Microscopic Autonomous Robots: Engineering the Smallest Autonomous Machine Ever Built

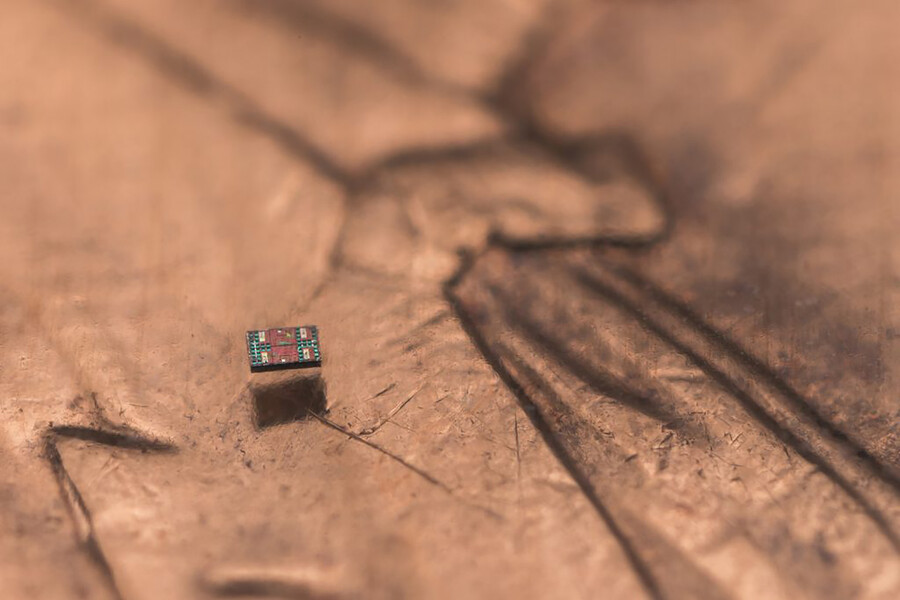

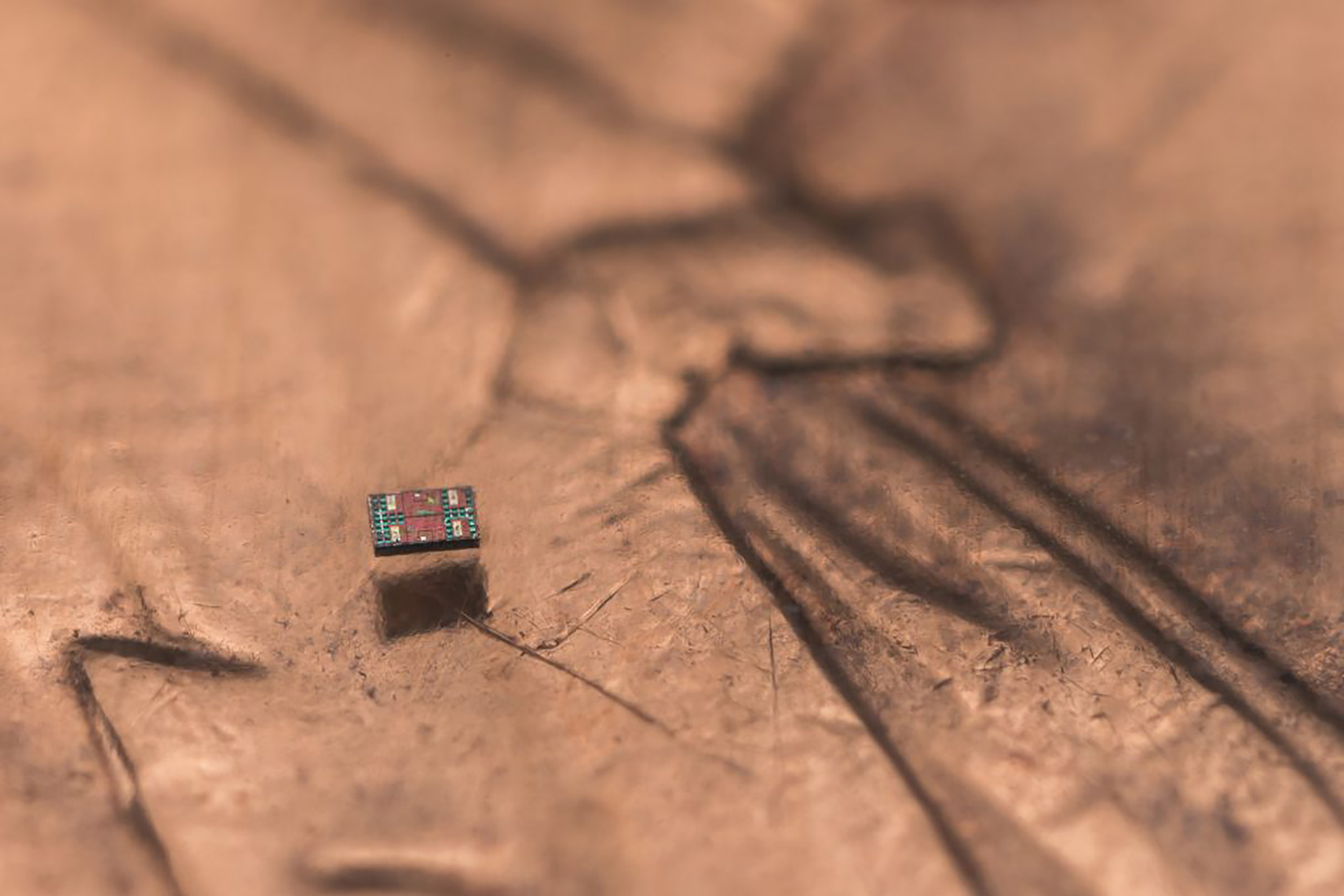

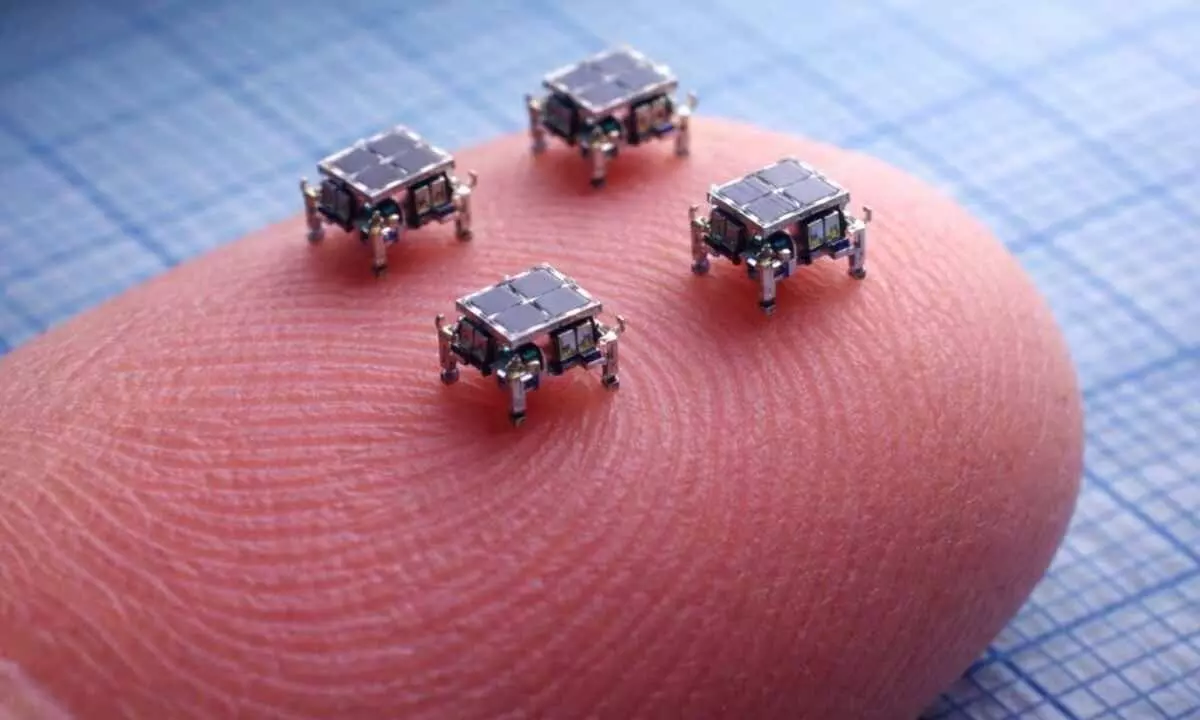

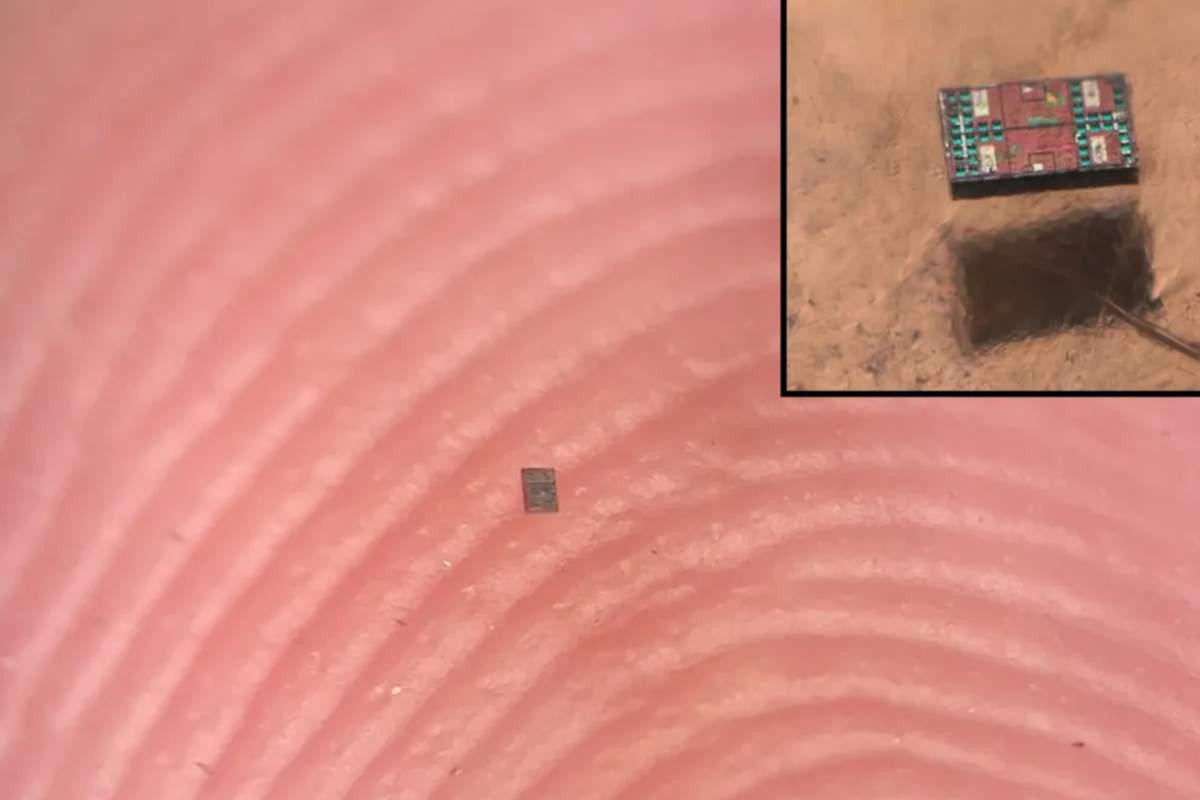

Last month, I was reading through a research presentation on microrobotics when something stopped me cold. A team from the University of Pennsylvania and University of Michigan had built a robot smaller than a grain of salt. Not a concept, not a simulation—an actual, functioning, autonomous robot measuring just 0.3 millimeters on its longest side.

