Introduction: The Biggest Constellation in Human History Just Got Bigger

On a Friday afternoon in 2025, the FCC quietly made a decision that will reshape how billions of people access the internet. SpaceX got the green light to launch 7,500 more Starlink satellites. Not a minor regulatory tweak. Not a small expansion. A fundamental shift in what's possible for global connectivity.

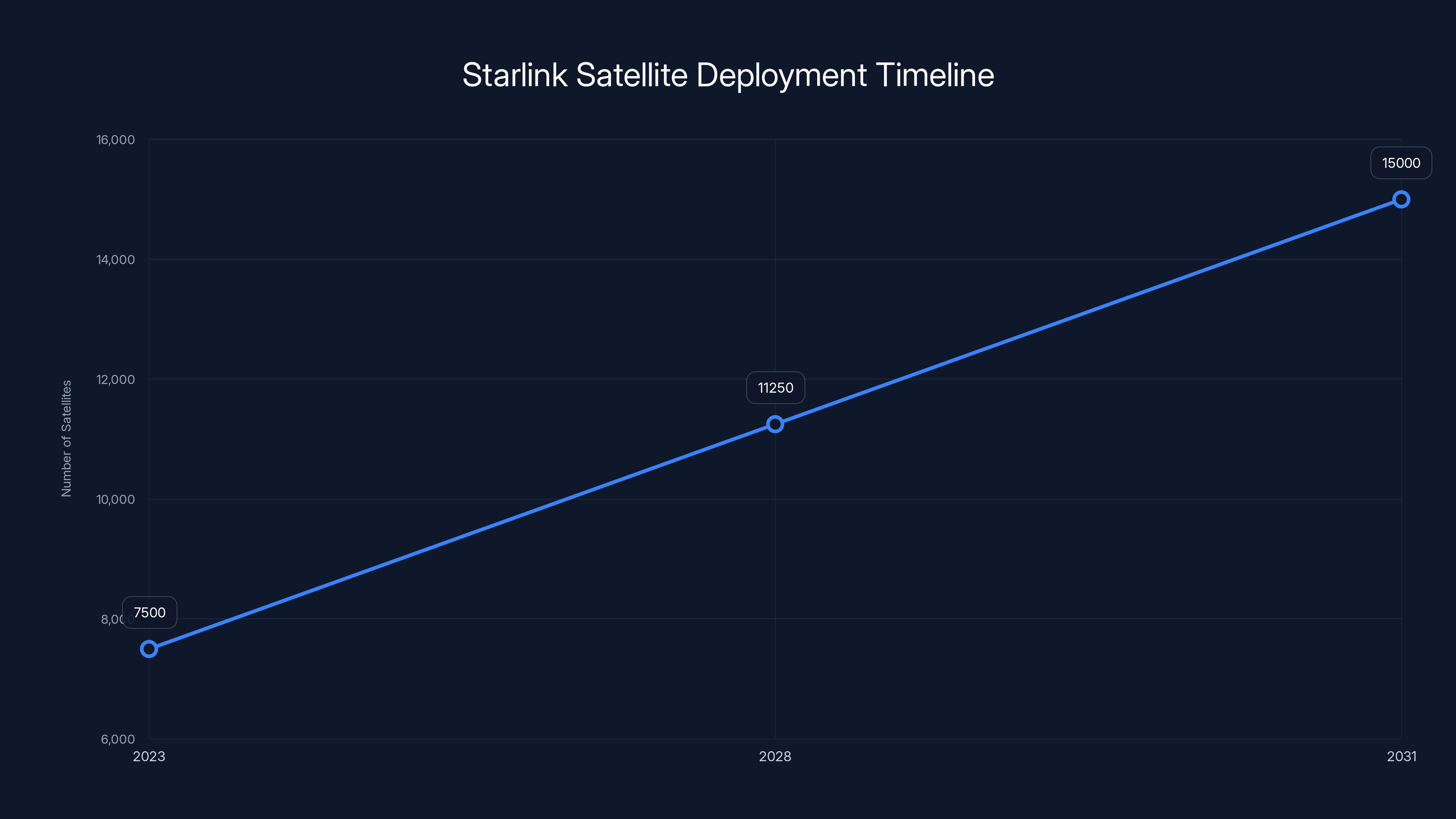

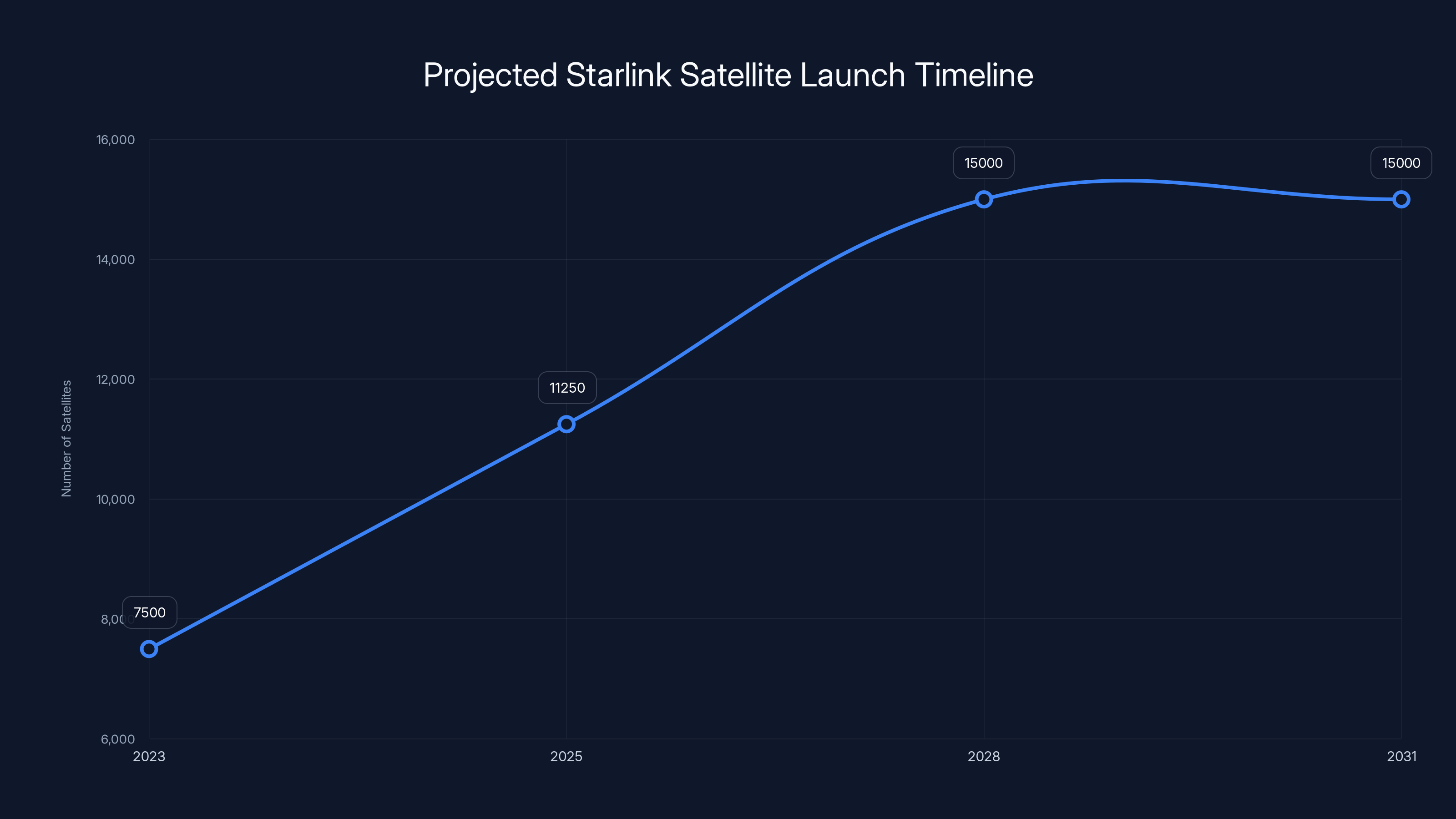

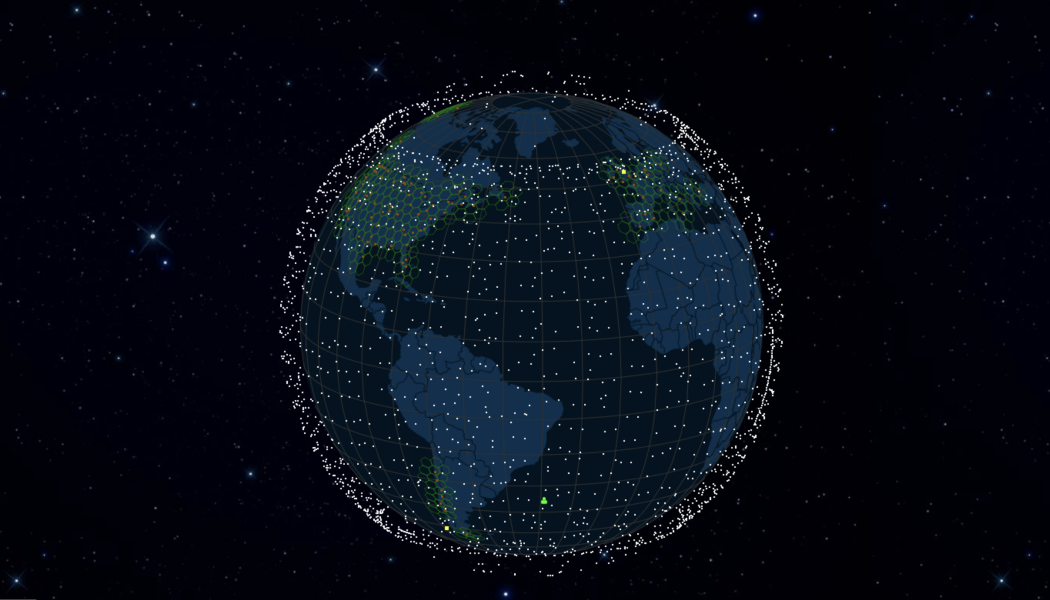

Let me be direct: this isn't just about faster internet speeds. This is about a company building a satellite network so massive that it will eventually outnumber every other space object humanity has ever launched combined. By the end of 2031, SpaceX plans to have 15,000 satellites in orbit. That's not hyperbole. That's the FCC's approval as reported by Reuters.

