South Carolina's Measles Outbreak Reaches Historic Proportions in 2026

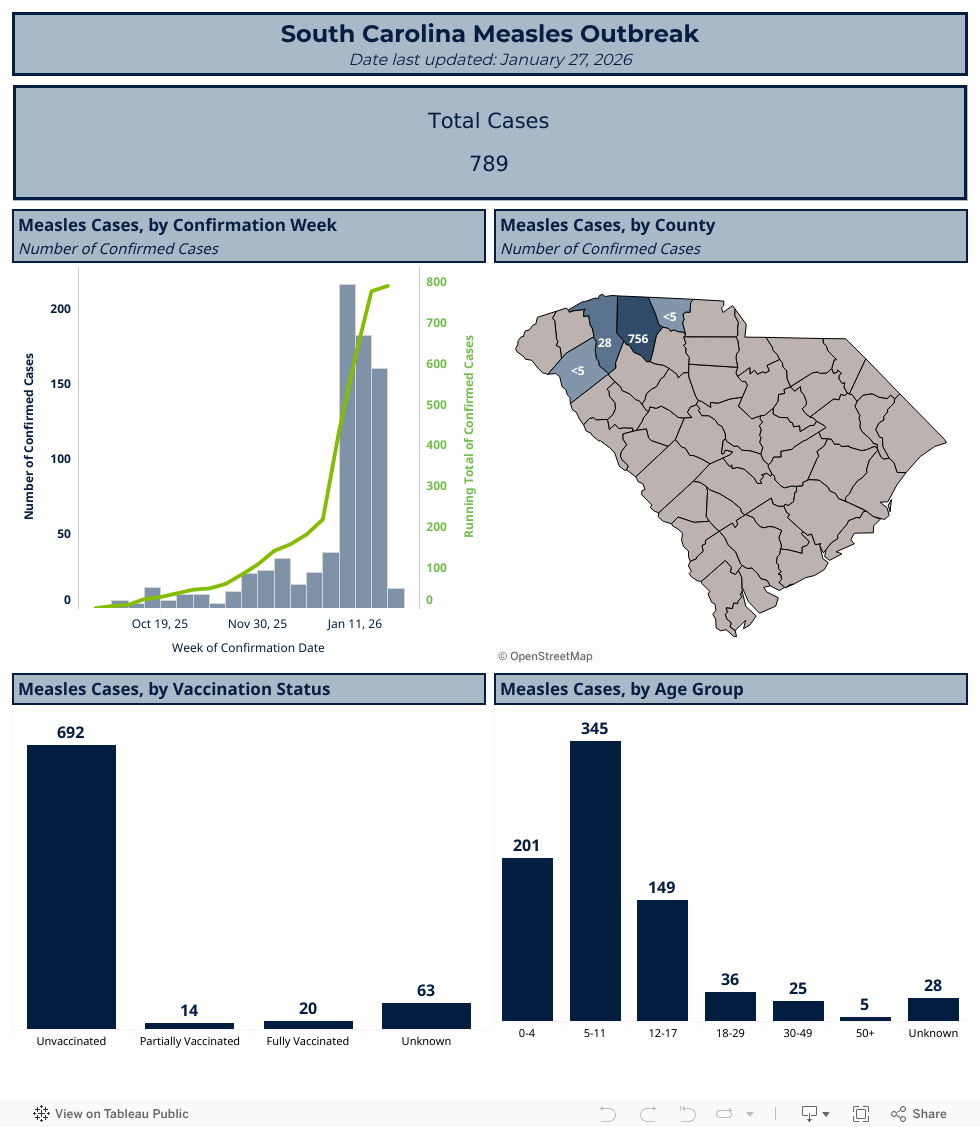

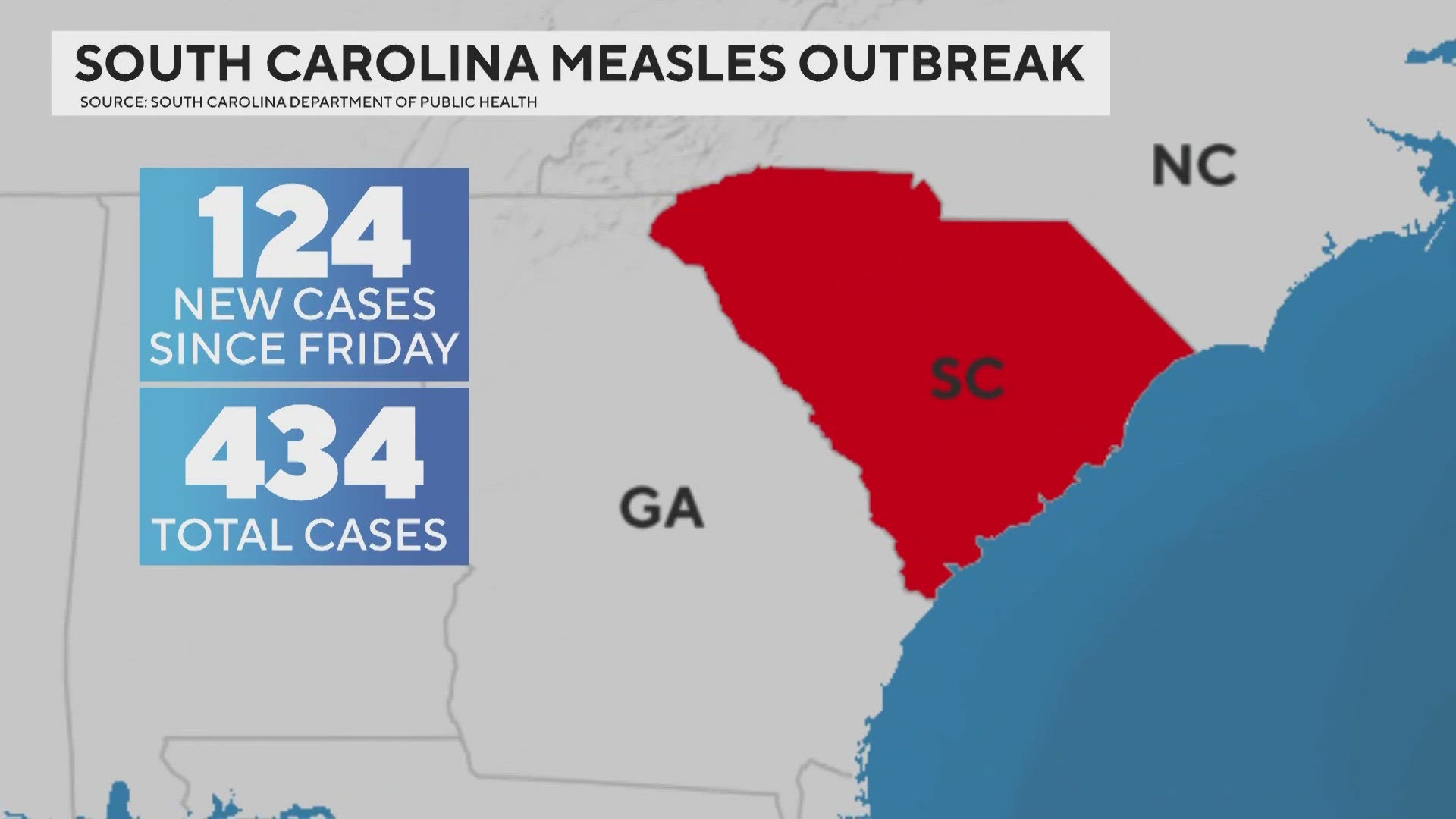

We're witnessing a public health crisis that shouldn't exist in modern America. South Carolina's measles outbreak has shattered records, climbing to 789 confirmed cases as of late January 2026. This isn't just another disease spike. It's a reminder of how quickly a preventable illness can spiral when vaccination rates plummet and communities lose immunity.