I'll be honest, my first reaction was skepticism. How do you even fit a computer on something that small? How does it move? And honestly—who cares? But the more I dug into this, the more I realized something genuinely important was happening. This wasn't just a miniaturization achievement. It represented a fundamental rethinking of how robotics work at scales where the rules of physics completely change.

Over the past 40 years, engineers have tried and failed to build autonomous robots under 1 millimeter. The challenges are brutal. Small mechanical parts snap like toothpicks. Traditional motors don't work. Gravity, inertia—all the physics that governs normal-sized robots becomes irrelevant. Instead, you're dealing with viscosity, drag, electrostatic forces, and surface tension. It's like trying to engineer something to swim through honey using physics designed for water.

What these researchers did was abandon conventional robotics entirely. They didn't try to build tiny versions of normal robots. Instead, they invented something completely different—a new category of machine that exploits physics at microscopic scales instead of fighting against it. The result is something with implications far beyond satisfying engineering curiosity.

In this article, I'm going to walk you through how they did it, why it matters, and where this technology goes next. Because if you can build an autonomous robot smaller than a grain of salt, it changes what's possible in medicine, manufacturing, environmental monitoring, and sensing. And frankly, that's worth understanding.

TL; DR

- World's smallest autonomous robot: University of Pennsylvania and University of Michigan researchers created a fully autonomous robot measuring just 0.3mm, breaking a 40-year barrier in microrobotics as reported by I Programmer.

- Revolutionary propulsion system: Instead of moving parts, the robot generates electric fields to push charged particles, which drag water molecules (eliminating mechanical failure points) according to Wired.

- Powered by light alone: Solar panels generate just 75 nanowatts—less than 1/100,000th of a smartwatch's power—yet the robot operates continuously for months.

- Complete onboard computing: Includes processor, memory, and sensors on a sub-1mm chip, making it the first truly autonomous robot at this scale.

- Practical applications ahead: Medical monitoring, environmental sensing, micro-assembly, and collaborative swarm robotics—previously impossible at microscopic scales.

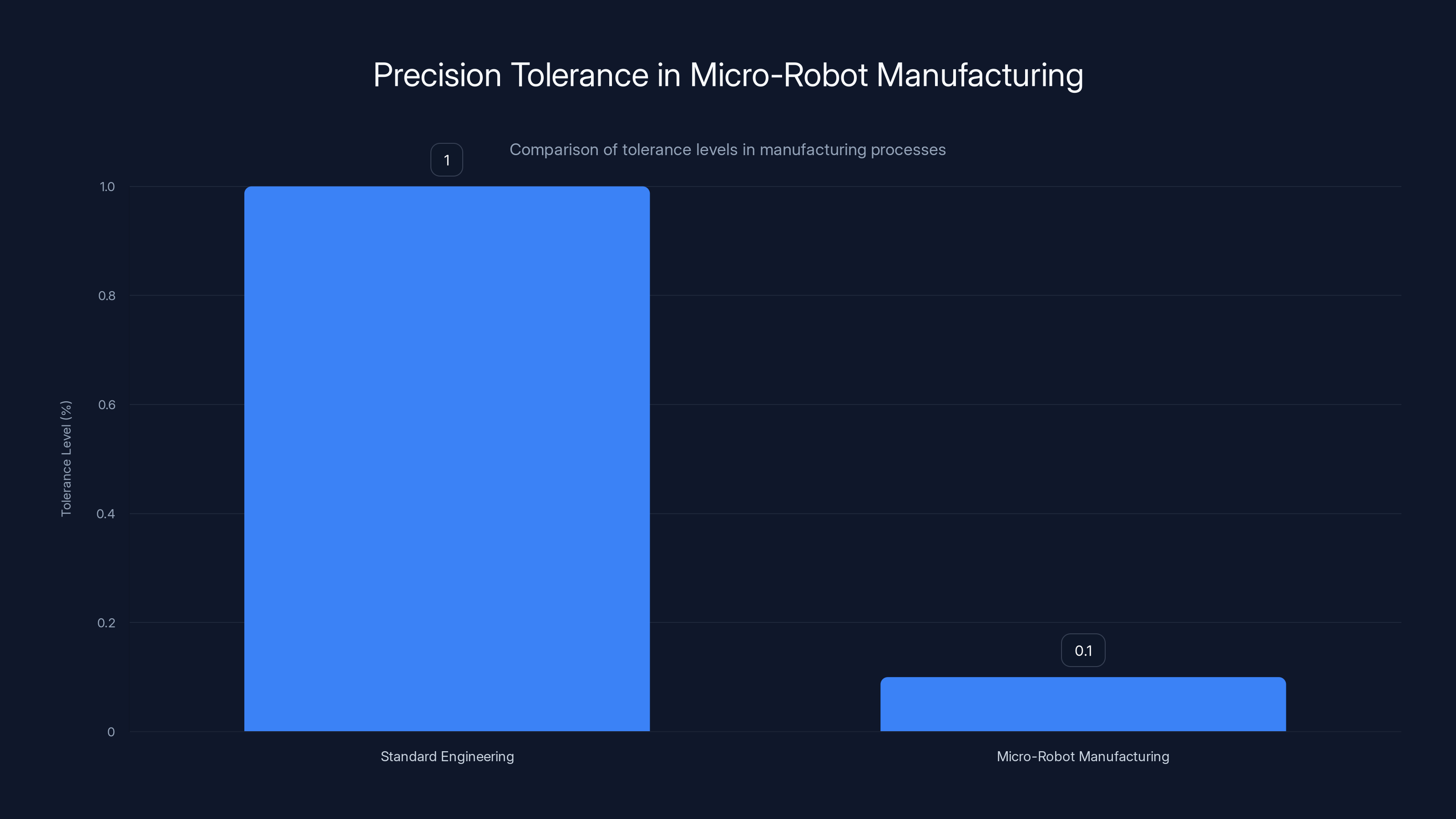

Micro-robot manufacturing requires a significantly tighter tolerance level of 0.1% compared to the standard 1% in typical engineering processes, highlighting the precision needed for these advanced technologies.

The Impossible Challenge: Forty Years of Failed Attempts

Miniaturization is seductive in engineering. Smaller devices promise greater precision, lower energy use, less material waste. But there's a wall that roboticists have been slamming into for decades: the 1-millimeter barrier.

Sounds absurd, right? A millimeter is tiny already. But think about what goes into a robot. You need mechanical components that move—actuators, joints, motors. You need power storage. You need sensors to perceive the environment. You need a brain to process that information and make decisions. Squeeze all of that into 1 millimeter, and suddenly you're not just dealing with manufacturing challenges. You're violating the laws of physics as you understand them.

Let me explain why conventional approaches fail at this scale.

The Viscosity Problem

When you're building a human-sized robot or even an insect-sized one, you think about movement in terms of Newton's third law: for every action, there's an equal and opposite reaction. A fish pushes water backward, propels itself forward. A robot with little legs kicks against the ground to move.

At microscopic scales, this completely breaks down.

