Stalkerware Apps Hacked: 27 Data Breaches & Why You Should Never Use Them [2025]

Introduction: The Stalkerware Industry's Security Nightmare

Imagine buying a product designed to secretly monitor your partner's phone, thinking you're getting peace of mind. What you're actually getting is a front-row seat to one of the internet's most prolific data breach disasters. Since 2017, at least 27 stalkerware companies have been hacked, leaked customer data, or suffered significant security compromises. That's not a typo. That's not an exaggeration. That's the documented reality of an industry that handles some of the most sensitive personal data imaginable yet treats security like an afterthought.

Stalkerware, also called spouseware or mobile monitoring software, is marketed to jealous partners and suspicious spouses who want to secretly track their loved ones. These apps promise to unlock intimate details: text messages, location data, call logs, photos, browser history, and more. They're advertised as relationship insurance, a way to catch cheaters or keep tabs on family members. But here's what the marketing doesn't tell you: these companies are catastrophically bad at protecting the very data they're collecting.

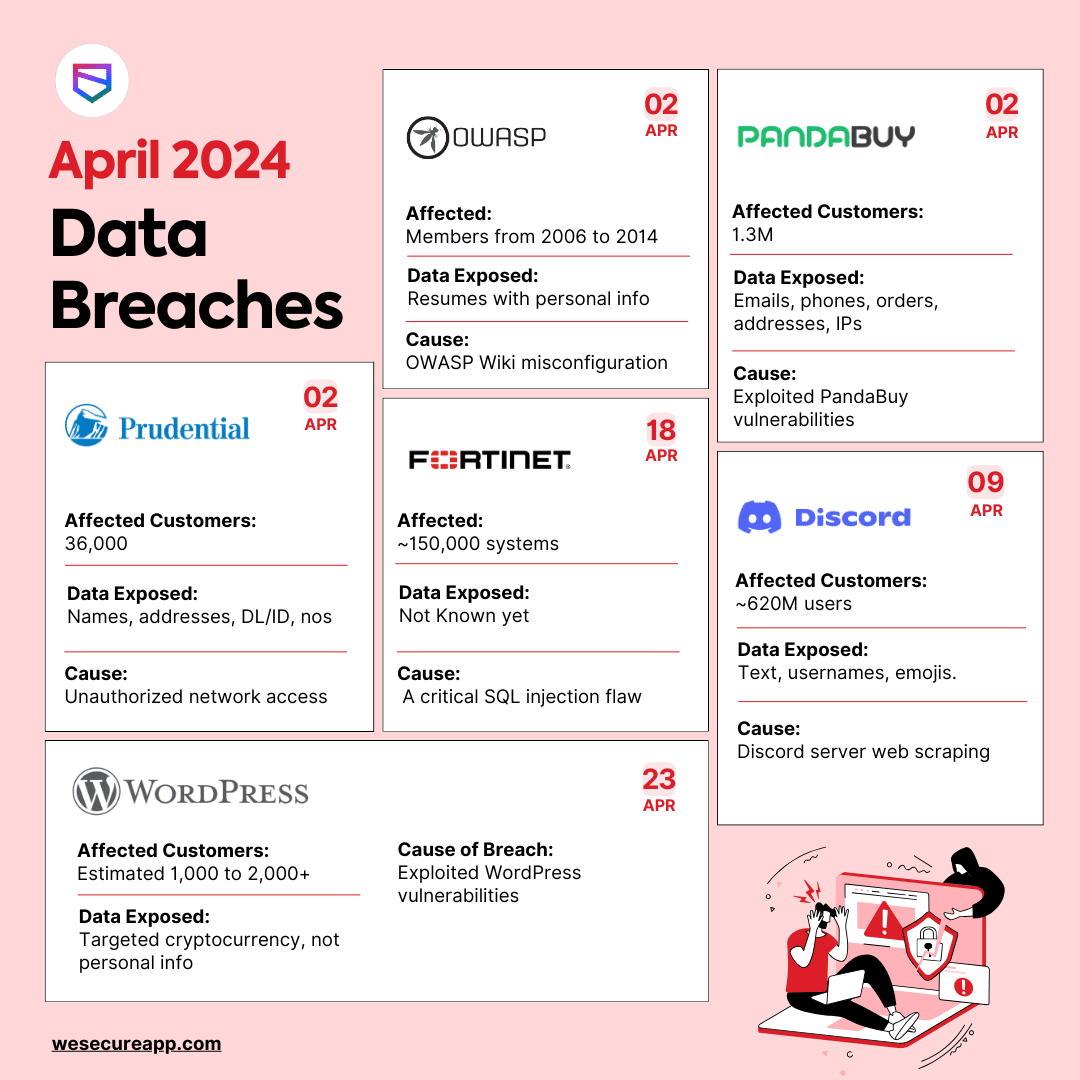

The u Mobix breach in early 2025 exposed payment information for over 500,000 customers. Before that, Catwatchful compromised at least 26,000 victims' phone data. In 2024 alone, there were massive breaches affecting m Spy, Spytech, pc Tattletale, and others. Messages intended to be private. Photos meant to stay hidden. Location data that could enable real physical harm. All exposed online, searchable, downloadable, weaponizable.

What makes this worse isn't just the sheer volume of breaches. It's that the victims—the people being monitored without consent—often have no idea their data was stolen. A customer buys the app to spy on their partner. The app company gets hacked. Now the victim's intimate digital life is in a stranger's hands. They were never asked for consent, never given a choice, never told their data was at risk.

This article breaks down the full landscape of stalkerware security failures, the real-world consequences of this industry's negligence, and why these apps should be treated as a threat to both your privacy and your safety. Whether you're considering using one of these apps, concerned someone might be using one against you, or just trying to understand why hacktivists keep targeting these companies, you need to understand what's actually happening in this industry.

