The CDC's Leadership Vacuum: A Public Health Emergency in the Making

Something fundamental broke at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Not the equipment. Not the science. The leadership.

Right now, the CDC doesn't have a permanent director. Instead, it has a rotating cast of acting leaders trying to steer one of the world's most critical public health agencies without the authority, accountability, or permanence that comes with Senate confirmation. This isn't a minor administrative hiccup. This is an agency running on fumes, losing experienced staff by the thousands, and struggling to maintain basic surveillance of infectious diseases while the nation watches and waits.

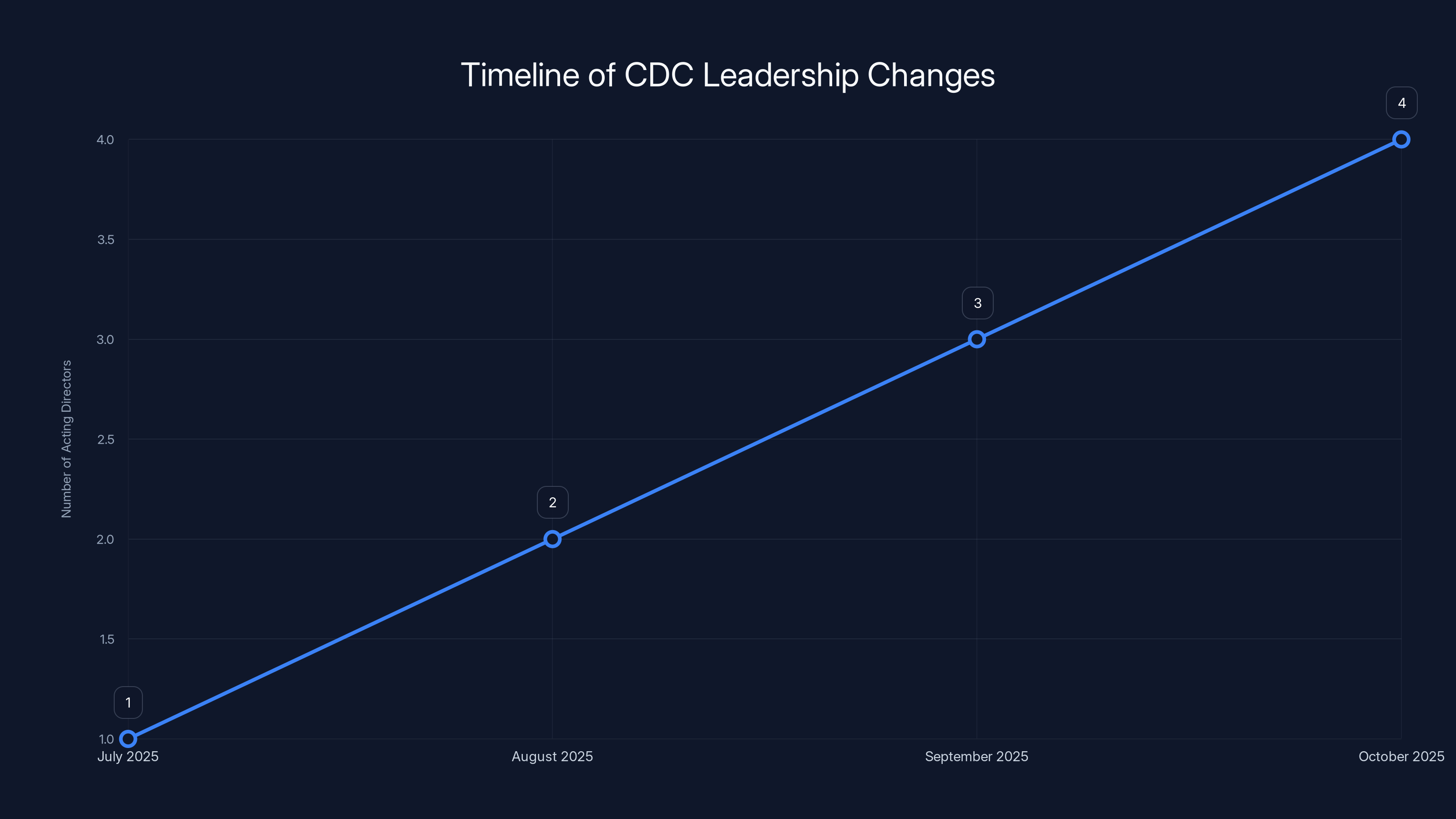

The crisis came to a head recently when Jay Bhattacharya, the director of the National Institutes of Health, was asked to serve as acting CDC director on top of his existing role. Bhattacharya took over after Jim O'Neill's departure in a week that saw O'Neill promoted to lead the National Science Foundation. Before that, Susan Monarez had held the position for just four weeks before being fired. Before her, the agency cycled through temporary leaders trying to maintain operations under unprecedented pressure.

This isn't chaos by accident. It's the result of a specific law passed in 2023, a political calculation about checking CDC power, and an administration determined to reshape federal health policy with or without permanent Senate-confirmed leadership. The story of what's happening at the CDC right now is a window into how governance breaks down, how institutions lose credibility, and what happens when political ideology clashes directly with public health expertise.

Here's what you need to understand about the leadership crisis at the CDC, why it happened, and what happens next.

TL; DR

- The Core Problem: The CDC has been operating without a permanent Senate-confirmed director for months, relying instead on acting leaders juggling multiple agencies simultaneously

- The 2023 Law: Republican-led Senate confirmation requirement was intended to check CDC power but has become a political bottleneck preventing permanent leadership