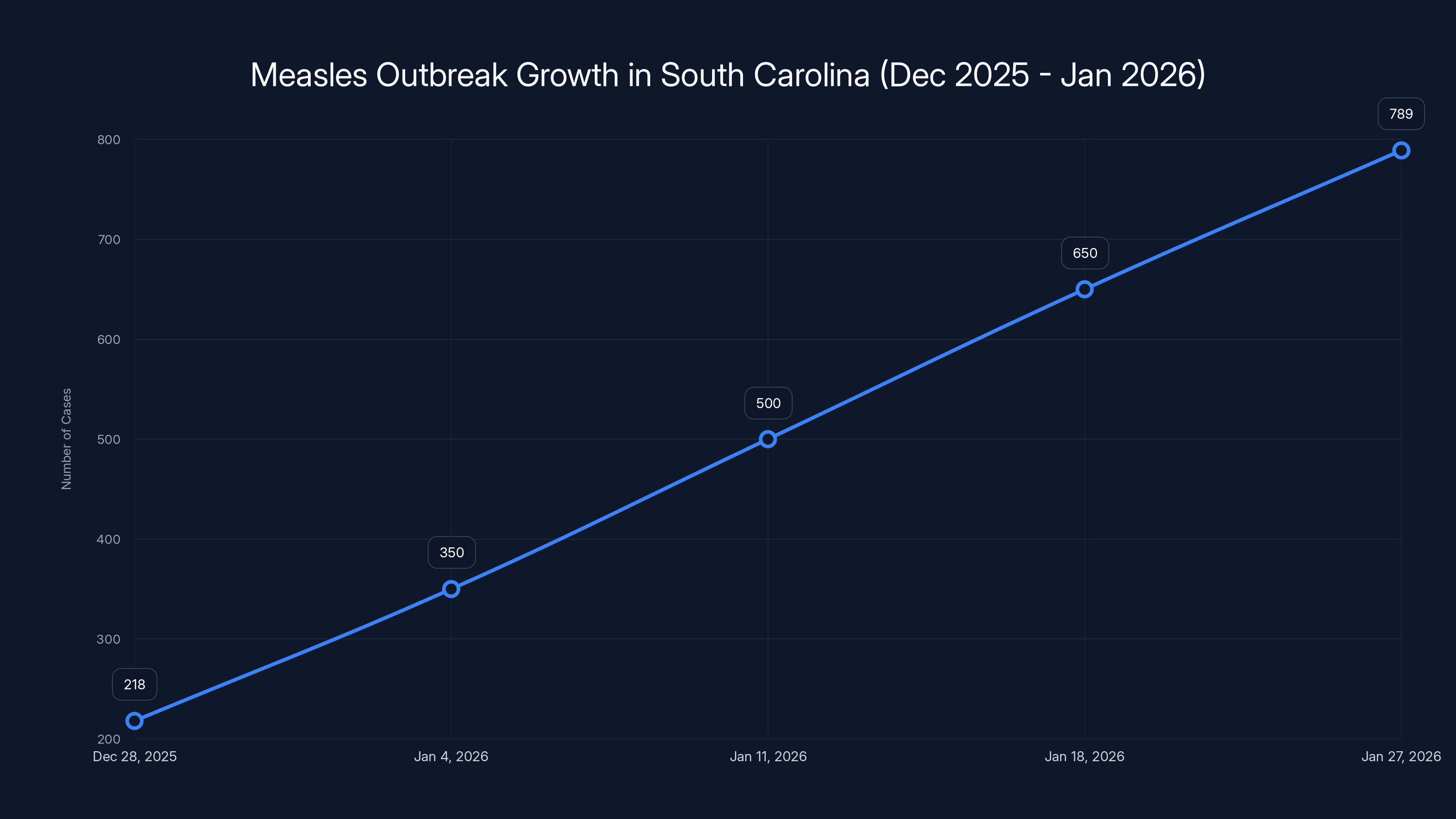

Let's put this in perspective. Texas's outbreak last year, which held the record for the largest measles outbreak in the US since elimination was declared in 2000, topped out at 762 cases. South Carolina has now surpassed that. But here's what's scarier: the outbreak started accelerating dramatically in January, jumping from 218 cases on December 28 to 789 by January 27. That's a 262% increase in a single month.

This isn't an isolated incident anymore. Measles has spread across 13 states including Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Utah, Virginia, and Washington. A particularly concerning outbreak is brewing at the Utah-Arizona border, where 457 combined cases have been reported. The national tally stood at 416 cases as of mid-January, though that number was already outdated given the South Carolina surge.

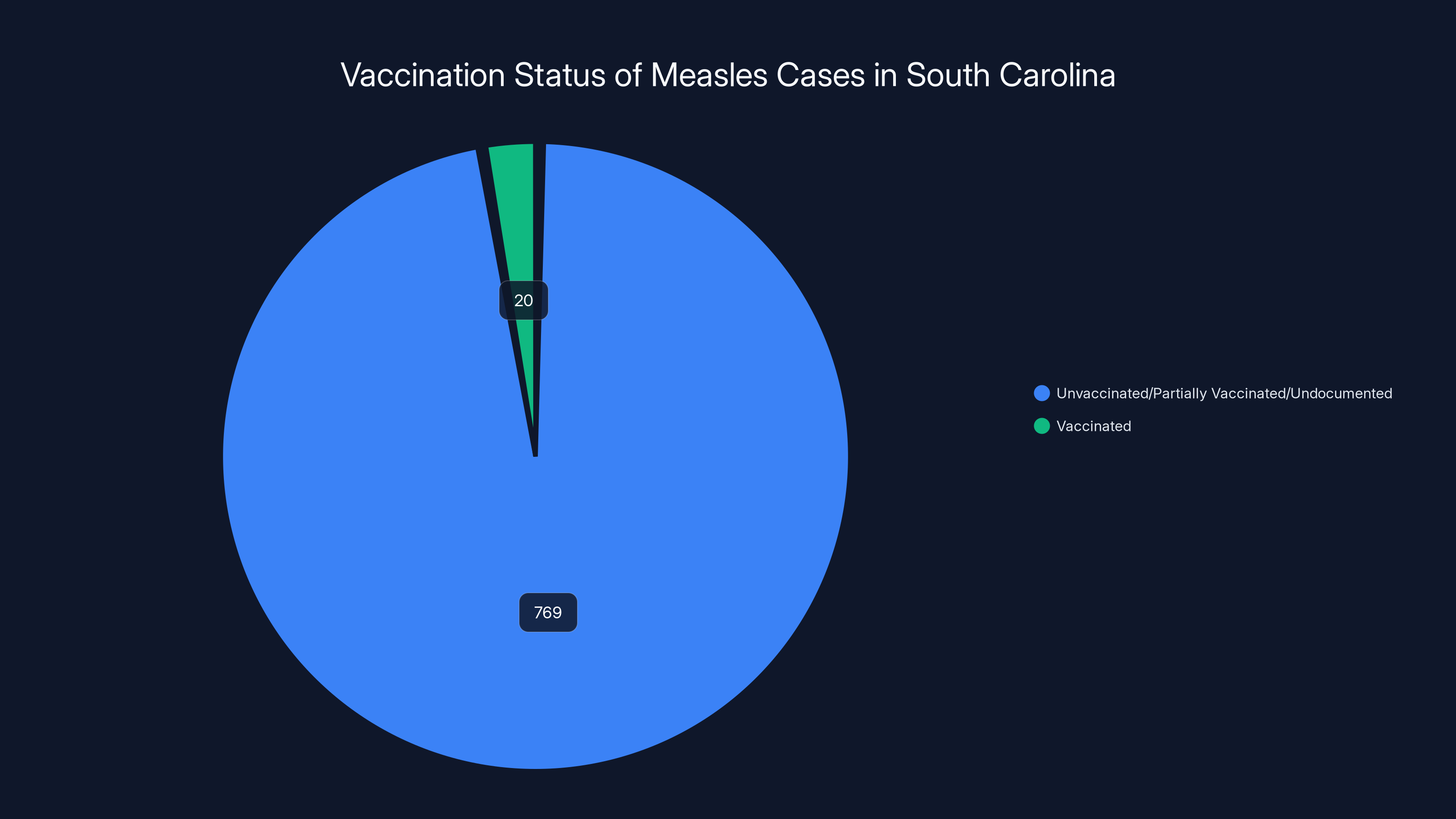

The real tragedy? Among the 789 South Carolina cases, 769 (approximately 97%) were unvaccinated or partially vaccinated or had undocumented vaccination status. Two doses of the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine are 97% effective against measles, and that protection is considered lifelong. We have a tool that works. We're just not using it.

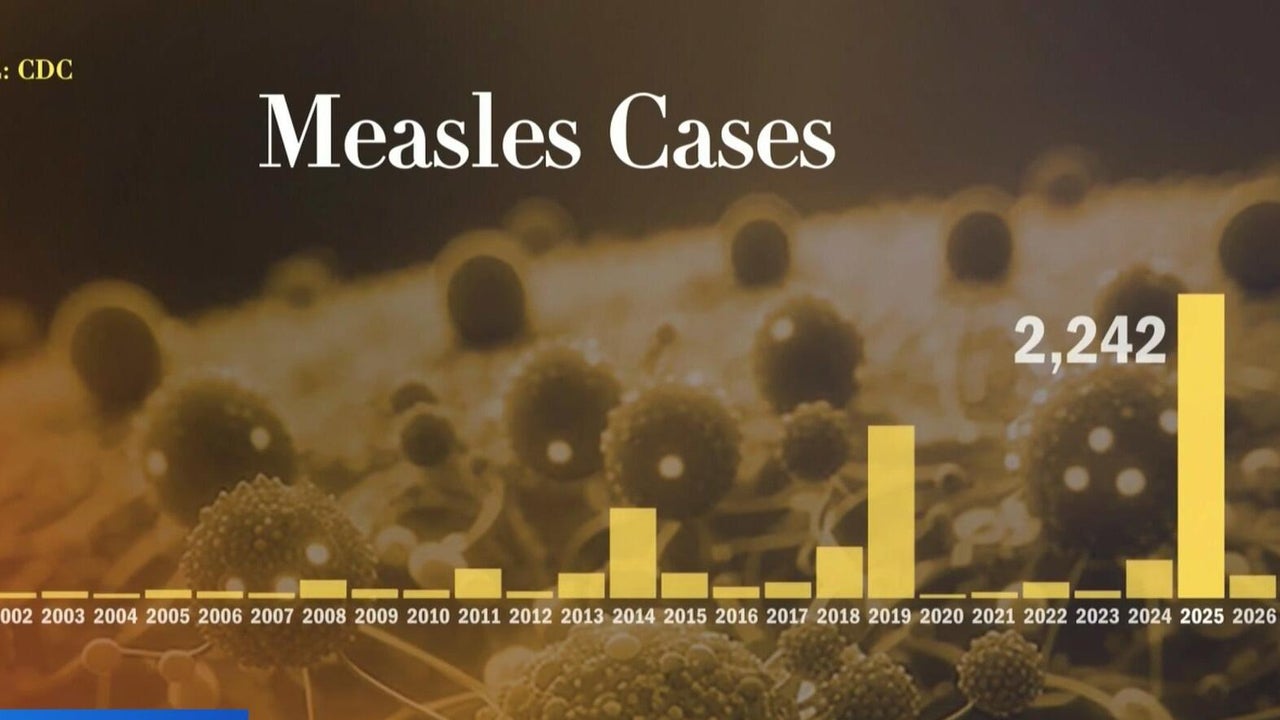

What makes this outbreak particularly alarming is the trajectory. If the current acceleration continues, 2026 could easily eclipse 2015's total of 2,255 cases across the entire country. We're only one month into the year, and we're already seeing unprecedented spread. Health officials are warning that the US risks losing its measles elimination status in the coming months, a designation we've held for 26 years.

The Explosive Growth: From Manageable to Catastrophic

Measles outbreaks don't explode overnight. They build momentum, and South Carolina's shows us exactly how quickly that momentum can accelerate.

