Why the US Faces Surging Measles Cases in 2025: A Deep Dive Into America's Vaccination Crisis

Something's broken in America's public health infrastructure, and the numbers are getting harder to ignore.

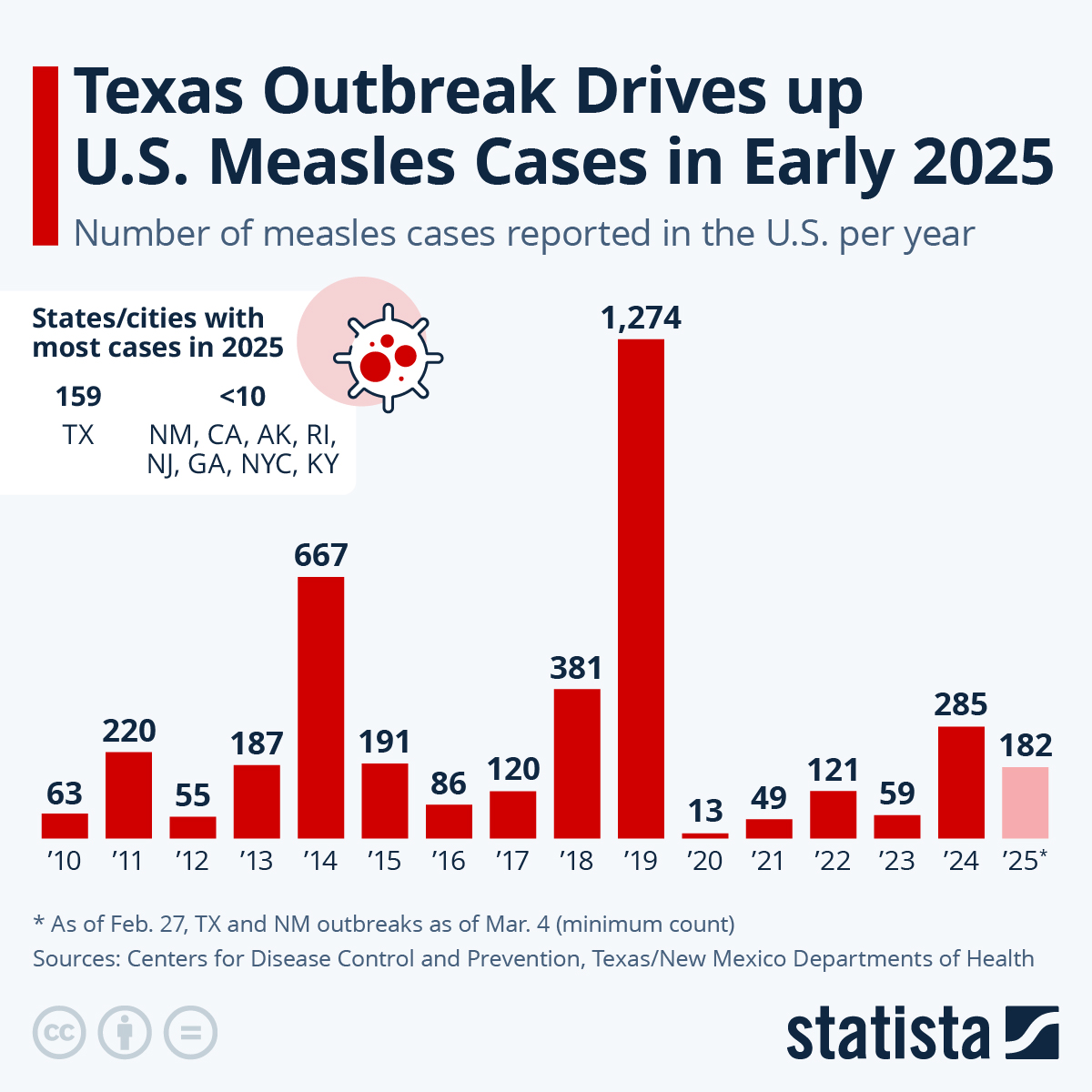

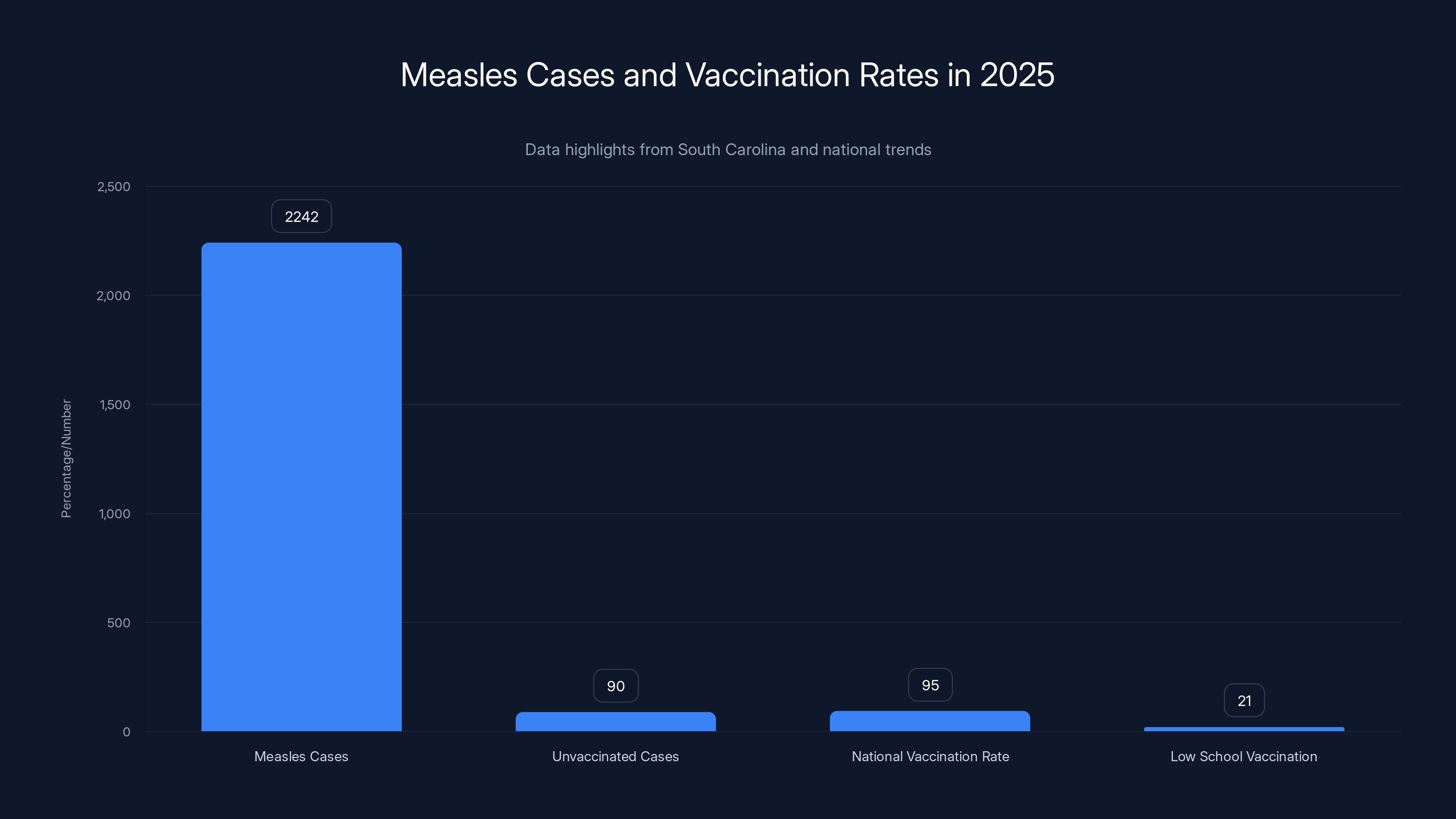

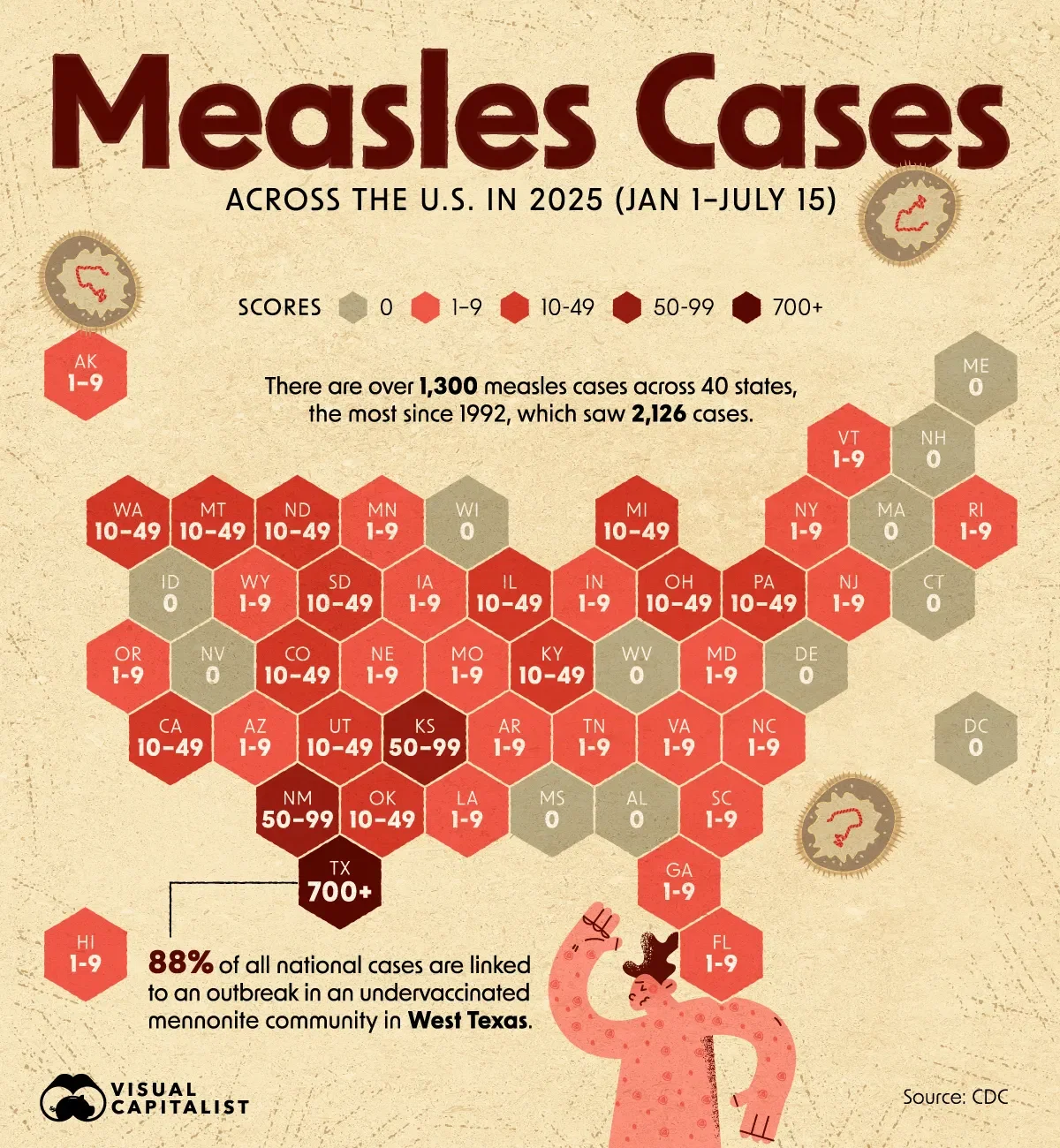

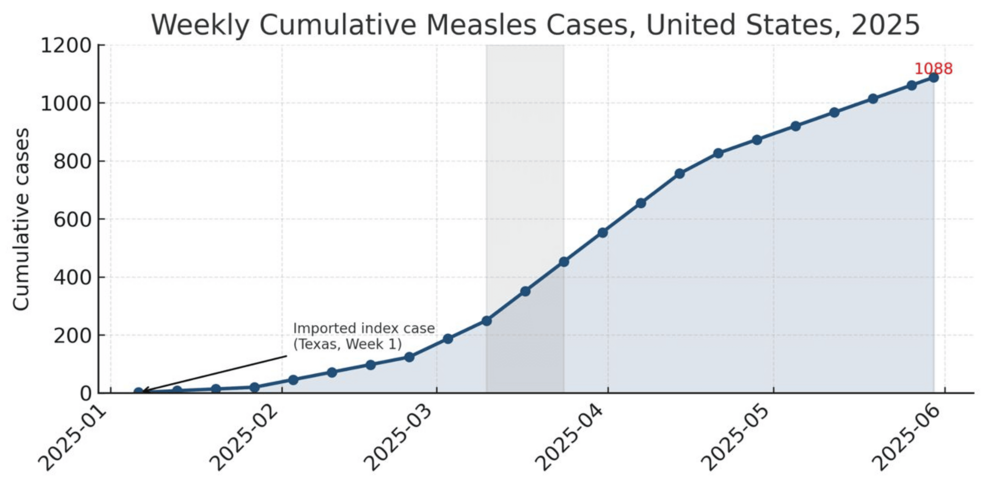

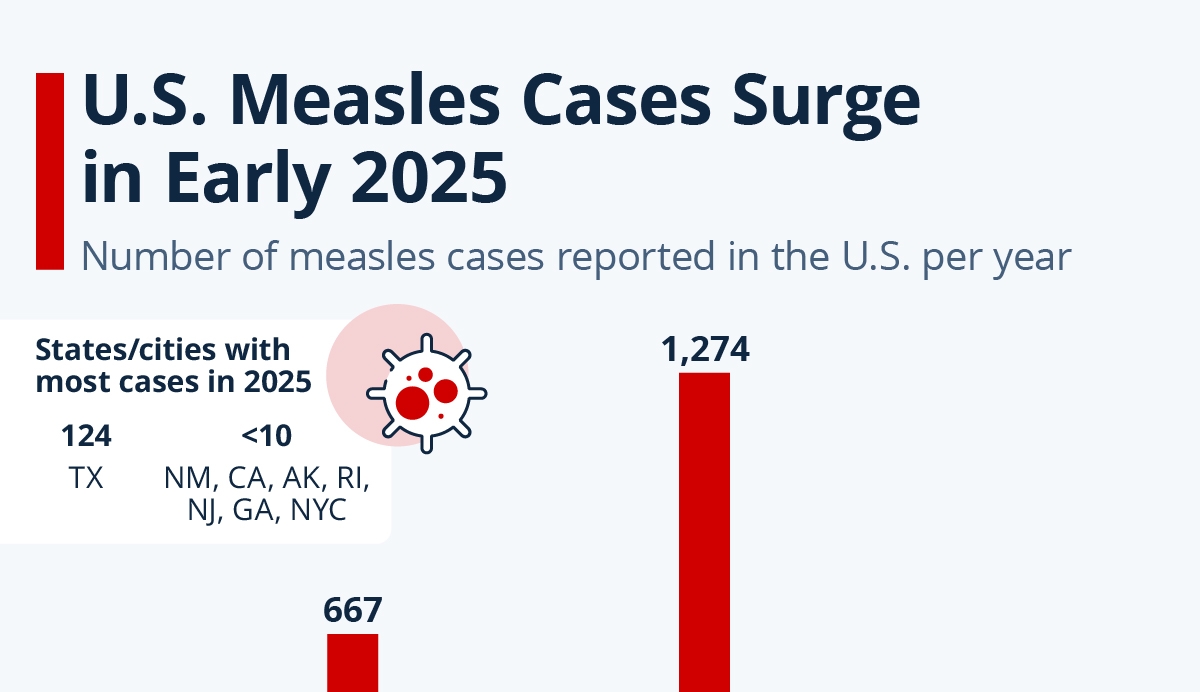

In 2025, measles case counts reached their highest level in more than 30 years—2,242 confirmed infections swept across the country. That's not a statistical blip. That's a warning sign most people