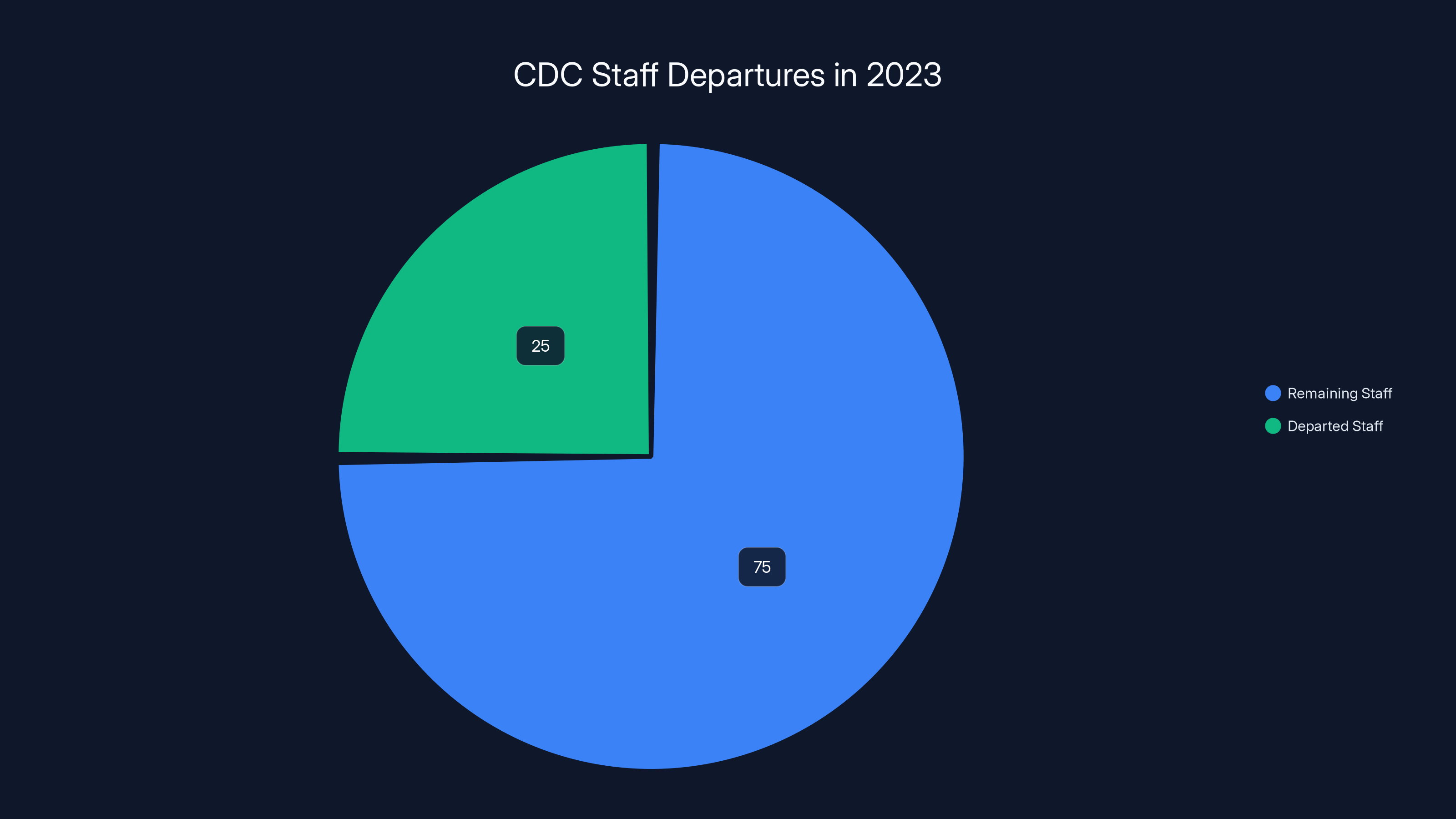

- The Body Count: Approximately 25% of CDC staff have departed through layoffs and resignations, including many senior scientists and epidemiologists

- The Fallout: Measles surveillance data delayed, vaccine guidance unclear, state health departments losing federal support, and critical pandemic preparation neglected

- Bottom Line: An agency managing infectious disease surveillance, outbreak response, and vaccine policy for the nation is operating in permanent leadership limbo with no clear timeline for change

The CDC has experienced a rapid turnover in leadership, with multiple acting directors serving in a short period. Estimated data reflects the instability in leadership roles.

Understanding the Senate Confirmation Requirement and Its Origins

To understand why the CDC finds itself without a permanent director, you need to go back to 2023 and the political decision made by Republican senators about how federal health agencies should be governed.

For decades, the CDC director was appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, like cabinet secretaries and other high-ranking officials. But the specific requirement that codified this into law didn't exist until recently. It came from Senator Ted Cruz and other Republican leaders who believed the CDC had overstepped during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Their argument was straightforward: the CDC had "unchecked power." The agency made decisions about masking, school closures, vaccine guidance, and testing protocols that affected millions of Americans. Without Senate confirmation, they argued, there was no accountability mechanism. A powerful agency was being run by someone the Senate never voted on.

So they pushed through a law requiring the CDC director to be confirmed by the Senate. The intention, at least in theory, was to add oversight. To make sure whoever ran the CDC had to convince senators they were qualified and reasonable. To prevent a single appointed official from wielding too much power over national health policy.

What actually happened was different.

The Senate confirmation requirement became a tool for political leverage. When an administration proposes a CDC director that senators believe won't pursue their preferred health policies, they can block the nomination. Or, as currently happening, an administration can simply avoid nominating anyone permanent, instead cycling through acting leaders who can pursue the same agenda without the same scrutiny.

This is the core paradox: the law designed to check CDC power has instead created a vacuum where no permanent, accountable leader exists. And the administration is using that vacuum strategically.

The Original Nominee Who Never Was: Dave Weldon and the Vaccine Skepticism Question

The Trump administration's first choice to lead the CDC was Dave Weldon, a former congressman from Florida and physician who has been outspoken about vaccine safety concerns.

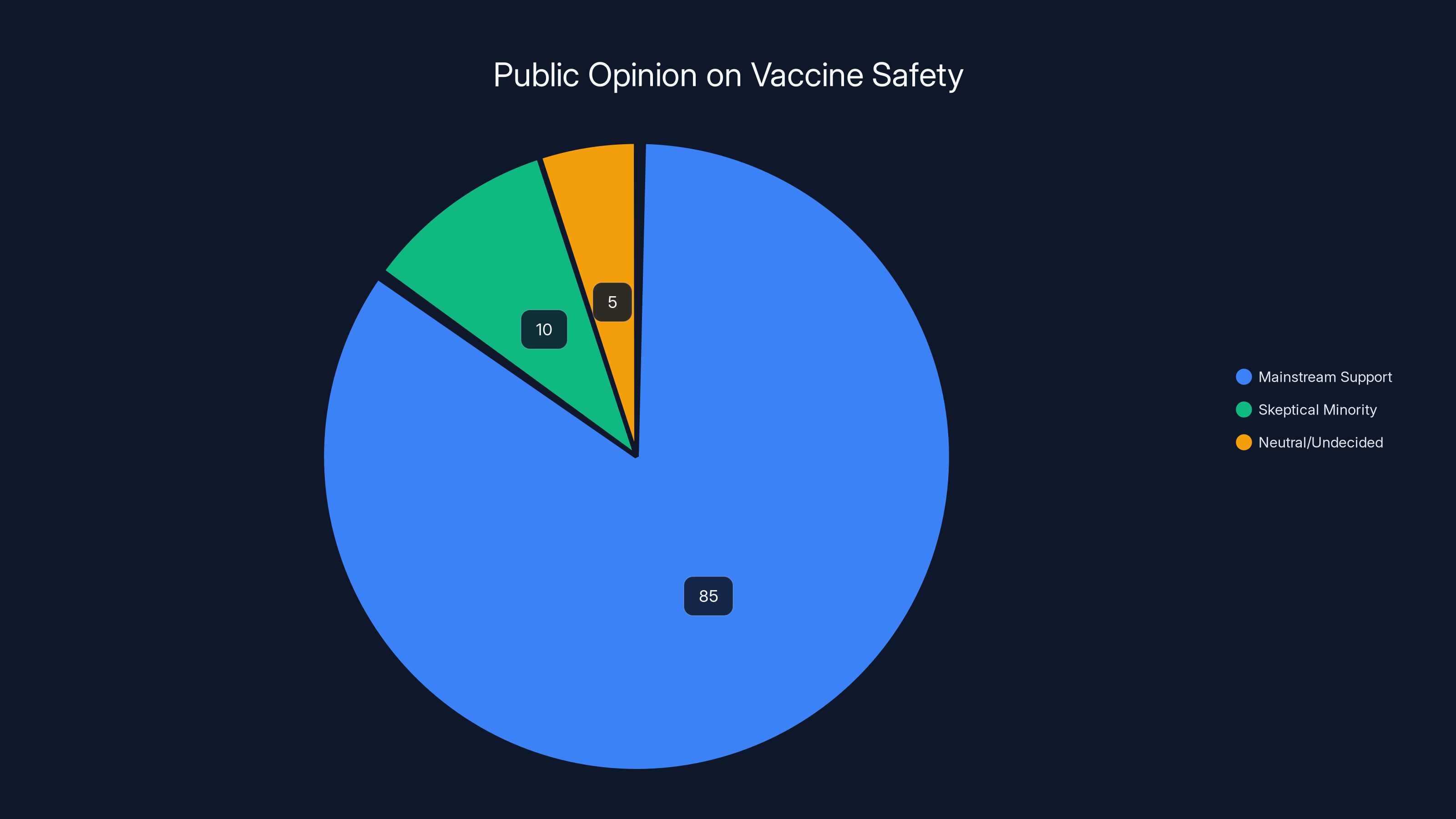

Weldon's credentials looked traditional: a medical degree, years in Congress, a background in health policy. But his public positions on vaccines diverged sharply from the scientific mainstream. His skepticism about vaccine safety and efficacy, when examined closely, reflected the views of a vocal minority in the medical community rather than the consensus position supported by decades of clinical data and epidemiological studies.

