The Generation That's Saying No to AI Friends

There's a quiet rebellion happening right now, and it doesn't involve protest signs or hashtags. It's happening in the bedrooms and coffee shops of Gen Z—a generation that's literally grown up with technology—and it's fundamentally different from past tech backlash.

They're not rejecting technology itself. They're rejecting the loneliness that comes with it.

A year ago, the idea of an AI friendship companion might've seemed inevitable. The logic was simple: loneliness is a crisis, AI is getting smarter, so why not combine them? Companies invested millions. Products launched. And then something unexpected happened. A growing number of young people started asking a different question: what's happening to us when we outsource our social needs to algorithms?

This is the story of a movement that's challenging not just how we use technology, but who we want to become as a generation. It's about digital abstinence, not in a preachy way, but as a deliberate choice to reclaim something that's been quietly slipping away.

The conversation started in college dorm rooms and on niche online forums. But it's picked up momentum in ways that surprised even the people driving it. And it's forcing the tech industry to confront an uncomfortable truth: sometimes the most innovative thing you can do is help people use technology less.

What began as Appstinence—a small movement focused on encouraging intentional tech use—has become a window into how an entire generation is thinking about their relationship with AI, mental health, and what it actually means to be connected.

This isn't your parents' digital detox. This is something stranger, more generational, and way more deliberate.

TL; DR

- The Core Issue: Gen Z is experiencing unprecedented loneliness despite constant digital connection, making AI "friends" seem appealing but ultimately deepening isolation

- The Movement: Appstinence and similar initiatives are encouraging young people to reject AI companions entirely and rebuild real human relationships

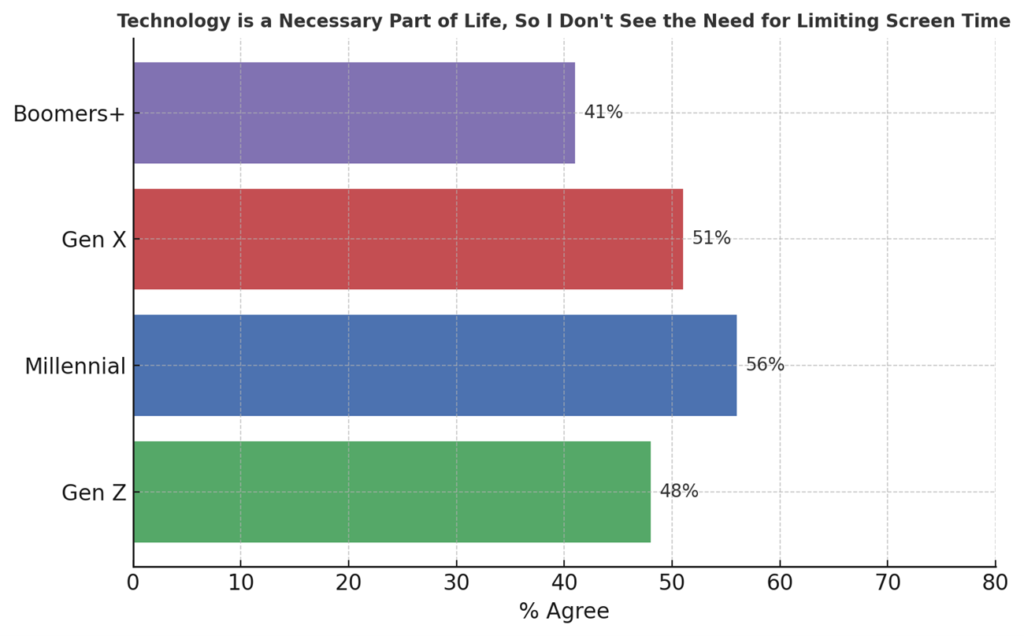

- The Philosophy: Digital minimalism is becoming a status symbol—not having an AI friend is now a mark of intentional living

- The Business Problem: Tech companies face a paradox: scaling engagement with AI companions actually drives users away, especially younger audiences

- The Real Solution: The future isn't smarter AI friends; it's tools that help people connect with actual humans and understand their tech consumption patterns