aren't paying attention to. And if you think it can't get worse, the situation in South Carolina proves you'd be wrong.

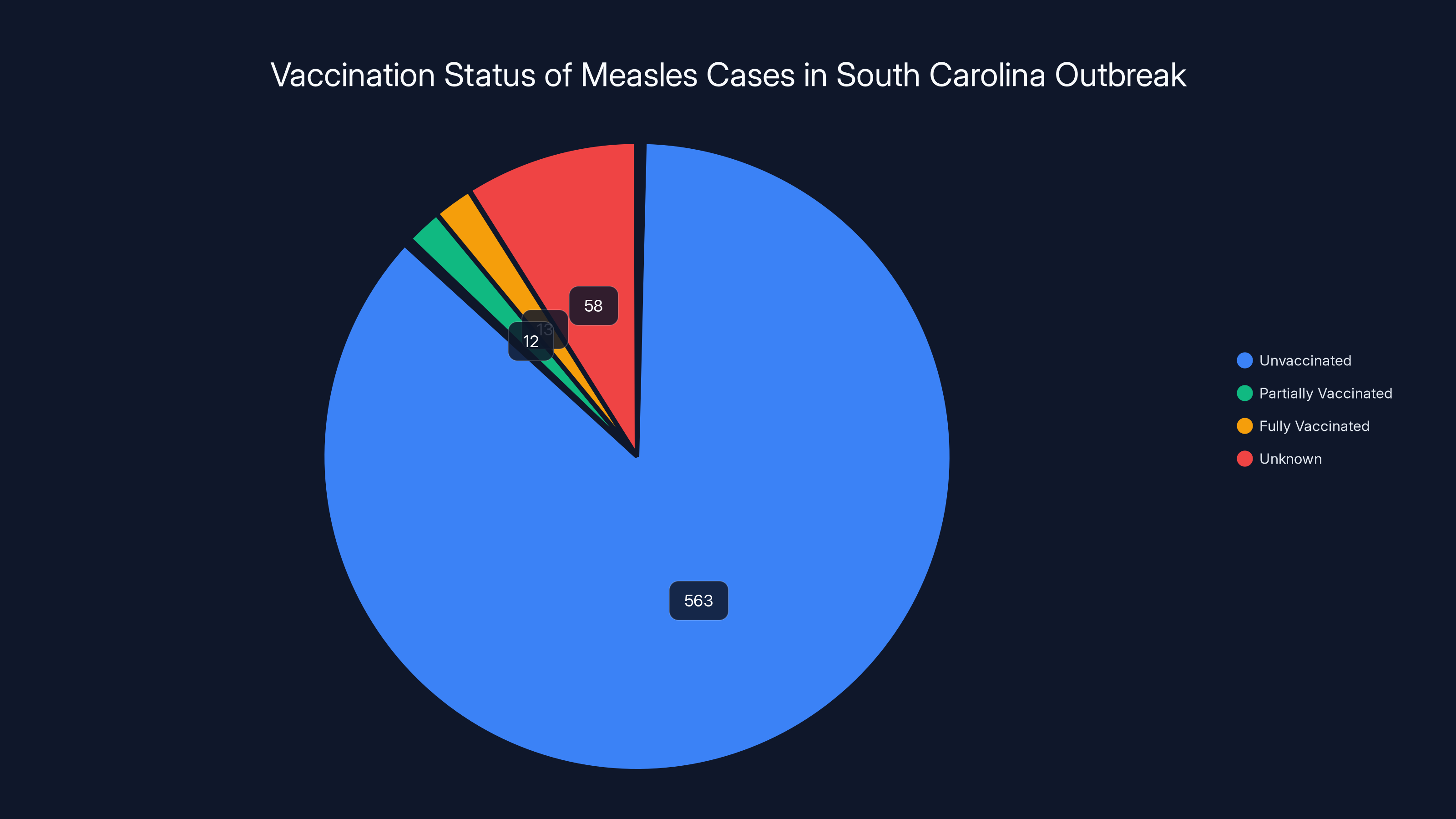

Since October, a single outbreak has infected over 646 people, with another 538 potentially exposed. Health officials expect those numbers to keep climbing. Daily case reports are hitting double digits. Hospitals are preparing for surges. And here's the part that should genuinely concern you: 563 of those 646 confirmed cases involved completely unvaccinated individuals, as reported by the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy.