When the nomination became public, the math on Senate confirmation became clear almost immediately. Even with Republican control of the chamber, there weren't enough votes. Some Republicans with medical backgrounds weren't comfortable with the nomination. The optics of installing a vaccine skeptic at the helm of the nation's disease control agency created problems even for GOP senators representing conservative districts where vaccination rates are high and memories of measles outbreaks are fresh.

The White House, facing the prospect of a public rejection, withdrew the nomination. Weldon never got a hearing. Never had to defend his positions under oath. And the door opened for the carousel of acting directors.

This matters because it shows the real constraint at work: the administration has an ideology it wants to implement at the CDC, but it can't find a permanent nominee who can actually get confirmed while maintaining that ideology. So it uses the acting director route instead.

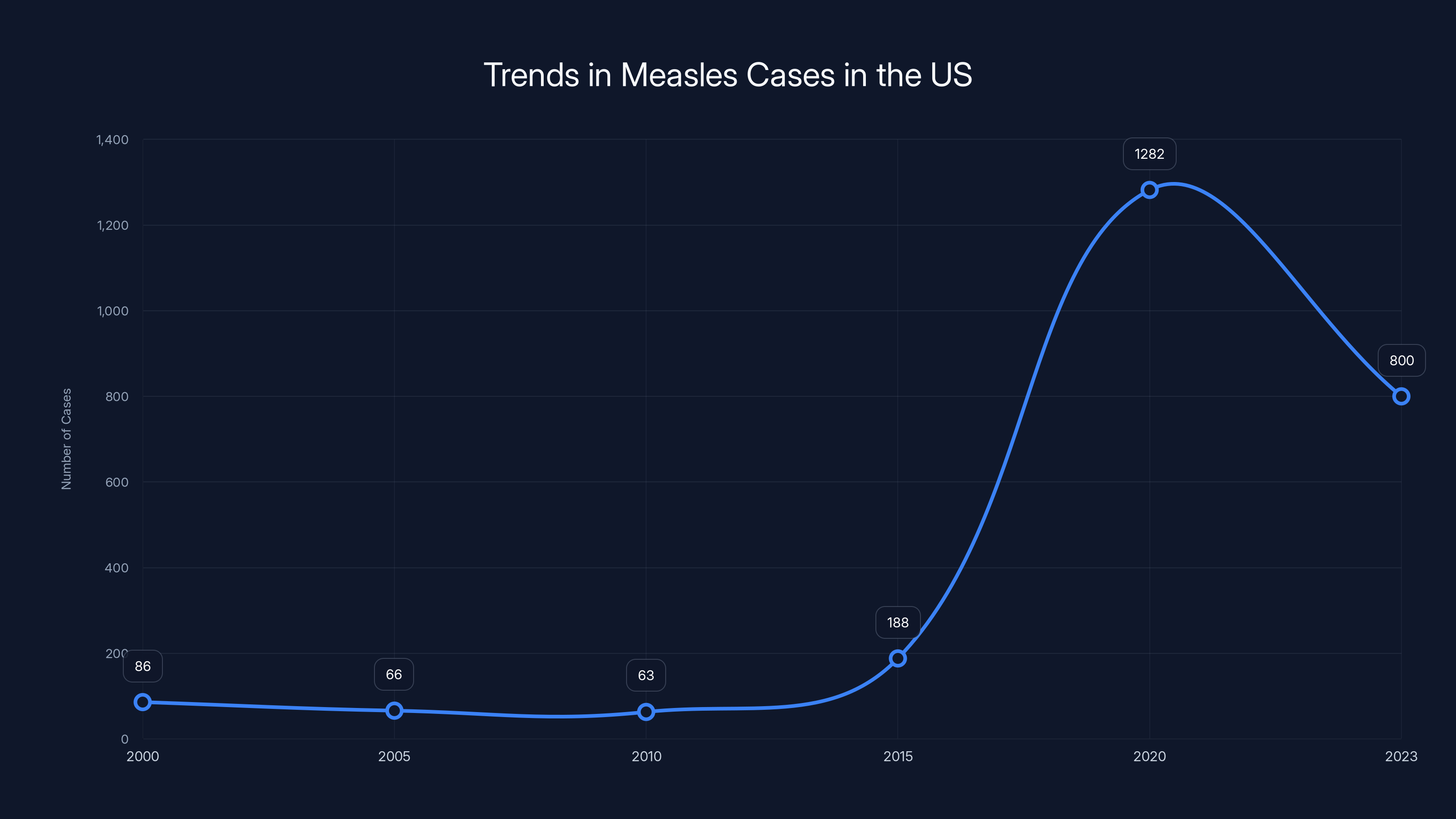

The number of measles cases in the US saw a significant increase in 2019, highlighting the impact of surveillance and vaccination challenges. Estimated data for 2023 shows a potential decrease due to increased awareness and vaccination efforts.

Susan Monarez's Four-Week Tenure: What Happens When a Director Refuses to Fall in Line

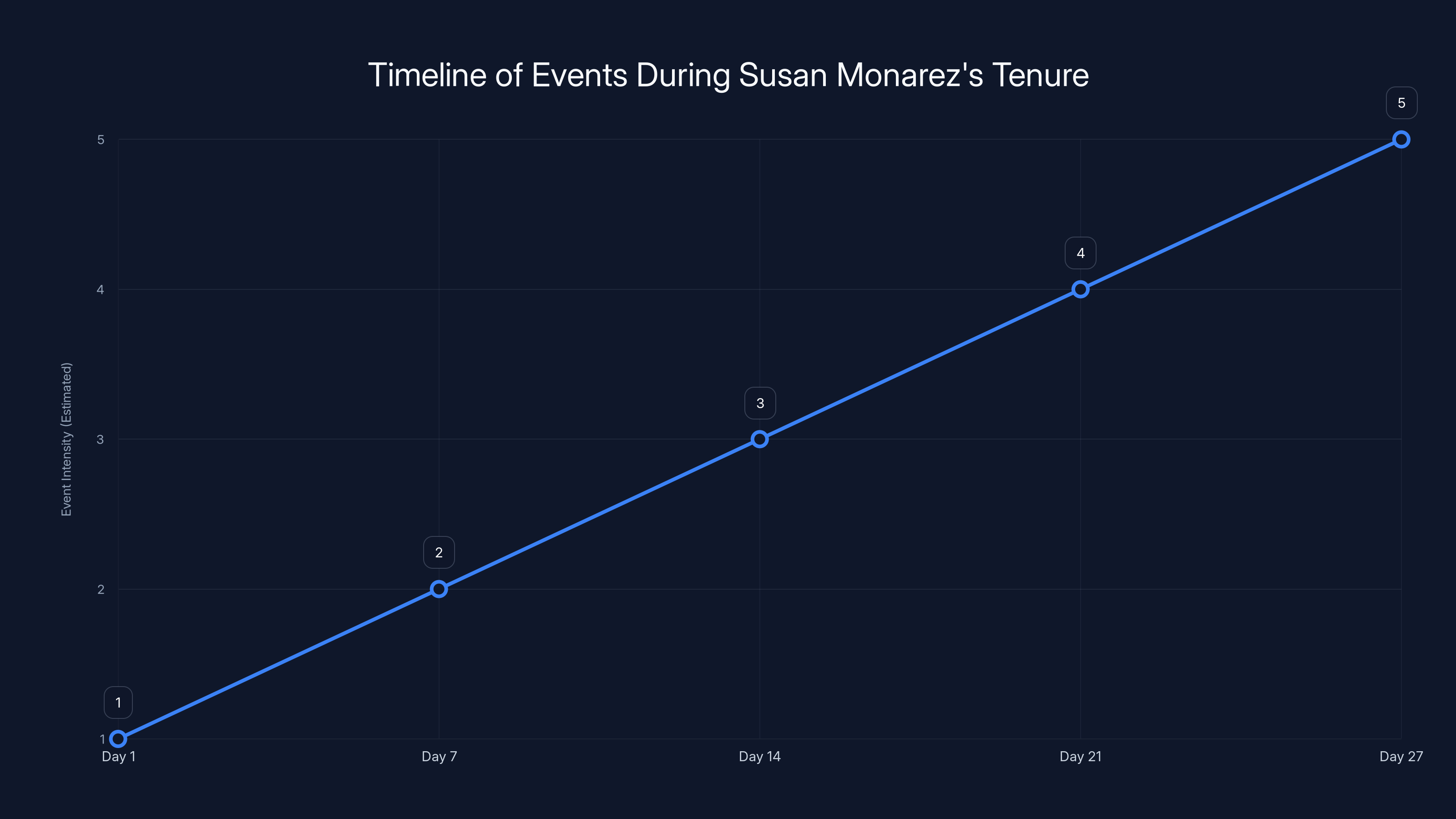

Susan Monarez lasted exactly 27 days as CDC director.