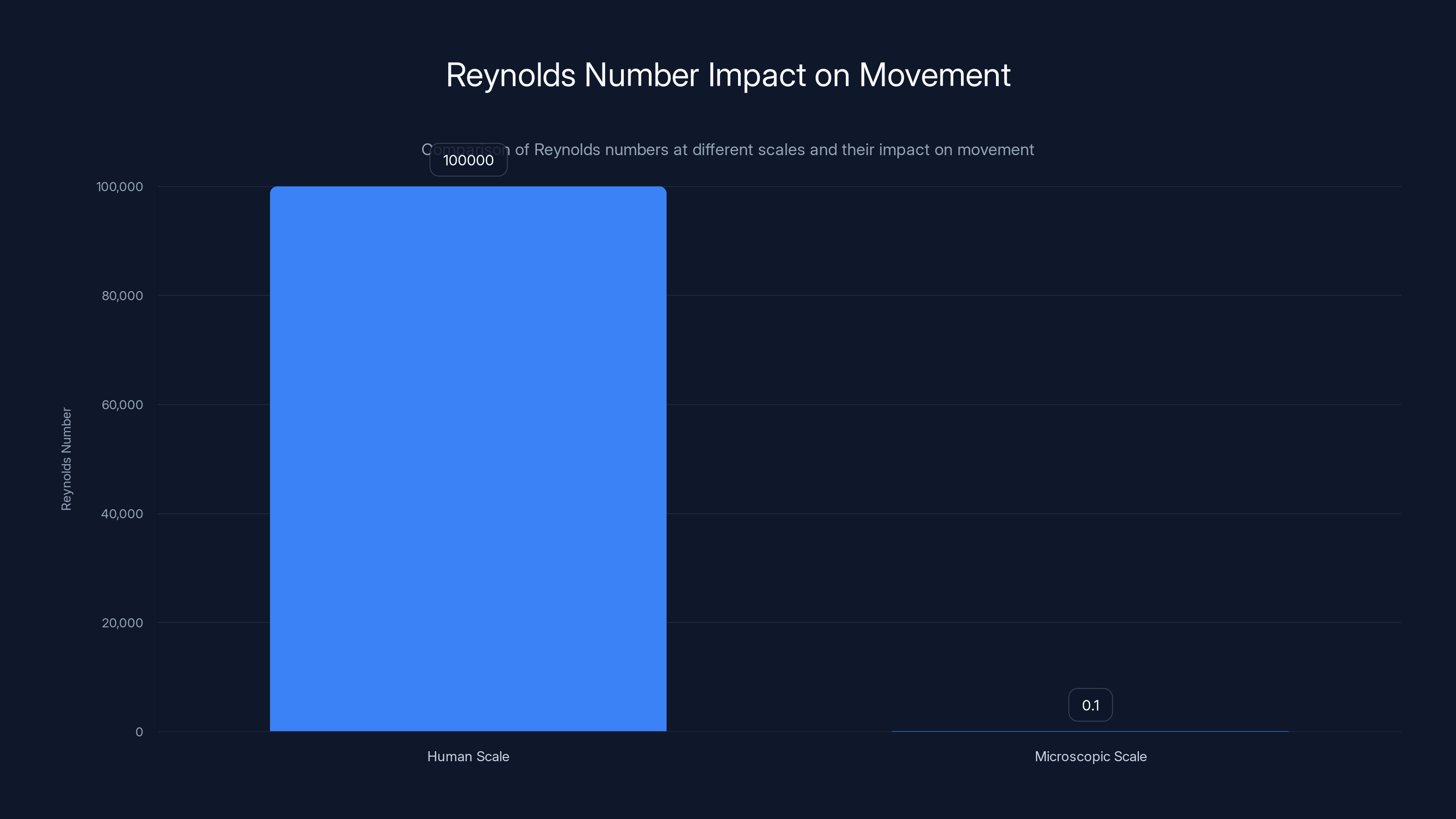

Water at that scale isn't a fluid anymore—it acts like viscous sludge. The Reynolds number (a dimensionless quantity describing the ratio of inertial to viscous forces) drops from thousands at human scales to fractions at microscopic scales. When you're 0.3 millimeters long, the drag forces are so overwhelming that tiny mechanical appendages can't generate meaningful thrust.

Imagine trying to swim through liquid asphalt. That's what it feels like for a microscopic robot trying to move its legs. The viscous drag completely overwhelms any force generated by mechanical motion. You could build the most precisely engineered micro-motor imaginable, and it would barely move the robot forward.

This is why previous attempts at sub-millimeter robotics hit a dead end. Engineers kept trying to miniaturize conventional approaches—tiny motors, tiny legs, tiny mechanical systems. It's like trying to make a car smaller by just shrinking every part proportionally. At some point, the engineering assumptions break down.

Manufacturing at the Microscopic Scale

Beyond physics, there's a brutal manufacturing problem. How do you build moving parts when those parts are 100 times smaller than a human hair?

Microfabrication has come a long way—we can now manufacture transistors at the nanometer scale—but creating mechanical components is different from creating electrical ones. Mechanical parts need to move without friction, without binding, without breaking. At microscopic scales, surface forces matter more than structural strength. A tiny robot leg is more likely to stick to adjacent materials through static forces than to smoothly articulate.

Then there's the assembly problem. How do you assemble something that small? Current approaches at extreme miniaturization rely on lithography and etching—essentially the same processes used to make computer chips. You can't hand-assemble a robot that's smaller than a cell nucleus.

For four decades, these compounding problems stopped progress. Researchers would announce breakthroughs in miniaturization every few years, but none could build a fully autonomous robot under 1 millimeter. The best they managed were either non-autonomous micro-robots (controlled by external magnets or wires) or robots that required external power or computation.

Previous Approaches and Their Limits

The closest anyone came involved magnetic control. Researchers built tiny robots and controlled them externally using magnetic fields—essentially puppeteering the device from outside. These weren't autonomous. They couldn't sense their environment or make independent decisions.

Others experimented with hybrid approaches: micro-robots that were tethered to external power supplies and computers. That defeats the purpose of building something that small. If you need cables and external power, you've lost the primary advantage of miniaturization—the ability to deploy multiple independent agents that operate without infrastructure.

The barrier wasn't one insurmountable problem. It was a cascade of interconnected problems, each compounding the others. Physics that governed normal robotics didn't apply. Manufacturing was a nightmare. Power generation was nearly impossible. And creating a computational system that could fit on a sub-millimeter device seemed like science fiction.

Then in 2024, a team decided to stop trying to miniaturize conventional robotics and instead invent an entirely new category of machine.

The Breakthrough: Rethinking Motion at Microscopic Scales

Mark Miskin is an assistant professor of electrical systems engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. He specializes in micro-systems and miniaturization. When he started this project five years ago, he wasn't trying to build a tiny version of an existing robot. He was asking a different question: What would a robot look like if it was designed from the ground up to exploit the physics of microscopic scales instead of fighting against it?

The answer was radical: no moving parts at all.

Electrokinetic Propulsion: Moving Water, Not the Robot

Instead of legs, fins, or propellers, Miskin's team developed something called electrokinetic propulsion. Here's how it works:

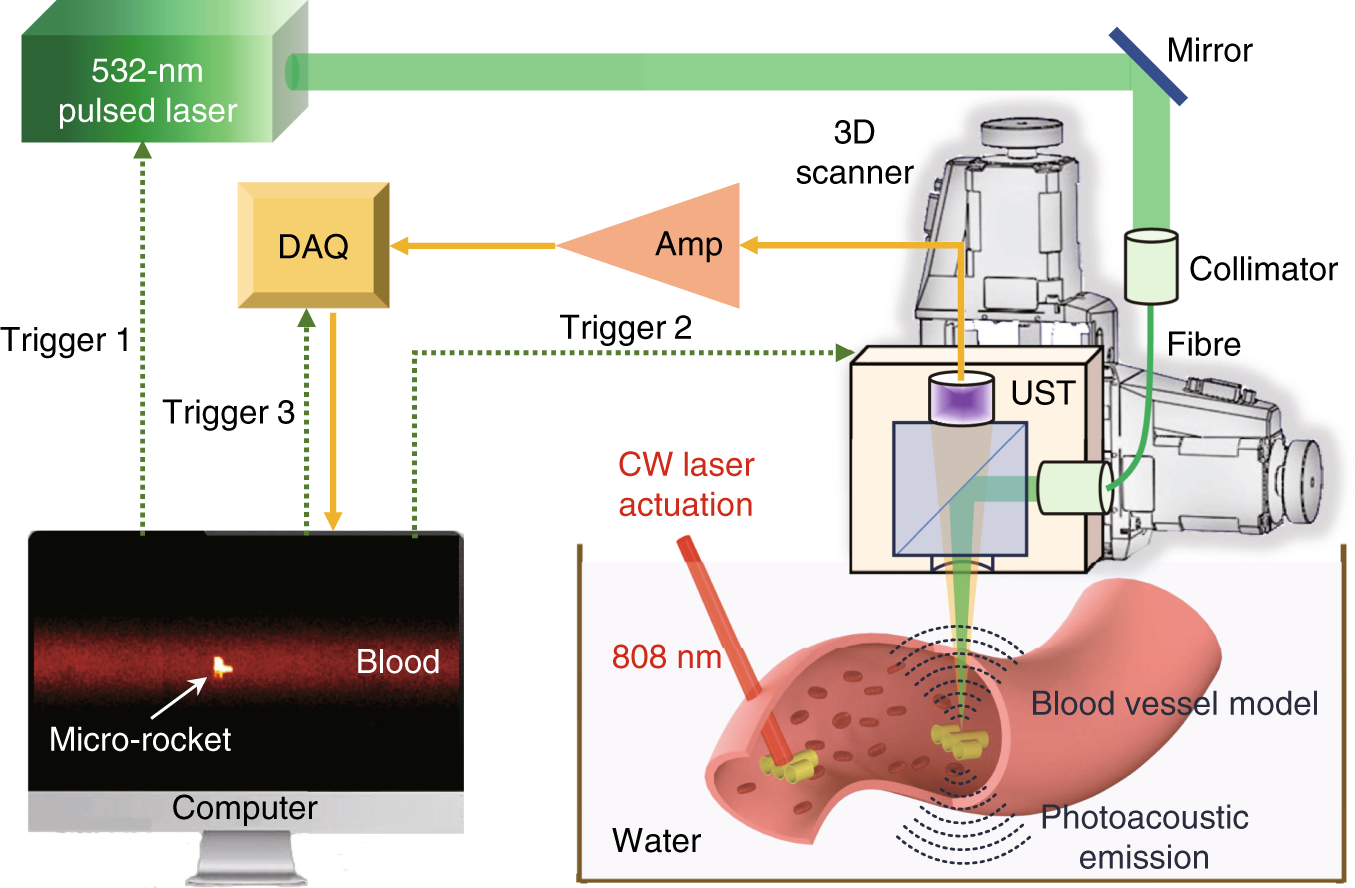

The robot generates a carefully controlled electric field around itself. This electric field pulls charged particles in the surrounding liquid—ions, charged molecules, whatever's in the water. As those charged particles move in response to the electric field, they drag water molecules along with them through a phenomenon called electrokinesis.

The net effect is genius: the robot doesn't push itself through water. The robot makes the water move around itself.

Think of it this way. Imagine you're standing in a river. You can't control the river's current, but what if you could generate a current around you that moves in the direction you want to go? The river flows past you, pushing you in that direction. That's the principle here.

At the microscopic scale where viscosity dominates everything, this is the optimal strategy. You're not fighting drag—you're exploiting it. You're not generating tiny mechanical forces that can't overcome viscous resistance—you're creating a flow pattern that carries the entire robot along.

The technical implementation is elegant. The robot uses patterned electrodes on its surface. By applying voltage across these electrodes, the team can create electric fields that move in different directions. Change the field pattern, and the water current changes direction. The robot can follow complex paths, turn sharp angles, even move in coordinated groups.

Why No Moving Parts Matters

Here's where the genius becomes obvious: without moving parts, the robot almost never breaks.

Mechanical failure is the enemy of miniaturization. Tiny gears strip. Micro-motors seize. Joints become stiff from manufacturing imperfections. With electrokinetic propulsion, there's nothing mechanical to fail. There are no moving parts, no bearings, no articulation points.

According to Wired, the robot can operate continuously for months. We're not talking about hours or days. Months. That fundamentally changes what's possible with microscopic robots. You could deploy them in an environment and they'd keep functioning, keep collecting data, keep operating autonomously for extended periods.

This durability advantage can't be overstated. Previous attempts at microrobotics always struggled with lifespan. Even if they worked initially, mechanical degradation would set in quickly. With electrokinetic propulsion, that's eliminated.