Here's what's wild: SpaceX originally asked for 30,000 satellites. The FCC said "pump the brakes" and approved 15,000 for now. But that's still staggering. For context, the International Space Station is one satellite. The entire global GPS constellation is about 30 satellites. Starlink alone will be orders of magnitude larger.

Why does this matter to you? Because satellite internet is about to stop being a novelty and start being infrastructure. Direct-to-cell connectivity in remote areas. Internet speeds hitting 1 Gbps in places where broadband never reached. A global network that doesn't care about undersea cables or ground-based infrastructure. These aren't promises. They're deadlines embedded in the FCC's approval.

But here's the tension nobody wants to talk about: 15,000 satellites in Low Earth Orbit means light pollution for astronomers, more space debris, and collision risks that grow exponentially. SpaceX already had to lower orbits of existing satellites this year to reduce collision probability. Adding 7,500 more satellites makes that problem worse, not better.

The FCC approved this anyway. Why? Because the government calculated that global connectivity, direct-to-cell coverage outside the US, and 1 Gbps speeds were worth the trade-offs. Whether that math works out in reality is a different question.

This article breaks down what actually happened, what it means for SpaceX's dominance in satellite internet, the environmental and technical costs, and why this approval matters far beyond the tech industry.

TL; DR

- FCC Approved 7,500 Additional Satellites: SpaceX can now launch Gen 2 Starlink satellites to reach 15,000 total by end of 2031

- Speed to Deadline: 50% of new satellites must launch by December 2028, with remaining 50% by December 2031

- Global Connectivity Promise: Direct-to-cell access and up to 1 Gbps speeds in previously underserved areas

- Space Debris Trade-off: More satellites means increased collision risk and light pollution concerns from astronomers

- Market Dominance: SpaceX's constellation will be at least 10x larger than any competing satellite internet network

The FCC has approved SpaceX to expand its Starlink constellation to 15,000 satellites by 2031, with key deployment milestones in 2028 and 2031. Estimated data based on FCC deadlines.

What the FCC Actually Approved: Breaking Down the Decision

The FCC's Friday approval wasn't ambiguous. SpaceX gets authorization to launch 7,500 Gen 2 Starlink satellites. But the devil is in the regulatory details, and those details tell you everything about how the government views satellite internet's importance.

The approval includes something crucial: waiving previous coverage restrictions. Before this, SpaceX couldn't have overlapping satellite coverage in certain regions. Those rules were designed to prevent any single company from monopolizing orbital real estate. The FCC just eliminated that constraint for Starlink.

What does overlapping coverage mean in practical terms? More satellites, same geographic area. More satellites means redundancy, faster speeds, and better connection reliability. If your Starlink connection drops to one satellite, you've got nine others as backup. That redundancy is why network engineers obsess over constellation density.

The approval also waives previous capacity enhancement restrictions. Translation: SpaceX can launch satellites with upgraded capabilities without filing additional requests for each batch. This saves months of regulatory review for every launch.

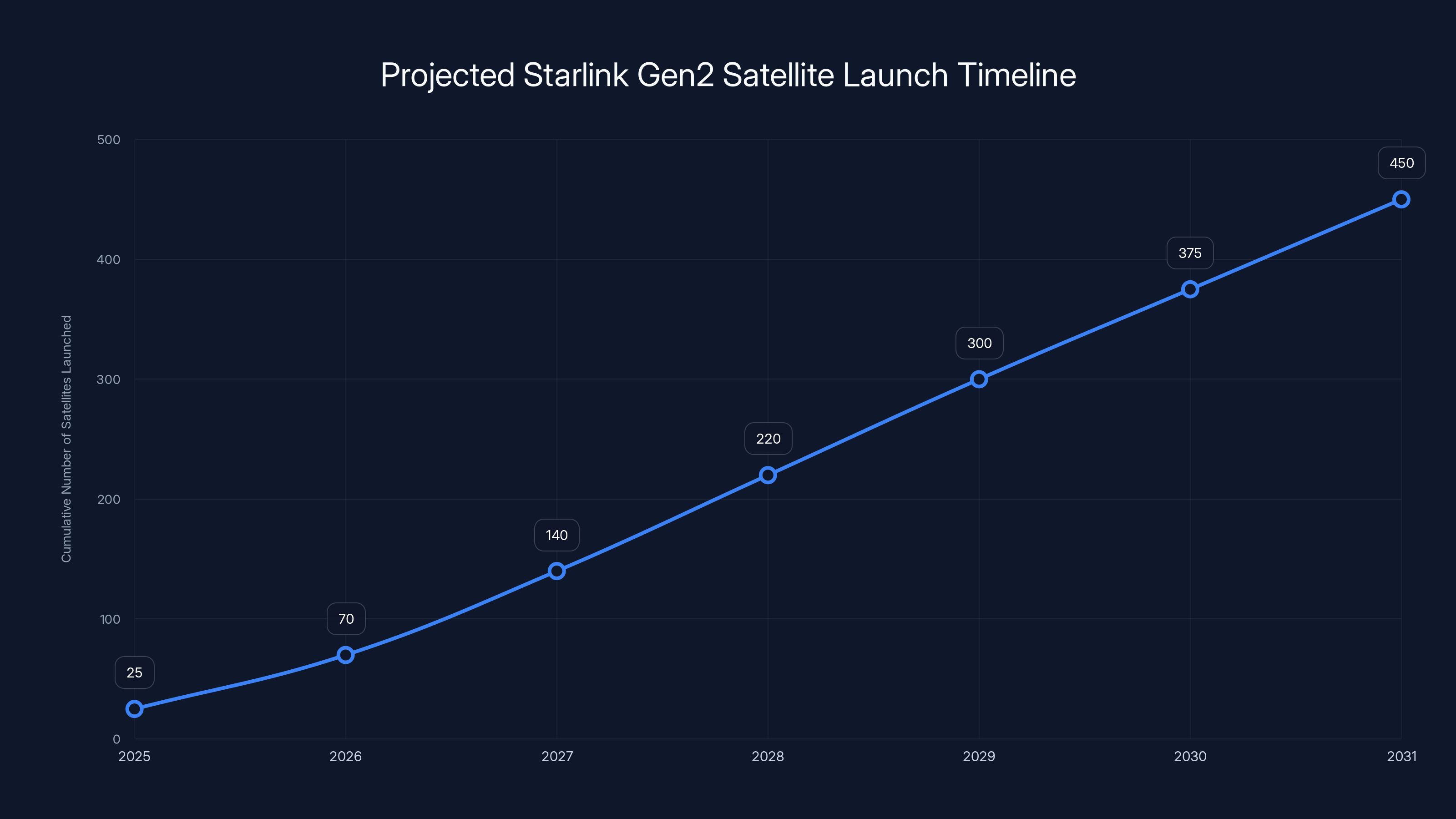

But the FCC attached conditions. Strict ones. SpaceX must have 50% of Gen 2 satellites launched and operational by December 1st, 2028. That's about 3,750 satellites in roughly three-and-a-half years. The remaining 3,750 must be operational by December 2031. These aren't suggestions. These are regulatory deadlines with teeth.

Why such tight timelines? The FCC wants to prevent SpaceX from getting approval, waiting five years, and never actually launching. Real deadlines force real execution. SpaceX has the infrastructure to hit these targets, but they're aggressive targets nonetheless.

The approval process itself was contentious. SpaceX originally requested authorization for 30,000 satellites. The FCC said no. Partly due to orbital debris concerns. Partly due to environmental impact studies. Partly because having one company control two-thirds of all satellites in Low Earth Orbit raises every regulatory alarm imaginable.

The approval filing runs hundreds of pages. Most of it is standard regulatory language. But three points emerge:

First, SpaceX convinced the FCC that 15,000 satellites won't create catastrophic space debris problems. The company presented collision probability models, debris mitigation strategies, and orbital decay calculations. Engineers calculated that with proper spacing and deorbiting procedures, the constellation is manageable.

Second, the government determined that global internet access outweighs astronomer concerns about light pollution. Professional observatories have complained loudly. Starlink satellites reflect sunlight and create streaks across long-exposure images. These ruined certain types of astronomical observations. The FCC essentially said: "This is unfortunate, but we're moving forward anyway."

Third, direct-to-cell connectivity proved decisive. This means Starlink satellites can connect directly to existing cell phones without special ground equipment. In areas without terrestrial towers, your regular iPhone suddenly has emergency calling and texting capability. The FCC weighted this heavily in approval calculations.