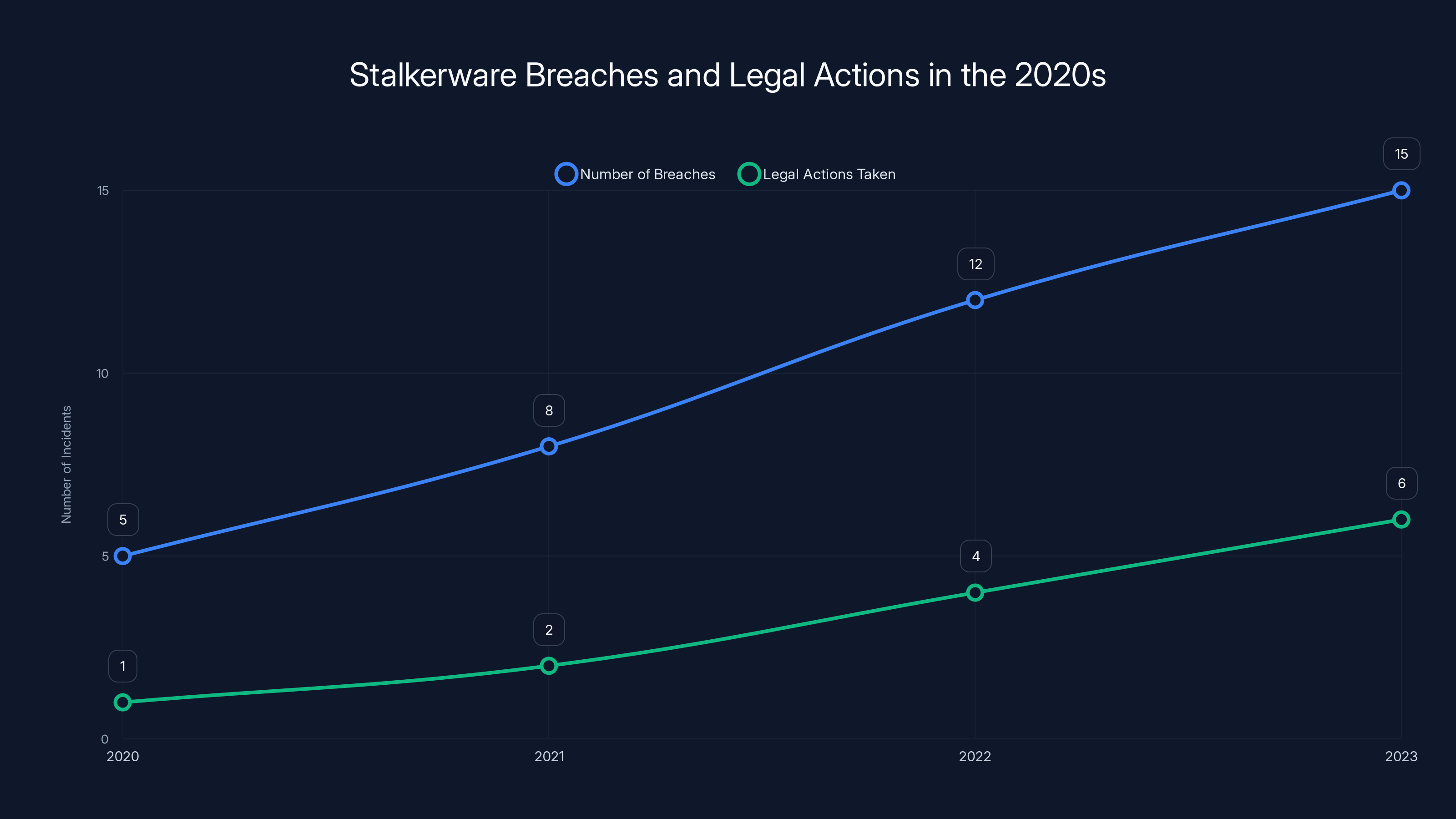

Estimated data shows an increase in both stalkerware breaches and legal actions in the 2020s, indicating growing scrutiny and enforcement.

TL; DR

- 27 stalkerware companies breached since 2017: Including recent 500,000+ customer data exposure from u Mobix and 26,000 victim records from Catwatchful

- At least 4 companies hacked multiple times: Stalkerware makers show a pattern of chronic security failures, not isolated incidents

- Victims harmed twice: People being monitored without consent have their data exposed without even knowing the app existed

- Criminal consequences rising: Founders and operators now face federal charges for illegal surveillance and computer hacking

- Better alternatives exist: If you're concerned about family safety or partner fidelity, there are legitimate, legal tools with actual security standards

What Exactly Is Stalkerware and How Is It Used?

Stalkerware isn't theoretical. It's commercially available software you can buy right now, often for less than a streaming subscription. Apps like u Mobix, m Spy, Cocospy, Spy X, and Spyzie are sold through normal e-commerce channels with credit cards, active customer support, and marketing campaigns. They work by installing on a target's phone and transmitting everything that happens on that device to a remote dashboard accessible only by the person who purchased the app.

The functionality is invasive by design. Once installed, stalkerware continuously monitors text messages, captures GPS location updates, logs phone calls, screenshots instant messaging apps, records browser history, and even activates microphones to record ambient audio. Some versions access email, photos, and app notifications. The monitoring happens in the background, invisible to the person being surveilled. They don't receive notifications. They don't get alerts. Their phone might be slightly slower. That's all they'd notice.

Marketing is explicit about the intended use case. Companies openly advertise their products as solutions for catching cheating partners. Taglines like "Catch a cheater" and "Know what they're really doing" appear prominently on their websites and in promotional materials. Some apps use gendered language targeting suspicious partners: features marketed to "make sure your spouse isn't messaging their ex" or "know where your wife really goes at night." The companies aren't shy about what they're selling. They're selling suspicion. They're selling surveillance. They're selling the ability to monitor without consent.

This creates a legal and ethical minefield. In most jurisdictions, installing monitoring software on a device without the owner's permission is illegal, regardless of your relationship to that person. You can't spy on your spouse. You can't track your teenage kid's phone with an invisible app. You can't monitor your friend's text messages. Yet these companies market their products to do exactly those things, often with explicit taglines encouraging illegal use.

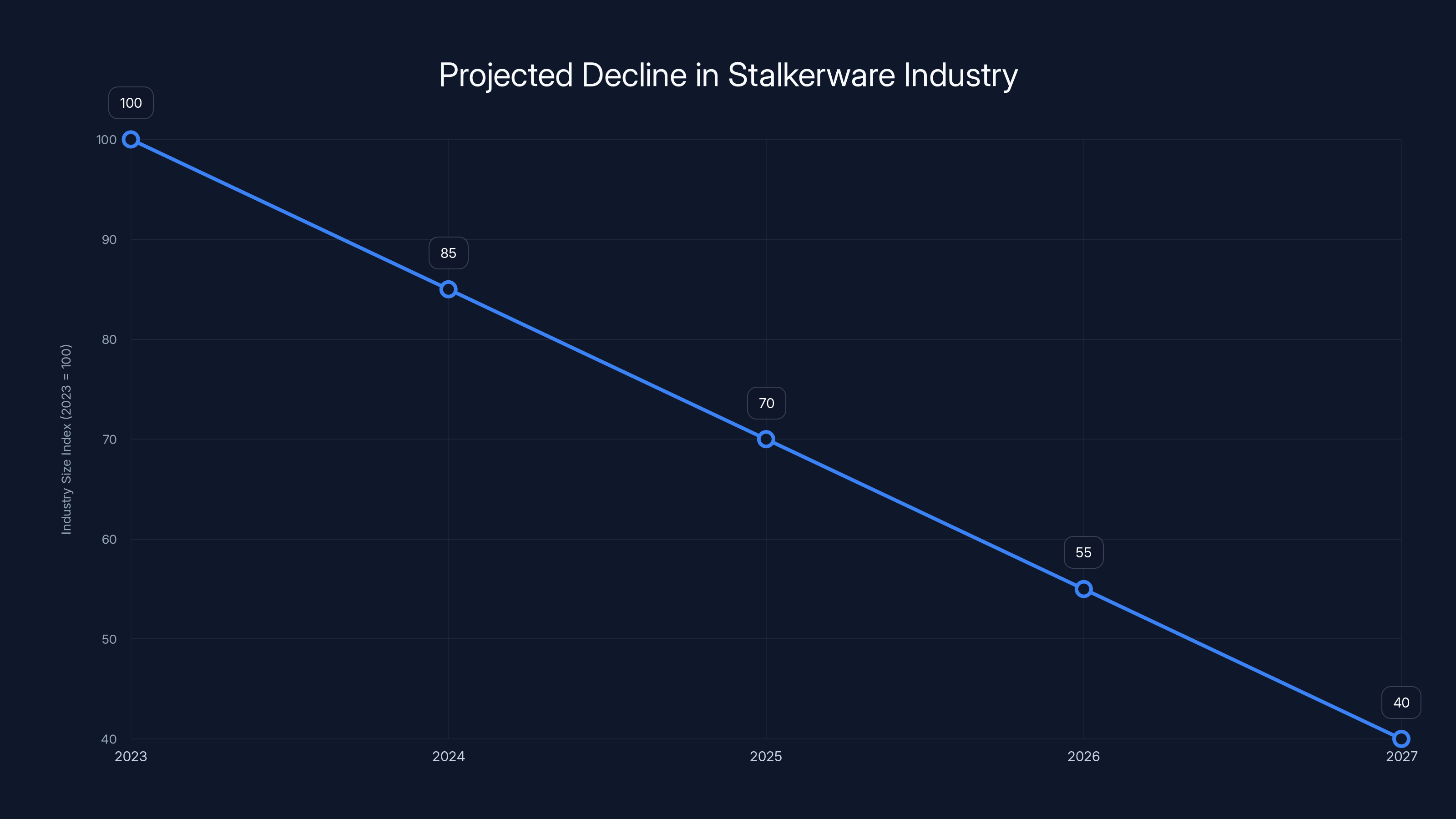

The stalkerware industry is projected to decline due to hacktivist pressure, legal consequences, and increased public awareness. Estimated data shows a significant reduction over the next five years.

The 2017 Retina-X and Flexi Spy Breaches: Where It All Started

The stalkerware breach timeline begins in 2017, though it's important to note these companies had been operating for years prior. Hackers breached two major stalkerware providers almost simultaneously: the US-based Retina-X and the Thailand-based Flexi Spy. The breaches were coordinated, deliberate, and motivated by a specific philosophy: these companies were morally indefensible and needed to be destroyed.

