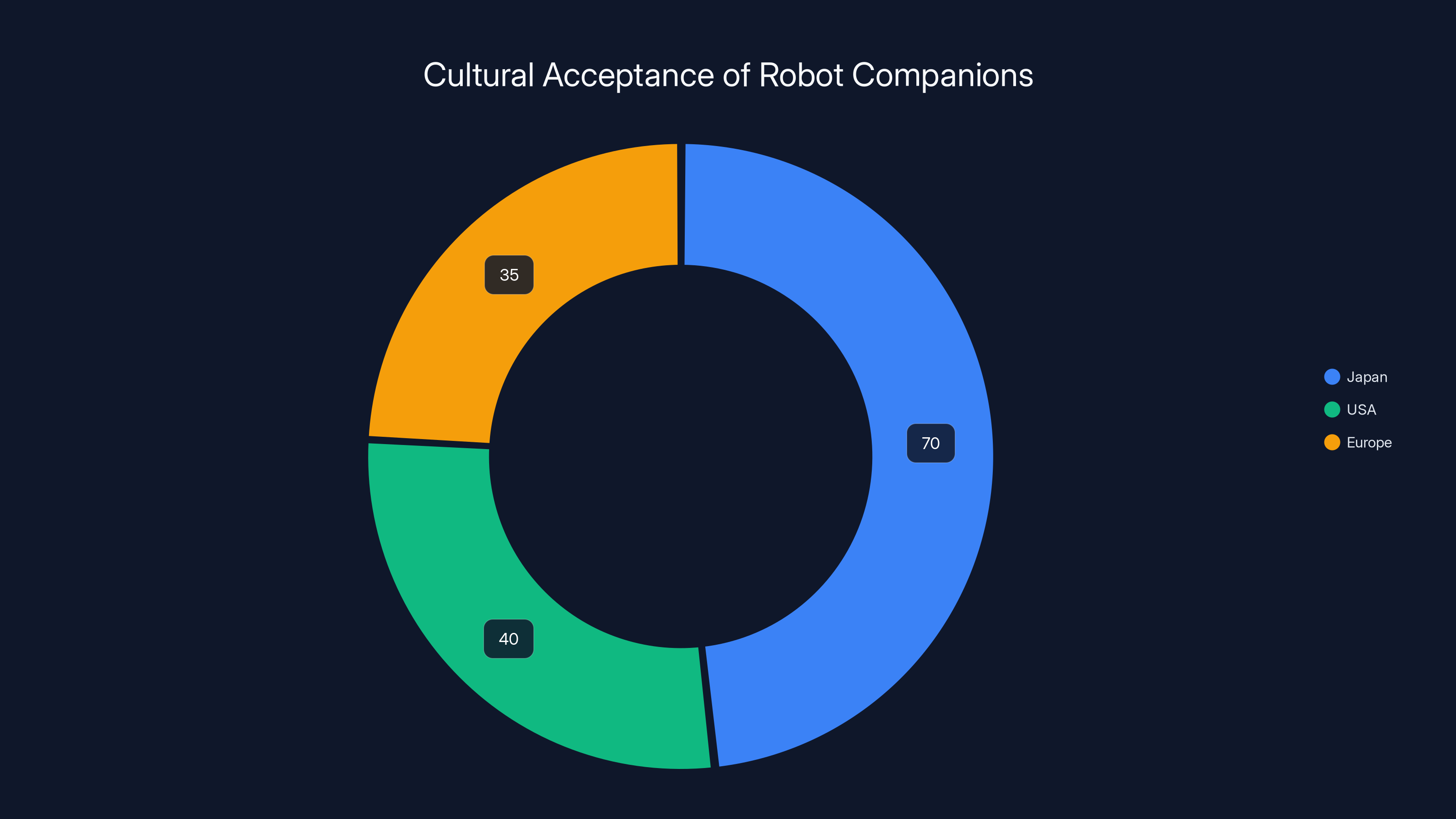

- Cultural gap matters: Japan's robot-friendly culture sees different adoption than Western skepticism, rooted in different philosophical approaches to technology.

- Bottom line: These robots work best as supplementary tools, not replacements for human connection or proper mental health care.

Unboxing a cute robot feels like time travel.

When Mirumi arrives, it's nestled in packaging that looks more like a shopping bag than a tech product. Pull it out and you're holding something genuinely soft. Fluffy pink exterior, an owlish face with googly eyes that catch light perfectly, and weirdly strong slothlike arms. It's the kind of thing that makes you smile without thinking about it.

But here's the thing: that smile fades faster than you'd expect.

I've spent the last six weeks living with Mirumi, watching it interact with my daily life, and learning exactly why the promise of cute robots falls short of reality. This isn't a story about whether robots are good or bad. It's about the gap between what we hope technology can do for us and what it actually delivers.

The loneliness crisis is real. According to CDC research, chronic loneliness is linked to serious health outcomes including increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and dementia. In Japan, where Mirumi comes from, the problem is even more acute. An aging population combined with declining birth rates creates a perfect storm: fewer young people to care for elderly relatives, more seniors living alone, and cultural shifts that have disrupted traditional multigenerational household structures.

Enter the social robot. Companies like Yukai Engineering position these devices as part of the solution. They're not meant to replace human connection. At least, that's what the marketing says. They're supposed to fill gaps, provide comfort, maybe even encourage social interaction. In theory, a cute robot that responds to your presence and mimics shy infant behavior could serve as a low-stakes social object. Something to care for. Something that cares back, in its limited way.

The reality is messier. And that's actually the interesting part.