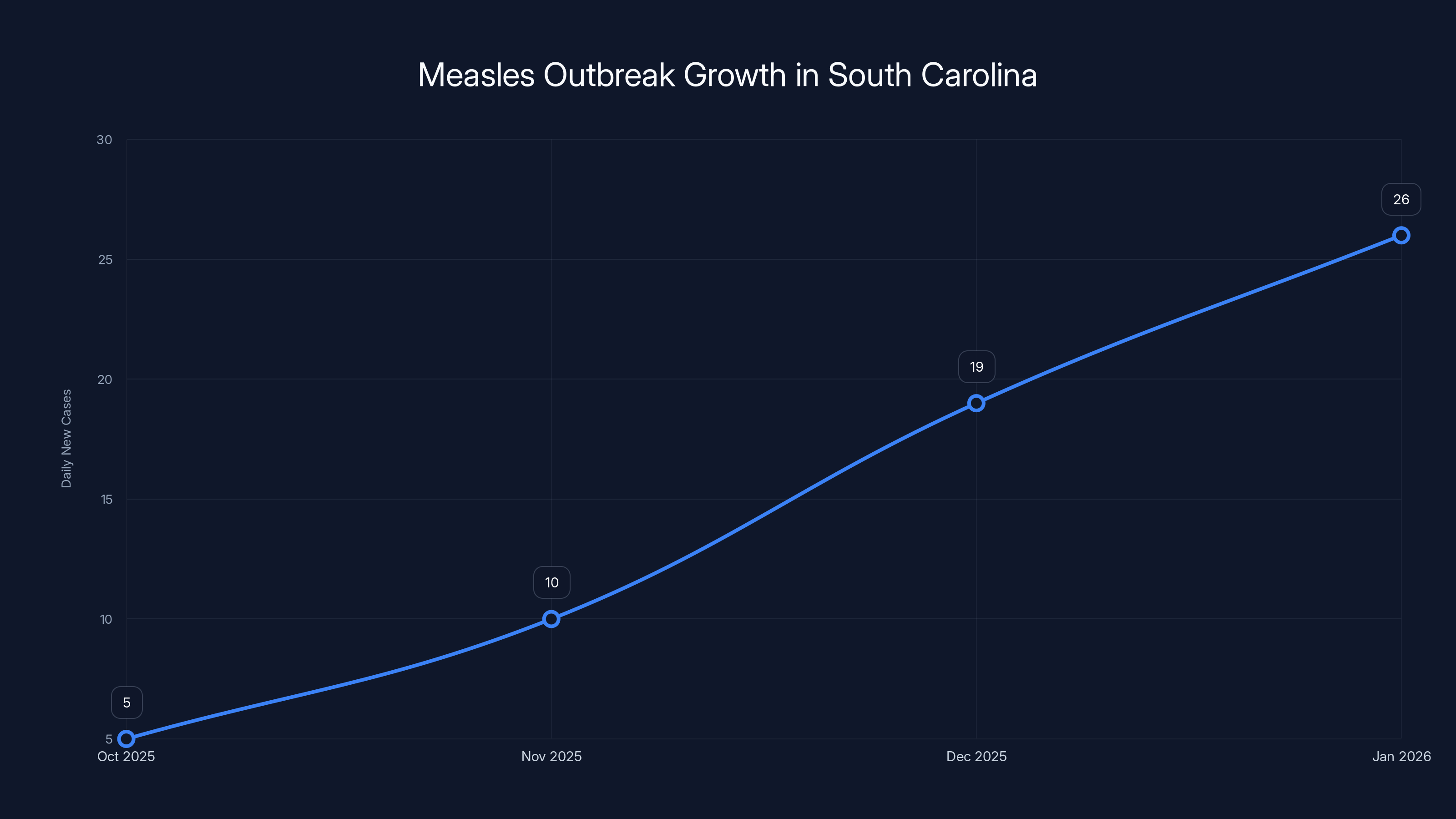

The outbreak started quietly in October 2025. For the first three months, it was concerning but seemingly contained. Health officials were monitoring it, implementing standard protocols, and expecting the usual trajectory of disease surveillance and control. Then something changed in December and January.

On December 28, South Carolina had recorded 218 cases. By January 27, that number had grown to 789. That's 571 new cases in 30 days. Breaking it down further, this represents roughly 19 new cases per day at the peak of the surge. For comparison, measles outbreaks typically see single-digit daily increases once containment measures are in place.

What drove this exponential growth? Several factors converge in this outbreak. First, the virus itself is remarkably contagious. Measles can linger in the airspace of a room for up to two hours after an infected person has left. A single infected individual in a poorly ventilated space—say, a school hallway or a grocery store—can expose dozens of people in minutes.

Second, the incubation period creates a timing problem. Symptoms typically develop 7 to 14 days after exposure, but can take as long as 21 days. This means people are contagious for four days before any symptoms appear and another four days after the telltale rash develops. That's potentially eight days of transmission before a person even knows they're sick. With some infections only identified when the rash develops, the virus has a long runway to spread.

Third, and perhaps most critical, vaccination rates in South Carolina have dropped. Among unvaccinated people exposed to an infectious person, up to 90% will become ill. This creates a cascade effect: each infected person, on average, infects 9 out of 10 unvaccinated contacts. In a school with low vaccination rates, a single exposure can seed multiple simultaneous infections.

The numbers tell the story of accelerating transmission. In early December, cases were doubling roughly every 10 days. By January, that doubling time had shortened to every 7 days. If growth continues at that rate, South Carolina could reach 1,500 cases by mid-February.

The chart illustrates the rapid increase in daily new measles cases in South Carolina from October 2025 to January 2026, with a peak of 19 new cases per day in December. Estimated data highlights the exponential growth during this period.