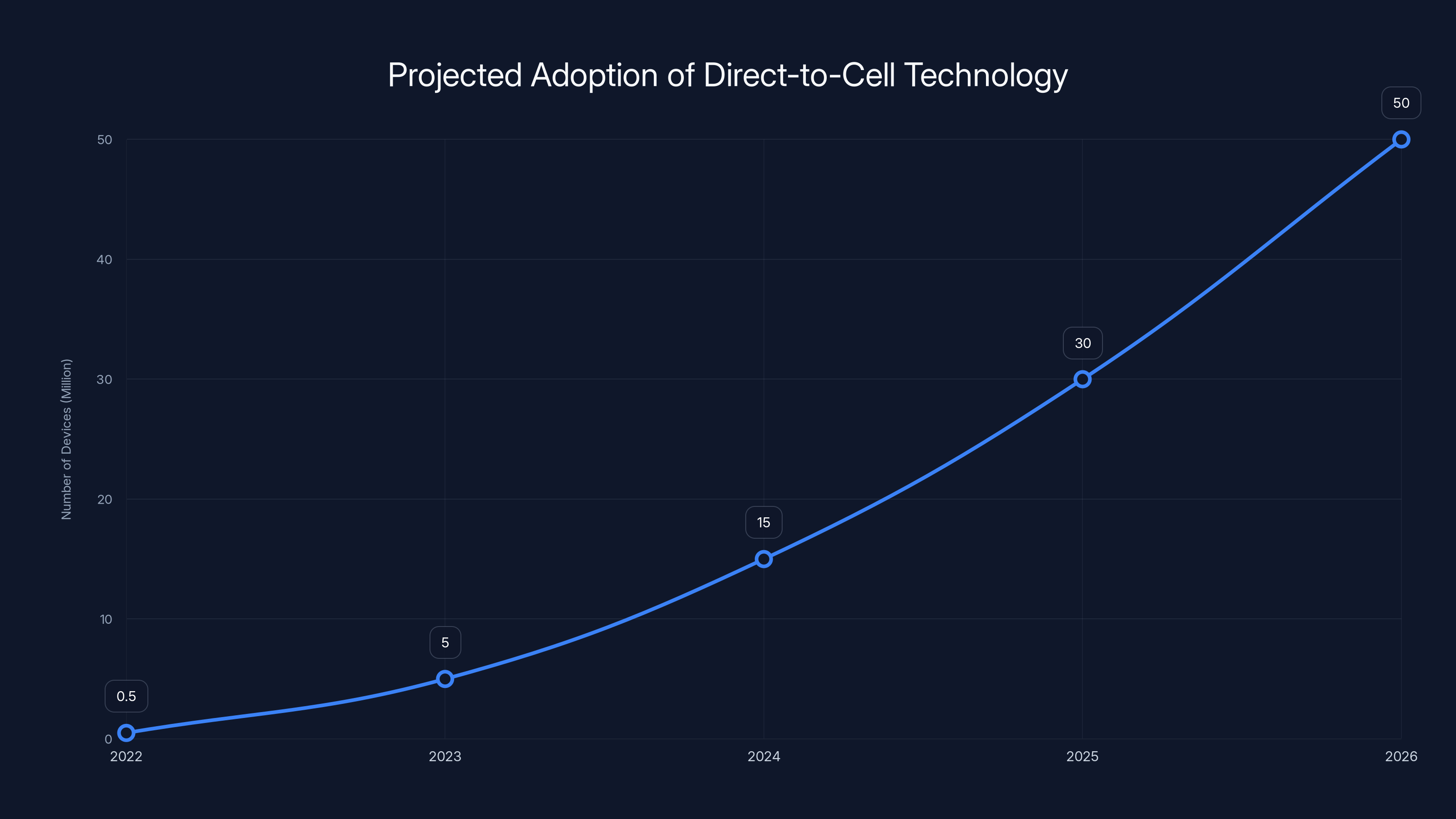

Estimated data suggests rapid growth in direct-to-cell adoption, reaching 50 million devices by 2026, driven by emergency connectivity needs.

The Timeline: When You'll Actually See These Satellites

Approvals are one thing. Execution is another. SpaceX has a proven track record with Starlink launches, but 3,750 satellites in three-and-a-half years is an intense operational target.

Let's do the math. SpaceX currently launches Starlink satellites in batches of approximately 55 satellites per Falcon 9 launch. To deploy 3,750 satellites by December 2028, they'd need roughly 68 launches in 42 months. That's approximately 1.6 launches per month, focused exclusively on Starlink Gen 2 satellites.

SpaceX's manifest includes other missions: National Security Payloads, commercial customers, NASA contracts, Starshield launches. Starlink is the money-maker, but it's not the only business. The company has about 80 Falcon 9 launches scheduled annually across all missions. Dedicating 20+ of those to Starlink Gen 2 is feasible but aggressive.

Here's the realistic timeline:

2025 to mid-2026: Ramping up Gen 2 launch cadence. SpaceX starts with existing infrastructure, gradually converting launch schedules to prioritize the new satellites. You'll see maybe 20-30 Gen 2 launches.

mid-2026 to 2028: Peak deployment phase. SpaceX targets 30-40 Gen 2 launches annually. They might add infrastructure, use additional Falcon 9 vehicles, or optimize turnaround times. This is when the constellation density increases noticeably.

November 2028: Deadline crunch. SpaceX either hits 50% deployment or faces regulatory scrutiny. If they're behind, we'll see all hands on deck for final launches.

2029 to 2031: Second half deployment. The remaining 3,750 satellites roll out on a similar cadence. Less urgency than the first deadline, but the December 2031 endpoint still creates pressure.

What changes in orbit during this period? In 2025, Starlink covers most inhabited landmass sparsely. By 2027, coverage becomes denser. By 2028, the constellation reaches critical mass: redundancy everywhere, faster speeds, reliable direct-to-cell connectivity. By 2031, Starlink shifts from "satellite internet provider" to "global infrastructure."

During this timeline, expect orbit adjustments. SpaceX will need to maintain optimal spacing, move satellites to optimal inclinations for coverage, and deorbit older Gen 1 satellites to clear congestion. This ballet in space happens constantly but accelerates with more satellites.

One more thing: every launch also includes a de facto test of SpaceX's reusable rocket technology. Starlink launches are SpaceX's best customers for boosters. Each Gen 2 launch tightens operational efficiency for everyone else relying on Falcon 9 capacity.

The 15,000 Satellite Constellation: Scale and Implications

Let's put 15,000 satellites in perspective, because numbers this large become abstractions. Your brain breaks. 15,000 is beyond intuitive comprehension.

There are roughly 8,000 active satellites in orbit right now (across all companies, all countries). SpaceX's constellation will almost double the entire global satellite population.

Compare to competitors:

Amazon's Project Kuiper: Plans for 3,236 satellites. That's a massive constellation by any standard. Starlink Gen 2 will be 4.6 times larger.

OneWeb: Currently operating about 600 satellites. Their full constellation targets ~6,000. Still dwarfed by Starlink.

China's GW Constellation: Announced plans for 13,000 satellites, which would rival Starlink. However, progress has been slow, and launches are far behind schedule.

Traditional telecom satellites: Geosynchronous orbit hosts roughly 500 active satellites. These are massive, expensive, and cover continents. Starlink replaces 500 with 15,000, each smaller but networked.

Why does constellation size matter this much? Because in satellite internet, coverage density equals service quality. More satellites overhead means:

- Lower latency: Fewer satellites skip from ground to space to ground. More direct routing.

- Higher capacity: Bandwidth is shared among satellites. More satellites means more total capacity.

- Better redundancy: When one satellite moves out of range, another's waiting. Connection never drops.

- Faster handoff: As your location moves, satellites hand off faster with more options.

Technically, it works like this. Your Starlink dish connects to the satellite with the strongest signal. As that satellite moves overhead and reaches the horizon, your dish automatically switches to the next satellite. With 15,000 satellites, handoff delays drop from seconds to milliseconds. Users never notice the switch.

With smaller constellations, that handoff takes longer. Your connection momentarily weakens. Video calls stutter. This is why Amazon's smaller Project Kuiper constellation will always have inferior latency compared to Starlink, all else equal.

But here's the tension: denser constellation means denser orbits. More satellites in the same orbital shell means higher collision probabilities. This is where the space debris problem gets thorny.