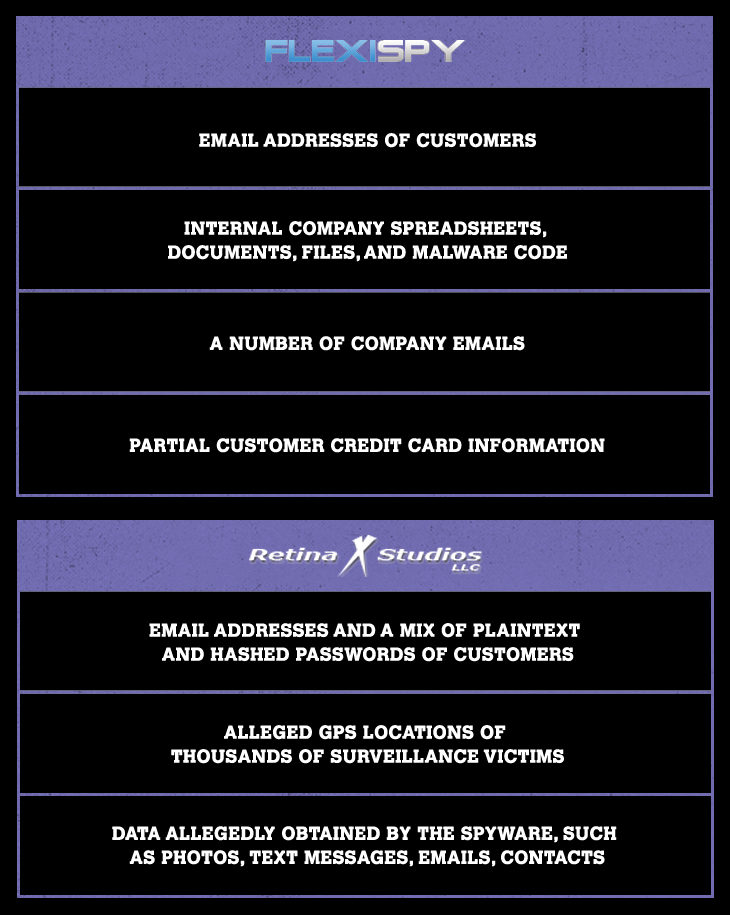

The Retina-X hack exposed approximately 65,000 customer accounts and revealed internal business records, financial data, and the personal information of surveillance victims. The company's servers were wiped, not just accessed. The attacker deliberately destroyed data with the goal of crippling the business. Days later, Flexi Spy was breached as well, exposing approximately 65,000 additional customer records and potentially hundreds of thousands of victim data points.

One of the hackers involved in the Retina-X operation spoke to journalists about motivation with remarkable clarity. "I'm going to burn them to the ground, and leave absolutely nowhere for any of them to hide," the hacker stated. The goal wasn't just to expose hypocrisy or prove a point. It was to shut down the business model entirely. The hacker acknowledged Flexi Spy's resilience: "I hope they'll fall apart and fail as a company. However, I fear they might try and give birth to themselves again in a new form. But if they do, I'll be there."

This wasn't wrong. Flexi Spy, despite the 2017 breach and years of negative media attention, remains operational today. The company pivoted, modified its marketing, and continued business. Retina-X initially survived as well, then got hacked again a year later. After the second breach, Retina-X finally shut down operations. It was a Pyrrhic victory for hacktivists. One company down, dozens more in operation.

What these early breaches established was a pattern: stalkerware companies were both profitable enough to target and insecure enough to penetrate. They were soft targets. The hackers had demonstrated it. And others were paying attention.

Mobistealth, Spy Master Pro, and the Cascade of 2017-2018 Hacks

Following the Retina-X and Flexi Spy breaches, the attack surface became clearer. Hackers realized these companies shared common vulnerabilities: weak security architecture, unencrypted databases, poor access controls, and no real security auditing. Within weeks of the Flexi Spy breach, attackers hit Mobistealth and Spy Master Pro in rapid succession.

The Mobistealth breach stolen gigabytes of customer records, business communications, intercepted victim messages, and precise GPS location data. This wasn't just customer information. This was the actual surveillance data collected from victims' phones. Intimate communications. Physical locations. Work addresses. Home coordinates. Information that could enable stalking in the physical world.

Spy Master Pro suffered a similar compromise. Again, gigabytes of data exposed. Again, customer records and victim information accessible to attackers. The attackers didn't seem particularly interested in financial gain. They were releasing data publicly, sometimes to media outlets, sometimes to security research organizations, sometimes anonymously online. The motivation was exposure and embarrassment of the companies involved.

Spy Human, an India-based stalkerware vendor, experienced its own breach during this same period. The pattern was becoming undeniable: these companies couldn't protect data. Whether it was incompetence, negligence, or just the structural reality of running a business built on illegal surveillance, the outcome was identical. Breaches. Exposures. Victims harmed twice over.

What's remarkable about this period is the speed. Within eighteen months, five major stalkerware companies were breached. If this were happening to legitimate software companies, it would trigger industry-wide security reviews, investment in infrastructure, talent acquisition of security experts. The stalkerware industry responded differently. Some companies hired better security. Most just kept operating as before, trusting that attack lightning wouldn't strike twice.

It did.

The 2020s Breaches: PCTattletale and the Legal Reckoning

The pace of stalkerware breaches didn't slow in the 2020s. If anything, they accelerated. PCTattletale, a US-based surveillance software company, experienced a significant breach where an attacker stole internal company data and deliberately defaced the company's website. The breach was symbolic. The attacker left messages on the public-facing site, essentially shaming the company and its owner, Bryan Fleming.

What made this breach notable wasn't just the data exposure, though that was severe. It was the consequences. Following the breach and public shaming, combined with media investigations into PCTattletale's actual use cases, Bryan Fleming made a decision: he would shut down the company. It seemed like a victory for privacy advocates and hacktivists. One less stalkerware company operating.

But that victory was temporary and limited. Fleming shut down PCTattletale, but the damage extended beyond that single company. Investigations revealed PCTattletale had been used to monitor check-in computers at US hotel chains, turning it into a tool for hotel staff to surveil guests. The ethical violations kept accumulating.

Soon after, Fleming faced legal consequences. He pleaded guilty to multiple federal charges: computer hacking, the sale and advertising of surveillance software for unlawful uses, and conspiracy. This marked a shift in how law enforcement was treating stalkerware. It wasn't just a civil matter anymore. It was criminal. Founders were facing federal prison time.

The legal precedent mattered. For years, stalkerware companies operated in a gray zone. Law enforcement wasn't prioritizing them. Prosecutors weren't filing charges. The business model seemed sustainable, even if morally questionable. Fleming's case changed the calculation. If you run a stalkerware company, you could face federal charges. That risk changed the risk-reward analysis, at least theoretically.

However, the industry didn't shrink. New companies emerged. Existing companies rebranded or relocated to jurisdictions with less enforcement. The legal pressure helped, but it didn't eliminate the market.