The measles outbreak isn't happening in a vacuum. It's the symptom of a much bigger disease ravaging American public health. Vaccination rates have been steadily declining across states. Political hostility toward vaccines is intensifying. School exemptions are being granted more liberally. And the conditions are now perfect for what could be a sustained measles crisis throughout 2025 and beyond.

I've spent weeks digging into the data, talking to infectious disease specialists, and reviewing what's actually driving this. The story isn't just about South Carolina or West Texas. It's about how America dismantled disease prevention while nobody was watching, and what's about to happen as a result.

TL; DR

- Measles cases hit 2,242 in 2025, the highest in 30+ years, with a South Carolina outbreak showing 646+ cases and climbing

- 90% of South Carolina cases are unvaccinated, despite vaccination being highly effective and free or low-cost

- National MMR vaccination rates have fallen below 95%, the threshold needed to stop community transmission

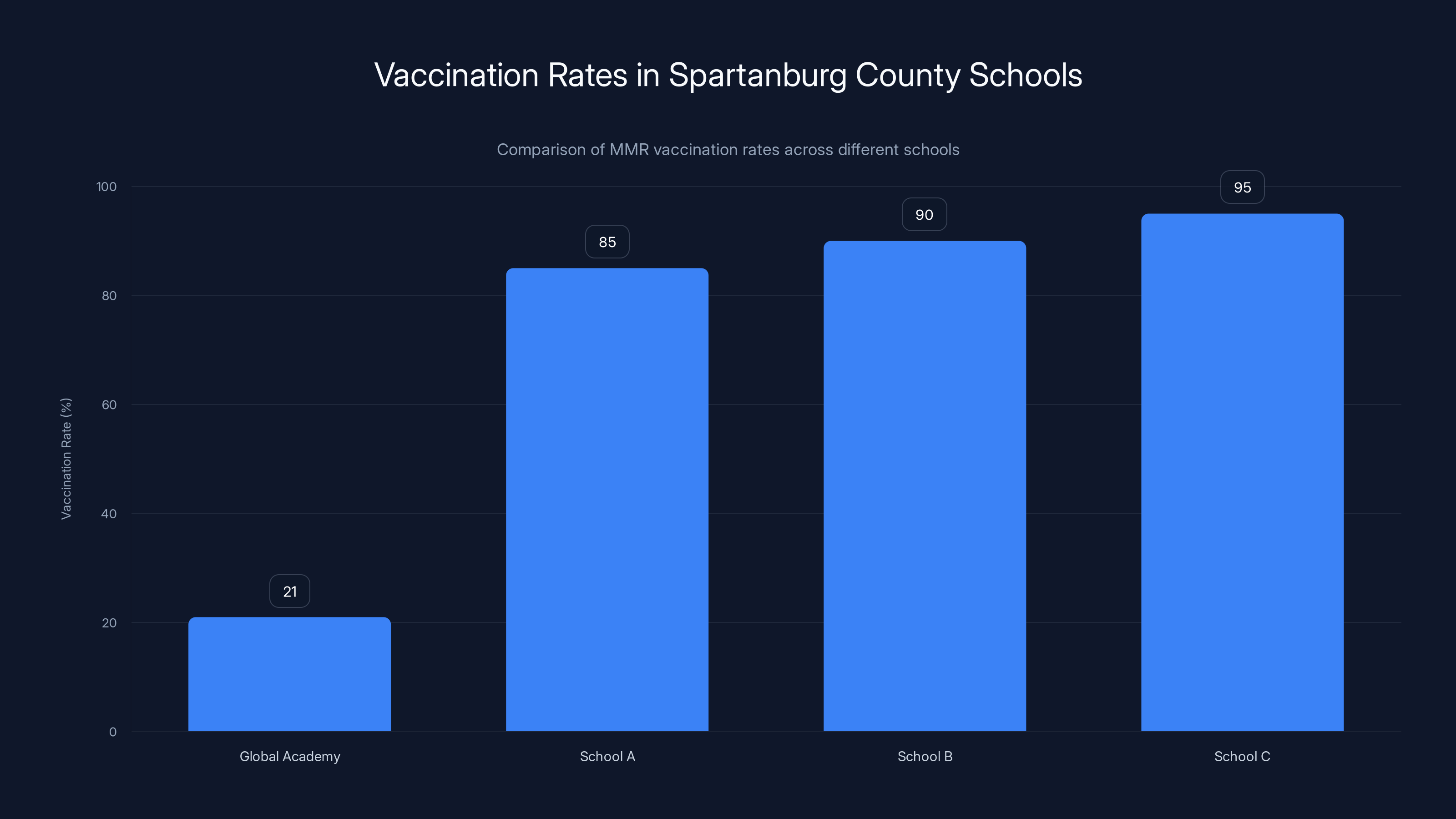

- School exemptions are surging, with some schools showing vaccination rates as low as 21% among students

- Political opposition to vaccines is accelerating the crisis, with government hostility making public health communication harder

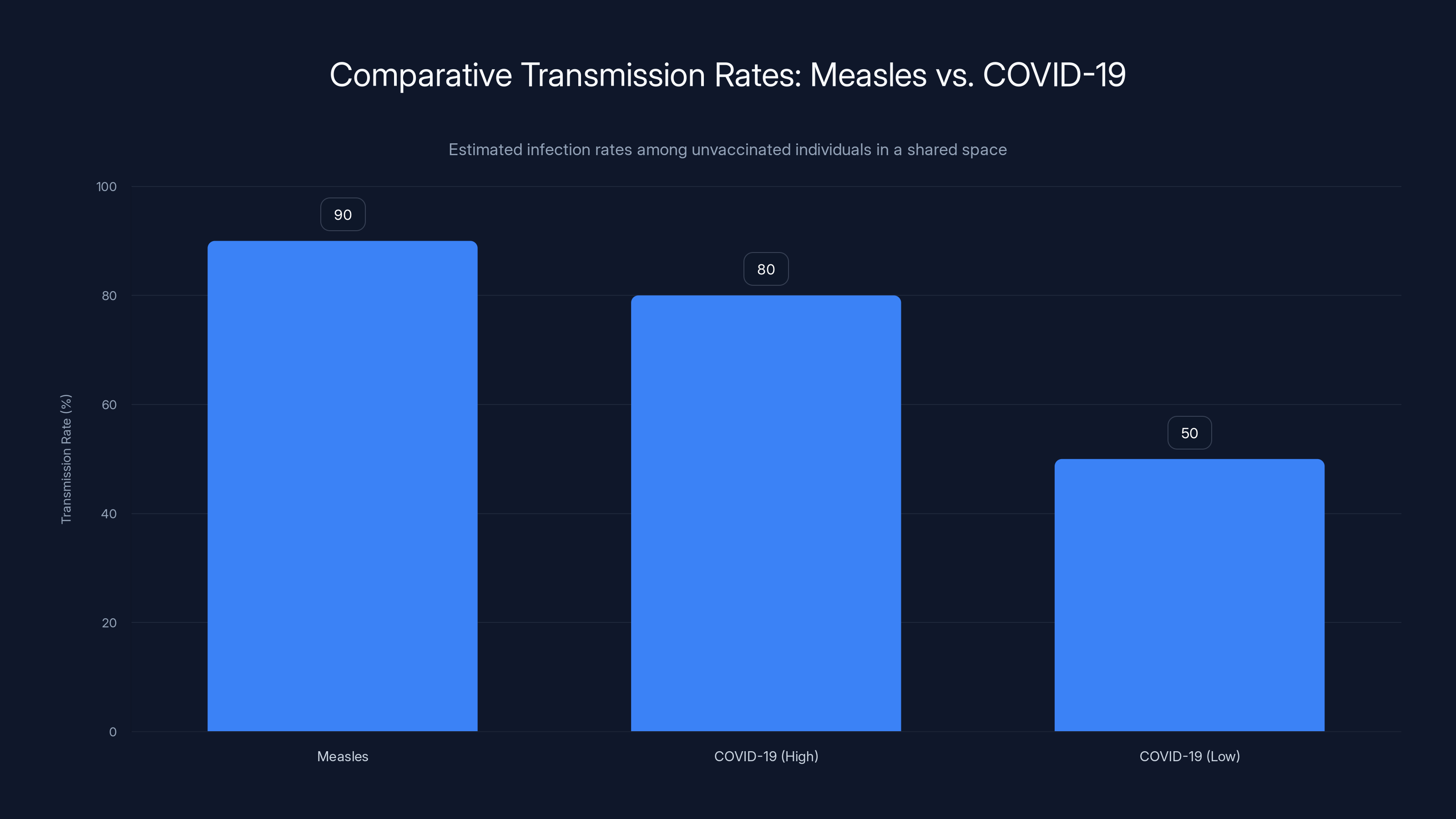

Measles is significantly more transmissible than COVID-19, with a 90% infection rate among unvaccinated individuals compared to 50-80% for COVID-19, depending on the variant.