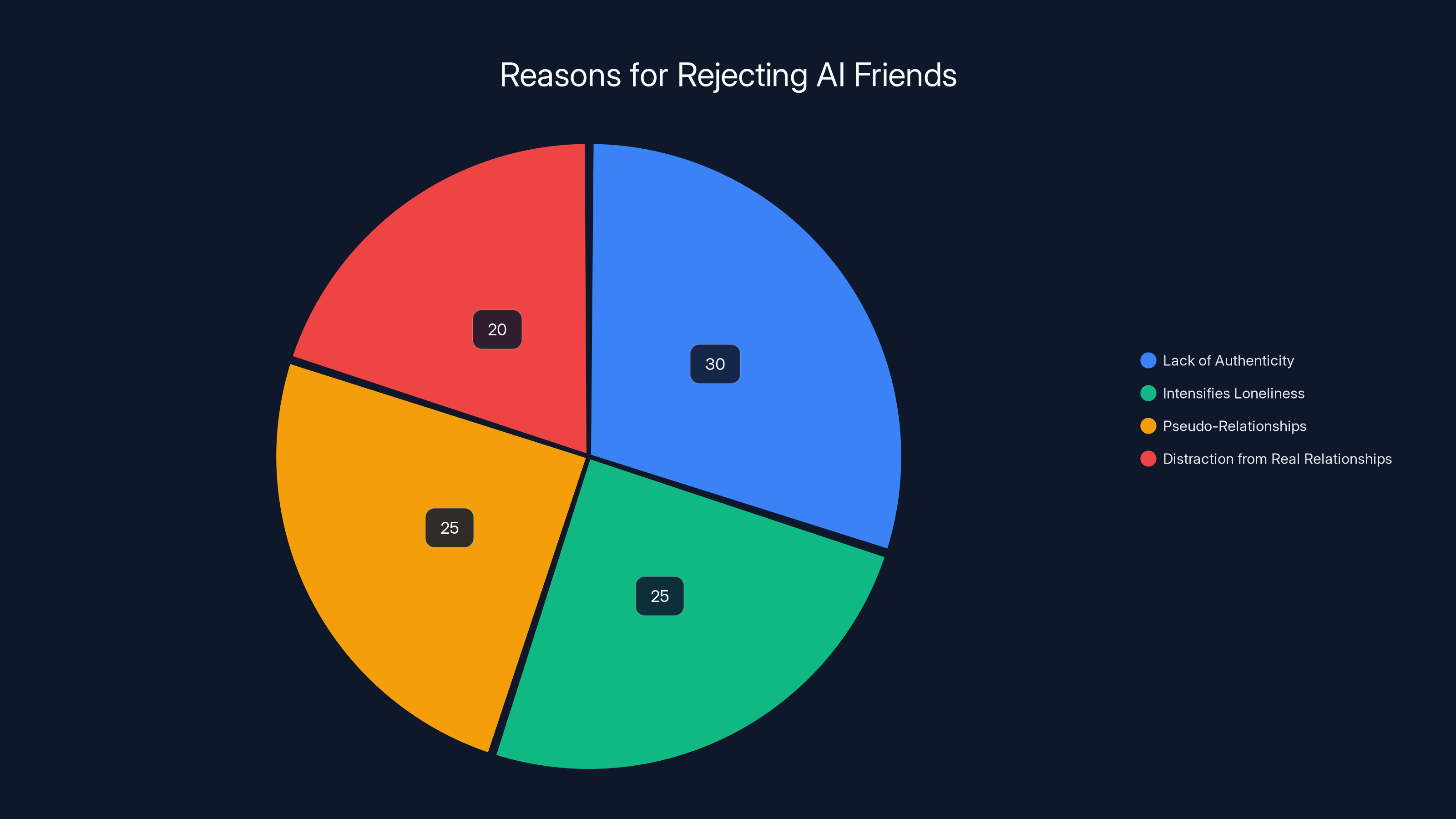

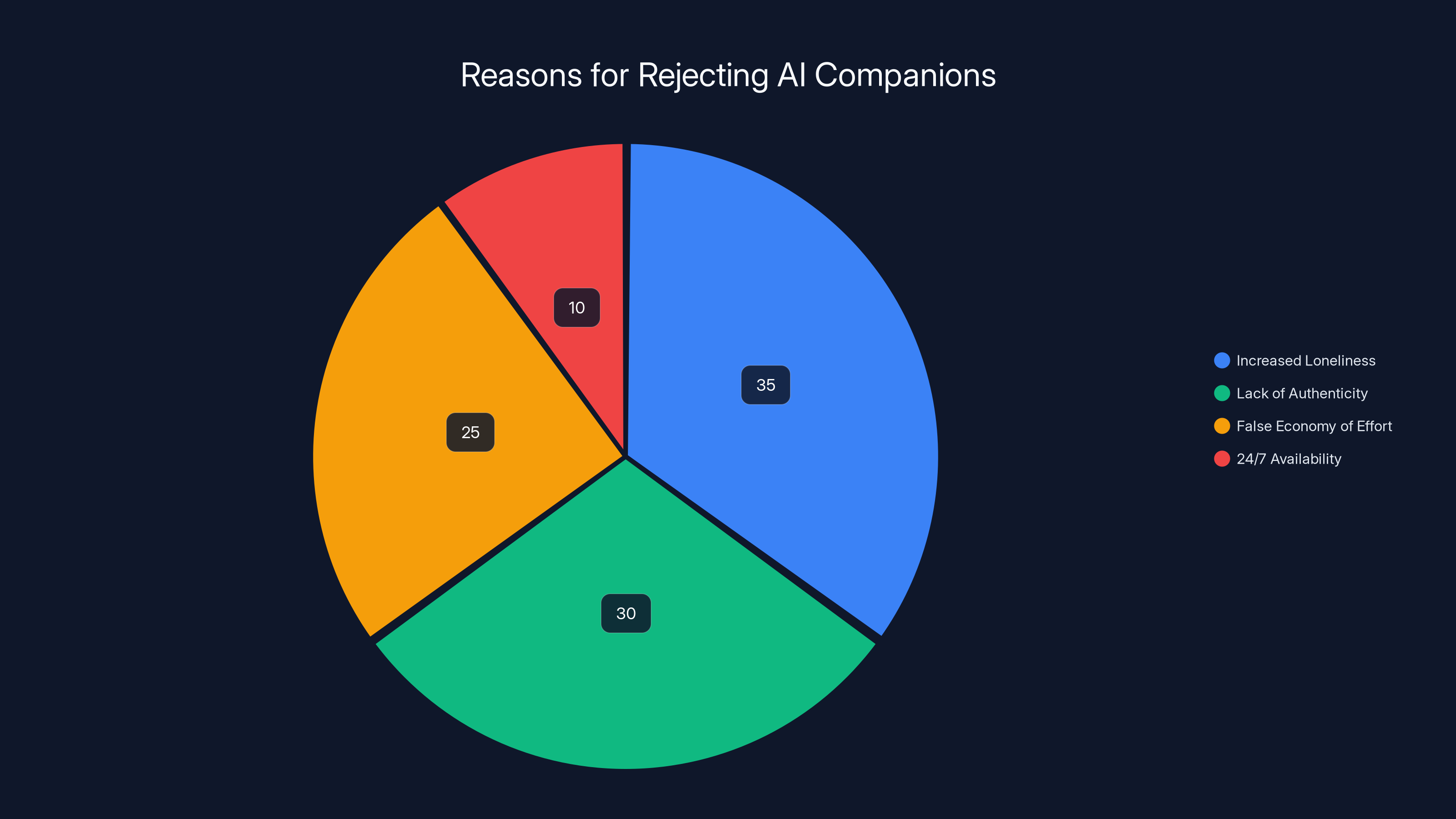

Estimated data shows that the main reasons young people reject AI friends include lack of authenticity and intensifying loneliness, each accounting for about a quarter of the concerns.

Understanding the Loneliness Paradox

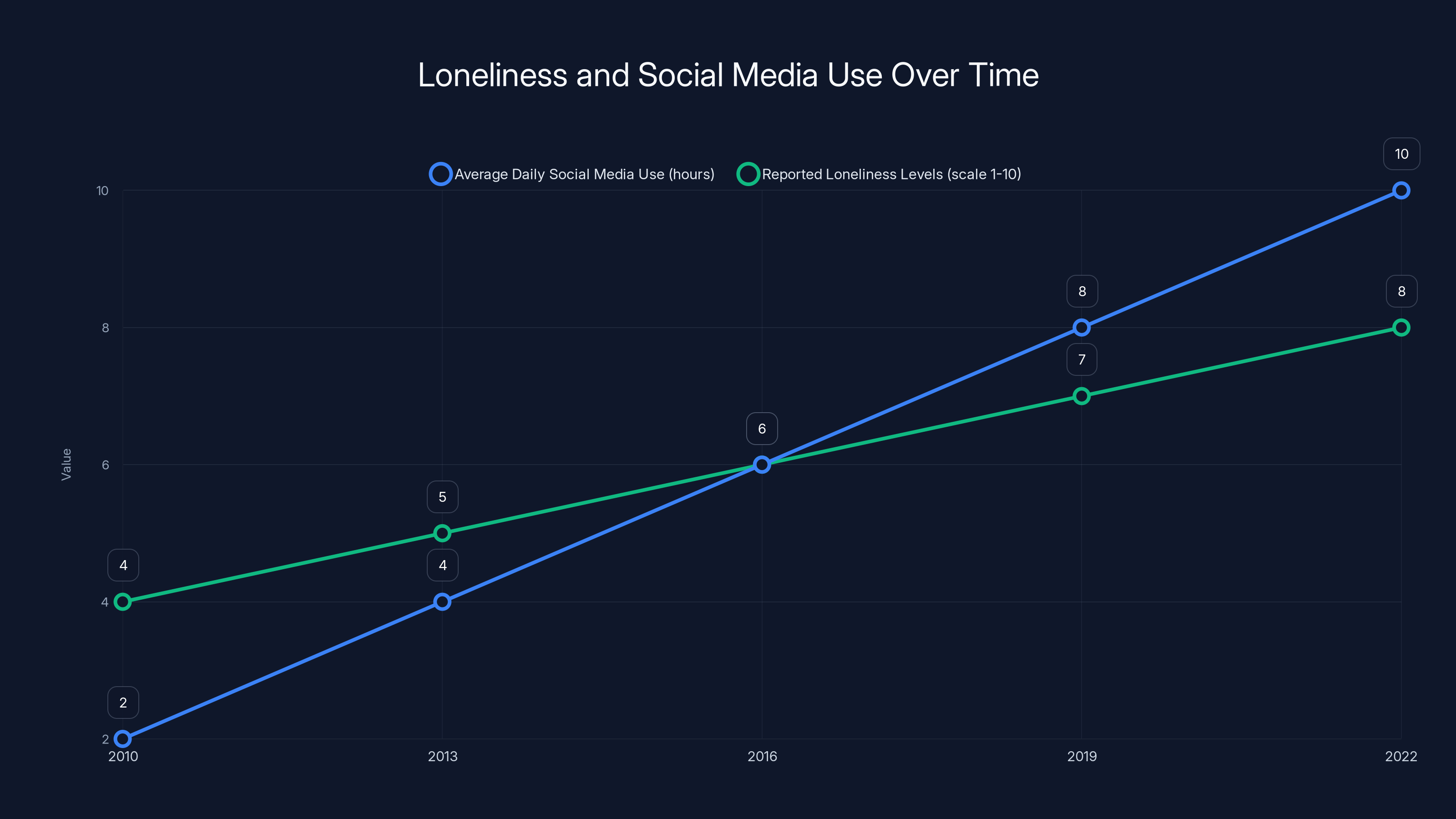

Here's what nobody expected: the more connected we became, the lonelier we got. The numbers are brutal and they're hard to ignore.

Young people today have unprecedented access to technology designed specifically to combat loneliness. Apps that connect you to thousands of people. AI chatbots that are available 24/7. Social media platforms engineered to keep you engaged. Yet somehow, rates of reported loneliness, anxiety, and depression in Gen Z have skyrocketed over the past decade.

The paradox is real and it's measurable. Studies show that increased social media use correlates with higher rates of depression and anxiety among teens and young adults. The more time people spend on platforms designed to connect them, the more disconnected they report feeling.