She was confirmed by the Senate in July 2025. That confirmation itself was notable because it meant the CDC actually had a permanent, accountable leader for the first time under the new law. Senators voted. She got the job. Now she had to run the agency.

But within four weeks, she was fired. In her testimony afterward, Monarez explained why: she was asked to blindly approve changes to federal vaccine policy that she believed didn't have adequate scientific foundation. She refused. And she was removed.

This is the real story behind the leadership crisis. It's not just about the mechanics of confirmation. It's about what happens when someone tries to actually run the CDC as a science-based agency rather than a vehicle for implementing predetermined policy conclusions.

Monarez had tried to maintain the line between sound public health policy and political ideology. That made her dangerous to an administration determined to reshape the agency's relationship to vaccines, pandemic preparedness, and federal public health authority.

Her firing wasn't announced as a firing. It was framed around her "poor performance" or "philosophical differences." But staff who worked with her described a capable administrator trying to protect the agency's integrity. The real reason? She wouldn't sign off on vaccine policy changes that contradicted established science.

The week Monarez was fired, another symbolic breach occurred: a gunman attacked the CDC's main campus in Atlanta. The shooter had reportedly acted out of discontent with COVID-19 vaccines. A police officer died in the response. The timing was grimly coincidental, but it underscored the real-world stakes of the political battles being fought over the agency.

After Monarez's removal, several top CDC officials resigned. People with decades of experience in epidemiology, disease surveillance, and outbreak response decided they couldn't work in an agency being remade by political ideology rather than scientific evidence.

The Human Toll: 25% of CDC Staff Gone and Expertise Walking Out the Door

The leadership crisis is really a staffing crisis.

When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. took over as Secretary of Health and Human Services, he initiated what his supporters called an "efficiency initiative." What staff experienced was a bloodbath. Approximately 25% of the CDC's workforce was affected through layoffs. That's not just numbers on a spreadsheet. That's epidemiologists who spent their careers tracking disease patterns. That's surveillance specialists who maintain the systems that detect unusual outbreaks. That's communications experts who know how to explain complex public health information to different audiences.

Many of the people walking out the door weren't forced out. They quit. When an agency loses a fourth of its staff and the leadership is unstable, the people with the most options leave first. Why stay when you're not sure if your work will be valued, if your recommendations will be followed, or if the agency you've dedicated your career to is being systematically dismantled?

The departures created cascading problems. Measles surveillance data fell behind. Guidance for clinicians on diseases like measles became outdated. State health departments, which rely on federal CDC support for funding and technical assistance, found themselves suddenly without their usual federal partners. Local epidemiologists had fewer resources to investigate outbreaks. The entire network that makes national disease surveillance possible developed gaps.

Kennedy, the HHS secretary and vaccine skeptic who championed the staff reductions, has been explicit about wanting to reshape what the CDC does. He's questioned the safety of multiple vaccines. He's pushed alternative approaches to infectious disease that contradict mainstream public health evidence. And with 25% of the workforce gone, there's far less institutional capacity to push back against those ideas.

The CDC didn't stop functioning entirely. But it started functioning differently. It started looking less like a science-based institution and more like a branch of a particular political ideology about health.

Jay Bhattacharya: The Economist Leading Two Agencies

When Jim O'Neill departed as acting CDC director, Jay Bhattacharya was asked to take the role on top of his existing position as director of the National Institutes of Health.

Bhattacharya is a health economist by training. He has a medical degree but has never practiced medicine. His academic career has focused on health policy, economics, and the social determinants of health. He's published extensively and has held positions at Stanford and other leading institutions.

Where Bhattacharya becomes central to the current crisis is through his public positions on COVID-19. He was one of the most prominent critics of lockdown policies, school closures, and vaccine mandates. He signed the Great Barrington Declaration, a policy statement arguing for a "focused protection" approach to the pandemic rather than the broad public health measures that most epidemiologists advocated.

Bhattacharya's academic credentials are real. His research is published in peer-reviewed journals. He's not a charlatan. But his positions on pandemic response diverge significantly from what the majority of infectious disease specialists, epidemiologists, and public health experts believe the evidence supports.

Now he's running the CDC while also running the NIH.

The White House justified this arrangement by citing his "complete confidence" from President Trump, his "academic credentials," and his "proven track record of restoring Gold Standard Science-based decision-making at the NIH." That last phrase is worth unpacking. It frames his pandemic skepticism as restoring scientific integrity rather than what critics argue is ignoring scientific consensus in favor of alternative frameworks.

The practical problem with Bhattacharya running both agencies is simpler: one person can't effectively lead two massive federal science institutions simultaneously. The CDC and NIH have different missions, different stakeholder bases, different scientific cultures. Splitting attention between them means neither gets the leadership focus that both desperately need.

It also means that a person with deep skepticism toward vaccine science is overseeing vaccine policy, and someone with alternative views on pandemic response is directing the agency responsible for pandemic preparedness.

The timeline highlights the rapid escalation of events leading to Susan Monarez's firing, including policy disputes and external incidents. Estimated data.

The Federal Vacancies Reform Act: Why It Has Limits (and What Happens After March 25)

Under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA), a Senate-confirmed official can take on an additional role in an acting capacity. This is meant to be temporary, not permanent.

The law sets a 210-day limit. Once that period expires without a nominee being made, there are only certain functions the acting official can continue to perform. Tasks that are "delegable"—managing operations, issuing routine guidance, coordinating responses—can continue. But certain statutory functions tied specifically to the CDC director role cannot be performed by someone who isn't either confirmed or officially designated as acting director under FVRA procedures.

For Bhattacharya's case, that 210-day clock started after Susan Monarez's departure. That means March 25 is the deadline. After that date, Bhattacharya could be challenged legally if he attempts to perform certain statutory functions that the law reserves for the CDC director specifically.

But here's the trick: the administration can simply not nominate anyone. If there's no nominee, Bhattacharya continues in a gray legal area where he's technically not the acting director anymore, but he's still performing the functions. It's legally vulnerable but practically hard to challenge immediately.

Legal scholars who study the FVRA, like Anne Joseph O'Connell at Stanford Law School, have warned that this pattern undermines the entire system. When an administration can simply avoid the nomination process and have one confirmed official manage multiple agencies indefinitely, the whole point of requiring confirmation disappears. The check on power that the 2023 law was supposed to create evaporates.

The intention behind the FVRA was to prevent this exact scenario: having critical government functions run by people accountable to no one, serving indefinitely without confirmation, answerable to nobody but the sitting president. But when it's stretched this way, that intention collapses.

The Measles Crisis That Shouldn't Be: Surveillance Failures and Delayed Data

One of the most concrete consequences of the CDC's leadership vacuum and staffing crisis is something most Americans don't pay attention to: measles surveillance.

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease. Before vaccines, it killed hundreds of Americans annually. It causes brain inflammation, permanent hearing loss, and serious complications especially in young children and immunocompromised people. The US eliminated measles in 2000 through vaccination. It was a major public health victory.

But measles can come back. It comes back when vaccination rates drop, when surveillance falters, when people stop taking the disease seriously because they've never seen it. There have been multiple measles outbreaks in recent years driven by low vaccination rates in specific communities. Each outbreak required investigation, contact tracing, and effort to prevent spread.