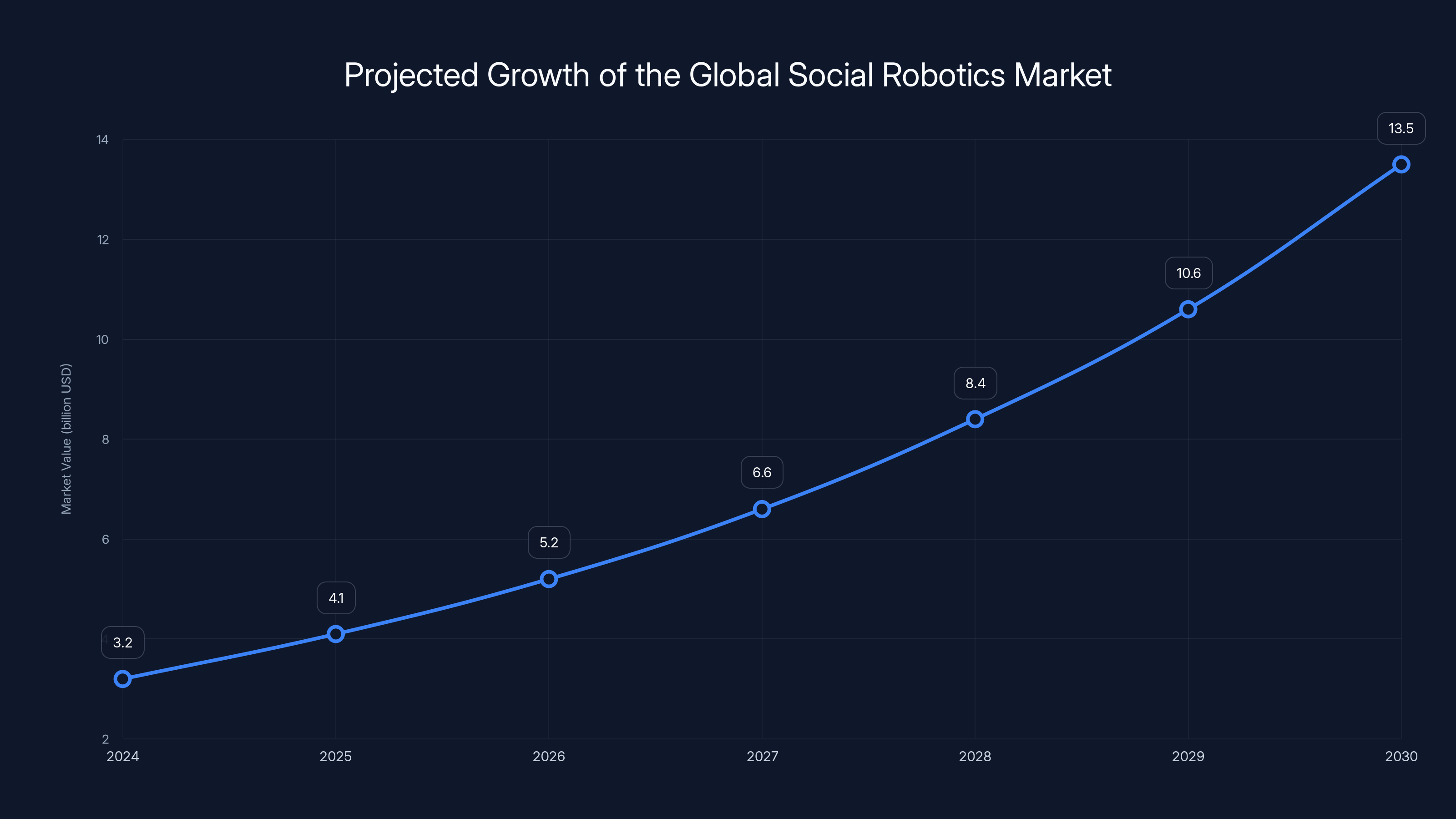

The global social robotics market is projected to grow significantly from

The History of Japanese Robot Philosophy

To understand why Mirumi exists at all, you need to understand something fundamental about how Japan approaches robots differently than the West.

Back in 2011, when the Great East Japan Earthquake struck, the world watched as robots were deployed to handle the impossible. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster required machines that could venture into dangerously radioactive zones where humans would face lethal exposure. But Japan didn't deploy their own advanced robotics. Instead, they relied on the i Robot Pack Bot, an American-made machine designed for military reconnaissance.

This created an interesting cultural moment. Japan, famous as a robotics powerhouse, outsourced the dangerous work to American technology. Why? Because Japanese robot development had taken a fundamentally different path.

In Japan, robots were envisioned as friends, not workers. This philosophical difference matters more than you'd think. While Western robotics development focused on automation and replacing human labor—think industrial arms and warehouse robots—Japanese companies invested in machines that could provide companionship and emotional support.