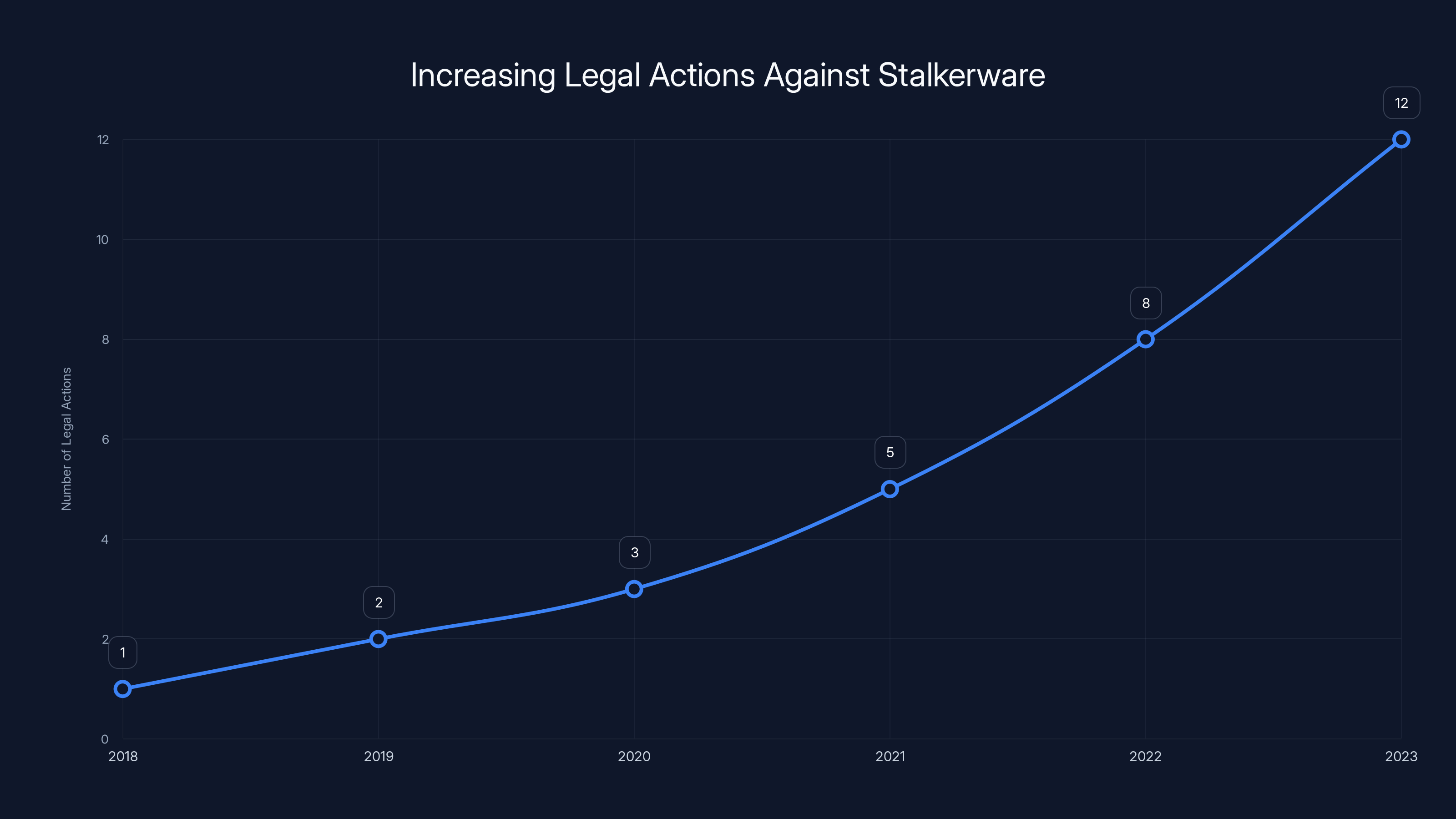

The trend shows a significant increase in legal actions against stalkerware companies from 2018 to 2023. Estimated data based on narrative insights.

m Spy and the Massive Customer Support Data Leak

m Spy holds the distinction of being one of the longest-running stalkerware applications. The company has been operating for years, accumulated a massive customer base, and maintained substantial infrastructure. It's also been breached at least twice, once severely enough to expose millions of customer support interactions.

When m Spy was breached, the attacker didn't just get customer email addresses and passwords. They got full customer support ticket histories. These weren't abstract data points. They were actual conversations between m Spy customers and support staff, often containing sensitive context about why the customer purchased surveillance tools.

Support tickets from people buying stalkerware often contain confessions and justifications. Someone might ask a support question about recovering deleted messages, and in the process, they're admitting they're trying to surveil their partner. Another customer might ask how to hide the app from the device owner. A third might describe relationship concerns that prompted the purchase. Customer support data from a surveillance software company is a treasure trove of incriminating information for customers and reveals the actual abuse use cases the company facilitates.

When m Spy's support tickets were breached and exposed, customers suddenly faced a different problem. Their surveillance activity was no longer secret. If anyone searched for their name, email address, or phone number in the exposed data, they could potentially find evidence of their illegal surveillance attempts. For customers who were conducting illegal monitoring, this was devastating. For the victims being monitored, it was validation of their worst suspicions.

m Spy's response to the breach followed a familiar pattern. The company acknowledged the breach, advised customers to change passwords, offered credit monitoring, and moved on. Security improvements, if any were made, weren't publicly disclosed. The business model continued. Customers were still signing up. The company was still collecting payment information and installing monitoring software on devices.

Spytech and the 2024 Activity Log Exposure

Spytech, a relatively lesser-known spyware maker based in Minnesota, became the latest example of a stalkerware company's catastrophic security failure. The 2024 breach exposed activity logs from phones, tablets, and computers that had been monitored using Spytech's software. Activity logs sound bland. They're not. An activity log from monitored surveillance contains detailed behavioral data: when someone woke up (based on device usage), when they went to bed, where they traveled (GPS logs), who they communicated with (message patterns), what websites they visited, what apps they used.

This is behavioral metadata. It's more revealing than individual messages or photos. It creates a complete picture of someone's life and habits. Exposed activity logs allow an attacker to understand daily patterns, identify sensitive locations (home, workplace, medical offices), and establish detailed behavioral profiles.

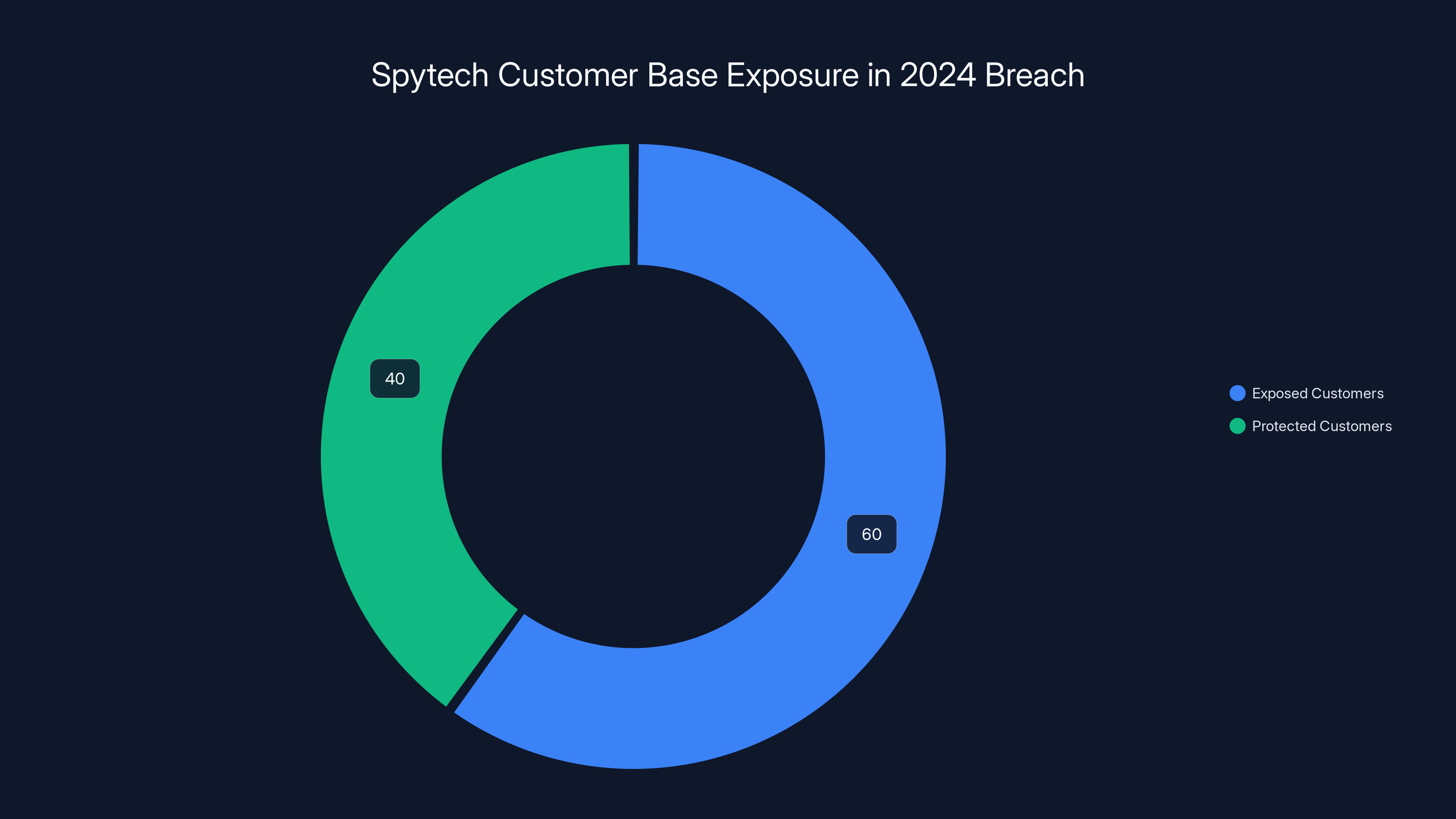

Spytech's breach was particularly problematic because the company's entire customer base was small enough that the breach potentially exposed a significant percentage of their operations. Unlike m Spy or u Mobix, which serve hundreds of thousands of customers, Spytech operated on a smaller scale. A breach that exposes 60% of operations is far more damaging to a company's reputation and customer trust.