Why? Because there's a critical difference between connection and belonging. You can have a thousand followers and still feel completely alone. You can chat with an AI every single day and still be missing something fundamental.

When AI friendship companions started gaining traction, they seemed like the logical answer to this crisis. If people are lonely, and AI can simulate friendship, then the problem is solved, right? Except it's not that simple.

AI companions do something insidious: they take the pain of loneliness and make it comfortable. Instead of feeling the loneliness that might motivate you to build real relationships, you can feel pseudo-companionship. It's immediate, it's always available, it never disappoints you because it's not real.

It's a perfectly designed band-aid for a wound that needs actual healing.

The people behind movements like Appstinence recognized something important: we can't algorithm our way out of loneliness. At some point, you have to actually talk to another human being. You have to be vulnerable. You have to risk rejection. You have to be boring and messy and real.

That's hard. And it's increasingly rare. So when someone points out that an AI friend might actually be making things worse, not better, it creates a moment of clarity that's contagious.

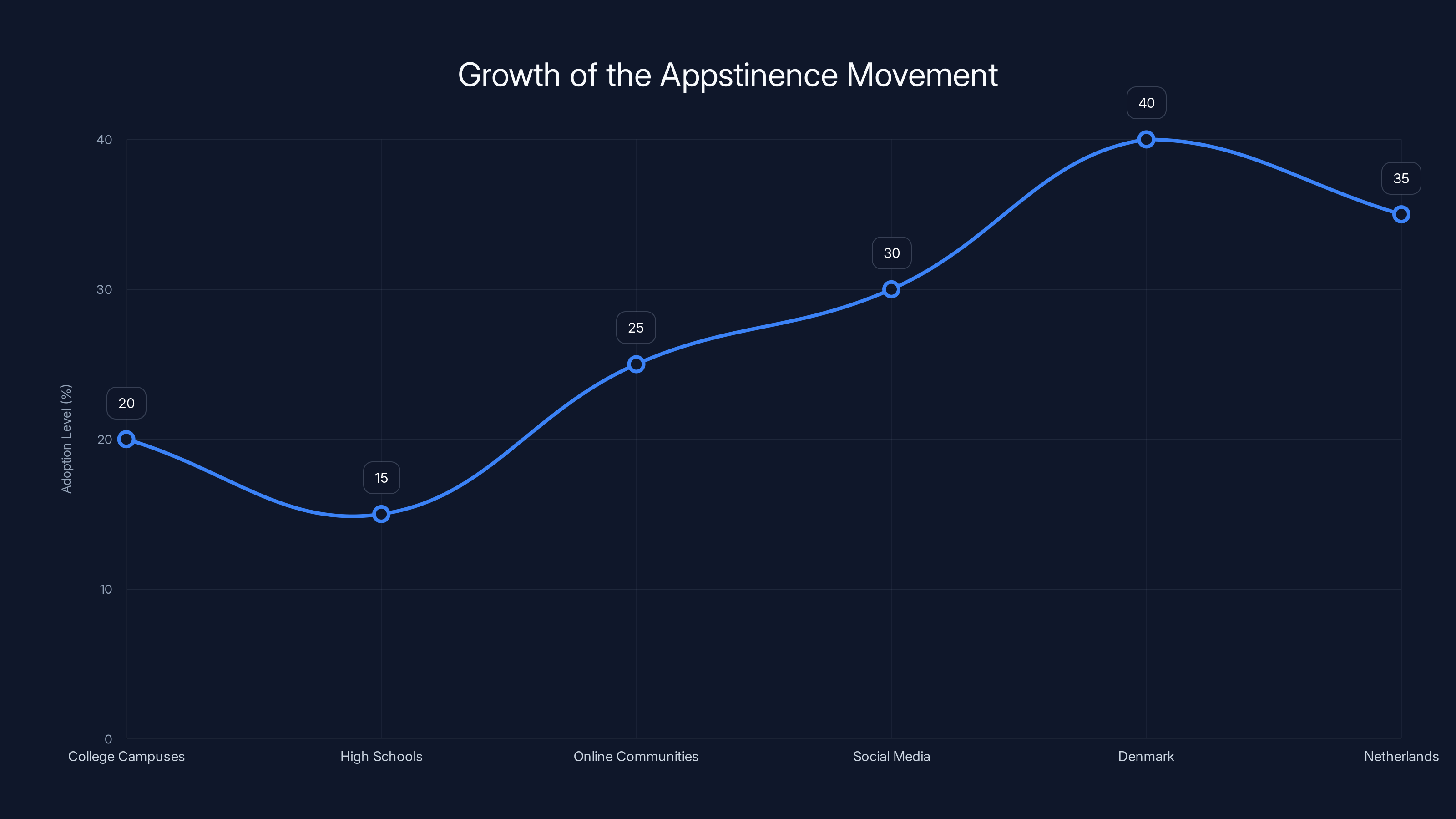

The Appstinence movement initially spread through college campuses and gained significant traction in Denmark and the Netherlands due to their cultural skepticism towards technology. (Estimated data)

What Appstinence Actually Is (And Isn't)

Appstinence isn't a monastery. It's not about moving to the woods and renouncing all technology. It's not even about hating apps or thinking Silicon Valley is evil.

If you strip away the branding, Appstinence is about one core idea: intentionality. It's the radical notion that you should think about the apps and tools you use before you use them, rather than letting them think for you.

The name itself is clever because it plays with expectation. When you hear "abstinence," you think of restriction, deprivation, saying no. But the actual pitch is something different. It's about saying no to things that don't serve you so you can say yes to things that do.

The core philosophy breaks down like this:

First, there's the recognition that our attention is finite. Every hour you spend in an app is an hour you're not doing something else. That seems obvious, but it's worth stating because the design of most apps deliberately makes you forget this trade-off.

Second, there's the understanding that some technologies are designed to exploit psychological vulnerabilities. Infinite scroll isn't a neutral feature—it's engineered to make you keep scrolling. Notifications aren't helpful reminders—they're behavioral triggers. Once you see these patterns clearly, using them feels different.

Third, and this is the important part, there's the belief that opting out is possible and actually preferable. Not everyone needs an AI friend. Not everyone needs to be on every platform. Not everyone should optimize their life for engagement metrics.

What makes Appstinence different from previous tech criticism is that it's not moralistic. Nobody's saying you're bad for using apps. The people driving this movement are themselves extremely tech-literate. Many work in tech. They understand that apps aren't inherently evil—they're tools with built-in incentive structures.

The message isn't "technology is bad." It's "some technology is designed to be bad for you, and you deserve to know that." It's the difference between regulation and education.

And when you educate people, especially young people who've internalized the idea that being online is non-negotiable, something shifts. The possibility of opting out suddenly feels real.

The Psychology Behind Rejecting AI Companions

There's something fascinating happening in the psychology of AI companion rejection, and it reveals something deep about how humans actually work.

When researchers and therapists started examining why people who tried AI companions often abandoned them, the reasons weren't what they expected. It wasn't that the AI was bad at conversation—in many cases it was quite good. It wasn't that people missed features. It was something more fundamental.

Using an AI friend made people feel worse about their loneliness, not better.

This is the opposite of what was promised. The pitch was that AI companions would reduce loneliness. Instead, many people reported that they intensified it. Why? Because having a relationship with something that isn't actually alive creates a very specific kind of emptiness.

Human brains are wired to recognize authenticity. We pick up on micro-expressions, timing patterns, genuine investment. When you're talking to an AI, some part of your brain knows that the other entity doesn't actually care about you. It's not malice—it's just the nature of the relationship. You can't be in a one-way relationship and feel genuinely connected.

Furthermore, AI companions create a false economy of effort. Real friendship requires vulnerability and risk. You have to be willing to be boring, or annoying, or to say the wrong thing. Real people sometimes don't respond to your messages. Real people get tired or distracted. Real people disappoint you.

An AI friend removes all that friction. Which sounds great until you realize that the friction is the whole point. The risk and vulnerability are what make connection meaningful. A relationship that requires no emotional risk provides no emotional reward.

There's also something about the design of AI companions that reveals the loneliness they're supposed to solve. They're available 24/7. They never get tired of talking to you. They remember everything you tell them. In a weird way, this intensity is a mirror of desperation. Why would you need a friend who's constantly available? Because you have no other friends. Why would you need a friend who never forgets anything? Because you have nobody else to share your life with.