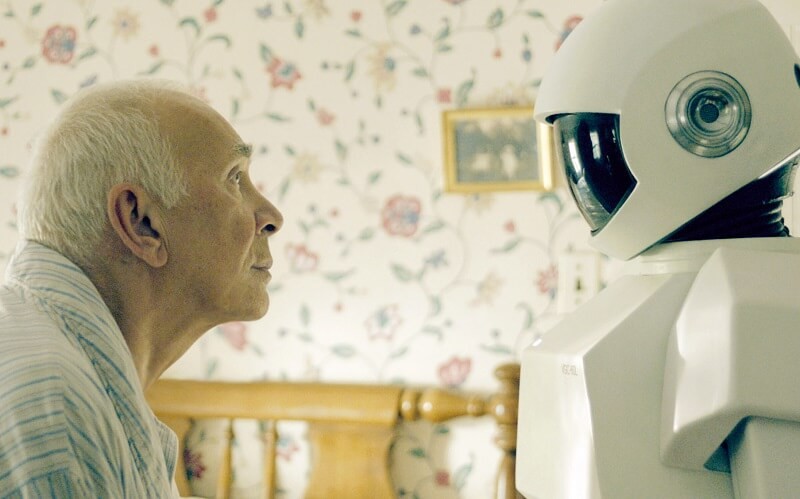

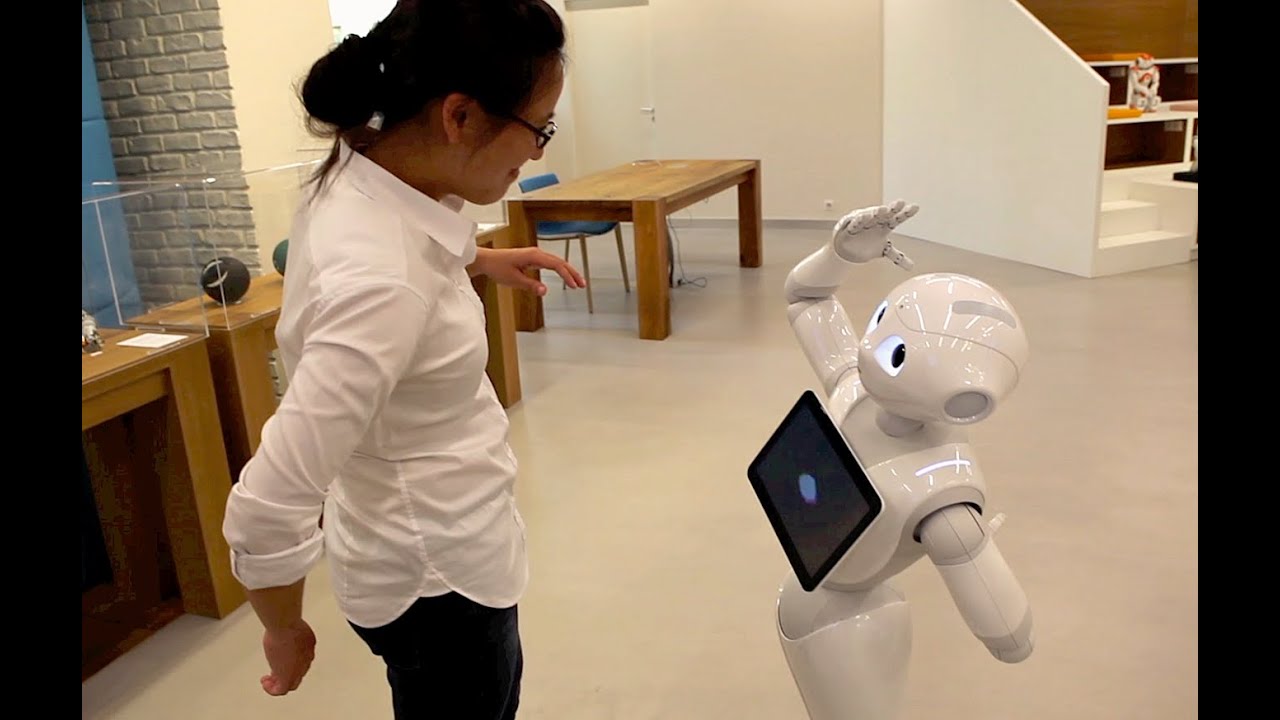

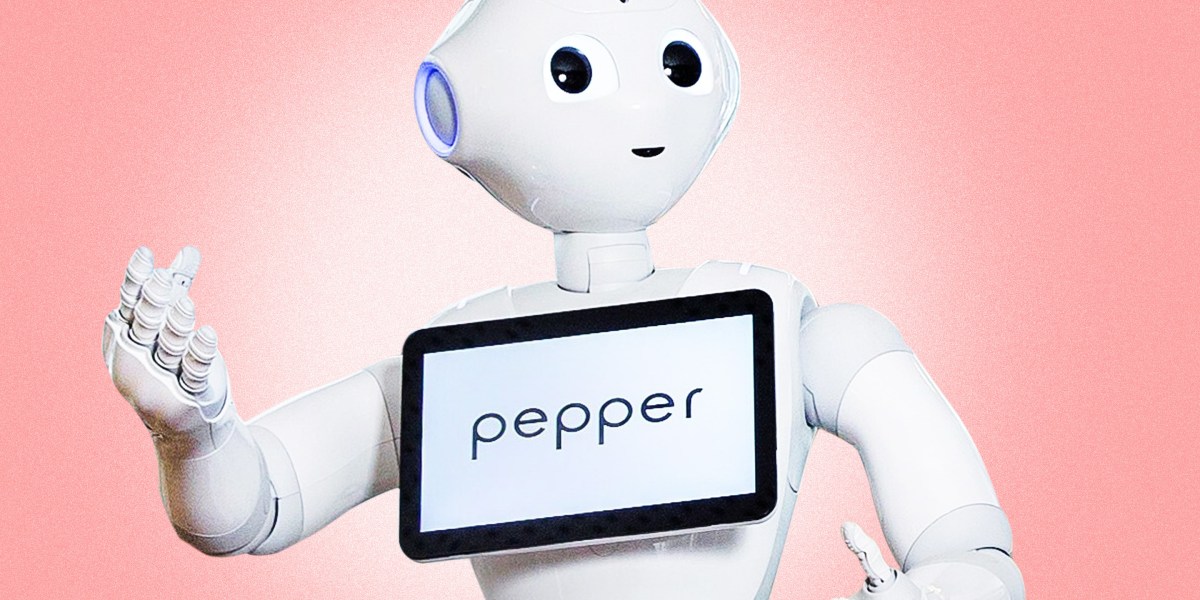

Paro the robot seal is the classic example. Launched in 1993, this fuzzy white robot was designed to soothe loneliness among elderly and dementia patients. It makes sounds like a real seal, responds to touch, and displays behaviors that encourage interaction. Paro actually works. Studies show it improves mood and engagement in care facilities. The robot's success validated an entire category: cute robots as therapeutic tools.

Then came Honda's ASIMO, the humanoid robot that became iconic in the early 2000s. ASIMO was adorable by design. It walked upright, responded to commands, and embodied the dream of a personal robot helper. But ASIMO was expensive, complex, and honestly? Not that practical. Eventually Honda retired ASIMO and folded its technology into more practical applications like nursing robots and transportation systems.

What this history reveals is a cultural commitment to the idea that robots can be benevolent companions. That they don't have to be cold, utilitarian machines. This philosophy is deeply embedded in Japanese culture, from Shinto concepts of animism—the belief that objects can have spirits—to manga and anime that portray robots as potential friends rather than threats.

Mirumi inherits this philosophy. It's designed to mimic a shy infant, which is a specific choice. Infants are universally appealing, vulnerable, and elicit caregiving instincts. By making a robot that behaves like a shy baby, Yukai Engineering is tapping into deep human psychology. When Mirumi peeks at you and then ducks away, your brain registers this as shyness. Your instinct is to be gentle, to approach slowly, to coax it out of its shell. It's a clever design choice.

But cleverness and effectiveness aren't the same thing.