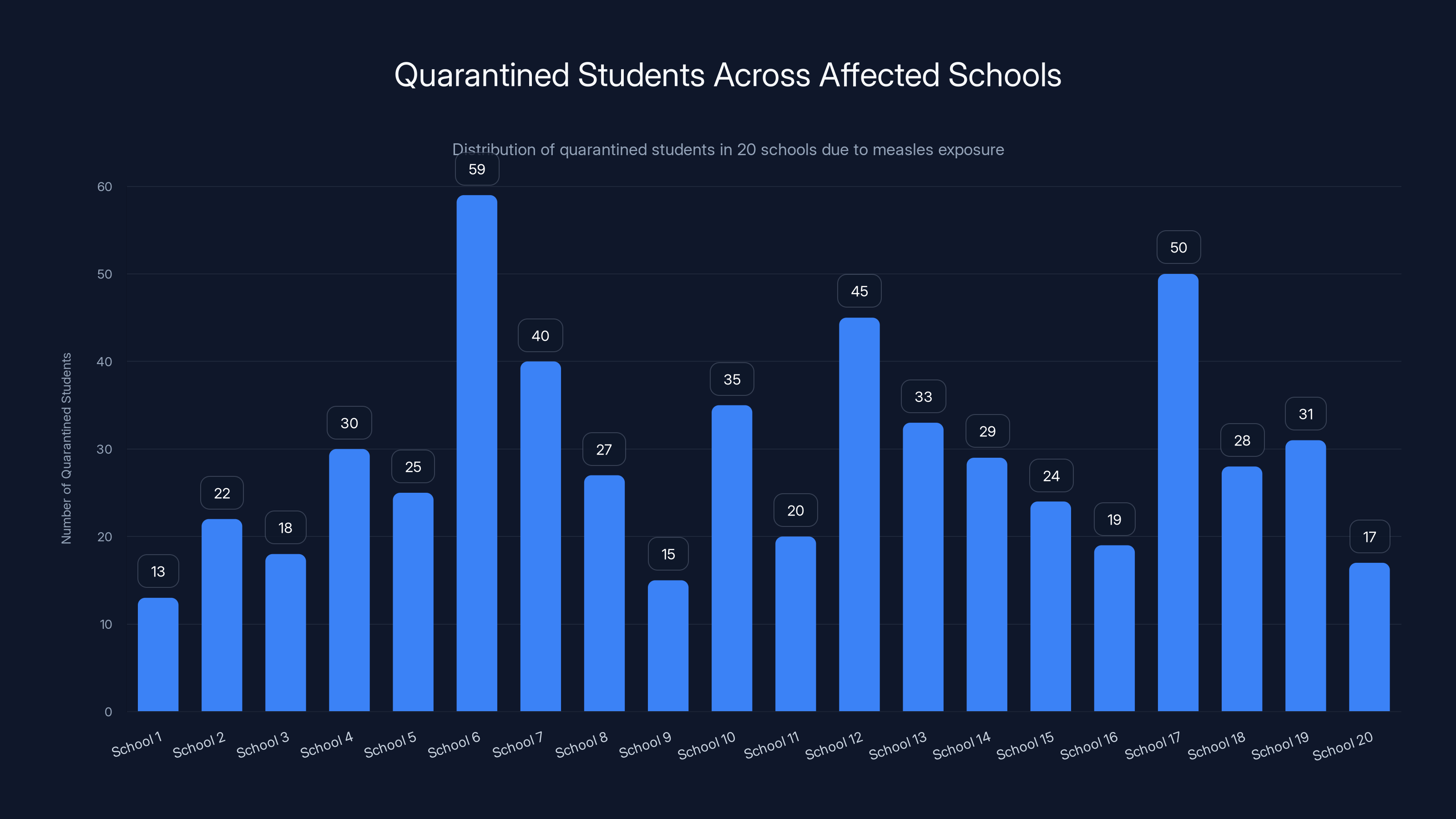

Schools Under Siege: 23 Institutions and 557 Quarantined Students

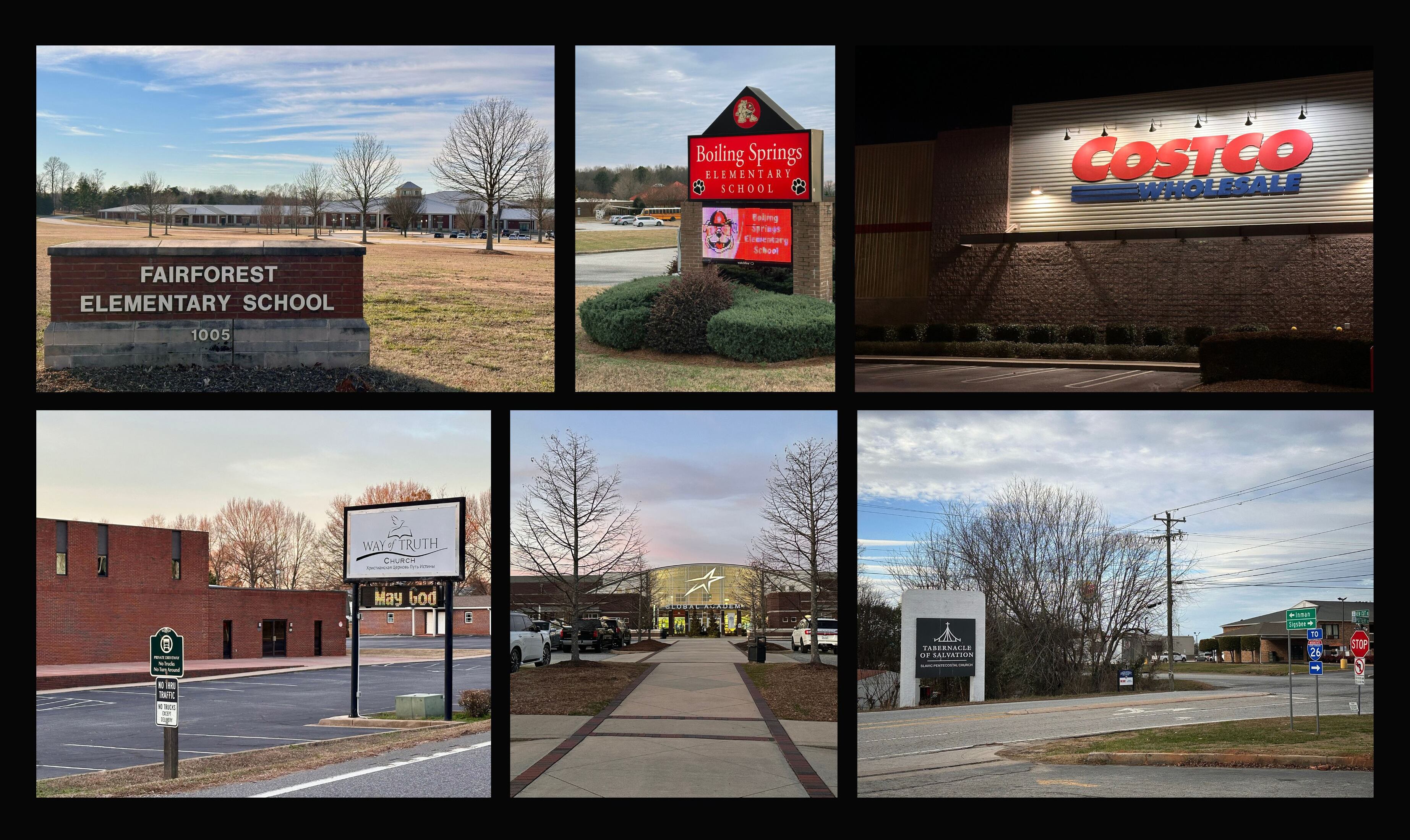

The outbreak's reach into South Carolina's education system is staggering. Health officials have identified measles exposures at 23 schools. Let that sink in. Twenty-three institutions where children spend six hours a day, sharing air, surfaces, and close contact.

In 20 of these schools, unvaccinated or exposed students have been identified and quarantined. The numbers vary by school: some schools have 13 quarantined students, others have as many as 59. One school has 59 children at home, unable to attend class, unable to see friends, isolated because one person brought measles into their building.

Collectively, 557 students have been officially quarantined. That's 557 families managing absences from school, scrambling to arrange childcare, dealing with the stress of potential illness. For the remaining three schools with confirmed exposures, officials are still determining quarantine totals, meaning that 557 number is likely to grow.

A 21-day quarantine is standard for measles because of that extended incubation period. Three weeks out of school for a child who isn't even sick yet. Three weeks of disrupted education, missed lessons, social isolation. And that's assuming the quarantine doesn't extend if the child develops symptoms.

The educational disruption is significant. Schools are operating at reduced capacity. Teachers have students in class and students quarantined at home, requiring them to manage hybrid teaching. Schools are implementing emergency protocols: restricting visitors, increasing cleaning frequency, spacing students further apart during lunch and common areas. Some schools have considered temporary closures, though full shutdowns remain a worst-case scenario.

Beyond the 23 schools, health officials have identified eight public places where measles exposures occurred. Grocery stores. A US Post Office. A skating center. These are the spaces where vulnerable populations gather: young children, elderly people, immunocompromised individuals. A single unmasked, unvaccinated infected person in a grocery store during peak hours could expose hundreds.

South Carolina's measles cases surged by 262% from 218 to 789 within a month, highlighting a rapid outbreak escalation.

The Biology of Measles: Why It Spreads So Efficiently

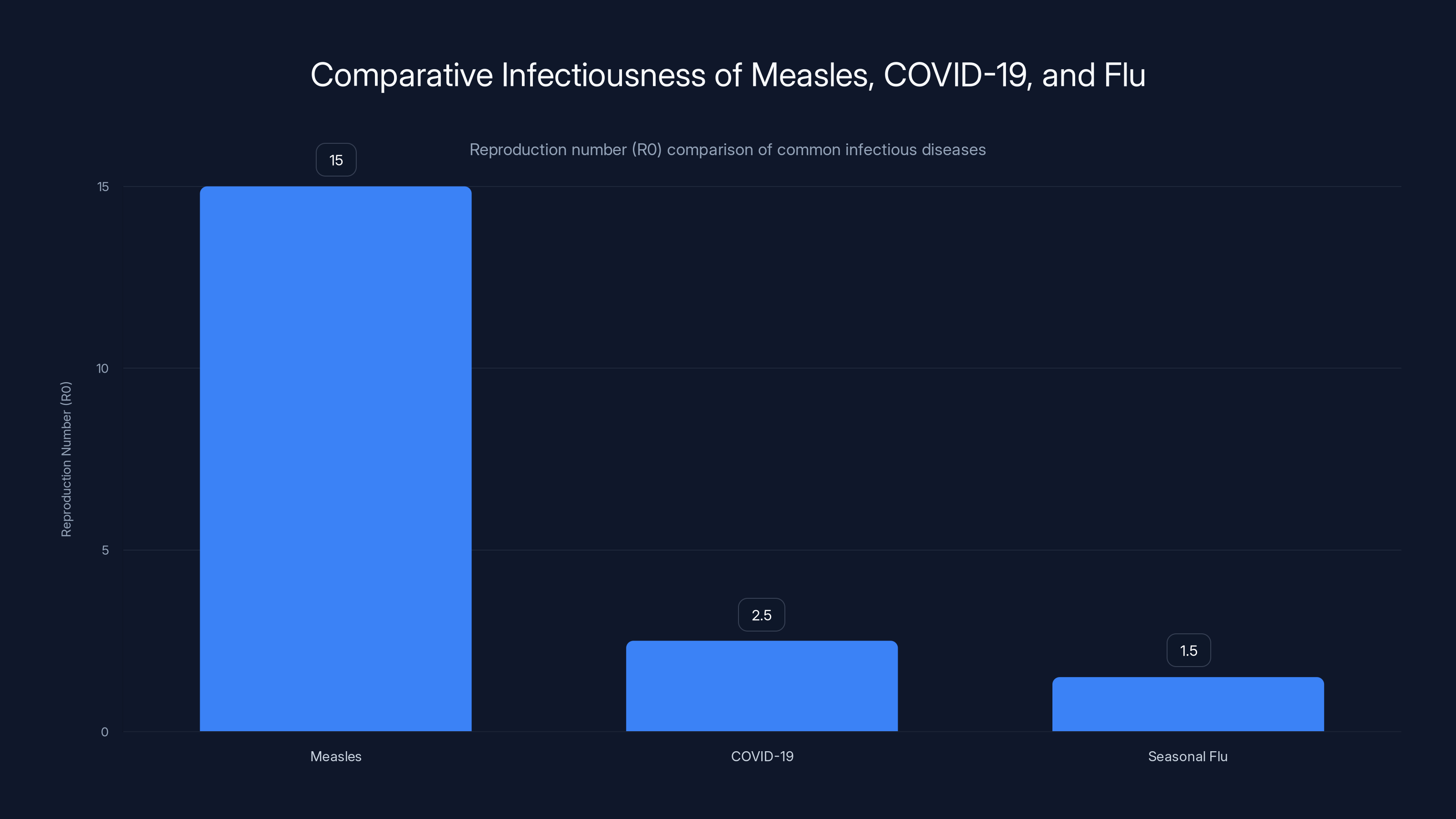

Understanding why measles spreads so rapidly requires understanding the virus itself. Measles is one of the most infectious viruses known to medicine. It's not close. It's not comparable to COVID-19 or seasonal flu. Measles is in a category by itself.

The reproduction number for measles, denoted as R0, is between 12 and 18. That means one infected person will, on average, infect 12 to 18 other people in an unvaccinated population. For comparison, COVID-19's R0 ranges from 2 to 3, depending on the variant. Seasonal flu sits around 1 to 2. Measles is 6 to 9 times more contagious than COVID-19.

The virus spreads through respiratory droplets. When an infected person coughs or sneezes, they expel tiny droplets carrying the virus. These droplets can travel farther than many people realize. Conventional wisdom says respiratory droplets travel about 6 feet. Modern research, accelerated by COVID studies, shows they can travel much farther, especially in air currents. But measles doesn't even rely primarily on droplets.

Measles spreads through aerosolized particles. These are so small and light that they can remain suspended in air for hours. A person with measles walks into a classroom in the morning. They leave that afternoon. The virus remains in the air. A different class enters the room later that day, and students breathe in the same air. That's how measles works. That's why it's so efficient.

This aerosol transmission explains why measles outbreaks concentrate in schools. Schools are ideal transmission environments: poorly ventilated buildings, high-density populations of children, extended contact times, and limited ability for individuals to distance themselves. A child with early measles symptoms—before the rash appears—goes to school, sits at a desk, participates in class. They're infectious but undetectable.