Young people understood this intuitively. Maybe they couldn't articulate it perfectly, but they felt it. And once they felt it, they started asking bigger questions: What else is designed to feel good but actually make me feel worse? What other tools am I using that are engineered to keep me coming back rather than to genuinely help me?

That's where the real shift happens. When you see the AI friend for what it is—a reflection of your loneliness designed to keep you using a product—you start seeing everything else differently too.

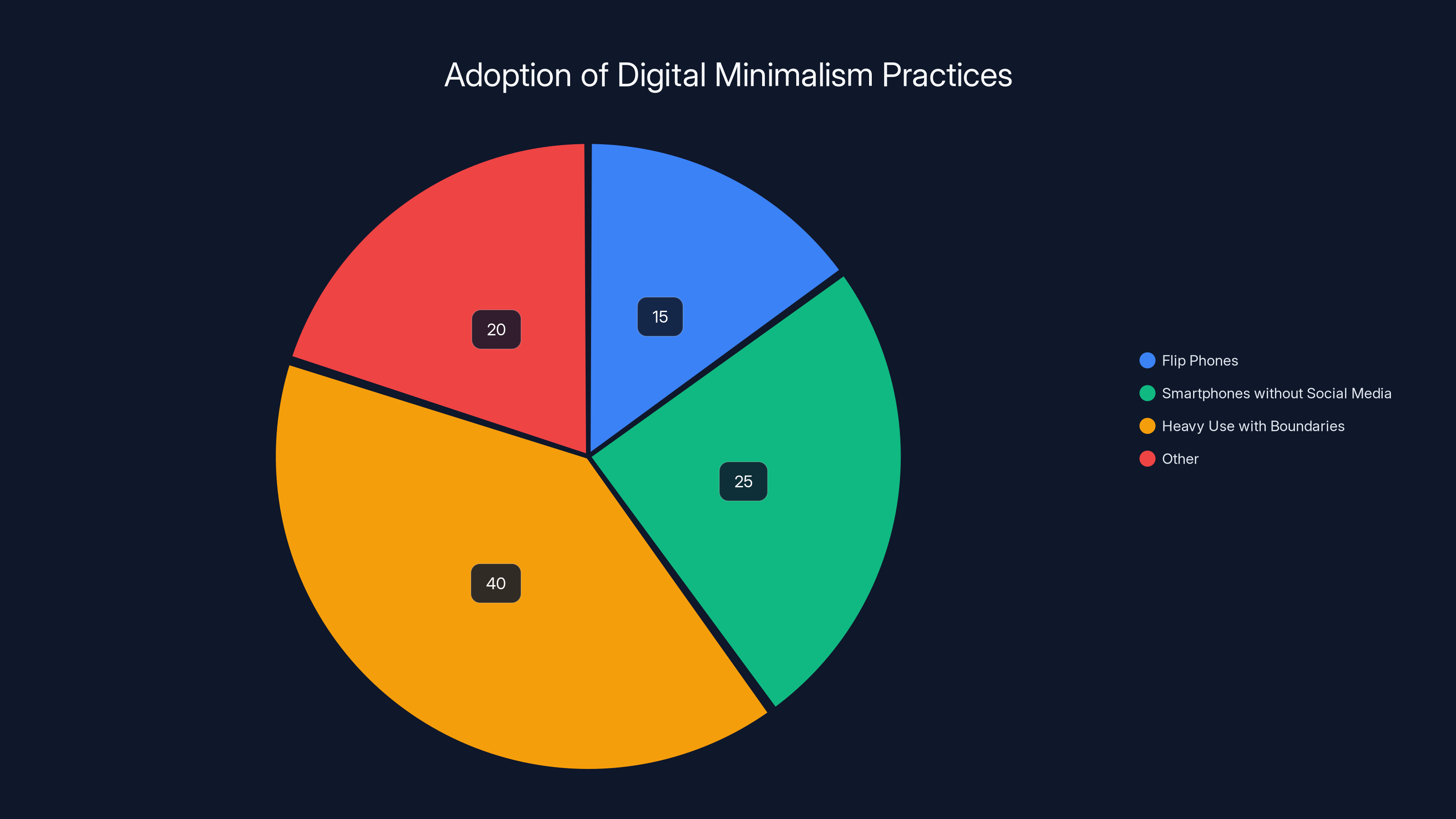

Digital minimalism manifests in various forms, with many users opting for smartphones without social media or setting clear boundaries for tech use. (Estimated data)

The Mental Health Connection

Let's talk about something that doesn't get nearly enough attention in tech discussions: what does constant digital engagement actually do to the teenage brain?

The neuroscience here is becoming clearer every year, and it's not cheerful. When you're using apps designed to trigger dopamine responses—like every social media platform—you're basically practicing addiction. Your brain becomes calibrated to expect immediate rewards. Delayed gratification feels impossible. Boredom becomes unbearable.

This isn't a moral failing. It's neurobiology. Your brain is literally being shaped by the tools you use.

Now add AI companions to the picture. You've got a product that's specifically designed to be engaging, rewarding, and always available. It's like putting someone on a schedule of intermittent rewards but removing the intermittent part—you get consistent reward for engaging with the product.

For people with depression or anxiety, this can be particularly insidious. Depression often involves social withdrawal. An AI friend makes that withdrawal feel manageable. You can stay isolated while feeling like you're maintaining a relationship. You can avoid the risk and vulnerability that real connection requires, which is exactly what depression whispers you should do.

But the withdrawal makes the depression worse. And the AI friendship removes the motivation to break out of it. It's a feedback loop that goes in the wrong direction.

Anxiety works similarly. If you're socially anxious, a human friend is scary. They might judge you. They might not like you. They might leave. An AI friend eliminates all those risks. But avoiding the anxiety-provoking situation is exactly how anxiety gets worse. You reinforce the belief that social interaction is dangerous. So the anxiety stays or intensifies.

This is why mental health professionals started paying attention to the anti-AI-friend movement. It wasn't coming from Luddites or doomers. It was coming from therapists and counselors who were seeing real people get worse after using AI companions.

The paradox of mental health treatment is that it usually involves doing the thing that makes you anxious. You get anxious about something, so you avoid it, which makes the anxiety bigger. Real healing comes from approaching the anxiety, tolerating it, and discovering that it doesn't kill you.

AI companions short-circuit this entire process. They offer the comfort of a relationship without the challenge of connection. And when it comes to mental health, that comfort is often the worst thing you can offer.

So when young people started saying "no, I don't want an AI friend," what they were often saying was: "I want to get better, not feel better right now." That's a distinction with real wisdom in it.

How the Movement Started and Where It's Growing

Every social movement has an origin point, and Appstinence's origin story is weirdly wholesome for something born on the internet.

It started because a small group of Gen Z people—mostly in college—were talking to each other about their phone usage. They noticed patterns. They noticed that despite having unlimited social connection, they felt more isolated. They noticed that breaking up with their apps actually made them happier, but doing it alone was hard because all their peers were still on the apps.

So they decided to make it a collective project. Not a shaming campaign or a purity test, but a genuine attempt to figure out what intentional technology use could look like for their generation.

The messaging was always careful. The goal was never to say "technology is bad." It was to say "you deserve to choose how much technology you use." That's it. That's the radical thing.

Where did it spread?

First, college campuses. This makes sense because college is where young people suddenly have a lot of autonomy over their time and their technology use. They're old enough to see the patterns but young enough to still feel like change is possible.

Then to high schools. Then to online communities. Then, inevitably, to social media itself—the irony of spreading an anti-app message on apps wasn't lost on anyone, but it was also pragmatic.

The movement has especially gained traction in places where there's already ambient awareness of tech's darker sides. Countries like Denmark and the Netherlands, which have a strong cultural tradition of questioning technology adoption before embracing it wholesale, saw the movement take root earlier and stronger.

But interestingly, the growth has been somewhat self-limiting. As Appstinence has become more visible, some people have turned it into a status symbol—having a flip phone or a phone without social media as a marker of superiority. That's not the point, and the original organizers have been pretty clear about that.

The actual spread looks less like a viral moment and more like a growing recognition that the emperor has no clothes. As more people talk about their phone usage without shame, more people start noticing their own usage. It becomes harder to deny that something's off.