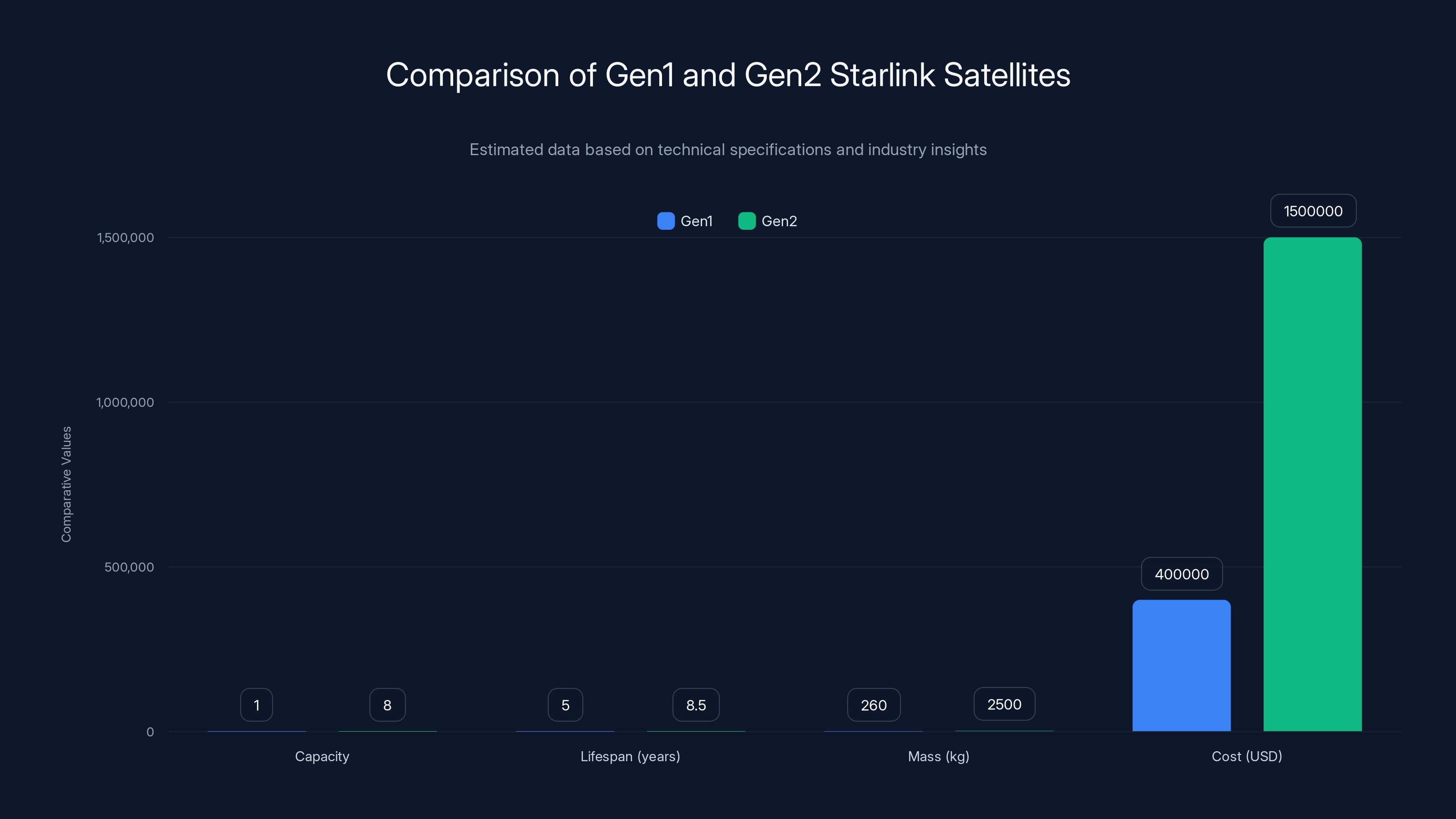

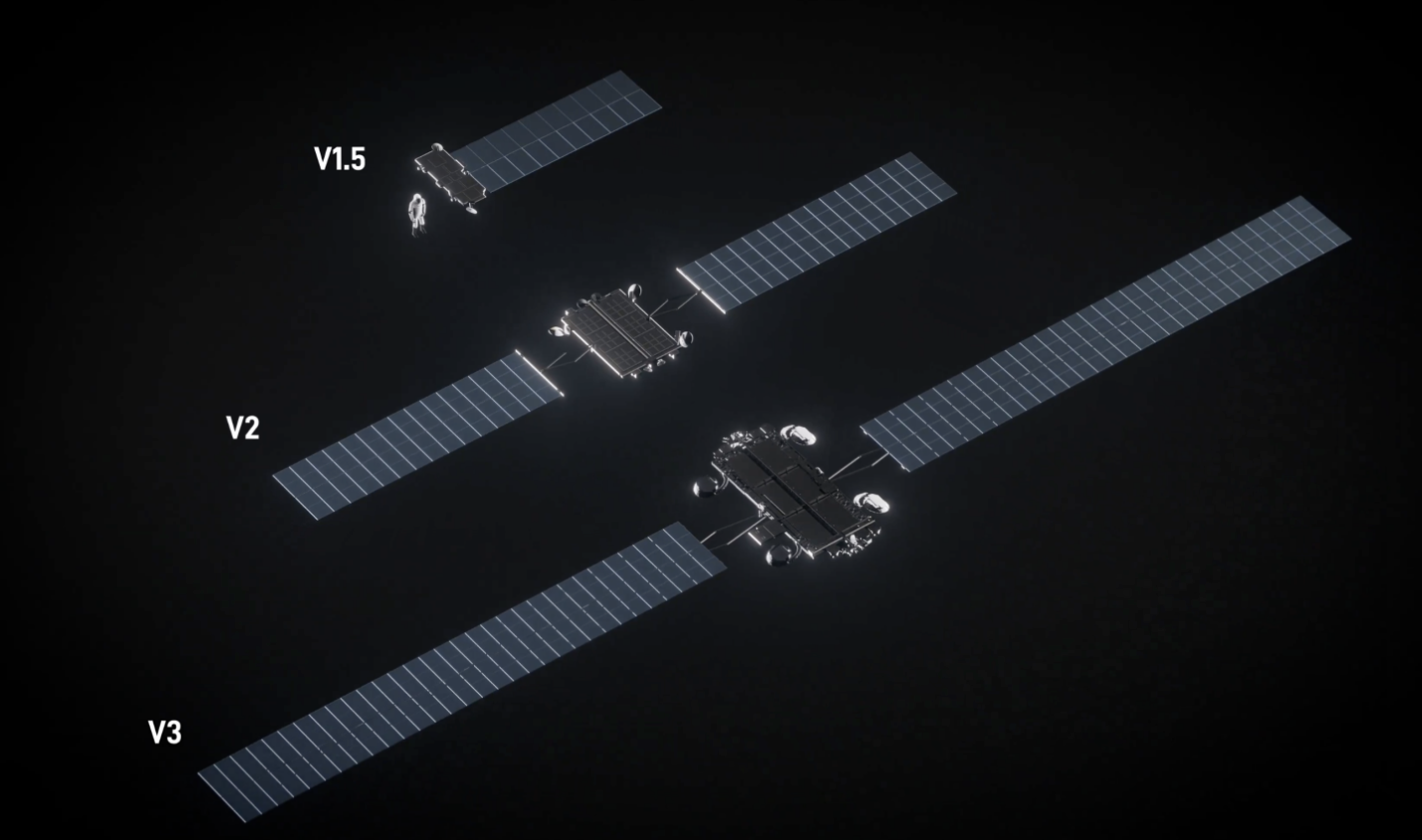

Gen2 satellites significantly outperform Gen1 in capacity, lifespan, and robustness, despite higher costs. Estimated data based on available information.

The Space Debris Problem: A Real Cost Nobody Talks About

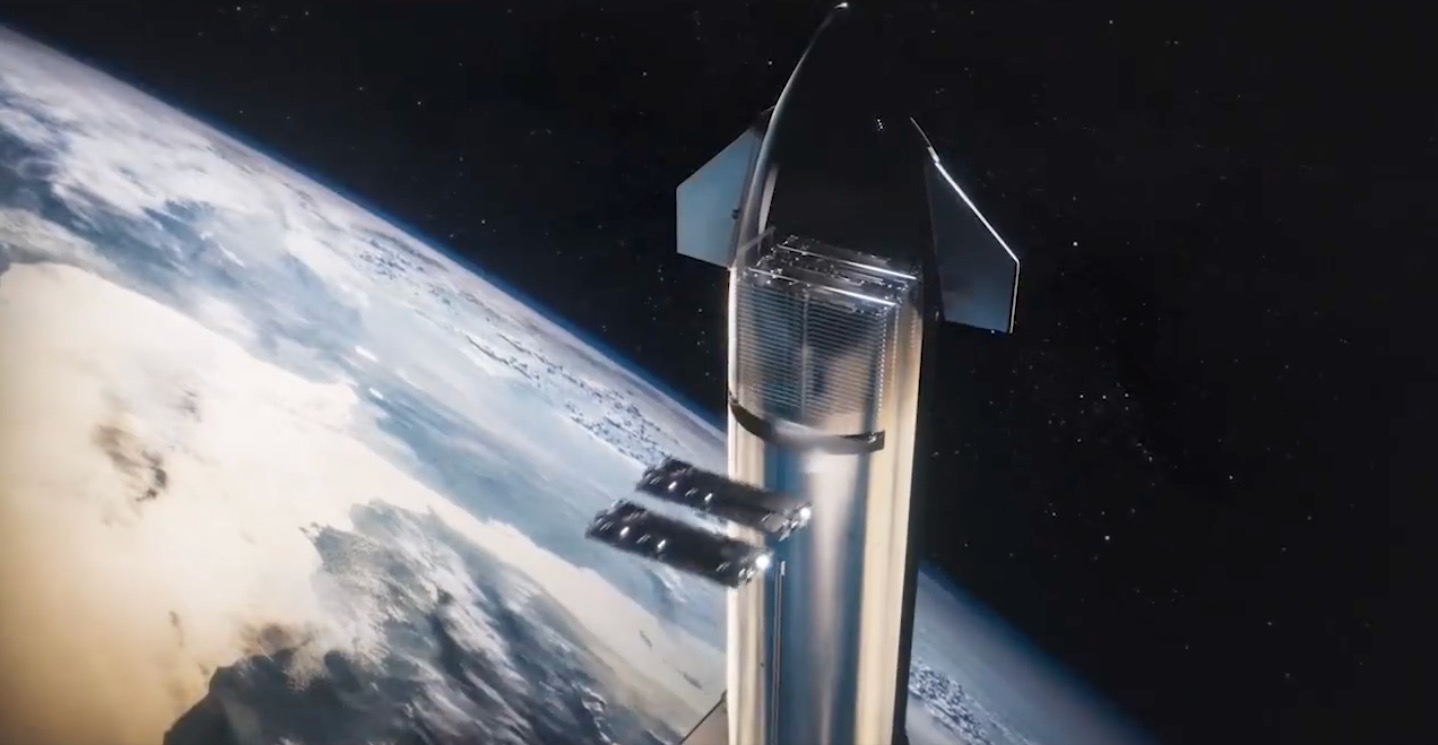

Every satellite is both a tool and a potential weapon. When it dies, it becomes space junk. And space junk moves at terrifying speeds.