Speed and Maneuverability

The robot moves impressively given its size. It can travel one body length per second maximum—that's 0.3 millimeters per second. That might sound slow, but at the microscopic scale where viscosity is extreme, it's actually quite fast. For reference, a bacterium swims at roughly 20 micrometers per second. This robot is moving 15 times faster than bacteria.

More importantly, it's precise. By modulating the electric field, the researchers can make the robot follow specific paths. In demonstrations, they showed the robots moving in coordinated patterns, almost like a school of fish. Multiple robots could work together, each responding to its own instructions but creating emergent coordinated behavior.

This is crucial for any practical application. You can't just have a robot that moves in one direction. It needs to navigate complex 3D spaces, avoid obstacles, follow specific routes. The electrokinetic propulsion system allows all of this.

Let me give you a specific example. In one test, researchers programmed the robots to navigate a simple maze. They could successfully complete the task, turning at corners, avoiding dead ends, making independent decisions about direction. This might seem basic, but it demonstrates something fundamental: the propulsion system is controllable and responsive enough to enable autonomous navigation.

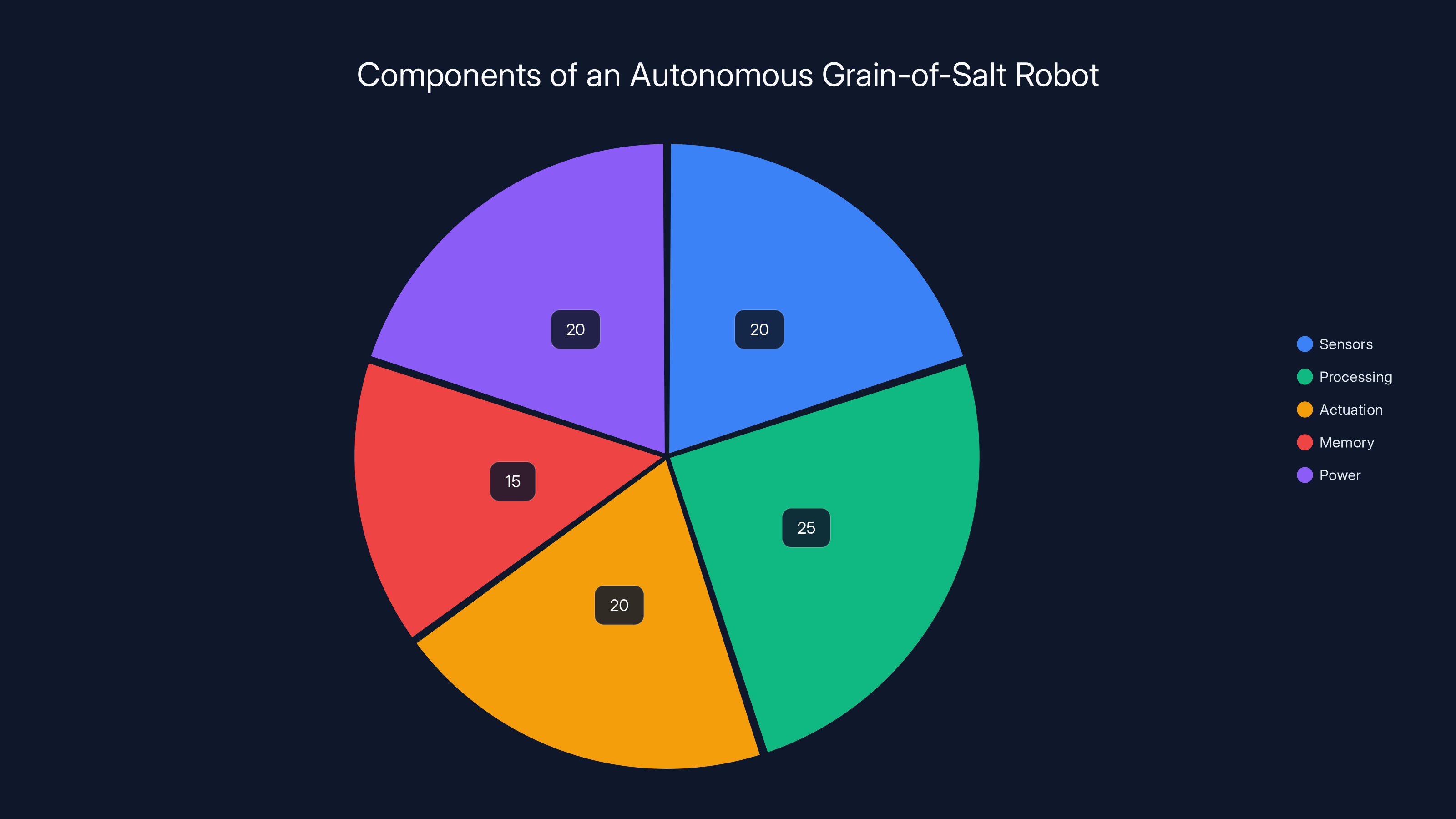

The pie chart illustrates the estimated distribution of key components in Miskin's grain-of-salt robot, highlighting the balance needed for true autonomy. Estimated data.

The Power Problem: 75 Nanowatts and Making It Work

Propulsion solved, but there's a bigger problem. How do you power something this small?

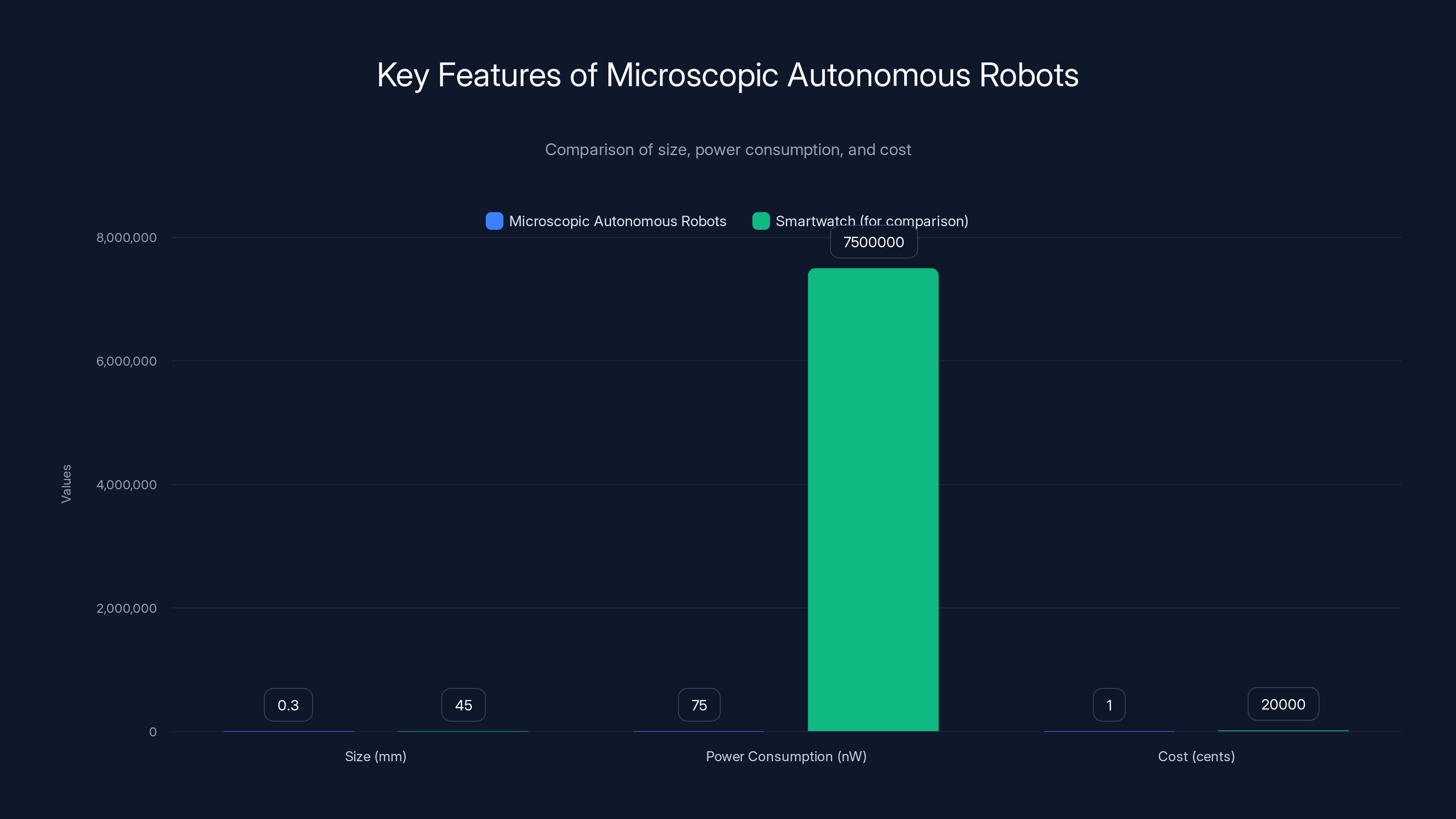

A smartwatch uses roughly 10-20 milliwatts. That's about 130,000 to 260,000 nanowatts. Miskin's robot uses 75 nanowatts. That's 0.000075 milliwatts. It's hard to even conceptualize that energy level.

To put it in perspective: the sun delivers roughly 1,000 watts per square meter to Earth's surface. For a robot that measures 0.3 millimeters across—about 0.09 square millimeters of area—the available solar energy is in the nanowatt range. The team's solution was to cover most of the robot's surface with solar cells and run everything on whatever power those panels could generate.

Designing for Extreme Power Scarcity

This created an entirely new set of constraints. David Blau, the researcher from University of Michigan who led the computational side, had to rethink everything about how computers work.

Normal computers operate at voltages of 3 to 5 volts. Running a computer at such voltages requires circuits designed to handle that voltage range. But at 75 nanowatts, there's almost no power budget for waste. The team had to design custom circuits that operate at millivolt-scale voltages—thousands of times lower than standard electronics.

This is genuinely difficult. Leakage currents (the tiny flows of electricity that happen even when nothing should be flowing) become significant. Thermal noise becomes a problem. Error rates in computation increase. You have to be incredibly clever about circuit design to maintain reliable operation at these energy levels.

The team's solution involved specialized low-voltage circuits. They essentially created a custom processor that's optimized for extreme low-power operation. This processor runs slower than conventional chips—it's measured in kilohertz rather than gigahertz—but it remains reliable even with minimal power.