The most interesting part of the movement's growth isn't the media coverage—though there's been plenty of that. It's the shifting baseline of acceptable behavior. A few years ago, not being on social media was weird. Now, it's increasingly normal. Having limited app usage is no longer something you apologize for.

Estimated data shows a correlation between increased social media use and higher reported loneliness levels among Gen Z over the past decade.

The Real Problem with AI Companions

Let's move past the psychology and get into the technical reality of why AI companions are fundamentally limited as friendship replacements.

An AI chatbot, no matter how sophisticated, doesn't have stakes in the relationship. It doesn't have a bad day that makes it distant. It doesn't have other friendships that sometimes take its attention. It doesn't grow or change over time. It doesn't remember last week's conversation in the way that shapes how it sees you now.

Real friendship involves mutual witness. You see each other change, struggle, succeed. You remember the context of the other person's life and adjust accordingly. You sometimes say no. You sometimes disappoint. And you do these things because the other person is worth the effort.

An AI companion can simulate these things, but it's simulation. The algorithm will appear to remember your struggles, but it doesn't actually care. It will appear to be interested in your success, but that interest isn't genuine. It's pattern matching and response generation.

Now, you might say: does it matter if the interest isn't genuine if it makes you feel better? And maybe in tiny doses, it doesn't. But relationships aren't consumed in tiny doses. If you're using an AI companion because you're lonely, you're using it regularly. You're building a pattern. And the pattern is practicing loneliness while pretending not to be lonely.

There's also the business model problem. Every AI companion on the market operates according to a simple incentive structure: keep the user engaged. This means the AI will be designed to be maximally engaging, not maximally helpful. The optimal AI friend is the one that makes you come back most often, not the one that helps you build real relationships.

This creates bizarre dynamics. The AI will tend to support whatever you're doing, even if what you're doing is isolating yourself. It will be endlessly validating, even when actual friends would say, "Maybe you should talk to someone." It will never challenge you, never push you to grow, never do what a real friend does.

And perhaps most importantly, using an AI companion takes up the mental and emotional space that you'd otherwise need to fill with real relationships. You only have so much relational capacity. An hour with an AI friend is an hour you're not working up the courage to text an actual human.

The rejection of AI companions isn't anti-technology. It's pro-human. It's the recognition that some of the most important things in life require friction, risk, and the presence of another conscious being who actually gives a shit about you.

Digital Minimalism as a Lifestyle Philosophy

What started as "okay, maybe I'll use my phone less" has evolved into something more coherent and philosophical: digital minimalism.

Digital minimalism is basically the idea that your technology should be intentional, not default. You choose which tools serve you and which ones you allow access to your time and attention. You're not trying to avoid technology—you're trying to use it purposefully.

This is different from digital detox, which is usually temporary. You take a detox break, you reset, and then you go back to your normal relationship with technology. Digital minimalism is permanent. It's a different way of living.

The philosophy has a few core principles:

First, technology is a tool, not a necessity. Just because something is possible doesn't mean you need to do it. Just because you can have an AI friend doesn't mean you should.

Second, your attention is your most valuable resource. Tech companies know this, which is why they're willing to spend billions to capture it. If you're not being intentional about who gets your attention, then you're giving it away for free.

Third, friction can be good. Removing all friction from your life sounds great until you realize that friction is what creates meaning. The effort you put into a relationship makes it matter. The difficulty of creating something makes it valuable.

When you start thinking about technology this way, your choices change. You stop asking "What's the latest tool?" and start asking "Do I need this? Does it serve my values? What's the cost?"

For some people, this means flip phones. For others, it means smartphones but no social media apps. For others still, it means using technology heavily but with clear boundaries. The specific implementation doesn't matter as much as the intention behind it.

What's interesting is how quickly digital minimalism has normalized. Five years ago, talking about deliberately limiting your technology use might've seemed eccentric. Now, it's increasingly mainstream. You'll find digital minimalism advice in major publications, incorporated into corporate wellness programs, discussed in schools.

Part of this is that digital minimalism produces measurable results. People who practice it report better sleep, less anxiety, improved focus, more meaningful relationships. These aren't subtle effects. They're noticeable changes that people can feel.

The lifestyle aspect is important too. Digital minimalism has become something people identify with. It's part of their sense of self. "I'm a digital minimalist" is now a status marker, especially among younger people. Ironically, this sometimes plays out on social media—people posting about how little they use social media. The contradiction is real, but so is the underlying value.

Where this gets interesting is in the implications for technology design. If digital minimalism becomes mainstream enough, then tech companies face a real problem: how do you build something people want to use less of? How do you create value while respecting people's time and attention?

Some companies are actually trying to answer that question. They're building tools designed to reduce usage, not increase it. Apps that help you use other apps less. Notifications that are genuinely important rather than manipulative. Interfaces that respect your attention rather than exploit it.

These are niche products right now, but they're growing. Because it turns out that when you build technology with the user's actual wellbeing in mind, some people want to use it. Revolutionary concept.

Estimated data suggests that increased loneliness and lack of authenticity are the primary reasons for rejecting AI companions, highlighting the importance of genuine human connection.

The Anti-AI-Friend Movement's Broader Implications

On the surface, rejecting AI companions seems like a small thing. One category of technology, rejected by one demographic. But zooming out, it's part of something much bigger.

It's a signal that the default assumption—that more technology, more connection, more options is always better—is being questioned. And it's being questioned by people who grew up with that assumption. They've had the full experience of endless digital connection and they're saying: this isn't it.

The implications ripple outward in interesting ways.

First, there's the implication for how we think about loneliness. For decades, the response to loneliness has been more technology: more ways to connect, more options for interaction. But maybe loneliness isn't a problem that technology can solve. Maybe it's a problem that requires community, investment, vulnerability, and time. The kind of things that are harder to scale, harder to monetize, but actually effective.

Second, there's the implication for AI development. If even Gen Z—the most tech-native generation ever—is saying no to AI friends, that's important feedback. It suggests that the trajectory of making AI more human-like, more emotionally resonant, more relationship-like might be the wrong direction. Maybe AI should stay weird and artificial and tool-like, rather than trying to pass as human.

Third, there's the implication for mental health treatment. For a while, there was a hope that AI therapists or AI counselors could help address the shortage of actual therapists. But if the research shows that AI companions can actually deepen loneliness and anxiety, then that approach needs reconsideration. Technology can support mental health treatment, but it can't replace human care.

Fourth, there's the implication for how we regulate technology. Regulators have been struggling with questions like: how do we prevent tech companies from exploiting attention? The anti-AI-friend movement suggests that education and cultural shift might be as important as regulation. When people understand what's happening, they can choose differently.

Finally, there's an implication for how we think about addiction and dependency. Tech addiction is real and measurable, but it's often framed as a personal failing—you have weak willpower, you're not disciplined enough. The anti-AI-friend movement reframes it: the problem isn't you, it's the design. And if the design is the problem, then the solution is to change the design or change how you interact with it.