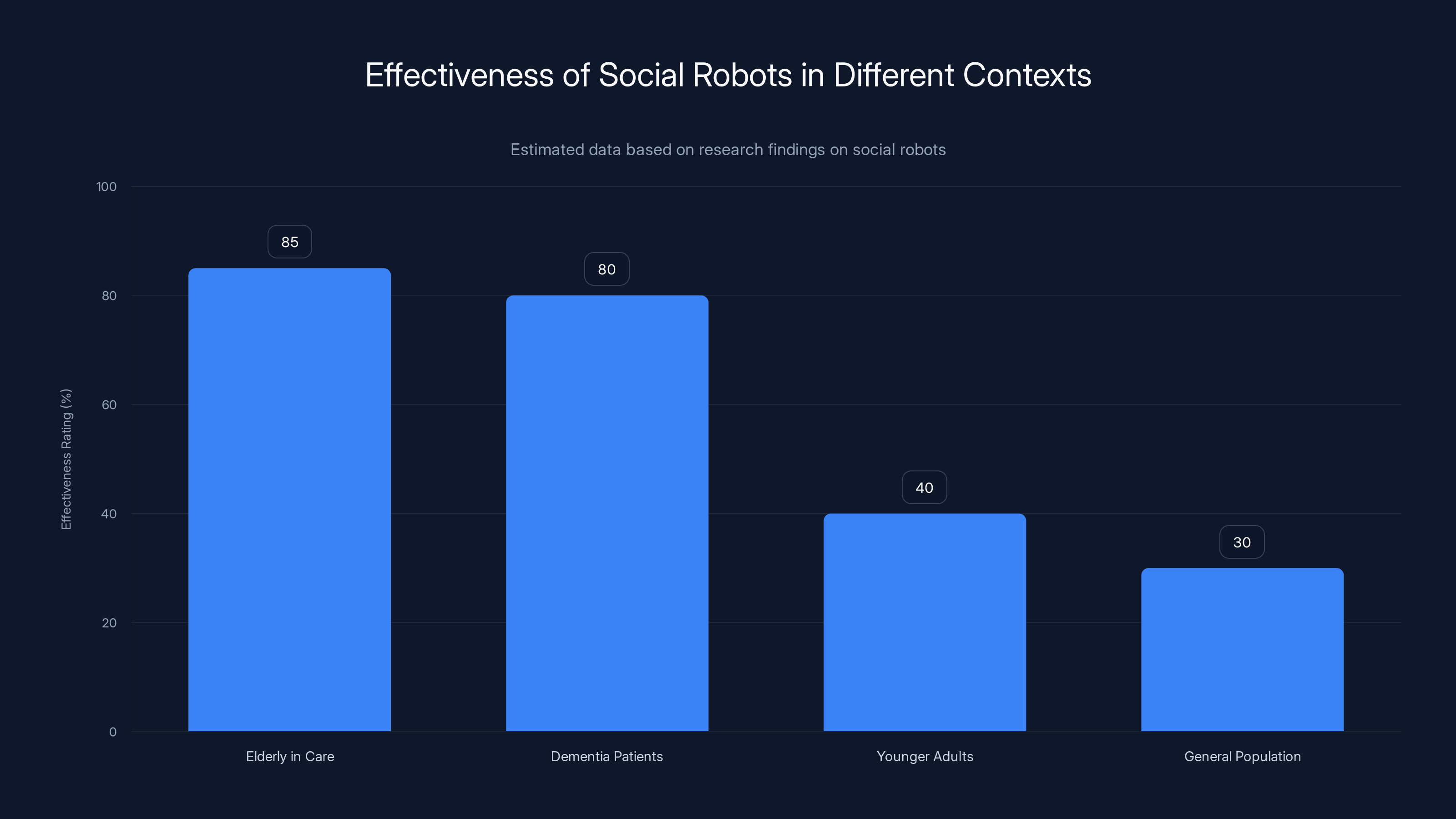

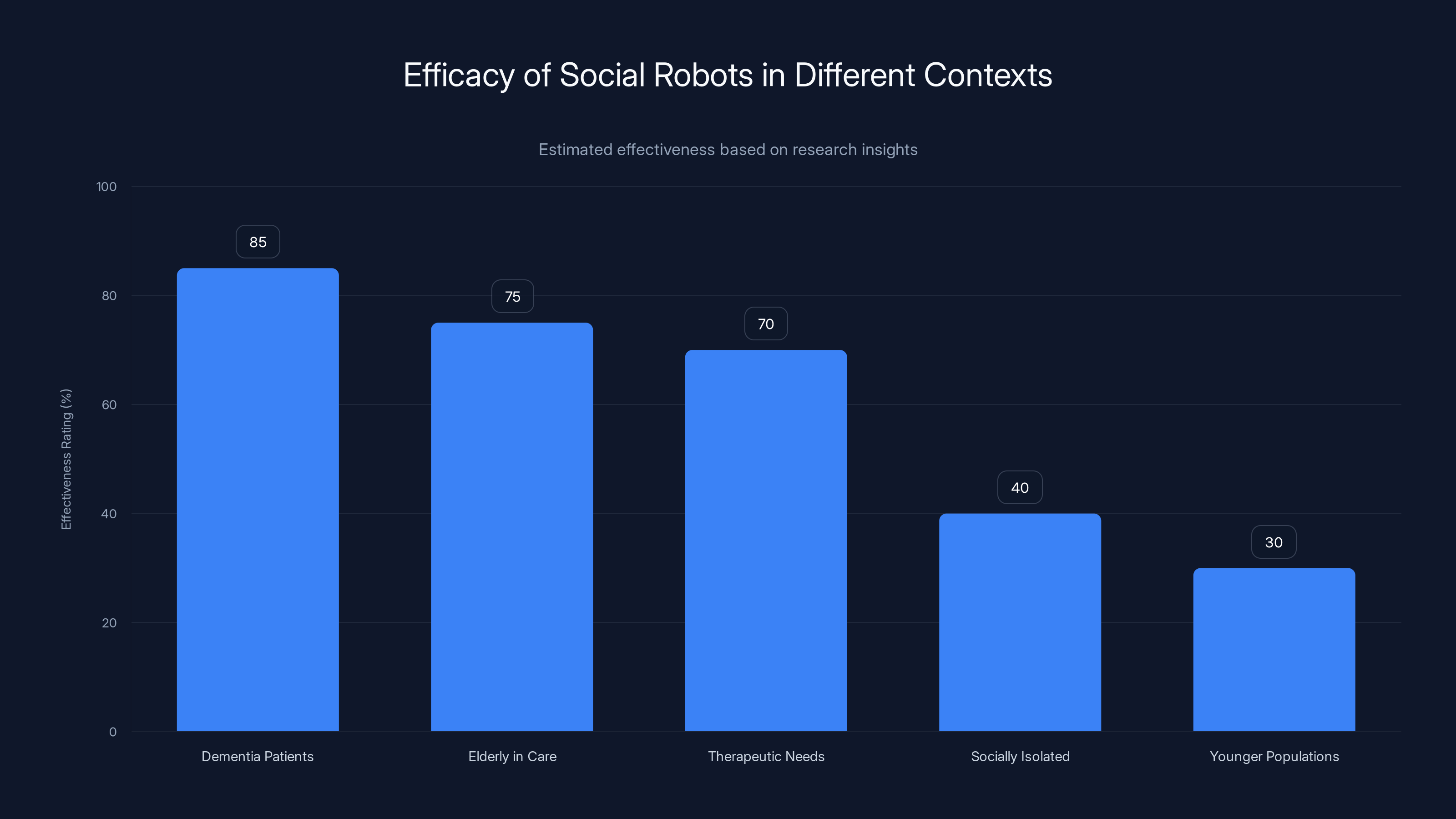

Social robots show high effectiveness in improving mood and engagement among elderly and dementia patients, but their impact is significantly lower for younger adults and the general population. Estimated data.

Understanding Mirumi: Design and Capabilities

Mirumi is small enough to clip onto a backpack or purse. It weighs about the same as a large smartphone. The device uses proximity sensors to detect when humans are nearby, triggering head movements that make it appear to notice you. Get closer or touch it, and Mirumi retracts, averting its googly-eyed gaze. This shy behavior is the core interaction mechanic.

The hardware itself is straightforward. Mirumi has a motorized head that can swivel and tilt, pressure sensors in its fuzzy exterior, and a speaker that produces gentle sounds. It connects via Bluetooth to a mobile app. Battery life is decent—roughly five to seven days of normal use before needing a USB-C charge through its rear port, which is admittedly awkward and occasionally hilarious to witness in public.

The app lets you customize Mirumi's name, view its "mood," and adjust sensitivity settings. You can also access a community feature where Mirumi users share photos and updates about their robots. On the surface, this creates a sense of participation in something larger. You're not alone with your cute robot; thousands of other people are doing the same thing.

The genius of Mirumi's design is its predictability combined with apparent personality. The head movements happen consistently. The shy behavior always plays out the same way. But because the movements are somewhat organic-looking and the robot is genuinely cute, your brain fills in emotional context. You're not projecting personality onto a piece of plastic. You're recognizing the personality that's already there.

Except you're not. You're experiencing a well-crafted illusion.

This distinction matters because it points to a fundamental limitation. Mirumi can't actually know you. It can't remember your last interaction in a meaningful way. It can't adapt to your emotional state or provide support tailored to your specific situation. Every interaction is predetermined. Every response was written by engineers months before you unboxed the device.

The Research Behind Social Robot Efficacy

Before dismissing Mirumi as a pointless gadget, let's look at what the evidence actually says.

Research into robotic pets is surprisingly positive in specific contexts. A notable study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that elderly patients with dementia showed measurable improvements in well-being and quality of life when interacting with robotic pets during lockdowns. Participants reported feeling less lonely. Care workers noted improved mood and engagement. Some patients who had become withdrawn became more communicative.

The mechanism isn't mysterious. Simple interaction provides stimulation. A robot that responds to touch gives you something to care for. That caregiving instinct, when activated, triggers positive neurological responses. Touch itself releases oxytocin, the hormone associated with bonding. A robot isn't a substitute for these basic human needs, but it can activate the neural pathways.

However—and this is crucial—the research also shows significant limitations. Robot efficacy depends heavily on context. It works better for:

- Patients with dementia who have limited awareness of the robot's limitations

- Elderly individuals in institutional care settings with limited access to other social interaction

- People with specific therapeutic needs (anxiety reduction, stimulation during recovery)

- Individuals who are already motivated to engage with the technology

It works worse for:

- Socially isolated people whose isolation stems from depression or mental health conditions requiring professional intervention

- Younger, digitally native populations who recognize the artificiality immediately

- People seeking genuine emotional reciprocity

- Individuals whose loneliness is situational rather than chronic

The National Institutes of Health has published research noting that robotic pets show promise specifically for dementia care and elderly populations, but effectiveness drops significantly when social isolation is the primary issue rather than a symptom of other conditions.

This matters because the marketing for products like Mirumi often positions them as solutions for loneliness broadly. But loneliness isn't monolithic. The loneliness of a 78-year-old with dementia in a care facility is neurologically and psychologically different from the loneliness of a 35-year-old professional in a major city. One might genuinely benefit from a cute robot. The other needs something deeper.