Software Optimization for Minimal Memory

Beyond hardware, software becomes critical. The processor has extremely limited memory—we're talking kilobytes, not megabytes. A modern smartphone app might require multiple gigabytes. This robot needs to handle sensing, computation, and decision-making in kilobytes.

Blau's team had to completely reimagine the software. Conventional programming assumes you have plenty of memory and can be somewhat wasteful with code. At this scale, every byte matters. They eliminated redundancy, collapsed the code footprint, and used special encoding techniques to store more logic in less space.

One particularly clever approach: they represented algorithms as highly optimized lookup tables rather than computational loops. Instead of computing a result, the processor looks it up in a pre-computed table. This is vastly more energy-efficient and requires less memory, though it only works for algorithms that can be pre-computed.

The result is a complete onboard computer—processor, memory, and sensors—that fits on a chip smaller than 1 millimeter. This had never been done before. Previous attempts either required external computation or used minimal logic with no real decision-making capability.

The Solar Panel Trade-off

Covering most of the robot's surface with solar panels left minimal space for other components. The team had to be ruthless about prioritization. Propulsion? Essential. Sensors? Minimal but present. Memory? As little as possible but functional. Communication? Here's where it gets weird.

The robot can't carry traditional communication hardware—it would use too much power and take up too much space. Instead, the team implemented something borrowed from insect biology: the robot translates sensor readings into movement patterns. Researchers observe these "dance moves" under a microscope and decode the information.

This is inspired by how honeybees communicate. A bee returns to the hive and performs a waggle dance that encodes information about food sources—direction, distance, quality. Other bees watch the dance and decode the information. The researchers applied the same principle to their robot.

The robot uses different movement patterns to represent different sensor readings. An accelerometer detects motion and orientation. A temperature sensor measures thermal conditions. These readings get encoded as specific movement sequences. A human observer (or machine learning system) watches the movements and decodes what the robot sensed.

It's not high-bandwidth communication, but it works. And critically, it requires almost no power. Movement is generated anyway (through electrokinetic propulsion), so encoding information into that movement costs virtually nothing extra.

The Computational Challenge: Fitting a Computer on 0.3 Millimeters

David Blau's team at University of Michigan actually holds the record for building the world's smallest computer. This project was their chance to integrate that computational capability into a fully autonomous robot.

When Blau first met Miskin at a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency presentation, they immediately recognized complementary strengths. Miskin had solved propulsion and could create mechanical systems at extreme scales. Blau had solved computation at extreme scales. Together, they could build the missing piece: a fully autonomous robot smaller than 1 millimeter.

It took five years to make it work.

Integration Challenges

Bringing two cutting-edge micro-systems together created unexpected problems. The solar panels generated electrical noise that interfered with the computational circuits. The electrodes that created the electric field for propulsion created electromagnetic interference that corrupted sensor readings. Components designed independently for extreme miniaturization didn't always play well together when integrated.

The team had to redesign parts of both systems. They added electromagnetic shielding (incredibly difficult at this scale). They separated signal paths to avoid crosstalk. They used clever circuit layout techniques to minimize interference. It was like solving three engineering problems simultaneously—and discovering a fourth problem each time they thought they'd solved something.

Space constraints drove many decisions. The solar panels needed to cover most of the surface for power generation. The electrokinetic electrodes needed specific configurations to create controllable field patterns. The sensor needed to be positioned where it could actually measure something useful. The computational circuits needed to fit in whatever space remained.

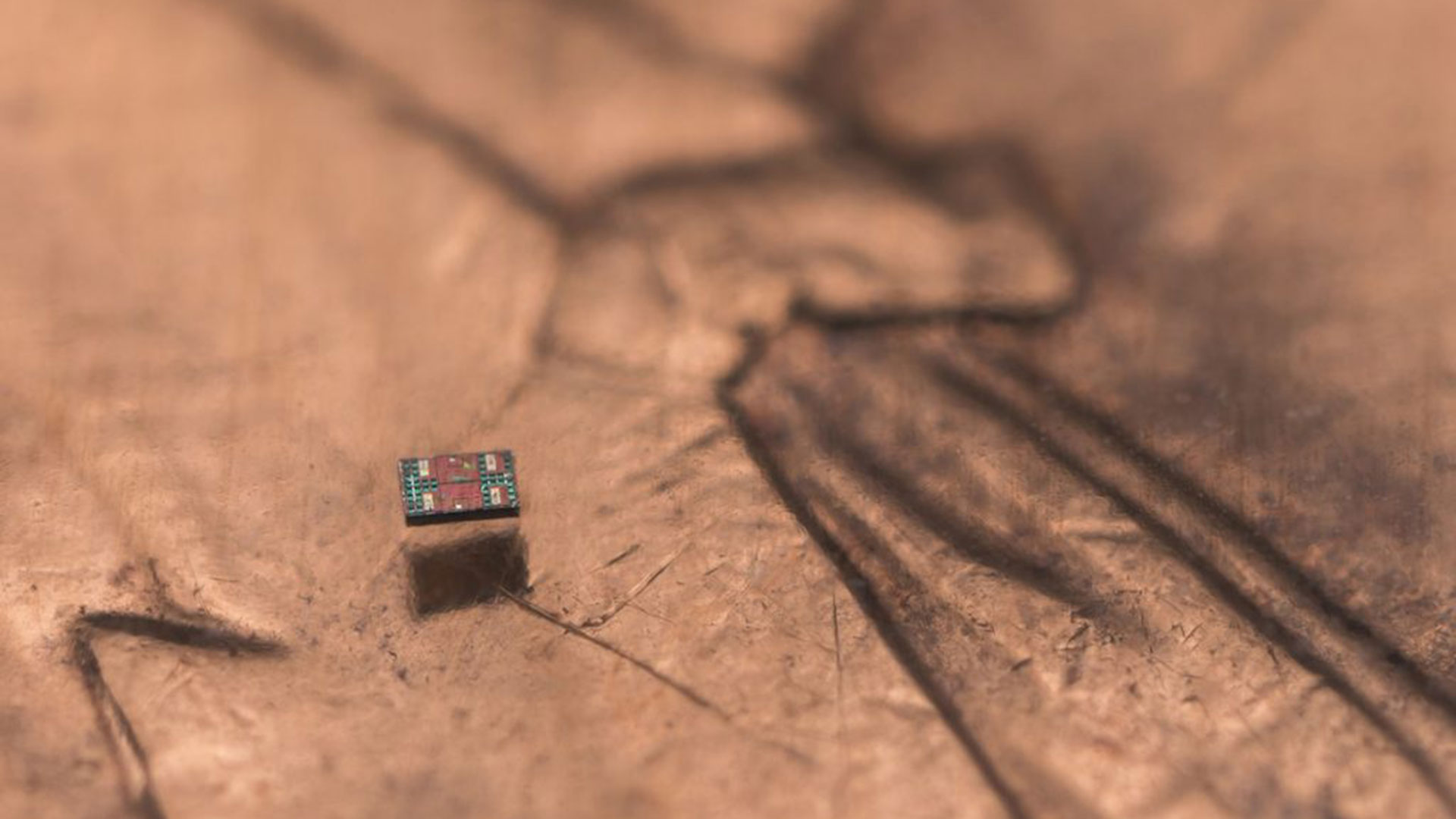

One particularly brilliant design decision: the team integrated the computational circuitry directly underneath the solar panels where space would otherwise go unused. The solar cells are transparent enough that photons can still reach the silicon underneath. This multi-layer approach packed more functionality into the constrained volume.

Sensor Integration

The robot includes a temperature sensor—technically an extremely sensitive transistor configured to measure thermal effects. This seems like a small thing, but it's actually significant. The robot doesn't just move around randomly. It can sense its environment and respond. It can detect heat sources or cold areas. This enables autonomous navigation based on environmental conditions.

The sensor data feeds into the onboard processor, which makes decisions about propulsion direction. If the goal is to find heat, the processor analyzes sensor data and sends commands to the electrokinetic electrodes to change the electric field and move toward the warmer area. This is genuine autonomy—the robot senses, thinks, and acts without external intervention.

Adding a sensor created new challenges. Sensors generate their own electrical noise. They have their own power requirements. They need signal conditioning circuits to amplify their output for the processor to read. All of this had to fit in available space and operate within the power budget.

The team solved this by designing ultra-compact sensor circuits and using clever signal processing techniques. The sensor output gets amplified and filtered using minimal silicon area. The processor uses digital filtering algorithms to reduce noise. It's engineering at the highest level of optimization.

Manufacturing at the Edge of Possibility

Here's the thing that amazes me most: they can actually manufacture these robots. It's not just a one-off prototype built by hand under a microscope. They can produce several hundred units at a time.

The manufacturing process uses standard semiconductor fabrication techniques—the same processes used to make computer chips. The robots are built using photolithography and etching, layer by layer. It's like building an integrated circuit, except instead of just transistors and wires, they're creating mechanical structures, electrodes, solar cells, and sensors all integrated together.

Photolithography and Precision

Photolithography works by using ultraviolet light to transfer patterns from a mask onto a light-sensitive material. You can create features as small as tens of nanometers this way—far smaller than the 0.3-millimeter robot. This enables incredibly precise manufacturing.

But here's the subtle point: precision at the nanometer scale doesn't automatically translate to precision at the micrometer scale. When you're building a structure 300 micrometers long out of elements that are tens of nanometers in size, small variations add up. A layer that's 10 nanometers thicker in one spot can cause problems if the structural elements are only 100 nanometers thick.

The team had to develop new quality control processes. They had to understand and compensate for systematic variations in the manufacturing process. They had to design with tolerance to manufacturing variations built in. A normal engineer might design something with 1% tolerance. Here, they might need 0.1% tolerance, and they still had to achieve that consistently across hundreds of units.

Cost Optimization

Perhaps most impressive: they achieved this with unit production costs around one cent per robot.

One cent. For a fully autonomous robot with onboard computation, sensors, power generation, and propulsion.

This is possible because they use standard semiconductor manufacturing equipment and processes. They're not doing anything exotic or custom. They're just using existing tools in a clever way. The economics work because semiconductor manufacturing, when you have the infrastructure in place, becomes incredibly cheap at scale. You're paying for electricity and materials (cheap) and amortizing equipment costs (expensive but manageable at volume).

This cost structure is important for practical applications. If each robot cost thousands of dollars, you'd deploy just a handful. At one cent, you could deploy thousands or millions. You could use them as disposable sensors, sacrificial explorers in dangerous environments, or distributed monitoring networks.