In Low Earth Orbit, satellites travel at roughly 17,500 miles per hour. A collision between two objects at these velocities releases energy equivalent to a bomb. SpaceX satellite vs. debris the size of a marble? That marble will punch through your satellite like a bullet through aluminum foil.

The problem isn't theoretical. In 2009, an active Iridium communications satellite collided with a defunct Russian satellite. Debris from that collision continues threatening other spacecraft. The probability of a cascade effect exists: one collision creates debris, debris hits another satellite, which creates more debris, exponentially. Scientists call this Kessler Syndrome. It's space's version of a doomsday scenario.

Current orbital tracking can identify objects larger than about 10 centimeters. Below that threshold, tracking becomes impossible. Below 1 centimeter, there are millions of debris pieces nobody can track.

SpaceX mitigates this risk through:

Active deorbiting: Starlink satellites have fuel reserved for end-of-life burns. When a satellite dies, SpaceX fires thrusters to lower its orbit. Instead of staying in space forever, it falls back to Earth and burns up in the atmosphere within 5-10 years. Compare this to traditional satellites that remain in orbit for decades.

Collision avoidance: SpaceX monitors orbital trajectories continuously. When debris approaches a satellite, ground controllers issue a "maneuver command." The satellite fires thrusters and moves out of the way. SpaceX performs hundreds of these maneuvers monthly.

Spacing protocols: Starlink satellites maintain minimum spacing to prevent close approaches. They're distributed across multiple orbital shells and inclinations, not all stacked at one altitude.

Government coordination: SpaceX shares orbital data with NASA and military tracking systems. The U.S. military has the most sophisticated orbital tracking capability globally. They help identify conjunction risks before they become critical.

But and this is a big but. More satellites means more probability of incidents despite precautions. SpaceX lowered the orbit of existing Starlink satellites in 2025 specifically to reduce collision risks with space stations and other debris. Moving 6,000+ satellites to new orbits is a massive undertaking. Adding 7,500 more makes the problem more complex.

The FCC evaluated these risks and decided they're acceptable. They required SpaceX to maintain deorbiting procedures, continue collision avoidance efforts, and report incidents. But there's no legal way to prevent all collisions. The FCC essentially accepted some additional collision risk as the cost of global satellite internet.

Light pollution is a related but different problem. Starlink satellites are bright. Not bright enough to see during the day, but bright enough that during twilight and early night hours, they create streaks across the sky. Long-exposure astronomical photographs capture these streaks. They ruin data.

SpaceX deployed VisorSat, a sunshade device, to reduce brightness. It works: satellites with VisorSat are significantly dimmer than earlier models. But VisorSat adds weight, complexity, and cost. Not all new satellites will have it. This is a trade-off SpaceX makes.

Astronomers have been surprisingly vocal about this. Professional organizations sent letters to the FCC opposing approval. Their argument: astronomical research benefits all of humanity, and satellite constellation expansion compromises that benefit. The FCC listened, but ultimately prioritized internet access over observation capabilities.

It's a legitimate disagreement without a perfect answer. More connectivity or clearer skies? The FCC chose connectivity.

Direct-to-Cell: The Killer App That Justified Approval

Here's why the FCC probably approved this despite all the concerns: direct-to-cell connectivity.

Most Starlink users today need a ground terminal. A rectangular box about the size of a tablet. You point it at the sky, plug it in, and you have internet. But "point it at the sky and plug it in" doesn't work in an emergency when you're lost in the mountains with a dying phone.

Direct-to-cell means your regular smartphone can connect directly to Starlink satellites without any special hardware. You don't need ground equipment. You don't need apps. You just use your phone as normal, and when you're out of terrestrial coverage, Starlink becomes your fallback.

SpaceX demonstrated this in 2022 by sending emergency texts through Starlink satellites using an iPhone 14. It worked. The message went from phone to satellite to ground station to SMS network.

The implications are enormous. Anybody with a mobile phone gets emergency connectivity globally. This is the FCC's stated justification for the approval. In their regulatory calculus, direct-to-cell emergency access justifies accepting more space debris risk and light pollution concerns.

Here's how it works technically:

- Phone broadcasts on standard cellular frequencies (no modifications needed)

- Starlink satellites receive the signal (using a different antenna than internet-providing phased arrays)

- Signal is routed to a ground station

- Ground station converts it to normal SMS or data

- Message reaches the SMS network and delivers normally

The reverse works for incoming messages. Text arrives at ground station, gets relayed to Starlink satellite, and reaches your phone.

Initially, direct-to-cell will handle text and emergency data only. Not video or streaming. But in an emergency, text is what matters.

The market implications are staggering. Global handset makers want direct-to-cell capability. Apple's integrating it in iPhones. Google's doing the same with Pixel phones. Samsung too. Eventually, every smartphone has satellite fallback built-in.

This changes the calculus for remote work. Construction crews in remote areas. Emergency responders. Hikers. Maritime vessels. Fishing fleets. Agricultural operations. Anyone working in coverage gaps suddenly has reliable communication.

The business model shifts too. Starlink isn't just selling internet to people in remote areas who have nowhere else to turn. Now it's selling emergency connectivity to everybody, even people with perfect terrestrial coverage. They might pay $5-10 monthly for the peace of mind that their phone has emergency backup.

The FCC's approval essentially says: "This technology is important enough that we're approving 7,500 more satellites specifically to make direct-to-cell ubiquitous." Astronomers and space debris experts might disagree, but in the regulatory calculus, emergency connectivity won.

SpaceX aims to launch 15,000 satellites by 2031, with half by 2028. Estimated data based on FCC deadlines.

Speed Promises: Gigabit Internet from Space

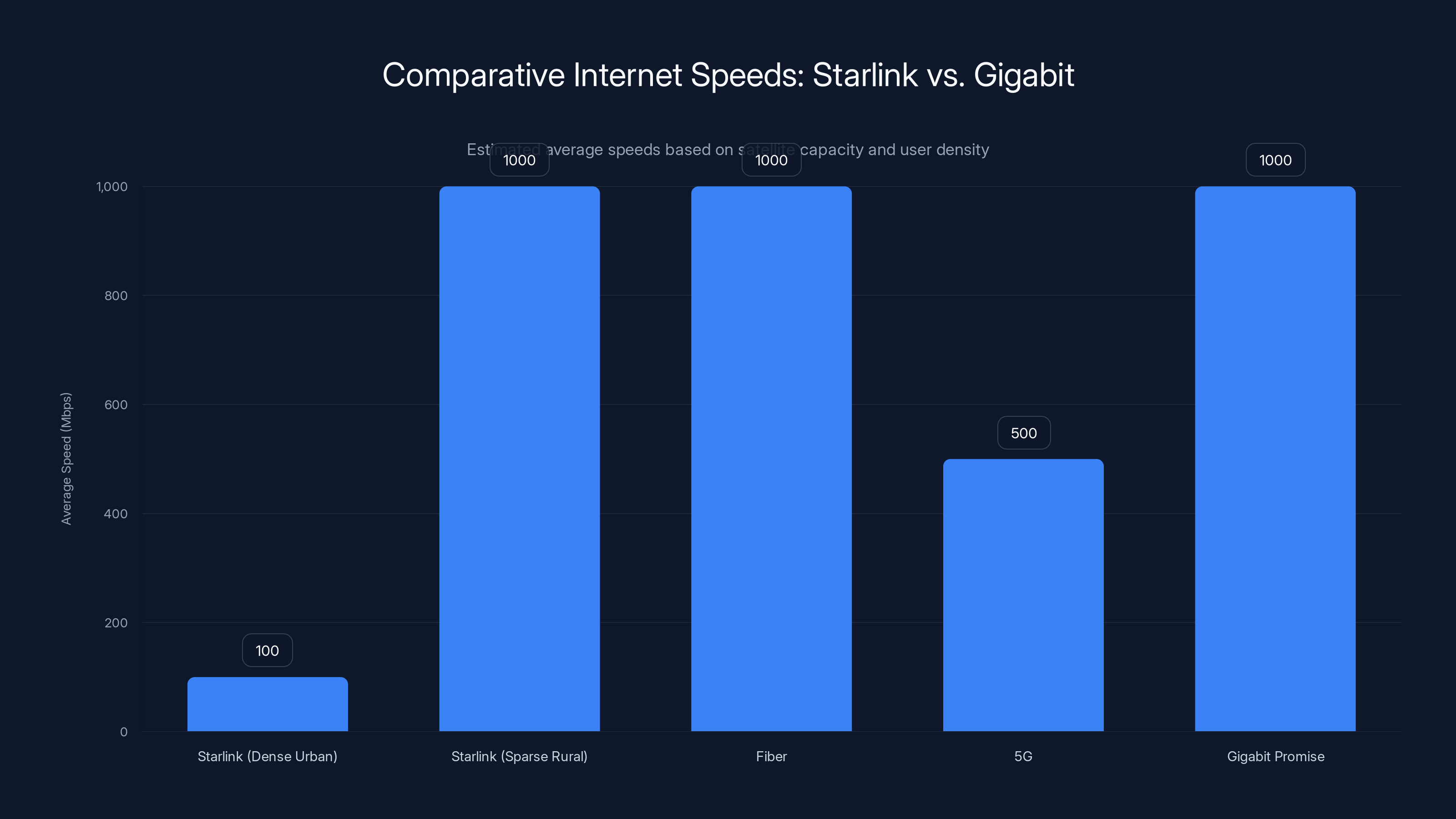

The approval documentation mentions something that often gets overlooked: 1 Gbps speeds. That's one gigabit per second. For context, that's fast enough to download a 10 GB movie in roughly 10 seconds.