The South Carolina Outbreak: Numbers That Don't Lie

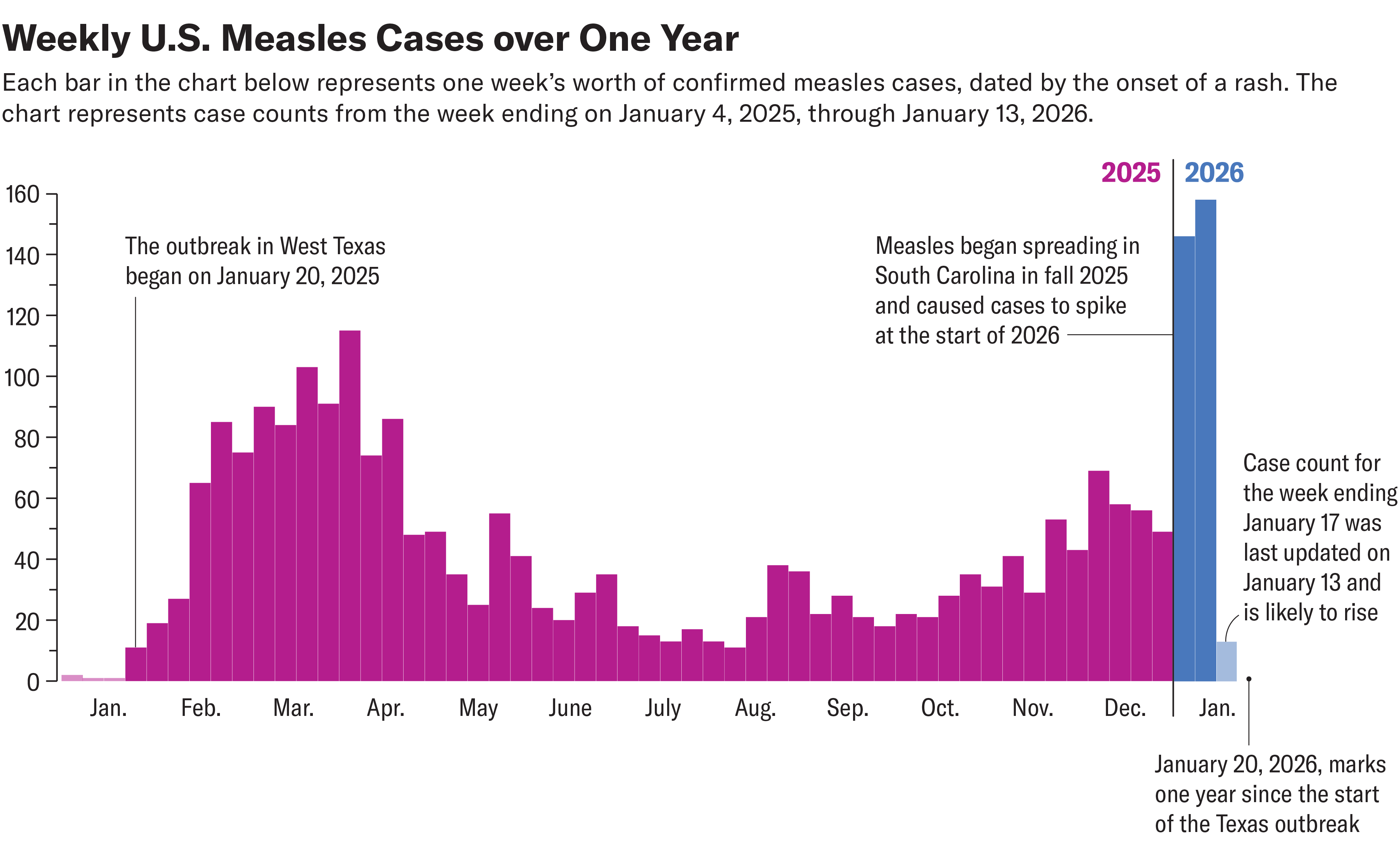

Let's start with what we know about the current situation. On October 2 of the previous year, South Carolina's health department identified an initial cluster of eight measles cases. That qualified as an outbreak—three or more linked cases. Most people barely noticed.

By the end of that year, the number had exploded to 176 cases. Still, the national news cycle barely touched it. Then January hit, and the situation became impossible to ignore. As of January 20, the count stood at 646 confirmed cases, with the outbreak centered in the northwestern "upstate" region of South Carolina, as detailed by CNN.

Here's what makes this genuinely alarming: the outbreak isn't slowing down. State epidemiologist Linda Bell reported during a January 21 briefing that new cases were being identified in double digits every single day. Think about that. Not per week. Per day. She went further, warning that the state could be dealing with this outbreak for "certainly weeks more, and potentially months more, if we don't see a change in protective behaviors."

In addition to the 646 confirmed cases, another 538 people had been potentially exposed to measles and were instructed to quarantine at home while monitoring for symptoms. That's over 1,000 people directly impacted by this single outbreak, according to CDC data.

The vaccination data from this outbreak tells the real story. Among the 646 confirmed cases: 563 were completely unvaccinated, 12 had received just one of two needed doses, 13 were fully vaccinated (likely with compromised immune systems), and 58 had unknown vaccination status. That's roughly 87% completely unvaccinated. The vaccine works. The problem is people aren't getting it, as highlighted by The Washington Post.

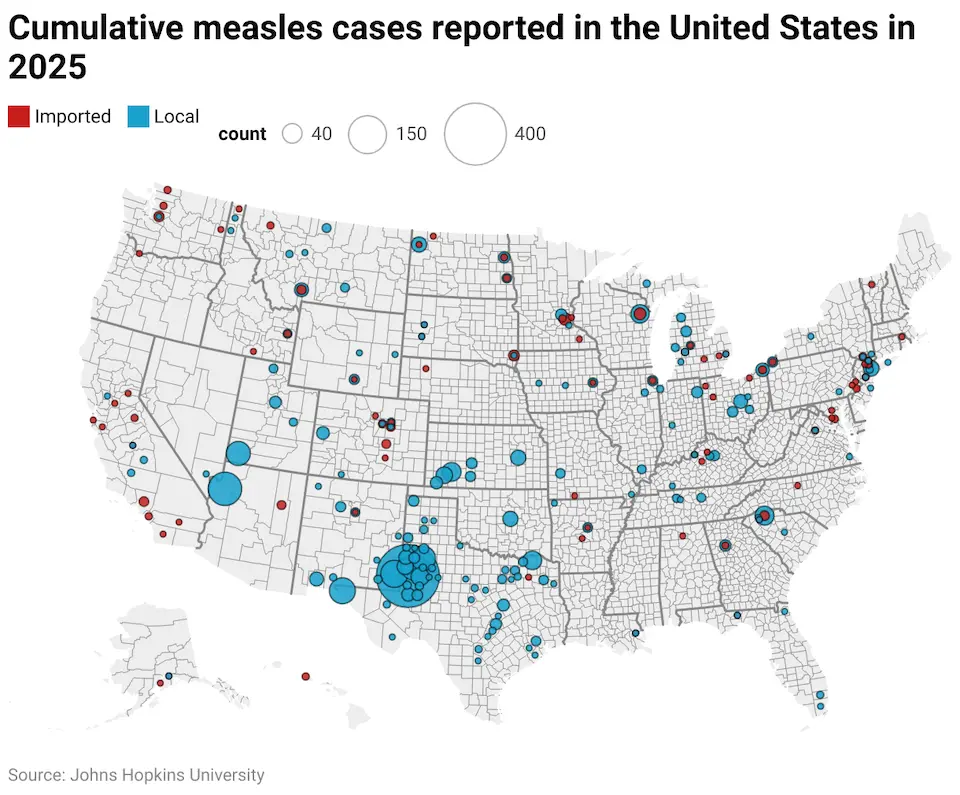

How This Compares to the West Texas Outbreak

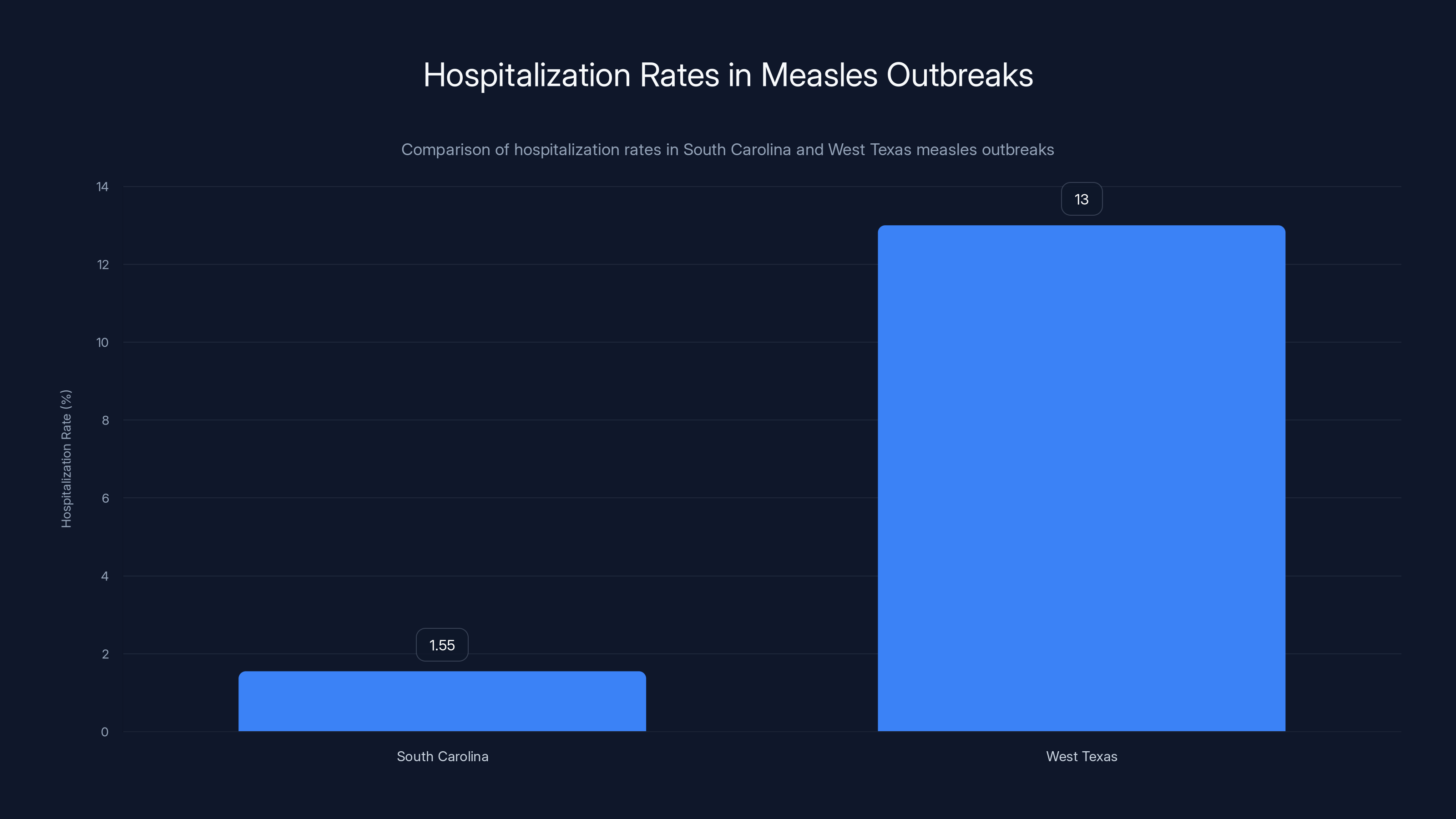

To understand how bad South Carolina has become, you need context from the West Texas outbreak that dominated 2024. That outbreak began in January and resulted in 762 confirmed cases with 99 hospitalizations. Two children died—both unvaccinated.