The CDC is responsible for tracking measles cases nationally. It operates a surveillance system that collects data from health departments in all 50 states, identifies patterns, watches for unusual clusters, and alerts clinicians when cases emerge in their areas. This system only works if data flows regularly, if the CDC has staff to analyze it, and if guidance gets updated based on what the data shows.

With 25% of the workforce gone, that system started breaking down. Measles surveillance data fell behind schedule. Guidance for clinicians became outdated. State health departments reported unclear or incomplete information from the federal level. When clinicians don't have current CDC guidance on recognizing and managing measles, they might miss cases. Missed cases spread.

This isn't theoretical. A measles outbreak could happen tomorrow. And right now, the CDC would be trying to respond with a leadership vacuum, a decimated workforce, and acting directors juggling multiple agencies.

Ronald Nahass, president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, was explicit about the danger: "We are woefully unprepared for a bioterror attack or novel pathogen outbreak without leaders capable of directing a national response, including investigation, scaling up testing, clear public communication and coordination with health care professionals across the country."

Those aren't abstract concerns. They're specific warnings from the people who would be trying to help coordinate response if something went wrong.

State and Local Health Departments: The Collateral Damage of Federal Instability

The CDC doesn't exist in isolation. It's the federal partner for 50 state health departments, hundreds of local health departments, and thousands of clinicians in hospitals and private practice.

When the CDC loses staff and leadership, that network frays. State health departments rely on CDC funding, CDC guidance, CDC technical expertise, and CDC data systems. When the federal partner is unstable, everything downstream becomes harder.

Several things happen concretely. Funding that flows from CDC to states gets delayed or unclear. Technical assistance from CDC epidemiologists becomes harder to access because those epidemiologists either quit or are overloaded. Guidance becomes stale because there's no capacity to update it. Data systems that states rely on break or update slowly.

A measles case investigation in Ohio suddenly becomes harder because the state epidemiologist can't reach a federal contact with current knowledge. A hospital system trying to understand new guidance on disease X finds the CDC website hasn't been updated in months. A state trying to prepare for the next respiratory virus outbreak has less federal support.

Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, framed it perfectly: "You would never run a company with a series of temporary CEOs." But that's what's happening in public health. The federal health agency is being run by acting leaders on the fly, and that cascades down to state and local systems that depend on federal stability.

The public health system is supposed to be a network. When the federal hub is unstable, the whole network becomes less effective. And if something serious happens—a measles outbreak, a new respiratory virus, a foodborne illness cluster that crosses state lines—the response will be coordinated by people who are still learning the job.

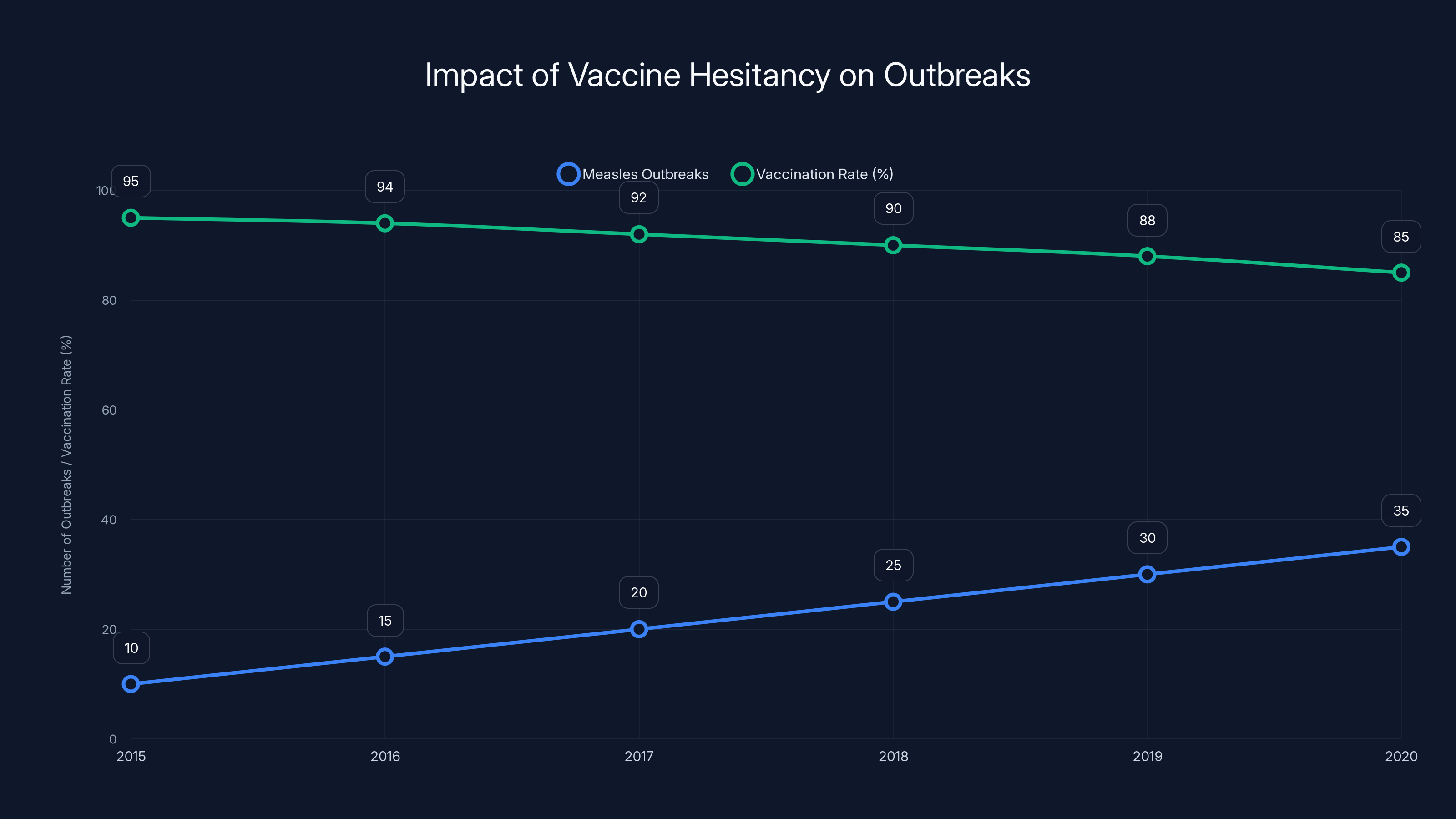

Estimated data shows a decline in vaccination rates correlating with an increase in measles outbreaks, highlighting the impact of vaccine hesitancy.

The Ideological Reshaping of Vaccine Policy

Underneath all the procedural stuff about acting directors and confirmation timelines is a more fundamental question: what is the CDC for?

The administration's answer is different from what most people would assume. The CDC should be an institution that questions vaccine safety consensus. It should explore alternative approaches to infectious disease. It should be skeptical of federal health authority and supportive of state and individual choice. That's not how most epidemiologists, infectious disease doctors, or public health experts would define the agency's mission, but it's clearly what's being attempted.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the HHS secretary, has been explicit about this. He's questioned vaccines that public health experts consider safe. He's argued that chronic disease in children is related to vaccine schedules despite studies showing no such relationship. He's positioned himself as anti-establishment in health policy.

The problem is that vaccines, as a category, are one of the most successful public health interventions in history. Smallpox was eliminated. Polio was nearly eliminated globally. Measles, mumps, and rubella were controlled in developed countries through vaccination. The evidence base supporting vaccines as safe and effective is massive, decades-long, and built on billions of doses administered worldwide.

When the leader of the federal health system questions that consensus, vaccine confidence erodes. When parents become uncertain about whether vaccines are safe, vaccination rates fall. When vaccination rates fall, diseases that were controlled come back.

That's not theoretical either. Measles outbreaks have occurred in the last few years precisely in communities where vaccination rates dropped below the threshold needed for herd immunity. Pertussis outbreaks similarly cluster in low-vaccination areas. These aren't coincidences. They're predictable consequences of vaccine hesitancy.