SpaceX currently advertises Starlink speeds of 100-200 Mbps in most areas. Some locations see higher, some lower. A gigabit is 5-10 times faster.

Can satellites actually deliver this? Yes, but with caveats.

SpaceX's Gen 2 satellites have significantly higher capacity than Gen 1. They're equipped with larger phased arrays, more processing power, and higher frequency bands for communication. Each satellite can handle more simultaneous connections.

But here's the constraint: bandwidth is finite. Each satellite has a total throughput budget. Let's say a Gen 2 satellite can deliver 500 Gbps total capacity. If 10,000 users connect to that satellite simultaneously, average throughput per user is 50 Mbps. Basic math.

With 15,000 satellites instead of 6,000, you're multiplying capacity by 2.5x. That's significant. But it doesn't linearly increase individual user speeds. It increases the total network capacity.

However, in areas with sparse user density, that means fewer people sharing each satellite's capacity. In rural Montana or Australian Outback, maybe only 100 people connect to a single satellite at any given time. Those 100 people can split 500 Gbps of capacity. That's 5 Gbps per person. In theory. In practice, add latency constraints, weather effects, and network overhead, and you're looking at gigabit speeds becoming achievable for users in sparse areas.

In dense urban areas? Starlink will never compete with fiber or 5G networks because neither fiber nor 5G has the physics constraints of satellite connections.

The speed promise in the FCC approval is therefore carefully qualified. SpaceX commits to delivering 1 Gbps in "optimal conditions" in certain areas, not everywhere.

But even 500 Mbps globally changes the connectivity landscape. Satellite internet no longer needs to be a compromise. It becomes a genuine alternative to fiber for home internet, especially in cost-prohibitive deployment areas.

The Regulatory Game: Why Musk Got This Approval

Let's talk politics for a moment, because this FCC approval didn't happen in a vacuum.

Elon Musk and the Trump administration had a very public falling out earlier in 2025. Starlink satellites were used in Ukraine for military communications. The U.S. government became concerned about relying on a private company's infrastructure for critical defense and humanitarian operations. Political tensions increased.

But then something shifted. SpaceX and the administration started mending fences. Musk's Grok AI project had positive government attention. X's integration with government services looked possible.

The FCC approval happened during this reconciliation period. Was the approval political? Cynically, yes, probably somewhat. But that misses the larger point.

The FCC approval is also genuinely defensible on merit. Satellite internet is important. 15,000 satellites with proper mitigation addresses real regulatory concerns. Direct-to-cell connectivity is genuinely valuable. Government approval of major infrastructure projects often happens for mixed reasons: merit and politics together.

What's notable: neither major party opposed the approval. Democratic commissioners and Republican commissioners both voted for it. This wasn't a partisan decision. Both sides recognized that satellite internet and direct-to-cell connectivity are infrastructure priorities.

But the timing's worth noting. SpaceX got approval when it needed it: after losing favored-nation status with one administration, they secured something better. A bipartisan consensus that their satellite network is critical infrastructure.

The approval also benefits future administrations. Whichever party's in power, Starlink is now embedded in national communications infrastructure. It's harder to restrict or regulate when it's already essential.

For SpaceX, the approval is a massive win. They get to build their planned constellation without fighting satellite-by-satellite battles with regulators. They get 3,750 additional satellites approved. And they got waiver of previous restrictions that would have slowed deployment.

The cost? Deadlines. SpaceX has to execute on the timeline or face regulatory consequences. But SpaceX has proven execution capability with Starlink. They hit targets.

The timeline shows an estimated increase in Starlink Gen2 satellite launches, with peak deployment between mid-2026 and 2028. Estimated data based on operational targets.

The Competitive Landscape After Approval

Amazon's Project Kuiper doesn't look competitive after this approval.

Amazon's constellation will eventually have 3,236 satellites spread across three orbital shells. Ambitious, well-funded, and operational by 2027 timeframes. But 3,236 satellites versus Starlink's 15,000? The network effect heavily favors Starlink.

Why network effects matter in satellite internet:

More satellites = more capacity = lower prices. Starlink's scale lets them undercut competitors on price. Amazon can't match that scale economics.

More satellites = better latency = faster performance. This is physics. More satellites overhead means faster handoff times and shorter signal paths. Starlink wins on technical grounds.

More satellites = broader coverage = easier adoption. People buy internet where it works best. Starlink works almost everywhere. Competitors will cover major population centers but not remote areas. Starlink's ubiquity becomes an advantage.

Direct-to-cell requires scale. SpaceX's Gen 2 constellation reaches 15,000. That's enough satellite density to make direct-to-cell work globally. Amazon's smaller constellation can't achieve the same effect.

Amazon will still succeed with Project Kuiper. They'll target enterprise customers and areas Starlink neglects. But they won't achieve market dominance. Starlink's network effects lock in its position.

China's GW constellation represents the only real long-term competitive threat. 13,000 satellites rivals Starlink's size. But Chinese satellite internet development is years behind SpaceX. By the time GW reaches full operational capability, SpaceX will be onto next-generation satellites.

Europe has been discussing sovereign satellite internet capability. The EU approved funding for IRIS2, a constellation of 170 satellites in geostationary orbit supporting secure communications. But IRIS2 is narrowly focused on government/military, not consumer internet. It won't compete with commercial constellations.

The approval essentially cements SpaceX's dominance in the consumer satellite internet market for the next decade.

The Future: 2031 and Beyond

What happens after 2031 when the 15,000-satellite deadline arrives?

SpaceX will have deployed its approved constellation. Coverage everywhere. Direct-to-cell functionality global. Speeds in the gigabit range in optimal conditions.

But SpaceX won't stop. Satellites age. They'll request approval for replacements. The next generation constellation will be even more advanced. Better capacity, lower latency, improved efficiency.

The FCC probably anticipates this. Approving 15,000 is not a ceiling. It's a foundation. SpaceX will continue growing the constellation for decades.

What else changes by 2031?

Legislation around space traffic. More satellites means regulating orbital highways. ITU coordination becomes critical. Spectrum allocation between satellite operators needs formal governance. International treaties evolve.

Space tourism and commercial operations. More satellites create orbital crowding. Space hotels, manufacturing platforms, and research stations need deorbiting infrastructure. Space becomes genuinely trafficked.

Military integration. Governments weaponize satellite internet. Tactical communications, intelligence satellites, counterspace capabilities. SpaceX's network becomes militarized.

Climate research implications. Satellite internet enables remote sensors globally. Climate monitoring networks expand. Weather forecasting improves. But light pollution affects climate-relevant astronomical observations.

Economic shifts. Remote work becomes genuinely feasible anywhere on Earth. Real estate patterns shift. Labor markets globalize further when internet connectivity is universal.

The 15,000-satellite approval is not the end of SpaceX's plan. It's a chapter. By the 2030s, we'll probably be debating approvals for 20,000 or 25,000 satellites.

In sparse rural areas, Starlink can potentially offer speeds close to the gigabit promise due to fewer users per satellite. However, in dense urban areas, speeds are lower due to higher user density. Estimated data.

Market Impact: Who Benefits and Who Loses

This approval has clear winners and losers.

Winners:

- SpaceX: Approved to build their vision with minimal regulatory friction. Cements market dominance.

- Starlink consumers: Future subscribers get global coverage and gigabit speeds. Existing subscribers see improved service.

- Remote workers: Anywhere becomes workable. Location independence becomes practical everywhere.

- Emergency responders: Direct-to-cell backup means always-on communication capabilities.

- Satellite manufacturers: Companies building smaller satellites for Starlink get more contracts and revenue.

- SpaceX competitors in launch services: More satellites mean more launch contracts. Rocket Lab, Axiom Space, and others benefit from launch demand.

Losers:

- Terrestrial broadband providers: Starlink becomes viable alternative for home internet even in areas previously protected by monopoly providers. AT&T and Comcast face new competition.

- Traditional satellite operators: Viasat and Intelsat operate expensive geostationary satellites. Starlink's low-cost constellation undercuts their pricing power.

- Amazon's Project Kuiper: Smaller constellation means perpetual second-place position. Amazon's still profitable, but competitive advantage evaporates.

- Dark sky advocates and professional astronomers: More satellites mean more light pollution, more observation disruption, and less advocacy leverage.

- Space debris researchers: More satellites complicate their work. Tracking and modeling becomes harder. Collision probability rises despite mitigation efforts.

- Government space agencies (non-U.S.): National space programs lose autonomy as U.S. private companies dominate orbital infrastructure. Strategic sovereignty concerns rise.