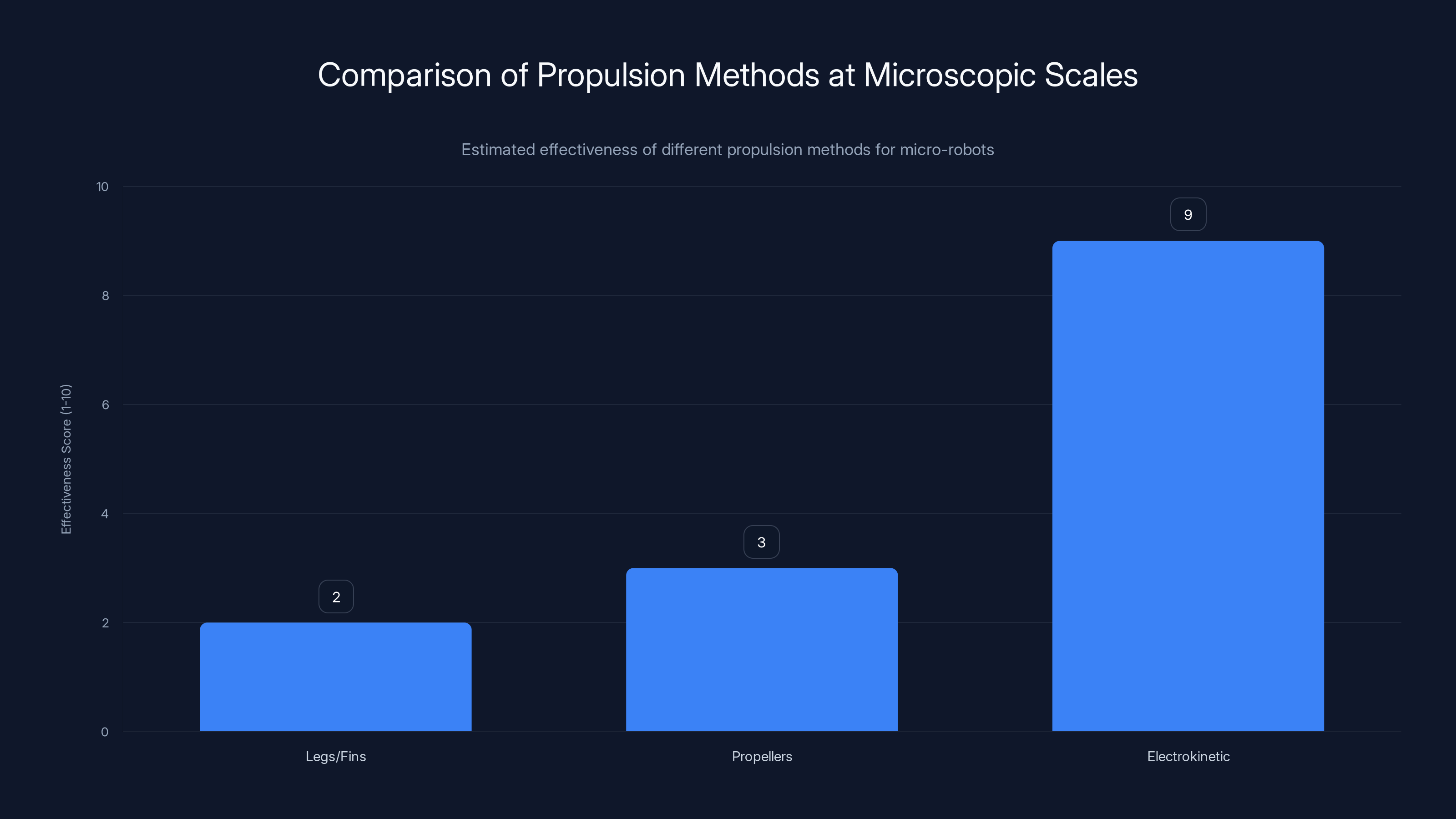

Electrokinetic propulsion is estimated to be significantly more effective than traditional methods like legs or propellers for micro-robots, due to its ability to exploit rather than fight against the physics of microscopic scales. Estimated data.

Autonomous Operation: How a Grain-of-Salt Robot Makes Decisions

The word "autonomous" means the robot operates independently, making its own decisions based on sensory input. This is harder to achieve at tiny scales than you might think.

To be truly autonomous, the robot needs:

- Sensors to perceive the environment

- Processing to interpret sensory data and make decisions

- Actuation to act on those decisions

- Memory to store state and learning

- Power to sustain all of the above

Smaller robots had maybe one or two of these. Miskin's robot has all five, integrated onto a sub-millimeter device.

Sense-Think-Act Loop

The robot's decision-making works like this:

The temperature sensor continuously measures thermal conditions in the surrounding water. That data flows into the processor every few milliseconds. The processor runs a simple algorithm: if the temperature is increasing, intensify the electric field in the current direction (move toward heat). If the temperature is decreasing, change direction (move away from heat).

The processor sends instructions to the electrokinetic electrodes, adjusting the voltage pattern. The electrodes create a new electric field. The new field pushes different charged particles, creating a new water current, and the robot changes direction.

This happens in a loop, thousands of times per second. The robot is constantly sensing, computing, and adjusting. From an outside perspective, you see the robot moving smoothly toward heat sources or away from cold areas. Internally, it's making millions of tiny course corrections based on continuous sensory feedback.

This is genuine autonomy. The robot isn't responding to external commands. It's not following a pre-programmed path. It's responding dynamically to its environment, sensing conditions, and making real-time decisions.

Group Behavior and Coordination

Here's where it gets really interesting: each robot can be programmed with a unique ID and different instructions.

One robot might be searching for heat. Another might be searching for light. A third might be searching for specific chemical signatures. Multiple robots deployed together can perform different roles while operating independently.

Even more intriguing: the robots can coordinate without explicit communication. Each robot just follows its own programming, but collective behavior emerges from that individual operation. It's similar to how a school of fish moves as a coordinated unit even though each fish is just responding to local conditions and neighbors' positions.

In demonstrations, researchers showed multiple robots moving in patterns that seemed coordinated—almost like they were dancing together. In reality, each robot was following its own algorithm. The coordination emerged naturally from the physics of how they interact with water and each other.

This has implications for deploying large numbers of these robots. You don't need a central controller. You don't need them to communicate constantly. You just program them all with slightly different instructions and deploy them. They'll naturally spread out, explore the environment, and perform their assigned tasks.

Technical Innovation: The Engineering Breakthroughs

Let me highlight some of the specific engineering innovations that made this possible:

Integrated Photovoltaics

The solar panels aren't just bolted onto the robot like afterthought. They're integrated into the structure itself. The silicon that generates electricity is the same silicon that serves structural purposes. By using transparent or semi-transparent electrode materials, the team created a multi-functional layer that generates power while allowing light to reach electronics underneath.

This is a brilliant example of co-design—designing components to serve multiple purposes simultaneously. It's how you pack so much functionality into such a tiny space.

Electrokinetic Electrode Patterning

The electrodes that create the electric field aren't simple wires. They're carefully patterned structures that create specific field geometries. The team had to solve inverse problems: given a desired water flow pattern, what electrode configuration would create that field?

They used advanced electromagnetic simulation to design electrode patterns, then refined them through testing. The result is electrode arrangements that create precise, controllable flow patterns even at extreme miniaturization.

Low-Voltage Logic Circuits

The processor operates at voltages around 100 millivolts. Standard logic circuits are designed for 3-5 volts. Operating at 100 millivolts requires fundamentally different circuit topologies. The team developed special "ultra-low-voltage" circuit designs that maintain reliable operation at these extreme conditions.

This involved careful transistor sizing, novel clock distribution schemes, and clever power gating techniques. It's the kind of deep analog and digital circuit design that takes years of experience to master.

Temperature-Compensated Sensing

The temperature sensor needs to work in varying conditions, but the sensor itself is affected by temperature. As ambient temperature changes, the sensor's characteristics change. The team had to implement sophisticated temperature compensation algorithms in firmware to maintain sensor accuracy across a wide operating range.

Real-World Applications: What These Robots Actually Do

This is the practical question: beyond impressive engineering, what's the point?

Turns out, there are quite a few things you can do with sub-millimeter autonomous robots:

Medical Applications

The most obvious application is medicine. These robots could be injected into the human body to monitor specific cells or tissues. The temperature sensor could detect inflammation (inflammatory tissue is slightly warmer). Modified versions with different sensors could detect chemical markers of disease.

Imagine injecting millions of these robots into a patient's bloodstream. They disperse through the circulatory system, find areas of inflammation or infection, and begin reporting (through their dance-move communication) on what they find. Doctors get real-time monitoring of cellular-scale conditions throughout the body.

Drug delivery is another possibility. These robots could be programmed to seek out specific cells and deliver medication directly to them. Or they could sense local temperature and drug concentration, navigating toward target areas and releasing payload when conditions are right.

The size is crucial here. Normal medical devices are large—catheters are millimeters in diameter, limited to major blood vessels. These robots could navigate capillaries, reach individual cells, perform localized measurement and intervention at scales previously impossible.

Environmental Monitoring

Deploying thousands of these robots in a water system to monitor temperature, pollutant concentrations, pH levels, and biological markers could provide unprecedented real-time data about water quality. Traditional monitoring requires periodic manual sampling. With autonomous micro-robots, you'd have continuous distributed monitoring at scales that capture spatial variation impossible to detect with conventional methods.

The robots cost pennies each. You could deploy thousands without breaking a budget. If some fail or get degraded, it doesn't matter—you have thousands of others still reporting. This creates resilience that traditional monitoring systems lack.

Precision Manufacturing

Manufacturing at microscopic scales—creating precise structures at nanometer resolution—requires assembly of components. These robots could serve as microscopic workers, moving sub-micron components into place, assembling structures too small for human manipulation, performing micro-welding or micro-bonding.

This is years away, but the principle is clear. Human hands work at centimeter scales. Robotic arms work at millimeter scales. These autonomous robots work at micrometer scales. As manufacturing moves toward smaller and smaller structures, we'll need tools that can operate at the appropriate scales.

Fundamental Research

At the most basic level, these robots are tools for exploring the microscopic world. You could program them to measure thermal gradients in cell tissues, detect chemical concentration gradients in solution, or map out flow patterns in tiny channels.

The robots essentially become mobile sensors that can navigate and report on conditions in spaces too small for conventional instruments. They expand our ability to measure and understand phenomena at microscopic scales.