The CDC under leadership that questions vaccine science becomes a tool for amplifying that hesitancy, whether intentionally or not. And without a permanent director confirmed by the Senate, there's no one accountable for that shift. There's just a series of acting leaders implementing policies for an administration with a specific ideological direction.

The Governance Problem: How Permanent Leadership Actually Protects Public Health

There's a reason why public health organizations, hospitals, universities, and research institutions all require permanent leadership. It's not bureaucratic habit. It's a functional necessity.

When you have a permanent director confirmed by the Senate, that person is accountable. They testified at their confirmation hearing. Senators asked hard questions. They made commitments. If they violate those commitments or act incompetently, Congress can investigate. The public can track them. There are consequences.

When you have a series of acting directors, accountability evaporates. An acting director serves at the pleasure of the president. They have no incentive to resist pressure because they have no job security. They're just trying to get through their tenure without creating problems that get them fired.

This matters immensely for an agency like the CDC. The whole point of creating an independent science-based institution is that public health shouldn't bend to whatever political winds are currently blowing. A permanent director confirmed by the Senate, especially one with strong credentials and a reputation to protect, is more likely to resist pressure to implement policies they believe are unsound.

But a series of acting directors, especially ones selected specifically because they align with the administration's ideological commitments? They're not going to resist. They're just going to implement what they're asked to do.

Anne Joseph O'Connell, the Stanford law professor who studies the Federal Vacancies Reform Act, warned about exactly this: "At some point, having one confirmed official serving as the acting leader of multiple agencies undermines the spirit of the FVRA. We should worry about the harms to governance."

Those harms are real. When the CDC is run by acting directors implementing an ideological agenda rather than a confirmed director accountable to the Senate, the institution loses the independence that makes it trustworthy. Public trust in the CDC, already damaged by COVID-19 debates, erodes further. And that loss of trust ripples outward to influence whether people trust vaccines, follow public health guidance, or cooperate with outbreak investigations.

The Pattern of Avoiding Confirmation: Why This Matters Beyond the CDC

Bhattacharya's arrangement—running two major federal agencies on an acting basis—fits a pattern from Trump's previous term and current administration.

Marco Rubio, the Secretary of State, simultaneously serves as acting director of the US Agency for International Development and the National Archives and Records Administration. These aren't small jobs. They're critical agencies. But instead of going through separate confirmation processes, the administration uses one confirmed official to run multiple agencies informally.

This stretches the Federal Vacancies Reform Act beyond what it was designed for. The FVRA anticipated temporary situations where agencies might need a placeholder leader for a few months while a nominee went through confirmation. It didn't anticipate permanent arrangements where one person runs multiple agencies indefinitely.

But here's the political advantage for the administration: by not nominating permanent directors, it avoids confirmation hearings. No Senate Democrats get to question the nominees. No uncomfortable revelations about positions or qualifications emerge. The administration can implement its preferred policies without the scrutiny that confirmation requires.

As Bruce Mirken from Defend Public Health put it: "Trump has a history of avoiding the Senate confirmation process when it's likely to be difficult—most famously with his US Attorney appointments—so it's not a stretch to think he's doing the same at CDC, given the damage the administration's health policies have caused and the growing opposition to his assault on public health."

That's blunt language, but it describes the dynamic accurately. If you know a nominee will face tough questioning about their positions on vaccines or pandemic response, why nominate anyone? Just use the acting director apparatus and implement the same policies without the confirmation scrutiny.

This is a governance innovation of sorts, though not a healthy one. It exploits the Federal Vacancies Reform Act in ways that undermine the intent of that law and the confirmation process more broadly.

Approximately 25% of CDC staff have departed due to layoffs and resignations, impacting the agency's effectiveness. Estimated data.

The 2023 Law That Backfired: How a Check on Power Became a Tool for Avoiding Accountability

The whole current situation exists because of a law passed in 2023. Republicans, who controlled the Senate at the time, required the CDC director to be confirmed by the Senate.

Their intent, stated plainly, was to check what they saw as unchecked power at the CDC. They believed the agency had overstepped during COVID-19. They wanted to ensure that the director had to convince the Senate they were qualified and reasonable.

But laws don't always work as intended. This one backfired spectacularly.

Why? Because it created a new mechanism for avoiding accountability rather than enhancing it. When the law required confirmation, it made the position more important and more political. Now whoever runs the CDC has to answer to the Senate. But if the administration doesn't nominate anyone permanent, the acting director doesn't have to answer to anyone.

It's like building a new lock on a door and then having someone just stop using the door entirely.

The Republicans who championed the law probably didn't intend this outcome. They probably expected that future administrations would simply nominate CDC directors who passed Senate confirmation. They didn't anticipate an administration that would exploit the gaps in the Federal Vacancies Reform Act to avoid confirmation entirely.

But intentions don't matter much for governance. What matters is what actually happens. And what's actually happening is that the CDC is being run by a series of acting directors with no permanent leadership in sight, no clear timeline for nomination, and no confirmation hearing where the public could hear directly from the person running the agency.

The 2023 law was supposed to improve governance. Instead, it created a vacuum that the current administration is exploiting to implement health policies with less oversight than would occur under a confirmed director.

That's not what the law was designed for. But it's what the law has enabled.

Bioterrorism, Novel Pathogens, and the Risk of Being Unprepared

Most people aren't thinking about bioterrorism or novel pathogen outbreaks when they wake up in the morning. But public health officials are. It's their job.

And right now, those officials are terrified.

Not in a hysterical way. But in the sober, professional way that specialists get terrified when they understand a risk and see that preparations are being dismantled.

A bioterror attack using a modified pathogen would require exactly the kind of response that a well-prepared CDC provides: rapid laboratory analysis, deployment of testing capacity, investigation of cases, coordination with hospitals, clear communication to clinicians and the public about symptoms and management, connection with international health authorities if the pathogen came from abroad.

The CDC has the expertise to do this. It has the laboratories, the epidemiologists, the communication apparatus, the relationships with state and local health departments. But it also needs leadership. It needs someone who can make rapid decisions, coordinate across agencies, direct resources, and maintain focus during a crisis that might last weeks or months.

With a series of acting directors and 25% of the workforce gone, that capacity is degraded. The expertise is still there, but it's thinner. The decision-making apparatus is less clear. The coordination is harder.

A truly novel pathogen—something like SARS-Co V-2 that we had no prior immunity to—would stress even a fully-staffed CDC with permanent leadership. A CDC like the current one, with leadership instability and staffing holes, would be even more stressed.

Ronald Nahass made the point directly: "We are woefully unprepared for a bioterror attack or novel pathogen outbreak without leaders capable of directing a national response."

That's not hyperbole. That's assessment from someone who specializes in infectious diseases and coordinates responses to serious outbreaks.

The irony is that pandemic preparedness has been specifically de-emphasized under the current leadership. The administration views pandemic response during COVID-19 as an overreach. So the institutions and capabilities that would be most critical in the next pandemic are being actively de-prioritized.

If something happens, we'll learn exactly how much it mattered that the CDC was being run by acting directors during the time when it should have been preparing.

The Resignation Cascade: Losing the People Who Actually Know How to Do the Work

When Susan Monarez was fired, the immediate consequence wasn't just that the CDC lost a director. It was that several high-level CDC officials resigned.

These weren't people randomly leaving. They were experienced scientists and administrators who had worked at the CDC for years, who understood the systems, who knew how to manage an outbreak response or design a surveillance system.

Why did they resign? Because they saw what happened to Monarez. They saw that a director who tried to maintain scientific integrity got removed. They realized that the agency they had dedicated their careers to was being fundamentally reshaped in ways they couldn't accept professionally.

So they left. And when they left, they took their expertise, their relationships, their institutional memory. Other scientists and engineers saw those resignations and started looking for jobs elsewhere. Some had already left as part of the mass layoffs. Now the voluntary departures were accelerating.