The distribution of winners and losers reveals why the FCC approved this despite opposition. Connectivity benefits (consumers, remote workers, emergency responders) outnumber inconveniences (astronomers, fiber ISPs) in political weight.

The Environmental Calculus: Trade-Offs Nobody Wants to Admit

Let's be frank about what the FCC approval means environmentally.

More satellites, more launches. More launches means more rocket fuel consumed and more carbon emissions. SpaceX's Falcon 9 burns RP-1 (kerosene) and liquid oxygen. Each launch produces roughly 200 metric tons of CO2 emissions.

At 70 launches annually dedicated to Starlink Gen 2, that's 14,000 metric tons of CO2 yearly just from launch vehicles. For context, the average American produces about 16 metric tons of CO2 annually. SpaceX's Starlink deployment is equivalent to the annual carbon footprint of roughly 900 Americans.

Is that acceptable? The FCC implicitly said yes. They didn't perform a detailed carbon accounting. They focused on collision risk, light pollution, and spectrum coordination. Climate impact wasn't central to the approval decision.

But here's the counter-argument: satellite internet enables remote work globally. Remote work reduces commuting. Fewer cars on roads. Less gas consumed. If Starlink prevents 100,000 people from commuting daily, that saves more CO2 than the launches produce.

This is speculative. We don't know how many commute miles Starlink will prevent. Counting environmental benefits is harder than counting rocket fuel consumption.

There's also space debris deorbiting. When satellites deorbit and burn in the atmosphere, they release particulates. Aluminum oxide and other spacecraft materials accumulate in the upper atmosphere. Long-term effects are unknown. Some research suggests this could affect ozone and climate. Other research downplays the effect.

The FCC didn't deeply investigate this either. They trusted SpaceX's assessment that the impact is acceptable.

The environmental trade-off is real but uncertain. More launches produce carbon. More satellites produce atmospheric particulates. But these are offset (partially?) by reduced terrestrial transportation and expanded economic opportunity in previously disconnected regions.

Honestly, the FCC probably didn't care about carbon accounting. They cared about political viability, which meant approving something that genuinely matters: global internet access and emergency connectivity.

Environmental groups didn't heavily oppose the approval, which tells you they're ambivalent about the trade-offs too.

Practical Implications: What This Means for You

Abstract regulatory approvals are irrelevant if they don't change your life. So what actually changes for real people?

If you live in a rural area without broadband:

Starlink becomes more reliable. Better speeds. More consistent latency. By 2028, Starlink transitions from "acceptable fallback" to "legitimate broadband alternative." You get options instead of monopoly pricing from your cable provider.

If you're an outdoor enthusiast or emergency responder:

Direct-to-cell connectivity reaches your region faster. Your phone's emergency SOS becomes practical even in coverage dead zones. This is genuinely life-changing if you hike, sail, or work in remote areas.

If you're a digital nomad or remote worker:

More locations become viable for work. Current Starlink works fine for remote work in most places. Gen 2 constellation makes it work in previously marginal areas. You get more location freedom.

If you live in an urban area:

Starlink remains secondary to fiber. You'll probably never switch. But competition from Starlink might force your ISP to improve speeds or lower prices to defend market share. You benefit indirectly.

If you're invested in space stocks:

This approval benefits SpaceX's valuation (if SpaceX ever goes public). It benefits SpaceX suppliers: constellation manufacturers, ground terminal makers, launch providers. It doesn't help Amazon's Project Kuiper or other competitors as much.

If you're an astronomer or dark sky advocate:

You lose. More satellites mean more light pollution and more observation disruptions. There's no silver lining here. This approval went against your interests.

If you're concerned about space debris or orbital safety:

You lose too. More satellites mean higher collision probability. Mitigation helps, but doesn't eliminate risk. The FCC basically said "we accept higher collision risk as the cost of connectivity." You probably disagree.

The approval is unambiguously good for some people and unambiguously bad for others. For most of us, it's neutral or mildly positive.

The Precedent: What This Approval Sets for Future Satellites

The FCC's decision creates precedent. Future mega-constellations will point to Starlink's approval and say "you let SpaceX do it, let us do it too."

Amazon will reference this approval when they ask the FCC to accelerate Project Kuiper approvals or relax constraints. They'll say "SpaceX got 15,000 satellites approved, why not 3,236 for us?"

China will point to this approval as evidence that the U.S. doesn't have legitimate space debris concerns, just competitive concerns. They'll argue for similar treatment of GW constellation.

Other countries will push for national mega-constellations. India's considering it. Japan's discussed it. The FCC's approval gives everyone a template.

What the FCC essentially did: they elevated satellite internet from "nice to have" to "critical infrastructure worthy of regulatory flexibility."

This opens the regulatory door. Future approvals will be easier because the precedent is set. "More satellites in orbit is acceptable if debris mitigation and coverage deadlines are met." That's the new standard.

Over the next decade, expect:

- 3-5 additional mega-constellations approved globally

- Orbital density increasing 2-3x

- More sophisticated space traffic management systems

- International treaties around orbital sovereignty

- New regulations around space debris liability

The Starlink approval is just the beginning of an orbital infrastructure race.

Technical Deep Dive: How Gen 2 Satellites Differ

Not all Starlink satellites are identical. Gen 2 satellites represent a major upgrade.

Capacity: Gen 2 satellites have roughly 8x the capacity of Gen 1 satellites. A single Gen 2 satellite can deliver more bandwidth than an entire constellation of earlier models. This is achieved through multiple innovations:

- Larger phased arrays: The antenna system is bigger, with more elements. More antenna elements = more simultaneous connections.

- Higher frequency bands: Gen 2 operates in higher frequency spectrum. Higher frequency = more bandwidth available.

- Advanced signal processing: Better algorithms for managing interference and optimizing connections.

- Larger solar panels: More power available for all systems. Power constraints don't limit performance.

Lifespan: Gen 2 satellites are designed for longer operational life. Gen 1 satellites had roughly 5-year lifespans. Gen 2 targets 7-10 years. This reduces the frequency of deorbiting and re-launches required.

Propulsion: Gen 2 satellites carry more fuel for collision avoidance and deorbiting maneuvers. They can execute more maneuvers before fuel depletion. They can also be remotely deorbited even after complete propulsion system failure, using solar sails or other passive techniques.

Mass: Gen 2 is significantly heavier than Gen 1. Roughly 2,500 kg versus 260 kg for Gen 1. The weight increase accommodates larger phased arrays, more fuel, and more processing power. This makes Gen 2 satellites more robust and capable.

Cost: Gen 2 satellites cost more per unit but deliver more value per unit. SpaceX doesn't publicly disclose exact costs, but industry estimates suggest

Direct-to-Cell capability: Gen 2 satellites have dedicated cellular antennas separate from internet-providing arrays. These cellular antennas can receive phone signals and relay them through the Starlink network without interrupting internet service. Gen 1 satellites lack this capability entirely.

The combination of these upgrades means Gen 2 constellation performs fundamentally differently than Gen 1 constellation. It's not just "more of the same." It's a generational leap.

Regulatory Review: Who Approved This and Why

The FCC doesn't operate in isolation. Multiple agencies reviewed the approval.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC): Primary authority for spectrum coordination and orbital licensing. They reviewed interference risks, spectrum conflicts, and compliance with international radio regulations.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA): Assessed collision risk with International Space Station and future space station elements. NASA's conjunction assessments identified potential conflicts. SpaceX had to address these.

Department of Defense (DoD): Reviewed national security implications. Military radar systems, early warning satellites, and defense infrastructure could be affected by massive new constellation. DoD reportedly expressed concerns but eventually supported the approval.

Department of State (State Department): Coordinated with international partners through diplomatic channels. Other countries' concerns about orbital sovereignty and resource allocation were addressed.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Reviewed environmental impact. Rocket emissions, upper atmosphere effects, light pollution. EPA didn't block approval but issued recommendations for mitigation.

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA): Coordinated launch licensing and airspace concerns. More launches mean more traffic through FAA-controlled airspace.

This multi-agency approval process took months. SpaceX submitted thousands of pages of technical documentation. Each agency raised concerns. SpaceX responded with mitigation strategies and data.

The final FCC vote was lopsided: strong approval with minimal dissent. All five commissioners (both Democrats and Republicans) voted to approve. This bipartisan consensus signals that nobody seriously opposed the decision on regulatory merits.

Opposition came from outside government: astronomy societies, dark sky advocates, some environmental groups. But these groups lack regulatory authority. The FCC listened to them but ultimately prioritized connectivity over their concerns.

International Implications: How Other Countries React

SpaceX is an American company. Starlink operates under U.S. regulatory authority. But satellites don't respect borders. The constellation affects every country.

European Union: The EU is concerned about American dominance of orbital infrastructure. They're developing IRIS2, a sovereign European constellation for government use. They're also considering faster approvals for Project Kuiper to avoid complete dependence on SpaceX. Strategic autonomy concerns are driving European policy.

China: Views Starlink as a geopolitical threat. China is accelerating its own constellation (GW) partially as a response. China's concerned about SpaceX's direct-to-cell capability being used to circumvent Chinese censorship. This approval probably accelerates Chinese counter-measures.

India: Interested in developing indigenous constellation capability. India views satellite internet as strategic infrastructure. They're exploring partnerships with other nations and private companies to reduce dependence on SpaceX.

Russia: Sanctioned from most space activities. Russia views Starlink (used in Ukraine) as hostile technology. Russia is exploring counter-space weapons development and jamming capabilities. SpaceX's approval indirectly accelerates arms race dynamics.