The Minnesota-based operation didn't have the same geographic escape route as companies operating in jurisdictions with minimal cybercrime enforcement. Minnesota is in the United States, subject to federal law enforcement, and Spytech's breach made them vulnerable to legal liability in addition to the security failure itself.

Catwatchful's 26,000 Victim Data Exposure

Catwatchful's breach in 2025 represents something particularly disturbing: the exposure of 26,000 victim records. This number is critical. These weren't customers. Customers are the people who purchased the surveillance software. Victims are the people being surveilled.

A customer breach exposes the surveillance purchaser's data. That's bad for the customer but not necessarily bad for the victim. A victim breach exposes the data of people who had no choice, no consent, no awareness that they were being monitored. Their phones were compromised. Their data was collected. And then that collected data was further compromised.

For the 26,000 people affected by Catwatchful's breach, the cascade of violations was complete. Someone with a grudge or concerning relationship dynamics installed an app on their phone. That app secretly collected messages, location, contacts, and more. Then, a second attacker breached the Catwatchful servers and downloaded all that collected data. The original victim now has two people with access to their most intimate digital information.

Catwatchful's breach became a case study in why stalkerware is dangerous not just in concept but in practice. The company was making explicit promises to customers: "Your partner won't know their data is being monitored." What Catwatchful wasn't promising: "We'll actually protect their data once we're collecting it." They failed on both counts. Victims knew someone was monitoring them (or discovered it after the breach). The data wasn't protected at Catwatchful's servers either.

In 2017, both Retina-X and FlexiSpy breaches exposed approximately 65,000 customer accounts each, highlighting significant vulnerabilities in stalkerware companies.

The 2025 Data Exposure Cascade: Spy X, Cocospy, Spyic, and Spyzie

The first quarter of 2025 witnessed an unprecedented cascade of stalkerware data exposures. Multiple companies suffered breaches or data exposures that revealed sensitive victim information on public platforms, searchable and accessible to anyone.

Spy X, Cocospy, Spyic, and Spyzie all experienced significant data exposure incidents. A security researcher discovered a configuration bug in shared infrastructure that allowed unauthorized access to massive amounts of surveillance data. The bug didn't require sophisticated hacking. It was a configuration error. Essentially, monitoring data was accessible to anyone who knew where to look.

What made this incident particularly significant was the volume and sensitivity of data exposed. The researcher who discovered the bug found messages, photos, call logs, and other personal information from millions of victims. This wasn't anonymized metadata. This was the actual content of private communications. Photos that people thought were private. Messages sent in confidence. Call logs revealing relationships and communications patterns.

The exposed data painted intimate pictures of people's lives. Messages between couples discussing infidelity, reconciliation, or breakups. Conversations between parents and children. Medical information discussed in text messages. Work communications revealing employment situations. The security researcher who found the bug faced an ethical decision: report it to the companies, or release it publicly to expose the scope of the problem.

The choice to report the bug privately rather than publicly dump data was the more responsible approach, but it highlights the tension between different actors in this ecosystem. Hacktivists want to expose the companies. Researchers want to fix the technical problems. Users want their data protected. Companies want to continue business.

The 2025 cascade demonstrated that stalkerware isn't just vulnerable to targeted attackers. It's vulnerable to basic security oversights. Configuration bugs. Unpatched systems. Default credentials. These companies aren't being breached by sophisticated nation-state actors conducting advanced persistent threats. They're being breached because they don't implement basic security hygiene.

The u Mobix Breach: 500,000+ Customers and Beyond

The u Mobix breach represents perhaps the largest single stalkerware data exposure documented to date. A hacktivist scraped payment information for more than 500,000 customers and published the data online. This wasn't a subtle breach. This wasn't data that required sophisticated analysis to understand. This was customer names, email addresses, payment methods, and subscription details, all publicly accessible.

What made u Mobix's breach a political act was the stated motivation. The hacktivist explicitly claimed they targeted u Mobix to expose and damage the stalkerware industry. They were following a tradition established by previous hacktivists who breached Retina-X and Flexi Spy nearly a decade earlier. The motivation was ideological, not financial. There was no ransom demand. The data was released to accomplish exposure and embarrassment.

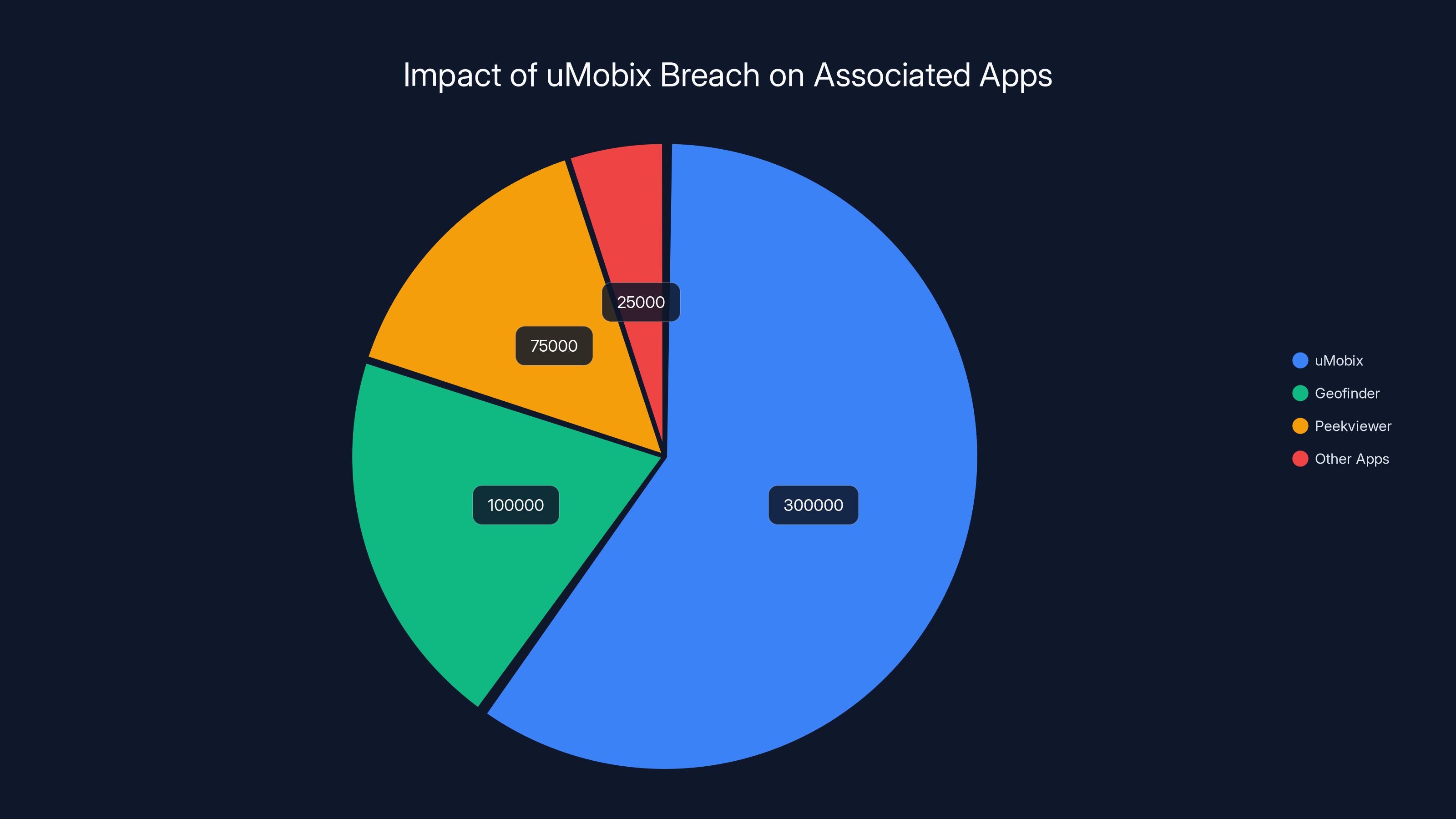

u Mobix is also notable because the company operates not just u Mobix itself but associated applications like Geofinder and Peekviewer. These apps have different branding and marketing, but they share backend infrastructure, customer databases, and operational oversight. A single breach compromised multiple apps simultaneously, affecting the user bases of multiple branded products.