Building Real Connections in an AI-Saturated World

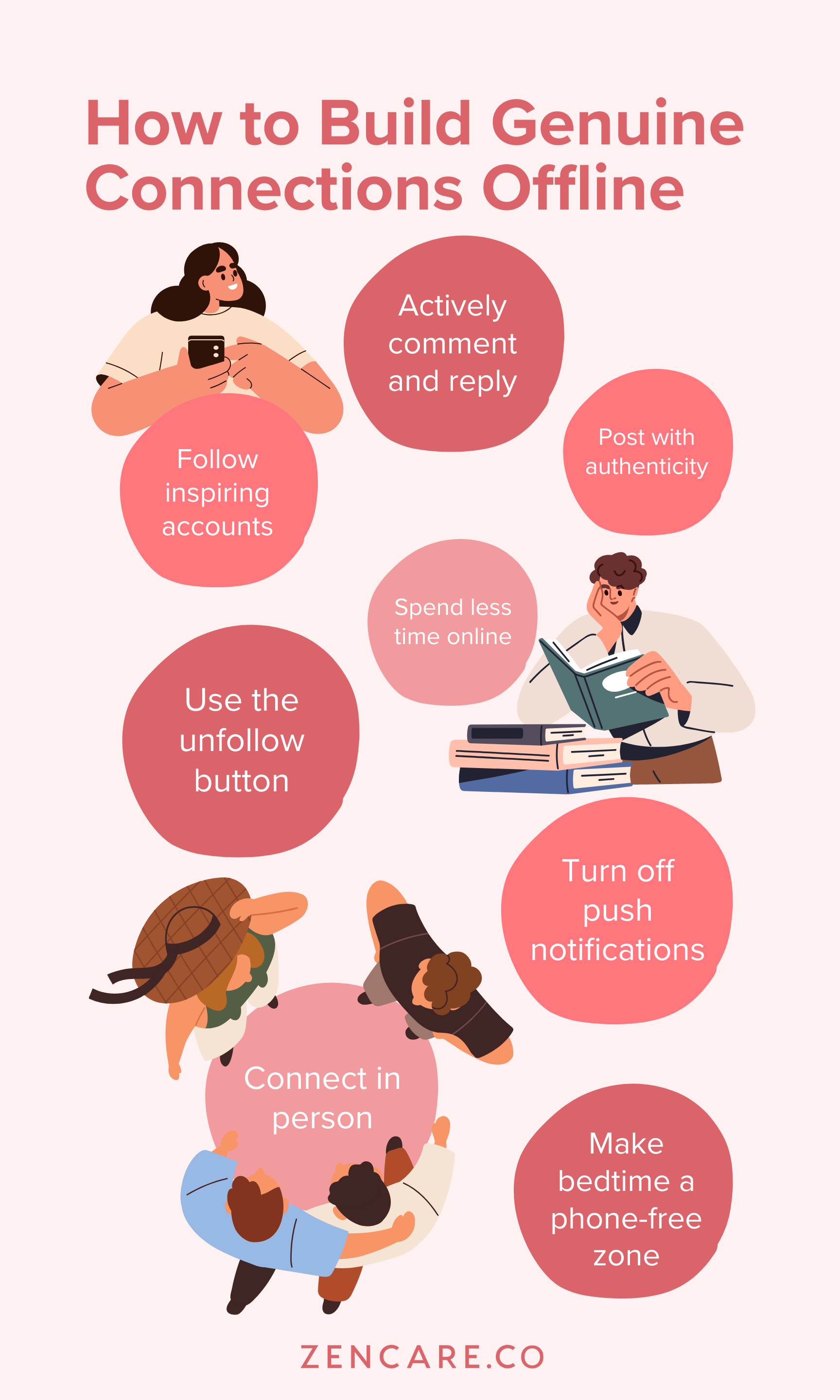

Here's the practical question that comes up: if AI friends are bad, what's the alternative? How do you actually build real connections when technology is everywhere?

The anti-Appstinence movement has some answers, though not all of them are techno-utopian.

First, there's the recognition that real connection requires presence. You have to show up, in person or online, as your actual self. Not your best self, your curated self, your optimized self. Your messy, uncertain, sometimes boring actual self.

This is harder than it sounds because we've trained ourselves to be curated. Social media taught us to present the highlight reel. But real friendship doesn't happen on highlight reels. It happens when someone sees you on a day when you're not performing, when you're tired or confused or just existing.

Second, there's the understanding that real connection is inefficient. An AI friend will be available at 3 AM when you can't sleep. A real friend might not answer. A real friend might say they need to go to bed. A real friend might be dealing with their own stuff. This sucks when you're lonely, but it's also what makes the friendship real.

Third, there's the recognition that some connections happen slowly. You don't become best friends with someone in one interaction. You become friends by seeing each other repeatedly, through different circumstances, over time. This contradicts the everything-fast-now culture that tech has promoted, but it's how humans actually bond.

So what does this look like in practice? The people in the anti-AI-friend movement talk about things like:

Joining actual communities—not online communities, real communities. Classes, clubs, volunteer organizations, faith communities, whatever. Spaces where you see the same people repeatedly and have to interact face-to-face.

Limiting your phone in social situations so you're actually present when you're with people. This sounds simple but it's surprisingly radical. Being physically present but mentally checked out is maybe worse than not being there at all.

Reaching out to people with vulnerability. Actually telling someone you're lonely, or confused, or struggling. The urge to find an AI companion often comes from not wanting to burden real people with your problems. But real people want to help. That's part of what makes friendship real.

Accepting boredom. Some of the best relationships happen when there's nothing special happening. You're just hanging out. The AI friend model is optimized for constant engagement and novelty. Real friendship is sometimes boring.

Investing in a few deep relationships rather than many shallow ones. Tech has trained us to think about quantity of connections. Real friendship is about quality.

The hard truth is that none of this is technology's job. Technology can facilitate these things—help you find communities, stay in touch with friends—but it can't do the actual work of building connection. That work requires you to be present, vulnerable, and willing to risk disappointment.

For a generation that's used to technology handling the hard stuff, this is a significant shift. But it's also why it's contagious. Once you experience the difference between AI-friend comfort and real-friend connection, you don't go back.

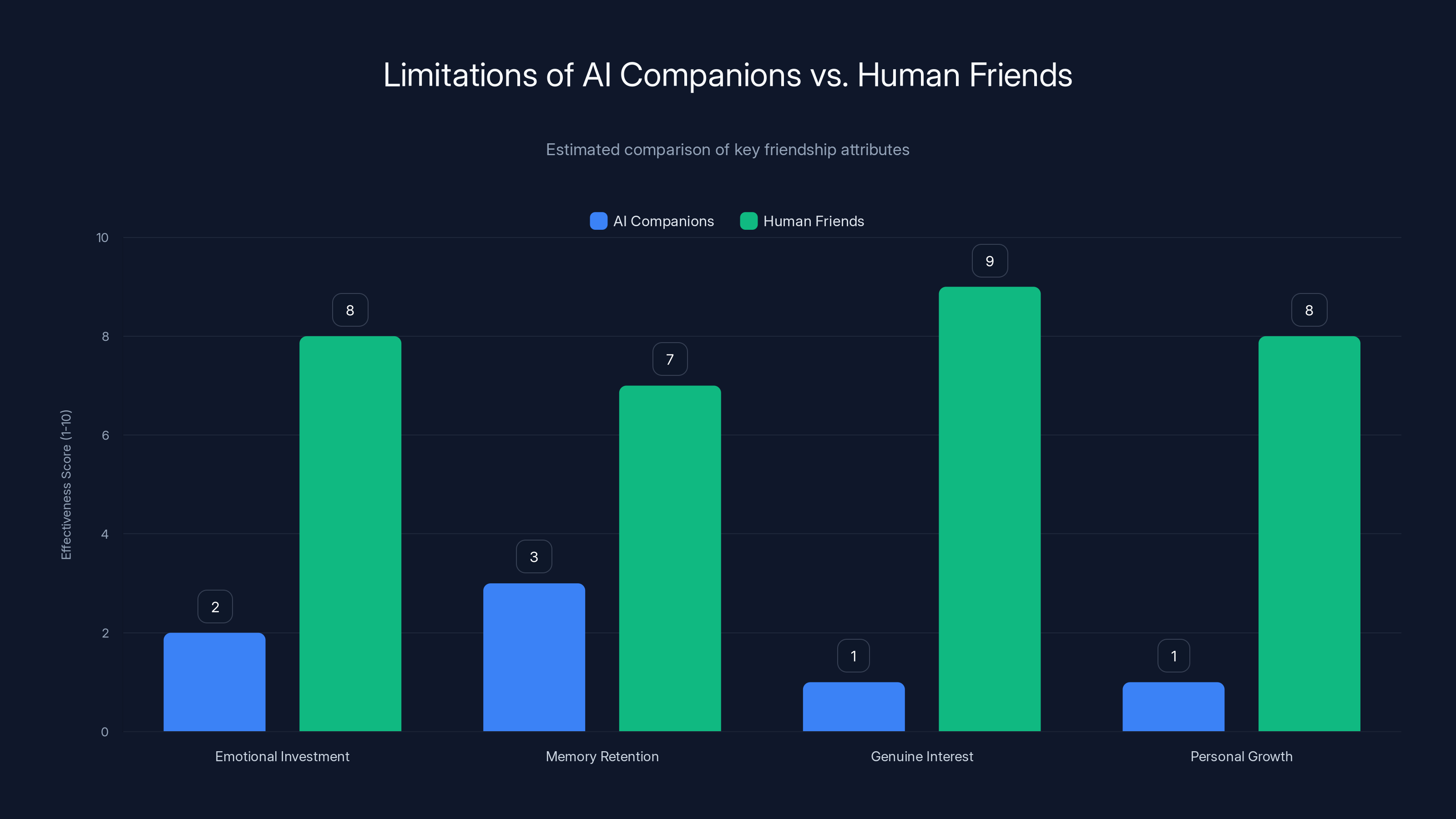

Human friends significantly outperform AI companions in emotional investment, genuine interest, and personal growth. Estimated data highlights the fundamental limitations of AI in replicating true friendship dynamics.