The West Texas outbreak took seven months to declare officially over in August. South Carolina started in October and is already outpacing it in raw numbers after just a few months. If the current trajectory continues, South Carolina will likely see more total cases than West Texas, and the duration could extend even longer.

Emergency medicine physician Johnathon Elkes, who works at Prisma Health in Greenville, South Carolina, captured the sentiment perfectly during a January 16 call with reporters: "We feel like we're really kind of staring over the edge, knowing that this is about to get a lot worse."

That's not hyperbole from someone seeking media attention. That's a frontline healthcare provider expressing genuine alarm about what's coming.

In 2025, measles cases reached 2,242, with 90% of cases in South Carolina being unvaccinated. National MMR vaccination rates fell below 95%, with some schools reporting rates as low as 21%.

Understanding Measles: Why This Virus Still Matters

Measles might sound like a historical disease—something from your grandparents' era. But the virus hasn't changed. Your immune system's vulnerability to it hasn't changed. And the consequences of infection haven't become less serious. What changed is our collective memory of why we should fear it.

The virus spreads through respiratory droplets and is remarkably efficient at transmission. If one infected person enters a room, they'll typically infect 90% of unvaccinated people in that space. For comparison, COVID-19 infects about 50-80% of exposed unvaccinated people, depending on the variant, as noted by Nebraska Medicine. Measles is more transmissible.

Initial symptoms show up 10-14 days after exposure. You get a high fever, usually spiking above 103 degrees Fahrenheit. A harsh, hacking cough develops. Your nose runs. You feel miserable. Most people think they have a bad cold or flu. Then, about three to four days into the fever, the characteristic rash appears. It starts on the face and hairline, then spreads downward across the body. The rash is distinctive—blotchy, red spots that sometimes merge together.

Here's where it gets dangerous. Measles damages more than just the surface of your respiratory system. The virus attacks cells in your lungs, potentially causing pneumonia. It severely weakens your immune system, leaving you vulnerable to secondary infections for weeks or even months after the initial infection clears. That post-measles immune suppression is particularly brutal for young children.

Pneumonia is the leading cause of death related to measles in children. Adult complications include encephalitis (brain inflammation), which can cause permanent neurological damage. Pregnant women who catch measles have higher miscarriage rates. Immunocompromised individuals—those with HIV, cancer patients on chemotherapy, transplant recipients on immunosuppressants—can develop severe, prolonged infections.

But here's the thing most people don't realize: even if you survive measles without these serious complications, the virus can have lasting effects. Your immune system takes a significant hit. For months afterward, you're more susceptible to other infections. Kids who had measles show measurably increased rates of ear infections, respiratory infections, and gastrointestinal infections in the following months.

So far in the South Carolina outbreak, 10 people have required hospitalization. That includes both adults and children. Two cases appeared on college campuses—Clemson University and Anderson University. More cases keep appearing at new public exposure locations every week, as reported by CIDRAP.

Why Vaccination Rates Are Plummeting: The Perfect Storm

The MMR vaccine is one of the most effective vaccines ever created. Two doses provide 97% protection against measles infection. Even one dose gives you 93% protection. The vaccine has been used for decades with a safety profile that's been thoroughly documented and verified. Yet vaccination rates are declining across America.

According to data from state health departments, many states have now fallen below the 95% vaccination rate needed to provide community protection. Let's be clear about what that 95% threshold means. When 95% of a community is vaccinated, the virus can't spread efficiently enough to sustain transmission. The outbreak ends because the pathogen runs out of available hosts. Below 95%, measles can circulate indefinitely through the unvaccinated population.

In Spartanburg County, South Carolina—the epicenter of the current outbreak—90% of school-age children were supposedly up-to-date on vaccinations. But that aggregate number hides a dangerous truth. Vaccination rates vary wildly between school districts. Some schools have excellent coverage. Others are disaster zones.

Global Academy of South Carolina is the prime example. As of the end of December, just 21% of students there were fully vaccinated with both MMR doses. That's not a school. That's a matchbox waiting for a spark. More than a dozen students at that school were in quarantine by January 20, as noted by ABC News.

How did a school end up with 79% of students unvaccinated? Parents seeking exemptions. That trend is spreading across the country, not isolated to South Carolina. States set their own vaccine requirements for school entry, and parents are increasingly filing for exemptions. Some states allow philosophical exemptions—meaning you can opt out of vaccines just because you want to. Others allow religious exemptions. The specifics vary, but the trend is consistent: exemption requests are rising.

The Vaccination Landscape: Where the System is Failing

You'd think the solution would be simple. The vaccine is free or low-cost. It's effective. The disease is serious. Yet something systemic is preventing vaccination rates from holding steady.

Part of the problem is information chaos. Misinformation about vaccines spreads faster and further than accurate information. A parent hears from a friend that vaccines cause autism (they don't—this claim has been thoroughly debunked and the original study retracted). They read social media posts claiming vaccines contain microchips or tracking devices (they don't). They encounter videos claiming the MMR vaccine causes autoimmune disease (the evidence doesn't support this). Each piece of misinformation chips away at confidence.

Another factor is complacency. Measles hasn't been a major threat in America for years. The vaccine worked so well that an entire generation grew up without seeing a case. When a disease seems absent, the urgency to vaccinate diminishes. People think, "Why vaccinate against something that never happens here?" The vaccine's success became the argument against vaccination.

Then there's the political dimension. What was once a straightforward public health issue has become politically polarized. Vaccine hesitancy has become tied to broader identity and political beliefs. A government that's hostile to vaccine requirements sends a message to the population that vaccines might be optional or questionable, even when the evidence overwhelmingly supports vaccination.

Susan Kline, an infectious disease physician and professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, expressed serious concern about the trajectory: "I'm concerned. Based on the size of the current outbreak going on in South Carolina, I don't think it bodes well for the current year," as cited by The Washington Post.

She's not wrong. The conditions are aligned for this to be a genuinely bad year for measles.

Global Academy has a critically low MMR vaccination rate at 21%, compared to other schools in Spartanburg County, which maintain rates closer to the 95% community protection threshold.

The MMR Vaccine: How It Works and Why It's Essential

The MMR vaccine is a three-in-one shot that protects against measles, mumps, and rubella. It's a live attenuated vaccine, meaning it contains a weakened version of the virus that can't cause serious disease but triggers your immune system to produce antibodies.

The standard schedule requires two doses. The first dose is typically given at 12-15 months of age. The second dose comes at 4-6 years old. This two-dose approach provides the 97% protection rate we discussed.

But here's an important detail: the vaccine's effectiveness depends on adequate immune system function. People with significantly compromised immune systems—those with HIV and low CD4 counts, organ transplant recipients, patients on immunosuppressive medications for autoimmune conditions—might not develop adequate immunity even after vaccination. For them, maintaining community immunity (the 95% vaccination rate) becomes critical. They depend on everyone around them being vaccinated to stay protected.

That's why those 13 people among the South Carolina cases who were "vaccinated" matter. Most of them likely had underlying immunocompromise. The vaccine didn't fail them. Their immune systems couldn't mount an adequate response to the vaccine's protective signal. But they're still vulnerable to measles.

When vaccination rates fall below 95%, this vulnerable population suddenly faces real risk. They're surrounded by circulating virus with no protective immunity of their own. That's not abstract public health theory. That's the difference between a person with cancer who gets to finish chemotherapy versus someone whose treatments get interrupted by life-threatening measles infection.

Hospitalizations and Complications: What Measles Actually Does

We've mentioned that 10 people in South Carolina required hospitalization. That number might sound small compared to 646 cases, but it tells an important story about measles severity.

Unlike some viral infections where hospitalizations cluster in specific high-risk groups, measles hospitalization affects people across demographics. It hits young children hard. A one-year-old with measles pneumonia might need oxygen support and intensive care. It affects adults too. A 35-year-old previously healthy parent can develop severe pneumonia or encephalitis.

Pneumonia remains the most common serious complication. The measles virus doesn't just infect the upper respiratory tract. It invades the lungs, causing inflammation and fluid accumulation. If severe enough, the body can't extract enough oxygen from the air you breathe. That's when you need hospitalization—oxygen supplementation, monitoring, supportive care while your immune system fights the infection.

Encephalitis—inflammation of the brain—occurs in roughly 1 in 1,000 measles cases. The infection causes your brain to swell. This can result in seizures, confusion, loss of consciousness, and permanent neurological damage. Survivors of measles encephalitis sometimes experience lasting cognitive effects, behavioral changes, or physical disabilities.

There's also the post-measles immune suppression factor. For weeks to months after the acute infection resolves, patients remain unusually susceptible to secondary infections. That means a person who recovers from measles pneumonia might develop a bacterial superinfection. Or a secondary respiratory infection. Or otitis media, a severe ear infection. The immune system's weakening isn't abstract—it translates into real complications.