The u Mobix breach also created a situation where payment card information was exposed. For the 500,000 affected customers, the breach meant more than just privacy violation. It meant potential financial liability. Exposed payment information can lead to unauthorized charges, fraudulent transactions, and identity theft. Customers who purchased stalkerware for the purpose of surveilling others suddenly had to worry about their own financial security.

The irony wasn't lost on observers. People who bought software designed to violate others' privacy and security suddenly experienced privacy and security violations themselves. It's tempting to see justice in that symmetry, but the reality is more complicated. Some affected customers were engaged in illegal surveillance. Others might have been using the software for legitimate purposes (monitoring minor children, though this is debatable). Regardless, exposure of payment information is a serious harm.

Why Are Stalkerware Companies So Insecure?

The pattern is clear at this point: stalkerware companies are consistently breached. At least four companies have been hacked multiple times. Why is the security so bad? The answer involves business model, motivation, talent, and business priorities.

First, the business model discourages hiring top security talent. Legitimate companies can recruit talented security engineers by offering meaningful work, ethical clarity, and professional respect. Stalkerware companies can't. If you're a skilled security professional, working for a company that helps people commit domestic abuse isn't a career path you'd choose. The ethical objection to the business model means the best talent avoids these companies entirely.

Second, the companies are under less regulatory pressure than mainstream software vendors. A company like Microsoft faces enormous regulatory scrutiny, security audits, compliance requirements, and potential liability for security failures. Stalkerware companies operate in a legal gray zone where they're primarily targeted by hacktivists rather than regulators. This removes one key incentive to improve security: legal liability.

Third, the companies often operate profitably despite security failures. If a breach happens, the company gets some negative press, then continues business as usual. Customers might leave temporarily, but new customers arrive to replace them. There's no market punishment for security failures because there's no legitimate market. The market for stalkerware is built on desperation, jealousy, and relationship dysfunction. Those drivers don't disappear just because of a security breach.

Fourth, stalkerware companies are often focused entirely on development and marketing with minimal infrastructure investment. They're trying to maximize profit margins, not build sustainable, secure business operations. Security requires investment. Infrastructure requires investment. These aren't priorities in the lean, margin-focused stalkerware business model.

Finally, the very nature of what these companies collect creates security challenges. They're collecting intimate data from thousands or millions of monitored devices. That data has to be stored somewhere. The collection volume requires substantial infrastructure. More infrastructure means more attack surface. The data collected is so sensitive that it's an attractive target for attackers with diverse motivations: hacktivists, competitors, foreign governments, or criminals interested in blackmail.

The 2024 breach exposed an estimated 60% of Spytech's customer base, significantly impacting their operations and reputation. Estimated data.

The Double Victimization Problem

One of the most disturbing aspects of stalkerware breaches is the double victimization of people being monitored. Let's trace the journey: Someone installs stalkerware on a partner's, child's, or friend's phone without consent. The app secretly collects messages, location, photos, and personal data. Then, the stalkerware company gets hacked. Now a third party has access to all that collected data.

The person being monitored might not even know they were being surveilled in the first place. They might discover it through a breach notification, or they might never discover it at all. But their data has been compromised twice: once when it was collected without consent, again when it was stolen from the company that collected it.

This creates a profound ethical problem. Victims of surveillance have no responsibility for the security of the platforms their data was stolen from. They didn't choose to give their data to Catwatchful or u Mobix. It was taken from them. The stalkerware customer chose to steal their data. The stalkerware company then failed to protect what it had stolen. The victim is harmed by both actions but responsible for neither.

In a legitimate customer-data relationship, the customer has some recourse if data is breached. They can sue. They can demand compensation. They can opt out in the future. Victims of surveillance have no such options. They were never customers. They were never offered terms of service they agreed to. Their data was extracted from them against their will, and they have no contractual standing to seek redress.

This is the structural injustice of stalkerware breaches. The victims are harmed the most and have the least recourse. They might face identity theft, emotional harm, psychological trauma, or even physical danger if exposed data is used by additional bad actors. But they had no choice in any of this. They didn't buy the app. They didn't fail to protect the data. They were simply targeted.

Hacktivism vs. Security: The Moral Complexity

Much of the documented stalkerware breaches have come from hacktivists with explicit anti-stalkerware motivations. People like Eva Galperin, the director of cybersecurity at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, have spent years investigating and fighting the stalkerware industry. Hacktivists see these companies as legitimate targets for exposure and destruction.

But here's the moral complexity that often gets overlooked: when hacktivists breach stalkerware companies, they sometimes expose victim data publicly. A hacktivist might breach Catwatchful with the intention of exposing the company's unethical practices. In the process, they make public the surveillance data that was collected from victims. The victims weren't the target of the hacktivist attack, but they're collateral damage.

Some hacktivists are careful about this. They report breaches to journalists, researchers, or relevant authorities rather than dumping data publicly. Other hacktivists take a more aggressive approach, publishing everything to maximize embarrassment and exposure of the company.

There's a legitimate debate about the ethics here. On one hand, hacktivists are exposing predatory companies and making it impossible for them to continue operating in stealth. On the other hand, their methods sometimes create secondary privacy violations for the people who were already most violated by the system.

Eva Galperin herself has described the stalkerware industry as a "soft target." What she means is that these companies are vulnerable to attack not just technically but morally. Nobody's running a sophisticated defense of the stalkerware industry. Nobody's arguing that these companies provide essential services. The attackers face minimal moral or legal pushback because the target is universally recognized as problematic.

The hactivist approach works because it puts pressure on the industry in ways that regulatory or legal approaches don't. Law enforcement can take years to build cases. Hacktivists can put a company out of business in weeks. The pressure from hacktivism might actually be more effective than formal legal systems at eliminating stalkerware.

The Real-World Consequences: Stalkerware Enabling Abuse and Violence

The breaches and security failures are significant, but they're symptoms of a larger problem. Stalkerware doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's used by people committing real crimes: illegal surveillance, harassment, emotional abuse, and in many cases, intimate partner violence.

Multiple court cases, media investigations, and surveys of domestic abuse shelters have documented how stalkerware is used as an instrument of control in abusive relationships. A controlling partner uses stalkerware to monitor where their victim goes, who they talk to, and what they do. The app becomes a tool of oppression and fear.

The surveillance doesn't occur in isolation. It's usually combined with other forms of control: financial abuse, emotional manipulation, threats, and sometimes physical violence. Studies of domestic abuse survivors reveal that the presence of monitoring technology is a significant risk factor for escalation to physical violence. A partner who's monitoring your every move is more likely to become violent when they discover you're doing something they disapprove of.

Stalkerware also enables stalking outside of intimate relationships. Parents use these apps to monitor adult children. Employers have been documented using stalkerware to track employees. One case involved a US hotel chain where staff used stalkerware to monitor guest check-in computers. The potential for abuse extends far beyond the jealous-partner narrative that stalkerware companies use in marketing.

When stalkerware is breached and victim data is exposed, the potential for harm escalates. An abuser who loses access to stalkerware might escalate to physical violence if they discover their victim using the breach as evidence of the monitoring. An exposed victim's data might be used by a second abuser to threaten or manipulate them. The security failures of stalkerware companies have direct, documented consequences for human safety.

Estimated data shows the majority of affected users were from uMobix, with significant impacts on Geofinder and Peekviewer as well. Estimated data.

How to Recognize If Someone Is Using Stalkerware Against You

Recognizing that you're being monitored isn't always obvious, but there are indicators. Your phone might be slower than usual. Battery drain might be excessive, indicating background processes running constantly. You might discover apps you don't remember installing. Some stalkerware apps hide themselves so thoroughly that they're nearly invisible, but others are detectable with careful examination.

More obvious signs might come from behavioral clues. Does someone always know where you've been? Do they have details about conversations you thought were private? Do they bring up information you didn't directly tell them? These could indicate monitoring through stalkerware.

One important thing to understand: it's not paranoia if you have evidence. If you suspect monitoring, don't dismiss the possibility. Domestic abuse frequently involves surveillance technology, and victims often minimize or dismiss their own concerns about being monitored.

If you suspect stalkerware, options include: taking your phone to an Apple Genius Bar or Android specialist for examination, performing a factory reset (which will remove most monitoring apps), changing passwords on important accounts from a different device, and seeking help from domestic abuse organizations or law enforcement.

The Cyber Civil Rights Initiative and National Domestic Violence Hotline have resources specifically for people dealing with technology-enabled abuse. These organizations understand the issue and can provide guidance tailored to your specific situation.