The virus's incubation period compounds the problem. In most people, symptoms begin 7 to 14 days after exposure. But the range extends to 21 days in some cases. This long incubation period means:

- An exposed child can return to school for a week or two without showing symptoms, continuing to transmit

- Contact tracing becomes nearly impossible because exposure occurred weeks earlier

- Health officials can't identify who exposed whom without detailed timeline reconstruction

- Multiple generations of transmission occur before anyone realizes there's a problem

Once symptoms begin, the virus is virulent. High fevers, often exceeding 103°F. The classic "three C's": cough, coryza (runny nose), and conjunctivitis (eye inflammation). About three to four days after these initial symptoms appear, the telltale Koplik spots develop inside the mouth. These tiny white spots surrounded by red halos are pathognomonic—meaning they're uniquely characteristic of measles. A day or two later, the rash appears, starting at the hairline and spreading downward across the body.

But here's the catch: by the time the rash appears, the window for early isolation has largely closed. The person has been infectious for four days already. They've been around family, classmates, coworkers. If they're unvaccinated and in a community with low vaccination rates, they've likely exposed a significant number of people.

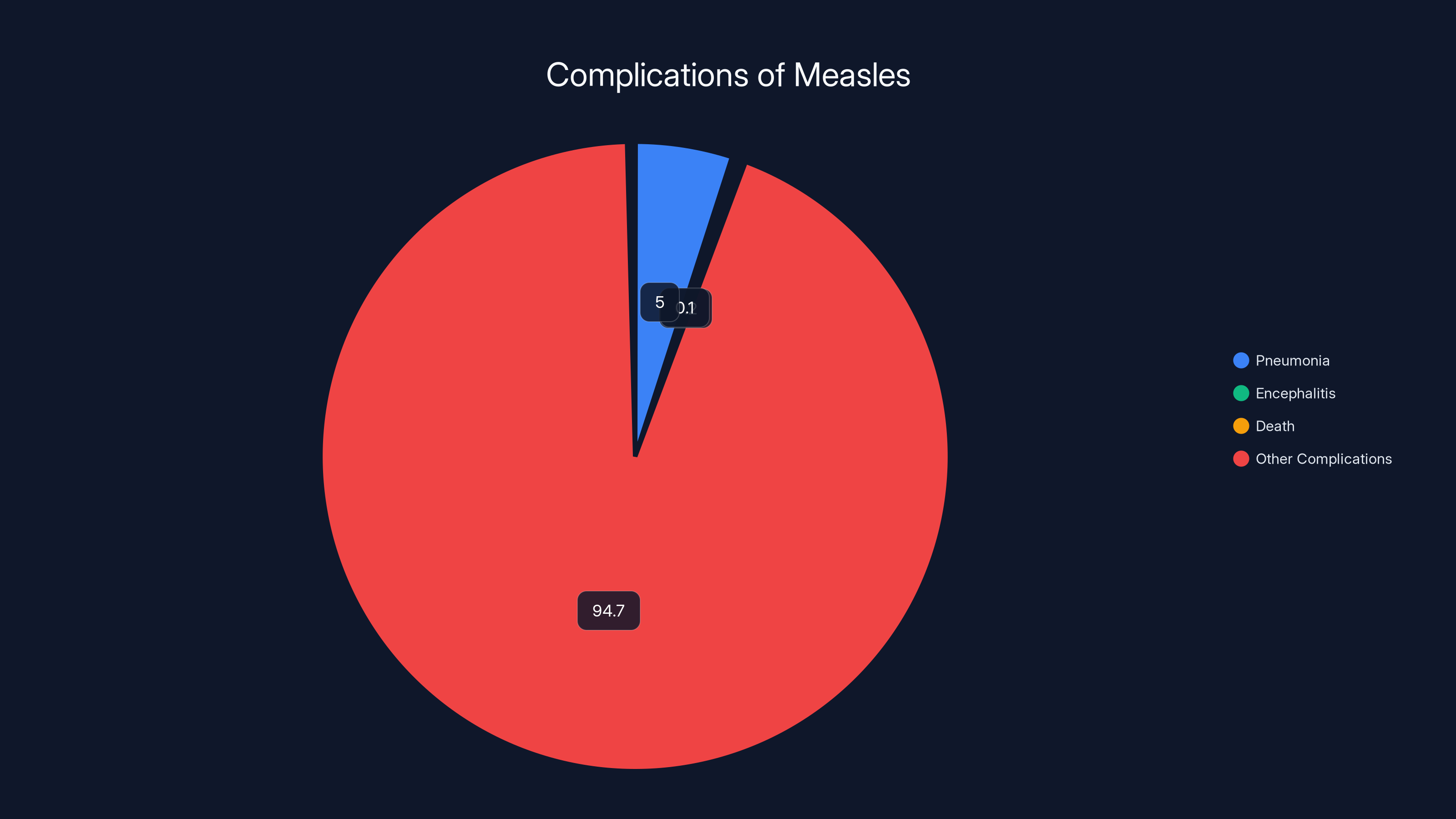

Measles is also unusual in its severity. It's not just an uncomfortable illness. Measles complications include pneumonia (occurring in about 1-6% of cases), encephalitis (brain inflammation, in about 1 per 1,000 cases), and in severe cases, death. The fatality rate for measles in developed countries is approximately 2 per 1,000 infected individuals. In 1991, the US experienced 55 measles deaths. That can happen again.

The Vaccination Status Problem: Why 97% of Cases Are Preventable

The statistics are damning. Among 789 cases in South Carolina, 769 were unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, or had undocumented vaccination status. That's 97.5%. In other words, nearly every single person who got measles during this outbreak could have been protected by a vaccine.

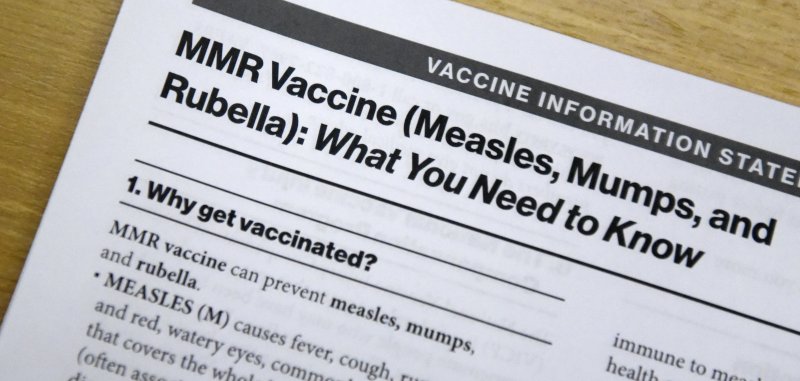

Two doses of the MMR vaccine provide 97% protection against measles. This is one of the highest efficacy rates for any vaccine. One dose provides about 93% protection. This means if you're vaccinated, your risk of infection after exposure is roughly 3%, and your risk of severe disease is even lower.

So why do we have 789 cases? Because vaccination rates have dropped. The data is murky on exactly how much coverage has declined in the affected areas, but national MMR vaccination rates have fallen from a high of 97.4% in 2009 to around 92-94% in recent years. That doesn't sound dramatic until you realize that measles elimination requires sustained coverage above 95%, preferably 97%.

Low vaccination rates create pockets of vulnerability. These pockets are often concentrated in specific geographic areas or communities. In South Carolina, the outbreak appears to be spreading through communities with religious or philosophical objections to vaccination, combined with communities experiencing healthcare access barriers.

When vaccination rates in a community fall below the herd immunity threshold, measles can spread freely. Herd immunity for measles requires about 95% of the population to be immune, either through vaccination or previous infection. South Carolina and the affected areas have clearly fallen below this threshold.

The historical context matters here. Measles killed thousands of Americans annually before the vaccine was introduced in 1963. From 1963 to 1970, measles deaths dropped by 95%. By the 1990s, measles was so rare that a single case made headlines. By 2000, we declared measles eliminated from the US.

Then came the anti-vaccine movement. Starting in the late 1990s, unfounded claims linked vaccines to autism and other conditions. Despite being thoroughly debunked, these claims persisted and spread. They found fertile ground in communities skeptical of pharmaceutical companies and government health agencies. Over the past two decades, vaccination rates gradually declined in pockets across the country.

Texas experienced the consequence in 2015. That outbreak occurred in a partially vaccinated religious community. It infected 2,255 people across multiple states before being contained. Now, in 2026, South Carolina is showing us that we haven't learned that lesson.

The tragedy is that measles is completely preventable. The vaccine is safe, effective, and inexpensive. A child who receives two MMR doses on the recommended schedule—first dose at 12-15 months, second dose at 4-6 years—will have lifelong protection. One injection. Two doses over five years. That's what stands between a healthy childhood and measles complications.

Measles has a significantly higher reproduction number (R0) compared to COVID-19 and seasonal flu, making it 6 to 9 times more contagious than COVID-19.

Transmission Timeline: From Exposure to Diagnosis

Understanding how measles spreads through time helps explain why outbreaks accelerate so quickly and why control is so difficult.

Day 0: Exposure occurs. An unvaccinated person is exposed to measles virus, usually through respiratory aerosols from an infected person. The infected person may not know they have measles yet. They feel fine. No symptoms. No rash. They're going about their day.

Days 1-4: The virus replicates in respiratory tissues. The exposed person is completely asymptomatic. They're contagious but show no signs of illness. They attend school, go to work, visit friends and family. Every contact is a potential exposure.

Days 5-10: Early symptoms begin. Fever, often high (101-104°F). Cough. Runny nose. Conjunctivitis making the eyes red and irritated. The person feels awful but assumes they have a cold or flu. They might stay home or might continue with activities, thinking they're not seriously ill. Still highly contagious.

Days 10-14: Koplik spots appear. For parents or healthcare workers who know what to look for, this is a diagnostic clue. But most people don't know these tiny white spots mean measles. The person is still infectious, still spreading the virus.

Days 11-12: The characteristic rash appears. It starts at the hairline and behind the ears, then spreads downward. At this point, most people seek medical care. A healthcare provider recognizes measles and isolation begins.

Days 11-14: Infectiousness window. Even after the rash appears, the person remains contagious for four more days. They're now at home, isolated, but the damage is done. They've infected an average of 12-18 people during the previous 10 days.

Days 15+: Patient recovers or develops complications. If complications occur—pneumonia, encephalitis—hospitalization is needed.