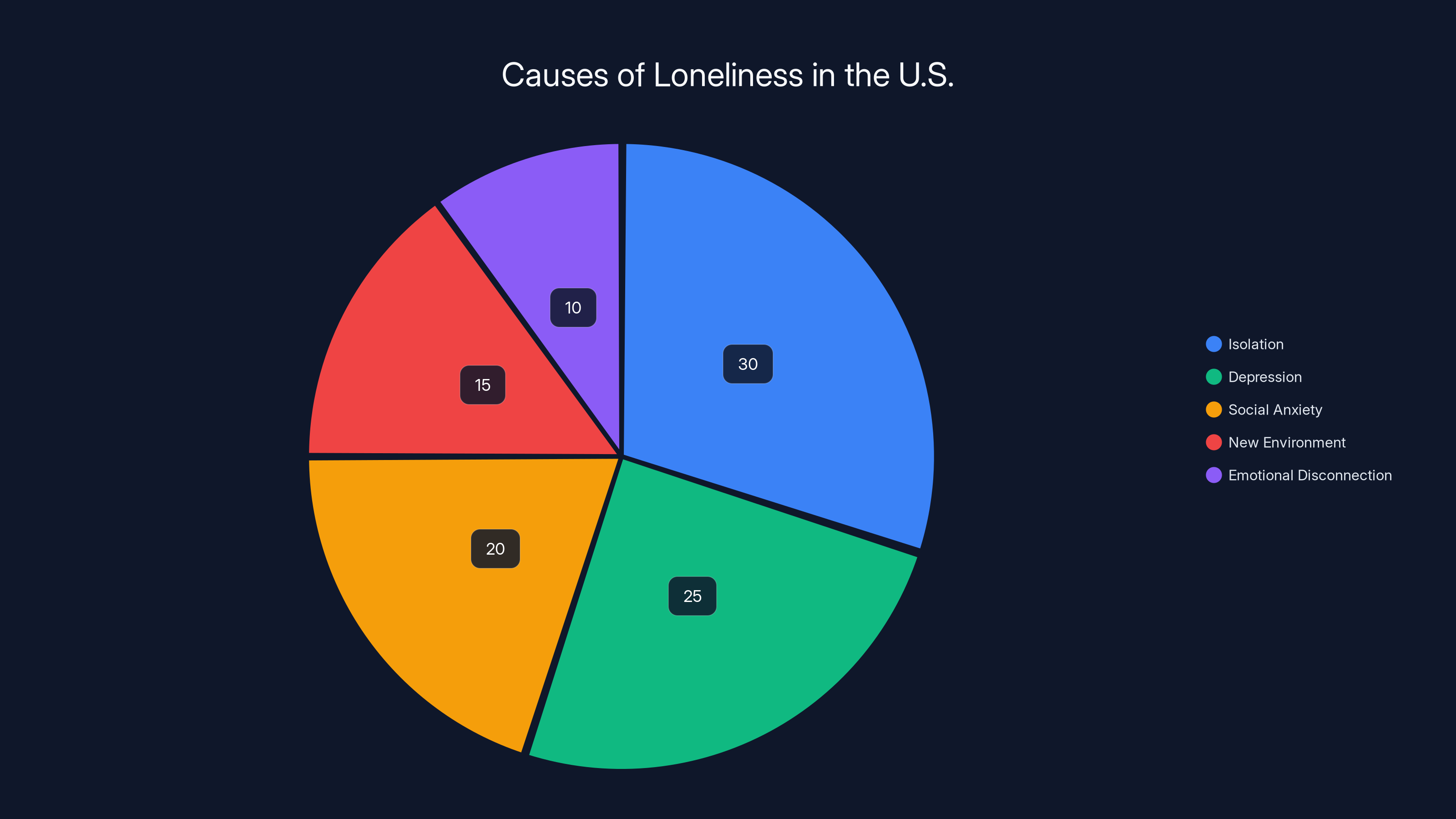

Isolation is the most reported cause of loneliness at 30%, followed by depression at 25%. Estimated data based on common causes.

The Daily Reality: What Actually Happens When You Live With Mirumi

This is where theory meets the weird reality of carrying a cute robot around New York City.

The first week is honeymoon phase. Mirumi is novel. You keep clipping it to your backpack. You notice the head movements. You feel a little spark of joy every time it notices someone and pans its head curiously. Other people find it charming. Strangers smile. Coworkers want to pet it. You're experiencing positive social feedback about your robot.

The second week is still fine. The novelty hasn't completely worn off. You're more aware of Mirumi's limited behavioral range, but you're not bothered yet.

By week three, Mirumi has become invisible background. You stop noticing its head movements. You forget to charge it occasionally. It sits in your bag, periodically swiveling its head at random people, and nobody reacts because everyone's focused on their phones. On a crowded subway, it notices absolutely nobody. The sensors aren't sensitive enough to distinguish between actual social interest and the ambient movement of bodies in a packed car.

The real problem emerges in week four when you realize something: Mirumi doesn't actually improve your day. It doesn't make your commute less lonely. It doesn't give you someone to talk to. The shy behavior that seemed endearing now registers as one-directional frustration. You reach to pet it, and it pulls away. Every time. Without fail. It's exactly like having a friend with severe social anxiety who will never reciprocate your affection.

That's not companionship. That's simulation of companionship.

I also have a gray Mirumi, sent as part of the review process. The plan was to see if two robots would interact with each other in interesting ways. They don't. They just sit near each other, occasionally swiveling their heads independently, completely unaware of each other's existence. It's like watching two people at a dinner party who both have their headphones in.

Then there's the cat situation.

My cat, Petey, is a chaos agent. He's seen Mirumi and decided it's a toy. A small, pink, squeaky toy with a tempting fluffy texture and moving parts. He bats at it. He chases it around the apartment. He definitely doesn't care that Mirumi is supposed to be shy. When Petey's around, the whole careful behavioral design falls apart. The robot can't distinguish between a person and a cat. Both register as "nearby entity." The result is a robot running away from a cat that's chasing it, which is less "therapeutic companion" and more "slapstick comedy."

What became clear over six weeks is that Mirumi's design assumes a specific context: a person living alone who is actively seeking social interaction but perhaps too anxious or emotionally guarded to pursue it with humans. In that scenario, Mirumi could serve a purpose. It gives you something to care for without the risk of rejection.

But for most people? For people with families, pets, roommates, or active social lives? Mirumi is just an expensive cute thing that gets ignored.

The Loneliness Epidemic: Context Matters

Here's what matters about loneliness that Mirumi can't address: much of it is structural, not emotional.

A report from the American Psychological Association found that nearly 30% of Americans report frequent loneliness. But the causes vary wildly. Some people are lonely because they're isolated—living alone with limited social access. Others are lonely because they're depressed and can't motivate themselves to reach out. Others are lonely in crowds because they don't feel understood or connected to the people around them.

Mirumi addresses exactly one of these: isolation combined with willing engagement. If you're homebound, living alone, and actively willing to interact with a cute robot, it might help. But if you're lonely because:

- You've moved to a new city and haven't made friends yet

- You're grieving and the world feels isolating

- You have social anxiety that prevents connection

- You're experiencing depression that makes socializing feel impossible

- You feel emotionally disconnected even in relationships

Then Mirumi doesn't solve the actual problem. At best, it's a bandage. At worst, it's a distraction from getting actual help.

Japan's embrace of social robots also reflects a specific cultural context that doesn't directly translate to Western societies. Japan is aging faster than almost any developed nation. Birth rates are at historic lows. There's genuine urgency around finding ways to support elderly populations with limited family available to provide traditional caregiving. Additionally, Japanese culture has less stigma around having objects as companions. This isn't seen as weird or pathological. It's seen as a practical solution to a structural problem.

In Western contexts, loneliness often carries different emotional weight. There's shame attached to it. If you're lonely, the cultural message suggests something's wrong with you, not with your circumstances. This makes people less likely to engage openly with solutions, especially cute robot solutions that might signal vulnerability.

Estimated data suggests Japan has a higher acceptance level for robot companions due to cultural factors, compared to Western markets.

Comparing Mirumi to Other Companion Tech

Mirumi isn't alone in this space. There are other approaches to fighting loneliness through technology, and comparing them reveals what actually works.