Miskin's robot operates at an incredibly low power level of 75 nanowatts, significantly less than a smartwatch's 195,000 nanowatts and comparable to the sunlight power available to the robot.

The Physics of Microscopic Movement: Why Conventional Robotics Failed

I want to go deeper into why this breakthrough required such radical rethinking of robotics principles.

Reynolds Number: The Transition Between Regimes

The Reynolds number is defined as:

Where:

- is fluid density

- is velocity

- is characteristic length

- is dynamic viscosity

At human scales in water,

At microscopic scales,

This is why conventional propulsion mechanisms fail at the micro-scale. You need locomotion strategies that work in viscosity-dominated regimes. Electrokinetic propulsion exploits the continuum mechanics of fluid flow at low Reynolds numbers, creating steady motion that's impossible with mechanical means.

Energy Scaling

Power requirements scale differently at different sizes. For mechanical systems, power needed to move a body scales roughly as:

For a robot 1/1000 the size but moving at the same speed, power requirements drop by a factor of 1,000,000. But power generation (from solar panels) scales with surface area:

For a 1/1000 smaller robot, solar generation drops by a factor of 1,000,000. So paradoxically, smaller robots have better power margins—power requirements drop faster than power generation capability.

But there's a catch: you still need to operate computational and sensing systems, and those have minimum power thresholds. You can't scale a transistor below a certain point without losing functionality. So as robots get smaller, the fraction of available power dedicated to essential systems increases.

Miskin's team solved this by using systems (electrokinetic propulsion) that require minimal power and designing computational systems that operate at extreme energy minimums.

Surface Forces and Material Properties

At microscopic scales, surface forces become significant. Van der Waals forces, electrostatic forces, surface tension—these matter tremendously. They can cause components to stick together (adhesion), inhibit smooth motion, or create unexpected forces.

Materials behave differently at different scales. A polymer that's flexible at macroscopic scales might become brittle at microscopic scales due to crystalline structure effects. The team had to carefully select materials and designs that maintain functional properties across the size and scale regime they were working in.

Comparison with Other Miniaturization Approaches

There are other projects attempting micro-robotics. How does this breakthrough compare?

Magnetic Control Robots

Some researchers build tiny robots controlled by external magnetic fields. These can be smaller than conventional robots because they don't need onboard control systems. But they're not autonomous—they're essentially puppets controlled by external equipment. The advantage is simplicity. The disadvantage is lost autonomy.

Miskin's robots are more complex to manufacture but genuinely autonomous. There's a trade-off between simplicity and capability.

Soft Robotics Approaches

Another approach uses soft, deformable materials instead of rigid structures. Soft robots can navigate tight spaces and are less likely to cause damage. But soft materials have their own challenges—they're harder to control precisely, they degrade faster, they're difficult to manufacture at tiny scales.

Miskin's rigid design is more manufacturable and more durable, though potentially less flexible in navigating complex geometries.

MEMS-Based Systems

Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) use semiconductor manufacturing to create tiny mechanical systems. Some researchers have built MEMS-based robots with moving parts. The advantage is it uses proven manufacturing techniques. The disadvantage is moving parts at microscopic scales are unreliable.

Electrokinetic propulsion avoids moving parts entirely, trading mechanical complexity for electrostatic complexity. It's a fundamentally different engineering philosophy.

Future Directions: What Comes Next

This breakthrough opens possibilities, but there are still significant challenges before these robots are deployed in real applications.

Improving Communication

The dance-move communication works, but it's low-bandwidth and requires human observation (or machine vision systems) to decode. Future improvements might include:

- Modulated propulsion signals: Encoding information in propulsion patterns that can be detected remotely

- Acoustic communication: Using ultrasound for robot-to-robot and robot-to-environment communication

- Optical signals: Using bioluminescence or fluorescence to emit information (though this requires additional power)

Better communication enables more sophisticated task execution and coordination.

Enhanced Sensing

Current robots have temperature sensing. Future versions could include:

- Chemical sensors: Detecting specific molecules or ions

- Pressure sensors: Measuring flow and mechanical forces

- Optical sensors: Detecting light for phototaxis (movement toward light)

- Magnetic sensors: Detecting magnetic fields for navigation

Multiple sensor types would enable richer environmental mapping and more sophisticated autonomous behavior.

Programmable Behavior

Currently, robots are programmed before deployment and can't change behavior dynamically. Future versions might enable:

- In-situ reprogramming: Changing robot behavior after deployment (perhaps through modulated light signals)

- Learning algorithms: Robots that adapt behavior based on experience

- Conditional logic: More complex decision-making beyond simple threshold responses

This requires more powerful onboard computation, which brings you back to power challenges.

Scaled Manufacturing

The current process produces hundreds at a time. Scaling to millions or billions requires:

- Automated assembly: Reducing reliance on human-intensive steps

- Yield improvement: Making sure a higher percentage of fabricated robots function correctly

- Cost reduction: Pushing per-unit costs even lower through volume manufacturing

Once manufacturing scales, deployment costs drop dramatically, enabling applications that require massive numbers of robots.

Biocompatibility

For medical applications, robots need to be biocompatible—not triggering immune responses or toxicity. This requires:

- Surface coating: Coating robots with biocompatible polymers

- Material selection: Using silicon and other materials known to be non-toxic

- Testing protocols: Comprehensive safety testing before human trials

This is regulatory and scientific work, not engineering, but it's essential before medical deployment.

At human scales, high Reynolds numbers indicate inertia-dominated movement. At microscopic scales, low Reynolds numbers mean viscous forces dominate, requiring new propulsion strategies. Estimated data based on typical values.

Challenges Still Remaining

Despite the breakthrough, significant challenges remain before practical deployment:

Localization and Navigation

How do you know where your robots are? GPS works on a human scale but not at the microscopic scale. Future robots need better navigation systems:

- Acoustic beacons: Sound-based positioning (similar to underwater navigation)

- Chemical gradients: Following concentration gradients to navigate

- Fluid flow: Using water current patterns for positional awareness

Without knowing where robots are, you can't direct them to specific locations or verify they completed tasks.

Environmental Variability

Laboratory conditions are controlled. Real environments are chaotic. Temperature, flow rates, chemical composition, pH—all vary and change over time. Robots need to:

- Adapt to conditions: Adjust behavior based on environmental changes

- Handle noise: Ignore spurious sensor signals and focus on real patterns

- Maintain function: Continue operating even when conditions drift outside expected ranges

Robustness to environmental variation is crucial for real-world applications.

Biofilm Formation and Fouling

In aquatic environments, microorganisms and particles accumulate on surfaces. This biofilm can interfere with sensors, increase drag, and even block electrokinetic propulsion. Robots need either:

- Self-cleaning mechanisms: Some way to prevent or remove fouling

- Fouling-resistant coatings: Surface treatments that inhibit biofilm formation

- Adaptive operation: Continuing to function even with some fouling

Maintaining clean surfaces at microscopic scales is non-trivial.

Long-Term Power Stability

The current power system relies on solar panels. This works well in laboratory conditions with LED light sources. In natural environments:

- Water turbidity: Limits light penetration

- Diurnal variations: Less light at night (though these robots could be deployed in controlled facilities)

- Seasonal variations: Changed light intensity throughout the year

For long-term autonomous operation in natural environments, backup power systems might be necessary—perhaps capacitor banks for nighttime, or alternative power generation mechanisms.

Industry Impact: Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

This breakthrough represents something bigger than just a miniaturization record. It suggests a fundamental shift in how we might approach robotics at small scales.

For decades, the robotics industry has tried to miniaturize conventional designs—smaller motors, smaller actuators, smaller mechanical systems. This breakthrough suggests that at some scales, that approach is fundamentally wrong. Instead, you need to rethink the basic principles.

This has implications for how we develop future technologies. When scaling down into new domains, we can't assume that conventional approaches will work. We need to understand the physics of the new domain and design accordingly.

This could influence:

- Biomedical engineering: New approaches to drug delivery, diagnostics, and cellular manipulation

- Environmental science: Novel approaches to water monitoring and pollution detection

- Manufacturing: New possibilities for nanoscale assembly and fabrication

- Materials science: Better understanding of how to create and work with structures at extreme miniaturization

The ripple effects extend well beyond robotics.

Economic Implications

At one cent per unit, economics shift dramatically. With conventional robots costing hundreds or thousands of dollars, you use them sparingly and carefully. With microscopic robots costing a penny, you might deploy thousands or millions.

This enables new economic models:

- Disposable sensors: Cheap enough to throw away after use

- Distributed monitoring: Deploying thousands of sensors instead of dozens

- Redundant systems: Deploying far more robots than needed because failures don't matter much

When the unit cost is negligible, the constraint shifts from procurement to deployment, command, and coordination.

Regulatory Considerations

Before deploying millions of microscopic robots into the environment, regulators will want assurance they won't cause harm. This raises questions:

- Environmental persistence: How long do these robots last in the environment? Do they break down?

- Toxicity: Are the materials safe if robots are ingested or break apart?

- Ecological impact: Could deploying millions of tiny robots affect ecosystems?

Regulatory pathways for microscopic robots don't exist yet. That will need to be developed.

Comparison Table: Microrobotics Approaches

| Approach | Scale | Autonomy | Moving Parts | Power Source | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrokinetic | 0.3mm | Full | None | Solar (onboard) | Durable, long-lasting, truly autonomous |

| Magnetic Control | <1mm | None | Varies | External field | Simpler, less manufacturing complexity |

| MEMS-based | <5mm | Limited | Yes | Onboard or external | Uses proven manufacturing |

| Soft Robotics | 1-10mm | Limited | Yes | Onboard | Flexible, can compress through spaces |

| Conventional | >1cm | Full | Yes | Onboard/external | Established design practices |

Microscopic autonomous robots are significantly smaller, consume far less power, and are cheaper to manufacture compared to conventional devices like smartwatches. Estimated data for smartwatch values.

Lessons for the Future of Engineering

What can engineers and scientists learn from this breakthrough?

First: Don't assume conventional wisdom scales down. When working at different scales, fundamental physics changes. Electrokinetic propulsion wouldn't make sense at human scales, but at microscopic scales, it's optimal.

Second: Multidisciplinary collaboration is essential. This project required expertise in electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, materials science, manufacturing, physics, and more. A single discipline couldn't have achieved this.

Third: Sometimes the answer requires completely rethinking the problem. Trying to build tiny motors and mechanical systems was a dead end. Solving the problem meant abandoning the mechanical approach entirely and finding a different solution that exploited rather than fought physics.