The Legal Reckoning and Rising Criminal Consequences

For years, stalkerware operated in a legal gray zone. Law enforcement didn't prioritize these companies. Prosecutors didn't bring charges. The business model seemed sustainable because there was minimal legal risk.

That's changing. As documented stalkerware breaches have accumulated and media attention has increased, law enforcement and prosecutors are taking more aggressive action against stalkerware companies and their founders.

Bryan Fleming of pc Tattletale pleaded guilty to federal charges including computer hacking, the sale and advertising of surveillance software for unlawful uses, and conspiracy. These aren't misdemeanor charges. These are serious felonies with potential prison time. The guilty plea signals that prosecutors take these cases seriously and that defendants are facing real consequences.

Other investigations are ongoing. The FTC has targeted spyware companies. State attorneys general have launched investigations. International law enforcement agencies in countries like South Africa have pursued stalkerware makers operating from their jurisdictions.

The legal pressure is having an effect. Some companies are shutting down. Some founders are facing criminal liability. The landscape is shifting from a business model with minimal consequences to a business model with substantial legal risk.

However, enforcement remains uneven. Some countries have minimal cybercrime enforcement. Some jurisdictions prioritize other crimes. Stalkerware companies operating from these jurisdictions face less legal pressure. The international nature of the internet means a company shut down in one country might restart in another.

Still, the trend is clear: the legal consequences are increasing. Running a stalkerware company is becoming riskier from a criminal liability perspective. That's reducing the number of people willing to be public faces of these companies, and it's raising the operational costs of companies trying to evade enforcement.

What Legitimate Alternatives Exist?

If you're concerned about family safety or a partner's fidelity, there are legitimate tools that don't involve illegal surveillance or predatory business models. Understanding the difference between legitimate and problematic approaches is important.

For monitoring children: Legitimate parental control software like Apple's Screen Time, Google Family Link, and similar built-in OS features allow transparent, consent-based monitoring. These tools are explicit about their purpose. The child knows they're being monitored. There's no hidden app. The monitoring is disclosed to the child and is appropriate for parental oversight of minors.

For location sharing: Apps like Life 360 or Google's Location Sharing feature allow people to voluntarily share their location with family members. Everyone involved knows about the sharing. It's not hidden. This is fundamentally different from stalkerware because consent is explicit and transparent.

For relationship concerns: If you're worried about a partner's fidelity or trustworthiness, the solution isn't surveillance. It's communication. Couples therapy. If the relationship has deteriorated to the point where you want to secretly monitor your partner, the relationship might have deeper problems that surveillance won't solve.

For employee monitoring: Companies that need to monitor employee activity should use transparent monitoring tools that employees are aware of. GPS tracking of company vehicles is different from tracking employees' personal phones without consent. Company laptops can have monitoring software if employees are informed and consent is documented.

The common thread: legitimate tools are transparent, explicit about their purpose, and based on some form of consent. Stalkerware is secretive, deceptive, and installed without knowledge or consent.

The Cybersecurity Lessons: Why These Companies Fail

From a cybersecurity perspective, stalkerware companies demonstrate almost every security anti-pattern imaginable. Their failures offer lessons for security professionals about what not to do.

First, they collect vast amounts of sensitive data with minimal security architecture. The data collection is the entire business model, but the data protection is an afterthought. This is backwards. If your business depends on protecting sensitive data, security should be your first investment, not your last.

Second, they operate with minimal regulatory oversight. For legitimate companies, regulatory requirements drive security investment. Healthcare companies must comply with HIPAA. Financial companies must meet PCI DSS standards. Stalkerware companies face minimal such requirements, and many operate specifically to evade existing regulations. This removes a key driver of security.

Third, they hire engineers without security expertise. A company building surveillance infrastructure needs security engineers at its core. Stalkerware companies often treat security as optional. The result is predictable: systems that are breached repeatedly.

Fourth, they fail to implement basic security practices. Encryption at rest and in transit. Access controls. Secure authentication. Password policies. Audit logging. These are basic practices that any company should implement, yet stalkerware companies consistently fail at them.

Fifth, they treat breaches as public relations problems to be minimized rather than security problems to be addressed. A legitimate company breaches user data, conducts a thorough investigation, redesigns systems, implements new controls, and prevents recurrence. Stalkerware companies breach, issue a brief statement, and move on without substantive changes.

These anti-patterns exist in part because the stalkerware industry attracts people without strong security backgrounds. It also exists because the industry prioritizes profit margins over sustainability. It exists because there's less regulatory pressure than in legitimate industries. But ultimately, it exists because the stalkerware industry is fundamentally predatory, and predatory business models don't attract the talent or prioritize the practices needed for real security.

Broader Implications for Privacy and Surveillance

The stalkerware industry reveals something uncomfortable about surveillance in the internet age: it's easy to do, it's hard to defend against, and it's appealing to people with problematic motivations. The fact that commercial stalkerware exists demonstrates that the technical barriers to creating surveillance infrastructure have fallen dramatically.

In previous eras, sophisticated surveillance required government resources. Intelligence agencies, law enforcement agencies, with advanced technical capabilities and large budgets could conduct surveillance. Today, a person with a few hundred dollars can conduct sophisticated surveillance against another person.

This democratization of surveillance technology is simultaneously empowering and dangerous. It's empowering because individuals can protect themselves and their data more easily than before. It's dangerous because the same tools that enable protection also enable abuse.

The stalkerware industry also reveals that surveillance normalization is real. People are comfortable paying for surveillance tools. The marketing frames surveillance as reasonable: "Know what your spouse is really doing." The framing makes surveillance seem like a natural relationship tool rather than a privacy violation and potential crime.

This normalization of surveillance creates a backdrop where larger surveillance systems—government monitoring, corporate tracking, algorithmic profiling—seem more acceptable. If it's normal to monitor a spouse's phone, maybe it's normal for the government to monitor communications. If it's normal for a company to collect location data, maybe it's normal for advertisers to track our browsing.

The stalkerware industry demonstrates that without strong legal and cultural pushback against surveillance, the norm shifts toward acceptance. The role of hacktivists and researchers in exposing these companies is significant precisely because it maintains pressure against that normalization.

Moving Forward: Industry Pressure, Legal Changes, and User Awareness

The future of the stalkerware industry will be determined by three factors: continued hactivist pressure, increasing legal consequences, and growing public awareness.

Hacktivists have demonstrated that they can effectively shut down or damage stalkerware companies. The Retina-X shutdown, the pc Tattletale shutdown, and the damage to other companies from breaches and public exposure show that active opposition can have real consequences. As long as hacktivists maintain focus on the stalkerware industry, the business model will remain under threat.

Legal consequences are increasing. As more founders face criminal charges, as more prosecutions proceed, the personal risk calculation for running a stalkerware company changes. People willing to run sketchy businesses might not be willing to risk prison time. The legal environment is shifting from permissive to punitive.

Public awareness is growing. Articles like this one, investigative journalism from outlets like Tech Crunch, and increased media coverage are making clear that stalkerware is not a legitimate tool but a predatory industry. That awareness reduces the number of potential customers who would consider using these apps.

The combination of these three factors won't eliminate stalkerware overnight. But the trend is clearly toward reduction and marginalization of the industry. Companies that were operating openly a few years ago are now operating more cautiously. Some have shut down entirely. The market is shrinking.

What's critical is maintaining that pressure. The stalkerware industry is still active. Companies are still operating. People are still being monitored without consent. The work of exposing the industry, supporting victims, and maintaining legal pressure must continue.

Conclusion: Privacy Rights and the Path Forward

The documented history of stalkerware breaches tells a clear story: companies built on surveillance of intimate lives are incapable of protecting data when they finally face security challenges. Not a single documented stalkerware company has maintained perfect security. The breach rate approaches 100 percent. At least 27 companies have been compromised. At least four have been hit multiple times.

This isn't a coincidence or a series of isolated incidents. This is a structural failure of an industry built on morally indefensible practices. Companies that exist to facilitate abuse and surveillance shouldn't be trusted with data security. They aren't trustworthy. The track record proves it beyond dispute.

For people considering using stalkerware: understand that you're not just violating someone's privacy. You're putting their data in the hands of companies with a documented history of failing to protect it. If you want to monitor someone, you're also putting them at risk of secondary breach and exposure.