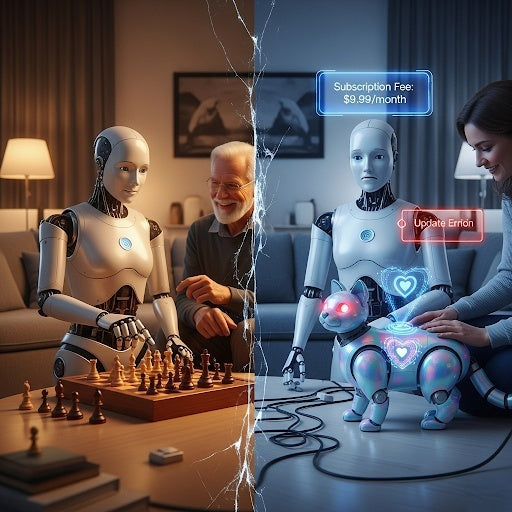

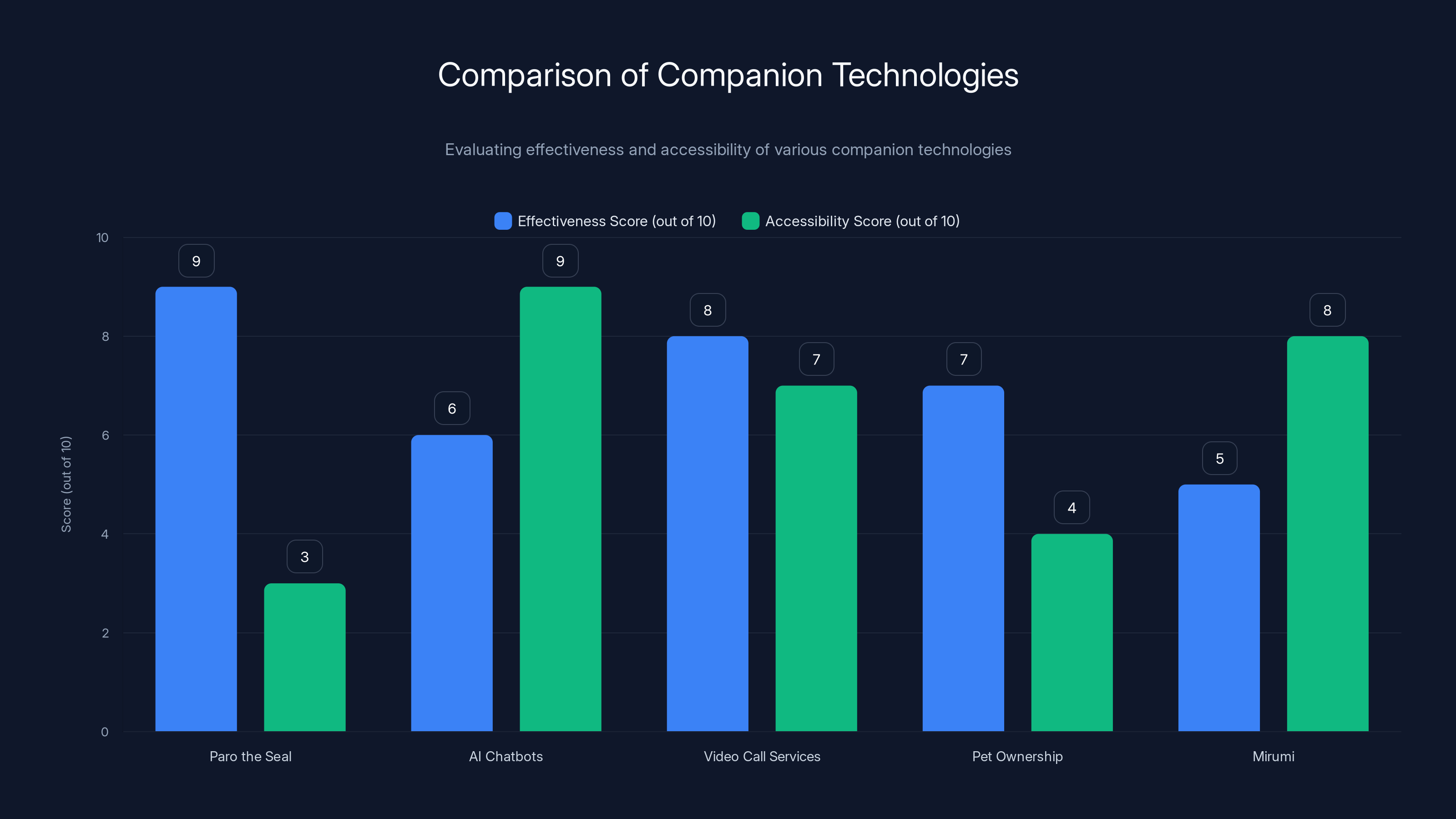

Paro the Seal is the gold standard because it has the most research behind it. Multiple peer-reviewed studies show measurable behavioral and psychological improvements in dementia patients. It's used in hospitals and care facilities worldwide. But here's the thing: Paro costs around $6,000. It's institutional technology. It's not designed for personal use by the general public.

AI Chatbots like Chat GPT or specialized systems like Replika are another approach. These offer conversational companionship. You can talk to them, ask for advice, vent about your day. They respond contextually. The interaction is more dynamic than Mirumi's purely physical behavior. But they lack embodiment. There's something missing about talking to text on a screen versus having a physical object to hold and care for.

Video Call Services designed specifically for elderly people aim to facilitate connection between isolated seniors and trained companions. This is genuinely helpful because you're engaging with an actual human, just remotely. The limitations are time constraints and cost, but the effectiveness is real.

Pet Ownership, the traditional answer, works for many people but requires commitment, resources, and sometimes physical ability. A real pet provides unconditional emotional responsiveness that no robot can match. But not everyone can care for a pet.

Mirumi's niche is somewhere between pets and nothing. It requires less commitment than a pet, costs less than Paro, and provides more physical interaction than a chatbot. But it's also less effective than any of these alternatives for actually addressing loneliness.

The positioning matters. Mirumi isn't marketed as "slightly better than nothing." It's marketed as a solution. That disconnect is the real problem.

The Psychology of Cute Robot Design

Why does a robot this limited in functionality generate as much positive response as it does?

The answer is cute factor overrides logical analysis. Kawaii culture, or the Japanese aesthetic of cuteness, is psychologically powerful. When something is cute, your brain prioritizes emotion over rationality. Large eyes relative to head size? That signals "baby." Your caregiving instincts activate. Soft texture? Dopamine release. Gentle movements? Non-threatening. The cumulative effect is that you feel affection before your rational brain catches up to register that you're interacting with a sophisticated silicon toy.

This is the same psychology that makes people invest emotionally in Tamagotchi digital pets, build relationships with Siri, or feel protective of characters in video games. Your brain's social and caregiving systems don't easily distinguish between genuine emotional needs and simulations of emotional needs.

Yukai Engineering, the Japanese company behind Mirumi, clearly understands this. Every design choice is calibrated for maximum emotional resonance. The owlish face with disproportionately large eyes. The soft pink coloring. The gentle head movements that seem curious and aware but are actually mechanical. Even the name—Mirumi—sounds affectionate and diminutive.

The app community feature is clever too. By showing you photos of thousands of other people's Miruumis, the app leverages social proof. You're not weird for carrying this robot. Thousands of other people are doing the same thing. This normalization is powerful. It makes the choice to invest in a cute robot feel more reasonable.

Social robots show high effectiveness in enhancing well-being among dementia patients and elderly in care, while being less effective for socially isolated individuals and younger populations. (Estimated data)

The Barrier of Disillusionment

Where Mirumi consistently fails is the moment disillusionment sets in.

Someone orders Mirumi expecting companionship. For the first few interactions, the design works. The robot seems aware, responsive, personality-full. But then the person realizes something: there is no learning happening. The robot responds the same way to the same stimuli every single time. The shyness isn't genuine shyness born of caution or trust building. It's a program that runs when proximity sensors trigger above a certain threshold.

This is where Mirumi fails people who genuinely need companionship. The loneliest people—those looking for something that understands them, remembers their name, learns their preferences, adapts to their moods—Mirumi can't provide that. The robot's simplicity, which is appropriate for dementia patients or the institutionalized elderly who don't cognize limitation, becomes a source of frustration for cognitively intact individuals seeking genuine connection.

The marketing promises "companionship." The product delivers "responsive object." That gap is where disappointed customers live.

There's also a darker possibility that doesn't get discussed much in tech journalism. What if cute robots, by providing a low-friction simulation of companionship, actually reduce motivation to seek genuine human connection? If Mirumi costs $100-150 and requires no emotional risk, why invest the effort in developing real relationships? Why push through social anxiety to meet real people when you have a robot that will never reject you?

This is speculative, and research hasn't shown widespread negative effects yet, but it's worth considering. Technology companies aren't incentivized to build products that nudge people away from their own products. If cute robots become convenient enough, they could inadvertently become obstacles to the very thing they're supposed to facilitate.

Cultural Differences in Robot Acceptance

Mirumi works better in Japan than it would in equivalent markets elsewhere.

This isn't a judgment about Japanese people or Japanese culture being more gullible or less rational. It's about how different cultures relate to technology and objects more broadly. In Japan, there's philosophical acceptance that objects can have quasi-personhood. The Shinto concept of "mononoke"—spirits that inhabit objects—has deep cultural roots. Even secular Japanese people often relate to objects with a degree of emotional animism that's less common in Western contexts.

Additionally, Japanese culture has fewer stigma around non-traditional companionship. There's significant market for virtual girlfriend apps, AI chatbots designed for emotional connection, and robot pets. These aren't niche products marketed to weirdos. They're mainstream solutions to real problems.

In the West, there's more skepticism and self-consciousness. Carrying a cute robot around New York generates reactions different from carrying it around Tokyo. In NYC, people assume you're either a tech journalist (which I am, granted) or making a statement about consumerism. The cultural narrative around cute robots is less "practical solution" and more "cute frivolity."