The Role of Education and Awareness

One of the surprising aspects of the anti-AI-friend movement is how much it's driven by education. Not in the traditional sense of classes or lectures, but in terms of raising awareness about how technology works and what it's designed to do.

When people understand that an app is designed to exploit their psychology, something shifts. You can't unsee it. Even if you continue using the app, you're more aware of what's happening.

The educational push has come from various directions. Some is from researchers and neuroscientists explaining what happens to the brain during heavy technology use. Some is from therapists and counselors talking about what they see in their practices. Some is from documentary filmmakers showing how technology is designed to be addictive.

But a significant amount is peer-to-peer. Young people talking to other young people about their experiences. Sharing what they've noticed. Passing along tips for using technology differently.

This peer education is powerful because it doesn't come with the moral judgment that adult criticism sometimes carries. When your friend tells you they're using their phone less and they feel better, that's credible in a way that a public health announcement isn't.

The education also includes teaching people to read their own behavior. If you're checking an app 50 times a day, why? What need is it fulfilling? Is it actually fulfilling it or just distracting from it? These are questions people need to ask themselves, and they can't be answered by anyone else.

There's also education around the business models of technology. When people understand that they're not the customer of social media platforms—they're the product being sold to advertisers—it changes how they think about using the platforms. They understand that every design choice is optimized to keep them engaged, not to help them.

This understanding is spreading to younger and younger people. Kids in high school now are increasingly aware of this stuff. They're making more intentional choices about technology from the beginning rather than adopting everything and then trying to back away later.

The challenge is scaling this education. Not everyone has access to good information about technology. Not everyone has peers talking openly about these issues. The movement is growing but it's still somewhat concentrated in educated, online spaces.

The Tech Industry's Response

How has the tech industry responded to the anti-AI-friend movement? It's complicated and worth examining closely.

Some tech companies have responded with what you might call "wellness washing." They've added features that let you limit your app usage, set notification reminders, track your screen time. These are genuinely useful features, but they also serve a secondary purpose: they make it seem like the company cares about your wellbeing, which makes it easier to justify using the app.

Other companies have doubled down on AI companions, betting that the problem isn't the concept but the execution. If we can just make the AI smarter, more empathetic, more helpful, then people will want to use it. This might be true, or it might be addressing the wrong problem.

Some companies have responded by building tools that actually support digital minimalism. Apps that help you use your phone less, that reduce notifications, that encourage offline time. These are niche products but they're growing.

There's also been a shift in rhetoric. Tech companies are increasingly using the language of intention and mindfulness. Instead of "maximize engagement," the pitch is "improve your experience." This might represent a genuine shift in how they think about their products, or it might just be smarter marketing.

What's notable is that the tech industry hasn't found a way to dismiss the anti-AI-friend movement as irrelevant or wrong. They can't because it's resonating with the people who are most valuable to them—young, educated, tech-native people.

The industry is also watching what happens. If the anti-AI-friend movement grows and scales, it could actually change how technology is designed and deployed. Companies might start building with the assumption that people want to use their products less, not more. That's a fundamental shift.

The Future of AI and Human Connection

So where does this go? What happens to AI development if a growing number of people are explicitly rejecting AI companions?

One possibility is that AI companions remain niche products for people who want them, but don't become mainstream. They exist the way some people use therapist bots or mood-tracking apps, but they don't become the default way people address loneliness.

Another possibility is that AI development shifts direction. Instead of trying to make AI more human-like and companion-like, maybe the focus becomes making AI better at facilitating human connection. Tools that help you stay in touch with friends. Tools that help you find communities. Tools that support human-to-human relationships rather than replacing them.

There's also the possibility that the movement continues to grow and creates actual pressure on how technology is regulated and designed. If enough people decide they don't want AI friends, companies might stop trying to make them.

But there's something deeper here about what the anti-AI-friend movement signals about the future. It's a signal that we can choose differently. That the trajectory tech has been on—toward more immersion, more engagement, more replacement of human activity with digital activity—isn't inevitable.

It's possible to step off that trajectory. It's possible to say: no, this is enough. We need something different. And when enough people say that, it becomes real.

The interesting part is that this might be the first time a generation has collectively rejected a technology that was supposed to solve a major problem. Usually technology adoption is pretty automatic. But Gen Z is saying: we see the problem, we see the proposed solution, and we're saying no.

What they're saying yes to instead is harder to achieve, requires more effort, and can't be scaled or automated. Real human connection. Presence. Vulnerability. Time.

In a culture that's been obsessed with efficiency and optimization, that's a radical move.

Practical Steps for Stepping Back from AI Dependency

If you're reading this and thinking, "okay, I get it, but how do I actually do this?" Here are some concrete steps that people in the movement have found helpful.

Step one is audit and awareness. Spend one week paying attention to your technology use without changing anything. Notice when you reach for apps. Notice how you feel before and after. Notice what you're avoiding by using technology.

Step two is identify the replacements. You're using AI friends or endless scrolling because you're trying to fulfill something. Loneliness, boredom, anxiety, restlessness. Before you remove the behavior, identify what you're actually craving.

Step three is small reductions. Don't try to go cold turkey. Remove one app. Set one notification boundary. Set one phone-free time. Let yourself get used to it.

Step four is fill the gap intentionally. The time you used to spend on your phone is now available. What do you want to do with it? Read? Talk to someone? Walk? Practice a hobby? Sit with your thoughts? Be intentional about what fills that space.

Step five is community. Find people who are doing similar things. This could be online communities—yes, the irony is real—or actual in-person communities. Knowing you're not alone in this makes it way easier.

Step six is persistence and self-compassion. You'll probably backslide. You'll probably have days where you pick up your phone way too much. That's normal. The point isn't perfection, it's intention.

The movement has also identified some practical tools that help:

Phone settings that prevent installation of problematic apps. Separate devices for work and personal use. Notification controls that actually work. Grayscale displays that make phones less appealing. Alarm clocks instead of phone alarms so you don't have your phone by your bed.

Some people go further and use parental control apps to limit their own access. Some switch to flip phones. Some delete apps regularly and then reinstall them when they want to use them—the friction of reinstalling is enough to break the automatic reaching-for-the-phone pattern.

What works varies by person. The point is that if you're intentional about it, you can reshape your relationship with technology.

The Cultural Shift Happening Right Now

What makes this moment interesting is that it's not about technology getting worse. The apps aren't more addictive than they were five years ago. AI isn't more dangerous. The shift is cultural.

Young people have simply decided that the deal—trade your attention and time for free services and convenience—is no longer worth it. And that collective decision is powerful.

You can see this shift in small ways. In fashion, there's the rise of "dumb" clothes that don't track you. In phone design, there are companies making phones that deliberately don't have all the features of smartphones. In social norms, being offline is becoming not weird but aspirational.

You can also see it in who's succeeding and who's struggling in tech. Companies built on the model of endless engagement are facing challenges. Companies built on the model of solving specific problems are growing. Companies that help people use technology less are starting to exist.

Part of this might be cyclical. Maybe in five years there will be a backlash to the backlash and everyone will be back on their phones. But something deeper might be happening. A genuine recognition that the way we've been living with technology isn't sustainable, isn't healthy, and isn't actually what we want.

The anti-AI-friend movement is just one expression of this shift. But it's a clear, bold expression. It's saying: we reject this specific vision of the future. We want something different.

What that different thing looks like is still being determined. But it's clear that it involves less technology, not more. More human connection, not less. More intention, not more default.