For people concerned they might be monitored: the risk is real. Stalkerware is commercially available, relatively easy to install, and increasingly prevalent. If you suspect monitoring, take it seriously. Seek help from domestic abuse organizations or law enforcement.

For researchers, activists, and policymakers: the work continues. Hacktivism has been effective at damaging the stalkerware industry, but it's not a long-term solution. Robust legal enforcement, strong privacy rights, and educational campaigns about surveillance are needed.

For technology platforms and device manufacturers: the stalkerware industry's existence reveals gaps in mobile security. Apple and Google need to continue hardening OS-level protections against hidden apps. They need to make it harder to install spyware and easier for users to detect compromise.

The future isn't determined yet. The stalkerware industry could continue evolving and adapting, finding new jurisdictions, new marketing angles, new technical approaches. Or it could be pushed toward extinction through sustained legal, technical, and social pressure.

What's clear is this: the data doesn't lie. Stalkerware companies get breached because they don't understand security, don't prioritize it, and don't deserve to be trusted with sensitive data. That's not going to change until the business model changes. And the business model isn't going to change until the pressure is maintained.

FAQ

What is stalkerware and how does it differ from legitimate monitoring software?

Stalkerware is commercially available surveillance software installed on someone's phone without their knowledge or consent to secretly monitor their messages, location, photos, and more. It differs from legitimate monitoring tools like Apple Screen Time or Google Family Link, which are transparent about their purpose, disclosed to the monitored person, and require explicit consent. Stalkerware is designed to be hidden and deceptive, which is why it's often illegal to use.

Can I be prosecuted for using stalkerware to monitor someone?

Yes, in most jurisdictions using stalkerware to monitor someone without their consent is illegal, regardless of your relationship to them. Federal and state laws prohibit unauthorized computer access and interception of communications. Using stalkerware on a spouse, partner, child, friend, or anyone else without explicit consent can result in criminal charges, civil liability, and restraining orders. Bryan Fleming, founder of pc Tattletale, pleaded guilty to federal charges related to selling surveillance software for unlawful uses.

What should I do if I think I'm being monitored with stalkerware?

If you suspect monitoring, first don't panic and seek help immediately. Contact a domestic abuse hotline, the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative, or law enforcement if you're in an unsafe situation. You can check for unfamiliar apps in your settings, review device permissions for suspicious access, or take your phone to an Apple or Android specialist for examination. A factory reset will remove most monitoring apps, but do this safely after backing up important data. Document any suspicious behavior and seek professional guidance tailored to your specific situation.

Why do stalkerware companies keep getting breached despite the security risks involved?

Stalkerware companies get breached repeatedly because they lack the technical expertise, resources, and motivation to implement proper security. The industry attracts people without strong cybersecurity backgrounds, prioritizes profit margins over security investment, and faces minimal regulatory pressure that would normally drive security improvements. Additionally, the sensitive nature of the data they collect makes them attractive targets for hacktivists and criminals. Basic security practices like encryption, access controls, and regular audits are often missing or poorly implemented.

Who is responsible for protecting victim data that's stolen from a stalkerware company?

This is a complex legal question. The stalkerware company bears primary responsibility for securing the data they collected, but victims—who never consented to that data collection in the first place—have limited legal recourse. Unlike customers, victims have no contractual relationship with the stalkerware company and often don't know they were being monitored. While hackers who expose the data can be prosecuted for unauthorized access, and the stalkerware company can be sued for negligent security, victims often face barriers to legal action. This legal gap is one reason why privacy advocates argue for stronger regulations.

What can I do if my information was exposed in a stalkerware company data breach?

If you suspect your data was involved in a stalkerware breach, immediately change passwords on critical accounts using a different device, monitor credit card and bank statements for unauthorized activity, place a fraud alert with credit bureaus, and consider freezing your credit. Check breach databases like Have I Been Pwned to see if your email appears in documented breaches. If you were being monitored without consent, document everything and consider contacting law enforcement or a lawyer. Organizations like the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative can provide additional guidance specific to your situation.

Why do hacktivists keep targeting stalkerware companies?

Hacktivists target stalkerware companies because they view them as predatory organizations that enable domestic abuse, harassment, and privacy violations. Hackers see these companies as legitimate targets for exposure because the industry operates in a legal gray zone, the business model is built on facilitating illegal surveillance, and traditional law enforcement hasn't historically prioritized enforcement. Hacktivists believe that making stalkerware companies' operations visible, damaging their reputation, and shutting down their infrastructure serves a greater good by preventing abuse. While the ethical implications of hacktivist data releases are complex, the pressure they apply has resulted in company shutdowns.

Are there legitimate reasons to use monitoring software on someone's device?

There are limited legitimate scenarios for device monitoring, all involving transparency and consent. Parents can use tools like Apple Screen Time or Google Family Link to monitor minor children—but these tools are designed to be visible to the child and disclosed as parental oversight. Employers can monitor company-issued devices if employees are explicitly informed. Individuals can voluntarily share location through apps like Life 360 where all parties consent. However, secretly monitoring a spouse, adult child, friend, or anyone else without knowledge and consent is illegal and unethical, regardless of the monitoring tool used.

What regulatory changes are being made to address stalkerware?

Regulatory attention to stalkerware is increasing. The FTC has targeted spyware companies and is developing guidance on surveillance software. Several states have proposed or passed legislation specifically addressing stalkerware. The European Union's Digital Services Act and other regulations are being interpreted to cover monitoring software. However, enforcement remains uneven globally, and stalkerware companies sometimes relocate to jurisdictions with minimal enforcement. International cooperation on cybercrime law enforcement is improving but remains a challenge.

Key Insights and Actionable Takeaways

The documented reality of 27+ stalkerware breaches since 2017 isn't just a technical failure story. It's a human story about surveillance, abuse, privacy rights, and the structural incentives that drive companies to prioritize profit over protection. Understanding this landscape is critical whether you're a parent concerned about monitoring, a person worried you're being surveilled, a security professional studying breach patterns, or someone interested in digital rights.

The most important takeaway is this: stalkerware is not a legitimate tool. It's not a relationship insurance policy. It's not a responsible way to monitor family members. It's a predatory industry built on facilitating illegal surveillance and abuse. The security failures are symptoms of that fundamental problem. Companies designed to help people commit crimes shouldn't be trusted to protect data. They won't be. And the evidence of 27+ breaches proves it definitively.

If you're considering using stalkerware, understand the legal and ethical implications. If you're concerned about being monitored, take the concern seriously and seek help. If you're working in cybersecurity or digital rights, the stalkerware industry offers clear lessons about what happens when security is deprioritized in pursuit of profit and when business models are fundamentally predatory.

The future of this industry depends on continued pressure from law enforcement, hacktivists, researchers, and public awareness. As that pressure increases, the stalkerware landscape continues to shift toward marginalization. The breaches will likely continue as companies shut down, expose their data, or face legal consequences. But with sustained focus on protecting privacy rights and supporting victims of surveillance, the trajectory is clear: the days of the stalkerware industry operating openly and without consequences are numbered.

Key Takeaways

- At least 27 stalkerware companies have been breached or leaked data since 2017, demonstrating systemic security failures across the entire industry

- The 2025 uMobix breach exposed 500,000+ customer payment records; Catwatchful exposed 26,000 victim records showing victims harmed twice without consent

- At least 4 stalkerware companies were hacked multiple times, revealing chronic security failures rather than isolated incidents

- Victims of surveillance suffer double victimization: data stolen without consent first by stalkerware, then compromised again in company breaches

- Stalkerware companies are intentionally designed as insecure soft targets with minimal security expertise, making them attractive to hacktivists working to shut them down

- Using stalkerware is illegal in most jurisdictions regardless of your relationship to the monitored person; founders now face federal criminal charges

- Legitimate monitoring alternatives like Apple Screen Time and Google Family Link exist and use transparent, disclosed approaches with actual security standards

Related Articles

- Best VPNs for Super Bowl LIX: Complete Streaming Guide 2025

- Proton VPN Windows Split Tunneling + Kill Switch: Complete Guide [2025]

- Flickr Data Breach 2025: What Was Stolen & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- Digital Squatting: How Hackers Target Brand Domains [2025]

- Discord Age Verification for Adult Content: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Iran's Digital Surveillance Machine: Complete Internet Control [2025]

![Stalkerware Apps Hacked: 27 Data Breaches & Why You Should Never Use Them [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/stalkerware-apps-hacked-27-data-breaches-why-you-should-neve/image-1-1770662323471.jpg)