This matters because it means Mirumi's success in Japan might not translate directly to Western markets. The product works better in cultures where people are already comfortable with these types of solutions.

Paro the Seal scores highest in effectiveness due to extensive research backing, but is less accessible due to cost. AI Chatbots are highly accessible but less effective. Mirumi offers moderate effectiveness and high accessibility. (Estimated data)

What Actually Helps Loneliness (Beyond Robots)

If cute robots aren't the answer, what is?

The most effective interventions tend to be unsexy and require actual effort:

Community Building: Joining groups—hobby clubs, faith communities, sports leagues, volunteer organizations—creates repeated low-pressure interaction with humans who share your interests. This builds relationships gradually and authentically. It's harder than buying a robot. It requires vulnerability and effort. But it actually works.

Behavioral Activation: When depression or anxiety creates loneliness, the solution often involves deliberately practicing social behaviors despite discomfort. This might mean taking a class, attending a meetup, or calling a friend even though you don't feel like it. Therapists have research-backed protocols for this.

Professional Support: Chronic loneliness linked to depression, trauma, or social anxiety responds well to therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy, in particular, has strong evidence for treating both the underlying conditions and the loneliness they create.

Life Structure Changes: Sometimes loneliness requires addressing underlying life circumstances. Moving to a location with stronger community, changing jobs, pursuing education, or shifting daily routines can remove structural barriers to connection.

Digital Connection With Intention: Unlike Mirumi, intentional use of technology to maintain existing relationships (video calls with distant friends, online communities around shared interests) does reduce loneliness, especially when it supplements rather than replaces in-person interaction.

None of these are as convenient as buying a cute robot. But they're all more effective, and effectiveness is what actually matters.

The Future of Social Robots: Where This Is Heading

Social robots aren't going away. If anything, they're going to get better at simulating interaction.

Next-generation robots will have more sophisticated AI. Instead of predetermined behaviors, they'll use machine learning to adapt responses based on interaction history. They'll remember your preferences, use your name, reference previous conversations. This will make the simulation more convincing. It'll also make disillusionment potentially worse, because the sense of relationship building will feel more real before the limitations become apparent.

Robotics companies are also exploring more sophisticated physical designs. Robots with more expressive faces, better locomotion, multi-modal interaction (speaking, gesture, touch). Some are adding camera vision and real-time facial recognition to adapt to your emotional state.

These improvements are technically interesting and will find real applications in specific domains—elderly care in institutions, therapeutic robots for children with autism, entertainment robots for hospitalized patients. But they won't solve the fundamental problem: a robot, no matter how sophisticated, is a robot. It can't actually care about you. It can only simulate caring.

The ethical dimension is worth considering too. As robots get cheaper and better, there's economic incentive for manufacturers to market them as solutions to social infrastructure problems. Instead of investing in community spaces, affordable healthcare, urban planning that facilitates connection, or social services that address loneliness, companies can sell cute robots to individuals. This is better for company revenue. It's worse for society.

There's also a class dimension. Cute companion robots are becoming more affordable, but they're still not free. They're most accessible to people who can afford them—people who, statistically, have better access to actual social resources anyway. Meanwhile, the people most affected by structural loneliness—low-income seniors, institutionalized people with dementia, folks in isolated rural areas—are least likely to benefit from a $150 robot purchase.

Real Talk: Why Mirumi Disappointed Me

I want to be fair to Mirumi. It's a well-designed product that does exactly what it's engineered to do. The hardware is solid. The software is simple but functional. The company seems genuinely committed to the concept of cute robots as therapeutic tools.

But I went into this expecting a companion, and what I got was a really adorable toy. The distinction matters.

After six weeks, Mirumi hasn't made my life better. It hasn't reduced my loneliness—though I don't experience significant loneliness anyway. It hasn't given me something meaningful to care for. It's become background clutter that occasionally makes a mechanical sound when I grab my backpack.

The cute factor wore off. That's the real lesson. The initial emotional response—"Oh my god, this is so cute, I'm in love"—is powerful but unsustainable. Once rationality catches up to emotion, once you realize you've invested affection in something that can't reciprocate, disappointment is the inevitable result.

For people with dementia or certain cognitive conditions, this doesn't happen. The robot remains perpetually novel and engaging. For everyone else, it's just a matter of time.

What surprised me most wasn't that Mirumi didn't work. It was how quickly I forgot about it. By week three, it was like carrying an extra pen. By week six, I had to remind myself to charge it. The robot designed to encourage attachment failed to maintain my attention for longer than a few weeks.

That's not an indictment of Mirumi specifically. It's a structural limitation of what current technology can do. Until robots can engage in genuine reciprocal interaction, adapt to your emotional needs in real time, and provide unpredictable responses that keep you mentally engaged, they're fundamentally limited as companions.

We're not there yet. And honestly, I'm not sure we should be rushing to get there.

What Manufacturers Get Wrong About Loneliness

The core misunderstanding in social robot design is treating loneliness as a problem that isolation causes rather than a symptom of something deeper.

Loneliness is heterogeneous. It has different causes, different experiences, different solutions depending on context. Marketing a single product—especially a robot—as "the" solution to loneliness is fundamentally dishonest.

Manufacturers know this. But it's not profitable to acknowledge. Profitable messaging is simple: "Loneliness is bad. You're lonely. Buy this robot. Problem solved." The actual message should be: "Loneliness is complex. Depending on its cause, you might need community, professional support, behavioral change, life restructuring, or yes, occasionally a supplementary tool like a robot."

But that doesn't fit in marketing copy.

There's also a failure to engage with research limitations. Yes, robotic pets help some patients with dementia. Yes, they provide comfort to isolated elderly people. But "helps some people in specific contexts" is not the same as "solves loneliness." Marketers blur this line deliberately.

The other failure is not acknowledging that robots—by design—remove human from the equation entirely. There's something to be said for that in specific contexts. A robot will never reject you. It will never disappoint you. It will never hurt you emotionally. For someone with severe social anxiety or trauma around interpersonal connection, that predictability and safety might be valuable in the short term.

But as a long-term solution? No. Humans need humans. The technology that most effectively reduces loneliness is the technology that facilitates connection between actual people, not technology that replaces people.

The Role of Automation in This Ecosystem

Here's where I need to mention something: platforms like Runable approach the loneliness problem differently. They focus on automation and productivity, not companionship. But there's an indirect connection worth exploring.

One reason people feel lonely is time scarcity. You're overwhelmed with work, managing endless administrative tasks, drowning in emails and meetings. You don't have bandwidth for building relationships or engaging with community. Automation tools address this from the opposite direction: by freeing up time and mental energy for things that matter more.

Runable's AI-powered automation for presentations, documents, reports, and workflows actually addresses a piece of the loneliness puzzle indirectly. When you're not spending 10 hours per week on formatting reports, you have time for actual human interaction. When you're not exhausted from administrative overhead, you have energy for relationships.

This isn't marketed as a loneliness solution, which is honest. But it's potentially more effective than cute robots at actually creating space in people's lives for connection. Automation that gives you back time is actually more valuable than objects that simulate presence.

Use Case: Automate your weekly reports so you have Friday afternoons free to actually connect with colleagues in person instead of being heads-down in spreadsheets.

Try Runable For Free

Reconsidering: When Mirumi Actually Works

Despite my disappointment, I want to be precise about where Mirumi might actually be valuable.

It works best for:

Elderly people with cognitive decline who aren't able to remember the robot's limitations. For someone with dementia, every interaction can feel fresh. The robot remains endlessly novel and engaging.

Institutionalized patients without regular family contact who need stimulation and something to direct caregiving impulses toward. In a care facility where human staff are stretched thin, a robot that encourages engagement and reduces behavioral problems serves a genuine function.

People with specific anxiety disorders where the robot's predictability and non-judgment provides a bridge to engaging with more complex human interaction. A therapist might actually recommend this as a supplementary tool.

Children with autism spectrum conditions who respond to the robot's structured, rule-based interaction patterns that are easier to parse than unpredictable human behavior.

These are legitimate use cases. They're just not "lonely people in general," which is how Mirumi gets marketed.