But here's where the timeline gets complex for disease control. Those 12-18 exposed people don't all get sick at the same time. Some develop symptoms 7 days after exposure. Others take 14 or 21 days. This staggered illness creates waves of new infections.

Imagine patient zero getting infected on January 1. By January 10, they're sick and isolated. But they've infected 15 people. By January 17-24, those 15 people develop symptoms (7-14 days after exposure). Each of them might have infected another 12-18 people during their asymptomatic infectious period. Suddenly we have 180-270 people sick, all tracing back to one original case, with spread occurring over three weeks.

This is exactly what we're seeing in South Carolina. The outbreak began in October with isolated cases. But by January, the wave of secondary and tertiary infections hit simultaneously. That's why cases jumped from 218 to 789 in a month. It wasn't a 262% increase in new exposures; it was the mathematical consequence of unchecked exponential transmission.

Geographic Spread: 13 States and Growing

Measles doesn't respect state lines. What starts in South Carolina spreads to neighboring states. What's contained to the Southeast migrates West. By late January, confirmed cases had been reported in 13 states.

The Southeast cluster centers on South Carolina but includes cases in Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, and Florida. These states share transportation corridors, family connections, and healthcare networks. An infected person travels from South Carolina to visit family in North Carolina. They stop at a gas station, a restaurant, a grocery store. Measles spreads.

The Western cluster is particularly concerning. Arizona and Utah are experiencing a large concurrent outbreak, with 457 combined cases reported. These cases include 66 reported in 2026 alone. The outbreak is concentrated at the Arizona-Utah border, suggesting a community-based source or a specific event that infected dozens of people.

Outlier cases have appeared in California, Idaho, Minnesota, Ohio, Oregon, and Washington. These represent both travel-related cases (people infected in South Carolina who traveled to other states) and community cases (local transmission in states not part of the original South Carolina cluster).

The national tally, last updated January 22, showed 416 confirmed cases. But that number was already outdated, missing the surge of South Carolina cases reported afterward. With South Carolina alone at 789 and other states still reporting, the true national total by late January likely exceeded 1,200 cases.

A staggering 97.5% of measles cases were among those unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, or with undocumented status, highlighting the critical role of vaccination in preventing outbreaks.

Public Locations and Community Spread: Grocery Stores to Post Offices

Measles exposures have been identified in eight public locations across South Carolina, expanding the outbreak beyond schools into the broader community.

Grocery stores top the list. These are high-traffic, poorly ventilated spaces where hundreds of people converge daily. A single infected person shopping during peak hours could expose dozens. People are touching common surfaces: shopping cart handles, product packages, checkout counters. They're in close proximity in narrow aisles. The ventilation systems, designed for temperature control rather than virus filtration, recirculate air continuously.

The US Post Office exposure is particularly concerning because postal workers interact with the public constantly, and customers represent a broad cross-section of the community. If a postal worker became infected, they could expose both coworkers and the steady stream of customers visiting that location.

A skating center appears on the exposure list. These are enclosed spaces with high-speed air circulation for ice production, creating ideal conditions for aerosol transmission. Hundreds of people spend hours there weekly, sharing equipment and space.

Beyond these specific locations, general community spread is occurring. Every exposure at a public location creates the potential for secondary exposures elsewhere. An infected person visits a grocery store, infects someone. That newly infected person goes to work, to school, to church. They infect others. By the time anyone realizes they have measles, weeks have passed and dozens or hundreds have been exposed.

This community transmission pattern is exactly what triggers elimination status revocation. When measles stops being imported from outside and starts spreading sustainably within communities, we've lost control. We've lost elimination status.

The Risk to Vulnerable Populations: Why Measles Hits Hardest

Not everyone experiences measles equally. Some populations face dramatically higher risks of severe disease and complications.

Infants under 12 months old cannot receive the MMR vaccine. They're completely vulnerable. An infant with measles faces roughly a 10% risk of pneumonia, a 1% risk of encephalitis, and a small but real risk of death. In developed countries with good medical care, we don't usually see measles deaths in infants, but it happens. In 2013, a 13-month-old died of measles in New York. In 2015, an infant died in Texas.

Pregnant women face special risks. Measles during pregnancy increases the risk of miscarriage and premature delivery. While the vaccine cannot be given during pregnancy, pregnant women who are unvaccinated are vulnerable. Many are unvaccinated by choice or were vaccinated before immunity testing became standard, so their immunity status is unknown.

People with compromised immune systems face the highest risk. This includes people with HIV or AIDS, people undergoing chemotherapy for cancer, people on immunosuppressant medications for autoimmune diseases or after organ transplantation. These individuals cannot receive live vaccines like MMR, so they depend entirely on herd immunity for protection. When vaccination rates drop, these vulnerable people lose their shield.

People with vitamin A deficiency experience more severe measles. While vitamin A deficiency is rare in developed countries, it occurs in some impoverished communities. A person with vitamin A deficiency who gets measles faces increased risk of corneal scarring and blindness.

Previously infected people theoretically have immunity, but immunity can wane over decades or be insufficient if only one prior infection occurred. Older adults who had measles as children usually remain immune, but some studies suggest a small percentage lose immunity over extremely long time periods.

The cumulative effect is concerning. In a population of 5 million people in South Carolina, roughly 500,000 are infants, very elderly, immunocompromised, or otherwise vulnerable. If measles reaches 2% of the population (100,000 cases), and 10% of those are in vulnerable groups (10,000 people), we'd expect to see dozens of deaths and thousands of permanent disabilities from complications.

Pneumonia occurs in about 5% of measles cases, while encephalitis and death are rarer but serious complications. Estimated data.

Healthcare System Burden: Hospitals and Emergency Departments

Measles outbreaks create a cascade of healthcare system strain. It's not just the measles cases themselves, though those demand resources. It's the complications, the quarantined contacts being monitored, the worried parents calling their pediatricians, the emergency department visits from people unsure whether they have measles or something else.

Complications occur in a small percentage of cases but still represent substantial numbers. Pneumonia develops in 1-6% of measles cases. In 789 cases, that's 8-47 pneumonia cases. Encephalitis (brain inflammation) occurs in about 1 per 1,000 cases. That's less than one case per 1,000, but in a population of 789, we'd expect to see zero to one case. When it does occur, it's severe: high fever, seizures, potential permanent neurological damage.

Otitis media (ear infection) is very common, occurring in 7-9% of cases. That's 55-71 ear infections requiring evaluation. Diarrhea occurs in 8% of cases. While usually self-limiting, diarrhea contributes to dehydration and secondary illness.

Myocarditis (heart inflammation) is rare but serious. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is an extremely rare late complication that develops months or years after measles, causing progressive neurological deterioration and death. It occurs in about 1 per 10,000 cases.

The hospitalization rate for measles varies but generally ranges from 1-2 per 1,000 cases. For 789 cases, we'd expect 1-2 hospitalizations. But in severe outbreaks with high rates of complications, hospitalization rates can reach 3-4 per 1,000. If we see 3 hospitalizations per 1,000 cases in South Carolina, we'd expect 2-3 hospitalizations.

Each hospitalization consumes resources: hospital beds, nursing staff, physicians, imaging studies, laboratory tests. Pediatric intensive care units become strained. During the 2015 Texas outbreak, some hospitals reported having to cancel elective procedures to manage the measles complications.

Beyond direct measles care, healthcare systems face the burden of managing quarantined contacts. Health departments must conduct contact tracing, identify exposed individuals, and monitor them for symptoms. This requires administrative staff, nurse hotlines, follow-up coordination. In South Carolina, with 557 students officially quarantined and many more contacts to be traced, the contact tracing burden is enormous.

Economic Impact: More Than Medical Costs

Measles outbreaks create economic consequences far beyond direct healthcare spending.

School closures or reduced attendance disrupts childcare, forcing parents to take unpaid leave or arrange childcare coverage. South Carolina's 557 quarantined students represent 557 families managing absence and isolation. Some parents must stop working. Others cobble together childcare from family. The broader community experiences economic strain.

Businesses suffer reduced revenue when employees call out sick or must stay home with quarantined children. A grocery store worker with measles might infect coworkers, leading to multiple callouts. A restaurant suffers closure when it discovers an exposed employee.

Productivity losses mount. Even people who don't develop measles but are quarantined as contacts lose 21 days of work or school. A worker might return to find missed meetings, accumulated emails, disrupted projects. The learning loss for students is harder to quantify but real: 557 students missing 21 days of school each represents roughly 120,000 lost student-days of education.

Public health agencies face increased costs. Contact tracing, quarantine monitoring, education and outreach campaigns all cost money. Health departments already stretched thin must divert resources from other public health programs.

Vaccination campaigns to prevent further spread require investment: public service announcements, healthcare provider outreach, vaccination clinics, staffing. South Carolina likely will need to conduct an intensive campaign to reach unvaccinated individuals and improve coverage.

The 2015 Texas outbreak cost an estimated $22-26 million in direct healthcare costs alone. Indirect costs—lost productivity, school disruption, public health response—probably doubled that total. A measles outbreak in 2026 would cost more due to inflation and the current size of the outbreak.

The chart shows the distribution of quarantined students across 20 schools, with numbers ranging from 13 to 59. Estimated data.

The Path to Elimination Status Loss: Understanding the Stakes

Measles elimination from the US was declared in 2000. That meant no endemic transmission of the virus—measles could be imported, but it wasn't spreading sustainably within American communities. That status is now at risk.

Elimination status is determined by the World Health Organization. Loss of elimination status is not automatic. It follows a determination that the disease is again circulating endemically. For measles, that generally means sustained transmission for more than 12 months in a geographic region.

We're not there yet. South Carolina's outbreak began in October 2025 and accelerated dramatically in January 2026. If it continues unabated through spring, summer, and into fall 2026, that would constitute endemic circulation. Loss of elimination status would likely follow.

Why does this matter beyond national prestige? It signals to the world and to potential vaccine manufacturers that measles is again an American disease problem. Immunization priorities shift. Advocacy organizations focus on measles prevention. Resources flow toward surveillance and vaccination campaigns.