And it's being driven by the generation that had every reason to accept technology uncritically but chose to question it instead.

What This Means for You

We should probably spend some time talking about what the anti-AI-friend movement means if you're not part of a college campus community or an online movement. What does it mean for your life, right now?

First, it means you have permission to question your technology use. You don't have to accept the default. You don't have to have all the apps everyone else has. You don't have to be reachable 24/7. These are choices, not requirements.

Second, it means that if you're lonely, AI companions are not the answer. They might feel like the answer in the moment, but they're addressing the symptom, not the problem. The actual answer is harder and slower and requires real people. But it's real.

Third, it means that paying attention to how technology makes you feel is important. If an app or tool is making you feel worse even while you're using it, that's information. That's your brain and body telling you something.

Fourth, it means that you're not behind or missing out if you're not on every platform or using every tool. You might actually be ahead.

Finally, it means that the future of technology isn't determined. What gets built, how it gets designed, how people choose to use it—these things are still up for grabs. If enough people decide they want something different, something different gets built.

The anti-AI-friend movement is small right now, but movements start small. They start with individuals making different choices and talking about those choices. They start with culture shifting before markets follow.

FAQ

What exactly is an AI friend or AI companion?

An AI friend is a chatbot or conversational AI designed to simulate a friendship relationship. Unlike general-purpose AI assistants, AI companions are specifically engineered to be emotionally engaging, to remember your personal details, to be available 24/7, and to make you feel heard and validated. Examples include character.ai chatbots and some features of apps like Replika. The core promise is that they can help reduce loneliness by providing constant companionship and emotional support, though critics argue this creates pseudo-relationships that prevent real human connection.

Why are young people rejecting AI friends if they claim to reduce loneliness?

Young people discovered through experience that AI companions actually intensify loneliness rather than reduce it. The issue is that AI relationships lack reciprocity, authenticity, and genuine care. While an AI can simulate interest and validation, it fundamentally doesn't care about you because it's not conscious. This creates what researchers call a "pseudo-relationship"—one that feels momentarily good but ultimately leaves you feeling more empty. Additionally, having an AI friend removes the motivation to build real relationships, which are the actual antidote to loneliness.

What is Appstinence, and is it just about rejecting all technology?

Appstinence is a movement encouraging intentional technology use—using apps and digital tools deliberately rather than defaulting to them automatically. Despite its name suggesting abstinence, it's not anti-technology. It's pro-intentionality. The movement recognizes that some apps are designed to exploit psychological vulnerabilities through infinite scroll, variable rewards, and other manipulation tactics. Appstinence advocates for understanding these designs and choosing consciously whether to use these tools, not necessarily rejecting all technology but using it with full awareness of its effects.

How does digital minimalism differ from previous "digital detox" trends?

Digital detox is usually temporary—you take a break and then return to normal usage. Digital minimalism is a permanent shift in lifestyle philosophy. It treats your attention and time as finite, valuable resources. Rather than seeking to restrict technology temporarily, digital minimalism asks: Which tools genuinely serve my values and goals? What's the actual cost of my technology use? Digital minimalism is less about guilt and more about intentional design of your life with technology playing a supporting, not central, role.

Can AI ever be helpful for mental health, or is the movement against all AI in mental health spaces?

The anti-AI-friend movement isn't against all uses of AI in mental health. AI tools that provide educational content, help you track mood patterns, send reminders to practice coping strategies, or facilitate access to human therapists can be genuinely helpful. The specific problem is AI companions or AI "therapists" that attempt to replace human therapeutic relationships. Mental health improvement fundamentally requires witnessing by another conscious being. AI can support that process, but it cannot replace it. The research is increasingly clear that AI companions can actually worsen depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal when used as a primary source of emotional support.

What should someone do if they're lonely but don't want to use AI companions?

The alternative to AI companionship is incremental real human connection. This might mean joining communities (clubs, classes, volunteer organizations, faith communities), reaching out to one person you'd like to know better, attending group activities, or even starting with lower-stakes online communities around shared interests. The key is accepting that real connection takes time, has friction, and requires vulnerability. You might feel more uncomfortable initially than you would with an AI friend, but the actual connection you build will be sustainable and meaningful. Even small actions—responding to a message, saying yes to an invitation, attending a group meeting—create momentum toward real connection.

Is the anti-AI-friend movement just a niche trend or is it becoming mainstream?

The movement has grown from a niche college phenomenon to increasingly mainstream awareness. Universities report more students with intentional tech boundaries. Schools are integrating digital wellness education. Tech companies are adding features to limit usage. However, it remains most visible in educated, online communities. The broader normalization of digital minimalism is happening, but mainstream adoption is still emerging. What's clear is that it's no longer considered eccentric or extreme to deliberately limit technology use or reject AI companions—this shift in baseline acceptability is significant.

What role do tech companies play in promoting or resisting this movement?

Tech company responses are mixed. Some have added genuine wellness features (screen time limits, notification controls). Others have engaged in "wellness washing," adding these features while maintaining fundamentally exploitative designs. Some continue building AI companions betting the execution will improve adoption. Others have shifted toward building tools that facilitate human connection rather than replacing it. The movement has created enough cultural pressure that companies can't simply dismiss concerns, but the underlying business models haven't fundamentally changed for most major platforms.

How can parents and educators support digital wellness without being preachy?

The most effective approach is modeling and education without judgment. Adults who are thoughtful about their own technology use, who admit when technology is negatively affecting them, and who make changes demonstrate that different choices are possible. For educators, teaching about how platforms work—the business models, the psychological manipulation, the design choices—gives young people agency to make their own decisions. Importantly, this education works best when it's not framed as "technology is bad" but rather "here's what's actually happening, and you get to choose."

The Real Question Underneath All of This

The anti-AI-friend movement raises a deeper question that goes beyond technology. It's asking: what do we actually want our lives to look like?

For a while, the answer seemed obvious. More connection, more options, more efficiency, more convenience. Technology delivered on those promises. And yet here we are, more connected and more lonely than ever.

So maybe the question needs to be different. Maybe it's not about having more, but about being present for what we already have. Not about optimizing every moment, but about accepting that some moments are slow and boring and that's okay. Not about never being alone, but about choosing solitude sometimes.

That's what the anti-AI-friend movement is really about. It's not anti-progress or anti-innovation. It's pro-human. It's saying: before we automate or optimize something, let's think about whether it's something worth automating.

Friendship is definitely something worth thinking twice about before outsourcing.

The movement is gaining momentum because people are tired. They're tired of performing for algorithms. They're tired of checking their phones. They're tired of feeling like they need to do more and have more and be more.

And they're discovering something that sounds simple but is actually revolutionary: real connection feels better. Presence feels better. Being bored with another person feels better than being endlessly entertained alone.

Once you experience that difference, it's hard to go back.

So the question isn't really whether AI companions are good or bad. The question is: what kind of human do you want to be? And what kind of life do you want to build?

If the answer involves other people, real presence, vulnerability, and time—then you probably don't want an AI friend. You want actual friends. You want community. You want to be seen.

And that's a choice that's available to you right now.

Key Takeaways

- Gen Z is deliberately rejecting AI companions after discovering they deepen loneliness rather than solve it

- Digital minimalism is shifting from niche trend to mainstream cultural movement with measurable mental health benefits

- Real human connection requires friction, vulnerability, and mutual care that AI cannot authentically provide

- The movement signals that technology adoption isn't inevitable—cultural choice and education can reshape how people interact with tools

- Tech companies face pressure to redesign products around wellbeing rather than engagement maximization

Related Articles

- The Offline Club: How People Are Fighting Phone Addiction in 2025

- The Dumbphone Paradox: Why Gen Z Can't Actually Quit Smartphones [2025]

- UK AI Copyright Law: Why 97% of Public Wants Opt-In Over Government's Opt-Out Plan [2025]

- Social Media Addiction Lawsuits: TikTok, Snap Settlements & What's Next [2025]

- TikTok Settles Social Media Addiction Lawsuit [2025]

- Meta's "IG is a Drug" Messages: The Addiction Trial That Could Reshape Social Media [2025]

![Why Gen Z Is Rejecting AI Friends: The Digital Detox Movement [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-gen-z-is-rejecting-ai-friends-the-digital-detox-movement/image-1-1769643537562.jpg)