If you're in one of these categories, Mirumi might genuinely help. If you're outside these categories, you're probably better served by something else—therapy, community, actual human relationships, or yes, if your life is just too full to manage those things, at least understanding what the robot can and can't do for you.

FAQ

What is a social companion robot?

A social companion robot is a small, interactive device designed to provide companionship through behavioral simulation and physical interaction. These robots typically use sensors to detect human presence, respond with programmed movements and sounds, and create the illusion of emotional awareness. Products like Mirumi are engineered to evoke caregiving instincts through cute design and gentle, predictable behaviors, though they lack genuine emotional reciprocity or learning capabilities.

How do social robots like Mirumi actually work?

Mirumi uses proximity sensors to detect nearby humans, triggering head movements that simulate awareness and curiosity. When you touch or approach it, the robot retreats based on programmed shy behavior. A Bluetooth app connects to the device, allowing users to customize the robot's name and access community features showing other users' robots. The robot operates on batteries that need weekly charging via USB-C. All behaviors are predetermined by engineers, with no genuine learning or adaptation occurring during normal use.

What does research say about social robot effectiveness?

Research shows that social robots like Paro the seal provide measurable benefits in specific, limited contexts. Studies published through the NIH document improved mood, engagement, and well-being among elderly and dementia patients in institutional care settings. However, effectiveness drops significantly for younger, cognitively intact individuals seeking genuine companionship. Robots work best as supplementary tools in therapeutic contexts, not as replacements for human connection or professional mental health support.

Why do manufacturers market social robots as loneliness solutions?

Loneliness is a complex, multifaceted problem with different causes and solutions for different populations. Manufacturers simplify this complexity because honest marketing—"works for dementia patients in care facilities but probably not for you"—doesn't drive sales. Marketing that positions robots as universal loneliness solutions is deliberately misleading, even if robots do provide value in specific contexts. The financial incentive pushes toward overpromising rather than accurate positioning of what these devices can and cannot do.

What's the difference between Mirumi and other companion technology?

Mirumi provides physical interaction and tactile feedback but zero conversational ability. AI chatbots like Chat GPT provide dynamic conversation but lack embodiment and physical presence. Paro the seal has the most research supporting its effectiveness but costs $6,000 and is designed for institutional use. Traditional pet ownership provides superior emotional reciprocity but requires significant commitment and resources. Productivity automation tools indirectly address loneliness by freeing up time for human connection rather than simulating presence. Each approach addresses different aspects of the loneliness problem.

Is carrying a social robot weird?

Cultural context matters significantly. In Japan, social robots are mainstream solutions to legitimate problems and don't carry social stigma. In Western contexts, especially urban areas, you'll encounter skepticism and assumptions that you're either a technology journalist or making a statement. This cultural difference affects whether people actually use these devices long-term. In cultures where social robots are normalized, adoption and sustained engagement are higher. In cultures with skepticism toward human-technology emotional bonds, interest fades quickly as the artificial nature becomes apparent.

Who should actually buy a social robot?

If you're an elderly person living alone with mild cognitive decline, Mirumi or similar devices might provide genuine benefit. If you're a caregiver for someone with dementia, it might reduce behavioral problems. If you have specific anxiety disorders, a therapist might recommend it as part of a broader treatment plan. If you're a generally healthy adult looking for companionship, your money and time are better spent on actual human connection, therapy if needed, or community building. Robots don't replace these; they supplement them in very specific contexts.

What's the long-term future of social robots?

Social robots will become more sophisticated, with better AI making behavior more adaptive and personalized. However, core limitations will persist: robots can simulate emotional reciprocity but can't provide genuine understanding or care. The real risk isn't that robots become so good they replace human connection, but that companies will market them so aggressively for loneliness that people invest in robots instead of building actual community. The most valuable technology for addressing loneliness will probably be tools that facilitate human connection (better community platforms, better healthcare access) rather than robots that simulate it.

Can social robots actually help with depression or anxiety?

Not directly. If depression or anxiety is the underlying cause of loneliness, a robot won't treat those conditions. What might help is therapy, medication, behavioral activation, and community support—none of which a robot provides. Robots might serve as a bridge or supplementary tool for people with severe social anxiety, but they shouldn't replace professional mental health treatment. Using a robot as a primary intervention for depression or anxiety-driven loneliness is like taking vitamin supplements instead of treating diabetes. It might make you feel slightly better, but it won't address the actual problem.

Why does Mirumi seem so cute compared to other robots?

Mirumi's design leverages specific psychological principles. The oversized eyes trigger caregiving instincts because they mimic infant features. The soft pink texture and smooth movements minimize threat perception. The name "Mirumi" sounds diminutive and affectionate. The shy behavior creates a sense of vulnerability that encourages nurturing. The company understands kawaii—the Japanese aesthetic of cuteness—which is fundamentally engineered to bypass rational analysis and trigger emotional response. This design excellence doesn't mean the robot is more effective at reducing loneliness, just that it's very good at making you feel affection initially, before rationality catches up.

The Bottom Line: Where We Actually Are

Mirumi is a well-designed product that does what it's engineered to do. It's cute. It responds to touch. It encourages interaction. In very specific contexts—dementia care, institutional elderly care, therapeutic use—it provides measurable value.

For everyone else, it's adorable in the moment and forgettable in the longer term.

The real insight isn't that cute robots are useless. It's that we keep looking for technological solutions to problems that are fundamentally human and social. Loneliness isn't a bug in the system that better technology will fix. It's often a symptom of deeper issues: social dislocation, lack of community, unprocessed trauma, untreated mental health conditions, or legitimate structural isolation.

Robots can't fix any of these things. They can distract from them. They can simulate a relationship without requiring vulnerability. They can provide comfort that feels safe because there's no risk of rejection. But they can't actually address the underlying causes.

If you're lonely and looking for solutions, I'd recommend, in this order:

- Identify the actual cause. Is it isolation, depression, anxiety, grief, lack of community, or something else? The cause determines the solution.

- Pursue human connection intentionally. Join groups, take classes, volunteer, attend meetups. Push through discomfort because on the other side is actual relationship.

- Get professional support if needed. Therapy actually works. If mental health conditions are driving loneliness, medication and behavioral intervention can help.

- Build structure into your life. Repeated exposure to the same people in regular contexts builds relationships more effectively than any technology.

- Then, if you want a cute robot as a supplementary tool, go for it. Just understand what it is and isn't.

Mirumi is a cute robot, not a solution to loneliness. The distinction matters because your well-being depends on it.

That's the real promise of cute robots: not to solve loneliness, but to remind us that loneliness isn't something technology can fix. It's something human connection, community, and sometimes professional support can address.

The irony is that recognizing these limitations might be the most valuable thing this cute pink robot taught me.

Key Takeaways

- Social robots like Mirumi are well-designed but fundamentally limited as loneliness solutions due to lack of genuine emotional reciprocity.

- Research shows effectiveness only in specific contexts: dementia patients, institutionalized elderly, therapeutic use—not general loneliness.

- Novelty wears off quickly for cognitively intact users; the robot's predetermined behaviors become predictable within 3-4 weeks.

- Japan's cultural embrace of cute objects and robots stems from different philosophical traditions, making adoption patterns different than Western markets.

- Loneliness requires addressing root causes through community, therapy, or behavioral change—technology can supplement but not replace these interventions.

Related Articles

- AI Companion Robots and Pets: The Real-World Shift [2025]

- OlloBot Cyber Pet Robot: The Future of AI Companions [2025]

- Ludens AI's Adorable Robots at CES 2026: Meet Cocomo and Inu [2025]

- Why Gen Z Is Rejecting AI Friends: The Digital Detox Movement [2025]

- The Offline Club: How People Are Fighting Phone Addiction in 2025

- Microscopic Autonomous Robots Smaller Than Salt: Engineering the Impossible [2025]

![Social Companion Robots and Loneliness: The Promise vs Reality [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/social-companion-robots-and-loneliness-the-promise-vs-realit/image-1-1769789690889.jpg)