It signals vulnerability. If we've lost elimination status for measles, what else might return? Polio was eliminated in the US in 1994. That status remains, but it's fragile. Circulation continues globally. If measles returns to endemic status, it suggests our immunization infrastructure has weakened and other diseases might follow.

Historically, measles elimination has been lost before. Parts of Europe experienced measles resurgence in the 2010s due to declining vaccination rates. Elimination status was revoked in some regions. It took years of intensive vaccination campaigns to regain that status.

Losing measles elimination status would represent a 25-year regression in public health achievement. We've been here before. We know the path back. But it's long and requires sustained commitment.

Historical Context: 1991 and 2015 Compared

Measles outbreaks in America have history. Understanding that history helps contextualize what's happening now.

The 1991 outbreak was the largest measles outbreak in the US in decades. It resulted in 55,000 cases across the country. Most cases occurred in California, Texas, and New York. The outbreak revealed a vaccination coverage gap: unvaccinated preschool children in urban areas. Vaccination rates in some inner-city schools had fallen to 40-50%.

The 1991 outbreak prompted a national response. The CDC launched the Measles Elimination Plan. Schools were required to verify immunity for all students before attendance. Vaccination requirements were strengthened. Healthcare providers were educated about measles recognition. Within a decade, measles cases had dropped dramatically.

The 2015 Texas outbreak was smaller but more significant culturally. 2,255 cases across multiple states, but the outbreak originated in a community where vaccination was uncommon due to religious beliefs. The outbreak highlighted how community-based vaccine hesitancy could seed outbreaks in modern America.

The 2015 outbreak occurred in the post-Wakefield era. Andrew Wakefield's fraudulent 1998 study linking vaccines to autism had been retracted, proven fraudulent, and rejected by the medical community. Yet the anti-vaccine narrative persisted. The Texas outbreak showed that vaccine hesitancy had taken root in American communities.

Now, in 2026, we're seeing a third major outbreak. It's larger and faster than the 2015 outbreak. It's affecting school-age children, community-wide spread, multi-state cases. And it's happening against a backdrop of continued vaccine hesitancy, declining vaccination rates, and reduced trust in health institutions.

Each outbreak teaches a lesson. The 1991 outbreak taught us that vaccination infrastructure matters. The 2015 outbreak taught us that cultural narratives shape vaccination decisions. This 2026 outbreak is teaching us that progress is fragile and reversible.

What Triggers Rapid Acceleration? The Super-Spreader Effect

Outbreaks don't spread uniformly. Some individuals cause disproportionate transmission. These "super-spreaders" are responsible for large percentages of cases despite being small percentages of the infected population.

Super-spreader events create explosive growth. A single person attends a large gathering—a religious service, a family reunion, a school event. They're infected but asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic. They interact with dozens or hundreds of people. Dozens or hundreds become infected, each of whom infects others.

In South Carolina's outbreak, the jump from 218 cases on December 28 to 789 cases by January 27 likely involved one or more super-spreader events. Perhaps a large religious gathering where an infected person attended. Perhaps a school event with multiple attendees from different schools. Perhaps a workplace where an infected employee worked while symptomatic but unaware of diagnosis.

Super-spreader events are unpredictable in timing but predictable in consequence. High-density spaces with poor ventilation, long dwell times, and close contact create conditions for super-spreading. Schools fit this profile. Large indoor gatherings fit this profile. Public transportation fits this profile.

The January acceleration in South Carolina almost certainly involved super-spreader events. Health investigators are likely trying to identify them now, asking patients where they traveled, what events they attended, who they were in contact with. But by the time super-spreader events are identified, the damage is done. The contacts of those attendees are already infected and spreading to others.

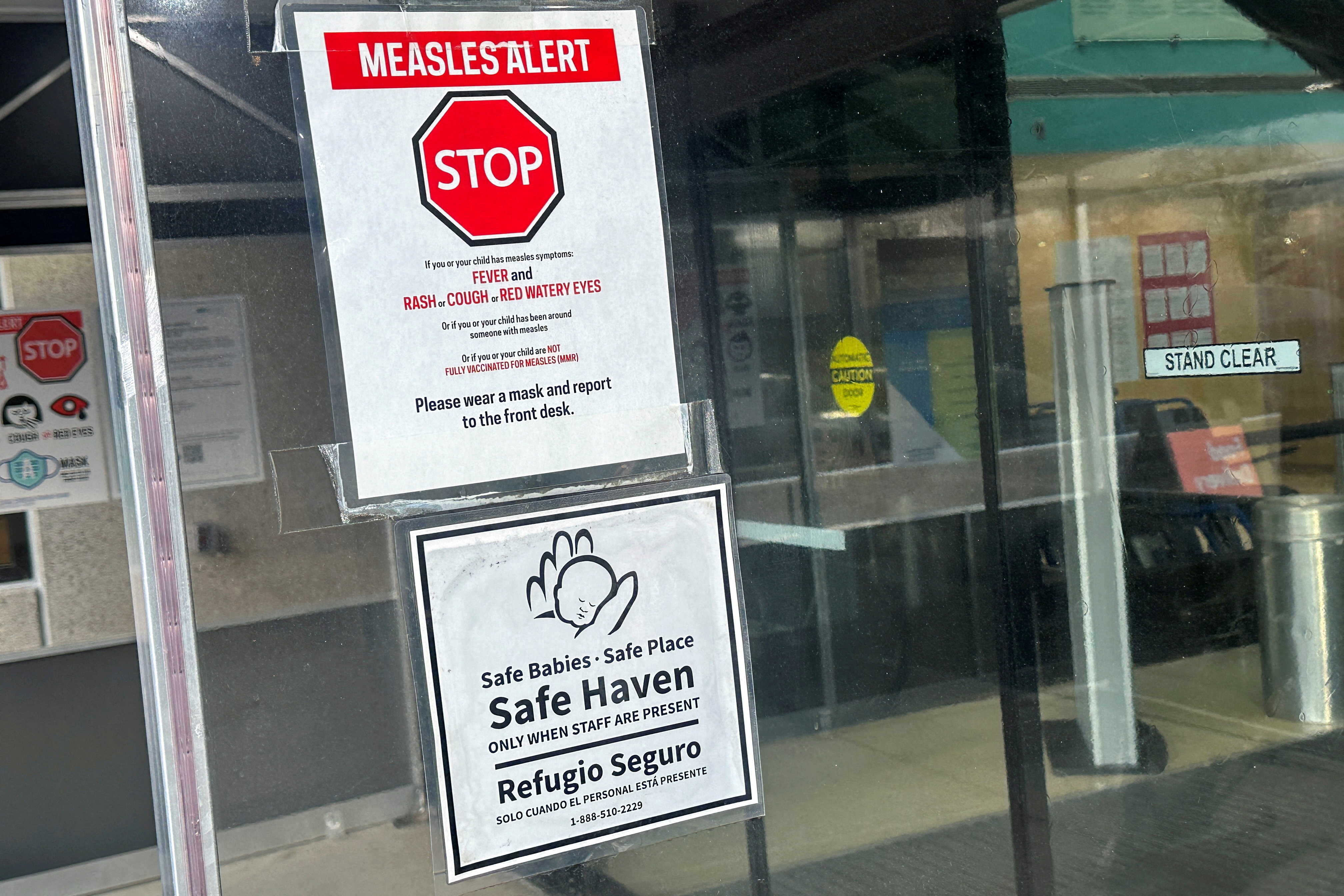

Public Health Response: Quarantine, Isolation, and Vaccination

South Carolina's public health department faces an enormous challenge. With nearly 800 cases and 13 states affected, the response requires coordination across multiple agencies and jurisdictions.

Quarantine is the primary containment tool for exposed contacts. Unvaccinated individuals exposed to measles are quarantined for 21 days from the date of exposure. This is the standard incubation period, covering even the longest possible exposure-to-symptom window.

557 students quarantined represents an enormous logistical undertaking. Schools must identify which students were in the same classes or shared space with infected individuals. Exposure is determined by proximity and duration: being in the same room for 15 minutes or more. Schools are erring on the side of caution, quarantining more students than might be absolutely necessary, accepting overreach to prevent missed cases.

Isolation is different from quarantine. Isolation applies to confirmed cases. Confirmed measles patients must isolate for at least four days after the rash appears, preventing further transmission. During this period, they cannot attend school or work. They're separated from family members when possible. Family members are quarantined, even if not yet symptomatic.

Vaccination acceleration is the long-term response. Health departments are conducting outreach to unvaccinated individuals and partially vaccinated individuals. Catch-up clinics are being organized. Schools are verifying immunity status and requiring vaccination for unvaccinated students.

Education is crucial. Many people don't understand why quarantine is necessary for asymptomatic contacts. Public health messaging must explain that an unvaccinated person exposed to measles has a 90% chance of developing measles. They'll be contagious before symptoms appear. Quarantine prevents transmission while they incubate.

The Anti-Vaccine Movement's Role: How We Got Here

This outbreak doesn't occur in a vacuum. It's the consequence of decades of vaccine hesitancy and active anti-vaccine advocacy.

The anti-vaccine movement gained significant momentum after Andrew Wakefield's 1998 study claiming a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The study was fraudulent—Wakefield falsified data, had undisclosed financial conflicts of interest, and enrolled patients unethically. The study was retracted in 2010, and Wakefield lost his medical license.

Despite being thoroughly debunked, the vaccine-autism narrative persisted. It found audiences among parents worried about their children's health, seeking explanations for autism (which has increasing prevalence due to improved diagnosis, not vaccine causation), and skeptical of pharmaceutical industry and government health agencies.

Online platforms amplified anti-vaccine messaging. Facebook groups, Instagram communities, Tik Tok videos—these created echo chambers where vaccine hesitancy reinforced itself. Misinformation spread faster than fact-checking could debunk it.

Philosophical and religious vaccine objections increased. Some communities viewed vaccination as pharmaceutical intervention in natural development. Some believed disease was meant to be encountered naturally for immune system strengthening. Some religious groups objected to vaccines on theological grounds.

Healthcare provider hesitation contributed. Some providers, facing vaccine-hesitant parents, didn't strongly advocate for vaccination. Others provided exemptions too easily. The CDC didn't mandate vaccination; it recommended it. Recommendations are easier to decline than mandates.