In the West Texas outbreak, there were 99 hospitalizations among 762 cases. That's about 13% hospitalization rate. If South Carolina follows a similar pattern with its current trajectory, we're looking at potentially 80+ hospitalizations just from that single outbreak, as estimated by CBS News.

The Cost of Measles: Economic and Social Impact

Measles costs extend far beyond the immediate medical expenses. When an outbreak happens, healthcare systems get strained. Emergency departments see increased volume. Hospitals might need to isolate measles patients in negative-pressure rooms to prevent airborne transmission to other patients. That takes resources.

Schools face disruptions. During the South Carolina outbreak, multiple schools have had students or staff in quarantine. Some schools might need to close temporarily if enough people are infected or exposed. That creates childcare challenges for working parents and education gaps for students.

Public health departments dedicate enormous resources to outbreak response. They conduct contact tracing, identifying everyone who was exposed to confirmed cases. They work with schools and employers to notify potentially exposed individuals. They provide quarantine guidance and support. They coordinate vaccination campaigns to boost community immunity. All of this takes money, staff time, and infrastructure that could be used for other public health initiatives.

From a purely economic standpoint, the West Texas outbreak likely cost the healthcare system millions of dollars in direct care and public health response. And that doesn't account for lost productivity from sick workers and school closures, or the invisible costs of complications like permanent neurological damage.

But the real cost is harder to quantify. It's the two children who died in West Texas. It's the permanent brain damage someone might suffer from encephalitis. It's the parent who spent weeks struggling to breathe with measles pneumonia. These are preventable tragedies that happen because vaccination rates fell.

The hospitalization rate for measles in South Carolina is significantly lower at 1.55% compared to 13% in West Texas, highlighting regional differences in outbreak severity or healthcare response.

Vaccination Uptake During the Outbreak: Why the Response Slowed

Interestingly, South Carolina did see increased vaccination rates when the outbreak first became apparent. Bell noted there was "encouraging uptake" of the MMR vaccine in the first month or so after the outbreak became visible. People were scared. The disease felt real instead of theoretical. They got vaccinated.

But here's the pattern we keep seeing: initial surge in vaccination during outbreaks, then the response slows. After the first few weeks, people stop coming in. The fear fades. Life returns to normal. Yet the outbreak continues because the vaccination campaign didn't reach the threshold needed to stop transmission.

That's a psychological and behavioral challenge in public health. The crisis has to feel immediate and personal. Once it feels managed—once case counts aren't climbing exponentially—people relax. But measles doesn't work on a psychological timeline. It continues spreading through unvaccinated populations regardless of how scared people are.

To actually stop this outbreak, South Carolina would need to achieve 95% vaccination across the state, or at minimum in the affected counties. Given that some schools have 79% unvaccinated students, achieving that threshold requires active outreach, addressing vaccine hesitancy, providing access, and overcoming exemptions.

The Role of School Exemptions in Disease Spread

School exemptions are the regulatory mechanism through which vaccination rates crash. States require certain vaccinations for school entry, but states also allow exemptions. The details matter tremendously.

Some states allow only medical exemptions—if a child genuinely cannot receive vaccines due to severe allergies or medical conditions, that's legitimate. Other states allow philosophical or personal exemptions, meaning you can opt out just by stating you don't want vaccines. Still others allow religious exemptions.

The problem with non-medical exemptions is they scale with cultural trends. When anti-vaccine sentiment grows, more people file exemptions. Schools that historically had high vaccination rates suddenly see it drop as more parents seek exemptions. That's what happened at places like Global Academy in South Carolina.

Once you have pockets of unvaccinated children—especially in schools with close contact throughout the day—measles can spread rapidly. A single infected child exposing 30 classmates, who then expose their families, who then expose their workplaces. The virus chains through communities following patterns of human contact.

Some states have responded by making exemptions harder to obtain. They require parents to watch educational videos about vaccination before granting exemptions. They require face-to-face meetings with healthcare providers. Some states have eliminated non-medical exemptions entirely. These measures improve vaccination rates.

But during a period when national political leadership is hostile to vaccine mandates and promotes vaccine skepticism, states have less political cover to restrict exemptions. That makes disease control harder.

Government Response and Public Health Infrastructure

The official response to the South Carolina outbreak has involved multiple layers. The state health department is coordinating the response. County health departments in affected areas are working with schools and employers. Healthcare providers are receiving guidance on recognizing and reporting measles cases. Vaccination clinics are being set up to provide rapid access to the vaccine.

But public health infrastructure in many states has been deteriorating for years. Funding cuts have reduced the capacity of local health departments. Staff shortages mean fewer people are available for outbreak response. These structural weaknesses became apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic and haven't been fully addressed since.

When you're responding to an outbreak that's generating new cases daily, you need enough epidemiologists to do contact tracing, enough nurses to provide vaccinations, enough administrative staff to coordinate the response. States stretched thin can't respond as effectively.

Additionally, conflicting political messages about vaccines undermine public health messaging. When elected officials express skepticism about vaccine safety or question vaccine mandates, it becomes harder for health departments to convince skeptical populations to get vaccinated. The credibility of public health institutions suffers.

A significant 87% of the 646 confirmed measles cases were completely unvaccinated, highlighting the critical role of vaccination in preventing outbreaks.