Fourth: Integration and co-design beat modular approaches at extreme scales. When space is at a premium, components need to serve multiple purposes. The solar panels aren't an add-on; they're integral to the structure.

Fifth: Manufacturing capability constrains what's possible. The team could accomplish this because semiconductor manufacturing techniques are incredibly precise and scalable. If they had to use manual assembly or exotic fabrication techniques, it would have remained impossible.

The Next Decade: Predictions

Assuming research continues at current pace, here's my prediction for what we might see:

Year 1-2: Incremental improvements to current design. Better sensors, improved power efficiency, more sophisticated onboard logic. Demonstrations of coordinated group behavior with multiple robots performing different tasks.

Year 3-5: First clinical trials for medical applications, likely in controlled settings (ex vivo cell monitoring). Deployment of environmental monitoring systems in controlled aquatic facilities.

Year 5-10: Broader medical applications as regulatory pathways are established. Environmental monitoring in natural water systems. Manufacturing applications in nanotechnology and microelectronics.

Year 10+: Potentially the emergence of what might be called "robotic swarms" or "microrobotic systems"—not individual robots operating alone but coordinated groups performing complex collective tasks.

The pace will depend on funding, regulatory approval, and whether the approach proves as practical as current results suggest.

Potential Risks and Ethical Considerations

With any powerful technology, there are considerations beyond the engineering:

Environmental Concerns

If millions of these robots are deployed in natural environments, what happens when they fail or when their useful life expires? Do they biodegrade? Do they accumulate in sediments? Could they harm aquatic organisms?

These questions need answered through careful research before large-scale deployment.

Medical Concerns

Injecting microscopic robots into human bodies raises obvious safety questions. What if they malfunction and can't be removed? What are long-term health effects? How do we ensure they don't trigger immune responses?

These would need extensive testing before human trials.

Surveillance Potential

Microscopic robots with sensors could theoretically be used for surveillance in ways that would violate privacy. A robot small enough to enter someone's home undetected, equipped with sensors—the potential for misuse is concerning.

Developing guidelines for responsible use and preventing misuse would be important as the technology matures.

Resource Consumption

At scale, these robots would consume semiconductor manufacturing resources. Semiconductor fabrication is energy-intensive and resource-consuming. If deployed at massive scale, the environmental cost of manufacturing billions of robots could be substantial.

Life cycle analysis would be important before wide deployment.

How This Connects to Broader Robotics Trends

This breakthrough doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of several larger trends in robotics:

Miniaturization: There's been continuous drive to make robots smaller. This breakthrough represents a major milestone in that trajectory.

Swarm robotics: Research has been trending toward groups of simple robots doing complex things together rather than single complex robots. These microscopic robots are ideal for swarm approaches.

Soft robotics: There's growing interest in non-rigid, flexible robots. While Miskin's robots are rigid, the underlying principle—rethinking how robots work rather than miniaturizing conventional designs—aligns with soft robotics philosophy.

Bio-inspired robotics: Copying biological solutions (like the bee dance communication) is increasingly central to robotics. This project does exactly that.

Energy-harvesting robotics: Robots that power themselves from environmental energy (sunlight, vibration, etc.) avoid needing batteries or cables. These micro-robots rely entirely on solar power—the ultimate energy-harvesting design.

Miskin's work sits at the intersection of all these trends, suggesting where robotics might head in coming years.

Getting Hands-On: The Research Community

If this fascinates you and you want to get involved in microrobotics research, there are paths:

University programs: Programs in electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, or materials science with emphasis on micro-systems. Universities like University of Pennsylvania, University of Michigan, and others have active research groups.

Internships: Research groups working on microrobotics often seek talented undergraduate and graduate students. If you have strong fundamentals in relevant fields, you might be able to contribute.

Published research: Academic papers from Miskin, Blau, and collaborators provide technical details. If you have background in relevant fields, diving into the research literature is accessible.

Hackerspaces and maker communities: While you won't be fabricating your own semiconductor devices, learning about MEMS, microfluidics, and miniaturization through maker communities can build understanding and skills.

Microrobotics is increasingly accessible as a research area. Costs for small-scale prototyping are dropping, tools are becoming more available, and knowledge is being shared more openly.

Conclusion: A New Scale of Engineering

What impresses me most about this achievement isn't just the technical accomplishment—though that's genuinely impressive. It's that it opens a new frontier.

For decades, roboticists tried to make robots smaller by miniaturizing existing designs. It didn't work. Miskin and Blau didn't try harder at miniaturization. They fundamentally reconceived what a robot could be at microscopic scales.

They asked: what physics dominates at this scale? What propulsion mechanisms work when mechanical movement is futile? What computation is possible with nanowatt power budgets? How can you communicate when you can't carry radios? Once they answered those questions, the solution became clear.

This is how breakthroughs happen. Not through incremental improvement, but through reconceiving the problem itself.

These robots—smaller than a grain of salt, powered by nothing but light, equipped with their own computers and sensors, making autonomous decisions about how to navigate their environment—represent a proof of concept. They demonstrate that microscopic-scale autonomy is possible.

What comes next is harder: making this reliable, manufacturable at scale, and proven in real applications. That work is just beginning.

But the path forward is clear. And for the first time, the barrier isn't whether it's possible. It's whether we can make it practical.

Given the pace of progress in microelectronics, manufacturing, and robotics, I suspect that's a question with a positive answer coming within the decade.

FAQ

What is a microscopic autonomous robot?

A microscopic autonomous robot is a fully independent machine smaller than traditional robots—in this case, measuring just 0.3 millimeters—that can sense its environment, make decisions, and move without external control systems or power sources. Unlike remotely controlled micro-devices, these robots are genuinely autonomous, with onboard computation, sensors, and power generation.

How does electrokinetic propulsion work?

Electrokinetic propulsion works by generating an electric field around the robot that moves charged particles in the surrounding liquid. As these charged particles move, they drag water molecules with them through a phenomenon called electrokinesis, creating a current that carries the robot along. Unlike mechanical propulsion, this requires no moving parts and exploits the physics of viscous flow at microscopic scales rather than fighting against it.

How long can these robots operate?

According to the research team, these robots can operate continuously for months powered solely by light energy. They generate approximately 75 nanowatts of power through onboard solar panels—roughly 1/100,000th the power consumption of a smartwatch—making them extraordinarily efficient. The lack of mechanical moving parts contributes to their extended operational lifespan since there's no friction or mechanical degradation.

How much do these robots cost to manufacture?

The production cost is approximately one cent per robot, making them extremely affordable at scale. This low cost is possible because they use standard semiconductor manufacturing techniques and processes already in place for computer chip production. The economies of scale in semiconductor fabrication mean costs drop dramatically when manufacturing millions of units.

What are the primary applications for microscopic robots?

Potential applications include medical monitoring at the cellular level, environmental water quality monitoring, precision drug delivery, micro-scale manufacturing and assembly, fundamental research into microscopic systems, and distributed sensing networks. The technology is still early, with most applications being theoretical, but medical and environmental applications are considered most promising for near-term development.

How do these robots communicate since they can't carry traditional radio hardware?

The robots encode information into movement patterns—essentially translating sensor readings into specific "dance moves" similar to how honeybees communicate. Researchers observe these movement patterns under a microscope and decode the information. While this is low-bandwidth, it requires virtually no power, making it ideal for extremely energy-constrained systems.

Can these robots be controlled or reprogrammed after deployment?

Current versions are programmed before deployment and operate according to their fixed programming. Once released, they cannot be reprogrammed or controlled externally. Future versions might enable in-situ reprogramming through modulated light signals or other wireless methods, though this would require additional onboard processing power.

Why couldn't conventional robotics approaches be miniaturized to these scales?

At microscopic scales, the physics changes fundamentally. Viscous forces overwhelm inertial forces, making traditional mechanical propulsion ineffective. Additionally, manufacturing moving parts at the micrometer scale is extremely difficult and unreliable. The team's solution abandoned mechanical movement entirely in favor of electrokinetic propulsion that exploits the dominant physics at microscopic scales.

What are the limitations of current microrobotic designs?

Current limitations include low-bandwidth communication, basic sensing capabilities (temperature only in current version), inability to be reprogrammed after deployment, vulnerability to fouling from biofilm accumulation, and challenges with precise localization in real environments. Navigation and knowing exactly where robots are located remains unsolved. These are engineering challenges being addressed through ongoing research.

When will these robots be available for practical applications?

The technology is currently in the research phase. Medical applications might emerge within 5-10 years pending regulatory approval and additional safety testing. Environmental monitoring applications could potentially be deployed in controlled settings within 3-5 years. Widespread commercial availability likely remains a decade away, pending further development, regulatory pathways, and manufacturing scale-up.

Final Thoughts

This breakthrough in microscopic robotics represents more than just impressive engineering. It's a reminder that sometimes the path forward requires fundamental rethinking rather than incremental improvement. As we face challenges requiring solutions at previously inaccessible scales—medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, nanoscale manufacturing—tools like these autonomous micro-robots might prove essential.

The researchers involved in this project have opened a door. What comes through that door in the next decade will be determined by the robotics community, funding bodies, and whether real-world applications prove as promising as laboratory results suggest. But for the first time, sub-millimeter autonomous robotics isn't theoretical. It's real, reproducible, and being actively developed.

That's genuinely exciting.

Key Takeaways

- Sub-millimeter autonomous robots represent breakthrough in miniaturization after 40 years of failed attempts

- Electrokinetic propulsion exploits microscopic-scale physics instead of fighting it with mechanical systems

- Onboard computation, sensing, and solar power generation enable genuine autonomy without external control

- Manufacturing costs of approximately one cent per unit enable deployment at massive scales

- Medical, environmental, and manufacturing applications could emerge within 5-10 years with further development

Related Articles

- Tesla Optimus: Elon Musk's Humanoid Robot Promise Explained [2025]

- Robot Swarms That Bloom: The Future of Adaptive Architecture [2025]

- Ultrafast Laser Nanoscale Chip Cooling: Revolutionary Heat Management [2025]

- Ocean Robots in Category 5 Hurricanes: Oshen's Breakthrough [2025]

- The Robots of CES 2026: Humanoids, Pets & Home Helpers [2025]

- OlloBot Cyber Pet Robot: The Future of AI Companions [2025]

![Microscopic Autonomous Robots Smaller Than Salt: Engineering the Impossible [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microscopic-autonomous-robots-smaller-than-salt-engineering-/image-1-1769251033537.jpg)