Developing nations: Generally support the approval because it enables connectivity in regions with poor terrestrial infrastructure. African, Asian, and Latin American countries see Starlink as opportunity, not threat.

The approval essentially solidifies American dominance over orbital infrastructure. Other countries are responding by:

- Accelerating indigenous constellation development

- Forming international partnerships to reduce dependence

- Developing counter-space technologies

- Negotiating new orbital spectrum and orbital slot allocations

This is creating an international space race dynamic reminiscent of Cold War era space competition.

FAQ

What does the FCC approval of 7,500 additional Starlink satellites mean?

The FCC approved SpaceX's authorization to launch 7,500 more Gen 2 Starlink satellites, bringing the total constellation to 15,000 satellites by the end of 2031. This approval also waived previous regulatory restrictions on overlapping coverage and capacity enhancements, allowing SpaceX to build out its mega-constellation faster than previously permitted. The decision essentially tells SpaceX that expanding to 15,000 satellites is strategically important and meets regulatory standards for environmental, technical, and national security concerns.

How does the FCC's 15,000-satellite limit differ from SpaceX's original request?

SpaceX originally requested authorization for 30,000 satellites. The FCC approved only 15,000, effectively cutting the requested constellation in half. This decision reflects regulatory caution about orbital density, space debris, and long-term sustainability concerns. The 15,000-satellite approval represents a compromise: enough satellites to achieve the company's core technical goals (global coverage, direct-to-cell, gigabit speeds) while addressing government concerns about orbital crowding and collision risks. SpaceX can request additional approvals after 2031, but 15,000 is the current ceiling.

What are the launch and deployment deadlines for the new Starlink satellites?

SpaceX must launch and operationalize 50% of the 7,500 new satellites by December 1st, 2028—roughly 3,750 satellites in about 3.5 years. The remaining 50% must be operational by December 31st, 2031. These deadlines are not optional suggestions; they're regulatory requirements that SpaceX must meet to maintain approval. Missing deadlines could trigger regulatory consequences, including launch restrictions or forced deorbiting of approved satellites. SpaceX's current launch cadence suggests these timelines are achievable but aggressive.

How will the 15,000-satellite constellation improve internet speeds compared to current Starlink?

Density enables speed. With 15,000 satellites instead of 6,000, SpaceX can offer gigabit-scale speeds (up to 1 Gbps) in optimal conditions, particularly in areas with lower user density. The increased constellation means more satellites overhead simultaneously, reducing latency and improving handoff speed between satellites. More satellites also means more total network capacity, allowing faster speeds per user. Current Starlink speeds (100-200 Mbps) are limited by smaller constellation density and Gen 1 satellite capacity. Gen 2 satellites with 8x capacity plus 2.5x constellation size creates significant performance improvements, though speeds will still vary by location and conditions.

What is direct-to-cell connectivity and why was it crucial to the FCC approval?

Direct-to-cell connectivity allows Starlink satellites to receive signals directly from standard mobile phones without requiring special ground equipment. Your regular iPhone or Android phone can text or send emergency data through Starlink satellites when outside terrestrial cell coverage. This capability was central to the FCC's approval decision because it provides emergency communication globally. The FCC prioritized this feature because emergency connectivity (especially SOS functions for people in remote areas) was deemed more important than the space debris and light pollution concerns raised by astronomers. This approval essentially mandates that telecom companies integrate satellite backup into consumer phones.

What collision and space debris risks come with 15,000 satellites?

More satellites exponentially increase collision probability in Low Earth Orbit. Each object moving at 17,500 mph creates potential debris if struck. The FCC acknowledged these risks but required SpaceX to maintain: active deorbiting procedures (satellites fall back to Earth after 5-10 years, not staying in orbit forever), continuous collision avoidance maneuvering (executed hundreds of times monthly), and precise orbital spacing protocols. Despite these mitigations, collision probability is higher with 15,000 satellites than with 6,000. SpaceX's own data shows it already performs dozens of evasive maneuvers monthly to avoid debris and conjunctions. With more satellites, this frequency increases.

How does the approval affect Amazon's Project Kuiper and other competing satellite internet providers?

The approval cements SpaceX's competitive dominance. Amazon's Project Kuiper constellation of 3,236 satellites will be dwarfed by Starlink's 15,000, giving SpaceX enormous network effect advantages in capacity, latency, and coverage density. Amazon will still deploy Kuiper successfully and profitably, but as a second-place player. The approval suggests Amazon cannot compete on constellation size and will need to differentiate on price, customer service, or specialized use cases. Other competitors (OneWeb, Telesat) have even smaller planned constellations. China's GW constellation of ~13,000 satellites is the only competitor approaching Starlink's scale, but it's years behind in deployment.

Will the satellite constellation cause noticeable light pollution for stargazers?

Yes. Starlink satellites are bright enough to affect astronomical observations during twilight and early night hours. Professional astronomers have complained extensively about disruptions to long-exposure observations. SpaceX deployed VisorSat (a sunshade) on some satellites to reduce brightness, but not all Gen 2 satellites will have this feature. The trade-off is explicit in the FCC approval: connectivity benefits outweigh astronomical observation impacts. Casual stargazers might see satellite streaks across the sky during twilight. This is an aesthetic loss but not a safety or functional issue for most people.

What happens after 2031 when the 15,000-satellite deadline arrives?

SpaceX will have completed the FCC-approved constellation. But this isn't the end of expansion. Satellites age and require replacement. SpaceX will likely request approval for additional satellites starting around 2030 to replace aging Gen 2 satellites with newer Gen 3 models. Gen 3 satellites are rumored to have 10x the capacity of Gen 2. The FCC will probably approve these requests given the precedent established. Orbital density will continue increasing. By 2035 or 2040, humanity might be discussing 25,000+ satellite mega-constellations from multiple operators. The 15,000-satellite approval is a chapter in a much longer story of orbital infrastructure expansion.

How much will this constellation cost SpaceX to build and launch?

Detailed costs are proprietary, but rough estimates suggest: satellite manufacturing at roughly

Could this approval be challenged or reversed?

Unlikely. The FCC approval has strong legal standing. It went through multi-agency review and received bipartisan political support. Reversing it would require new FCC commissioners with different priorities or Congressional action. Environmental or astronomer groups have limited legal grounds to challenge the decision. International concerns (China, EU) cannot directly challenge an FCC decision but can develop competing constellations. SpaceX's approval is secure barring extraordinary circumstances.

Conclusion: The Orbital Future Starts Now

The FCC's approval of 7,500 additional Starlink satellites is a pivotal moment. Not because of the technology, though the technology matters. But because it represents a fundamental decision: global connectivity justifies orbital density increases that previous generations would have deemed reckless.

This approval crystallizes a shift that's been underway for years. Space is no longer pristine frontier territory. It's infrastructure. Like highways and power grids, satellites become utility systems. And like utility systems, they're built at massive scale, with environmental costs accepted as necessary trade-offs.

The FCC essentially said: "Astronomers, we hear you. Space debris researchers, we understand the risks. But 7 billion people without reliable internet matters more. Approval granted."

SpaceX won. The company gets to build the constellation it always planned. By 2031, Starlink will be the dominant force in orbital communications. Every satellite internet competitor will operate in its shadow.

But here's the consequential part: this approval creates momentum. Other companies see that mega-constellations are approvable. Other countries see that America is using corporate space dominance to solidify geopolitical advantage. And astronomers see that their concerns, while acknowledged, don't actually prevent decisions they oppose.

Over the next decade, expect a flurry of mega-constellation approvals. Not just from SpaceX, but from Amazon, China, potentially others. Orbital density will increase. Collision risks will rise despite mitigation efforts. Light pollution will worsen. The night sky changes permanently.

But also expect direct-to-cell connectivity to reach billions of people. Expect remote work to become practically possible anywhere on Earth. Expect emergency responders to have reliable communications globally. Expect the digital divide to narrow significantly.

This is what governance trade-offs look like. Losses for some (astronomers, space purists, orbital debris researchers) offset by gains for others (rural residents, remote workers, emergency responders). The FCC made a choice about which benefits matter more.

You might disagree with that choice. Many astronomers do. But the choice is made. SpaceX has its approval. The launch timeline begins. By 2028, you'll see the effects in orbit. By 2031, the constellation reaches its full authorized size.

The orbital future isn't hypothetical anymore. It's approved. It's happening.

Use Case: Generating detailed reports on space policy, satellite infrastructure, and FCC regulatory decisions faster than writing them manually.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- FCC approved 7,500 additional Starlink Gen2 satellites, raising total constellation to 15,000 by 2031

- SpaceX must deploy 50% of new satellites by December 2028 and 100% by December 2031 under strict regulatory deadlines

- Direct-to-cell connectivity (satellite-to-phone communication) was the decisive factor enabling FCC approval despite space debris and light pollution concerns

- 15,000-satellite constellation will be 4.6x larger than Amazon's competing Project Kuiper, cementing SpaceX's orbital dominance

- Increased orbital density creates higher collision risks offset by active deorbiting procedures, collision avoidance maneuvering, and international coordination

- Gen2 satellites deliver 8x the capacity of Gen1 models, enabling gigabit-scale speeds and global coverage in 2031 timeframe

- Approval creates precedent for future mega-constellations and accelerates international satellite infrastructure race with China and EU competitors

![SpaceX's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What the FCC Approval Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-s-7-500-new-starlink-satellites-what-the-fcc-approval/image-1-1768081114518.jpg)