What Makes 2025 Different: Why This Year Could Be Worse

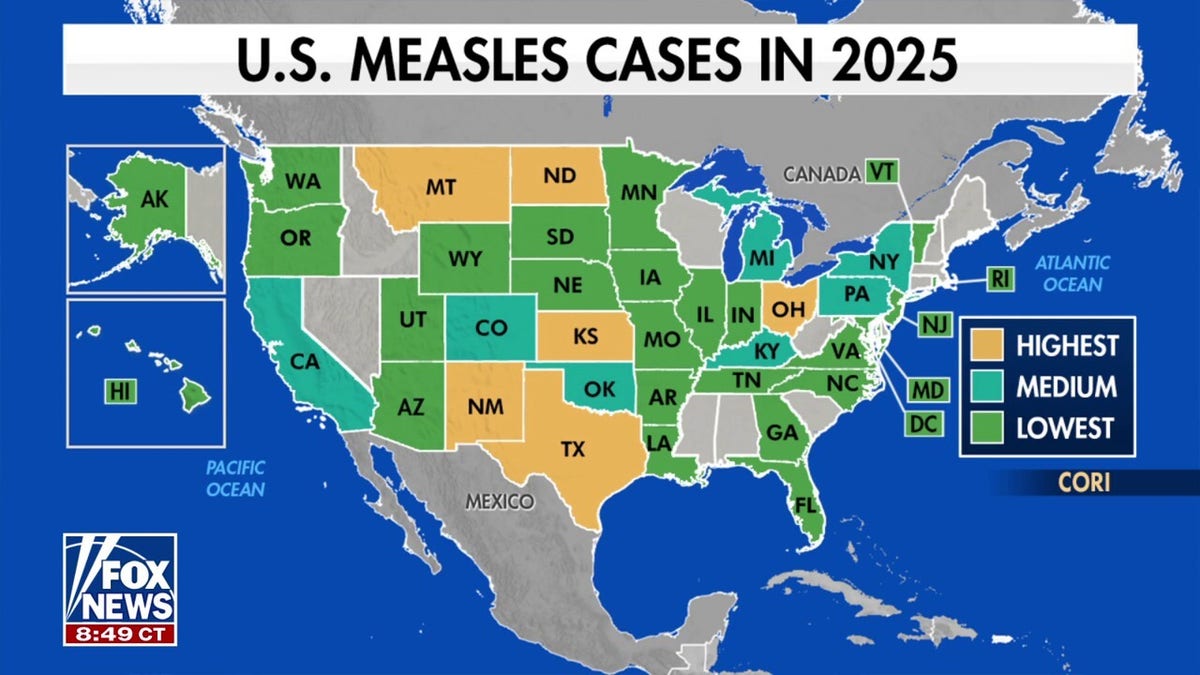

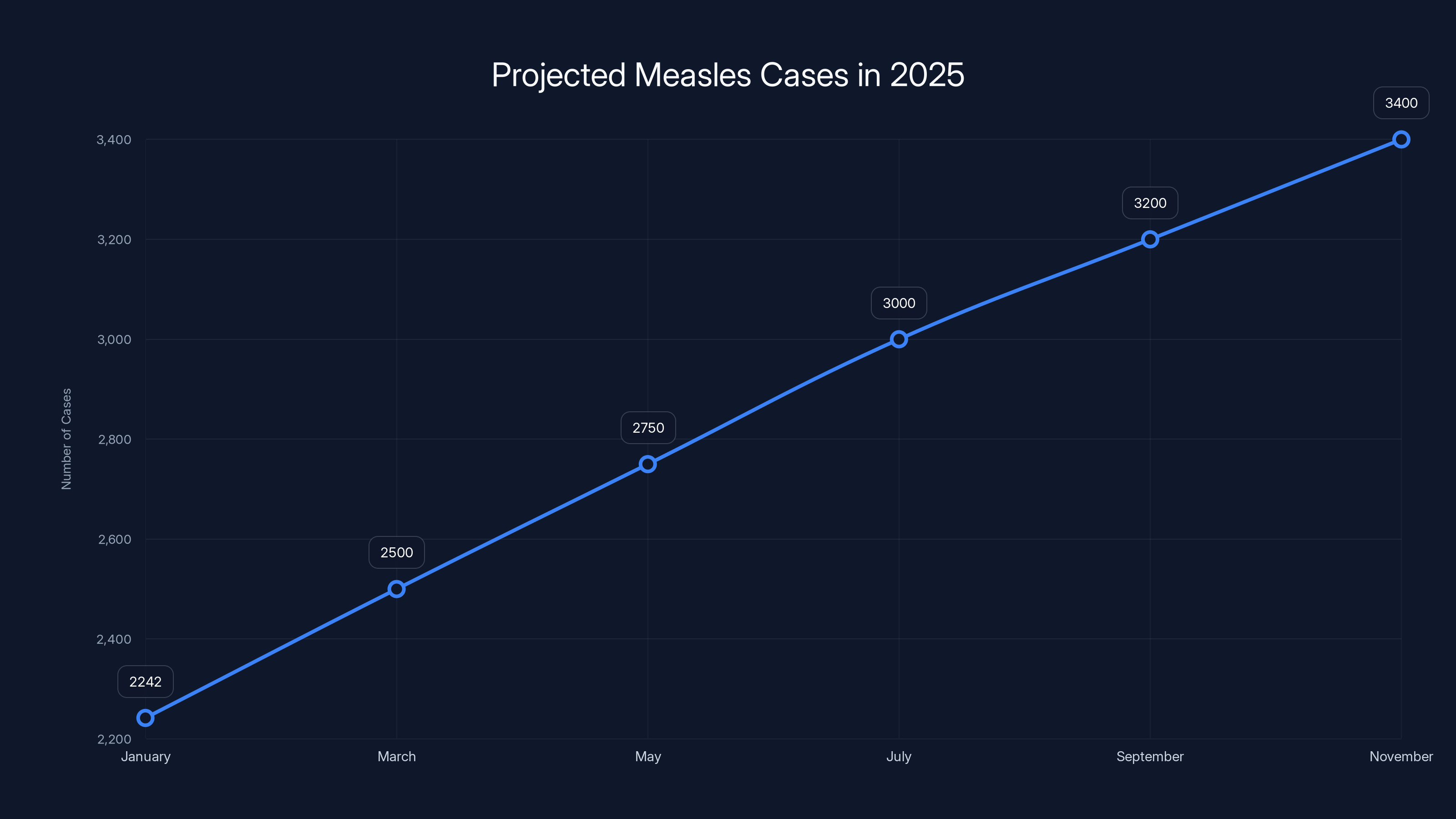

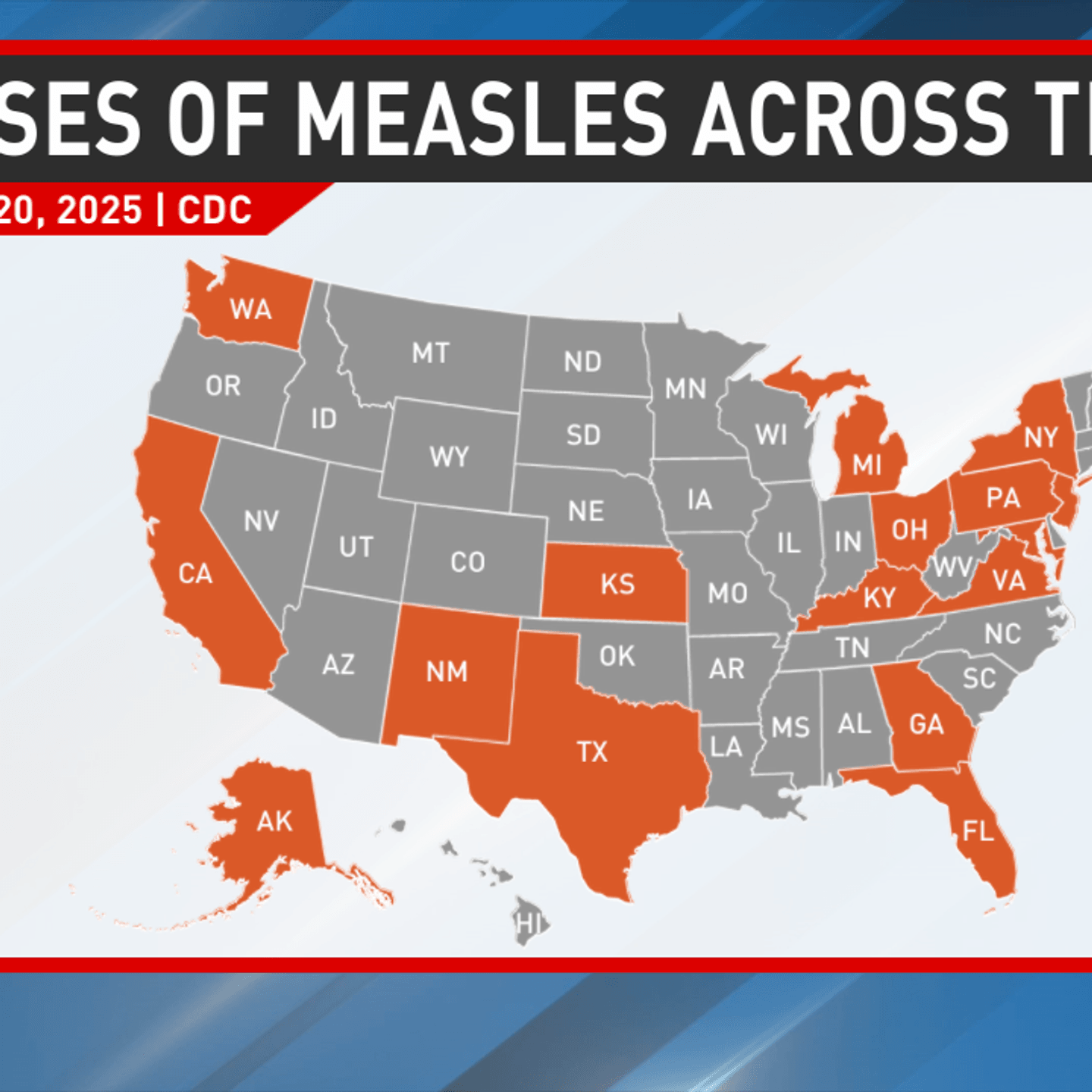

Asking why 2025 specifically presents challenges requires understanding several convergent trends. First, there's the raw numbers. With 2,242 cases in 2025 and the South Carolina outbreak still climbing, this is already a high year. If the outbreak continues through spring or summer, we could see total cases exceed 3,000.

Second, vaccination rates are trending downward nationally. More states are falling below the 95% community protection threshold. That means more geographic areas where measles can circulate. Fewer places have the immunity wall needed to stop transmission.

Third, political headwinds against vaccines are stronger than they've been in years. What was fringe skepticism a decade ago has become mainstream political rhetoric. Some elected officials have made opposition to vaccines a core campaign platform. That shifts the public conversation.

Fourth, people's memory of measles has faded. It's easy to not take measles seriously when you've never seen it, when your parent hasn't experienced it, when it's been absent for years. Threats that feel historical seem less urgent than threats that feel immediate.

Finally, social media amplifies misinformation at unprecedented scale. A parent worried about vaccines can find hundreds of convincing-sounding anti-vaccine arguments on social media within minutes. The information environment is fundamentally different from even 10 years ago.

All these factors align toward a scenario where measles gets worse before it gets better. We're not predicting what will happen. We're observing the conditions and recognizing they're conducive to larger outbreaks.

International Context: How This Compares Globally

Zooming out to a global perspective provides useful context. In developed countries with strong vaccination programs, measles has been nearly eliminated. But that elimination is fragile. It requires sustained high vaccination rates and constant vigilance.

Other developed nations—Australia, Canada, much of Europe—maintain higher MMR vaccination rates than the United States and experience far fewer measles cases. When outbreaks happen in those countries, they're typically contained more quickly because of higher background immunity.

In developing countries with weaker vaccination infrastructure, measles remains a significant cause of childhood mortality. WHO estimates measles causes over 100,000 deaths globally annually, mostly in children under age 5. Nearly all those deaths are preventable through vaccination.

The United States sitting somewhere between developed countries with strong programs and developing countries with weak programs is both a failure of public health and a reminder of what's possible if vaccination rates decline further.

Vulnerable Populations and Why Equity Matters

Measles outbreaks don't affect populations equally. Unvaccinated children are at highest risk. Immunocompromised individuals who can't be vaccinated are at high risk even in vaccinated communities if immunity rates fall. Healthcare workers and first responders who encounter infected patients face exposure risk.

But there's also a socioeconomic dimension. Access to vaccination varies. Rural areas might have fewer vaccination clinics. Uninsured or underinsured individuals might face cost barriers despite vaccines being free through public programs. Language barriers can prevent some immigrants from accessing vaccination services. Distrust of institutions—sometimes rooted in legitimate historical grievances—might make some communities hesitant to use official health services.

An equitable response to measles prevention requires addressing these access and trust barriers. It means getting vaccinations to rural areas. It means ensuring no cost barriers exist. It means working with community leaders to build trust. It means providing information in multiple languages.

But equity considerations also take resources and intentional effort. When public health infrastructure is underfunded and there's political hostility toward vaccines, equity often gets deprioritized.

Projected data suggests measles cases could exceed 3,000 by mid-2025 due to declining vaccination rates and increased misinformation. Estimated data.

Prevention Strategies: What Actually Works

Preventing measles is straightforward in theory: maintain 95% vaccination rates. The challenge is executing that in practice given political opposition, vaccine hesitancy, and access barriers.

Direct vaccination efforts are essential. Vaccination clinics at schools, workplaces, community centers, and healthcare facilities make vaccines accessible. They're the frontline intervention.

But equally important is communication. Clear, honest messaging about vaccines and measles helps counter misinformation. Healthcare providers explaining to patients why vaccination matters is powerful. Trusted community members—local leaders, teachers, parents—advocating for vaccination carries weight.

Addressing exemptions matters too. Either by making non-medical exemptions harder to obtain or by continuing to improve vaccination rates even in contexts where exemptions exist.

For vulnerable immunocompromised individuals, protection comes through others being vaccinated. They can't rely on their own immunity. They rely on community immunity. That's why maintaining high vaccination rates is a moral obligation—it protects people who can't protect themselves.

The Role of Healthcare Providers

Physicians, nurse practitioners, and other healthcare providers are on the front line of both prevention and response. They administer vaccines. They counsel hesitant patients about vaccine safety and efficacy. They recognize measles cases and ensure proper reporting. They treat complications.