COVID-19 accelerated vaccine hesitancy. The rapid development of COVID vaccines and politicization of vaccination left lasting impact. People who accepted previous vaccines became hesitant about new vaccines. Distrust of health institutions deepened.

The consequence is that we've entered an era where MMR vaccination rates have declined, pockets of low vaccination exist in multiple regions, and herd immunity is breaking down. Measles, which we thought was gone, has returned.

Overcoming vaccine hesitancy requires sustained effort. It requires addressing legitimate vaccine safety concerns (side effects are real but rare and usually mild). It requires rebuilding trust in health institutions. It requires understanding the cultural and religious contexts that shape vaccination decisions. It requires patience and persistence.

Looking Forward: Predictions and Trajectories

If current trends continue, South Carolina's outbreak will reach 1,200-1,500 cases by mid-February and could exceed 2,000 cases by March. The national total across all states could reach 3,000-4,000 cases by spring.

But that's not inevitable. Public health interventions can slow or stop transmission. Increased vaccination rates reduce the pool of susceptible people. Each newly vaccinated person is one fewer person who can get infected and spread measles to others.

The trajectory depends on vaccination rate changes. If vaccination rates increase rapidly—say, from 92% to 95% in affected areas—the outbreak could peak in March and decline by summer. If vaccination rates remain unchanged or increase slowly, the outbreak could sustain through summer and into fall.

Geographic spread will likely continue. Measles cases will appear in more states. Border states are at highest risk. Multi-state transmission is inevitable without extraordinary measures.

By fall 2026, we could be looking at elimination status loss. That assessment will depend on WHO criteria and ongoing transmission at that time. If we see sustained endemic transmission through autumn, elimination status is likely revoked.

The best-case scenario involves rapid response. Health departments accelerate vaccination clinics. Schools require proof of immunity. Vaccination rates climb to 97%+. New cases decline. By spring 2027, we've controlled the outbreak.

The worst-case scenario involves sustained transmission through 2026. Measles becomes endemic again. Elimination status is revoked. We spend the next three to five years rebuilding vaccination programs and regaining elimination status.

The realistic scenario falls between. The outbreak continues through spring, peaks in late winter or early spring, then gradually declines through summer as vaccination rates improve. We maintain near-elimination status but experience thousands of preventable cases and hundreds of preventable complications.

Prevention: The Argument for Vaccination

Prevention is always superior to treatment. Measles is preventable. The MMR vaccine has been available for decades. It's safe and effective.

Two doses of MMR provide 97% protection against measles. One dose provides 93% protection. This isn't theoretical; it's based on decades of experience with hundreds of millions of vaccinated people. The protection is durable. It lasts a lifetime. A person vaccinated as a child and checked 50 years later retains immunity.

Side effects are mild and temporary for the vast majority of people. Pain or redness at injection site (very common). Low-grade fever (common). Joint pain (more common in adults). Rash (rare). Severe allergic reaction (extremely rare, about 1 per million doses).

Compare this to measles. High fever, often exceeding 103°F. Severe cough. Respiratory distress. Rash covering the entire body. Pneumonia in 1-6% of cases. Encephalitis in 0.1% of cases. Potential death. The risk-benefit analysis is overwhelmingly in favor of vaccination.

For infants too young for vaccination, vaccination of contacts and community members provides protection through herd immunity. An infant whose older siblings, parents, and community members are vaccinated is protected by the immunity barrier around them.

For pregnant women, pre-conception vaccination is essential. Two doses of MMR provide lifetime protection. A vaccinated woman who becomes pregnant is protected and doesn't need the vaccine during pregnancy (it's contraindicated).

For immunocompromised people, other people's vaccination is literally lifesaving. These individuals depend entirely on herd immunity. They cannot be vaccinated themselves (live vaccine is contraindicated). Their protection comes from the vaccination status of everyone around them.

Lessons for Future Preparedness

This outbreak teaches lessons that extend beyond measles.

Vaccination infrastructure is fragile. We can't take high vaccination rates for granted. Rates decline when vigilance decreases. When disease becomes rare, people forget why vaccination mattered. Without active surveillance, outreach, and community trust, vaccination rates drift downward.

Misinformation spreads faster than facts. Social media algorithms amplify sensational claims over nuanced scientific explanations. Debunking is slower and less engaging than the original claim. Public health agencies must invest in communication infrastructure to counter misinformation proactively.

Community engagement is essential. Vaccination programs that work impose requirements but also engage communities. They address concerns. They work with community leaders. They adapt to cultural contexts. Top-down approaches that ignore community perspectives generate resistance.

Vulnerable populations need targeted support. Immunocompromised people, infants, pregnant women—these groups depend on others' vaccination. Public health efforts must specifically protect these vulnerable populations.

International surveillance matters. Most measles cases are imported from other countries. With global measles circulation, we're vulnerable. Supporting vaccination programs globally isn't charity; it's self-defense.

This outbreak will shape public health policy for years. Vaccination requirements will likely be strengthened. School exemptions for non-medical reasons may be restricted. Healthcare provider licensing may include immunization advocacy requirements. The pendulum is swinging back toward mandates after decades of permissive approaches.

FAQ

What is measles and how serious is it?

Measles is a viral infection that causes fever, cough, runny nose, eye inflammation, and characteristic rash. While it might sound like a cold, measles is far more serious. Complications include pneumonia (occurring in 1-6% of cases), brain inflammation (encephalitis), and in severe cases, death. Before the vaccine was available in 1963, measles killed hundreds of Americans annually.

How does measles spread?

Measles spreads through respiratory droplets and aerosolized particles. When an infected person coughs or sneezes, they expel virus into the air. These particles can remain suspended in a room for up to two hours. An unvaccinated person breathing that air can become infected. Among unvaccinated people exposed to measles, approximately 90% will develop the disease. This makes measles one of the most contagious viruses known to medicine.

Why is the South Carolina outbreak spreading so rapidly?

The outbreak is spreading rapidly due to several factors converging. First, vaccination rates in affected areas have declined below the herd immunity threshold of 95%. This creates pockets of susceptible people. Second, the virus's long incubation period (up to 21 days) means infected people transmit disease before symptoms appear. Third, super-spreader events in December likely seeded widespread simultaneous transmission that exploded in January as infected contacts developed symptoms.

Am I protected if I had one dose of the MMR vaccine?

One dose of MMR provides about 93% protection against measles. Two doses provide 97% protection. If you received only one dose, you have significant protection but aren't fully protected. Consult your doctor about whether you need a second dose. Many adults who received only one dose decades ago fall into this category.

What should I do if I think I have measles?

If you develop high fever and rash, especially if you have cough, runny nose, or eye inflammation, call your doctor immediately. Don't visit the clinic without warning—call first so staff can prepare for a potential measles case and take precautions. Don't visit the emergency department without calling ahead. Provide information about your vaccination status and any known exposures. Isolation at home is necessary to prevent spreading to others.

How long will the South Carolina outbreak continue?

The trajectory depends on vaccination rate changes. If vaccination rates increase rapidly and public health measures are effective, the outbreak could peak in February or March and decline through spring. If vaccination rates increase slowly, the outbreak could sustain through summer and into fall. Realistically, public health agencies will bring the outbreak under control by late spring or early summer 2026, but not before thousands of additional cases occur.

Can I catch measles if I'm vaccinated?

If you've received two doses of MMR vaccine, your risk of infection after exposure is approximately 3%. If you get infected despite vaccination, your illness is typically milder than measles in unvaccinated people. You might develop mild symptoms or no symptoms. Vaccination doesn't guarantee protection, but it dramatically reduces risk and severity.

Why don't we just give everyone measles to build natural immunity?

This approach, called "getting exposed," was common before vaccines were available and killed people. Measles kills about 2 per 1,000 infected people in developed countries and 10 per 1,000 in developing countries. It causes encephalitis in 0.1% of cases and pneumonia in 1-6% of cases. The vaccine provides 97% protection with only mild side effects. Comparing natural infection to vaccination is like comparing Russian roulette to a lottery ticket.

What will happen to measles elimination status if the outbreak continues?

Measles elimination status is revoked if endemic transmission is sustained for more than 12 months. If South Carolina's outbreak continues through 2026 without control, elimination status would likely be revoked. This would signal to the world that measles is again circulating endemically in the US and would require renewed vaccination efforts to regain elimination status—a process that takes years.

Where can I get vaccinated against measles?

Contact your primary care doctor, local health department, or urgent care clinic. Most healthcare providers stock MMR vaccine. Vaccination is also available at pharmacies in many locations. If you're unvaccinated or don't know your vaccination status, schedule an appointment today. If you're concerned about cost, many public health clinics provide free or low-cost vaccination. Check your local health department website for vaccination clinic schedules.

How do I know if I'm immune to measles?

If you received two doses of MMR vaccine and have documentation, you're immune. If you're unsure of your vaccination status, a blood test can check for measles antibodies. This test costs $50-100 and definitively determines if you're immune. If the test shows you're not immune, you can get vaccinated. Immunity develops within two weeks of vaccination.

Key Takeaways

- South Carolina's measles outbreak has reached 789 confirmed cases, surpassing Texas's previous record of 762 cases from 2015

- Cases jumped 262% in January alone (from 218 on Dec 28 to 789 by Jan 27), indicating accelerating community transmission

- 97% of cases involved unvaccinated or partially vaccinated individuals, demonstrating vaccine effectiveness and low coverage in affected areas

- Measles is 6-9 times more contagious than COVID-19 with R0 of 12-18, and can linger in air for 2 hours, creating massive transmission potential

- 557 students are quarantined across 23 schools, with exposures also identified in 8 public locations including grocery stores and post offices

- The US risks losing its measles elimination status if endemic transmission continues through 2026, a designation held since 2000

- The outbreak demonstrates how quickly vaccine-preventable diseases can resurge when vaccination rates fall below the 95% herd immunity threshold

![South Carolina's Measles Outbreak Hits Record Breaking 789 Cases [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/south-carolina-s-measles-outbreak-hits-record-breaking-789-c/image-1-1769622447637.jpg)