This is what organizational crisis looks like in real time. It's not just about the formal structure. It's about people losing confidence in the institution, deciding they don't want to be part of it, and leaving to work somewhere else.

The CDC will hire new people. But new people don't have the relationships with state health departments that someone with 20 years at the CDC has. New people don't have the mentoring relationships, the deep knowledge of how systems work, the credibility with the scientific community.

Recovering from this kind of institutional damage takes years. And during those years, the CDC is less effective. It's running on the bench while the starters are still leaving the field.

Estimated data shows that while the majority of the medical community supports vaccine safety, a small but vocal minority remains skeptical. This reflects the challenges faced by nominees like Dave Weldon.

Public Trust and Vaccine Hesitancy: How Leadership Instability Affects Individual Decisions

There's a reason why public health communicates emphasize trust and authority. When people trust public health institutions, they follow guidance. When they don't, they don't.

Public trust in the CDC was already damaged by COVID-19. Different pieces of guidance changed as knowledge evolved—that's normal for emerging diseases. But the communication of those changes, the explanations of why guidance shifted, the clarity about uncertainty—all of that was messy.

Trump's second term has accelerated the erosion. When vaccine-skeptical leaders take over health agencies, when a director is fired for refusing to blindly approve policy changes, when the agency loses a quarter of its workforce—that sends a message to the American public.

The message isn't subtle: this isn't an institution committed to following evidence. This is an institution being reshaped for political purposes.

And when people think the CDC is politically compromised, they're less likely to trust its vaccine recommendations. They're less likely to vaccinate their children. They're less likely to follow guidance in an outbreak. They're more likely to believe alternative information sources and celebrity health advocates.

This has concrete public health consequences. Measles, pertussis, mumps—these diseases only stay controlled if vaccination rates stay above certain thresholds. When vaccination rates fall, diseases come back. That's not ideology. That's epidemiology.

So the instability at the CDC leadership level, the staffing cuts, the public firing of a director for scientific reasons—all of it contributes to vaccine hesitancy, which contributes to lower vaccination rates, which contributes to outbreaks of preventable diseases.

It's a causal chain that goes from leadership instability to public trust to individual decisions to disease patterns.

What Happens After March 25: Scenarios for the CDC's Future

The 210-day clock for Jay Bhattacharya serving as acting CDC director expires on March 25. What happens next is genuinely uncertain.

Scenario one: The administration nominates someone for permanent CDC director. That person goes through Senate confirmation hearings, faces questions about vaccine policy and public health philosophy, and either gets confirmed or rejected. This is the normal process. It would establish clear leadership and accountability.

Scenario two: The administration doesn't nominate anyone and relies on the legal ambiguity after March 25. Bhattacharya continues running the CDC despite technically exceeding his authority. This is legally vulnerable but practically hard to challenge immediately. Congress could sue, but legal proceedings take time.

Scenario three: The administration appoints someone else as acting director using the cascade method—a different Senate-confirmed official is asked to take on the acting role. This could continue indefinitely under the FVRA.

Scenario four: Congress changes the law. Democrats could push for a change that tightens when acting appointments can be used, or that requires nomination within a certain timeframe. But that would need Republican support or a veto override.

Based on current behavior, scenario two seems most likely: the administration avoids formal nomination and relies on the legal gray area created after March 25. This allows them to continue implementing their health policy agenda without the scrutiny that confirmation requires.

But March 25 is a deadline worth watching. What the administration does at that moment will tell you a lot about whether they ever intend to nominate a permanent CDC director or whether they're committed to running the agency indefinitely through acting directors.

What Public Health Experts Are Saying About the Crisis

If you want to understand how serious public health professionals think this is, listen to what they're saying publicly.

Ronald Nahass, representing infectious disease specialists: "We are woefully unprepared for a bioterror attack or novel pathogen outbreak without leaders capable of directing a national response."

Georges Benjamin, from the American Public Health Association: "You would never run a company with a series of temporary CEOs."

Bruce Mirken, from Defend Public Health: "Trump has a history of avoiding the Senate confirmation process when it's likely to be difficult."

These aren't partisan attacks. These are professional assessments of what happens when an institution this important doesn't have permanent, accountable leadership. These are specialists in public health and infectious disease saying that the current arrangement makes the nation less prepared for the next disease crisis.

They're also saying it carefully, with professional language, because they work in a system that's now controlled by the administration they're criticizing. But the underlying concern is clear and serious.

When health professionals start warning publicly about institutional failure, that's worth paying attention to. These aren't alarmists. These are people whose job is to worry about disease outbreaks and public health crises.

The Broader Question: What Is a Government Agency For?

Underlying all of this is a fundamental question that goes beyond CDC leadership or the Federal Vacancies Reform Act: what are government agencies actually for?

One answer is that they're institutions designed to serve the public interest based on expertise and evidence. The CDC exists to prevent disease and promote health. To do that well, it needs to be independent enough that it can follow evidence even when that evidence is politically inconvenient.

Another answer is that government agencies are tools of the administration in power. They should implement the policies that the president and their appointees want implemented. From this perspective, the CDC should be responsive to political direction, not resistant to it.

The 2023 law requiring Senate confirmation was based on the first idea: that an agency this powerful needs accountability and independence. Republicans believed the CDC had strayed into policymaking that went beyond evidence, and they wanted to check that through confirmation.

But the current administration is operating on the second idea: that the CDC should implement the health policies that the administration prefers, including skepticism of vaccines and departure from pandemic response orthodoxy. And it's using the gaps in the system to do that without the scrutiny that confirmation would bring.

That tension—between agencies as independent evidence-based institutions versus agencies as tools of political control—is one of the deepest governance questions in American democracy. The CDC leadership crisis is just one manifestation of it.

But it's an important manifestation, because when that tension gets resolved in favor of political control, the independence of expertise suffers. Scientists become more cautious about challenging authority. Career professionals leave. And the institution becomes less effective at its core mission.

Lessons From History: When Institutions Lose Independence

There are historical examples of what happens when powerful institutions lose their independence and become tools of political control.

The CDC itself provides one example. During the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, political leaders and religious conservatives pushed the agency to downplay transmission risks and minimize prevention messaging around sex work and drug use. Scientists at the CDC knew better. But they worked in an environment where their work was being questioned politically. Some of the most important early AIDS research came from outside the CDC, from researchers who weren't constrained by political pressure.

The tobacco industry provides another example. For decades, it pressured government agencies and scientists to downplay smoking risks. Agencies that could have acted independently didn't, in part because of political pressure. The result was delayed health warnings, continued disease, continued deaths. The independence of scientific agencies mattered.

When institutions lose their ability to follow evidence against political pressure, evidence-based policy fails. It's that simple.

What's happening at the CDC now is part of that pattern. It's the politicization of a scientific institution. Whether that results in harmful policy outcomes—how many measles cases occur, what happens in the next pandemic—remains to be seen. But the trajectory is clear.

The Road Ahead: What Needs to Happen

The CDC leadership crisis won't resolve itself. Something will happen: either a permanent director will be nominated and confirmed, or the current acting arrangement will continue indefinitely, or Congress will change the law.

What should happen? That depends on what you believe the CDC should be.

If you believe the CDC should be a science-based institution insulated from political pressure, then it needs a permanent director confirmed by the Senate who has the credibility, expertise, and independence to resist pressure to implement policies that contradict evidence. It needs to rebuild its workforce. It needs to restore the relationships with state health departments and clinicians that make the surveillance system work.

If you believe the CDC should be responsive to the administration's preferred health policies, then the current arrangement—acting directors implementing ideology with less scrutiny—makes sense. But you should be honest about what you're choosing: you're choosing a CDC that's less independent, that may be less effective at detecting and responding to outbreaks, and that may lose credibility with the public.

Those are the actual choices. There's no neutral option where the CDC is still an independent, effective scientific institution while also being fully responsive to whatever the current administration wants.

What needs to happen practically:

-

Clarity on timeline: The administration should either nominate a CDC director or explain why it won't. The current indefinite uncertainty is itself damaging to the institution.