When providers enthusiastically recommend vaccination, it matters. Studies consistently show that a provider's recommendation is one of the most influential factors in a patient's decision to vaccinate. If a trusted doctor says vaccination is important, people listen.

But providers also need support. They need access to current data about vaccine safety and efficacy. They need training on addressing vaccine hesitancy effectively. They need the time and resources to have these conversations.

During outbreaks, providers also become educators. They need to explain to worried patients what measles actually is, what the symptoms are, what to do if they're exposed. They become part of the public health response even outside their normal clinical practice.

Looking Forward: Predictions and Possibilities for the Rest of 2025

Based on current trends, several scenarios seem possible for the remainder of 2025.

In the optimistic scenario, South Carolina's outbreak peaks within the next few weeks and begins declining as vaccination rates rise and the pool of susceptible individuals shrinks. New outbreaks happen in other areas but are contained relatively quickly. Total measles cases for the year remain under 5,000. Vaccination rates stabilize and begin improving.

In the middle scenario, the South Carolina outbreak continues for several more months with additional smaller outbreaks appearing in other states. Total cases for the year reach 4,000-6,000. Vaccination rates continue declining slightly. Healthcare systems handle the load but with significant strain in some areas.

In the concerning scenario, the South Carolina outbreak becomes endemic in certain communities, with continuous circulation. Multiple other large outbreaks happen. Vaccination rates fall further as political opposition to vaccines strengthens. Total cases exceed 8,000. Some states experience healthcare system strain. Deaths and serious complications increase notably.

The actual outcome depends on multiple factors outside anyone's control—whether vaccination campaigns prove successful, whether new outbreaks start in high-population-density areas, whether political messaging about vaccines improves or worsens, whether misinformation succeeds in further undermining vaccine confidence.

What Individuals Can Do Now

If you're unvaccinated or unsure about your vaccination status, getting the MMR vaccine now is the most important step. It's free or low-cost through most public health departments and many healthcare providers. If you're a parent of school-age children, check their vaccination status. If they're not fully vaccinated with two MMR doses, contact your doctor.

If you're immunocompromised, talk to your healthcare provider about your specific situation. You might be vaccinated already, or your provider might recommend avoiding vaccination if your immune system is severely compromised. Either way, you want to understand your personal risk.

If you're in a high-risk setting—healthcare work, teaching, childcare—ensuring your immunity is especially important.

Beyond personal protection, you can advocate for vaccine confidence in your community. If you hear misinformation about vaccines, you can politely correct it with accurate information. You can talk to friends and family about why vaccination matters. You can support policies that maintain vaccine requirements for school attendance.

The Bigger Picture: Rebuilding Public Trust in Public Health

Ultimately, preventing another year like 2025 requires rebuilding public trust in public health institutions. That's a long-term project that extends far beyond any single outbreak.

Public health agencies need to communicate clearly and honestly. They need to admit when they don't know something rather than projecting false certainty. They need to explain their reasoning in terms the public can understand. They need to acknowledge that vaccines, like all medical interventions, have rare side effects, while emphasizing that the benefits overwhelmingly outweigh the risks.

Healthcare providers need training in addressing vaccine hesitancy with compassion rather than dismissal. People who are hesitant aren't necessarily anti-vaccine. They might simply want more information or need their concerns addressed respectfully.

Political leaders need to resist weaponizing public health. Vaccines shouldn't be partisan issues. But when political figures oppose vaccine requirements on principle, it sends a message that vaccines might be questionable. That makes the public health job harder.

Media needs to provide accurate information and avoid false balance—presenting vaccine skeptics alongside vaccine experts as if they have equivalent credibility.

These are structural changes requiring sustained effort. They won't happen quickly. But they're necessary for rebuilding the public health infrastructure that allows disease prevention to work.

Why This Matters Beyond Measles

Measles is the immediate crisis, but the underlying issue is broader. The erosion of vaccination rates, the politicization of public health, the undermining of institutional credibility, the spread of medical misinformation—these affect disease prevention across the board.

If measles vaccination rates fall significantly, we should expect to see higher rates of mumps and rubella as well. If pertussis vaccination rates fall, we'll see more whooping cough cases, especially dangerous for infants too young to be vaccinated. If polio vaccination rates fall, we risk polio's return—a virus that can cause permanent paralysis.

The infrastructure that keeps these diseases at bay is the same infrastructure used for responding to emerging diseases and pandemics. If that infrastructure deteriorates, if public trust erodes, if political opposition to public health grows, we become more vulnerable to all infectious disease threats.

Measles is a warning. It's a visible reminder that disease prevention requires collective effort, ongoing vaccination, maintained immunity, and institutional credibility. When any of those slip, the consequences become apparent quickly.

FAQ

What is measles and how serious is it?

Measles is a highly contagious viral infection spread through respiratory droplets. It causes high fever, cough, runny nose, and a characteristic blotchy rash. While many people recover without serious complications, measles can cause pneumonia (the leading cause of measles-related death in children), encephalitis (brain inflammation), and severe immune system weakening that makes you vulnerable to secondary infections for months. In the pre-vaccine era, measles killed hundreds of Americans annually and left thousands with permanent brain damage.

Who is most at risk from measles?

Infants under 12 months, children under 5, adults over 20, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals face the highest risk of severe measles. However, anyone who is unvaccinated can develop serious complications. Even previously healthy teenagers and adults can require hospitalization for measles pneumonia or other complications. Immunocompromised individuals who are vaccinated still face risk if they don't develop adequate immunity from the vaccine.

How does the MMR vaccine work?

The MMR vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine containing weakened versions of measles, mumps, and rubella viruses. When injected, it triggers your immune system to produce antibodies against these viruses without causing serious disease. Two doses provide 97% protection against measles infection. The vaccine works by teaching your immune system to recognize the virus so it can fight it off if you're exposed to the actual virus later.

Why are vaccination rates declining despite the vaccine being safe and effective?

Multiple factors contribute to declining rates: complacency (the disease seems absent, so vaccination feels unnecessary), misinformation on social media, political opposition to vaccine mandates, increased exemptions from school vaccine requirements, distrust of institutions, and the fading of collective memory about how serious these diseases are. Once a generation grows up without seeing measles, the urgency to vaccinate diminishes even though the disease risk remains.

What should I do if I think I've been exposed to measles?

If you've potentially been exposed, monitor yourself for symptoms for 21 days. Early signs include high fever, cough, runny nose, and eye irritation. If you develop these symptoms followed by a rash, contact your healthcare provider immediately and mention possible measles exposure so they can take appropriate precautions. If you're unvaccinated and exposed, contact your doctor about post-exposure vaccination, which can prevent infection if given within 72 hours of exposure.

Is the MMR vaccine safe?

Yes, extensive research spanning decades shows the MMR vaccine has an excellent safety profile. Serious side effects are extremely rare. The most common side effects are mild—soreness at the injection site, low-grade fever, or rash. The vaccine does not cause autism (the fraudulent study making this claim was retracted and its author lost his medical license). The vaccine does not contain microchips or tracking devices. Millions of people have been safely vaccinated with MMR.

What percentage of the population needs to be vaccinated to stop measles transmission?

A vaccination rate of at least 95% with both doses of the MMR vaccine is needed to provide community protection. At this rate, the virus can't spread efficiently enough to sustain transmission because there aren't enough unvaccinated people for it to infect. Below 95%, measles can continue circulating indefinitely through the unvaccinated population, especially in areas where unvaccinated people cluster.

Why do immunocompromised people depend on others being vaccinated?

Some immunocompromised individuals cannot receive vaccines because their immune system is too weak to respond to the vaccine's signal. Others can be vaccinated but don't develop adequate immunity due to their condition. These people rely entirely on herd immunity—when enough of the surrounding population is vaccinated that the disease can't reach them. If vaccination rates fall below 95%, this vulnerable population suddenly faces serious risk.

The Bottom Line

The measles crisis of 2025 isn't inevitable, but it's also not accidental. It results from deliberate choices: to seek vaccine exemptions, to spread misinformation, to politicize public health, to undermine institutional credibility. These choices stack on top of each other, incrementally weakening our collective immunity until we're vulnerable to a disease that vaccination had nearly eliminated.

The South Carolina outbreak with its 646+ cases serves as a real-time demonstration of what happens when vaccination rates fall. It's not a worst-case scenario. It's what we're watching happen right now. And unless something changes—unless vaccination rates improve, unless political hostility toward vaccines recedes, unless public trust in public health rebounds—expect worse.

The vaccine exists. It's safe. It's effective. It's accessible. What's missing is collective will to use it. That will has to come from somewhere. It comes from individuals choosing to vaccinate. From parents protecting their children. From healthcare providers advocating for vaccination. From political leaders supporting vaccines instead of opposing them. From media reporting accurately about disease and prevention.

Measles doesn't care about your political beliefs or your skepticism about institutions. It simply spreads when enough unvaccinated people cluster together. We can prevent that. We've done it before. We can do it again. But it requires choosing prevention over politics, trust in evidence over viral videos, and the common-sense understanding that some collective action—getting vaccinated—genuinely protects all of us.

The clock is ticking. The outbreak continues. The cases keep climbing. And every person who remains unvaccinated is another potential link in the chain of transmission. What happens next is still being written. The question is what role you'll play in that story.

Key Takeaways

- Measles cases reached 2,242 in 2025, the highest count in 30+ years, with South Carolina's outbreak showing 646+ cases and climbing daily

- 87% of South Carolina measles cases involved completely unvaccinated individuals, demonstrating vaccine effectiveness and the danger of low immunization rates

- National MMR vaccination rates have fallen below 95%, the threshold needed to prevent community transmission and protect vulnerable immunocompromised individuals

- Vaccine exemptions are surging, with some South Carolina schools reporting only 21% of students fully vaccinated, creating conditions for rapid measles spread

- Political opposition to vaccines and widespread misinformation on social media are undermining public health messaging and eroding institutional credibility

![Why the US Faces Surging Measles Cases in 2025 [Guide]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-the-us-faces-surging-measles-cases-in-2025-guide/image-1-1769081916081.jpg)