-

Rebuilding capacity: Whether under current leadership or new leadership, the CDC needs to rehire and retain experienced epidemiologists, surveillance specialists, and scientists. A science-based institution needs scientists.

-

Restoring relationships: State and local health departments need to know they have a reliable federal partner. That requires clear communication and follow-through from CDC leadership.

-

Possible legal changes: Congress could revise the Federal Vacancies Reform Act to prevent the indefinite rotation of acting leaders. It could require nomination within a specific timeframe. It could change the 210-day limit.

None of this will happen because of this article or public concern. It will happen if and when the political calculation changes. If enough outbreaks occur that the instability at the CDC becomes impossible to ignore. If states start suing because they're not getting expected federal support. If vaccine-preventable disease becomes visible enough that the public starts asking questions.

Until then, the CDC will operate with acting directors, depleted staff, and leadership that views science as subordinate to ideology.

Conclusion: An Institution Under Stress

The CDC isn't in free fall. It's not completely broken. Scientists still work there. Epidemiologists still investigate outbreaks. The laboratories still run tests. Disease surveillance continues, albeit with gaps.

But the institution is under stress. Leadership is unstable. Workforce is depleted. Independence is compromised. Public trust is eroding.

What comes next depends on whether the current arrangement is the plan or just temporary incompetence.

If it's the plan, then we're watching the deliberate transformation of the CDC from a science-based institution into a vehicle for implementing a particular health ideology. That transformation will take time. The resistance from career scientists, from state health departments, from clinicians will slow it down. But if the administration is committed, it will happen.

If it's temporary, then at some point a permanent director will be nominated. The CDC will stabilize. The workforce will be rebuilt. Public trust might recover. The institution will return to its previous mode of operation, albeit with scars.

We won't know which scenario is actually unfolding for a while. But March 25 is a deadline. What happens when Jay Bhattacharya's 210 days as acting director expire will tell us a lot.

For now, the CDC is running on momentum and the professionalism of career staff who are trying to do their jobs despite the instability around them. That momentum will carry the agency through a while longer. But momentum isn't permanence. Eventually, institutions need real leadership.

Until the CDC gets it, the nation is less prepared than it should be for the next disease outbreak, the next public health crisis, or the next moment when expertise and clear communication matter more than ideology.

That's not where an institution like the CDC should be. And the fact that it is tells you something about what happens when governance structures break down, when political ideology collides with scientific evidence, and when institutions lose the independence they need to serve their actual purpose.

Watch what happens after March 25. It will tell you whether this is temporary chaos or the new normal at the agency responsible for protecting the nation's health.

FAQ

What is the CDC leadership crisis?

The CDC is currently operating without a permanent Senate-confirmed director, instead cycling through acting leaders. The crisis stems from a 2023 law requiring Senate confirmation, the firing of the one confirmed director who served for just four weeks, and the administration's apparent unwillingness to nominate a permanent replacement. This has resulted in unstable leadership, massive staff departures, and reduced institutional capacity during a period when public health expertise is critical.

Why does the CDC need Senate confirmation for its director?

A 2023 law championed by Republican Senator Ted Cruz requires the CDC director to be confirmed by the Senate, similar to other high-ranking federal positions. The intent was to add accountability and oversight to an agency that Republicans believed had overstepped during COVID-19. However, the current administration is exploiting gaps in the Federal Vacancies Reform Act to avoid the confirmation process entirely by using acting directors indefinitely.

What happened to Susan Monarez, the previous CDC director?

Susan Monarez was confirmed as CDC director in July 2025 but was fired after just four weeks in office. In her testimony, she explained that she was removed for refusing to blindly approve changes to federal vaccine policy that she believed lacked adequate scientific foundation. Her firing was followed by several top CDC officials resigning, demonstrating the impact of losing a director who tried to maintain scientific integrity.

How does the Federal Vacancies Reform Act affect the CDC situation?

The FVRA allows a Senate-confirmed official to temporarily serve as acting leader of a different agency. There's a 210-day limit without a nominee, after which certain statutory functions can only be performed by an official who is either confirmed or properly designated as acting director. Currently, Jay Bhattacharya serves as both acting CDC director and NIH director, a situation that pushes the FVRA's intended use to its limits and beyond.

What are the practical consequences of the CDC leadership crisis?

With 25% of the CDC's workforce gone through layoffs and resignations, the agency faces serious operational challenges: measles surveillance data falls behind schedule, guidance for clinicians becomes outdated, state health departments lose federal support, and disease investigation capacity is degraded. Most concerning, the nation is less prepared for bioterror attacks or novel pathogen outbreaks at a time when the agency should be focused on pandemic preparedness.

Why is vaccine policy at the center of the CDC leadership crisis?

The Trump administration includes Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a well-known vaccine skeptic, as HHS secretary overseeing the CDC. The administration appears committed to reshaping the CDC's approach to vaccines and pandemic response based on ideology rather than evidence. This ideological conflict with the scientific consensus on vaccine safety is why Monarez was fired for refusing to approve vaccine policy changes, and why the administration may be avoiding a confirmation process that would scrutinize these policy shifts publicly.

What happens after March 25, 2025?

March 25 is when Jay Bhattacharya's 210-day period as acting CDC director expires. After that date, the administration can either nominate someone for permanent director, request Congressional action, or continue operating in a legal gray area where Bhattacharya technically exceeds his authority but continues day-to-day functions. What happens at this deadline will signal whether the administration intends to eventually nominate a permanent director or maintain indefinite acting leadership.

How does CDC leadership instability affect state and local health departments?

State and local health departments depend on the CDC for funding, technical expertise, data systems, and guidance. When the CDC is unstable, these relationships fray. Clear federal guidance becomes delayed or unclear, technical assistance becomes harder to access, and funding flows become uncertain. This cascades down to local health officials trying to prepare for outbreaks or manage disease surveillance without reliable federal partners.

What role did the 2023 confirmation requirement law play in creating this crisis?

The 2023 law was designed to check CDC power by requiring Senate confirmation. However, it inadvertently created a tool for avoiding accountability: without nominating anyone, the administration can avoid confirmation hearings while using acting directors to implement its preferred policies. This is the opposite of the law's intent, which was to increase oversight, not enable its circumvention.

What would restore the CDC to effective operation?

Restoring the CDC would require: nominating a permanent director with scientific credentials who can be confirmed by the Senate; rebuilding the workforce by rehiring epidemiologists and disease specialists; reestablishing credibility with state health departments and clinicians; and explicitly re-committing to evidence-based decision-making over ideological considerations. This would take years even in the best case scenario, given the damage already done to institutional trust and capacity.

Key Takeaways

- The CDC is operating without permanent Senate-confirmed leadership, cycling through acting directors to implement ideology-driven policies

- A 2023 law requiring Senate confirmation backfired by enabling the administration to avoid accountability through acting director appointments

- Approximately 25% of CDC staff have departed through layoffs and resignations, degrading the agency's disease surveillance and response capacity

- Critical functions like measles surveillance are falling behind schedule due to staffing losses and leadership instability

- The Federal Vacancies Reform Act's 210-day limit expires March 25, creating a deadline to watch for whether the administration will finally nominate a permanent director

Related Articles

- FDA Vaccine Official Overruled Scientists on Moderna Flu Shot [2025]

- HHS AI Tool for Vaccine Injury Claims: What Experts Warn [2025]

- Syphilis Origin Story: 5,500-Year-Old Discovery Rewrites History [2025]

- FDA Reverses Moderna mRNA Flu Vaccine Rejection: Inside the Political Turmoil [2025]

- DHS Subpoenas for Anti-ICE Accounts: Impact on Digital Privacy [2025]

- ICE Office Expansion Across America: What You Need to Know [2025]

![CDC Leadership Crisis: The Ongoing Instability Threatening Public Health [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cdc-leadership-crisis-the-ongoing-instability-threatening-pu/image-1-1771618088032.jpg)